Alberto Ciolfi

National Agency for the Evaluation of Universities and Research Institutes (ANVUR), Italy

Morena Sabella

National Agency for the Evaluation of Universities and Research Institutes (ANVUR), Italy

Alberto Ciolfi

National Agency for the Evaluation of Universities and Research Institutes (ANVUR), Italy

Morena Sabella

National Agency for the Evaluation of Universities and Research Institutes (ANVUR), Italy

As discussed in this chapter, Italy was the first country outside the United States to implement the CLA+ assessment as part of its nation-wide TECO project and its decision to move towards a different assessment approach.

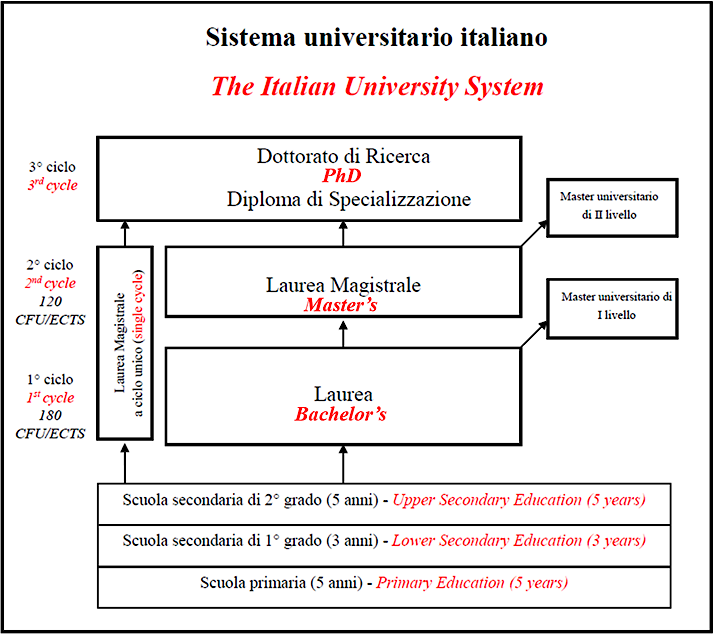

Since its inception in 1999, Italy has been part of the Bologna Process, which seeks to bring coherence to higher education systems across Europe. The European Higher Education Area (EHEA) was established to facilitate student and staff mobility, and to make European higher education more inclusive, accessible, attractive and competitive worldwide.

One of the outcomes of the process was the development of the Qualifications Framework for the European Higher Education Area (QF for the EHEA). All participating countries agreed to introduce a three-cycle higher education system consisting of bachelor's, master's and doctoral studies (PhDs).

Accordingly, the Italian Qualification Framework has been structured in three cycles: each cycle corresponds to a specific academic qualification (degree) that allows you to continue your studies, and participate in public calls to enter the labour market. All study programmes are structured in credits, called “credito formativo universitario” (CFU). This system is equivalent to the European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS). A CFU corresponds approximately to a 25-hour workload for the student, including time for individual study. The average amount of work done by a full-time student during an academic year is conventionally set at 60 CFU/ECTS.

Source: ANVUR

The Italian higher education system currently includes 97 universities: 61 public universities, 19 private universities, 11 private online universities (e-learning programmes only), and six special tertiary education schools, which only provide doctoral training. Moreover, the national system also includes higher education in Art, Music and Dance (AFAM), which currently totals 159 institutions that carry out teaching, artistic production and research in visual arts, music, dance, drama and design, and deliver university-level degrees. The AFAM sector is not included in the Italian experience of assessing students’ generic learning outcomes.

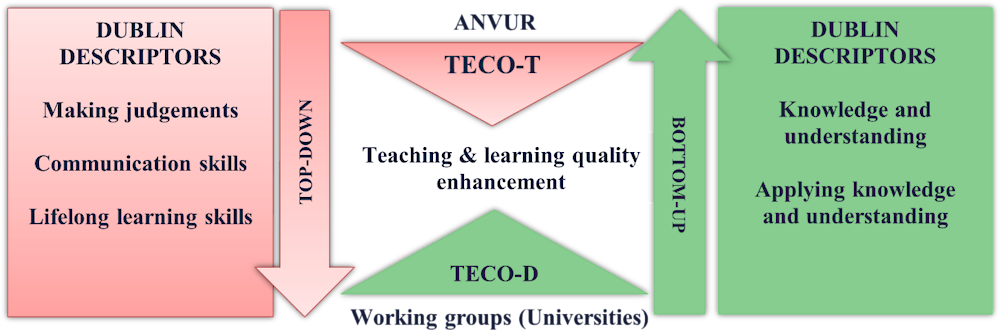

The learning outcomes common to all qualifications of the same cycle adhere to a set of general descriptors. They reflect the wide range of disciplines and profiles, and must be able to summarise the variety of features of each national higher education system. The Dublin Descriptors are general statements about the ordinary outcomes that are achieved by students after completing a curriculum of studies and obtaining a qualification. The descriptors are conceived to describe the overall nature of the qualification. Furthermore, they are not to be considered disciplines and they are not limited to specific academic or professional areas.

The Dublin Descriptors consist of: Knowledge and understanding; Applying knowledge and understanding; Making judgements; Communication skills; and Learning skills. The learning outcomes of the Italian first- and second-cycle degree courses are structured according to the Dublin Descriptors.

