This chapter analyses the dynamics of digitalisation in Africa and how it can create jobs for youth and fulfill Agenda 2063 in the context of the COVID-19 crisis. The first section examines the importance of digitalisation – the use of digital technologies and data and the interconnection that results in new activities or changes to existing activities − for Africa’s productive transformation and resilience to future crises. The second section documents the progress of digitalisation in Africa since the start of the mobile money revolution in 2007. Then it highlights the main channels through which digitalisation can create jobs. The third section identifies critical mismatches that require policy makers to act now, to accomodate the changes in Africa’s youth profiles by educational attainment. The final section of the chapter documents ongoing continental initiatives to promote Africa’s digital transformation and identifies key policy areas for enhancing co-operation.

Africa’s Development Dynamics 2021

Chapter 1. Digitalisation and jobs in Africa under COVID-19 and beyond

Abstract

In Brief

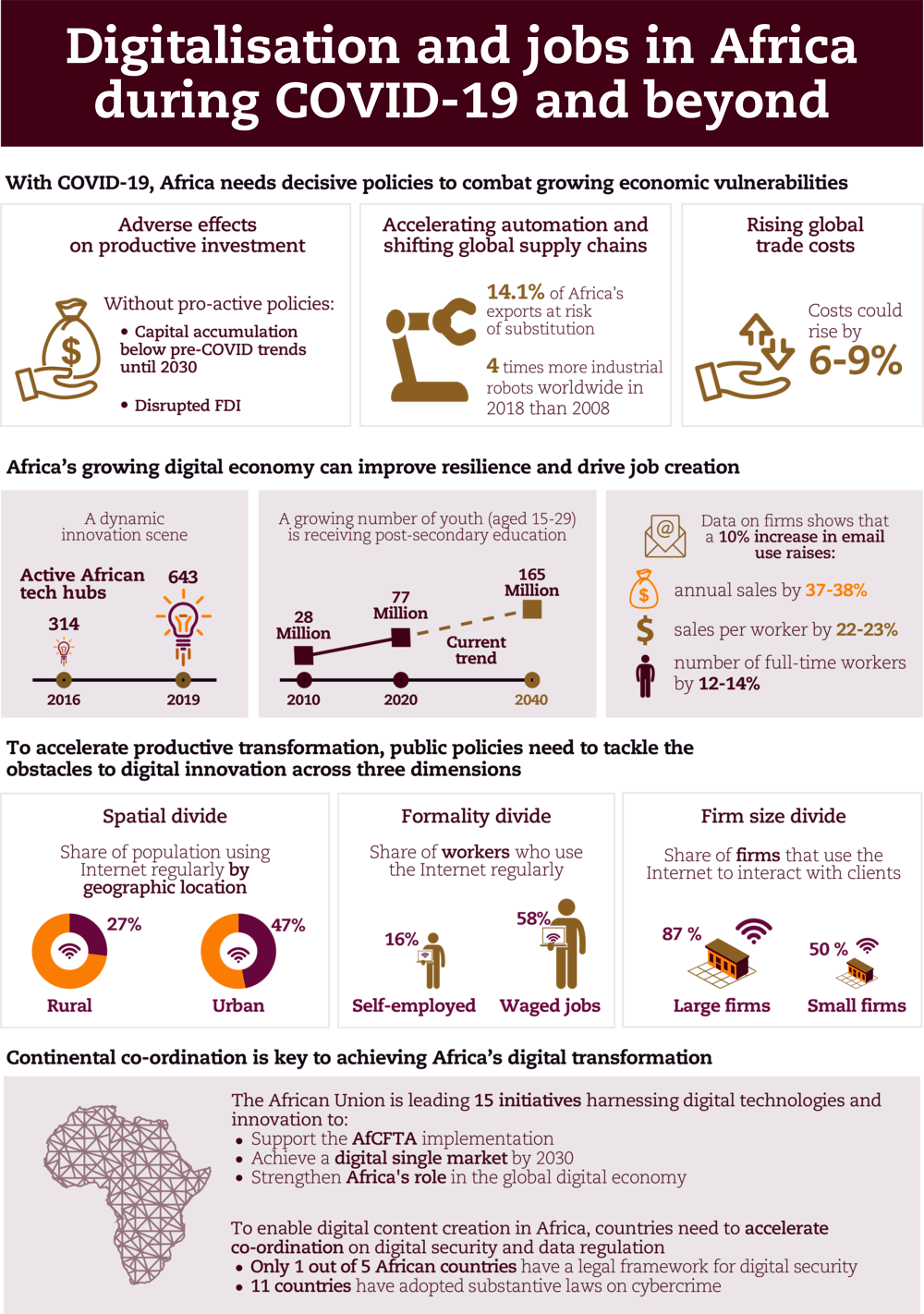

The COVID-19 crisis strengthens the importance of digitalisation in accelerating Africa’s productive transformation and fulfilling the African Union’s Agenda 2063. Prior to the pandemic, the continent had several headline successes in changing its economy and had a growing number of dynamic start-up ecosystems. Together with the mobile money revolution, which now reaches 300 million accounts in Africa – the highest in the world –, these digital ecosystems had already begun transforming job markets (by creating direct and indirect jobs), modernising banking, expanding financial services to the underserved and unlocking innovative business models.

Today, governments can use the digital transformation to trigger mass job creation, especially through indirect channels, by focusing on four key actions:

Ensuring universal access to digital infrastructure to avoid widening inequalities across regions, genders, education levels and employment status. Only 26% of the continent’s rural dwellers regularly use the Internet, compared to 47% of its urban inhabitants. Promoting the spread of digital innovations to intermediary cities can have an important multiplier effect.

Preparing African youth, especially those working in the informal sector, to embrace digitalisation. By 2040, own-account and family workers will represent 65% of employment under current trends and at least 51%, even in more optimistic scenarios.

Tackling barriers to digital adoption and innovation in order to allow smaller firms to grow and compete in the digital age. Only 17% of early-stage entrepreneurs in Africa expect to create six or more jobs, the lowest percentage globally.

Accelerating continental and regional co-ordination is essential to complement national strategies. In particular, adapting the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) to the digital age requires greater co-operation to improve communications infrastructures, roaming services, data regulation and digital security. As of today, only 28 countries in Africa have comprehensive personal data protection legislation in place, while just 11 countries have adopted substantive laws on cybercrime (digital security incidents).

Digitalisation and jobs in Africa during COVID-19 and beyond

Selected indicators on digital transformation in Africa

Table 1.1. Core indicators of digitalisation for job creation in Africa, Asia, and Latin America and the Caribbean, 2020 or latest year

|

|

|

|

Africa (5 years ago) |

Africa (latest year) |

Asia (latest year) |

LAC (latest year) |

Source |

Latest year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Digital sector |

Communications infrastructures |

Percentage of the population with a cell phone |

15.1 |

40.8 |

62.5 |

60.6 |

ITU |

2018 |

|

|

|

Percentage of the population with 4G coverage |

23.8 |

57.9 |

84.0 |

82.7 |

GSMA |

2020 |

|

|

|

International Internet bandwidth per Internet user (kilobits/second) |

8 244.8 |

28 405.0 |

71 424.0 |

54 207.0 |

ITU |

2018 |

|

|

Telecommunication industries |

Total capital expenditure (as a percentage of total revenue) |

21.7 |

18.6 |

22.6 |

20.2 |

GSMA |

2017-19 |

|

|

|

Earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation (as a percentage of total revenue) |

45.2 |

42.6 |

44.3 |

38.7 |

GSMA |

2018-20 |

|

|

|

Total employed headcount within the telecom companies (head account full-time equivalent) |

n.a. |

6 652 |

96 012 |

21 573 |

GSMA |

2016-17 |

|

Digital economy |

Start-up development |

Number of active start-ups that raised at least USD 100 000 |

160 |

570 |

13 713 |

1 382 |

Crunch-base |

2011-20 |

|

|

Digital services |

E-commerce sales (in USD million) |

3 748.0 |

3 959.2 |

97 292.7 |

4 865.2 |

UNCTAD |

2014-18 |

|

|

|

Export of professional and IT services delivered electronically (in USD million) |

16 7825.0 |

21 038.0 |

292 616.0 |

36 869.0 |

UNCTAD |

2014-18 |

|

Digitalised economy |

Internet use among people |

Percentage of the population that uses mobile phones regularly |

n.a. |

72.0 |

87.8 |

77.8 |

Gallup |

2018 |

|

|

|

Percentage of women with Internet access |

15.8 |

30.0 |

46.0 |

56.6 |

Gallup |

2018 |

|

|

|

Percentage of the poorest 40% with Internet access |

10.3 |

22.7 |

33.6 |

45.4 |

Gallup |

2018 |

|

|

|

Percentage of rural inhabitants with Internet access |

15.7 |

25.6 |

35.2 |

40.1 |

Gallup |

2018 |

|

|

Digital-enabled businesses |

Percentage of firms having their own website |

18.2 |

31.4 |

38.7 |

48.2 |

World Bank |

2018* |

|

|

|

Percentage of firms using e-mail to interact with clients/suppliers |

46.1 |

59.1 |

59.3 |

80.9 |

World Bank |

2018* |

|

|

|

Percentage of goods vulnerable to automation that are exported to OECD countries |

n.a. |

14.1 |

18.9 |

19.0 |

World Bank |

2020 |

|

|

Access to finance |

Percentage of the population with a mobile money account |

n.a. |

66.3 |

23.1 |

18.1 |

Demirgüç-Kunt et al. |

2017 |

Note: *Data for 2018 or the latest available. Asia and Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) include lower- and middle-income countries only. n.a. – not available, ITU = Information Technology Union, GSMA = Global System for Mobile Communications Association, UNCTAD = United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

Sources: Authors’ calculations based on data from Crunchbase (2020), Crunchbase Pro (database); Demirgüç-Kunt et al. (2018), The Global Findex Database 2017: Measuring Financial Inclusion and the Fintech Revolution;Gallup (2019), Gallup World Poll; GSMA (2020a), GSMA Intelligence (database); ITU (2020), World Telecommunication/ICT Indicators Database; UNCTAD (2020a), UNCTADSTAT (database); World Bank (2020a), Enterprise Surveys (database); World Bank (2020b), World Development Report 2020.

In a global economy upset by the COVID-19 crisis, digital transformation policies are critical to maintaining the progress towards fulfilling Agenda 2063

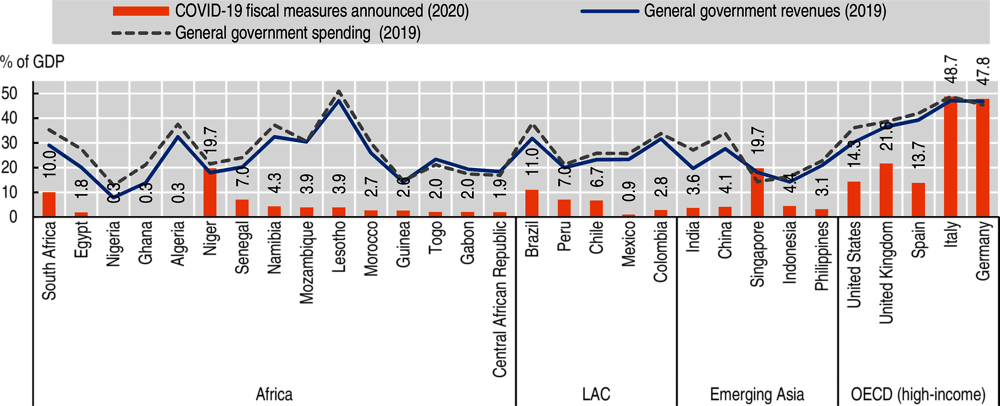

The COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing global crisis have bolstered the urgency for African economies to build stronger and more resilient productive structures. Whereas at the time of writing this report in the second and third quarters of 2020, the spread of the virus has been relatively limited in Africa compared with other world regions, the shock induced by the sudden stop of global economic activity has been far-reaching (see Chapter 8 on financing African countries’ development). Most African countries have taken temporary fiscal measures to respond, despite relatively limited fiscal space (Figure 1.1). In addition, several central banks implemented monetary stimulus packages (IMF, 2020a). However, 41 African economies will undergo a recession in 2020 according to the International Monetary Fund forecast (realised in October 2020). This compares with 11 countries in recession in 2009 when the global financial crisis hit Africa.

