This chapter draws together various conceptualisations of environmental justice based on a literature review. The chapter traces the evolution of environmental justice around the world, highlighting the ways in which the idea has come to be used by different stakeholders. It then unpacks some substantive issues through which environmental justice concerns can manifest as well as some of their underlying drivers.

Environmental Justice

2. A primer on environmental justice

Copy link to 2. A primer on environmental justiceAbstract

Advancing environmental justice begins with recognising how “the environment is socially differentiated and unevenly available” (Walker, 2012, p. 214[1]). It is a plural concept with no universal definition (Debbané and Keil, 2004[2]), encompassing an expansive set of ideas around justice defined in terms of distribution, processes, and recognition (Schlosberg, 2007[3]). As countries increase their efforts to tackle environmental degradation, pollution and climate change, the concept of environmental justice can shed light on how to ensure fairness in the processes and outcomes of environmental policymaking.

2.1. Evolution of environmental justice across the world: A brief history

Copy link to 2.1. Evolution of environmental justice across the world: A brief historyThe history of the concept demonstrates that environmental justice has evolved differently across regions (Schlosberg, 2013[4]). The varied focus of policy and scholarship over the decades across countries runs in parallel to the differences in priorities assigned to specific environmental justice concerns and communities. Often facilitated by deliberate efforts of transnational networking among activists, there has been a transfer and diffusion of ideas around environmental justice (Debbané and Keil, 2004[2]). While the concept is often considered to have its roots in the United States, it has become internationalised, with research documenting movements addressing similar concerns across the world (Martinez-Alier et al., 2016[5]) (Box 2.1).

2.1.1. North America

Copy link to 2.1.1. North AmericaEnvironmental justice has decades of history dating back to at least the 1980s in the United States, originating from the protests against illegal dumping of toxic waste in predominantly African-American and low-income Warren County in North Carolina (Schlosberg and Collins, 2014[6]). Grassroots movements across the United States and efforts towards evidence gathering1 helped raise awareness of the disproportionate exposure of ethnic and racial minority and low-income populations to environmental hazards, leading to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) placing environmental justice on its policy agenda. Executive Order 128982 followed in 1994, requiring consideration of environmental justice across federal government for the first time (United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2023[7]).3

Executive Order 12898 has attracted wider scholarly attention to environmental justice in the United States. While early research focussed on documenting differentiated siting of hazardous waste (Bullard, 1983[8]), the scope gradually expanded to include exposure to other environmental hazards, such as the distribution of air, water and noise pollution (Banzhaf, Ma and Timmins, 2019[9]) as well as varying impact of environmental policies (Shapiro and Walker, 2021[10]). The environmental justice policy agenda has been progressively strengthened over the years, with the EPA now putting it squarely at the centre of its work (OECD, 2023[11]). In 2021, President Joe Biden signed Executive Order 14008 4 that enhanced the agenda to “advance environmental justice” in efforts to address climate change (White House, 2021[12]). Most recently, Executive Order 140965 deepened “the whole-of-government commitment to environmental justice” (White House, 2023[13]).

As the US movement made headlines internationally in 1980s, it prompted the identification of similar patterns of injustice in other countries over time (Mohai, Pellow and Roberts, 2009[14]). In Canada, a recent body of scholarship exploring inequitable distribution of environmental harms, together with environmental justice activism, have propelled environmental justice to feature more prominently in the policy agenda. With research documenting inequitable distribution of environmental harms, including water contamination in Indigenous and Afro-Canadian communities in Nova Scotia (Waldron, 2018[15]) and exposure to mercury among the Grassy Narrows First Nations community (Philibert, Fillion and Mergler, 2020[16]), the severity of disparities in access to a healthy environment has become increasingly recognised. Subsequently, draft legislation to develop a national strategy to “assess, prevent and address environmental racism and to advance environmental justice” is now in motion (Parliament of Canada, 2023[17]).

2.1.2. Europe

Copy link to 2.1.2. EuropeWhile the role of grassroots movements is also prominent in Europe, environmental justice has been driven onto the policy agenda in a relatively top-down manner, in response to intergovernmental agreements that seek to advance and uphold human rights (Mitchell, 2019[18]). The Aarhus Convention6 – establishing rights and duties7 for ensuring access to information and participation in environmental decision-making – has had an influence on the evolution of the European Union (EU) and informed national governments’ legislations and efforts to identify their role (Bell and Carrick, 2017[19]).

In addition, there has also been notable focus on assessments of environmental justice concerns through evidence and data collection and development of indicators in some European countries, with focus on the spatial distribution of health-related environmental burdens and its relation to economic deprivation (Köckler et al., 2017[20]). In the United Kingdom, these efforts resulted in collection of granular neighbourhood data on a range of socio-economic and environmental factors and the creation of an “Index of Multiple Deprivation” (IMD), subsequently informing the development of IMD elsewhere, including Germany (Fairburn, Maier and Braubach, 2016[21]). Recent region-wide evidence also documents uneven exposure to environmental hazards and their health impact, both across and within European countries (European Environment Agency, 2018[22]).

Unlike in North America, there has not been a distinct development of environmental justice as a concept along racial and ethnic backgrounds in Europe. However, the relative lack of evidence highlighting these concerns may also reflect data constraints, since some European countries, including France, prohibit data collection on racial and ethnic origins.8 Nonetheless, there are some qualitative studies documenting environmental injustice among ethnic minorities in Europe. For instance, against the backdrop of the transition to market economies leading to further geographical isolation of Roma communities in Central and Eastern European countries, wealth of case studies demonstrates that the communities experience inequitable access to environmental amenities and services (Heidegger and Wiese, 2020[23]).

2.1.3. Latin America

Copy link to 2.1.3. Latin AmericaThe development of the environmental justice agenda in Latin American countries coincides with the history of the region’s deeper integration into the global economy since the 1990s (Rasmussen and Pinho, 2016[24]). Research in the region has subsequently explored the risks associated with rapid industrial development, such as industrial waste and pollution and their disproportionate impact on low-income groups (Carruthers, 2008[25]). The evolution of how environmental justice has come to be advanced in Mexico is illustrative, with early evidence in 1990s finding disproportionate exposure to chemical hazards in neighbourhoods proximate to industrial parks catered towards exports (ibid). Complaints on health impacts by communities and activists eventually led to the co-operation between public agencies in Mexico and the United States, resulting in the commitment to treat industrial wastes in the early 2000s (ibid). These cases spotlighted the lack of information and structural mechanisms to address environmental justice concerns, resulting in a series of efforts by governments including enhanced reporting on pollution.

Environmental justice concerns in the region are also compounded by rapid urbanisation and related challenges with providing adequate housing and amenities, leading to the development of informal settlements and slums that are more vulnerable to both natural and man-made environmental hazards (Vásquez et al., 2018[26]). There has also been attention paid to the historical roots of the unequal distribution of land and water resources (ibid). For instance, in many parts of Latin America, the notion of autonomy and self-determination among Indigenous communities has acquired an environmental dimension due to the rise of industries, including land use intensive agriculture (Ulloa, 2017[27]).

Notably, an emphasis on regional co-operation towards environmental justice has developed in Latin America over the last decade. The reaffirmed commitment to rights to access to information, participation, and justice (defined in terms of legal recourse) in environmental matters by several Latin American countries at the Rio+20 Summit in 2012 has subsequently led to the conclusion of Escazú Agreement, a regional legal instrument guaranteeing and advancing these rights (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, 2022[28]) (Box 2.1). The notion of environmental justice in the region therefore brings participation and access to legal recourse into sharper focus. These developments may reflect, amongst other things, the cross-country nature of major biomes such as the Amazon Rainforest spanning countries, as well as the related concerns over the seeming impunity of those committing environmental crimes and attacks on environmental defenders.9 For instance, in the third meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Escazú Agreement, States Parties approved the Action Plan on Human Rights Defenders in Environmental Matter (United Nations, 2024[29]). The Plan highlights priorities and strategic measures to advance the implementation of Article 9 of the Escazú Agreement on human rights defenders in environmental matters.

