This chapter turns to the specific tools and policy measures through which countries identify, assess, and address environmental justice concerns, drawing on insights from the OECD Environmental Justice Survey. It first presents the findings on how countries identify communities, groups and regions vulnerable to environmental justice concerns. The chapter then outlines how these concerns are assessed, illustrating the variety of qualitative and quantitative tools and methodologies available. Next, various policy measures aimed at furthering environmental justice are explored. Lastly, this chapter points to the unifying challenges countries face in assessing and addressing environmental concerns.

Environmental Justice

4. Identifying, assessing, and addressing environmental justice concerns

Copy link to 4. Identifying, assessing, and addressing environmental justice concernsAbstract

4.1. Identifying environmental justice concerns

Copy link to 4.1. Identifying environmental justice concernsExisting literature on environmental justice suggests that certain groups and communities are or might become, disproportionately exposed to environmental hazards, experience adverse health impacts, or impacted by environmental policies. These communities and groups may also face specific barriers to participation in environmental decision making, access to environmental information, as well as legal recourse. This section explores whether and how countries identify communities and groups at risk of environmental injustice, based on the following set of questions:

Whether or not countries identify specific communities and groups at risk;

What characteristics are considered relevant when identifying communities and groups at risk and what data are used to identify them;

Whether there are regions where certain communities and groups may be particularly exposed to environmental justice concerns.

4.1.1. Identifying communities and groups at risk

Copy link to 4.1.1. Identifying communities and groups at riskThe overwhelming majority of countries identify communities and groups at risk; although about half of them do so generally, rather than specifically in the context of the environment and environmental policies. The categories that are considered to identify groups and communities at risk are wide-ranging and relate both to demographic (e.g. age, gender, race), and spatial (e.g. type of municipality, proximity to certain environmental hazards) features.

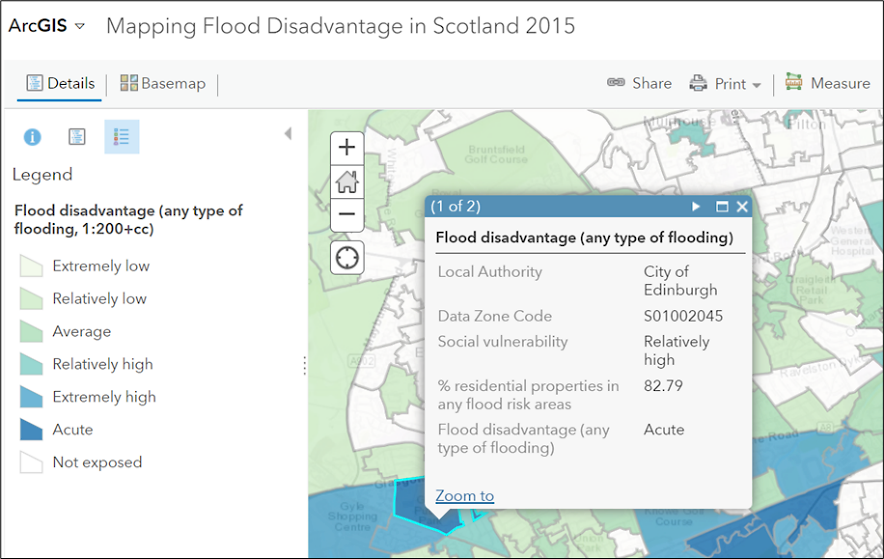

There are certain characteristics that are considered relevant by most countries, including lack of access to key public services (Figure 4.1). This may reflect the fundamental importance of accessible public services as a precondition for ensuring equity. For instance, lack of access to health care faced by communities in remote areas, such as First Nations people in Australia, might prevent them from seeking medical remedies to exposure to environmental extremes such as heatwaves or floods (Mathew et al., 2023[1]). Perhaps unsurprisingly, given that many studies suggest inequitable environmental outcomes often coincide with economic deprivation, level of income is also a characteristic that is widely considered across many countries. Age is also commonly identified as a relevant characteristic. Attention given to age can be attributed to the unique vulnerabilities of children and the elderly to environmental hazards such as air pollution (Simoni et al., 2015[2]; Landrigan, Rauh and Galvez, 2010[3]).1

Moreover, lack of access to environmental amenities, health and disability as well as occupational sector are considered across countries. For instance, research clearly suggests that environmental amenities play an important role in attenuating environmental hazards (Massimo and Mannucci, 2018[4]). Interestingly, gender is also identified in over half of countries. The literature highlights that some gender-specific challenges, including the effects of exposure to chemicals on maternal health, may also overlap with environmental justice concerns (Giudice et al., 2021[5]; Butler, Gripper and Linos, 2022[6]).

Figure 4.1. Characteristics relevant to identifying communities and groups at risk

Copy link to Figure 4.1. Characteristics relevant to identifying communities and groups at risk

Note: Based on 22 responses. Respondents were asked to select all that apply and were invited to share other characteristics that are not available on the pre-defined list; six respondents shared such characteristics. Three characteristics are not displayed as they were selected least often; these are: Migrant status, Minority language and National origin. The data is presented from left to right in order of the highest number of countries selecting that a given characteristic is considered. While Portugal did not provide a response to this question, Japan and Estonia stated that they do not identify communities or groups at risk. The European Commission noted that all of the characteristics can be assessed in a proportionate manner.

Source: The OECD Environmental Justice Survey.

Fewer countries consider migrant status, minority language or national origin to be relevant when identifying communities and groups at risk which could be partly due to their different demographic compositions across countries. Another reason might be the lack of relevant data.2 Nonetheless, existing research suggests that these characteristics can intersect in complex ways to create distinct vulnerabilities. The intersectionality of various characteristics in relation to environmental justice is recognised, for instance, in Brazil as described in Box 4.1.

Box 4.1. Brazilian Committee to monitor the Black Amazon and Combat Environmental Racism

Copy link to Box 4.1. Brazilian Committee to monitor the Black Amazon and Combat Environmental RacismDesk research undertaken to complement the responses to the OECD Survey highlights other relevant initiatives beyond those mentioned by the survey respondents. For example, in Brazil, recognition of the link between racial inequality and environmental justice concerns prompted the use of the term “environmental racism” by policymakers, subsequently leading to the development of a dedicated initiative. The Committee to monitor the Black Amazon and Combat Environmental Racism was established in August 2023 in partnership between the Ministry of Racial Equality and the Ministry of Environment and Climate Change. The Committee’s objective is to propose measures to combat environmental racism in the Amazon.

In her speech, the Minister of Racial Equality, Anielle Franco, acknowledged the intersectional character of the issue, also mentioning factors such as income and Indigeneity:

"No measure will be fully effective until we think about solutions by putting the most vulnerable populations at the centre, mostly poor and black people, both in rural areas and in urban centres (…) Putting our traditional peoples, quilombola communities, terreiro peoples at the forefront of protecting the Amazon is a duty not only of the Brazilian government, but of the world. It will only be possible to achieve environmental justice with racial justice".

As environmental justice concerns cut across issues across policy domains, this inter-ministerial co-operation exemplifies how local context and challenges – advancing racial equality in Brazil – can guide the involvement of different actors in initiatives to promote environmental justice.

Countries deploying direct approaches to environmental justice (“legal” and “policy and initiative”) tend to consider more characteristics relevant to identifying communities and groups at risk, compared to those with indirect approaches (“added protection and safeguards” and “guarantee of rights”), although there are some notable exceptions (e.g., Costa Rica, England (the United Kingdom) and Switzerland). The difference between countries that deploy the two types of indirect approaches is also observed, with countries using added protection and safeguards taking more characteristics into account than countries which guarantee of rights. This may reflect more dedicated resources made available to conduct in-depth assessments, data availability, and the existence of established bodies of anti-discrimination law.

However, a larger number of factors considered in countries with direct approaches to environmental justice may reflect the presence of salient, pre-existing environmental justice concerns. Furthermore, while consideration of vulnerabilities is critical, the breadth in characteristics considered may not necessarily translate into a more comprehensive approach to environmental justice. For instance, attempting to consider too many characteristics might spread the efforts too thin and hinder targeted measures if adequate resources are not made available.

