This chapter looks at the landscape of vocational education and training (VET) providers in Denmark. It describes the Danish VET system and zooms in on the different types of institutions that provide VET programmes. The chapter looks at how providers differ in terms of focus areas of the provided training and target audience, as well as the role of private and public providers. Lastly, the chapter also discusses how different types of providers are co‑ordinated and how they collaborate.

The Landscape of Providers of Vocational Education and Training

3. Denmark’s landscape of vocational education and training providers

Abstract

The Danish vocational education and training system

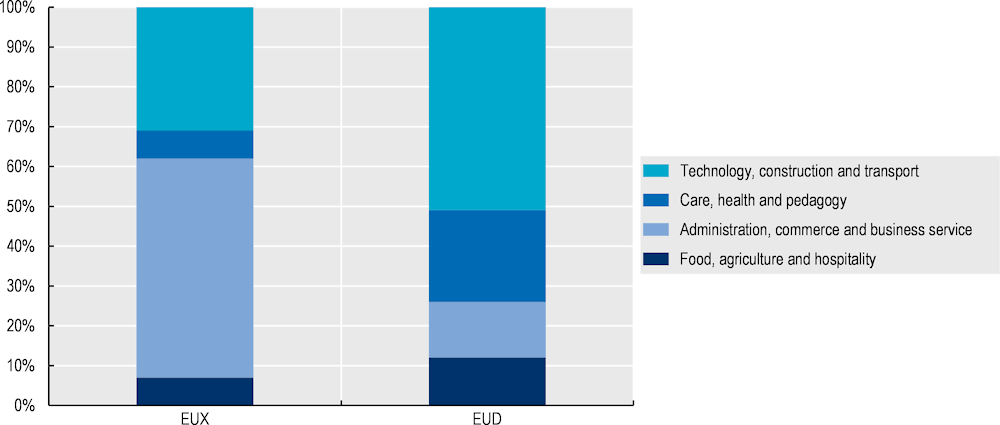

The VET system in Denmark is organised in upper-secondary and post-secondary levels. At the end of primary education, students choose between general (73.1%) or vocational upper secondary education (19.4%) (CEDEFOP, 2018[1]).Vocational education and training at the upper-secondary level includes four main subject areas: i) food, agriculture and hospitality; ii) technology, construction and transportation; iii) administration, commerce and business service; and iv) care, health and pedagogy (Ministry of Children and Education, 2021[2]). The typical duration of an upper-secondary VET programme is three to four years, compared to two to three years for general programmes. Most upper-secondary VET programmes have a large work-based learning component. Students usually spend between half and two‑thirds of their time in training companies under an apprenticeship contract. They can access apprenticeships after a basic training programme in vocational schools, usually lasting the first 12 months of their studies (Ministry of Children and Education, 2021[2]). Apart from the regular upper-secondary VET programmes (called EUD or erhvervsuddannelse), Danish upper-secondary education also provides EUX programmes (erhvervsfaglig studentereksamen, introduced in 2012), offering the opportunity to gain both vocational and academic credentials and providing direct access to higher VET and academic tertiary education. By 2018, 42 different technical VET fields (approximately half of all programmes) and all business programmes had implemented EUX (CEDEFOP, 2018[1]). About a third of students who enter vocational education do so in a EUX programme (Danske Erhvervsskoler og -Gymnasier, 2021[3]). The proportion of students who follow business programmes is almost four times higher in EUX than in EUD. By contrast, the field of 'care, health and pedagogy' it is more than three times lower in EUX than in EUD.

Figure 3.1. Students in vocational programmes in Denmark, by field and VET programme type

Note: EUD programmes are the regular upper-secondary VET programmes, EUX programmes are upper-secondary programmes that combine general and vocational education.

Source: Danske Erhvervsskoler og -Gymnasier (2021[3]), Elever på eux, https://deg.dk/tal-analyse/eux-0/elever-paa-eux.

All VET qualifications in the upper-secondary level prepare for direct entry into the labour market, but also allow for entry into higher-level vocationally-oriented programmes at ISCED levels 5 and 6. These higher‑level education programmes are: 1) academy professional programmes (ISCED 5), lasting 2 to 4 years, oriented towards specific professions or job functions; and 2) professional bachelor programmes (ISCED 6), which are three to four and a half years long, similar to university bachelor programmes, but with a stronger focus on professional practice. In many cases those students finalising an academy professional programme can opt to complete a professional bachelor programme within one to two years of study.

