This chapter lays the foundation for this publication by providing an analytical framework for assessing integration outcomes. Since cross-country differences in such outcomes hinge upon the composition of their foreign-born populations, the chapter presents a classification of EU and OECD countries based on the size and category of entry of the migrant population as well as their experience with immigration. Exploring these country groupings further, it identifies common integration challenges as well as differences between countries in the same peer group. The chapter then charts progress in integration outcomes along key dimensions.

Indicators of Immigrant Integration 2023

1. Indicators of immigrant integration: Overview and challenges

Abstract

In Brief

International comparisons in integration outcomes can provide important new insights, but require to take due account of the migrant composition

Immigrant populations are growing across EU and OECD countries. Together with their descendants, they account for an increasing share of the total population of the host countries. In the EU, nearly one‑quarter of the population aged 15 years and above have at least one foreign-born grandparent.

International comparisons provide policy makers with benchmarks so that they can compare results in their own country with those of other countries. They also highlight common integration challenges and can reveal aspects of integration that are not visible in national data.

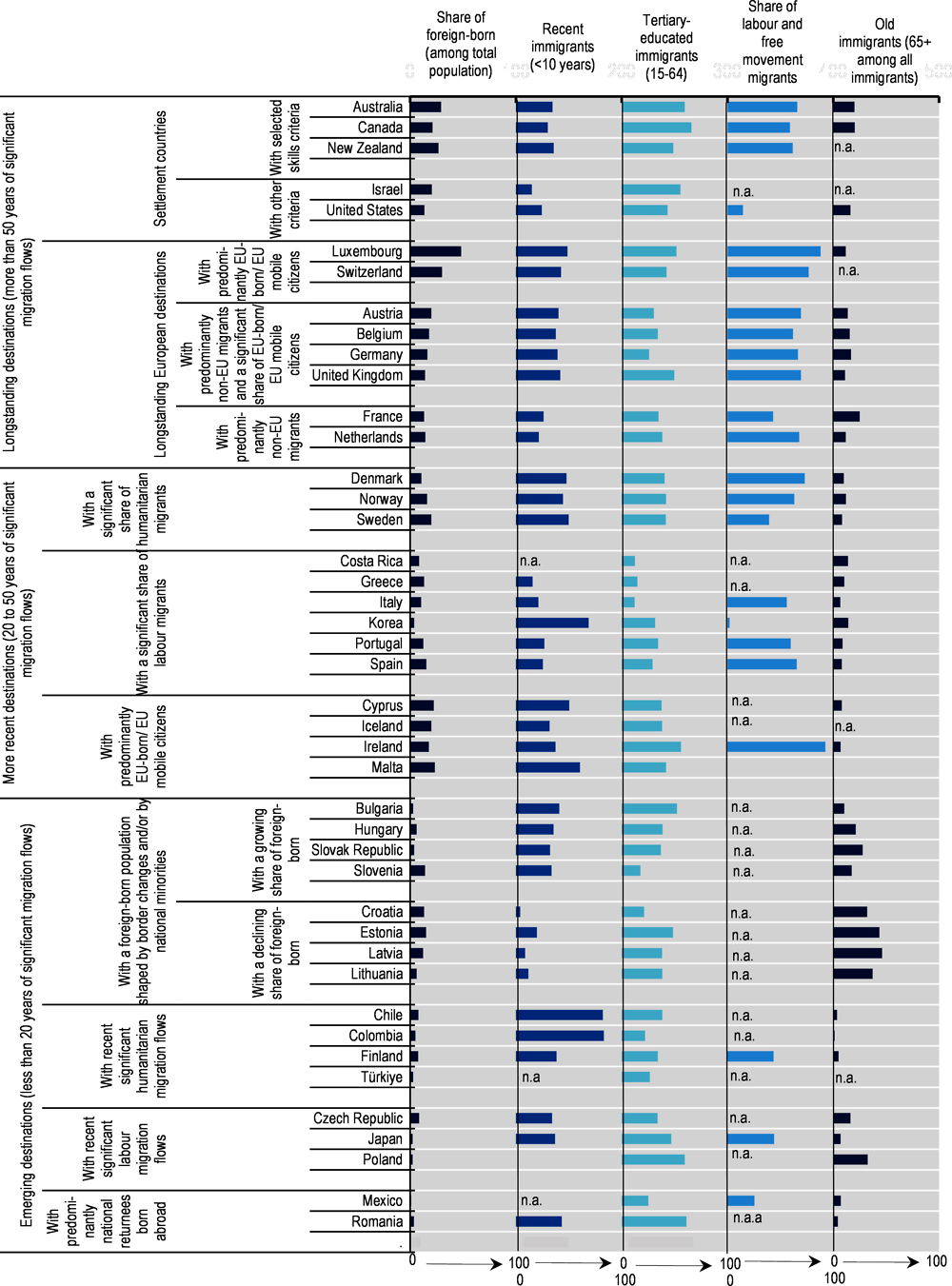

As differences in integration outcomes between countries depends largely on the composition of the foreign-born population, EU and OECD countries can be classified into 13 peer groups based on the size and category of entry of the migrant population as well as their experience with immigration.

There has been progress in the integration of immigrants on several fronts, but living conditions remain a challenge

In most areas, immigrants and their children tend to have worse economic and social outcomes than the native‑born and their respective children, but gaps tend to narrow across generations and the longer immigrants stay in the country. In particular, the integration of humanitarian and family migrants, who generally arrive with weak attachments to the labour market, takes time.

Over the past decade, the labour market integration of immigrants has improved as well as the educational outcomes of children of immigrants. Despite this progress, the living conditions of immigrants are not always more favourable than they were a decade ago.

Between 2011 and 2021, the employment rates of recent arrivals have risen in over two-thirds of countries. The better labour market performance of recent migrants is partly attributable to their higher educational attainment compared with previous cohorts: nearly half were educated to tertiary level in 2020 in the OECD, against less than one-third 10 years earlier.

1.1. The importance of accurate data on the integration of immigrants and their children for an informed policy debate

The integration of immigrants and their children continues to be high on the policy agenda across EU and OECD countries. Partly as a response to the surge in inflows during the recent refugee crises of 2015/16 and 2022, many countries have updated and stepped up their integration programmes in recent years. At the same time, the recent widespread labour shortages sparked efforts to draw in additional foreign workers and further stimulated the competition for global talent. While much of the policy attention is focused on the integration of new arrivals, in many countries, they account for only a small share of the overall foreign-born population, which faces itself many integration challenges. Indeed, looking at different indicators of integration, immigrants who have resided in the country for many years as well as their children continue to lag behind the native‑born and their respective children in most OECD and EU countries.

Integration of immigrants and their children helps to build inclusive and cohesive societies. It enables migrants to fully participate in society and fosters acceptance for further migration among host societies. Indeed, successful integration is a two‑way process, as enshrined in the EU Action Plan on Integration and Inclusion 2021‑27. This publication defines integration as the ability of immigrants to achieve the same social and economic outcomes as the native‑born, while taking into account their characteristics.

It is crucial to provide policy makers and the public with solid evidence, properly assess integration outcomes and address the obstacles that stand in the way of successful integration and to tackle disinformation. Although integration indicators strongly depend on the composition of the immigrant population and are therefore generally not in themselves a good indication of the effect of integration policies, they enable policy makers to identify challenges, set clear goals and evaluate progress. This chapter discusses the benefits of developing monitoring tools of integration at the international level. It then presents a classification of OECD and EU countries with respect to the size and category of entry of the migrant population as well as their experience with immigration. Lastly, it summarises in a comparative overview some core indicators as well as their evolution over the last decade. As the latest data available at the time of writing is from 2021, the impact of historic outflow of people from Ukraine is not yet captured in the integration indicators in this publication.

1.1.1. What is the target population?

This report defines immigrants as the foreign-born population (see also Box 1.1 on the definition of EU-born). Indeed, while citizenship can change over time, the place of birth cannot. In addition, conditions for obtaining host-country citizenship vary widely, hampering international comparisons. In countries that are more liberal in this respect – such as the countries characterised by migrant settlement, as well as Japan, Korea, Mexico and Türkiye – most foreign nationals may naturalise after five years of residence. Some European countries, such as Sweden, also have relatively favourable requirements for some groups. By contrast, many native‑born with foreign-born parents are not citizens of their country of birth in several Central and Eastern European countries and in the German-speaking countries.

Box 1.1. EU-born and EU mobile citizens

This publication uses the term “EU-born” when referring to a person born in the EU/EFTA area who settles in another EU/EFTA country. This definition is based on the country of birth and differs from the term “EU mobile citizens”, which is based on citizenship and refers to EU citizens residing in another EU member country. In practice, there is a significant overlap between both groups. Out of the about 15 million EU-born and the 12 million EU mobile citizens in the EU, 9.5 million belong to both groups.

However, more than one‑third of the individuals born in another EU country (that is, more than 5 million persons) have host-country citizenship and are consequently EU-born but not EU mobile citizens. Furthermore, since EU citizenship is not unconditionally conferred to a person born in the EU, there is also a small group of around 300 000 individuals who were born in another EU member country but are third-country nationals.

At the same time, there are nearly 1 million people born outside the EU who have citizenship of an EU member country (either by birth or due to naturalisation) but currently reside in another EU member country. As a consequence, these individuals are EU mobile citizens but not EU-born. Likewise, nearly 2 million people with the nationality of another EU member state were born in their current country of residence and are therefore EU mobile citizens but not EU-born.

When it comes to defining children of immigrants, most countries consider them as native‑born with at least one foreign-born parent, although occasionally this also refers to native‑born with foreign nationality. Most countries have little information on native‑born with foreign-born parents because information on parental origin is rarely collected. This report avoids the widely used term “second generation migrant” as this term suggests that the immigrant status is perpetuated across generations. It is also factually wrong since the persons concerned are not immigrants but native‑born. Similarly, it avoids the term “people with a migrant background” – a term that is often used to encompass both immigrants and their native‑born descendants. Indeed, the issues involved in the integration of persons born abroad – especially for those who migrated as adults – and of children of immigrants raised and educated in the host country differ greatly.

There are many reasons why the outcomes of immigrants – particularly those who arrived as adults – tend to differ from those of the native‑born population. They have been raised and educated in an environment and often in a language that may be different from that of their host country. Although some of these issues may affect their full integration, they generally become less of a hindrance the longer migrants reside in the host country. The situation of people who are foreign-born but arrived as children when they were still of mandatory schooling age is different from those who came as adults. Indeed, for the latter, certain key characteristics such as educational attainment are barely influenced by integration policy (as education has been acquired abroad), and thus should not be considered as indicators of integration. In contrast, educational attainment is a key indicator for those who arrived as children or are native‑born with foreign-born parents.