2.1.4. Asia-Pacific

Copy link to 2.1.4. Asia-PacificUnlike many other countries in which environmental justice movements took hold following the catalytic movements in the United States, environmental justice is not a concept commonly referred to in Japan (Fan and Chou, 2017[30]) and Australia (Schlosberg, Rickards and Byrne, 2018[31]). Nonetheless, the term has been used in the broader contexts of studies of environmental pollution during industrial growth in the late 1950s10 in Japan (Fan and Chou, 2017[30]). The term has also been taken up by Australian Aboriginal communities, whose environmental concerns over natural resources reflect their connection to place and their sense of moral and spiritual obligations to care for “Country”11 (Schlosberg, Rickards and Byrne, 2018[31]). While the term is also uncommon in New Zealand, the culturally informed approach to policy seeks to recognise the disparate impacts environmental and climate policy might have on Indigenous populations (Ministry for the Environment, 2022[32]).

South Korea is a notable exception in the region, with progressively explicit focus on environmental justice in environmental policy over the last decades. The concept first garnered public attention in 1999, with the Environmental Justice Forum led by environmental activists raising visibility of the issue of unequal access to safe drinking water (Bell, 2014[33]). Greater recognition of the differentiated environmental quality across communities and regions has prompted South Korea to adopt alleviating measures, including through the amendment of the Framework Act on Environmental Policy in 2019.

2.1.5. Africa

Copy link to 2.1.5. AfricaIn Africa, there has been a notable development on environmental justice in South Africa, which can be traced back to the late 1980s movements against the backdrop of broader struggle for democracy, gaining momentum in the early 1990s (McDonald, 2002[34]). Trade unions and civil society organisations have played a significant role in drawing attention to the failures of the past environmental policies and exposure to toxic waste (Lukey, 2002[35]). Environmental justice entered the popular lexicon in South Africa in the conference organised by Earthlife Africa, one of the key outcomes of which was the establishment of a nation-wide organisation that coordinated activities of environmental and social justice activists (McDonald, 2002[34]). The recognition of environmental rights, including with respect to access to participation followed in the 1994 Bill of Rights, later adopted in the new Constitution in 1996 (Hall and Lukey, 2023[36]).

Much of the environmental justice research in Africa has been anchored in the context of economic development, elucidating linkages between hazards posed by certain industries and their simultaneous centrality to their national economies. Particular attention is paid to the impact of extractive industries (Aldinger, 2013[37]; Banza et al., 2009[38]; Martinez-Alier, 2001[39]) or electronic waste (Akese and Little, 2018[40]) on human health and the environment. Some also highlight that the scope of environmental justice might be in fact broader in sub-Saharan Africa than often envisaged in other countries, reflecting the unique nature of rural communities’ relationship with land and their reliance on natural resources (Aldinger, 2013[37]).

Box 2.1. Documenting environmental justice concerns around the world: The Global Environmental Justice Atlas (EJAtlas)

Copy link to Box 2.1. Documenting environmental justice concerns around the world: The Global Environmental Justice Atlas (EJAtlas)The environmental justice movement has been described as “locally embedded but globally connected” (Cock, 2006, p. 22[41]). An illustrative outcome of the deliberate transnational networking of environmental justice activism is the Environmental Justice Atlas (EJAtlas), created in 2014. The EJAtlas is an interactive online archive, documenting and cataloguing cases of socio-environmental conflicts around the world (Global Environmental Justice Atlas, 2024[42]). Exemplifying the evolution of environmental justice as activism and a field of research, it is maintained by collaborators across countries including civil society organisations and academics.

The EJAtlas provides visibility to the instances of environmental justice concerns that may otherwise remain unrecognised (Martinez-Alier et al., 2016[5]). While each documented incidence reflects local grievances, it draws attention to the prevalence of environmental justice concerns around the world. Over the last 50 years, over 3300 cases have been documented (Global Environmental Justice Atlas, 2024[42]).

2.2. Key conceptual pillars of environmental justice and related concepts

Copy link to 2.2. Key conceptual pillars of environmental justice and related conceptsAs the history across regions demonstrates, the concept of environmental justice articulates a diverse set of ideas, and there is currently no universal definition or metric to measure environmental justice (Walker, 2012[1]). Different ways in which environmental justice concerns manifest can limit the extent to which the concept can be defined in a way that is useful across countries. However, there are recurrent elements that can be considered as key conceptual pillars of environmental justice:(i) distributive, (ii) procedural and (iii) recognitional justice (Schlosberg, 2004[43]).

2.2.1. Distributive justice

Copy link to 2.2.1. Distributive justiceReflecting the historical origins rooted in activism that raised visibility of environmental inequities, distributional considerations are often at the heart of environmental justice. Distributive justice draws attention to the need to consider how the multiple patterns of existing inequities based on characteristics of communities might result in inequitable exposure, vulnerability to environmental hazards and inability to access environmental amenities, as well as the differentiated impact policies can have on communities.

2.2.2. Procedural justice

Copy link to 2.2.2. Procedural justiceEnvironmental justice also highlights the importance of processes and procedures, recognising the need to understand how decisions are made, who can be involved and influence environmental decisions. Procedural justice can be understood both as a means to correct for inequitable distribution as well as an end in itself for achieving environmental justice (Bell and Carrick, 2017[19]). Reflecting this dual importance, environmental justice movements often call for various formats of participation that are attuned to the diversity of the communities (e.g. cultural and linguistic) to enable their meaningful participation in environmental decision-making (Schlosberg, 2004[43]). The fundamental importance of meaningful participation in environmental decision-making and access to information as human rights is also highlighted in various international and regional instruments (Box 2.2).

2.2.3. Recognitional justice

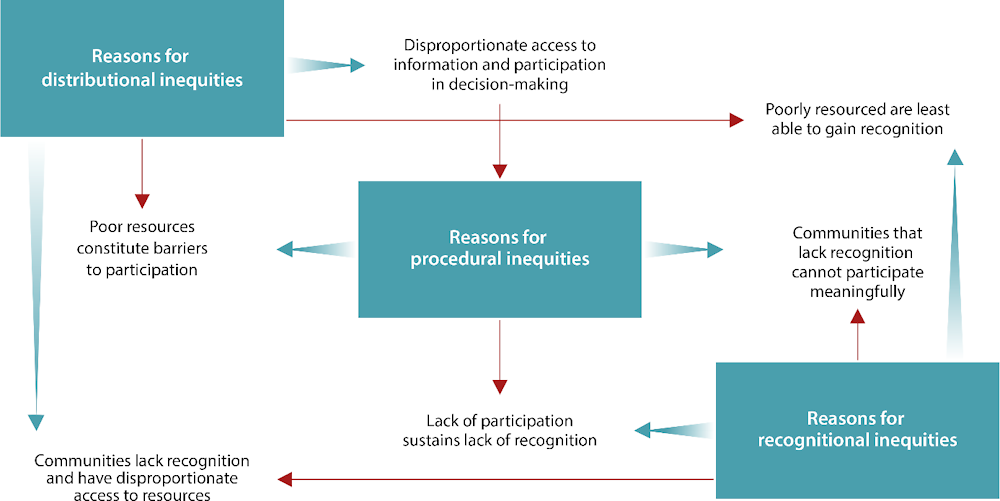

Copy link to 2.2.3. Recognitional justiceRecognitional justice identifies the disrespect and systematic undervaluation of certain communities as a source of injustice (Whyte, 2017[44]). Lack of recognition may arise from the failure to acknowledge the varying environmental and cultural identities and heritages (Schlosberg, 2004[43]; Fraser, 2000[45]). Recognitional justice is often discussed in the contexts of racialised minorities and Indigenous Peoples, but it is an encompassing concept that cautions against systemic and excessive generalisation of groups and communities (Whyte, 2017[44]).12 Respecting the diverse values and experiences of communities is therefore seen as an antecedent condition for attaining distributional and procedural justice. Figure 2.1 describes the complex interlinkages that demonstrate how these three pillars of (in)justice can reinforce each other.

