Willem Adema

Jonas Fluchtmann

Valentina Patrini

Willem Adema

Jonas Fluchtmann

Valentina Patrini

This chapter presents an overview of persisting gender gaps across OECD countries in and beyond education, employment, entrepreneurship, public life; it also covers additional policy areas such as energy and nuclear energy, environment, foreign direct investment and transport, among others. The chapter also discusses how recent crises are threatening progress in gender equality. It concludes with an overview of key policies adopted across OECD countries to advance in closing the existing gaps in gender equality.

The OECD has placed gender equality at the top of its agenda and actively promotes efforts to close remaining gaps through a wide portfolio of work on gender (Box 1.1). Building on Closing the Gender Gap: Act Now (OECD, 2012[1]), The Pursuit of Gender Equality: An Uphill Battle (OECD, 2017[2]) and the two Reports on the Implementation of the OECD Gender Recommendations (OECD, 2017[3]; 2022[4]), this publication is a further step in identifying progress in gender equality in OECD countries and beyond.

This volume highlights the following main findings:

Across the OECD, gender gaps persist in all spheres of public and social life. Even though girls and young women have higher educational attainment, men continue to be more likely to be employed, earn more on average, be in decision-making positions in the public and private sector, and engage more in entrepreneurship activities compared to women.

In recent years there has been progress in some policy areas to support gender equality, for example through earmarked parental leave for fathers, the introduction of pay transparency measures, and increased women’s representation in public and private leadership.

Gender mainstreaming has moved up the policy agenda. New policy areas – including foreign direct investment, the environment, energy, nuclear energy, trade, and transport – are increasingly examining gender equality challenges, thus helping to ensure that the gender lens is applied in a cross-cutting perspective.

Different crises have exacerbated gender equality challenges. The COVID‑19 pandemic has slowed progress, notably regarding gender-based violence. But it has also created opportunities for improving employment quality and flexibility. Russia’s large‑scale war of aggression against Ukraine, the associated rise in energy prices and the aggravating cost of living crisis are new challenges that countries must deal with through gender-sensitive policy making – as women are more likely to suffer heavier economic and financial consequences, such as energy poverty, due to gender gaps in savings and income.

More progress is needed in a range of areas. The list is long: tackling bias to support gender equality in education, a more equal sharing of paid work and unpaid work, more accessible and affordable early childhood education and care, effective flexible working arrangements for the compatibility of work and family responsibilities, better employment quality, gender equality in entrepreneurship, representation of women in public leadership and politics, better governance tools for gender equality, and more sustained efforts for widespread gender equality globally.

Gender equality cannot be achieved through siloed approaches. Real progress can only be achieved through a mainstreamed policy approach – which acknowledges the range of connections and interconnections between gender equality and a whole variety of socio-economic, geographic, institutional, policy and sectoral factors and stakeholders.

This overview chapter summarises existing and persisting gender inequalities, capturing the main policy thrust of initiatives undertaken to reduce these gaps across the OECD. This volume consists of 33 short chapters that display the wide range of increasingly cross-cutting gender-related policy issues. Box 1.1 illustrates how the OECD supports countries’ path towards gender equality.

Gender equality has long been a central focus of the OECD’s work. The 2010 OECD Gender Initiative drew attention to barriers to gender equality in the areas of education, employment, entrepreneurship, and public life. With the 2013 and 2015 OECD Recommendations on Gender Equality in Education, Employment, Entrepreneurship and Public Life the OECD set out policy principles and measures for policy makers and stakeholders to address such gender inequalities in their countries (OECD, 2017[5]; 2016[6]).OECD work has increasingly focused on the crosscutting nature of policy goals, not least the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Similarly, it has analysed specific dimensions of employment and entrepreneurship with respect to gender equality – such as women’s employment in the “social economy”, as well as the role of international trade for women entrepreneurs. Moreover, the OECD is constantly expanding the scope of its gender work to include sectors such as foreign direct investment (FDI), the environment, energy, nuclear energy, trade, and transport.

In this context, the OECD is supporting member countries in strengthening gender mainstreaming, governance and leadership, not least through tools such as the Policy Framework for Gender-sensitive Public Governance (OECD, 2021[7]) and the Toolkit for Mainstreaming and Implementing Gender Equality (OECD, 2018[8]).

The OECD also offers a range of statistical resources to analyse gender equality, reflecting progress but also areas where more action is needed. The OECD Gender Data Portal (https://www.oecd.org/gender/data/) includes selected indicators that provide information on gender disparities in education, employment, entrepreneurship, health, development, governance, digital and energy for OECD member countries, as well as partner economies including Brazil, China, India, Indonesia and South Africa. In addition, the OECD Family Database (https://www.oecd.org/els/family/database.htm) provides cross-national indicators on family outcomes and policies. Gender-disaggregated indicators are also available in other thematic databases, such as the OECD Going Digital Toolkit, (https://goingdigital.oecd.org/). The OECD is expanding the availability of gender-disaggregated data also through specific projects, such as a project initiated by the United States to extend coverage of gender-sensitive data (http://www.oecd.org/gender/gender-data-expansion.htm).

The OECD has been instrumental in supporting the G7 and G20 in their focus on gender equality, for example, by helping define the target to reduce the gender gap in labour force participation by 25% by 2025, which was adopted by G20 Leaders at their 2014 Brisbane Summit (OECD et al., 2014[9]; OECD, 2022[10]). Recently, the OECD also prepared the G7 Dashboard on Gender Gaps to the G7 under Germany’s G7‑Presidency in 2022, including key indicators across a range of policy areas to track progress on gender equality (G7, 2022[11]). In addition to hosting working groups with a focus on gender, such as GENDERNET and the Working Party on Gender Mainstreaming and Governance, the OECD frequently engages experts and decision-makers in a variety of fora to advance the policy dialogue on gender equality – such as the 2022 Symposium on strengthening government capacities for gender-sensitive data and evidence.

On a global scale, the OECD developed the Social Institutions and Gender Index (SIGI) (https://www.genderindex.org/) in support of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which serves as an official data source on discrimination against women in social institutions across 180 countries and is gathered in collaboration with the World Bank Group and UN Women (SDG 5.1.1). The OECD tracks and analyses development financing in support of gender equality and women’s rights, using the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) Gender Equality Policy Marker (https://www.oecd.org/dac/gender-development/dac-gender-equality-marker.htm). Together with the ILO and UN Women, the OECD also constitutes the Secretariat of the multi-stakeholder Equal Pay International Coalition (EPIC) (https://www.equalpayinternationalcoalition.org/), which calls for equal pay for work of equal value by 2030 (SDG 8.5).

Gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls are critical to achieving equal human rights around the world (Chapter 2). Achieving gender equality is not only a moral imperative: in times of rapidly ageing populations and declining fertility rates, the inclusion of more women in the labour market and in leadership positions also is essential to boosting economic growth in the long run.

One of the great advances for girls and women over past decades has been in education. In OECD countries, young women now have a substantially higher educational attainment than young men: among 25‑34 year‑olds in OECD countries, 53% of women have attained a tertiary level of education in 2021 compared to 41% of men (OECD, 2022[12]). At school, girls usually fare better than boys in science and reading scores (see Annex Table 1.A.1); this relative advantage has been growing over recent years, while girls’ disadvantage in mathematics compared to boys has been declining (Chapter 8). Across subjects, it is most commonly boys who are low achievers, which undermines school-engagement and may contribute to their higher likelihood of leaving school early (Chapter 10).

However, gender stereotypes that exist at home, in the classroom, and in society contribute to continued gender segregation in the choice of study fields and career expectations (Chapter 9), as well as gender differences in financial literacy (Chapter 12). Despite their higher educational attainment, young women are still more likely than young men to pursue studies in fields relating to education, health, and welfare, and less likely to choose engineering, mathematics, or computing. Similarly to girls in education, women in vocational education and training (VET) less often pursue technical and engineering programmes but are more likely to participate in business and administration as well as health and welfare programmes (Chapter 11). Therefore, women tend to be mainly represented in human- and care‑centred educational pathways and occupations, which are typically characterised by lower pay compared to Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) occupations. For example, the teaching profession has become increasingly feminised, particularly at primary and secondary levels. Female dominated occupations may be paid less because they are undervalued, not because they are inherently less valuable.

