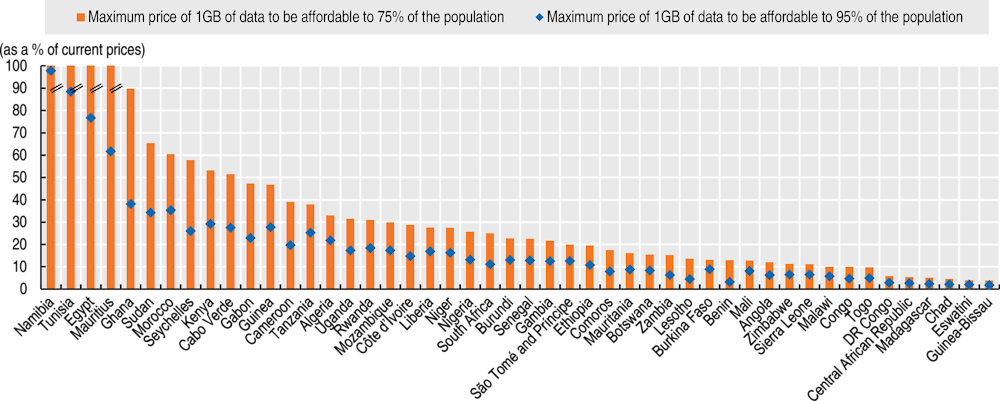

This chapter discusses public policies that can use Africa’s digital transformation to trigger large-scale job creation and achieve Agenda 2063 objectives. In each of the three policy domains presented, the chapter highlights policy levers and the most relevant practices that African policy makers can mobilise at local, national, regional and continental levels. The first section focuses on bridging the digital divide through place-based policies. The second section presents policy priorities to upgrade Africa’s large informal sector, including skills development, labour regulations to deal with emerging forms of employment and digital solutions for financial inclusion. The last section examines how policy makers can empower Africa’s small and medium-sized enterprises and start-up ecosystems to compete and innovate in the digital world.

Africa’s Development Dynamics 2021

Chapter 2. Policies to create jobs and achieve Agenda 2063 in the digital age

Abstract

In brief

Three sets of policies can help policy makers harness Africa’s digital transformation to create a massive number of jobs across the continent and fulfill the ambitions of the African Union’s Agenda 2063:

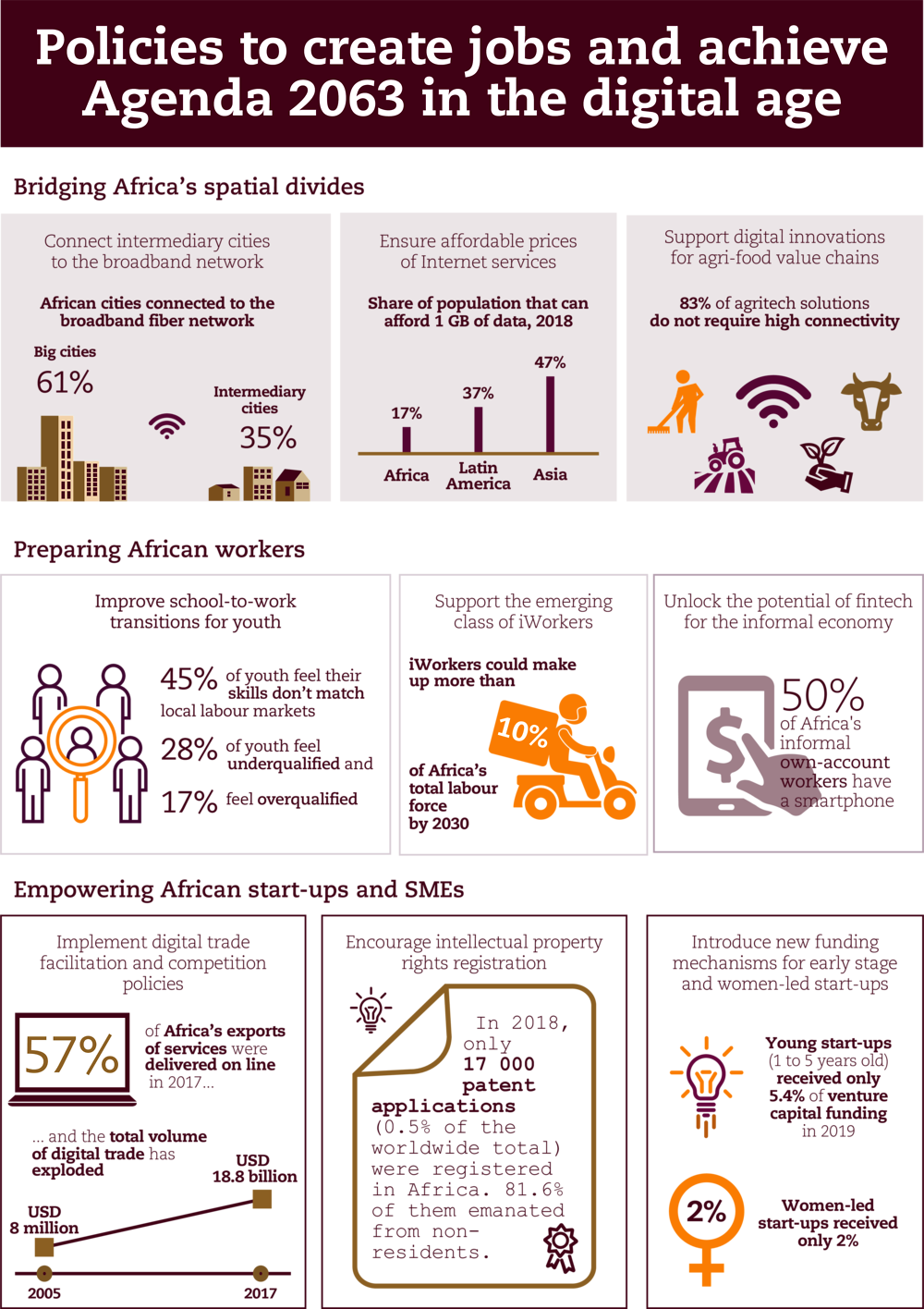

First, place-based policies will be necessary to unleash employment opportunities beyond large urban areas. Accelerating the development of broadband infrastructure in intermediary cities can yield high returns, as 73% of Africans will continue to live in rural areas and intermediary cities by 2040. Supporting digital innovations for rural development, expanding last-mile access to the Internet and reducing the costs of Internet services are complementary components to turn digital access into job opportunities. In most African countries, reducing current prices of data services by half would make them affordable for 75% of the population.

Second, making digitalisation benefit informal workers will require equiping youth with adequate skills for the digital era, preventing precarious working conditions for own-account workers on e-platforms, and expanding the availability and adoption of fintech solutions for the informal economy. A test-and-learn approach can create a policy environment that is fit for purpose, exemplified by recent regulatory sandboxes and regulator technologies applied across African countries.

Third, policy makers must support Africa’s dynamic small and medium-sized enterprises and start-up ecosystems so they can prosper and actively participate in the digital age. Building an African digital single market is critical. Governments should deepen regulatory harmonisation, put in place the enabling environment to develop business services for firms, enable smaller firms to tap digital-enabled trade opportunities, facilitate intellectual property registration and develop mechanisms to finance start-ups. Though venture capital funding for Africa’s start-ups grew sevenfold between 2015 and 2019, 85% of it went to just four countries in 2019.

Policies to create jobs and achieve Agenda 2063 in the digital age

Bridging Africa’s spatial divides will unleash job opportunities beyond large cities

Accelerating broadband infrastructure development in intermediary cities can unlock high-potential regional supply chains

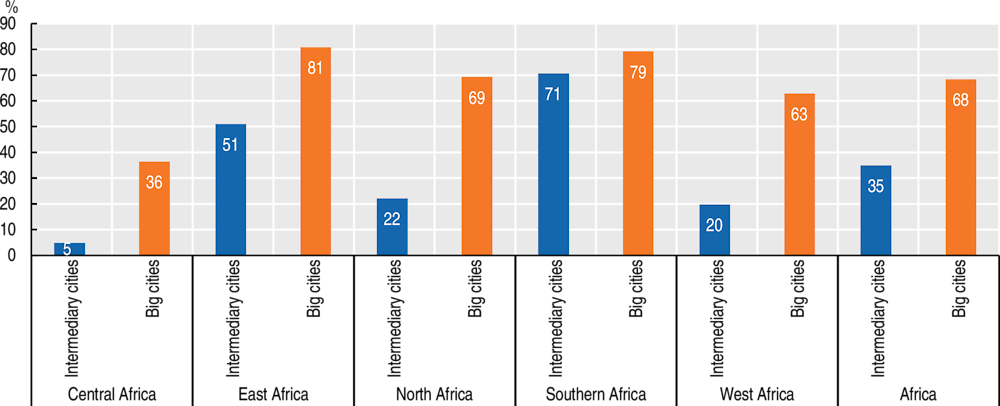

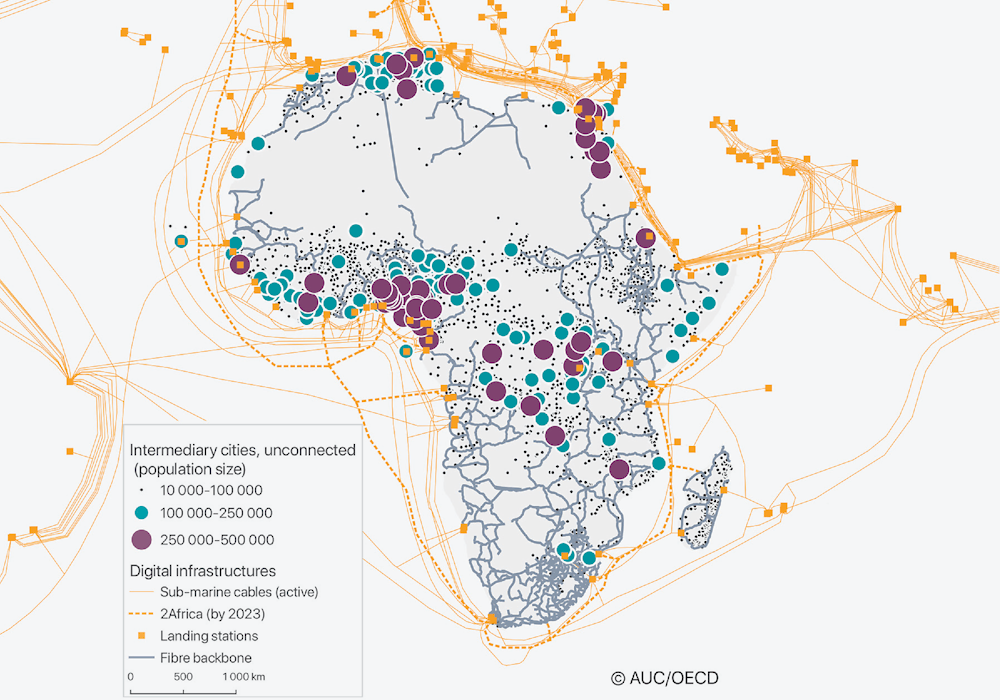

The majority of Africa’s intermediary cities are located far from a high-speed terrestrial fibre-optic network. In Central Africa, only 5% of the intermediary cities are within 10 kilometres (km) of the backbone network, compared to 36% of the big cities (Figure 2.1). In Southern and East Africa, on the other hand, the backbone network has expanded further across the urban networks, with respectively 71% and 51% of the intermediary cities connected to the terrestrial fibre-optic broadband network. Box 2.1 explains the methodology used to analyse the spread of Africa’s broadband communications infrastructures across space. Annex 2.A1 shows the results on a map and reports the unconnected cities by population size.

