This chapter comments on tax administration performance in managing the collection of outstanding taxes, and describes the features of a modern tax debt collection function. It goes on to provide examples of approaches applied by administrations to prevent debt being incurred.

Tax Administration 2023

7. Collection

Abstract

Introduction

The collection function involves engaging with, and potentially taking enforcement action against those who do not file a return on time, and/or do not make a payment when it is due. Even with the growth in pre-filled or no return approaches over past years (see Chapter 4), the filing of a tax return or declaration still is still required in many jurisdictions participating in this publication. Although 2021 on-time filing rates averaged between 76% and 88%, at least 160 million returns were not filed on time that year (see Tables 4.4. and A.44. to A.47.). It is important therefore that administrations continue to focus efforts on improving the timely collection of late and outstanding returns.

Looking at the collection of late payments, all but one administration participating in the survey report staff resources being devoted to taking action to secure the payment of overdue tax payments (the Chilean tax administration reported not being responsible for debt collection; see Table A.20). Information provided by administrations in ISORA 2022, attributes on average around 11% of total staff numbers to the collection function (see Table D.8).

The legislative framework provides tax officials with powers that enable them to undertake certain actions in relation to the management of debt, the collection of amounts overdue and the enforcement actions that can be taken against delinquent debtors. The 2019 edition in this series had a section summarising the availability of such management, collection and enforcement powers and their usage by tax administrations (OECD, 2019[1]). Since then, the ISORA survey did not take a closer look at this topic. However, it is fair to assume that the availability and usage of such powers has not significantly changed.

This chapter:

Takes a brief look at the features of a modern tax debt collection function and the elements of a successful tax debt management strategy;

Comments on tax administration performance in managing the collection of outstanding debt; and

Provides examples of preventive approaches to debt being incurred.

Features of a debt collection function

To maintain high levels of voluntary compliance and confidence in the tax system, administrations must ensure that their debt collection approaches are both “fit for purpose” and meet taxpayer’s expectations of how the system will be administered. This means not only taking firm action against taxpayers that knowingly do not comply, but also using more customer service style approaches where taxpayers want to meet their obligations but for understandable reasons, such as short-term cash-flow issues, are not able to do so. Increasingly, tax administrations are taking an end-to-end or systems view of their processes and researching the reasons why returns may not be filed or payments made. They are also using information about the taxpayer’s previous history, to identify patterns and/or anomalies. Box 7.1 highlights some new initiatives in this field.

The 2014 report Working Smarter in Tax Debt Management (OECD, 2014[2]) provided an overview of the modern tax debt collection function, describing the essential features as:

Advanced analytics – that make it possible to use all the information tax administrations have about taxpayers to accurately target debtors with the right intervention at the right time.

Treatment strategies – the collection function needs a range of interventions, from those designed to minimise the risk of people becoming indebted, to support taxpayers to make payments and to take appropriate enforcement measures where appropriate.

Outbound call centres – which make it possible to efficiently pursue a large number of debts.

Organisation – debt collection is a specialist function and is usually organised as such. The right performance measures and a continuous improvement approach help drive desired outcomes.

Cross border debts – the proper and timely use of international assistance is crucial, particularly the “Assistance in Collection Articles” in agreements between jurisdictions.

The 2019 report Successful Tax Debt Management: Measuring Maturity and Supporting Change (OECD, 2019[3]) provides further insights into the elements of a successful tax debt management strategy, setting out four strategic principles that tax administrations may wish to consider when setting their strategy for tax debt management. These principles focus on the timing of interventions in the tax debt cycle, from consideration of measures to prevent tax debt arising in the first place, via early and continuous engagement with taxpayers before enforcement measures, to effective and proportionate enforcement and realistic write-off strategies. The underlying premise for these principles is that focusing on tackling debt early, and ideally before it has arisen, is the best means to minimise outstanding tax debt. The report also contains an overview of a Tax Debt Management Maturity Model and a compendium of successful tax debt management initiatives.

Box 7.1. Examples – Improving debt management

Australia – Disclosure of business tax debt

In Australia, the Disclosure of Business Tax Debt legislation aims to support more informed decision making within the business community by making overdue tax debts more visible, as well as encouraging taxpayers to engage with the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) to manage their tax debts. This reduces the unfair advantage obtained by businesses that do not pay their tax debts on time.