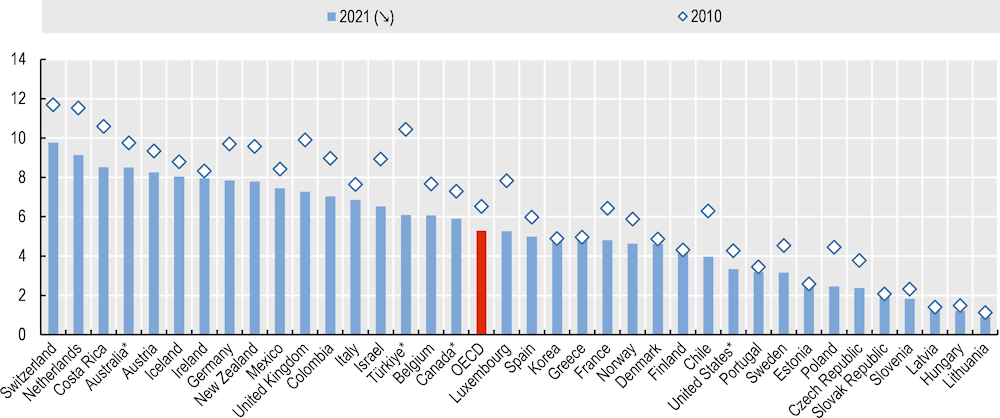

Labour market outcomes of men and women have converged substantially over the past decades. Nevertheless, working-aged women continue to fare worse than men in many labour market outcomes (Annex Table 1.A.1). For example, women in OECD countries are on average 10 percentage points less likely to be employed than men and still spend about five fewer hours per week in paid work (Figure 1.1). Men and women are also noticeably segregated across occupations and industries, with women often working in lower-paying service sector jobs, while men are disproportionally employed in more lucrative jobs, such as in the information and communications technology sector (Chapter 13). These gender differences in employment also culminate in a substantial gap in pay, with women earning about 12% less than men in 2020 on average in the OECD, measured at median earnings for full-time workers. Recent OECD research suggests that three‑quarters of this pay gap can be explained by firms paying men and women of similar skills differently, mainly reflecting differences in tasks and responsibilities and, to a lesser extent, differences in pay for work of equal value. The remainder of the gender pay gap is a result of the labour market segregation of men and women, particularly the concentration of women in low-wage firms and industries (Chapter 16).

The gender pay gap often widens when women become mothers. In all OECD countries, women spend a disproportionate amount of time on unpaid care‑ and housework compared to men, even though many countries have improved their family support systems in recent years. Despite exclusive periods of leave for fathers now being offered in many countries and in increasing uptake of leave by fathers, mothers still take disproportionately long leaves of absence from the labour market after giving birth (Chapter 23). Even when mothers are ready to return to the labour market, the unequal burden of work-family responsibilities and a lack of affordable early childhood education and care (ECEC) options (Chapter 24) means that many mothers work part-time and may thus miss out on career advancement and wage growth – or stay out of the labour market entirely (Chapter 13). Tax policy also plays a role. For instance, the progressivity of personal income taxes can reduce post-tax income gaps between men and women, as well as between full-time and part-time workers. However, at the same time, the Tax-Benefit system can create traps which disincentivise second earners (typically women) from entering or re‑entering the labour force, or that disincentivise part-time workers (also predominantly women) from working full-time (Chapter 25). Flexible working arrangements, including teleworking, also have a potential to support women’s labour market attachment; yet, the use of telework by men and women reflects prevailing gender norms and managerial cultures, that do not necessarily work to the advantage of women (Chapter 26). Good examples can be identified in specific sectors of the economy, such as the social economy, where gender gaps in pay and leadership are reportedly smaller than in the overall economy. Yet, in the social economy, salaries remain lower than in the wider economy for both men and women (Chapter 32).

Women still struggle to make it to the top in companies. Progress has been made in women’s presence on the boards of the largest publicly listed companies, which increased from around 21% in 2016 to 28% in 2021, partly due to more use of gender quotas and targets for corporate boards as well as complementary initiatives. But women’s share in management positions only increased from 31.1% to 33.7% between 2016 and 2021 (Chapter 17 and OECD Gender Portal, https://www.oecd.org/gender/).

Over the life‑course, all these gender differences compound and result in large gender gaps in life‑time earnings, a substantial gender pension gap, and an elevated risk of old-age poverty for women (Chapter 22).

* Latest data for Türkiye refers to 2020 and for Australia refers to 2018. Data for the United States refer to dependent employment only. Data for Canada refer to average actual hours worked for all above the age of 15 years.

Note: In figures throughout this publication, (➘) in the legend relates to the variable for which countries are ranked from left to right in decreasing order, and (➚) relates to the variable for which countries are ranked from left to right in increasing order.

Source: OECD Employment Database, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DatasetCode=AVE_HRS.

Women continue to be less likely than men to create a business, work in a new start-up, or be self-employed (see Annex Table 1.A.1). Although the gender gap in entrepreneurship was narrowing in most countries over recent years, in 2021 women were about 30% less likely than men to be starting or managing a new business across OECD countries. Women are similarly less likely to be self-employed than men – and even less likely to have employees (Chapter 28). Increasing women’s engagement in entrepreneurship can have significant benefits for gender equality and economic empowerment.

However, while microfinance is becoming more available for women entrepreneurs, there is still substantial unmet demand – with a market gap expected to grow to nearly EUR 17 billion by 2027 in the European Union (EU) alone (Chapter 29). On the other hand, large gender differences in financial literacy and financial resilience persist. Despite progress in financial education initiatives, challenges remain, including difficulties to reach women, women’s lower self-confidence in their financial skills than men, persisting gender stereotypes and social norms, and women’s limited time availability given their family responsibilities (Chapter 12).

The sectoral segregation of entrepreneurship activities of men and women also explains why men-led businesses are almost twice as likely to sell in foreign markets (Chapter 30). Women are also less engaged in trade, both as salaried workers and as entrepreneurs and business leaders. Trade lowers consumer prices and increases firms’ productivity and wages, and firms that trade are more productive and pay better wages than firms that do not trade. Women are therefore less likely to take advantage of the gains from trade, whether in terms of higher wages and salaries, or productivity gains for their businesses.

Even though women continue to be overrepresented in public employment – making up about 58% of all employees – they still face obstacles in their pursuit of leadership roles in the public sector. In 2020, the average percentage of women in senior management positions in public sector employment across OECD countries was only 37%, just a small improvement up from 32% in 2015. This indicates a persistent “leaky pipeline” (Chapter 14).

Despite advancements, women remain underrepresented in decision-making positions in public life (see Annex Table 1.A.1). Across the legislative, executive and judiciary branches of power, women still make up only about one‑third of leadership positions in the OECD on average, similarly to a decade ago (Chapter 18 and OECD Gender Portal). The COVID‑19 crisis served as a sharp reminder of the gender gap in decision-making, as women made up only 24% of the participants in the worldwide pandemic response ad hoc decision-making frameworks (OECD Gender Portal). Such an underrepresentation of women in critical decision-making positions risks an underappreciation of issues that affect women and families – in addition to contributing to the gender wage gap (Chapter 16). It may also result in limited support for policies that promote gender equality and women’s rights, as confirmed by evidence on a variety of sectors and policy areas – from environment (Chapter 5) to energy (Chapter 19).

Evidence on gender gaps is increasingly becoming available in different policy areas and sectors – including the environment, energy and nuclear energy, foreign direct investment (FDI) as well as transport – showing that there is still a long way to go to fully achieve gender equality. Beyond intrinsic specificities, all these sectors share a series of common barriers to gender equality. This includes a limited participation of women in the sectoral workforce and their even lower representation in leadership positions; existing gender stereotypes and discrimination as well as legal, technical and financial barriers affecting men and women differently; a limited representation of women in policy making; a lack of adequate frameworks and support systems allowing women to work at their full potential; and, an insufficient application of gender mainstreaming, implying that the linkages between each specific area and gender equality is often overlooked. In addition, limited data availability hinders the possibility to fully analyse gender gaps and take action accordingly.

For instance, when it comes to the environment, biodiversity loss, pollution, climate change and related extreme weather events threaten economic opportunities and increase health and well-being risks. While often overlooked, these environmental impacts affect men and women differently, exposing underlying discrimination, resource access inequalities and physiological factors that determine vulnerability. The agreed conclusions on “Achieving gender equality and the empowerment of all women and girls in the context of climate change, environmental and disaster risk reduction policies and programmes” at the 66th United Nations Commission on the Status of Women (CSW66) underline that the international community is aware of the existing gender gaps and the need for action (Chapter 5).

In the energy sector, women’s participation remains low with notable variations between subsectors. In the share of female senior managers, the energy sector is not far behind the global workforce, but the highest-level positions still have few or no women. Women also remain under-represented in energy policy making and public institutions, where the focus on gender equality is still limited (Chapter 19).

Similarly, despite the key contributions of women scientists and engineers to the nuclear and radiological fields, female representation in the nuclear energy sector is low – again, especially in science and engineering positions and leadership roles. At the current rates of female representation in new hires, attrition, and promotion, the sector will not reach gender balance. The lack of gender diversity represents a loss of potential innovation and growth and a threat to the future viability of the field (Chapter 20).

