Social integration is difficult to measure. The indicators presented here are first related to citizenship take‑up (Indicator 5.1), participation in elections (Indicator 5.2), and host-country degree of acceptance of immigration (Indicators 5.3 and 5.4). The chapter then looks at the participation in voluntary organisations (Indicator 5.5), the perceived incidence of discrimination against immigrants on the grounds of ethnicity, race or nationality (Indicator 5.6) and the level of trust in host-country institutions (Indicator 5.7). Finally, it explores a range of indicators related to public opinion on integration (Indicators 5.8, 5.9 and 5.10).

Indicators of Immigrant Integration 2023

5. Immigrant civic engagement and social integration

Abstract

In Brief

A lower share of settled immigrants has host-country citizenship today than a decade ago in most countries and those who do, remain less likely to vote than the native-born

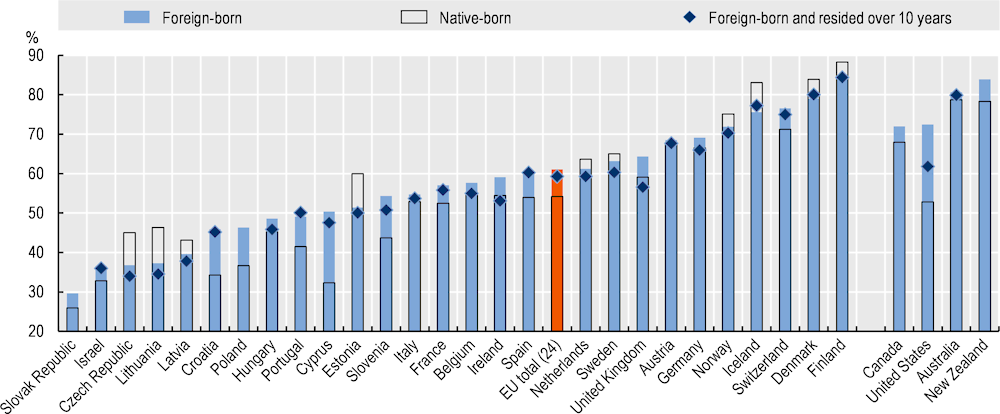

Slightly over half of settled immigrants, i.e. foreign-born with 10 years of residence in the country, have host-country citizenship in the EU and around four in five in the settlement countries, on average. Shares of such foreign-born with host-country nationality dropped between 2010 and 2020 in two‑thirds of countries – by 9 percentage points across the EU.

The acquisition of host-country nationality is less likely among individuals born in the same region. In fact, only 45% of immigrants from Europe have acquired EU host-country nationality and only 52% of LAC-born residents have citizenship in the United States. However, the acquisition rate is generally higher among immigrants from developing countries.

Almost three‑quarters of immigrants with host-country nationality took part in the most recent national elections in both the OECD and the EU – against four native‑born in five. In the Netherlands, German- and English-speaking European countries, voter turnout is higher among immigrant women than men, while the reverse is true among the native‑born.

Native‑born views on immigration have become more favourable

Half of the native born in the EU and Australia have no strong view – positive or negative – on immigration. In the United States and Korea, around 38% and 28% of the native‑born think their country should limit immigration to protect their way of life, while in the United States 35% were of the opposite opinion and in Korea 29%. The native‑born generally have more positive opinions when asked more specific questions on immigrants’ impacts on their country’s culture and, to a lesser extent, on its economy than to broad generic questions.

Views of the native-born have become more favourable towards immigration in most countries over the last decade. Young people tend to have more positive views than the elderly almost everywhere and are also more likely to interact with immigrants.

Direct social interaction with migrants is associated with more positive views. Compared to the relatively small size of their non-EU migrant populations, native‑born have widespread social interaction with the non-EU born in Southern European countries, Ireland and Denmark, but more limited interaction in the Baltic countries and Croatia.

Immigrants are less often active in voluntary organisations that the native‑born

Immigrants are less likely to join voluntary organisations than the native‑born in most countries. Gaps exceed more than 15 percentage points in Sweden, Switzerland and Germany. In Canada, Italy, Spain and the Czech Republic, by contrast, rates of participation in voluntary activities are rather similar.

Foreign‑born membership falls particularly short when it comes to trade unions, political parties and leisure groups. Immigrants are, however, more likely to join voluntary faith-based groups.

Perceived discrimination increased while immigrants generally trust the host-country institutions more than the native‑born do

In the EU, 15% of the foreign-born report feeling discriminated against on the grounds of ethnicity, nationality, or race. Shares are around 20% in Italy, France, the Netherlands, Korea and Canada. Shares are lowest in Central Europe and Ireland. Between 2010‑14 and 2016‑20, perceived discrimination increased in the EU, New Zealand and Canada, particularly among women. The reverse was true in the United States and Australia.

Younger and more recent migrants are more likely to perceive discrimination. The same is true among men in the EU and the United States. Perceived discrimination is particularly acute among immigrants from North and sub-Saharan Africa in the EU and Canada, while Latin American- and Asian-born migrants tend to be worse affected in Australia.

Given the often‑lower expectations towards institutions in the country of origin, immigrants are more likely than the native‑born to trust the police and legal system in two‑thirds of host countries. In the EU, immigrants from non-EU countries have greater levels of trust than EU-born in host-country institutions. EU-wide trust in public authorities has grown since the early 2000s, and generally more strongly among the foreign-born. However, immigrants’ trust in public authorities tends to decline with length of residence.

Factual knowledge on the evolution of integration outcomes remains limited and public opinion differs strongly by country

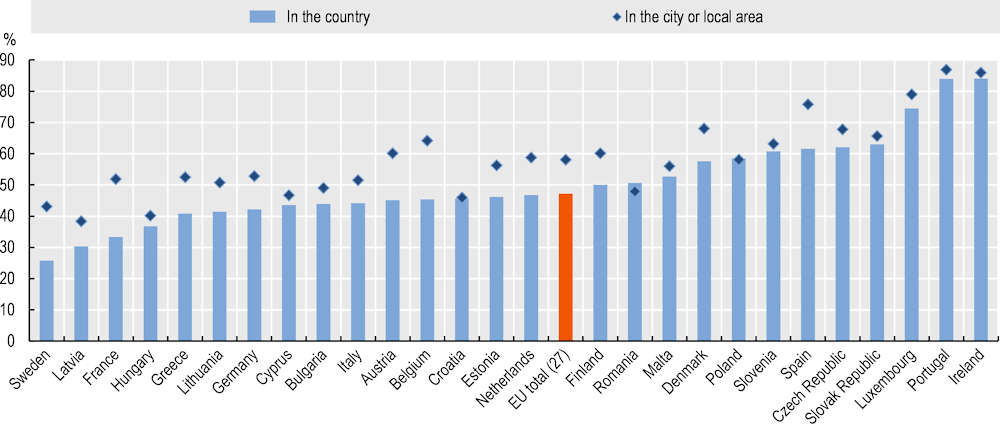

In 2021, 47% of EU citizens in the EU perceived the integration of non-EU migrants in their country as successful. Views were most positive in Ireland and some Central European countries, and most negative in Sweden, Latvia and France. Views of integration are always more positive at local than national level, with around three EU citizens in five saying that it is successful in their city or area.

Most EU citizens have distorted views on non-EU migrants’ characteristics and the evolution of their integration outcomes over the last decade. Whatever the indicator considered, less than 43% of respondents’ perceptions of the evolution of integration outcomes reflect the true picture. For example, despite an increase in shares of highly educated among the non-EU migrants in virtually all countries, most countries perceived the opposite, especially in France and in Central and Eastern European countries.

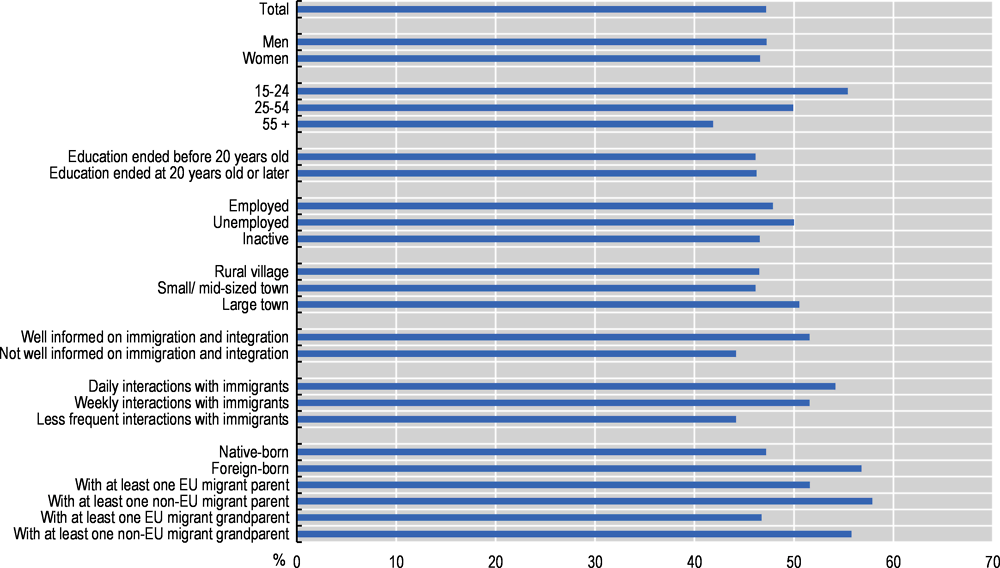

Different socio-economic groups share very similar views on the successful integration of non-EU migrants in their country. Gender, employment status and level of education have little direct association EU-wide. However, younger EU citizens, those living in cities and those who feel more informed and interact more extensively with non-EU migrants generally view their integration more positively.

