The recovery in the European Union and euro area has been disrupted by the energy price shock and the cost-of-living crisis that followed Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine. EU policies helped avoid a severe downturn, but the near-term outlook is clouded by uncertainty and downside risks. Monetary and fiscal policy need to remain restrictive to lower underlying inflationary pressures. Fiscal sustainability should be grounded in efficient public spending and improved economic governance. To facilitate structural change, barriers in the Single Market need to be reduced further and complemented by an efficient early-stage support for green innovation.

OECD Economic Surveys: European Union and Euro Area 2023

1. Key Policy Insights

Abstract

The European Union is tackling critical challenges

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought multiple challenges and uncovered existing weaknesses, which elicited new policy responses at the EU level. Recovery from the pandemic has been cut short by ongoing global supply chain disruptions, increasing energy and commodity market pressures and high uncertainty following Russia’s unprovoked war of aggression against Ukraine. These mostly external shocks have turned 2022 into a particularly difficult year for Europe. War is taking place on European soil creating a humanitarian crisis and significant disruptions to economic activity. Inflation in the euro area and the EU has reached levels not seen in advanced economies in decades, and growing trade tensions coupled with increasingly protectionist industrial policies are endangering the rules-based international economic order. In the presence of these immediate challenges, more long-term tasks such as climate‑change mitigation and the digital transition are in the danger of fading into the background.

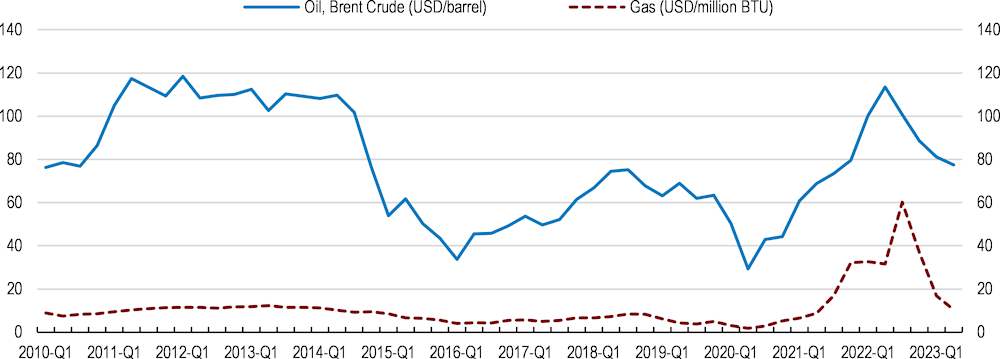

The policy response of the European institutions, both at the EU and euro area level, has been robust and creative. The EU continues to provide substantial humanitarian, military and financial support to Ukraine, so far amounting to EUR 55 billion. The EU also succeeded in coordinating an effective and timely reaction to the energy crisis, strengthening energy security. The ECB has tightened monetary policy, albeit belatedly, to tame inflation. The European Commission has followed with reform proposals aimed at improvements in economic governance important for the functioning of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). This work has paid off: unlike in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, trust in the EU has been preserved and even strengthened, while support for the common currency, which welcomed Croatia as a new member at the start of this year, is at a historical high (Figure 1.1). The EU and the euro area are acknowledged by their citizens as effective protection mechanisms, useful for addressing both immediate risks and long-term challenges.

Figure 1.1. Trust in the EU has been preserved and support for the euro is unprecedented

Share of survey respondents, per cent

Note: Surveyed respondents were asked the following questions: (1) "Are you for or against a European economic and monetary union with one single currency, the euro?", and (2) "Do you tend to trust the European Union institutions?". The series "In favour of European economic and monetary integration" (blue line) refers to respondents in the euro area countries, while the series "Trusting the EU institutions" (dotted brown line) refers to respondents in the European Union countries.

Source: Standard Eurobarometer 98 - Winter 2022-2023, https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2872

However, the challenges that lie ahead may be as large as those recently confronted. Over the past decade, greenhouse gas emission reductions happened mostly in sectors covered by the Emission Trading System (ETS). In contrast, sectors not covered by the ETS have contributed little to emission reduction. Aggregate labour productivity has been trending downwards for decades, as in other major economies. In the EU, labour productivity growth that soared in 2021, in the aftermath of the pandemic, has dropped to 0.7% in 2022.

Monetary policy must continue its restrictive stance to durably reduce inflation, while taking financial stability into account. Fiscal policy needs to support monetary policy, ensuring that the macroeconomic policy mix for the euro area is sufficiently restrictive to bring down inflation. That means better targeting of the fiscal support and implementing the Next Generation EU and the National Recovery and Resilience Plans efficiently to ensure that the fiscal stimulus from additional public investment does not push up inflation in the medium term. The EMU institutional architecture has to be renovated and the complex set of EU fiscal rules replaced by a system of economic governance that will improve both compliance with and national ownership of the rules.

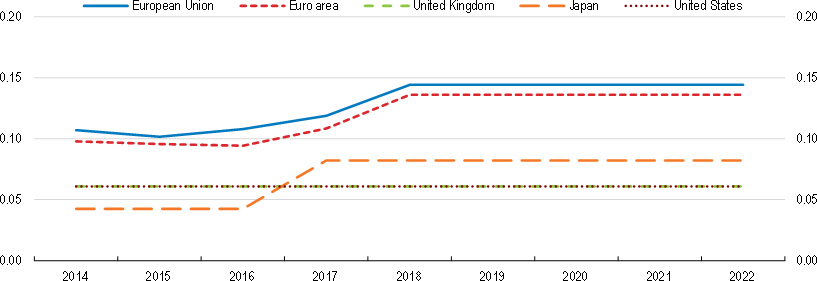

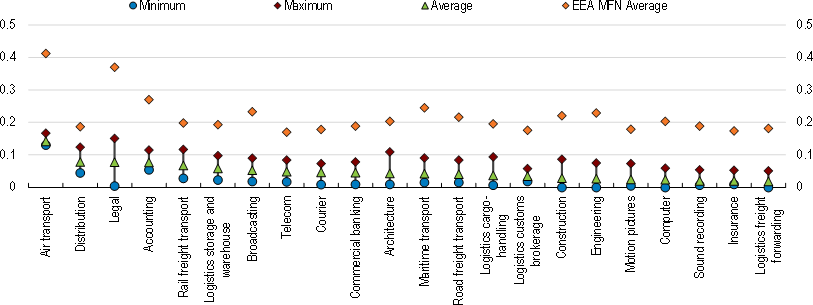

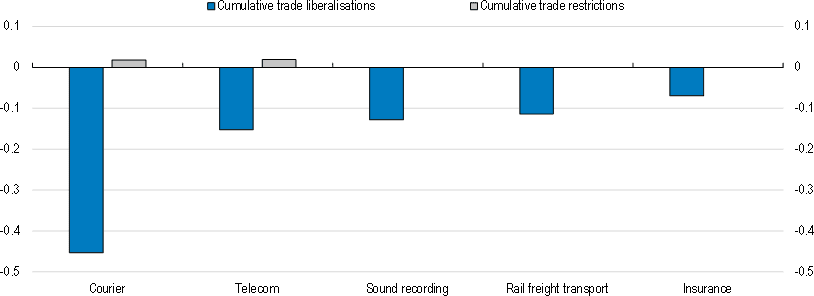

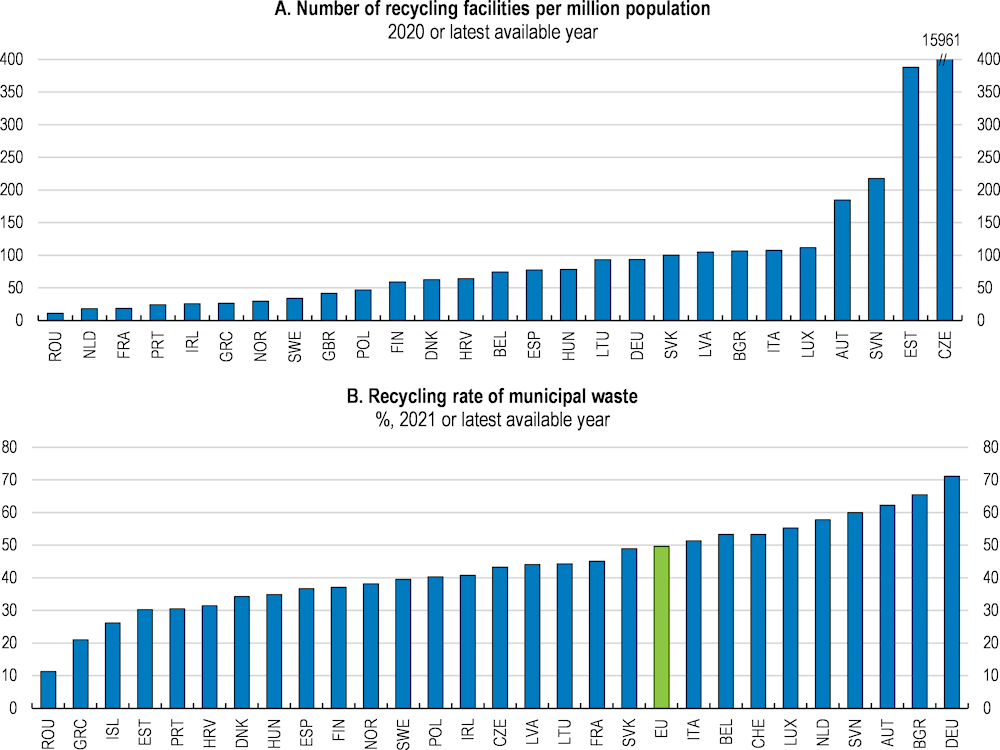

Macroeconomic stabilisation can be helped by further developing the Single Market, which would alleviate cost and price pressures by expanding long-term productive capacity of EU countries. The Next Generation EU programme will provide some of the considerable investment needed to make the Single Market work for the green and digital transitions. But public investment will have to be accompanied by more private capital, and alleviating financing constraints, particularly for small and medium-sized firms, is key for meeting the environmental challenges. More also needs to be done in removing the persistent barriers in services trade and augmenting labour mobility. In addition, the harmonisation of national regulations with EU rules in the area of circular economy and construction can directly help fulfil the ambitious emission reduction targets.

Apart from ensuring a level-playing field, growing the Single Market entails an appropriately calibrated industrial policy enhancing resilience and supporting productive capabilities. Further relaxation of the state-aid rules risks creating uneven conditions across countries, reflecting the amount of fiscal space in the various countries rather than opportunity costs and synergies. Instead of harmful subsidisation races, the EU could focus on international co-operation to avoid new dependencies and join the efforts of governments and businesses to improve risk preparedness.

Looking ahead, a key challenge is to accelerate decarbonisation efforts in Europe. This requires that all sectors contribute to emission reductions and calls for an extension of emission trading to agriculture and transportation. Such efforts should be complemented by measures to shift to cleaner energy and improve energy efficiency.

Against this background, the Survey has three main messages:

Monetary and fiscal policies must provide sufficiently restrictive macroeconomic conditions to bring down inflation and ensure that inflation expectations remain firmly anchored at the 2% target. The economic governance reform, which could help improve fiscal outcomes, is an integral part of this effort.

The Single Market is an essential driver of long-term growth with considerable potential for further deepening. Beyond providing a level playing field, the Single Market could be leveraged to enhance resilience. Further reducing existing barriers to services trade and labour mobility, while protecting workers’ rights, will also facilitate the digital and green transitions. Continuing to fight corruption and fraud is necessary to strengthen trust in public institutions.

The green transition requires further efforts to reduce emissions by using the entire toolbox of mitigation policies, including carbon pricing and regulatory measures. This entails greater harmonisation of carbon prices across countries and sectors, before raising them gradually. Also, more integrated electricity markets will be key for the energy transition and achieving energy security.

Economic recovery has been slow and uneven

The recovery has been hampered by the energy crisis and high inflation

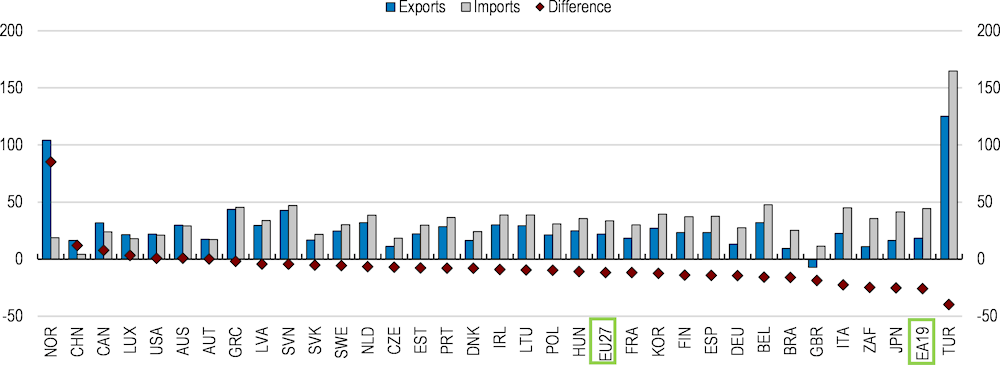

Europe has been hit hard by Russia’s unprovoked war of aggression against Ukraine and the energy crisis that followed. In the wake of the pandemic, growth rebounded in 2022, reflecting government support of about 1.2% of EU GDP to households and firms, as well as improvements in global supply chains and stronger demand from global reopening. Even so, the large negative terms-of-trade shock that sharply increased prices of imports, such as energy, relative to export prices, has been persistent and heterogenous across European countries, reflecting varying energy needs and supply chains. It amounted to a considerable transfer of wealth away from Europe (Figure 1.2), which continued, despite lower imports of energy and gradually decreasing energy prices, to contribute negatively to economic growth until the third quarter.