Where taxpayers do not actively engage in relation to their tax debts the ATO can disclose these debts to Credit Reporting Bureaus. ATO action is triggered when a client meets the legislative criteria of having an ‘unmanaged’ debt of more than AUD 100 000 outstanding for greater than 90 days and they remain in business.

A systems solution has been implemented to automate client selection and initial contact through issuing an Intent to Disclose notice (ITDN). This enables an “all in” approach with all eligible clients treated with minimal manual intervention. Where the ITDN has not prompted action; follow up phone contact is initiated before disclosure is considered. The combination of these steps has proven to prompt significant client re-engagement in managing their tax debts. As a result, by 31 December 2022 1 in 3 relevant taxpayers contacted had taken action to manage their tax debt, and in excess of AUD 2 billion is now under an active payment arrangement.

Georgia – Tax debt management reform

New tax debt management mechanisms have been deployed by the Georgia Revenue Service (GRS) to increase taxpayers' compliance. This has been achieved by:

Strengthening of preventive mechanisms by informing taxpayers about the possibility of debts accruing and explaining payment methods. This is achieved by sending text messages and electronic messages in the taxpayer’s own page of the GRS.

Improving the rate of debt recovery by detecting taxpayers with debt in a unified database, which also identifies those with increasing debts and targeting them for interventions. This takes into account the financial position of taxpayers and targets collection measures based on the analysis of information available at the GRS and communication with taxpayers. In addition, for those taxpayers who co-operate a payment schedule can be established.

Reducing of old debt through use of a “Currently Non-collectable Status” for the taxpayer. Repeated placement under the status of “Currently Non-collectable Status” is a prerequisite for writing off bad debt, and debt write-off is now carried out periodically so is does not affect taxpayer’s business continuity and economic development.

These measures allow for the creation of a more flexible and effective model of debt management based on the principle of co-operation with taxpayers, which is helping improve the level of voluntary compliance, as this model provides timely information to taxpayers on their rights, obligations and expected collection measures.

Slovak Republic – Removing the driving license of tax debtors

In the Slovak Republic from 2020, unless a debtor’s income is reliant on a driving license (for example, a bus driver, lorry driver or taxi driver) a debtor can be prevented from holding a driving license. This procedure begins with issuing a tax notice, giving the debtor a chance to pay the tax overdue and to avoid removing the driving license, along with a chance to appeal the recovery process as such. The recovery procedure is done in close co-operation with the police, as only the police is entitled to withdraw the driving license. The impact on debt collection has been significant, as even tax debts not recoverable for a very long time had been paid by the debtors after launching this new initiative.

Spain – Auction app

In 2022, the Spanish Tax Agency (AEAT) launched a system for searching real estate and goods included in auction procedures. The new functionality aims to increase the number of auctions and make it more accessible to citizen’s which should increase the values achieved at auction, benefiting both AEAT and debtors. This is complemented by a dedicated telephone service which provides more details to potential bidders and supports those who win the auction.

The system has been designed to locate easily any property and find goods that meets a user’s preferences. It also incorporates the possibility of saving favorite properties and sharing them. In addition, an alert subscription system has been enabled to notify the interested party when an auction that meets the required criteria is launched. Access to the system is granted through various government digital identity platforms, and announcements related to auctions are through the AEAT web portal and social media channels.

United Kingdom – Self-Serve Time to Pay

His Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC) vision for the future of tax administration in the United Kingdom is designed to improve its resilience, effectiveness, and support for taxpayers, ensuring it is as easy as possible for customers experiencing financial difficulties to pay any arrears that may be owed, whether that’s in full or as part of a payment plan.

In 2022, HMRC expanded the Self-Serve Time to Pay (SSTTP) service to include Employers PAYE. For the first time, employers with an eligible Employers PAYE debt can self-serve when setting up a Time to Pay arrangement.

Customers have told HMRC they prefer to self-serve when it comes to debt, and this service will also allow HMRC’s Customer Service Group to focus on more complex queries and those customers who need one-to-one support when tackling their debts.

The digital service is accessible via several entry points including Business Tax Account, and GOV.UK. The service works by providing eligible customers with the ability to make payments up front and set up a payment plan (by direct debit) for eligible self-assessment and Employers PAYE debts.