Figure 2.1. Interlinkages of distributive, procedural and recognitional environmental (in)justice

Copy link to Figure 2.1. Interlinkages of distributive, procedural and recognitional environmental (in)justiceBox 2.2. Role of international instruments in advancing procedural environmental justice

Copy link to Box 2.2. Role of international instruments in advancing procedural environmental justiceThe Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-Making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters (Aarhus Convention), 1998

Copy link to The Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-Making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters (Aarhus Convention), 1998While the Convention does not explicitly refer to environmental justice, it obliges Parties to guarantee access rights to information, participation in decision-making and justice with the objective “to contribute to the protection of the right of every person of present and future generations to live in an environment adequate to his or her health and well-being” (UNECE, 1998[46]). In the European Union, these obligations have been translated into European law through directives that are directly applicable in all EU member states through the Access to Environmental Information Directive (2003/4/EC) and the Public Participation Directive (2003/35/EC) (European Commission, n.d.[47]).

The Regional Agreement on Access to Information, Public Participation and Justice in Environmental Matters in Latin America and the Caribbean, also known as the Escazú Agreement, 2018

Copy link to The Regional Agreement on Access to Information, Public Participation and Justice in Environmental Matters in Latin America and the Caribbean, also known as the Escazú Agreement, 2018With a similar focus on procedural rights, the Escazú Agreement is an instrument aimed at both environmental and human rights protection (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, 2018[48]). The Agreement places a significant emphasis on individual and groups in vulnerable situations and includes special provisions for protecting their rights to information, participation and justice. Individuals and groups in vulnerable situations are also defined in Article 2 (e) of the agreement: “Persons or groups in vulnerable situations” means those persons or groups that face particular difficulties in fully exercising the access rights recognized in the present Agreement, because of circumstances or conditions identified within each Party’s national context and in accordance with its international obligations” (ibid). It has been ratified by 16 countries, which renders it a key instrument for advancing environmental justice in the regions. Parties to the Escazú Agreement operationalise the principles specified individually.

Common principles and regional specificities

Copy link to Common principles and regional specificitiesThe Aarhus Convention and the Escazú Agreement, although two decades apart in their respective adoption, are both important elaborations of the Principle 10 of the Rio Declaration (Barritt, 2020[49]), which notes “environmental issues are best handled with participation of all concerned citizens, at relevant level” (United Nations, 1992[50]). However, there are important differences, reflecting the regionally differentiated expressions of the seemingly universal values of promoting access rights (Barritt, 2020[49]). For instance, Escazú Agreement is the first international agreement that contains provisions (Article 9) to improve protection for environmental defenders (Andrade-Goffe, Excell and Sanhueza, 2023[51]).

2.2.4. Environmental justice and related concepts

Copy link to 2.2.4. Environmental justice and related conceptsReflecting the expansion of the environmental justice discourse across space and over time, the concepts with “justice” or “just” appellations have expanded over the last decade (Agyeman et al., 2016[52]). In particular, the concept of “climate justice” has gained currency in policy discourse in recent years. The origin of the term climate justice is intricately linked to the evolution of environmental justice (Schlosberg and Collins, 2014[6]). Climate change has a significant distributive dimension, both in its causes and effects, as evidenced by the highly uneven nature of emissions across and within countries (Bruckner et al., 2022[53])13 and the burdens borne by those least responsible for historical emissions (Agyeman, Bullard and Evans, 2002[54]). It is also routinely deployed by an array of stakeholders to mobilise action and to discuss loss and damage, historical responsibility as well as the distribution of financing and adaptation needs (Wang and Lo, 2021[55]), particularly in low-income countries (Resnik, 2022[56]). Climate justice is also rooted in intergenerational justice, problematising the inadequate consideration given to the welfare of children, youth and the future generations (Gibbons, 2014[57]).

“Just transition” is another term that has acquired prominence as distributive consequences of the transition to more environmentally sustainable economies become increasingly visible. Recognising the opportunities and challenges that come with the scale of economic and social transformation needed to address pressing environmental challenges, including climate change, it draws attention to the need to ensure that no one is left behind and for policies to compensate for the disruptive impact of the transition (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2023[58]). Originally a labour-oriented term14 deployed by trade unions in 1980s to advocate for greater protection for workers who faced the prospect of unemployment due to policy-induced economic restructuring, it has broadened to encompass multiple social and economic transitional impacts including energy access (Wang and Lo, 2021[55]). The concept has gained recognition as a guiding approach to policy design and implementation, building on the wide-spread international endorsement of the “Guidelines for a just transition towards environmentally sustainable economies and societies for all” (International Labour Organization, 2016[59]).

There are considerable ambiguities in how environmental justice, climate justice and just transition are defined and used in policy discussions. Nonetheless, they are often construed with a shared emphasis on equity and fairness, reflecting their origins and mutual influence. In addition, they all highlight the distinct vulnerability of some communities, bringing attention to the disproportionality of burdens and the importance of distributive and procedural considerations (McCauley and Heffron, 2018[60]).

While environmental justice scholarship is often associated with site- and community-specific impact (Rasmussen and Pinho, 2016[24]), there are important national and regional dimensions. Similarly, while climate justice is commonly associated with international implications of climate change, uneven impact of climate change and the adaptation needs manifest at local, regional and national scales (Schlosberg and Collins, 2014[6]). For instance, low-income groups in developing countries can be more vulnerable to climate change than higher income groups in those countries, due to skewed investments in disaster risk reduction in affluent areas15 and lower housing and land prices leading to their disproportionate settlements in risk-prone areas (Hallegatte et al., 2020[61]). The concept of just transition, meanwhile, highlights the varied sectoral impact of the transition to more environmentally sustainable economies, but it is also multiscale insofar as the social and economic transformation necessitated by the transition also brings national and international implications (McCauley and Heffron, 2018[60]).

Another distinction can be made on the temporal dimension. Some scholars consider that, although environmental justice and climate justice both weave together the lasting consequences of injustices from the past and the pressing need to address the distributive concerns of the present, climate justice and just transition also entail a distinct focus on future trajectories (Jenkins, 2018[62]). Despite these notable overlaps in theory and practice, these concepts also serve distinct and equally important purpose of framing policy discussions and informing policy design.

2.3. Unpacking the substantive issues of environmental justice

Copy link to 2.3. Unpacking the substantive issues of environmental justiceThe context-specific nature of evidence on environmental injustice defies generalisation across different countries. For instance, while environmental justice research finds low-income groups tend to experience inequitable environmental outcomes, the characterisation of these groups as universally disadvantaged may not always hold as there are local nuances as well as important exceptions (Hajat, Hsia and O’Neill, 2015[63]).

However, decades of interdisciplinary research have shown that there are also certain commonalities among environmental justice concerns across space and time, which include the following three key substantive issues: (i) inequitable exposure to environmental hazards and access to environmental amenities, (ii) inequitable distribution of the costs and benefits of environmental policy, and (iii) barriers to access environmental information, participation in decision-making and legal recourse. The characteristics of the disproportionately affected segments of the population and the extent to which specific issues are considered problematic necessarily differ across countries. It is also important to note that these three substantive issues are not exhaustive; rather they are recurring issues which have implications for environmental justice and for health outcomes in affected populations. Nonetheless, the salience of these issues suggests that there is a scope for mutual learning in terms of how governments can identify, analyse and address these concerns.

2.3.1. Inequitable exposure to environmental hazards and access to environmental amenities

Copy link to 2.3.1. Inequitable exposure to environmental hazards and access to environmental amenitiesResearch on environmental justice has long documented the inequitable distribution and exposure to both natural and man-made environmental risks. These can entail exposure to: (i) point source pollution (e.g. toxic chemical release from industrial facilities), (ii) non-point source pollution (e.g. water contamination from agricultural runoff) and (iii) natural hazards (e.g. flooding). While some of the contaminants have established and recognised exposure pathways, there are other pathways, as well as the uneven availability of coping mechanisms that are often given little attention or poorly understood. Furthermore, recent research has also expanded the scope of inquiry to consider differential access to environmental amenities which may exacerbate existing vulnerabilities.

These inequities can also increase risks of adverse health and welfare outcomes of communities already overburdened by pollution. With evidence establishing the links between health and contaminants such as air pollution – the most significant environmental cause of mortality (Manisalidis et al., 2020[64]) – inequitable exposure can interact with other social determinants of health16 and individual vulnerabilities, translating into further exacerbation of inequitable health outcomes.