European societies perceive language skills as a key factor for social integration and finding a job as the key obstacle but also acknowledge migrant specific needs

EU‑wide, the chief obstacle to integration according to EU citizens is finding a job. Two-thirds of respondents also think that the limited efforts of immigrants themselves to fit in and the discrimination against them are major obstacles to their integration in society.

Overall, among social factors, speaking one of the host country’s official languages is most frequently considered important for the integration of non‑EU migrants, followed by the sharing of host-country values and norms. Even higher shares of respondents, however, mention factors not directly linked with social integration, such as contributing to the welfare system and being educated and skilled enough.

5.1. Acquisition of nationality

Indicator context

The conditions under which host countries grant nationality vary widely. Many have recently given naturalisation and citizenship more important roles in the immigrant integration process.

As nationality at birth is usually not available, acquisition of nationality (also known as citizenship) relates here to the share of foreign-born who have resided in the host country for at least 10 years and hold its nationality. The duration of stay to be eligible for nationality in OECD and EU countries is generally no more than 10 years. Shares may be overestimated in countries with a large number of nationals born abroad (e.g. France, the United Kingdom, Portugal) or foreign-born individuals sharing the same national heritage and that had, or were conferred, citizenship upon arrival (e.g. Croatia, Germany, Hungary, the Slovak Republic).

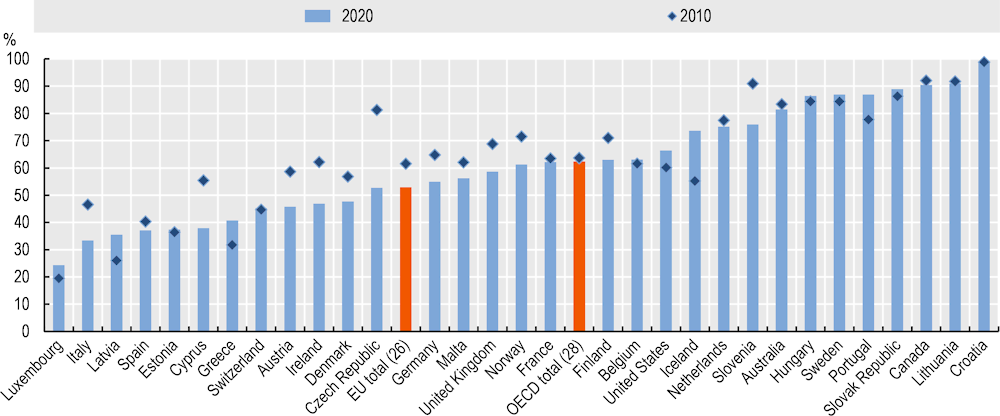

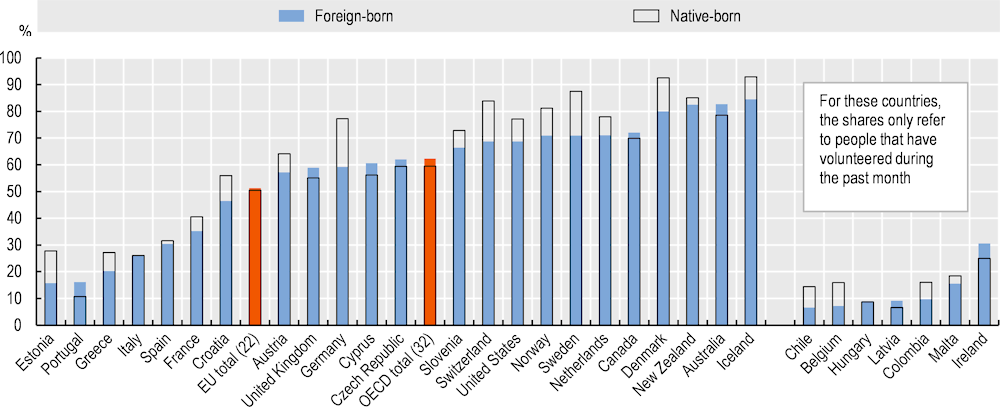

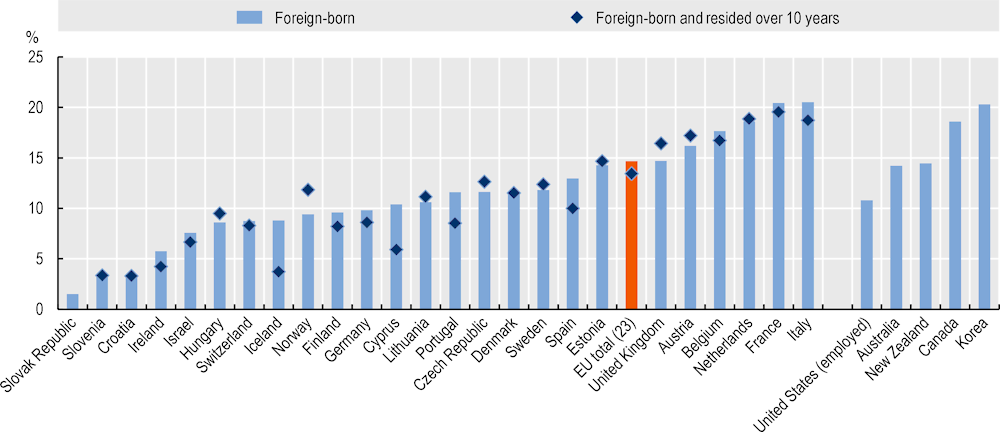

The share of settled foreign-born (over 10 years of residence) who have host-country citizenship is over one‑half in the EU and around two‑thirds in the United States. Shares are higher in: i) European countries where the foreign‑born population belongs to national minorities who enjoy automatic or streamlined access to nationality; ii) settlement countries, Sweden and Portugal, who all facilitate the acquisition of citizenship. By contrast, in countries where dual citizenship is not legally permitted (or was not until recently), immigrant citizenship rates are much lower – particularly in Luxembourg, many Southern European and Baltic countries. Immigrant women are more likely to have host-country citizenship than their male peers EU- and OECD‑wide (by 3 and 10 percentage points, respectively). This higher female rate is partly attributable to marriage to host-country citizens, a procedure that facilitates the acquisition of nationality.

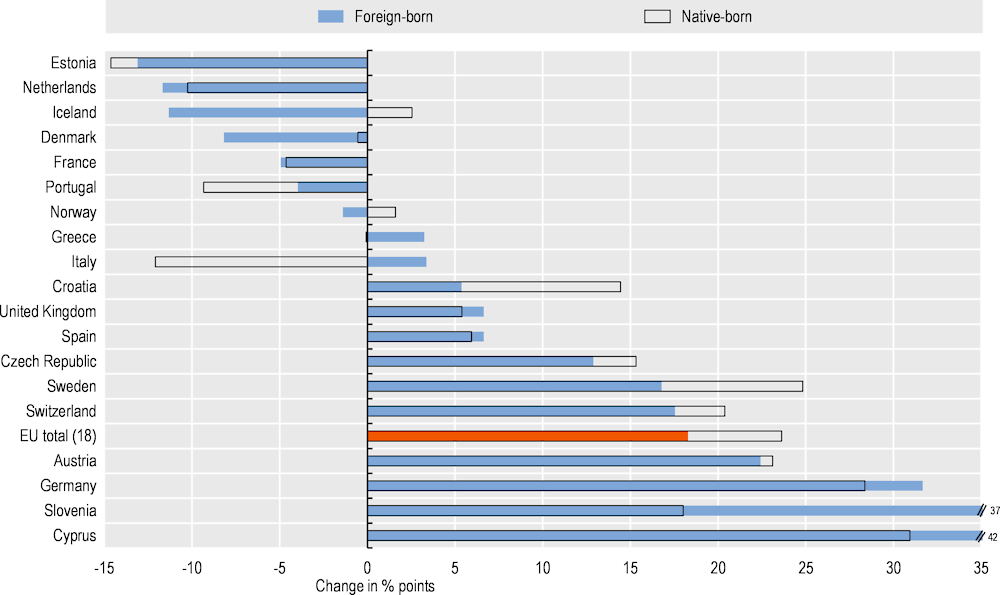

Shares of settled foreign‑born with host-country nationality dropped between 2010 and 2020 in slightly less than two‑thirds of countries – by 9 percentage points across the EU. This is partly attributable to tougher criteria for acquiring citizenship, particularly language proficiency, and to changes in the composition of migrants. In some countries, such as the Czech Republic, for instance, the decline is also due to mortality of elderly foreign-born who automatically obtained citizenship upon nation-building.

