Taxpayer registration and identification is critical for the effective operation of a tax system. This chapter comments on some of the significant characteristics of those processes.

Tax Administration 2023

3. Registration and identification

Abstract

Introduction

A comprehensive system of taxpayer registration and identification is at the foundation of an effective tax system. It is the basis for supporting a range of tax administration activities such as self-assessment, value-added tax and withholding tax regimes, as well as third party reporting and matching. This chapter comments on several issues of significance in taxpayer registration and identification, including levels of registration, registration channels and identity management, and how the digital transformation affects these services.

Levels of registration

The fundamental importance of an effective tax registration system cannot be overstated. These processes need to both manage those taxpayers that are “part of the system” and to help identify those yet to register. Furthermore, they need to be able to monitor and determine actions and interventions to establish any liability to tax for both individuals and corporate bodies, even in systems where filing is not mandatory.

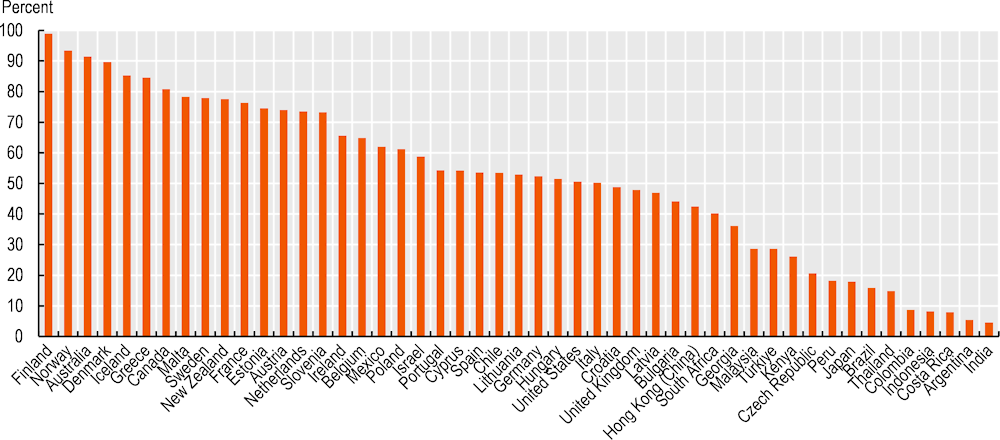

Figure 3.1. provides information on the rate of registered personal taxpayers as a percentage of the total population. This shows a wide range of registration rates, often reflecting the level of integration the tax administration has with other parts of government.

Figure 3.1. Registration of active personal income taxpayers as percentage of population, 2021

Registration channels

While the majority of administrations are solely responsible for the system of registration for tax purposes within their jurisdictions, previous editions of this series have shown that in many jurisdictions the registration processes can also be initiated outside of the tax administration through other government agencies (OECD, 2019[1]).

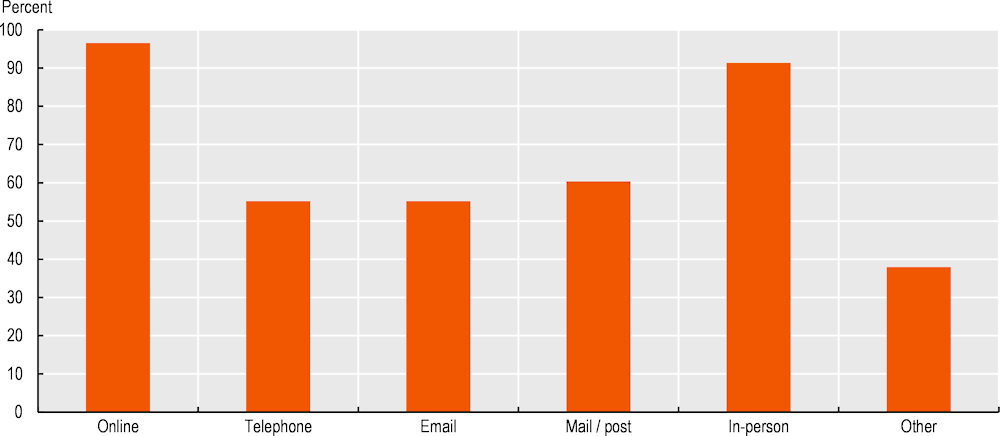

In looking at how taxpayers can register, almost all administrations reported they provide more than one channel for taxpayers to use and 97% report that it is possible to register online (see Figure 3.2.). Compared to data from the 2017 edition of this series (OECD, 2017[2]) this is a 27-percentage point increase. Although in-person registration continues to be an important channel, or element of the registration process, often due to the need to provide physical evidence of identity, it is expected that as digital identity systems become more sophisticated, the dominance of online channels will grow.