Types of pollution and unevenly available adaptive mechanisms

Copy link to <strong>Types of pollution and unevenly available adaptive mechanisms</strong>Point source pollution

Copy link to Point source pollutionReflecting the historical origin of the environmental justice movement, and in part the ubiquity of waste production in modern life, evidence describing inequities in exposure to environmental hazards is particularly rich on hazardous waste and related air, water and land pollution around the world (Walker, 2012[1]). While early research has focussed on the relation between race and income and siting of facilities such as hazardous waste landfills (Been, 1994[65]) and incinerators (Bullard, 1990[66]; Bullard, 1983[8]) in the United States, the scholarship has also expanded over the decades to include an array of point source pollution as well as the impact of a broader matrix of socio-economic factors and geographic characteristics (Sze and London, 2008[67]). For instance, there is now evidence highlighting a host of concerns over environmental burdens placed on immigrants in industrial regions (Viel et al., 2011[68]), rural communities living in proximity to industrial livestock operations (Kravchenko et al., 2018[69]), as well as on the localised effects of transnational activities (Box 2.4).

While there are continued discussions as to why inequitable exposure arises (Box 2.4), there have been some methodological advances in identifying the inequitable exposure to these point source pollution, allowing a shift away from the focus on “unit-hazard coincidence” that compares the demographic makeup of the geographical units that contain hazards (which problematically disregards the exposure of nearby communities just outside of the chosen unit) and measurement of the distance to pollution sources (Banzhaf, Ma and Timmins, 2019[70]). While proximity to sources of pollution continues to be fundamental to understanding the inequitable exposure, more nuanced methodologies incorporate the different physical and chemical properties of pollutants and their dispersion patterns (Cain et al., 2023[71]).

Non-point source pollution

Copy link to Non-point source pollutionIn contrast to point source pollution, non-point source pollution (NPS, also known as diffuse pollution) occurs from multiple pollutants and heterogeneous sources (e.g. households, agricultural runoff) to which individual units of emissions often cannot accurately be attributed (Xepapadeas, 2011[72]).17 The distribution of the impact of water pollution can put disproportionate burden on some communities, reflecting the interconnectedness of water systems. For instance, watersheds18 can act as a conduit for both point and NPS pollution, transferring the costs of upstream pollution onto communities with fewer resources at the end of the watershed (Finewood et al., 2023[73]). Due to the difficulty in attributing the cause of ground and surface water NPS pollution to heterogeneous actors and high transaction costs of coordination (OECD, 2012[74]), it can be challenging to redress inequitable exposure, which manifests in the uneven availability of safe and affordable drinking water (Karasaki et al., 2023[75]).

Box 2.3. Transnational Environmental Considerations

Copy link to Box 2.3. Transnational Environmental ConsiderationsInternational trade and the transnational context in which businesses operate can be relevant considerations in domestic environmental policy making. Environmental justice scholarship has also brought attention to, for instance, trade in toxic waste and material extraction in relation to global economic inequalities, using the term “unequal ecological exchange” (Pellow, 2008[76]; Martinez-Alier, 2001[39]). While relatively nascent, there is a body of research considering the local environmental (e.g. water and energy) and social impact of the rapidly developing import-oriented strategies for the expanding the use of hydrogen produced from renewables (Müller, Tunn and Kalt, 2022[77]; Dillman and Heinonen, 2022[78]).

International trade and environmental effects

Copy link to International trade and environmental effectsInternational trade has conferred innumerable welfare and economic benefits, lifting millions of people out of poverty and providing means and opportunities for sustaining livelihoods across countries (World Bank Group and World Trade Organization, 2015[79]). However, although trade can contribute to environmental sustainability, for instance, by enabling the transfer of clean technologies (Garsous and Worack, 2021[80]), there have also been concerns over its overall environmental impact. Recognising the opportunities and challenges of promoting open trade while mitigating their negative impact, countries have put in place mechanisms to embed environmental considerations in their trade agreements. Examples include the “single entry point”, a public submission mechanism applicable to all EU free trade agreements, through which the public can lodge complaints against breaches of sustainability commitments (European Commission, n.d.[81]). Relatedly, many countries increasingly include environmental provisions in their Regional Trade Agreements (RTAs) negotiated between trade partners (OECD, 2023[82]).

Role of corporations

Copy link to Role of corporationsThe environmental justice movement has also long recognised the impacts of the activities of corporations (Foerster, 2019[83]), with the movements in the United States in the 1990s highlighting the responsibility of multi-national enterprises. Such concerns remain relevant as environmental justice concerns persist, for example, in the context of resource extraction, waste disposal (Martínez Alier, 2020[84]) and chemical safety. The EJAtlas (see also Box 2.2) identifies more than a thousand disputes between communities and corporations (Global Environmental Justice Atlas, 2024[42]).

For instance, the Bhopal gas disaster in India 40 years ago – which occurred during Union Carbide’s operations – killed thousands of people, permanently injured hundreds of thousands more, and is widely regarded as the most grievous chemical industrial disaster to date (Eckerman and Børsen, 2021[85]). Despite dwindling publicity of Bhopal’s aftermath, its socio-economic and environmental legacy endures: females continue to be afflicted by reproductive health problems, children continue to suffer cognitive disabilities, chronic illnesses are widespread, and water and soil remain contaminated (Deb, 2023[86]). There is also evidence of long-term employment effects as those who were in-utero at the time of the disaster are more likely to have a disability that affected their employment, have higher cancer rates, and lower educational attainment (McCord et al., 2023[87]).

These tragedies, and their long-term repercussions, demonstrate the critical impact corporate activities can have upon society, the economy, and the environment. At the same time, these issues highlight the importance on considering how business community, regardless of its size and where it operates, can assume a more active role in preventing adverse impact to the environment. In this context, the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct provides principles and practical actions to identify, prevent and mitigate the adverse impacts of their operations, supply chains and other business relations, while recognising and promoting the positive contributions of businesses (OECD, 2018[88]).

Natural hazards and climate change

Copy link to Natural hazards and climate changeAs the impact of climate change becomes increasingly visible, research has also brought attention to the inequitable distribution of environmental risks (Collins and Grineski, 2018[89]). As devastating events such as Hurricane Katrina in 2005 vividly demonstrate, natural hazards affect communities differently over their entire cycle, from initial impact, evacuation, and post-disaster recovery (Bullard and Wright, 2018[90]). A large body of studies has documented disproportionate impact of natural hazards across communities and individuals. For instance, there is research evidencing the uneven long-term exposure to wildfire-induced air pollution for Indigenous communities (Casey et al., 2024[91]), as well as the significantly higher mortality rate of the people with disabilities during natural disasters (Stein and Stein, 2022[92]).19 However, the fact that the proximity to risk-prone neighbourhoods brings both environmental risks and amenities (e.g. access to sea and river) defies simplistic characterisation of vulnerabilities in terms of spatial dimension (Collins and Grineski, 2018[89]).

Importantly, interlinkages between man-made environmental risks and climate risks are increasingly recognised. Industrial accidents triggered by disruptive extreme weather events are becoming a greater concern, exposing surrounding communities to acute risks (Johnston and Cushing, 2020[93]). Even after closure of industrial facilities, water and soil contaminants from legacy facilities can still be redistributed by flooding and hurricane, giving rise to new inequities at the intersection of legacy pollution and the increase in the severity and frequency of natural hazards (Marlow, Elliott and Frickel, 2022[94]). These concerns attest to the growing challenge of rectifying persisting issues from the past while mitigating the anticipated climate impact in the future.

Unevenly available adaptive mechanisms

Copy link to Unevenly available adaptive mechanismsCompounding inequitable exposure, financial constraints can prevent vulnerable communities from adapting to pollutants and hazards by relocating or purchasing mitigating products or technologies (Ezell et al., 2021[95]; Boyd, 2023[96]). Adaptive mechanisms to unsafe drinking water, for instance, incur additional financial burdens from buying bottled water and investing in costly filtering system – choices that may be unavailable to low-income groups – as well as psychological distress (Karasaki et al., 2023[75]). Another example is the financial constraints to adapt and cope with climate impact such as increasingly frequent heat waves, with some research finding that energy expenditure is less responsive to extreme temperature in low-income households, suggesting the differential adaptive capacity (Doremus, Jacqz and Johnston, 2022[97]).

