J. Enrique Froemel

Pontifical Catholic University of Valparaíso, Chile

Does Higher Education Teach Students to Think Critically?

15. CLA + in Latin America: application and results

Abstract

Although the chapter’s title refers to the region, CLA+ was implemented only in Chile. Nevertheless, higher education in Latin America will be briefly described because reactions to the wider outreach effort are still pending in various countries. In Ibero-America (Latin America plus Portugal and Spain) the annual higher education average enrolment rate increased by 3.5% between 2010 and 2016, totalling almost 30 million students (OEI, 2018[1]). According to Trow’s (Trow, 2008[2]) classification, Argentina, Chile, Spain, and Uruguay are already at the universalisation stage with gross higher education enrolment rates over 50% (OEI, 2018[1]). The remaining countries are at the expansion stage with rates going from 15 to 50%.

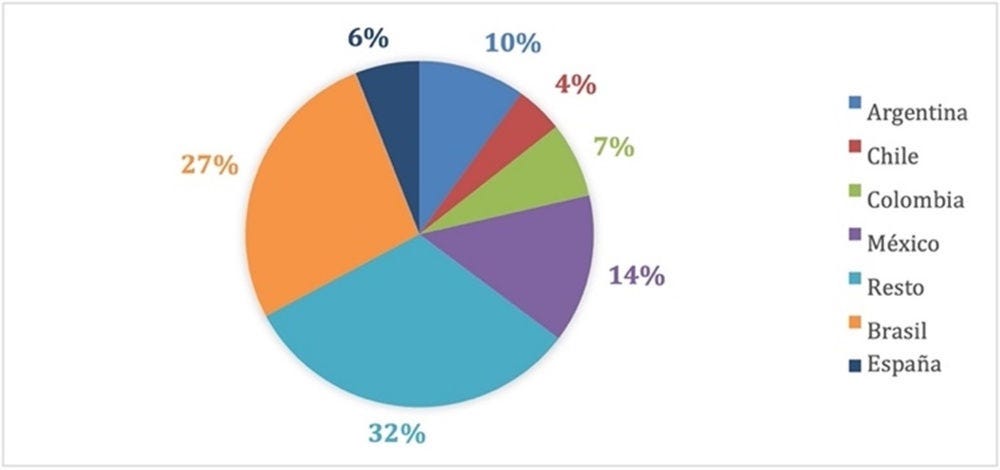

Figure 15.1. Higher education student percentage by country in Latin America (2018)

Source: OEI-Observatorio CTS (2021[3]), Papeles del Observatorio Nº 20, Abril 2021: Panorama de la educación superior en Iberoamerica a través de los indicadores de la Red Indices. http://www.redindices.org/novedades/139-papeles-del-observatorio-n-20-panorama-de-la-educacion-superior-en-iberoamerica-a-traves-de-los-indicadores-de-la-red-indices (accessed on 26 April 2021).

Chile

Chile’s higher education structure dates from 1981 when a radical, deep, and somewhat controversial restructuring of the segment took place. It has been maintained since then with some changes. Three types of higher education institutions presently exist: universities, professional institutes, and technical training centres. Among those, only universities are entitled to grant all types of higher education credentials: academic, professional, and technical degrees, requiring five-year programmes for reaching the degree of “Licenciado”. They also teach one-year post-graduate diploma programmes; master’s degrees, doctoral degrees, and other advanced certificates (e.g. medicine and dentistry) (OECD/The World Bank, 2009[4]). Professional institutes can only grant four-year professional degrees below the bachelor’s degree level. (OECD/The World Bank, 2009[4]). Technical training centres can solely offer technical degrees in 2 to 2 1/2 year-programmes (OECD/The World Bank, 2009[4]).

Regarding the system’s size, 150 higher education institutions were operating in the country in March of 2020 (59 universities, 39 professional institutes, and 52 technical training centres) (Servicio de Información de Educación Superior SIES, 2020[5]).

Table 15.1. Number of higher education institutions by type, in 2013

|

Higher education institution type |

Institutions (2013) |

|---|---|

|

Public state, CRUCH members |

16 |

|

Private, not for profit, with public orientation, CRUCH members |

9 |

|

Private, not for profit, non CRUCH members |

35 |

|

Universities subtotal |

60 |

|

Professional institutes |

43 |

|

Technical training centres |

54 |

|

Subtotal of non-university institutions |

97 |

|

Total |

157 |

Source: OECD (2017[6]), Education in Chile, Reviews of National Policies for Education, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264284425-en (accessed on 28 April 2021).

Three groups of autonomous higher education institutions have existed in Chile since 1981 as shown in Table 15.1. One, gathered under the Council of Rectors of Chilean Universities (CRUCH), created in 1954, includes all public-state universities and a group of private, not-for-profit public-oriented institutions. These private universities (9) existed before 1981 or were campuses of private institutions already operating at that time and later evolved into independent entities. All the CRUCH member institutions, public or private, have historically received direct state funding. Recently, two new public universities were created and joined the CRUCH with full status. Also, recently, three private universities, established after 1981, were admitted to the CRUCH, although they are not granted direct state funding, as opposed to all other CRUCH institutions.

A second group includes only private universities created after 1981 and constitutes the bulk of the existing university segment in the country (35). None of them can operate on a for-profit basis since Chilean law does not allow the existence of that type of educational institution.

The third group includes all existing professional institutes and technical training centres (43 and 54, respectively). All these institutions are private although the government is in the process of creating and establishing 15 new public technical training centres, distributed in some regions of the country (OECD, 2017[6]).

Over the past 40 years, higher education in Chile underwent explosive and uncontrolled growth, jumping from fewer than 20 institutions in 1981 to over 150. This growth meant an increase in higher education study opportunities for students of all social conditions since they were complemented by state financing programmes. Notwithstanding, higher education quality deteriorated, triggering the enforcement of more stringent accreditation norms and rules for creating new higher education entities. This has resulted in a serious overall quality drive at most institutions.

Student enrolment grew accordingly with the creation of higher education entities, reaching gross growth rates of over 50% in 2016, as reported earlier (OEI, 2018[1]). In 2020, however, a reduction in the upward trend of the number of applications to higher education institutions occurred, as shown in Table 15.2.

