This chapter reviews the policy landscape related to the circular economy in Italy. It details the policy framework in the European Union, including quantitative targets related to waste and the circular economy. Then, it outlines the national policy and legislative framework and provides key information on the National Strategy for the Circular Economy and the National Waste Management Plan, both adopted in 2022. The chapter also details responsibilities on the design, implementation and enforcement of economic instruments across various levels of government, providing a basis for the policy recommendations developed in the following chapters.

Economic Instruments for the Circular Economy in Italy

3. Policy and legislative review

Copy link to 3. Policy and legislative reviewAbstract

3.1. Introduction

Copy link to 3.1. IntroductionPrinciples of resource efficiency and the circular economy have received increased attention from the highest levels of government of many OECD countries. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development includes references to resource efficiency, notably SDG 12: Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns. Italy has played a central role in the promotion of circular economy concepts at the international level, including with the adoption of the G7 Bologna Roadmap in 20171 and the G20 Environment Communiqué signed in Naples in 2021 (G7 Alliance on Resource Efficiency, 2017[1]; G20 Leaders, 2021[2]).

More recently, the issue of plastic pollution has gained prominence as a policy priority at the domestic and international level. The United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA) Resolution 5/14 entitled End plastic pollution: Towards an international legally binding instrument, adopted in March 2022, mandated the development of an international, legally binding instrument on plastic pollution based on a comprehensive approach that addresses the full life cycle of plastics. Previous international commitments include the G20 Osaka Blue Ocean Vision (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan, 2019[3]) and the G20 Rome Leaders’ Declaration (G20 Leaders, 2021[2]).

3.2. EU policy framework

Copy link to 3.2. EU policy frameworkThe European Union has made the transition to a circular economy one of its priority policy areas. The first Circular Economy Action Plan was adopted in 2015 (European Commission, 2015[4]) and the second in 2020 (European Commission, 2020[5]). The New Circular Economy Action Plan of 2020 is considered a key means to deliver on the European Green Deal and achieve carbon neutrality. Among the priorities are sustainable production, interventions to empower consumers and public buyers to make greener choices, measures implemented in resource-intensive sectors with high potential for circularity (electronics and information and communications technologies, batteries and vehicles, packaging, plastics, textiles, construction and food), improvements in the waste management sector, greener efforts at the international level, and an update of the circular economy monitoring framework.

The Waste Framework Directive (WFD)2 is the main regulation on waste in Europe. It establishes a common legal framework for treating waste that is designed to protect the environment and human health. It emphasises the principle of the waste hierarchy: to prioritise waste prevention, followed by its reuse, recycling and composting, and energy recovery, with landfilling only as the last resort. The WFD has set a target of 55% for the preparation of municipal waste for reuse and recycling by 2025, 60% by 2030 and 65% by 2035. It also establishes the basic requirements for Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR).

In addition, the Packaging and Packaging Waste Directive (PPWD) lays down measures to prevent the production of packaging waste, and to promote the reuse of packaging and recycling, and other forms of recovering packaging waste. The PPWD sets qualitative and quantitative targets that all packaging placed on the EU market must meet, as well as objectives for the use of economic incentives. Expected revisions to the PPWD (provisionally agreed by the Parliament and Council on 4 March 2024) aim to reinforce requirements for all packaging to be reusable and recyclable by 2030, including through mandatory reuse and refill targets in certain sectors, and to boost the uptake of recycled content and further promote packaging waste prevention.

Table 3.1 presents key EU targets and restrictions related to waste prevention and management.

Table 3.1. Summary of EU targets in the area of waste management

Copy link to Table 3.1. Summary of EU targets in the area of waste management|

Area |

Target |

Relevant EU Directive |

|---|---|---|

|

Municipal waste management |

Preparing for reuse and recycling rate of municipal waste: At least 55% by 2025, 50% by 2030 and 65% by 2035 (by weight) |

Waste Framework Directive |

|

Mandatory separate collection of textiles and household hazardous waste (by January 2025)1 |

||

|

Mandatory separate collection (or recycling at source) of bio-waste |

||

|

Landfilling of waste |

Share of municipal waste that is landfilled: maximum 10% by 2035 |

Landfill Directive |

|

Ban on the landfilling of waste suitable for recycling or other materials or energy recovery (from 2030) |

||

|

Packaging waste |

Recycling rate for packaging waste, all materials: 65% by 2025 (70% by 2030) Paper and cardboard: 75% by 2025 (85% by 2030) Ferrous metals: 70% (80%); Aluminum: 50% (60%) Glass: 70% (75%) Plastic: 50% (55%) Wood: 25% (30%) |