Figure 1.1. Fiscal measures undertaken by 15 African countries and 15 non-African countries in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 compared to government revenues and spending in 2019, as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP)

Note: Countries with the highest number of confirmed COVID-19 cases by region as of 15 June 2020. LAC: Latin America and the Caribbean.

Sources: Authors’ compilation based on OECD (2020a), Country Policy Tracker (web portal); IMF (2020b), Policy Responses to COVID-19: Policy Tracke. (web portal); Bruegel (2020), The Fiscal Response to the Economic Fallout from the Coronavirus (dataset); IMF (2020c), World Economic Outlook, April 2020 (database).

African policy makers have implemented many digital solutions to fight the COVID-19 pandemic at local, national, regional and continental levels. Ministries of education in 27 African countries were able to provide well-functioning e-learning platforms for students by May 2020 (UNESCO, 2020). Most African central banks have strongly encouraged the population to use digital payments (GSMA, 2020b).1 The Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention − in collaboration with 20 international partners and foundations − has launched a not-for-profit continental e-platform to help African governments procure diagnostic tests and medical equipment from certified suppliers on the global market. Janngo, a start-up based in Côte d’Ivoire, designed and built the web portal. Moreover, several start-ups and talented entrepreneurs have developed new and affordable solutions to reduce the pandemic’s burden on the continent’s fragile health systems. From Solar Wash, a sun-powered, touch-free water dispenser in Ghana, to more advanced technologies such as DiagnoseMe, a remote mobile app in Burkina Faso, and COVID-19 triage tools in Nigeria (Ochieng and Fokuo, 2020; Sadibe, 2020). In Senegal, the Institut Pasteur de Dakar developed a prototype for a ten-minute COVID-19 diagnostic test.

However, the adverse effects of COVID-19 on Africa’s productive capacities could last more than a decade and reverse Africa’s progress towards fulfilling Agenda 2063. Simulations by Djiofack, Dudu and Zeufack (2020) found that Africa’s capital accumulation and productivity could remain below their pre-COVID 19 trajectories until 2030. The most consequential disruptions in national economies could be productivity decline, reduced capital utilisation and increased trade costs. These disruptions will slow down Africa’s productive transformation and, thereby, the achievement of Agenda 2063 (AU/OECD, 2019). Furthermore, the pandemic risks disrupting Africa’s recent progress in health and education, which could reduce the ability of the current generation to earn higher incomes.

COVID-19 is likely to accelerate ongoing trends in global trade. This makes digitalisation and regional and continental co-operation necessary conditions for transforming African economies.

COVID-19 may intensify the ongoing shift in international supply chains. Since 2010, international firms have been gradually using more local and regional inputs in their products (Miroudot and Nordström, 2019; Baldwin and Tomiura, 2020; OECD, 2020b). The increased need for more resilient supply chains in the post-COVID-19 period, combined with the imperative of reducing the carbon footprint of production, will amplify this transformation (UNCTAD, 2020b). This could result in the “regionalisation” of complex global value chains and disrupt global FDI flows.

Uncertainty could lead to higher trade costs. The volume of world merchandise trade has been steadily declining since the 2008-09 global financial crisis (WTO, 2020). The OECD estimates that trade costs could rise between 6% and 9% across transport modes in the post-COVID-19 era (Benz, Gonzales and Mourougane, 2020). Trade restrictions could further increase global trade costs. During the first semester of 2020, 89 jurisdictions implemented 154 export controls on medical supplies, and 28 jurisdictions executed 40 export curbs on agricultural and food products (Global Trade Alert, 2020).

The COVID-19 crisis may accelerate automation. In just one decade, installations of industrial robots worldwide increased almost fourfold, from 112 000 units in 2008 to 422 000 units in 2018 (IFR, 2020). This demand for robot installations is primarily driven by the automotive industry (30%), followed by electronics (25%), and metal and machinery (10%). The servicification of manufacturing (i.e. the increasing importance of services for value addition in manufacturing) and consumer preferences for more sustainable and low-carbon production processes may lead firms to favour local over off-shored production. Top European firms anticipate adopting more robotic systems in their post-COVID-19 investment plans (Ahmed, 2020).

Increasing automation in advanced countries is likely to affect African labour markets. Our estimates, based on World Bank (2020b), show that 14.1% of Africa’s export flows to OECD countries could be at risk of being substituted. The risk is even higher for North Africa (23% of the region’s total exports go to OECD countries). In comparison, the risk is 18.9% for developing Asia and 19.0% for LAC.

Effective implementation of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) agreement can strengthen regional value chains and build economic resilience against future crises. Prior to COVID-19, Africa’s regional markets were growing fast, with demand for processed goods expanding 1.5 times faster than the global average (AUC/OECD, 2018).

The COVID-19 crisis has ripened the context for digitalisation to accelerate Africa’s productive transformation and make the continent more resilient to future crises. Africa’s rapid development dynamics can fuel local firms’ technological leapfrogging, if governments adapt their development strategies to the new opportunities. Throughout the last decade, Africa’s fast-growing regional markets allowed many local firms to increase in size and productivity. Still, the power of the digital transformations remains largely to be harnessed in many African countries. While the global response to COVID-19 has heavily relied on digital technologies, persistent digital divides constrain Africa’s capacity to respond to shocks from the pandemic. An economy-wide digital transformation – as defined in Box 1.1 – can only be achieved if i) digital technologies are widespread and help companies in other economic sectors become more productive; ii) people find better employment opportunities; and iii) governments improve supportive public services.

Box 1.1. Definitions of digitalisation and digital transformation

Digitalisation refers to the use of digital technologies and data as well as to the interconnection that results in new activities or changes to existing activities (OECD, 2019a). Today, digital technologies include:

mobile data networks (4G and 5G, for example),

mobile payment and financial products,

the Internet of things (IoT),

blockchain,

artificial intelligence (AI),

big data analytics and cloud computing.

Digitalisation differs from the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR). Whereas the digitalisation of production plays a key role in advancing 4IR, certain technological changes − such as bioproduction and the bioeconomy, nanotechnology, and materials innovation − may be less relevant in the African context (OECD, 2017a; AfDB/OECD/UNDP, 2017).

Digital transformation refers to the changes that digitalisation is making to the economy and society. These changes affect virtually all sectors of the economy (OECD, 2019a). They also have impacts on the inputs, functions and economic models of less digital-intensive sectors such as agriculture, construction and trade (for these sectors, the use of digital technologies contributes to lowering transaction costs and addressing information asymmetries associated with certain activities like access to finance) (Dahlman, Mealy and Wermelinger, 2016). At the same time, the digital transformation reshapes the distribution of production, value addition and economic rents across workers, firms and spaces according to the ability of workers and firms to control, own and access these new modes of production (Foster and Graham, 2016). For example, digitally intermediated data services and algorithms are increasingly underpinning decision-making and production processes and have become an important source of value. A countrywide digital transformation strategy aimed at creating jobs, therefore, needs to extend beyond the information and communications technology (ICT) activities to embrace all economic sectors in order to benefit from jobs indirectly created by digitalisation (OECD, 2020c).

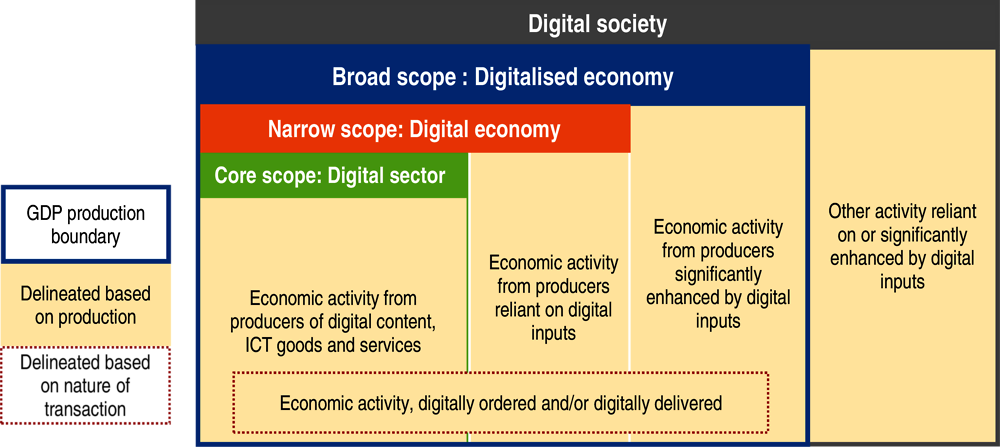

Bukht and Heeks (2017) distinguish three scopes of the digital transformation ;

The core scope focuses on the ICT sector. This measure includes economic activities from producers of digital content, ICT goods and services.

The narrow scope includes all emerging economic activities that exist solely thanks to digital technologies. This scope expands beyond the ICT sector. It includes other elements such as business-offshoring processing, information technology outsourcing, as well as emerging activities that did not exist before digital technologies, e.g. the gig economy (click-work, Upworks) and the platform economy (such as Airbnb, Uber, eBay and Alibaba).

The broad scope covers all economic activities significantly enhanced by digital technologies: e-business (ICT-enabled business transactions, such as mobile money and other financial technologies) and its sub-sets, e-commerce, e-delivery services, use of digitally automated technologies in manufacturing and agriculture.

OECD (2020c) complements this approach by adding a fourth scope, and by proposing an alternative perspective on how to measure digital transformation comprehensively (Figure 1.2):

The fourth scope of the digital transformation process, the digital society. extends beyond the three previous scopes to incorporate digitalised interactions and activities excluded from the GDP production boundary, i.e. zero priced digital services (such as the use of public digital platforms).

In order to combine flexibility and precision for measurement purposes, an alternative perspective is to cover all economic activity digitally ordered and/or digitally delivered. Rather than considering the firms’ output or production methods, this measure would focus on ordering or delivery methods.

Due to this report’s focus on job creation, and data constraints, the scope of our analysis will be limited to the core, the narrow and the broad scope of digital transformation.

Figure 1.2. Defining the digital economy through the four-scope model

Source: OECD (2020c), A Roadmap Toward a Common Framework for Measuring the Digital Economy.

By 2040, digitalisation can transform Africa’s job markets, if public policies work for all

Prior to 2020, digitalisation was already well underway in Africa, with several headline successes and dynamic ecosystems

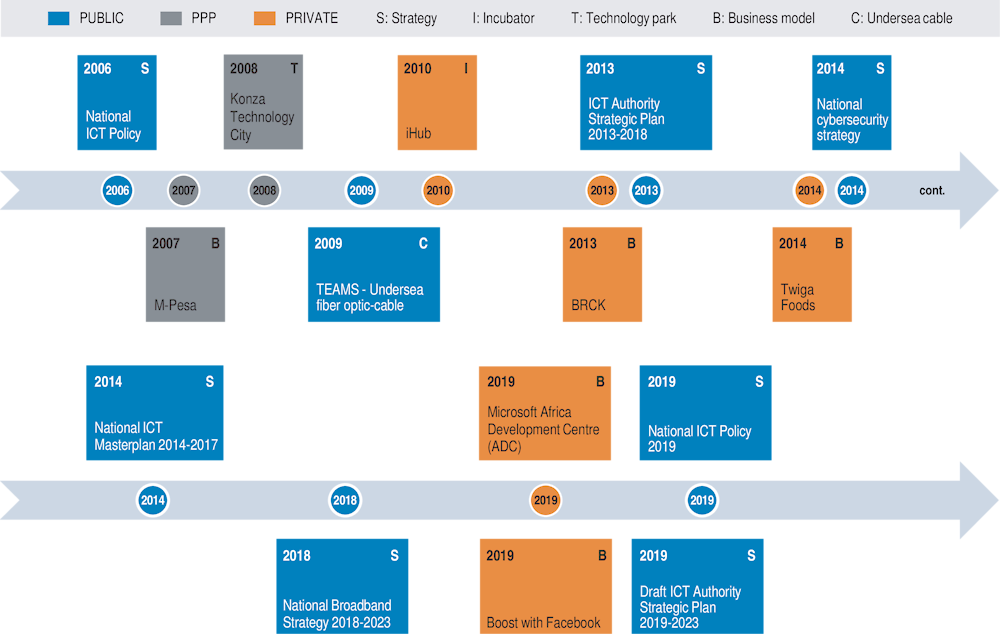

2007 was a landmark year for Africa’s digitalisation. Safaricom introduced the M-PESA2 mobile money service, the very first in Africa. At its inception, the major innovation was to make financial services available via mobile phones in order to supplement Kenya’s lack of banking infrastructure (e.g. automatic teller machines), thus addressing the unmet financing needs in underserved areas. The business model also significantly reduced transaction fees.