Table 15.2. Total enrolment variation by degree level 2016-2020

|

Degree level |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

Percent variation 2016-2020 |

Percent variation 2019-2020 |

Enrolment distribution 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Undergraduate |

1 178 480 |

1 177 177 |

1 187 873 |

1 194 310 |

1 151 727 |

-2.3% |

-3.6% |

94.3% |

|

Graduate |

47 584 |

48 698 |

46 875 |

48 391 |

45 483 |

-4.4% |

-6.0% |

3.7% |

|

Diploma |

21 114 |

22 418 |

27 588 |

25 803 |

23 807 |

-12.8% |

-7.7% |

1.9% |

|

Total |

1 247 178 |

1 248 293 |

1 262 336 |

1 268 504 |

1 221 017 |

-2.1% |

-3.7% |

100.0% |

Source: SIES (2020[5]), Informe 2020 Matrícula en Educación Superior, SiES, Santiago, https://www.mifuturo.cl/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Informe-matricula_2020_SIES.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2021).

The enrolment percentage differentials between female and male participation by field of speciality is a remarkable characteristic of the Chilean higher education system. Table 15.3 displays that in all areas except in two (Science and Technology), when female enrolment percentages have positive values, they are higher than males and when negative, those of males are higher. This is particularly evident in Health, Education, and Social Science. What is even more striking is that in those areas where females show higher enrolment differentials, there is also an upward trend for the considered years.

Table 15.3. Undergraduate enrolment percentage differential between female and male, by field of speciality, between 2005 and 2020

|

Field of speciality |

2005 |

2011 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Administration, business, and commerce |

-1.96 |

5.94 |

10.25 |

10.04 |

11.41 |

11.95 |

12.65 |

|

Agriculture, forestry, fisheries, and veterinary medicine |

-12.21 |

-5.02 |

1.5 |

2.23 |

4.22 |

6.41 |

10.57 |

|

Art and architecture |

-7.45 |

-2.30 |

0.04 |

1.85 |

2.51 |

3.35 |

4.70 |

|

Science |

0.04 |

-1.26 |

-7.39 |

-7.21 |

-7.74 |

-8.42 |

-9.99 |

|

Social science |

38.28 |

38.24 |

40.35 |

38.86 |

41.29 |

41.89 |

42.46 |

|

Law |

1.84 |

3.64 |

6.59 |

8.54 |

8.93 |

10.01 |

11.64 |

|

Education |

39.78 |

37.02 |

45.43 |

47.92 |

50.76 |

50.38 |

50.95 |

|

Humanities |

17.01 |

11.52 |

10.71 |

11.83 |

9.77 |

9.19 |

10.32 |

|

Health |

39.22 |

47.17 |

52.26 |

52.23 |

52.08 |

52.34 |

52.31 |

|

Technology |

-63.91 |

-59.63 |

-56.22 |

-56.78 |

-58.77 |

-59.87 |

-59.63 |

Source: CNED (2020[7]), Informe Tendencias de Estadísticas de Educación Superior por Sexo, CNED, Santiago. https://www.cned.cl/sites/default/files/2020_informe_matricula_por_sexo_0.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2021).

CLA+ outreach process in Latin America and Spain

The Council for Aid to Education (CAE), through its Fellow in Latin America, based in Santiago de Chile, deployed an outreach effort in the region between 2017 and 2021. Selected higher education entities, including universities and institutes as well as ministries, university associations, and supporting agencies were contacted. Approach and information activities took considerable time and consisted of an iterative process including information provision and discussion as well as question-formulating and answering between the Fellow and each of the institutions.

Latin America is understood here as composed only of countries in South America, Central America, and the Caribbean since Mexico’s participation in CLA+ was initially handled separately. Nevertheless, after 2020 Mexican institutions were also included, as depicted below.

Duration and difficulty of the outreach process could be attributed to two sources, namely: a widespread but incipient development of the General Studies curriculum where Critical Thinking constitutes a key set of competencies; and a generalised misunderstanding of characteristics and a pervasive distrust of standardised testing.

Considering the high value attributed to university autonomy in Latin America, most contacts with universities and institutes were individual. Ministries were only reached for them to be informed about the existence of the CLA+ Study in the region. Nevertheless, collaboration from university independent supporting entities active in the region such as the Centro Interuniversitario de Desarrrollo (CINDA) and the Consejo de Educación Superior, in Paraguay, were sought and enlisted.

Up to 2020, only four universities, all from Chile, participated in CLA+, although several other promising contacts were already pending at the end of the outreach process and could not be finalised.

Table 15.4. CLA+ outreach in the region and Spain

|

Higher education associations and supporting entities |

04 |

|

Ministries of Education |

03 |

|

Higher education institutions (universities and others) |

64 |

|

Bolivia |

01 |

|

Chile |

28 |

|

Colombia |

13 |

|

Dominican Republic |

03 |

|

Ecuador |

01 |

|

Mexico |

36 |

|

Nicaragua |

01 |

|

Paraguay |

08 |

|

Peru |

09 |

|

Spain |

01 |

|

TOTAL |

71 |

Policy context for CLA+

Agreements signed between CAE and CLA+ participating institutions prescribe that institutional-level data are not to be disclosed together with entity identification. Consequently, the report anonymises individual institutions’ results, although for contextualisation some of their characteristics are shown and the four institutions are labelled with capital letters (W, X, Y, and Z).

The CLA+ participating universities in the region were all located in Chile. Though the approach to universities in Chile was carried out on an individual basis, direct contact was made concurrently with the Undersecretary of Education who later became Minister of Education. Later, the new Office of the Undersecretary of Higher Education was created, and contacts followed with the person appointed to that post. The purpose of that approach was exclusively to inform governmental authorities about CLA+, its characteristics, and the intended recruitment of institutions in the country to join the study.

Both authorities were extremely positive about the potential implementation of CLA+ in Chile due to two main reasons. The first one dealt with the already growing relevance of Critical Thinking as part of General Studies in higher education both globally and in Chile. The second stemmed from the CLA+’s high quality and objectivity vis-à-vis internal university assessment tools, designed and administered as it is by an external entity.

All four Chilean participating universities are private, though one has a public orientation and belongs to the Council of Rectors (CRUCH) while the other three do not belong to CRUCH.

University W

University W, which is outside CRUCH, was founded over 30 years ago and operates in various regions of the Chilean territory. It offers undergraduate and graduate programmes in most fields of speciality, organised into seven facultades (groups of schools) and operating research centres. This institution, with over 25 000 students, has successfully passed all prescribed cycles of institutional accreditation by the National Accreditation Commission (CNA-Chile) and has a growing research component. It started preparing for participation in the CLA+ in autumn 2017 (southern hemisphere).