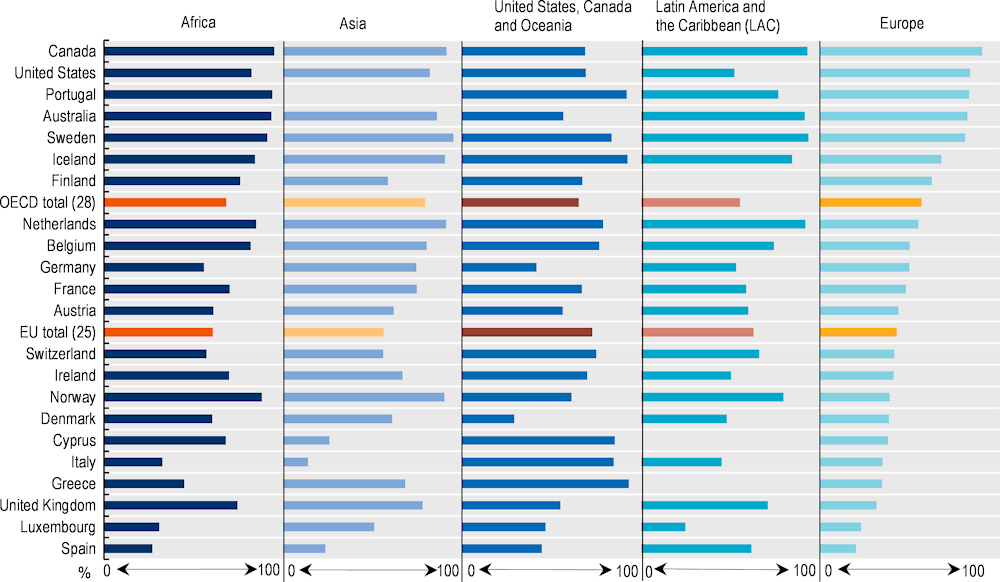

Immigrants born in the same region as their host country are less likely to have host-country nationality. In fact, only 45% of immigrants from Europe (see glossary) have host-country nationality in the EU, which is attributable to the EU legislation that enshrines freedom of movement between EU countries (see Indicator 8.14). In the United States, for example, only 52% of LAC‑born residents have citizenship, partly linked with the large share of irregular migrants from this region. Acquisition of citizenship is usually more widespread among the foreign‑born from developing countries. In two‑thirds of countries, African or Asian migrants account for the highest share of migrants with host-country nationality. Historical ties also affect the acquisition of citizenship, e.g. African and Brazilian migrants in Portugal and the LAC‑born in the Netherlands.

Main findings

Slightly over half of settled immigrants have host-country citizenship in the EU. Shares are higher in non-European countries, particularly in the settlement countries.

Shares of settled immigrants with host-country nationality dropped between 2010 and 2020 in slightly less than two‑thirds of countries – by 9 percentage points EU‑wide.

The acquisition of host-country nationality is less likely among individuals born in the same region of birth as the country of residence, and higher among those from developing countries.

Figure 5.1. Acquisition of nationality

Figure 5.2. Acquisition of nationality by region of birth

Notes and sources are to be found in the respective StatLinks.

5.2. Voter participation

Indicator context

For those who are eligible, immigrants’ participation in elections reflects their desire to have a say and play a part in the host country’s society by getting involved and choosing those who govern it.

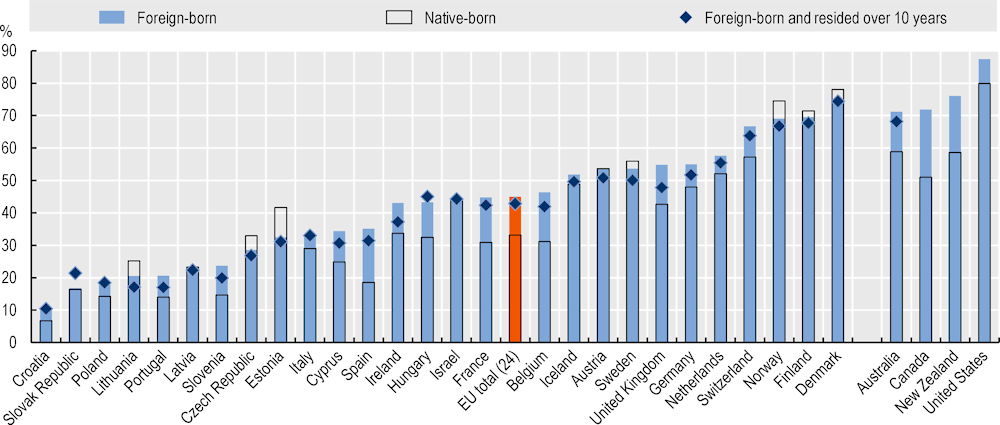

Voter participation refers to the share of eligible voters (with host-country nationality) who report that they cast a ballot in the most recent national parliamentary election in the country of residence.

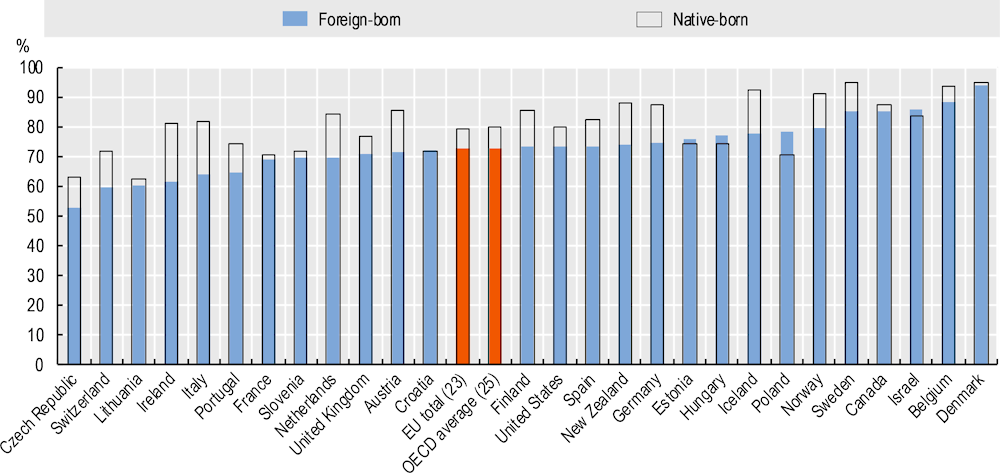

On average, 73% of immigrants with host-country nationality in both the OECD and the EU report that they participated in their host country’s most recent national elections – less than the native‑born rate of around 80%. Voter participation differs only slightly between the native‑born and the foreign‑born with host-country nationality in Israel, most Central and Eastern European countries, Denmark, or longstanding destinations like France and Canada. Turnout is higher among women than men among both foreign- and native‑born voters in around half of countries, but greater among immigrant women and native‑born men in the Netherlands, Austria, Germany, Switzerland and the United Kingdom.

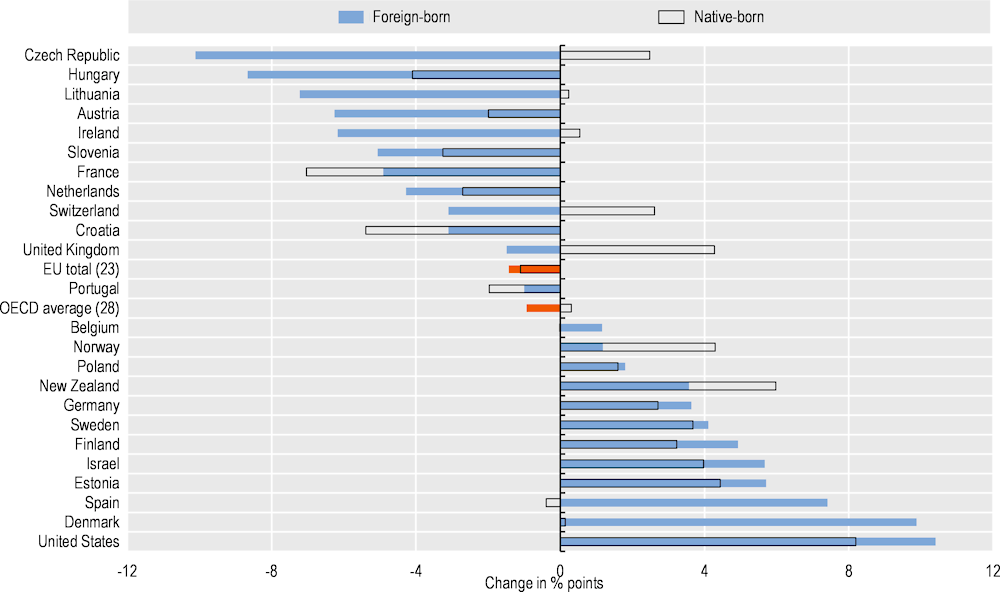

Native‑born turnout grew in slightly more than three countries in five compared with the first decade of the 2000s, but in only half among the foreign‑born. However, the rise was much more pronounced among immigrants than the native‑born in most countries, in particular Spain and Denmark. As a result, the turnout gap between native‑ and foreign‑born narrowed in more than half of countries. By contrast, native‑born turnout climbed e.g. in Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the Czech Republic, but declined among the foreign‑born, thereby widening the gap.

