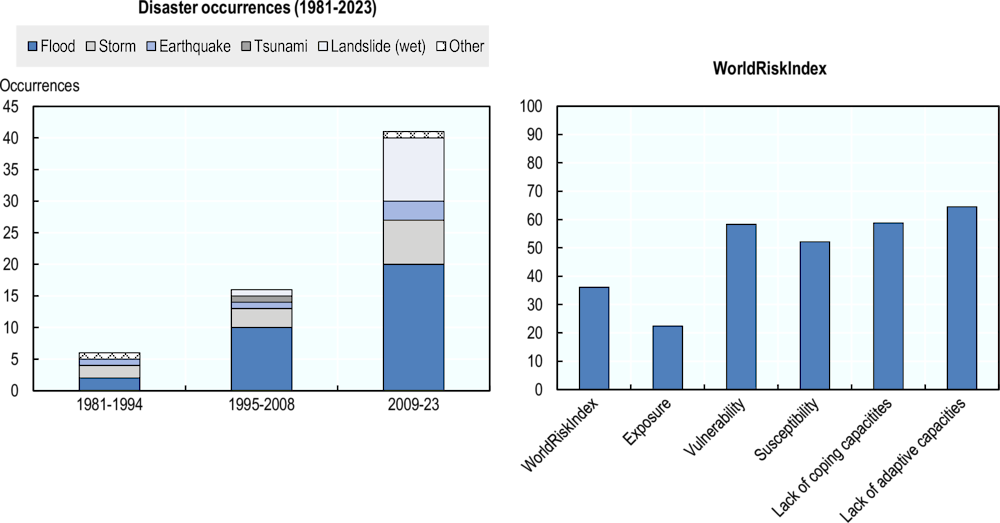

Myanmar is among the world’s most disaster-prone countries. It faces frequent floods, droughts, tropical cyclones and landslides, and is also exposed to other natural hazards including earthquakes, tsunamis and wildfires (NDMC, 2017[1]). Myanmar faces 6th-highest disaster risk, according to the WorldRiskIndex 2023. Another organisation, the Global Climate Risk Index, ranked Myanmar second among countries most affected by extreme weather events in the last two decades (Germanwatch, 2019[2]). The disaster risk in Myanmar is characterised by a high level of natural hazards and exposure, high vulnerability and a lack of coping capacities. Between 2000 and 2023, 55 disasters triggered by natural hazards led to over 140 000 deaths, affected more than 7.5 million other people and caused nearly USD 7 billion in economic damages (CRED, 2024[3]).

Economic Outlook for Southeast Asia, China and India 2024

Myanmar

Introduction

Myanmar: Disaster occurrences (from 1981 to 2023) and WorldRiskIndex

The hazardscape

The most frequent natural hazards in Myanmar are floods (49%), landslides (22%), storms (18%), and earthquakes (7%), with floods and storms being the most impactful with respect to the number of people affected. Disasters caused by natural hazards inflict significant social and economic impacts in the country. Average annual expected disaster losses amount to 0.9% of the country’s GDP (World Bank, 2012[4]). In 2008, Cyclone Nargis, one of the deadliest cyclones in recorded history and the most impactful disaster event on record in Myanmar, led to 140 000 deaths, affected 2.4 million people and caused more than USD 4 billion in economic damage and losses (GFDRR, 2022[5]; UNDRR, 2012[6]). In 2015, severe floods displaced approximately 1.6 million people, while economic damage and losses exceeded USD 1.5 billion (World Bank, 2015[7]). In addition to such large-scale disaster events, the cumulative impact of small-scale and recurrent events is also significant. The prevalence of natural hazards severely threatens the country’s economic development via disruptions in economic activity following the loss of livelihoods and infrastructure, and because of the costs associated with reconstruction and recovery. Disasters are a significant contributing factor to people’s inability to escape poverty and to low labour-force participation and financial exclusion of women (NDMC, 2017[1]).

Climate change perspective

Myanmar’s disaster vulnerability is exacerbated by inadequate development and high poverty rates, with a quarter of the population living below the poverty line. Rural vulnerability is especially high, as rural populations have significantly higher poverty rates (38%) than the urban populations (14.5%) and are largely reliant on climate-sensitive activities such as subsistence agriculture (World Bank, 2017[8]). Myanmar is still heavily dependent on the agricultural sector, which contributed approximately 22% to the country’s GDP in 2022 and is disproportionately vulnerable to extreme weather events (World Bank, n.d.[9]). Other factors linked to high vulnerability include poor infrastructure, gender inequality, unplanned urbanisation and a lack of access to financial services (NDMC, 2016[10]).

Climate change is expected to increase the risk of floods, storms and droughts, which may consequently affect the risks associated with landslides and wildfires. Furthermore, sea level rise is threatening the livelihoods and economic activity along the coast through higher tides and storm surges, damage to infrastructure, and salinisation of soil and water resources (Oo, Huylenbroeck and Speelman, 2018[11]).