FDI tends to be higher in sectors with a lower share of women and higher gender wage gaps, and the impact of FDI on gender equality is not automatically positive, given existing barriers in terms of domestic legal and regulatory frameworks (Chapter 31). Official development assistance for private sector development, which includes FDI-related assistance, has grown steadily in recent years, but the link with gender equality objectives remains weak (Chapter 2).

Finally, improving gender equality both for women as transport users and in the transport workforce remains a challenge in many countries. First, women remain underrepresented in most transport-related industries (Ng and Acker, 2020[13]). Moreover, although gender is a significant determinant for the choice of transport modes (Ng and Acker, 2018[14]), transport infrastructure and services rarely take into account the mobility needs of women. This hampers women’s access to education, jobs, and other opportunities. The COVID‑19 pandemic has further exacerbated the existing gender inequalities in the transport sector (Chapter 21).

As the world continues to grapple with the effects of the COVID‑19 pandemic, countries have had to focus on supporting a strong and inclusive labour market, as well as dealing with the economic and social impacts of Russia’s large‑scale war of aggression on Ukraine. This requires adopting gender-responsive actions, as these multiple crises and the policy responses may affect men and women differently.

The COVID‑19 pandemic had profound gendered effects on labour markets in OECD countries and beyond. For example, as women make up the vast majority of nurses and midwives in OECD countries, and represent about half of doctors, they were at the forefront of the pandemic response (OECD, 2020[15]; Boniol et al., 2019[16]). At the same time, women were also over-represented in sectors that were most heavily hit by the pandemic. For example, they made up about 53% of employment in food and beverage services, 60% in accommodation services and 62% in the retail sector in the OECD in 2020 (ILO, 2022[17]; OECD, 2020[15]). The sectoral nature of the crisis also halted progress in gender equality in entrepreneurship, given the concentration of women-run businesses in personal services, accommodation and food services, arts and entertainment, and retail trade.

The OECD Risks that Matter 2020 survey showed that when schools and childcare facilities closed, mothers took on the brunt of the additional unpaid care work – and experienced labour market penalties and stress. For instance, more than six out of ten mothers of children under age 12 reported that they took on most or all of the additional unpaid care work caused by the pandemic, in comparison to a little more than two out of ten fathers, on average across the 25 OECD countries participating to the survey. Further, when fathers continued to be employed and mothers were not, gender gaps in unpaid work were the largest on average, while this was not the case when fathers were out of work and women remained employed (OECD, 2021[18]).

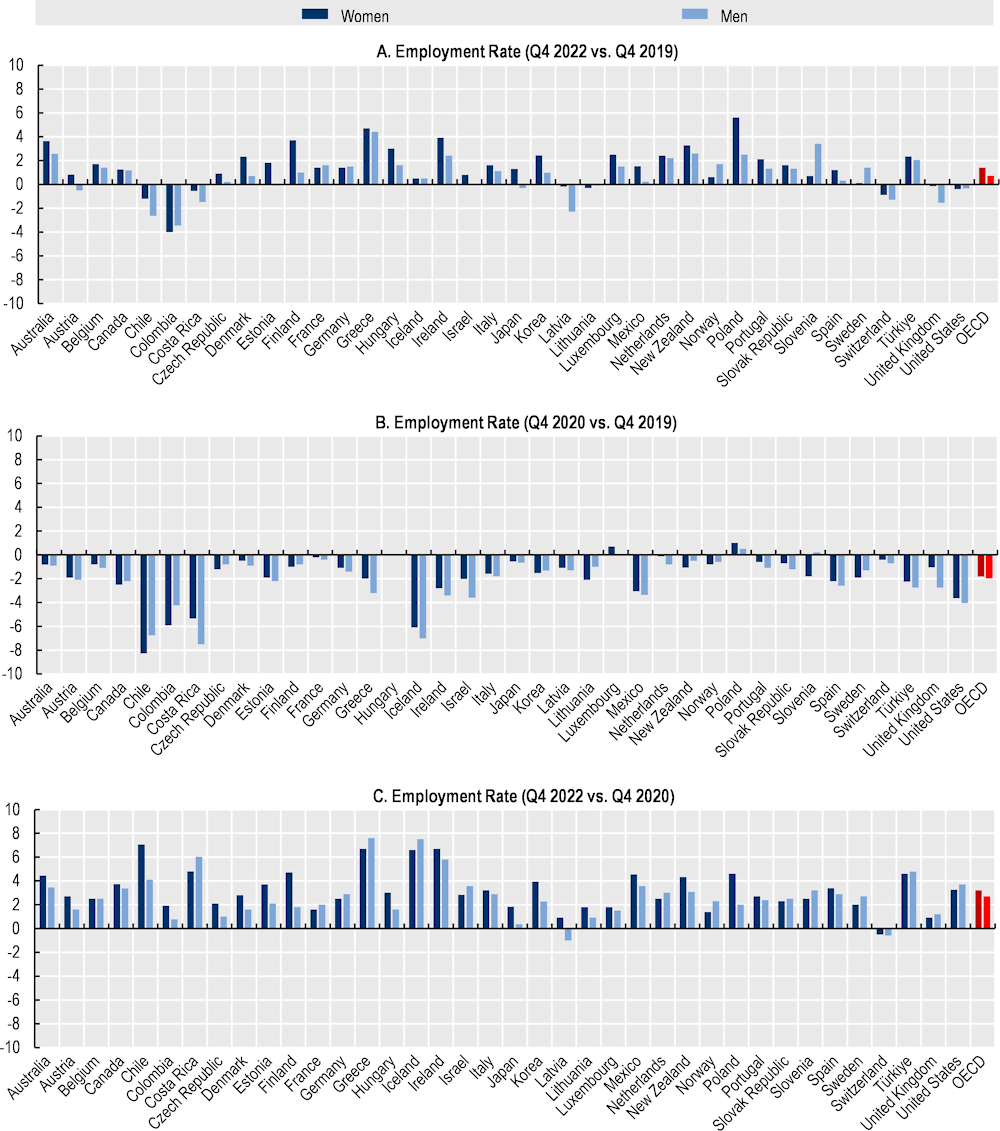

Despite these gendered labour market effects of the COVID‑19 pandemic, women’s employment outcomes were, on an aggregate level, not disproportionately more affected when compared to men’s (Queisser, 2021[19]). For both men and women, employment rates developed very differently over the first year of the pandemic and the subsequent period of recovery when containment measures were less strict. Initially, employment rates dropped by 1.8 percentage points for women and 2.0 percentage points for men between Q4 2019 and Q4 2020 (Figure 1.2, Panel B). Almost all OECD countries – except for Luxembourg, Poland and Slovenia – experienced a drop in employment rates for both men and women, with especially strong declines in countries outside the EU, where the adoption of employment retention programmes was less common. On average, the employment declines were similar for men and women, but some countries experienced particularly strong declines for women (e.g. Colombia and Chile), while others did for men (e.g. Costa Rica, Greece and Israel). Initially, employment losses were also particularly strong among young women (aged 15‑24), whose employment rates dropped by 3.9 percentage points on average across the OECD, compared to 3.2 percentage points for young men – see e.g. Risse and Jackson (2021[20]).

The period between Q4 2020 and Q4 2022 was marked by a strong recovery in economic activity, raising employment rates by 3.2 percentage points for women and 2.7 percentage points for men on average across the OECD (Figure 1.2, Panel C), while Switzerland was the only country in which employment fell for both men and women. The recovery was noticeably stronger for women in some countries (e.g. Chile, Estonia, Finland, Japan, Korea, Latvia and Poland), but in countries like Costa Rica, Greece, Iceland and Norway men had a noticeably larger increase in employment. Over the whole period (Figure 1.2, Panel A), most OECD countries reached pre‑recovery levels, often with slightly more noticeable improvements in female employment. Notably, this stronger employment recovery may have concurred with a shift towards better quality jobs. On an aggregate level across EU countries, for example, there has been some signs of a transition from female employment in low-paid in-person service sector jobs to better paying knowledge‑intensive jobs (Eurofound, 2022[21]).

Note: Data for EU countries are affected by the implementation of the new Integrated European Social Statistics Framework Regulation (IESS FR) in 2021, which, among changes in sampling and the structure of the questionnaire, adjusted the definition of employment, particularly in relation to maternity-, paternity- and parental leave. For Türkiye, Q4 2022 data refers to Q3 2022.

Source: OECD Short-term Labour Market Database, https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=35253.

Russia’s large‑scale war of aggression against Ukraine has led to huge losses of life, and inflicted life‑changing injuries among civilians and the military – especially men, and a massive displacement of people – especially women and children. An estimated 12 million people have become displaced in Ukraine and abroad. By early-January 2023, almost 5 million have registered for Temporary Protection in the EU alone. Because of a general mobilisation in Ukraine, which prevented most men aged 18 to 60 from leaving the country, the refugee inflows from Ukraine are comprised mainly of women, children, and elderly people; in virtually all host countries, at least 70% of adult Ukrainian refugees are women. Although there has since been some return migration, these historic migration flows present a huge challenge for OECD countries, not least in terms of integrating millions of women and children into society and the labour market (OECD, 2022[22]) (Chapter 15).