Higher age and education are often associated with higher voter turnout among the native‑born, but differences in native‑ and foreign‑born voter turnout remain constant in the EU, regardless of these factors. Gaps between the foreign- and native‑born persist, irrespective of level of education. There are exceptions, though. Low-educated migrants are more likely to vote than their native‑born peers e.g. in Belgium (where voting is compulsory), the United Kingdom, Estonia, Israel and the United States, while highly educated ones are less so. The apparent absence of a turnout gap between the foreign- and native‑born in France and Slovenia is attributable to the higher turnout among highly educated migrants. Like acquiring host-country citizenship (a prerequisite for voting in national elections), becoming interested in host-country politics takes time. As a result, voter participation is driven by settled immigrants – those who have lived in the country for over 10 years. EU- and OECD-wide, turnout is over 20 percentage points lower among migrants who are already host-country citizens but have less than ten years of residence. Among settled immigrants, it is still around 4 points lower than among the native‑born.

Main findings

Of immigrants with host-country nationality, 73% took part in the most recent national elections in both the OECD and the EU – compared to around 80% of the native‑born. In the Netherlands, Austria, Germany, Switzerland and the United Kingdom, voter turnout is higher among immigrant women than men, while the reverse is true among the native‑born.

Voter turnout gaps between foreign- and native‑born persist at all levels of education. However, low-educated migrants are more likely to vote than their native‑born peers e.g. in Belgium, the United Kingdom, Estonia, Israel and the United States. The same holds true of highly educated immigrants in France and Slovenia.

Figure 5.3. Self-reported participation in most recent election

Figure 5.4. How self-reported participation in most recent election has evolved

Notes and sources are to be found in the respective StatLinks.

5.3. Host-society attitudes towards immigration

Indicator context

The nature of a host society’s perception of its immigrant population is critical: positive attitudes facilitate integration.

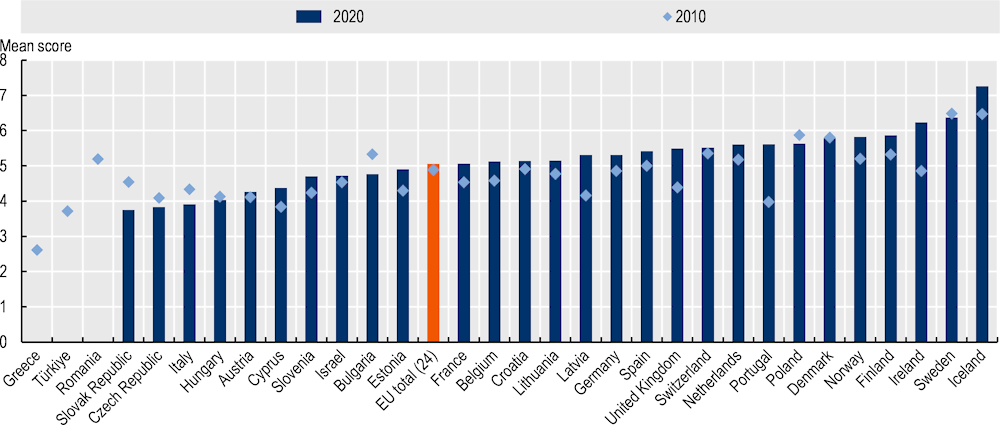

This indicator for EU countries is the average response (on a scale from 0 to 10) to the question: “Is [this country] made a worse or a better place to live by people coming to live here from other countries?”. It includes similar questions for Australia, Korea and the United States.

Half of the native‑born in the EU held no particular view in 2020 on whether “immigrants make their country a better or a worse place to live in”. A quarter had positive views, one‑quarter negative ones. Respondents in the Nordic countries and Ireland were most positive, in contrast to Italy and Central European countries (bar Poland and Slovenia). Views on migration flows were broadly equally distributed in the United States and Korea, but more polarised in the former country: respectively 38% and 28% of the native‑born aged 18 and over in 2021 agreed that the country should limit immigration to protect their way of life, while 35% and 29% thought the other way around. Similarly, 35% of the native‑born in the United States called for less immigration, and 24% for more. In Australia, 35% of the native‑born in 2021 also said there were too many immigrants, but only 16% that there were too few. Attitudes are less positive in Latin American countries, where half of respondents declare that arrival of immigrants harm them, up to 80% in Colombia.

Native‑born attitudes to immigrants became more supportive in most countries in the 2010s, as economies recovered from the 2007‑08 economic downturn. Negative perceptions did strengthen in Italy, Sweden and Central European countries, however. While it is still too early to assess the impact of the pandemic on European views of immigration as the survey was conducted in many European countries before the pandemic, it is possible in Australia which restricted migration flows (except in critical sectors). Indeed, the proportion of the native‑born who deemed the number of immigrants too high dropped by 14 percentage points between 2018 and 2021 to its lowest level since 2011.

The native‑born respond more positively to more specific questions on immigrants’ impacts on their country. They are more likely to reply that immigration enriches the host-country culture – and more so in Nordic countries and longstanding destinations. They also take a more positive view of immigration’s economic impact in most countries, although to a lesser extent. Portugal, Germany, Switzerland, Costa Rica and the Nordic countries are the most positive, where at least 40% of respondents have a positive view. Opinions are more favourable in Australia, where 83% of native‑born endorse the statement that immigrants are generally beneficial for the economy. By contrast, one‑fifth of Colombians and only one‑quarter of Koreans hold the view that immigration positively influences the economy/development.

Main findings

Half of the native‑born in the EU and Australia have no strong positive or negative view on immigration. Views are more polarised in the United States, where positive and negative views of immigration restrictions are evenly distributed and few native‑born have a neutral opinion. In Latin American countries, half of respondents have a negative opinion.

Views of the native‑born have improved in most countries over the last decade. Young people tend to have more positive perceptions than the elderly almost everywhere.

The native‑born tend to voice slightly more positive views of the impact of immigration on the host country’s culture and, to a lesser extent, on its economy.

Figure 5.5. Host-country perception of the presence of immigrants

Figure 5.6. Host-country perception of the economic impact of immigrants

Notes and sources are to be found in the respective StatLinks.

5.4. Interaction with immigrants

Indicator context

Interactions between foreign- and native‑born can ease prejudice and enhance social cohesion.

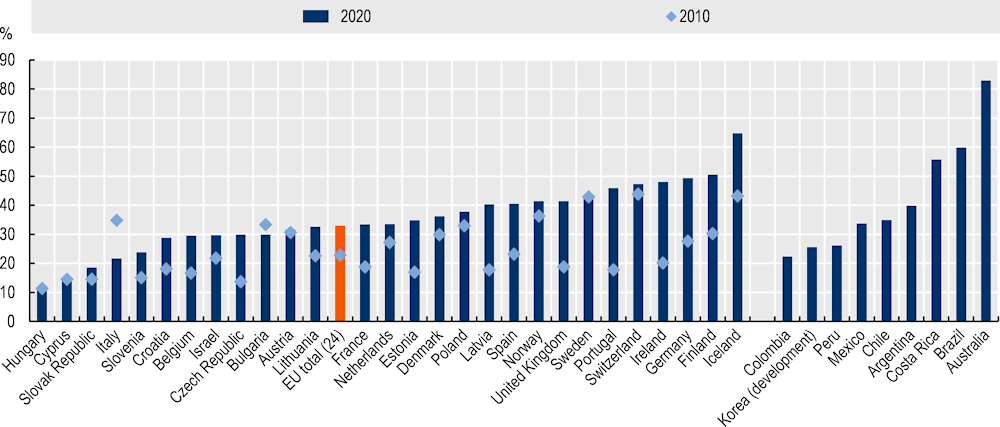

This indicator refers to the share of EU nationals who interact socially with non‑EU born at least once a week. Interaction ranges from a few minutes conversation to a joint activity.