Denmark also has a large adult VET sector, providing vocational qualifications to adults that are comparable to those offered to young students. The adult VET sector in Denmark is organised in five types of programmes:

EUV programmes (Erhvervsuddannelse for voksne), offering basic vocational qualifications similar to EUD programmes.

Higher preparatory single subject programmes (HF-enkeltfag) aimed at individuals looking to improve their skills in one or two subjects at upper-secondary level, preparing them for tertiary studies.

AMU programmes (labour market education, Arbejdsmarkedsuddannelser), aimed at both high‑skilled and low-skilled workers looking to acquire either general skills or job-specific skills (leading to credentials at European Qualification Framework levels 2 to 5), usually related to one field of VET.

Academy programmes, higher-VET level specialisation programmes (ISCED 5) offered by business academies and university colleges for skilled professionals (primarily for people with EUD).

Diploma programmes, higher level specialisation programmes (ISCED 6) for skilled professionals with prior higher education offered by business academies, university colleges and some universities.

Access to the first three programmes is granted by VET institutions on the basis of recognition of prior learning (non-formal or informal) and/or completion of formal lower-secondary general education focused on adults (CEDEFOP, 2018[1]). Access to academy courses requires completion of an upper-secondary qualification and two years of work experience. Access to diploma programmes requires prior higher education (at least ISCED 5). Academy and diploma programmes are both 60 credits (based on the European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System, ECTS) and are provided as standalone modules of 5-15 ECTS, typically on a part-time basis. Diploma programmes give access to master level academic part-time programmes.

The provider landscape

In Denmark, upper-secondary VET programmes are delivered by vocational colleges (erhvervsskoler). These colleges are state funded (by a mix of a base funding allocation per institution, and additional funding per student), and operate as technical colleges (tekniske skoler), Health and Social colleges (SOSU skoler), or business colleges (handelsskoler). Vocational colleges are self-governing institutions, led by a governing board,1 with responsibility for the administrative and financial aspects, as well as of the educational activities, in line with the regulatory framework administered by the Ministry for Children and Education (UNESCO-UNEVOC, 2021[4]). Vocational colleges are non-for-profit and autonomous in terms of adapting VET to local needs and demands. They have responsibility for teaching and examination and work closely with local training committees in determining course content. As a country with a strong dual system, social partners play an important role in relation to the content of VET programmes and the organisation of VET delivery.

In higher education, there are mainly four types of providers, two of which are VET-related: business academies (erhvervsakademier) and university colleges (professionshøjskoler). In addition, research universities (universiteter) provide academic bachelor’s degrees, masters, some diploma programmes and PhD degrees and higher institutions of arts offer university level programmes within the arts.

The business academies in Denmark are non-for-profit independent organisations. The main aim of the academies is to offer and develop higher education with a strong relation to practice, especially in the area of technical and mercantile educations. These institutions mainly offer academy professional programmes and academy programmes, but also some professional bachelor programmes and diploma programmes. Academies have a management board, responsible for the quality and development of programmes at the institution. Board members are expected to have experience and knowledge of academy institutions. The board also includes members with knowledge about labour markets needs and with experience in management and business. Daily management of the institution is responsibility of the rector (president). The rector implements the directives defined by the academy board (Field et al., 2012[5]).

University Colleges mainly offer professional bachelor programmes and diploma programmes, but can also offer academic professional programmes as an initial step towards a professional bachelor’s degree and academy programmes. The University Colleges are independent institutions lead by a board, which has strategic responsibility for the quality and development of education and the institution. They are operated on a daily basis under responsibility of the rector, subject to the strategic direction of the board. The board has 10-15 members, which are typically representatives of local and regional government, students and teachers. University Colleges must develop applied research, also acting as centres of knowledge in close dialogue with regional stakeholders from industry and the civil society. University colleges attempt to achieve these goals in co‑operation with relevant research institutions and universities (Danish Agency for Higher Education and Educational Support, 2012[6]).

Adult VET programmes are offered by these three provider types, as well as by AMU centres. These are independent centres specialised in the provision of AMU courses.

