This section provides a description of the most relevant legal instruments and existing environmental taxes at different governance levels that are relevant for waste management and the circular economy in Andalusia.

Environmental Tax Policy Review of Andalusia

8. Legal stocktake: Circular Economy and Waste Management

8.1. Legal framework, competencies and responsibilities on waste management

At EU-level, the first Circular Economy Action Plan (CEAP) in Europe was approved in 2015 (European Commission, 2015[1]) and, in 2020 the second CEAP was adopted (European Commission, 2020[2]). The CEAP includes 35 actions such as setting waste reduction targets for specific streams and other measures on waste prevention.

The Waste Framework Directive (WFD) is the main regulation on waste in Europe. The WFD sets targets for preparation for re-use and recycling of municipal waste of 55% by 2025, 60% by 2030 and 65% by 2035. In addition, the WFD establishes the basic requirements for Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR). The Packaging and Packaging Waste Directive strengthens the reuse of packaging, setting qualitative and quantitative objectives and the use of economic incentives.

The goal of the Single-Use Plastics (SUP) Directive is to prevent and reduce the impact on the environment of certain plastic products. It bans several single-use plastic products and for other single-use plastics it established design requirements (recycled content of plastic bottles) and set targets for separate collection and for recycled content for PET bottles.

At the Spanish level, Law 7/2022 on Waste and Contaminated Soils for a Circular Economy transposes the objectives of the directives.

Table 8.1. Main legislation and targets in the domain of waste and resources across different levels of government

|

Legal framework / laws / instruments |

Objectives and targets |

|

|---|---|---|

|

EU-level |

Waste Framework Directive [Directive 2008/98/EC] |

|

|

Single Use Plastic Directive [Directive (EU) 2019/904] |

|

|

|

Packaging and Packaging Waste Directive [Directive (EU) 94/62] |

|

|

|

Landfill Directive [Directive (EU)1999/31] |

|

|

|

Plastic Bags Directive [Directive (EU) 2015/720] |

|

|

|

National level (Spain) |

Spanish Law 7/2022 on Waste and Contaminated Soils for a Circular Economy |

|

|

Spanish Royal Decree 293/2018 on the reduction of the consumption of plastic bags |

|

|

|

Spanish Circular Economy Strategy 2030 |

|

|

|

Regional level (Andalusia) |

Decree 73/2012, of the Andalusian Waste Regulation |

|

|

Draft bill of the Andalusian Law on Circular Economy (not yet approved) |

|

|

|

Andalusian Mining Strategy 20201 |

|

Table 8.2. Distribution of the main competences in the domain of waste and resources across different levels of government

|

Matter |

National |

Andalusia |

Local (Municipal) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Waste |

Basic legislation on waste management. The national legislation establishes minimum targets for reducing waste generation, as well as preparation for reuse, recycling and other forms of recovery. The national government approves the National Framework Plan for Waste Management, and it authorises shipments of waste to or from non-EU countries (art. 12.1,2,3 Law 7/2022) |

Policy development of the basic national legislation and establishment of additional protection regulations. The regional government approves regional plans for waste prevention and management. It is also in charge of authorization, inspection and sanction of waste production and management activities. It also registers information on production and authorises waste management of the shipment of waste from or to EU countries (art. 12.4 Law 7/2022). The regional government also can increase the waste disposal tax rates (art. 93.2 Law 7/2022) |

Municipalities are obliged to provide the collection, transportation, and treatment of household waste. Municipalities with more than 5,000 inhabitants are obliged to approve waste management programs. Municipalities can manage commercial waste. Municipalities must establish waste charge to finance the costs of the provided services (art. 12.5 Law 7/2022) |

|

Resources |

Basic mining legislation (article 149.1.25 of the Spanish Constitution and Law 2857/1978 which approves the general regulations for the mining regime) |

Inspection and monitoring of mining activity. Management of mining resources, resource exploitation authorization and exploration permissions (Law 2857/1978 which approves the general regulations for the mining regime). |

Urbanism competences (art. 25.2 Law 7/1985 of the bases of the local regime) |

Andalusia is one of the first AC discussing in its Parliament a draft bill for a circular economy law. According to the legislative proposal approved by the Regional Government in February 2022 (BOPA, 2022), an Andalusian Office of Circular Economy would be created as an administrative unit for the development of advisory functions, dynamization, coordination and management of the actions provided for in the Law (chapter I). The legislative proposal includes the following references to economic instruments:

Article 25.5 states that: “The taxes, charges or, where appropriate, other types of levies, established by Local Entities, in accordance with the provisions of the applicable national legislation, must reflect the real cost of the collection operations, transport and treatment of waste, including the monitoring of these operations and the maintenance and monitoring after the closure of landfills, and should allow progress in the establishment of pay-as-you-throw schemes, without prejudice to the financing obligations that correspond to the Collective Systems of Extended Producer Responsibility in accordance with the national regulations.”

Article 33.1 states that: “In accordance with the principles of respect for the environment and sustainability of the Andalusian port system, set forth in Law 21/2007, of December 18, on the Legal and Economic Regime of the Ports of Andalusia, tax incentives may be established in the rates regulated in such Law for those taxpayers who carry out marine litter collection activities.”

Article 52.3 states that: “Local Entities, within the scope of their competences, may adopt measures of deduction, reduction or discount in charges paid by to those companies, households, neighbourhood communities, or other users, who adopt biowaste composting systems.”

Article 64.1. states that: “The Administration of the Junta de Andalucía may take into account the obtaining of internationally recognised certificates in terms of environmental sustainability of buildings and urbanizations in order to propose rebates in municipal taxes or other tax incentives.”

Due to the elections in Andalusia in June 2022, the Parliament was dissolved, and ongoing legislative processes were temporarily suspended. As such, this draft bill will likely not be approved in the near future.

8.2. Environmental taxes applied in other EU Member States relevant for the study

Based on the OECD database on Policy Instruments for the Environment (PINE) (OECD, 2022[3]), as well as on international studies such as two reports by the European Commission (2021[4]; 2021[5]), three types of environmental taxes were identified as relevant to promote circular economy: 1) waste disposal taxes, 2) taxes on raw materials extraction, and 3) taxes on specific products. This section reviews examples of these environmental taxes in place in other EU Member States.

8.2.1. Waste disposal taxes

Waste disposal taxes are justified by the environmental impacts of landfilling and incineration, compared to other options higher up in the waste management hierarchy established in the Waste Framework Directive (European Parliament, 2008[6]). Thus, such taxes are intended to favour waste prevention and increased recycling levels, and move towards the targets of the Landfill Directive. The incineration tax is often applied to prevent the diversion of waste from landfill to incineration.

According to the OECD database on Policy Instruments for the Environment (OECD, 2022[3]) and the latest version of the CEWEP database on landfill taxes and restrictions (CEWEP, 2022[7]), 26 countries out of 30 (27 EU member states plus Norway, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom) have landfill taxes and 5 have incineration taxes, see Table 8.A.1 for the details, as well as Annex D for case studies in Italy, Belgium and the United Kingdom. As can be seen in Table 8.3, disposal tax rates in European countries vary significantly between countries and types of waste.

