Marion Lagadic

Josephine Macharia

Magdalena Olczak

Marion Lagadic

Josephine Macharia

Magdalena Olczak

This chapter begins with an analysis of existing gender inequalities in the transport sector with regard to women both as transport users and in the transport workforce. Next, the chapter discusses policy frameworks that aim to close gender gaps in the transport sector. It also provides examples of policy initiatives that support policy makers in collecting gender disaggregated data and integrating a gender perspective into transport policies and transport planning.

Transport positively affects individuals by providing access to jobs, education, healthcare, and other public services. It also creates significant economic gains beyond individual benefits, contributing to societies’ economic growth and well-being.

Yet, transport remains one of the sectors with highest gender imbalance. Gender inequalities, as other structural inequalities which exist in societies, are reflected in transport systems. The barriers to women’s mobility that reinforce these inequalities include poor accessibility, gender-blind design of transport services and infrastructures, and a lack of safety and security of transport systems. The transport workforce is also highly gendered and women remain underrepresented in most transport-related industries.

More urgency is needed to integrate a gender perspective into transport planning and combat labour market inequalities, notably in the context of the recent global crises that could have significant and long-term implications for gender equality.

Improving gender equality both for women as transport users and in the transport workforce remains a challenge in many of the 64 International Transport Forum’s (ITF) member countries. Both areas are interconnected, as an increase in gender equality in the transport workforce will improve the inclusiveness of transport services.

Although transport policies involve infrastructure and service provision, they often do not consider the mobility needs of women. For example, Ng and Acker (2018[1])showed that women are more likely to have shorter commute distances, chain trips, have more non-work-related trips, travel at off-peak hours, and choose more flexible modes. Qualitative studies shed light on the lived mobility experiences of women, marked by the challenge to reconcile conflicting work and care responsibilities, all in a context of limited time and financial resources (Akyelken, 2020[2]; Plyushteva and Schwanen, 2018[3]). In short, women’s mobility needs appear to be different from those of men due to the inequalities women face in society.

Inadequate transport infrastructure has a more significant negative impact on women than on men vis-à-vis economic opportunities. Women are generally more sensitive to time constraints and put a higher opportunity cost on travel time. Safety also is a key determinant of women’s transport choices. In both developed and developing countries, women feel unsafe using public transport services: 80% of women have experienced harassment in public spaces, including public transport and associated public spaces (ITF, 2018[4]). Safety issues hamper women’s access to education, jobs, and other opportunities, and ultimately reinforce gender equalities.

There may also be gender bias in existing transport policies and services. Gender differences in travel behaviour are often overlooked, due to inadequate data and lack of representation of women among decision makers (de Madariaga, 2013[5]; Siemiatycki, Enright and Valverde, 2019[6]). Indeed, the transport workforce is male‑dominated and contains gender gaps throughout all staff levels. The historically low representation of women in the transport sector creates gender-biased attitudes and barriers, as well as discriminating work environments and conditions (Fraszczyk and Piip, 2019[7]).

Women remain underrepresented in most transport-related industries, with only 17% female employees in the transport workforce on average across 46 countries (Ng and Acker, 2020[8]). In addition, few of these women rise to managerial positions. In global supply chains and logistics, women occupy less than 20% of top executive positions across all sectors (Vaughan-Whitehead and Caro, 2017[9]). It is also more common for women to have less job security and lower-paid jobs than men across the transport sector (Barrientos, 2019[10]).

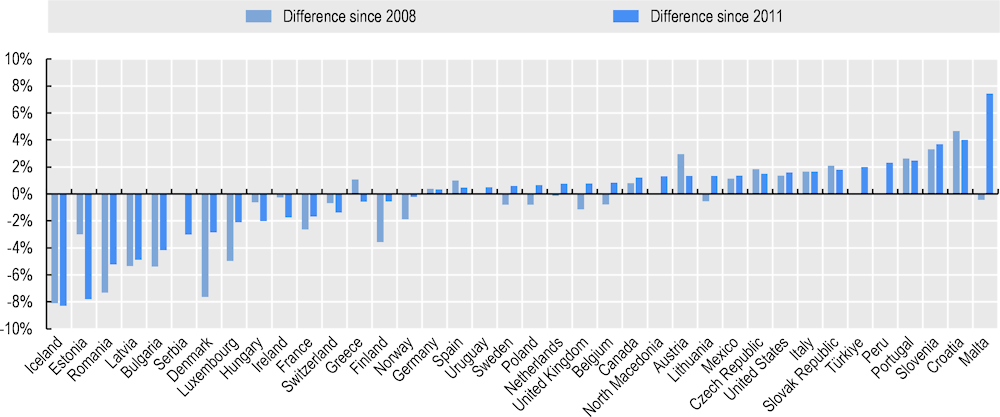

While female participation in the transport workforce is progressing in some countries, the global averages have remained relatively stable between 2008 and 2018. This is due to decreases in female participation in the sector among several of the countries with some of the smallest gender gaps (Figure 21.1).