Notably, between 2012 and 2013, the National Agency for the Evaluation of Universities and Research Institutes (hereinafter referred to as ANVUR) carried out an experimental assessment of the generic learning outcomes shown by students graduating from Italian universities by means of the TECO (TEst sulle COmpetenze) test. This pilot test was designed taking as a reference point the OECD feasibility study called AHELO – Assessing Higher Education Learning Outcomes. It is consistent with the European Standards and Guidelines for Quality Assurance (ESG, 2015[1]) that promote student-centred learning, accompanied by the analysis of learning outcomes, across the European Higher Education Area (EHEA).

ANVUR is an Italian independent public body that oversees the national higher education system and whose primary objective is to enhance its overall quality. The evaluation tasks of the agency, which has been operating since 2012, span the full range of higher education institutions’ activities: teaching and learning; research; impact of social initiatives (“third mission”); and administrative performance. Both output and process evaluation methodologies are applied with broad use of informative tools developed by/in collaboration with ANVUR.

Different reasons impelled ANVUR to undertake this pilot test, beginning in 2013. Legislative Decree n. 19 of 27 January 2012 governing the system of Self-Assessment and Periodic Assessment and Accreditation in higher education (hereinafter referred to as AVA) introduced a system of the initial and periodic accreditation of universities and their study programmes; a periodic assessment of the quality, efficiency and outcomes of universities’ teaching activities; and the enhancement of the mechanisms underpinning the self-assessment of the quality and effectiveness of universities’ activities.

Within this framework, the TECO pilot test supplements the assessment process via indicators that allow self-evaluation of the quality of learning achieved by students during their studies. Specifically, TECO enables self-evaluation of generic competences students possess upon graduating from university. It does so by constructing indicators that estimate the skill levels of university students. These indicators also allow for the periodic evaluation and accreditation of universities and their study programmes.

It is also the case that principal stakeholders (employers, universities, students and their families, taxpayers, and the government) are interested in an ever-improving quality of education in Italian universities. At the beginning, the pilot TECO test aimed to measure cross-disciplinary competences: the critical thinking needed to solve a problem or make a decision; the ability to represent and communicate a given fact; and the ability to learn new knowledge related to areas not necessarily connected with the particularities of the scientific discipline being studied. These competences are not monitored, assessed or certified by universities because they are not the subject of specific teaching activities; rather, they are part of that intangible stock of knowledge and skills that all teachers should pass on to students simply by teaching their subject. These are detected through TECO-T, a test designed to evaluate transversal skills. Disciplinary skills acquired by students in various bachelor’s programmes are evaluated through TECO-D.

In the design of the TECO pilot test, ANVUR established a series of criteria dictated both by the awareness that it was an experiment (tight deadlines, limited budget, voluntary student participation) and by the need to collect as much data as possible (contextual variables) for a more complete understanding of test results:

1. Using the same test for all university courses, which would be evaluated in a uniform way with regard to all students because generic competences are by their nature independent of the specific field of study – they depend on how you study, not on what is being studied.

2. Using a test consisting of a) an open-response part that enables a check of reading ability, the critical analysis of texts and the ability to make coherent decisions therefrom as well as writing effectiveness and technique, and b) a closed-response part to evaluate the quality of scientific-quantitative reasoning.

3. Identifying eligible students (graduating students) i.e. those entitled to participate in the test if they are in a defined range of progress and maturity along the study path.

4. Limiting the objective to assessing acquired generic competences (the actual level of learning) and not the added-value of university education. This implies excluding freshmen from the test but allows for significant information to be delivered to stakeholders with shorter lead times. In principle, a longitudinal analysis (of the same people at the beginning and at the end of university studies) would be the best choice to determine university added-value but this would require a wait of at least 3-4 years.

5. Using contextual variables to enable filtering out of individual outcomes of the TECO (rebranded CLA+) that depend on both individual characteristics of the student population – for example, of a personal or family nature – and collective characteristics – for example, the rate of growth in the region of origin or the region where the university is located. This filters out individual characteristics that may account for certain students’ rapid and successful completion of studies. And it allows the added-value to be statistically estimated by analysing what remains of various multiple regressions.

Almost 30 universities offered to participate in the TECO pilot test. The following 12 (a pre-defined limit) were selected for the 2013 pilot: Eastern Piedmont (PO), Padua (PD), Milan (MI), Udine (UD), Bologna (BO), Florence (FI), Rome La Sapienza (RM1), Rome Tor Vergata (RM2), Naples Federico II (NA), Salento (LE), Cagliari (CA) and Messina (ME). This ensured universities with a mix of size characteristics and adequate regional representation (4 from the North, 4 from the Centre and 4 from the South plus islands); and excluded non-multidisciplinary universities.

Regarding the administration of the test, it was known that the people entitled to take the CLA+ were just under 20% of all students from the third and fourth years – excluding courses for the health professions –enrolled in the 12 participating universities, i.e. a population of 21 872 in academic year 2012-2013. In fact, 14 907 people pre-registered for the test – including numerous extraneous persons not eligible for the test – and, among those eligible and pre-registered, only about 5 900 students actually came to sit the test.

The 2013 TECO pilot test carried out by ANVUR was the first-ever attempt to assess the level of generic competences acquired by university students in Italy (Zahner and Ciolfi, 2018[2]). The mean proportion of eligible candidates out of students from the third and fourth year (regularity index, R) and the mean proportion of those who came to sit the test out of those eligible (participation index, P) range very broadly across the 25 disciplinary groups and the 12 participating universities.

