While no universal definition of environmental justice exists, it seeks to redress an array of recurring challenges faced by various communities and groups. This chapter introduces these underlying environmental justice challenges which include disproportionate exposure to environmental hazards and the subsequent adverse health effects resulting from such exposure, unequal access to environmental amenities, and concerns about the distributional implications of environmental policies. These concerns can be further exacerbated by the lack of meaningful engagement and legal recourse for the affected communities. This chapter introduces the building blocks of the OECD Environmental Justice Survey, which sought to identify similarities and differences in how countries identify, assess and address environmental justice concerns.

Environmental Justice

1. Introduction and overview

Copy link to 1. Introduction and overviewAbstract

1.1. Introduction

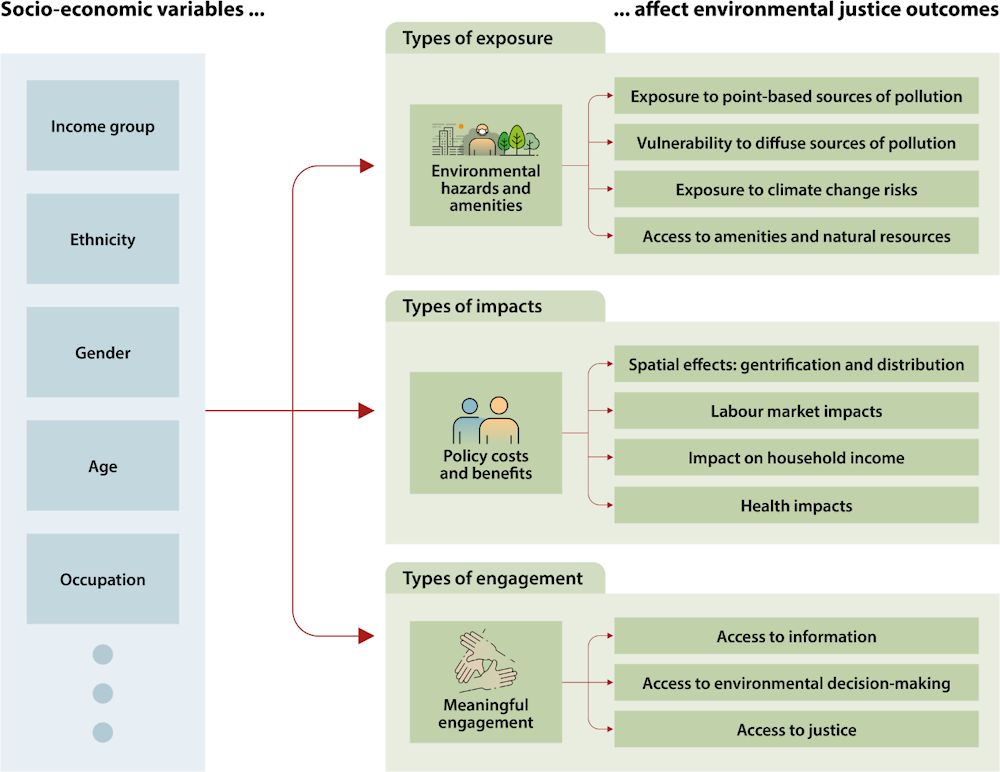

Copy link to 1.1. IntroductionThere is mounting evidence that, depending on social and economic circumstances, some communities and groups may face disproportionate exposure to environmental hazards, bear an inequitable share of the costs associated with environmental policy and face more barriers to participating in environmental decision-making world (see, for example (Walker, 2012[1]; Mitchell, 2019[2]; Mabon, 2020[3])). The existing literature highlights the links between such disparities and a matrix of demographic and socio-economic variables (Figure 1.1). Environmental justice is about recognising and addressing these issues.

Figure 1.1. Environmental justice: Dimensions and relevant factors

Copy link to Figure 1.1. Environmental justice: Dimensions and relevant factors

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

An environmental justice lens highlights the linkages between environmental and social conditions. It sheds light on how different levels of environmental quality and protection contribute to the health and wellbeing of some groups, while harming the welfare of others. It also highlights how the environmental goods enjoyed by some groups may come at the expense of those enjoyed by others. Finally, it explores how the ability to influence political change and related decision-making processes varies across groups and communities.

While much of the focus of the literature and policy action is on specific local and national contexts, given the commonality of many of these challenges, an assessment of how environmental justice is advanced in different countries can yield valuable insights and facilitate mutual learning. It is in this context that the OECD has undertaken a cross-country analysis to explore governments approaches to environmental justice. This report aims to shed light on how governments across the OECD and beyond are identifying, analysing, and addressing environmental justice concerns. A survey was distributed to the relevant ministries and agencies of OECD member countries, the European Commission and several non-member countries.1 Insights from the Survey were complemented by desk research as well as consultations with experts and practitioners.