Source: Ng and Acker (2020[8]), “The Gender Dimension of the Transport Workforce”, https://doi.org/10.1787/0610184a‑en.

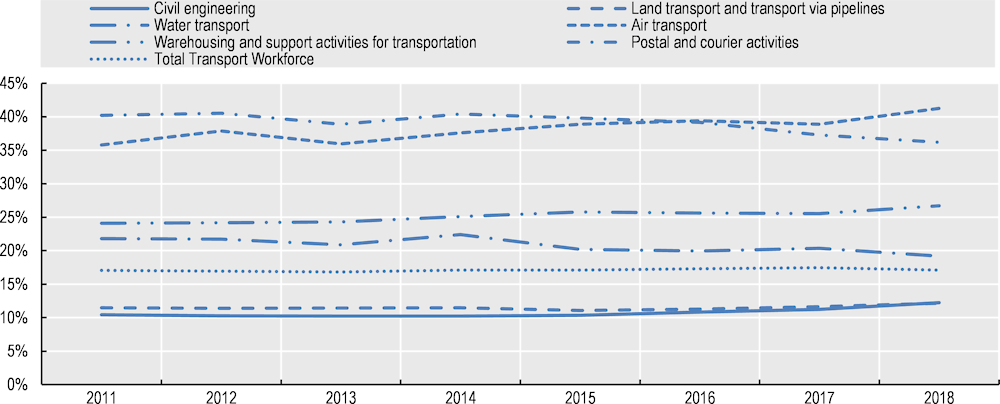

There were minimal changes in female participation in all divisions of the transport sector between 2011 and 2018 (Figure 21.2). The largest country-level declines were within the postal and courier activities division, more specifically in a subset of European countries. These experienced decreases in female labour force participation of up to 35 percentage points from 2008 to 2018. The air transport division shows the most notable growth in female labour participation, particularly in Europe, with country-level increases of up to 19 percentage points since 2008. However, the average female participation in the air transport sector for 43 countries across the world has only increased by 5 percentage points since 2011 (Ng and Acker, 2020[8]).

Note: The number of countries included in each division of the transport sector are as follows: civil engineering (44), land transport and transport via pipelines (50), water transport (35), air transport (43), warehousing and support activities for transportation (50), postal and courier activities (47), total transport workforce (50). Estimations were made based on existing data trends to fill data gaps for varying years and divisions for Armenia, Belgium, Brazil, Bulgaria, Cambodia, Croatia, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Ecuador, Egypt, El Salvador, Hungary, Iceland, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Mauritius, Mongolia, Montenegro, Namibia, Philippines, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Serbia, Slovenia, Thailand, Uruguay, and Viet Nam.

Source: Ng and Acker (2020[8]), “The Gender Dimension of the Transport Workforce”, https://doi.org/10.1787/0610184a‑en.

The COVID‑19 pandemic has further reinforced existing challenges for women in the transport workforce and could have significant and long-term implications for gender equality in transport. Women’s travel patterns aggravated gender inequality because of greater reliance on public transport than on private transport. Although the pandemic severely impacted all workers, specific adverse effects have been observed on women. This is primarily because women disproportionately face inadequate policy designs placing them at increased health and occupational risks in the transport sector. For example, the risks to men workers are better known given that occupational safety and health considerations had previously focused on jobs in sectors dominated by male workers (ITF, 2021[11]).

The ITF survey on “Integrating Gender Perspectives in Transport Policies” allowed to explore a series of gender-related policy and data issues in transport in 25 of the ITF’s 64 member countries (respondents include Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Canada, Chile, China, Colombia, Croatia, the Czech Republic, France, Ireland, Japan, Latvia, Lithuania, Mexico, Mongolia, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Portugal, Republic of Moldova, Romania, Spain, Sweden, Türkiye and the United Kingdom). Among others, the survey covers issues related to gender-sensitive policy frameworks and data in the transport sector (ITF, 2021[11]).

According to the survey, at least 40% of the responding countries have a national strategy or action plan or national legislation on gender equality that provides frameworks for promoting equal rights for men and women while strengthening economic and social empowerment for women and preventing violence against women and girls (VAWG).