In 2015, the same pilot experiment was carried out by ANVUR with the participation of 26 universities and over 6 000 students. Regarding the participation, the multivariate analysis carried out on some independent variables (such as age, average diploma grade, number of exams, average exam grade) showed that the student's age, the grade obtained at the high school diploma, and average exam grades, were in all cases significant (<0.05). In other words, the younger the student’s age and higher their grade at the diploma and university exams, the greater their participation in TECO. In addition to verifying the levels of generalist competencies through an additional specific questionnaire, the TECO pilots also provided for some background variables (such as demographic, environmental, socio-economic and cultural background-related data) of the participating students. These variables were in part collected during the registration phase of the CLA+ (basic information) and in part the day they took the test (mostly socio-economic and cultural background information).

The analysis showed a systematic downwards correlational relationship between the CLA+ result and the variables of age, female gender (versus male) and residence outside the region of the university's location. There was an upwards relationship relative to the variables of time since diploma obtained, coming from a “classical studies” high school (compared to other types of high schools), mean diploma and university grades, Italian citizenship and Italian spoken at home (versus non-Italian citizenship and language). The influence of parents appears in the sense that an absent mother (not father) lowers the CLA+ score, all other things being equal, and having a father employed in a managerial/professional position (but not a mother) raises it.

The effect of the socio-cultural condition was much stronger in simple correlations because in multiple regressions it is also exercised through diploma and university grades as well as in the choice of secondary school. Some contextual variables – such as, for example, family status – lose value once others are controlled. This is specifically because family status helps to predict the type of secondary school diploma, diploma grade, type of course of study chosen and average university grade in addition to predicting the result on the CLA+ test. On the other hand, in simple correlations, parents’ high professional and cultural status strongly correlated with success in the CLA+: when, regardless of the father's position, the mother has a managerial/professional position or a white-collar job, university degree or high-school diploma, results above the mean and the median were observed; and this applies equally to the father. The absence of at least one parent is the worst deprivation condition and is much worse than having a father or mother who is a manual labourer, unemployed or without qualifications.

The examination of simple correlations between all contextual variables and the result on the CLA+ test or its two components, complemented at times by looking at indirect correlation (e.g. with diploma and university grades), yielded some broad generalisations, not necessarily applicable to all the geographical macro-areas of Italy. Looking at the variables for family data, it was somewhat surprising that the cases where there are siblings at the university or not were observationally equivalent and likewise for living off-site with respect to the university or not. The size of the family seemed instead to have a negative effect, and likewise for the travel time required to reach university. Students with more technological equipment on average performed better, as well as those who go on at least one trip per year outside the region or abroad; this did not seem to influence the mean diploma grade but, rather, the mean grade on university exams.

Both CLA+ 2013 and 2015 experiments have highlighted some critical issues. The first was the self-selection bias of the universities and the students that joined the project and took the test, respectively. In the case of universities, the composition of the sample was defined more on the basis of the expression of their availability than on their representativeness. Regarding the selection of students, in addition to the criteria of the minimum number of ECTS obtained by students enrolled in the third year of a given university, the self-selection of the same students was also added, with an average participation rate of 20%, which prevented extrapolating the observations obtained to the entire student population.

The second critical issue was related to the scoring of the answers provided by the students. The open answers of the Performance Task (PT) test were codified by 239 scorers, identified among the faculty of the universities participating in the pilot, who evaluated the students' tests completely free of charge. For each university, a professor was identified as the Lead Scorer. After being trained by the Council for Aid to Education (CAE), the Lead Scorer had the responsibility of training and monitoring the assigned working group on scoring. In the Italian experience this multi-level training weakened the assessment system, increasing the gap in the coding, as indicated by a low correlation coefficient between the same scorers. On the basis of predefined quality parameters, a third evaluation was necessary in 52% of cases.

These critical issues led ANVUR to redefine the entire TECO in 2016. This included reference areas, related frameworks, methodological approach and tools. Regarding student participation, it comprised all students enrolled in the first cycle and single-cycle courses at a specific point in their career as they were more numerous (and therefore more relevant for public policy purposes), less self-selected (in respect to master's degrees) and more likely to enter the labour market.

Another important change concerned the timing of the delivering of the TECO: the number of CFU as a selection criterion was abandoned. Instead, the only administrative criterion was that students be enrolled. This choice was congruent with a value-added approach, which reflects the skills development during the university training and not just the initial characteristics of the students.

Unlike previously, the new TECO contained only closed-ended questions to facilitate coding and reduce variability between different scorers. And developing the test in-house overcame the problem of test adaptability to the Italian sample (Ciolfi et al., 2016[3]).

Finally, the already mentioned subdivision of the project into two parallel strands, TECO transversal (TECO-T) and TECO disciplinary (TECO-D), was another aspect on which ANVUR wanted to focus when redefining the project.

It was clear that TECO should continue to refer to transversal skills such as Literacy, Numeracy, Problem solving, Civics (intended as civic and political knowledge, and skills). Given their transversal nature, the assessment of these skills for university students could not reflect disciplinary knowledge acquired in the various bachelors’ programmes. However, ANVUR believes that transversal skills can be improved during university studies, and they are not the end state of an individual's cognitive development (Benadusi and Stefano, 2018[4]).

In particular, the TECO-T was carried out by the agency with a top-down process that involved groups of selected experts, consisting mainly of university professors. The detection of disciplinary skills was granted by autonomous disciplinary-focused working groups, supported by ANVUR. Briefly, after analysing and identifying the core disciplinary content of a study programme, they organised them with respect to the five Dublin Descriptors. After this preliminary phase, each working group was responsible for drafting the actual discipline-specific TECO-D.

