The economic recession triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic is hitting African countries hard. Most of them are facing their first recession in 25 years: gross domestic product (GDP) growth will likely decrease in 41 of the 54 countries in 2020, according to an International Monetary Fund forecast (October 2020). By contrast, when the global financial crisis hit the continent in 2009, only 11 countries went into recession. The crisis has affected Africa’s growth through various external and domestic channels (Table 1). For example, the plunge in oil prices in the first quarter of 2020 has severely struck commodity-based economies. The shutdown of the global tourism industry, which employs 24.3 million people on the continent, has harshly affected tourism-dependent countries. Domestic demand and regional trade have suffered from confinement measures. At least 42 countries have imposed partial or full lockdowns on economic activities and the movements of people (UNECA, 2020). The crisis has also led to the postponement of the implementation phase of the African Continental Free Trade Area until 2021.

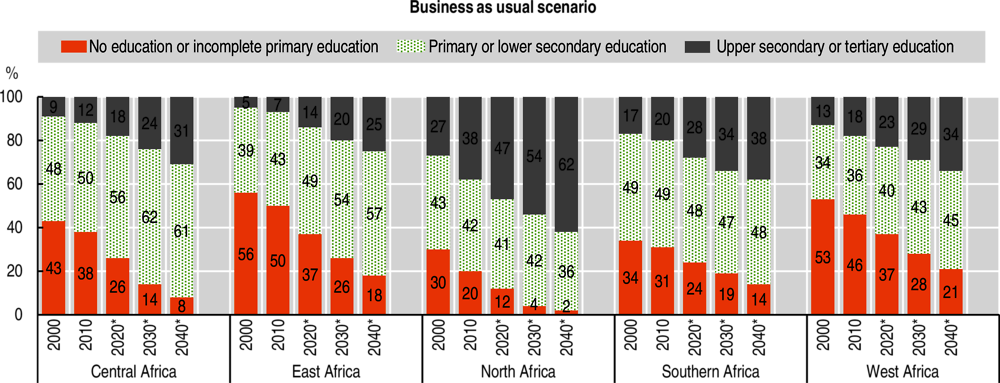

The global crisis is likely to derail Africa from its pre-COVID-19 development trajectory. The crisis could push some 23 million sub-Saharan Africans into extreme poverty in the course of 2020. Africa’s capital accumulation and productivity could remain below their pre-COVID 19 trajectories until 2030 (Djiofack, Dudu and Zeufack, 2020). The most consequential disruptions in national economies could be productivity decline, reduced capital utilisation and increased trade costs. Added to these are losses in educational achievement and health, which could hinder the ability of the current generation to earn higher incomes and improve its well-being. These disturbances will slow down Africa’s productive transformation and, consequently, the achievement of the African Union’s Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want.

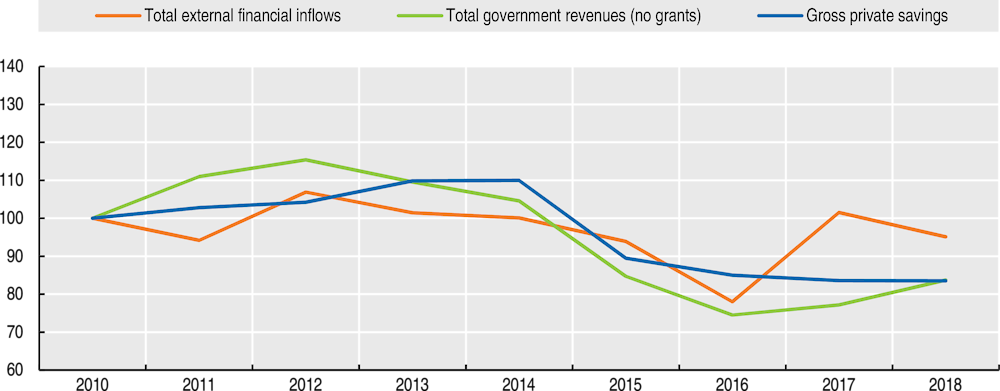

Africa’s governments are facing the COVID-19 pandemic with lower financial resources per capita than during the 2008 global financial crisis. The amount of financing per capita decreased during the 2010-18 period for both domestic revenues and external financial flows, by 18% and 5% respectively (Figure 1). On average, African countries had public revenues of USD 384 per capita in 2018, compared with USD 2 226 for countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, USD 1 314 for developing countries in Asia, and over USD 15 000 for European and other high-income countries. Tax-to-GDP ratios had already been stagnating at 17.2% since 2015 in 26 African countries, despite important tax reforms (OECD/ATAF/AUC, 2019).

Public revenue will contract even further. The ratio of tax to GDP should contract by about 10% in at least 22 African countries between 2019 and 2020; total national savings could drop by 18%, remittances by 25% and foreign direct investment (FDI) by 40%. Donors have pledged to maintain official development assistance (ODA) at their pre-crisis levels. However, fiscal deficits will probably double in 2020. As a result, Africa’s debt will likely soar to about 70% of GDP in current US dollars, up from 56.3% in 2019. While this average remains sustainable, the debt-to-GDP ratio is likely to exceed 100% of GDP in at least seven countries. The G20 debt moratorium that began in April 2020 provides necessary respite for African countries, but it remains insufficient. Suspending and, in some cases, restructuring the debt may prove necessary to free up critical resources to achieve the African Union’s Agenda 2063. Where possible, debt negotiations should include the growing group of private sector lenders (see Chapter 8). Finally, the COVID-19 crisis makes accelerating Africa’s productive transformation and continental integration processes all the more imperative.