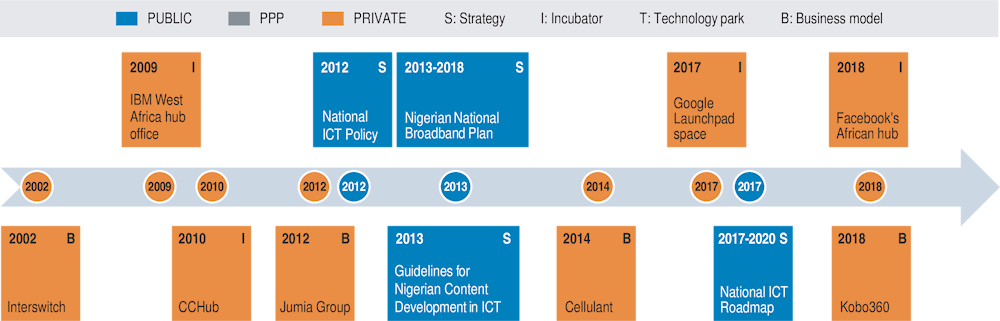

Since 2007, the mobile money revolution has rapidly expanded. In 2018, Africans had more than 300 million mobile money accounts, more than any other continent in the world. There are now more than 500 companies providing technology-enabled innovation in financial services (referred to as fintech) such as mobile money in Africa. Countries now offer a wide number of digital financial products (e.g. deposits, savings accounts and payment systems). New big players have grown (Table 1.2). For example, in November 2019, Interswitch became Africa’s first start-up company valued at more than a billion dollars. That year, Interswitch had more than 1 000 employees and an estimated annual revenue of over USD 76 million. In February 2020, South African start-up JUMO raised USD 55 million to expand to Bangladesh, Côte d’Ivoire, India and Nigeria (Kazeem, 2020). Johannesburg and Cape Town in South Africa, Nairobi in Kenya, and Lagos in Nigeria rank among the top 100 cities for fintech ecosystems worldwide (Findexable, 2019).

Africa’s digital development is rapidly expanding in other sectors. Entrepreneurial and digitally savvy Africans are building innovative solutions to meet the booming demand for health, education and agriculture, among others. They are turning digital technologies and Africa’s specific needs to their advantage to deploy fast-growing business models. For example, Kobo360, a Nigerian start-up founded in 2017, is looking to revolutionise the country’s domestic transport and logistics sector, as well as to link Nigeria’s farmers with buyers all over the world. In August 2019, the company raised USD 30 million (Bright, 2019a). Several other tech-enabled start-ups are improving the transport of goods in Africa. These include Kenya’s Lori Systems, an all-in-one logistics platform, and Ghana’s AgroCenta, which provides a supply chain platform facilitating small-scale farmers’ access to large markets and a financial inclusion platform.

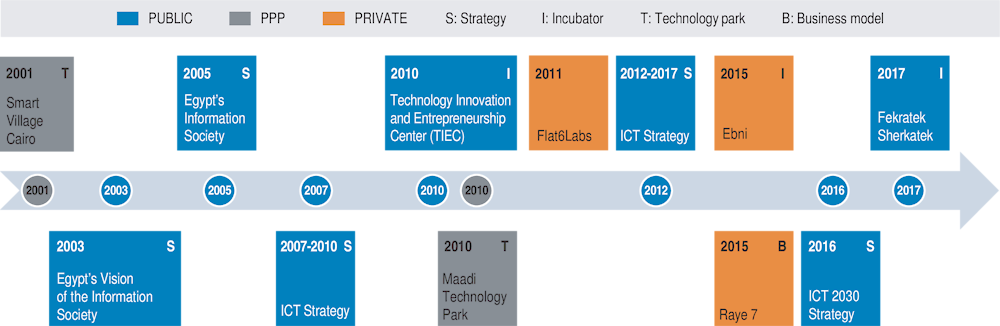

Innovation hubs and incubators are also flourishing. In 2019, 643 tech hubs were active across Africa, up from 314 in 2016, and only a handful in 2010 (AFRILABS and Briter Bridges, 2019). The four African countries with the most tech hubs are Nigeria (with 90 tech hubs), followed by South Africa (78), Egypt (56) and Kenya (50). In tech hubs such as Yabacon Valley (in Lagos), the diaspora is playing an important role in providing ideas, networking and venture capitals. Annex 1.A1 of this chapter highlights successful business models and policies for each of these four tech clusters in Africa. The regional chapters offer examples from other countries.

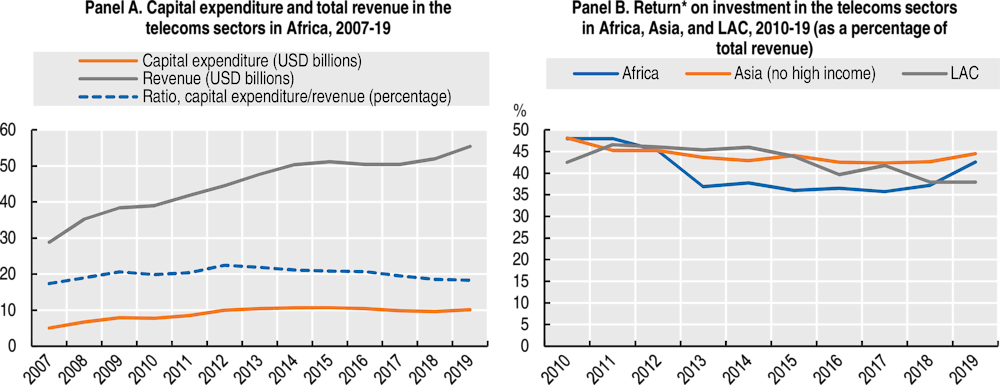

Africa’s telecom sectors, which are critical for digital transformation, have shown robust growth throughout the last two decades. The introduction of competition in the mobile telecom services and other major regulatory reforms during the 2000s have made this sub-sector attractive to new opreators and improved the quality of service supply. Despite the global financial crisis in the late 2000s, telecom sectors have grown significantly in almost all African countries. Annual revenues of Africa’s telecom companies have steadily increased, from USD 29 billion in 2007 to USD 55 billion in 2019 (Figure 1.3, Panel A), and capital expenditure has doubled. Key indicators on the returns on investment are strong in all five African regions (Figure 1.3, Panel B).

Table 1.2. Twenty examples of start-ups, accelerators and large telecom companies within different layers of Africa’s digital ecosystem, 2020

|

|

Company name |

Year of foundation |

Estimated revenue range (USD million) |

Number of employees |

Total funds raised (USD million) |

Main activity |

Location (city) |

Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Digital economy |

OPay |

2018 |

100 to 500 |

1 053 |

170.0 |

Fintech |

Lagos |

Nigeria |

|

|

Interswitch |

2002 |

50 to 100 |

1 003 |

34.7 |

Fintech |

Lagos |

Nigeria |

|

|

Cellulant |

2004 |

10 to 50 |

440 |

54.5 |

Fintech |

Nairobi |

Kenya |

|

|

Fawry |

2008 |

10 to 50 |

133 |

122.0 |

Fintech |

Cairo |

Egypt |

|

|

JUMO |

2014 |

1 to 10 |

299 |

146.7 |

Fintech |

Cape Town |

South Africa |

|

Digitalised economy |

M-KOPA |

2011 |

10 to 50 |

694 |

161.8 |

Energy |

Nairobi |

Kenya |

|

|

Twiga Foods |

2013 |

10 to 50 |

275 |

67.1 |

Business-to-business e-commerce |

Nairobi |

Kenya |

|

|

Jumia Group |

2012 |

500 to 1 000 |

7 564 |

823.7 |

E-commerce |

Lagos |

Nigeria |

|

|

Kobo360 |

2018 |

< 1 |

149 |

37.3 |

Logistics |

Lagos |

Nigeria |

|

|

takealot.com |

2011 |

100 to 500 |

1 574 |

231.1 |

E-commerce |

Cape Town |

South Africa |

|

|

Raye7 |

2016 |

1 to 10 |

25 |

n/a |

Ride sharing |

Cairo |

Egypt |

|

Start-up/accelerator |

Naspers |

1915 |

2 800 to 3 000 (headline earnings) |

2 734 |

n/a |

ICT investment |

Cape Town |

South Africa |

|

|

Co-Creation Hub |

2010 |

n/a |

92 |

5 (funds raised) |

Start-up incubation |

Lagos |

Nigeria |

|

|

Flat6Labs |

2011 |

n/a |

10 |

15 (raised for start-ups) |

Early stage venture, seed funds |

Cairo |

Egypt |

|

Core IT and digital sector |

Sensor Networks |

2015 |

n/a |

17 |

1.0 |

Software and IT consulting |

Cape Town |

South Africa |

|

|

Mara Phones |

2018 |

n/a |

39 |

n/a |

Hardware manufacturing |

Kigali |

Rwanda |

|

|

Aerobotics |

2014 |

1 to 10 |

84 |

10.3 |

Software and IT consulting |

Cape Town |

South Africa |

|

|

Orange |

1988 |

> 10 000 |

122 444 |

774.4 |

Telecoms |

Casablanca (regional headquarters) |

Morocco |

|

|

MTN Group |

1994 |

1 000 to 10 000 |

34 656 |

121.1 |

Telecoms |

Johannesburg |

South Africa |

|

|

Safaricom |

1997 |

1 000 to 10 000 |

7 610 |

2 590.0 |

Telecoms |

Nairobi |

Kenya |

Note: * The numbers of employees were retrieved from the LinkedIn profiles. n/a = not applicable.

Source: Authors’ compilation based on Crunchbase (2020), Crunchbase Pro (database), and LinkedIn (n.d.).

Figure 1.3. Capital expenditure and revenue by telecom companies in Africa and return on investment in Africa, Asia, and Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), 2007-19

Note: Return on investment: earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on GSMA (2020a), GSMA Intelligence (database), www.gsmaintelligence.com/data/.