Source: ANVUR

Participation in the project was still voluntary for universities, study programmes and students. The tests were aimed at students enrolled in the first and last year of the study programme. The results of the tests were communicated individually to the participating students and anonymously to programme managers and did not affect any assessment by the faculty or the final grade of the degree.

The skills assessed in TECO-T are Literacy, Numeracy, Problem Solving and Civics. The working hypothesis is that these skills draw on a generalist training background. They can be trained in university, regardless of discipline-related content, and the skills are therefore comparable between universities and/or study programmes (Rumiati et al., 2018[5]). The agency carried out the TECO-T tests with the collaboration of experts consisting mainly of university professors, following a top-down process.

The first tests carried out and validated (I and II field trials in 2016) were Literacy and Numeracy.

The Literacy test was designed to assess students' ability levels in understanding, interpreting and reflecting on a text that was not directly related to a specific disciplinary content or a subject area, using two types of tests: a text followed by closed-ended questions and a short text in which some words had been deleted (Cloze test) that the student must re-enter.

The Numeracy test measures students' ability levels in understanding and solving logical-quantitative problems through a short text accompanied by graphs and tables followed by some questions or an infographic picture followed by some short questions.

During the 2019 edition, two new TECO-T were validated: Problem Solving and Civics.

The Problem Solving test evaluates the level of understanding and ability to solve simple and complex problems as well as the ability to achieve objectives in a given context where they cannot be achieved with direct actions or with known chains of actions and operations (Checchi et al., 2019[6]).

Finally, the Civics test evaluates personal, interpersonal and intercultural skills that concern forms of behaviour that characterise people that participate actively and constructively in social and working life, and can resolve conflicts where necessary. At the base, there is the understanding of concepts such as democracy, justice, equality, citizenship and civil rights.

The so-called disciplinary skills, unlike transversal ones, are closely linked to the specific contents of study programmes and can only be compared between programmes of a similar disciplinary field.

The development of TECO-D was coordinated by ANVUR but carried out by working groups appointed by the governing board of ANVUR. Members of those working groups were university professors and researchers in a specific disciplinary field who voluntarily participated in the project. They were selected to represent the whole of academia and scientific organisations.

TECO-D working groups determined the core disciplinary contents of a group of homogeneous programmes to develop a comprehensive disciplinary test.

Joining the TECO-D presents innovative aspects for the academic community for various reasons:

It stimulates a shared definition of core disciplinary contents and their organisation with respect to the Dublin Descriptors;

It fosters the drafting of tests with shared content at the level of homogenous groups of study programmes, allowing inter- and intra-university comparisons for self-assessment purposes;

It guarantees centralised and certified management by ANVUR (delivering, data collection and analysis).

To help disciplinary working groups reach their objectives, ANVUR prepared two main tools containing useful information for:

how to determine core disciplinary content according to the Dublin Descriptors (Working document n.1).

how to correctly prepare a test (Working document n.2).

The agency also provided technical-scientific support to the working groups for the validation of the prepared tests.

Since 2016, each year ANVUR proposes specific time windows for the delivering of the TECO-T and TECO-D tests, generally between October and December. The activity is co-ordinated by the disciplinary groups and the tests are delivered using an online platform managed by CINECA11. Once the delivering window is closed, ANVUR proceeds with the analysis. Meanwhile, every participating student can download their personal certificate of achievement by accessing a dedicated portal with the same personal credentials used to access the test. The single result (average 200 and standard deviation 40) is calculated by standardising the scores obtained by all respondents on the basis of the two-parameter Rasch probabilistic model, which allows both the ability of the respondent and the difficulty of each question to be considered.

The results obtained in the TECO are not recorded in the student's university career.