4.1.2. Consideration of specific regions at a greater risk of environmental injustice

Copy link to 4.1.2. Consideration of specific regions at a greater risk of environmental injusticeHistorically, research has investigated environmental justice concerns from a spatial perspective (Walker, 2012[9]), reflecting (i) over or disproportionate representation of certain groups or communities in neighbourhoods that are underserved or overburdened with pollution and (ii) concentration of polluting industries and facilities. Often, it is a combination of these factors that puts a region at a greater risk of environmental injustice. About half of countries identify regions in which communities or groups may be particularly exposed. In the majority of the countries that identify specific regions in this context, they mirror the regions’ reliance on pollution-intensive industries resulting in economic dependence as well as poor air quality. Examples include “Cancer Alley” in Louisiana, US, in which a high concentration of petrochemical companies and their toxic waste was associated with higher cancer risks for communities in primarily African American neighbourhoods (OHCHR, 2021[10]).

The regional variability of risks and its link with the sectoral composition also illustrate that the transition towards more environmentally sustainable economies may have disproportionate impacts across places, as helpfully highlighted by the concept of just transition. Specific regions in this context are identified in terms of efforts to reduce reliance on fossil fuels and carbon-intensive industries (European Commission), and the resultant transitional impact such as the closure of coal (Poland) and nuclear power plants (Spain).

In the response to the Survey, countries highlight specific regions’ geographical characteristics as a relevant factor for inequitable exposure to environmental harms for various reasons. Some countries, including Scotland, consider mountainous or hilly regions and islands in relation to remoteness. Such consideration may relate to limited access to key public services, a risk factor often identified across countries. Other countries such as France, Croatia and the United States consider rural areas to be at a greater risk, for instance, due to the exposure to pollution from pesticides in agricultural land. Meanwhile, some countries consider the differential risks of regions in relation to the communities and group that reside within them. The United States and Mexico highlighted the regions inhabited by Indigenous populations, while South Africa and the Slovak Republic respectively consider urban areas with high concentration of poor and predominantly Black population3 and settlements of marginalised Roma communities.4

4.2. Assessing environmental justice concerns

Copy link to 4.2. Assessing environmental justice concernsThis section scans country approaches to assessing environmental justice concerns, building on the following set of questions:

Whether countries have specific tools (e.g. interactive maps) that allow decision-makers to combine data and information on environmental, social and economic variables;

Whether countries use qualitative data and methods in their assessments of the risk or exposure to environmental hazards.

4.2.1. Methods and tools to assess environmental justice concerns

Copy link to 4.2.1. Methods and tools to assess environmental justice concernsResearch in environmental justice has deployed a number of methodologies and tools, including various geographic information systems, composite indicators and screening tools to understand the spatial patterns of environmental burdens and benefits. Around half of countries have dedicated tools for assessing environmental justice concerns, such as interactive maps that allow users to combine environmental, social and economic data,5 and an additional four countries have tools that are under development.6 There is notable variation among countries deploying direct and indirect approaches to environmental justice, with the overwhelming majority of countries with direct approaches having or being in the process of developing such tools.7 This might be explained by the fact that the concept is relatively more established in countries with a more direct approach, which may have afforded them more buy-in and resources to develop dedicated tools.

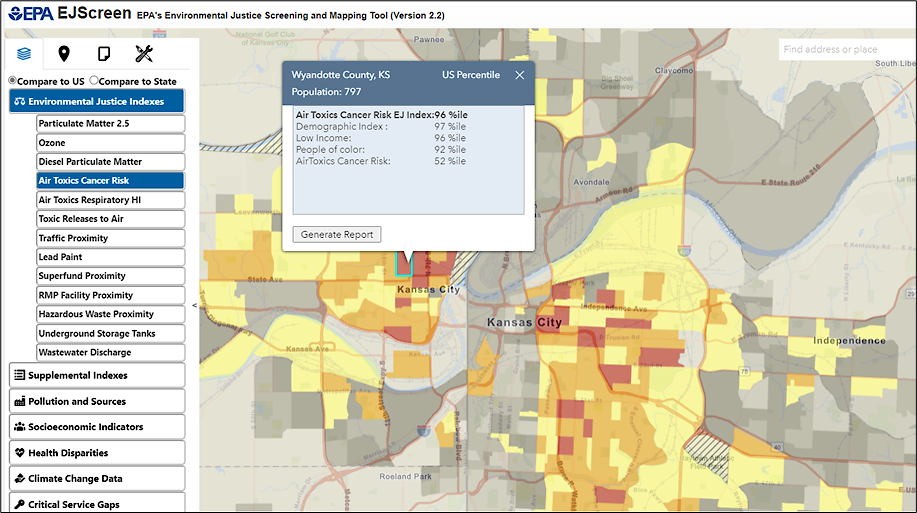

However, these tools tend to vary in their level of specificity for assessing environmental justice concerns. For instance, countries such as France, Canada, and Mexico have more generic data hubs and interactive maps with a range of indicators. Meanwhile, some countries have devised more dedicated assessment tools. Emerging examples suggest that it is the combination and layering of environmental, demographic and socio-economic data that deliver valuable insights. For instance, the Scottish Government has developed the “Flood Disadvantage” dataset comprising 34 vulnerability indicators, overlaying various personal, environmental (e.g. availability of green space) and social factors (e.g. income, home ownership) to map and identify communities that might be disadvantaged in terms of flood resilience and response (The Scottish Government, 2015[11]) (Box 4.2). While the Scottish Government’s tool focusses on vulnerability to an environmental hazard, similar tools can also be used to examine access to environmental benefits. For instance, Natural England8 has developed the “Green Infrastructure Map” which maps data on access to green and blue space,9 onto socio-economic indicators (Natural England, 2021[12]).

Box 4.2. Mapping Flood Disadvantage in Scotland (United Kingdom)

Copy link to Box 4.2. Mapping Flood Disadvantage in Scotland (United Kingdom)The map of Flood Disadvantage published by the Scottish Government allows for identification of communities that may be exposed to greater risks of flood due to their combined social vulnerability and geographical location. Social vulnerability is assessed based on 14 personal, environmental and social factors corresponding to three dimensions of vulnerability: sensitivity, enhanced exposure and adaptive capacity (ability to prepare, respond and recover). Combining these data, the map indicates the degree of flood disadvantage for a given area, as shown in the below figure.