Table 3.1. Overview of main VET providers in Denmark

|

Education level |

Public or private |

Key features |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Vocational colleges |

ISCED level 3 |

Public |

Technical colleges, health and social colleges, and business colleges provide upper-secondary education to young people and adults, as well as AMU courses |

|

Business academies |

Mostly ISCED level 5, but also some ISCED level 6 programmes |

Public and private |

Mostly provide short-cycle tertiary education programmes to young people and adults |

|

University colleges |

Mostly ISCED level 6, but also some ISCED level 5 programmes |

Public and private |

Mostly provide professional bachelor programmes to young people and adults |

|

AMU centres |

Various levels |

Public |

Centres specialised in adult education, offering short term courses (AMU courses) to upskill and reskill the adult population |

Note: More details about the various providers are provided in the following sections. ISCED 3: upper secondary education; ISCED 5: short‑cycle tertiary education; ISCED 6: bachelor’s level or equivalent.

Focus areas

Out of 103 vocational colleges, 89 are technical colleges, business colleges, agricultural colleges or combination colleges (with technical and business colleges representing the largest number of institutions) and 14 colleges offer social and health care training programmes.2 Technical colleges usually cover topics such as technology, construction and transport, whereas combination colleges usually offer a variety of subjects, including those related to the hospitality sector, and business and administration (Eurydice, 2021[7]).

In higher education, business academies usually have a business and administration focus, a technology focus or a shared focus in both areas. In some cases, academies also offer a wider variety of VET subjects, including fields such as arts, design and media, health and social care and hospitality. These institutions can collaborate with university colleges, engineering schools and universities.

Outside of the main providers, Denmark also has two types of specialised institutions: maritime educational institutions and institutions in architecture and art. The maritime educational institutions offer education programmes for the Danish merchant fleet, the maritime industry, the fishing industry, the energy sector and the technical industry, etc. – provided at different education levels. The institutions providing these maritime programmes are: five Marine Engineer Colleges; one Maritime Education Centre for Ship’s Officers; two Nautical Colleges; two Schools and two Sailing Training Vessels for Ordinary Ratings; and one School for Commercial Fishermen. There are four education institutions that offer higher educations within the Fine Arts.

Target audience

The adult VET sector is relatively large in Denmark, and adults can enrol in VET in dedicated institutions for adults and in the same institutions that enrol young students. A large part of formal education provision for adults is delivered in vocational colleges, i.e. the same institutions as upper-secondary vocational education for young students. Apart from special arrangement for adults, such as part-time programmes, recognition of prior learning and adjusted apprenticeships, the qualifications for young people and adults have a similar structure, leading to the same professional profiles. Higher-level formal adult education programmes can be offered only by the institution providing higher VET programmes to young students, i.e. business academies and university colleges.

This provision in vocational colleges and higher VET providers is complemented by AMU centres, i.e. independent centres specialised in adult education (regulated by the Act on Labour Market Centres), offering short term courses (AMU courses) to upskill and reskill the adult population. AMU centres do not offer basic upper-secondary VET qualifications for adults (EUV) or higher-level programmes (academy and diploma programmes). AMU centres were created with the distinctive mission of providing easily accessible short qualifications and training courses for adult workers (or adults seeking employment), especially those with lower qualifications looking to upskill or qualified workers looking for specialisation. Training activities are primarily directed towards specific sectors and job functions. AMU centres are vital, as they provide tailored training alternatives to those adults in need of specific knowledge and skills to better perform on the job, or looking to start a new professional path. AMU programmes are mainly short vocational training courses for adults offered at both upper-secondary level and tertiary levels, both in part‑time and full-time formats. These programmes can last between half a day and 6 weeks. (Ministry of Children and Education, 2020[8])3. AMU programmes target both skilled and unskilled adults over 20 years of age. Both employed and unemployed people can participate in AMU courses (Cort, 2002[9]). AMU courses are mainly provided by AMU centres, but also by vocational colleges all over the country. Some private companies and other educational institutions can also be certified as providers of specific AMU courses (Cort, 2002[9]). There are approximately 3 000 different AMU courses offered by different types of providers.

For the provision of AMU programmes, greater autonomy has been granted to vocational colleges and AMU centres with regards to the content structuring, organisation and financial management of their activity compared to other types of programmes. For example, when compared to upper secondary vocational education credentials, AMU programmes can be designed in a less structured way. They may or may not include work-based learning activities and involve a number of hours that varies significantly across programmes based on the amount of content covered and students’ specific needs. Moreover, across AMU programmes the assessment procedures and completion requirements also vary significantly, and do not depend on a pre-specified regulation. Some of these courses work as credits to acquire VET qualifications, whereas others do not lead to any formal qualification.