Figure 1.2. Europe has been hit strongly by the energy crisis

Per cent changes in trade in goods values

Note: March-July 2022 compared with the same months of 2021.

Source: OECD International Trade Statistics database.

The EU economy has contained the adverse impact of the war in Ukraine and the surge in energy prices thanks to coordinated and timely policy action. The measures resulted in rapid diversification of supply and a sizeable fall in gas consumption. The sharp deterioration of the terms of trade in 2021 and 2022 was greater in the EU than in many advanced economies. Policy actions at the EU and national levels helped enhance resilience and mitigate the negative effects on household income and productive capacity. Gradually declining energy prices have recently helped reverse the negative terms-of-trade shock and reduced production cost pressures.

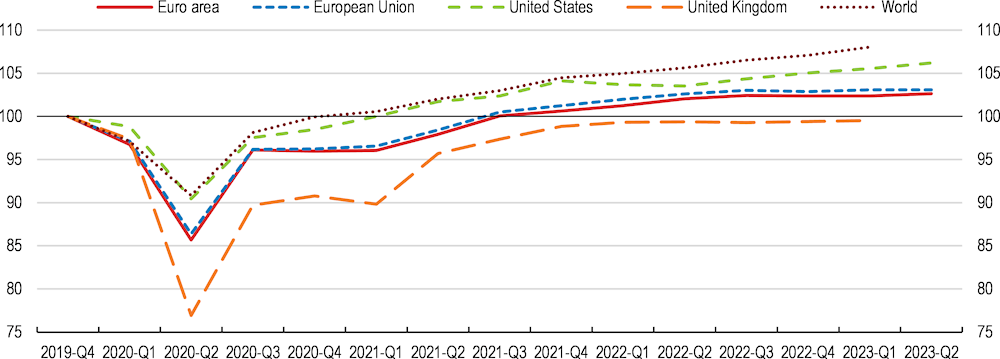

The recovery of European economies has been lagging other regions (Figure 1.3). GDP growth slowed to 3.5% in 2022 in both the EU and the euro area, following a rebound from the pandemic that resulted in growth above 5% in 2021. Private consumption remained resilient, supported by continuing employment gains, a further decrease in the savings rate and fiscal support mitigating the energy crisis. Consumer spending on services continued to increase and durable goods consumption grew markedly in the second half of 2022, reflecting reduced supply chain disruptions. Increasing interest rates and elevated uncertainty have had limited effects on gross fixed capital formation so far. The contribution of gross fixed capital formation to GDP growth has been complemented by an improved trade balance driven by the recent decline in energy prices.

Figure 1.3. The rebound in GDP growth has been relatively weak

Real GDP, index 2019-Q4 = 100

Note: Data refers to the euro area including 19 countries.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections database; and Eurostat National Accounts database.

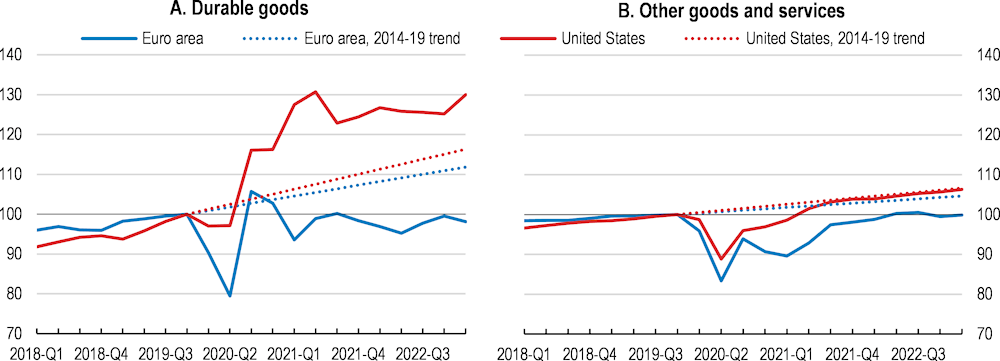

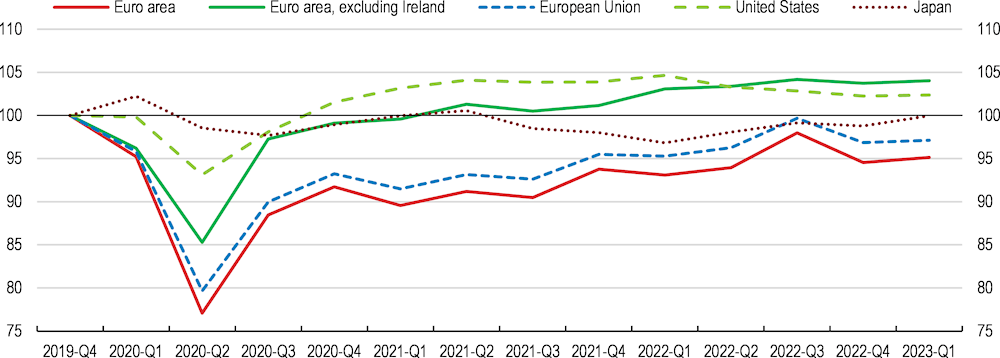

The relatively slow recovery reflects the negative terms-of-trade shock from the war in Ukraine as well as sluggish private consumption during most of the pandemic period and weak investment, both of which pre-date the war. As discussed in the 2021 OECD Economic Survey of the European Union (OECD, 2021[1]), the resurgence of the pandemic in the autumn of 2020 and a new wave of infections in the first months of 2021 forced EU countries to impose additional containment measures, which further delayed the recovery (Figure 1.4). Similarly, the weak level of euro area investment can be linked to a sharp contraction during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic followed by a slow rebound, although these dynamics are driven to large extent by the investment data for Ireland (Figure 1.5).

Figure 1.4. The rebound in consumption has been limited

Real personal consumption expenditures, index 2019-Q4 = 100

Note: Other goods consist of semi-durable and non-durable goods. Only euro area member countries that are also members of the OECD (17 countries) are considered.

Source: OECD National Accounts database; and OECD calculations.

Figure 1.5. Investment in the euro area continued to recover in 2022

Real gross fixed capital formation, index 2019-Q4 = 100

Note: Data refers to euro area member countries that are also members of the OECD (17 countries) and to the 27 EU Member countries.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections database.

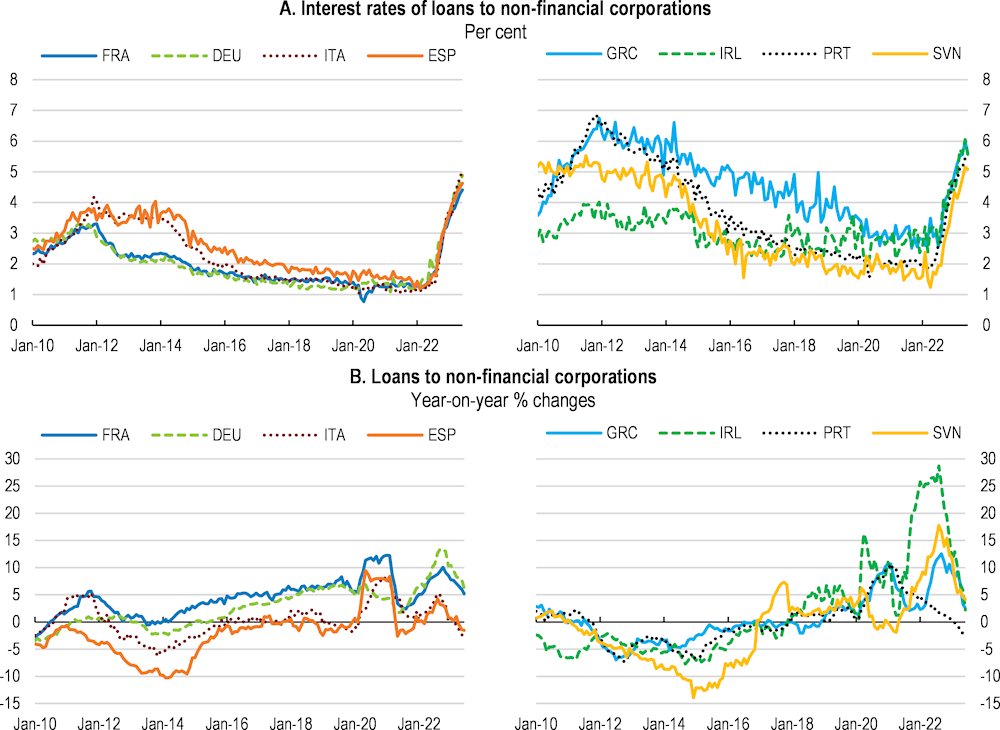

Increases in the prices of energy and food have been fuelling inflation. The negative terms-of-trade shock has exacerbated price pressures associated with post-pandemic fragmentation of global supply chains. To deliver on its mandate of price stability and to prevent inflation expectations from de-anchoring, the ECB has accelerated tightening monetary policy in July 2022, having put in place the Transmission Protection Instrument, raising policy interest rates by 400 basis points in less than eleven months. Nevertheless, the start of the tightening may have been too late (Darvas and Martins, 2022[2]). The corresponding increase in lending interest rates and tighter credit standards triggered a slowdown in credit provision to both firms and households, further weighing on the recovery and aggravating existing financial vulnerabilities (Figure 1.6).

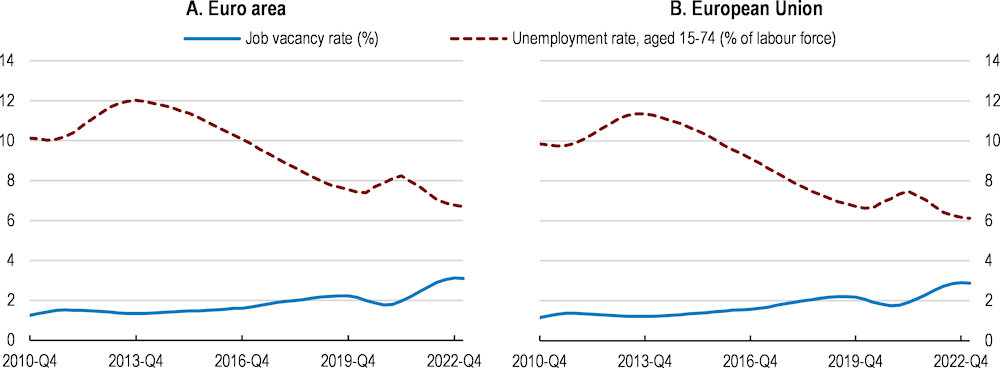

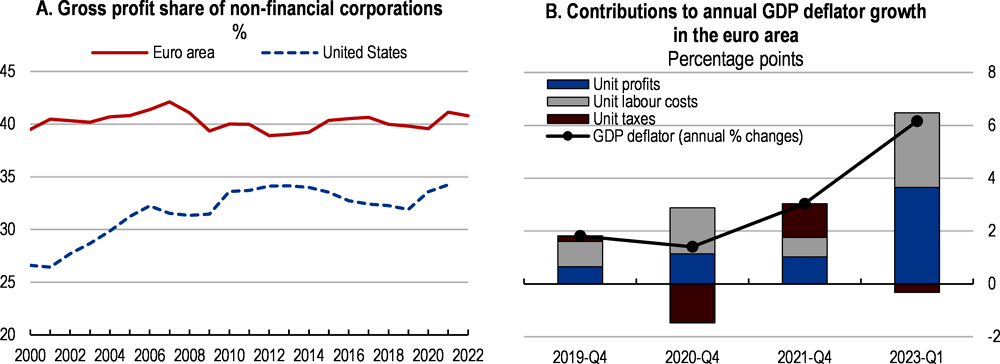

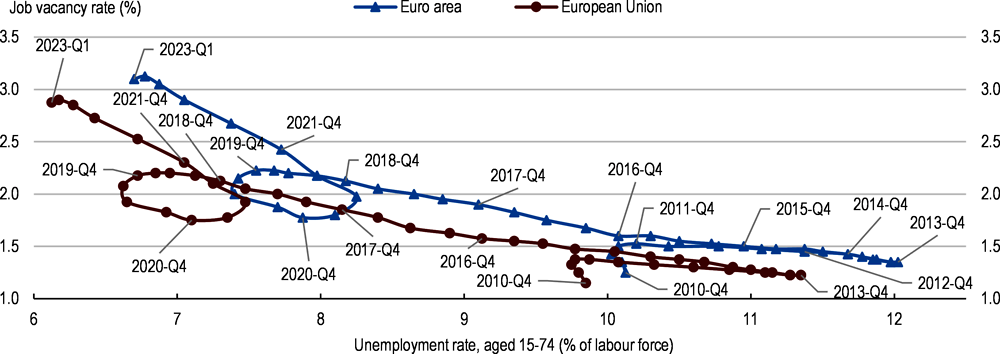

The labour market recovery continued in 2022 with employment exceeding the pre-pandemic level, but with considerable heterogeneity across sectors. Labour market slack decreased markedly in the information and communication technology sector and construction, while employment in manufacturing and some service sectors was still lower than before the pandemic. Labour market tightness is reflected in the unemployment rate, which is at historically low levels in both the EU and the euro area, while job vacancy rates are unprecedently high (Figure 1.7). Wage growth indicators picked up in the third and fourth quarter of 2022, recording the strongest increase, at an annual rate of 3.9%, in services. Labour market tightness is projected to continue, reflecting continuing labour shortages in many countries. Nominal wage growth is projected to accelerate as increased efforts to obtain compensation for recent inflation could lead to upward pressures in wage negotiations. Although wage shares and profit margins currently appear close to their historical averages, GDP deflator decomposition suggests increasing unit profits at the aggregate level (Figure 1.8). While a full recovery of the lost purchasing power could trigger de-anchoring of inflation expectations, increasing unit profits point to some room for non-inflationary wage increases.