Figure 2.1. Share of cities within ten kilometres of the terrestrial fibre-optic network in Africa’s regions, 2019

Box 2.1. A brief description of the spatial analysis on the spread of digital technologies in Africa

This report combined three geolocalised datasets to explore the spread of digital technologies across African regions as well as their link with local economic development and jobs:

First, we mobilised the geocoded maps of terrestrial fibre-optic backbone networks in Africa provided by AfTerFibre’s Network Startup Resource Center (Many Possibilities, 2020).

Second, we overlapped these datasets with the Africapolis database, which geolocalises all African urban agglomerations with more than 10 000 inhabitants in 2015 (OECD/SWAC, 2019). This helped us identify the distance of each agglomeration to fibre broadband backbone networks.

Finally, we matched these with geocoded subnational data from Afrobarometer surveys. This allowed us to compare various socio-economic characteristics and employment profiles of African households according to their distances to a backbone network during the 2014-15 period.

Investing in high-speed communications infrastructures for intermediary cities can connect a large population to the terrestrial fibre-optic network. Nearly six in ten (57%) of all African cities that are not connected to the network lie within only 50 km of it; in 2015, they accounted for a total estimated population of 146 million. Attracting private investments for broadband connectivity for small towns and intermediary cities would allow resource-constrained governments to benefit from strong multiplier effects. According to an expert survey by the African Union Commission and the OECD, digitalisation can help unleash new opportunities for direct job creation in large and intermediary cities, while these opportunities are rather limited in rural areas (Figure 2.2). In addition, broadband connectivity brings positive spillovers in the connected regions, in terms of both employment and firms’ productivity (Sorbe et al., 2019).

Figure 2.2. Opportunities brought by digitalisation for creating jobs in Africa according to geographical situation and social group: Results from the AUC/OECD 2020 Expert Survey on Digitalisation in Africa

Note: This figure shows answers to the survey question, “How do you rate the following opportunities of digitalisation for job creation in your country or region?” It is based on responses from six (out of Africa’s eight) Regional Economic Communities and on individual assessments of 23 African countries. Respondents to the survey included policy makers, experts on digitalisation and representatives of private companies working in Africa’s telecom and digital activities.

Source: AUC/OECD 2020 Expert Survey on Digitalisation in Africa.

As Africa’s rural population continues to grow, intermediary cities can act as transmission hubs that serve the rural hinterland, strengthen rural-urban linkages and drive rural transformation. Africa’s rural populations will continue to grow in absolute terms at least beyond 2050 (see Chapter 1). Increasing productive activities – such as food processing, agricultural inputs supply services, logistics or warehousing facilities – in intermediary cities will be crucial to connecting Africa’s rural-urban supply chains (Traoré and Saint-Martin, 2020; Minsat, 2018). This will also help local small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) meet regional demand. Firm-level data on Côte d’Ivoire show that when the location quotient, or concentration, of firms increases by 10% in intermediary cities like Daloa or in Odienne, firms operating there increase their sales by 15-17% (Fall and Coulibaly, 2016).

Greater investment in connecting border cities to the communications infrastructures could increase opportunities for transborder activities, jobs creation and economic development. The proximity of border cities is spurring promising transborder co-operation. Many of the intermediary cities in Africa are located within 50 km of national borders.1 Neighbouring countries are creating cross-border special economic zones (SEZs). In 2018, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire and Mali launched the first cross-border SEZ in Africa – called SKBO – with the aim of encouraging agro-industrial and mining companies to set up in the area spanning between the cities of Sikasso, Korhogo and Bobo Dioulasso (AUC/OECD, 2018). Similarly, in 2019, Ethiopia and Kenya announced their intention to convert the Moyle region into a cross-border free trade zone (UNCTAD, 2019).

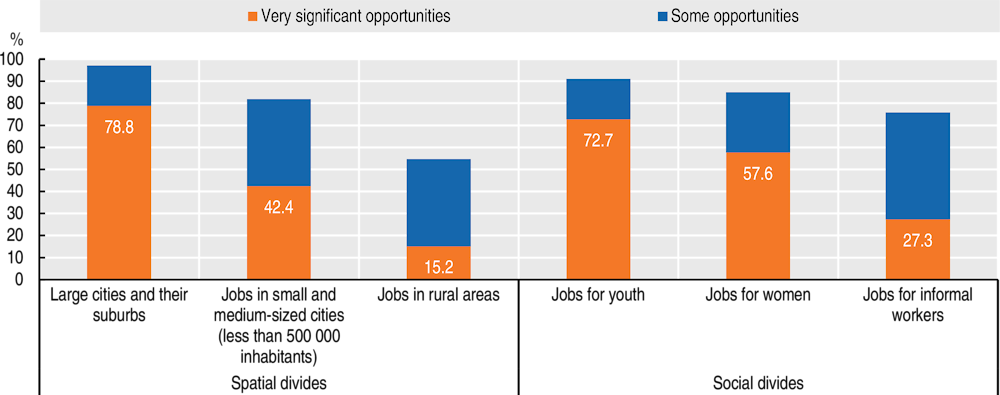

Governments need to ensure last-mile connectivity

Affordability of data and Internet-enabled devices is an essential complement to infrastructure development for digitalisation to benefit a larger number of African households (Box 2.2). Subscriptions to mobile phones have steadily increased; however, the high cost of data services is the main factor limiting the use of Internet services. Among the Internet users surveyed in ten African countries in 2017, over a third (36%) stated the cost of data as the main limitation to Internet use (see Figure 2.3). Of those who do not use the Internet at all, the cost of Internet-enabled devices is the second-most stated barrier to accessing the Internet (23%); right after the lack of awareness about the Internet. Similarly, research on mobile financial services shows that barriers to using Internet services include other factors such as lack of money or regular income, low levels of digital literacy and limited knowledge of basic financial concepts. For instance, self-exclusion may also occur due to low levels of financial and digital literacy (OECD, 2018a). Usually, these barriers are higher in remote and rural areas.

Figure 2.3. Main limitations to Internet use in selected African countries, 2017

Note: The ten African countries considered included Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Mozambique, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, South Africa, Tanzania and Uganda.

Source: Adapted from Gillwald and Mothobi (2019) based on RIA After Access Survey data, 2017.

Box 2.2. Improving the indicators of data affordability for African countries

To achieve development objectives, the UN and the AU formulated pricing targets for digital data:

In 2011, the UN Broadband Commission set a global target for broadband affordability. Entry-level broadband (defined as 500MB of mobile data) should cost 5% or less of average national income per capita (as measured by GNI per capita). In 2018, it revised this target from a price threshold of 5% to less than 2% of monthly GNI per capita, and doubled the data allowance from 500MB to 1GB.

In 2020, the African Union set the following target: “By 2030 all our people should be digitally empowered and able to access safely and securely to at least (6 MB/s) all the time where ever they live in the continent at an affordable price of no more than USD 1 cent per MB (i.e. USD 10 for 1GB)” (African Union, 2020).

Taking stock of the dearth of quality data covering a large number of African countries, and of African stakeholders’ targeted policy objectives, this report develops a specific method to estimate what would be the cost of nearly universal access to digital data on the African continent. The method aims to estimate the maximum price of 1GB of data that would be affordable (defined as no more than 5% of their monthly income) for 75% and 95% of the population, respectively. It relies on data from Research ICT Africa (RIA), which cover 48 African countries and are available quarterly from 2014 onwards. For this exercise, it uses country averages for 2018, and then applies the following steps:

1. Convert annual prices from current USD to USD PPP 2011 using World Bank GDP deflator to make them comparable across African countries.

2. Compute how much an individual should earn monthly so that the current price of a 1GB bundle would only represent 5% of its monthly income.

3. Use the World Bank’s online analysis tool for global poverty monitoring (PovcalNet) to assess the percentage of people living below these income thresholds in each country.

4. Use the reversed methodology to assess the price of 1GB bundle in each country so that a large majority (75% or 95%) of the population can afford it.

Moving forward, African countries and regional institutions should scale-up efforts to collect more granular data to assess affordability and to ensure comparability. To have a full picture, policy makers must examine a range of indicators which reflect the status of individual broadband markets. Since 2000, the OECD, for example, has developed a comprehensive methodology for comparing broadband data prices experienced by consumers in its member countries. This methodology uses a “basket” approach where a consumption pattern describes different types of users, and the prices of broadband services from each provider covered help to calculate the resulting cost for each type of user (OECD, 2017a; OECD, 2020d). The granularity of the data collected allows separate treatment of data and voice offers from data offers only. The baskets are reviewed and revised periodically (every 3 years on average) as consumption patterns change and the digital markets evolve over the time. A new update is to be released by end-2020 (OECD, forthcoming). More information can be found at www.oecd.org/sti/broadband/broadband-statistics/.