Policies can use digitalisation to transform Africa’s job markets, especially through indirect job creation

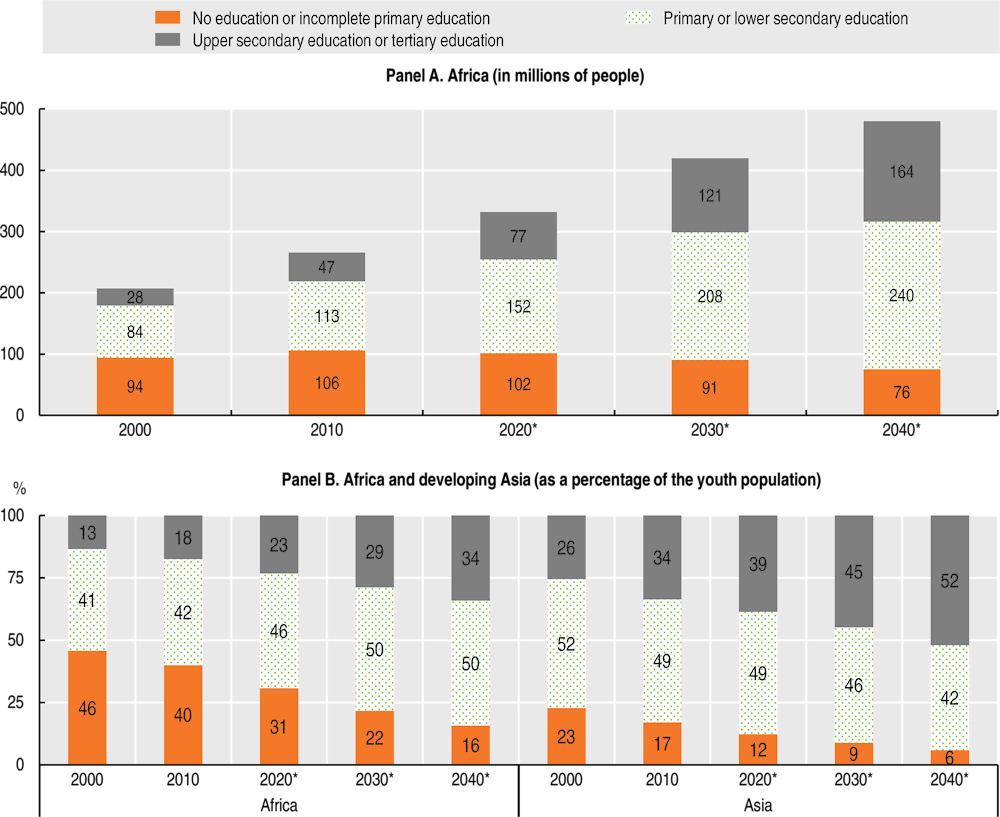

Africa’s biggest asset for digitalisation will be its growing population of increasingly better-educated youth. The number of Africans aged 15-29 with an upper secondary or tertiary education has already risen from 47 million in 2010, to 77 million in 2020 (Figure 1.4, Panel A).3 Under business-as-usual education scenario, this number will increase to 165 million by 2040. In relative terms, the proportion of African youth completing an upper secondary or tertiary education could reach 34% by 2040 (closer to Asia’s proportion), up from 23% today (see Figure 1.4, Panel B). This figure could even reach 73% (233 million) by 2040 if African countries can replicate Korea’s fast-track education scenario with more ambitious investments in education and health.

Figure 1.4. Youth cohorts, aged 15-29, by educational attainment in Africa and Asia according to business-as-usual scenarios, 2000-40

Note: (p) = projections. Due to data availability, the figures reported are for the population aged 15-29.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital (2018), Wittgenstein Centre Data Explorer Version 2.0 (Beta) (database).

Digital sectors create few direct jobs, which are not sufficient to meet the continent’s employment needs on their own.African Development Dynamics 2018 showed that African economies must create more and better jobs to absorb the 29 million youth who will reach working age every year between now and 2030 (AUC/OECD, 2018). For comparison, telecom companies directly employ about 270 000 staff. Jobs related to the ICT services, such as the IT and business process outsourcing and software developpers, remain limited and mainly concentrated in few countries. The 20 fast-growing start-ups in Table 1.2 total less than 20 000 employees. More broadly, the digital ecosystem will not provide enough jobs for all young Africans in the near future.

The real potential for large-scale job creation lies in the diffusion of digital innovations from the lead firms to the rest of the economy. The channels for indirect jobs creation include: i) the input-output linkages within the digital ecosystem; ii) the dynamic spillover effects, which depend on the rates at which local economies increase productivity; and iii) the society-wide effects beyond GDP (see Table 1.3). For example, the mobile money revolution in East Africa has led to significant job creation through several indirect channels such as spillover effects on households and businesses and enabling new business models (Box 1.2).

Table 1.3. Impacts of digitalisation on job creation: A review of the main channels

|

Type of impact |

Main channels |

Description |

|---|---|---|

|

Input-output impacts on jobs and value-addition(economic activities and linkages within a digital ecosystem) |

Direct jobs and outputs |

Employment and economic production directly generated in the core enterprises in charge of developing network facilities or digital solutions |

|

Indirect jobs and outputs |

Employment and economic production generated by subcontractors or others who supply inputs and services (e.g. metal products, electrical equipment, professional services) |

|

|

Induced jobs and outputs |

Multiplier effects generated by household spending based on the income earned from the direct and indirect effects (e.g. retail trade, consumer goods and services) |

|

|

Dynamic spillover effects on the local economy and society as a whole |

Productivity |

Improvement in productivity due to the adoption of more efficient business processes enabled by quality infrastructures, improved digital technologies and related tools and better digital services |

|

Innovation |

Acceleration of innovation resulting from the introduction of new digital-enabled applications and services: new processes, products and services (e.g. telemedicine, search engines, online education, videos on demand) |

|

|

Value chain development |

✓ Better linkages among different actors along the core economic clusters (in agriculture, manufacturing, services) in a given area ✓ Entirely new activities in the regions (e.g. tourism, outsourcing of services, virtual call centres) |

|

|

Society-wide effects (beyond GDP) |

✓ For firms and citizens, greater access to information and participation in and oversight of policy-making processes ✓ Improved government transparency, accountability and effectiveness ✓ Better financial inclusion and resource mobilisation ✓ Greater consumer surplus and benefits from more diversified products and services, gains in terms of time-use, etc. |

Source: Adapted from AUDA-NEPAD (2019), “The PIDA Job Creation Toolkit”; ITU (2012), Impact of Broadband on the Economy: Research to Date and Policy Issues; and OECD (2013), “Measuring the Internet economy: A contribution to the research agenda”.

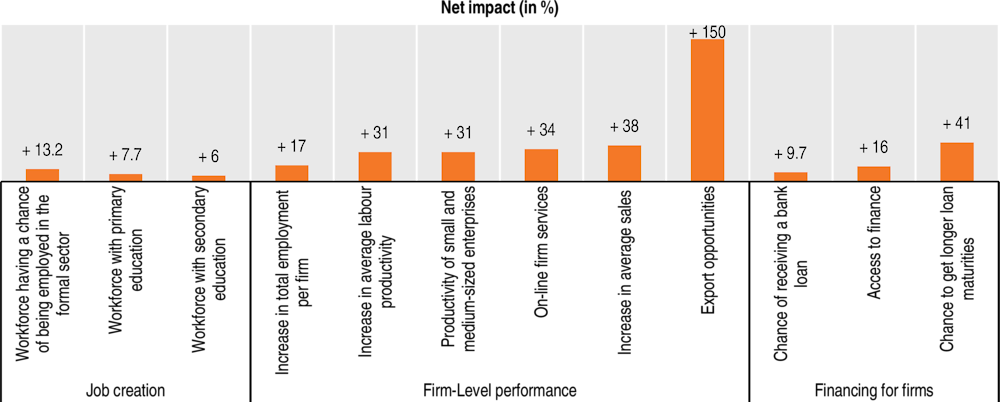

Figure 1.5 reports econometric findings from a review of empirical studies on Africa and other developing regions. A landmark study by Hjort and Poulsen (2019) shows that for 12 African countries, the arrival of high-speed Internet to a region, a proxy for the level of digital development, positively increases the employment rate for both workers with high and low education. Building on their approach, other papers have shown an even higher impact of digitalisation on the performance of firms (productivity, sales and new export opportunities) and on their access to longer-term financing. For example, data on more than 30 000 firms from 38 developing countries – including 9 countries in Africa – show that a 10% increase in e-mail use by firms in a given geographic area raises their total annual sales by 37-38%, sales per worker by 22-23% and the number of full-time workers by 12-14% (Cariolle, Goff and Santoni, 2019).4

Figure 1.5. Impacts of digitalisation on job creation in Africa and other developing countries

Note: This is a summary of econometric findings. The data presented here show the marginal impact of digitalisation (infrastructure development, speed of the Internet connection and Internet usage among the population) on job creation, firm-level performance, and financing for firms in Africa and other developing countries.

Source: Authors’ illustration based on Hjort and Poulsen (2019), “The arrival of fast internet and employment in Africa”; Cariolle, Goff and Santoni (2019), “Digital vulnerability and performance of firms in developing countries”; and D’Andrea and Limodio (2019), “High-speed internet, financial technology and banking in Africa”.

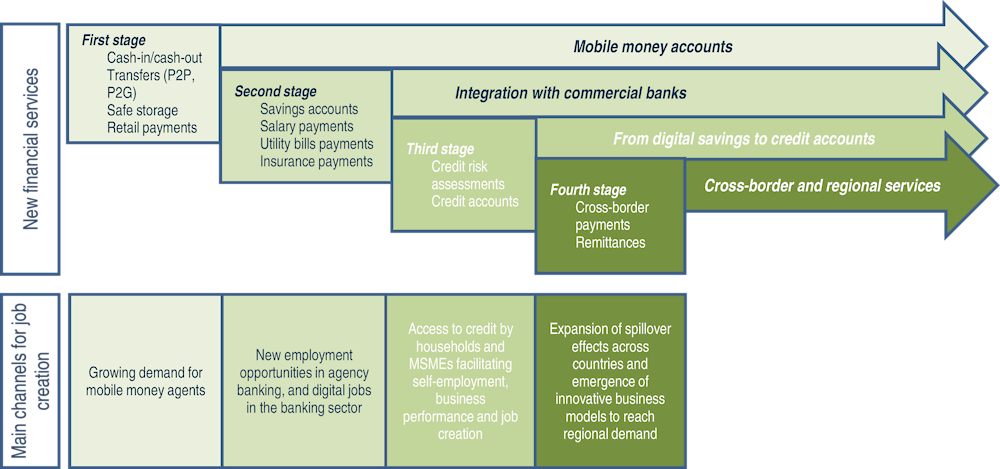

Box 1.2. The impact of mobile money on employment in East Africa

The story of fintech in East Africa illustrates the dynamic links between digitalisation and jobs, through several spillover effects.

First, in Kenya, the number of mobile money agents – i.e. own-account workers sub-contracted to facilitate the service – grew from 307 in March 2007 to over 240 000 in March 2020 (Central Bank of Kenya, 2020).

Second, competitive pressure from the mobile payment system forced traditional commercial banks to adopt digital financial services and introduced agency banking for the underserved population. The number of agents employed by agency banking reached 60 000 in 2017. In 2015, the volume of transactions using M-PESA, a mobile domestic money transfer and financing service, reached 45% of Kenya’s GDP. The percentage of the population having a formal banking account in Kenya grew from 26% in 2006 to 75% in 2016 (Central Bank of Kenya, 2016).

Third, access to mobile money services has triggered very positive spillover effects on households and businesses. In Kenya, it helped raise at least 194 000 households out of extreme poverty between 2008 and 2014. It also enabled 185 000 women to switch their main occupations from subsistence agriculture to small businesses or retail over the same period (Suri and Jack, 2016).

Fourth, mobile financial services are now enabling new business models such as pay-as-you-go financing. Benefiting from the M-PESA services since 2011, M-KOPA provides affordable electricity from solar power, which has reached 750 000 homes and businesses across East Africa. Many studies have shown a positive impact of mobile money on the performance and growth of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) in terms of productivity, sales and market shares.

Figure 1.6. The evolution of mobile money products and channels for job creation in East Africa

Note: P2P = person to person. P2G = person to government

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on Ndung’u (2018), “Next steps for the digital revolution in Africa: Inclusive growth and job creation lessons from Kenya”.