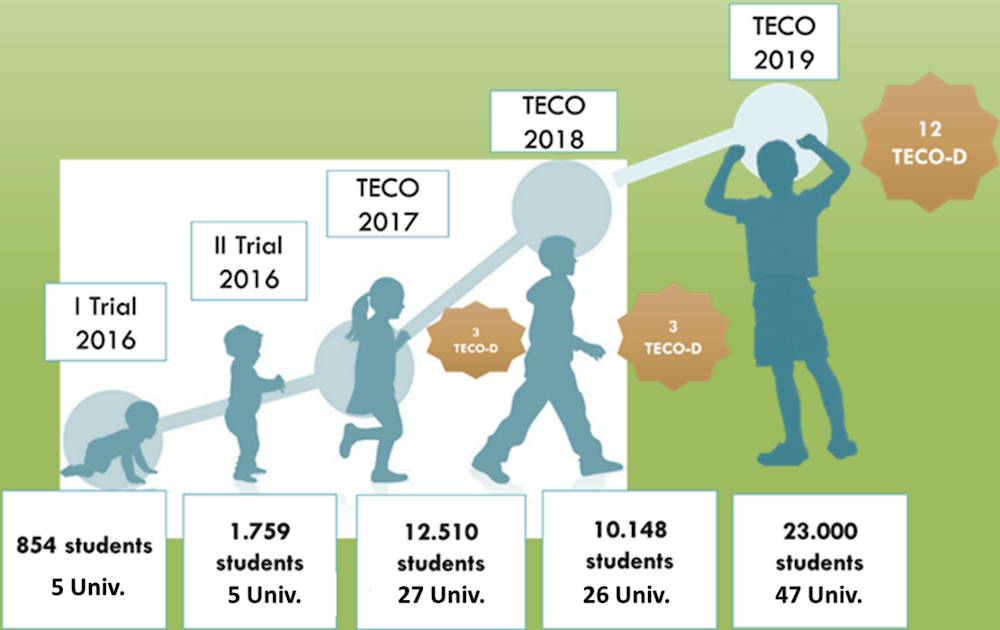

The first TECO experiment developed by ANVUR (with the collaboration of a group of experts) was a pilot of the TECO-T (Literacy and Numeracy only). ANVUR delivered it at the end of 2016 in order to validate the tests through a field trial. The pilot took place in five universities involving specific students: University of Messina (Economics), University of Padua (Psychology), University of Rome “Tor Vergata” (Medicine), University of Salento (Literature) and the Polytechnic of Turin (Engineering). This first pilot involved 854 students enrolled in the first and third year of the first cycle (bachelor’s). The consequent analysis by ANVUR showed that all individual items measured specific skills, represented different levels of difficulty and were able to distinguish the most competent students from others.

In particular, regarding the Literacy test (booklets 1 to 6), a good internal consistency was measured by the Cronbach's Alpha, meaning that the tests were able to measure a single competence. The items in the different booklets were similar in difficulty, reflecting the test design criteria.

|

Literacy 1 |

Literacy 2 |

Literacy 3 |

Literacy 4 |

Literacy 5 |

Literacy 6 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Number of valid tests (students) |

144 |

142 |

142 |

142 |

142 |

142 |

|

Mean Score |

19.85 |

18.71 |

21.05 |

18.03 |

19.39 |

19.04 |

|

Std. Dev. |

4.04 |

3.70 |

4.79 |

4.44 |

3.81 |

3.63 |

|

Variation coefficient - CV |

20.3 |

19.7 |

22.8 |

24.6 |

19.7 |

19.1 |

|

Cronbach’s Alpha |

0.777 |

0.675 |

0.796 |

0.766 |

0.664 |

0.689 |

|

Ease Mean |

0.66 |

0.62 |

0.70 |

0.60 |

0.65 |

0.63 |

|

Point biserial correlation |

0.39 |

0.31 |

0.39 |

0.39 |

0.32 |

0.32 |

|

Number of revised items |

10 |

8 |

7 |

9 |

7 |

10 |

Source: ANVUR analysis

Regarding the Numeracy test (booklets 1 to 4), the Cronbach's Alpha is near 0.8, meaning that the tests were able to measure a single competence. The items in the different booklets were similar in difficulty, reflecting the test design criteria.

|

Numeracy 1 |

Numeracy 2 |

Numeracy 3 |

Numeracy 4 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Number of valid tests (students) |

214 |

214 |

213 |

213 |

|

Mean Score |

13.31 |

15.91 |

14.99 |

15.59 |

|

Std. Dev. |

4.81 |

4.50 |

4.87 |

5.17 |

|

Variation coefficient - CV |

36.1 |

28.3 |

32.5 |

33.2 |

|

Cronbach’s Alpha |

0.848 |

0.799 |

0.829 |

0.837 |

|

Ease Mean |

0.53 |

0.64 |

0.60 |

0.62 |

|

point biserial correlation |

0.41 |

0.40 |

0.42 |

0.45 |

|

Number of revised items |

6 |

5 |

4 |

2 |

Source: ANVUR analysis

After the analysis, ANVUR revised all booklets in order to solve some minor problems related to specific items (see tables). During the Spring of 2017, the final versions of the Literacy and Numeracy tests were delivered to 1 759 students enrolled in the first and third year of the first cycle (bachelor’s) in five other universities (Bari, Bologna, Firenze, Milano “Bicocca”, Palermo), taking into account only five disciplinary areas selected by ANVUR (Biology, Education, Psychological Sciences, Economics and Health Professions).

In Spring 2017, the TECO additionally delivered (at the end of the test) a questionnaire that provided useful information about students’ family background and other personal experiences related to university and working daily life.

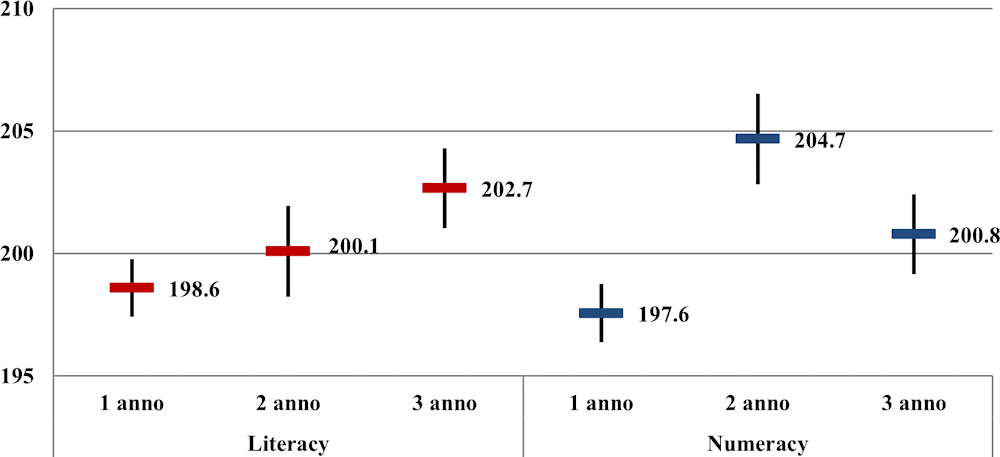

After test validation, a national TECO pilot took place between November 2017 and March 2018. With the TECO-T (Literacy and Numeracy) the following TECO-Ds were delivered to students enrolled in those specific study programmes after the TECO-T: Physiotherapy, Nursing, Medical Radiology. Overall, this pilot involved 27 universities across the country and a total of 12 510 students on a voluntary basis. A total of 481 test sessions were activated on the CINECA platform and 146 classroom tutors appointed by the participating universities monitored delivery.