Sectoral ministries or agencies implement these frameworks, including the authorities responsible for transport policies. Transport ministries in at least 30% of the ITF member countries contribute to implementing national gender strategies with measures and plans to promote gender equality in transport. Practices include gender-based analysis, impact and risk assessments, gender-responsive budgeting initiatives, collection of gender disaggregated data, and awareness-raising initiatives (Chapter 4). Transport ministries often co‑ordinate with other government departments and create special directorates to promote gender equality. Box 21.1 includes examples of such integration of gender perspectives into transport policies.

Gender equality is also a part of the sustainable transport development plans in at least 25% of ITF member countries.

Women’s participation in the transport workforce remains the most common challenge, especially within modes such as aviation and maritime, or road transport, where ensuring women have high-level positions can be complex. Countries’ initiatives to integrate gender aspects into transport policy include access and accessibility in transport, climate change, sustainable mobility, and combating gender-based violence. Countries also take initiatives to promote women’s participation in transport-related education and training, enhance women’s leadership, and support the use of a gender-sensitive and inclusive language.

The COVID‑19 pandemic offered an opportunity to improve gender equality by rethinking transport design and policies to address the needs of women transport users and workers. Gender-specific transport measures include free access for pregnant women who need maternal health services during COVID‑19 or digital access (i.e. mobile phone‑based health services, smart travel applications) to avoid walking long distances or having to use other transport modes to reach healthcare facilities. Travel restrictions on some streets have allowed safer travel for cyclists and pedestrians. An increase in bike lanes and free repair stations, and measures to respace cities will increase transport safety for all. In the short term, these changes can address the disruption in public transport. In the long run, they could help women by allowing more efficient trip chaining (ITF, 2021[12]).

The Government of Canada has been committed to using Gender-Based Analysis (GBA) Plus in the development of policies, programmes and legislation since 1995. At Transport Canada, the GBA Plus Centre of Excellence works to integrate the application of GBA Plus through guidance and review of GBA Plus conducted in support of Cabinet documents, funding submissions and budget proposals.

In Chile, the Ministry of Transport and Telecommunications contributes to the implementation of the National Plan for Equality between Men and Women 2018‑30. Mainstreaming gender is essential for the implementation of effective policies that promote equity with regard to mobility, accessibility, security and efficiency of the systems of transportation.

In Mexico, the Ministry of Communications and Transport contributes to the implementation of the National Programme for Equality between Women and Men 2020‑24. This includes awareness-raising initiatives to incorporate a gender perspective in the planning of urban and rural road infrastructure to provide women with better access to basic services. The ministry also works towards incorporating gender aspects in the design and improvement of infrastructure to ensure the safe transit of women and girls in public spaces.

In Sweden, the Ministry of Infrastructure is responsible for mainstreaming a gender perspective in all decisions and actions in accordance with a government decision for gender mainstreaming within the Government Offices for the period 2021‑25. The political goals for the transport sector include that transport policy should reflect respective mobility needs of women and men.

In the United Kingdom, despite the lack of a strictly defined national gender strategy, there is, however, a cross-government focus on gender equality through a Minister for Women and Equalities, which is supported by the government Equalities Office (GEO). As part of its priorities, GEO supports cross-government strategies, such as increasing female participation in the labour market and preventing violence against women and girls. This office works closely with a number of Government departments including the UK Department for Transport.

Source: ITF (2021[11]), Integrating Gender Perspectives in Transport Policies Survey.

At least 30% of ITF member countries collect transport gender-disaggregated data, while another 15% collect gender indicators specific to transport. Examples of transport and gender data and indicators collected are mostly related to labour, public transport, education and training, safety, and modal share.

Gender indicators are most pressingly needed as they relate to perception of safety, modal choice, and trips motives. Gender indicators concerning the participation of women in transport-related education and the transport workforce help to better understand the gender balance of the transport workforce. Several countries are interested in a better understanding of the interface between women’s economic empowerment and access to transport, be it through the participation of women in the transport workforce or their access to education and job opportunities overall.

National statistics offices are the most important actor for the collection of gender-disaggregated data, followed by ministries responsible for transport. Most countries consider that transport ministries and statistical offices should take the lead if transport gender-disaggregated data collection needs to be improved (ITF, 2021[11]).

Robust gender-disaggregated data and indicators that integrate a gender perspective in the collection, analysis and presentation of statistical data on transport issues provide a starting point to assess and measure gender equality or gaps. Challenges in the collection of reliable gender-disaggregated data related to transport prevent a full integration of gender aspects into transport policy making.