Finally, issues are also very different when it comes to the native‑born with foreign-born parents.1 As they have been raised and educated in the host country, they should not be facing the same obstacles as their foreign-born parents. In many respects, the outcomes of the native‑born offspring with foreign-born parents are thus a better measurement for integration than the outcomes of the foreign-born.

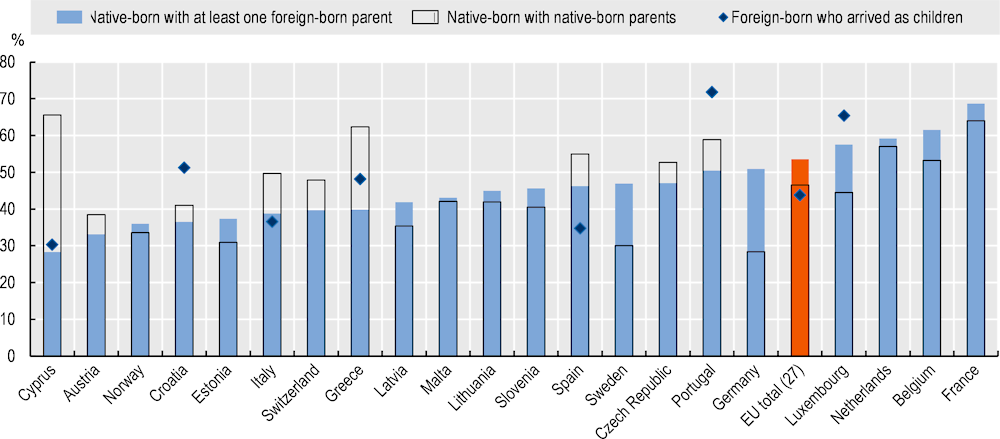

Figure 1.1 provides an overview of the populations that are either foreign-born themselves or have one or two foreign-born parents. The former group is broken down into those who arrived as adults and those who arrived as children during mandatory school age (i.e. before the age of 15). Based on household survey data, around one in seven people living in the EU (see Box 1.2) and one in nine in the OECD is foreign-born, 54 million and 142 million, respectively. Among these, around one‑quarter arrived before the age of 15 in the OECD, a share that is slightly higher in the EU (29%). Native‑born with at least one foreign-born parent account for roughly 7% of the total population in the EU and the OECD – around 28 million and 91 million, respectively. While in the United States, United Kingdom and Israel, the majority of the native‑born with foreign-born parents have two immigrant parents, in the EU, most are of mixed parentage, i.e. one native‑born and one foreign-born parent. Taken together, around one in five are either foreign-born themselves or have at least one foreign-born parent in the EU, a share that is slightly lower in the OECD.

Figure 1.1. Immigrants and native‑born with foreign-born parents

Notes: In Japan, Korea, Mexico and Türkiye, the estimates for immigrant offspring are based on the share observed in PISA 2003 (among the 15‑34 native‑born) and PISA 2018 (among the less than 15 years old native‑born). In Colombia, Costa Rica and Chile, the estimates for immigrant offspring are based on the share observed in PISA 2009 (among the 15‑34 native‑born) and PISA 2018 (among the less than 15 years old native‑born).

Further notes and sources are to be found in the respective StatLink.

Immigrants account for around half of the population in Luxembourg, nearly two‑fifths in Switzerland and one‑third in Australia and New Zealand. At the other end of the spectrum, less than one-tenth of the population is foreign-born in most Central and Eastern European countries, the Asian OECD countries and the Latin American OECD countries. Immigrants outnumber native‑born with at least one foreign-born parent in all countries except for some Central and Eastern European countries, as well as Mexico, France and Israel. Overall, half of the population in Australia, Switzerland and Israel and over 70% in Luxembourg are either foreign-born or have at least one foreign-born parent. In other longstanding European destinations, that share ranges between one‑ and two‑fifths. By contrast, in the Latin American countries (except Costa Rica), the Asian countries as well as most Central and Eastern European countries, less than one in ten of the population belong to this group.

Box 1.2. Methodological note on the treatment of the United Kingdom in the EU context

Due to the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the EU, the country is no longer included in EU averages and EU totals in this edition. Furthermore, this publication considers immigrants born in the United Kingdom as non-EU born. In a similar vein, UK citizens residing in EU member states are considered third-country nationals (TCNs). However, as they were EU mobile citizens before 2020 and most surveys do not provide detailed information on the country of birth, it is not possible to include them among TCNs in earlier years. While this creates a bias in some time comparisons (see Chapter 8), the impact is limited as UK citizens residing abroad only account for 3.5% of all TCNs in the EU. The proportion is much higher in Ireland, though, which was therefore excluded from all time comparisons in Chapter 8.

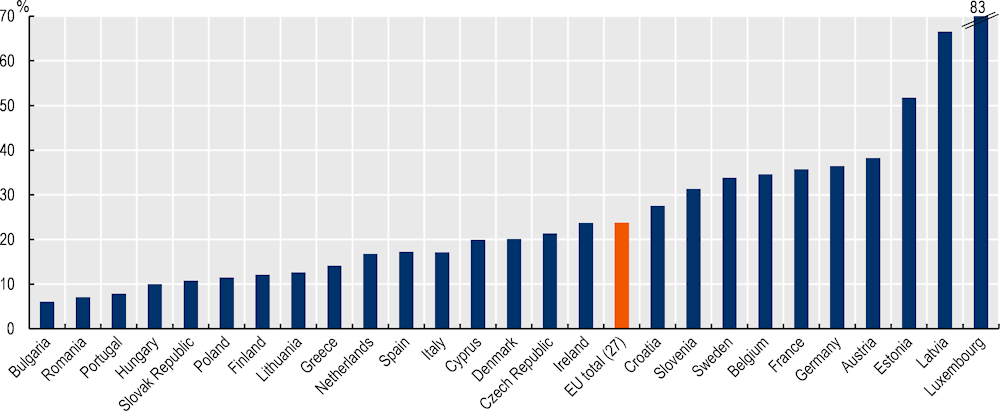

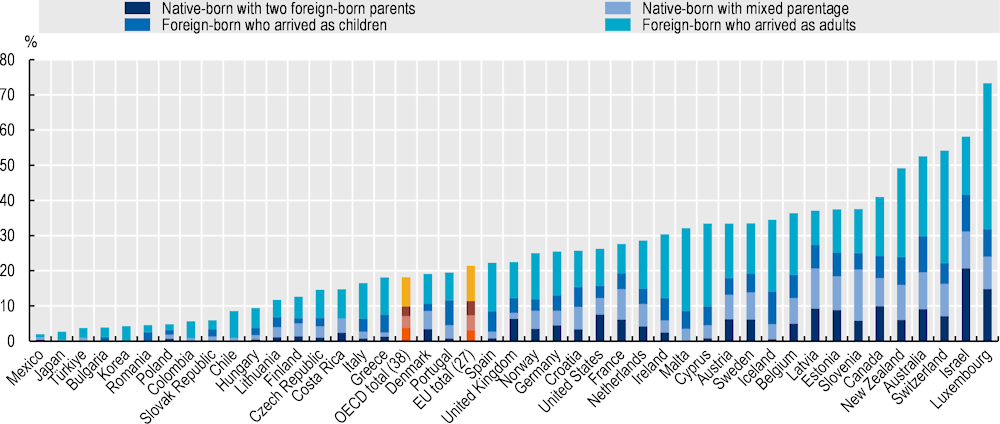

Figure 1.2. Immigrants and native‑born with at least one foreign-born grandparent

While many household surveys collect data on immigrants and their descendants, little is known about the grandchildren of immigrants.2 For the first time, a special Eurobarometer 519, launched by the European Commission in 2021, allows to estimate their share among EU citizens. Assuming that all TCNs have at least one foreign-born grandparent and adding this share to that of EU citizens with at least one foreign-born grandparent, one finds that in the EU, nearly one‑quarter of the population aged 15 years and above have at least one foreign-born grandparent (Figure 1.2). Around half of them were born outside of the EU. In Luxembourg and Latvia, around four‑fifths and two‑thirds of the population in this age range have at least one foreign-born grandparent, respectively. Shares are also large in longstanding European destinations (except for the Netherlands), where they account for over one‑third.

1.1.2. How is integration measured?

This publication assesses integration outcomes and their changes over time in relative terms, that is by comparing outcomes of immigrants with those of the native‑born (Chapters 2 to 6), the outcomes of the native‑born children with foreign-born parents with those of their peers with native‑born parents (Chapter 7) as well as TCNs with nationals of the country of residence in Europe (Chapter 8). These indicators are easy to understand and can help to better identify integration challenges. However, they are influenced by the composition of the immigrant population as well as a broad set of circumstances and policies and do not necessarily reflect successes or failures of policy. Indeed, integration policy is just one factor among many and its weight may depend on the country. To properly assess the impact of integration policy, other measures are needed (see Box 1.3).

Box 1.3. Assessing integration policy through monitoring and analysis

Target indicators are a common way to measure the success of a specific integration policy. They provide readily available policy targets or benchmarks for a specific group in a pre‑defined time horizon. An example would be the aim of lowering the unemployment rate among migrants by 2 percentage points by 2025 in a country in which joblessness is more prevalent among migrants.

Satisfaction surveys among a pre‑defined group of beneficiaries are a common way to assess the success of a specific policy designed to reach such targets. While these are relatively easy to administer, they are not an objective measure of effectiveness. What is more, opinions tend to be influenced by many factors not related to the programme objectives.

A more objective way of measuring and monitoring the effect of a policy are ex-ante and ex-post comparisons of outcomes. However, labour market outcomes, for example, may be influenced by overall economic conditions as well as other policy measures (e.g. other labour market policy interventions). Comparing the change in outcomes over time with the change among a comparison group with the same characteristics not affected by the policy can partly control for this. Yet, this method is not free of bias either. In particular, selection effects in programme participation as well as selective dropouts can bias results. More complex study designs, such as randomised control trials, different pre‑ versus post-programme cut-off times as well as regional pilots, can help to minimise these biases and other confounding factors.

The two most common ways of measuring the outcomes of a target group against those of a reference group are: i) as differences in outcomes (mainly expressed in percentage points, since most indicators are shares or rates) and ii) as a ratio between the two outcomes.