In addition to the tax rates, tax policies also vary with modifications. In some countries:

Disposal taxes are supplemented by additional limitations on the quantities that can be landfilled (more stringent than those indicated in Directive 31/1999 on landfill of waste), e.g., Belgium, Sweden, Denmark, Estonia, and Finland.

Disposal taxes are earmarked, e.g., Lithuania, Hungary, Finland, and Austria.

Specific waste types are exempt from disposal tax if no better treatment than landfill is available, such as asbestos in Flanders, Sweden, and the Netherlands, and for waste from waste recovery processes in Sweden, the Walloon region of Belgium and Portugal. In addition, in the United Kingdom landfill operators can offset a maximum percentage of their tax liability by financing environmental projects through the Landfill Communities Fund.

A differentiated tax rate applies. The tax rate can discriminate based on whether the input waste is pre-treated or not prior to landfill, as done in several Italian regions such as Piemonte, Calabria and Campania, or whether the municipality has implemented separate collection of the organic waste, as is the case in Balearic Islands. In other cases, the tax rate is determined based on the percentage of selective collection of the municipality, or on the quality of the waste landfilled, as in the region of Puglia (Italy) or in the Slovak Republic. These tax configurations would provide an extra incentive to improve selective collection and recycling.

Disposal taxes apply to landfill and incineration and generally incineration tax rates are lower than landfill tax rates to incentivise energy recovery over disposal (in line with the waste hierarchy).

Table 8.3. Waste disposal tax rates in European countries, based on Table 8.A.1

|

Taxable Event |

Mean (€/t) |

Standard Deviation (€/t) |

|---|---|---|

|

MSW Landfill |

39.75 |

25.95 |

|

Industrial Waste Landfill |

28.10 |

27.44 |

|

Inert and Construction Waste Landfill |

12.33 |

17.33 |

|

MSW Incineration |

12.19 |

9.04 |

|

Industrial Waste Incineration without energy recovery |

30* |

Note: (*) Standard deviation could not be estimated because there was only one case.

Source: Own elaboration based on data published in (OECD, 2022[3]).

8.2.2. Taxes on raw material extraction

Taxes on the extraction of raw materials have been widespread in Europe since the early 1990s. This type of taxes can reduce demand of primary resources in favour of secondary raw materials while preserving the resource and the landscape.

One of the main raw materials extracted are aggregates. According to the OECD database on Policy Instruments for the Environment (OECD, 2022[3]), there are currently 88 different taxes applied on extractive activities of aggregates, gypsum and salt in OECD countries. More than half of these taxes (58%) are earmarked. 16% are ad valorem, and the remaining (84%) are ad quantum.

In relation to the tax base, 64% of taxes are levied on some specific type of aggregates (e.g., calcareous, marble or clay), 24% to all minerals in general (and therefore also on aggregates), 6% to aggregates in general (all equally), 5% to gypsum and 3% to salt. Table 8.C.1 summarises key aspects of the taxes on aggregates currently applied in 10 of the 30 countries analysed (EU 27 plus Norway, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom). The average tax rate in European countries is shown in Table 8.4.The high standard deviation indicates a great variability between countries.

Table 8.4. Tax rates on the extraction of aggregates in European countries

|

Quantum tax |

Ad Valorem tax |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

€/m3 |

€/t |

Value (%) |

Benefit (%) |

|||||

|

Mean |

Standard Deviation |

Mean |

Standard Deviation |

|||||

|

Raw material extraction (including aggregates) |

1.06 |

1.31 |

1.35 |

1.63 |

10.00* |

2.60* |

||

|

Specific aggregates extraction |

1.34 |

0.84 |

1.58* |

|||||

Note: (*) Standard deviation could not be estimated because there was only one case.

Source: Own elaboration based on data published in (OECD, 2022[3]).

Denmark was one of the first countries to introduce a tax on the extraction of aggregates. In general, there has been a slight decrease in the extraction of these materials since the introduction of the tax in 1977, but it has not resulted in any reduction in the consumption of these materials (Söderholm, 2011[8]). This indicates a relative inelastic demand. Although an increase in the use of recycled materials was observed, this was mainly attributed to the introduction of the landfill tax on construction waste that was implemented in parallel (Söderholm, 2011[8]).

In Sweden, a tax on the extraction of natural gravel has been applied since 1996 to preserve groundwater. It started with a low tax rate, which was raised in 2003. Such increment implied a greater decrease in the consumption of this material. However, the decrease in the extraction of gravel was already significant before the introduction of the tax and could be associated with an increased demand for crushed rock due to its higher quality compared to natural gravel (although its extraction requires higher energy consumption). The decrease in gravel consumption led to an increase in alternative materials with a greater impact on emissions. Therefore, while groundwater quality has improved, emissions have increased. This example highlights the need for careful analysis and possibly additional instruments to avoid burden shifting. The Swedish case also shows that the gradual increase in the tax helps producers to organise themselves, contributes to increasing the elasticity of demand and allows for a better acceptance of the tax (Söderholm, 2011[8]).

In Italy a regional tax on the extraction of aggregates (sand, gravel, and rock) has been applied since the early 1990s. Each region or municipality applies a different tax rate that can vary between €0.41 and €0.57/m3. Each regional authority defines its tax, which is complemented by national legislation. No substantial change in the demand for aggregates has been observed since the implementation of the tax, which indicates a relative inelastic demand that can be associated with the low tax rate (tax payments represent only 5% of the estimated profits of the industry) and the little preparation of the industry to produce and assimilate recycled materials of similar quality, combined with the absence of taxation on landfill of construction and demolition waste (European Environment Agency, 2008[9]).

In 2002, a tax on the extraction of aggregates was introduced in the United Kingdom and its current rate is 2 GBP (EUR 2.45) per tonne of sand, gravel, and rock (on average 20% of the value of the product). Although in this case there has been a decrease in the extraction of aggregates, this decrease began before the implementation of the tax and is related to factors such as the reduction in investment in infrastructure or the existence of a landfill tax on construction waste (European Environment Agency, 2008[9]). Part of the demand shifted towards non-taxed materials capable of substituting the materials subject to the tax, which have become competitive in the presence of the tax. There are some exemptions from the aggregates levy, such as aggregates which are returned to the ground in the same place and in the same form as they were extracted.2

8.2.3. Taxes on consumer products

As it can be seen on Table 8.D.1, there are several consumer products levied with environmental taxes in different OECD counties, e.g., tyres, pesticides, plastic products, disposal tableware. The Danish Packaging tax merits specific analysis in this report since it could be an option to consider in the reform of environmental taxes in Andalusia to complement the Spanish Packaging EPR for specific packaging items, such as the beverage cartons. The Danish packaging tax has been levied since 1978 to reduce waste and increase packaging reuse and recycling rates. Denmark chose to internalise packaging waste management costs through this tax instead of setting up an industry-run producer-responsibility scheme (such as the Green Dot system) as done by many EU countries. The tax was initially divided into a weight-based part and a volume-based one. Exports were tax-exempt to avoid damaging the international competitiveness of Danish producers.