Figure 1.6. Higher borrowing costs have reduced credit growth

Note: New business loans with an initial rate fixation period of less than one year. Loans other than revolving loans and overdrafts, convenience and extended credit card debt. In Panel A, loans of up to 1 year for Greece. In Panel B, loans adjusted for credit and securitisation.

Source: ECB MFI Interest Rate Statistics database.

Figure 1.7. The unemployment rate is historically low and job vacancies have increased

Note: Four quarter moving average rates. Data refers to the euro area including 20 countries and to the 27 EU Member countries.

Source: Eurostat Job Vacancy Statistics database; Eurostat Labour Market Statistics database; and OECD calculations.

Figure 1.8. Profit share remains close to the historical average, but unit profits are increasing

Note: In Panel A, the indicator is calculated as gross operating surplus and mixed income over gross value added for the non-financial corporate sector (S11). In both Panel A and Panel B, data refers to the euro area including 19 countries.

Source: Eurostat Non-financial Transactions database; Eurostat Labour Cost Index database; OECD Annual Sectoral Accounts database; Eurostat National Accounts database; OECD calculations.

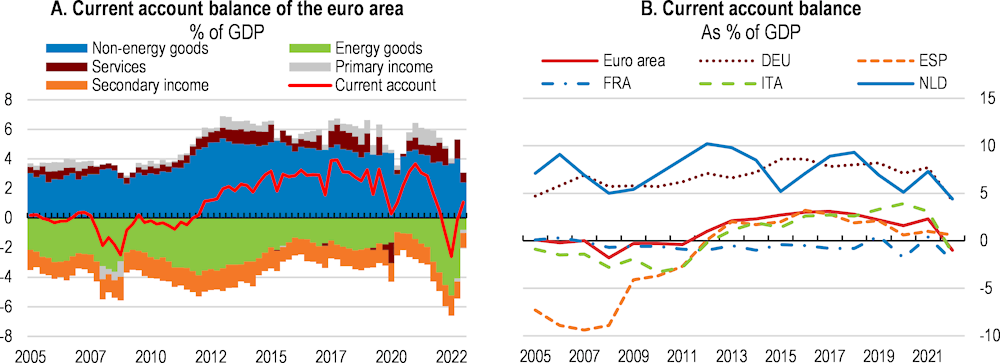

After a prolonged period of current account surpluses, the euro area’s current account balance has deteriorated sharply, mainly driven by expensive energy imports (Figure 1.9). At the same time, the strong variation in energy dependency together with varying energy needs led to discrepancies in current account dynamics, increasing risks of external imbalances in some countries (European Commission, 2022[3]).

Figure 1.9. The current account balance reflects expensive energy imports

Note: Data refers to the euro area including 20 countries as of 2013 and 19 countries from 2005 to 2012.

Source: Eurostat Balance of Payments database; Eurostat International Trade by SITC database; Eurostat National Accounts database; and OECD calculations.

A forceful policy response helped to reduce the fallout from the energy crisis

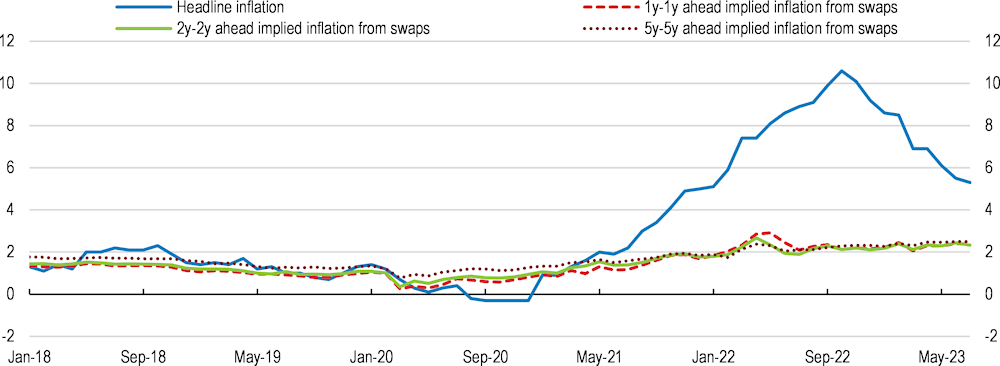

The energy crisis has abated in 2023 reflecting both stronger supply and lower-than-expected demand. European firms have been resilient during the energy price crisis. Many firms managed to reduce gas consumption significantly when elevated energy prices continued to incentivise fuel-switching and energy efficiency measures, while maintaining high levels of production. For example, in Germany where about 60% of industrial companies use natural gas, 75% of gas-dependent firms were able to reduce gas consumption without cutting production, while some 40% reported further room for consumption reduction (Pittel and Schultz, 2022[4]). Mild weather conditions also lowered heating requirements, ensuring inventory levels 20% above their long-term average at end-2022. As a result of these favourable developments, gas and oil prices have declined significantly (Figure 1.10). A continuing exclusion of gas imports from Russia also appears manageable, as the integration of European countries into the global liquified natural gas (LNG) market progresses (Albrizio et al., 2022[5]). Even in the absence of Russian gas, adherence to the voluntary 15% gas demand reduction plan would help fill up the storage capacities next winter.

Figure 1.10. Energy prices have been volatile

Energy prices in U.S. dollars

The adjustment during the energy crisis has been helped by tailored policy responses at EU level, including both measures to strengthen supply and reduce demand. In addition to the short-term measures focused on alleviating tensions in natural gas markets (Box 1.1), the Commission proposed measures concerning other sources of energy. These include the cap on extraordinary market revenues from electric power generation, a mandatory reduction target for peak hours demand and a one-off solidarity contribution from fossil fuel companies (European Commission, 2022[3]). As discussed in detail in Chapter 2, some of these measures cannot be sufficiently targeted or reduce incentives for energy savings and should not be introduced, at least not in their current proposed form.

The EU should refrain from overly generous price-capping mechanisms, which in any case should be carefully designed to minimise negative effects on energy savings. As discussed in Chapter 2, measures to mitigate the impact of high energy prices included a cap on wholesale gas prices at EU level. However, this mechanism suffers from several problems. It may imperil the functioning of the Internal Energy market and reduce gas imports into the EU. A price cap also contradicts the Emission Trading System, which aims at raising energy costs to incentivise investment in renewables. Importantly, price regulation cannot really be targeted and thus it risks reducing energy saving incentives, contradicting EU-wide efforts to improve energy efficiency.

Joint gas purchasing was proposed as a tool to leverage the EU’s purchasing power as a major gas importer and prevent companies and countries outbidding each other and thereby driving up gas prices. However, the proposed mechanism seems impractical and in need of improvement (Barnes, 2022[6]). Since the demand aggregation mechanism is mandatory up to the 15% of the gas storage facilities (see above), while participation in joint purchasing remains voluntary, it is not clear how much gas will be bought through the scheme. It is possible that it will not have much impact. The Commission estimates the maximum amount prescribed by demand aggregation at about 13.5 bcm (European Commission, 2022[7]), less than 4% of total EU annual gas consumption of more than 400 bcm. Moreover, the Title Transfer Facility (TTF) is a functioning wholesale market that already effectively represents the purchasing power of the EU. On the contrary, the Joint Purchasing IT Tool agreed in December 2022 seems to be duplicating the role of current LNG aggregators such as trading houses, oil and gas companies, as well as European utility companies that have signed long term LNG purchase contracts with producers. In addition, smaller buyers who are sometimes seen as beneficiaries of joint purchasing, can already access smaller-size contracts at the TTF and current market pricing with reference to TTF traded prices effectively provides demand aggregation. The new demand aggregation tool, however, requires a cumbersome assessment of potential negative effects of purchasing consortia on competition and places broad notification obligations on the gas sector, which may be unattractive for large companies (Hancher and Levitt, 2023[8]).

Box 1.1. EU measures to ease strains on natural gas markets

Alongside the longer-term structural measures in the Fit for 55 package and the REPowerEU plan (Chapter 2), additional short-term measures were introduced to make European gas markets more resilient:

Minimum gas storage obligations: Requirement to fill gas storage to 80% of capacity by November 2022 and to 90% ahead of all following winters. Several EU Member States adopted more stringent regulations, aiming for higher filling targets.

A regulation on coordinated demand reduction measures for gas: A voluntary reduction by 15% in gas demand between August 2022 and March 2024, compared to the average over the five previous years. The reduction target could become mandatory in case the EU initiates a crisis-level alert.

Energy diplomacy: the EU intensified its international outreach to strengthen energy partnerships with key natural gas and LNG suppliers, including Algeria, Azerbaijan, Norway and the United States.

Joint Gas Purchasing Mechanism: adopted in December 2022, it will facilitate the coordination of gas purchases at the EU level using a two-step process (Regulation 2022/2576). The first step requires demand aggregation with volumes equivalent to 15% of the gas needed to fill a country’s storage facilities to 90% of capacity and the second involves voluntary participation in joint purchasing.

Enhanced solidarity: in December 2022 the EU Council adopted new rules for sharing natural gas amongst EU countries in case of an emergency. These rules will be triggered only if member states have not concluded bilateral agreements setting the modalities of solidarity.

New floating storage regasification units and the expansion of existing regasification terminals will provide the EU with 25% more regasification capacity in 2023 compared to 2021. This represents an increase of around 40 bcm annually.

Market correction mechanism (a wholesale gas price cap): EU energy Ministers reached a political agreement on the rules for a temporary one-year mechanism starting on 15 February 2023. The instrument imposes a safety price ceiling on the month-ahead Title Transfer Facility (TTF) derivatives and will be automatically activated if the month-ahead TTF price exceeds €180/MWh for three working days or if the TTF price is €35 higher than a reference price for LNG and non-LNG contracts on global markets for the same three working days. The Agency for Cooperation of Energy Regulators (ACER) was entrusted with monitoring and publishing these market corrections.

Source: International Energy Agency (2023[9]).

Growth will slow down in 2023, gradually picking up in 2024

Growth in the euro area is projected to slow to 0.9% in 2023, despite the support that robust labour markets and declining headline inflation will provide to real incomes and private consumption, before gradually strengthening in 2024. The benefits of lower energy prices and declining inflation are projected to help the growth momentum to gradually pick up, bringing average annual growth in 2024 to 1.5% (Table 1.1). Growth in the European Union will follow a similar profile and rebound in 2024 to 1.5% year-on-year on the back of stronger private consumption (Table 1.2).

Headline consumer price inflation is projected to moderate, while core inflation will remain sticky. With the sharp rises of energy prices in 2022 still working their way through the economy and with monetary policy tightening having begun later than in the United States, both headline and core inflation are projected to remain above target in the euro area for longer. Annual headline inflation in the euro area is projected to come down from 8.3% in 2022 to 5.8% in 2023 and remain above 3% in 2024. Core inflation in the euro area, which kept increasing throughout 2022, is projected to decrease to 5.4% in 2023, before easing further to 3.6% in 2024.