Since it was not possible to set up an adequate number of test rooms equipped with computers for some universities, a paper-based method of test delivering was provided to allow all the universities to participate in the pilot.

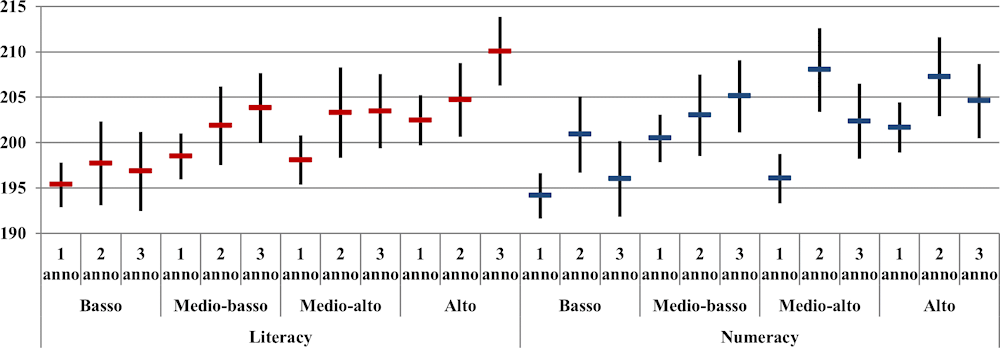

The overall results for all students (without distinguishing them by university or study programme) showed that the differences between the mean scores are statistically significant between first- and third-year students for both Literacy and Numeracy. A statistically significant increase in the students’ skills during their university studies was observed, albeit with a progressive growth for the Literacy-related ones, and with a significant decrease for the Numeracy-related ones between second and third year. It should be noted that at the beginning of their studies, students recorded a level below the set average value (200) in both areas (198.6 for Literacy and 197.6 for Numeracy) (Ciolfi and Sabella, 2018[7]).

Note: 1 anno = first year, 2 anno = second year, 3 anno = third year

Source: ANVUR analysis

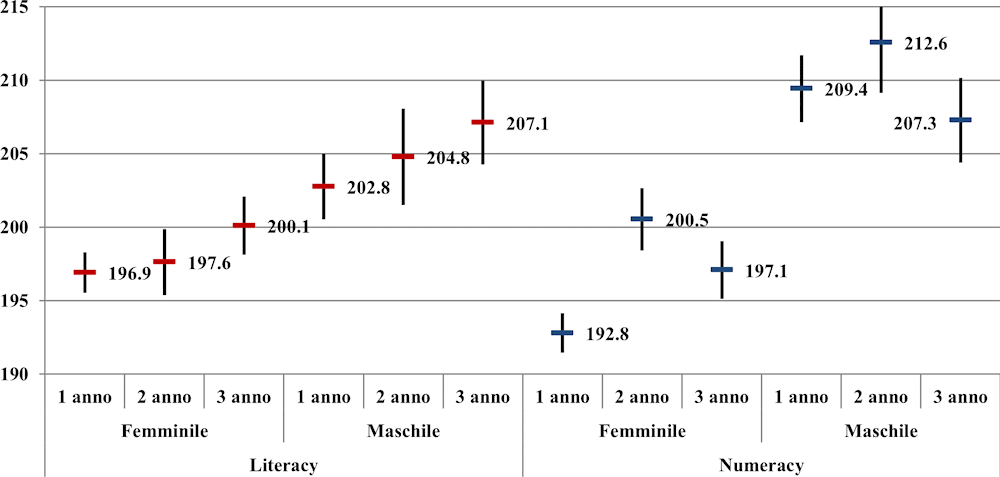

The following figure shows the same results by gender, suggesting that girls, while showing the same trend as boys over the three years, reach significantly lower levels, in particular for Numeracy. Notably, by separating the data by gender, the differences between the first and third year for Literacy are not statistically significant.

Note: Femminile = female, Maschile = male

Source: ANVUR analysis

During the pre-enrolment phase for TECO, students were asked to answer a questionnaire relating to their parents’ educational qualifications, profession and type of occupation and other background information. With this information it was possible to calculate a status index inspired by the Index of Economic, Cultural, and Social Status (ESCS) used in the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) reports. The ESCS is one of the most common used variables in the analysis of data from the PISA programme. It is based on student responses to a context questionnaire, built to achieve information about educational opportunity and inequalities. The calculation for the TECO involves the synthesis by Principal Component Analysis (ACP) of two variables: the score attributed to the highest occupational status of the parents (Ganzeboom and Treiman, 1996[8]) and the highest number of years of education achieved by the parents. Based on the quartiles, four classes were identified, the aggregate results of which are shown in the table below. It clearly emerges that the family context (with the related cultural and / or economic stimuli) affects the skills development of students, in particular for students with advantaged backgrounds (Ciolfi and Sabella, 2018[7]).