In the first two months, around 600 customers set up plans with debt values in excess of GBP 2.5 million. These results have been achieved without active promotion of the service.

During 2023, HMRC will further extend the service, making it available for customers with VAT debts, reducing the burden some of HMRC’s most vulnerable customers are experiencing whilst providing reassurance that the tax debt they owe is being managed fairly.

Sources: Australia (2023), Georgia (2023), Slovak Republic (2023), Spain (2023) and United Kingdom (2023).

Performance in collecting outstanding debt

The total amount of outstanding arrears at fiscal year-end remains very large, in the region of EUR 2.5 trillion. For survey and comparative analysis purposes, “total arrears at year-end” is defined as the total amount of tax debt and debt on other revenue for which the tax administration is responsible that is overdue for payment at the end of the fiscal year. This includes any interest and penalties. The term also includes arrears whose collection has been deferred (for example, as a result of payment arrangements).

The total amount of “collectable arrears” at fiscal year-end was around EUR 710 billion. Collectable arrears is defined as the total arrears figure less any disputed amounts, or amounts that are not legally recoverable. It also includes arrears which are unable to be collected, but where write-off action has not yet occurred.

As a result, and despite efforts to make data comparable, care needs to be taken when comparing specific data points as the administration of taxation systems and administrative practices differ between jurisdictions. Care also needs to be taken because of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, which is likely impacting on the 2020 and 2021 figures. This is because many governments took action to support individuals and businesses as part of the pandemic by extending payment terms, or suspending collection of outstanding debt. This may well be a major factor in the increase in collectable arrears after 2019. (CIAT/IOTA/OECD, 2020[4]) Future editions of this series will likely continue to reflect the impact of these actions as tax administrations slowly return to pre-pandemic activities.