Figure 3.2. Availability of registration channels for taxpayers, 2021

Note: The registration channels may not always be available for all tax types or taxpayer segments.

Sources: Tables A.74 and A.75

While the underlying survey does not allow identification of whether the online registration channel is available for all tax types or taxpayer segments, jurisdictions report significant investment in digital identity programmes, including using artificial intelligence to improve efficiency and effectiveness. This is helping cement digital identity as the cornerstone of successful digital transformation activity, as the OECD Tax Administration 3.0 report (OECD, 2020[3]) identified. Indeed, in one jurisdiction (Saudi Arabia), taxpayers can only register online (see Tables A.74. and A.75.).

This shift to digital channels may also help drive further efficiencies, though as the shift to digital gathers pace further attention is being paid to those who may not have access to digital services. The example from Canada in Box 3.1. illustrates some of the work taking place to address this.

Box 3.1. Examples – Impact of digital systems on identity systems

Canada – Community Volunteer Income Tax Program Authentication Team

The Community Volunteer Income Tax Program (CVITP) established a dedicated team of individuals to conduct client identification authentications for CVITP organisations and volunteers, so they can focus on providing services to clients. When a volunteer needs assistance confirming a client’s identity, they can contact this dedicated Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) team who will call the client to assist in the verification. Volunteers request the identification authentication via email, and then a call is arranged between the client and the CRA representative. To pass confidentiality, an individual must provide basic client information such as their social insurance number, name, date of birth and current address. They then must also answer two additional questions, confirmed via the agent’s access to “Taxpayer Services Agent Desktop”, while referring to the Technical Help Guide for most up-to-date confidentiality measures. Once the identity authentication is completed, the volunteer is informed and can continue working on the client’s return. The support this team provides increases the CVITP’s overall capacity to provide tax filing assistance and improves client access to benefits and credits.

The authentication team also serves those who also struggle to authenticate in person. Some individuals may not possess regular government issued identification which can make it very difficult for them to access the service. The authentication team allows these individuals to work directly with CRA field employees to validate their identity and receive service from the CVITP.

Japan – Using a smartphone to authenticate identity

For online filing, as well as using the taxpayer ID and password, in Japan it is also possible since 2019 to authenticate identity using the national identification card ‘My Number Card’. Recently, for certain online services, the use of ‘My Number Card’ became mandatory. For this purpose, taxpayers are required to use a smart card reader.

The use of a smart card reader can be a cumbersome process, and to make things easier for taxpayers, the ‘My Number Card’ authentication can now be completed via smartphone. To do this, taxpayers need to use the ‘Mynaportal’ app, which is an online service managed by the Japanese government that allows users to complete various administrative procedures. This app reads a barcode displayed on their computer and completes the authentication process.

Mexico – Digital authentication systems

The Mexican Tax Administration Service (SAT) has established the Biometric Accreditation Service, enabling taxpayers to securely log in and validate their biometric data including fingerprints, iris scans, photos, and signatures. This ensures that the taxpayer’s electronic signature holds legal validity.

The identity accreditation process involves the validating taxpayer data, such as the Federal Taxpayer Registry information and the Unique Population Registry Code, along with fingerprints and iris scans. Moreover, there is an offline contingency mode in place, allowing information to be submitted for validation even if communication with the central servers is disrupted.

All these essential components seamlessly interact to meet the needs of SAT’s taxpayer services, guaranteeing that every electronically signed document is attributed to an individual with valid identification. The service operates through 370 enrolment units spread across the nation, supported by 11 central servers, and handles approximately 300 000 enrolments per month.

Sources: Canada (2023), Japan (2023) and Mexico (2023).

Integration with other parts of government

Given the pivotal role that registration and taxpayer identification play in underpinning the tax system, having up-to-date tax registers remains a high priority for most tax administrations. As past editions have shown, the large majority of administrations have formal programmes in place to improve the quality of the tax register (OECD, 2019[1]).