Private versus public providers

In Danish upper-secondary education there are no publicly funded private or fully private vocational upper secondary education institutions (Eurydice, 2022[10]). Since 1989 all colleges are independent public institutions with their own board of governors. By contrast, the majority of institutions at the higher-level, i.e. university colleges, and business academies, are private. All institutions are accredited and regulated by the Ministry of Education or the Ministry of Higher Education and Science respectively. Both private and public institutions must follow the regulation regarding the offer of programmes and credentials issued. Funding at both levels of VET is mostly public and follows predefined criteria. While they can generate income from alternative activities, all VET institutions remain not-for-profit.

Co‑ordinating between provider types

At the upper-secondary education level, vocational colleges function independently, receiving funding from the state. VET colleges are under the responsibility of the Ministry of Education. The Ministry is in charge of overseeing that the existing regulations are being followed. Vocational colleges often participate in joint initiatives, organised by the central government, private foundations or local governments, in topic such as innovation, employability or teacher training. For example, the Knowledge Centre for IT in Teaching promotes the use of advanced digital technology in VET. The Centre has established a network of pedagogical staff and a network of vocational school leaders across the country to facilitate the exchange of ideas and share their practical and technical knowledge, creating new solutions to common challenges. The Centre focuses on supporting teachers in the use of IT for teaching across all subjects with a special focus on the pedagogical aspects of teaching practice making use of innovative technology (CIU, 2022[11]).

At the tertiary level, business academies and university colleges are all state funded self-governing institutions, with the autonomy to grant VET credentials. All higher education institutions are under the supervision of the Ministry of Higher Education and Science, whereas the accreditation of all these institutions is performed by the Danish Accreditation Institution. The Ministry of Higher Education and Science is in charge of overseeing the quality of VET provision as well as the observance of the national regulations. Collaborations between university colleges, academic universities and business academies exist in certain areas (e.g. promotion of science education, scientific research), but are not necessarily widespread and systematic. The fact that part of their funding is based on the number of students, and that there is an overlap in terms of the types of credentials offered by different types of institutions, creates some incentives to compete to attract students, possibly undermining potential collaborations.

References

[1] CEDEFOP (2018), Vocational education and training in Europe: Denmark. VET in Europe Reports, http://libserver.cedefop.europa.eu/vetelib/2019/Vocational_Education_Training_Europe_Denmark_2018_Cedefop_ReferNet.pdf.

[11] CIU (2022), Center for IT i Undervisningen, https://videnscenterportalen.dk/ciu/aktuelt/.

[9] Cort, P. (2002), Vocational Education and Training in Denmark: Short Description., https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/files/5130_en.pdf.

[6] Danish Agency for Higher Education and Educational Support (2012), OECD-review. Skills beyond School. National Background Report for Denmark., https://ufm.dk/en/publications/2012/files-2012/oecd-review-skills-beyond-school-denmark.pdf.

[3] Danske Erhvervsskoler og -Gymnasier (2021), Elever på eux, https://deg.dk/tal-analyse/eux-0/elever-paa-eux.

[10] Eurydice (2022), Organisation of private education - Denmark, https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/organisation-private-education-22_en.

[7] Eurydice (2021), Denmark. Upper secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary Education, https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/upper-secondary-and-post-secondary-non-tertiary-education-8_en.

[5] Field, S. et al. (2012), A Skills beyond School Review of Denmark, OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264173668-en.

[2] Ministry of Children and Education (2021), Vocational education and training in Denmark, https://eng.uvm.dk/upper-secondary-education/vocational-education-and-training-in-denmark.

[8] Ministry of Children and Education (2020), Adult vocational training, https://eng.uvm.dk/adult-education-and-continuing-training/adult-vocational-training.

[4] UNESCO-UNEVOC (2021), TVET Country profiles. Denmark, https://unevoc.unesco.org/home/Dynamic+TVET+Country+Profiles/country=DNK.

Notes

← 1. The board consists of teachers, students and administrative staff representatives, and social partner representatives. The board takes decisions regarding offer of programmes, the administration of the college’s financial resources, and hires and fires the operational manager (director, principal, dean or similar) (UNESCO-UNEVOC, 2021[4]).

← 2. Extracted from https://uddannelsesstatistik.dk on 31.01.2022.

← 3. The main goals of AMU programmes are: i) to give, maintain and improve the vocational skills of the participants in accordance with the needs and background of students, companies and the labour market in line with technological and social developments; ii) to solve restructuring and adaptation problems on the labour market in a short term perspective; and iii) To give adults the possibility of upgrading of competences for the labour market as well as personal competences through possibilities to obtain formal competence in vocational education and training (Ministry of Children and Education, 2020[8]).