This chapter provides a high-level overview of national approaches to environmental justice based on an analysis of the responses to the OECD Environmental Justice Survey. The chapter reports on which countries use the term environmental justice. It next examines the channels through which environmental justice is pursued, such as the legal approaches, government policies, or regulatory initiatives, as well as the level of detail in which its substantive aspects are considered in the survey responses. Finally, the chapter offers illustrative examples of approaches from around the world.

Environmental Justice

3. National approaches to environmental justice in practice

Copy link to 3. National approaches to environmental justice in practiceAbstract

3.1. Use of the term environmental justice

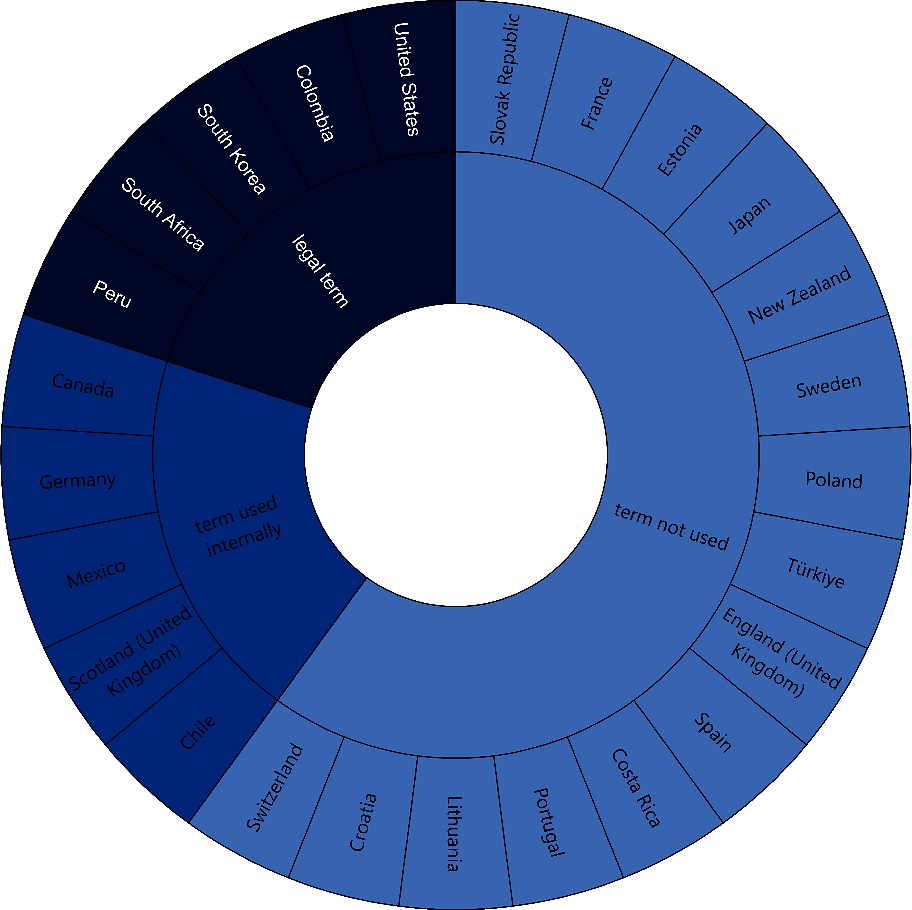

Copy link to 3.1. Use of the term environmental justiceWhile the underlying concerns might be broad-based, the use of the term “environmental justice” is not common among national administrations (Figure 3.1). Ten of the 25 countries used the term environmental justice; of these, four used the term internally (Chile, Germany, Mexico, Scotland), four considered environmental justice in pre-existing legislation (South Africa, South Korea,Peru, United States), one had a definition derived from the judiciary (Colombia), and another had an environmental justice bill pending enactment (Canada).

The fact that less than half of national administrations surveyed use the term may reflect their varied approaches to tackling environmental inequities. Some countries use other terms that relate to the conceptual pillars of environmental justice (distributive, procedural and recognitional justice) without explicitly using the term. In a similar vein, in addition to environmental justice, Canada also uses the term “environmental racism” reflecting the usage of the term in racial equality movements. Other countries use more descriptive phrases, for example, “environmental inequalities” in the case of France. To varying extents, these terms reflect the focus of advancing environmental justice in these countries.

Figure 3.1. Use of the term environmental justice at the national level

Copy link to Figure 3.1. Use of the term environmental justice at the national level

Note: Authors’ review of the responses to the survey informed this classification.

Source: The OECD Environmental Justice Survey.

3.2. Different channels through which environmental justice is considered

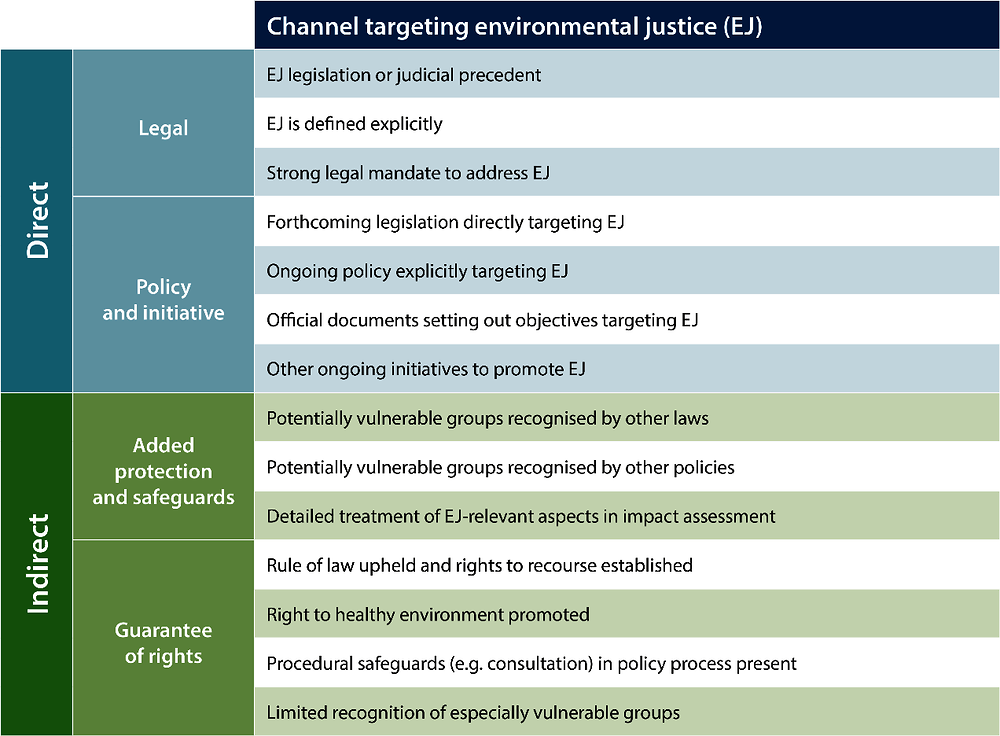

Copy link to 3.2. Different channels through which environmental justice is consideredBuilding upon the finding on the usage of the term, two categories of approaches to environmental justice were identified: direct approaches (those countries who use the term, and have specific measures to target environmental justice), and indirect approaches (those countries who do not use the term but address environmental justice in other ways, i.e., indirectly). Within the direct category, the survey identified two channels through which environmental justice is pursued: (i) legal, and (ii) policy and initiative. Likewise, within the indirect category, two channels through which environmental justice is pursued were identified: (i) added protection and safeguards, and (ii) guarantee of rights.