In 2001, the tax rates for the weight-based part of the tax were modified to consider the life cycle environmental impact of each type of packaging, per kilogram. The volume-based tax is a duty per unit of packaging for spirits, wine, beer, and carbonated soft drinks (Danish Ecological Council and Green Budget Europe, 2015[10]). Table 8.D.1 shows the tax rates divided by material and volume.

The management of the tax was difficult due to the large number of producers involved and the complexity of the tax definition (OECD, 2015). By January 2014, the Danish government abolished the weight-based part to reduce the production costs and administrative burdens of firms, but it is still valid on plastic bags, disposable tableware, and PVC foil (Danish Ecological Council and Green Budget Europe, 2015[10]).

Gsell et al., (2022) also propose a Packaging beverage tax for Germany with differentiated tax rates based on the environmental impacts of the material used for the packaging. Latvia instead has a packaging tax, as part of the natural resource tax, which is used as an incentive to join producer responsibility organisations (PRO), as organisations that join a PRO are tax exempted (European Commission, 2021[5]). Norway has also an environmental tax applied to beverage packaging with differentiated rates per material, as well as a basic tax that applies to all single-use packaging.

8.3. Taxes and regulations at national level in Spain

This section describes two fiscal measures included in the Spanish Law 7/2022 on Waste and Contaminated Soils for a Circular Economy3, namely a special tax on non-recycled plastic used in non-reusable packaging and a disposal tax. In addition, this section describes two existing measures currently being applied in Spain that can influence the proposal of fiscal reform for Andalusia. These are the national ban to provide single-use plastic bags and the current regulation and situation of Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR).

It is also important to mention that the Spanish Law 7/2022 on Waste and Contaminated Soils for a Circular Economy includes the implementation of a Deposit-Refund System for single-use beverage containers with volume up to 3 litres if Spain does not meet the target of 70% of separated collection of bottles in 2023 and of 85% in 2027 established in the Directive (EU) 2019/904.

In addition, the White Book for Tax Reform, published in March 2022, proposes the following measures in relation to circularity: intensification and extension of the taxes of the Waste and Contaminated Soil Law, reformulation of municipal charging of waste to link it to pay-as-you-throw systems, creation of a tax on the extraction of aggregates, creation of a tax on nitrogenous fertilizers and to extend and harmonise taxation on certain emissions from large industrial facilities.

8.3.1. Special tax on non-reusable plastic packaging

Article 67 of the Spanish Law 7/2022 on Waste and Contaminated Soils for a Circular Economy creates a special tax that levies production, importation, and acquisition of non-recycled plastic (i.e. virgin plastic) used in non-reusable plastic packaging. The objective of the tax is to incentivise the reduction of non-reusable plastic packaging as well as plastic recycling. The tax rate will be 0.45 euros per kg of non-recycled plastic used in non-reusable packaging (Article 78). The part of recycled plastic will have to be certified by an accredited body with the certification UNE-EN 15353:2008 (article 79). Although the tax is not earmarked, the rationale for its creation is to raise an amount of revenue similar to the cost for Spain of the EU contribution for non-recycled plastic (Castells-Rey, Pellicer-García and Puig-Ventosa, 2022[11]; Puig-Ventosa, 2021[12]). This contribution, known as the Plastics own resource, was introduced on January 2021 and consists as a national contribution based on the amount of non-recycled plastic packaging waste, which represents a new EU revenue source to the 2021-2027 EU budget (European Commission, 2021[13]; Council of the EU, 2020[14]).

Although the law entered into force on the 10th of April 2022, the measures included in Title VII, i.e., the special tax on non-reusable plastic packaging (described in this section) and the national waste disposal tax (described in next section), will enter into force on the 1st of January 2023 (13th final provision of the Spanish Law 7/2022).

8.3.2. National waste disposal tax on landfill and incineration

The national tax on the deposit of waste in landfills, as well as on the incineration and co-incineration of waste, included in the Spanish Law 7/2022 on Waste and Contaminated Soils for a Circular Economy (articles 84-97) aims to disincentivise these disposal operations in Spain.

The tax rate (Article 93.1) differs among waste type and disposal activity. Table 8.5 shows landfill tax rates, Table 8.6 shows incineration tax rates and a sole tax rate of 0 €/tonne applies to co-incineration, regardless of the type of waste co-incinerated (Article 93.1.f). Article 93.2 establishes the possibility for Autonomous Communities to increase the tax rates even though the tax collection will in principle be carried out by the State.

The National Tax Administration Agency or, the offices with analogous functions of the autonomous communities, has the competence for the tax management, liquidation, collection, and inspection (Article 95.1). According to article 97, the tax revenue will be distributed back to the Spanish regions according to the location where the taxable event happens. The Law 7/2022 on Waste and Contaminated Soils for a Circular Economy does not determine how regions must use the revenue generated.

Two additional provisions in this Law are important for Andalusia. The 7th additional provision establishes “1. To the extent that the taxes established by this law fall on taxable events levied by the autonomous communities and this produces a decrease in their income, the provisions of article 6.2 of Organic Law 8/1980” (the provisions of article 6.2 are compensation measures in favour of such AC). “2. The provisions of the previous section will only apply to those taxes of the autonomous communities that are in force prior to December 17, 2020”. “3. The compensation measures in favor of the autonomous communities established based on article 6.2 of Organic Law 8/1980, will be reduced by the amount of the collection received by the corresponding autonomous communities in accordance with the provisions of this law”.

The 21st additional provision establishes that ACs that at the entry into force of the Spanish Waste Law in 2022 had in place a regional tax on the deposit of waste in landfills, incineration, and co-incineration of waste, may maintain their management if the necessary agreements are established. There is strong uncertainty on the practical implications of the two mentioned additional provisions, which will need to be discussed in the future.

Table 8.5. Landfill tax rates included in the Spanish Law 7/2022

|

Landfill (EUR per tonne) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Non-hazardous*** |

Hazardous**** |

Inert***** |

|

|

1. Municipal Solid Waste (MSW) |

40 |

||

|

2. Rejects from MSW treatment |

30 |

||

|

3. Different than 1 and 2 (without pre-treatment required*): General character |

15 |

8 |

3 |

|

4. Different than 1 and 2 (without pre-treatment required*): > 75% of inert waste |

3 (15)** |

||

|

5. Different than 1, 2, 3 and 4: General character |

10 |

5 |

1.5 |

|

6. Different than 1, 2, 3 and 4: With more than 75% of inert waste |

1.5 (10)** |

||

Note: (*) in the terms established in article 7.2 of Royal Decree 646/2020; (**) The amount before the parenthesis is the tax rate for the inert part and the tax rate within the parenthesis applies for the rest of waste component; (***) Article 93.1.a); (****) Article 93.1.b); (*****) Article 93.1.c).

Source: Own elaboration based on the Spanish Law 7/2022 on Waste and Contaminated Soils for a Circular Economy.

Table 8.6. Incineration tax rates included in the Spanish Law 7/2022

|

Incineration (EUR per tonne) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Disposal D10* |

Recovery R01** |

Different than D10 and R01*** |

|

|

1. Municipal Solid Waste (MSW) |

20 |

15 |

|

|

2. Rejects from MSW treatment |

15 |

10 |

|

|

3. Different than 1 and 2 |

7 |

4 |

|

|

4. Different than 1, 2 which have not previously been subject to R02-09, R12, D8, D9, D13 or D14 |

5 |

||

|

5. Different than 1, 2, 3 and 4 |

3 |

||

Note: (*) Article 93.1.d); (**) Article 93.1.e); (***) Article 93.1.f).