Scaling up the benefits of digitalisation requires diffusing digital innovations beyond large cities, helping informal workers become more productive and empowering enterprises for digital competition

Achieving universal coverage of communications infrastructures requires place-based policies to overcome spatial inequalities

Over the last decade, most African countries have been actively developing their ICT infrastructure networks, with significant investment from the private sector. Forty-five (out of 54) African countries had an active digital broadband infrastructure development strategy in 2018, compared to 16 in 2011 (see ITU, 2018). In 2018, digital infrastructure financing was USD 7 billion, with 80% of this amount coming from private sector investments (ICA, 2018). As shown earlier in Figure 1.3, returns on investments are solid and similar to the levels in Asia. Progress in communications infrastructures can be sequenced between three main segments stretching from first mile, middle mile and last mile access. The first mile refers to the points where the Internet enter a country. The middle mile refers to national backbone network and the associated elements such as data centers and Internet exchanges. The last mile refers to local access networks that connect the end users.

Since 2009, telecom companies and global tech actors have spearheaded the development of submarine cables – i.e. the first-mile communication infrastructure that connects African countries to the global Internet. Investment in submarine cable systems and terrestrial landing stations have linked most African countries to the global Internet and increased the connection speed. The continent’s total inbound international Internet bandwidth capacity has increased by more than 50 times in just ten years to reach 15.1 Terabytes per second (Tbps) in December 2019, up from only 0.3 Tbps in 2009 (Hamilton Research, 2020). Prospects for new projects remain robust. In May 2020, Facebook and a group of telecom companies – including China Mobile International, MTN GlobalConnect, Orange and Vodafone – began collaborating to deploy 37 000 kilometres (km) of subsea cables by 2024 to connect Africa’s Internet broadband network to Europe and the Middle East. This new broadband network, called 2Africa, should deliver more than the total combined Internet traffic capacity of all 26 subsea cables serving Africa today (2AfricaCable, 2020).

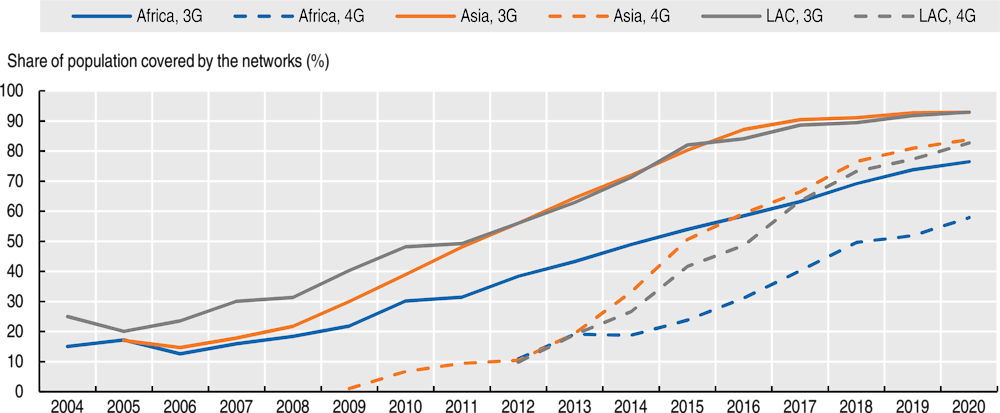

Africa has also more than tripled the middle-mile Internet infrastructure that expands the connection within and between countries. Exhaustive inventories show that Africa’s operational fibre-optic network extended from 278 056 kilometres (km) in 2009 to 1.02 million km in June 2019. (Hamilton Research, 2020). About 58% of the population in Africa now live in an geographic area covered by the fourth generation (4G) mobile network (Figure 1.7). North Africa has the highest figure in Africa, with 85% of its population covered by the 4G network in 2020 (see Chapter 6). This is to compare with 86.5% in Latin America and the Caribbean and 88% in developing Asia in the same year.

Figure 1.7. Percentage of the population covered by the 3G and 4G networks in Africa, Asia and Latin America and Caribbean (LAC), 2004-20

Despite this progress, access to the last mile broadband infrastructures remains a challenge across the continent. Currently, nearly 300 million Africans live more than 50 km from a fibre or cable broadband connection. Complementary solutions to expand and enhance the transmission network such as Internet exchange points (IXPs), data servers and satellite transmission systems remain underdeveloped. For example, 42% of African countries still do not have IXPs, and their domestic Internet traffic has to be routed abroad to reach its destination. Achieving universal access to broadband connectivity in Africa by 2030 would require approximately USD 100 billion or USD 9 billion a year, which would include laying out at least 250 000 kilometres of fibre across the region (ITU/UNESCO, 2019).

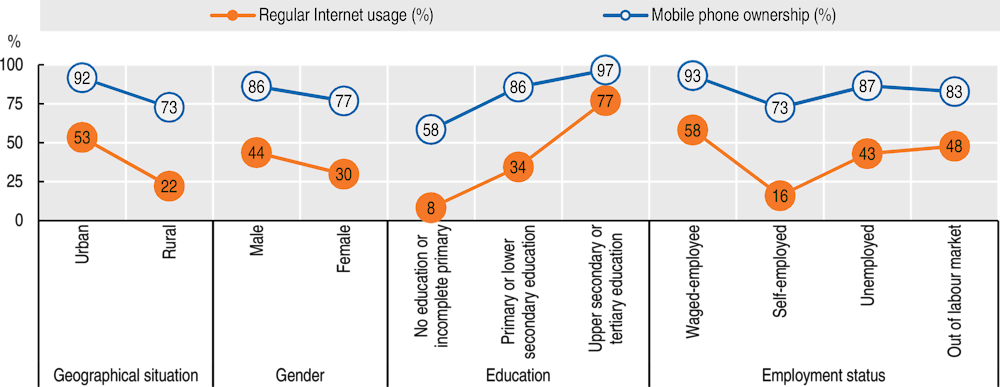

The use of communications infrastructures by the population is also highly unequal across space, gender, education levels and employment status. For example, more than 75% of Africa’s youth has a mobile phone5. However, only 22% of rural youth regularly use the Internet, compared to 53% of urban inhabitants (Figure 1.8). Similarly, the share of young people regularly using the Internet varies across gender groups (30% of women and 44% of men), education levels (8% of those with less than a primary education and 77% of those with an upper secondary or higher education) and employment status (16% of those self-employed and 58% of those with waged jobs).

Figure 1.8. Mobile phone and Internet usage among Africa’s youth, aged 15-29, by geographical situation, gender, level of education and employment status, 2015-18

Notes: The results are based on survey data from 34 African countries. Primary education: completed elementary education or less (up to 8 years of basic education); secondary: completed some secondary education and up to 3 years tertiary education (9 to 15 years of education); tertiary: completed 4 years of education beyond high school and/or received a 4-year college degree.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Afrobarometer (2019), Afrobarometer (database).

Finally, the high concentration of the existing digital ecosystems in the megacities raises the concern of growing spatial inequality due to digitalisation. The majority of Africa’s digital hubs and start-ups concentrate in large cities. For example, five cities host 49% of the most dynamic African start-ups identified by Crunchbase in 2019 (AUC/OECD, 2019): Cape Town (12.5%), Lagos (10.3%), Johannesburg (10.1%), Nairobi (8.8%) and Cairo (6.9%). These five cities account for just 53 million inhabitants, less than 4% of the total African population. They offer strong digital ecosystems with critical masses of skills, supporting infrastructure, investors and communities for entrepreneurship.

Bridging these spatial divides is a critical first step to avoid widening the mismatch between the spatial distributions of jobs and people. Today, the majority of the African population lives outside the largest cities. About 70% of Africa’s young people reside in rural areas. Rural populations make up 1.4 billion people. They will continue to grow in absolute terms, at least beyond 2050.

Place-based policy approaches can make a difference by articulating various sectoral policies to tap underutilised potential in all regions, enhancing regional competitiveness (AfDB/OECD/UNDP, 2015; OECD, 2016). The channels through which digital innovations diffuse into the local economy depend on several place-specific factors. In remote regions, non-digital factors such as limited skills, basic infrastructure (e.g. electricity) and access to finance can prevent a significant proportion of people from benefiting from digital technologies. Chapter 2 will further discuss the ways policies can adapt to these place-specific constraints.

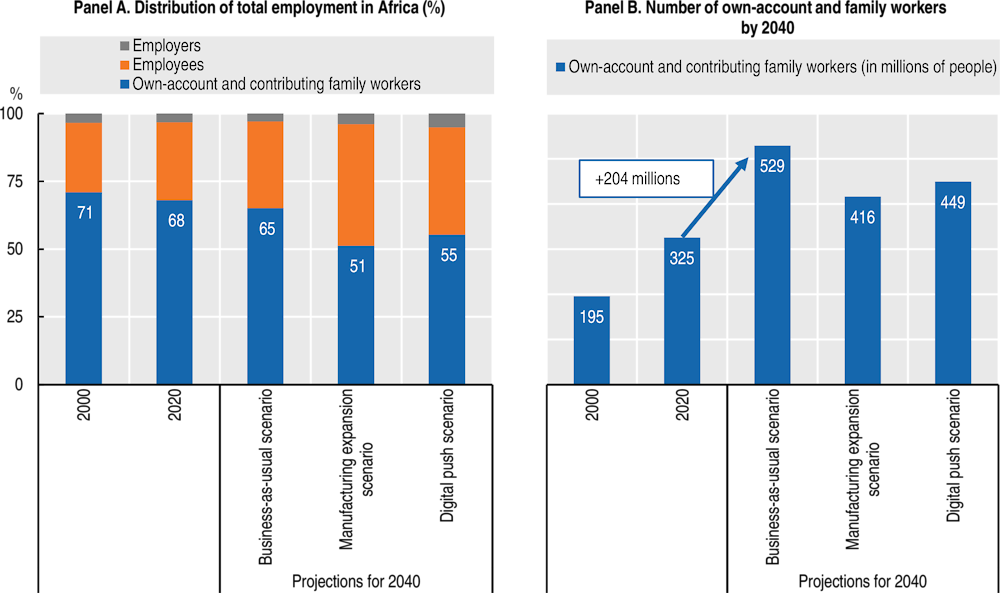

Policy makers must prepare Africa’s informal workforce to take advantage of the digital transformation

Self-employment, often in the informal economy, will likely continue to be the most dominant form of employment in Africa by 2040, even in two optimistic projection scenarios. Own-account and family workers currently account for 68% of all workers in Africa, down from 71% in 2000 (Figure 1.9, Panel A). If the trend over the past 20 years continues, this share will drop to 65% (business-as-usual scenario). In absolute numbers, this means that the number of own-account workers in Africa could increase by 163% to reach 529 million people in 2040, compared to an estimated 325 million people in 2020 (Figure 1.9, Panel B). Even if Africa could replicate China’s success in accelerating structural transformation in the manufacturing sector during the 1990-2010 period (projection scenario S2), the majority (51%) of workers would continue to work in household enterprises. Similarly, if Africa were to replicate India’s progress in building a world-class ICT and business services sector (projection scenario S3), 55% of Africa’s jobs would still fall in the category of own-account workers. Box 1.3 explains the methodology for spatial analysis and labour market projections.

Figure 1.9. Size of self-employment in Africa’s labour markets in 2000, 2020, and projections according to three scenarios by 2040

The informal sector remains the main gateway to the job markets for the vast majority of Africa’s working-age population, including young graduates. To date, only 20% of Africa’s working-age population are on wage-paying employment and only 11% of women (AUC/OECD, 2018, ILO, 2020). About 85.8% of employment in Africa is informal, compared with 25.1% in Europe and Central Asia (ILO, 2018). School-to-work transition surveys confirm that more than 75% of young graduates aged 15-29 start working in informal activities (OECD, 2017b).

Currently, many informal workers are missing out on the benefits of digitalisation, due to low digital adoption. Only 16% of self-employed workers use the Internet regularly, compared to 58% of people working in waged jobs (Figure 1.8). The low uptake of digital tools is a missed opportunity for informal workers. The regional chapters of this report showcase various examples where digital tools and digital-enabled business models permit informal workers to increase their productivity, upgrade their production and formalise their businesses. In particular, fintech has shown tremendous results in extending financial services to the underserved in East Africa (see Box 1.2).