Packaging and Packaging Waste Directive |

|

Mandatory producer responsibility schemes for all packaging |

||

|

The revised PPWD would bring changes that include: Reuse and refill targets to 2030 and 2040 Mandatory deposit return systems (DRS) to ensure the separate collection of at least 90% of single-use plastic bottles and metal beverage containers, by 2029 (possibility of exemption for countries who still achieve the 90% separate collection target) |

||

|

End-of-life vehicles |

Reuse, recovery and recycling targets Minimum of 95% of reuse and recovery (by weight, per vehicle) by 2015 Minimum of 85% of recycling (by weight, per vehicle) by 2015 |

End-of-Life Vehicles Directive |

|

Batteries and accumulators |

Minimum rate of separate collection: 45% by 2016 |

Batteries Directive |

|

Electrical and electronic equipment (EEE) |

Minimum rate of separate collection: 65% of the average weight of EEE placed on the market in the 3 preceding years in the member state, or 85% of WEEE generated on the territory of the member state |

Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment Directive |

1. Italy mandated the establishment of separate collection systems for household textiles as of January 2022 (Leg. Decree 2020/116).

Sources: Directive EU 2018/851 amending Directive 2008/98/EC on waste, Directive (EU) 2018/850 amending Directive 1999/31/EC on the landfill of waste, Directive (EU) 2018/852 amending Directive 94/62/EC on packaging and packaging waste, Directive (EU) 2018/849 amending Directive 2000/53/EC on end-of-life vehicles, Directive 2006/66/EC on batteries and accumulators and waste batteries and accumulators, Directive 2012/19/EU on waste from electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE).

Table 3.2. EU quantitative targets for plastics

Copy link to Table 3.2. EU quantitative targets for plastics|

Area |

Targets |

Time frame |

|---|---|---|

|

Separate waste collection of plastic bottles |

Separately collect 77% (90%) of plastic bottles placed on the market in a given year (by weight). |

By 2025 (by 2029) |

|

Secondary raw materials use |

Incorporate 25% of recycled plastic in the manufacture of PET beverage bottles from 2025, and 30% in all plastic beverage bottles as from 2030 |

By 2025, 2030 |

Source: Single-Use Plastics Directive

The Directive on Single-Use Plastics (SUP Directive)3 aims to reduce the volume of single-use plastic products, as well as their impacts on the environment and human health. Applications targeted by the SUP Directive are single-use plastic bags, food and beverage containers, cutlery, plates and straws, cotton bud sticks and cigarette butts. The SUP bans single-use plastic products where sustainable alternatives are available and affordable (e.g. cutlery, cotton bud sticks). In other cases, design requirements, awareness-raising measures, labelling requirements, and waste management and clean-up obligations for producers shall contribute to consumption reductions. Additionally, the SUP Directive sets targets for minimum recycled content in PET bottles and the separate collection of plastic bottles (Table 3.2). Additionally, a “plastics own resource” entered into force in January 2021 in the form of contributions to the EU budget. Member states shall contribute EUR 0.80 per kilogram of plastic packaging that is not recycled at end of life.

On 30 March 2022, the European Commission presented a package of Green Deal proposals to make sustainable products the norm in the EU. Among these, the proposed Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation will establish a framework to set eco-design requirements for selected product groups to improve their circularity, sustainability and energy performance. The proposal builds on the existing Ecodesign Directive,4 but it extends the scope to include the broadest possible range of products and eco-design requirements, including on product durability, reusability, upgradability and reparability, the presence of substances that inhibit circularity, energy efficiency, recycled content, recyclability, carbon and environmental footprints, and information requirements (including a Digital Product Passport).

Targeted sectorial initiatives promote the transition in select priority sectors, such as the EU Strategy for Sustainable and Circular Textiles (European Commission, 2022[6]), EU rules on packaging and packaging waste (European Commission, 2023[7]), and the revision of regulations on Construction Products5 and Batteries.6 Furthermore, a series of economic incentives for sustainable production and consumption are being updated, including green public procurement (GPP) criteria.

The deployment of sustainable products is supported by a series of other initiatives and tools. The EU Ecolabel7 is the EU’s voluntary environmental labelling scheme assigned to products that respect a set of environmental criteria that promote lower waste generation and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The proposed Sustainable Products Regulation aims to extend the Ecolabel to additional products and services, and to render it less costly and bureaucratic. The new regulation would introduce mandatory labelling to indicate relevant environmental parameters for a wide range of products. Additionally, the proposed Green Claims Directive8 would require companies to substantiate the voluntary green claims they make in business-to-consumer commercial practices, that is, to prevent “greenwashing”. To support companies in reducing the environmental impacts of their practices, the EU has created tools, such as the EU Product Environmental Footprint (PEF) method, which provides a harmonised methodology to measure the environmental impacts of the life cycle of products and services,9 and the Eco-Management and Audit Scheme (EMAS), which is the environmental management instrument developed for companies and other organisations to evaluate, report and improve their environmental performance.

The recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic has offered unprecedented opportunities to accelerate green investments. The Recovery Plan for Europe, established by the Multiannual Financial Framework 2021-2027 and the NextGenerationEU Fund, is the largest stimulus package ever financed in Europe. It reinforces the direction outlined in the European Green Deal, with 20% of funds dedicated to natural resources and the environment, and 30% to climate. To benefit from recovery funds, EU Member States have submitted national Recovery and Resilience Plans (RRPs) consistent with European objectives: at least 37% of spending should fund investments and reforms that support climate objectives, while the rest should respect the principle of “do-no-significant harm”. In addition, the Taxonomy Regulation,10 approved in June 2020, established the basis for the “EU taxonomy”, which sets out the overarching conditions that determine whether an economic activity can qualify as environmentally sustainable. The EU taxonomy can play a pivotal role in directing investments towards projects and activities that are sustainable and that contribute to increasing resilience against climate and environmental shocks.

3.3. National policy and legislative framework

Copy link to 3.3. National policy and legislative frameworkIn recent years, Italy has consolidated its national policy framework around resource efficiency and the circular economy. The National Strategy for the Circular Economy, adopted in June 2022, sets out the long-term ambition for the transition to a circular economy and defines precise objectives to accomplish it. The strategy recognises the essential role that transitioning to a circular economy could play in helping the country achieve the transition to a sustainable and low-carbon economy. It envisions reductions in GHG emissions, improved management of natural resources, and a reduction in the overall use of non-renewable resources. It also recognises the economic and social benefits that the transition could deliver, including less dependence on the imports of raw materials, greater competitiveness of the Italian manufacturing sector and the Italian economy as a whole, and a positive effect on employment.

Also in June 2022, Italy adopted the National Waste Management Plan (Programma Nazionale per la Gestione dei Rifiuti), as envisaged by the WFD and Italy’s National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP, see Box 3.1). The National Waste Management Plan defines the medium- and long-term objectives, criteria and strategic guidelines for the development of regional waste management plans (“Piani Regionali di Gestione dei Rifiuti”) to ensure that waste management policies are aligned with EU Directives and across all levels of government. The actions outlined primarily aim to bridge infrastructural and planning gaps that exist across various regions in the area of waste management and recycling (in line with sustainability, efficiency and cost-effectiveness criteria, and with the principles of self-sufficiency and proximity), to guarantee the achievement of targets on waste prevention, to prepare for reuse, recycling and recovery, and to ensure traceability of waste. The document also includes a national plan for communication and awareness-raising on waste and the circular economy.

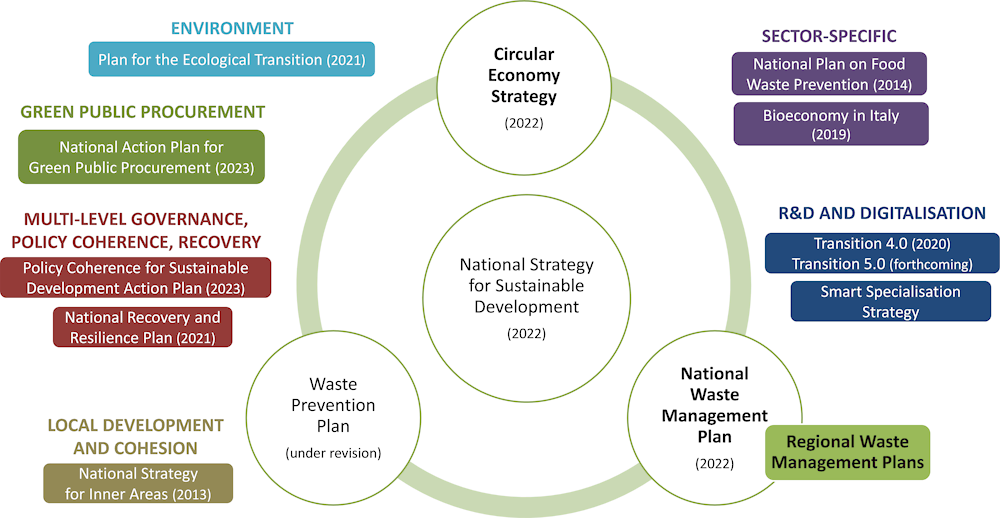

As illustrated in Figure 3.1, the National Strategy for Sustainable Development sets out the overall framework, vision and objectives for public policies in the area of environment and local development, in line with the implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Figure 3.1. Overview of the Italian policy framework related to the circular economy

Copy link to Figure 3.1. Overview of the Italian policy framework related to the circular economy

Note: Text in brackets indicate the year of last update or information on the current status.