Figure 4.2. Example view of the map of Flood Disadvantage

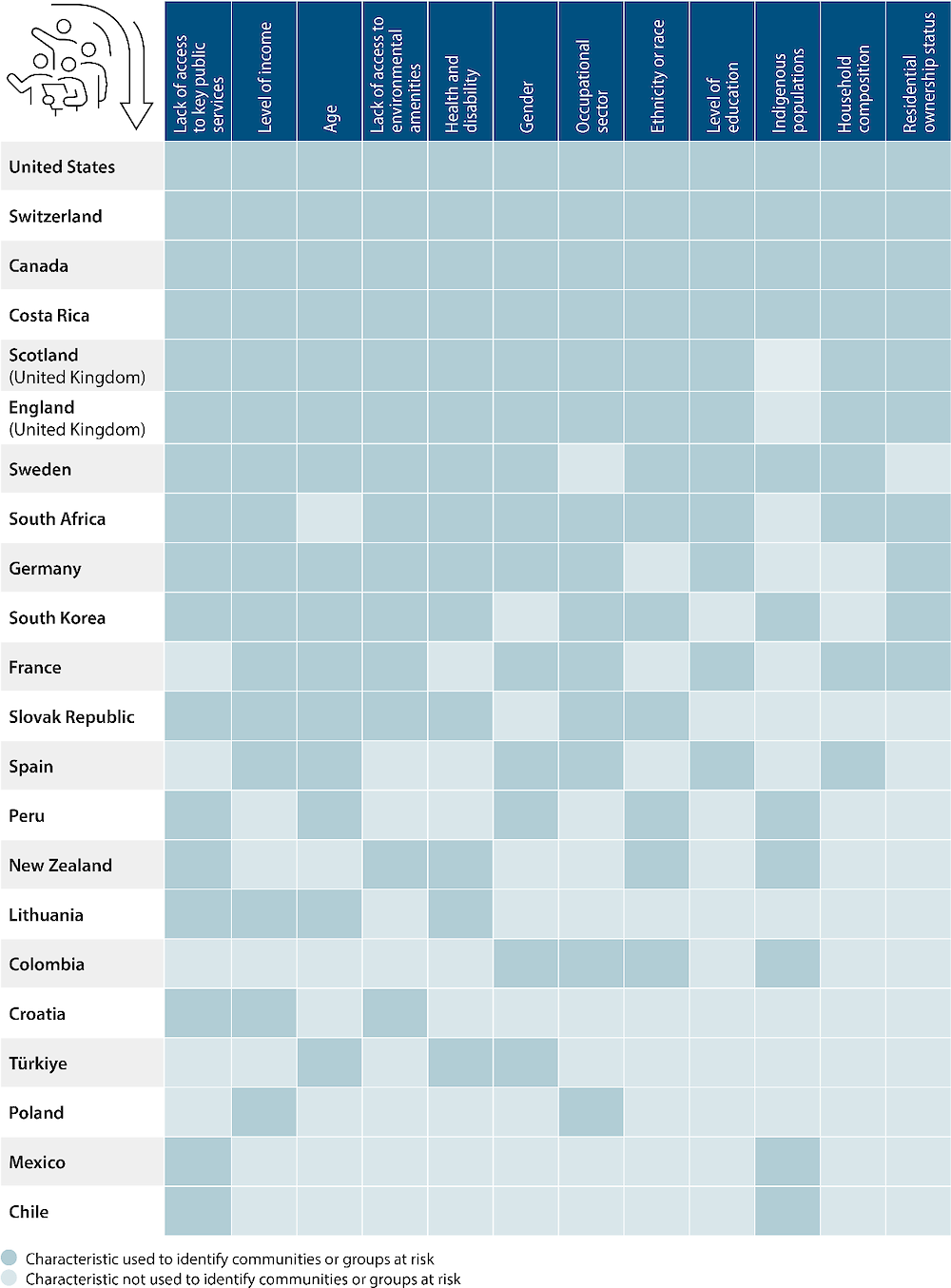

Copy link to Figure 4.2. Example view of the map of Flood DisadvantageThe Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool (EJScreen) developed by the US EPA, is among the most detailed tools available to identify areas of potential environmental justice concern (Box 4.3). While other tools typically focus on a single issue, the EJScreen allows for the consideration of a wider range of risks, including proximity to hazardous waste and wildfire. The tool is also built with user friendliness in mind, allowing users to generate reports and compare a set of indicators at different levels of aggregation (United States Environmental Protection Agency, n.d.[15]). Moreover, the tool allows for performing proximity analyses by inputting locations of interest and the buffer distance, providing users with spatial insights.

Box 4.3. US EPA’s Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool (EJScreen)

Copy link to Box 4.3. US EPA’s Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool (EJScreen)EJScreen provides data on 13 environmental indicators (e.g. air toxics cancer risk, hazardous waste proximity) as well as seven socioeconomic ones (e.g. unemployment rate, limited English speaking) across the United States. For each of the 13 environmental indicators, an EJ index is constructed, based on the environmental indicator percentile for a given area multiplied by its demographic index. The demographic index averages the share of people of colour and low-income populations in a given area.

The supplemental index offers insight into additional dimensions of vulnerability. The Supplemental Indexes use the same methodology as the EJ Indexes, but incorporate a five-factor supplemental demographic index, as opposed to the two-factor demographic index discussed above. The supplemental demographic index averages the percent low income, percent unemployed, percent with limited English proficiency, percent with less than a high school education, and low life expectancy. Although there are certain limitations, such as availability of nationally consistent data across various environmental justice issues, it serves as a powerful means to identify priorities for further action (OECD, 2023[16]). Based on the chosen indicators, EJScreen colour-codes the selected area to visualise the degree of environmental justice concern, with the darker shades signifying greater potential environmental justice concerns (Figure 4.3).

Figure 4.3. Example view of the EJScreen

Copy link to Figure 4.3. Example view of the EJScreenThere are also efforts made at the sub-national level in some countries, reflecting the localised nature of environmental justice concerns. For instance, Berlin (Germany) and the City of Westminster (England, United Kingdom) have developed locally tailored tools to inform policy action.10 Compared to tools with a national scope, they have advantages in data consistency and ability to incorporate local environmental challenges, such as noise pollution and heat islands. A comparison of the two sub-national tools also illustrates different sub-national approaches to environmental justice: the development of explicit environmental justice frameworks (Berlin) and the integration of the concept into existing strategies and solutions (The City of Westminster) (Box 4.4).

Box 4.4. City Level Assessments: Comparison of the Berlin Environmental Justice Atlas and the Westminster Environmental Justice Measure

Copy link to Box 4.4. City Level Assessments: Comparison of the Berlin Environmental Justice Atlas and the Westminster Environmental Justice MeasureBerlin Environmental Justice (EJ) Atlas (Berlin, Germany)

Copy link to Berlin Environmental Justice (EJ) Atlas (Berlin, Germany)The EJ Atlas was created through an inter-departmental initiative led by the State of Berlin against the backdrop of the adoption of a comprehensive environmental justice approach in the municipal environmental and health policy in Berlin. The Atlas consists of detailed maps of the city that identify the neighbourhoods that are disproportionately exposed to health-related environmental burdens. Five core environmental and social indicators are analysed: noise pollution, air pollution, bioclimatic burden, green and open spaces and social deprivation. Population density as well as quality of residential area are also available to enable additional vulnerability analysis.

Environmental Justice Measure (The City of Westminster, England, United Kingdom)

Copy link to Environmental Justice Measure (The City of Westminster, England, United Kingdom)The City of Westminster is another local authority that has created its own environmental justice assessment tool, where the concept of environmental justice was integrated into their strategy aimed at enhancing fairness and sustainability. The Environmental Justice Measure consists of ten environmental metrics (e.g. air quality, flood risk, energy efficiency of buildings) and the existing datasets developed at a national level (socio-economic Index of Multiple Deprivation1).

Similarities in approaches

Copy link to Similarities in approachesIn contrast to the US EPA’s EJScreen which provides multiple independent socioeconomic indicators, the tools developed by Berlin and Westminster use composite indicators of social deprivation; the Status Index in Berlin (based on unemployment, receipt of transfer payments and child poverty) and the Index of Multiple Deprivation in Westminster (based on, among others, income, employment, education as well as health and disability). The composite indicators may have an advantage of capturing the multi-dimensional character of environmental justice, as well as the ease of interpretation.

Differences reflecting specific local concerns

Copy link to Differences reflecting specific local concernsAlthough both tools consider air quality, heat risk and access to green and open space, some of the issues studied vary, reflecting specific local concerns and policy priorities. Unlike the EJ Atlas, the Environmental Justice Measure features an additional focus on sustainable transportation (% of people commuting by bike or walking, proximity to cycling facilities) and energy efficiency of buildings. By incorporating these elements, the tool also captures communities’ ability to reduce negative environmental impacts and mitigate risks stemming from their local environment.

1. For an overview of a different local environmental justice measure, based on the UK Index of Multiple Deprivation, see Birmingham Environmental Justice Map (Naturally Birmingham, n.d.[18]).

While these tools can be leveraged by policymakers to identify areas of greater vulnerability or by the public to gain insights into environmental quality in their neighbourhood, similar tools are also used to better inform businesses about the potential environmental impacts of their projects. The Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Screening Tool developed by the South African Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment enables applicants for environmental authorisation to assess environmental sensitivity of a proposed development site (Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment, n.d.[23]). Depending on the location of a proposed site and the type of project (e.g. rails, pipelines, energy production, waste management facilities), the application identifies relevant EIA requirements and generates reports on the environmental sensitivity of a project. The tool uses more than 130 layers of spatial environmental sensitivity data, concerning biodiversity, agriculture, air quality priority areas or cultural heritage. Additional layers of climate change risk data, intended to provide insights into environmental justice concerns are currently under development.

Relatedly, some countries commission tailored epidemiological studies to understand the linkages between environmental quality and health outcomes for vulnerable segments of the population. For instance, Japan Environment and Children’s Study, conducts a longitudinal birth cohort analysis using regularly collected biological samples and survey with an unprecedentedly large sample of 100,000 children, allowing for the identification of environmental factors affecting children’s health to inform the subsequent development of appropriate risk management measures (Ministry of the Environment, Government of Japan, n.d.[24]). A similar initiative, although aimed at all age groups, is being undertaken in South Korea. Mandated by the Environmental Health Act, the National Environmental Health Survey has been conducted periodically since 2009, allowing for monitoring and measurement over time (Environmental Health Information System, n.d.[25]).

Furthermore, an analysis of the Survey revealed that over three quarters of countries employ qualitative methods in addition to quantitative ones to assess environmental justice concerns. Although the use of quantitative data and methodologies appear to be generally preferred for screening and assessing environmental justice concerns, they face important limitations due to the availability of granular data. Certain environmental justice concerns and unique lived experiences of communities may not easily lend themselves to quantification.