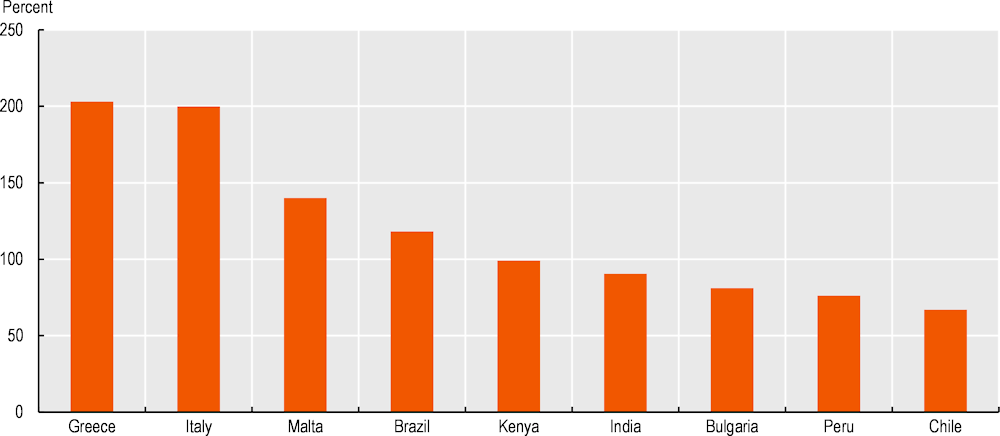

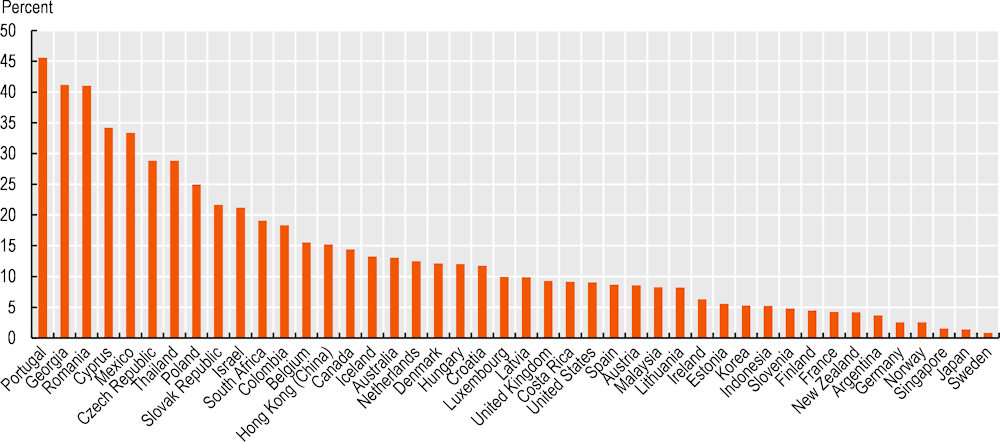

In 2021, the average ratio for total year-end arrears to net revenue collected was 32% (see Table D.33.). As in past years, it remains heavily influenced by the very large ratios of a small number of jurisdictions that show ratios above 50%. If these jurisdictions are removed, the average reduces to around 14% of net revenue (see Figures 7.1. and 7.2. as well as Table D.33.). (Note: The percentages mentioned in this paragraph are different from those in Table 7.1. as the table shows average arrears ratios for those jurisdictions that were able to provide the information for the years 2018 to 2021.)

Table 7.1. Evolution of average arrears ratios between 2018 and 2021

|

Arrears ratio |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

Change in percent (between 2018 – 2021) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Total year-end arrears as percentage of net revenue collected (50 jurisdictions) |

28.2 |

27.9 |

34.7 |

30.2 |

+7.0 |

|

Total year-end collectable arrears as percentage of total year-end arrears (40 jurisdictions) |

50.7 |

51.5 |

54.3 |

54.4 |

+7.2 |

Note: The table shows average arrears ratios for those jurisdictions that were able to provide the information for the years 2018 to 2021. The number of jurisdictions for which data was available is shown in parenthesis. Data for Bulgaria was excluded from the calculation of the average for the ‘total year-end arrears as a percentage of net revenue collected’ as its data for the four years is not comparable (see Table A.55).

Source: Table D.33.

When comparing 2021 and 2020 data, a decrease in total year-end arrears to net revenue collected is visible. This follows the significant increase of the ratio during 2020 – the first year of the pandemic – where the ratio increased on average by more than 20 percent. However, despite this decrease in 2021, the ratio of total year-end arrears to net revenue collected remains 7 percent above the 2018 values (see Table 7.1.).

This decrease between 2020 and 2021, is also generally reflected in the jurisdiction level data: In 2020 the ‘total arrears to net revenue collected’ ratio increased in around 85% of jurisdictions, whereas in 2021 the ratio decreased in 68% of jurisdictions (see Table D.33.).

Figure 7.1. Total year-end arrears as a percent of total net revenue, 2021

Figure 7.2. Total year-end arrears as a percent of total net revenue, 2021

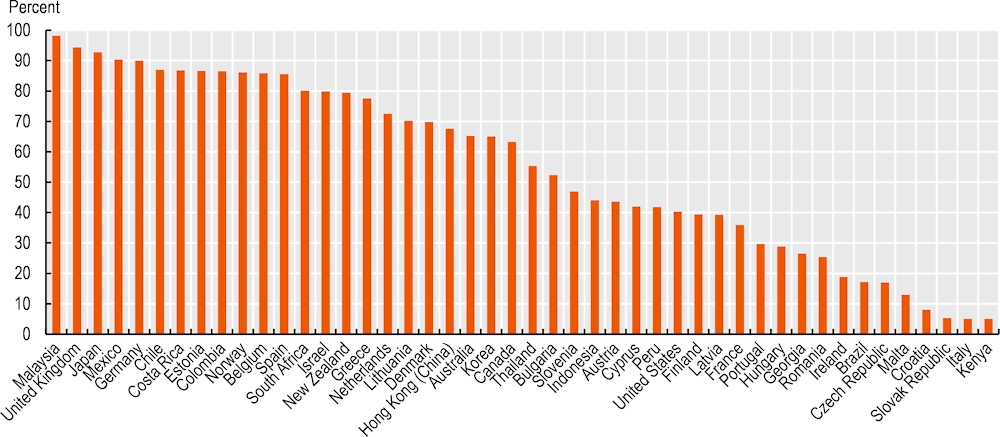

Looking at collectable tax arrears, the 2021 data shows that on average more than half of the total arrears are considered collectable. That is an increase of 7% compared to 2018. (See Table 7.1.) However, Figure 7.3. illustrates well the differences between jurisdictions: in some jurisdictions almost all arrears are considered collectable, while in others almost all arrears are considered not collectable.