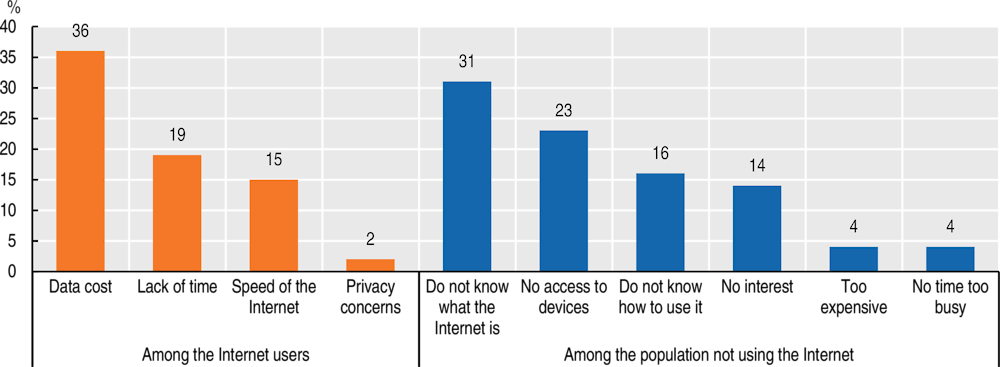

In 38 out 48 African countries for which data are available, current prices of data services would have to be halved to be affordable for 75% of the population and would need to be reduced even further to achieve universal affordability. Despite their gradual decrease over the past decades, data services on the continent are the most expensive in the world. In 2018, only 17% of Africa’s population could afford one gigabyte (1 GB) of data, compared to 37% in Latin America and the Caribbean, and 47% in Asia (Nguyen-Quoc and Saint-Martin, forthcoming). In Mozambique, about six in ten households stated that they could not afford the necessary devices required to access the Internet (Gillwald and Mothobi, 2019). This share is four in ten in Uganda and three in ten in Rwanda. Only in four countries (Egypt, Mauritius, Namibia and Tunisia) are today’s prices affordable to three-fourths of the population (Figure 2.4).

Figure 2.4. Maximum price of 1GB of data to be affordable to 75% and 95% of the population in selected African countries, 2018 (as a percentage of current prices)

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Research ICT Africa (2019), Research ICT Africa Mobile Pricing (RAMP) (database), and World Bank (2020), PovcalNet (database).

Ensuring sound competition among telecommunication providers can enhance diversity and affordability of last-miles services. Spectrum allocation policies, which assign scarce radio frequency bands to operators, should facilitate licensing procedures for telecom service providers aiming to cover underserved populations or geographic areas. For example, allowing small operators to use virtual or mobile network facilities can improve product diversity and market competition. Countries can also exploit vacant radio spectrum bands, previously used by television broadcasting, for broadband Internet transmission, as the successful tests in Malawi and four other southern African countries demonstrate (see Chapter 3). Microsoft has also been experimenting with TV White Spaces since 2009 and has implemented pilot projects to connect communities in countries such as Botswana, Colombia, Ghana, Kenya, Namibia, the Philippines, Tanzania, South Africa, the United Kingdom and the United States (OECD, 2018e).

Innovative public-private alliances can help design cost-effective solutions to connect less densely populated rural areas (OECD, 2019f). SES, the world-leading satellite operator, estimates that about 30% of Africa’s rural population may never be technically reachable with the terrestrial fibre-optic network in a cost-effective way (AU-EU DETF, 2019). In Nigeria, for example, Internet service providers find that extending service to rural areas via the terrestrial fibre-optic network is commercially unviable due to low commercial returns, higher maintenance cost, and the lack of reliable grid electricity supply (World Bank, 2019). To expand coverage in their rural areas, some countries are encouraging private investment through a variety of incentives and new partnerships.

For example:

In Algeria, Ghana, Kenya and Nigeria, the public sector partnered with mobile telecom companies and with the telecommunications equipment providers to bring cost-effective mobile broadband services to their rural populations, via microwave systems called RuralStart 2.0 (GSMA, 2018; ITU, 2020).

MTN, the pan-African telecom operator, announced in 2019 that it would deploy more than 5 000 Open Radio Access Networks (Open-RAN) sites across its 21 African operations to bring 2G, 3G and 4G connectivity to areas that were previously under-connected (Parallel Wireless, 2019). Guinea and Uganda are already benefiting from this technology.

Governments can use Universal Service and Access Funds (USAFs) as a policy vehicle for rural connectivity. Thirty-seven African countries created USAFs – special programmes with funding schemes for universal Internet access and services. USAFs are typically financed through mandatory contributions by mobile network operators and other telecom companies with the aim to expand connectivity and digital services to underserved locations (GSMA, 2014). A recent review (Thakur and Potter, 2018) found that governments can better use USAFs. About USD 408 million, or 46% of funds collected across Africa, were still unspent by end-2016. Some countries, such as Nigeria and Tanzania, have used their USAFs to promote rural connectivity:

Nigeria has established the Universal Service Provision Fund, which invests in Community Resource Centers in semi-urban and rural areas. It provides subsidies for operators to expand their broadband service in these areas through the Rural Broadband Initiative.

Tanzania, in partnership with two telecom companies (World Telecom Labs and Amotel), has used part of its USAF to connect its villages with over 1 500 inhabitants via a microwave-based solution. The system went live in 2016 and connected 2.5 million rural people for the first time.

Greater continental co-operation under the direction of the Digital Transformation for Africa Strategy is necessary. Transborder co-operation can lower transit costs and interconnection rates, yielding benefits for both coastal and landlocked countries. Prohibitively high tariffs can restrain access to backhaul infrastructure (i.e. subsea cables and international bandwidth) for small service providers (see Chapter 1).

Policies need to identify and support the most promising digital innovations for rural development

New technologies such as smart contracts, real-time payments solutions and distributed ledger technologies (also known as blockchain) can fundamentally transform the agricultural sector and help address the specific challenges of smallholders. Smallholder agriculture and rural non-farm activities are central to reduce poverty and enhance the livelihoods of large numbers of African people; still, they face significant obstacles to access markets and generate sufficient income (Fan and Rue, 2020; Poole, 2017). A stocktaking exercise of these so-called Disruptive Agricultural Technologies highlighted that their focus ranges from enhancing agricultural productivity (32%) to improving market linkages (26%) and, to a lesser extent, data analytics (23%) and financial inclusion (15%). The top five countries with the highest activities in agricultural technology, or agritech, are Kenya, South Africa, Nigeria, Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire. Over 83% of agritech solutions do not require high connectivity and can operate with intermediate connectivity (Kim et al., 2020).

Policies can use a number of channels to diffuse digital innovations for rural development

Scaling up smart contracts and real-time payments solutions can enhance rural-urban supply chains. Several examples show how smart contracts and digital payments help better match demand and supply, reducing the number of intermediaries, offering higher prices and stable markets to farmers and reliable supplies to vendors. For example, Kenya’s mobile-based platform Twiga Foods, launched in 2014, serves around 2 000 outlets a day through a network of 13 000 farmers and 6 000 vendors (Bright, 2019). However, policies must help scaling up beyond single business cases.

Digital solutions can provide farmers with location-specific agronomic information and tailored advisory services at lower costs. Agritech and data-related start-ups are on the rise across the continent: Farmerline and Esoko in Ghana, Data Science in Kenya, Korbitec in South Africa, OroData in Nigeria and Eduweb in Kenya (UNECA, 2018). Governments can collaborate with tech companies to diffuse affordable and user-friendly solutions for agricultural extension services and spread the best farming practices. Here are some case studies, which stakeholders could use for mutual learning and scaling up:

Ethiopia’s Agricultural Transformation Agency has developed the Ethiopian Soil Information System, or EthioSIS. This system provides a digital map analysing the country’s soils down to a resolution of 10 km by 10 km which it updates regularly (Annan, Conway and Dryden, 2015; das Nair and Landani, 2020). Soil mapping has resulted in yield improvements of up to 65%, thanks to more informed use of fertilisers and better soil management.

In Kenya, DigiFarm for Consumer allows financial service providers to connect to its platform, access farmers’ data and offer them services on the hub (GSMA, 2019a).

In Malawi, weather-based index insurance, the provision of drought-tolerant seeds and ICT-enabled weather information services assist farmers. Some 140 000 rural smallholder households have benefited.

In Uganda, the MUIIS initiative provided weather forecasts, agronomic information and access to financial services to smallholder farmers, increasing yields and incomes for over 200 000 farmers.

New digitally-enabled business models can help improve product traceability for international trade. In Botswana and Namibia, radio frequency identification (RFID) chips are being used in the beef sector to better track and monitor animals’ health status and movement (Deichmann et al., 2016; World Bank, 2016). Blockchains offer promising solutions for real-time tracking and tracing of the origins of products at lower costs (OECD, 2019a). For example, Anheuser-Busch InBev applies blockchain systems to collect geo-location tags and match farmers’ profiles for each transaction in the supply chain (AB-InBev, 2019). Although promising, some challenges remain to be addressed to scale up the use of blockchain technologies in Africa’s agri-food value chains (Box 2.3).

Other promising innovations for agricultural development include shared-economy models and digital tools for land rights. Pay-as-you-go (PAYGO) renting models allow users to pay for lumpy investment goods in small increments (CTA, 2019). Examples include ColdHubs (for cold chains in Nigeria), Kobiri (for the rent of mechanised equipment in Guinea) or SunCulture (for solar irrigation pumps in Kenya). In partnership with the local authorities and blockchain-based start-ups, countries such as Ghana, Rwanda and Zambia have developed new solutions to manage land titling (see Annex 2 A2 for further details).

Box 2.3. Key challenges to applying blockchains in the agri-food value chain

A blockchain is a digital database containing information such as records of individuals, land and financial transactions that can be simultaneously used and shared within a large decentralised, publicly accessible network (i.e. a distributed ledger). It stores transactions between parties efficiently and in a verifiable and permanent way (CTA, 2019). All users on the network hold an identical copy of the ledger, which makes the blockchain theoretically undisputable and tamper-proof (OECD, 2018b).

Despite the potential to transform the agri-food industry in Africa, scaling up blockchain-enabled solutions meets important challenges:

Technical challenges. The high-energy consumption, poor cost efficiency and transaction speed of blockchains pose challenges to its scalability. Another challenge is to link public and private ledger types, as they use different systems. Leonard (2019) recently projected that 90% of blockchain-based supply chain projects would stall by 2023 due to technological concerns.