Importantly, engaging with the affected communities directly may also offer ways to better integrate community perspectives, culture and types of knowledge. For instance, integrating Indigenous traditional knowledge11 can also ensure their concerns are identified and adequately assessed, mitigating the risk of climate action causing further harm to the communities (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2023[26]). The use of qualitative methods can therefore complement quantitative data and yield additional insights. There are illustrative cases of targeted efforts to engage with the affected communities, including institutionalised mechanisms for consultations with Indigenous communities in Costa Rica (see Box 4.5), Chile, Colombia, Peru and Mexico developed in line with the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention which establishes the duty of government for consulting the communities likely to be affected by legislative and administrative measures (International Labour Organization, 1989[27]).

Box 4.5. Consultations with Indigenous communities in Costa Rica

Copy link to Box 4.5. Consultations with Indigenous communities in Costa RicaCosta Rica deploys a multitude of participatory and consultative mechanisms to engage with Indigenous communities

Copy link to Costa Rica deploys a multitude of participatory and consultative mechanisms to engage with Indigenous communitiesSpread over 24 territories, Indigenous Peoples make up 2.4% of the population in Costa Rica. In 2018, the General Mechanism for Consultation with Indigenous Peoples was developed together with the engagement of Indigenous communities with a purpose to represent a diverse set of cultural and spiritual worldviews (Ministry of Justice and Peace, 2018[28]). Introducing key principles and eight foundational steps, the Mechanism has been deployed to better understand the concerns of Indigenous Peoples and inform subsequent policy development for biodiversity conservation and reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD+).

Biodiversity

Copy link to BiodiversityHome to almost 6% of known species, Costa Rica’s rich biodiversity provides a source for its key economic sectors including nature-based tourism and agriculture, making biodiversity conservation a policy imperative (OECD, 2023[29]). However, the introduction of protected wilderness areas (some of which overlaps with territories managed by Indigenous Peoples) have previously caused tension (ibid).

The National Biodiversity Management Commission (CONAGEBIO), responsible for overseeing the implementation and monitoring of the National Biodiversity Strategy 2016-2025 and Action Plan (ENB2), consists not only of civil servants, but also Indigenous Peoples, businesses and farmers. ENB2, a result-driven strategy based on over 100 targets, is an outcome of participatory processes, including Indigenous Peoples (OECD, 2023[29]). The public engagement was ensured from the very beginning of the strategy development, commencing with identification of key issues to address and sharing past experiences. One of the key achievements of the processes is a biodiversity map on ecosystem services, as well as current and future threats to them, that integrate the knowledge and values of the public. The CONAGEBIO is currently working on the application of the Indigenous consultation mechanism for two executive decrees on access to genetic and biochemical resources of biodiversity and community intellectual rights of Indigenous Peoples (CONAGEBIO, n.d.[30]).

Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+)

Copy link to Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+)The National Strategy REDD+ is foundational to Costa Rica’s strategy for sustainably managing its rich forestry and contribute to increased carbon sink capacity (OECD, 2023[29]). Indigenous Peoples took an active part in its development through the National Plan for Indigenous Consultation in the Development of National REDD+ Strategy. The processes undertaken contain several novel approaches to engage meaningfully with the communities. For instance, reflecting due consideration to the unique characteristics of each Indigenous territory, the consultations were conducted at various levels of governance, with representatives from all 24 territories. Moreover, over 150 Cultural Mediators (Mediadores Culturales) from Indigenous communities were engaged with the authorities to exchange knowledge and disseminate information to their communities in their own language.

There remain important challenges for promoting meaningful engagement

Copy link to There remain important challenges for promoting meaningful engagementDespite these mechanisms and guidance on the processes, inclusive participation of the affected communities can be hindered by limited allocation of administrative and financial capacity to engage with Indigenous communities. Without adequate funding that consider these costs, it can be challenging to ensure their meaningful engagement. More targeted allocation of human and financial resources for these consultations can further foster active participation and help scale the successful examples.

4.3. Addressing environmental justice concerns

Copy link to 4.3. Addressing environmental justice concernsThis section aims to identify the ways in which countries address environmental justice concerns. The findings are based on the following set of questions:

What measures countries have implemented specifically to address environmental justice;

How participation and engagement in environmental policies informed any subsequent measures.

4.3.1. Measures to address environmental justice concerns

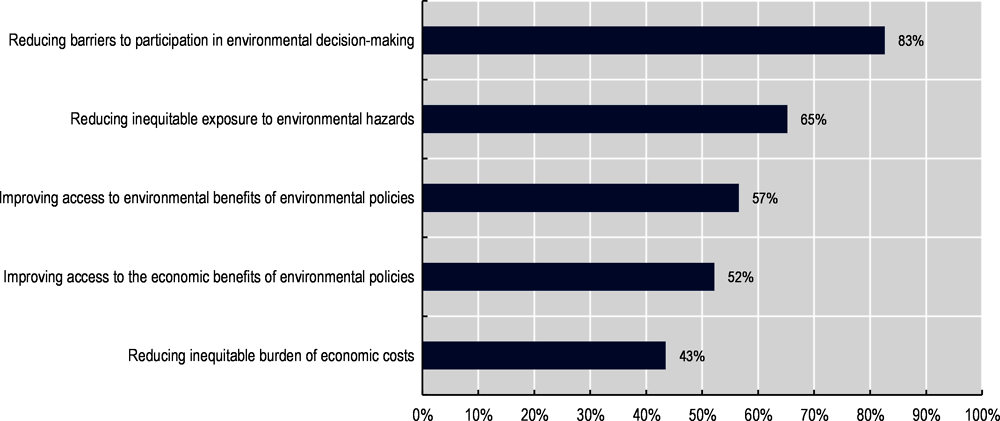

Copy link to 4.3.1. Measures to address environmental justice concernsMost countries address environmental justice concerns through reducing barriers to participation in environmental decision-making (Figure 4.4). The prevalence of such measures may reflect the potential impact international instruments may have on the procedural aspect of environmental justice in national administrations. However, a cautious interpretation is required due to the sample of this survey, which includes 13 parties to the Aarhus Convention in Europe and five Latin American countries who have signed or ratified the Escazú Agreement (Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Mexico and Peru). Countries that are party to neither of these international conventions, such as Japan, Türkiye and the United States also implement measures to reduce barriers to participation, highlighting the broad emphasis on the procedural aspect across countries.

Reducing inequitable exposure to environmental hazards is also an important consideration across countries, with around two thirds of countries indicating they have mitigation measures in place. Meanwhile, improving access to environmental as well as economic benefits of environmental policies seem to be given less attention, with around half of countries implementing dedicated measures. Notably, the survey responses reveal that less than half of the countries address environmental justice concerns through reducing the economic costs of environmental policy.

Figure 4.4. The use of policies to address environmental justice concerns

Copy link to Figure 4.4. The use of policies to address environmental justice concerns

Note: Based on 23 responses. Respondents were asked to select all that apply. The European Commission, Slovak Republic and Spain did not provide a response to this question.

Source: The OECD Environmental Justice Survey.

Reducing barriers to participation in environmental decision-making

Copy link to Reducing barriers to participation in environmental decision-makingExploring the various ways through which countries encourage participation, most countries focus primarily on facilitating public participation in environmental policy processes. Consultations are widespread, with many countries mandating and establishing dedicated mechanisms and tools to engage the public. Examples include dedicated websites (England and Scotland (United Kingdom)), implementation of public comments (Japan) and mandatory consultations when applying for environmental permits (Sweden). Consultations can also assume different forms depending on the context, needs and resources, as Chile’s experience with implementing various participatory activities demonstrates (Box 4.6).

Box 4.6. Varying modalities of participation in Chile

Copy link to Box 4.6. Varying modalities of participation in ChileParticipatory implementation of the Escazú Agreement

Copy link to Participatory implementation of the Escazú AgreementFollowing the Early Participation Process, Chile has begun to develop the National Participatory Implementation Plan of Escazú 2024-2030 (PIPE). The Plan addresses five pillars through 56 general actions with a commitment to implementation between 2024 and 2030. Amongst other things, the Plan seeks to address the need to:

Inform citizens more comprehensively

Consider children and adolescents in decision-making

Review the rules for citizen participation in public services

Participate earlier in the elaboration of public policies

Train civil servants and citizens on access rights and environmental protection

Have mechanisms for the exchange of experiences on access right

Create and update existing information platforms.

Move towards the protection of personal data.

Reorganise the work of human rights defenders on environmental issue.

Promote legal reform to reduce asymmetries in access to justice, including by considering the dynamic burden of proof in procedures for liability for environmental damages.

These actions are reflected in 236 measures from public institutions incorporated into the plan (Table 4.1).