Refugee women may suffer from a “triple disadvantage” as the challenges related to gender, immigrant status and forced migration add up, or even mutually reinforce each other (Liebig and Tronstad, 2018[23]). Ukrainian refugee women, however, have some characteristics that facilitate their integration prospects: they have benefitted from often immediate labour market access in OECD countries, their educational profile is often conducive to finding employment, and they have been able to leverage existing social networks in host countries. Early evidence on the labour market inclusion of Ukrainian refugees indicates that their entry to the labour market has been faster than for other refugee groups in the OECD (OECD, 2023[24]). Yet, these good early outcomes are not necessarily an indicator of long-term success. Moreover, despite the relatively swift entry, much of the early employment uptake has been concentrated in low-skilled jobs, which is why skills mismatches are widespread (OECD, 2023[24]). In addition, care obligations can impede labour market participation of Ukrainian women.

Ukrainian refugee women’s labour market integration will be shaped by a complex interplay of both favourable circumstances and limiting barriers. While there is no doubt that Ukrainian women are better positioned than many other refugee women, there is likely a need to implement gender-sensitive and targeted integration measures to ensure their successful labour market integration at skill-appropriate levels. This also hinges critically on the availability of adequate childcare services and the integration of Ukrainian children into national school systems (OECD, 2022[25]; 2022[22]; 2022[26]).

Despite strong employment growth and far-reaching labour shortages during the recovery from of the COVID‑19 pandemic, real household disposable income growth was already under pressure in 2021 due to rising prices caused by disrupted supply chains. This trend continued into 2022, when energy markets were sent into turmoil and supply chains were further disrupted by Russia’s large‑scale war of aggression against Ukraine – particularly for food and other essential goods. This exacerbated the inflationary pressures that were already present due to the pandemic, so much so that in the first half of 2022, inflation reached levels not seen in decades in many OECD countries – almost 10% in the OECD as a whole and only expected to slowly decline in 2023 and beyond. This has eroded the living standards across households in the OECD as nominal wage growth remained modest despite the tight labour markets.

The impact of inflation and cost of living crisis is felt disproportionately by lower-income households, which have been hardest hit by the COVID‑19 crisis (Immervoll, 2022[27]; OECD, 2022[26]). As women typically earn lower incomes, they are also more likely to experience (energy) poverty than men. In the EU, for example, a larger percentage of women than men had unpaid energy bills since the onset of the COVID‑19 pandemic, but particularly so once energy prices surged in response to Russia’s large‑scale war of aggression against Ukraine (Eurofound, 2022[28]).

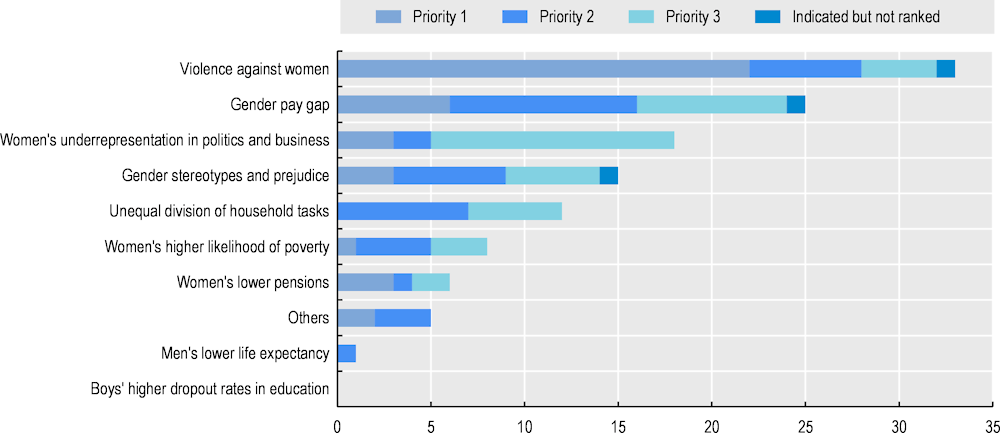

Eradicating stubborn inequalities between men and women remains a top priority in the OECD, not least since the adoption of the 2013 and 2015 OECD Gender Recommendations. The 2021 OECD Gender Equality Questionnaire asked countries to identify the most pressing gender equality issues they face. 33 out of 41 national government respondents reported that violence against women remains the priority issue in promoting gender equality, particularly since it rose in severity during the COVID‑19 pandemic. The second most pressing issue is closing the gender wage gap (25 respondents), followed by addressing women’s underrepresentation in politics and business (18 respondents) and addressing gender stereotypes (15 respondents) (Figure 1.3). This is very similar to the priority ranking that emerged among Adherents to the 2013 OECD Gender Recommendation in 2016 (OECD, 2022[4]; 2017[3]).

Note: The 2021 OECD Gender Equality Questionnaire asked the 42 Adherents to the 2013 OECD Gender Recommendation to select the priority issues in gender equality in their country from a list of topics. This is different from policy priorities that countries may have on work to be undertaken by OECD, OECD committees and their subsidiary bodies (e.g. the Working Party on Gender Mainstreaming and Governance). The horizontal axis indicates the number of respondents that ranked the issues among their top three priorities. Respondents also had the possibility to suggest additional priorities. These are reported in the category “others”, and include “unequal labour force participation”, “health difference between genders”, “undervaluation of female dominated jobs”, and “women’s safety”. Number of responses: 41, of which 1 did not identify priority 3, and 1 identified two items as priority 3.

One questionnaire per country, prepared by country officials.

Source: OECD (2022[4]), Report on the Implementation of the OECD Gender Recommendations, https://www.oecd.org/mcm/Implementation-OECD-Gender-Recommendations.pdf.

All of the above issues are influenced by persisting gender-related social norms, which guide stereotypes of men and women’s roles in society and which take time to change (OECD, 2019[29]; 2021[30]). According to a third of respondents to the 2021 OECD Gender Equality Questionnaire, traditional views on within-household distribution of earnings, women’s work and family life, as well as men and caregiving are still prevalent in their countries. More specifically, “the idea of a father being the primary caregiver” is opposed in 28% of responding countries, “the idea that family life suffers when a woman works full-time” is supported in 34%, and “the idea of a woman earning more income than her husband” is unacceptable in 25%. Nonetheless, respondents also stressed important progress in these attitudes over time, especially in the perceptions of the within-household distribution of earnings (OECD, 2022[4]).

Sexual harassment and gender-based violence (GBV) are among the most abhorrent threats to women’s health, safety and well-being. It is estimated that more than one in four women experience sexual and physical violence in their lifetime – one of the most severe forms of gender inequality in the world (Chapter 6). However, a major bottleneck to effective action against gender-based violence is the lack of sufficient data and statistics, as cases of intimate partner violence are heavily underreported.

Recent years have been marked by increasing visibility and public pressure on policy makers to act. Despite efforts to protect women’s safety and well-being, legislative progress, strategic planning, policy co‑ordination, and long-term investment in services have often been uneven across OECD countries, limiting the effectiveness of public measures (OECD, 2019[31]). The COVID‑19 pandemic has further highlighted the need for major efforts to eradicate GBV, showing that it remains “a pandemic within a pandemic”, and some countries have taken action accordingly (OECD, 2022[4]; 2022[26]). In parallel, new forms of GBV, such as online harassment and stalking, are strongly emerging.

As an example of a major persisting barrier, survivors of GBV often face substantial administrative and bureaucratic challenges of service delivery, by having to navigate a complex web of social services offered by a range of providers. Co‑ordinating multisectoral solutions to GBV is key (Chapter 7). However, less than half of OECD countries report that they are promoting and/or investing in such integrated service delivery in healthcare, justice, housing, child-related services, and income support (OECD, 2023[32]). Some countries provide targeted mental health supports and connected services deployed from hospitals, which are often the first access point for women escaping violence. There is also emergency or longer-term housing support for women and children fleeing violence in many countries, but this often means that survivors must uproot their life. Increasing focus in also put on police services, for example by requiring them to contact support services.

Workplace violence and harassment, including sexual violence and sexual harassment, also remain a key threat to women’s safety on the job. Many governments have recently introduced new or improved existing laws to combat and curtail workplace sexual harassment (e.g. Australia, Canada, Costa Rica, Denmark, France, Greece and Japan). Some countries have also developed national roadmaps for the prevention of violence and harassment in employment or made legislative efforts to tackle online harassment.