Box 1.3. Methodology for projecting Africa’s labour market outcomes by 2030 and 2040

This projection exercise aims to show three scenarios for what Africa’s labour markets could look like in 2030 and 2040. The first scenario – the business-as-usual scenario (S1) – extrapolates trends observed in Africa’s labour market over the past 20 years. Two more optimistic scenarios – manufacturing expansion (S2) and digital push (S3) – reflect manufacturing-led development (e.g. Lin, 2011; Lin and Monga, 2010) and service-led growth (Ghani and O’Connell, 2014).

Scenarios S2 and S3 rely on the hypothesis that the continent will be able to achieve its ongoing plan to create a single continental market by 2030 and/or a digital single market by 2030. Two well-known cases serve to calibrate the two most optimistic scenarios: past trends observed in China (S2) and India (S3). Whereas the context and conditions for changes will be different in Africa (and across African countries) to the experience of China and India, these approximations serve to scale the potential outcomes against Africa’s expected employment challenges.

The exercise employs a simple three-step projection modelling based on past changes in labour market outcomes:

First, we use the shares in the labour force for each category of employment sector, employment status and occupation at country-year level, as obtained from ILOSTAT. We then calculate the changes in the shares of each employment category in Africa between 2000 and 2020, in China between 1990 and 2010 and in India between 2000 and 2020. These changes are added to the corresponding share of that category for Africa in 2020 to obtain the share of the category in Africa’s labour force by 2040.

Second, to project the size of the labour force, we extrapolate Africa’s labour force size (from the ILO growth rate) with the growth rate of the working-age population in Africa from 2020 to 2040 from the UN Department of Economics and Social Affair’s World Population Prospects 2018. In this setting, we implicitly assume a constant labour-force participation rate. The main projections employ the medium fertility variant.

Finally, the projected share of each employment category is multiplied by the projected labour force size to obtain the size of Africa’s labour force for each category.

Policy makers will need to prepare African youth for future challenges from digitalisation while addressing traditional shortcomings in the labour market. In particular, Africa’s youth will need to acquire critical skills to thrive in the digital era. Policy makers can play a critical role in expanding fintech adoption and preventing precarious working conditions for workers on e-platforms. At the same time, school-to-work transition programmes need rethinking, both in terms of focus and implementation, to better match youth with job opportunities.

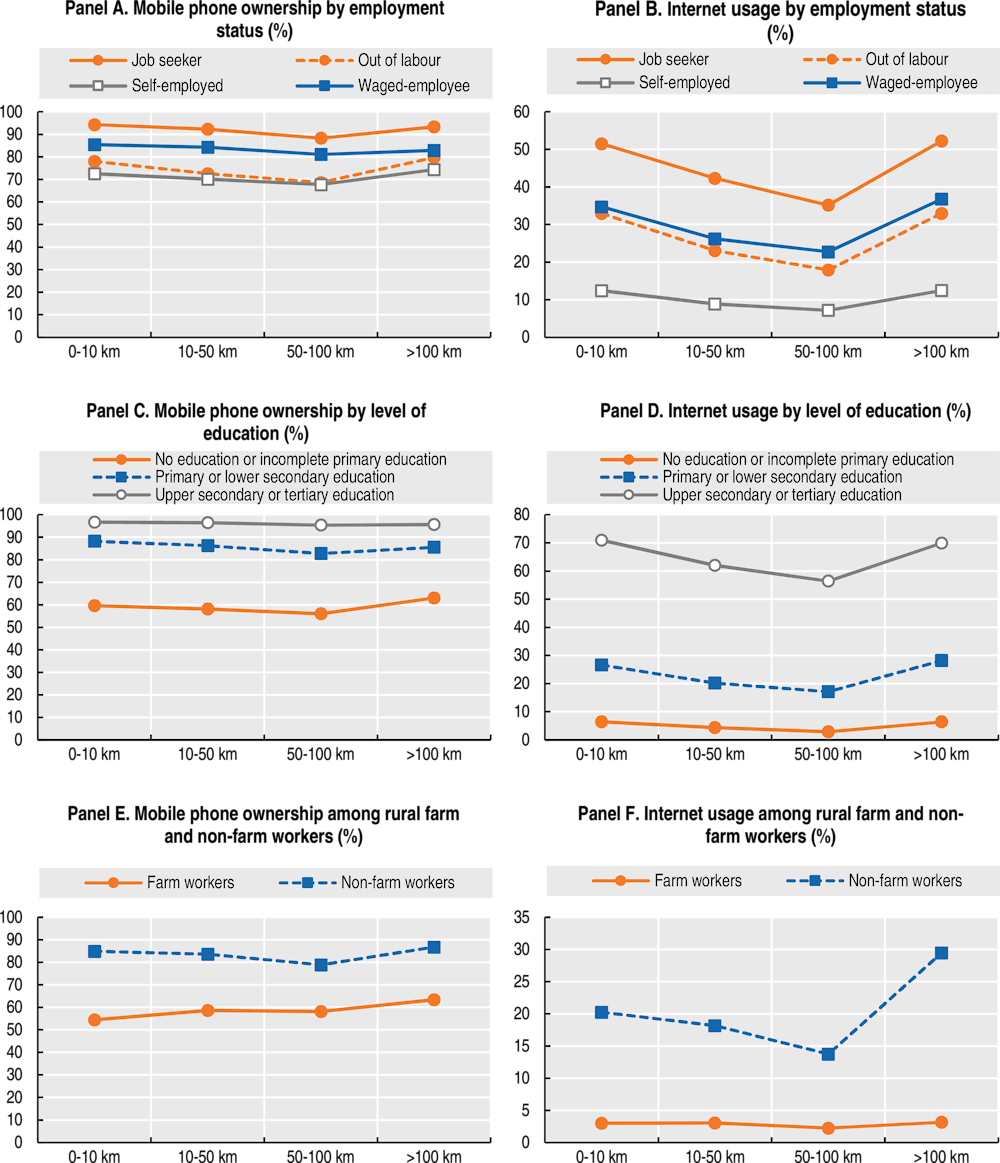

Beyond accessibility, other factors (such as skills, the affordability of services and the availability of suitable content) also limit the use of the Internet. The regular use of Internet services remains low among own-account workers even when they live in a connected geographic area. Only 16% of these workers regularly use the Internet, despite the fact that 80% of them own a mobile phone (Figure 1.10, Panels A and B). Similarly, the rate of regular Internet usage stands at 10% among people with less than a secondary education, while more than 60% of them own a mobile phone (Figure 1.10, Panels C and D). The rate of Internet usage is even lower than 10% among farmers (Figure 1.10, Panels E and F). Chapter 2 will further discuss priority areas for policy actions.

Figure 1.10. Mobile phone ownership and Internet usage in Africa by socio-economic group and proximity to a broadband backbone network, 2014-15

Note: The Afrobarometer survey from Round 6 includes 34 African countries in 2014-15. Panel A indicates the percentage of Afrobarometer’s respondents “using Internet at least once a day”. Using the module plug-in Nearest Nodes GIS (NN-GIS) in the Geographic Information System (GIS) software, we considered that a high-speed Internet connection is available for any Afrobarometer respondent “living within 10 kilometers of an operational fiber network node”.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on two datasets: Afrobarometer (2019), AfrobarometerRound 6 (database), and Many Possibilities (2020), The African Terrestrial Fibre Optic Cable Mapping Project (database).

High-growth start-ups and dynamic small and medium-sized enterprises need enabling regulations, financing and business services to compete in the digital era

Africa’s strong entrepreneurial spirit is an asset for job creation. Data from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor surveys conducted between 2013 and 2019 (GEM, 2020) show that Africa scores higher than Asian and LAC countries in both entrepreneurial intention and total early-stage entrepreneurial activity (TEA).

African enterprises have difficulty scaling up and innovating. In Africa, only 17% of early-stage entrepreneurs expect to create six or more jobs, the lowest proportion globally; for Asia, the proportion is 21%. About 19% of African early-stage entrepreneurs indicate that either they are conducting an innovative business or have high job creation expectations, compared to about 27% in Asia. Lockdowns and the potential of long-term economic fallout due to the COVID-19 pandemic further challenge the growth of these enterprises.

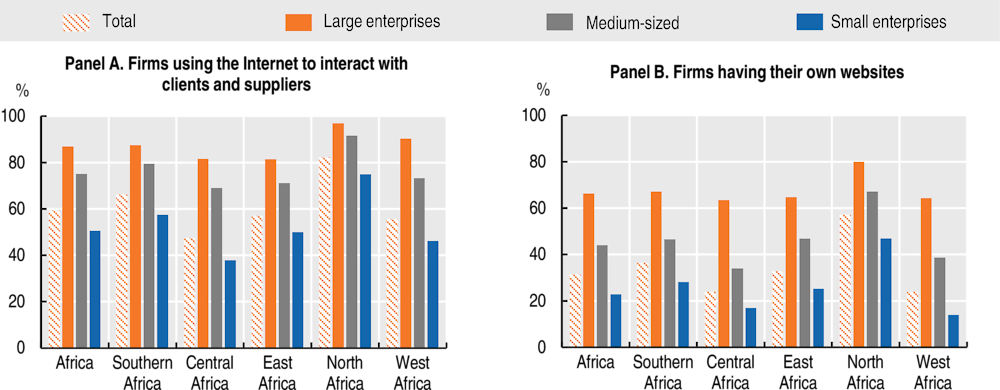

Increasing their growth and resilience requires stronger digital adoption, especially among MSMEs. Among firms from the World Bank Enterprise Surveys, only 59% of all African firms use the Internet to interact with clients and suppliers, and only 50% of small African firms do so (Figure 1.11, Panel A). The share of firms having their own website is even lower, at 31% among all African firms and 23% among small ones (Figure 1.11, Panel B). Estimated at USD 5.7 billion in 2017, the continent’s consumer e-commerce market is less than 0.5% of its combined GDP, compared to a global average of 4%. Barriers to digital adoption for MSMEs range from structural factors such as infrastructure to firm-specific factors such as financial and organisation capability.

Figure 1.11. Formal manufacturing and service firms in Africa that use the Internet and have websites

Source: Authors’ calculations based on World Bank (2020a), World Bank Enterprise Surveys (database), www.enterprisesurveys.org/en/data, using the latest data available for each country.

Government regulations, financing and business services can help innovative start-ups and dynamic SMEs to grow and compete in the digital age. In particular, AUC/OECD (2019) identified two promising groups of entrepreneurs that can benefit the most from using digitalisation to scale up and create new jobs:

High growth start-up. are small companies with great potential for growth based on their use of innovative technologies to disrupt or create new markets. While generally accounting for less than 10% of small businesses in developing countries, these ventures can contribute significantly to the economy through their high growth and innovation (CFF, 2018). In the case of Africa, this first group is mostly dominated by early-stage start-ups. Table 1.4 describes five examples of promising start-ups’ business models that tackle traditional constraints to development in Africa. With the right policy support, these types of innovative models can quickly spread across the continent.

Dynamic SME. deploy existing products or proven business models as they seek to grow through specialisation in niche markets, market extension or step-by-step innovations. Their growth and scale potential are moderate and depend on their access to regional and global markets. Policy makers can help these enterprises expand by tapping the potential of digital-enabled trade which remains nascent in Africa. Estimated at USD 5.7 billion in 2017, the continent’s consumer e-commerce market is less than 0.5% of its combined GDP, compared to a global average of 4%.