This was the first university in the region and the country to enrol in the study. The main motivation of its president stemmed from the need to assess the outcomes of a new educational model being implemented at the time. Such a competency-based type model, applied for the first time in this university, introduced strong General Studies curricula effective in all programmes, including cognitive, affective, and performance elements. CLA+ was very timely as it could fulfil the university’s hard-data results requirements about student achievement in the cognitive component of the General Studies curricula model.

University X

University X belongs to the same group as W, and was founded in the early 1990s. It now enrols 7 000 students and includes most undergraduate programmes. It has also been successfully accredited by CNA in all cases. It operates six facultades and 12 research centres, with significant growth of the graduate segment in the past decade. It participated in CLA+ in 2020 over a timespan that, due to the pandemic, covered autumn and winter (southern hemisphere).

This institution has implemented significant curricular changes and a strong learning achievement assessment component. It grants high relevance to General Studies as well, establishing its own department. Consequently, CLA+ represented a timely and useful tool for standardised evaluation of Critical Thinking student achievement. Its approach was to apply CLA+ to gauge student achievement as the curriculum transformations were implemented and affected subsequent classes.

University Y

University Y is part of the same group as W and X, has over 30 years of existence, and is located in major urban locations. It has over ten facultades and several research centres. Presently, it enrols over 40 000 students in undergraduate and graduate programmes. It has successfully passed all the National Accreditation Commission’s mandatory institutional accreditation processes and has also obtained institutional accreditation abroad. Its first participation in CLA+ started in the summer of 2020 (southern hemisphere) and is still underway because of the pandemic, into the first semester of 2021.

As mentioned, University Y is institutionally accredited in the United States and although the Chilean system does not yet require institutions to provide evidence on General Studies student achievement, the U.S. regional agencies do. After exploring alternatives for fulfilling this need, University Y joined CLA+ in 2020 motivated by the need for formal provision of evidence as an institutional accreditation requirement. Nevertheless, the university also uses CLA+ data for diagnosing entering students’ mastery of Critical Thinking competencies; for gauging further learning of those same skills during university studies by testing the graduating class; and for obtaining an indication of value-added learning in those competencies as the differential between both classes.

University Z

University Z is a mature full member of the Council of Rectors with over 90 years of academic life and a history of very high-level institutional accreditation accomplishments. Its enrolment exceeds 15 000 students in undergraduate and graduate programmes (doctoral, master’s, and diploma). It has nine facultades and several research entities, and operates several campuses in a focused location in Chile. The initial CLA+ participation of University Z, due to the constraints posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, has been extended for almost two years, having started in 2019.

This institution recently updated its undergraduate and graduate education model. Such a change, on the one hand, implies adopting a competency-based curricular structure. On the other hand, it improves the definition of its education coverage into three broad areas of study: disciplinary, professional, and fundamental competencies (General Studies). A particular new emphasis is placed on General Studies, thus including eight different components, one of them being the Scientific Competency Area. This area requires students to develop scientific capacity including analytic, abstract, and critical thinking for problem solving, knowledge generation and self-learning skills. CLA+ was adopted as a valid and high-quality standardised assessment tool for evaluating the Scientific Competency Area.

In addition, this institution developed a special project for improving teacher-education programmes, funded by the state. This government grant support requires that all participating students be tested for achievement in those constructs included in Critical Thinking. Once again, CLA+ came in handy for assessing the entire 2020 entering class and its follow-up over the first three years of study.

Despite the small number of participant institutions in the region, the CLA+ application’s design versatility must be highlighted in the case of Chile. Although the actual application designs for each university will be described further on, it is relevant to point out here that in the four considered institutions where policy contexts and needs were different, the battery was able to adapt to those contexts and fulfil those different demands. In one case the purpose was summative assessment; in another it was diagnosis and obtention of learning gains (effect-size); in yet another, it was certification purposes evaluation; and in the last one, it combined cross-sectional learning achievement assessment in some programmes and longitudinal gains follow-up for a complete teacher education cohort over several years.

Process of implementation of the CLA+

As mentioned before, the outreach effort aimed at Chilean universities took place on an individual basis through direct contacts with each university. Initial contacts in Chile started in 2017 and were the first to begin in the region.

The battery test forms, originally in English, were already translated into Spanish, adapted to the language usage of South America, and were provided by CAE to the participating universities through an interactive Internet platform.

University W

The administration process at University W included three phases. A team from the Academic Vice-President’s Office took charge of the process, information exchange with CAE took place, and regular meetings were held. The preparation phase, among the university, the Fellow in Latin America, and the New York-based CAE team, began in April 2018.

Issues addressed included the appointment of counterparts and task definitions on each side; mutual exchange of requirements; technical aspects definition; agreement on the structure of the application design; decisions on the sample design, selection, and approval; relevant dates definition; training of university application teams; and solving of emerging problems. A deliberate, campus-stratified sample and a cross-sectional effect-size analysis design were agreed upon, including the 2018 entering and graduation classes.

The four-week implementation phase comprised the sample selection, identification and contacting of subjects, and testing platform trials. The sample was selected, and its database was uploaded to the CAE platform, and subject identities verified at the access to the testing facilities. Testing was part of the regular teaching activities and participation was consequently mandatory. Notwithstanding, according to Chilean law, every participating student signed an affidavit Consentimiento Informado (Informed Agreement), authorising the university to use his/her results for research and evaluation purposes. If the person did not sign the document, he/she would be deleted from the sample with no consequences whatsoever and replaced by another who would be willing to participate. In University W, no student rejections occurred and a low absentee rate was observed.

The administration phase was simultaneously executed in one week and students were tested in groups of approximately 30 subjects on-site at the university computer facilities and using institutional equipment. The administration was uneventful with a high completion rate of the sample. A total of 562 students belonging to the 2018 entering and graduation classes from the facultades of Administration and Business; Architecture and Construction; Education; Health Sciences; Law; and Social Sciences and Humanities in all four campuses were tested, as shown in Table 15.5.

Table 15.5. Subjects sample distribution at University W, by class and campus

|

Class |

Campus |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Campus I |

Campus II |

Campus III |

Campus IV |

Students |

|

|

Entering 2018 |

86 |

75 |

65 |

62 |

288 |

|

Graduating 2018 |

57 |

49 |

92 |

76 |

274 |

|

Total |

143 |

124 |

157 |

138 |

562 |

University X

University X was the second institution to join CLA+, in early 2019, and few meetings between the University authorities and the CAE Fellow for Latin America were deemed necessary. The decision was fast, and the process ended with the actual assessment considering the same customary three phases. The preparation phase included two video conferences with the CAE New York team for sample and application design discussion. The University’s General Studies Department head and some members oversaw the process and a swift information exchange process with CAE took place with regular communications and two video meetings. The issues addressed were the same as those covered in the previous case. The CAE Fellow proposed University X to receive feedback from Universidad W’s experience with CLA+. Contact was established, and interactions took place between both teams.