Regulatory challenges. On an institutional and regulatory level, another huge challenge is merging the current complex legal frameworks − that govern rights of ownership and possession along supply chains and across borders − with blockchains and smart contracts. As transparency is a fundamental element of blockchains, there should be careful consideration of the types of data to protect and disclose and of ways to incentivise supply chain actors to share data.

Building digital capacity challenges. The complexity of blockchain systems requires building digital capacity throughout the whole agricultural ecosystem. In the 2017 Geodis Supply Chain Worldwide survey, only 6% of supply chain professionals said they completely keep track of their tier-two suppliers, likely due to the high cost of investigation (Geodis, 2017). Further experimentation and adjustment are needed to adapt the technologies to the local context. Recent blockchain application for responsible business conduct in the mineral value chains in Burkina Faso, the Republic of the Congo (Congo), Mali and Niger suggests that the technology can only complement and not substitute in-person verification (OECD, 2019b; OECD 2018c).

Skills development, labour regulations and policies for financial inclusion are critical to preparing African workers for the digital transformation

Policy makers need to forge new alliances for skills development and improve school-to-work transitions for youth

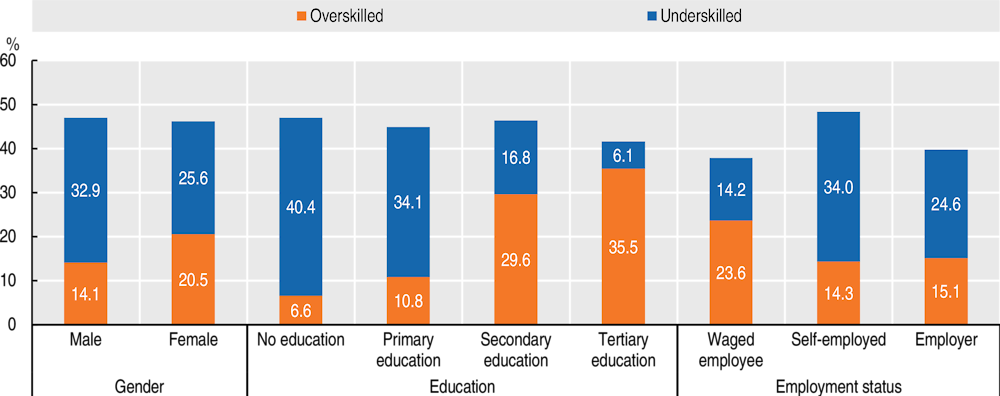

Most young Africans have skill sets that do not match their local labour markets. Between 2000 and 2020, Africa has made impressive progress in secondary and tertiary education completion rates among its youth (Chapter 1). However, both under-qualification and over-qualification of young workers in labour markets are pervasive across the continent (Morsy and Mukasa, 2019; AfDB, 2020). Surveys across 11 African countries highlight that nearly one in two youth feels his or her skills are inappropriate for the local labour markets, with 28% of youth feeling underqualified and 17% feeling overqualified. High educational attainment does not guarantee a better match: 35.5% of young graduates from the tertiary education feel overqualified for their jobs, while 6.1% feel underqualified (Figure 2.5). This skill mismatch creates dissatisfaction at work, affecting the overall productivity of the workforce and impeding firm dynamism, profitability and competitiveness (OECD, 2017b).

Figure 2.5. The proportion of youth with skills mismatches in ten African countries, by gender, educational attainment and employment status

Notes: All estimations account for sampling weights. The ten countries included are Benin, Congo, Egypt, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda and Zambia. The shares of respondents with appropriate skills (not shown) and of over-skilled and under-skilled respondents add up to 100%.

Source: Adapted from Morsy and Mukasa (2019) based on ILO’s School-to-work transition survey data for ten African countries across various years.

Africa’s education systems will need to equip youth with additional skills for the digital era. It is difficult to guess which specific skill sets will be the most demanded in local job markets within 10 or 15 years. Skills such as problem-solving and resilience will certainly be key to adapt to changing labour market conditions (World Bank, 2016). Youth will also need solid foundational skills, including good literacy, a basic knowledge of science, technology, engineering and mathematics, and digital skills. In Benin, Liberia, Malawi and Zambia, 60% of employers on average equally value technical skills (efficient use of materials, technology equipment and tools) and soft skills (teamwork and communication) as capital factors for their business development (Arias et al., 2019). Going up the value chain, jobs in activities such as marketing, logistics and quality control as well as in agri-business will require more advanced technical skills including data analytics or digital marketing (ACET, 2018; AUC/OECD, 2019).

School-to-work transition programmes need rethinking, in term of both focus and implementation. About 70% of Africa’s population are under 30 years old. A significant proportion of this young labour force is not in education, employment or training. They are outside the education and training systems, jobless or own-account workers in the informal sector. Low levels of Internet usage among these youth (see Figure 1.8 in Chapter 1) could limit the reach and effectiveness of approaches such as Massive Open Online Courses or on-job training within enterprises.

Policies should focus more on developing a wider skill base for young people. In most African countries, the formal sector is too small relative to the size of the youth cohorts entering the job market. For example, in Nigeria, the African country with the largest population, the local economy created an estimated 1.6 million formal sector jobs between 2013 and 2016. This compares to about 9 million youth turning 18 in Nigeria over the same period (Mastercard Foundation/Laterite, 2019). With such a job shortage in the formal economy, policies should focus more on developing a wider skill base for young people. The gender gap in digital skills is particularly worrying (E-skills4girls, 2020). Box 2.4 provides examples of gender-sensitive policies supporting skills development across the continent.

Tech hubs, incubators and tech companies can be of great relevance in preparing Africa’s youth for the transition to work. They can help design more effective training methods and new channels for lifelong learning and strengthen informal training institutions. A number of global tech companies are now carrying out initiatives around entrepreneurship and the development of digital skills for young Africans. Boot camps and joint incubation programmes with local tech hubs are part of this vibrant ecosystem. Academic programmes are creating new alliances with these actors.

In 2019, Microsoft launched its Africa Development Centre in Nairobi. The company expects to invest over USD 100 million in infrastructure and employment of qualified local engineers over the first five years of operation. It is also engaging in a number of training initiatives on the continent.

In May 2018, Facebook launched NG_HUB in Lagos in partnership with the Co-creation Hub to provide 50 000 young Nigerians with skills for own-business development and to nurture a strong mutual learning community of entrepreneurs (Oludimu, 2018). Beyond Lagos, the company has partnered with seven other tech hubs across the country (Jackson, 2018). #SheMeansBusiness (launched in March 2018) is another entrepreneurship training programme. It helps Nigerian women start and grow their own businesses.

In partnership with Facebook and Google, the African Institute for Mathematical Sciences (AIMS) created a new master’s degree programme, “African Masters in Machine Intelligence”, in 2018. AIMS is a pan-African network of centres of excellence in the areas of science, technology, engineering and mathematics.

Box 2.4. Examples of gender-sensitive policies supporting skills development in Africa

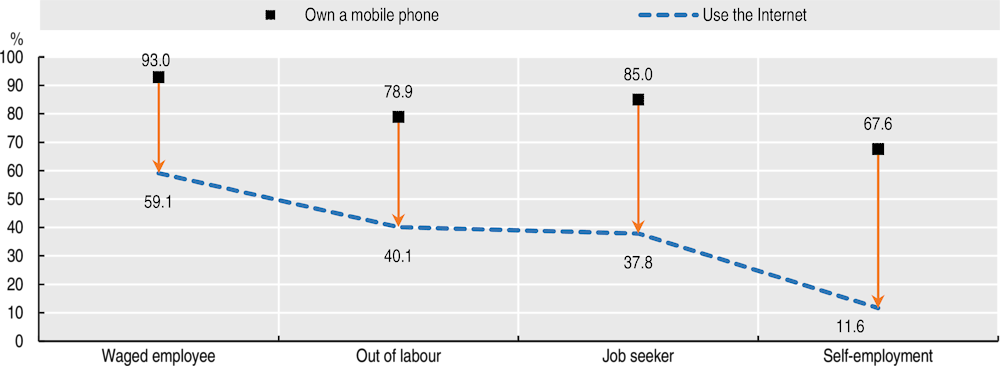

Africa has the widest digital gender gap (25%). Among Africa’s young women, aged 15-29, the self-employed lag far behind others in terms of Internet usage (Figure 2.6).

Figure 2.6. Mobile phone and Internet usage among Africa’s young women, aged 15-29, by employment status

Benin, Ghana and Rwanda focus their Universal Service and Access Funds (USAFs) on skill acquisition programmes for women entrepreneurs. The USAFs offer a promising path for implementing policies to reduce digital gender gaps in Africa (Thakur and Potter, 2018):

The Rwanda Universal Access Fund supports the Ms. Geek Africa programme − a competition run by Girls in ICT. Rwanda aims to encourage African girls, aged 13-21, to participate in the fields of science, technology, engineering and mathematics. Winners receive prizes in cash and equipment as well as training and mentorship to further develop their innovations, which seek to address some of Africa’s pressing challenges.

Ghana’s Investment Fund for Electronic Communications (GIFEC) has invested in the Digital for Inclusion programme, which comprises, among other things, mobile financial services via a digital payment platform. The programme has reserved 60% of the local sales agent positions for women.

In Benin, l’Agence Béninoise du Service Universel des Communications Électronique et de la Poste has supported the OWODARA project. This project developed a mobile phone-based system to provide prices of local agricultural goods (e.g. corn, millet, soybeans, peanuts) for the benefit of rural women entrepreneurs.

Other interesting initiatives focus on technical and vocational education and training for women. This is the case for Women and Digital Skills (Ghana), W.TEC (Nigeria) and WeCode (Rwanda). The regional chapters in this report provide further details on these initiatives.

Source: Authors’ compilation.

The emergence of iWorkers calls for specific policies

With the expansion of e-platforms, a new category of own-account workers is on the rise on the continent: the iWorkers. Their work is entirely fuelled by the use of digital platforms and applications (such as Uber, Delivroo, Upwork, online click-work), through which prices and payments arrangements are set (OECD, 2016; Stanford, 2017). They remain self-employed but depend almost entirely on digital platforms to connect to their clients. In Africa’s cities, iWorkers are flourishing in jobs such as driving taxis, delivering food by motorcycle (Lakemann and Lay, 2019) and designing websites. Mastercard Foundation (2019) estimates that iWorkers could make up more than 10% of Africa’s total labour force by 2030.