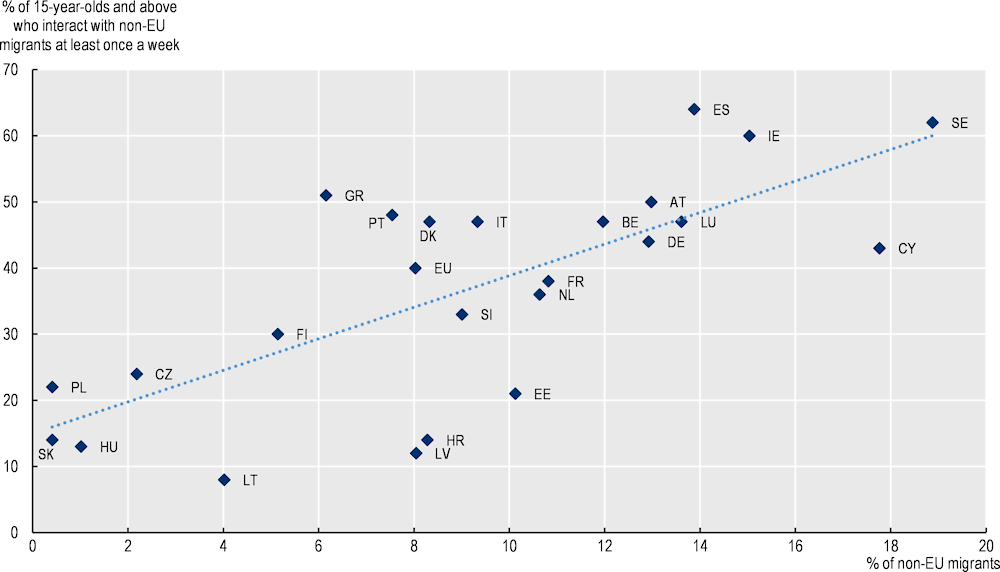

Out of 5 native‑born EU citizens, 2 stated in 2021 that they interact socially with immigrants from non‑EU countries at least once a week. Among them, half do so on a daily basis and half on a weekly basis. An additional 1 in 5 respondents interacts once a month and 1 in 10 interacts once a year. Those interactions may have been disrupted by the effect of the COVID‑19 pandemic. Because interaction is correlated with the size of the non‑EU migrant population living in the country, the native‑born have only limited interactions with non‑EU migrants in Central and Eastern European countries, where the immigrant population is rather small. By contrast, countries with large non‑EU born populations are those where the native‑ and foreign‑born interact the most, with shares of over 40% of native‑born interacting in most Nordic, Southern European and longstanding destination countries. Compared with the relative size of their non‑EU migrant populations, interaction is more widespread than expected in Southern Europe, Ireland and Denmark. Conversely, there is little stated interaction in the Baltic countries and Croatia, despite much larger populations born outside the EU.

Several sociodemographic factors shape social interactions between native‑ and foreign‑born communities. In the EU, for instance, younger individuals, men, the better-educated and the employed are more likely than the rest of the population to interact with non‑EU migrants. The share of EU citizens aged under 25 who interact weekly with non‑EU migrants is 53%, 22 percentage points higher than among EU citizens aged 55 or older. The size of the place of residence is also associated with the extent of social interaction, with almost half of respondents reporting interaction with immigrants in large cities, where they are concentrated, against less than one‑third in rural areas (where they are under-represented).

EU citizens who themselves were born in another country are more likely to interact with the non-EU foreign-born community than those born in the host country. While only 38% of the native‑born interact weekly with non‑EU migrants, 54% of the foreign‑born EU citizens do so. Moreover, in the EU, native‑born respondents with at least one foreign‑born parent or grandparent are much more likely to interact weekly with such immigrants compared to other native‑born – around 45% of those with EU parentage or grandparents from the EU, and around 55% among those with non‑EU ties. Many social interactions with non‑EU migrants go hand-in-hand with a more positive view of immigration and integration. People who interact weekly with non‑EU migrants are more likely to believe their integration is successful (see Indicator 5.8) and feel better informed about immigration and integration. EU citizens who do not interact with non‑EU migrants on a weekly basis are one‑third less likely to consider immigration an opportunity.

Main findings

Interactions with non-EU migrants are linked with the size of the non-EU born population. EU citizens state that they have more interaction with the non‑EU born than expected in Southern Europe, Ireland and Denmark, but more limited interaction in the Baltic countries and Croatia.

Young people and urban dwellers are more likely to interact with non-EU migrants.

Greater social interaction with non‑EU migrants tends to be associated with more positive views of immigration and integration.

Figure 5.7. Social interaction with immigrants in the EU

Figure 5.8. Social interaction with immigrants in the EU according to the relative size of the non-EU migrant population

Notes and sources are to be found in the respective StatLinks.

5.5. Participation in voluntary organisations

Indicator context

Participation in voluntary work allows immigrants to form social ties with the host community, improve proficiency in the host country’s language and build professional skills.

This indicator refers to the share of people aged 15 years old and over who reported membership of a voluntary organisation (e.g. sport, leisure, faith, art and culture, trades unions charity) at the time of the survey.

In some two out of three countries, foreign-born are less likely to belong to a voluntary organisation than the native‑born. Differences are most pronounced in Estonia, in most longstanding European destinations, the United States and in the Nordic countries. Gaps exceed more than 15 percentage points in Sweden, Switzerland and Germany. And excluding participation in faith-based organisations, the same pattern emerges. In Canada, Italy, Spain and the Czech Republic, by contrast, there is little or no difference between foreign- and native‑born participation in voluntary work.

Over the last decade, the foreign‑born membership of voluntary organisations has risen in most European countries. The largest rises came in Germany, Cyprus and Slovenia, where, in the latter country, the gap between foreign- and native‑born dwindled. The opposite can be observed e.g. in the Nordic countries, where, except for Sweden, the foreign‑born show a lower propensity to volunteer today than ten years ago. The steepest declines in membership among the foreign‑born occurred in Estonia, the Netherlands and Iceland – by at least 11 percentage points.

Across the OECD, immigrant volunteers are more likely to be engaged with religious organisations than the native‑born (27% versus 21%). In charities and educational and consumer groups, there were no differences in foreign- and native‑born membership rates. By contrast, with the exception of the Southern European countries and Canada, immigrants are less likely to join sports clubs and recreational groups. In the Nordic countries and the longstanding immigrant destinations in Western Europe (bar Belgium), gaps in membership rates are wider than 8 percentage points. The same holds true of the membership of trade unions and political parties, albeit to a lesser extent. The lower propensity to volunteer among immigrants might be related to linguistic, cultural and socio-economic factors. Voluntary activity is less common among the low-educated, where immigrants are over-represented. However, immigrants educated to low levels actually participate more in voluntary work EU‑wide than their native‑born peers, while the opposite is true among the highly educated. When it comes to EU‑born, they are almost always more likely to volunteer than their non‑EU born peers – 64% versus 53% EU‑wide.

Main findings

Immigrants are less likely to join voluntary organisations in two out of three countries.

Foreign‑born membership rates have risen in most countries but declined e.g. in the Nordic countries (except Sweden) and the Netherlands.

Foreign‑born membership falls particularly short when it comes to trade unions, political parties and leisure groups. Immigrants are, however, more likely to join voluntary faith-based groups.

Figure 5.9. Membership of voluntary organisations

Figure 5.10. How participation in voluntary organisations has evolved

Notes and sources are to be found in the respective StatLinks.

5.6. Perceived discrimination

Indicator context

Although the perception of discrimination may not necessarily denote actual discrimination, it is an important indicator of the sense of equal treatment and, therefore, of overall social cohesion.

For European countries, this indicator refers to the share of immigrants who consider themselves members of a group that is discriminated against on the grounds of ethnicity, nationality or race. In Australia, Korea and New Zealand, the indicator builds on personal experience. In the United States it draws on reported discrimination in the workplace only, and in Canada with respect to COVID‑19.

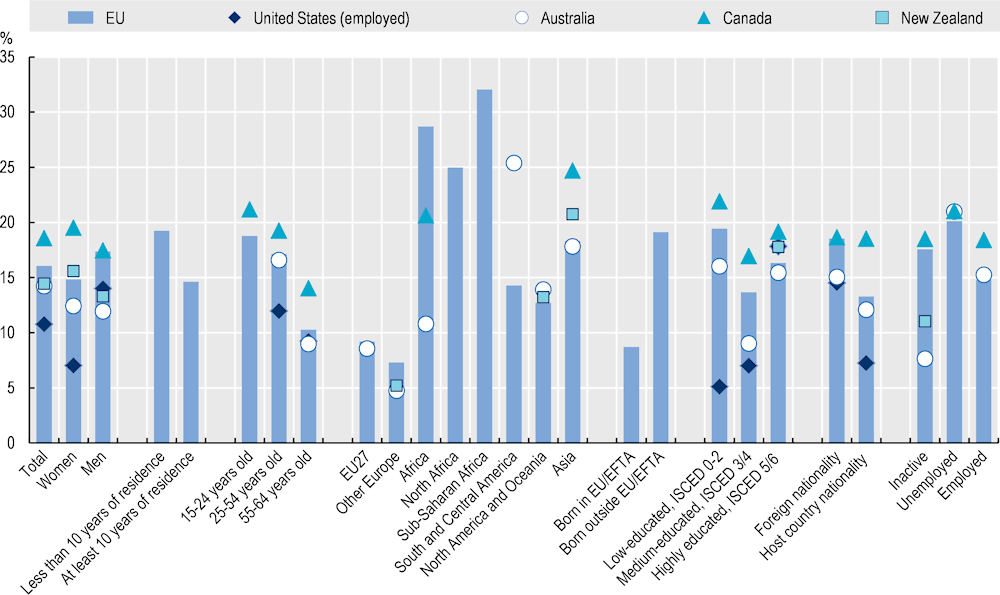

EU‑wide, 15% of immigrants consider themselves part of a group that is discriminated against, with shares exceeding 10% in more than half of all countries. Self-reported discrimination is particularly common among the foreign‑born in Italy (21%) and the longstanding destinations of many non‑EU migrants (except Germany), such as France (20%) or the Netherlands (19%). By contrast, in Central and Eastern European countries, discrimination tends to be less widespread (except Estonia). Combining these findings with those of the Eurobarometer 2021 reveals that countries with the greatest perceived discrimination are also those where EU citizens most frequently agree that discrimination is an obstacle to integration. Discrimination against foreign‑born is, however, less widely acknowledged as an issue in Austria, Estonia or the Czech Republic, while very widely recognised in Sweden. Outside Europe, shares of immigrants self-reporting personal discrimination peak in Korea at 20% and in Canada at 19% (since the onset of the pandemic). Workplace discrimination (which is not measured elsewhere) tends to be lower in the United States (11%).