Table 1.1. Macroeconomic indicators and projections for the euro area

|

|

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023¹ |

2024¹ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Current prices (EUR Billions) |

Annual percentage change, volume (2015 prices) |

||||

|

Gross domestic product (GDP) |

11956.4 |

-6.2 |

5.5 |

3.5 |

0.9 |

1.5 |

|

Private consumption |

6363.3 |

-7.8 |

3.7 |

4.4 |

0.2 |

1.5 |

|

Government consumption |

2450.2 |

0.9 |

4.4 |

1.3 |

-0.2 |

0.9 |

|

Gross fixed capital formation |

2653.4 |

-6.2 |

3.6 |

3.7 |

0.6 |

1.4 |

|

Housing |

631.3 |

-3.3 |

7.8 |

1.4 |

. . |

. . |

|

Final domestic demand |

11466.9 |

-5.6 |

3.8 |

3.5 |

0.2 |

1.4 |

|

Stockbuilding² |

. . |

-0.3 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

-0.1 |

0.0 |

|

Total domestic demand |

11551.1 |

-5.8 |

4.1 |

3.8 |

0.0 |

1.4 |

|

Exports of goods and services |

5738.4 |

-9.4 |

11.1 |

7.3 |

2.1 |

2.9 |

|

Imports of goods and services |

5333.0 |

-8.8 |

8.8 |

8.3 |

0.8 |

2.7 |

|

Net exports² |

405.4 |

-0.6 |

1.4 |

-0.2 |

0.7 |

0.2 |

|

Memorandum items |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Potential GDP |

1.6 |

1.6 |

1.4 |

1.2 |

1.1 |

|

|

Output gap (% of potential GDP) |

-6.4 |

-3.0 |

-1.0 |

-1.3 |

-1.0 |

|

|

Employment |

-1.5 |

1.5 |

2.8 |

1.1 |

0.5 |

|

|

Unemployment rate (% of labour force) |

7.9 |

7.7 |

6.7 |

6.7 |

6.6 |

|

|

GDP deflator |

1.9 |

2.1 |

4.6 |

5.7 |

3.0 |

|

|

Harmonised index of consumer prices |

0.3 |

2.5 |

8.3 |

5.8 |

3.2 |

|

|

Harmonised index of core inflation³ |

0.7 |

1.5 |

4.0 |

5.4 |

3.6 |

|

|

Household saving ratio, net (% of household disposable income) |

13.6 |

11.5 |

7.7¹ |

7.4 |

6.7 |

|

|

Current account balance (% of GDP) |

2.6 |

4.2 |

1.2 |

2.4 |

2.6 |

|

|

General government fiscal balance (% of GDP) |

-7.1 |

-5.3 |

-3.7 |

-2.9 |

-2.2 |

|

|

Underlying general government fiscal balance (% of potential GDP) |

-2.9 |

-3.5 |

-3.0 |

-2.4 |

-2.1 |

|

|

Underlying government primary fiscal balance (% of potential GDP) |

-1.7 |

-2.3 |

-1.5 |

-1.0 |

-0.5 |

|

|

General government debt, Maastricht definition (% of GDP) |

99.3 |

97.3 |

93.2 |

92.3 |

92.0 |

|

|

General government net debt (% of GDP) |

75.9 |

70.8 |

57.0 |

56.4 |

56.2 |

|

|

Three-month money market rate, average |

-0.4 |

-0.5 |

0.3 |

3.2 |

3.4 |

|

|

Ten-year government bond yield, average |

0.0 |

0.0 |

1.8 |

3.3 |

3.7 |

|

Note: Data refers to euro area member countries that are also members of the OECD (17 countries).

1. OECD estimates.

2. Contribution to changes in real GDP.

3. Index of consumer prices excluding food, energy, alcohol and tobacco.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook 113 database.

Risks to projections are tilted to the downside (Table 1.3). The disruption from the Russian invasion of Ukraine is likely to continue to weigh on global output through the impact on uncertainty, continuing risks to food and energy security, and the ongoing adjustments in commodity markets as price caps and embargos on Russian energy take full effect. The risk of critical energy shortages in the 2023-24 winter has diminished but not disappeared. Supply from Russia in 2023 is likely to be minimal, in contrast to the early months of 2022, and the likely rebound in demand in China will increase competition for tight global LNG supply. This could push energy prices up again, resulting in another spike in consumer prices and further economic dislocation. Risks of higher prices also remain in oil markets, given recent production cuts by oil exporters and considerable uncertainty as to how Western sanctions on oil and oil products from Russia will affect global supply.

Table 1.2. Macroeconomic indicators and projections for the European Union

|

|

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023¹ |

2024¹ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Current prices (EUR billions) |

Annual percentage change, volume (2015 prices) |

||||

|

Gross domestic product (GDP) |

17856.4 |

-5.9 |

5.6 |

3.6 |

0.9 |

1.5 |

|

Private consumption |

9501.4 |

-7.2 |

4.1 |

4.1 |

-0.1 |

1.6 |

|

Government consumption |

3645.8 |

1.0 |

4.2 |

1.0 |

-0.2 |

1.1 |

|

Gross fixed capital formation |

3944.3 |

-5.5 |

3.9 |

3.9 |

0.6 |

1.4 |

|

Final domestic demand |

17090.1 |

-5.1 |

4.1 |

3.3 |

0.1 |

1.4 |

|

Stockbuilding² |

. . |

-0.4 |

0.7 |

0.5 |

. . |

. . |

|

Total domestic demand |

17225.7 |

-5.4 |

4.8 |

3.8 |

-0.1 |

1.4 |

|

Exports of goods and services |

8872.3 |

-8.8 |

11.0 |

7.5 |

2.4 |

3.0 |

|

Imports of goods and services |

8243.5 |

-8.2 |

9.9 |

8.2 |

0.9 |

2.7 |

|

Net exports² |

. . |

-0.6 |

0.9 |

0.0 |

. . |

. . |

|

Memorandum items |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Potential GDP |

1.7 |

1.7 |

1.6 |

1.4 |

1.3 |

|

|

Output gap (% of potential GDP) |

-6.0 |

-2.6 |

-0.6 |

-1.2 |

-0.9 |

|

|

Employment |

-1.3 |

1.5 |

2.4 |

0.8 |

0.4 |

|

|

Unemployment rate (% of labour force) |

7.3 |

7.1 |

6.2 |

6.3 |

6.2 |

|

|

GDP deflator |

2.2 |

2.5 |

5.4 |

6.2 |

3.2 |

|

|

Harmonised index of consumer prices |

0.6 |

2.8 |

9.1 |

6.7 |

3.4 |

|

|

Harmonised index of core inflation³ |

1.0 |

1.7 |

4.7 |

6.0 |

3.7 |

|

|

Household saving ratio, net (% of household disposable income) |

13.0 |

10.6 |

7.1¹ |

6.9 |

6.3 |

|

|

Current account balance (% of GDP) |

2.8 |

4.0 |

1.2 |

2.4 |

2.6 |

|

|

General government fiscal balance (% of GDP) |

-6.9 |

-4.9 |

-3.5 |

-2.9 |

-2.3 |

|

|

Underlying general government fiscal balance (% of potential GDP) |

-2.9 |

-3.3 |

-3.1 |

-2.6 |

-2.2 |

|

|

Underlying government primary fiscal balance (% of potential GDP) |

-1.7 |

-2.1 |

-1.6 |

-1.1 |

-0.6 |

|

|

General government debt, Maastricht definition (% of GDP) |

93.5 |

91.3 |

87.4 |

86.9 |

86.7 |

|

|

General government net debt (% of GDP) |

69.5 |

64.3 |

52.0 |

51.8 |

51.7 |

|

|

Three-month money market rate, average |

-0.3 |

-0.4 |

1.0 |

3.8 |

3.9 |

|

Note: Data refers to European Union member countries that are also members of the OECD (22 countries).

1. OECD estimates.

2. Contribution to changes in real GDP.

3. Index of consumer prices excluding food, energy, alcohol and tobacco.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook 113 database.

Trade-related tensions remain a concern. The standoff between the United States and China goes on and the cumulative coverage of goods-related import restrictions imposed by G20 countries has increased, including new export restrictions on food, animal feed and fertilisers. Medium-term risks to growth and inflation related to the ongoing fragmentation of global value chains are also rising.

The scale and duration of the monetary tightening required to durably lower inflation is uncertain. Continued cost pressures or an upward drift in inflation expectations could require the ECB to keep policy rates higher for longer, further dampening growth and potentially exposing financial sector vulnerabilities. Potential losses at banks or non-bank financial institutions from loan defaults or residential and commercial real estate exposures could intensify the drag on economic activity. On the upside, a durable and timely conclusion of the war in Ukraine could alleviate upward pressure on energy and food prices. A stronger recovery in China could also add to external demand.

Table 1.3. Events that could lead to a major deterioration in the outlook

|

Vulnerability |

Possible outcomes |

|---|---|

|

The energy crisis may be rekindled by higher demand for LNG from China or unintended effects on global supply of Western sanctions on Russian oil. |

A new energy price shock could lead to another spike in consumer prices, necessitating additional monetary policy tightening and dampening growth. |

|

Trade tensions may deteriorate further, extending the scope of export restrictions. |

Further fragmentation of global supply chains and barriers to trade would weigh on growth and contribute to inflationary pressures. |

|

Interest rates may need to be higher for longer to durably reduce inflation. |

Bank and non-bank losses from defaulting loans and real estate exposures could necessitate write-offs, further limiting lending, dampening growth and exposing existing financial sector vulnerabilities. |

Monetary policy is broadly appropriate but financial risks are increasing

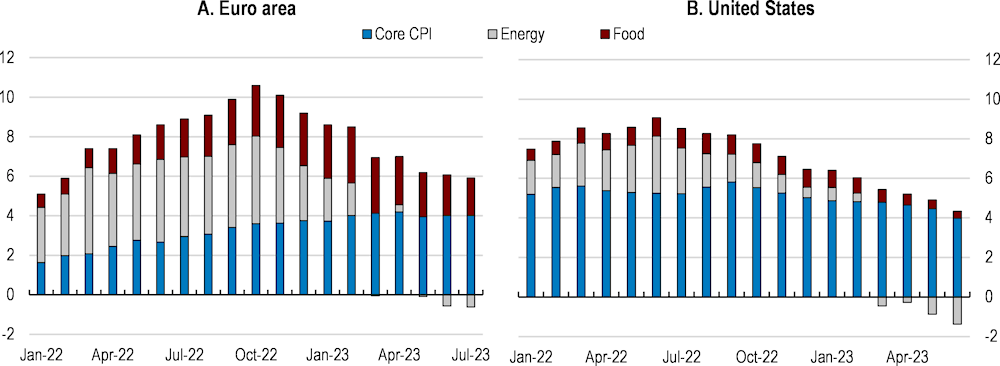

Headline inflation in the euro area remains to a large extent driven by supply-side factors (Figure 1.11). Despite lower-than-expected energy inflation at the end of 2022, food and energy prices remain the largest contributors to euro area headline inflation. At the same time, core inflation has continued to increase. The share of core items registering monthly inflation rates above their typical monthly patterns increased in December to well above 80%, the highest level in 2022 (European Commission, 2023[10]). However, interpreting the increase in inflation as demand-driven or supply-driven is not straightforward and the price changes in most cases reflect a mix of both factors, at least in OECD economies (Barnard and Koh, 2023[11]). The ECB also finds that the initial surge in core inflation in the euro area was mainly supply-driven but that supply and demand factors have played broadly similar roles in recent months (Gonçalves and Koester, 2022[12]).

Figure 1.11. Headline inflation mainly reflects a negative terms-of-trade shock from energy and food

Contributions to annual inflation growth, percentage points

Note: Food includes non-alcoholic beverages. Euro area includes 19 countries.

Source: OECD Price Statistics database; and Eurostat.

The ECB should continue its data-dependent approach to policy

Beyond the demand-driven part of the inflation spike, the standard monetary policy prescription is to “look through” supply shocks that are not assessed to leave a lasting effect on potential output (Bodenstein, Erceg and Guerrieri, 2008[13]). However, negative supply shocks from high energy prices and the war may turn out to be persistent or even permanent, durably reducing potential output. In such a situation, monetary policy tightening is necessary to align demand with permanently lower productive capacity. In addition, and notwithstanding the implications for potential output, monetary policy should react strongly if supply shocks risk de-anchoring inflation expectations (Brainard, 2022[14]). While simple in theory, this policy is difficult to implement, due to the challenges of assessing potential output in real time – even more so when uncertainty is high and more muted policy reaction may be warranted (Orphanides, 2003[15]).