OECD countries have acted to rectify long-standing, skewed gendered experiences in education that have affected labour market outcomes of men and women over many years. Countries have renewed their efforts to get more girls to study STEM subjects, to involve teachers in efforts to encourage students to follow non-stereotypical career paths, to improve learning materials, and to train teachers in gender-sensitive practices. For example, Sweden updated its preschool curriculum to include a focus on combating gender patterns that limit children’s development and opportunities, and Finland now requires authorities and other stakeholders in education and training to promote gender equality. Various countries have also enhanced financial literacy instruction for women and encouraged them to enrol in adult and vocational education programmes, especially in STEM professions. However, this has made only modest improvements to the current gender disparities in educational attainment. Overall, parents, teachers and employers need to become more aware of their own conscious or unconscious biases so that they give girls and boys equal chances for success at school and beyond. In parallel, education systems should tackle issues of disengagement and lack of motivation early on, devoting adequate attention and resources to the issue (Chapters 8, 9 and 10).

The disproportionately high burden of unpaid care and non-care work on women’s shoulders is another indication of the stubborn gender inequalities in the labour market and at home. Policies need to break down gendered stereotypes around caregiving by better supporting fathers’ leave‑taking and ensure that mothers have access to (well-) paid employment-protected leave, while avoiding entitlements that discourage mothers’ return to work. Since the adoption of the 2013 OECD Gender Recommendation and by April 2022, many OECD countries have made progress in changing their family policies to encourage more fathers to take leave to care for children over longer periods. For instance, Austria, Belgium, Colombia, the Czech Republic, France, Greece, Italy, Korea, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and Switzerland have introduced or extended paid paternity leave entitlements, while Canada, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Iceland, the Netherlands, Korea and Norway introduced earmarked and non-transferable rights of leave for fathers or increased incentives for both parents to take leave. Since April 2022, there have been further reforms of parental leave systems in various countries, including Australia, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Japan, the Netherlands and the Slovak Republic (Chapter 23).

Following these developments, more fathers take paternity and parental leave around the birth of their children today than about a decade ago. However, the total duration of these absences pale in comparison to the time that mothers are on maternity- and parental leave, which means that most of the care burden remains on women’s shoulders. Furthermore, very few countries have made changes to Tax-Benefit systems that would have an impact on the gendered division of unpaid work. For example, Estonia switched from a household-based to an individual-based tax system, and Luxembourg introduced the option for individual income taxation (Chapter 25).

Many countries also continue to offer public supports for early childhood education and care (ECEC) in an effort to boost the financial incentives for fathers and mothers to work. For example, the Government of Canada is investing in a Canada-wide, affordable, high-quality and inclusive community-based early learning and childcare system with provincial, territorial and Indigenous partners. Key targets include achieving an average parent fee for regulated childcare for children under six of CAD 10-a-day and creating over 250 000 new childcare spaces across the country by March 2026. Other countries, such as the Czech Republic, Germany and Hungary have increased public funding of ECEC, while Australia, Chile, Greece, Ireland, and others, have introduced or expanded childcare subsidies or allowances. However, in many countries, the cost of ECEC remains a considerable barrier to (mothers’) participation in paid work, along with insufficient availability. To foster more gender equality in the labour market and at home, the availability, cost and quality of ECEC services must all increase (Chapter 24).

Flexible working arrangements – such as part-time employment, teleworking, flexitime or job-sharing – offer working parents to accommodate caregiving responsibilities, especially in cases where good quality ECEC is not available or affordable. While this can have positive effects on workers’ well-being and productivity, it can also carry a stigma with colleagues and employers who assume boundaries between work and the private might blur during teleworking arrangements. Parents who telework may face increased caregiving burdens if they do not have access to childcare (Chapter 26).

To facilitate a better compatibility between parenthood and labour market careers, some governments have recently strengthened teleworking regulations and expanded the rights of all workers to request flexible work arrangements, particularly since the start of the pandemic (e.g. Canada, Greece, Lithuania and Spain). Despite such efforts, gendered patterns in the use of parental leave and flexible work arrangements persist, as women continue to be more likely to work part-time than men. Simply promoting flexible work is not enough, as policies must ensure that these arrangements do not carry negative effects on careers and pay development and that the stigma of part-time work is reduced. Governments should also consider how to encourage parents of very young children to better share part-time work on a time‑limited basis (OECD, 2019[33]).

To advance towards more equality in pay, many countries have implemented policies over recent years, in particular pay transparency tools. Such measures spread awareness of the gender pay gap and can support a convergence in pay for similar work. When pay transparency measures are well designed and implemented, they can help highlight and combat discrimination in pay for equal work.

As of 2022, more than half of all OECD countries mandate private sector firms comply with gender-disaggregated pay reporting requirements or gender pay audits for private sector companies. Within this group, ten OECD countries have implemented comprehensive equal pay auditing processes that apply to a pre‑defined set of employers (Canada – under the Pay Equity Act, Finland, France, Iceland, Ireland, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland). Some countries apply more limited tools, such as requiring analysis of gender pay gaps in the process of labour inspections (Costa Rica, the Czech Republic, Greece and Türkiye), while others require companies to report gender statistics on outcomes other than pay, such as the gender composition of the workforce – a practice in 13 OECD countries (Chapter 27). Of course, it is important to note that pay transparency tools must be part of a comprehensive effort to combat gender gaps in pay – simply revealing the presence of a pay gap will do little to mitigate pay inequity that has built up over years of educational and workplace choices.

As part of global efforts to ensure equal pay, over the past years, an increasing number of governments, social partners, academia, the private sector and civil society organisations from OECD and non-OECD countries have joined the Equal Pay International Coalition (EPIC) (see Box 1.1). There, Members share policy practices, tools and experience to advance equal pay. In this context, the Swiss “Logib” tool (https://www.logib.admin.ch/home) – which usefully offers, free of charge, two modules for companies of different sizes to self-assess their gender wage gap – was identified as a good practice.

Over recent years, some countries have made progress in improving the job quality for some vulnerable workers, particularly for those that are predominately female‑dominated and/or in informal work arrangements. For example, following other countries that implemented similar policies since the early 2000s, Italy introduced a pay cheque system, through which private households can pay for domestic services in 2017. This improved labour protection and access to social security for household service workers that would otherwise be likely to work informally (OECD, 2021[34]). Other countries, such as Mexico, Korea and Switzerland made progress in guaranteeing labour rights for informal workers; Chile, Costa Rica France and Ireland and Spain advanced in extending social security access to more informal workers; Mexico and Spain ratified the ILO Convention on Domestic workers; and Türkiye recently launched an initiative to support women’s participation in formal employment.

OECD countries have made some progress in increasing the representation of women in corporate leadership positions. On average, countries that have initiated mandatory quotas and/or voluntary targets for board composition in listed companies have achieved a greater level of gender diversity on boards than other countries over the last decade. For example, France, Germany, and Italy have made some of the biggest gains, with the support of both board quotas and disclosure requirements. However, these measures sometimes yield unintended side effects – for instance, not leading to more women holding board director positions, but rather to more women serving on multiple boards.

Complementary measures have also been used to increase gender diversity on boards and in senior management in both the public and private sectors. Approaches include training and mentorship programmes, networks, private‑sector initiatives, relevant listing rules, role model schemes, peer-to-peer support, as well as advocacy initiatives to raise awareness, overcome biases and cultural resistance, and develop the female talent pipeline. Some countries with (e.g. Italy and Spain) or without quota or targets in place (e.g. New Zealand) have achieved significant progress through such additional initiatives. Yet, further progress is needed to achieve an equal distribution of men and women in positions of corporate decision making and leadership (Chapter 17).

Governments continue to invest in initiatives to address market and institutional failures that hold women back in entrepreneurship activities. Policy interventions that are tailored to the diverse needs of women entrepreneurs can be effective both on the supply side (e.g. gender bias in banking, investor preferences, and negative social attitudes) and the demand side (e.g. access to entrepreneurship training, networks and mentorship).

Governments can use, scale up and further develop the suite of traditional policy measures (e.g. loan guarantees, investor readiness training) to address persistent barriers faced by women entrepreneurs on both the supply- and demand-side of financial markets. Some countries such as Australia, Canada, Costa Rica, the United Kingdom and the United States have implemented policies that address the overall entrepreneurial ecosystem, enhancing gender inclusivity to ensure that women entrepreneurs benefit from existing supports. An acceleration in the use of digital platforms has been another key development in recent years. Governments can consider new approaches to improve access to finance for women entrepreneurs, such as microfinance (relevant examples can be found in eastern EU countries and in Central and South American countries) and fintech (relevant examples can be found in Spain and Sweden). Similarly, there are various areas where governments can support women business leaders in their export journeys, including making trade agreements more gender-sensitive and applying a gender lens to trade promotion, among others. Domestic policies that favour women’s participation in labour markets should complement gender-sensitive trade policies (Chapter 30). Overall, to facilitate knowledge sharing and policy transfer, governments must improve the measurement of the impact their policies have on women entrepreneurs (Chapters 28 and 29).