Between 2010‑14 and 2016‑20, the share of migrants identifying as members of a discriminated group has increased by 2 percentage points in the EU, mainly among women. Migrants from Africa are not only the group most likely to report discrimination but are also now far more likely to self-report discrimination compared to five years ago – with a rise in discrimination of 5 percentage points. Outside Europe, there have been slight falls among immigrants in the United States and Australia, but rises in Canada and New Zealand, particularly among women.

The incidence of self-reported discrimination tends to diminish with age and as migrants settle. In Europe, non‑EU migrants are slightly more than twice as likely as their EU‑born counterparts (9% versus 19%) to identify as members of a discriminated group. Perceived discrimination is particularly acute among immigrants from North and sub-Saharan Africa in the EU and Canada, while Latin American- and Asian‑born migrants report to be worse affected in Australia. The experience of discrimination is less widespread among the foreign‑born who have host-country nationality, enjoy high levels of educational attainment, and have work. Lastly, while migrant women are less likely than their male peers to report discrimination in the EU and the United States, the reverse is true in Canada and New Zealand.

Main findings

In the EU, 15% of the foreign‑born report feeling discriminated against. Shares are highest in Italy, France, the Netherlands, Korea and Canada, and lowest in Central Europe and Ireland.

Younger and more recent migrants are more likely to perceive discrimination. The same is true among men (as opposed to women) in the EU and the United States.

Between 2010‑14 and 2016‑20, perceived discrimination increased in the EU, New Zealand and Canada, particularly among women and among immigrants from Africa. The reverse was true in Australia and the United States.

Figure 5.11. Self-reported discrimination, by duration of residence

Figure 5.12. Immigrants’ self-reported discrimination, by characteristics

Notes and sources are to be found in the respective StatLinks.

5.7. Trust in public authorities

Indicator context

Trust in public institutions by immigrants is a key indicator of social cohesion and is strongly linked to immigrants’ feeling of being an equal, accepted member of the host society.

The indicator relates to the share of individuals who report trusting the police, parliament, or the legal system (the executive, congress, and Supreme Court in the United States).

Across the EU, immigrants are more likely than their native‑born peers to state that they trust the police –61% versus 54%; parliament, albeit to a lesser extent – 30% versus 20%; and the legal system – 45% versus 33%. The picture is similar outside the European continent, where immigrants are more likely everywhere to trust in public institutions, especially when it comes to parliament (bar Israel). In two‑thirds of countries, immigrants are more likely than the native‑born to trust the police and legal system, and have greater trust in parliament in five out of six countries. The gap between native‑ and foreign-born trust in the police is particularly wide in the United States, Cyprus, and some Central- and Eastern European countries. The gap between native‑ and foreign-born trust in the legal system is starkest in Canada, New Zealand, Spain and Belgium (at least 15 percentage points). By contrast, immigrants are less likely than the native‑born to trust the police and the legal system in the Czech Republic and Baltic countries, where overall trust is low. Immigrants are also less confident in these institutions than their native‑born peers in the Nordic countries with high levels of trust.

Between 2002‑10 and 2012‑20, trust in public institutions grew in both groups across the EU, albeit slightly more among the foreign‑born. Shares of both foreign- and native‑born who trust the police increased by around 7 percentage points, while trust in parliament (3 points) and the legal system (4 points) also grew. Some notable exceptions were Cyprus and Spain, where trust in the legal system and parliament fell among immigrants and native‑born alike. Trust has also waned in the United States among both groups in all types of institutions – particularly Congress.

Immigrants may be more trustful in host-country institutions because the situation in their country of origin breed lower confidence, according to research. As this effect weakens over time, trust is lower among settled immigrants than their newly arrived peers in around 4 out of 5 countries. There is a constant gender gap when it comes to trusting in institutions: both native‑ and foreign‑born women are around 5 percentage points less likely than their male peers to trust parliament or the legal system. Lastly, while low-educated migrants are slightly less likely than their highly educated peers to trust in host-country institutions (e.g. 61% versus 65% for the police), differences between the native‑born are wider (e.g. 50% versus 61% for the police).

Main findings

Immigrants are more likely than the native‑born to trust the police and legal system in two‑thirds of countries. Across the EU, 61% of immigrants report that they trust the police and 45% the legal system, compared with respectively 54% and 33% of the native‑born. Immigrants are more trustful of host-country institutions outside Europe, too.

In the EU, trust in public authorities has grown since the early 2000s, although more strongly for the foreign‑born. This is in contrast to the United States, where trust in public institutions has declined among both groups.

Immigrant trust in public authorities tends to decline with length of residence.

Figure 5.13. Self-reported trust in the police

Figure 5.14. Self-reported trust in the legal system

Notes and sources are to be found in the respective StatLinks.

5.8. Host-society views on integration

Indicator context

The way members of host societies perceive the integration of immigrants reflects overall attitudes towards them and integration outcomes. Positive views of integration are indicative of broader social cohesion.

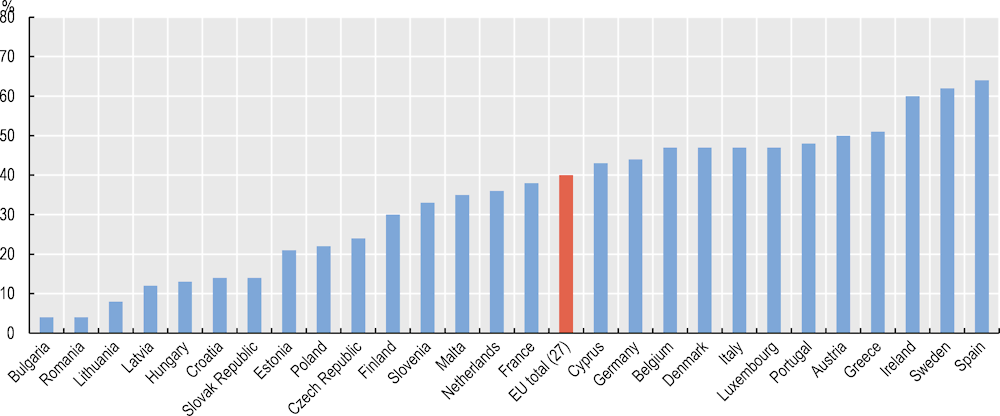

This indicator (available only for EU countries) refers to the share of EU nationals who think that the integration of non‑EU migrants is very or fairly successful, at national or local level.

In 2021, 47% of EU citizens thought that the integration of non‑EU migrants was successful in their country. Views differed widely between countries, with no patterns common to countries with broadly similar immigrant populations. For instance, only a quarter of respondents think that integration is successful in Sweden, much less than in other countries with large recent intakes of humanitarian migrants. Similarly, around one‑third of respondents voice positive views of integration in Latvia and France – again much lower than in other Baltic and longstanding immigration countries. By contrast, most respondents positively perceive integration in countries with high shares of non‑EU labour migrants, like Ireland or some Central European countries, though not in all Southern Europe – Italy and Greece voice more negative sentiments.

Views of integration are virtually always more positive at local than national level, with around 3 EU citizens in 5 saying that it is successful in their city or area. Gaps in view of integration at national and local levels are widest in most longstanding destinations (particularly France and Belgium), Sweden and Austria.

Different socio-economic groups share very similar views on the successful integration of non‑EU migrants in their country. There is little difference regarding gender, employment status and level of education EU‑wide. However, respondents under 25 years old and those reporting living in large cities believe that integration is significantly more successful than their older peers and those living in smaller cities and villages. Broadly speaking, EU citizens who feel more informed or who interact more frequently with immigrants from outside the EU view integration positively. The same is true of EU citizens with foreign-born parents or grandparents.