While these “new forms” of self-employment provide opportunities to reach a wider customer base and pay lower operating costs, job quality is a concern. Many iWorkers face precarious working conditions (OECD, 2016; Graham and Woodcock, 2018). An Eurofound/ILO (2019) survey conducted in 75 countries between 2015 and 2017 found that: i) compensation is often lower than minimum wage in the respective countries, ii) incomes are often unpredictable, and iii) workers do not benefit from standard labour conditions as in a formal employment relationship.

Policy makers should start setting solid regulatory schemes and social protection for iWorkers. A number of African countries have recently assessed the working conditions for this category of own-account workers. In 2017, Egypt became the first African country to issue a national e-commerce strategy. In 2018, Liberia conducted a country-level assessment of e-commerce platforms. Policies should also support collective action to help better regulate platform work. For example, in Kenya, a group of online workers came together to set up an association in 2019, the first experience of its kind in the country (Melia, 2020).

Additionally, the global nature of online labour platforms calls also for an international approach to domestic actions. These platforms often have headquarters outside of Africa and do not fall into the jurisdiction of African governments. Unilateral tightening of regulation may put African workers at a disadvantage with workers elsewhere and potentially eliminating this livelihood option. Co-operation is key:

Setting international standards for responsible business conduct for lead platform companies can help tackle practices such as “uncontestable non-payment” (Berg et al., 2019).

Promoting certification, such as Fairwork, on employment conditions for platforms can also help hold these platforms accountable (Graham and Woodcock, 2018).

African governments can help increase the availability and adoption of fintech solutions for the informal economy

Financial technologies are key to boost financial inclusion among actors in the informal economy. For example, in Tanzania, the deployment of a mobile learning and interactive SMS system on financial literacy content, Arifu (integrated into M-Pawa, a mobile savings and loan product) significantly improved saving and borrowing behaviours among smallholder farmers. Arifu users took out larger loans (TZH 1 017/USD 0.44), repaid them quicker (by 5.46 days) and had larger first payments (TZH 1 730/USD 0.76 more) (Dyer, Mazer and Ravichandar, 2017). Similarly, the Ugandan mobile savings and loan product, MoKash, tackled illiteracy in rural areas by providing a didactic platform with pictorials instead of text, as well as on-the-ground help to assist customers with registering and performing initial transactions.

The spread of fintech − technology-enabled innovation in financial services − offers new ways of doing business. For example, the convergence of social media, mobile e-commerce and digital payments could disrupt the retail sector rapidly. In eight African countries,2 90% of sales of consumer goods go through informal retail distribution channels (PwC, 2016). Small retailers around the world consistently identify the same sets of issues where digital solutions could add real value: working capital financing, payment solutions, customer relationships, inventory managing and business intelligence (e.g. forecasting and business statics) (CGAP, 2019). A recent policy review (OECD, 2020a) shows that fintech is driving innovative funding mechanisms for smaller enterprises, such as recoverable grants, pay-for-success convertible notes and blockchain-based financing solutions (OECD, 2019c; CFF, 2018).

Fintech can help informal firms to formalise by allowing them to progressively adopt formal tools and processes. Currently, 50% of all own-account workers in Africa’s informal economy have a smartphone (ILO, 2018). Mobile money services are often the first formal financial channel used by informal actors (GSMA, 2019b; Klapper, Miller and Hess, 2019). Some informal firms already utilise digital applications and free social media tools to promote their products and services. Empirical evidence shows that adopting mobile financial services reduces the size of the informal sector in developing countries by 2.4 to 4.3 percentage points of gross domestic product (GDP) (Jacolin et al., 2019).

African policy makers can capitalise on regulatory reforms in fintech to expand the availability of fintech innovations.Box 2.5 highlights a number of regulatory initiatives in Africa. In 2019, Rwanda was the world’s top country in the GSMA Mobile Money Regulatory Index, which scores 90 countries based on the extent to which their regulatory framework enables widespread mobile money adoption (GSMA, 2019c). Five other African countries were classified in the top 10 (Malawi, Lesotho, Liberia, Tanzania and Burundi) and another five in the top 20 (Ghana, Angola, Guinea, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Kenya).

Box 2.5. Examples of regulatory sandboxes in African countries

“A regulatory sandbox refers to a limited form of regulatory waiver or flexibility for firms, enabling them to test new business models with reduced regulatory requirements. Sandboxes often include mechanisms intended to ensure overarching regulatory objectives, including consumer protection. Regulatory sandboxes are typically organised and administered on a case-by-case basis by the relevant regulatory authorities” (OECD, 2019d; Attrey et al., 2020). To meet their potential, regulatory sandboxes need to i) have a clear thematic focus and policy objectives), and ii) adopt a transparent and standardised selection process.

Table 2.1. Operational regulatory sandboxes in Africa

|

Country |

Creation |

Examples of products tested |

|---|---|---|

|

Mauritius |

2016 |

• Blockchain and cryptocurrency (Be Mobile, FusionX, PIRL, SALT Technology Ltd, XenTechnologies Ltd) • Credit and capital solutions for individuals and SMEs (Finclub) • Crowdfunding (Olive Crowd, FundKiss) • Identity management system (Selfkey) |

|

Sierra Leone |

2018 |

• Mobile payment aggregator (Noory, MyPay) • Saving facility for farmers (icommit) • Mobile educational application, financial literacy content (InvestED) |

|

Mozambique |

2018 |

• Online payment aggregator system (Quick-e-Pay, PagaLu) • Digital banking solution (Zoona and Socremo) • Remittances facility (Mukuru) |

|

Kenya |

2019 |

• Crowdfunding platform (Pezesha Africa Limited) • Cloud-based data analytics platform (Innova Limited ) |

In certain cases, policy makers may encourage the adoption of digital financial services by informal actors. For example, in 2014, the Government of Uruguay created tax incentives to promote the use of digital payments by firms and consumers; in the following three years, formal financial transactions increased sevenfold (Klapper, Miller and Hess, 2019). Similarly, in the framework of the Rwanda National Payment System (RNPS) Strategy 2018-2024, the National Bank of Rwanda and the Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning now actively encourage network operators and payment service providers to propose digital payment solutions to merchants (NBR, 2017). Other initiatives that provide digital legal identity to citizens such as Digital ID Blueprint for Africa are critical to enhance the functioning and trustworthiness of digital financial services.

Interoperability is key to sustain the diffusion of fintech and mobile money services, notably to accelerate the creation of Africa’s common digital market. Interoperability is the ability of different IT systems to access, exchange and use information seamlessly in real time, enabling all participants to operate across all systems. So far, cross-network transactions do not take place in real time, and their unit cost is high (Ndung’u, 2019). Initiatives for regional interoperability are now taking root across the continent. For example:

In July 2018, the East African Securities Regulatory Authorities agreed to employ regulatory sandboxes to encourage innovation among capital market practitioners who operate regionally (Wechsler, Perlman and Gurung, 2018).

In 2018, Orange and MTN, two of the continent’s largest operators, created Mowali, a digital payment infrastructure connecting mobile money services within one inclusive network in 22 African countries.

Regional Economic Communities such as the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU) and the Southern African Development Community (SADC) are also developing projects to streamline payments in their regions and bring region-wide interoperability. These initiatives are particularly important in the context of the AfCFTA implementation.

Policies for digitalisation can empower Africa’s dynamic enterprises to compete and innovate

Chapter 1 highlighted that two promising groups of entrepreneurs can benefit the most from using digitalisation to scale up and create new jobs. A first group is mostly dominated by early-stage start-ups and high growth SMEs bringing new technologies and business models to disrupt or create new markets. A second group is dominated by start-ups and SMEs that deploy existing products or proven business models as they seek to grow through specialisation in niche markets, market extension or step-by-step innovations. Implementing policies that empower these dynamic entrepreneurs to compete, grow and create more jobs in the digital era is critical.

Trade facilitation and competition measures are critical to ensure African firms can participate in digitally-enabled trade

Innovative entrepreneurs need global business partners and a regional mindset to grow. Connecting new African entrepreneurs with existing worldwide ecosystems or clusters can provide them with access to funding, markets, talent and support systems. This can enhance their innovation capabilities and positively affect their confidence, competitiveness and growth prospects (Accenture, 2019). In South-East Asia, many successful start-ups, such as the e-commerce giant Lazada and the transportation and logistics app Grab, were born with a regional mindset that helped them grow early and fast (Forbes, 2019).

Digital connectivity can enable Africa’s entrepreneurs to enter new niches. To be reachable online, SMEs can opt for developing their own website or for using social media or specialised trade platforms (Amazon, Alibaba, Jumia, etc.). These digital tools enable payment arrangements and better communication tools, co-ordination and tracking systems along the value chain while increasing visibility to potential customers and business partners. For example, a number of small tourism companies in East Africa have successfully served new niche activities within wildlife tourism and eco-tourism and for tourists from emerging markets (Foster et al., 2017). Results from an econometric analysis of 27 000 manufacturing SMEs in 116 developing countries (including 31 African countries)3 confirm that SMEs which adopt digital technologies are more likely to engage in international trade. Having a website is positively associated with a 4.6 percentage point increase in the share of imports among firm inputs and a 5.5 percentage point increase in the share of direct exports in firms’ sales.

With the appropriate digital tools and skill sets, entrepreneurs can produce digitally delivered services and avoid weak transport and logistics infrastructure. Since 2015, electronic transmission has become the dominant mode used in Africa’s trade in professional services (such as finance, insurance ICT and technical support). It accounted for USD 18.8 billion, or 57% of Africa’s export in professional services in 2017, up from USD 8.0 million in 2005. The gaming industry is another promising area. Forecasts say the gaming industry will surpass USD 200 billion of revenue globally by 2023, up from an estimated USD 145.7 billion in 2019 (Newzoo, 2019). In 2016, Kiro’o Games released Aurion, an African-themed video game, to the global market via the Steam platform. This small company of 20 employees, based in Cameroon, raised USD 57 000 in April 2016 to develop games from 1 310 backers through Kickstarter, an online crowdfunding platform (Kickstarter, 2019). It joins a recent wave of African video game makers from Egypt, Nigeria and South Africa that focus on producing unique, local narratives for the continental market (Dahir, 2017).