OECD countries have taken steps to improve gender equality in public leadership, including through leadership targets and quotas, mentorship, networking, capacity-building programmes, and active recruitment of women for leadership positions. For example, Portugal has adopted a 40% quota for women and men in senior leadership positions in public employment in 2019. Other OECD countries have also launched measures to improve work-life balance for parliamentarians, to measure women’s representation in the judiciary, and to tackle harassment and gender-based violence in politics.

However, more significant and sustained efforts are needed to achieve gender balance at the top in politics and judiciary. Promoting inclusiveness within elected bodies requires a mix of mandatory and voluntary instruments, incentives, and sanctions (e.g. targets, quotas or pay reporting requirements); gender audits of parliamentary practices and procedures; efforts to eliminate cyber violence and harassment; raising awareness among legislators and society; addressing structural barriers to women’s participation in political life; and strengthening leadership skills to promote gender equality. In the judiciary, measures will need to ensure a gender-balanced talent pipeline across all levels, gender-sensitive hiring and promotion processes, and safeguard a gender-sensitive working culture (Chapter 18).

Gender equality and gender mainstreaming are gaining momentum in the political agenda. In recent years, there has been a growing commitment to promoting gender equality and gender mainstreaming in public life. This has included the development of legal and policy frameworks to support these goals, including specific national strategies for gender equality, as well as efforts to embed a gender perspective in governance and policy-making processes (Chapter 3). Governance tools and requirements for gender impact assessments, gender budgeting and gender-related considerations in public procurement and infrastructure decisions are increasingly being adopted. For example, Canada, Iceland, Italy and Portugal have recently introduced some form of gender budgeting, bringing the number of OECD countries having some gender budgeting measures in place to 23 in 2022, while Canada, Ireland, Latvia, the Netherlands, Portugal and Spain have introduced or revised the scope of Gender Impact Assessments requirements to inform decision-making (Chapter 4).

However, several obstacles still stand in the way of inclusive and gender-responsive policy making and improved policy results, including longstanding gender biases, a non-systematic application of governance tools, limited government capacities and a lack of gender-disaggregated data in many sectors. Without data, the situation is difficult to analyse and progress impossible to monitor. Governments must gather more gender-disaggregated data – including data from an intersectional perspective providing in-depth information on the situation of vulnerable groups and minorities – across all policy domains while assessing, monitoring, evaluating, and reporting on gender disparities. The COVID‑19 crisis has accelerated the shift towards data-driven, innovative, and digital governments, which presents a window of opportunity for producing accurate and timely data on gender equality in various policy areas. Governments will also need to be aware of the dangers that emerging technologies and artificial intelligence pose to gender equality, such as the transfer of persistent gender biases into the digital world, the emergence of new digital divides, and algorithmic discrimination against women. All above actions require adequate investments in capacity building for staff.

Beyond OECD countries, the extensive socio‑economic impacts caused by the global COVID‑19 pandemic reinforced gender inequalities (McKinsey Global Institute, 2020[35]; UN Women, n.d.[36]; 2020[37]). They disproportionately affected women in developing countries and risked reversing years of progress towards gender equality. It is no longer sufficient to work within existing structures and systems. Post-COVID‑19 recovery efforts and the recent global crises have reinforced the idea that, in order to build back in a stronger, greener, more sustainable and more gender-equal way, women must be included in all decision-making processes and the knowledge and experiences of women and girls must underscore future recovery efforts of all kinds.

Achieving SDG 5 on gender equality – as well as the rest of the SDGs – requires collective action and transformative change to address the unequal power dynamics, systemic barriers and discrimination embedded in laws, norms and practices. The 31 countries that are members of the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) – a unique international forum of many of the largest providers of aid – need to make gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls a policy priority in strategic frameworks on development co‑operation and/or in legislation, while addressing gender equality throughout the programme cycle and increasing their financial allocations dedicated to gender equality accordingly.

Other development actors such as multilateral organisations, regional development banks, development finance institutions, philanthropic organisations and private actors also have a critical role to play in supporting governments. Countries should work with local women’s rights organisations and feminist movements, with men and masculinities, and employ an intersectional lens to leave no one behind (Chapter 2).

Moreover, countries should define tailored solutions to tackle gender gaps in specific regions. The example of the Middle East and North African (MENA), for instance, shows the potential of digitalisation to enhance women’s economic contribution in the region. This also means considering the risks that technologies pose to women’s economic empowerment in the region and the appropriate safeguard that would make digital a catalyst for inclusiveness (Chapter 33).

There is increased awareness of the need to promote gender equality in all socio-economic spheres and the relevance of gender mainstreaming across sectors – encompassing connected issues such as competition, corporate governance, digital transformation, health, migration, pensions, governance, social institutions, taxation, trade, and well-being.

Analyses on FDI, environment, energy, nuclear energy and transport highlight that countries should intensify efforts to enhance the positive nexus between each of those areas and gender equality. Countries need to collect internationally comparable and regularly updated gender-disaggregated data – this will allow to identify and understand existing gender gaps in all sectors and policy areas, analyse policy outcomes and trends over time, as well as define gender mainstreaming strategies to embed gender equality objectives and tackle related barriers specific to each area. Long-term efforts are required to boost inclusion for a gender diverse workforce, to support women’s representation in leadership positions, to ensure a better representation of women in policy making and to adopt governance tools for gender equality (e.g. policy guidelines, OECD Recommendations and other legal instruments, quality frameworks and gender mainstreaming) in every policy area. A gender lens also needs to be adopted in any operations that may involve interactions with other countries, including development co‑operation actions (Chapters 2, 5, 19, 20, 21 and 31).

A mainstreamed policy approach to gender equality is key for sustainable progress. Public policies cannot afford to disregard the intertwined nature between specific policy areas and gender equality objectives. Key actions encompass supporting efficient co‑operation between stakeholders; breaking existing siloed approaches; raising awareness on the link between gender equality and any specific policy objective, area and sector; producing new gender-sensitive data on these issues; shedding light on the contribution of gender equality to employment and economic growth; addressing the inequalities that intersect with gender; and appropriately enhancing governance structures, tools and capacities, co‑ordination and mainstreaming mechanisms, as well as data collection tools.

Gender equality is not only a moral imperative: it can also translate into employment and economic growth. Increasing the integration of women into the labour market has the potential to boost labour input and to improve productivity by better matching workers to jobs and making more efficient use of the available female talent pool. Given the challenges posed by population ageing and declining fertility rates, which are leading to shrinking workforces in many OECD countries, boosting female employment could be a crucial factor in maintaining economic growth and living standards in the coming decades.

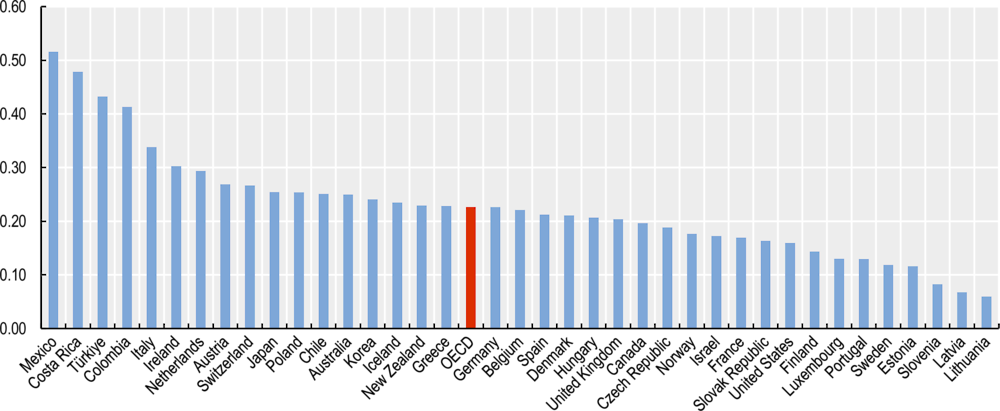

Efforts to increase women’s engagement in paid work beyond what is already projected for the future promises a substantial boost to economic growth. To illustrate this, Figure 1.4 presents economic output projections following a convergence of male and female labour participation and working hours across different 5‑year-age‑groups by 2060, most of which implies an increase in female labour force participation and working hours to male levels – with an exception of elderly women in Estonia, see OECD (2022[38]). These forecasts are based on OECD labour force projections in conjunction with a simplified version of the OECD Long-Term Model (Guillemette and Turner, 2018[39]; 2021[40]), where changes in annual growth in potential GDP per capita are estimated under different labour market outcomes (OECD, 2022[4]). Across the OECD, a simultaneous closing of gender gaps in labour force participation and working hours may increase potential GDP per capita growth by additional 0.23 percentage points per year, resulting in a 9.2% overall boost to GDP per capita relative what baseline projection estimate for 2060.