Views at national level of the integration of immigrants were more positive in 2021 than four years previously in two‑thirds of countries. The greatest improvements came in most Central European countries and Germany, where the share of respondents who considered the integration of non‑EU migrants was successful rose by at least 8 percentage points. By contrast, views are now significantly less positive in Croatia, Slovenia, Austria and Finland. A majority (53%) of EU citizens consider their national governments do not do enough to actively promote immigrant integration, and 69% consider that doing so is a necessary long-term investment.

Main findings

In 2021, 47% of EU citizens in the EU perceived the integration of non‑EU migrants in their country as successful. Views were most positive in Ireland and some Central European countries, and most negative in Sweden, Latvia and France.

EU citizens who feel more informed or who interact more extensively with non‑EU migrants generally view their integration more positively.

Most EU citizens (53%) consider their national governments do not do enough to actively promote immigrant integration, and 69% consider that doing so is a necessary investment.

Figure 5.15. Host-society views on the integration of non‑EU migrants in the EU

Figure 5.16. Host-society views on the integration of non‑EU migrants, by several characteristics, EU27

Notes and sources are to be found in the respective StatLinks.

5.9. Host-society perception of trends in integration outcomes

Indicator context

How the host society perceives trends in immigrants’ integration outcomes and how far from or close to the actual situation its perceptions are reflect the public’s degree of knowledge of integration issues and its opinions of migrants. The indicators considered are employment, poverty, level of education and educational attainment.

This indicator (only available for EU countries) compares perceived evolution in key integration outcomes of foreign-born from non-EU countries over the last 10 years with the actual evolution of the situation over that time. Perceived evolution is drawn from EU citizens’ responses to Eurobarometer 2021, and the actual evolution from the most recent data published in this report. Actual evolution is considered positive/negative when the evolution over the last 10 years in the indicator concerned is +/‑2 percentage points or +/‑10 PISA score points. In between, evolution is considered non-significant, therefore stable.

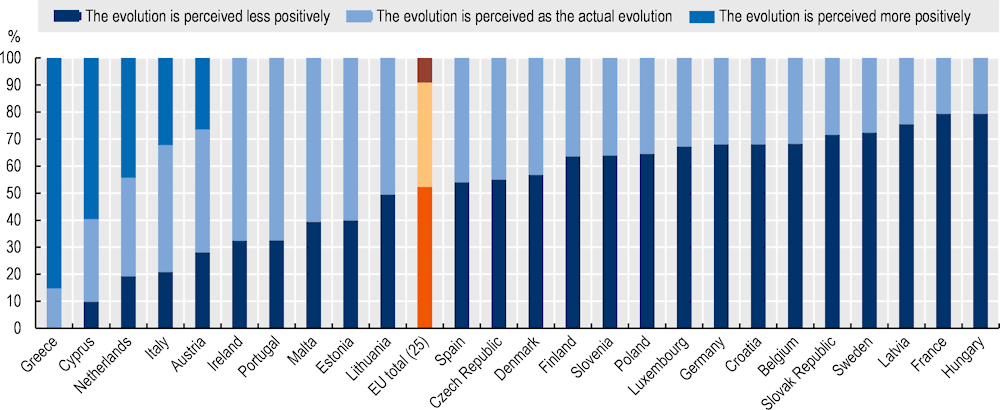

Irrespective of the indicator considered, most EU citizens have an inaccurate perception of how immigrants’ integration has evolved over the last decade. When it comes to the percentage of immigrants having jobs (approximated as the employment rate), most respondents in one‑quarter of EU countries consider that the evolution they perceive is the actual evolution, while only in Greece, Cyprus and the Netherlands they perceive the trend in migrants’ employment rates as more positively than it in fact is, and less positively in almost 3 in 5 countries. EU‑wide, only 39% of respondents believe that the evolution in their country is going in the same direction as the evolution that actually occurred, while 52% perceive the trend in employment rates less positively than in reality, and 9% more positively. The latter is often the case in Southern European countries (except Spain and Portugal), where non‑EU migrants’ employment rates have fallen, or at best remained stable. In many Central European countries and most longstanding destinations, by contrast, where employment rates have actually climbed, most respondents perceive that evolution as less positive than it actually was – three‑quarters of respondents in Hungary, France and Latvia. Countries where views of the evolution in immigrant employment are closest to reality are Ireland, Portugal, Malta and Estonia.

Considering immigrant men and women separately slightly modifies the distorted views of trends of non‑EU migrants’ employment rates. EU citizens perceive the evolution of employment rates of non‑EU men and women as similar, although men have in practice enjoyed an increase in employment in slightly more countries. EU‑wide, 48% of respondents perceive the evolution in the employment rate as less positive for non-EU men than it actually was, whereas only 42% do so for non-EU women. In Spain, most respondents think that the evolution in the employment rate of non‑EU born men was worse than it actually was, and the evolution in the rate of non‑EU born women better. In the Netherlands, where the employment rates of non‑EU born men and women have remained stable, half of respondents think that non‑EU women’s labour market situation has improved. Only one‑third of respondents share that perception for non‑EU men.

Figure 5.17. How the evolution of non‑EU migrants’ employment rates was perceived in the EU

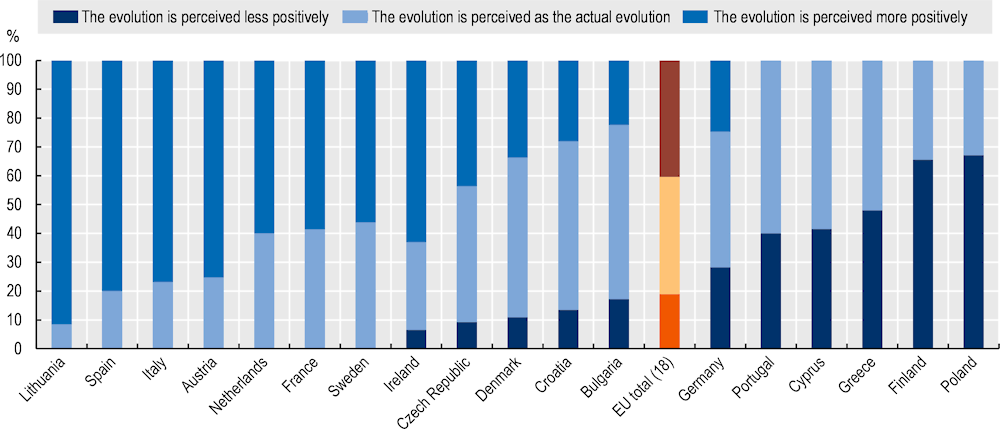

Figure 5.18. How the evolution of non‑EU migrants’ poverty rates was perceived in the EU

Notes and sources are to be found in the respective StatLinks.

When it comes to the non‑EU migrant poverty rate, EU citizens felt it had evolved more positively than it actually did. That was the perception among 40% of respondents, while 41% of EU citizens’ perceptions painted a realistic picture, and 19% thought poverty grew worse than in reality. In almost all countries where non‑EU migrant poverty rates increased over the last decade, most respondents perceived rises in poverty as lower than in reality, particularly in Lithuania, Spain and Italy. In Southern European countries, where non‑EU migrant poverty rates dropped, that drop was in line with most respondents’ perceptions. However, other countries which experienced a decline are less aware of this evolution. In Poland and Finland, for example, respondents perceived the evolution as less positive than the actual evolution.

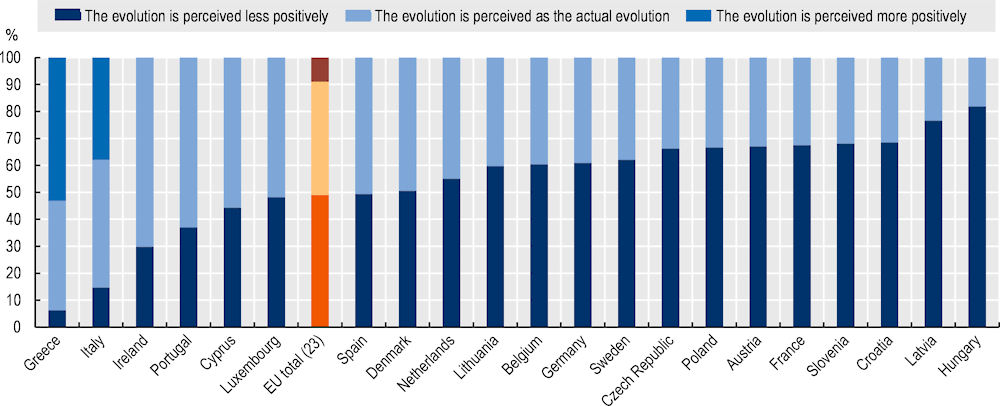

Educational attainment among the foreign‑born population, including that from non-EU countries, has improved over the last 10 years (see Indicator 3.1), with new inflows of better educated migrants. However, respondents in most countries fail to recognise the observed increase in shares of highly educated non‑EU migrants. In Central and Eastern European countries, in particular, as well as in France, one‑third of respondents at most are aware that the level of education of non‑EU migrants has risen over the last decade. And the overall share of awareness is only 42% EU‑wide. Only in one‑third of countries, especially from Southern Europe, are most perceptions closer to reality.