Trade facilitation measures remain critical in the era of digital trade

The high costs of moving physical goods, combined with slow and unreliable custom processes, hamper Africa’s intra-regional trade and SMEs’ survival rates on export markets. Jumia’s recent exit from Cameroon, Rwanda and Tanzania highlights this problem (Financial Times, 2019). Only 18% of new exporters in Africa survive beyond three years (AUC/OECD, 2019). In addition, only 11.2% of African SMEs have an internationally recognised quality certification.

Policies should aim to improve regulation and remove bottlenecks along the following segments of cross-border e-commerce: the online creation of businesses, international e-payments, cross-border deliveries, aftersale services, and standards and certification (WTO, 2018).

Cross-border recognition of e-documents is essential. Streamlining and interconnecting customs administrations through one-stop border posts (OSBPs) could simplify administrative procedures for regional trade. For example, the East-African Community (EAC) has reduced transit times and costs by fully operationalising the OSBPs in all its member countries in November 2018 (EAC Secretariat, 2018).

Regulatory harmonisation needs to accelerate in certain areas. These include licences for e-commerce, online tax registration and declaration for non-resident firms, electronic authentication and payment, online dispute resolution, and intellectual property rights. SMEs may not be able to comply with many national legislations on data and digital trade (OECD, 2004; Ferencz, 2019; Koski and Valmari, 2020). Regional Economic Communities are well-placed to:

Co-ordinate the establishment of coherent data protection frameworks that are compatible with international standards

Promote communication and support initiatives on compliance mechanisms.

Regulators and competition authorities need to safeguard against anti-competitive behaviours in the digital marketplace

The digital marketplace can enhance SMEs’ access to markets by lowering installation costs, improving co-ordination with distant partners and enhancing access to information. Global online platforms such as Alibaba, Amazon, eBay and TripAdvisor and regional ones such as Jumia, Takealot and Kilimall increase SMEs’ visibility while requiring little initial investment. E-commerce in Africa remains limited due to a low level of trust in online shopping and difficulties in shipping and paying across borders (López-González and Jouanjean, 2017). Amazon currently accepts sellers from only 23 African countries.4 Google Play Store accepts developer registration from 37 African countries and merchant registration from 27 African countries.5 Thus, developers and merchants from the other African countries cannot sell goods or applications on these platforms.

Governments must ensure competition in the digital economy so that many more African firms can join e-commerce platforms. Monopoly control over data and differences in scale can affect the distribution of gains between firms operating on e-platforms. Calligaris, Criscuolo and Marcolin (2018) document firm-level mark-ups across 26 OECD countries to show that, in digital sectors, a few “superstar” firms enjoy disproportionate market power and account for a higher share of the profits. Firms operating in “digital intensive” service sectors enjoy a 2-3% higher mark-up than firms operating in less digital intensive sectors. The gain is substantially higher (up to 43%) if a firm is operating in one of the top digital sectors. This differential widened during the period of study, 2001-14, and resulted mostly from the steep increase in mark-ups for the top firms.

Regulators and competition authorities need to ensure that competition policies and investigation tools are up to date and agile enough for data markets regulation. The digital transformation may introduce new dimensions of competition in markets and new ways to achieve anticompetitive outcomes, such as the use of algorithms to collude or the anticompetitive acquisition of start-ups by incumbent players (OECD, 2020b; OECD 2018d). Competition laws need, for instance, to limit exclusivity requirements and preserve “multihoming” where sellers can work with multiple platforms.6 In addition, dominant e-commerce platforms can substantially favour their own brands through recommendation systems and unmatched advantages in market data. To address these two issues, in 2018, Indian regulators banned foreign e-commerce platforms from imposing exclusivity requirements and selling products from companies in which the platforms had equity. The OECD Competition Assessment Toolkit can also assist governments in eliminating barriers to competition in a changing environment by providing a method for identifying unnecessary restraints on market activities and developing alternative, less restrictive measure. In 2019, Tunisia applied this methodology to review the competitiveness and efficiency of its wholesale and retail trade sectors, as well as road and maritime freight transports (OECD, 2019e).

Governments can actively promote open standards and fair access for businesses to data and to consumers on platforms while balancing legitimate concerns about personal privacy rights. Consumer data can increasingly serve as a competitive asset when providing products at a price of zero, or when developing personalised prices. Users’ data and content will also need to be portable across platforms so that data transfer does not bar users from switching to a superior platform. For example, regulators could make it mandatory for e-platforms to adopt open policies for their application programme interfaces (API). An API contains the set of routines, protocols, and tools that specify how different software should interact. Bilateral and regional co-operation may be needed across borders to ensure that common standards are applied and that information is available to regulators (OECD, 2020b).

Dedicated initiatives can support intellectual property registration for start-ups

Too few African entrepreneurs file for intellectual property (IP) protection. In 2018, only 17 000 patent applications, or 0.5% of the worldwide total (Table 2.2) were registered in Africa, of which a large majority (81.6%) emanated from non-residents (WIPO, 2019).

Table 2.2. Numbers of applications for patents, industrial designs and trademarks by world region, 2018 (percentage)

|

|

Patent |

Industrial design |

Trademark |

Total (all types of IP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Africa |

0.5 |

1.3 |

1.7 |

1.5 |

|

Asia |

66.8 |

69.7 |

70.0 |

69.5 |

|

Europe |

10.9 |

23.0 |

15.8 |

15.4 |

|

Latin America and the Caribbean |

1.7 |

1.2 |

5.3 |

4.3 |

|

North America |

19.0 |

4.1 |

5.8 |

8.0 |

|

Oceania |

1.1 |

0.7 |

1.4 |

1.3 |

|

World (total) |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

Source: Authors’ calculations based on WIPO (2020), WIPO Statistics Database, October 2019.

In most cases, the IP registration process remains costly, slow and cumbersome to navigate for local start-ups and inventors. For example, the cost to register and maintain a 30-page patent for the ten first years is about USD 37 000 in the ARIPO (African Regional Intellectual Property Organization) system and USD 30 000 in the OAPI (Organisation Africaine de la Propriété Intellectuelle) system (see Table 2.3). This is about 6 to 7 times higher than in South Africa (USD 5 216) or in Malaysia (USD 4 330) and more than 10 times higher than in the United Kingdom (USD 2 500). Relative to the country’s income level, Kenya’s patent registration fees are 13.3 times its GDP per capita, while for Senegal and Ethiopia the ratio is 10.2 and 7.9, respectively (Brookings, 2020). Consequently, most of Africa’s young innovators find themselves obliged to market their products without IP protection (ITC, 2016).

Table 2.3. Estimated patenting costs in ARIPO and OAPI systems and in South Africa (in USD)

|

Stage of patent process |

Costs – ARIPO* (USD) |

Costs – OAPI** (USD) |

Costs − South Africa (USD) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Filing |

1 797 |

5 150 |

1 589 |

|

Examination |

1 165 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Prosecution |

1 060 |

2 879 |

120 |

|

Grant |

1 830 |

1 62 |

180 |

|

Cumulative annuities |

31 990 |

21 941 |

3 327 |

|

Total |

37 842 |

30 132 |

5 216 |

Note: *ARIPO: African Regional Intellectual Property Organization. **OAPI : Organisation Africaine de la Propriété Intellectuelle. n/a = not applicable.

Source: De Andrade and Viswanath (2017), The Costs of Patenting in Africa: A Tale of Three Intellectual Property Systems.

Policies need to support entrepreneurs register and defend their copyrights, brands, patents, industrial designs and trademarks. Making it easier to use IP (in particular patents and design rights in specific business activities) will help some young firms to obtain financing, drive job growth and spur innovation (OECD, 2015). In most African countries, three areas require particular attention:

Streamlining application procedures. An example of best practice comes from Kenya. In 2015, the Kenya Copyright Board collaborated with Microsoft 4Afrika to develop more user-friendly interfaces for registration. Innovators in Kenya are now able to register their IP and obtain copyrights through an automated online registration system. They can also receive a patent, trademark or certification mark from the Kenya Industrial Property Institute (ITC, 2016). The system resulted in a 100% increase in applications in the first four months and expanded to serve the Common Market for East and Southern Africa (Microsoft, 2016).

Reducing examination times and lowering the costs of IP registration for local entrepreneurs. Since 2016 in India, for example, the government has set up a fast-track scheme to enable start-ups to register patents and trademarks for their inventions. Selected facilitators provide start-ups with high-quality services throughout the filing application process, including fast examination of patents at lower fees. The government bears all facilitator fees, and the start-ups enjoy an 80% reduction in the cost of filing patents.

Strengthening the IP rights enforcement mechanisms and simplifying the procedures for their owners to receive royalties. In Nigeria, for example, about 70% of surveyed stakeholders considered that weak enforcement of the country’s intellectual property regime caused adverse effects on the Nollywood movie industry (Oguamanam, 2018). SMEs, online content producers and stakeholders in the creative economy often lack the resources and knowledge to defend their IP rights. In 2013, the Nigeria Copyright Commission disclosed that the country was losing over USD 1 billion to piracy annually (ICC/BASCAP, 2015).

Policy makers can support funding mechanisms for start-up ecosystems

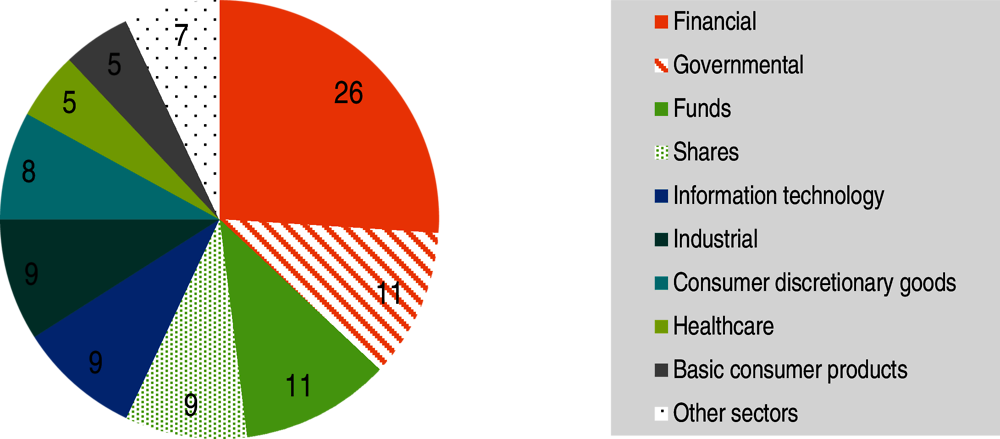

Venture capital (VC) funding for Africa’s start-ups grew sevenfold between 2015 and 2019. Tech start-ups raised a total of USD 2.02 billion in VC funding in 2019, a 74% increase compared to USD 1.16 billion in 2018 (Partech, 2020). Most (54.5%) VC funding went to fintech and the financial sector.