Table 4.1. Example measures relating to the National Participatory Plan of Escazú 2024-2030 (PIPE)

Copy link to Table 4.1. Example measures relating to the National Participatory Plan of Escazú 2024-2030 (PIPE)|

Pillar |

Examples of relevant measures by Chilean Ministries and other public institutions |

|---|---|

|

Access to public environmental information |

Creation of new participatory modalities for Indigenous Consultations such as meetings between Indigenous Human Groups and the environment assessment service (measure 162) |

|

Creation of a Science and Technology Information System on Climate Change to make data and scientific knowledge available to the public (measure 16) |

|

|

Development of internal data protection protocol to help anonymise environmental complaints (measure 205) |

|

|

Access to public participation in environmental decision-making |

Update the General Standard of Citizen Participation within the framework law 20,500 (measure 18) |

|

Access to justice in environmental matters |

Disseminate details on both state and non-state access to justice tools as well as extrajudicial legal proceedings (measure 56) |

|

Human rights defenders in environmental matters |

Creation of plan to enhance competency of healthcare providers and address access to healthcare for environmental defenders who suffered attacks, intimidation, or threats (measure 82) |

|

Creation of Chilean Protocol on Human Rights Defenders which enables inter-institutional coordination for the protection of human rights defenders (measure 58) |

|

|

Strengthening capacities and cooperation |

Train officials on transparency, access rights to information, and accountability in environmental matters (measure 2) |

Consultation of the amendment of Law 19.300

Copy link to Consultation of the amendment of Law 19.300Citizen consultation is also key in the ongoing process of amending the Law 19.300 on the General Bases of the Environment (1994), which establishes the framework for environmental protection and instruments including Environmental Impact Assessment, in light of new environmental challenges. To ensure meaningful citizen participation, a series of in-person Participatory Dialogues was held across all 16 regions of Chile. The Dialogues, open to all, aimed at engaging as many participants as possible and consisted of two parts: 1) presentation of the proposed amendments to the law; and 2) participatory workshops to gather citizens’ opinions. Complementing in-person meetings, an online mailbox was made available. Outcomes of each Dialogue were subsequently published on the Ministry website and presented in a webinar.

Variety of modalities available can help ensure meaningful participation

Copy link to Variety of modalities available can help ensure meaningful participationIn Chile, a diverse array of citizen participation methods is employed. This is especially important as traditional consultations alone may not reflect the breadth of views in the society due to the presence of selection bias (see Section 2.4.3 in Chapter 2). A variety of methods can help ensure the diversity of perspectives. Modalities such as self-convened town halls can be particularly beneficial in remote areas where the presence of government officials is limited. Similarly, due to potential barriers to participation faced by vulnerable groups such as youth or Indigenous Peoples, devising activities that target them specifically can increase the visibility of their views.

Furthermore, some countries engage with the public in the development of major environmental and climate plans and strategies through deliberative processes. Lithuania noted its National Energy and Climate Plan for 2021-2030, developed in close consultations with local and regional stakeholders, associations, and the general public through a series of events and a dedicated online consultation platform.12 Similarly, in Germany, the Climate Adaptation Dialogue was held in 2023, with online participation (with a dedicated platform for youth aged between 14 and 25) and regional events with samples of randomly chosen participants, to develop the German Strategy for Adaptation to Climate Change under the nationwide climate adaptation law (Federal Ministry for Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety, 2023[37]).

Identifying key stakeholders in a strategic, rather than necessarily complete, manner can complement participatory mechanisms to enable the most affected to ensure their views are represented in decision-making processes. In this context, some countries adopt more targeted approaches to engage with specific segments of the population. For instance, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Mexico, New Zealand and Peru highlighted they deploy specific mechanisms for consulting Indigenous Peoples, recognising the unique role of Indigenous Peoples in caring for the environment and the historical legacy of discrimination.

In addition, over half of countries have measures to improve access to information. Many countries have measures in place to ensure transparency and make information available upon request. For instance, Sweden makes applications for permits for activities with the risk of environmental hazards, together with their environmental impact statements, available to the public by default. Scotland ensures access to requested information in the 2004 Environmental Information Regulations (Public Health Scotland, 2023[38]).

Maps and data portals that are used for assessing environmental concerns (see Section 4.2.1) can also serve as a valuable tool for informing the public. For instance, New Zealand’s Ministry of Health provides funding for “Environmental Health Intelligence New Zealand”, which not only provides data dashboard and information on environmental hazards but also profiles of vulnerable population groups and their regional variabilities, as well as dedicated statistics on Māori environmental health (Environmental Health Intelligence New Zealand, n.d.[39]). Similarly, the Korean Environmental Health Comprehensive Information System provides information on environmental hazards across neighbourhoods, made accessible with the use of icons and images and a range of educational materials (Ministry of Environment, n.d.[40]).

Meanwhile, some of the initiatives focus on actively delivering environmental information to the public. Poland developed the “Air quality in Poland” mobile application which provides air quality information, forecasts, warnings, and maps. Polish citizens can also receive SMS warnings when an alarming level of PM10 is observed. A similar solution is deployed in South Africa, where the South African Air Quality Information System (SAAQIS) is available both online and through a mobile application. The example of South Africa highlights the importance of tailoring tools to the local context; less than one third of citizens have access to computers and mobile phones are important devices for informing citizens about the environmental risks.13 South Africa also notes that lack of public awareness of environmental challenges constitutes an important barrier to information. Reflecting the role of mainstream media such as television as the key source of information for citizens, South Africa is also exploring a pilot in collaboration with popular television shows, integrating environmental information in the scripts to raise public awareness.

While approaches to removing barriers to information vary from making information available to actively delivering information, these initiatives rarely have a targeted focus for vulnerable communities. The US EPA’s Office of Environmental Justice and External Civil Rights’ monthly online engagement calls are among a few examples of policy measures directly targeting procedural environmental justice that seeks to inform the vulnerable communities about ongoing policy initiatives (Box 4.7).

Box 4.7. National Environmental Justice Community Engagement Calls

Copy link to Box 4.7. National Environmental Justice Community Engagement CallsMonthly National Environmental Justice Community Engagement Calls are held by the US EPA’s Office of Environmental Justice and External Civil Rights to meaningfully engage, and better inform the public about the Office’s work on environmental justice. Through this form of direct dialogue, the public can provide feedback on the agency’s activities as well as participate in “Questions and Answers” sessions and receive information regarding, for example, grant applications or the agency’s upcoming programmes. Examples of topics discussed during the calls are:

An Overview of new Presidential Executive Orders and Memoranda (2021) related to Environmental Justice

EJ Programme Updates, including NEJAC, EJScreen, Collaboration with States and Tribes

EJScreen 2.0: What’s New in EPA’s Environmental Justice Screening Tool

Its online format can facilitate public engagement, allowing the participation regardless of the place of residence. As the number of participants during a webinar is limited, recordings of all sessions are provided on the EPA’s website. Moreover, transcripts of some sessions are published both in English and Spanish, thus enabling access to information for persons with hearing impairment and those with limited English proficiency.

Meanwhile, only about one third of countries have policy measures to facilitate access of potentially interested persons to administrative and judicial procedures in environmental matters. New Zealand facilitates not-for-profit organisations’ access to public interest litigations in environmental matters through financial assistance provided through a dedicated Environmental Legal Assistance Fund (Ministry for the Environment, 2024[42]). Others indirectly enable access to justice by strengthening enforcement and compliance with environmental legislation by increasing the capacity and knowledge of government officials in environmental law and administrative enforcement. In South Africa, the Environmental Management Inspectorate (EMI) was established to improve monitoring and enforcement in the various segments of the legislations including pollution and coastal management (Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment, n.d.[43]). The Inspectorate is composed of the “Green Scorpions” – local, provincial, and national government officials – who undergo a mandatory training course, including in environmental law.

Although the survey responses generally did not refer to environmental courts and tribunals (ECTs), desk research reveals that about half of countries have established such institutions.14 Relatedly, several countries also improve access to justice by clustering relevant administrative tribunals, such as urban planning and environment, to streamline the process (OECD and Open Society Foundations, 2016[44]). Contrary to traditional courts which may lack specialised knowledge on environmental matters, ECTs can be staffed with judges who are well-versed in environmental science, increasing their capacity to provide effective access to environmental justice (Robinson, 2012[45]). Moreover, their jurisdictional authority and dedicated resources can enable development of influential jurisprudence (UNEP, 2022[46]). ECTs also often provide legal and technical aid to claimants and have more relaxed procedural requirements and streamlined procedures, thus facilitating effective access to justice (UNEP, 2019[47]).