Even when policy measures are available to remedy inequitable exposure, empirical research suggests that vulnerable communities’ take up and participation can be hindered by various barriers in practice. In the case of lead service line inspection and replacement programme for safe drinking water in the United States, various non-financial barriers including lack of trust in water systems, lack of knowledge and inconvenience of scheduling appointments hindered participation in the programme (Klemick et al., 2024[98]). Financial barriers can also limit participation, particularly in less affluent areas in which cost burdens fall on users due to the utility providers’ inability to access credits and public funds, making participation cost prohibitive for many low-income groups (Klemick et al., 2024[98]; Allaire and Acquah, 2022[99]).

Box 2.4. Mechanisms underlying disproportionate burden and proximity to sources of environmental hazards

Copy link to Box 2.4. Mechanisms underlying disproportionate burden and proximity to sources of environmental hazardsWhile observational studies documenting the linkages between environmental and social outcomes help draw attention to environmental justice concerns, evidence exploring why they occur is relatively limited (Knoble and Yu, 2023[100]). Establishing and explaining causality has proved challenging, particularly as the mobility of people and their choices in residential location necessitates longitudinal analysis that capture the demographic makeup before and after the siting decision (Mohai and Saha, 2015[101]).

Existing research has reached diverse conclusions (Mohai, Pellow and Roberts, 2009[14]). Some inequitable exposure to hazardous waste may arise, for example, because of discriminatory intent of siting decisions of facilities. For instance, (Bullard, 1990[66]) has found that siting of hazardous facilities was motivated by racial discrimination against African American communities in the United States. Relatedly, decisions can reflect sociopolitical considerations, with firms selecting “path of least resistance” where communities are least equipped to mobilise action towards opposition (Collins, Munoz and Jaja, 2016[102]). However, studies have also found that firms make their initial siting choices based on conventional economic costs, including access to low-cost labour and land (Wolverton, 2009[103]). Nonetheless, even when the decisions are not intentionally discriminatory, they can still disproportionately affect socio-economically disadvantaged communities over time through market dynamics by lowering the land and property value of the surrounding areas (Mohai, Pellow and Roberts, 2009[14]). These dynamics driving firm and residential sorting are also likely to interact (Cain et al., 2023[71]).

The various drivers behind why some communities are overrepresented in areas in proximity to hazards suggests that these inequities need to be assessed at multiple scales and over time, with involvement of affected communities; otherwise, their broad generalisation can mask particular vulnerabilities and reinforce their lack of recognition (Walker, 2012[1]).

Environmental amenities

Copy link to Environmental amenitiesEmerging literature also extends the discussion to access to environmental amenities (Agyeman et al., 2016[52]), such as green spaces, which can promote positive physical and mental health (James et al., 2015[104]). It can also attenuate harm from runoff, extreme temperature, and air pollution (Franchini and Mannucci, 2018[105]). There is substantial evidence suggesting that the access to environmental amenities is also highly uneven (Watkins and Gerrish, 2018[106]). In particular, there is a wealth of studies highlighting the inequitable access to green and blue space in urban areas. Research finds that socio-economic factors and characteristics – including income, race and education – influence access to (Dai, 2011[107]) and quality of the green (Fossa et al., 2023[108]) and blue space (Thornhill et al., 2022[109]). It is also important to highlight that the value communities assign to environmental amenities are relative, and the unmet needs can also raise concerns over environmental justice (Walker, 2012[1]).

There is a growing recognition that there is more to environmental amenities beyond the enjoyment and access to clean and safe natural environment, with some conceptualisation broadening the notion to consider the built environment such as uneven access to electric vehicles (EVs) charging infrastructure. For instance, inequitable access can arise along two dimensions of affordability and ownership of EVs and accessibility of charging infrastructure, which can become self-perpetuating as uneven uptake of EVs may result in differential investments into the infrastructure (Hopkins et al., 2023[110]).

Exposure pathways and their environmental justice implications

Copy link to <strong>Exposure pathways and their environmental justice implications </strong>Many toxic contaminants have relatively established exposure pathways, depicting a route from sources of pollution and their receptor population (Burger and Gochfeld, 2011[111]). However, some of the atypical pathways can be inadvertently overlooked in exposure science and environmental epidemiology, hindering proactive policy response. These exposure pathways could relate to cultural and religious practice of Indigenous communities including the use of certain medicines and traditional lifestyles centred around outdoors activities and diet (ibid). For example, studies from Brazil and Canada found that Indigenous Peoples whose diet is traditionally rich in fish and marine mammal meat were more exposed to mercury poisoning (Chan and Receveur, 2000[112]; Hacon et al., 2020[113]).

Another oft-overlooked exposure pathway is consumption of packaged and canned food and the use of consumer products. For instance, low-income groups might be disproportionately exposed to chemicals20 used in food packaging for more affordable processed food, as well as canned food with long shelf lives used for food assistance (Ruiz et al., 2018[114]). Research has also examined the exposure pathways through consumer products, such as personal care products that disproportionately affect women and intersect with other categories including race21 (Zota and Shamasunder, 2017[115]; Collins et al., 2023[116]). More broadly, an exposure pathway can also be structured by the differential indoor environment, such as size and quality of dwellings, which mediates the outdoor and the indoor environment and influences exposure to air and lead pollution (Adamkiewicz et al., 2011[117]); an important consideration given that people globally spend around 85-90% of their lifespan in indoor spaces (Mannan and Al-Ghamdi, 2021[118]).

Furthermore, there is growing evidence of the relation between occupation and additional exposure pathways. For instance, informal waste collectors resorting to burning of plastics in open pits due to lack of waste management facilities are exposed to health threatening dioxin (United Nations Environment Programme, 2021[119]). Furthermore, “take-home” exposure pathways through which workers bring residues on their clothes, shoes and skin into home can expose other members of the households to toxic contaminants (Hyland and Laribi, 2017[120]). Children are particularly more exposed due to physiological and behavioural susceptibility including the propensity to spend more time on the ground where dust-borne residues settle (ibid).

Limited data availability and lack of visibility can hinder identification of these exposure pathways. Monitoring can also be hindered due to high costs for installation and maintenance of new devices and inadequate data collection, potentially concealing true extent of pollution (United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2023[121]). In this context, the term “popular epidemiology” has been coined to suggest that lay knowledge and lived experience of exposure to toxic pollution can lead to identify hitherto unacknowledged exposure pathways (Brown, 1997[122]). Active engagement with concerned communities, for instance, through citizen science,22 helps access local expert knowledge of the communities (Brulle and Pellow, 2006[123]) and elucidate overlooked linkages between the environment and health (Johnston and Cushing, 2020[93]). For example, in Ecuador, a popular epidemiology study conducted in cooperation with rural and Indigenous communities helped establish the links between oil contamination in the region and adverse health impacts, evidence of which was used in legal proceedings against the corporation responsible for the oil extraction (San Sebastián and Hurtig, 2005[124]). They can also complement the traditional environmental monitoring.

Environmental justice and health

Copy link to <strong>Environmental justice and health </strong>There is a widespread recognition that declining environmental quality adversely affects health outcomes. It is estimated that modifiable environmental risk factors have accounted for almost quarter of deaths worldwide in 2012 (WHO, 2016[125]). In particular, there is mounting evidence documenting air pollution and its links to non-communicable diseases, particularly cardiovascular and respiratory diseases (Prüss-Ustün et al., 2019[126]). Importantly, differential exposure, lack of viable options for adaptation, and unacknowledged pathways interact with other socio-economic determinants of health, which can together exacerbate existing health inequities.23

Available evidence corroborates the links between the differential availability and quality of the environment and inequitable health outcomes to a wide range of socio-economic variables and categories including income, race, Indigeneity, age and sex. For instance, exposure to environmental hazards can contribute to short-term and long-term maternal health impacts (e.g. miscarriage, higher risk of breast cancer) (Boyles et al., 2021[127]). Disadvantaged women might thus face a “double jeopardy” posed by chronic stressors and exposure to environmental hazards (Morello-Frosch and Shenassa, 2006[128]). Exposure to environmental hazards can also have different impacts for different age groups. For example, children are known to be more susceptible to negative health outcomes of such an exposure due to their biological vulnerabilities (e.g. greater consumption of toxins relative to body weight, immature metabolic pathways) and age-related exposure patterns (e.g. playing close to the floor and the ground and hand-to-mouth behaviours) (Landrigan, Rauh and Galvez, 2010[129]).