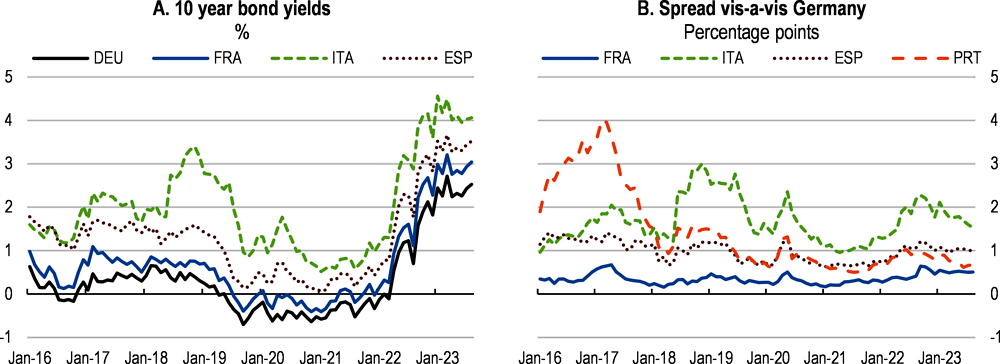

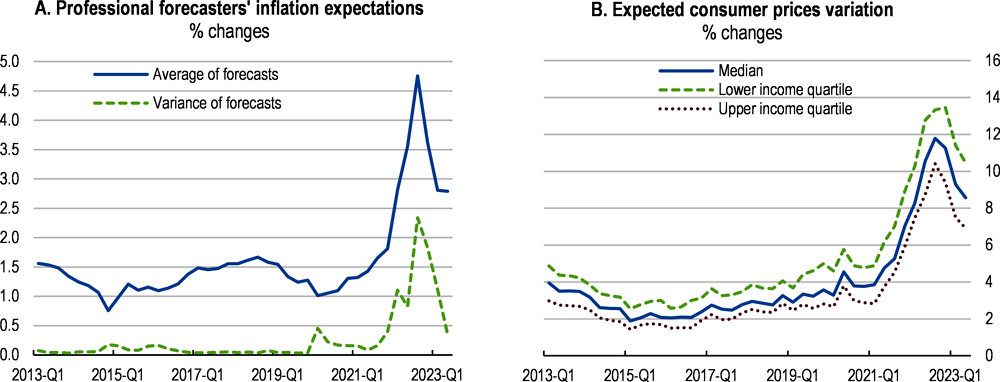

In the current situation, the need to anchor inflation expectations may be stronger than the considerations regarding the negative effects on output. When inflation is already high, prolonging the period of high inflation increases the risk that inflation expectations adjust upward, putting medium-term price stability at risk (Schnabel, 2022[16]). Although market-based measures suggest that inflation expectations remain anchored, they appear to be pointing to a prolonged period of above-target inflation (Figure 1.12). Survey-based measures of short-term inflation expectations paint a similarly concerning picture. Inflation expectations of households in the euro area have been trending upwards for several quarters and surveys among professional forecasters remain similarly elevated (Figure 1.13).

Figure 1.12. Market-based inflation expectations appear above the 2% target

Headline inflation and inflation expectations from swaps, 12-month % change

Second-round inflation effects must be minimised, as they could prolong the costly period of disinflation and potentially trigger a wage-price spiral. Judging from the past, the risks appear limited. The comparison of 22 historical episodes similar to the current situation, characterised by rising inflation, positive nominal wage growth, declining real wages, and declining unemployment, shows that wage-price spirals did not take hold on average (IMF, 2022[17]). Instead, inflation edged down and the unemployment rate stabilised following such episodes, mostly driven by monetary policy tightening, which helped to keep inflation contained. The post-COVID-19 episode also provides only limited evidence that most advanced economies may be entering a wage-price spiral, while profit margins may have increased in some sectors. The correlation between wage growth and inflation has declined over recent decades and other institutional factors, such as the high degree of firms’ pricing power, declining collective bargaining power and falling trade union membership seem to be limiting the risk of a wage-price spiral developing (Boissay et al., 2022[18]).

Figure 1.13. Survey-based short-term inflation expectations have also increased

Note: Data refer to the euro area aggregate. In Panel A, data are based on the ECB Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF) and refer to the inflation expectations for the next 12 months. In Panel B, data refer to the responses to the question "By how many per cent do you expect consumer prices to go up/down in the next 12 months?" contained in the European Commission Consumer opinion survey.

Source: ECB Survey of Professional Forecasters; European Commission, Business and consumer surveys, https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/economic-forecast-and-surveys/business-and-consumer-surveys_en ; and OECD calculations

However, important caveats point to the need for continued vigilance. Data patterns from the past may not be representative of current circumstances, especially if the COVID-19 shock caused a large structural break. Differences across economies and over time in structural factors, such as union density, coverage and centralisation of wage bargaining may affect wage-setting processes. Policymakers may need to respond aggressively to supply-side shocks, especially when inflation is high and rising (IMF, 2022[17]). The risk of a wage-price spiral also depends on how firms and workers form their expectations for wages and prices. More adaptive and backward-looking expectations will require stronger monetary policy responses to reduce the risks of de-anchoring. Finally, the flat profile of nominal wages in the wake of an inflationary shock cannot be taken for granted. Wage pressures are rising in euro area more broadly, especially in countries with persistent shortages of labour (for example in Germany) or semi-automatic wage indexation (as in Belgium, Luxembourg). The impact of high inflation has been discernible in the latest wage agreements in Germany (Deutsche Bundesbank, 2023[19]) or has been projected to translate into hourly labour cost growth in the private sector of 8.5% p.a. in 2023 in Belgium (NBB, 2022[20]).

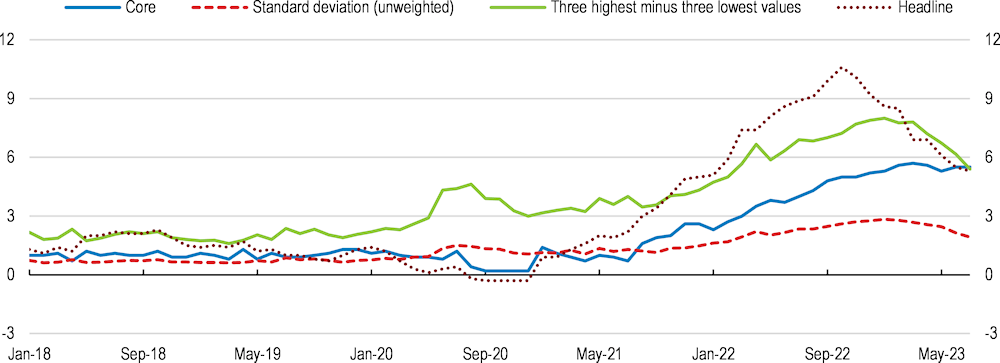

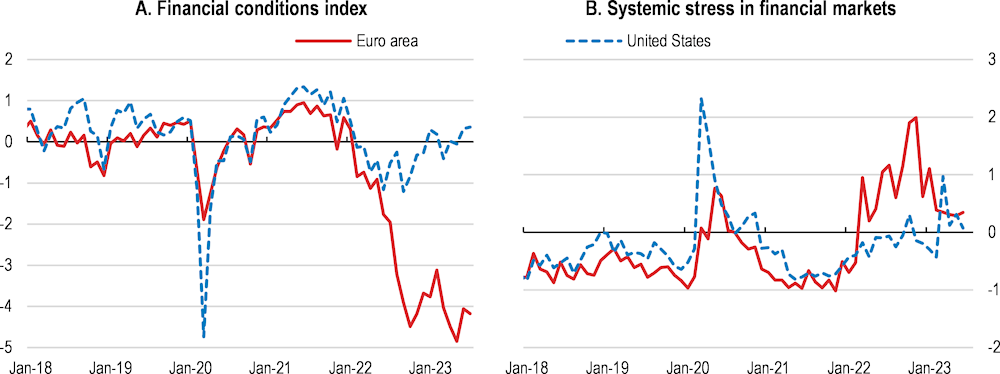

Although risks around the growth outlook have become more balanced, risks to inflation remain skewed to the upside. While headline inflation has peaked, core inflation in the euro area is still trending upward and becoming more dispersed (Figure 1.14). Core inflation appears sticky despite a swift and considerable tightening of financial conditions suggesting that changes in policy rates in the euro area are being quickly reflected in credit conditions and yields on market-based debt (Figure 1.15). The stickiness of core inflation may reflect expectations of a shallow economic slowdown partly driven by decreasing energy prices following the successful replacement of energy imports from Russia.

Moreover, bringing inflation under control may involve output losses. Looking at the historical record, there seems to be no post-1950 precedent for a sizeable disinflation induced by the central bank in the United States, Canada, Germany or the United Kingdom that does not entail substantial economic sacrifice or a recession (Cecchetti et al., 2023[21]). Analysis of the sacrifice ratios – the increases in slack associated with reductions in inflation – during large disinflationary episodes in the United States and other major economies seems to suggest that disinflation is always accompanied by a recession, although the costs of disinflation can differ markedly across episodes. Disinflation is further complicated by the strong labour market with record-low unemployment rate and historically high job vacancy rate (Figure 1.16). This situation suggests strong aggregate activity, at least given the current state of supply-side constraints, as well as difficult labour market matching, due to both higher reallocation needs and a lower matching efficiency. Given that structural factors, such as labour reallocation and matching efficiency, cannot be influenced by monetary policy, the decrease in inflation seems unlikely without a corresponding increase in the unemployment rate in the short run (Blanchard, Domash and Summers, 2022[22]). At the same time, the Beveridge curve dynamics in the EU may be more benign, reflecting the widespread use of job-retention schemes during the pandemic (Lam and Solovyeva, 2023[23]).

Figure 1.14. Headline inflation has peaked but core inflation continues to trend upwards

Consumer price inflation, 12-month % change.

Note: Data refer to the euro area including 19 countries. Core inflation excludes volatile energy, food, alcohol and tobacco prices.

Source: Eurostat Harmonised index of consumer prices (HICP) database; and OECD calculations

Figure 1.15. Financial conditions in the euro area have tightened considerably

Note: The Bloomberg Financial Conditions Index (FCI) is an equally weighted sum of sub-indexes that track financial stress in money, bond and equity markets. The index assesses both the availability of financing and its cost. The FCI is standardised to show the number of standard deviations above or below its average value from 1994 (for the US) and 1999 (for the euro area) to mid-2008 (the Z-score). Hence, a positive (negative) value indicates expansionary (restrictive) financial conditions compared to the level prior to the Global Financial Crisis. Data are shown up to July 2023.

Financial markets stress for the euro area is the ECB composite indicator of systemic stress combining 15 mainly market-based financial stress measures. For the US, it is the Kansas City Financial Stress Index based on 11 financial market variables. The indicators are standardised to show the number of standard deviations above or below their average value over the period 2007-2023. A positive (negative) value indicates high (low) systemic stress in the financial markets. Data are shown up to June 2023.

Source: Bloomberg; Refinitiv; and OECD calculations.

Figure 1.16. The high number of vacancies suggests costly disinflation

Note: Four quarter moving average rates. Data refers to the euro area including 20 countries and to the 27 EU Member countries.

Source: Eurostat Job Vacancy Statistics database; Eurostat Labour Market Statistics database; and OECD calculations.

The ECB should stay determined to bring inflation back to target in a timely manner to prevent current high inflation from becoming entrenched in expectations. This requires clearly communicating the risks that inflationary pressures may be more persistent than expected and that a restrictive monetary policy stance will continue until there evidence of a sustained decline in inflation. The ECB needs to keep raising interest rates for as long as needed to put inflation back on a sustainable path towards the 2% target, which implies tightening monetary policy by more if fiscal policy stays overly accommodative. Determined policy action by the ECB has already led to a considerable tightening of the policy interest rates, which is projected to continue. The restrictive monetary policy stance is welcome. Given the high degree of uncertainty about the speed at which higher interest rates take effect and the potential spillovers from policy in other countries, a carefully calibrated approach based on incoming data is appropriate.