A deliberate, field-of-study programme-stratified sample, and a cross-sectional effect size analysis design, were planned. In this case, the comparison included three cohorts since student achievement on General Studies curriculum effects was to be explored over three subsequent classes.

The original implementation plan was altered by the effects of social unrest in the country and the COVID-19 pandemic. Consequently, only students belonging to the 2019 entering class could be tested on-site at university facilities, using institutional computers in October and November of that year. Those belonging to the 2017 and 2015 cohorts who could not take the test in the first place were scheduled for the online proctored mode application in 2020. The 2017 entering class was tested between November and December of 2020 as well as a small segment of the 2015 entering class, thus the planned three-class comparison was accomplished by only two. Since University X wants to build a follow-up of its General Studies curriculum application results over time, another application was agreed with CAE for 2021, including, this time, three entering classes: 2017, 2019, and 2021.

A similar process to that of University W was applied in X and participating students were selected, the database uploaded to the CAE platform and subject identities verified upon access to the testing facilities for the 2019 entering class. For the bulk of the 2017 entering class sample, proctored online testing protocol was used, and student identity was verified by the proctors before subjects accessed the testing platform. In this case, 5 groups of approximately 25 students and 1 proctor each were organised. Each student used his/her computing device (computer or tablet).

For X University students, the application was voluntary. This mode required a deeper and longer effort on the part of the university team to convince and follow up on subjects. This was expected to affect results since students voluntarily chose to participate. Initial absenteeism was higher than in the case of W and despite follow-up efforts implemented by the university team, final figures ran short of expectations. As legally prescribed by law, students also signed an agreement affidavit.

A total sample of 308 students belonging to the 2019 and 2017 entering classes was tested belonging to the facultades of Education; Engineering; Health Sciences; Medical Sciences; Science and Technology; and Social Science, as shown in Table 15.6.

Table 15.6. Subjects sample distribution at University X, by class

|

Entering class |

Students |

|---|---|

|

2019 |

220 |

|

2017 |

108 |

|

Total |

328 |

University Y

Although it was an early contact in Chile, it took time and several meetings for University Y to join CLA+. The first video conference was held as early as January 2019 with the CAE Fellow and the New York CAE team before the decision and signature of the agreement. The Director of the Humanities Department was appointed to be in charge of the CLA+ application. During the preparation phase, one video conference was held in September 2019 and several contacts took place with the CAE Fellow. Frequent e-mail correspondence was exchanged with the CAE New York team as well for discussing the design and the sample. Issues addressed were coincident with those covered by universities W and X. The CAE Fellow proposed University Y to receive feedback from Universities W and Z experience in the application of CLA+ and interactions occurred between Z and Y. Since the faculty official in charge of CLA+ at this university had a good user-level knowledge of assessment issues, preparation and application phases were swiftly organised and management was autonomous. From the start, University Y decided its participation in CLA+ would be cyclical in the sense that the battery would be applied on a biennial basis to serially gauge their learning achievement in General Studies.

A deliberate, field-of-study programme-stratified sample, and a cross-sectional effect size analysis design, were planned for the 2020 and 2017 entering classes. Both sample and design were submitted by the university and approved by the scientists at the CAE New York team. Results of this application were considered among the evidence required by a U.S. regional agency for accreditation validation in 2021 in addition to providing feedback on these classes’ General Studies curriculum learning results.

As in the case of University X, the implementation plan was negatively affected by the 2019 period of social unrest in the country and the COVID-19 pandemic. This delayed administration until late 2020 and required use of an online proctored protocol instead of the on-site procedure originally planned. In addition to the delay, the sample could not be entirely tested during this period and the remainder underwent further testing in the first semester of 2021 to complete the graduating class component. In keeping with the university’s intention of a longitudinal series of CLA+, a potential new testing process is expected for 2023.

The mechanics of the process at University Y were like those at W and X. Students in the sample were chosen, the database uploaded to the CAE platform and subject identities verified by proctors before accessing the online testing platform. The administering of the test to both cohorts, which was supervised by externally hired proctors trained by the university, took place between September and December of 2020. Testing of the remaining 2017 entering class is still pending and should be completed during the first half of 2021. Each proctor oversaw approximately 100 students. Each student used his/her computing device (computer or tablet). Test-taking for students was voluntary. And as was the case for Universities W and X, students signed affidavits.

A total of 882 students belonging to the 2020 and 2017 entering classes were tested out of 11 facultades. The sample shown in Table 15.7 focused on Economics and Business; Education; Humanities and Social Sciences; Engineering; Law; Medicine; and Nursing. The other two groups tested, although on a lesser scale, were Exact Sciences and Life Sciences.

Table 15.7. Subjects sample distribution at University Y, by class year

|

Entering class |

Students |

|---|---|

|

2020 |

662 |

|

2017 |

220 |

|

Total |

882 |

University Z

This institution was the second in the country to agree to participate in CLA+, in January 2019. The CAE Fellow started consultations with its top officials in July 2018. A video conference attended by the Academic Vice-President and his staff, the CAE New York team and the Fellow in Latin America was held in August of that year to finalise the decision.

A team led by the Student Development Director, which included three other officials, was appointed to be in charge of the CLA+ application. Before actual applications started, the team held three remote meetings with the CAE Fellow and the New York team over similar issues as those covered in the other three Chilean participating universities. In this case, it was helpful that a multidimensional team (including administration, computer, and statistics professionals) was in charge as sample and design structures posed multiple, diverse, and complex challenges.

University Z’s CLA+ participation was different from the rest due to testing being performed over several years and over two different cohorts. The cohorts consisted of students from the Engineering and the Teacher Education programmes. For Engineering, deliberate samples of each year’s entering and graduating classes were defined. For Education, the entering class was tested on a census basis. Different comparison designs were applied for each of the cohorts. In the case of Engineering, a yearly cross-sectional, effect size comparison of entering and graduating classes was included. In the case of Education, two comparisons were planned: one was a yearly, cross-sectional, effect size, class, census comparison; and the other was a longitudinal census comparison of entering classes over three years, starting in 2019. Both sample/census structures and comparison designs were submitted, discussed, and approved through contacts between the university and the scientists of the CAE New York team. All subjects were to be tested on-site at the university computer facilities, using institutional equipment.