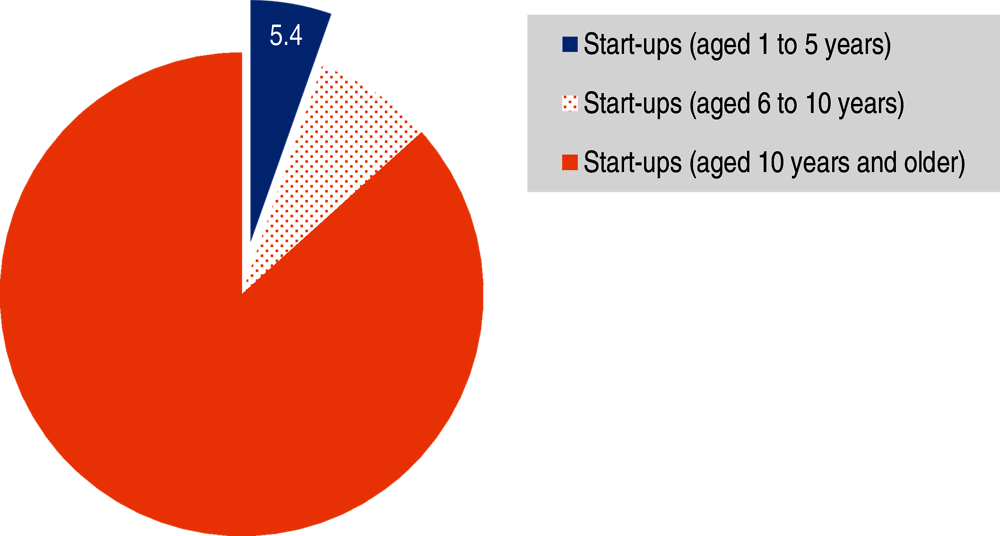

The funding ecosystem for entrepreneurs remains fragile and inadequate. Just four countries (Egypt, Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa) have attracted the lion’s share (85%) of these VC funds. In a sample of 7 000 African start-ups, less than 10% have been able to raise funds from investors and venture capital. Only 5.4% of the total funds raised went to start-ups younger than five-years-old (Figure 2.7). Start-ups founded by women in particular lack financing (see Box 2.6). Financing for Africa’s start-ups and SMEs in general remains far below need. The International Finance Corporation (IFC, 2017) estimated that the 44 million micro, small and medium-sized enterprises in sub-Saharan Africa needed USD 404 billion of finance in 2017, creating a financing gap of approximately USD 331 billion, or 16% of the continent’s GDP.

Figure 2.7. Distribution of funding for Africa’s start-ups, by age of the start-up (as a percentage of total funds raised)

Box 2.6. Entrepreneurship and financing challenges for African women

Dynamic female entrepreneurs are prevalent in Africa, with some emerging in digital activities. Out of 58 countries around the globe evaluated by the Mastercard Women Index 2019, Botswana, Ghana and Uganda recorded the highest percentages of women-owned businesses (Mastercard, 2019). Moreover, a significant proportion of women are opportunity-driven entrepreneurs in those countries: 54% in Uganda, 50% in Botswana and 44% in Ghana.

Young African women are the most entrepreneurial worldwide. Globally, the highest total entrepreneurial activity (TEA) rates for women are found in sub-Saharan Africa (21.8% to 25.0%), followed by Latin America and the Caribbean (17.3%), while the global average rate is 10.2% (Elam et al., 2019). TEA represents the percentage of the adult working-age population (aged 18-64) who are either nascent or new entrepreneurs. In Nigeria, nearly four in every ten working-age women are engaged in early-stage entrepreneurial activity (40.7%).

Female-led digital start-ups are taking a stronger hold across the continent. In Nigeria, for example, the personal savings and investment platform PiggyVest, launched in 2016, counts more than 350 000 users saving a total of over USD 2.7 million across the country every month. Uganda’s JusticeBot is an online platform that helps the public access justice by providing free legal information and connecting people to legal service providers, through an always-on chatbot on Facebook’s Messenger. Botswana’s Tempest Gold is a property digital platform that facilitates both landlord-tenant relations and property listings management.

However, female-led start-ups, or those with at least one female founder, receive a much smaller share of the flow of global venture capital funding. In 2018, start-ups in emerging markets with a woman on their founding team received 11% of seed-financing and 5% of later-stage venture capital (IFC/We-Fi/Village Capital, 2020). In Africa, women-led start-ups only received 2% of the venture capital funding in 2019.

Adapting risk assessment methods, directly funding acceleration programmes, public procurements, and tapping sovereign wealth fund can improve funding for local start-ups

Local banking and most local VC investors rely on the cash flow-based valuation system, which works well for older asset-based companies but often undervalues young enterprises with rapid growth potential. Consequently, many early-stage entrepreneurs face obstacles in obtaining loans from local banking systems, in spite of having promising business ideas. For example, among the 93 fast-growing tech firms located in the Yabacon Valley (Lagos) surveyed by Ramachandran et al. (2019), 60% reported access to finance (and in particular local investments and VC) as a major or severe obstacle.

It is urgent to adjust risk assessment and valuation methods for entrepreneurs. Traditional risk assessment and valuation approaches may fail to grasp the full potential of local entrepreneurs. Evaluating start-ups requires a greater emphasis on their business models, including suitability for the local context, scope for business expansion on the targeted market segments, team composition, motivation and education profiles. So far, few experienced investors have started considering these alternative valuation methods for start-ups (Wulff, 2020). African governments can use public guarantee mechanisms to encourage business angels and private venture capitals to invest more in entrepreneurs. Making data publicly available on entrepreneurial activities can help identify high-potential new businesses, provided it respects international standards and laws on data privacy and data protection. Capacity building agencies, such as incubators, foundations, training institutes and mentoring programmes, can help entrepreneurs prepare their projects better in order to attract more investment.

Governments can carry out direct funding and acceleration programmes for start-ups. Start-up accelerators aim to help companies scale up by connecting them to investors, business partners and clients. In some cases, they also provide some start-up capital, generally in exchange for an equity participation. The case of Egypt offers an illustrative example (see Annex 1.A2 in Chapter 1).

Prudent public procurements can boost demand for start-ups. In 2012, the Federal Government of Nigeria decided to test an innovative mobile phone-based input subsidy programme that provides fertiliser and improved seed subsidies through electronic vouchers. A four-year contract was awarded to Cellulant, a local fintech start-up, to create a mobile wallet solution (e-wallet) connecting farmers with input-suppliers and financial institutions. This programme has become one of the largest agritech solutions in Africa using mobile wallet technology (Cellulant, 2019). Through this initiative for agricultural inputs, called the growth enhancement support scheme, the Nigerian government distributed USD 7.3 million in subsidies to farmers. Since 2012, the e-wallet technology has delivered services to about 12 million farmers in Nigeria (Cellulant, 2020). Following a satisfactory evaluation in 2016 (Wossen et al., 2017; Uduji et al., 2018), the contract was subsequently renewed for another four years, until end-2020.

Countries with a sovereign wealth fund (SWF) should consider setting up small venture capital funds within their investment structures to support the development of start-up and SME ecosystems. Angola (see Box 2.7), Gabon and Senegal are paving the way. For instance, Angola’s SWF (FSDEA) and Gabon’s Okoume Capital devoted part of their budget to supporting entrepreneurial start-ups and innovation ecosystems. Senegal’s FONSIS (Fonds d’Investissement Stratégiques) invested in Teranga Capital, which in turn provides financing for SMEs (OECD, 2020c). Given the flourishing number of incubators in Africa, sovereign and strategic investment funds could even initiate a partnership with them to help them succeed. In recent years, Africa has been one of the most dynamic regions in the world in terms of SWF creation. From 2009 to 2015, assets under African SWF management increased by 39%, from USD 114 billion to USD 159 billion (Quantum Global, 2017). In 2020, there are 18 SWF currently operating in 14 countries on the continent (SWF Institute, 2020). Six of these African SWFs have assets over USD 1 billion.

Box 2.7. Angola’s move towards strategic use of its sovereign wealth fund for financing start-ups

Angola’s sovereign wealth fund FSDEA (Fundo Soberano de Angola) targets economic sectors which have a higher return potential and which are central for economic diversification, productivity and structural transformation. It has dedicated investment funds for six strategic sectors − infrastructure, hotels, timber, mining, agriculture and healthcare − and a Mezzanine Investment Fund. The latter targets other emerging opportunities, including start-ups and venture financing. It has a portfolio of USD 250 million for entrepreneurship financing.

The FSDEA’s investment portfolio is currently broadly diversified in terms of assets (Figure 2.8) and geographical areas. In accordance with the investment policy enacted by the Executive, two-thirds of the investment portfolio are allocated to private equity activities in emerging and border markets to generate high long-term returns (FSDEA, 2020). However, private equity activity in infrastructure, agriculture, forestry, mining and health in sub-Saharan Africa is emphasised in order to support the socio-economic development of the region. The FSDEA has a much greater investment focus on regional development in sub-Saharan Africa than other sovereign wealth funds (Markowitz, 2020).

Figure 2.8. Sectoral distribution of Angola’s sovereign wealth fund net investment portfolio, as of July 2020

Source: Authors’ compilation based on FSDEA (2020), “Investment strategy”; Markowitz (2020), “Sovereign wealth funds in Africa: Taking stock and looking forward”; and Quantum Global (2017), “Sovereign wealth funds as a driver of African development”.

References

A4AI, (2018), “Uganda: New social media tax will push basic connectivity further out of reach for millions”, Alliance for Affordable Internet, https://a4ai.org/uganda-social-media-tax/ (accessed 21 July 2020).

AB InBev (2019), “BanQu raises series A extension round from ZX Ventures/AB InBev to continue its geographic expansion and product development in the Supply Chain Transparency & Traceability Space for global brands”, Anheuser-Busch InBev, https://www.ab-inbev.com/news-media/innovation/banqu.html (accessed 27 July 2020).