For instance, existing data gaps on travel behaviour make it challenging to develop evidence‑based sustainable and inclusive transport policies that will address the needs of all users, including women, children, the elderly, and persons with disabilities (Sustainable Mobility for All,, 2019[13]). Such challenges also do now allow to get a thorough understanding of the gendered impact of transport policies.

The measurement of changes in needs between women and men over time is an essential part of gender-sensitive monitoring and evaluation of the impact of various policies. Ultimately, gender data and indicators can help raise awareness by increasing the visibility of existing gender gaps in transport through reliable and accurate data.

Part of these challenges relate to insufficient guidance, capacity and resources within the bodies in charge of transport policies. Guidelines for gender mainstreaming in transport are limited. Insufficient operational guidelines and tools exist to support policy makers in collecting gender-disaggregated and gender-sensitive data in the transport sector. Lack of human resources and budget restrictions are often obstacles to collecting gender-disaggregated data.

In order to address existing data gaps and to provide guidelines for gender-disaggregated and sensitive data collection, the ITF developed a “Gender Analysis Toolkit for Transport Policies” (ITF, 2022[14]). The Toolkit includes a list of gender and transport indicators that can help governments and other stakeholders identify their priorities and design surveys that will facilitate data collection processes and assess current gender equality levels. The Toolkit also provides a checklist that will help policy makers and project managers assess the gender dimensions of their policy and project, even if gender-disaggregated or gender-sensitive data are not yet available.

Public policy should aim to close gender gaps in transport by integrating a gender perspective into transport policies and planning, and addressing labour market inequalities in the transport sector.

Gender analysis, supported by reliable gender-disaggregated data, is the first step towards achieving gender equality. Policy guidelines should be developed to support policy makers in collecting gender-disaggregated data and integrating gender aspects into transport policies.

Implementing a collaborative multi-stakeholder approach can address gender inequalities in working conditions and tackle existing gender norms and stereotypes in the transport sector.

[2] Akyelken, N. (2020), “Living with urban floods in Metro Manila: a gender approach to mobilities, work and climatic events”, Gender, Place and Culture, Vol. 27/11, pp. 1580-1601, https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369x.2020.1726880.

[10] Barrientos, S. (2019), Gender and Work in Global Value Chains, Cambridge University Press, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108679459.

[5] de Madariaga, I. (2013), From Women in Transport to Gender in Transport: Challenging Conceptual Frameworks for Improved Policy Making, Journal of international affairs, New York.

[7] Fraszczyk, A. and J. Piip (2019), “A review of transport organisations for female professionals and their impacts on the transport sector workforce”, Research in Transportation Business & Management, Vol. 31, p. 100379, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rtbm.2019.100379.

[14] ITF (2022), ITF Gender Analysis Toolkit for Transport, https://www.itf-oecd.org/itf-gender-analysis-toolkit-transport-policies-0.

[12] ITF (2021), Gender Equality, the Pandemic and a Transport Rethink, https://www.itf-oecd.org/sites/default/files/gender-equality-covid-19.pdf.

[11] ITF (2021), “Integrating Gender Perspectives in Transport Policies Survey”, Unpublished survey findings.

[4] ITF (2018), Women’s Safety and Security: A Public Transport Priority, https://www.itf-oecd.org/sites/default/files/docs/womens-safety-security_0.pdf.

[8] Ng, W. and A. Acker (2020), “The Gender Dimension of the Transport Workforce”, International Transport Forum Discussion Papers, No. 2020/11, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/0610184a-en.

[1] Ng, W. and A. Acker (2018), “Understanding Urban Travel Behaviour by Gender for Efficient and Equitable Transport Policies”, International Transport Forum Discussion Papers, No. 2018/01, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/eaf64f94-en.

[3] Plyushteva, A. and T. Schwanen (2018), “Care-related journeys over the life course: Thinking mobility biographies with gender, care and the household”, Geoforum, Vol. 97, pp. 131-141, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.10.025.

[6] Siemiatycki, M., T. Enright and M. Valverde (2019), “The gendered production of infrastructure”, Progress in Human Geography, Vol. 44/2, pp. 297-314, https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519828458.

[13] Sustainable Mobility for All, (2019), Global Roadmap of Action toward Sustainable Mobility: Gender, http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/229591571411011551/Gender-Global-Roadmap-of-Action.pdf.

[9] Vaughan-Whitehead, D. and L. Caro (2017), Purchasing Practices and Working Conditions in Global Supply Chains: Global Survey Results, INWORK Issue Brief No. 10, International Labour Office, Geneva, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---travail/documents/publication/wcms_556336.pdf.