As in the X and Y universities’ cases, the 2019 period of social unrest in Chile and the COVID-19 pandemic caused serious drawbacks in University Z’s testing implementation plan that year. The original application for 2019 was expected to finish in December of 2019, and it did with only partial coverage of the 2019 entering classes for both cohorts and no subjects from the graduating classes at all. Consequently, those from the 2019 entering class subjects who had not been tested were tested over several sessions from August to December 2020. This required the use of an online proctored protocol instead of the on-site mode originally planned. Adding to the delay, the 2019 graduating class subjects could not be tested at all so no cross-sectional effect size analyses could be performed for the 2019 data as only one-shot testing had occurred. As University Z planned a longitudinal series of applications of CLA+ between August and December of 2020, a testing process parallel to that for remaining 2019 subjects was implemented using online proctoring for the corresponding populations and classes belonging to that year.

The test-taking process at University Z had only minor differences from those of W, X, and Y. Students in the sample were chosen by the university and the database was uploaded to the CAE platform. In 2019, supervisors verified subject identities before entering the testing facilities. In the 2020 online administering of the test, proctors checked test-takers’ identifies before they accessed the testing platform. University supervisors and proctors were trained by the university and groups of approximately 50 students were organised in both modes. In the online mode, five proctors oversaw 10 students each and each student used his/her computing device (computer or tablet). As planned, new applications should be performed in 2021 although only cross-sectional effect size analyses will be calculated, thus discontinuing the planned longitudinal trend. Test-taking at University Z was voluntary and took place during regular teaching hours. This option required students to be followed individually to ensure attendance at testing sessions. Consent was verbally provided via telephone contact. Only students who formally agreed to be tested were provided with the test platform link.

As shown in Table 15.8, 1 341 students, belonging to the 2019 and 2020 cohorts were tested, from the Engineering and Teacher Education programmes. Students from five of the facultades participated: Agronomic and Food Sciences; Economics and Business; Engineering; Philosophy and Education; Sea Sciences and Geography; and Science.

Table 15.8. Subjects sample distribution at University Z, by class

|

Class |

Students |

|---|---|

|

Entering 2019 |

567 |

|

Entering 2020 |

623 |

|

Graduating 2020 |

151 |

|

Total |

1 341 |

Main results

University W

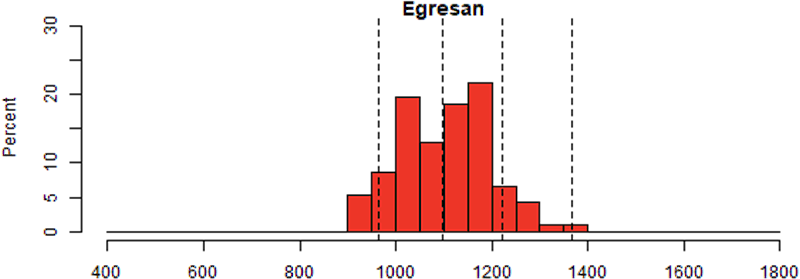

In this institution’s design, which included comparing entering and graduating classes samples for 2018, the mean total score is higher for the graduating class than for the entering class. Standard deviations (SD) are very close in value, indicating a similar spread of scores in both classes. The effect size (ES) value shows that, as expected, the graduating class performed better than the entering group.

In the Performance Task (PT) scores, both the entering and graduating classes mean scores are higher than their total scores. The graduating class mean PT score is higher than that of the entering class and their SD values are identical. There is a positive ES, very close to that of the total score, and a reduced effect of the university curriculum in this type of Critical Thinking skill may be concluded. For the Structured Response (SR) scores, the graduating class has a higher mean score than mean scores in both the total and the Performance Task and the SD is lower than that of the entering class. The ES in this case is lower than that of the total. The mean performance level of both classes is Basic.

Table 15.9. Scores in CLA+ at University W, by class

|

Class 2018 |

N |

Mean Score |

Standard Deviation |

25th Percentile Score |

75th Percentile Score |

Percentile Rank Mean Score |

Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Entering PT |

288 |

1 100 |

174 |

1 001 |

1 226 |

76 |

|

|

Entering SR |

288 |

1 049 |

170 |

921 |

1 172 |

54 |

|

|

Entering Total |

288 |

1 074 |

136 |

982 |

1 176 |

68 |

|

|

Graduating PT |

274 |

1 121 |

174 |

1 046 |

1 226 |

51 |

0.12 |

|

Graduating SR |

274 |

1 055 |

164 |

930 |

1 711 |

10 |

0.04 |

|

Graduating Total |

274 |

1 092 |

135 |

991 |

1 187 |

26 |

0.13 |

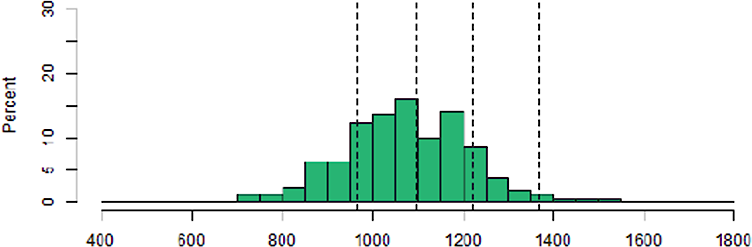

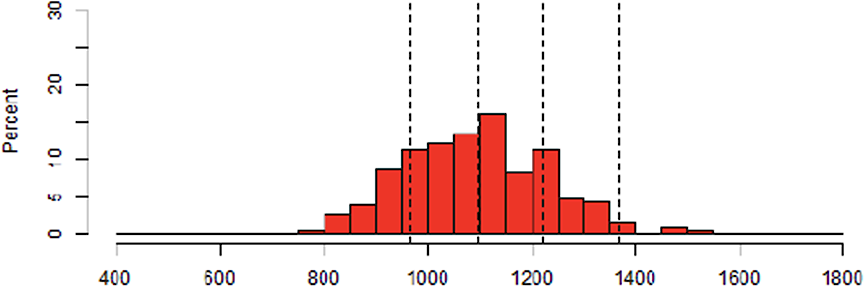

Performance levels percentages of the entering class show a right skew and a more normal distribution appears for the graduating class with bimodal values. Furthermore, only for the graduating class do a few Advanced level cases exist, thus indicating a more scattered general performance.