Environmental justice can be pursued through all these channels individually, or cumulatively; they are not necessarily mutually exclusive. For example, the United States guarantees constitutional and civil rights but also has environmental justice policies and Executive Branch directives to specifically address environmental justice through a series of executive orders. Likewise, in South Africa, environmental justice emerged as a policy principle, advancement of which became legally mandated through a legislation. Similarly, while Canada has an ongoing government initiative through their draft environmental justice legislation, rights relevant to environmental justice are still protected to some extent by guaranteeing rights; for instance, the right to a healthy environment contained within the Environmental Protection Act.

Direct approaches can be thought of as being more targeted than indirect approaches because they have a specific mandate for pursuing environmental justice (Figure 3.2). Under direct approaches, legal measures can be seen as a firmer commitment to environmental justice than statements of policy because they are less prone to change with government priorities, and they can establish enforceable rights and duties.

Figure 3.2. Direct and indirect approaches to environmental justice and their channels

Copy link to Figure 3.2. Direct and indirect approaches to environmental justice and their channels

Note: Authors’ review of the responses to the survey informed this classification. The channels identified are not exhaustive and discreet.

Source: The OECD Environmental Justice Survey.

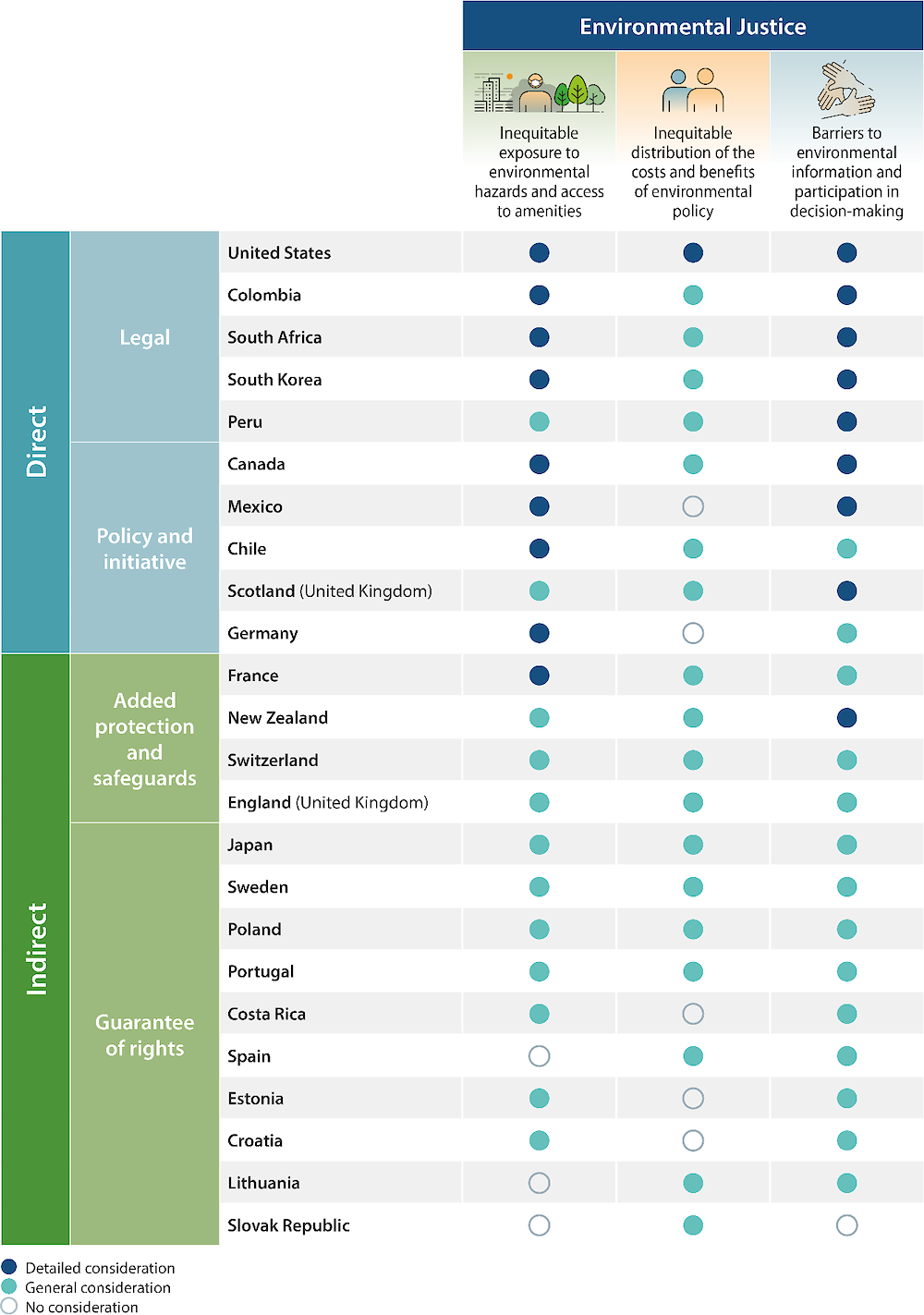

The analysis also looked at whether the substantive concerns addressed within environmental justice identified in Chapter 21 are considered and at what level of detail (Figure 3.3). As this characterisation entails a degree of judgement, the level of detail in which an aspect of environmental justice was considered in a survey response was assessed against pre-defined criteria. Specifically, “detailed” consideration requires that the response was explicitly focused, extensively described, or addressed differentiated impacts across the issues among other factors. Unless the response to the Survey described how it overlapped with environmental justice concerns, approaches that relate exclusively to climate policies and strategies for just transition2 were characterised as “general”. While recognising the complementarity of these concepts (see Section 2.3.4 in Chapter 2), the analysis focussed on identifying explicit references to environmental justice, due to its comprehensive perspective and limited consideration in policy to date.

Overlaying this detail-based categorisation upon the direct and indirect approaches reveals that all countries surveyed address – directly or indirectly – environmental justice concerns, albeit to varying extents. However, the analysis finds that countries which deploy direct approaches consider the substantive environmental justice concerns and do so in greater detail. Countries which deploy indirect approaches tend to consider environmental justice concerns more generally, through less targeted measures.

Figure 3.3. Consideration of environmental justice concerns by approaches and by country

Copy link to Figure 3.3. Consideration of environmental justice concerns by approaches and by country

Note: The level of details considered is categorised by authors based on the review of survey responses. Türkiye and the European Commission were not classified as their responses considered more sectoral issues which hindered the assessment of their coverage of the three substantive environmental justice concerns.