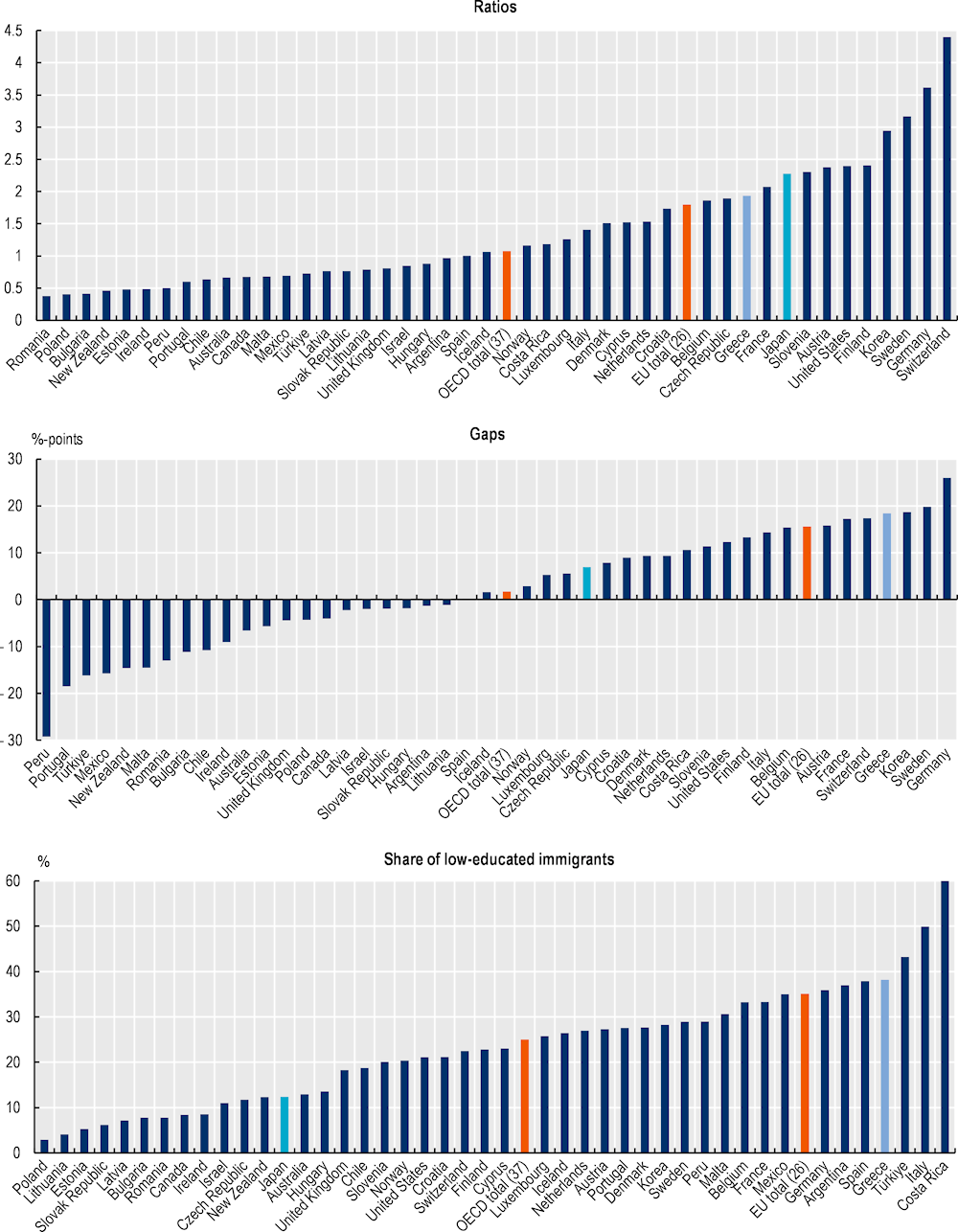

Figure 1.3 depicts the share of low-educated immigrants and native‑born. It shows how different measurement methods can yield different country rankings. In this example, the ratio between the share of low-educated immigrants and that of the native‑born is comparatively large in Japan and Greece, with immigrants being around twice as likely to be low-educated as the native‑born. When it comes to the difference in shares, the ranking of Greece gets even worse, while Japan finds itself in the middle of the distribution. Although both measurements assess differences in the share of low-educated immigrants and native‑born, ratios disregard magnitude. In fact, whereas the share of low-educated immigrants in Greece is one of the highest across the OECD, Japan is among the countries with the lowest share. This report consequently presents indicators both as absolute values and discusses differences in percentage points, but rarely as ratios.

Figure 1.3. Comparison of the share of low-educated foreign-and native‑born

1.2. The added value of international comparison

International comparisons bring much added value to indicators at the national level. Specifically, they:

a) Provide benchmarks for performance

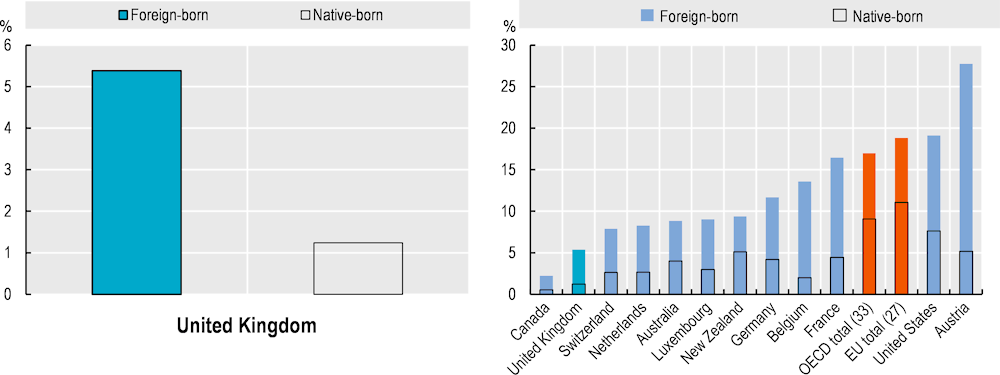

International comparisons allow countries to compare their outcomes to others. They can provide benchmarks for national performance and help interpret the magnitude of differences. For example, as shown in Figure 1.4, looking at the national level alone is not sufficient to determine whether a 4-percentage point gap in overcrowding rates (see Indicator 4.5 for a detailed definition) between immigrants and the native‑born in the United Kingdom is wide or not. However, a comparison at the international level helps to put things into perspective. It shows that the gap in the United Kingdom is narrower than in virtually all other longstanding destinations.

Figure 1.4. Overcrowding rates at the national and international level in longstanding destinations

b) Identify common integration challenges

International comparisons also highlight common challenges across countries that are related to the nature of the migration process rather than the host-country specific context. For example, compared with the native‑born, immigrants are more exposed to poverty virtually everywhere (Figure 1.5). Socio‑economic backgrounds of foreign-born populations vary widely between countries and can only partly account for discrepancies in poverty rates between both groups. Specific labour market obstacles migrants face, such as linguistic barriers and a devaluation of foreign credentials, as well as limited access to social benefits and potentially discrimination can also contribute to higher poverty rates among immigrants.

Figure 1.5. Relative poverty rates

c) Identify issues that are not visible in national data

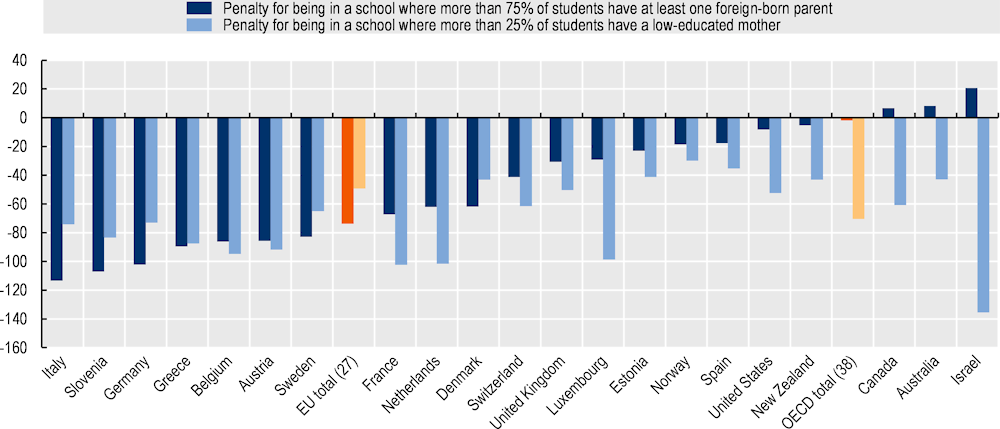

International comparisons can also help identify issues that are not visible in national data, notably when there are strong correlations between immigrant presence and other factors of disadvantage. Especially in Europe, it is commonly claimed, for example, that concentrations of immediate descendants of immigrants in the same schools risk impairing the overall educational performance of those schools. Results based on data from the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) show that in Europe, where immigrant parents are strongly overrepresented among the low-educated, students’ educational outcomes tend to be lower when they find themselves in schools with high shares of children of immigrants (Figure 1.6). However, in some OECD countries such as Australia, Canada and Israel, where immigrants are overrepresented among the highly educated, children perform better when they find themselves in schools with many children of immigrants. What emerges in contrast is that, in all countries, children’s academic performance is systematically lower in schools with high proportions of children with a low-educated mother. OECD-wide, they lag almost two years behind their peers in schools with few of such students. This can be attributable chiefly to the strong impact mothers’ education has on the academic achievements of her children. In this case, international comparisons help target the real problem related to low educational performance: not the high concentration of children of immigrants as such, but the concentration of children with low-educated mothers.

Figure 1.6. Academic performance by concentration of pupils with at least one foreign-born parent and a low-educated mother

1.3. Classifying immigrant destination countries

To interpret integration outcomes, differences in the composition of the foreign-born populations between countries must be considered. In particular, the reason for migration tends to have a strong bearing on outcomes. Humanitarian migrants, for example, face specific hurdles when entering the labour market. Due to the forced nature of their migration, they generally have had no time to prepare for their stay, suffer from psychological stress and have, if any, only a weak attachment to the host country. By contrast, labour migrants are often already selected based on their skills and/or their job in the host country and fare much better in the labour market, especially initially (see Figure 1.7 and also Figure 1.11 below).