Figure 15.2. Performance levels percentages at University W, entering class

Figure 15.3. Performance levels percentages at University W, graduating class

University X

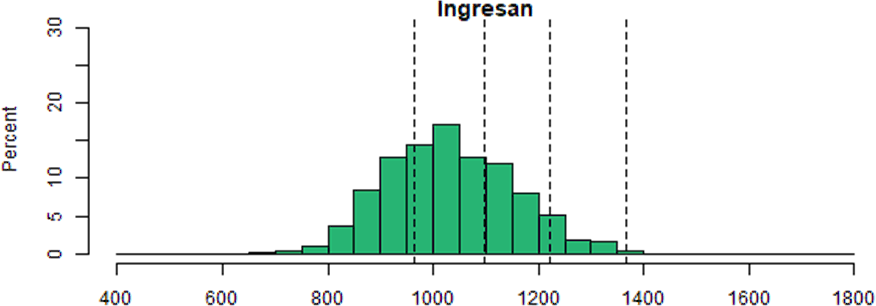

This institution, in 2019, did not complete testing of the graduating class and only completed that of the entering and the third-year classes.

Consequently, smaller differences between classes and values of ES should be expected. Mean total scores in both classes are almost identical and SDs are close. The total score effect size (ES) value is small and negative, thus suggesting a small effect of the new General Studies curriculum. Performance Task (PT) mean scores are higher for the entering class and SDs of both classes are close. ES is negative and half a standard deviation in value. The reason for this absence of learning effect of the new General Studies curriculum could stem from several sources, among those the General Studies’ insufficient achievement effect on the third-year class or a high initial skill level of the entering class. Results for the Structured Response (SR) section look more as expected since the third-year class mean score is higher than that of the entering class. SDs are different and the entering class shows a more heterogeneous performance. The ES is positive and close to 0.4 SD.

Table 15.10. Scores in CLA+ at University X, by class

|

Class |

N |

Mean Score |

Standard Deviation |

25th Percentile Score |

75th Percentile Score |

Percentile Rank Mean Score |

Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Entering 2019 PT |

220 |

1 165 |

116 |

1 091 |

1 286 |

93 |

|

|

Entering 2019 SR |

220 |

1 040 |

153 |

919 |

1 137 |

53 |

|

|

Entering 2019 Total |

220 |

1 104 |

101 |

1 033 |

1 170 |

78 |

|

|

Third Year |

|||||||

|

2019 PT |

108 |

1 105 |

110 |

1 012 |

1 181 |

38 |

-0.52 |

|

Third Year 2019 SR |

108 |

1 099 |

140 |

993 |

1 201 |

26 |

0.39 |

The mean performance level for both classes in this institution is Proficient. The performance level percentage distribution for both the entering and third-year classes show a right skew. The third-year class distribution is bimodal and both classes have close mode values, the entering class distribution having a few Advanced level outliers.

Figure 15.4. Performance levels percentages at University X, entering class

Figure 15.5. Performance levels percentages at University X, third-year class

University Y

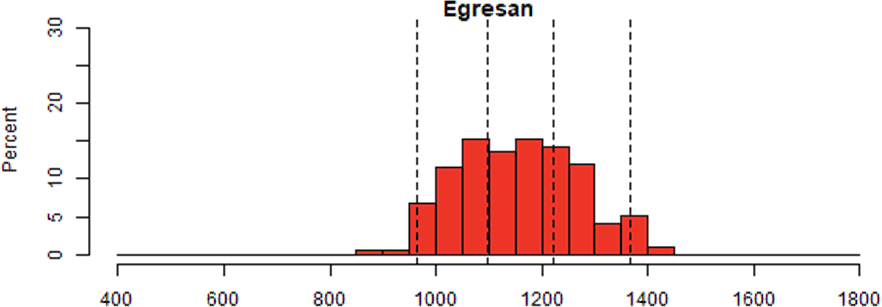

At University Y, both 2020 entering and graduating classes were tested online. As Table 15.11 shows, total mean scores have a substantial difference in favour of the graduating group with over a 1.0 standard deviation ES, thus suggesting higher and more homogeneous performance in the General Studies achievement of the graduating class. For both classes, the SD value and the spread are close.

As for the total score, a positive difference in favour of the graduating class is shown in Table 15.11 for the Performance Task (PT) results as well as over a 1 SD effect size value. In this case, the spread for both groups is also fairly close. All this may be explained by the acquisition of higher-level competencies by the graduating class subjects during their education at University Y. For the Structured Response (SR) scores, a positive, although lower, difference in favour of the graduating class is found as compared to the total and Performance Task scores as well as a positive and lesser value of ES, somewhat over 0.6 SD, is observed. These results can be interpreted as confirming conclusions derived from the previously analysed scores. Spread remains very similar for both classes.