The effects of the different scenarios on potential output growth by 2060 are very heterogeneous across the OECD (Figure 1.4), depending strongly on the underlying gender gaps in labour force participation and working hours today. Countries which have substantial gender gaps in labour force participation or working hours could see the strongest boost to annual economic growth. For example, Colombia, Costa Rica and Türkiye may see more than 0.40 percentage points of additional GDP growth per year – corresponding to economic output that between 17 and 20% larger than expected for 2060. Mexico could even expect 0.52 percentage points added to annual output growth, which would add 22% to its GDP in 2060. Countries that have much smaller gender gaps would see a more muted, but still noticeable, boost to economic output. For example, Latvia, Lithuania and Slovenia could expect an additional 0.06 to 0.08 percentage points of annual GDP growth, adding about 2 to 3% to their economic output in 2060.

Note: The projections assume that labour force participation and working hours gaps close by 2060. For labour force participation, this is based on convergence of male and female levels to the highest level for each 5‑year age groups in each country, following baseline labour force projections over the period 2022‑60. In the absence of future working hours forecasts, projections are based on convergence from a constant 2021 level (or latest year available). See OECD (2022[4]) for a description of the method and data used.

Source: OECD estimates based on OECD Population Data, https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?DataSetCode=POP_PROJ; OECD Employment Database, http://www.oecd.org/employment/emp/onlineoecdemploymentdatabase.htm; Employment Projections; and the OECD Long-Term Growth Model, https://doi.org/10.1787/b4f4e03e-en.

[16] Boniol, M. et al. (2019), Gender equity in the health workforce: Analysis of 104 countries, World Health Organization, https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/311314.

[21] Eurofound (2022), “Recovery from COVID-19: The changing structure of employment in the EU”, https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/sites/default/files/ef_publication/field_ef_document/ef22022en.pdf.

[28] Eurofound (2022), The cost-of-living crisis and energy poverty in the EU: Social impact and policy responses: Background Paper, https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/sites/default/files/ef_publication/field_ef_document/ef22077en.pdf.

[11] G7 (2022), G7 Dashboard on Gender Gaps, https://g7geac.org/g7-dashboard/.

[40] Guillemette, Y. and D. Turner (2021), “The long game: Fiscal outlooks to 2060 underline need for structural reform”, OECD Economic Policy Papers, No. 29, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/a112307e-en.

[39] Guillemette, Y. and D. Turner (2018), “The Long View: Scenarios for the World Economy to 2060”, OECD Economic Policy Papers, No. 22, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b4f4e03e-en.

[17] ILO (2022), Labour Force Statistics (LFS), https://ilostat.ilo.org/topics/employment/#.

[27] Immervoll, H. (2022), “Income support for working-age individuals and their families”, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/social/Income-support-for-working-age-individuals-and-their-families.pdf.

[23] Liebig, T. and K. Tronstad (2018), “Triple Disadvantage?: A first overview of the integration of refugee women”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 216, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/3f3a9612-en.

[35] McKinsey Global Institute (2020), COVID-19 and gender equality: Countering the regressive effects, https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/covid-19-and-gender-equality-countering-the-regressive-effects.

[13] Ng, W. and A. Acker (2020), “The Gender Dimension of the Transport Workforce”, International Transport Forum Discussion Papers, No. 2020/11, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/0610184a-en.

[14] Ng, W. and A. Acker (2018), “Understanding Urban Travel Behaviour by Gender for Efficient and Equitable Transport Policies”, International Transport Forum Discussion Papers, No. 2018/01, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/eaf64f94-en.

[41] OECD (2023), Gender wage gap (indicator), https://doi.org/10.1787/7cee77aa-en (accessed on 13 April 2023).

[32] OECD (2023), Supporting Lives Free from Intimate Partner Violence: Towards Better Integration of Services for Victims/Survivors, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d61633e7-en.

[24] OECD (2023), “What we know about the skills and early labour market outcomes of refugees from Ukraine”, OECD Policy Responses on the Impacts of the War in Ukraine, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c7e694aa-en.

[12] OECD (2022), Education at a Glance 2022: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/3197152b-en.

[10] OECD (2022), G7 Dashboard on Gender Gaps 2022: A Guide, https://g7geac.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/g7-dashboard-on-gender-gaps-guide-data.pdf.

[22] OECD (2022), International Migration Outlook 2022, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/30fe16d2-en.

[26] OECD (2022), OECD Employment Outlook 2022: Building Back More Inclusive Labour Markets, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1bb305a6-en.

[4] OECD (2022), Report on the Implementation of the OECD Gender Recommendations, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/mcm/Implementation-OECD-Gender-Recommendations.pdf.

[38] OECD (2022), The Economic Case for More Gender Equality in Estonia, Gender Equality at Work, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/299d93b1-en.

[25] OECD (2022), “The potential contribution of Ukrainian refugees to the labour force in European host countries”, OECD Policy Responses on the Impacts of the War in Ukraine, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e88a6a55-en.

[34] OECD (2021), Bringing Household Services Out of the Shadows: Formalising Non-Care Work in and Around the House, Gender Equality at Work, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/fbea8f6e-en.

[18] OECD (2021), “Caregiving in Crisis: Gender inequality in paid and unpaid work during COVID-19”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/3555d164-en.

[42] OECD (2021), Government at a Glance 2021, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1c258f55-en.

[30] OECD (2021), Man Enough? Measuring Masculine Norms to Promote Women’s Empowerment, Social Institutions and Gender Index, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/6ffd1936-en.

[7] OECD (2021), “Policy framework for gender-sensitive public governance”, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/mcm/Policy-Framework-for-Gender-Sensitive-Public-Governance.pdf.

[15] OECD (2020), “Women at the core of the fight against COVID-19 crisis”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/553a8269-en.

[33] OECD (2019), Part-time and Partly Equal: Gender and Work in the Netherlands, Gender Equality at Work, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/204235cf-en.

[29] OECD (2019), SIGI 2019 Global Report: Transforming Challenges into Opportunities, Social Institutions and Gender Index, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/bc56d212-en.

[31] OECD (2019), “Violence against women”, in Society at a Glance 2019: OECD Social Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/008fcef3-en.

[8] OECD (2018), “Toolkit for Mainstreaming and Implementing Gender Equality”, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/gender/governance/toolkit/.

[5] OECD (2017), 2013 OECD Recommendation of the Council on Gender Equality in Education, Employment and Entrepreneurship, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264279391-en.

[3] OECD (2017), Report on the Implementation of the OECD Gender Recommendations - Some Progress on Gender Equality but Much Left to Do, https://www.oecd.org/mcm/documents/C-MIN-2017-7-EN.pdf.

[2] OECD (2017), The Pursuit of Gender Equality: An Uphill Battle, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264281318-en.

[6] OECD (2016), 2015 OECD Recommendation of the Council on Gender Equality in Public Life, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264252820-en.

[1] OECD (2012), Closing the Gender Gap: Act Now, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264179370-en.

[9] OECD et al. (2014), “Achieving stronger growth by promoting a more gender-balanced economy”, Report prepared for the G20 Labour and Employment Ministerial Meeting, https://www.oecd.org/g20/topics/employment-education-and-social-policies/ILO-IMF-OECD-WBG-Achieving-stronger-growth-by-promoting-a-more-gender-balanced-economy-G20.pdf.

[19] Queisser, M. (2021), “COVID-19 and OECD Labour Markets: What Impact on Gender Gaps?”, Intereconomics, Vol. 56/5, pp. 249-253, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10272-021-0993-6.

[20] Risse, L. and A. Jackson (2021), “A gender lens on the workforce impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia”, Australian Journal of Labour Economics, Vol. 24/2, pp. 111-144, https://researchrepository.rmit.edu.au/esploro/outputs/journalArticle/A-gender-lens-on-the-workforce/9922062508501341.

[37] UN Women (2020), From insights to action: Gender equality in the wake of COVID-19, https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2020/09/gender-equality-in-the-wake-of-covid-19.

[36] UN Women (n.d.), COVID-19 and gender data resources, https://data.unwomen.org/COVID19.