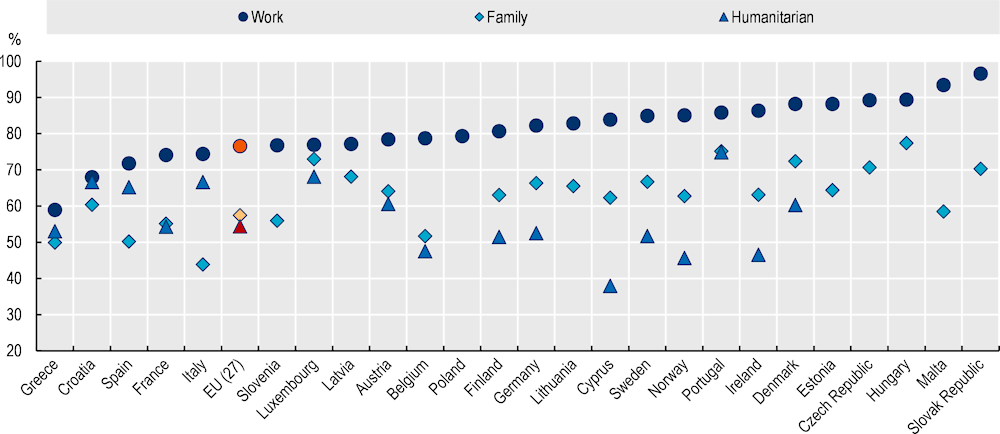

Yet, information on the reason for migration has been barely collected in household surveys, until recently. From 2021 onwards, the EU-LFS includes a question on the reason for migration biennially, which allows to present integration outcomes for different migrant groups in the EU. Outside of the EU, only few countries collect data on immigrants’ legal grounds of stay (e.g. Korea) or are able to link household surveys with their residence permit databases (e.g. Canada), which might differ from the self-reported reason for migration.

As shown in Figure 1.7, in virtually every European country, employment rates are highest for labour migrants, while humanitarian migrants tend to be the least likely to be employed. Migrants who arrive to join family members only slightly outperform humanitarian migrants across the EU, despite an allegedly stronger attachment to the host country.

These and other contextual information are crucial to the proper interpretation of immigrants’ outcomes and observed differences with native‑born populations. OECD countries vary widely in the size and composition of their immigrant populations depending on, inter alia, geographical, historical, linguistic, and policy factors. For example, while humanitarian migrants and their families make up a large proportion of the migrant population in Sweden, this share is much lower in countries such as Australia, Canada, or the United Kingdom.

Figure 1.7. Employment rates of the foreign-born by reason for migration in the EU

Recently, the historic outflow of people from Ukraine has had a significant effect on the composition of the migrant population in several countries (see Box 1.4). Notably the Central and Eastern European countries, which were predominantly receiving labour migrants in the past, saw a strong rise in the number of humanitarian migrants. As the latest data available at the time of writing is from 2021, the impact of these intakes is not yet captured in the integration indicators in this publication.

Box 1.4. Initial evidence on the integration of refugees from Ukraine

Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, which began on 24 February 2022, has triggered a massive displacement towards OECD countries. As of April 2023, more than 4.7 million Ukrainians had registered for temporary protection in the EU alone. About a million more have moved on, or are foreseen to do so to OECD non-EU countries, notably Canada, the United Kingdom, the United States, Türkiye, and Israel. Despite the uncertainty surrounding their length of stay, many refugees have reached their final destination and are starting to integrate into host societies.

OECD countries responded swiftly to the crisis, granting immigration concessions, and extending different types of support and assistance to the new arrivals. These have included financial assistance and emergency shelter as well as access to education and healthcare.

In most host countries, refugees from Ukraine have also been granted immediate and full labour market access and they benefit from labour market integration support measures, generally provided by Public Employment Services. Furthermore, tight labour markets, pre‑existing networks of Ukrainian immigrants and the refugees’ relatively high educational attainment favour their labour market integration. Considering these factors, refugees from Ukraine have been quicker to find employment than other refugee groups in many host countries. Nine months after the beginning of Russia’s war of aggression, over 40% were already employed in the Netherlands, Lithuania, Estonia, and the United Kingdom. Elsewhere, the share was lower, but is nevertheless increasing.

Despite their relatively swift entry into the labour market, early evidence suggests that this has often come at the cost of finding jobs at an appropriate skill level. In Spain, for example, where nearly two‑thirds of adult refugees are highly educated, only around one in seven is employed in a highly skilled profession. Highly skilled jobs often have substantial entry barriers, requiring potentially lengthy recognition procedures and country-specific qualifications, as well as language skills. Only few Ukrainian refugees report speaking the language of their host country, at least in non-English speaking countries, and many perceive the lack of language skills as a major obstacle in their job search. As a large share of the refugees from Ukraine are mothers with young children, the availability of childcare is also crucial for supporting employment take‑up at skills-appropriate levels.

Besides supporting the refugees’ entry into the labour market, host countries have also made substantial efforts to scale up their classroom and teaching capacities to accommodate for Ukrainian children. As children account for one‑third of all refugee inflows, this has been one of the priorities on the integration policy agenda in most host countries. The number of children attending host-country schools increased substantially at the beginning of the 2022‑23 school year, yet available data suggests differences between countries. In November 2022, more than two‑thirds of minors were enrolled in Ireland and the Netherlands, but the enrolment levels were only around one-third in Poland. Often this is because Ukrainian students continue to follow the Ukrainian curriculum remotely. However, while distance learning helped to ensure educational continuity for children in the early months of displacement, it can have a more negative impact on their integration longer term.

Source: OECD (2023), “What we know about the skills and early labour market outcomes of refugees from Ukraine”, https://doi.org/10.1787/c7e694aa-en.

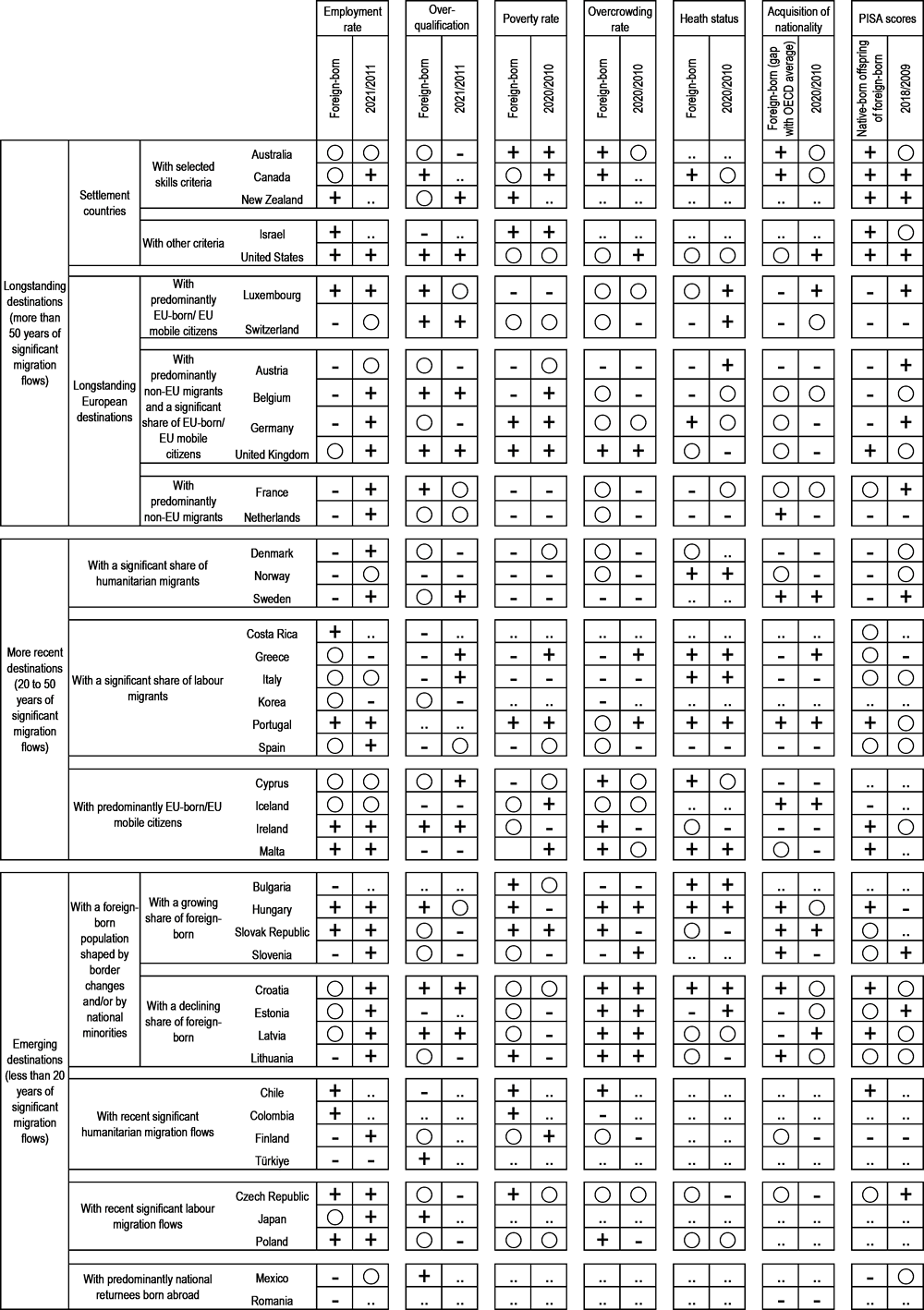

Based on the size and category of entry (labour, family, humanitarian, free mobility) of the migrant population as well as the experience with immigration – all of which shape integration outcomes -, OECD and EU destinations are classified into 13 peer groups with similar structural compositions of their foreign-born populations (Figure 1.8). These peer groups tend to face similar integration challenges, rendering international comparisons between them particularly valuable. Others show rather diverse outcomes as factors not considered in the grouping, such as the size and strength of the economy, also influence integration outcomes. As any classification requires some degree of simplification, it is impossible to accommodate all drivers of complex integration processes. Figure 1.9 shows the outcomes of key indicators across peer groups, and their evolution over time, in a synthetic way.

Figure 1.8. Classification of OECD and EU countries as immigrant destinations according to the characteristics of the foreign-born population, 2021

Group 1.1: Settlement countries with selected skills criteria (Australia, Canada, New Zealand)

These countries are characterised by migrant settlement and immigration is considered part of their national heritage. On average, around one‑quarter of the population is composed of immigrants, in addition to around one-sixth who have at least one foreign-born parent. Immigration policies in these countries mainly focus on attracting labour migrants who meet the skilled labour market needs of their economies. As a result, labour migrants and their accompanying family members constitute the bulk of their foreign-born populations. Furthermore, due to longstanding selective immigration, the average share of tertiary-educated migrants exceeds not only that of the native‑born population but also that of the foreign-born populations in virtually all other countries. It has grown considerably in Australia and Canada over the last decade and amounts to 60% and 66%, respectively.