Table 15.11. Scores in CLA+ at University Y, by class

|

Class |

N |

Mean Score |

Standard Deviation |

25th Percentile Score |

75th Percentile Score |

Percentile Rank Mean Score |

Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Entering 2020 PT |

662 |

1 004 |

131 |

911 |

1 091 |

37 |

|

|

Entering 2020 SR |

662 |

1 060 |

168 |

935 |

1 171 |

58 |

|

|

Entering |

|||||||

|

2020 Total |

662 |

1 033 |

121 |

942 |

1 114 |

49 |

|

|

Graduating 2020 PT |

220 |

1 144 |

135 |

1 046 |

1 226 |

65 |

1.07 |

|

Graduating 2020 SR |

220 |

1 165 |

163 |

1 046 |

1 288 |

64 |

0.63 |

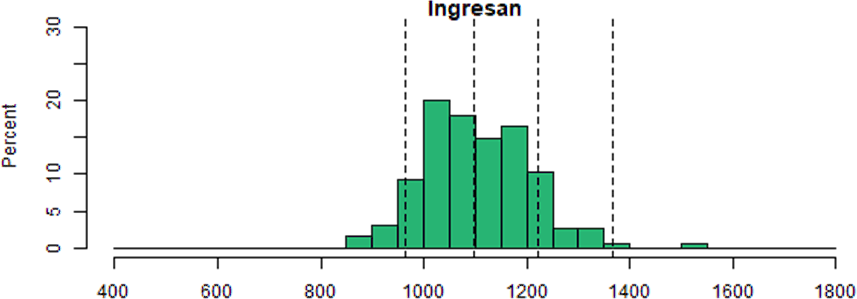

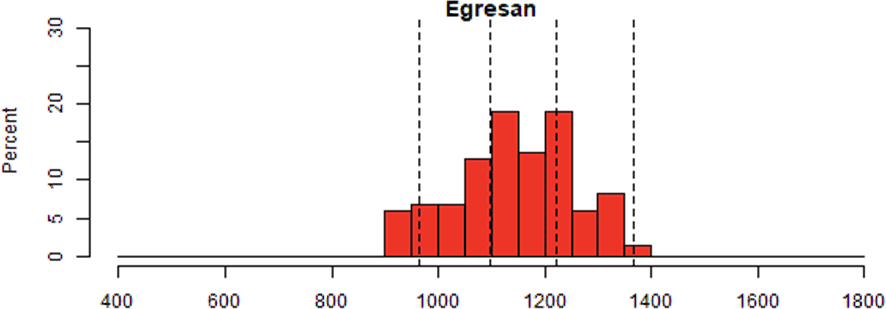

At University Y the general performance level for the entering class is Basic and Proficient for the graduating group. For the performance levels percentage distribution of the entering class, a right skew, a higher mode value, and a few Advanced Level cases as well, are observed. For the graduating class, the distribution shape is closer to normalcy with a lower mode and more abundant Advanced level percentage cases. All these features concur with earlier comments about University Y results.

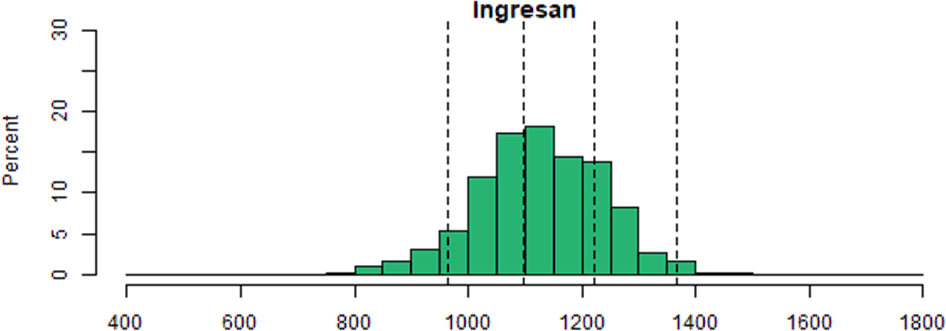

Figure 15.6. Performance levels percentages at University Y, entering class

Figure 15.7. Performance levels percentages at University Y, graduating class

University Z

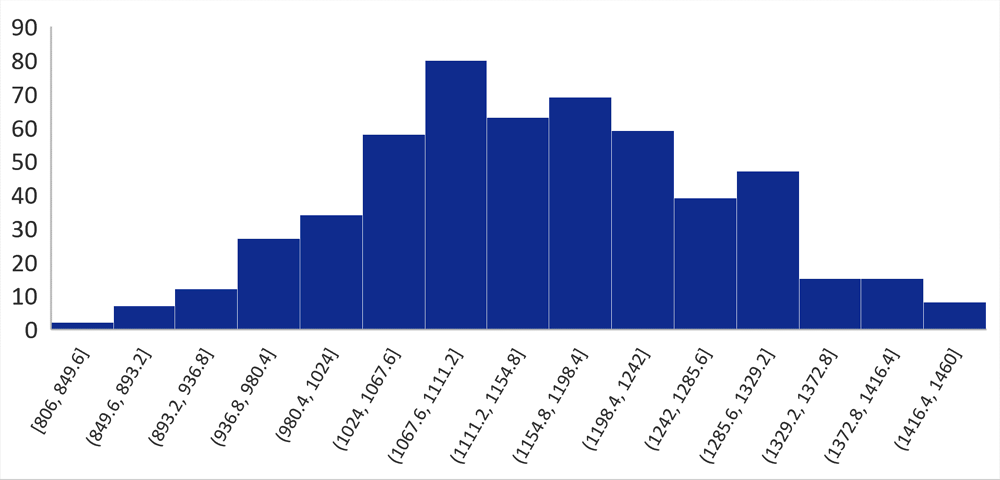

University Z held testing in two windows. The first one was between August and December 2019, using the on-site mode and university computers, and the second from August to December 2020 using an online proctored protocol and students’ equipment due to pandemic constraints. Since the 2019 graduating class could not be tested due to social unrest in the country, available results for that year correspond only to the entering class. In 2020, both classes were examined and ES was calculated. In 2019 the mean score of the Performance Task is higher than the total and the Selected Response scores, thus suggesting that the entering class had a better initial status in the connected higher mental processes with that task.

Table 15.12. Scores in CLA+ at University Z, entering class 2019

|

Scores |

N |

Mean |

Standard Deviation |

25th Percentile |

75th Percentile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Performance Task |

567 |

1 171 |

145 |

1 091 |

1 271 |

|

Selected Response |

567 |

1 122 |

178 |

983 |

1 245 |

|

Total |

567 |

1 145 |

124 |

1 065 |

1 237 |

The performance level counts show a right skew with a median close to 1 110 score points and very few cases in the Advanced level (beyond 1 400 score points) area.

Figure 15.8. Performance levels subject count at University Z, entering class 2019

In 2020 total scores show a higher mean value for the graduating class and close variance values. A small positive ES also appears, thus indicating a somehow stronger Critical Thinking entering class. The Performance Task mean scores show even a smaller difference between classes than the total mean scores as well as a very low ES, thus suggesting a slightly better performing entering class in the tested construct. The Selected Response mean score shows higher figures although similar low differences as the previous mean scores and the ES as well.

Table 15.13. Scores in CLA+ at University Z, by class

|

Class |

N |

Mean Score |

Standard Deviation |

25th Percentile Score |

75th Percentile Score |

Percentile Rank Mean Score |

Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Entering PT |

623 |

1 094 |

107 |

1 046 |

1 136 |

75 |

|

|

Entering SR |

623 |

1 154 |

171 |

1 041 |

1 273 |

92 |

|

|

Entering Total |

623 |

1 127 |

111 |

1 053 |

1 206 |

86 |

|

|

Graduating PT |

151 |

1 103 |

121 |

1 046 |

1 181 |

38 |

0.08 |

|

Graduating SR |

151 |

1 178 |

171 |

1 061 |

1 302 |

73 |

0.14 |

|

Graduating Total |

151 |

1 146 |

109 |

1 076 |

1 221 |

57 |

0.17 |

For this university, the general performance level is Proficient for both classes. Both performance levels percentage distributions approach normalcy, with few extreme cases at both ends and the graduating class is bimodal.