Reducing inequitable exposure to environmental hazards

Copy link to Reducing inequitable exposure to environmental hazardsAlthough many countries (65%) have policy measures in place to reduce inequitable exposure to environmental hazards, the majority of the measures cited are targeted at overall improvement of environmental quality. These include amendments to waste management laws (Mexico), environmental assessments (Portugal, South Korea) and permitting for new industrial facilities and landfills (England, Scotland (United Kingdom)). Some countries also highlighted policy mechanisms that advance procedural dimension of environmental justice by strengthening the legal basis for recourse (Scotland, United Kingdom) and improving effective access to remediation for environmental pollution (Japan, South Korea).

Fewer countries have more targeted measures for alleviating the environmental burden for specific groups or regions, although it is important to note that the implementation of targeted measures might reflect historical and pre-existing concerns over inequitable exposures that are more salient. Examples include the US Justice40 Initiative which aims to direct at least 40% of the benefits of certain federal programs (e.g. related to investments in clean energy, remediation and reduction of legacy pollution) to communities burdened by underinvestment and pollution (White House, n.d.[48]). Similarly, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law requires that 49% of the funds to improve drinking water infrastructure be directed at disadvantaged communities (White House, 2021[49]). Another notable example of environmental justice concerns leading to policy action to address unequal distribution of environmental hazards is the case of “Sacrifice Zones” in Chile (Box 4.8).

Box 4.8. Addressing environmental injustice in “Sacrifice Zones”, Chile

Copy link to Box 4.8. Addressing environmental injustice in “Sacrifice Zones”, ChileThe term “sacrifice zones” has been used to describe areas where communities live near pollution-intensive industries and suffer the consequences of the various pollutants they generate. The term describes: “a situation of evident environmental injustice, in that the benefits generated by [industry] are diffusely distributed throughout society as a whole, while the environmental costs are borne by people in situations of social and economic vulnerability.” (Instituto Nacional de Derechos Humanos, 2011[50]). With focus both on managing the transition of industries and disaggregated impact on communities’, Chile’s approach also highlights the cross-over between just transition policies and environmental justice.

The finding that 40 children became unwell because of exposure to high levels of arsenic in the air surrounding their school which was positioned next to a large copper refinery raised visibility of the issue of sacrifice zones in Chile. This, and other similar events, gave rise to greater recognition of the intersectionality of environmental rights with various issues – such as health, work, housing, or education – and catalysed a movement which led to Chile’s “Environment and Social Recovery Plans” (ESRPs).

In the ESRPs for Huasco, Quintero-Puchuncaví, and Coronel, various ways of addressing sacrifice zones are currently implemented. The Chilean administration categorises these solutions under the headings of air, water, sea, soil, landscape and biodiversity, society, health, and infrastructure. The table below (Table 4.2) provides some examples of these solutions taken from the ESRPs noted by Chile in their response to the survey (Ministerio del Medio Ambiente, Gobierno de Chile, n.d.[51]).

Table 4.2. Examples of policies in the Chilean Environmental and Social Recovery Plans (ESPRs)

Copy link to Table 4.2. Examples of policies in the Chilean Environmental and Social Recovery Plans (ESPRs)|

Environmental and Social Recovery Plan |

|

|---|---|

|

Air quality |

Update air quality standards (e.g. for sulphur dioxide) |

|

Establish monitoring station to improve the air quality |

|

|

Develop training programme on air quality and emissions aimed at relevant actors |

|

|

Create publicly accessible web platform providing access to data from monitoring stations |

|

|

Other Health |

Implement programme for surveillance of people's health |

|

Develop closure plan to reclaim landfill space |

|

|

Develop composting programme to reduce organic waste |

|

|

Improve waste management of micro, small and medium sized enterprises |

|

|

Social |

Develop conservation plans for areas not yet affected by human activity |

|

Develop projects that generate quality public spaces |

|

|

Clean up waste from industrial park and establish areas for forestation with native species |

|

|

Regulate entry of new companies which produce dangerous pollutants |

While the ESRPs and the broader framework of the Just Socio-Ecological Transition adopted by Chile in recent years provide a solid institutional foundation, challenges remain for their implementation. Improving data collection with the use of screening and mapping tools could facilitate the identification of relevant communities, overburdened by pollution and the design of well-targeted policies. Furthermore, in view of the coal phase-out and carbon tax and their impacts on employment and low-income households, the Just Socio-Ecological Transition is predicated on more comprehensive social assistance programmes (OECD, 2024[52]).

1. In addition, as pointed out in the report of the UN Special Rapporteur on human rights and the environment, important differences exist with regard to the capacity to adapt to the creation of ”sacrifice zones” – while for wealthier residents it may be easier to relocate to an area with better environmental quality, low-income residents may lack alternatives and are thus unavoidably compelled to endure the negative health impacts (Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, 2023[53]).

Improving access to environmental benefits of environmental policies

Copy link to Improving access to environmental benefits of environmental policiesOver half of the countries (57%) implement measures aimed at improving access to the environmental benefits of environmental policies. In Sweden, access to environmental benefits is mandated by the Planning and Building Act, which states that “planning, with regard to natural and cultural values, environmental and climate aspects, as well as inter-municipal and regional conditions, must promote, among other things, a socially good living environment that is accessible and useful for all social groups”. Across many countries, there is an emphasis on enhancing access to environmental amenities in urban areas. For instance, the German Federal Ministry for the Environment provides support to local authorities to implement a wide-ranging programme to improve quality and access to green and recreational space under its “Urban Nature Master Plan”. Similarly, “Environmental Improvement Plan 2023” uses the fund dedicated to addressing regional inequalities in England15 to create and refurbish green spaces in deprived urban neighbourhoods (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, 2023[54]). Other examples of policy measures that enhance access to environmental benefits focus on protection of biodiversity (Costa Rica) as well as nature conservation and wildlife rehabilitation projects (Portugal).

Improving access to economic benefits of environmental policies

Copy link to Improving access to economic benefits of environmental policiesJust over half of countries (52%) have policy measures to improve access to economic benefits of environmental policies. Most measures countries use entail tailoring the design of broader policies that support modernisation and weatherisation of buildings and sustainable transport and mobility. For example, support provided for improving energy efficiency under the Polish “Clean Air Programme” is determined by income thresholds, prioritising less affluent households. Similarly, France has adopted income-based subsidy schemes for facilitating take-up of green technologies and investments in energy efficiency.

A more direct approach to improve access to economic benefits of environmental policy is taken in Costa Rica through its use of payment for ecosystem services programme, in operation since 1997. This programme pays landowners, including Indigenous communities who steward their territories for sustainable management of forests on their lands, contributing to increasing the forest cover and providing sources of employment and income.

Reducing inequitable burden of economic costs of environmental policies

Copy link to Reducing inequitable burden of economic costs of environmental policiesNotably, less than half (43%) of countries address the inequitable burden of economic costs of environmental policies, despite the distributive consequences of environmental policy through their impact on income and prices (Vona, 2021[55]). This may reflect the challenges in identifying and considering the implications of environmental policies at the granularity required to inform the policy design to mitigate distributive consequences.

Eight countries included the mention of the concept of just transition which is closely linked to the issue of distribution of economic costs and benefits of environmental policy. For example, the Scottish Government cites their policy document “Just Transition: A Fairer Greener Scotland” which details the need to ensure the costs of the transition to a more environmentally sustainable economy do not overburden those least able to pay. Likewise, the European Commission highlights Just Transition Mechanism under the European Green Deal (Box 4.9). Relatedly, the European Commission has established the Social Climate Fund, explicitly apportioning part of the revenues from carbon pricing towards mitigating distributional impact of environmental policy for the most adversely affected in light of the extension of the emissions trading system (ETS) to transport and building sectors. The funds can be directed towards households facing energy or transport poverty, through support for investments in energy efficiency, renovation of buildings and zero- and low-emission mobility (European Commission, n.d.[56]). These policies may help alleviate the transitional impact, but applying environmental justice lens can complement them by identifying overlooked vulnerabilities and ensure they do not compound the distributive consequences of increasingly stringent environmental policy.

Box 4.9. Addressing uneven distribution of costs and benefits of environmental policy through just transition strategies – the case of the European Union

Copy link to Box 4.9. Addressing uneven distribution of costs and benefits of environmental policy through just transition strategies – the case of the European UnionAiming at addressing uneven social and economic impacts of environmental policy across sectors and communities, just transition have been placed high on policy agendas in recent years. The European Commission’s response provides an illustration of how this concept is applied in practice. The Commission’s flagship European Green Deal is explicit in its aim to ensure the transition will “leave no one or no region behind”.