Inflation has distributional implications, but they are beyond the ECB’s mandate

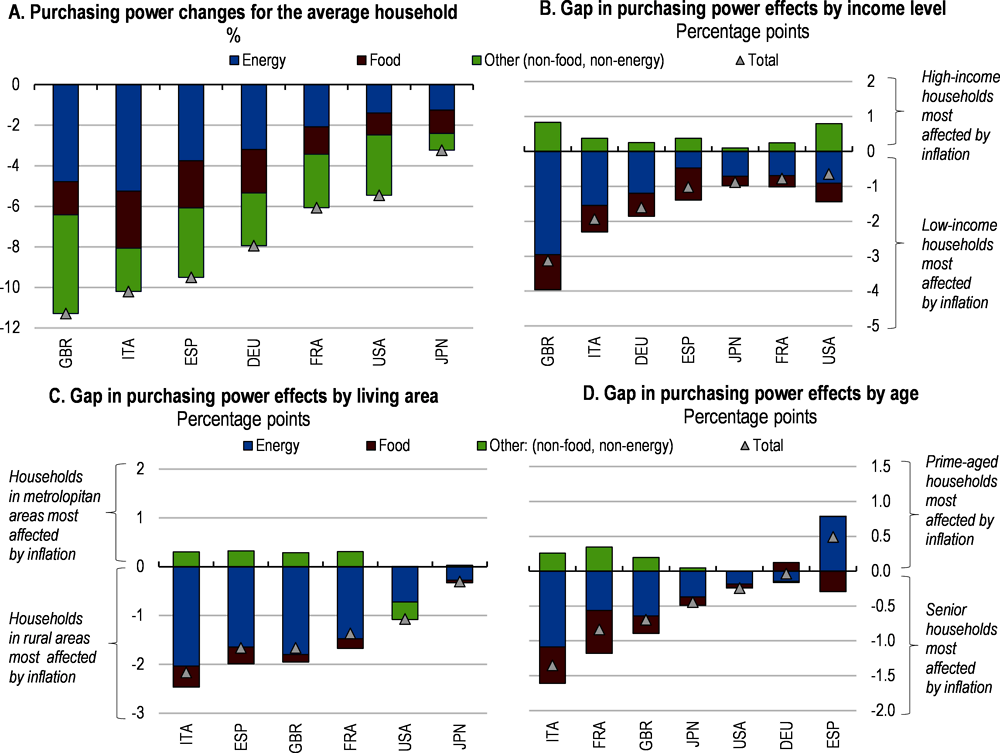

The effects of high inflation are more pronounced for low-income households. The global negative price shock following the Russian aggression against Ukraine had heterogenous inflationary effects across countries and households. The effects across countries depended on the role of Russian energy imports in overall energy needs and availability of alternative energy sources. The effects across households varied due to differences in consumption shares between low-income and high-income households, differences in the goods and services within each consumption category and differences in the ability to buffer cost-of-living increases through savings or borrowing (Causa et al., 2022[24])

The difference between the inflation rate in the lowest and highest income quintiles has been negligible between 2011 and 2021, but it increased sharply from 0.1 percentage points in September 2021 to 1.9 percentage points in September 2022 (Osbat et al., 2022[25]). The effect on the purchasing power of the average household has been mainly driven by energy and food prices (Figure 1.17, Panel A). Low-income and rural households, and the elderly were generally more exposed to the price shock than the average household, although purchasing power losses of these groups are heterogenous across countries (Figure 1.17, Panels B, C, D). Living on low income is often not the most important vulnerability compared to living in a small, isolated village and being elderly, which are both major vulnerability factors. Differences in energy spending are indeed more pronounced across place of residence than across households’ incomes. At the same time, differences in energy spending do not systematically vary with age in all countries. For example, in Spain the elderly are less affected by energy prices than prime-aged persons.

Figure 1.17. Distributional effects of inflation are highest for low-income, rural, and senior households

Note: Data show the average household's decline in purchasing power following changes in consumer prices between August 2021 and August 2022. In Panels C and D, data show the gap in purchasing power (following changes in consumer prices) between two household types, namely low- relative to high-income, living in rural relative to living in metropolitan areas, and senior relative to prime-aged, respectively.

Source: (Causa et al., 2022[24])

Since only governments have the mandate and tools to address distributional issues (Schnabel, 2022[16]), central bank policy cannot substitute for effective social security and other fiscal assistance. Including inequality as a specific mandate could also threaten central bank’s independence. Hence, the ECB should continue focussing on its primary objective of maintaining price stability, and, without prejudice to that objective, on other objectives laid out in the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU.

One such example is the ECB’s role in supporting the green transition. Climate change mitigation requires mainly policies by governments. However, as far as the primary mandate of price stability allows, the ECB is contributing to this effort by incorporating climate change considerations into its monetary policy framework (Box 1.2). This effort for incorporating climate change is an ongoing project and may require adjustments as monetary policy changes. For example, the ECB implements the changes to its corporate bond portfolio through adjustments to reinvestments of maturing securities. The ongoing reduction in reinvestments will constrain the ECB’s ability to decarbonise its corporate bond portfolio and may have to be replaced by another policy, possibly based on the stock-based approach. Similarly, the measures limiting the share of marketable assets issued by entities with a high carbon footprint that can be pledged as collateral are expected to have initially only a small impact on ECB counterparties (Schnabel, 2023[26]).

Box 1.2. Greening the ECB’s monetary policy operations

The measures incorporating climate change into ECB monetary policy operations follow the ECB’s climate action plan and include rules for corporate bond purchases, collateral framework, disclosure requirements and risk management. Their aim is to reduce climate-related financial risks on the Eurosystem’s balance sheet, encourage transparency and assist in the transition to a greener economy. They are implemented without prejudice to the ECB's primary objective of price stability. In particular, the following measures have been adopted:

Corporate bond holdings: in October 2022, the ECB started gradually decarbonising its corporate bond holdings by tilting them towards issuers with lower greenhouse gas emissions, more ambitious carbon reduction targets and better climate-related disclosures. Tilting is to be implemented through the reinvestment of the sizeable redemptions expected over the coming years. At the same time, the volume of corporate bond purchases will continue to be determined solely by monetary policy considerations.

Collateral framework: before the end of 2024, the ECB plans to limit the share of assets issued by issuers with a high carbon footprint that can be pledged as collateral when borrowing from the ECB. This measure, at first applying only to marketable debt instruments of non-financial corporations, will reduce climate-related risks in Eurosystem credit operations. Additionally, the ECB has started in 2022 to consider climate change risks when reviewing haircuts – reductions to the value of collateral reflecting its riskiness – applied to corporate bonds.

Climate-related disclosure requirements for collateral: depending on the implementation date of the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), probably from 2026, the ECB will only accept marketable assets and credit claims from companies and debtors that meet the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). This will help improve disclosure and generate better data for financial institutions, investors and civil society. Since a significant fraction of the assets that can be pledged as collateral, such as asset-backed securities and covered bonds, do not fall under the CSRD, the ECB will continue to encourage further disclosures of climate-related data.

Risk assessment and risk management: the ECB will continue to improve its risk assessment tools and capabilities related to climate-related risks. By the end of 2024, the Eurosystem will also start using common minimum standards for national central banks’ assessment of climate-related risks for credit rating purposes.

Statistics on climate-related risks and green finance: to improve awareness regarding the climate-related risks in the financial sector and better monitor developments in green finance, the ECB in January 2023 published a first set of climate-related statistical indicators, covering indicators on sustainable finance, carbon emissions and physical risks.

The effect of these policy announcements and actions can already be seen in the bond markets. For example, following the announcement of the ECB’s climate action plan at the end of the 2021 Monetary Policy Strategy Review, yields-to-maturity of green bonds eligible for ECB operations decreased compared to equivalent conventional bonds. Furthermore, green bond issuance by firms incorporated in the euro area increased.

Source: ECB (2022[27]); Eliet-Doilet and Maino (2022[28]).

Unconventional policies should be gradually withdrawn

Following the increases in policy interest rate, which remains the key instrument for setting the monetary policy stance, the ECB has also started a gradual and predictable reduction of its monetary policy bond portfolio. The pace of reduction amounts to EUR 15 billion per month on average from March to June 2023, followed by discontinuation of reinvestments under the ECB’s Asset Purchase Programme from July 2023. At the same time, the ECB’s flexibility built into the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme, the Transmission Protection Instrument and the Outright Monetary Transactions, allow swift responses to potential fragmentation in financial markets that would hamper monetary policy transmission.

However, the withdrawal of the monetary stimulus provided by the ECB’s large-scale asset purchases may entail some risks. Looking at the experience with the Fed’s reversal of asset purchases since 2017, there seems to be no matching decrease in the balance sheet of commercial banks, including reductions in bank deposits and outstanding credit lines to corporations. This could make the financial sector more sensitive to potential liquidity shocks and necessitate further liquidity provision by the central bank, as happened in the United States during the repo spike episode in September 2019 and the dash for cash in March 2020 (Acharya et al., 2022[29]).

Banks’ asymmetric responses to the provision and withdrawal of monetary stimulus need to be closely monitored and managed. There are different reasons why banks may react differently to quantitative easing, which seems to expand claims on liquidity, and quantitative tightening, which does not appear to reduce these claims. One possibility is that quantitative easing, unlike quantitative tightening, had both market liquidity effects and additional effects from signalling the easier monetary policy stance when rates were at the effective lower bound. Another is moral hazard, as banks rely on the central bank to repeat its past interventions when market liquidity seizes up, or an unintended effect of regulation, where new rules could have succeeded in making banks hold reserves but made it cheaper to finance reserves with new claims on liquidity, such as credit lines (Acharya et al., 2022[29]). The discrepancy between aggregate claims on liquidity and aggregate reserves needs to be monitored and, if excessive, its levels should be managed counter-cyclically.

The appropriate speed of the ECB’s quantitative tightening and the modalities, under which the unconventional measures are withdrawn, remains uncertain. It is possible that quantitative tightening is progressing too slowly. Relying on short-term rate increases without quickly reducing central bank balance sheets is likely to increase the interest rate exposure of the central bank, leading to losses on existing positions. Without the demand-reducing effects of balance sheet reduction, it is also possible that short-term interest rates will have to rise higher than would otherwise be needed (Turner, 2022[30]). To reduce uncertainty and limit interest rate increases, the ECB could provide a quantified medium-term strategy of asset sales together with a contingency plan for responding to large or disruptive movements in market rates. The existing instruments, such as the Transmission Protection Instrument, which aims at preventing unwarranted financial market dynamics threatening monetary policy transmission, could be complemented by contingency plans for dealing with other possible shocks.

Higher interest rates are beginning to weigh on the economy

Higher policy interest rates have triggered repricing across asset classes and generated sizeable unrealised losses on the bond portfolios held by financial institutions. Although banks tend to benefit from higher interest rates on aggregate, as profitability increases, this may not be the case for all banks. Strains from tighter monetary policy have appeared in parts of the banking sector and could intensify as monetary policy continues to tighten, especially among nonbank financial intermediaries, such as pension funds and insurers (Garcia Pascual, Natalucci and Piontek, 2023[31]). Bank lending has moderated across euro area countries, reflecting decreases in both supply and demand. On the supply side, euro area banks made sizeable voluntary repayments of loans from Targeted Longer-Term Refinancing Operations (TLTRO) between November 2022 and February 2023. In addition, tighter credit standards reflect higher risk perception and declining risk tolerance of banks. Loan demand by firms has decreased due to weakening fixed investment, while falling strongly for households across euro area countries. Weak loan demand of households reflects higher lending rates as well as lower consumer confidence and deteriorating prospects in the housing market (ECB, 2023[32]).

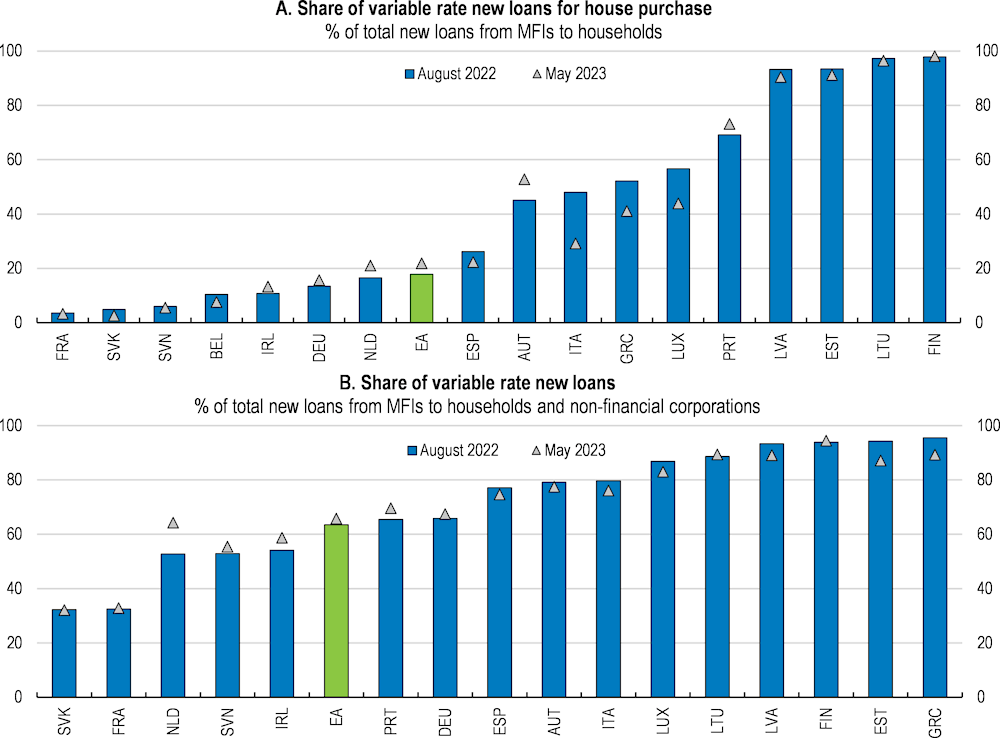

Rising interest rates on mortgages amplify the financial vulnerability of households, especially in countries with a high level of private debt and high shares of variable rate mortgages. Bank lending rates for household mortgages similarly continued to rise, reaching more than 3% per annum in January 2023, up from 1.33% the year before, while consumers expect them to increase further over the next 12 months. Higher rates on new mortgages and declining real incomes have led to a sharp fall in the demand for mortgages. The impact of higher interest rates on the housing sector is still building up and will continue to weigh on growth. The drag on growth will come through negative effects on residential investment, especially in countries with a high share of variable rate loans, and on consumption, by reducing disposable income and housing wealth. These developments in the residential housing sector pose financial stability risks, too. While the share of homeowners with a mortgage is relatively low in large euro area countries, the share of variable rate mortgages has recently increased (Figure 1.18, panel A). The increased share of variable rate mortgages points to growing exposure of euro area households to rising interest rates (Figure 1.18, panel B).