Source: Own elaboration based on the Spanish Law 7/2022 on Waste and Contaminated Soils for a Circular Economy.

8.3.3. Ban of single-use light plastic bags

The EU Directive 2015/720 amending Directive 94/62/EC aims at reducing the consumption of lightweight plastic carrier bags from 90 light plastic bags per person at the end of December 2019 to 40 light plastic bags per person by the end of December 2025 (European Parliament, 2015[15]). It also establishes that by 31 December 2018, lightweight plastic carrier bags cannot be provided free of charge at the point of sale. Very lightweight plastic carrier bags may be exempted from those measures.

The Spanish Royal Decree 293/2018, of May 18, on the reduction of the consumption of plastic bags and by which the Registry of Producers was created transposes Directive (EU) 2015/720 into the Spanish legal system. The Decree (see Table 8.7), bans light plastic bags as of 1st of January 2021 and thick plastic bags with less than 50% of recycled plastic as of 1st of January 2020. Thus, after these dates, only providing very thin compostable bags (free of charge), thin compostable bags (prior payment), thick bags with more than 50% recycled plastic (prior payment), and thick bags with more than 70% of recycled plastic (for free) is still allowed. Annex I of the Royal Decree provides indicative prices to be used by establishments to be applied from the 1st of July 2018.

This annual consumption is of plastic bags in Spain is currently well above the maximum consumption levels and envisioned targets (Box 8.1. ).

Table 8.7. Measures and deadlines established to reduce the consumption of plastic bags in the Spanish Royal Decree 239/2018

|

Deadline |

Lightweight plastic bags* |

Thick weight plastic bags** |

Fragmentable plastic bags*** |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1 July 2018 |

Free delivery to consumers is prohibited |

||

|

Exception: Very light plastic bags. |

Exception: If they contain ≥ 70% recycled plastic, they can be delivered against payment. |

||

|

1 January 2020 |

Delivery to consumers is prohibited if it contains < 50% recycled plastic****. If they contain ≥ 50%, they can be delivered after payment. |

Delivery to consumers is prohibited. |

|

|

1 January 2021 |

Delivery to consumers is prohibited. |

||

|

Exception: -Compostable lightweight plastic bags, which can be delivered upon payment. -Very lightweight compostable plastic bags |

|||

Note: (*) with wall thickness below 50 microns; (**) with wall thickness equal or above 50 microns; (***) plastic bags made of plastic materials that include additives that catalyse the fragmentation of the plastic material into microfragments. The concept of fragmentable plastic includes oxofragmentable, photofragmentable, thermofragmentable and hydrofragmentable plastics (Article 3.e of the Spanish Royal Decree 293/2018); (****) The retailer must have documentation provided by the manufacturer that proves this percentage.

Source: (Junta de Andalucía, 2022[16]) and Real Decreto 293/2018, de 18 de mayo, sobre reducción del consumo de bolsas de plástico y por el que se crea el Registro de Productores.

Box 8.1. Evolution of plastic bag consumption in Andalusia

According to the Spanish Association of Plastics Manufacturers (ANAIP), the consumption of non-biodegradable single-use plastic bags per inhabitant in Spain was 300 in 2008, but this consumption dropped in the following years (MITECO, 2022[17]). In 2014, 6,730 million units of lightweight plastic carrier bags (with wall thickness below 50 microns, as defined in Directive (EU) 2015/720) were placed on the market, of which 23% were very lightweight plastic carrier bags (with a wall thickness below 15 microns, as defined in Directive (EU) 2015/720). This means that in Spain there was an average annual consumption of 145 light plastic bags per inhabitant that year (Junta de Andalucía, 2022[18]).

8.3.4. Extended Producer Responsibility Schemes

Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) is defined as the environmental policy that intends to transfer responsibility of the post-consumer phase of the product to the producer (OECD, 2016[19]). The two main reasons for assigning responsibility to producers is: (1) to implement the polluter pays principle and ensure economically efficient recovery and treatment of End-of-Life (EoL) products, and (2) the capacity of producers to change products in the design phase to minimise their environmental impact throughout their entire life cycle.

Although there is evidence that EPR schemes can reduce public costs of municipal waste management while increasing prevention and recycling rates, currently there are only 4 waste streams for which EU directives establish the use of EPR policies (packaging, batteries, end-of-life vehicles (ELVs), electrical and electronic equipment (EEE)) (Eunomia, 2020[20]). Additionally, the EU Single-Use Plastics Directive will require Member Countries to implement EPR schemes for tobacco product filters (i.e. cigarettes) by 2023 and fishing gear by 2025 (European Parliament, 2019[21]) and harmonised EPR rules will be proposed for textiles.

In addition, in some EU countries there are national EPR schemes for products that are not yet addressed in EU-wide legislation (e.g., tyres, graphic paper, used oil and medical waste). In Spain, there are currently six waste flows where EPR is applied: packaging (including Medical Products Packaging and Expired Medicines), batteries and accumulators, EoL vehicles, EoL tyres, used industrial oils and Waste Electric and Electronic Equipment (See Table 8.E.1 for details).

In addition, several additional waste streams are expected to have EPR schemes in Spain in the future:

Article 60.1 of the Spanish Law 7/2022 on Waste and Contaminated Soils for a Circular Economy states that the Spanish government will develop, by regulation, EPR schemes for single-use plastic products listed in Annex IV, part F. These regulations must be established before 6 January 2023 for tobacco products and before 1 January 2025 for food containers, containers and wrappers containing food intended for immediate consumption in the container itself, containers for beverages up to three litres capacity including their caps and lids, drinking glasses including their lids and caps, light plastic bags, wet wipes and balloons.

Article 60.5 of the Spanish Law 7/2022 on Waste and Contaminated Soils for a Circular Economy states that the Spanish government will develop EPR schemes for fishing gear, by regulation, before 1 January 2025. Such regulation will set: 1) a minimum national collection rate for waste fishing gear containing plastic for recycling and 2) the necessary measures to monitor the fishing gear containing plastic placed on the market as well as the waste collected.

Article 60.3 of the Spanish Law 7/2022 on Waste and Contaminated Soils for a Circular Economy states that the producers of tobacco products will bear the costs of collecting the waste of said discarded products in public collection systems, including the infrastructure and its operation and the subsequent transport and treatment of the waste. The costs may include the establishment of specific infrastructure for the collection of the waste of said products, such as appropriate receptacles for waste in places where the dumping of scattered garbage of this waste is concentrated. Likewise, they may include costs associated with measures for the development of alternatives and prevention measures to reduce the generation of waste and increase material recovery.

Finally, the seventh final provision of the Spanish Law 7/2022 states that the Spanish government will develop, by regulation, EPR schemes for textiles, furniture and household items, and non-packaging plastics for agricultural use before 9 April 2025. Besides, in the regulatory developments of the law 7/2022, the application of the EPR scheme to single-dose coffee capsules may be included.