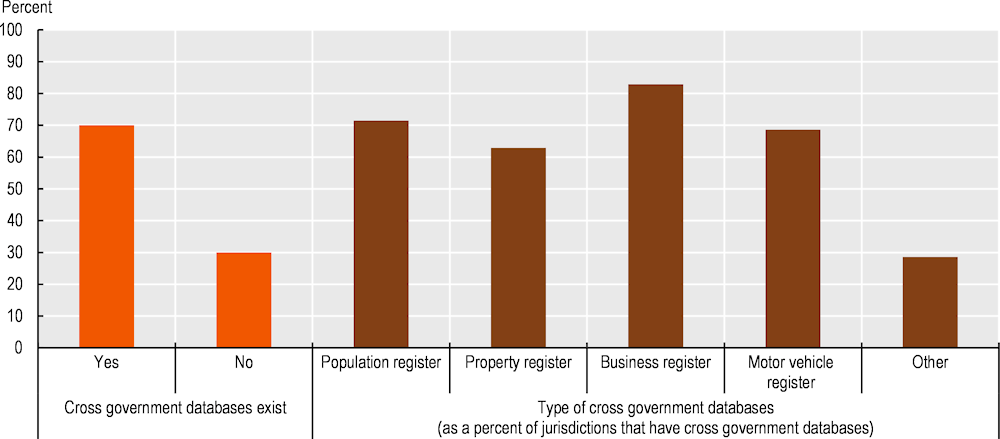

Therefore, it is unsurprising that other government bodies may wish to use the tax administration register for their own purposes to provide services to citizens or ensure compliance with laws and regulations. This is leading to the creation of cross government databases. As Figure 3.3. illustrates, 70% of administrations report the existence of a range of available databases.

Integration across government is increasing as governments see the potential in using information maintained by tax administrations, such as taxpayer address and bank information, to contact citizens and businesses or to make direct benefit or support payments (OECD, 2020[4]).

This is leading to closer collaboration between government agencies, and many of them are integrating (parts of) their IT systems to make tax registration part of other actions taxpayers undertake. For example, registering for tax at the same time as registering a company or registering the birth of a child; and/or to use the same identifier to allow taxpayers to access other government services.

Figure 3.3. Cross government databases: Availability and database types, 2022

Note: The figure is based on data from 52 jurisdictions that are covered in this report and that are included in the ITTI database.

Source: OECD et al (2023), Inventory of Tax Technology Initiatives, https://www.oecd.org/tax/forum-on-tax-administration/tax-technology-tools-and-digital-solutions/, Table DM3 (accessed on 22 May 2023).

Box 3.2. Czech Republic – Data sharing between agencies

In the Czech Republic, companies are obliged to file financial statements and other data to the public register which is administered by the Ministry of Justice. However, companies also send financial statements as an attachment to the tax return. Since 2013, negotiations have been ongoing among the Ministry of Justice, Ministry of Finance and General Financial Directorate to allow the transfer of data obtained during the administration of taxes to the registry courts, which would eliminate duplication.

As a result and after solving legislative and technical issues, selected legal entities can ask the income tax administrator to pass on financial statements to the registry court, when they file their tax return and meet both filing requirements at the same time starting from 2022.The transfer of information is not done automatically but it is conditional on the decision of the company.

This new option has led to a decrease of administrative burden and a simplification of the processes for taxpayers. It is also increasing the reliability and trustworthiness of published financial statements as a result of the direct connection with the data given to the tax office. It is expected that approximately 300 000 companies could benefit from this new option.

Source: Czech Republic (2023).

Identity management

All tax administrations, whether required to by law or as a matter of sound business practice, put considerable effort into ensuring the security of taxpayer information. In addition to internal processes to prevent unlawful attempts to obtain information and to ensure taxpayers’ rights are protected, all administrations have processes to ensure the person they are dealing with is in fact the taxpayer. Increasingly these approaches, which in many instances have now been extended to multi-step authentication, are making use of biometric information, unique to the taxpayer.

Tax administrations face similar challenges to other organisations in dealing with individuals or organisations that may misuse personal information to impersonate taxpayers in order to commit fraud. The on-going and, in many cases, organised nature of this activity is requiring administrations to devote considerable effort to the prevention of identity theft. Box 3.3. contains examples of the work tax administrations are doing in this respect.

Box 3.3. Examples – Identity management

Argentina – Dual Factor Authentication

All services and digital apps available in the Argentinian tax administration (AFIP) portal have different security levels and with the use of the mobile app “Token AFIP”, AFIP has implemented a dual authentication factor process for those taxpayers carrying out sensitive transactions or who wish to enhance the security of their digital procedures with AFIP.

Taxpayers using this service need to:

Download the mobile app “Token AFIP” to their mobile phone;

Go to an AFIP office to show proof of identity and activate the token or go to an ATM to show proof of identity to activate the token; and

Login to the AFIP web site and then activate the app using the tax login code and the one-time password generated by the “Token AFIP”.

China (People’s Republic of) – Unified Identity Management Platform

The Unified Identity Management Platform is a digital identity centre covering all the stakeholders in the paying taxes/fees ecosystem, including taxpayers, intermediaries and tax officials. As the only portal of tax-related applications across all levels of tax services, the platform provides unified identity management, identity authentication, access control, password service and certificate service.

It utilises different combinations of authentication methods, including names, email account, mobile number, SMS, password, biometrics and so on, to offer five-level authentication, corresponding to different risk levels.