To this end, Just Transition Mechanism mobilises EUR 55 billion (2021-2027) in the affected regions. The Mechanism consists of three key pillars of: (i) Just Transition Fund, (ii) a dedicated scheme under InvestEU, and (iii) a public sector loan facility with the European Investment Bank.

The largest component of the Mechanism, Just Transition Fund is expected to mobilise around EUR 25.4 billion in investments provided for Member States to support economic diversification and reconversion of the most adversely impacted regions. The fund is directed to address various economic and social impacts of environmental policy based on Member States’ Territorial Just Transition Plans and can be used for up- and reskilling, environmental rehabilitation, transforming existing carbon-intensive industries, as well as for social infrastructures (European Commission, 2021[57]).

A number of other tools and non-binding guidance provide the EU Member States with information and knowledge to support the transition to climate neutrality. The Just Transition Platform provides information and guidance on available support measures for the EU territories in transition. It also promotes mutual learning and exchange of knowledge, holding regular events for stakeholders as well as publishing case studies and toolkits. In addition to the sectoral and regional focus of the Just Transition Mechanism, the Council Recommendation of 16 June 2022 on ensuring a fair transition towards climate neutrality draws attention to ‘people and households in vulnerable situation’ who independently of the green transition face disadvantages in terms of access to employment, education or a decent standard of living, recognising the particular vulnerability of certain populations.

Insofar as just transition seeks to address both the uneven labour market impact of environmental policy and pollution, they also advance environmental justice by reducing inequitable exposure while shielding the vulnerable from the income losses and unemployment.

4.4. Challenges in assessing and addressing environmental justice concerns

Copy link to 4.4. Challenges in assessing and addressing environmental justice concernsThis section summarises the findings on what constitutes barriers to integrating environmental justice into environmental policymaking across countries. The findings are based on the following set of questions:

What data or methodological challenges countries face in assessing the risk or exposure of different communities or groups to environmental hazards;

What challenges countries face in addressing issues such as inequitable exposure to environmental hazards, inequitable economic burden of environmental policies, or barriers to participating in environmental decision-making.

4.4.1. Data and methodologies

Copy link to 4.4.1. Data and methodologiesData and methodological challenges in assessing the risks and exposure of different groups to environmental hazards can be considerable. The survey finds that many countries (65%) face these challenges. The most common challenge across countries is limited data availability, with several countries (Chile, France, Germany, Mexico, Peru the United States) and the European Commission highlighting the need for precise and sufficiently granular environmental, socio-economic and demographic indicators that can be integrated at the same level of disaggregation. Although the availability and resolution of environmental data has been enhanced by technology, including satellite imagery,16 demographic data tend to be collected at relatively aggregated level (Weigand et al., 2019[62]). While some additional data may be made available through non-state actors, identifying and leveraging these resources can constitute a challenge (France).

There can also be a complete absence of data on specific issues, for example, on the new risks climate change poses to hazardous activities (Sweden), detailed information on exposure scenarios and exposure factors (South Korea) or a comprehensive registry that identifies the local and Indigenous communities (Mexico). Lack of historical data to measure changes over time (Mexico) and infrequent updates of standardised data (Costa Rica) also pose an important challenge. The European Commission also highlights the difficulties in assessing the impact transnational EU policies might have on communities in other countries, noting the negative social and environmental impact its support for biofuels had in other countries under the first Renewable Energy Directive. For instance, assessment of the impacts the current policy of diversifying sources of raw minerals for the twin transition and importing hydrogen might have in other countries remains challenging. Even when data are available, methodological challenges in the use of data can be paramount, particularly with regard to identifying causal linkages and assessing cumulative impacts, as noted by South Korea, Canada and the United States. Relatedly, the Slovak Republic also highlighted the hurdles in analysing the data through an intersectional lens.

4.4.2. Capacity and resources

Copy link to 4.4.2. Capacity and resourcesCapacity and resource constraints are pertinent to both data and methodologies and policy implementation across most of the countries. Perhaps reflecting the relative lack of dedicated tools that allow for the integrated analysis of environmental, social and economic data (Section 4.2.1), combined use of data is a notable challenge that is further complicated by the need for improvement in the command of economic analysis to inform policy (France). Constructing an index for assessing environmental justice concerns, for instance requires judgements on the relevant and appropriate variables (Shrestha et al., 2016[63]). In addition, a few countries (Costa Rica, Lithuania and Portugal) highlight the budgetary concerns due to, for instance, high cost of conducting additional studies.

As Germany and Lithuania point out, the lack of conceptual clarity of environmental justice and overall complexity of the issue can pose further challenges on the effective use of resources and capacity. For instance, Lithuania highlights that there is lack of information, methodological guidance and best practices on how the assessment can be integrated in the existing procedures. In a similar vein, the Slovak Republic points to the need to develop a framework for the inclusion and consideration of vulnerable groups in policy-making processes.

Furthermore, capacity and resources also play a pivotal role in the context of monitoring and enforcement for ensuring the effectiveness of environmental policy. This is illustrated by the example of South Africa, where the electricity supply crisis hampers the maintenance and repair of air pollution monitoring devices, impeding the collection of necessary data. Relatedly, as the state’s capacity to supply electricity declines, illustrated by frequent power cuts, the quality of air can worsen, due to the surge in reliance on diesel or petrol-run generators, as well as coal or wood combustion (Langerman et al., 2023[64]).

4.4.3. Difficulties in reaching the affected communities

Copy link to 4.4.3. Difficulties in reaching the affected communitiesWhile implementing targeted programmes for the most affected communities can be challenging in general as noted by Croatia, there are also locally specific challenges for data collection and policy implementation. For instance, collecting environmental information can incur the risk of facing violence as mentioned by Colombia. Canada and the United States both note that Indigenous Peoples and Tribes often lack resources to engage in consultations, and in the United States, they also face the challenge of leveraging available federal financial resources. Language barriers can also pose significant challenges. As pointed out by Peru, providing translation is key to ensure equitable access to information and participation for Indigenous communities. This is especially challenging in linguistically diverse countries, such as Peru, where 48 indigenous languages are spoken across the country (Base de datos de Pueblos Indígenas u Originarios, Ministerio de Cultura, n.d.[65]). While some are relatively widespread, such as Quechua with almost 4 million speakers, others are spoken by only a few hundred speakers (ibid).

4.4.4. Co-ordination across different levels of administrations

Copy link to 4.4.4. Co-ordination across different levels of administrationsAnother complexity that adds to the challenge is the need to ensure co-ordination across different agencies and departments. Consensus on environmental issues that involve a wide range of stakeholders can be difficult to attain (South Korea). The multi-faceted nature of environmental justice requires a unified vision and strategy to coordinate policy responses across domains, yet different responsibilities and priorities assigned across different ministries and agencies make the implementation challenging in practice (Germany). Similarly, there is a need for simplifying legal and institutional frameworks (Costa Rica). Inadequate co-ordination between multiple departments can also hinder the integration of data from different sectors (Peru) and those collected at the local level (New Zealand).

These issues can also arise at sub-national levels. For instance, Canadian municipalities are under provincial and territorial jurisdiction and federal options for engaging with communities directly on environmental justice issues are limited. This limits the national administrations’ understanding of the scope of actions taken by sub-national governments and departments, particularly when the sub-national initiatives do not explicitly state advancing environmental justice as an objective. Similarly, in the United States, certain authorities are delegated to states, which creates challenges for standardising consideration of environmental justice across state and federal level decision-making. This also leads to difficulties in tracking the overall progress to identify areas for further action.

4.5. Key insights

Copy link to 4.5. Key insightsMost countries emphasise the procedural aspect of environmental justice, possibly reflecting the influence of international agreements in shaping national approaches to enhance participatory opportunities, and access to information and justice. However, the approaches countries deploy do not appear to specifically focus upon removing barriers for communities for whom meaningful engagement remains a challenge. There are some novel approaches including the use of cultural mediators to engage more effectively with Indigenous communities, that can yield insights for the design and implementation of meaningful engagement. Further research is warranted to understand the extent to which these measures do reduce barriers, and subsequently, improve environmental and social outcomes for the most vulnerable groups.

While countries consider the disproportionate impact of environmental policies, they tend to do so at a relatively aggregated level, such as through a focus on low-income households or the sectoral impact of climate policies. This underscores the scope for applying the inward-looking environmental justice lens to the analysis of differentiated impacts of policies, resulting from the excessive focus on more measurable and quantifiable impacts at the cost of masking less visible impacts. Despite the unequivocal importance and desirability of environmental policies, lack of consideration for their impact on communities may lead to oversight of distinct vulnerabilities.