Note: basso = bottom quartile, medio-basso = second quartile, medio-alto = third quartile, alto = top quartile.

Source: ANVUR analysis

The 2018 TECO pilot had the same characteristics as the TECO-T (Literacy and Numeracy) and the Nursing, Physiotherapy, and Medical Radiology TECO-Ds that were delivered to students enrolled in those specific study programmes (Galeoto et al., 2019[9]).

Overall, this pilot involved 26 universities across the country and a total 10 148 students on a voluntary basis. A total of 450 test sessions were activated on the CINECA platform and 153 classroom tutors appointed by the participating universities monitored the delivery.

Nursing students were the most numerous in absolute number (7 557), followed by those in Physiotherapy (1 655) and Medical Radiology (936).

During the TECO 2019 edition, which took place between September and December, 47 universities participated throughout the country, with a total of 21 929 students. The participating students were enrolled in 12 different first-level study programmes in the medical-health area22. A specific TECO-D was developed and delivered for each one. In addition, two new TECO-T areas were statistically validated: Problem Solving and Civics. More specifically, a selected group of 4 050 students answered the new Problem Solving or Civics test. Students were from 41 universities, enrolled in the Medical Radiology, Philosophy and Education Sciences study programmes. The validation of the tests showed good reliability and validity for both tests.

Starting with the TECO 2020 edition, students were given a single TECO-T booklet containing tests for all the four validated areas Literacy, Numeracy, Problem Solving and Civics.

For the TECO 2020/2021 edition a new delivery system was developed in compliance with current regulations to prevent the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic.

ANVUR decided to carry out the delivery of the test remotely, meaning that every student was connected from home with their personal device. The students’ recognition system, the block of web pages during the test and the management of virtual classrooms (with the help of an online tutor) were defined together with CINECA.

To allow for easy organisation of the TECO, two delivery windows were defined instead of one: the first was from 20 October to 31 December 2020, the second from 1 March to 31 May 2021.

The TECO 2020/2021 was organised in two distinct parts as in previous years: a TECO-T and TECO-D (if available for the study programme in which the student was enrolled). Each student had to complete both parts. Only students who completed the TECO-T would be able to take the TECO-D. In any case, a break was guaranteed between the two phases.

The TECO-T is a single 50-minute test with reference to Literacy, Numeracy, Problem Solving and Civics. Two different sets of the TECO-T were randomly assigned to students, also within the same virtual classroom.

The TECO-Ds all last 90 minutes. During the first window (October-December 2020) Health Professions, Education and Psychology were delivered; during the second window (March-May 2021) Philosophy, Psychology, Education, Classics and Modern Letters and Medicine TECO-Ds were administered.

Some 19 292 students from 54 universities participated in the first window (October-December 2020). The tests were carried out in 48 days for a total of 1 282 test sessions (an average of 26.7 sessions per day) for an average of 402 tests per day.

|

Disciplines |

N. of virtual classrooms |

N. of students |

Participating universities/total universities* |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Dietetics |

42 |

510 |

12/22 |

|

Physiotherapy |

104 |

1 868 |

17/41 |

|

Nursing |

451 |

10 204 |

21/42 |

|

Childhood nursing |

11 |

192 |

6/8 |

|

Speech therapy |

36 |

557 |

9/29 |

|

Neuro and Psychomotricity of the developmental age |

29 |

646 |

8/12 |

|

Obstetrics |

74 |

1 222 |

17/33 |

|

Education |

155 |

1 155 |

20/42 |

|

Psychology |

253 |

1 186 |

28/42 |

|

Biomedical laboratory techniques |

53 |

675 |

16/35 |

|

Medical radiology techniques |

69 |

820 |

20/39 |

|

Occupational therapy |

19 |

257 |

7/8 |

|

Total |

1 296 |

19 292 |

Note: *Number of participating universities / number of universities that offer that study programme.

Source: ANVUR analysis

For students who participated in the second window (March-May 2021), the week 19-22 April 2021 was dedicated exclusively to students enrolled in Medicine and Surgery single-cycle master’s programmes (Bacocco et al., 2020[10]). The whole operation was carried out in four days for a total of 5 924 students from 29 universities with 721 virtual classroom tutors.

|

University |

N. of students |

|---|---|

|

TORINO |

768 |

|

Napoli Federico II |

713 |

|

ROMA "La Sapienza" |

630 |

|

CATANIA |

534 |

|

BRESCIA |

315 |

|

MILANO-BICOCCA |

300 |

|

FIRENZE |

289 |

|

MOLISE |

289 |

|

MILANO |

287 |

|

ROMA "Tor Vergata" |

201 |

|

PISA |

163 |

|

TRIESTE |

163 |

|

PADOVA |

158 |

|

BOLOGNA |

140 |

|

PIEMONTE ORIENTALE "Amedeo Avogadro"-Vercelli |

134 |

|

SALERNO |

113 |

|

INSUBRIA Varese-Como |

97 |

|

MODENA e REGGIO EMILIA |

90 |

|

FERRARA |

86 |

|

VERONA |

83 |

|

"Campus Bio-Medico" di ROMA |

81 |

|

MESSINA |

74 |

|

"Magna Graecia" di CATANZARO |

54 |

|

L’AQUILA |

37 |

|

Campania "Luigi Vanvitelli" |

36 |

|

FOGGIA |

35 |

|

PARMA |

22 |

|

"G. d'Annunzio" CHIETI-PESCARA |

20 |

|

BARI ALDO MORO |

12 |

|

Total |

5 924 |

Source: ANVUR analysis

Currently, ANVUR is focusing on the analysis of this last Medicine and Surgery field trial. Once the analysis is completed, each student can download their certificate of achievement certified by ANVUR.