Figure 15.9. Performance levels percentages at University Z, 2020, entering class

Figure 15.10. Performance levels percentages at University Z, 2020, graduating class

Policy implications and lessons learnt

Despite the case-study origin of the available evidence, a prudent and general implication is the increasing importance assigned to Critical Thinking as part of the General Studies curriculum in Chilean higher education. Among the four institutions reviewed, two of them, Y and Z, included results for General Studies student achievement data as evidence to be submitted to foreign (U.S.) and Chilean institutional accreditation bodies as one of the policy reasons for participating in the study.

A related aspect is that all Chilean universities involved consider General Studies as part of the curricular changes they recently implemented. In two of the cases, this affects their educational model and required hard evidence of student performance for ongoing adjustments of those new policies.

A third policy issue is a greater awareness in the country of the need for integrating assessment actions into higher education. In three of the Chilean institutions, W, X, and Z, diagnostic information was sought from the study results, and in all four of them, the study data was used for formative purposes, either at the student or system level.

Lastly, acquaintance with and a drive to use assessment instruments of high technical quality are becoming the rule in Chilean higher education institutions. In this sense, standardised testing is recovering its prestige mainly by using performance tasks and improved selected response items such as in CLA+ that allow for valid, reliable, and comparable assessments of higher mental processes.

Some of the lessons learnt deal with the outreach process. The direct outreach approach proved to be valid as governmental authorities acknowledged that they could not validly approach universities on academic issues. As well, participating universities reacted positively to being contacted directly. It is, however, worth considering contacting higher academic education organisations as they can contribute to assessment credibility and allow for a more efficient and collective outreach to universities and other higher education institutions.

Another aspect is the length of the decision process in joining the study

Participating in a joint assessment venture requires careful thought not only financially but in terms of institutional image as well. Nevertheless, this makes the whole process long and sometimes cumbersome. Consequently, the assessment provider must use experience and provide clear-cut and timely information.

Due to the absence of in-house technical assessment capacity in most universities in the region, sample structure and comparison design are two issues demanding close and expert support from the provider. Scientific-based help in these matters is essential.

As this is an international study, thus involving different countries, languages, and cultures, the participation of a locally positioned member of the study staff is very important. Although language is a primary concern, in most cases there is also a need to familiarise institutions with the ways and means of up-to-date assessment and to adapt the relationship to local procedures.

Verification of technical computer and communication issues by the provider using permanent support and supervision and trial runs is very important, particularly under prevailing pandemic conditions requiring the use of secure platforms and proctoring. In this same respect, the online mode confronts students with technological demands that some of them are not able to comply with. The rise in the number of young people from lower-income echelons having access to higher education in Chile and the region has meant that many students cannot cope with online proctored application requirements because they lack access to adequate equipment, software or connections.

Next steps and prospects

Contacts established with institutions in Chile and the rest of the region reveal a generalised awareness of the General Studies component in higher education curricula critically affecting graduates’ ability to perform in an information society. This triggers the need to ensure that those competencies are attained by students, and that reliable and credible evidence about it is generated for certification purposes for graduates, employers, and institutional and governmental authorities.

There is also a growing tendency for higher education accrediting entities to demand hard evidence from academic institutions about the added value they contribute to their students, particularly on the so-called "fundamental competencies" included in the Critical Thinking construct assessed by CLA+.

Consequently, the initial assessment trend developed for some Chilean universities with CLA+ requires expansion to the rest of the region’s higher education institutions. Three out of the four Chilean institutions whose participation was analysed here have already planned and subscribed agreements with CAE for subsequent participation. Unfortunately, hurdles – some, hopefully, transitory – are presently hampering this extension to other entities.

Notwithstanding, even if elements such as the pandemic are, we hope, transitory, some of its effects are here to stay, such as the growth of remote teaching, learning modes and, foremost, assessment modes. Most likely, education will never be the same as before COVID-19 and assessment systems such as CLA+ will have to consider relying substantially on fully remote modes of application.

Another hurdle affecting regional expansion in Latin America is the lack of funding. Although CLA+ has a comparatively moderate cost, several institutions are willing to participate but cannot pay for its application. Consequently, there is a need for motivating national, regional and global funding entities to contribute resources either to CAE to generate programmes in Latin America or directly to higher education institutions in the region so that they can take advantage of this unique assessment opportunity.

In the psychometrics aspect, the CLA+ diversity of item types could be supplemented with other forms of questions. At present, this is the single available battery able to validly assess competencies that include higher mental processes. Another aspect to improve stems from the very essence of the competency approach which considers three components: cognitive, performative, and affective. Today’s CLA+ battery includes the first two Critical Thinking competencies. The third, which is the affective realm, is still to be developed and included in the battery. This realm should consider testing some of the soft skills related to the main Critical Thinking construct.

References

[7] CNED (2020), Informe Tendencias de Estadísticas de Educación Superior por Sexo, CNED, Santiago, https://www.cned.cl/sites/default/files/2020_informe_matricula_por_sexo_0.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2021).

[6] OECD (2017), Education in Chile, Reviews of National Policies for Education, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264284425-en.

[4] OECD/The World Bank (2009), Reviews of National Policies for Education: Tertiary Education in Chile 2009, Reviews of National Policies for Education, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264051386-en.

[1] OEI (2018), Panorama de la Educación Superior en Iberoamérica a través de los indicadores de la Red Indices, OEI, Buenos Aires, https://oei.org.uy/uploads/files/news/Oei/191/panorama-de-la-educacion-superior-iberoamericana-version-octubre-2018.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2021).

[3] OEI-Observatorio CTS (2021), Papeles del Observatorio Nº 20, Abril 2021: Panorama de la Educación Superior en Iberoamerica a través de los indicadores de la Red Indices, OEI, Buenos Aires, http://www.redindices.org/novedades/139-papeles-del-observatorio-n-20-panorama-de-la-educacion-superior-en-iberoamerica-a-traves-de-los-indicadores-de-la-red-indices (accessed on 28 April 2021).

[5] Servicio de Información de Educación Superior SIES (2020), “Informe matrícula 2020 en educación superior en Chile”, Servicio de Información de Educación Superior.

[2] Trow, M. (2008), “Reflections on the Transition from Elite to Mass to Universal Access: Forms and Phases of Higher Education in Modern Societies since WWII”, in International Handbook of Higher Education, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-4012-2_13.