8.4. Taxes used at regional level in Spain

This section describes existing waste disposal taxes applicable in different ACs (including Andalusia) and the regional tax on single-use plastic bags applied in Andalusia.

8.4.1. Waste Disposal Taxes

Eleven Spanish Autonomous Communities (AC) apply taxes on waste landfilling and four AC levy waste incineration. The nature of these taxes is quite heterogeneous regarding type of waste, waste activity, and tax rates (see Table 8.8).

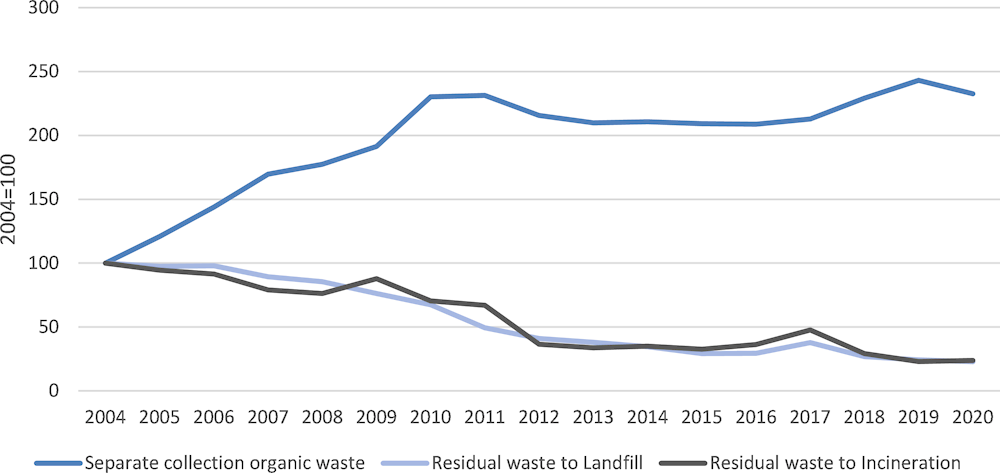

Among ACs with waste disposal taxes, most of them levy industrial waste (all except Balearic Islands) and construction and demolition waste (all except Andalusia, Balearic Islands and Cantabria), fewer ACs levy municipal solid waste (Catalonia, Balearic Islands, Extremadura, Castile and León, and Navarra). Most ACs apply the same fees regardless of the recovery potential of the waste fractions. In some cases, tax rates are higher for recoverable waste in comparison to non-recoverable waste to incentivise waste recovery, where possible (Andalusia, Castile and León and Valencian Community). The tax rate on the Balearic Islands for MSW disposal is reduced by half if the municipalities have implemented separate collection of organic waste. A similar reduced tax rate scheme was also applied in Catalonia from 2009 to 2016. The Catalan Disposal Tax is described in detail in Annex H and the way it is designed and implemented is considered a best practice.

Along with the creation of their taxes, Catalonia and Navarra created specific bodies to manage them and specific waste management funds where the revenue goes.

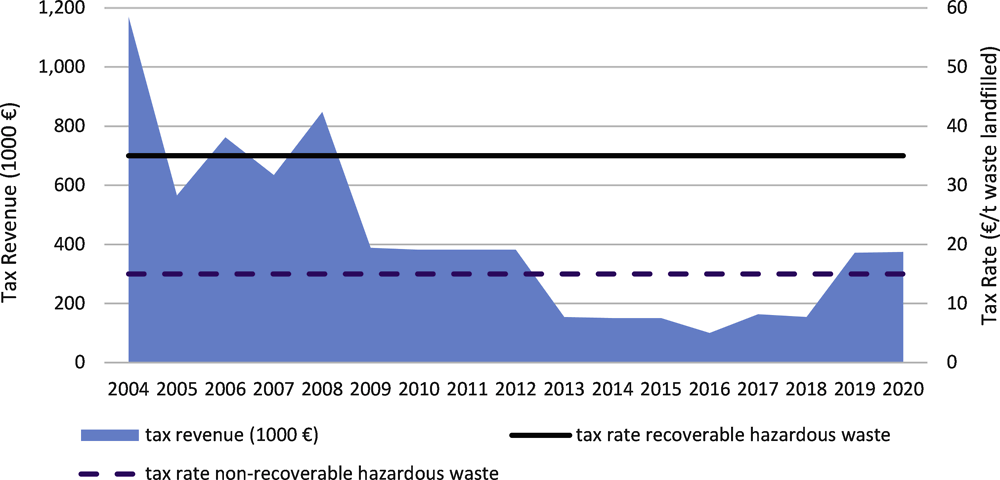

Andalusian Waste Landfill Tax

Law 18/2003, of December 29, approved fiscal measures and administrative regulations in Andalusia. Chapter I of Title II is dedicated to environmental taxes. In this way, the taxes on carbon emissions, dumping into coastal waters, deposit of radioactive waste and deposit of hazardous waste were created. Article 14 establishes that the income proceeding from the abovementioned ecological taxes will be used to finance the actions of Junta de Andalucía in terms of environmental protection and conservation of natural resources, but the law did not set up a separate body to manage the tax and the funds generated, as Catalonia and Navarra did. The Andalusian Tax Agency is responsible for the tax management as well as for the determination and verification, where appropriate, of the environmental parameters that allow the quantification of said taxes (Article 16 of Law 18/2003).

Section V (art. 65 to 77) of the Law 18/2003 specifies the tax on hazardous waste, which came into force in January 2004. The taxable event (art. 67) is “the delivery of hazardous waste in public or private landfills” and “the temporary deposit of hazardous waste in the producer's facilities, prior to its elimination or recovery, when it exceeds the maximum period allowed by law and there is no special authorisation from the Ministry of Environment". Taxpayers are those delivering hazardous waste to a landfill for deposit, as well as those that exceed the temporal period allowed by law for temporary storage prior to elimination or recovery of waste. The tax base (art. 71) is the weight of the hazardous waste deposited and the tax rates depend on whether the waste can be recovered or not, in such a way that it is intended to stimulate preventive treatment (see Table 8.8).

Figure 8.1 shows the evolution of the tax revenue and the tax rate in the period 2008-2020.

Figure 8.1. Andalusian Waste Landfill tax. Revenue and rate for the period 2004-2020

Source: Own elaboration based on the information available in the Portal of the Ministry of Finance and Public Function (2013-2020). Impuestos Propios (Secretaría General de Coordinación Autonómica y Local, 2022[22]).