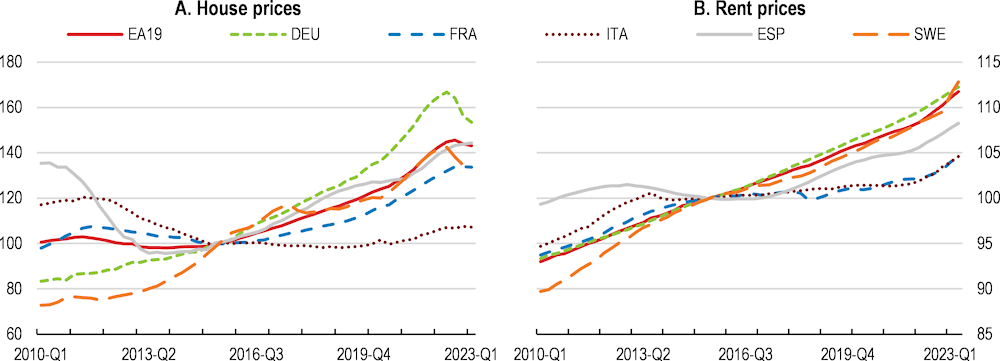

House prices in the EU have been resilient in the first half of 2022 but started to decline in most EU countries in the last quarter of 2022. Since the trough in 2013, house prices have been increasing steadily and the COVID-19 pandemic further accelerated this trend (Figure 1.19, panel A). In many countries, house prices decoupled strongly from rental prices (Figure 1.19, panel B). The Commission’s methodology indicates that house prices are now overvalued in more than a half of the euro area countries (Frayne et al., 2022[33]) and more substantial correction cannot be ruled out, despite favourable labour market conditions and the borrower-based macroprudential measures introduced recently in many countries (ECB, 2022[34]). While higher interest rates may impair households’ ability to repay their variable rate mortgages, a housing market correction would lower the value of collateral and require banks to provision against potential losses. Hence, the residential real estate risks need to be carefully monitored. If needed, these risks should be addressed by further macroprudential tools, such as increasing capital buffers and additional tightening of borrower-based measures (Valderrama, 2023[35]), while avoiding procyclical effects.

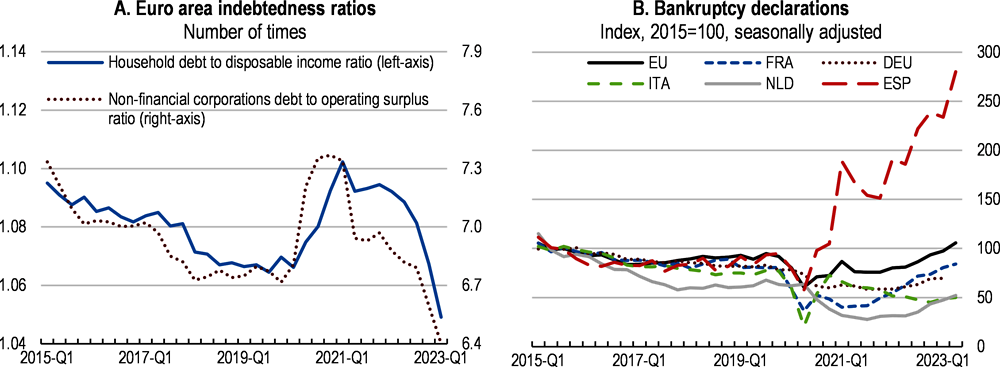

In some countries, both households and firms are highly indebted and thus vulnerable to increases in financing costs. High levels of non-financial corporations’ debt threaten a wave of bankruptcies. The number of bankruptcies among EU firms increased steadily in the fourth quarter of 2022. This was partly driven by a restart of courts’ activity after the pandemic and the withdrawal or phase-out of fiscal support (Figure 1.20). The situation varied across countries, but the largest increase in bankruptcies was in services sectors, such as accommodation and transportation, partly reflecting withdrawal of the pandemic support. In addition, cyclical risks related to heightened inflation and tighter financing conditions in the commercial real estate sector have increased, with potential systemic impact on the financial system and the real economy (ESRB, 2023[36]). The cyclical factors are exacerbated by a shift towards e-commerce, increased demand for flexibility in leasable office space related to a rise in mobile and hybrid working models as well as climate-related policies, such as stricter building standards.

Figure 1.18. Variable rate mortgages and loans are common in many countries

Note: Euro area includes 19 countries. Variable rate loans include loans with floating rate or initial rate fixed for a period of up to 1 year.

In Panel A, November 2021 for Greece instead of August 2022. In Panel B, July 2022 for Finland and Luxembourg, and June 2022 for Greece instead of August 2022.

Source: ECB; Eurostat; and OECD calculations.

Figure 1.19. House prices have deviated strongly from rent prices in most countries

Index 2015=100, seasonally adjusted

Note: In panel A, the latest observation is 2023Q1. In panel B the latest observation is 2023Q2.

Source: OECD Price Statistics database; and OECD calculations.

Figure 1.20. Households and firms remain highly indebted, and bankruptcies are increasing

Note: In Panel A, data refer to the euro area including 19 member countries. Debt is computed as the sum of the following liability categories in the financial balance sheet of the institutional sector: currency and deposits (AF2), debt securities (AF3), loans (AF4), insurance, pension, and standardised guarantees (AF6), and other accounts payable (AF8).

Source: Eurostat Financial Balance Sheets database; Eurostat Non-financial Transactions database; Eurostat Business Registration and Bankruptcy Index database; and OECD calculations.

Macroprudential tools can help increase resilience to financial sector risks from private debt exposures. Preserving and building up macroprudential buffers could support the resilience of banks and other credit institutions by strengthening their ability to absorb losses. Macroprudential buffers should be used in conjunction with other tools, such as prudent risk management practices, and set according to country-specific macro-financial outlooks and banking sector conditions to limit procyclicality (ESRB, 2022[37]). Even at the current late stage of the financial cycle, countries with macro-financial imbalances may increase macroprudential buffers, taking into account the existing levels of capital and the ability of banks to generate profits (ECB, 2022[34]). For example, further build-up of releasable buffers, such as the countercyclical capital buffer, may be desirable when conditions allow. These buffers can be released immediately when adverse developments materialise, improving the capacity of authorities to provide relief to the banking sector.

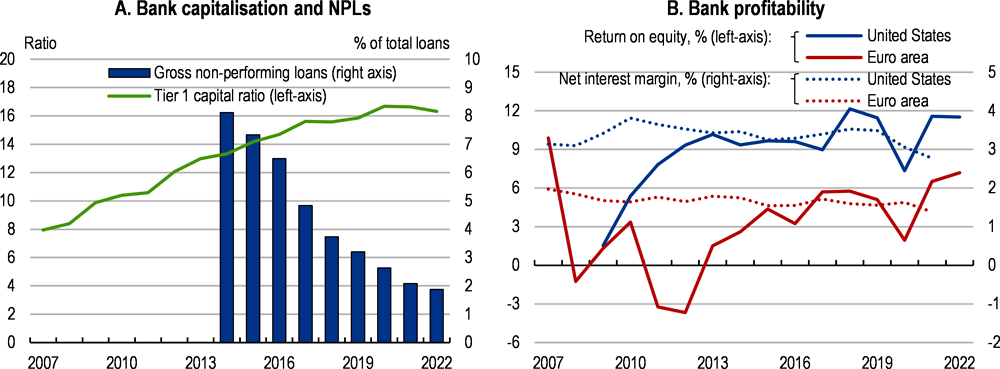

Financial sector integration needs to be stepped up

Overall, European banks hold good quality assets, although the recent market tensions led to a large fall in bank equity prices, increasing the cost of new capital. In addition, the recent deterioration in loan portfolios of banks suggest an increase in credit risk. Until recently, rising interest rates have mainly bolstered short-term profitability, reflecting wider profit margins and still limited loan loss provisions. However, bank profitability may worsen if market turmoil intensifies and threats to asset quality result in higher provisioning needs and increasing stocks of non-performing loans (Figure 1.21). Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, loans to energy-intensive firms have seen higher probabilities of default than loans to other firms. With higher interest rates, banks will also face higher credit risks from exposures to residential real estate markets, as erosion of real disposable income and savings through inflation further weakens the debt servicing capacity of households (ECB, 2022[34]).

Figure 1.21. European banks are well capitalised, but profitability is relatively low

Note: In Panel A, Tier 1 capital ratio refers to regulatory Tier 1 capital to risk-weighted assets. In Panel B, net interest margin corresponds to the accounting value of bank's net interest revenue as a share of its average interest-bearing (total earning) assets.

Source: ECB; IMF Financial Soundness Indicators database; and World Bank Global Financial Development database.

Banking sector policies must address long-standing issues as well as new challenges, such as digitalisation and the green transition. Structural weaknesses include low cost-efficiency, limited revenue diversification and overcapacity in parts of the banking sector. Accelerated digitalisation could help remedy some of these issues, albeit at a cost of greater cyber risks (ECB, 2022[34]). The banking sector seems to have too many institutions that are less profitable than competitors. For example, in 2019 the market share of the top five US banks was 43% of consolidated domestic assets, as against 23% in the euro area (Gabrieli, Marionnet and Sammeth, 2021[38]). Consolidation of the banking sector through cross-border mergers could help improve profitability and reduce overbanking. Compared to domestic consolidation, cross-border mergers could enhance the effects of geographic diversification and encourage the emergence of larger European banks better equipped to compete with their international counterparts. In addition, a consolidated, more profitable banking sector would be in a stronger position to finance the transition to a greener economy and deal with its climate-related exposures.

The EU financial system remains highly bank-dominated and fragmented along national lines, which is unlikely to change in the short or medium term. While two pillars of the banking union, the Single Supervisory Mechanism and the Single Resolution Mechanism, are in place, the third pillar – a common deposit protection scheme – has not yet been achieved. Immediate further steps towards the completion of the banking union involve the review of the Crisis Management and Deposit Insurance (CMDI) framework (Eurogroup, 2022[39]). Hence, the recent Commission’s proposal to reform the CMDI framework (European Commission, 2023[40]) is a step in the right direction. In addition, the banking union could be deepened by ending the reliance on legislative constraints that ring-fence capital and liquidity of cross-border groups along national lines (Enria, 2022[41]). Progress with the banking union will also help advance the capital markets union (Véron, 2014[42]).

Progress on the banking and capital market union has recently been limited. Some headway has been achieved on bank crisis management, including the proposal for harmonized handling of small and mid-sized failing banks and a parallel evaluation of State aid rules for banks in line with the reformed crisis management framework. Since the June 2022 Eurogroup meeting, no progress has been made on the other streams of work. As for the capital markets union, recent significant developments include steps towards a European Single Access Point for corporate disclosures and a post-trade consolidated tape, as well as a single dataset of prices and volumes for securities traded in the EU, proposed in November 2021. In December 2022, the Commission followed up with proposals regarding EU clearing services, harmonisation of certain corporate insolvency rules and simplifying the administrative burden associated with listing on stock exchanges. These steps are welcome, but they need to be followed by further bold steps to defragment European capital markets, as discussed in the 2021 OECD Economic Survey of the euro area (OECD, 2021[43]). Given the multiple trade-offs involved and political sensitivity, the completion of the banking union and capital markets union should be high on the list of priorities for the next Commission after the 2024 European Parliament elections (Table 1.4).