Key indicators of gender gaps in education, employment and entrepreneurship, and governance (men – women)

|

Education |

Employment and Entrepreneurship |

Governance |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Gender gap in mean PISA reading scores (boys – girls) |

Gender gap in mean PISA mathematics scores (boys – girls) |

Share of women among masters’ graduates (%) |

Gender gap in the labour force participation rate (men – women) (p.p.) |

Share of women among managerial employment (%) |

Gender wage gap for full-time employees (%)* |

Share of women among self-employed with employees (%) |

Share of women among parliamentary representatives (%) |

Share of women among public sector employment (%) |

Share of women among central government senior management (%) |

|

|

Age group |

15‑year‑olds |

15‑year‑olds |

All ages |

15‑64 years |

All ages |

All ages |

All ages |

All ages |

All ages |

All ages |

|

Year |

2018 |

2018 |

2021 |

2021 |

2021 |

2021 |

2020 |

2023 |

2019 |

2020 |

|

Note |

1 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

|

|

OECD average |

-29.0 |

5.5 |

57.9 |

10.9 |

33.7 |

11.9 |

24.9 |

33.8 |

57.6 |

37.2 |

|

OECD std. dev. |

9.3 |

6.6 |

5.8 |

8.1 |

7.4 |

6.5 |

4.5 |

10.5 |

10.2 |

12.1 |

|

Australia |

-31.4* |

6.0* |

52.7 |

8.2 |

40.0 |

10.5 |

31.3 |

38.4 |

62.1 |

47.0 |

|

Austria |

-28.1* |

13.3* |

54.4 |

9.3 |

35.5 |

12.2 |

25.3 |

40.4 |

.. |

30.4 |

|

Belgium |

-21.7* |

12.1* |

56.6 |

8.0 |

35.4 |

1.2 |

26.2 |

42.7 |

57.2 |

21.1 |

|

Canada |

-28.9* |

4.9* |

56.4 |

7.0 |

35.6 |

16.7 |

27.0 |

30.7 |

63.3 |

44.6 |

|

Chile |

-19.8* |

7.5* |

56.8 |

20.6 |

30.4 |

8.6 |

21.5 |

35.5 |

55.7 |

.. |

|

Colombia |

-10.3* |

19.5* |

56.6 |

24.9 |

.. |

3.2 |

.. |

28.9 |

47.4 |

39.6 |

|

Costa Rica |

-14.4* |

17.7* |

59.2 |

23.8 |

40.2 |

5.2 |

.. |

47.4 |

50.7 |

38.1 |

|

Czech Republic |

-33.2* |

3.5 |

59.7 |

13.7 |

28.4 |

11.5 |

21.9 |

26.0 |

.. |

33.2 |

|

Denmark |

-29.3* |

3.9 |

56.1 |

6.1 |

28.2 |

5.0 |

20.7 |

43.6 |

69.6 |

32.2 |

|

Estonia |

-30.7* |

8.5* |

64.0 |

4.6 |

41.2 |

20.4 |

19.5 |

27.7 |

67.8 |

48.5 |

|

Finland |

-51.5* |

-6.1* |

60.9 |

3.2 |

36.5 |

16.0 |

24.2 |

45.5 |

71.0 |

38.0 |

|

France |

-24.9* |

6.4* |

54.7 |

6.2 |

37.8 |

15.0 |

27.0 |

37.8 |

63.8 |

30.8 |

|

Germany |

-25.9* |

7.1* |

53.5 |

8.1 |

29.2 |

14.2 |

24.7 |

35.1 |

55.5 |

32.5 |

|

Greece |

-42.1* |

0.3 |

61.4 |

15.4 |

29.6 |

5.9 |

28.2 |

21.0 |

47.9 |

52.9 |

|

Hungary |

-26.5* |

8.8* |

57.6 |

9.9 |

37.3 |

12.4 |

30.1 |

13.1 |

60.0 |

.. |

|

Iceland |

-40.6* |

-9.8* |

69.1 |

5.4 |

37.6 |

12.9 |

22.3 |

47.6 |

.. |

.. |

|

Ireland |

-23.2* |

5.9 |

55.9 |

9.7 |

38.0 |

8.3 |

26.9 |

23.1 |

.. |

35.6 |

|

Israel |

-48.1* |

-9.2 |

62.5 |

3.3 |

34.6 |

24.3 |

17.9 |

24.2 |

62.0 |

44.5 |

|

Italy |

-24.7* |

15.5* |

57.7 |

18.2 |

28.6 |

8.7 |

25.3 |

32.3 |

58.2 |

34.0 |

|

Japan |

-20.4* |

10.1* |

35.0 |

13.3 |

13.2 |

22.1 |

16.3 |

10.0 |

43.3 |

4.2 |

|

Korea |

-23.6* |

4.0 |

53.3 |

18.1 |

16.3 |

31.1 |

25.6 |

19.1 |

45.7 |

8.6 |

|

Latvia |

-32.8* |

6.8* |

64.2 |

5.8 |

45.9 |

24.0 |

.. |

29.0 |

67.0 |

56.2 |

|

Lithuania |

-38.7* |

-2.5 |

66.1 |

2.0 |

37.0 |

9.0 |

25.4 |

28.4 |

68.0 |

28.5 |

|

Luxembourg |

-29.3* |

7.5* |

51.4 |

6.5 |

21.9 |

.. |

29.7 |

35.0 |

39.6 |

25.0 |

|

Mexico |

-11.1* |

11.8* |

56.4 |

32.4 |

38.5 |

12.5 |

20.2 |

50.0 |

52.7 |

23.3 |

|

Netherlands |

-28.8* |

1.4 |

56.5 |

6.9 |

26.0 |

13.2 |

23.9 |

40.7 |

49.5 |

35.0 |

|

New Zealand |

-28.8* |

8.9* |

58.6 |

8.2 |

.. |

6.7 |

32.6 |

50.0 |

.. |

52.8 |

|

Norway |

-47.0* |

-7.0* |

57.4 |

4.4 |

33.5 |

4.6 |

23.3 |

46.2 |

69.6 |

43.4 |

|

Poland |

-32.8* |

1.4 |

66.7 |

13.4 |

43.0 |

8.7 |

29.9 |

28.3 |

60.6 |

45.2 |

|

Portugal |

-24.3* |

9.0* |

58.6 |

5.2 |

38.0 |

11.7 |

32.3 |

36.1 |

60.7 |

41.5 |

|

Slovak Republic |

-34.4* |

4.6 |

61.9 |

8.0 |

37.3 |

11.7 |

23.9 |

22.0 |

60.9 |

50.3 |

|

Slovenia |

-41.7* |

0.6 |

65.6 |

5.8 |

34.0 |

8.2 |

24.5 |

37.8 |

.. |

49.0 |

|

Spain |

-20.0* |

6.4* |

60.0 |

8.3 |

33.3 |

3.7 |

30.3 |

42.4 |

56.1 |

42.8 |

|

Sweden |

-34.3* |

-1.2 |

60.6 |

4.1 |

43.0 |

7.2 |

20.7 |

46.4 |

71.8 |

55.0 |

|

Switzerland |

-30.6* |

7.1* |

50.2 |

7.8 |

31.9 |

13.8 |

25.5 |

41.7 |

.. |

21.7 |

|

Türkiye |

-25.3* |

4.9 |

49.9 |

39.6 |

18.2 |

10.0 |

12.2 |

17.4 |

25.3 |

.. |

|

United Kingdom |

-20.1* |

12.2* |

61.2 |

7.2 |

36.8 |

14.3 |

28.1 |

34.5 |

66.3 |

42.0 |

|

United States |

-23.5* |

8.6* |

60.9 |

10.5 |

41.4 |

16.9 |

25.9 |

29.4 |

57.5 |

37.1 |

|

Argentina |

-16.1 |

15.4* |

60.5 |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

|

Kazakhstan |

-26.9 |

1.3 |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

|

Morocco |

-25.9 |

0.9 |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

Note: Gender gap indicators are expressed as men’s outcomes minus women’s outcomes. The OECD average and standard deviation are the unweighted average and standard deviation for all OECD member countries with available data on the given measure. Values are shaded according to the size of women’s share relative to the OECD average share or according to the size of the gap relative to the OECD average gap. “(p.p.)” denotes measurement in percentage points; “(%)” denotes measurement in percentage terms.

Well above OECD average.

Well above OECD average.

Around OECD average.

Around OECD average.

Well below OECD average.

Well below OECD average.

1. Where marked with an *, the gender gap in the mean PISA score is statistically significant. Reading scores for Spain refer to PISA 2015.

2. See OECD (2022[12]), Education at a Glance 2022: OECD Indicators, https://doi.org/10.1787/3197152b-en. Data for Australia, Canada, Chile, Costa Rica, the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Korea, Mexico, Portugal, Türkiye and the United Kingdom refer to 2020 and data for Argentina to 2019.

3. See ILO (2021), Indicator 5.5.2 Metadata. Data for Australia and Türkiye refer to 2020, data for the United Kingdom refer to 2019 and data for Israel refer to 2017.

4. The gender wage gap is defined as the difference between median earnings of men and women relative to median earnings of men. See OECD (2023[41]), “Gender wage gap” (indicator), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/7cee77aa-en. Data for Belgium, Chile, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Portugal and Switzerland refer to 2020. Data for Ireland and Israel refer to 2019. Data for Iceland, Slovenia and Türkiye refer to 2018.

5. Data for the United Kingdom refers to 2019. Data for Australia, Chile, Korea and Mexico refers to 2017. Data for Israel refers to 2016. Data for Chile refer to 15+ year-olds.

6. See OECD (2021[42]), Government at a Glance 2021, https://doi.org/10.1787/1c258f55-en.

Source: OECD Gender Portal, https://www.oecd.org/gender/.