Source: The OECD Environmental Justice Survey.

This finding may reflect the competing advantages and disadvantages of different channels for pursuing environmental justice, along with the varying salience of different environmental justice concerns across countries. All approaches to environmental justice have their relative advantages and disadvantages. Guaranteeing rights plays a role in promoting environmental justice. Additionally, poor environmental quality can negatively impact an array of rights; such as to health, or adequate living standards. More practically, enforcement mechanisms for such rights – embodied in legal systems – provide routes to recourse for the victims of environmental injustice (Lewis, 2012[1]).3

However, one limitation of rights-based approaches is that mandating equal rights does not necessarily recognise ex ante that some groups are more vulnerable to poor environmental quality and that such groups may also face barriers to accessing legal recourse. Added protection and safeguards might enable corrective measures to address these inequities. Yet, such approaches, in some instances, can still be reactionary which may limit their effectiveness of identifying less well recognised vulnerabilities in favour of the most high-profile issues in a given context.

Accordingly, environmental justice policies explicitly targeting or taking into account vulnerable groups may be preferable in recognition of these potential problems. However, while policies and initiatives play an important role in influencing environmental justice outcomes, they are typically held to a lower standard of accountability than laws which create binding obligations upon specific actors alongside enforcement mechanisms (United Nations Development Programme, 2022[2]). Consequently, legal protections and requirements that go beyond purely rights-based approaches may be appropriate in some cases.

3.3. Examples of direct approaches across countries

Copy link to 3.3. Examples of direct approaches across countries3.3.1. Legal approaches to environmental justice

Copy link to 3.3.1. Legal approaches to environmental justiceUniquely, the United States has strengthened its agenda on environmental justice through a series of executive orders.4 A 2023 Executive Order5 defines environmental justice as: “the just treatment and meaningful involvement of all people, regardless of income, race, colour, national origin, Tribal affiliation, or disability, in agency decision-making and other Federal activities that affect human health and the environment” (White House, 2023[3]) (see Box 3.1 for the full definition). The United States’ definition reflects the three aspects of environmental justice discussed in Chapter 2, and Executive Orders 12898 and 14096 provide clear directives for federal agencies to advance environmental justice. For instance, a 1994 Executive Order6 directed federal agencies to: ‘‘identify and address the disproportionately high and adverse human health or environmental effects of their actions on minority and low-income populations, to the greatest extent practicable and permitted by law’’ and mandated developing a strategy for implementing environmental justice (United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2023[4]). This study also finds that the United States is the only country to provide a detailed consideration of the distributive effects of environmental policies.

In Colombia, the Constitutional Court has opined that environmental justice is composed of four elements found in the 1991 constitution, which have also been complied in constitutional jurisprudence with reference to the definition developed by the US EPA. 7 In a ruling, both participatory and distributive dimensions of environmental justice were acknowledged. The case concerned the environmental degradation suffered by the Indigenous communities of the Zenú People because of the construction of the Cantagallo landfill near their residence. The court found that the defendants – which were national and local environmental authorities, a public utility company, and the Colombian Ministry of Interior – had violated various rights of the plaintiffs. For instance, these violations included right to prior consultation of those affected as part of the permitting process, as well as recognition of the plaintiffs Indigeneity by non-acceptance of their presence in the area where the landfill was built. Additionally, in a 2019 ruling concerning the failure to consult a predominantly Black community in Playa Blanca about removal of marine access rights to a vital area,8 the Colombian constitutional court grounded its definition of environmental justice in principles established within its constitutional jurisprudence such as sustainability and the precautionary principle.

Colombia’s survey response indicates that it considers the inequitable distribution of environmental harms and benefits as well as participation and engagement in detail. For example, Colombia cited various measures that facilitate public participation such as a decree9 of the Colombian government “to adopt the Public Policy on Citizen Participation […]”, and their “National Development Plan” which aims to create an “Escazú Inter-institutional Commission” to strengthen environmental safeguards. Colombia’s response also confirmed that the right to prior consultation is understood as a protection of environmental justice for Indigenous or Tribal Peoples (Gobierno de Colombia, 2023[5]). Regarding the distributional impact of environmental policies, while the principle of “distributive justice” was mentioned, there was no substantive consideration beyond highlighting its importance. This may reflect the fact that the development of environmental justice was driven by the judiciary in Colombia. 10

South Africa’s approach to environmental justice is rooted in the Bill of Rights contained in the post-apartheid Constitution of 1996 (Government of South Africa, 1996[6]). The concept of environmental justice was first specifically defined in the principles of the 1998 National Environmental Policy White Paper, which makes it a responsibility for the government to “integrate environmental considerations with social, political and economic justice and development in addressing the needs and rights of all communities, sectors and individuals” to redress environmental injustices, both past and present (Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment, 1998[7]). The principle of environmental justice was further mandated by the National Environmental Management Act (NEMA) (Government of South Africa, 1998[8]).

Notably, the right to participation in environmental decision-making is also operationalised in NEMA section 2.4(f), which recognises that people must have “the opportunity to develop the understanding, skills and capacity necessary for achieving equitable and effective participation” (ibid). Building on this legislation, the judiciary in South Africa has also played an active role in the development of jurisprudence on what constitutes meaningful public participation (Hall and Lukey, 2023[9]). For instance, in a case concerning the exploration right for oil and gas,11 the Court declared that some of the procedural aspects of the public consultation, including the notice published only in Afrikaans and English12 and the location of public meetings far from the affected communities, were flawed.

In South Korea, environmental justice finds its concrete expression in the Article 2 of the Framework Act on Environmental Policy. A number of plans ensued to operationalise the concept in policymaking, with the “Comprehensive Plan for National Environment 2020-2040” aiming to develop a framework for promoting environmental justice and conduct an evaluative work on the current situation by 2030 (Ministry of Environment, 2019[10]) and Comprehensive Environmental Justice Plan (2020-2024) outlining the implementation. Specific communities and groups at risk of environmental justice concerns are also identified in the Environmental Health Act, such as those residing near industrial complexes and in densely populated areas, as well as those particularly susceptible to exposure to environmental hazards, including children and pregnant women (Korea Legislation Research Institute, 2008[11]).

The Peruvian approach to environmental justice is premised on its procedural aspects, access to legal recourse in particular, with Article IV (right of access to environmental justice) of the General Environmental Law highlighting the right to quick, simple and effective action before the administrative and jurisdictional entities as well as due protection of people’s health.13 Another noteworthy aspect of the Law is the equity principle, stipulating the requirement for environmental policies to contribute to “eradicating poverty and reducing the prevailing social and economic inequities, as well as to the sustainable economic development of the disadvantaged populations” (Ministry of Environment of Peru, 2005[12]). Furthermore, in addition to consideration for vulnerable groups such as Indigenous Peoples, particular emphasis is placed on the protection of environmental defenders through the Sectoral Protocol for the Protection of Environmental Defenders which aims to guarantee their rights and establishes a range of preventive and protective measures (Ministry of Environment of Peru, 2021[13]).