Table 1.4. Five examples of digital entrepreneurs in Africa and their business models

|

Company name |

Year of foundation |

Description |

Total funds raised (USD million) |

Business model |

Core market segment |

Main value proposition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mpost |

2016 |

The company converts phone numbers into formal postal addresses and allows users to use mobile phones to receive goods. The service is active in Kenya and plans to expand to Botswana, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda. |

2 |

Mobile postal services |

Postal services for “communal addresses” |

Helps eliminate the challenge of “communal addresses” in Africa |

|

Pargo |

2014 |

Pargo is a “click-and-collect” delivery platform that helps retailers sell and deliver goods to their customers using collection points of their choice. It currently operates in Botswana, Eswatini, Lesotho, Namibia and South Africa. |

1 |

Logistics and delivery online platform |

Logistics services for informal settlements and rural areas |

Helps retailers solve the challenges of last-mile deliveries |

|

SpacePointe |

2014 |

SpacePointe is a global financial technology company offering digital payment services to MSMEs in the informal sector, even in the most rural areas. The platform is active in West Africa and North America, with planned launches in Asia and LAC. |

1.2 |

Cloud-based payments platform |

Electronic payments collection for the informal sectors and rural areas |

Drives the adoption of electronic payments by the informal sector |

|

Eteyelo |

2015 |

Eteyelo develops applications allowing schools to automate pedagogical and school monitoring, management of school fees, and parent-school relationships. It was founded in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. |

n/a |

Mobile applications and web platform |

Digital data services for education systems |

Reduces the distance between all actors in the education system (students, teachers, parents, etc.) |

|

Swvl |

2017 |

Swvl offers an app that allows users to book fixed-rate affordable rides on its network of vans and buses. It now operates in Egypt and Kenya and plans to expand to Nigeria. |

76.5 |

Mobile platform for bus sharing |

Smart mobility services in urban areas |

Facilitates mobility in urban areas and helps reduce traffic congestion |

Note: n/a = not applicable.

Sources: Authors’ compilation and Crunchbase (2020), Crunchbase Pro (database).

Continental co-ordination remains key to achieving Africa’s digital transformation and Agenda 2063 flagship programmes

Co-ordination and prioritisation will help to deliver on the African Union’s ongoing flagship programmes for digital transformation

Digitalisation is a priority for Africa’s continental integration agenda. Through Agenda 2063 programmes, the African Union is leading over 15 initiatives to harness digital technologies and innovation for industry, trade, financial and payment services, education, agriculture, health and other sectors. In line with the Agenda 2063 aspirations, the intent is also to strengthen Africa’s position as a digital producer in the global ecosystem. Annex 1.A2 describes some of these flagship continental initiatives, their main objectives and key digital deliverables.

The African Union aims to achieve a digital single market by 203. (AUC, 2020a). To that purpose, the African Union Commission (AUC) developed the Digital Transformation Strategy for Africa (DTS) 2020-2030, which was endorsed by the Thirty-Sixth Ordinary Session of the African Union Executive Council held in February 2020. The DTS envisions an “integrated and inclusive digital society and economy in Africa that improves the quality of life of Africa’s citizens, strengthen[s] the existing economic sector, enable[s] its diversification and development, and ensure[s] continental ownership with Africa as a producer and not only a consumer in the global economy”. The DTS builds on existing initiatives and frameworks, such as the Policy and Regulatory Initiative for Digital Africa (PRIDA), the Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa (PIDA) and the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). The AUC is mobilising international development partners to achieve this digital transformation agenda:

Since April 2020, PRIDA, undertaken in collaboration with the Information Technology Union (ITU) and the European Union, has launched two working groups – one on “authorisation and licencing regimes” and another on “data protection and localisation” – with a view to assess regulations, identify best practices and harmonise them across the continent.

The Digital Economy for Africa (DE4A) initiative 2020-2030, undertaken with the World Bank Group, supports governments to invest strategically in digital infrastructure development, affordable services, skills and entrepreneurship. Currently, 15 investment operations are being deployed across the continent, and 29 others are in the pipeline.

The AUC is also running a programme to ensure Africa’s access to satellite-based technologies and related data services. The 2016 AU’s African Space Policy and Strategy aims to strengthen Africa’s use of outer space in critical sectors such as agriculture, disaster management, climate forecast, defence and security. Satellite-based wireless systems are a cost-effective way to develop or upgrade telecom networks in areas where user density is lower than 200 subscribers per square kilometre (AUC, 2019). Such wireless systems can be installed five to ten times faster and at a 50% lower cost than landline networks. The space economy is expanding and becoming increasingly global (OECD, 2019b). Other emerging technologies have the potential to address the challenges of distance in rural remote areas cost-effectively (see Chapter2).

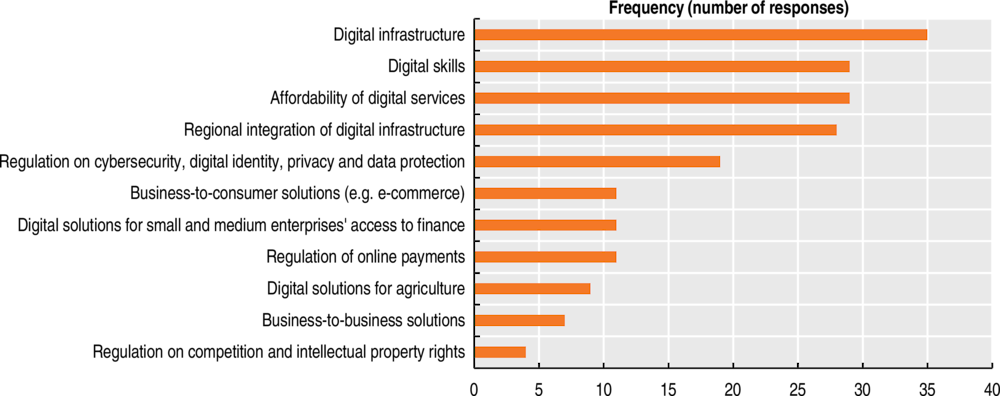

Confirming the orientations of the AUC’s flagship projects, the AUC/OECD 2020 Expert Survey underlined several areas for creating more and better jobs.Figure 1.12 summarises these priority areas by descending order. For example, regional and continental co-ordination on telecom roaming services, data regulation and cyber security is key for creating jobs. Taken together, these priority areas can also create the enabling environment for data value location and local content development in Africa. The remaining sub-sections highlight areas for which immediate actions are required.

Figure 1.12. Priority areas for regional and continental co-operation: Results from the AUC/OECD 2020 Expert Survey on Digitalisation in Africa

Notes: This figure shows answers to the survey question, “Which of the following areas of digitalisation do you think should be the priorities for regional and continental co-operation to help create more and better jobs in your region?”. It is based on responses from six (out of Africa’s eight) Regional Economic Communities and on individual assessment on 23 African countries. Respondents to the survey included policy makers, experts on digitalisation and representatives of private companies working in Africa’s telecom and digital activities. For this question, each respondent was asked to select five top priority areas out of an open-ended list of 15 areas, with an option to add any additional areas of their choice.

Source: AUC/OECD 2020 Expert Survey on Digitalisation in Africa.

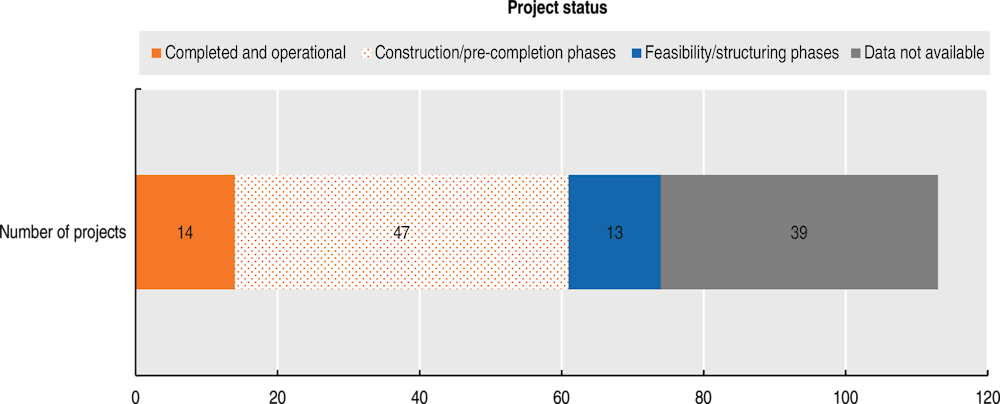

The continent must keep improving its access to international bandwidth infrastructure and services

Continental co-ordination is necessary to address bottlenecks in access to international bandwidth and to ensure affordability. The establishment of Internet exchange points − interconnecting terrestrial fibre backbones − is crucial to ensure Africa’s access to international digital services at lower prices. To this end, PIDA provides an important framework and monitoring tool. Of PIDA’s 114 ICT infrastructure projects, 42 aim to upgrade key Internet exchange points, 37 are dedicated to building new broadband fibre infrastructure across the continent and 34 intend to upgrade key existing terrestrial fibre backbones (AUDA-NEPAD, 2020). As of June 2020, 14 of PIDA’s ICT projects were completed and operational and 47 were under construction or in pre-completion stage (Figure 1.13).

In the next phase of Priority Action Plan for 2021-2030 of the PIDA, the objective is to select fewer, but more viable projects. The challenges related to project preparation risk compromising the realisation of quality infrastructure (OECD/ACET, 2020). The following issues stand out:

Projects serving the maximum number of unconnected intermediary cities need to be among the top priorities. Africa’s intermediary cities hold great promise for unlocking new opportunities for productive transformation, rural-urban linkages and job creation (see OECD/ACET, 2020).

Speeding up Internet exchange points programmes further. The volume of intra-regional traffic backhauled to subsea cable landing points increased by 37% in 2018 to reach 479 gigabytes per second (Gbps) thanks to the completion of new terrestrial cross-border links and to the expansion of capacity of others. This compares to 350 Gbps in 2017 and just 103 Gbps in 2014 (Hamilton Research, 2020).

Figure 1.13. The Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa flagship projects for the information and communications technology sector, by status

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on AUC/AUDA-NEPAD/AfDB (2020), PIDA Projects Dashboard (website), https://www.au-pida.org/pida-projects/.

Accelerating continental co-operation on roaming services, data regulation and digital security will increase intra-African trade and productive integration

Achieving a single pan-African market for goods and services, as targeted by the AfCFTA, holds great promise for growth and job creation. According to UNECA (2018), with the sole removal of tariffs on goods, the AfCFTA has the potential to increase intra-African trade by nearly a 40-50% increase between 2020 and 2040. According to UNCTAD (2018), the full operationalisation of the AfCFTA can result in a 1.17% increase in employment.

To move forward with the AfCFTA implementation, the African Union (AU) member states have started to negotiate protocols on investment, intellectual property rights and competition policy. Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, December 2020 was the target date for completion of these “phase two” negotiations. Negotiations towards a continental protocol on e-commerce and digital trade will start soon after the conclusion of the phase two negotiations (Muchanga, 2020). The establishment of a Pan-African Payment and Settlement System (PAPSS) is among the key digital deliverables. The PAPSS aims at allowing quick settlements of cross-border transactions through digitalised means. Ensuring quicker payments and settlements will enhance market liquidity and deepen national, regional, and continental capital and financial markets.

The AUC is also planning to launch a digital platform to help African SMEs scale up their operations. The AUC and the African eTRADE Group are collaborating to develop a continental e-commerce platform for SMEs. This platform will provide an online trading place and payment settlement for SMEs in order to facilitate cross-border trade and the delivery of products across the continent and reduce transaction costs (AUC/AeTrade Group, 2018).

A drastic reduction of roaming cost is required

Africa can learn from other regions about the use of roaming cost. (Bourassa et al., 2016). High roaming costs and related barriers to the use of data can severely reduce the benefits of the digital economy and slow the implementation of a regional digital single market (Cullen International, 2016, Cullen international, 2019). On the other hand, advancing a digital single market in the European Union had immediate benefits for consumers, businesses and online trade (see Box 1.4). Cross-border e-commerce in the EU has increased by more than 4%, and the volume of online trade by 5% (European Commission, 2019b). African countries should therefore quickly address the issue of intra-African roaming costs.