Immigrants generally show favourable outcomes in settlement countries (see Figure 1.9). As they are mostly highly educated labour migrants and their families, they fare well in the labour market, are in good health and are less likely to be affected by poverty or live in overcrowded dwellings than immigrants in most other countries. Although they have generally not fully caught up with their native‑born peers (with certain exceptions), gaps tend to be narrower than in the OECD overall (see Box 1.5). In addition, more than four‑fifths of migrants with ten years of residence or more have obtained host-country citizenship in these countries, a much larger share than in most other OECD countries, where the acquisition of citizenship is more difficult. The high educational attainment of immigrants also seems to benefit their children. Unlike in most other countries, the native‑born with foreign-born parents in this country group outperform their counterparts with native‑born parents in school and in the labour market.

Group 1.2: Settlement countries with other criteria (Israel, the United States)

As in the former peer group, settlement has been a constituent element of nation-building in these countries. Immigrants make up one‑fifth of the Israeli population and one-seventh of the American one. The vast majority are settled migrants with at least 10 years of residence in the host country (around five‑sixths and three‑fourths in Israel and the United States, respectively). Israel encourages migration of the Jewish diaspora, while family reunification is an important principle guiding immigration policy in the United States. As a result, nearly two‑thirds of permanent immigrants in the United States have moved primarily for family reasons.

Despite a lower share of labour migrants than in the countries included in Group 1.1, immigrants (and their children) boast favourable labour market outcomes, and a comparatively large share is highly educated (43% in the United States and 56% in Israel). Yet, these migrants face difficulties in finding employment commensurate with their qualifications. Around one‑third of those in employment are overqualified. In Israel, highly educated migrants are roughly twice as likely to be overqualified as their native‑born peers. What is more, migrants still lag behind the native‑born in the United States in terms of living conditions.

Group 2.1: Long-standing European destinations with predominantly EU-born/EU mobile citizens (Luxembourg, Switzerland)

These countries attract large numbers of highly educated labour migrants from the EU/EFTA area. While immigration is longstanding, there have been particularly significant inflows of tertiary-educated migrants over the past decade. As a result, migrants with less than 10 years of residence in the host country account for at least two-fifths of the immigrant populations in these countries.

Due to the high share of labour and free movement migrants (77% in Switzerland and 88% in Luxembourg among permanent flows over the last 15 years), the labour market outcomes of immigrants are generally good. More than 72% of the foreign-born are employed and overqualification rates are among the lowest in the OECD. However, living conditions of migrants are less favourable. Notably, immigrants disproportionately face challenges in finding adequate housing and depict higher relative poverty rates. In a similar vein, the educational and labour market outcomes of native‑born with foreign-born parents lag well behind those of their peers with native‑born parents. Furthermore, despite some improvements over the last decade, citizenship acquisition rates among migrants with at least ten years of residence remain low.

Group 2.2: Long-standing European destinations with predominantly non-EU migrants and a significant share of EU-born/EU mobile citizens (Austria, Belgium, Germany, the United Kingdom)

Since the 1950s, active “guest worker” policies in these countries attracted predominantly low-educated migrants from countries such as the former Yugoslavia, Türkiye, and Morocco, who carried out unskilled labour during the Post World War II economic expansion. Rather than staying temporarily, as initially foreseen, many of these immigrants eventually settled with their families. The United Kingdom is the exception in this group, as it received better educated labour migrants from its former colonies without having implemented “guest worker” programmes. Since the 1990s, most of these countries have also received significant inflows of humanitarian migrants, in particular Germany and Austria. Due to a surge in humanitarian migration in 2015/2016 as well as continuous inflows of EU mobility migrants over the last decade, the percentage of the foreign-born relative to the total population has grown in these countries. As of 2020, around two in five migrants have resided in their host country for less than ten years. Unlike in the first two groups, the share of highly educated migrants ranges only between 26 and 34% in these countries. However, among EU-born, at least two‑fifths are tertiary-educated (except for Germany, where less than one-third is tertiary-educated). Education levels are higher among all migrants in the United Kingdom, where around half hold a tertiary degree.

Although these countries host significant shares of labour migrants or accompanying family members (including those who arrived through free mobility), immigrants’ employment rates are much lower than those of the native‑born. Gaps are entirely driven by non-EU migrants and amount to at least 6 percentage points, except for the United Kingdom, where gaps are inexistent. Especially non-EU women face difficulties in the labour market and fare much worse than both non-EU men and their native‑born peers. Disadvantages related to the low educational attainment of immigrant parents have often been passed on to their children, who have much lower educational and labour market outcomes than their peers with native‑born parents (except for the United Kingdom again). Immigrants in these countries are also more likely to be poor, live in inadequate housing or report poor health compared with their native‑born peers, although gaps are much smaller in Germany and the United Kingdom. In Belgium, despite a large share of EU-born, outcomes of immigrants and their children resemble more those in group 2.3 below than those in Austria, Germany and the United Kingdom.

Group 2.3: Long-standing European destinations with predominantly non-EU migrants (France, the Netherlands)

Like the countries in group 2.2, France and the Netherlands adopted guest worker programmes to alleviate (unskilled) labour shortages during the post-war economic boom. In addition to these flows, they received significant numbers of labour and family migrants from their previous colonies, resulting in a predominantly non-EU migrant population. Many migrants (nearly 70% in France and 78% in the Netherlands) settled in urban areas with shares continuing to grow. In contrast to countries in Group 2.2, recent arrivals make up only a small share of the immigrant population. As a result, around three‑quarters of the foreign-born have resided in their host country for 10 years or more, and the vast majority of these (62% in France and 75% in the Netherlands) hold the citizenship of their host country.

Integration challenges resemble those of peer group 2.2 and are partly linked to the low educational attainment of a significant proportion (over one‑quarter in the Netherlands and one‑third in France) of the foreign-born population. Specifically, immigrants experience worse labour market outcomes than the native‑born with wide gaps in employment rates (7 percentage points in France and 16 in the Netherlands). Similarly, relative poverty, housing problems and health issues are much more widespread among immigrants than the native‑born with widening disparities over the last decade. The native‑born youth with foreign-born parents also tend to fare much worse in school and the labour market than their peers with native‑born parents.

Group 3.1: More recent destinations with a significant share of humanitarian migrants (Denmark, Norway, Sweden)

Since the 1990s, humanitarian migration has been an important driver of migration to these countries and has led to a growing diversity in terms of countries of origin. However, EU/EFTA free mobility and labour migrants still constitute the bulk of the migrant population (except for Sweden), accounting for more than three-fifths of the permanent immigration flows to Denmark and Norway over the last 15 years. Due to growing numbers of labour and free mobility migrants, as well as a surge in humanitarian migration in the aftermath of the Syrian crisis in 2015/2016 (although to a lesser extent in Denmark), the foreign-born share of the populations in these countries has increased by over one‑third over the last decade, amounting to on average 16% in 2021. Consequently, nearly half of all migrants have resided in their host countries for less than 10 years and even around one‑quarter for less than five years. At least two in five migrants hold a tertiary degree, a share that rose in the decade up to 2020 and is now similar to that of the native‑born.

Humanitarian migrants and their families as well as recent non-EU migrants are particularly vulnerable when it comes to their labour market integration and generally fall short of the high economic outcomes of the native‑born. As elsewhere, these groups perform poorly in the labour market and experience higher relative poverty rates and worse housing conditions than the native‑born. The same holds true for the native‑born with foreign-born parents, who lag behind their peers with native‑born parents in school and the labour market. Despite these issues, social integration as well as native‑born attitudes towards immigration are more favourable than in most other European countries. For example, immigrants who are eligible are much more likely to vote in national elections, show higher trust in the police and the legal system and are more likely to volunteer than immigrants elsewhere. Furthermore, in Sweden, six in seven settled migrants hold the Swedish nationality, while citizenship acquisition rates are much lower in Denmark and Norway.

Group 3.2: More recent destinations with a significant share of labour migrants (Costa Rica, Greece, Italy, Korea, Portugal, Spain)

Labour and family migrants account for the bulk of the foreign-born population in these countries. In the Southern European countries, economic growth coupled with fertility decline resulted in labour shortages in low-skilled jobs from the mid‑1980s onwards up to the global financial crisis, which were filled by non-European and later also Central and Eastern European migrants. During the same period, in Costa Rica, political stability and favourable economic conditions attracted a growing number of low-educated labour migrants, mainly from Nicaragua and other neighbouring countries. On average, migrants make up around 11% of the respective populations of these countries. In Korea, which receives high numbers of temporary labour migrants, the share is much lower and stands at around 4%.

In Costa Rica, Greece and Italy, immigrants are overrepresented at the lower end of the educational spectrum. Only around one in six hold a tertiary degree. By contrast, following significant growth over the past decade, this share is much larger in Portugal, Korea and Spain, where it stands at around one‑third. While overall employment levels of immigrants are similar to or higher than those of the native‑born (except Greece and Spain), migrants with a tertiary degree face difficulties in putting their skills fully into practice. They are much less likely to be employed than their native‑born peers and those who predominantly work in positions below their skill level. Immigrants are also much more likely to work part-time, hold a temporary contract or work overtime than the native‑born. They also lag behind in terms of living conditions, facing poverty rates roughly twice as high as the native‑born as well as much more pronounced housing overcrowding rates. These problems are passed on to their children, who show poor labour market outcomes, both in absolute terms and relative to their peers with native‑born parents. Portugal is an outlier in this regard. Due to substantial improvements in integration outcomes over the last decade, gaps between immigrants and the native‑born in overcrowding rates are much narrower and the poverty gap even reversed (in favour of migrants). In contrast to the other countries in this peer group, settled migrants in Portugal are also much more likely to acquire citizenship.

Group 3.3: More recent destinations with predominantly EU-born/EU mobile citizens (Cyprus, Iceland, Ireland, Malta)

These countries recorded large inflows of labour migrants over the last decade, predominantly from the EU/EFTA area. Around one‑third of the foreign-born in Iceland and Ireland have been living in the host country for less than 10 years, while shares in Malta and Cyprus even reach 50 and 60%, respectively. In contrast to the previous group, around two in five migrants are tertiary educated, with an even larger proportion in Ireland (56%).

Partly linked to the advantageous socio‑economic background of immigrants, differences in labour market performance and living conditions are generally marginal in these countries, if any. Yet results vary between countries and there are country-specific integration challenges in certain domains. For example, highly educated immigrants experience high incidences of overqualification in Iceland and Malta, where they are, respectively, roughly four and three times more likely to work in a job below their qualification level than the native‑born. Furthermore, in Cyprus, migrants are around twice as often affected by relative poverty as the native‑born. In Iceland, native‑born children of immigrants face difficulties integrating into the school system, with half lacking basic reading skills at the age of 15.