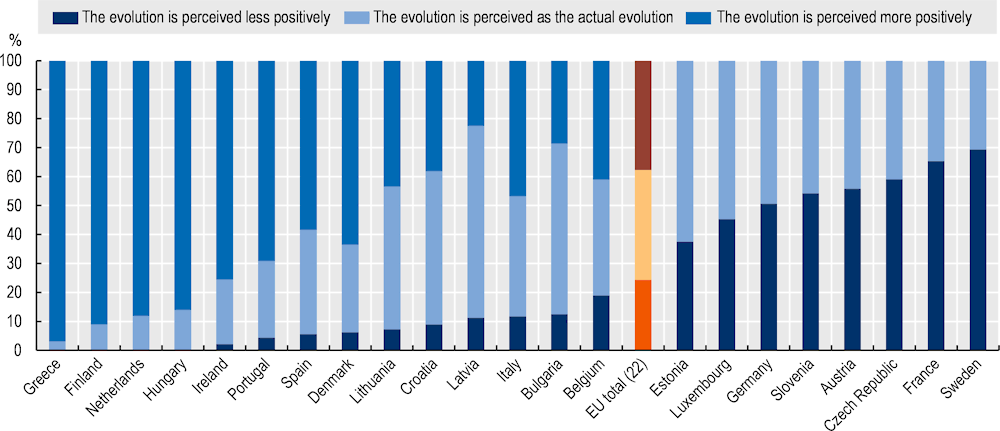

Unlike immigrant adults, the educational outcomes of the native‑born offspring of immigrants have improved over the last decade in one‑third of EU countries only and have remained relatively stable in most other countries. In the EU, 38% of respondents are aware of the trends in their country, a similar share (38%) indicate that educational outcomes have been more positive, while only 24% believe the educational outcomes of immigrants’ children have declined. Respondents in Southern European and most Nordic countries believe educational outcomes evolved more positively than they actually did. This perception is particularly true of countries where outcomes (as measured in PISA scores) have dropped the most: in Greece, Finland, the Netherlands and Hungary, around 7 respondents out of 8 think that the evolution was more positive. By contrast, in most longstanding destinations (except Belgium and the Netherlands), Sweden and the Czech Republic, where the educational outcomes of the offspring of immigrants improved significantly, most respondents perceived the evolution negatively. The greatest awareness of actual trends was found in countries which are home to a small foreign-born population such as the Baltic countries and Eastern European destinations.

Main findings

Most EU citizens have inaccurate perception of how non‑EU migrants’ integration outcomes have evolved over the last decade. Independent of the indicator considered, less than 43% of respondents’ perceptions of the evolution of integration outcomes reflect the true picture.

Most respondents in Southern Europe (except Spain and Portugal) perceive the evolution of the employment rate of non‑EU migrants as more positive than it actually was, while many Central European countries and most longstanding destinations have the opposite perception.

Although there was an increase in shares of highly educated non‑EU migrants, most countries perceived the opposite, especially in France and in Central and Eastern European countries.

Respondents in Southern European and Nordic countries (bar Sweden) perceived the evolution of educational results of the children of immigrants as more positive than it actually was. Respondents thought the opposite in most longstanding destinations, Sweden and the Czech Republic, even though the educational performance of the offspring of immigrants improved significantly.

Figure 5.19. How the evolution of non‑EU migrants’ levels of education was perceived in the EU

Figure 5.20. How the evolution of children of immigrants’ education outcomes was perceived in the EU

Notes and sources are to be found in the respective StatLinks.

5.10. Social factors perceived as necessary for successful integration

Indicator context

Understanding what the host society perceives as the drivers of a successful integration process helps policy makers to identify public concerns and possible support for certain integration policies.

This indicator, available only for EU countries, summarises the social factors which EU nationals believe important for helping and hampering the successful integration of persons born outside the EU in the host country.

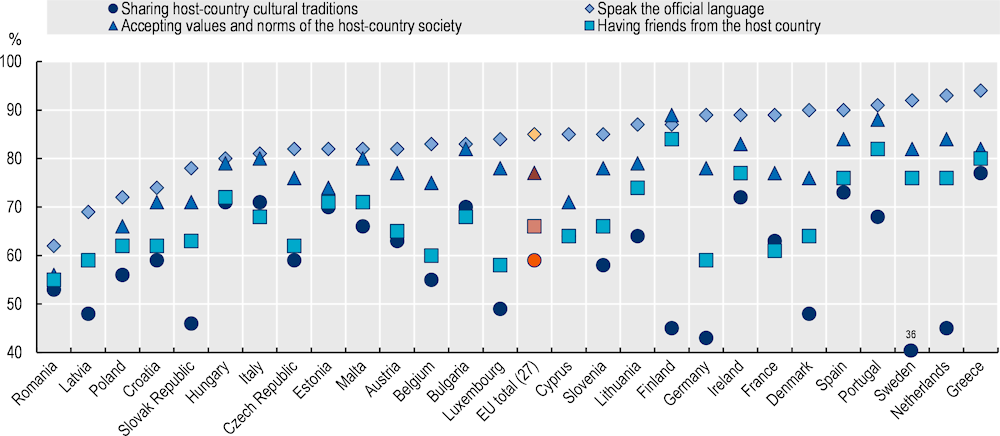

The social factors that the EU population considers important for the successful integration of non‑EU migrants are the same in virtually all EU countries. Speaking the country’s official language is most important – cited by 85% of respondents in the EU. In Finland, however, language proficiency is narrowly outperformed by acceptance of the values and norms of the host society, an important integration factor in other countries, too – for 77% of respondents EU‑wide. Indeed, it is as likely to be cited as an important integration criterion as any economic factor, such as contributing to the welfare system and being well educated and skilled enough to find a job. To a lesser extent, having friends is also important for around two‑thirds of respondents EU‑wide. Sharing the host-country’s cultural traditions is deemed less important, however, as less than 50% of respondents think so in less than one‑third of countries, most notably the Nordic countries, Germany and the Netherlands. Sharing cultural traditions is most important in new immigrant destinations, such as Southern European countries, Hungary and Ireland.

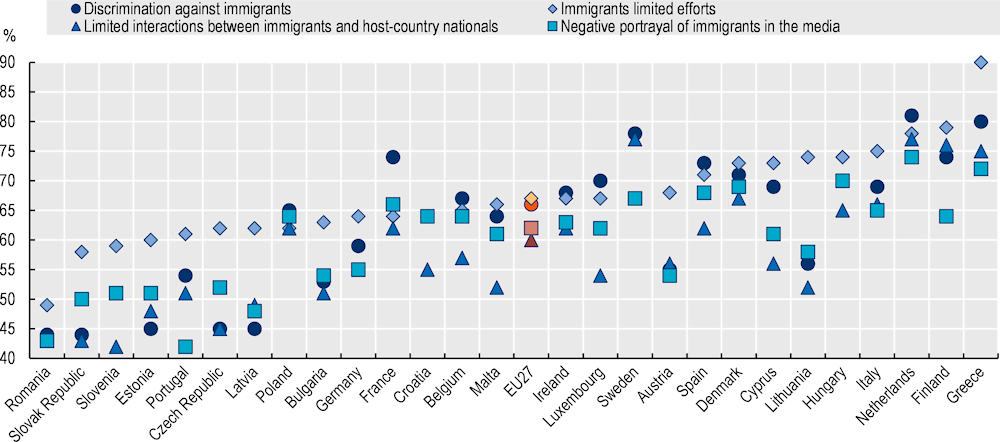

In around half of EU countries, at least two‑thirds of respondents think that inadequate efforts of immigrants themselves are one of the biggest obstacles to their integration in the host-country society. This idea is particularly widespread in Southern Europe (especially in Greece), Finland and the Netherlands. However, in countries with longer histories of immigration (e.g. France, Sweden and the Netherlands), discrimination against immigrants is deemed an even bigger barrier to integration. EU-wide, around two‑thirds of respondents consider discrimination, inadequate efforts to fit in, and high concentrations of immigrants in some areas as major obstacles for integration. However, none of these problems are perceived as important as finding a job – the chief obstacle to integration according to EU citizens. Although at least 3 respondents in 5 view lack of interaction between immigrants and host-country nationals and negative portrayals of immigrants in the media as obstacles to integration, these figures are still consistently lower than those for other obstacles mentioned before.

Main findings

Overall, speaking the host country’s official language is considered the most important social factor for the integration of non‑EU migrants, followed, at equal shares, by the acceptance of host-country values and norms, contributing to the welfare system and being educated and skilled enough.

EU‑wide, the chief obstacle to integration according to EU citizens is finding a job.

EU‑wide, two‑thirds of respondents think that the limited efforts of immigrants themselves to fit in and the discrimination against them are major social obstacles to their integration in the host society.

Figure 5.21. Social factors for successful integration of non‑EU migrants in the EU

Figure 5.22. Social obstacles to successful integration of non‑EU migrants in the EU

Notes and sources are to be found in the respective StatLinks.