These five cases demonstrate that environmental justice can be advanced through all three branches of government. Just as the United States shows the executive branch of government can play an important role in driving environmental justice forward, Colombia and South Africa exemplify that the judiciary can also be a key lever. Moreover, a crucial aspect of both the Colombian cases cited above was recognition of the right of Indigenous Peoples to free, prior and informed consultation, which could have future implications for a broader public participation in environmental decision-making. This may reflect that Colombia is a signatory14 to the Escazú Agreement which highlights the role of international instruments in establishing the rights which are foundational to environmental justice.

Finally, the examples of South Africa, South Korea and Peru highlight the role of legislatures, which solidify environmental protection by creating legal standards which identify citizens’ rights and the actors responsible for upholding them (UNDP, 2022[14]). Instead of having one dedicated environmental justice law, the principle of environmental justice is operationalised in varied broader environmental legislation which provide a legal basis for addressing the issues through implementation of policy and jurisprudence. For instance, in the case of South Korea, the legal basis founded in the Framework Act on Environmental Policy prompted the development of the Comprehensive Environmental Justice Plan 2020-2024.

Reflecting the locally specific concerns, these acts of legislation place varying weight on the aspects of environmental justice. While in South Africa, the emergence of environmental justice coincided with a wave of democratic change and the need to redress the historical legacy of racism and apartheid, in South Korea the process was motivated by the industrial pollution and its health impact during the period of rapid yet regionally uneven economic growth (OECD, 2017[15]). Peru’s emphasis on procedural aspects of environmental justice, seems to reflect the increasing awareness of the need to protect environmental defenders for whom their activism can constitute a threat to their lives (Article 19, 2016[16]).

Box 3.1. Definitions of environmental justice in the United States, Colombia, South Africa, South Korea and Peru

Copy link to Box 3.1. Definitions of environmental justice in the United States, Colombia, South Africa, South Korea and PeruA comparison of definitions across the five countries that deploy legal approaches to advance environmental justice is illustrative of how it is conceptualised in practice. All of the definitions contain the element of distributive environmental justice, while some also highlight procedural and recognitional environmental justice. Peru’s definition, for instance, recognises the right of access to justice to address harm that are moral, rather than economic in nature.

In keeping with the origin of environmental justice, the need for corrective remedies is explicit in the United States (“legacy of racism”) and South Korea (“fair compensation for losses”). Furthermore, while all countries refer to the public in its entirety (“all people”, “all citizens”, “any and every person”), some identify relevant categories, with the United States highlighting “income, race, color, national origin, Tribal affiliation” and Colombia noting “race, colour, national origin, culture, education and income” in particular.

United States and the Executive Order 14096 (2023)

Copy link to United States and the Executive Order 14096 (2023)“the just treatment and meaningful involvement of all people, regardless of income, race, color, national origin, Tribal affiliation, or disability, in agency decision-making and other Federal activities that affect human health and the environment so that people are fully protected from disproportionate and adverse human health and environmental effects (including risks) and hazards, including those related to climate change, the cumulative impacts of environmental and other burdens, and the legacy of racism or other structural or systemic barriers; and have equitable access to a healthy, sustainable, and resilient environment in which to live, play, work, learn, grow, worship, and engage in cultural and subsistence practices.”

Colombia and the judicial rulings (Ruling T-294 of 2014 and Ruling T-021 of 2019)

Copy link to Colombia and the judicial rulings (Ruling T-294 of 2014 and Ruling T-021 of 2019)"the fair treatment and meaningful participation of all people regardless of race, colour, national origin, culture, education or income with respect to the development and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations and policies."

"Environmental justice is composed of four elements found in the 1991 Constitution, which have also been compiled in constitutional jurisprudence, namely: i) distributive justice; ii) participatory justice; iii) the principle of sustainability; and iv) the precautionary principle... environmental justice identifies contexts of inequity in the distribution of environmental benefits and burdens. Together, it shows the way to re-establish the rupture of the just order through the participation of the affected collectives and the configuration of compensation or reparation measures for the ecosystem and/or environmental burdens borne. Such criteria also apply in the implementation of environmental protection measures that entail a disturbance to a vulnerable community".

South Africa and the National Environmental Management Act (1998)

Copy link to South Africa and the National Environmental Management Act (1998)“Environmental justice must be pursued so that adverse environmental impacts shall not be distributed in such a manner as to unfairly discriminate against any person, particularly vulnerable and disadvantaged persons.”

South Korea and the Framework Act on Environmental Policy, Article 2 (amended in 2019)

Copy link to South Korea and the Framework Act on Environmental Policy, Article 2 (amended in 2019)“The State and local governments shall endeavour to realise environmental justice by ensuring all citizens' substantial participation in the enactment or amendment of environmental statutes, regulations, ordinances and rules or the formulation or implementation of policies, access to information about environment, equitable sharing of environmental benefits and burdens, and fair compensation for losses caused by environmental pollution or environmental damage.

Peru and the General Environmental Law, Article 4 (2005)

Copy link to Peru and the General Environmental Law, Article 4 (2005)“Right of access to environmental justice: Every person has the right to a quick, simple and effective action before the administrative and jurisdictional entities, in defence of the environment and its components, ensuring the due protection of the health of people individually and collectively, the conservation of biological diversity, the sustainable use of natural resources, as well as the conservation of the cultural heritage linked to them. Legal actions may be filed even in cases where the economic interest of the plaintiff is not affected. The moral interest legitimizes the action even when it does not directly refer to the plaintiff or his family".

3.3.2. Environmental justice policies and initiatives

Copy link to 3.3.2. Environmental justice policies and initiativesCanada currently has draft legislation15 centred upon environmental justice. Related policy documents identify the importance of procedural, recognitional, and distributive justice. The draft legislation also addresses both inequitable exposure to environmental harms and participation and engagement in detail. Indeed, once developed, Canada’s “Environmental Justice Strategy” aims to address the “link between race, socio-economic status and exposure to environmental risk.” (Prime Minister of Canada, 2021[20]).

Discussion of the distributional impacts of environmental policies was less detailed in Canada’s response. It noted that, policymakers in Canada use a “Gender Based Analysis (GBA) Plus” tool for this purpose which considers the impact of policies upon various geographical, cultural, and socio-economic aspects. The GBA Plus tool is applied generally to all policies and is comparable to impact assessment methodologies deployed in other countries.16 While standardised guidance for assessing the distributive impacts of policies does address their inequitable impacts ex ante, there remains potential for follow-up measures that prevent unforeseen distributional problems ex post and for measures targeted at environmental impacts more specifically.