Group 4.1: Emerging destinations with a foreign-born population traditionally shaped by border changes and/or by national minorities and with a recent growing share of foreign-born (Bulgaria, Hungary, Slovak Republic, Slovenia)

The foreign-born population in these Central and Eastern European countries has been shaped by national minorities originating from neighbouring countries (as in Hungary) and border changes, mainly related to nation-building in the late 20th century. As a result, citizenship acquisition rates among settled migrants are among the highest in the OECD. In recent years, countries in this group have also witnessed significant inflows of predominantly labour migrants from Central, Eastern and South-Eastern Europe. Accordingly, recent migrants (with less than 10 years of residence) account for around one‑third of the migrant population, with an even larger share in Bulgaria (41%). Despite growing inflows, immigrants still make up a relatively small proportion of the overall population (less than 7%), except for Slovenia, where every seventh person is foreign-born. The share of migrants holding a university degree rose in all four countries but still varies widely, ranging from 18% in Slovenia to 52% in Bulgaria.

Similarly, integration outcomes are heterogenous. In Hungary, immigrants (and their native‑born children) fare well in the labour market and enjoy living conditions that are broadly similar to those of the native‑born. This is also the case in the Slovak Republic, albeit to a lesser extent. By contrast, in Bulgaria, they struggle integrating into the labour market and in Slovenia, they are disproportionately affected by relative poverty and poor housing conditions.

Figure 1.9. Overview of integration outcomes of the foreign-born population and their native‑born offspring

Note: 2018/2021: “+/ -”: immigrant or native‑born offspring outcomes (compared with native‑born or native‑born with native‑born parents) are more/ less favourable than on average in the OECD; “O”: no statistically significant difference (at 1% level) from the OECD average.

Evolution between 2009/11 and 2018/21: “+/-”: more than a 2 percentage point change to the favour/to the detriment of immigrants or native‑born offspring, “0” between a +2 percentage point change and a ‑2 percentage point change, for PISA: “+/-”: more than a 10 point increase/decrease in immigrants’ average reading scores, “0” between a +10‑point change and a ‑10 point change; the evolution refers to absolute values, not differences vis-à-vis the native‑born. “..” data are not available, or sample size is too small.

Group 4.2: Emerging destinations with a foreign-born population shaped by border changes and/or by national minorities and with a declining share of foreign-born (Croatia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania)

As in peer group 4.1, a significant share of the foreign-born in these countries were born abroad due to border changes in the early 1990s or form part of national minorities from neighbouring countries. At least four in five immigrants (and even 96% in Croatia) have resided in their host country for more than 10 years. Together with Poland, these countries host the largest shares of elderly among the immigrant population in the OECD. In Estonia and Latvia, over two-fifths of immigrants are aged 65 or above. Until recent refugee inflows (see Box 1.4), new arrivals were limited and could not offset the population ageing of the foreign-born. Therefore, the foreign-born population in these countries has declined over the last decade, in stark contrast to all other OECD countries, bar Israel and Cyprus. As of 2021, around one in seven people is foreign-born in these countries, with a smaller share in Lithuania (6%).

In the Baltic countries, integration outcomes are closely related to the age structure of the foreign-born population. With many working age immigrants being close to retirement age, participation as well as employment rates are lower among the foreign- than the native‑born. Furthermore, health issues among immigrants are of growing concern. They disproportionately suffer from overweight and are less likely to report good health than the native‑born, even after considering immigrants’ higher age. Relative poverty rates of immigrants also exceed those of the native‑born (except for Lithuania) and especially old age poverty has increased considerably over the last decade, among immigrants and the native‑born alike. By contrast, as more than four in five migrants are homeowners, integration outcomes related to housing tend to be more favourable. Croatia differs from the other countries in terms of integration, showing generally smaller or inexistent gaps both in labour market outcomes and living conditions.

Group 4.3: Emerging destinations with recent significant humanitarian migration flows (Chile, Colombia, Finland, Türkiye)

This group encompasses a heterogenous set of countries, which had a small immigrant population until the early 2010s but have seen large numbers of humanitarian migrants arriving over the last decade. Consequently, the foreign-born population has increased considerably in all four countries, most notably in Colombia. While Chile and Colombia have received predominantly humanitarian migrants from Venezuela, who share the same language and have relatively high formal educational attainment levels, Finland and Türkiye host significant shares of refugees from Asian countries such as Syria and Iraq, where education levels are more diverse. As a result, integration outcomes vary widely between these four countries. Immigrants are more likely to be employed than the native‑born in Chile and Colombia, while the reverse holds true in Finland and Türkiye. Furthermore, in Colombia, two‑thirds of immigrants live in overcrowded dwellings, a share that is more than twice as high as among the native‑born. By contrast, in Chile and Finland, housing conditions of immigrants are much more similar to those of the native‑born.

Group 4.4: Emerging destinations with recent significant labour migration flows (Czech Republic, Poland, Japan)

These countries have received growing inflows of labour migrants from geographically close countries as population ageing and labour shortages have increased the need for foreign labour. As parts of these flows are temporary, the foreign-born population is still relatively small (2% of the total population in Poland and Japan, and 8% in the Czech Republic, where a significant part of the foreign-born population has been shaped by border changes in the early 1990s). Educational levels of migrants in these countries vary, with large shares of tertiary-educated in Poland and Japan (60 and 47%, respectively) and a much smaller proportion of around one‑third in the Czech Republic. Given that most immigrants arrived for employment purposes, economic integration outcomes are generally favourable. For example, immigrants’ employment rates have increased considerably over the last decade and now exceed those of the native‑born, albeit only slightly, in Japan. Indicators on living conditions are only available for the Czech Republic and Poland. In these countries, gaps tend to be smaller than in most other OECD countries.

Group 4.5: Emerging destinations with predominantly national returnees born abroad (Mexico, Romania)

These countries have a large diaspora, and the foreign-born offspring of national returnees account for a significant share of their foreign-born population. Because return migration has increased in recent years, the foreign-born in these countries are much younger than in other OECD countries. More than one‑third are below the age of 15, and a significant share has reached the working age only recently. As the foreign-born populations are still rather small, evidence on integration outcomes is limited. The scarce evidence shows that, despite higher educational attainment, the foreign-born fare worse in the labour market than their native‑born peers, which might be partly attributable to their younger age. Gaps in employment rates are relatively wide and have increased over the last decade.

Box 1.5. Methodological note: Measuring gaps of migrants in the EU and OECD

Integration outcomes vary considerably between countries and are shaped by the respective national context. Against this backdrop, it is useful to look at OECD- or EU-wide results of integration outcomes. For each indicator, this report shows the outcome of all immigrants residing in the OECD and EU vis-à-vis that of the native‑born – the so-called OECD/EU total. In contrast to the OECD/EU average, i.e. the mean of the outcomes for all OECD or EU countries, this estimate considers all OECD/EU countries as a single entity, to which each country contributes proportionately to the size of its native‑ or foreign-born population. However, as immigrants are unequally distributed across OECD and EU countries, OECD- or EU-wide gaps between immigrants and the native‑born need to be interpreted with care. For example, only five destinations (Germany, France, Austria, Spain and Italy) host over two‑thirds of the roughly 54 million immigrants living in the EU, while accounting for less than 60% of the native‑born population. Consequently, the situation in these countries is reflected to a greater extent in the average indicator values of the foreign-born compared with those of the native‑born, while the opposite is true for countries with a comparatively small share of immigrants. For certain indicators, this compositional effect can obscure gaps visible at the country level.