Over the last few years, the main political decision maker in the field of higher education (namely, the Ministry of Education, University and Research) has been characterised by deep and continuous changes in top management and internal organisation due to the instability of the national government.

These changes have not favoured the continuity of dialogue between the government, ANVUR, academia, the labour market and all other relevant stakeholders. This has hindered the development of a shared vision with respect to the assessment of students’ generic learning outcomes promoted by ANVUR with the TECO. This partly explains why a well-defined national project is still lacking and consequently there have been no developments with reference to the regulatory framework. TECO continues to be a project, an initiative characterised by participation on a voluntary basis.

However, recently the Italian government has divided the relevant Ministry, creating an independent Ministry of University and Research. The establishment of a dedicated Ministry has been very positively received by the academic community, who hope that this government reorganisation will provide added-value to the higher education sector and confer greater impact on the specific themes and issues of higher education to the political agenda at the national level.

Even within ANVUR important changes are expected. The political body (Government Board) is redefining the AVA system according to the principles of simplification and greater attention to the evaluation of results. The review of the national accreditation and assessment system is an important opportunity to discuss the role of TECO and more generally the role of the measurement of learning outcomes in enhancing the evaluation of results.

In this period, the agency started drafting the Report on Italian University and Research system 2021 in which ANVUR captures (supported by longitudinal analysis) the university and research situation in Italy. It proposes critical reflections on strengths and opportunities, and aspects to be improved. Like its predecessors, the 2021 report will have a chapter dedicated to the assessment of learning outcomes and the TECO. This comprehensive report, like the previous, will be published on the website and presented in a dedicated public event to the relevant decision makers and stakeholders.

Finally, it is important to emphasise the importance of the latest developments of the TECO-D. The establishment of the working group of Medicine has focused the academic community’s attention on the TECO. Currently, there is a strong debate about the assessment of skills and competences in the health sciences and possible content contamination between the Medicine and Surgery single-cycle master’s programme and health professions first-cycle programmes. The 2021 report will show results of the first field trial of students enrolled in Medicine and Surgery.

Regardless of future developments, it is clear that interest in the assessment of generic and disciplinary learning outcomes is growing as shown by the increasing participation in the TECO by universities, students and the establishment of disciplinary working groups. The academic community and ANVUR believe that it is essential to deepen the analysis of teaching and learning results, particularly generic learning outcomes, for the purpose of continuous improvement. Tools like the TECO can certainly help in the analysis.

[3] ANVUR (ed.) (2016), “La sperimentazione sulla valutazione delle competenze attraverso il test sulle competenze (TECO – 2013 e 2015)”, Rapporto sullo Stato del Sistema Universitario e della Ricerca 2016, pp. 259-287.

[10] Bacocco, B. et al. (2020), “Medicina alla prova. La validazione del Progress Test a cura dell’ANVUR (Testing mdeical studies. The validation of the Progress Test by ANVUR)”, Medicina E chirurgia, Journal of Italian Medical Education 85, pp. 3819-3816, https://doi.org/10.4487/medchir2020-85-6.

[4] Benadusi, L. and M. Stefano (eds.) (2018), Le competenze: Una mappa per orientarsi (Universale paperbacks Il Mulino Vol. 729), Fondazione Agnelli, Bologna: Il Mulino.

[6] Checchi, D. et al. (2019), Il Problem Solving come competenza trasversale: inquadramento e prospettive nell’ambito del progetto TECO, Scuola Democratica, https://doi.org/10.12828/93404.

[1] ESG (2015), Standards and Guidelines for Quality Assurance in the European Higher Education Area, Brussels, Belgium (ISBN: 978-9-08-168672-3).

[9] Galeoto, G. et al. (2019), The use of a dedicated platform to evaluate health-professions university courses, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-98872-6_33.

[8] Ganzeboom, H. and D. Treiman (1996), “Internationally comparable measures of occupational status for the 1988 International Standard Classification of Occupations”, Social Science Research, Vol. 25/3, https://doi.org/10.1006/ssre.1996.0010.

[7] Momigliano, S. (ed.) (2018), “La rilevazione delle competenze degli studenti: il progetto TECO”, Rapporto Biennale sullo stato del sistema universitario e della ricerca, pp. 155-166.

[5] Rumiati, R. et al. (2018), “Key-competences in higher education as a tool for democracy”, Form@re, Vol. 18, pp. 7-18, https://doi.org/10.13128/formare-24684.

[2] Zahner, D. and A. Ciolfi (2018), “International Comparison of a Performance-Based Assessment in Higher Education”, in Assessment of Learning Outcomes in Higher Education, Methodology of Educational Measurement and Assessment, Springer International Publishing, Cham, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-74338-7_11.

← 1. CINECA is a not-for-profit Consortium developing advanced Information Technology applications and services. It is made up of 97 members: the Italian Ministry of Education, the Italian Ministry of Universities and Research, 69 Italian universities and 26 Italian National Institutions (ANVUR included). Today it is the largest Italian computing centre.

← 2. Study programmes are: Pedagogy, Nursing, Physiotherapy, Dietetics, Childhood Nursing, Speech therapy, Neuro and Psychomotor Therapy of the Developmental Age, Obstetrics, Biomedical Laboratory Techniques, Occupational Therapy.