Challenges for disaster risk management policy

The National Disaster Management Committee (NDMC) released Myanmar Action Plan on Disaster Risk Reduction, 2017” designed a comprehensive disaster risk management plan with the help of the UNDP and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Finland. The plan was specifically called “integrated” and takes a very similar approach to what this publication calls “holistic”. Notably, the plan identifies several challenges to each objective and proposes solutions to them (NDMC, 2017[1]). Nonetheless, disaster risk management remains highly centralised in Myanmar. A shift towards local-level implementation would allow for authorities to optimise policy for local contexts, while central policy formulation and clear response hierarchy would provide a foundation for policy co‑ordination and response support.

At the community and household level, disaster resilience and preparedness could be improved by various measures including education on first aid, improving mobile phone infrastructure for communication during a disaster, and involvement of public buildings as shelters in disaster response (Heinkel et al., 2022[12]). Risk awareness could be improved by emergency day events, media campaigns and other awareness programmes (Soe et al., 2021[13]). These programmes should be aimed at risk management institutions, the private sector, the civil society, and the general public. Maps of public buildings should be developed, shelter management training conducted, and escape routes and evacuation sites established (Than, Kyi and Kraas, 2020[14]). Myanmar’s earthquake disaster plan (the National Earthquake Preparedness and Response Plan) should be updated to include considerations for infrastructure management including water supply and electricity (Inoue, Numada and Meguro, 2020[15]).

The central government has increased its efforts to improve financial resilience, having established a National Disaster Management Fund and allocated a contingency budget for relief and recovery. However, the budgetary provisions to meet post-disaster financing needs are inadequate. Severe funding gaps remain, with the country relying on international assistance especially in the case of major disaster events. Potential steps to improve Myanmar’s disaster risk financing include improved assessments of available financing instruments, the establishment of additional sources of rapid emergency response funding, the development of contingent financing mechanisms, the utilisation of existing social protection schemes for distribution of financial aid and the introduction of public asset insurance (World Bank, 2017[16]).

References

[3] CRED (2024), EM-DAT, The International Disaster Database, https://www.emdat.be (accessed on 12 December 2023).

[2] Germanwatch (2019), Global Climate Risk Index 2020, https://www.germanwatch.org/en/17307.

[5] GFDRR (2022), Myanmar – 2008 – PDNA undertaken after Cyclone Nargis killed 84,537 people, https://www.gfdrr.org/en/myanmar-2008-pdna-undertaken-after-cyclone-nargis-killed-84537-people.

[12] Heinkel, S. et al. (2022), “Disaster preparedness and resilience at household level in Yangon, Myanmar”, Natural Hazards, Vol. 112/2, pp. 1273-1294, Springer Science and Business Media LLC, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-022-05226-w.

[15] Inoue, M., M. Numada and K. Meguro (2020), Comparative Analysis with Topic Model on National Disaster Management Plan in Myanmar, https://wcee.nicee.org/wcee/article/17WCEE/6f-0005.pdf.

[1] NDMC (2017), Myanmar Action Plan on Disaster Risk Reduction, 2017: Fostering resilient development through integrated action plan, https://themimu.info/sites/themimu.info/files/documents/Core_Doc_Myanmar_Action_Plan_on_Disaster_Risk_Reduction_2017.PDF.

[10] NDMC (2016), Myanmar National Framework for Community Disaster Resilience, https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/mya168037.pdf.

[11] Oo, A., G. Huylenbroeck and S. Speelman (2018), “Assessment of climate change vulnerability of farm households in Pyapon District, a delta region in Myanmar”, International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, Vol. 28, pp. 10-21, Elsevier BV, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2018.02.012.

[13] Soe, K. et al. (2021), “Cyclone risk preparedness and response in Rakhine State, Myanmar: institutional based analysis”, Journal of the Myanmar Academy of Arts and Science, Vol. 19/5B, pp. 89-99, https://www.maas.edu.mm/Research/download_details.php?id=1740.

[14] Than, Z., T. Kyi and F. Kraas (2020), “Institutional preparedness for multiple risks in Yangon, Myanmar”, Journal of the Myanmar Academy of Arts and Science, Vol. 18/5B, pp. 61-74.

[6] UNDRR (2012), Reducing Vulnerability and Exposure to Disasters: The Asia-Pacific Disaster Report 2012, https://www.undrr.org/publication/reducing-vulnerability-and-exposure-disasters-asia-pacific-disaster-report-2012.

[16] World Bank (2017), Disaster Risk Finance Country Diagnostic Note: Myanmar, https://www.financialprotectionforum.org/sites/default/files/DRFI_Myanmar_0.pdf.

[8] World Bank (2017), Myanmar poverty assessment 2017: Part two, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/myanmar/publication/myanmar-poverty-assessment-2017-part-two#:~:text=Part%20two%20of%20the%20report,the%20consumption%20aggregate%20for%20Myanmar.

[7] World Bank (2015), Myanmar - Post-disaster needs assessment of floods and landslides : July - September 2015, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/646661467990966084/Myanmar-Post-disaster-needs-assessment-of-floods-and-landslides-July-September-2015.

[4] World Bank (2012), Advancing Disaster Risk Financing and Insurance in ASEAN Member States: Framework and Options for Implementation, https://www.gfdrr.org/sites/default/files/publication/DRFI_ASEAN_REPORT_June12.pdf.

[9] World Bank (n.d.), Agriculture, forestry, and fishing, value added (% of GDP), https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NV.AGR.TOTL.ZS (accessed on 22 February 2024).