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

The National Strategy for the Circular Economy envisions action on a comprehensive set of themes related to the circular economy, which are summarised in Table 3.3. The strategy highlights the need to strengthen markets for secondary raw materials and other recovered materials to render them competitive in terms of availability, performance and cost compared to virgin raw materials (MiTE, 2022[8]). To achieve this, the strategy aims to bolster measures to support the use of recycled and recovered materials, including defining end-of-waste criteria, a greater use of EPR and green public procurement (GPP) strategies, and an overall strengthening of fiscal incentives.

Table 3.3. Key themes in the Italian Circular Economy Strategy

Copy link to Table 3.3. Key themes in the Italian Circular Economy Strategy|

Eco-design |

Reuse and repair |

End-of-waste |

Critical raw materials, markets for secondary raw materials |

Green public procurement |

Strategic value chains |

Industrial symbiosis |

Extended producer responsibility |

Digitalisation |

Measures in support of the circular economy |

Source: Adapted from (MiTE, 2022[8]).

Italy’s Strategy for the Circular Economy outlines a roadmap of horizontal initiatives and actions to support the circular economy that includes an emphasis on economic and fiscal instruments, as well as foreseen improvements in the legislative framework related to the circular economy and interventions to influence consumer behaviour. The roadmap for the implementation of the Strategy (“Cronoprogramma di attuazione delle misure della Strategia Nazionale per l’Economia Circolare”), also adopted in 2022, sets out a roadmap of implementation measures for the period 2022-2025. Among other measures, the roadmap foresees:

The removal of environmentally harmful subsidies related to waste and a reform of the landfill tax.

Renewed tax credits in support of recycled (and other recovered) materials.

New financial instruments that promote and reward sustainability and circularity.

Greater progress in the use of GPP, including the definition of additional GPP criteria, support for reuse and repair, and improved uptake and monitoring.

Strengthening the principle of EPR, including its extension to sectors such as textiles and non-packaging plastics, and the introduction of a supervisory body for producer responsibility organisations.

Support for industrial symbiosis projects, including financial support and the removal of regulatory barriers.

Box 3.1. The contribution of Italy’s Recovery and Resilience Plan to the circular economy

Copy link to Box 3.1. The contribution of Italy’s Recovery and Resilience Plan to the circular economyItaly’s National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP) envisioned a number of interventions to support the circular economy. These include the definition of a National Strategy for the Circular Economy and a National Waste Management Plan, both adopted in June 2022, as well as better technical support for local entities to develop the waste management infrastructure and an Action Plan to support the broader uptake of GPP criteria by public entities.

The NRRP allocated EUR 2.1 billion to investments related to the circular economy (corresponding to 3% of total funds). The majority (EUR 1.5 billion) was earmarked for the construction and modernisation of waste treatment and recycling infrastructure that would bridge the infrastructural gaps between regions. The remainder (EUR 600 million) was earmarked for flagship projects focused on the recycling of specific material flows, such as waste from electrical and electronic equipment, plastics, paper and textiles. The NRRP also called for additional technical support for local public entities to overcome opposition to waste treatment and recycling infrastructure, as well as easier authorization of new waste recycling infrastructure. The so-called “Semplificazioni” Decree sets forth regulatory changes to simplify procedures authorising new infrastructure, including the reduction of environmental impact assessments of NRPP projects to 130 days and simplified administrative procedures.

Source: (Italian Government, 2021[9]).

Italy has a comprehensive legislative framework related to waste and the circular economy.11 In recent years, it has been updated multiple times to align with EU Directives and to gradually introduce measures related to the circular economy.12 Beyond the adoption of EU objectives and targets, the transposition of the WFD and the Landfill Directive led to substantial changes to the regulatory framework around waste and packaging. Italy’s legislative framework also includes measures against the illegal dumping of waste and littering.13

An important recent change is the establishment of a National Electronic Registry for Waste Traceability (RENTRi) to replace the previous waste tracking system. RENTRi will provide the digitalization of all the documents relating to the handling and transport of waste. The traceability system will support the control authorities in preventing and combating illegal waste management, while addressing the needs of businesses (e.g. for simplification, streamlining of procedures, clarity and predictability of rules).