Accenture (2019), Tech Startups Will Support Africa’s Growth, www.accenture.com/_acnmedia/pdf-105/accenture-forbes-advertorial-tech-startups.pdf (accessed 17 July 2020).

ACET (2018), “The future of work in Africa: Implications for secondary education and TVET systems”, Background Paper December 2018, African Center for Economic Transformation, http://acetforafrica.org/acet/wp-content/uploads/publications/2019/04/FOW-SecEdu-Study-MCF-Dec-2018-Final_Download-1.pdf.

AfDB (2020), African Economic Outlook 2020: Developing Africa’s Workforce for the Future, African Development Bank, Abidjan, https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/african-economic-outlook-2020.

Afrobarometer (2019), Afrobarometer (database), https://afrobarometer.org/fr (accessed 21 July 2020).

After Access (2017), “Using evidence from the Global South to reshape our digital future” (presentation), Internet Governance Forum 2017, Geneva, www.afteraccess.net/reports/using-evidence-from-the-global-south-to-reshape-our-digital-future (accessed 5 March 2020).

Annan, K., G. Conway and S. Dryden (2015), “African farmers in the digital age: How digital solutions can enable rural development”, Foreign Affairs, November/December (Special Issue), https://www.kofiannanfoundation.org/web/app/uploads/2016/01/African-Farmers-in-the-Digital-Age-1.pdf.

Arias, O. et al. (2019), The Skills Balancing Act in Sub-Saharan Africa: Investing in Skills for Productivity, Inclusivity, and Adaptability, Agence Française de Développement and World Bank, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/31723.

Attrey, A., M. Lescher and C. Lomax (2020), “The role of regulatory sandboxes in promoting flexibility and innovation in the digital age”, Going digital policy note, No. 2, https://goingdigital.oecd.org/toolkitnotes/the-role-of-sandboxes-in-promoting-flexibility-and-innovation-in-the-digital-age.pdf

AUC/OECD (2019), Africa’s Development Dynamics 2019: Achieving Productive Transformation, OECD Publishing, Paris/African Union Commission, Addis Ababa, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c1cd7de0-en.

AUC/OECD (2018), Africa’s Development Dynamics 2018: Growth, Jobs and Inequalities, OECD Publishing, Paris/African Union Commission, Addis Ababa, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264302501-en.

AU-EU DETF (2019), New Africa-Europe Digital Economy Partnership: Accelerating the Achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals, African Union Commission-European Commission Digital Economy Task Force, https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/new-africa-europe-digital-economy-partnership-report-eu-au-digital-economy-task-force.

Berg, J. et al. (2019), “Working conditions on digital labour platforms: Opportunities, challenges, and the quest for decent work”, Vox EU, https://voxeu.org/article/working-conditions-digital-labour-platforms (accessed 20 July 2020).

Berryhill, J., T. Bourgery and A. Hanson (2018), “Blockchains unchained: Blockchain technology and its use in the public sector”, OECD Working Papers on Public Governance, No. 28, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/3c32c429-en.

Bright, J. (2019), “Kenya’s Twiga Foods eyes West Africa after $30M raise led by Goldman”, Techcrunch, https://techcrunch.com/2019/10/28/kenyas-twiga-foods-eyes-west-africa-after-30m-raise-led-by-goldman/2019/10/28/kenyas-twiga-foods-eyes-west-africa-after-30m-raise-led-by-goldman/ (accessed 27 July 2020).

Broeders, D. and J. Prenio (2018), “Innovative technology in financial supervision (suptech): The experience of early users”, FSI Insights on Policy Implementation, No. 9, Financial Stability Institute, www.bis.org/fsi/publ/insights9.pdf (accessed 17 July 2020).

Brookings (2020), Foresight Africa: Top Priorities for the Continent 2020-2030, Africa Growth Initiative, www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/ForesightAfrica2020_20200110.pdf (accessed 17 July 2020).

Byamugisha, F. F. (2013), Securing Africa’s Land for Shared Prosperity: A Program to Scale Up Reforms and Investments, World Bank, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/732661468191967924/Securing-Africas-land-for-shared-prosperity-a-program-to-scale-up-reforms-and-investments.

Calligaris, S., C. Criscuolo and L. Marcolin (2018), “Mark-ups in the digital era”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers, 2018/10, Paris, www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/4efe2d25-en.pdf?expires=1594992170&id=id&accname=ocid84004878&checksum=BB887B824D9EA33E76B6124ECE0F954E (accessed 17 July 2020).

Cellulant (2020), Agrikore Risk Review, Issue 1, https://cellulant.com/publications/pdfs/agrikore-risk-review-by-cellulant-issue-1-light.pdf (accessed 17 July 2020).

Cellulant (2019), “Agritech in Africa: How an e-wallet solution powered Nigerian government’s GES scheme”, https://cellulant.com/blog/agritech-in-africa-how-an-e-wallet-solution-powered-nigeria-governments-ges-scheme/ (accessed 17 July 2020).

CFF (2018), The Missing Middles: Segmenting Enterprises to Better Understand Their Financial Needs, The Collaborative for Frontier Finance, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/59d679428dd0414c16f59855/t/5bd00e22f9619a14c84d2a6c/1540361837186/Missing_Middles_CFF_Report.pdf.

CGAP (2019), “Digitizing merchant payments: Why and how”, Consultative Group to Assist the Poor, October 2019, https://www.cgap.org/research/publication/digitizing-merchant-payments-why-and-how (accessed 9 July, 2019)

CTA (2019), The Digitalisation of African Agriculture Report, 2018-2019, Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Co-operation, www.cta.int/en/digitalisation-agriculture-africa.

Dahir, A. L. (2017), “African video game makers are breaking into the global industry with their own stories”, Quartz Africa, https://qz.com/africa/974439/african-video-game-makers-are-breaking-into-the-global-industry-with-their-own-stories/ (accessed 17 July 2020).

Das Nair, R. and N. Landani (2020), “Making agricultural value chains more inclusive through technology and innovation”, WIDER Working Paper 38/2020, UNU-WIDER, Helsinki, https://doi.org/10.35188/UNU-WIDER/2020/795-8.

De Andrade, A. and V. Viswanath (2017), The Costs of Patenting in Africa: A Tale of Three Intellectual Property Systems, www.ipwatchdog.com/2017/08/04/costs-patenting-in-africa/id=86500/.

Deichmann, U., A. Goyal and D. Mishra (2016), “Will digital technologies transform agriculture in developing countries?”, Policy Research Working Paper, No. 7669, World Bank Group, Washington, DC, http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/481581468194054206/pdf/WPS7669.pdf.

Deininger, K. (2018), “For billions without formal land rights, the tech revolution offers new grounds for hope”, Land Portal, https://landportal.org/blog-post/2018/03/billions-without-formal-land-rights-tech-revolution-offers-new-grounds-hope (accessed 24 July 2020).

Dyer, J., R. Mazer and N. Ravichandar (2017), “Increasing digital savings and borrowing activity with interactive SMS: Evidence from an experiment with the M-PAWA savings and loan mobile money product in Tanzania”, CGAP Background Documents, https://www.findevgateway.org/paper/2017/05/increasing-digital-savings-and-borrowing-activity-interactive-sms (accessed 20 May 2020).

EAC Secretariat (2018), “EAC operationalizes 13 one stop border posts”, East African Community, www.eac.int/press-releases/142-customs/1276-eac-operationalizes-13-one-stop-border-posts (accessed 14 February 2019).

Elam, A. B. et al. (2019), GEM Women’s Entrepreneurship Report 2018/2019, Global Entrepreneurship Research Association, London, www.gemconsortium.org/report/gem-20182019-womens-entrepreneurship-report.

Eurofound/ILO (2019), Working Conditions in a Global Perspective, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg/International Labour Organization, Geneva, www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_696174.pdf.

Fall, M. and S. Coulibaly (2016), “Diversified urbanization: The case of Côte d’Ivoire”, Directions in Development: Countries and Regions, The World Bank Group, Washington, DC, https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-0808-1.

Fan, S. and C. Rue (2020), “The role of smallholder farms in a changing world”, in Gomez y Paloma, S., L. Riesgo and K. Louhichi (eds.), The Role of Smallholder Farms in Food and Nutrition Security, Springer, Cham, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-42148-9_2.

Ferencz, J. (2019), “The OECD Digital Services Trade Restrictiveness Index”, OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 221, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/16ed2d78-en.

Financial Times (2019), “Africa’s Amazon hopeful Jumia retreats from big expansion”, www.ft.com/content/a4f6ee1e-182b-11ea-9ee4-11f260415385 (accessed 17 July 2020).

Forbes (2019), “Scaling in Southeast Asia: Lessons from the region’s biggest startups”, Small Business, www.forbes.com/sites/jonathanmoed/2019/06/21/scaling-in-southeast-asia-lessons-from-the-regions-biggest-startups/#771904231cff (accessed 17 July 2020).

Foster, C. et al. (2017), “Digital control in value chains: Challenges of connectivity for East African firms”, Economic Geography, Vol. 94, No. 1/2018, Informa UK Limited, https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2017.1350104.

FSDEA (2020), “Investment strategy”, Fundo Soberano de Angola, https://fundosoberano.ao/en/investiments (accessed 20 July 2020).

GEODIS (2017), “GEODIS unveils its 2017 supply chain worldwide survey”, https://geodis.com/fr/en/newsroom/press-releases/geodis-unveils-its-2017-supply-chain-worldwide-survey (accessed 22 July 2020).

Gillwald, A. and O. Mothobi (2019), “After Access 2018: A demand-side view of mobile internet from 10 African countries”, Policy Paper Series No. 5 After Access: Paper No.7, Research ICT Africa, Cape Town, https://researchictafrica.net/2019_after-access_africa-comparative-report/ (accessed 2 March 2020).

Graham, M. and J. Woodcock (2018), “Towards a fairer platform economy: Introducing the Fairwork Foundation”, in Social Inequality and the Spectre of Social Justice, www.alternateroutes.ca/index.php/ar/article/view/22455/18249 (accessed 20 July 2020).

GSMA (2019a), Improving Financial Inclusion through Data for Smallholder Farmers in Kenya, GSM Association, London, www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/GSMA_AgriTech_Improving-financial-inclusion-through-data-for-smallholder-farmers-in-Kenya.pdf.