This hierarchical authentication process takes into account both security and convenience. It satisfies the differentiated needs of varied mobile applications in terms of security and privacy protection, and at the same time gives consideration to the taxpayers’ needs of easy operation when handling simple business, reducing the cost of verification for taxpayers.

For example, if a taxpayer only needs to make an enquiry they can choose the more convenient static password or dynamic password to complete the authentication. If they need to issue invoices, they can directly switch to the two-factor authentication with face recognition, or use static password and then provide face recognition authentication. The Platform also has the potential to support the State Taxation Administration of China’s internal control work as the digital identity of every player involved in a work stream, including those of tax officials, is traceable.

Sources: Argentina (2023) and China (People's Republic of) (2023).

Common approaches to digital identity

Once the domain of multi-national businesses and those involved in international trade, small and medium-sized enterprises and individual taxpayers are now increasingly earning income sourced outside their jurisdiction of residence. As a result of the proliferation of online market-places and sharing and gig economy platforms, it is now easier than ever for example, to rent out holiday homes or sell goods abroad through online platforms.

Tax administrations are facing a raft of issues in supporting and responding to this growth in cross-border activity, including how they manage taxpayer information flows across borders. Previous editions of the tax administration series (OECD, 2019[1]) highlighted two international measures aimed at helping administrations to address these issues:

The European Union’s Electronic Identification Authentication and Trust Services (eIDAS) approach, which was introduced in 2014 and aims at increasing the confidence taxpayers and tax administrations can have in dealing with information flows and being able to manage identity and registration issues across borders.

The global standard on Automatic Exchange of Information (AEOI) – the Common Reporting Standard (CRS), which together with the United States Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) provides for the exchange of non-resident financial account information with the tax authorities in the account holders’ jurisdiction of tax residence.

Following the 2019 OECD report The Sharing and Gig Economy: Effective Taxation of Platform Sellers (OECD, 2019[5]), the OECD published in 2020 a set of Model Rules that set the framework for digital platforms to collect information on the income realised by those offering accommodation, transport and personal services through platforms and to report the information to tax authorities. A key objective for the Model Rules is to help taxpayers be compliant with their tax obligations, and to provide a consistent framework to help business provide information to tax authorities. This supports the Model Rules goal of streamlining reporting regimes for tax administrations and platform operators alike. (OECD, 2020[6])

Around the same time, the OECD Tax Administration 3.0 report (OECD, 2020[3]) identified the seamless taxation of platform sellers as a key action for multilateral collaboration. Work is currently ongoing to explore how co-operation between administrations and platforms can be deepened to explore the integration of identification and reporting processes into the applications used by the platforms in order to support tax compliance by platform sellers as well as reducing burdens for all parties.

More generally, common approaches to digital identity that are shared across government, and between government and third parties, will increasingly allow new services to be developed. These services can reduce burdens on taxpayers as third parties can supply information direct to tax administrations, as well as providing richer and more accurate pools of data to tax administrations.

Box 3.4. Netherlands – Trusted Information Partners

In the modern digital world, the need for qualified data and qualified data exchange is growing rapidly, and with that the receiver of data needs to determine the reliability of the data and be confident about the identity of the party. This is very important for the tax administration to improve and even guarantee the integrity of data.

Together with private and public parties the Netherlands Tax Administration (NTA) is creating an ecosystem that makes trusted, qualified information exchange possible. The ecosystem aims to provide standards to parties for implementing qualified, traceable, and secure data exchange. It ensures that the source and authenticity of the data are reliable, and thereby creates confidence in the data exchange for the parties involved. The goal is to make doing business digital, easy and reliable.

Source: Netherlands (2023).

References

[6] OECD (2020), Model Rules for Reporting by Platform Operators with respect to Sellers in the Sharing and Gig Economy, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/tax/exchange-of-tax-information/model-rules-for-reporting-by-platform-operators-with-respect-to-sellers-in-the-sharing-and-gig-economy.htm (accessed on 22 May 2023).

[3] OECD (2020), Tax Administration 3.0: The Digital Transformation of Tax Administration, https://www.oecd.org/tax/forum-on-tax-administration/publications-and-products/tax-administration-3-0-the-digital-transformation-of-tax-administration.htm (accessed on 22 May 2023).

[4] OECD (2020), “Tax administration responses to COVID-19: Assisting wider government”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/0dc51664-en.

[1] OECD (2019), Tax Administration 2019: Comparative Information on OECD and other Advanced and Emerging Economies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/74d162b6-en.

[5] OECD (2019), The Sharing and Gig Economy: Effective Taxation of Platform Sellers : Forum on Tax Administration, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/574b61f8-en.

[2] OECD (2017), Tax Administration 2017: Comparative Information on OECD and Other Advanced and Emerging Economies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/tax_admin-2017-en.