Exposure to environmental harms alone is rarely the sole determinant of adverse health outcomes (United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2023[130]). Holistically and accurately attributing the impact of the environmental hazards to health therefore requires careful consideration of other determinants of the impact of the environment on health. Intrinsic factors, biological traits and pre-existing health conditions make some individuals more susceptible to environmental risks. For instance, exposure to environmental hazards, notably air pollution, can exacerbate asthma symptoms. Consequently, environmental exposure is estimated to account for 44% of asthma’s disease burden (WHO, 2016[125]).24

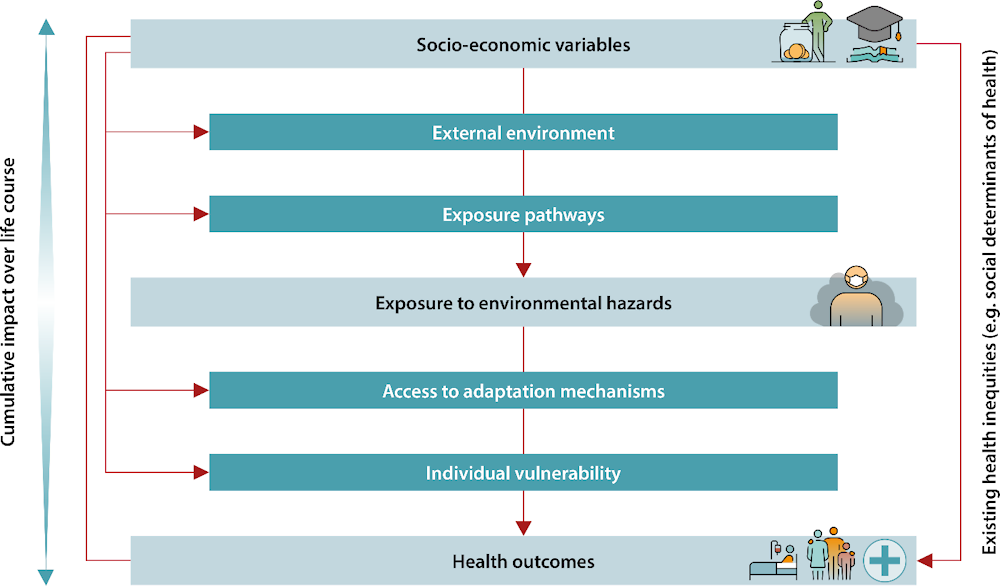

Importantly, socioeconomic characteristics of individuals, community and health outcomes interact in a multitude of complex and cumulative ways, with research demonstrating that different types of environmental harms tend to cluster in the same community (Banzhaf, Ma and Timmins, 2019[9]) (Figure 2.2).25 For instance, poor residential condition of low-income groups and exposure to indoor pollution can lead to risks to compromised respiratory systems, which in turn makes them more vulnerable to outdoor air pollution (Solomon et al., 2016[131]). Other variables linked to socio-economic status, such as location of their residence exposed to higher traffic emissions from mobile sources (e.g. vehicles) and inability to move out of the area due to financial constraints, further disproportionately expose communities living in the area to greater level of air pollution to the detriment of their health (Barnes, Chatterton and Longhurst, 2019[132]; Park and Kwan, 2020[133]).

The concept of “exposome”, encompassing life-course environmental exposures from prenatal period can help uncover these linkages, distinguishing between individual health characteristics, specific external (e.g. environmental pollutants and chemical contaminants) and general external (e.g. social determinants of health) environment over life course (Wild, 2012[134]). Lifetime cumulative impacts is important to consider given the inequities at birth or in-utero can have lasting consequences for welfare and gaps in opportunities between children based on family backgrounds (Currie, 2011[135]). However, the dynamic nature of exposome and the number of significant challenges that make holistic assessments time-and data-intensive, due to the need to deploy of multiple tools, technologies and large sample sizes to disentangle the different correlated exposures and their interactions (Siroux, Agier and Slama, 2016[136]).

Figure 2.2. Interactions of socio-economic variables, environment and health

Copy link to Figure 2.2. Interactions of socio-economic variables, environment and health

Source: Adapted from (Wakefield and Baxter, 2010[137]) with authors’ edits based on (Siroux, Agier and Slama, 2016[136]) and (Burger and Gochfeld, 2011[111]).

2.3.2. Inequitable distribution of the costs and benefits of environmental policy

Copy link to 2.3.2. Inequitable distribution of the costs and benefits of environmental policyAnother key substantive issue is inequitable distribution of the costs and benefits of environmental policy. While it may seem intuitive that environmental improvements would benefit society at large, empirical literature points to the critical importance of considering the costs of policies. Similarly, improvements in overall environmental quality do not necessarily guarantee that the benefits are enjoyed by all segments of the population (Mitchell, 2019[18]) or that the relative gaps in environmental quality experienced are narrowed; indeed, a recent study suggests that while air quality has improved overall in the United States, the gap between the most and least polluted areas remain relatively stable (Colmer et al., 2020[138]). The inequitable distribution of costs and benefits of policies might be additionally exacerbated by insufficient monitoring and enforcement efforts, potentially causing disparities in compliance with environmental regulation.

In some cases, benefits of environmental policy might come at the cost of the welfare of some communities. Policies promoting adoption of electric vehicles to decarbonise transport can bring environmental benefits for the urban population, but this may reduce the air quality for the population living near power plants in rural areas (Holland et al., 2019[139]). Preventing the disadvantaged groups from bearing the disproportionate burden of policy is critical for ensuring inclusivity, but also for sustaining public support for environmental and climate policy more broadly (Mackie and Haščič, 2019[140]).

Existing empirical evidence suggests that environmental policy will have heterogeneous impacts at different levels of aggregation (OECD, 2021[141]). Consideration of distribution of the costs and benefits of environmental policy is rising in importance, as countries engage in profound social and economic transformation to address environmental challenges. The literature finds inequitable outcomes of environmental policy can arise through: (i) spatial effects, (ii) impact on labour markets and (iii) impact on household income. While there is an expanding body of literature, including studies that capture the dynamic effects of the economic transformation through modelling analysis (e.g. (Borgonovi et al., 2023[142])), it remains an important area that warrants further research to improve the design of environmental policy.

Spatial effects

Copy link to <strong>Spatial effects </strong>Measures seeking to address environmental justice concerns, such as geographically circumscribed regulations, cleaning up the most polluted neighbourhoods or areas, and improve access to amenities (e.g. brownfield development) can improve the environmental quality for the communities facing disproportionate exposure to environmental hazards (Currie, Voorheis and Walker, 2023[143]). However, they can also indirectly bring negative distributional consequences if they are not thoughtfully designed. For instance, improved environmental quality can drive up the market value of houses in the affected areas. Subsequently, environmental improvements may attract higher income households while crowding out certain socio-economic groups, including low-income households and racialised minorities (Melstrom et al., 2022[144]); an unintended consequence documented in many neighbourhoods around the world (Wolch, Byrne and Newell, 2014[145]). This can occur both through demand and supply-side mechanisms, with housing demand from those who are more willing and able to pay more for higher environmental quality increasing the house prices and rents, as well as inelastic housing supply exacerbating the exclusionary dynamics (OECD, 2022[146]).26

However, there are important nuances for these spatial effects. The literature typically distinguishes between the impacts on homeowners and renters, with research reaching diverging conclusions. There is evidence demonstrating that the benefits accrue to homeowners in the cleaned-up areas, while resulting in rent increase that can drive those less able to pay to less expensive neighbourhoods (Sieg et al., 2004[147]). Others find that the rents are less responsive to improvements in environmental quality (Grainger, 2012[148]), implying progressive impact of environmental policy.27 While less recognised, policies that preserve environmental amenities can also bring unintended consequences in in nearby areas. For instance, excessive focus on preserving abundant green space in urban areas can trigger leapfrog development in peri-urban areas, resulting in higher environmental damages (OECD, 2022[146]).