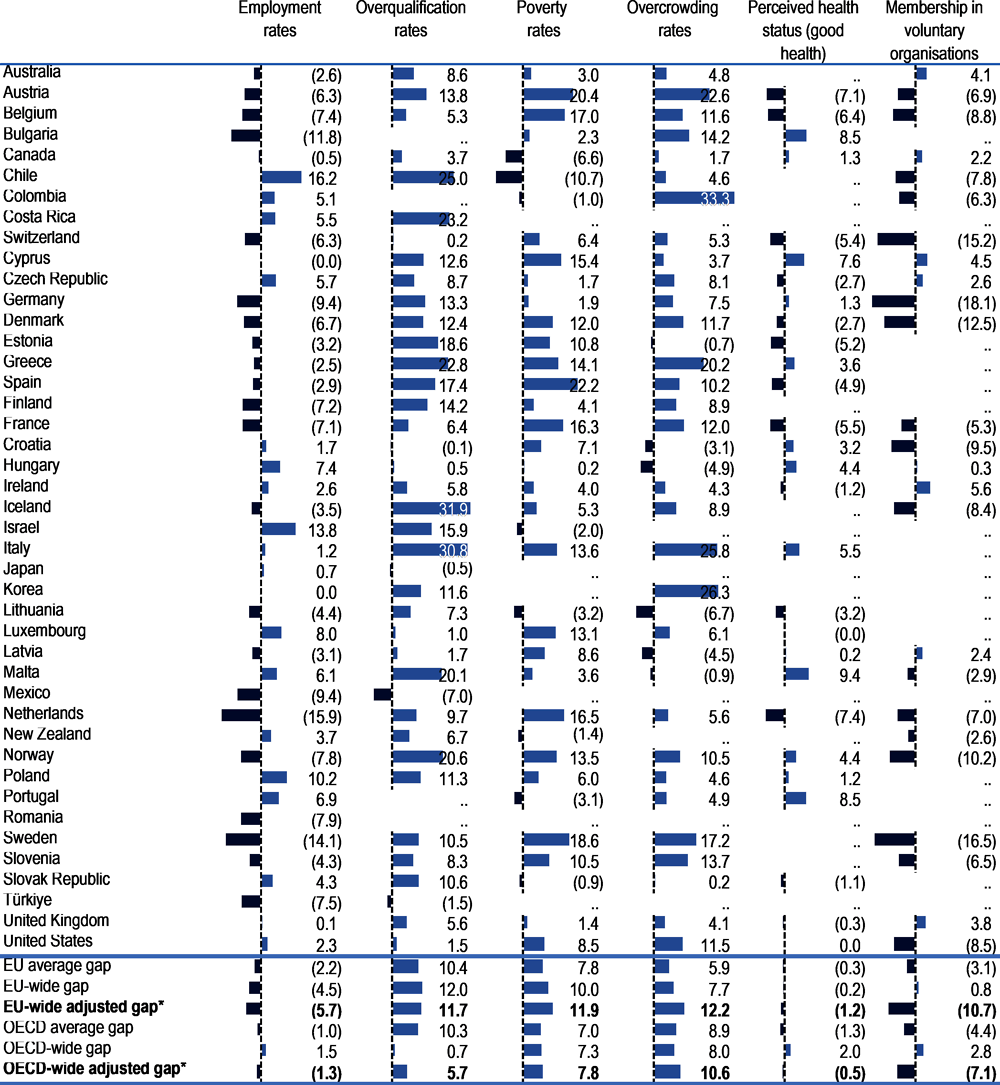

One approach to account for this imbalance is to weigh the gap between the foreign- and native‑born by the size of the foreign-born population – the so-called OECD- or EU-wide adjusted gap. This puts more weight on gaps found in countries with a large immigrant population. Figure 1.10 contrasts gaps in OECD and EU totals with the weighted gaps for selected indicators. The weighing does not exert a strong effect on most core indicators, including employment, unemployment, overqualification rates, and the perceived health status. However, the indicator on membership rates in voluntary organisations shows that, in certain cases, results can change substantially. Participation rates in voluntary organisations are below average among the native‑born in countries with a large share of native‑born (e.g. Poland and Romania) and above average among the foreign-born in countries with a large share of immigrants (e.g. Germany and Austria). Consequently, although immigrants lag behind the native‑born in two‑thirds of countries, the EU total shows similar participation rates among both groups. However, after weighing gaps by the size of the foreign-born population, the native‑born are 11 percentage points more likely to participate in voluntary organisations than immigrants. Weighing EU-wide gaps by the size of the foreign-born population also has a significant impact on poverty rates, overcrowding rates, the share of elderly living in a substandard accommodation and unmet medical needs, albeit to a lesser extent. Similar but slightly smaller effects were found when applying this method to OECD-wide gaps.

Figure 1.10. Gaps between immigrants and native born at a glance

Note: *Adjusted gaps are weighed by the size of the foreign-born populations of each country. A negative (positive) figure implies that the rates are lower (higher) for immigrants than for the native‑born. Negative figures are shown in brackets.

Further notes and sources are to be found in the respective StatLink.

1.4. The evolution of integration outcomes over time

To provide a long-term vision on potential integration progress, it is crucial to monitor integration outcomes over time. This publication pursues several approaches to gauge progress in integration outcomes. For virtually all indicators, it compares the situation of the immigrant and native‑born population with that a decade earlier.3 Whenever possible, it also compares outcomes of migrants with a different length of stay in the host country. Furthermore, it analyses intergenerational progress in educational outcomes.

The migration landscape across the OECD has changed significantly over the last decade. Due to growing numbers of migrants benefitting from free mobility alongside inflows of humanitarian migrants in Europe and South America since 2015, the foreign-born population has increased virtually everywhere. Overall, integration outcomes in the OECD tended to improve over the last decade, although there is significant variation between countries and across indicators.

Labour market outcomes of immigrants improved substantially in the OECD after the protracted economic downturn starting in 2007/2008. Between 2011 and 2021, employment rates of immigrants increased nearly everywhere, reducing prior gaps with the native‑born. In most countries, differences between immigrants and the native‑born have also become smaller for (long-term) unemployment rates, involuntary part-time employment, temporary contracts and overqualification rates. These positive trends were observed despite the disproportionately strong negative impact of the COVID‑19 pandemic on migrant workers. While the crisis temporarily put the decade‑long progress to a halt, outcomes bounced back more strongly for migrants. In 2021, they already returned to or even exceeded pre‑crisis levels in most countries.

Not only better labour policies and more favourable economic conditions might have driven this progress but also changes in the socio-economic composition of the immigrant populations. In 2020, nearly half of all recent migrants (with less than 5 years of residence) in the OECD held a university degree, compared with less than one‑third a decade earlier. As educational attainment improves access to the labour market, recent arrivals in 2021 are more likely to work than their peers a decade earlier in over two-thirds of countries. There has been growth in the employment rate of recent migrants of around 4 percentage points in the EU and even more in the United States and Canada.

In a similar vein, in most countries, native‑born children with foreign-born parents are slowly catching up with their peers with native‑born parents, both in terms of academic achievements and labour market outcomes. Two-thirds of countries reported progress in the reading performance of children of immigrants between 2009 and 2018, while the performance of their counterparts with native‑born parents remained stable across both the EU and OECD. In addition, despite the COVID‑19 pandemic, all key labour market indicators (employment, unemployment and overqualification rate) have improved between 2012 and 2020 among young adults in the EU. Progress has been more pronounced among the native‑born with foreign-born parents than among their peers with native‑born parents. This was generally not the case outside of the EU.

The picture is more mixed when it comes to the living conditions of immigrants. In around half of countries, relative poverty rates decreased more among immigrants than the native‑born, while in the other half, the foreign-born experienced a steeper increase in relative poverty than the native‑born. A similar pattern was observed for overcrowding rates. Only with respect to health did most countries achieve significant advances in the 2010s for both the foreign- and the native‑born. It seems that the COVID‑19 pandemic did not halt this trend, although this could also be due to biases in self-reported data or, in some countries, interviews conducted before the global spread of the disease. Progress in living conditions was also uneven across countries. For example, across the EU, overcrowding rates increased among immigrants while declining among the native‑born, but this was not the case outside of the EU. Nevertheless, even within the EU, there are wide discrepancies. While in Portugal and Finland, for example, living conditions of immigrants have converged towards the level of the native‑born (except for housing in Finland), they drifted further apart in the Netherlands, Sweden and France.

The evolution of indicators on social integration and civic engagement has also been less clear-cut. Partly due to more stringent requirements to acquire citizenship as well as changes in the immigrant composition, citizenship acquisition rates have dropped over the past decade in slightly less than two‑thirds of countries. Furthermore, voter turnout in national elections among migrants with the host-country nationality declined between 2002‑10 and 2012‑20 across the EU, although the reverse was observed in the United States. Yet trust in public institutions, such as parliament, has increased among immigrants in the EU over the past decade, even more so than among the native‑born. The picture is similarly ambiguous when it comes to social cohesion. Although in the EU, more native‑born think positively about migration today than a decade ago, perceived discrimination has increased.

1.4.2 Integration tends to improve when migrants stay longer

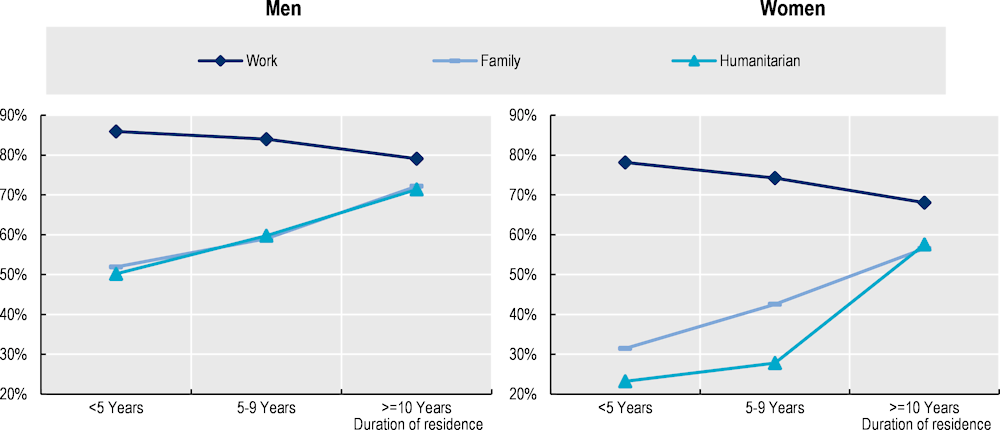

Another way of measuring progress in the integration process is to compare outcomes of immigrants with a different length of stay in the host country. Generally, integration outcomes improve when migrants stay longer in the host country. However, there are considerable differences between different migrant categories.

Figure 1.11 shows employment rates for the EU as a whole by reason for migration, duration of stay and gender. Results should be interpreted with caution as nonresponse rates for the question on the reason for migration are relatively high (above 40%) in Austria, Estonia and Denmark. Progress in labour market integration is particularly visible among humanitarian and family migrants, who tend to have only weak attachments to the labour market in the host country upon arrival. In 2021, only around half of all recent immigrant men who came for family reasons were employed. EU-wide employment rates of recent immigrant men who migrated for humanitarian reasons were similar, although this group tends to perform worse in most countries. This is attributable chiefly to the favourable labour market outcomes of recent Venezuelan refugee arrivals in Spain, whose shared language, family ties and high educational levels ease their integration. After ten years of residence, shares peak at around 70% for both humanitarian and family migrant men but remain slightly under the level of their native‑born peers at 74%.

Figure 1.11. Employment rate by reason for migration, duration of stay and gender in the EU

Women who migrate for family and humanitarian reasons struggle even more to enter the labour market, with less than one‑third and one‑quarter being employed, respectively, in the first five years of their stay. However, after ten years of residence, employment rates reach nearly 60% for both groups. By contrast, both male and female labour migrants have high employment rates from the start, which decline slightly with length of stay.

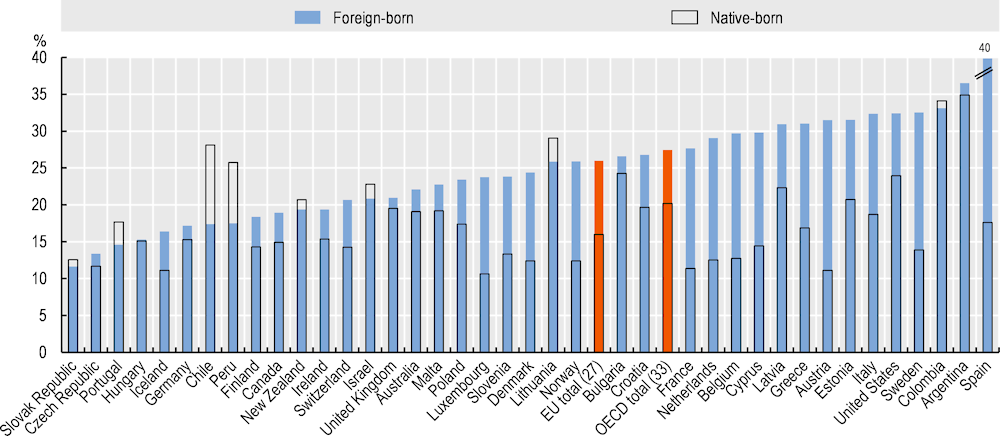

1.1.3. Integration tends to improve over generations

For certain indicators, retrospective measures of parental outcomes are available, which allow to measure progress in integration over generations. For example, the 2019 EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU SILC) survey asks respondents about the highest educational attainment of their parents. This allows to compare intergenerational educational mobility of native‑born people with at least one foreign-born parent with that of their peers with native‑born parentage. As young people with highly educated parents cannot experience upward educational mobility, they are not considered here. These data show that native‑born with foreign-born or mixed parentage have higher chances of experiencing upward educational mobility than their peers with native‑born parents. Across the EU, 54%of the former group managed to exceed their parents’ educational attainment, compared with only 47% of the latter (Figure 1.12).