Table 8.8. Tax rates (€/tonne) of existing waste disposal taxes in Spain, 2021

|

AC |

Activity |

Municipal Solid Waste |

Industrial Hazardous Waste |

Industrial Non-Hazardous Waste |

Construction & Demolition Waste |

Regulation |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Recoverable |

Non-Recoverable |

Recoverable |

Non-Recoverable |

Recoverable |

Non-Recoverable |

|||||

|

Andalusia |

Landfill |

35 |

15 |

|||||||

|

Balearic Islands |

Landfill |

40 (20)1 |

||||||||

|

Incineration |

20 (10)1 |

|||||||||

|

Cantabria |

Landfill |

2 |

||||||||

|

Castile and León |

Landfill |

20 |

7 |

35 |

15 |

20 |

7 |

3 |

||

|

Catalonia |

Landfill |

59.12 |

15.8 |

3 |

||||||

|

Incineration |

29.62 |

|||||||||

|

Extremadura |

Landfill |

12 |

18 |

12 |

3.53 |

|||||

|

La Rioja |

Landfill |

21 |

44 |

12 |

44 |

|||||

|

Madrid |

Landfill |

8 |

5 |

15 |

||||||

|

Murcia Region |

Landfill |

15 |

7 |

3 |

||||||

|

Navarra |

Landfill |

20 |

20, 5, 16 |

36 |

||||||

|

Incineration |

||||||||||

|

Valencia Community |

Landfill |

30 |

30 |

20 |

3 |

|||||

|

(Co-)Incineration |

208 |

207 |

||||||||

1. The lower tax rate reported within brackets applies to municipalities that have initiated the separate collection of organic waste and Pay-As-You-Throw (PAYT) schemes.

2. Tax rates for 2022, see Table 8.F.1 for planned tax rates until 2024.

3. Rate applicable to Inert waste. For the non-inert part of the CDW, a non-hazardous waste tax rate is assumed to be applied.

4. Rate applicable to non-recoverable waste coming from waste treatment facilities.

5. Tax rate per cubic meter of CDW.

6. 20 €/t for non-hazardous waste in general, 5 €/t for industrial non-hazardous mineral residues with low lixiviation, 1 €/t for natural materials excavated (sand and rocks) and industrial inert waste.

7. Without energy recovery.

8. Hazardous waste in energy recovery operations.

Source: Own elaboration based on (Fundació ENT, 2022[23])

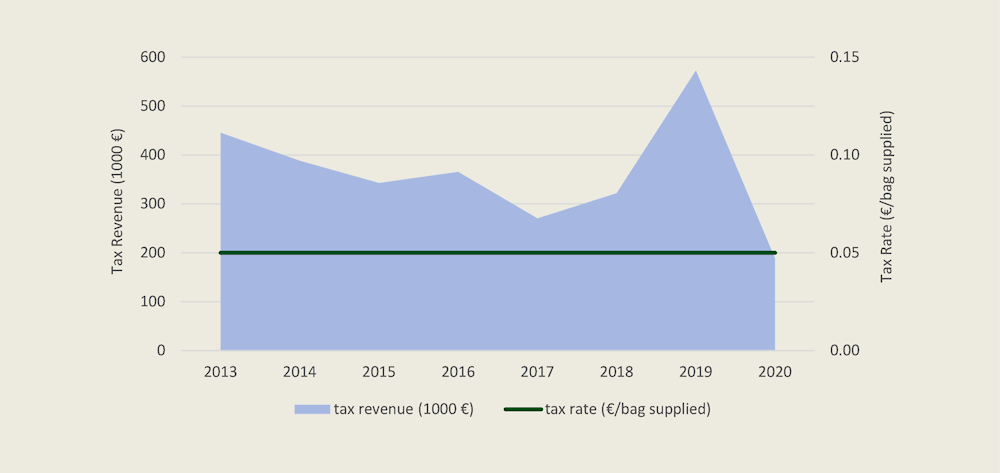

8.4.2. Single-Use Plastic Bag Tax in Andalusia

On 1 May 2011, the Single-Use Plastic Bag Tax came into force in Andalusia, regulated by Law 11/2010, on fiscal measures for the reduction of the public deficit through sustainability, which taxes the supply of plastic bags by commercial establishments located in Andalusia.

The taxpayers are the natural and legal entities owning the commercial establishments where single-use plastic bags are provided to customers. The law does not differentiate between type of plastics bags (e.g., thick, thin, and very thin), but compostable and reusable plastic bags are exempt from the tax. The main aim of the tax was reducing single-use plastic bags consumption, but additional tax revenues for the Junta de Andalucía also motivated the implementation of the tax.

The tax is fully passed on to consumers, and must be stated on the corresponding invoice, receipt, or voucher, as a separate item denoting the number of bags paid for. The tax revenue goes to the general funds of the AC. The tax base is the number of plastic bags provided by the retailer. The tax rate has been 5 cents per single-use bag since 2011 (See Figure 8.2 in Box 8.2. ). An increase to 10 cents was planned, but never implemented

Bags supplied by commercial retail establishments in which the holders are registered exclusively under a heading of group 64 of the Tax on Economic Activities including for instance retailers of exclusively fruits and vegetables, meat, fish or bread. Not part of this exemption are retailers of the sub-groups 645,646 and 647, including for example retailers or wines and beverages, tobacco products or general grocery shops.

Box 8.2. Evolution of tax revenue from Andalusia’s Single-use plastic bag tax

Based on the tax revenue of 2014 (EUR 388,380) and the tax rate (EUR 0.05 per bag), the taxable event in 2014 equalled to 7.77 million bags. Considering the population of Andalusia in 2014 (8.4 million inhabitants), the taxable event per inhabitant corresponded to 0.9 bags per inhabitant per year. This amount is very small compared with the Spanish average annual consumption of 145 light plastic bags per inhabitant reported by ANAIP for the same year (Junta de Andalucía, 2022[18]). This could mean either that the tax was highly effective and reduced almost completely the consumption of taxed single-use plastic bags, that exemptions applied to the establishments of group 64 of the Tax on Economic Activities commercial retail mean a large volume of bags that are not included in the tax revenue, or that some taxpayers are not fulfilling their obligations with regards to the bags delivered in their establishments.

Figure 8.2. Andalusian Plastic bags Tax revenue and rate for the period 2013-2020

Note: According to Junta de Andalucía, in 2019 there was a peak in the supply of non-exempt bags, and it can be seen in the revenue of the same year. While the number of exempt bags decreased by 13%, the non-exempt ones increased by 40.7%. This could be related to the period of adaptation of businesses to the Spanish Royal Decree 239/2018 whose measures came into force in July 2018. In addition, the revenue of 2019 should be interpreted with caution, given that in December 2018 the Andalusian Budget Law for 2019 was not approved, for that the tax rate that applied from January 1 to July 24 of 2019 was 10-euro cents for each single-use plastic bag supplied instead of 5-euro cents. Subsequently, through the 4th Final Provision of Law 3/2019, of July 22, of the Budget of the Autonomous Community of Andalusia for the year 2019, with effect from January 1 of 2019 and indefinite validity (retroactive character), the tax rate was established at 5-euro cents for each single-use plastic bag supplied. Thus, part of the revenue was paid back to taxpayers and the actual revenue (after deductions) was less than the value shown in Figure 8.2.

Source: Own elaboration based on the data available from the Junta de Andalucía.

8.5. Charges at the municipal level in Spain

At municipal level, waste charges are used to finance waste collection and management services. Waste charges are regulated through the fiscal ordinances of each municipality and are often conceived as flat rates or depend on criteria different than waste generation. This lack of connection with the effective waste generation and source separation of each user represents a missed opportunity to incentivise waste prevention and separate collection at local level.