Figure 7.3. Total year-end collectable arrears as percentage of total year-end arrears, 2021

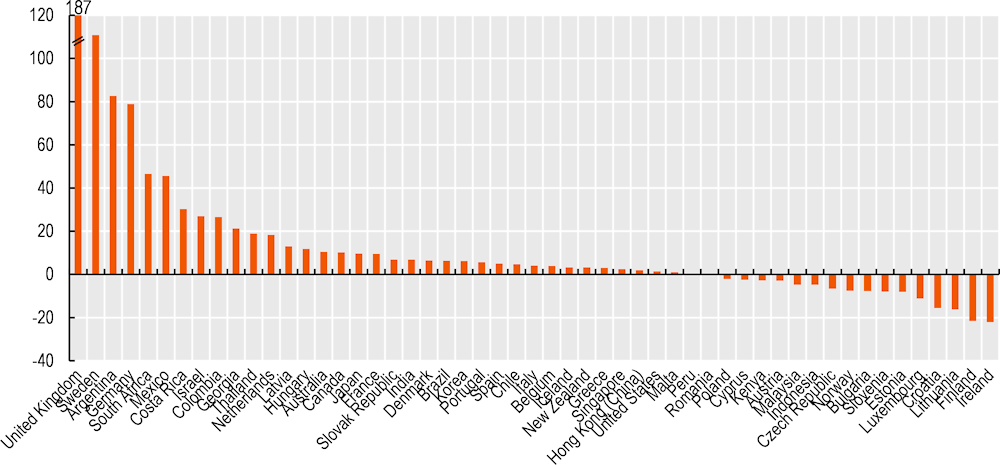

Figure 7.4. Movement of total arrears between 2020 and 2021

Figure 7.4. show the change of total year-end arrears between 2020 and 2021. In absolute numbers, the total year-end arrears increased in 36 out of 53 jurisdictions that were able to provide the information.

In looking at the amount of arrears for the main tax types (see Table 7.2.), it seems that individuals are more likely to pay on time than businesses. The average ratio of corporate income tax (CIT) arrears to CIT net revenue collected and the ratio for value added taxes (VAT) are around 25% in 2021. At the same time, the ratio for personal income tax (PIT) is much lower at 15%.

The data also confirms the difficulties that businesses encountered at the beginning of the pandemic. The average ratios for CIT and for VAT increased significantly between 2019 and 2020 but went back to pre-pandemic levels in 2021.

At around 7%, the ratio is the lowest for employer withholding taxes (WHT). However, this is expected, as employers are responsible for forwarding those taxes to the administration on behalf of their employees and have no right over the amounts.

Table 7.2. Evolution of average ratio of year-end arrears to net revenue collected by tax type between 2018 and 2021

|

Tax type |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

CIT arrears as percentage of CIT collected (39 jurisdictions) |

24.0 |

26.8 |

30.5 |

24.3 |

|

PIT arrears as percentage of PIT collected (42 jurisdictions) |

16.2 |

14.2 |

15.5 |

15.0 |

|

Employer WHT arrears as percentage of PIT collected (34 jurisdictions) |

7.2 |

6.5 |

7.2 |

6.9 |

|

VAT arrears as percentage of VAT collected (39 jurisdictions) |

23.8 |

23.5 |

30.2 |

25.1 |

Note: The table shows the average ratios for jurisdictions that were able to provide the information for the years 2018 to 2021. The number of jurisdictions for which data was available is shown in parentheses. Data for Bulgaria was excluded from the calculation of the average for the total year-end arrears as a percentage of net revenue collected as its data for the three years was not comparable (see Table A.55). Further, because they would distort the averages, data for Brazil and Greece was excluded in the calculation of the average for CIT and data for Malta was excluded in the calculation of the average for VAT.

Source: Tables D.36 and D.37.