The risk of environmental policy leading to inequitable spatial distribution of benefits (e.g. reduced pollution) also warrants consideration. As instruments such as the emissions trading systems induce firms facing low abatement costs to reduce more emissions, benefits might accrue disproportionately to the communities located near or downwind of these firms (Cain et al., 2023[71]). While much of the existing empirical studies on the impact of market-based policies suggest that this has not been the case to date (Fowlie, Holland and Mansur, 2011[149]; Shapiro and Walker, 2021[10]), there remain ambiguities relating to the spatial distribution of abatement costs and the communities. For instance, some research that consider the non-uniform pollution dispersion finds evidence of disproportionate benefits accruing to high income areas (Grainger and Ruangmas, 2018[150]). Importantly, the risks for uneven distribution of benefits also need to be considered in relation to the aggregate magnitude of environmental improvements across different types of policy instruments (Vona, 2021[151]).

Labour market implications

Copy link to <strong>Labour market implications </strong>Another inequitable distribution of costs could arise from the ramifications of environmental policy for the labour market. The literature suggests that environmental policy induces the substitution from labour to (labour-saving) technology, particularly in the long term (ibid). Adoption of cleaner, capital-intensive technologies in response to stringent environmental policy can result in reduced demand for labour and lower wages, disproportionately affecting low-skilled and low-paid workers (Marin and Vona, 2019[152]; Bento, 2013[153]). While empirical evidence suggests the magnitude of this impact is relatively modest, it can compound the uneven distribution of wealth to create further vulnerabilities, as the wages are the main source of income for the poorest and the most disadvantaged.

As the concept of just transition helps illustrate (International Labour Organization, 2016[59]), there are paramount concerns over the disruptive implications of the climate transition for employment opportunities, heightening the sense of unfairness among affected communities. While the transition to more environmentally sustainable economies is a global macroeconomic trend, it will have inherently localised impact, which may be particularly acutely felt in emission-intensive sectors as well as the regions with high concentration of these industries (OECD, 2023[154]). Oft-cited examples are concentrated job losses in coal industry, but they have broader economic implications for hosting communities and the local economy through reduced consumption and weakened local tax base (Carley and Konisky, 2020[155]).

Importantly, environmental policy interacts with broader social and macroeconomic trends such as technological transformation. Changes in the skillsets28 demanded in the labour market over the course of the green and digital (“twin”) transition, as well as existing inequities in educational attainment and access to opportunities for skill development and retraining can give rise to new forms of vulnerabilities (OECD, 2023[156]). These impacts further highlight the need for reskilling and upskilling policies to ensure the transition to a carbon neutral economy does not create or compound new vulnerabilities (Borgonovi et al., 2023[142]).

Impact on household income

Copy link to <strong>Impact on household income</strong>There is a wealth of studies exploring the potential regressivity of environmental policy, highlighting the risks of low-income households bearing disproportionate cost of environmental policy. For instance, higher energy price resulting from environmental policy may affect low income households more, who spend disproportionate portion of their income on energy bills (Bento, 2013[153]).29 The regressivity impact is further amplified by general tendency of low-income people to live in energy inefficient dwellings and own inefficient appliances across countries (e.g. (Schleich, 2019[157])). While the regressivity of policy varies by the type of fuel and by country, existing evidence underscores the importance of choice of instruments and their design.

Typically, market-based policies instruments are perceived to be more regressive than regulations and standards due to the visibility of their burden (Mackie and Haščič, 2019[140]). However, the evidence suggests that the opposite can be true, particularly as regulations and standards do not generate revenues that can be redistributed to alleviate the burden on low-income households. The burden from market-based instruments such as an energy tax can also vary within income groups, compounding the challenge of policy sequencing and design of the alleviating measures (Pizer and Sexton, 2019[158]). For instance, low-income groups in rural areas with insufficient access to public transport may bear greater burdens of taxes on transport fuels than those in urban areas. While distributional implications of regulations remain relatively less explored in the literature, studies on fuel standards (Davis and Knittel, 2019[159]) and building energy codes (Bruegge, Deryugina and Myers, 2019[160]) find some evidence of regressive impacts.

A growing body of empirical literature suggests patterns of uneven distribution of benefits of environmental policies. Subsidies that uniformly lower the cost of investment in low-carbon solutions may disproportionately benefit high-income households. Home investments such as improved insulation and solar panels tend to be made by homeowners and higher-income households, who face lower credit constraints (Ameli and Brandt, 2014[161]). Similarly, electric vehicles subsidies can also have significant distributional effects as higher-income households are more likely to be able to afford them (Borenstein and Davis, 2016[162]). A better understanding of the net impact of incidence of costs and benefits, and how it is distributed across different segments of the population, is critical for informing the better design of environmental policy (Bento, 2013[153]).

2.3.3. Barriers to access to information, participation in decision-making and legal recourse

Copy link to 2.3.3. Barriers to access to information, participation in decision-making and legal recourseAs the evidence documenting inequitable exposure to environmental harms demonstrates, processes (access to participation, information, and legal recourse, and the lack thereof) are central to understanding how the inequitable distributional outcomes are derived. These procedural rights can be considered mutually reinforcing “access rights” that underpin procedural environmental justice (Gellers and Jeffords, 2018[163]).

Barriers to access to information

Copy link to <strong>Barriers to access to information </strong>While many governments commit to greater accessibility of information on the state of the environment, some barriers to access appear to persist. Importantly, availability of environmental information does not necessarily translate into the effective use of information. For instance, technical language often used in information on environmental conditions might limit the scope of how the communities can use the information intended to serve the purpose of enhancing their resilience (Mabon, 2020[164]). As recognised in the Escazú Agreement, marginalised communities may experience challenges regarding literacy and linguistic isolation, or lack knowledge on how to formulate requests for information (Barritt, 2020[49]).

With studies finding that the effective use of environmental information depends on socio-economic factors including educational attainment (Shapiro, 2005[165]), simply making more information available without adequate consideration of the barriers to the use of information can inadvertently amplify the adverse outcomes for vulnerable communities. For instance, mandated disclosure of pollution source to empower vulnerable communities can have the unintended impact of incentivising facilities to relocate to low-income areas (Wang et al., 2021[166]). In this context, the OECD Council Recommendation on Environmental Information and Reporting notes the need to “support educational efforts towards enabling the public to make use of available environmental information” (OECD, 2022[167]).

The nature of the information itself, its scale, scope and relevance for the community in question are also key to determining its eventual use. Historically, environmental information made available to the public has often been issue-specific, with countries commonly publishing the data on environmental pollution and the chemical releases documented in an inventory (Haklay, 2003[168]). While data disclosure is essential for facilitating and enabling academic research, vulnerable communities may need more processed and interpreted information; for instance, the primary interest of those who experience asthma is whether they will likely suffer an attack, rather than the level of ground-level air pollution (ibid).

Barriers to access to participation in decision making

Copy link to <strong>Barriers to access to participation in decision making</strong>Addressing barriers to participation in environmental decision-making is critical for alleviating inequitable environmental burdens on vulnerable communities (Freudenberg, Pastor and Israel, 2011[169]). Even when the right to participate is legally protected, there remains an inherent flexibility in the modalities and forms participation take in practice (Barritt, 2020[49]). Modalities of participatory processes can also constitute barriers to meaningful participation. Formal policy consultations, while laudable in intent, may not always lend themselves well to consideration of the breadth of views (OECD, 2023[170]). There appears to be a sense of disillusionment in the processes, with over 40% of people in OECD countries stating that governments are unlikely to adopt inputs from public consultations (ibid).

Even if opportunities are available and formally open for anyone to participate, some communities, including those less equipped with resources (e.g. language, time, internet connection), can still be excluded from participatory opportunities (Karner et al., 2018[171]). Without adequate recognition of existing barriers and biases, increasing participatory opportunities might reinforce existing inequalities (ibid). There is a risk of self-selection bias, with open calls for participants typically attracting participants who are more likely to be older, male, well-educated, affluent and urban (OECD, 2022[172]). Past examples of community engagement suggest that poorly designed participatory processes can even leave communities frustrated and discourage them from further participation (Ruano-Chamorro, Gurney and Cinner, 2022[173]).