The Observatory on Waste Taxation carried out an assessment of the Spanish waste charges applied over five years (2015, 2018, 2019, 2020 and 2021) by evaluating qualitatively and quantitatively the waste fiscal ordinances of 125 Spanish municipalities (Fundació ENT, 2021[24]). The study concludes that:

Great variability exists among the waste charges applied around the Spanish territory. This heterogeneity can be explained by the flexibility allowed by the Royal Decree 2/2004 on Local Treasuries when designing the charge and by the different configuration of waste collection services at municipal level, which translates into different costs.

Waste charges have increased both for households and commercial activities between 2015 and 2021. However, some regression in the trends was observed in 2021, as some reductions were introduced to alleviate the economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Most of the household waste charges are fixed rates (46.4% of the municipalities), while most of the commercial rates differentiate per "type of activity” and “area of trade”.

The analysis suggests that the potential for waste charges to improve waste management has been hardly exploited. The situation will change with the implementation of the Spanish Waste Law 7/2022, since it contains relevant regulatory reforms applicable to waste charges and specifically foresees the mandatory nature of the waste charges (or equivalent figure, such as public prices or tariffs), as well as the obligation that such a figure covers the full cost of the service. It also establishes that waste charges “must allow for the implementation of pay-as-you-throw schemes” (art. 11.3), which will incentive the adoption of such schemes.

The White Book for Tax Reform recommends reformulating the current municipal waste taxation system to link it to pay as you throw systems.

References

[37] Agència de Residus de Catalunya (2021), “Guia d’orientació als ens locals sobre l’aplicació del retorn dels cànons sobre la disposició del rebuig dels residus municipals per a l’any 2021.”, https://residus.gencat.cat/web/.content/home/ambits_dactuacio/tipus_de_residu/residus_municipals/canons_sobre_la_disposicio_del_rebuig_dels_residus_municipals/guies_i_balancos/guia_canon_2022.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2023).

[11] Castells-Rey, I., P. Pellicer-García and I. Puig-Ventosa (2022), Los instrumentos económicos y fiscales en la Ley de Residuos, Retema, https://www.retema.es/revista-digital/marzo-abril-7 (accessed on 17 January 2023).

[7] CEWEP (2022), Landfill taxes and bans overview - Last update: 28.10.2021, https://www.cewep.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Landfill-taxes-and-restrictions-overview.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2019).

[14] Council of the EU (2020), Council Decision (EU, Euratom) 2020/2053 of 14 December 2020 on the system of own resources of the European Union and repealing Decision 2014/335/EU, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32020D2053 (accessed on 18 January 2023).

[10] Danish Ecological Council and Green Budget Europe (2015), “European expert platform on environmental taxation and green fiscal reform”, https://green-budget.eu/wp-content/uploads/The-Danish-Packaging-tax_volume_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2023).

[35] Danish Ministry of Taxation (2022), The Packaging Tax Act, https://www-skm-dk.translate.goog/skattetal/satser/satser-og-beloebsgraenser-i-lovgivningen/emballageafgiftsloven/?_x_tr_sl=da&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=wapp (accessed on 18 January 2023).

[39] Ettlinger, S. (2017), “Aggregates Levy in the United Kingdom”, https://ieep.eu/uploads/articles/attachments/5337d500-9960-473f-8a90-3c59c5c81917/UK%20Aggregates%20Levy%20final.pdf?v=63680923242 (accessed on 18 January 2023).

[20] Eunomia (2020), Study to support preparation of the Commission’s guidance for extended producer responsibility scheme, https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/08a892b7-9330-11ea-aac4-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 18 January 2023).

[25] Eunomia (2016), “Landfill Tax in the United Kingdom”, http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/tgm/table.do?tab=table&init=1&language=en&pcode=tec00033&plugin=1 (accessed on 29 March 2023).

[32] European Commission (2022), “Environmental Implementation Review 2022 - Country Report - Italy”, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=comnat%3ASWD_2022_0275_FIN (accessed on 29 March 2023).

[5] European Commission (2021), Ensuring that polluters pay: Taxes, charges and fees, https://environment.ec.europa.eu/economy-and-finance/ensuring-polluters-pay/taxes-charges-and-fees_en (accessed on 18 January 2023).

[4] European Commission (2021), “Green taxation and other economic instruments”, https://environment.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2021-11/Green%20taxation%20and%20other%20economic%20instruments%20%E2%80%93%20Internalising%20environmental%20costs%20to%20make%20the%20polluter%20pay_Study_10.11.2021.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2023).

[13] European Commission (2021), Plastics own resource, https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/eu-budget/long-term-eu-budget/2021-2027/revenue/own-resources/plastics-own-resource_en (accessed on 1 February 2022).

[40] European Commission (2021), Taxes, charges and fees, https://environment.ec.europa.eu/economy-and-finance/ensuring-polluters-pay/taxes-charges-and-fees_en (accessed on 29 March 2023).

[2] European Commission (2020), A new Circular Economy Action Plan For a cleaner and more competitive Europe, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2020%3A98%3AFIN (accessed on 18 January 2023).

[33] European Commission (2019), Green Best Practice Community - Treviso, https://greenbestpractice.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ (accessed on 29 March 2023).

[1] European Commission (2015), Closing the loop – An EU action plan for the circular economy, http://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:8a8ef5e8-99a0-11e5-b3b7-01aa75ed71a1.0012.02/DOC_1&format=PDF (accessed on 18 January 2018).

[30] European Environment Agency (2013), Belgium - municipal waste management, https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/managing-municipal-solid-waste/belgium-municipal-waste-management/view (accessed on 29 March 2023).

[9] European Environment Agency (2008), Effectiveness of environmental taxes and charges for managing sand, gravel and rock extraction in selected EU countries, https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/eea_report_2008_2/ (accessed on 18 January 2023).

[21] European Parliament (2019), Directive (EU) 2019/904 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 June 2019 on the reduction of the impact of certain plastic products on the environment, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2019/904/oj.

[15] European Parliament (2015), Directive (EU) 2015/720 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2015 amending Directive 94/62/EC as regards reducing the consumption of lightweight plastic carrier bags, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32015L0720 (accessed on 18 January 2023).

[6] European Parliament (2008), Directive 2008/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 November 2008 on waste and repealing certain Directives, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32008L0098 (accessed on 18 January 2023).

[23] Fundació ENT (2022), Observatori de la fiscalitat dels residus. Impostos., https://www.fiscalitatresidus.org/impostos/ (accessed on 18 January 2023).

[24] Fundació ENT (2021), ‘Evolución de las tasas de residuos en España 2015 - 2021, https://www.fiscalitatresidus.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/EvolucionTasas_2015-2021.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2023).

[38] HMRC UK Government (2020), Guidance: Exempt aggregate and reporting it to HMRC, https://www.gov.uk/guidance/exempt-aggregate-and-reporting-it-to-hmrc (accessed on 18 January 2023).

[29] Interreg Europe (2018), Waste management and Landfill taxes in Flanders, https://projects2014-2020.interregeurope.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/tx_tevprojects/library/file_1539329350.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2023).

[31] ISPRA (2022), Waste Cadastre National Section, https://www.isprambiente.gov.it/en/databases/data-base-collection/waste/waste (accessed on 29 March 2023).

[18] Junta de Andalucía (2022), Bolsas de plástico, https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/medioambiente/portal/areas-tematicas/residuos-suelos-contaminados-economia-circular/tipos-residuos/bolsas-plastico (accessed on 18 January 2023).