The legislation on EPR schemes was also revised multiple times, including to introduce minimum requirements for national EPR schemes, facilitate administrative procedures for the establishment of EPR schemes for additional product groups, and establish the National Register of Producers to help monitor compliance with EPR obligations. Italy’s legislation also foresees labelling requirements for certain types of packaging to facilitate collection, sorting and recycling.

In recent years, specific attention has been paid to overcoming long-standing regulatory barriers that hinder initiatives geared towards the achievement of a circular economy, including the definition of end-of-waste (EoW) criteria. According to the WFD, waste ceases to be classified as waste and becomes secondary raw materials, but only when they comply with specific technical requirements set out by EoW criteria. The definition of EoW criteria is the responsibility of the European Union or, in the absence of common criteria for specific waste streams, individual Member States14. While EU EoW criteria exist for three product groups (scrap metal, glass cullet and copper scrap), Italy has approved EoW criteria for solid recovered fuels, reclaimed asphalt pavement, waste from absorbent hygienic products, crumb rubber from end-of-life tyres, paper and cardboard waste, and construction and demolition (CDW) waste. Legislation defining EoW criteria constitutes a fundamental step towards material recovery, creating new opportunities for material and value retention, and facilitating innovation in production processes.

Legislation on by-products also plays a crucial role in the circular economy transition. As defined by the WFD, a by-product is a substance or object resulting from a production process, the primary aim of which is not its production, and that it is used as a secondary raw material in new production processes without needing further processing other than normal industrial practice. Examples of by-products are materials resulting from production processes in the agri-food sector (e.g. fruit pits), or residues from plastics processing.

3.3.1. Competencies on waste, the circular economy and related economic instruments

Copy link to 3.3.1. Competencies on waste, the circular economy and related economic instrumentsIn recent decades, Italy’s environmental management system has evolved towards greater decentralisation (OECD, 2013[10]). Italy is a regionalised unitary state with three tiers of local government, including 20 regions15, 107 intermediary governments (i.e. provinces, metropolitan cities and autonomous provinces) and 7901 municipalities (ISTAT, 2023[11]). Administrative and fiscal responsibilities have progressively shifted from the central government to the sub-national level (OECD, 2017[12]; Bulman, 2021[13]). Sub-national governments hold important roles in key expenditure areas, spending 29% of total public expenditure in 2014 and making 55% of total public investment (OECD, 2017[12]).

In the area of waste management and prevention, the national government holds a co-ordination and guiding role, while regions and municipalities hold planning and financing roles.16 The Ministry of Environment and Energy Security (MASE) is responsible for waste management supervision and control. MASE also leads on the development of the National Strategy for the Circular Economy and the National Waste Management Plan, in collaboration with other agencies. Sub-national levels of government play key roles in the promotion of the circular economy transition. All regions oversee planning for waste management and prevention and must develop and regularly update their regional waste management plans and waste prevention plans so that they are aligned with the overall guiding principles and objectives set out in national policy documents. Regions are also responsible for the collection of data on waste generation and disposal and for the identification of current and projected infrastructural needs. Regions hold powers to i) regulate waste management, including the separate collection of municipal waste; ii) promote waste prevention and integrated waste management; and iii) authorise waste disposal and recovery operations. Several regions have developed specific strategies and targeted measures in the areas of sustainable development and the transition to a circular economy, as presented in Box 3.2 for the case of Emilia-Romagna.

Local authorities hold operational roles, notably for waste collection and management. Municipalities assess existing infrastructure and define the local waste management plan, specifying the organisational model and the financial plan in place. They award municipal waste management services through dedicated tenders. Some cities have adopted circular economy strategies; one example is the “Prato Circular City strategy” of the city of Prato.17 The Pact for Circular Economy, already signed by Bari, Milan, Prato and MASE, creates a network to support the implementation of actions for the circular transition at the local level (Alternativa Sostenibile, 2018[14]).

As a consequence of this decentralised system, several levels of government influence the design, implementation and enforcement of economic instruments related to the circular economy, as summarised in Table 3.4. Generally, fiscal instruments are introduced at the national level, but regions oversee their implementation. Sub-national levels of government generally collect and manage revenues.

Extractive activities are not regulated nationally (with the exception of Royal Decree 29 July 1927 nº 1443, not updated recently). Presidential Decree 616/1977 transferred administrative functions relating to quarrying activities to the regions, which was followed by a wave of regional laws to regulate the sector. Decisions on the fee coverage, rate and use of revenues are taken at the sub-national level. The regulation of extractive activities varies widely across the regions.

For the landfill tax, regions have authority on three important aspects: the tax rate, the types of waste subject to tax, and the allocation of tax revenues. National legislation sets the upper and lower limits for different waste typologies.