So far, progress for affordable or free intra-African roaming services remains limited. Only three of Africa’s Regional Economic Communities – the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), EAC and SADC – are on the way to reducing roaming costs. In 2017, ECOWAS member states approved a regulation to allow citizens travelling within the region to pay no additional roaming tariffs but roam at local rates. The initiative is currently in the implementation phase, and expected benefits for citizens’ welfare and for regional integration are significant (World Bank, 2018). The EAC also agreed to establish a “One Network Area” roaming rule in 2014 (ITU, 2016). In the SADC region, roaming tariffs as of 2020 should now be at “cost + 5%” according to a scheme adopted in 2014 (ITU, 2017, pp25-32). This scheme was agreed by the Communications Regulators’ Association of Southern Africa following the 2014 SADC Roaming Report.

Box 1.4. Reaping the full benefits of a digital single market: Insights from the case of the European Union

The European Union is among the most advanced examples in implementing a digital single regional market. In 2015, the European Commission presented the EU Digital Single Market Strategy, followed by a dedicated resolution by the European Parliament on 19 January 2016 (European Parliament, 2015). Since then, a number of landmark achievements have supported the construction of the European digital single market, including:

a) The end of roaming charges since 15 June 2017. The so-called roam-like-at-home approach enables all European citizens travelling in the Europe Union to use their mobile phones for calls, SMS and data for the same price as in their country of residence.

b) The cross-border portability of online content since April 2018. Europeans can access their online subscriptions to films, sports events, e-books, video games and music services while travelling to another member state.

c) The modernisation of data protection since 25 May 2018. The data protection reform is a legislative package that includes the General Data Protection Regulation.

d) The removal of geo-blockingbarriers to e-commerc. since March 2018. The new rules ensure consumers can access goods and services online without concern for geographically based restrictions to e-commerce, or cross-border transactions.

Sources: Authors’ compilation based on European Commission (2019a), “Commission report on the review of the roaming market”, and European Commission (2019b), A Digital Single Market for the Benefit of All Europeans.

Accelerating the continental harmonisation of data regulatory frameworks is essential

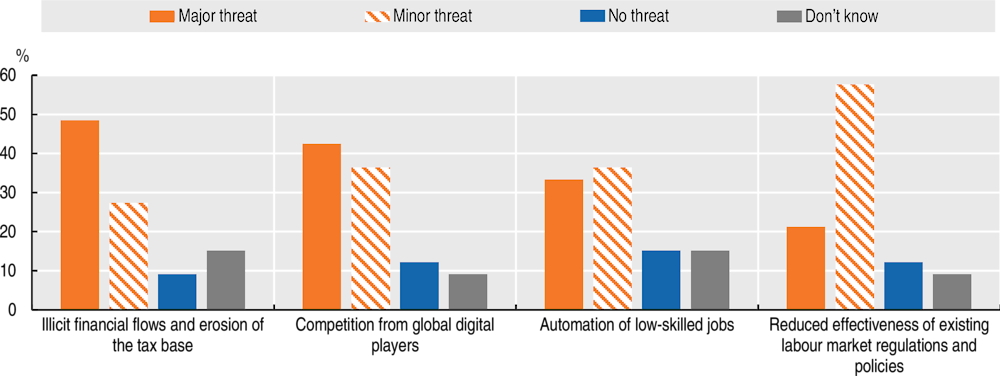

Given the international scope of digital data value chains, African countries should not cling to isolated national frameworks for data regulation. First, greater regulatory coherence across countries is required to navigate global digital data. Despite some regional and continental efforts, the national data regulatory framework in most African countries is far below the required level for the digital era. Second, evidence from a sample of 64 countries between 2006 and 2016, shows that isolated attempts to restrict the cross-border movements of data or require local storage of data inhibit trade in services and reduce the productivity of local firms (Ferracane and Marel, 2018). Third, a single continental framework would be more powerful and simpler to understand. In Europe, for example, since the EU’s General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR) came into effect in May 2018, any company wishing to conduct business within the EU must comply with a number of similar principles and guidelines to ensure privacy and protection of personal data. As of today, only 28 countries in Africa have comprehensive personal data protection legislation in place (UNCTAD, 2020c). Experts already see this weakness as a major risk to Africa’s digital development (Figure 1.14).

Figure 1.14. Risks associated with digitalisation for creating jobs in Africa: Results from the AUC/OECD 2020 Expert Survey on Digitalisation in Africa

Notes: This figure shows answers to the survey question “How do you rate the following possible risks associated with digitalisation for jobs’ creation in your country (or region)?”. It is based on responses from six (out of Africa’s eight) Regional Economic Communities and on individual assessment of 23 African countries.

Source: AUC/OECD 2020 Expert Survey on Digitalisation in Africa.

Digital security calls for urgently improving continental co-operation

Only a fifth of African countries have a legal framework for cybersecurity (digital security), while just 11 countries have adopted substantive laws on cybercrime (digital security incidents. (Farrah, 2018; OECD, 20156). In 2014, the 23rd Assembly of the AU Heads of State and Government adopted a Convention on Cybersecurity and Personal Data Protection as a first step towards continental co-operation. Yet, as of June 2020, only 14 AU member states had signed it, and 5 had ratified it (Ghana, Guinea, Mauritius, Namibia and Senegal). This is still far from the 15 ratifications required for the Convention to enter into force (AUC, 2020b).

Why is co-operation urgent for digital security? The cost of cybercrime in Africa is increasing and brings the risk of holding back Africa’s digital revolution (Farrah, 2018). Several assessments show that Africa’s online ecosystem is one of the most vulnerable in the world (Serianu, 2017; KnowBe4, 2019). Serianu (2017) estimates that the cost of cybercrime in Africa was about USD 3.5 billion in 2017, with Nigeria and Kenya alone suffering losses of USD 649 million and USD 210 million, respectively. In addition, the rise of digital technologies poses a host of new and more complex challenges to country-level regulators, including taxation in the digital age, digital security, privacy, personal data protection and cross-border flows of data. The intensity of these challenges arises from the combination of the fast-evolving nature of technology, the need for governments to respond with “fit-for-purpose” regulatory frameworks and enforcement mechanisms, and their global reach and cross-border nature (OECD, 2019c). Therefore, lawyers and experts within government regulatory agencies cannot deal with these issues in isolation.

References

2AfricaCable (2020), “2Africa: A transformative subsea cable for future internet connectivity in Africa announced by global and African partners”, Press release, 14 May 2020, www.2africacable.com/ (accessed 20 July 2020).

AfDB/OECD/UNDP (2017), African Economic Outlook 2017: Entrepreneurship and Industrialisation, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/aeo-2017-en.

AfDB/OECD/UNDP (2015), African Economic Outlook 2015: Regional Development and Spatial Inclusion, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/aeo-2015-en.

AFRILABS and Briter Bridges (2019), “Building a conductive setting for innovators to thrive: A qualitative and quantitative study of a hundred hubs across Africa”, https://briterbridges.com/briterafrilabs2019 (accessed 27 July 2020).

Afrobarometer (2019), Afrobarometer (database), https://afrobarometer.org/fr (accessed 21 July 2020).

Ahmed, T. (2020), “Covid-19 expected to accelerate automation uptake”, fDi Intelligence, www.fdiintelligence.com/article/77816 (accessed 23 July 2020).

AUC (2020a), The Digital Transformation Strategy for Africa (2020-2030), African Union Commission, Addis Ababa, https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/38507-doc-dts-english.pdf.

AUC (2020b), “List of countries which have signed, ratified/acceded to the African Union Convention on Cyber Security and Personal Data Protection”, African Union Commission, Addis Ababa, https://au.int/en/treaties/african-union-convention-cyber-security-and-personal-data-protection (accessed 20 July 2020).

AUC (2019), African Space Strategy: For Social, Political and Economic Integration, African Union Commission, Addis Ababa, https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/38507-doc-dts-english.pdf.

AUC/AeTrade Group (2018), “African Union Commission and African E-Trade Group unleash the power of e-commerce in Africa”, Joint Press Release, Addis Ababa, https://au.int/sites/default/files/pressreleases/35219-pr-press_release_-_au-african-e-trade.pdf (accessed 20 July 2020).

AUC/AUDA-NEPAD/AfDB (2020), “PIDA projects dashboard”, Virtual PIDA Information Centre, Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa and African Union Development Agency-NEPAD, www.au-pida.org/pida-projects/ (accessed 20 July 2020).

AUC/OECD (2019), Africa’s Development Dynamics 2019: Achieving Productive Transformation, OECD Publishing, Paris/African Union Commission, Addis Ababa, https://doi.org/10.1787/c1cd7de0-en.

AUC/OECD (2018), Africa’s Development Dynamics 2018: Growth, Jobs and Inequalities, OECD Publishing, Paris/African Union Commission, Addis Ababa, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264302501-en.

Baldwin, R. and E. Tomiura (2020), “Thinking ahead about the trade impact of COVID-19”, in Economics in the Time of COVID-19, VoxEU, CEPR Press, London, pp. 59-71, https://voxeu.org/content/economics-time-covid-19 (accessed 23 July 2020).

Bashir, S. (2018), “The journey to land digitization in Kenya”, Transparency International-Kenya https://tikenya.org/the-journey-to-land-digitization-in-kenya/.

Benz, S., F. Gonzales and A. Mourougane (2020), “The Impact of COVID-19 international travel restrictions on services-trade costs”, OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 237, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/e443fc6b-en.

Bourassa, F., et al. (2016), “Developments in International Mobile Roaming”, OECD Digital Economy Papers, No. 249, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5jm0lsq78vmx-en.

BPESA (2019), GBS Sector Job Creation Report, Quarter four 2019, Business Process Enabling South Africa, www.bpesa.org.za/component/edocman/?task=document.viewDoc&id=213 (accessed 24 July 2020).

Bright, J. (2019a), “Nigerian logistics startup Kobo360 raises $30M backed by Goldman Sachs”, Techcrunch, 14 August 2019, https://techcrunch.com/2019/08/14/nigerian-logistics-startup-kobo360-raises-30m-backed-by-goldman-sachs/ (accessed 27 July 2020).

Bruegel (2020), The Fiscal Response to the Economic Fallout from the Coronavirus (dataset), https://www.bruegel.org/publications/datasets/covid-national-dataset/ (accessed 15 June 2020).

Bukht, R. and R. Heeks (2017), “Defining, conceptualising and measuring the digital economy”, Development Informatics Working Paper Series, Paper No. 68, University of Manchester, UK, https://diodeweb.files.wordpress.com/2017/08/diwkppr68-diode.pdf (accessed 27 July 2020).

Cariolle, J., M. Le Goff and O. Santoni (2019), “Digital vulnerability and performance of firms in developing countries”, Working Papers, No. 709, Banque de France, www.banque-france.fr/sites/default/files/medias/documents/wp_709.pdf (accessed 27 July 2020).

Central Bank of Kenya (2020), Mobile Payments (database), www.centralbank.go.ke/national-payments-system/mobile-payments/ (accessed 20 July 2020).

Central Bank of Kenya (2016), “Bank supervision annual report 2016”, https://www.centralbank.go.ke/uploads/banking_sector_annual_reports/323855712_2016%20BSD%20ANNUAL%20REPORT%20V5.pdf (accessed 20 July 2020).

CFF (2018), The Missing Middles: Segmenting Enterprises to Better Understand Their Financial Needs, The Collaborative for Frontier Finance, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/59d679428dd0414c16f59855/t/5bd00e22f9619a14c84d2a6c/1540361837186/Missing_Middles_CFF_Report.pdf.

Crunchbase (2020), Crunchbase Pr. (database), www.crunchbase.com (accessed 28 June 2020).

Cullen International (2019), Regional and Sub-Regional Approaches to the Digital Economy: Lessons from Asia Pacific and Latin America, CAF, Caracas, https://scioteca.caf.com/handle/123456789/1381.