The German Environment Agency conducts policy research and develops recommendations for policymakers at the federal, state, and municipal levels on methods of enhancing environmental justice in various municipalities. Germany’s Environment Agency defines environmental justice as “reducing and avoiding the socio-spatial concentration of health-related environmental burdens and ensuring fair access to environmental benefits”. This focus is narrower as it does not account for the participation and engagement in environmental policy or for the distributional impacts of environmental policies.17 The German Environment Agency’s approach, however, exemplifies a synergistic application of existing frameworks, such as improving planning and conservation, or engagement to promote environmental justice (Box 3.2).

Box 3.2. German Environment Agency on addressing inequitable exposure to environmental harms in urban areas

Copy link to Box 3.2. German Environment Agency on addressing inequitable exposure to environmental harms in urban areasThe German Environment Agency seeks to address inequitable exposure to environmental harms in an urban context through a holistic use of existing measures such as “[...] urban and neighbourhood development concepts, landscape planning, traffic development planning, participation procedures, neighbourhood management [...]”. Various examples of ways to promote urban environmental justice include:

Noise pollution from traffic: using noise-reducing solutions for road surfaces/landscaped tramlines, installing soundproof windows, introducing speed limits.

Air pollution and urban climate: traffic control measures, increasing green areas to promote cooling.

Indoor air quality: promoting energy efficient retrofitting.

Green transport: increasing the appeal of public transport, cycling, and walking.

Education about the environmental and health: increasing exposure to green spaces, information provision.

This is not to say that environmental justice is necessarily adequately addressed simply by virtue of having a variety of differently targeted environmental policies in isolation from each other. Rather, the German Environment Agency emphasises that the various levers that impact the urban environment should be used synergistically so that the overall effect is greater than the sum of its parts.

The Chilean Office of Just Socio-Ecological Transition defines environmental justice as the “[…] equitable distribution of environmental benefits and burdens in society, especially with regard to ecosystem protection, pollution prevention and mitigation of environmental impacts […]”. Indeed, the Chilean government is acutely aware of the inequitable distribution of environmental harms having acknowledged especially environmentally vulnerable territories, which are Huasco, Quintero-Puchuncaví, and Coronel. These areas are termed “Sacrifice Zones” 18 due to the high levels of localised pollution and environmental hazards produced by industrial facilities.

The Scottish and Mexican governments explicitly use the term environmental justice and rely upon similar, rights-based, definitions. While the former emphasises the negative right to freedom from poor environmental quality, the latter emphasises the positive right to a healthy environment. In Scotland, although no standard definition is used, a recent report on environmental governance refers to environmental justice as follows: “It is important that everyone has the opportunity to enjoy a life free from poor environmental quality. It is also important that there are readily available routes for individuals to secure good environmental quality for themselves and their communities.” (The Scottish Government, 2023[23]). In Mexico, the Secretariat of Environment and Natural Resources (SEMARNAT) defines environmental justice as “obtaining a timely legal solution to an environmental conflict, taking into account that all people must partake of the same conditions to access environmental justice” (Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales, 2020[24]). In both countries, detailed attention is paid to the importance of engagement and participation, suggesting a greater emphasis on procedural justice in these countries.

In Scotland, the “Report into the Effectiveness of Governance Arrangements’’ highlights the “Human Rights Bill” which recognises the right to a healthy environment as a human right and improves access to justice by providing more ways through which individuals can hold public authorities to account (The Scottish Government, 2023[23]). Moreover, in 2016 the Scottish Government consulted the public on developments in environmental justice (ibid).19 The current Mexican administration places particular emphasis on promoting participation for communities and groups at risk such as Indigenous groups and Afro-Mexicans through its “Environmental Justice Provision Programme 2021-2024” (Procuraduria Federal de Proteccion al Ambiente, Gobierno de México, 2021[25]).

3.4. Examples of indirect approaches across countries

Copy link to 3.4. Examples of indirect approaches across countries3.4.1. Added Protection and Safeguards

Copy link to 3.4.1. Added Protection and SafeguardsThe responses of the countries categorised as having added protection and safeguards to promote environmental justice indicated that their policies, laws, or procedures target particularly vulnerable groups more broadly, instead of focussing specifically on the environment. For example, England is subject to the UK Parliament’s “Equality Act (2010)” which aims to reduce “[…] discrimination and harassment related to certain personal characteristics […]”20 (The National Archives, 2010[26]). The Act applies indirectly to a variety of areas where potential discrimination could arise including in the development of environmental policy. For example, the official guidance on conducting policy appraisal – the Green Book – mandates that all impact assessments pay due regard to the Equality Act (Government of the United Kingdom, 2022[27]). While this does not target environmental justice directly, it demonstrates a detailed recognition of situations in which certain groups are more vulnerable and provides an additional legal framework for addressing their needs.

Similarly, Switzerland’s regulatory impact assessment methodology (“RFA”) demonstrates thorough consideration of the impacts of policies on particular groups (State Secretariat for Economic Affairs, 2022[28]). Although its response identifies fair treatment of all groups as a guiding normative principle, it recognises the need to mitigate inequities and prevent them from becoming reinforced. For instance, checkpoint three of Switzerland’s “RFA” methodology explicitly asks “[…] what impact (costs, benefits, distribution effects) does the proposal have on individual social groups?”. Amongst other things, the “RFA” cites education, employment, wages, and working conditions which suggests a lesser focus on categories, such as race or gender, in favour of identifying socio-economically vulnerable groups. Perhaps this divergence of emphasis between, the Swiss and, for example, US or Canadian governments, reflects the different historical origin of environmental justice in North America. Switzerland offers an example of an approach which – while not targeting environmental justice directly – provides protection for vulnerable groups through additional procedural safeguards.

Within New Zealand’s regulatory impact analysis, additional safeguards are present to consider the impact on equity and disproportionate impacts on different population groups. Such recognition of vulnerability of some communities is also reflected in the requirements for consultation of Māori, mandated by many pieces of environmental legislation including National Policy Statements under the Resource Management Act 1991. In addition, Māori need to be consulted or involved in local planning processes by local government. Strengthening this mandate, the Ministry for the Environment has recently committed to “reflect the Treaty of Waitangi21 in environmental decision-making” in its Strategic intentions (2023-2027) (Ministry for the Environment, 2023[29]). Another group that is given attention in environmental policymaking in New Zealand is the youth – a Climate Change Youth Advisory Group is contributing to the ongoing development of the second Emissions Reduction Plan, by supporting the design of engagement measures as well as providing inputs into the policy development.

Despite not using the term environmental justice explicitly, France recognises the existence of “environmental inequalities” and that some parts of the population may be more exposed to environmental risks. To reduce such risks, the “National and Regional Environmental Health Plans” were put in place to “[…] better account for the concept of the “exposome” (see also Section 2.4.1 in Chapter 2), all exposure to environmental hazards throughout life, with particular attention paid to populations at risk or those most exposed’’. Differentiated impacts on vulnerable groups are also mentioned in a report by France Stratégie, which concludes that young people living in large cities and those facing higher unemployment and poverty rates in rural and former industrial regions are particularly exposed to pollution (Fosse, Salesse and Viennot, 2022[30]). The French administration also notes that “environmental equity” is used as a guiding principle when choosing policy instruments and that gender, disability, and young age are mandatory considerations when developing policy, demonstrating some consideration of the distributional impacts of environmental policies.