With regard to household waste charges, municipalities set fees based on national guidelines developed by the Regulatory Authority for Energy, Networks and the Environment (ARERA). Municipalities may provide reductions in the waste tax rate to companies that donate surplus food and other goods, helping to prevent waste. Furthermore, regions may encourage municipalities to implement pay-as-you-throw (PAYT) systems, which link charges to the amount of waste generated by households.

The ANCI-CONAI Framework Agreement is a core piece of legislation regarding waste collection and management in Italy. Introduced by the so-called Ronchi Decree of 1997, and subsequently Legislative Decree 152/06, it is a framework that guarantees that the EPR system covers the financial and operational costs of separate collection of packaging waste for municipalities. Municipalities that have implemented separate collection for each type of packaging waste may choose to sign the relative convention, according to the methods set forth in the relative technical annex of the Framework Agreement (updated every five years). By signing the convention, the municipality undertakes to deliver the packaging waste to the relative consortium, while the latter undertakes to collect the material, guarantee its subsequent recycling, and deliver fees based on the quality and quantity of the material provided (CONAI, 2023[15]).

MASE plays an important role in supervising, controlling and implementing support for EPR and GPP. On EPR, MASE is in charge of collecting and verifying the robustness and provenance of data, analysing and highlighting possible anomalies, monitoring the achievement of the targets, and verifying its proper implementation. On GPP, MASE is responsible for the definition and update of minimum environmental criteria (CAM), the application of which is mandatory in Italy since 2016 at all levels of government, and it is in charge of updating the National Action Plan on GPP. Monitoring of CAM uptake in GPP has been entrusted to the National Anti-Corruption Authority (ANAC).

Table 3.4. Overview of roles and responsibilities of selected economic instruments in Italy

Copy link to Table 3.4. Overview of roles and responsibilities of selected economic instruments in Italy|

Instrument |

National level |

Sub-national level |

|---|---|---|

|

Price-based economic instruments |

||

|

Fees on extractive activities |

National legislation only covers general matters in extractive sectors (e.g. workers’ health and safety, disposal of waste from extractive activities). |

Regions’ main responsibilities for minerals and quarrying (not energy-related minerals) include planning and authorisation of extractive activities, environmental impact assessments, setting of royalty fee coverage and rate, recovery of waste materials, mine/quarry closure and rehabilitation requirements, collection of statistical data. Municipalities: collection of revenues (exceptionally by regions). |

|

Landfill tax |

National legislation: general criteria and guidelines on tax scope (upper and minimum levels of tax rates), destination and earmarking of revenues (e.g. 5-10% of revenues shall go to municipalities). |

Regions main responsibilities include tax scope and tax rate (including reduced tax rates), collection of revenues (e.g. exact share going to municipalities, including with bonus/malus systems), use of revenues. Municipalities: may receive a share of revenues. |

|

Plastic tax |

National legislation (due to enter into force on 1 July 2024). |

NA |

|

Waste charge (including PAYT) |

National legislation: guidelines for fee setting. ARERA is the regulatory body. |

Regions: promotion or mandating adoption of PAYT systems. Municipalities: in charge of planning for local waste management (incl. the financing model), fee setting (incl. granting tax reductions in line with national guidelines) and collection of revenue. |

|

Performance-based economic instruments |

||

|

Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) |

State: introduction of EPR schemes, certification of Producer Responsibility Organisations (PROs/consortia). In most cases, PROs organise and execute EPR obligations nationally. |

N/A |

|

Green Public Procurement (GPP) |

National legislation: introduction of public procurement approaches and monitoring application of GPP criteria. MASE: definition and regular update of GPP criteria, update of National Action Plan on GPP Consip: National Central Purchasing Body implementing framework agreements, including GPP criteria. National Anti-Corruption Authority (ANAC): monitoring application of GPP criteria. |

Regional aggregators implementing framework agreements including GPP criteria and trainings on GPP. All sub-national public entities: implementation (uptake of GPP criteria in tenders). Regions participate in the planning phase (“Intesa Stato-Regioni” of the National Action Plan on GPP). |

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

Box 3.2. Sub-national policy and legislative framework in Emilia-Romagna

Copy link to Box 3.2. Sub-national policy and legislative framework in Emilia-RomagnaEmilia-Romagna was the first region to introduce circular economy principles and objectives into regional legislation and strategies. The Regional Law 16/2015 on Circular Economy mandated ambitious targets to 2020 on waste generation and separate collection. The Regional Waste Plan, approved in 2016, introduced measures to support the achievement of these targets, including: i) an Incentives Fund (partially funded by the regional landfill tax) to reward high-performing municipalities, and to incentivise waste prevention and reductions in waste generation; ii) public–private partnerships for the prevention and recovery of waste; iii) measures to promote reuse, including guidelines and the creation of municipal reuse centres; iv) the creation of permanent working groups on by-products and a dedicated regional register; and v) the development of a Circular Economy Forum, in the form of meetings and workshops, to disseminate guidance and information on ongoing regional initiatives related to the circular economy, as well as to engage with stakeholders and promote best practices (Ambiente Regione Emilia Romagna, n.d.[16]).