Figure 1.12. Share of youth with higher educational attainment than their parents

Another way to chart intergenerational progress across countries is to compare the outcomes of native‑born children of immigrants with those of immigrants who arrived as children in the same age group. This approach captures the outcomes of the two groups at the same point in time and environment. Yet, inferences about intergenerational integration progress are likely to be biased due to the different parental arrival times of those who arrived as children and those who are native‑born offspring of immigrants. If recent arrivals show better (or worse) integration outcomes from the onset, a comparison of their outcomes with those of the children from previous cohorts will (over-) understate intergenerational integration progress. Based on this method, results from Chapter 7 suggest that certain integration outcomes have improved over generations. Across the OECD, native‑born children with foreign-born parents outperform their immigrant counterparts who arrived before the age of 15 when it comes to school performance and housing conditions. By contrast, they fare similar or worse with respect to labour market integration outcomes (employment, unemployment, over-qualification). However, this result can partly be attributed to a more advantaged socio-economic background of younger immigrant cohorts, on average.

1.5. Conclusion

EU and OECD countries are home to an increasing number of immigrants and their children, and their integration continues to be high on the policy agenda in many countries. Monitoring integration outcomes at the international level can provide important insights in this context. It helps to provide benchmarks, identify common integration challenges across countries and gather useful information that cannot be obtained by only using national data. As differences in integration outcomes also hinge upon the composition of the foreign-born populations, international comparisons between countries with similar main features of the foreign-born population are particularly valuable. Against this backdrop, OECD and EU countries have been classified in this report into 13 peer country groups, which share similarities in terms of the size and category of entry of the migrant population as well as their experience with immigration. While integration outcomes vary widely between countries, each country faces certain challenges and there is no universal champion. Indeed, in most countries and most integration domains, immigrants and their children lag behind the native‑born and their respective children. However, there has been substantial progress over the last decade in some areas, especially when it comes to the labour market integration of immigrants. This improvement is attributable to higher educational levels of recent arrivals, better integration policies and more favourable labour market conditions than a decade ago. Furthermore, integration outcomes tend to improve when migrants stay longer in the country and across generations. While these results are encouraging, there is still a long way to go to fully close the gap between immigrants (and their children) and the native‑born (and their respective children).

Annex 1.A. Overview of the structure of the publication

Annex Table 1.A.1 presents an overview of the characteristics and the areas of integration included in this publication, with a detailed list of the indicators presented for each area.

Annex Table 1.A.1. Contextual information and areas of integration of immigrants and their children considered in the publication

|

|

Description |

Measured by |

|---|---|---|

|

Characteristics (Chapter 2) |

The socio-demographic background characteristics of immigrants drive integration outcomes. They include age, gender, family structure, living conditions, and geographical concentration. In addition to such factors, which also apply to the native‑born, there are certain immigrant-specific determinants like category of entry, duration of stay, and region of origin. A grasp of how they differ from country to country and how immigrants fare relative to the native‑born is a prerequisite for understanding integration outcomes. |

Foreign-born share of population by: - Rural or urban area - Gender Fertility Immigrant households Household composition Immigration flows by legal category Distribution of the immigrant population by: - Duration of stay - Regions of origin |

|

Skills and the labour market (Chapter 3) |

Immigrants’ skills and how they integrate into the labour market are fundamental to becoming part of the host country’s economic fabric. Skills and qualifications are obviously indicators of immigrants’ ability to integrate in the host society. They have a strong bearing on career paths and influence what kind of job they find. Employment is often considered to be the single most important indicator of integration. Jobs are immigrants’ chief source of income and confer social standing. However, while employment is important per se, job quality is also a strong determinant shaping how immigrants find their place in society. |

Distribution of the immigrant population by: - Educational attainment - Place of education - Language proficiency Access to adult education and training Employment rate Labour market participation rate Unemployment rate Long-term unemployment rate Share who fear losing or not finding a job Share of inactive who wish to work Share of employees working: - Long hours - Part-time - Involuntary part-time Jobs distribution by: - Types of contracts - Job skills Over-qualification rate Share of self-employed Reason for being self-employed Proportion of revenue coming from the main client for self-employed Firm size |

|

Living conditions (Chapter 4) |

This chapter presents a range of indicators on living conditions, namely immigrants’ income, housing, and health. |

Median income Income distribution Relative poverty rate Share of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion (AROPE) Home ownership rate Share of renters at market rate Share of renters at reduced rate Overcrowding rate Share of substandard dwellings Housing cost overburden Share of people reporting difficulties in accessing non-recreational amenities Share of people reporting at least one major problem in their neighbourhoods Share of people reporting good health status or better Share of overweight individuals Share of daily tobacco smokers Share of people who report unmet medical needs Share of people who report unmet dental needs Share of people that find affording healthcare difficult Share of households not having used any health- or dental care services over the past 12 months |

|

Civic engagement and social integration (Chapter 5) |

Social integration is difficult to measure. The indicators presented here are related to citizenship take‑up, participation in elections and in voluntary organisations, trust in host-country institutions and a range of indicators related to public opinion. |

Acquisition of citizenship rate National voter participation rate Host-country perceptions of the presence of immigrants Perceived economic and cultural impact of immigration Membership rates in voluntary organisations Share of people who trust in the police, the parliament or the legal system Share of people who think that integration of immigrants is very or fairly successful Host-society views on the evolution of integration outcomes Perceived social integration factors for a successful integration Self-reported discrimination based on ethnicity, nationality or race, by parental origin |

|

Integration of the elderly immigrant population (Chapter 6) |

Elderly migrants are a growing group in most countries. Yet as they reach the final stage of their lives, little is known about their integration challenges and outcomes. Those challenges are difficult to identify, as elderly migrants are often very different from other migrant cohorts. They reflect long-standing migration flows, whose characteristics may be far from following cohorts. In most longstanding destinations, the aged immigrant population has been shaped by arrivals of low-educated “guest workers” and subsequent family migration. This chapter presents a first-time overview of select indicators for this group before the beginning of the COVID‑19 pandemic. |

Share of elderly and very old Relative poverty rate Share of substandard dwellings Share of elderly reporting good health status or better Access to professional homecare |

|

Integration of young people with foreign-born parents (Chapter 7) |

Youth with foreign-born parents who have been raised and educated in the host country face challenges that are different from those of migrants who arrived as adults. This chapter presents their educational outcomes, indicators on the school to work conditions, along with indicators on living conditions and social integration that are particularly pertinent for this group. It compares outcomes for native‑born children of immigrants with those of children of native‑born and of immigrants who arrived as children. |

Youth with foreign-born parents by: -Parental origin -Educational attainment Children with foreign-born parents Participation in Early Childhood Education and Care Concentration of students with foreign-born parents in schools Literacy scores Low school performers in reading Share of resilient students Sense of belonging at school Share of students who report having been bullied Share of students who feel awkward and out of place at school Share of students who agree that immigrants should be treated as equal members of society Share of students who treat people with respect regardless of their “cultural background” Share of students being able to overcome difficulties when dealing with people from “other cultural backgrounds” Share of students who think that most of their teachers have some discriminating attitudes towards other cultural groups Dropout rates NEET rate Share of youth with a higher educational attainment than their parents Employment rate Unemployment rate Overqualification rate Share of employment in the “public services” sector Relative youth poverty Relative child poverty Youth overcrowding rates Child overcrowding rates Share of young people who have a quiet place to study National voter participation rate Self-reported discrimination based on ethnicity, nationality or race, by parental origin |

|

Third-country nationals (Chapter 8) |

This chapter considers the full set of “Zaragoza indicators” for third-country nationals (TCN) in the European Union and other European OECD countries, along with additional pertinent indicators. It compares their outcomes with those of nationals of the country of residence and other EU nationals. |

Share of TCN, by: -age -duration of stay -regions of nationality -educational attainment Employment rate Labour market participation rate Unemployment rate Share of self-employed Firm size Overqualification rates Median income Income distribution Relative poverty rates Home ownership rate Share of renters at market rate Share of renters at reduced rate Share of people reporting good health status or better Share of TCN with long-term residence status |

New features of this edition

Following three previous publications in 2012, 2015 and 2018, this is the fourth edition of Indicators of Immigrant Integration. To provide a holistic view on integration, presented in an easy to grasp format, it introduced a number of new features compared to the previous publications.

First, new indicators have been added to this edition as a response to current integration challenges. For example, the COVID‑19 pandemic has demonstrated how lifestyle and access to healthcare affect health risks. The national lockdowns implemented during the pandemic have also highlighted the importance of living in decent housing conditions. Against this backdrop, this edition of Indicators of Immigrant Integration presents a more extensive set of indicators on living conditions. It covers new aspects of housing and health, such as the housing costs overburden rate, characteristics of the neighbourhood, health risk factors and access to healthcare. Furthermore, it explores marginalisation by including an indicator on poverty and social exclusion risks.

Annex Box 1.A.1. How to read this publication

This edition of Indicators of Immigrant Integration has a new structure for the presentation of each indicator. A box with the indicator context at the beginning of each indicator does not only provide the definition, as previously, but, where appropriate, explains the importance of the respective indicator for immigrant integration as well as potential measurement issues. It is followed by three paragraphs. The first paragraph describes the current situation across OECD and EU countries. The second paragraph traces the evolution of the indicator over the past decade. The third paragraph discusses contextual factors explaining differences across countries. It generally does so along four main categories: gender, education, EU/non-EU origin (for EU countries) and the duration of stay. At the end of each page, a “main findings” box summarises the most important takeaways.

In addition, the fight against social exclusion has become increasingly important on the policy agenda. To better grasp this reality, this edition presents several new indicators on social integration, including the participation in voluntary organisations. As social cohesion, a critical factor for integration, also depends on the attitudes of the host society, the chapter also covers several new indicators on the views on integration of the native‑born. It further contrasts opinions on the development of integration outcomes with reality.