3.4.2. Guarantee of rights

Copy link to 3.4.2. Guarantee of rightsMost countries have legislative and policy-based frameworks – often in the context of environmental rights or rights to appeal decisions of public bodies – that provide a baseline of protection for environmental justice concerns. For example, Article 2(a) of Costa Rica’s “Organic Law of the Environment”, number 7554, declares that the “[…] environment is the common heritage of all the inhabitants of the Nation and therefore both at the institutional level (of the Executive Branch) and at the jurisdictional level, citizens have the right to equal treatment […]” (General Attorney of the Republic, 1995[31]). Moreover, the Costa Rican government cites the equality of persons before the law and their right to non-discrimination, Article 33 of its Constitution, as an example of the protection that applies to potentially vulnerable groups.

Similarly, the Croatian government, citing Article 38.4 of its Constitution, protects the right of citizens to access information which provides a baseline protection for procedural aspect of environmental justice. It is noteworthy that constitutional protection of rights – though not specifically targeted – provides a strong basis for the development of more targeted protection of environmental justice. Meanwhile, Japan’s focus on prevention of inequitable burden seeks to ensure broad-based protection and speedy remedies through institutionalised mechanisms that were progressively strengthened against the backdrop of rapid industrial growth (Box 3.3).

Box 3.3. Japan’s preventive approach to environmental justice

Copy link to Box 3.3. Japan’s preventive approach to environmental justiceInstitutional mechanisms for preventing disproportionate environmental burden

Copy link to Institutional mechanisms for preventing disproportionate environmental burdenAlthough the term environmental justice is not used, Japan’s response highlights the emphasis on prevention of inequitable exposure to environmental harms from arising in the first place. The Central Environmental Council (CEC), established in 2001, is one of the key institutional mechanisms that allows for anticipating and mitigating unintended policy consequences. The CEC, a group composed of academic experts, representatives of local governments, industrial associations, labour unions and other civil society representatives with up to 30 members, regularly meet to study and deliberate on new environmental policy. Particular consideration is given to ensure that representatives of groups affected by the policy are present. These deliberations form the basis upon which the bills are drafted and further deliberated in the Diet (legislature).

Progressively strengthened mechanisms for prevention and speedy remedies for “Kogai”

Collectively known as Kogai, directly translating as “public harm” to characterise environmental pollution, is defined in Article 2(3) of the Basic Environment Law (1993) as “air pollution, water pollution[…], soil contamination, noise, vibration, ground subsidence and offensive odours” that affect “an extensive area as a result of business and other human activities which cause damage to human health or the living environment” (Ministry of the Environment, 1993[32]). Importantly, even if there is one victim, it is considered to affect a “broad area” as defined in the Act as long as the geographical spread is recognisable or foreseen (Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, n.d.[33]).

Japan’s preventive approach is deeply rooted in the increased incidence of pollution that accompanied its rapid economic growth from the 1950s onward. While civil lawsuits were the primary means of resolving pollution disputes, they were insufficient for victim relief and limited the speedy and appropriate resolution of pollution disputes. This is because it was difficult to prove the causal relationship between the source of the pollution and the harms, a large amount of litigation costs were required, and it took a considerable number of years for the judgment to be final (Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, n.d.[34]). Against this backdrop, in order to ensure prompt and appropriate resolution of pollution disputes, the government established the Prefectural Pollution Review Board in each prefecture and the Environmental Dispute Coordination Commission in the national government to address pollution disputes, in addition to judicial resolution by the courts, based on the Act on the Settlement of Environmental Pollution Disputes. These Board and Commission are independent in resolving disputes according to their respective jurisdictions but cooperate with each other through the exchange of information to ensure the smooth operation of the system. In addition to these organisations, each prefecture and municipality has its own pollution complaint consultation office for the prompt and appropriate resolution of pollution complaints (Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, n.d.[33]). Thus, the government has taken responsibility of proactively addressing environmental harms, resulting in progressively more preventative approach over time.

For large-scale issues, the national government has readily committed to supporting local government. A prominent example is the case of illegal dumping of toxic industrial wastes in Teshima island, which has resulted in contamination of soil and groundwater by hazardous substances in late 1970s (Takatsuki, 2003[35]). The government has enacted supporting measures to the local authorities by playing a liaising role for local authorities and local residents through mediation procedures, as well as enacting necessary legislation, and making public funds available for the waste treatment.

3.5. Key insights

Copy link to 3.5. Key insightsMost countries do not directly target environmental justice per se but do so indirectly through a variety of other related measures. The ways in which countries address environmental justice directly also vary and can entail all three branches of government. Likewise, indirect approaches to environmental justice differ; some countries protect environmental justice by guaranteeing rights to all, whereas others provide additional protection to vulnerable groups through safeguards such as anti-discrimination law or detailed impact assessment methodologies.

Rights-based approaches provide an important baseline consisting of procedural and substantive rights that are important for experiencing a healthy environment. These might include the rights to equal protection of the law, to participate in the conduct of government and public affairs, and to seek, receive and impart information. While the case of Colombia shows how such a baseline can be utilised to protect environmental justice, there is an intermediate step in this process – the judiciary. In such cases, a grievance must already have arisen for the right to gain further protection, and there are often barriers to engagement in such legal processes. Supplementary measures could promote environmental justice ex ante – for example through policies, initiatives, or more targeted law that positively mandate stronger protection of environmental justice. They can also strengthen and enable the legal basis for rectifying existing practices that are considered unjust (Agyeman, Bullard and Evans, 2002[36]).

There is a clear relationship between direct approaches to environmental justice and greater detail of coverage of the three substantive aspects environmental justice concerns. Countries that deploy direct approaches consider all three dimensions of environmental justice and do so in greater detail. The countries that deploy indirect approaches tend to consider environmental justice concerns more generally, through less targeted measures.

Another key insight from this analysis is that there is widespread focus upon both inequitable exposure to environmental hazards and amenities, as well as barriers to information and participation in environmental decision-making. However, consideration of the inequitable distribution of the costs and benefits of environmental policy is a relative blind-spot in country approaches to environmental justice.

References

[46] Agencia Peruana de Noticias (2018), Justicia Ambiental: estos son los 10 compromisos del Pacto en Madre de Dios, https://andina.pe/agencia/noticia-justicia-ambiental-estos-son-los-10-compromisos-del-pacto-madre-dios-696792.aspx (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[36] Agyeman, J., R. Bullard and B. Evans (2002), “Exploring the Nexus: Bringing together sustainability, environmental justice and equity”, Space and Polity, Vol. 6/1, https://doi.org/10.1080/13562570220137907.

[16] Article 19 (2016), A Deadly Shade of Green. Threats to Environmental Human Rights Defenders in Latin America, https://www.article19.org/data/files/Deadly_shade_of_green_A5_72pp_report_hires_PAGES_PDF.pdf.