3.3.2. Multi-level governance and co-ordination mechanisms

Copy link to 3.3.2. Multi-level governance and co-ordination mechanismsA multi-level governance approach is fundamental to the circular economy. Generally, it encompasses two dimensions. The vertical dimension refers to the co-ordination across the national government, regions, provinces and municipalities, as well as capacity-building efforts at the sub-national level to improve the quality and coherence of public policy. The horizontal dimension refers to co-operation arrangements between regions or municipalities to improve the effectiveness of local public service delivery and the implementation of development strategies (Charbit, 2011[17]).

Some consultation and co-ordination mechanisms exist to enhance multi-level governance around the circular economy. For instance, an institutional working group (“Tavolo interistituzionale per il Piano della Gestione dei Rifiuti”) was set up to inform the development of the National Waste Management Plan. It aims to involve regions, government agencies (“Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale”, ISPRA), municipalities (“National Association of Italian Municipalities”, ANCI), the Ministry of Enterprises and Made in Italy (MIMIT), and ARERA.

In October 2022, MASE announced the establishment of an observatory tasked with co-ordinating and monitoring the implementation of the National Strategy for the Circular Economy (MiTE, 2022[18]). Once established, the observatory will be chaired and co-ordinated by MASE. with scientific and technical support provided by ISPRA and ENEA. Representatives from other ministries, as well as regions and municipalities, will also take part. The observatory is in charge of identifying any obstacles in the strategy’s implementation and ensuring dialogue with stakeholders by involving them in thematic roundtables and consultation on policy documents. Another key task will be to carry out effective communication and dissemination activities vis-à-vis the public administration, public and private operators and citizens to promote initiatives and achieve its objectives, providing guidance for any updates of the strategy’s timetable.

References

[14] Alternativa Sostenibile (2018), Città per la Circolarità: Bari, Milano e Prato verso un modello di economia circolare.

[16] Ambiente Regione Emilia Romagna (n.d.), Forum Economia circolare, https://ambiente.regione.emilia-romagna.it/it/rifiuti/temi/rifiuti/economia-circolare/forum-economia-circolare-1.

[13] Bulman, T. (2021), “Strengthening Italy’s public sector effectiveness”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD), https://doi.org/10.1787/823cad2a-en.

[17] Charbit, C. (2011), “Governance of Public Policies in Decentralised Contexts”, OECD Regional Development Working Papers, Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD), https://doi.org/10.1787/5kg883pkxkhc-en.

[15] CONAI (2023), Accordo quadro ANCI CONAI, http://www.conai.org/regioni-ed-enti-locali/accordo-quadro-anci-conai/.

[7] European Commission (2023), Packaging waste, https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/waste-and-recycling/packaging-waste_en (accessed on 24 April 2023).

[6] European Commission (2022), EU Strategy fo Sustainable and Circular Textiles.

[5] European Commission (2020), “A new Circular Economy Action Plan: For a cleaner and more competitive Europe”, COM/2020/98, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:9903b325-6388-11ea-b735-01aa75ed71a1.0017.02/DOC_1&format=PDF.

[4] European Commission (2015), Closing the loop - An EU action plan for the Circular Economy, http://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:8a8ef5e8-99a0-11e5-b3b7-01aa75ed71a1.0012.02/DOC_1&format=PDF (accessed on 16 November 2019).

[2] G20 Leaders (2021), G20 Rome Leaders’ Declaration, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/52730/g20-leaders-declaration-final.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2022).

[1] G7 Alliance on Resource Efficiency (2017), 5-Year Bologna Roadmap on Resource Efficiency, https://files.sitebuilder.name.tools/c1/87/c1876dff-eb9f-4d64-81f7-d28310736985.pdf.

[11] ISTAT (2023), Statistical codes of territorial administrative units: municipalities, metropolitan cities, provinces and regions, http://www.istat.it/it/archivio/6789#:~:text=Nota.,la%20soppressione%20di%20cinque%20comuni.

[9] Italian Government (2021), Piano Nazionale di Ripresa e Resilience (PNRR), https://italiadomani.gov.it/it/home.html (accessed on July 2022).