Despite the variability in approaches, one notable finding of this analysis is that key challenges in advancing environmental justice are often shared across countries. Across many contexts, limited data availability and difficulties in combining different types of data, pose difficulties to informing policies to advance environmental justice. Another significant obstacle is capacity and resource constraints, compounded by the lack of conceptual clarity of environmental justice as well as the difficulties in ensuring national and sub-national efforts add up to contribute towards a unified vision for pursuing environmental justice.

In this context, lessons drawn from the development of a suite of tools, methodologies and approaches to policy measures emanating from across jurisdictions can carry over across different countries. The examples such as the development of screening tools at national and sub-national levels, for instance, can attenuate the challenges of capacity constraints. Complementing these tools that facilitate assessments are approaches of reorienting existing frameworks and laws to consider vulnerabilities of communities. These practices from across countries suggest that there is an important scope for knowledge exchange to address the unifying challenges of advancing environmental justice. Rather than restricting, the value of mutual learning lies in the diversity of approaches across different countries.

References

[65] Base de datos de Pueblos Indígenas u Originarios, Ministerio de Cultura (n.d.), Lista de lenguas indígenas u originarias, https://bdpi.cultura.gob.pe/lenguas (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[6] Butler, B., A. Gripper and N. Linos (2022), “Built and Social Environments, Environmental Justice, and Maternal Pregnancy Complications”, Current Obstetrics and Gynecology Reports, Vol. 11/3, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13669-022-00339-2.

[22] City of Westminster (2022), Environmental Justice Measure, https://www.westminster.gov.uk/about-council/data/environmental-justice-measure (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[30] CONAGEBIO (n.d.), Protección del conocimiento tradicional, https://www.conagebio.go.cr/es/node/69 (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[54] Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (2023), Environment Improvement Plan, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1168372/environmental-improvement-plan-2023.pdf.

[73] Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (2022), Levelling Up Parks Fund: Prospectus, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/levelling-up-parks-fund-prospectus/levelling-up-parks-fund-prospectus.

[43] Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment (n.d.), Green Scorpions, Protecting South Africa’s future, https://www.dffe.gov.za/sites/default/files/docs/publications/greenscorpions_newspaperinsert.pdf.

[23] Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment (n.d.), National Web based Environmental Screening Tool, https://screening.environment.gov.za/screeningtool/#/pages/welcome (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[70] Ebi, K. and K. Bowen (2023), Green and blue spaces: crucial for healthy, sustainable urban futures, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00096-X.

[25] Environmental Health Information System (n.d.), National Environmental Health Survey, https://www.ehtis.or.kr/cmn/sym/mnu/mpm/62002000/htmlMenuView.do (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[39] Environmental Health Intelligence New Zealand (n.d.), Monitoring New Zealand’s Environmental Health, https://www.ehinz.ac.nz/ (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[72] European Commission (2022), National Energy and Climate Action Plan of the Republic of Lithuania for 2021-2030, https://energy.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2022-08/lt_final_necp_main_en.pdf.

[57] European Commission (2021), COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT SWD(2021) 452 final, https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjoqoiDzaqFAxWxUqQEHbKiCl4QFnoECBEQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fec.europa.eu%2Fsocial%2FBlobServlet%3FdocId%3D25029%26langId%3Den&usg=AOvVaw0dzymExom7mKU6zM8bnTMU&opi=89978449.

[59] European Commission (n.d.), About the Just Transition Platform, https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/funding/just-transition-fund/just-transition-platform/about_en (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[58] European Commission (n.d.), Just Transition Fund, https://commission.europa.eu/funding-tenders/find-funding/eu-funding-programmes/just-transition-fund_en (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[60] European Commission (n.d.), Knowledge Repository, https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/funding/just-transition-fund/just-transition-platform/knowledge-repository_en (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[56] European Commission (n.d.), The Just Transition Mechanism: making sure no one is left behind, https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal/finance-and-green-deal/just-transition-mechanism_en (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[69] Falanga, R. et al. (2021), “The participation of senior citizens in policy-making: Patterning initiatives in Europe.”, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, Vol. 18/1, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18.

[37] Federal Ministry for Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (2023), Bundesregierung verabschiedet erstes bundesweites Klimaanpassungsgesetz, https://www.bmuv.de/pressemitteilung/bundesregierung-verabschiedet-erstes-bundesweites-klimaanpassungsgesetz (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[68] Fowlie, M., E. Rubin and R. Walker (2019), “Bringing Satellite-Based Air Quality Estimates Down to Earth”, AEA Papers and Proceedings, Vol. 109, https://doi.org/10.1257/pandp.20191064.

[5] Giudice, L. et al. (2021), “Climate change, women’s health, and the role of obstetricians and gynecologists in leadership”, International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Vol. 155/3, https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.13958.

[67] Harper, K., T. Steger and R. Filčák (2009), “Environmental justice and Roma communities in Central and Eastern Europe”, Environmental Policy and Governance, Vol. 19/4, https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.511.

[50] Instituto Nacional de Derechos Humanos (2011), Informe Anual 2011, Situación de los Derechos Humanos en Chile, https://www.indh.cl/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/27555-Informe-Anual-2011-BAJA1.pdf.

[26] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2023), “IPCC, 2022: Annex II: Glossary”, in Climate Change 2022 – Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

[27] International Labour Organization (1989), C169 - Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, 1989 (No. 169), https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:55:0::NO::P55_TYPE,P55_LANG,P55_DOCUMENT,P55_NODE:REV,en,C169,/Document (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[75] L’Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques (2016), Ethnic-based statistics, https://www.insee.fr/en/information/2388586 (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[3] Landrigan, P., V. Rauh and M. Galvez (2010), “Environmental justice and the health of children”, Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine, Vol. 77/2, https://doi.org/10.1002/msj.20173.

[64] Langerman, K. et al. (2023), South Africa’s electricity disaster is an air quality disaster, too, https://doi.org/10.17159/caj/2023/33/1.15799.

[4] Massimo, F. and P. Mannucci (2018), “Mitigation of air pollution by greenness: A narrative review”, European Journal of Internal Medicine, Vol. 55, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2018.06.021.

[1] Mathew, S. et al. (2023), “Environmental health injustice and culturally appropriate opportunities in remote Australia”, The Journal of Climate Change and Health, Vol. 14, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joclim.2023.100281.

[66] McGregor, D., S. Whitaker and M. Sritharan (2020), Indigenous environmental justice and sustainability, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2020.01.007.

[8] Ministério da Igualdade Racial, Governo do Brasil (2023), Anielle Franco anuncia criação de Comitê de Monitoramento da Amazônia Negra e Enfrentamento ao Racismo Ambiental, https://www.gov.br/igualdaderacial/pt-br/assuntos/copy2_of_noticias/anielle-franco-anuncia-criacao-de-comite-de-monitoramento-da-amazonia-negra-e-enfrentamento-ao-racismo-ambiental (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[31] Ministerio del Medio Ambiente (2024), Plan Nacional de Implementación Participativa del Acuerdo de Escazú 2024-2030, https://mma.gob.cl/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Plan-Nacional-de-implementacion-participativa-del-Acuerdo-de-Escazu-Chile-2024-2030.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2024).

[32] Ministerio del Medio Ambiente (2023), Informe proceso de participación temprana para la elaboración del plan de implementación participativa del Acuerdo de Escazú. Identificación y Análisis de Brechas y Propuestas de Medidas, https://consultasciudadanas.mma.gob.cl/storage/records/mRUmlOP9CwB0dB2dUfxprco1gPBWWl3QDEYbmYSD.pdf.

[33] Ministerio del Medio Ambiente (2023), Ministerio del Medio Ambiente invita a realizar Cabildos Autoconvocados por Escazú, https://mma.gob.cl/ministerio-del-medio-ambiente-invita-a-realizar-cabildos-autoconvocados-por-escazu/ (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[35] Ministerio del Medio Ambiente (n.d.), Diálogos participativos, https://mma.gob.cl/dialogos-participativos/#agenda (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[34] Ministerio del Medio Ambiente (n.d.), Escazú en Chile, https://mma.gob.cl/escazu-en-chile/#pipe (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[51] Ministerio del Medio Ambiente, Gobierno de Chile (n.d.), Programa para la Recuperación Ambiental y Social, https://pras.mma.gob.cl/ (accessed on 23 April 2024).