[18] Corte Constitucional de Colombia (2019), Sentencia T-021/19, https://www.corteconstitucional.gov.co/relatoria/2019/T-021-19.htm (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[17] Corte Constitucional de Colombia (2014), Sentencia T-294/14, https://www.corteconstitucional.gov.co/relatoria/2014/t-294-14.htm (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[7] Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment (1998), White Paper on Environmental Management Policy for South Africa, https://www.dffe.gov.za/sites/default/files/legislation/2023-09/environemntal_management_0.pdf.

[39] Fairburn, J., G. Walker and G. Smith (2005), Investigating environmental justice in Scotland: links between measures of environmental quality and social deprivation, https://eprints.staffs.ac.uk/1828/1/1828.pdf.

[30] Fosse, J., C. Salesse and M. Viennot (2022), Inégalités environnementales et sociales se superposent-elles ?, https://www.strategie.gouv.fr/publications/inegalites-environnementales-sociales-se-superposent.

[31] General Attorney of the Republic (1995), Ley Orgánica del Ambiente, http://www.pgrweb.go.cr/SCIJ/Busqueda/Normativa/Normas/nrm_texto_completo.aspx?param1=NRTC&nValor1=1&nValor2=27738&nValor3=93505&strTipM=TC.

[21] German Environment Agency (2015), Environmental justice in urban areas - development of practically oriented strategies and measures to reduce socially unequal distribution of environmental burdens, https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/medien/378/publikationen/umwelt_und_gesundheit_01_2015_summary.pdf.

[22] German Institute of Urban Affairs (n.d.), Environmental Justice Toolbox, https://www.toolbox-umweltgerechtigkeit.de/instrumente (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[5] Gobierno de Colombia (2023), Bases del Plan Nacional de Desarrollo 2022-2026, https://colaboracion.dnp.gov.co/CDT/portalDNP/PND-2023/2023-02-23-bases-plan-nacional-de-desarrollo-web.pdf.

[8] Government of South Africa (1998), National Environmental Management Act 107 of 1998, https://www.gov.za/documents/national-environmental-management-act (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[6] Government of South Africa (1996), Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, https://www.gov.za/documents/constitution/constitution-republic-south-africa-1996-04-feb-1997 (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[27] Government of the United Kingdom (2022), The Green Book, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-green-book-appraisal-and-evaluation-in-central-government/the-green-book-2020 (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[9] Hall, J. and P. Lukey (2023), “Public participation as an essential requirement of the environmental rule of law: Reflections on South Africa’s approach in policy and practice”, African Human Rights Law Journal, pp. 303-332, https://doi.org/10.17159/1996-2096/2023/v23n2a4.

[41] HM Treasury (2022), The Green Book, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-green-book-appraisal-and-evaluation-in-central-government/the-green-book-2020 (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[38] Knox, J. (2020), Constructing the human right to a healthy environment, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-031720-074856.

[19] Korea Legislation Research Institute (2019), Framework Act on Environmental Policy, https://elaw.klri.re.kr/eng_mobile/viewer.do?hseq=62237&type=sogan&key=16 (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[11] Korea Legislation Research Institute (2008), Environmental Health Act, https://elaw.klri.re.kr/eng_mobile/viewer.do?hseq=56206&type=part&key=36 (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[1] Lewis, B. (2012), “Human Rights and Environmental Wrongs: Achieving Environmental Justice through Human Rights Law”, International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy, Vol. 1/1, https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.v1i1.69.

[48] Ministerio del Interior, Gobierno de Colombia (2022), Decreto 1535 – 04 agosto 2022 – para adoptar la Política Pública de Participación Ciudadana, y se dictan otras disposiciones, https://www.mininterior.gov.co/normativas/decreto-1535-04-agosto-2022-para-adoptar-la-politica-publica-de-participacion-ciudadana-y-se-dictan-otras-disposiciones/ (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[29] Ministry for the Environment (2023), Strategic intentions (2023-2027). He takunetanga rautaki 2023–2027, https://environment.govt.nz/assets/publications/strategic-intentions-2023-27.pdf.

[10] Ministry of Environment (2019), The 5th Comprehensive Plan for National Environment (2020-2040), https://www.me.go.kr/home/web/policy_data/read.do?menuId=10259&seq=7448 (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[13] Ministry of Environment of Peru (2021), Protocolo sectorial para la protección de las personas defensoras ambientales, https://cdn.www.gob.pe/uploads/document/file/2037171/RM.%20134-2021-MINAM%20con%20anexo%20Protocolo%20Sectorial.pdf.pdf?v=1627231168.

[12] Ministry of Environment of Peru (2005), Ley General del Ambiente, https://www.minam.gob.pe/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Ley-N%C2%B0-28611.pdf.

[34] Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (n.d.), Environmental Dispute Coordination Commission, https://www.soumu.go.jp/kouchoi/english/ (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[33] Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (n.d.), Kogai Towa, https://www.soumu.go.jp/kouchoi/knowledge/how/e-dispute.html (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[42] Ministry of Justice (2023), Te Tiriti o Waitangi - Treaty of Waitangi, https://www.justice.govt.nz/about/learn-about-the-justice-system/how-the-justice-system-works/the-basis-for-all-law/treaty-of-waitangi/.

[32] Ministry of the Environment (1993), The Basic Environment Law Chapter 1, https://www.env.go.jp/en/laws/policy/basic/ch1.html (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[15] OECD (2017), OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Korea 2017, OECD Environmental Performance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264268265-en.

[50] Parliament of Canada (2023), An Act respecting the development of a national strategy to assess, prevent and address environmental racism and to advance environmental justice, https://www.parl.ca/legisinfo/en/bill/44-1/c-226 (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[45] Poder Judicial del Perú (n.d.), Pacto de Madre de Dios por la Justicia Ambiental, https://www.pj.gob.pe/wps/wcm/connect/ambiente/others/as_justicia/as_pacto_md (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[44] Poder Judicial del Perú (n.d.), Poder Judicial Crea Observatorio de Justicia Ambiental, https://www.pj.gob.pe/wps/wcm/connect/ambiente/s_amb_prin/as_noticias/cs_n_observatorio_ambiental (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[37] Poustie, M. (2004), Environmental justice in SEPA’s environmental protection activities: a report for the Scottish Environment Protection Agency, https://www.sepa.org.uk/media/163177/environmental_justice.pdf.

[49] Presidencia de la República, Gobierno de Colombia (2023), Con llamado al Congreso para que se comprometa con pilares de justicia ambiental y social, Presidente Petro instaló nueva legislatura, https://petro.presidencia.gov.co/prensa/Paginas/Con-llamado-al-Congreso-para-que-se-comprometa-con-pilares-de-justicia-ambi-230720.aspx (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[20] Prime Minister of Canada (2021), Minister of Environment and Climate Change Mandate Letter, https://www.pm.gc.ca/en/mandate-letters/2021/12/16/minister-environment-and-climate-change-mandate-letter (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[25] Procuraduria Federal de Proteccion al Ambiente, Gobierno de México (2021), Programa de Procuración de Justicia Ambiental 2021 2024, https://www.gob.mx/profepa/documentos/programa-de-procuracion-de-justicia-ambiental-2021-2024 (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[43] SAFLII (2022), Sustaining the Wild Coast NPC and Others v Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy and Others (3491/2021) [2022] ZAECMKHC 55; 2022 (6) SA 589 (ECMk) (1 September 2022), https://www.saflii.org/za/cases/ZAECMKHC/2022/55.html.