[3] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan (2019), “G20 Osaka Leaders Declaration”, G20 2019 Japan, https://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/economy/g20_summit/osaka19/en/documents/final_g20_osaka_leaders_declaration.html (accessed on 29 April 2022).

[18] MiTE (2022), Integrazione della composizione dell’Osservatorio per l’economia circolare, https://www.mite.gov.it/sites/default/files/untitled%20folder/dd_n_180_del_30_09_2022_istituzione_Osservatorio_per_l%E2%80%99Economia_Circolare.pdf.

[8] MiTE (2022), Strategia nazionale per l’economia circolare.

[20] OECD (2017), Environmental Fiscal Reform: Progress, Prospects and Pitfalls, OECD Report for the G7 Environment Ministers, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/tax/environmental-fiscal-reform-progress-prospects-and-pitfalls.htm.

[12] OECD (2017), Multi-level Governance Reforms: Overview of OECD Country Experiences, OECD Multi-level Governance Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264272866-en.

[10] OECD (2013), OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Italy 2013, OECD Environmental Performance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264186378-en.

[19] Prato Municipality (2022), Prato Circular City, https://www.comune.prato.it/it/scopri/buoneprassi/pcc/archivio42_0_74.html.

Notes

Copy link to Notes← 1. Previous OECD work on environmental fiscal reform (OECD, 2017[20]) fed into discussions at the Environment Ministerial Meeting held in Bologna on 11-12 June 2017.

← 2. Directive (EU) 2018/851 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 amending Directive 2008/98/EC on waste (Text with EEA relevance).

← 3. Directive (EU) 2019/904 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 June 2019 on the reduction of the impact of certain plastic products on the environment.

← 4. Directive 2009/125/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 October 2009 establishing a framework for the setting of eco-design requirements for energy-related products.

← 5. Proposal for a regulation laying down harmonised conditions for the marketing of construction products, amending Regulation (EU) 2019/1020 and repealing Regulation (EU) 305/2011.

← 6. Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council concerning batteries and waste batteries, repealing Directive 2006/66/EC and amending Regulation (EU) No 2019/1020.

← 7. Regulation (EC) No 66/2010 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 November 2009 on the EU Ecolabel; Regulation (EU) 2017/1369 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 4 July 2017 setting a framework for energy labelling and repealing Directive 2010/30/EU.

← 8. Proposal for a directive on substantiation and communication of explicit environmental claims (Green Claims Directive). In September 2023, the European Parliament and the European Council reached a provisional agreement on new rules to ban misleading labels and provide consumers with better product information. Once formally approved, EU Member States will have 24 months to incorporate the new rules into national law.

← 9. The EU has also developed an Organisation Environmental Footprint (OEF) to measure the environmental impacts of organisations.

← 10. Regulation (EU) 2020/852 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 June 2020 on the establishment of a framework to facilitate sustainable investment, and amending Regulation (EU) 2019/2088

← 11. The Environmental Consolidated Act (Leg. Decree 152/2006) governs a wide range of environmental issues in Italy, including waste prevention and management. It enshrines the EPR principle and the EU waste hierarchy into Italy’s environmental policy framework. It has been revised multiple times, including to transpose the 2018 circular economy package of directives.

← 12. Notably, the 2020 Budget Law kicked off Italy’s Green New Deal, a policy and investment plan to support the circular economy, including with the establishment of a EUR 4.24 billion fund (for the period 2020-2023) to promote the “Green Deal”.

← 13. The abandonment and uncontrolled deposit of waste is prohibited and punished with administrative and criminal sanctions (Leg. Decree 152/2006). Discarding cigarette butts and other very small waste items is prohibited and sanctioned by penalties ranging from EUR 30 to EUR 300 (Leg. Decree 152/2006 and Law 221/2015).

← 14. In Italy, the authority responsible for defining EoW criteria and granting authorisations has been a matter of debate. According to current legislation, EoW criteria are adopted at the national level. However, local authorities now have the competence to grant specific EoW authorisations on a “case by case” basis (Law 128/2019). A National Registry for Authorisations, established in November 2019, collects information on new authorisations, and also supports the definition of new EoW criteria and requests for control procedures.

← 15. In sustainable development governance, the first tier or government is often considered to refer to the 19 regions and 2 autonomous provinces that have regional powers.

← 16. Legislative Decree 152/2006 “Environmental Consolidated Act”.

← 17. The “Prato Circular City strategy” sets the following objectives: i) to promote the city's transition to the circular economy; ii) to strengthen the image of Prato as a “circular city”; iii) to establish an environment of permanent consultation among stakeholders in the area to promote shared, integrated and participatory circular economy actions; and iv) to create a circular city governance (Prato Municipality, 2022[19]).