Table 1.4. Monetary and macroprudential policy measures taken since the last Survey

|

Main recommendations of the 2021 Survey |

Action taken since 2021 |

|---|---|

|

Keeping monetary policy accommodative |

|

|

Continue monetary policy accommodation until inflation robustly converges toward the ECB objective. |

In response to the surge in inflation since 2021, the ECB initiated monetary policy normalisation in December 2021 to ensure that inflation returns to the 2% medium-term target. Measures taken include the end of net asset purchases, a cumulative increase in ECB policy rates by 375 basis points, changes to the longer-term refinancing operations, and a gradual reduction of the APP portfolio. |

|

In its next strategic review, the ECB could consider moving towards average inflation targeting in case the inflation objective is not met. |

The next strategy review is planned for 2025. |

|

Exit from pandemic-related financial measures should be gradual. Capital and equity buffers should be rebuilt gradually. |

Vulnerabilities posing medium-term risks accumulated throughout the pandemic period and relate to residential real estate as well as to strong credit growth and increasing indebtedness in the non-financial private sector. To address them, by end-2022 a significant number of countries participating in European banking supervision decided to gradually rebuild or maintain macroprudential capital buffers (countercyclical capital buffer and a sectoral systemic risk buffer). |

|

Take stock of the effectiveness of recently adopted new tools and the suspension of self-imposed limits to the asset purchase programme, prolonging them if needed. |

The ECB evaluates the effectiveness of non-standard monetary policy measures on an ongoing basis. Net asset purchases have stopped in the first half of 2022, a gradual reduction in the APP securities portfolio is taking place since March 2023, while reinvestments are to end in July 2023. |

|

Enhance the economic resilience of the euro area by completing the Banking and the Capital Markets Unions. |

As of April 2023, the Commission has completed 14 of the 16 actions to which it committed in the 2020 Capital Markets Union action plan. On the Banking Union, the Commission in April 2023 proposed reviews of crisis management and deposit insurance framework (CMDI), the Single Resolution Mechanism Regulation (SRMR) and the Deposit Guarantee Schemes Directive (DGSD). The CMDI review aims at better applying the framework, in particular to small and medium-sized banks, and enhancing the use of industry-funded safety nets. |

Fiscal policy needs to become sufficiently restrictive

The challenging economic environment underlines the importance of the appropriate policy mix in the euro area. While the ECB has been tightening monetary policy to keep historically high and persistent inflation under control, fiscal support is being provided to help cushion the impact of high energy costs on households and companies. Short-term fiscal actions to cushion living standards need to avoid a further persistent stimulus to demand at a time of high inflation while maintaining energy saving incentives, thereby ensuring consistency with monetary policy and avoiding adverse effects on fiscal sustainability (OECD, 2022[44]).

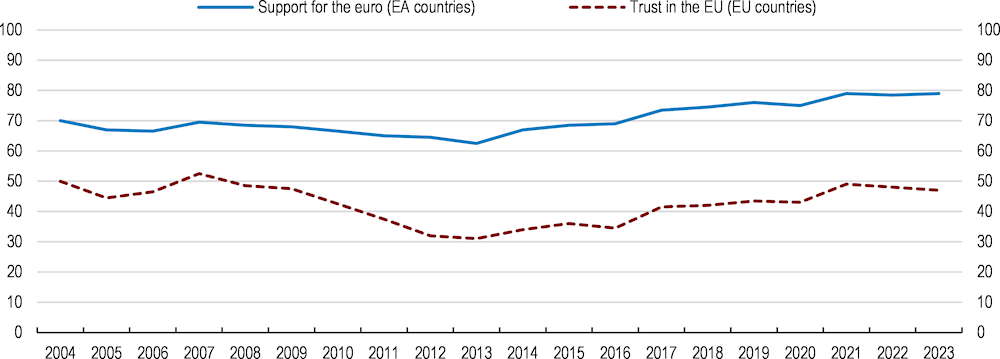

Monetary policy tightening has led to higher costs of borrowing for firms and households and also pushed up interest rates on sovereign borrowing. While refinancing costs for governments increased, sovereign bond spreads have remained stable for most countries and even declined for Italy, Greece and the non-euro area EU countries (Figure 1.22). However, the risk remains that, to the extent that governments continue to issue new bonds beyond simply rolling over maturing debt, the excess supply under tightening financial conditions will lead to greater competition for investors’ demand, pushing sovereign yields further up (Schroeder and Bouvet, 2023[45]).

Figure 1.22. Sovereign borrowing costs increased while the spreads moderated

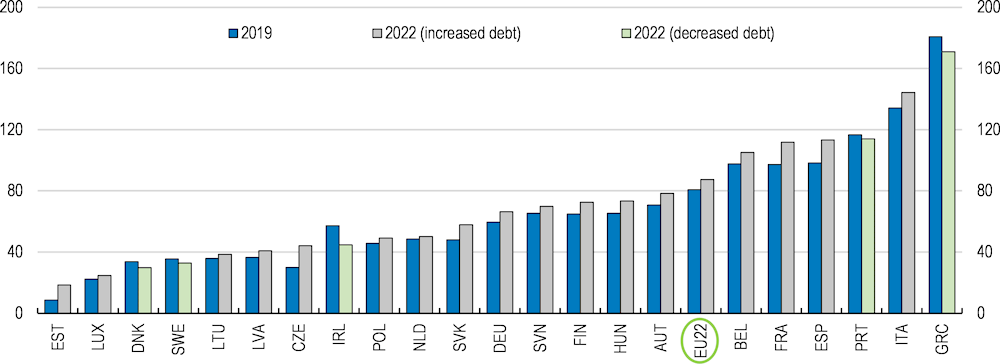

Public debt ratios in the European Union have increased following the disbursement of the unprecedented pandemic and energy crisis support (Figure 1.23). Initially, higher inflation triggered by supply chain disruptions and higher energy and food prices lowered debt-to-GDP ratios, due to a temporary boost in nominal GDP. However, the ensuing decline in real growth, higher interest payments and deteriorating primary deficits eventually pushed up public debt ratios above the pre-pandemic levels.

Figure 1.23. Public debt increased from pre-pandemic levels in most countries

General government debt, Maastricht definition, as a percentage of GDP

Note: Data refers to the European Union member countries that are also members of the OECD (22 countries).

Source: OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections database

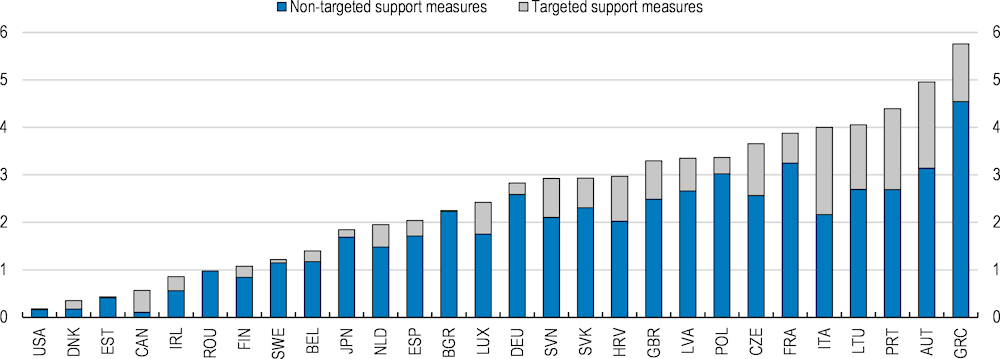

Fiscal support to cushion the impact of high energy costs has been high and mostly untargeted (Figure 1.24). Support to energy consumers amounted to more than 2% of GDP in some EU countries, well above the 0.7% of GDP in the median OECD economy. Price support, such as reduced taxes and reduced or regulated prices, has dominated income support and was largely untargeted. Income support, including transfers and tax credits to consumers, was better targeted to vulnerable households. However, non-targeted income support measures, such as private transportation subsidies for employees driving to work, are not infrequent. Price support measures are relatively simple to introduce and communicate, but they weaken incentives to reduce energy use, provide disproportionate support to better-off households and risk further stoking energy and consumer price inflation as well as its distributional implications. There is a strong case for gradually withdrawing broad fiscal support. Targeted support for vulnerable households inadequately covered by the general social protection system may still be needed, especially since vulnerability to high energy prices also depends on other factors than income, such as the inability to renovate energy-inefficient dwellings and high energy needs due to age or geographical factors (Pisu et al., 2023[46]).

Figure 1.24. Fiscal support during the energy crisis was mostly untargeted

Announced spending on energy support measures, % of GDP, 2022-23

Note: Support measures are taken in gross terms, i.e., not accounting for the effect of possible accompanying energy-related revenue-increasing measures, such as windfall profit taxes on energy companies. Where government plans have been announced but not legislated, they are incorporated if it is deemed clear that they will be implemented in a shape close to that announced. Gross fiscal costs reflect a combination of official estimates and assumptions on how energy prices and energy consumption may evolve when the support measures are in place. Costs are estimates for announced spending over 2022 and 2023, naturally subject to greater uncertainty in the current year. Measures corresponding to categories “Credit and equity support” and “Other” have been excluded. When a given measure spans more than one year, its total fiscal costs are assumed to be uniformly spread across months. For measures with no officially announced end-date, an expiry date is assumed and the fraction of the gross fiscal costs that pertains to 2022-23 has been retained. The current vintage of the database has a cut-off date of 20 April 2023.

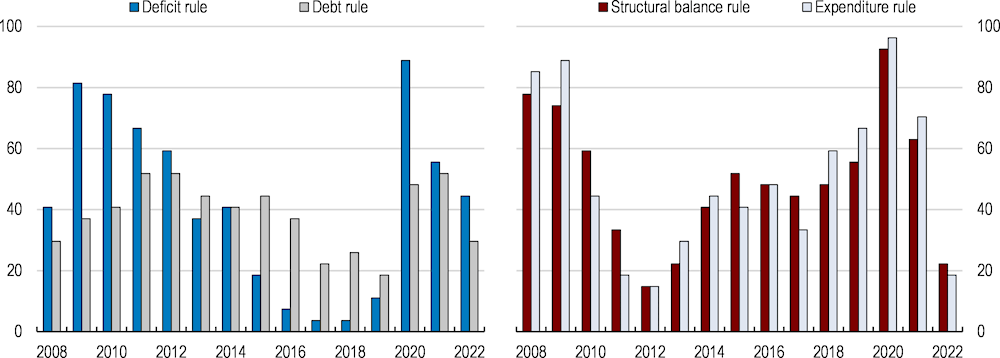

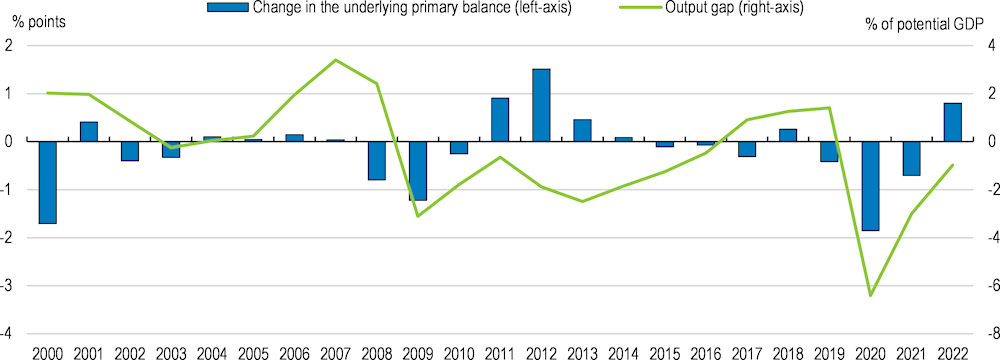

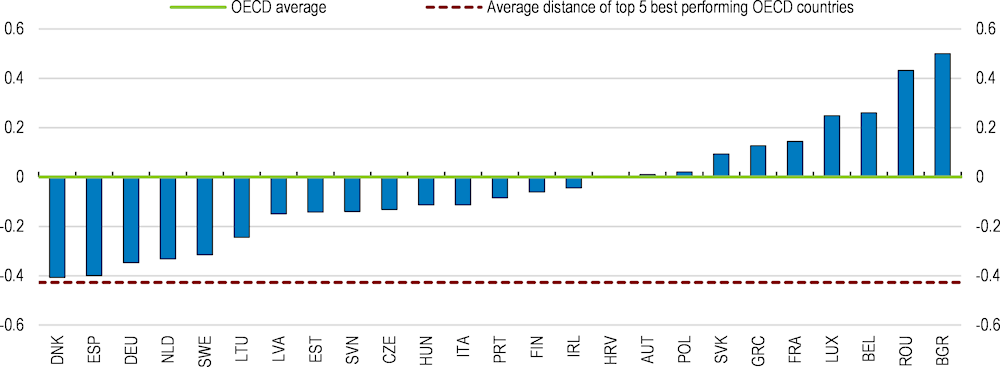

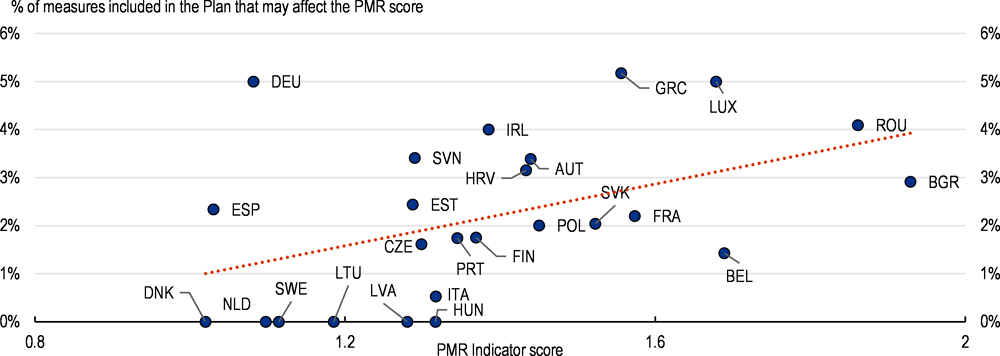

Source: OECD Energy Support Measures Tracker