Preventive approaches

The range of actions undertaken by tax administrations to prevent debt from arising and to collect outstanding arrears continues to evolve. Box 7.2. illustrates the approaches taken by some administrations. Advances in predictive modelling and experimental techniques as reported in the OECD report Advanced Analytics for Better Tax Administration (OECD, 2016[5]) and in the compendium of successful tax debt management practices contained in the OECD report Successful Tax Debt Management: Measuring Maturity and Supporting Change (OECD, 2019[3]) are helping many administrations better match interventions with taxpayer specific risk. The approaches used fall into one of the following categories:

Predictive analytics, which tries to understand the likelihood of certain outcomes and, as regards debt collection, includes modelling the risk that an individual or company will fail to pay as well as models that attempt to assess the likelihood of insolvency or other payment problems.

Prescriptive analytics, which is about predicting the likely impact of actions on taxpayer behaviour, so that tax administrations can select the right course of action for any chosen taxpayer or group of taxpayers. (OECD, 2016[5])

Many administrations are blending both practices and have trialled a variety of approaches aimed at changing “taxpayer behaviour.” As pointed out in Chapter 6, three-quarters of administrations are using behavioural insight methodologies or techniques. These practices have the potential to transform the approach to tax debt as administrations move away from the ‘one-size-fits-all’ approaches (where it is cost-effective to do so) and instead try to identify:

Which cases should be subject to an intervention;

When to intervene (for example, even before a return or payment might be due); and

Which type of action would achieve the best cost-benefit outcome.

Box 7.2. Examples – targeting interventions

Australia – Director penalty awareness letters

The most significant impact of COVID-19 on the ATO has been the dramatic increase in unpaid tax debts. As Australian states and territories implemented their roadmaps out of lockdowns so too did the ATO, who remained committed to engaging with company representatives about unpaid tax debt by offering tailored support and assistance rather than enforcement. Where taxpayers didn’t engage, the ATO recommenced firmer recovery actions.

Traditionally, the ATO escalates the recovery through a firm action warning letter, a Director Penalty Notice (DPN), which encourages payment and warns company representatives of possible recovery actions. However, the ATO realised that individual directors may not be aware of the debt or their personal liability to the debt until a DPN is issued. Therefore, before considering issuing a DPN, the ATO implemented an awareness strategy to individually inform the director of:

The company’s outstanding debt;

Their personal liability to unpaid debts under the director penalty regime;

A director’s obligation to make sure the company pays;

Pathways for them to get the company to re-engage; and

That the ATO may issue a DPN directly to each director liable if the company does not act.

To date, approximately 70 000 letters have been issued to directors, and as a result with significant amounts of debt have been paid in full, and even more brought under management through payment plans. The outcomes of this campaign have been comparable with activities derived from escalated and firmer action campaigns, yet in this instance have only required the investment of light touch engagements.

Latvia – Combating illegal phoenixing

When an old entity is transferred to a new one, the State Revenue Service (SRS) still has the right to collect from unpaid tax owed by the old entity from the new one, so the SRS must evaluate and check if in fact a transfer has taken place.

The transfer of an entity is evidenced by various facts and circumstances that are evaluated against compliance with general criteria decided in the various legal cases. Depending on the outcome, a warning is sent to the successor entity with a deadline for payment of overdue taxes or a request for submission of evidence that proves that it is not a transfer. SRS also notes that it can offer support in the taxpayer's efforts for voluntary compliance, giving the successor company opportunity to participate in resolution.

If overdue taxes are not paid or an agreement on voluntary fulfilment of obligations is not concluded and the taxpayer does not refute the facts established by SRS, the SRS takes a decision on collection of overdue tax payments that comes into force immediately.

Sources: Australia (2023) and Latvia (2023).

References

[4] CIAT/IOTA/OECD (2020), “Tax administration responses to COVID-19: Measures taken to support taxpayers”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/adc84188-en.

[3] OECD (2019), Successful Tax Debt Management: Measuring Maturity and Supporting Change, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/tax/forum-on-tax-administration/publications-and-products/successful-tax-debt-management-measuring-maturity-and-supporting-change.htm (accessed on 22 May 2023).

[1] OECD (2019), Tax Administration 2019: Comparative Information on OECD and other Advanced and Emerging Economies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/74d162b6-en.

[5] OECD (2016), Advanced Analytics for Better Tax Administration: Putting Data to Work, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264256453-en.

[2] OECD (2014), Working Smarter in Tax Debt Management, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264223257-en.