1.2. About the OECD Environmental Justice Survey

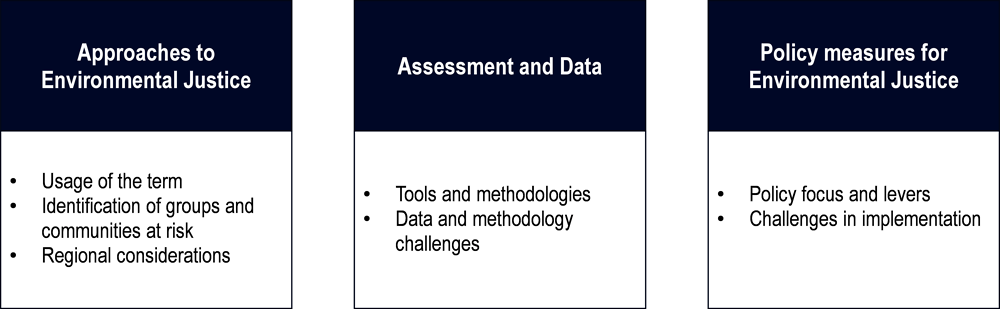

Copy link to 1.2. About the OECD Environmental Justice SurveyThe OECD Environmental Justice Survey is exploratory in its aim, seeking to identify the similarities and differences between the approaches to environmental justice across countries. The survey consisted of 20 questions on three key themes: (i) approaches to environmental justice, (ii) assessments and data, (iii) policy measures for environmental justice (Figure 1.2 and Annex A). The first section of the survey explored the approaches countries take to consider environmental justice. Environmental justice was not explicitly defined in the Survey to better explore how the concept is defined and applied in different countries. Instead, the three guiding facets of environmental justice identified (inequitable exposure to environmental hazards and access to environmental amenities, inequitable distribution of the costs and benefits of environmental policy and barriers to access to environmental information, participation in decision-making and legal recourse) were presented to help structure the responses. The section also prompted countries to share what characteristics they consider as relevant when identifying groups and communities at risk. The second section explored the tools and methodologies countries adopt to assess environmental justice concerns. The last section of the survey explored how countries address environmental justice concerns through policies and key challenges they face in their implementation.

Figure 1.2. Overview of the Survey

Copy link to Figure 1.2. Overview of the Survey

Source: The OECD Environmental Justice Survey

Given the cross-cutting nature of environmental justice issues which may not neatly map onto the remit of ministries and agencies, the Survey encouraged co-ordinated national response to the extent possible. In total, 25 countries (Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Croatia, Estonia, France, Germany, Japan, South Korea, Lithuania, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Slovak Republic, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Türkiye, United Kingdom (where separate responses were received from England and Scotland) and United States) and the European Commission provided response to the Survey. While Environment Ministries were the respondent in the majority of the cases, the responses from some countries were received from multiple ministries and agencies.2 In the case of the United Kingdom, separate responses were submitted for England and Scotland because the constitutional arrangement of the United Kingdom provides that various environmental powers are devolved to the individual national administrations. However, Northern Ireland and Wales did not respond to the survey. The response from the European Commission represents a regional, rather than a national, approach to environmental justice.3

Finally, complementary desk research was also conducted, including for countries like Brazil that have initiatives on environmental justice, but where the survey response was not available. Examples sourced from desk research are therefore marked as such.

1.3. Structure of the Report

Copy link to 1.3. Structure of the ReportThe remainder of this report is organised as follows. Chapter 2 provides a primer on the diverse ideas environmental justice articulates. It provides an historical account across regions to illustrate the variability of the concept, but also highlights that there are unifying elements and substantive issues that can be usefully studied across different countries to inform policy development. The subsequent two chapters present the main findings from the Survey. Chapter 3 explores the approaches countries take at the national level to consider environmental justice in policymaking. Chapter 4 then turns to how countries identify, assess, and address environmental justice concerns.

References

[3] Mabon, L. (2020), “Making climate information services accessible to communities: What can we learn from environmental risk communication research?”, Urban Climate, Vol. 31, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2019.100537.

[2] Mitchell, G. (2019), “The messy challenge of environmental justice in the UK: evolution, status and prospects”, Natural England Commissioned Report NECR273, https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/148740/1/2019%20Mitchell%20NE%20EJ%20commissioned%20report%20NECR273.pdf.

[1] Walker, G. (2012), Environmental Justice: Concepts, Evidence and Politics, Routledge, London, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203610671.

Notes

Copy link to Notes← 1. The survey was sent out to the following countries (countries which provided the response are marked with a *): Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada*, Chile*, Colombia*, Costa Rica*, Croatia*, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia*, Finland, France*, Germany*, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Indonesia, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan*, Korea*, Latvia, Lithuania*, Luxembourg, Mexico*, the Netherlands, New Zealand*, Norway, Peru*, Poland*, Portugal*, Slovak Republic*, Slovenia, South Africa*, Spain*, Sweden*, Switzerland*, Türkiye*, the United Kingdom* and the United States*.

← 2. The response from New Zealand was received from Ministry for the Environment and Ministry of Health. The response from Peru was received from a total of 11 Ministries, departments and authorities. The responses from the Directorates under the Ministry of Environment were prioritised for analysis, but the content of this report draws on all responses. The response from Türkiye was received from the government department for which environmental issues typically fall outside of their main remit, namely Small and Medium Enterprises Development Organization.

← 3. The response highlighted just transition as the central theme informing policymaking. Details of the response from the European Commission are therefore discussed in areas where just transition and environmental justice concerns may overlap.