While lack of meaningful participation in environmental decision-making is problematic in its own right, it can also stall progress for the transition to more environmentally sustainable economies. For instance, while the public generally supports renewables, this has not always translated into support for the development of renewable energy infrastructure in their communities (Wolsink, 2007[174]), with patterns of public dissatisfaction about the processes of decision-making observed across the world (van de Grift and Cuppen, 2022[175]). While there is no conclusive evidence explaining the seemingly conflicting patterns of broad public support and strong local oppositions (Carley et al., 2020[176]), lack of adequate participation in decision-making is often highlighted as one of the key drivers of opposition (Suškevičs et al., 2019[177]).30 Mechanistic application of participation as a bureaucratic process and a validation exercise of the decisions that are already made may not adequately substantiate the right to participation (Armeni, 2016[178]; Wesselink et al., 2011[179]). Designing participatory mechanisms that ensure communities can meaningfully affect the outcomes might generate greater support, which in turn can propel the transition (Walker and Baxter, 2017[180]).

Barriers to access to legal recourse

Copy link to <strong>Barriers to access to legal recourse </strong>Legal recourse has also been recognised as an important enabling factor for resolution of conflicts and protection of rights for marginalised communities (Scheidel et al., 2020[181]). Although relatively little is understood about the barriers to access to justice in environmental matters, it is often considered the procedural pillar that has historically lagged behind across countries (Mauerhofer, 2016[182]). The wider literature on access to justice also suggests that availability and quality of legal recourse is influenced by social and economic variables (OECD and Open Society Foundations, 2016[183]). In particular, costs of obtaining legal representation can also be prohibitive, adding to opportunity costs (e.g. missed time at work and care-giving responsibilities). Across most countries, people living in poverty face greater barriers to access to justice although they are more likely to be in need of legal assistance (World Justice Project, 2023[184]); a problem often compounded further by the shortage of personnel and resources for public legal assistance (McDonald, 2021[185]). Furthermore, existing studies suggest that many do not consider the issues they face as legal issues or actively seek and identify legal remedies available (OECD, 2019[186]), which may reflect limited legal knowledge as well as broader lack of trust in courts and legal system (OECD, 2022[187]).

References

[117] Adamkiewicz, G. et al. (2011), “Moving environmental justice indoors: Understanding structural influences on residential exposure patterns in low-income communities”, American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 101/SUPPL. 1, https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300119.

[54] Agyeman, J., R. Bullard and B. Evans (2002), “Exploring the Nexus: Bringing together sustainability, environmental justice and equity”, Space and Polity, Vol. 6/1, https://doi.org/10.1080/13562570220137907.

[52] Agyeman, J. et al. (2016), Trends and Directions in Environmental Justice: From Inequity to Everyday Life, Community, and Just Sustainabilities, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-110615-090052.

[40] Akese, G. and P. Little (2018), “Electronic Waste and the Environmental Justice Challenge in Agbogbloshie”, Environmental Justice, Vol. 11/2, https://doi.org/10.1089/env.2017.0039.

[37] Aldinger, P. (2013), “Addressing environmental justice concerns in developing countries: Mining in Nigeria, Uganda and Ghana”, Geo. Int’l Envtl. L. Rev., Vol. 26.

[99] Allaire, M. and S. Acquah (2022), “Disparities in drinking water compliance: Implications for incorporating equity into regulatory practices”, AWWA Water Science, Vol. 4/2, https://doi.org/10.1002/aws2.1274.

[161] Ameli, N. and N. Brandt (2014), “Determinants of Households’ Investment in Energy Efficiency and Renewables: Evidence from the OECD Survey on Household Environmental Behaviour and Attitudes”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1165, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5jxwtlchggzn-en.

[51] Andrade-Goffe, D., C. Excell and A. Sanhueza (2023), The Escazú Agreement: Seeking Rights to Information, Participation, and Justice for the Most Vulnerable in Latin America and the Caribbean, https://www.wri.org/research/escazu-agreement-seeking-rights-information-participation-and-justice-most-vulnerable#:~:text=The%20Escaz%C3%BA%20Agreement%20is%20the,and%20environmental%20human%20rights%20defenders.

[178] Armeni, C. (2016), “Participation in environmental decision-making: Reflecting on planning and community benefits for major wind farms”, Journal of Environmental Law, Vol. 28/3, https://doi.org/10.1093/jel/eqw021.

[194] Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Isander Studies (n.d.), Welcome to Country, https://aiatsis.gov.au/explore/welcome-country (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[38] Banza, C. et al. (2009), “High human exposure to cobalt and other metals in Katanga, a mining area of the Democratic Republic of Congo”, Environmental Research, Vol. 109/6, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2009.04.012.

[9] Banzhaf, H., L. Ma and C. Timmins (2019), Environmental Justice: Establishing Causal Relationships, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-resource-100518-094131.

[70] Banzhaf, S., L. Ma and C. Timmins (2019), “Environmental justice: The economics of race, place, and pollution”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 33/1, https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.33.1.185.

[132] Barnes, J., T. Chatterton and J. Longhurst (2019), “Emissions vs exposure: Increasing injustice from road traffic-related air pollution in the United Kingdom”, Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, Vol. 73, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2019.05.012.

[49] Barritt, E. (2020), “Global values, transnational expression: from Aarhus to Escazú”, in Research Handbook on Transnational Environmental Law, https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788119634.00022.

[65] Been, V. (1994), “Locally Undesirable Land Uses in Minority Neighborhoods: Disproportionate Siting or Market Dynamics?”, Yale Law Journal, Vol. 103/6, pp. 1383-1422, https://www.jstor.org/stable/797089.

[19] Bell, D. and J. Carrick (2017), “Procedural environmental justice”, in The Routledge Handbook of Environmental Justice.

[33] Bell, K. (2014), Achieving environmental justice: A cross-national analysis.

[153] Bento, A. (2013), Equity impacts of environmental policy, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-resource-091912-151925.

[193] Bento, A., M. Freedman and C. Lang (2015), “Who benefits from environmental regulation? Evidence from the clean air act amendments”, Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 97/3, https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00493.

[162] Borenstein, S. and L. Davis (2016), “The distributional effects of US clean energy tax credits”, Tax Policy and the Economy, Vol. 30/1, https://doi.org/10.1086/685597.

[142] Borgonovi, F. et al. (2023), “The effects of the EU Fit for 55 package on labour markets and the demand for skills”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers.

[96] Boyd, D. (2023), Statement at the conclusion of country visit to Chile, https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/documents/issues/environment/srenvironment/eom-statement-Chile-12-May-2023-EN.pdf.

[127] Boyles, A. et al. (2021), “Environmental Factors Involved in Maternal Morbidity and Mortality”, Journal of Women’s Health, Vol. 30/2, https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2020.8855.

[122] Brown, P. (1997), “Popular Epidemiology Revisited”, Current Sociology, Vol. 45/3, https://doi.org/10.1177/001139297045003008.

[53] Bruckner, B. et al. (2022), “Impacts of poverty alleviation on national and global carbon emissions”, Nature Sustainability, Vol. 5/4, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-021-00842-z.

[160] Bruegge, C., T. Deryugina and E. Myers (2019), “The distributional effects of building energy codes”, Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists, Vol. 6/S1, https://doi.org/10.1086/701189.

[123] Brulle, R. and D. Pellow (2006), Environmental justice: Human health and environmental inequalities, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102124.

[66] Bullard, R. (1990), Dumping in Dixie: Race, class, and environmental quality, Boulder, Colo: Westview Press.

[8] Bullard, R. (1983), “Solid Waste Sites and the Black Houston Community”, Sociological Inquiry, Vol. 53/2-3, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-682X.1983.tb00037.x.

[90] Bullard, R. and B. Wright (2018), “Race, place, and the environment in post-Katrina New Orleans”, in Race, Place, and Environmental Justice after Hurricane Katrina: Struggles to Reclaim, Rebuild, and Revitalize New Orleans and the Gulf Coast, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429497858.

[111] Burger, J. and M. Gochfeld (2011), “Conceptual environmental justice model for evaluating chemical pathways of exposure in low-income, minority, Native American, and other unique exposure populations”, American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 101/SUPPL. 1, https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2010.300077.