[24] Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (2020), Programa Sectorial de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales 2020-2024, https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/566832/PROMARNAT-2020-2024.pdf.

[28] State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (2022), Regulatory Impact Assessment - Checklist, https://www.seco.admin.ch/seco/de/home/Publikationen_Dienstleistungen/Publikationen_und_Formulare/Regulierung/regulierungsfolgenabschaetzung/hilfsmittel/checkliste-rfa.html (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[35] Takatsuki, H. (2003), “The Teshima Island industrial waste case and its process towards resolution”, Journal of Material Cycles and Waste Management, Vol. 5/1, https://doi.org/10.1007/s101630300005.

[26] The National Archives (2010), Equality Act 2010, https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/introduction (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[23] The Scottish Government (2023), Environmental governance arrangements: report, https://www.gov.scot/publications/report-effectiveness-environmental-governance-arrangements/ (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[14] UNDP (2022), Environmental Justice: securing our right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment, https://www.undp.org/publications/environmental-justice-securing-our-right-clean-healthy-and-sustainable-environment.

[2] United Nations Development Programme (2022), Environmental Justice: Securing our right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment, https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/2022-06/Environmental-Justice-Technical-Report.pdf.

[40] United Nations Human Rights Council (2022), The right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment: non-toxic environment, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G22/004/48/PDF/G2200448.pdf?OpenElement.

[4] United States Environmental Protection Agency (2023), Summary of Executive Order 12898 - Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations | US EPA., https://www.epa.gov/laws-regulations/summary-executive-order-12898-federal-actions-address-environmental-justice#:~:text=for%20all%20communities.-,E.O.,strategy%20for%20implementing%20environmental%20justice. (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[51] White House (2024), Biden-Harris Administration Finalizes Reforms to Modernize Environmental Reviews, Accelerate America’s Clean Energy Future, Simplify the Process to Rebuild our Nation’s Infrastructure, and Strengthen Public Engagement, https://www.whitehouse.gov/ceq/news-updates/2024/04/30/biden-harris-administration-finalizes-reforms-to-modernize-environmental-reviews-accelerate-americas-clean-energy-future-simplify-the-process-to-rebuild-our-nations-infrastructure/ (accessed on 13 May 2024).

[3] White House (2023), Executive Order on Revitalizing Our Nation’s Commitment to Environmental Justice for All, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2023/04/21/executive-order-on-revitalizing-our-nations-commitment-to-environmental-justice-for-all/ (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[47] White House (1994), Executive Order 12898 of February 11, 1994 Federal Actions To Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations, https://www.archives.gov/files/federal-register/executive-orders/pdf/12898.pdf.

Notes

Copy link to Notes← 1. These are: (i). distribution of exposure to environmental risks hazards and access to amenities, (ii) distribution of the benefits and costs of environmental policies and (iii) participation in environmental decision-making and access to justice and information.

← 2. Responses from eight countries and the European Commission explicitly mentioned just transition.

← 3. Illustratively, there are already innumerable precedents in which national courts have adjudicated on environmental rights around the world (Knox, 2020[38]).

← 4. There is also a new regulation on environmental impact assessment that expressly incorporates environmental justice considerations (White House, 2024[51])

← 5. Executive Order 14096, titled Revitalizing Our Nation’s Commitment to Environmental Justice for All (White House, 2023[3]).

← 6. Executive Order 12898, titled Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations (White House, 1994[47]).

← 7. See ruling T-294/14 (Corte Constitucional de Colombia, 2014[17]).

← 8. See ruling T-021/19 (Corte Constitucional de Colombia, 2019[18]).

← 9. See Decree 1535 of 4 August 2022 (Ministerio del Interior, Gobierno de Colombia, 2022[48]).

← 10. However, the complementary desk research has found that the Colombian President has recently committed to establishing – through the legislature – measures that are grounded in two core pillars: social justice, and environmental justice. See (Presidencia de la República, Gobierno de Colombia, 2023[49]).

← 11. Sustaining the Wild Coast NPC and Others v Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy and Others (3491/2021) [2022] ZAECMKHC 55; 2022 (6) SA 589 (SAFLII, 2022[43]).

← 12. South Africa’s Constitution recognises 11 languages. isiZulu or isiXhosa are commonly spoken languages in the affected communities.

← 13. Highlighting Peru’s focus on the procedural angle of environmental justice, it was identified in desk research that in 2017, the Peruvian judiciary launched the “Madre de Dios Pact for Environmental Justice in Peru”, signed by, among others, the Ministry of Environment, and civil organisations. The Pact includes commitments to strengthen the constitutional and legal recognition of environmental rights and facilitating access to environmental justice through, among others, the establishment of the Environmental Justice Monitoring Observatory – an online platform gathering statistical information on environmental cases, jurisprudence and regulations (Poder Judicial del Perú, n.d.[45]; Agencia Peruana de Noticias, 2018[46]; Poder Judicial del Perú, n.d.[44]).

← 14. Some countries have signed but not ratified the Agreement. The Escazú Agreement has been signed by 24 countries and ratified by 16 countries as of May 13th, 2024.

← 15. See Private Members Bill C-226 (44-1) titled: “An Act respecting the development of a national strategy to assess, prevent and address environmental racism and to advance environmental justice” (Parliament of Canada, 2023[50]).

← 16. Such as Switzerland’s “RFA-Checklist” (State Secretariat for Economic Affairs, 2022[28]) and the UK’s “Green Book” (HM Treasury, 2022[41]).

← 17. However, this narrower focus may reflect the fact that Germany’s Environment Agency responded to the survey rather than its national administration.

← 18. Although the term was initially used to describe areas that became uninhabitable due to nuclear experiments, it can be now applied to any “area where residents suffer devastating physical and mental health consequences and human rights violations as a result of living in pollution hotspots and heavily contaminated areas” – such areas were also identified in Romania, Zambia, United States and Canada (United Nations Human Rights Council, 2022[40]).

← 19. Furthermore, the desk research has identified several relevant reports on environmental justice, commissioned by the Scottish government agencies. See: (Fairburn, Walker and Smith, 2005[39]), (Poustie, 2004[37]).

← 20. The “Equality Act” is applicable across England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. While Wales and Northern Ireland did not submit separate responses to the OECD Survey, several principles outlined in the English response apply to Wales and Northern Ireland as well.

← 21. The Te Tiriti o Waitangi, “Treaty of Waitangi” is an agreement between the British Crown and Māori chiefs in 1840 (Ministry of Justice, 2023[42]).