[16] Junta de Andalucía (2022), Medidas y plazos establecidos para reducir el consumo de bolsas de plástico, https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/medioambiente/portal/areas-tematicas/residuos-suelos-contaminados-economia-circular/tipos-residuos/bolsas-plastico/medidas-y-plazos-reducir-consumo-bolsas-plastico (accessed on 18 January 2023).

[17] MITECO (2022), Las bolsas de plástico ya no podrán ser gratis, https://www.miteco.gob.es/es/ceneam/carpeta-informativa-del-ceneam/novedades/bolsas-plastico-no-gratis.aspx (accessed on 18 January 2023).

[36] MITERD (2022), Responsabilidad ampliada del productor, https://www.miteco.gob.es/es/calidad-y-evaluacion-ambiental/temas/prevencion-y-gestion-residuos/flujos/responsabilidad-ampliada/ (accessed on 18 January 2023).

[3] OECD (2022), Policy Instruments for the Environment (PINE) Database, https://pinedatabase.oecd.org/ (accessed on 28 June 2022).

[28] OECD (2021), OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Belgium 2021, OECD Environmental Performance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/738553c5-en.

[19] OECD (2016), Extended Producer Responsibility: Updated Guidance for Efficient Waste Management, https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.12022.

[34] OECD (2015), Creating Incentives for Greener Products: A Policy Manual for Eastern Partnership Countries, OECD Green Growth Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264244542-en.

[12] Puig-Ventosa (2021), La fiscalidad en el Proyecto de Ley de Residuos y Suelos Contaminados, https://www.retema.es/articulos-reportajes/la-fiscalidad-en-el-proyecto-de-ley-de-residuos-y-suelos-contaminados (accessed on 18 January 2023).

[22] Secretaría General de Coordinación Autonómica y Local (2022), Capítulo III. Impuestos propios. Tributación Autonómica. Medidas 2009-2020’, https://www.hacienda.gob.es/Documentacion/Publico/PortalVarios/FinanciacionTerritorial/Autonomica/Capitulo-III-Tributacion-Autonomica-2022.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2023).

[8] Söderholm, P. (2011), “Taxing virgin natural resources: Lessons from aggregates taxation in Europe”, Resources, Conservation and Recycling, Vol. 55/11, pp. 911-922, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2011.05.011.

[27] The United Kingdom Government (2022), Excise Notice LFT1: a general guide to Landfill Tax, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/excise-notice-lft1-a-general-guide-to-landfill-tax/excise-notice-lft1-a-general-guide-to-landfill-tax (accessed on 29 March 2023).

[26] The United Kingdom Government (2021), Landfill Tax rates for 2022 to 2023, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/landfill-tax-rates-for-2022-to-2023/landfill-tax-rates-for-2022-to-2023 (accessed on 29 March 2023).

Annex 8.A. Landfill and Incineration taxes in OECD countries

Annex Table 8.A.1. Landfill and incineration taxes for non-hazardous waste in OECD countries

|

Country |

Region |

Year |

Taxable event |

Tax Rate (€/t) |

Earmarked |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Austria |

1989 |

MSW Landfill |

9.2 - 87. Lower rates for landfills with modern technologies |

Yes |

|

|

2006 |

Waste incineration |

8 |

Yes |

||

|

Belgium |

Flanders |

1990 |

Inert Waste Landfill |

19.87 |

Yes |

|

Mineral Waste Landfill |

9.03 |

||||

|

MSW Landfill |

59.33 |

||||

|

1989 |

Waste Incineration and Co-incineration |

8.18 |

Yes |

||

|

Wallonia |

1991 |

MSW Landfill |

66.89; non-valorisable waste: 36.12 €; Stabilised waste: 30.58 € |

||

|

Bulgaria |

MSW Landfill |

50.00 |

|||

|

Denmark |

1987 |

MSW Landfill |

79.00 |

||

|

Estonia |

1990 |

Mineral Waste Landfill |

1.31 |

||

|

Inert Waste and MSW Landfill |

29.84 |

||||

|

Construction Waste Landfill |

0.63 |

||||

|

Slovenia |

2001 |

MSW Landfill |

11.00 |

||

|

Finland |

1996 |

MSW & Non-hazardous industrial waste Landfill |

70.00 |

Yes |

|

|

France |

1993 |

MSW Landfill |

54.00 |

||

|

Greece |

2019 |

MSW Landfill |

15.00 |

Yes |

|

|

Hungary |

2013 |

MSW Landfill |

19.35 |

Yes |

|

|

Ireland |

2002 |

MSW & Non-hazardous industrial waste Landfill |

75.00 |

||

|

Israel |

Construction Waste Landfill |

0.94 |

|||

|

Italy Italy |

Inert Waste Landfill |

5.50 |

|||

|

Mineral and Construction Waste Landfill |

5.68 |

||||

|

2001 |

Inert Waste incineration without energy recovery |

0.2 - 2 depends on the region |

|||

|

2001 |

Non-inert Waste incineration without energy recovery |

1.03 - 5.16 depends on the region |

|||

|

Abruzzo |

MSW Landfill |

25.00 |

|||

|

Aosta Valley |

MSW Landfill |

18.00 |

|||

|

Apulla |

MSW Landfill |

MSW Separate collection: <65% = 20.69; >65% = 12.07; >90% =5.17 |

|||

|

Basilicata |

MSW Landfill |

20.00 |

|||

|

Calabria |

MSW Landfill |

15.50; Pre-treated waste: 5.33; From outside the assigned area to the landfill: 25.82 |

|||

|

Campania |

MSW Landfill |

10.30; Pre-treated waste: 5.2 |

|||

|

Emilia-Romagna |

MSW Landfill |

19.00 |

|||

|

Friuli-Venezia Giulia |

MSW Landfill |

25.82 |

|||

|

Lazio |

MSW Landfill |

15.49; Well separated residue: 10.33 |

|||

|

Liguria |

MSW Landfill |

15.00 |

|||

|

Lombardy |

MSW Landfill |

19.00 |

|||

|

Marche |

MSW Landfill |

25.00 |

|||

|

Molise |

MSW Landfill |

21.00 |

|||

|

Piedmont |

MSW Landfill |

25.82; Pre-treated waste: 12.91 |

|||

|

Sardinia |

MSW Landfill |

25.80; Stabilised waste: 18. |

|||

|

Trentino |

MSW Landfill |

12.86 |

|||

|

South Tyrol |

MSW Landfill |

11.40 |

|||

|

Tuscany |

MSW Landfill |

25.82; Stabilised waste: 21 |

|||

|

Umbria |

MSW Landfill |

25.82 |

|||

|

Veneto |

MSW Landfill |

25.82 |

|||

|

Latvia |

1991 |

MSW Landfill & Non-hazardous industrial waste |

65.00 |

||

|

Lithuania |

Inert Waste Landfill |

30.41 |

Yes |

||

|

MSW Landfill |

10.00 |

||||

|

Malta |

Construction Waste Landfill |

3.26 |

|||

|

Netherlands |

1995 |

MSW Landfill |

33.15 |

||

|

Poland |

MSW Landfill |

46.00 |

|||

|

Industrial waste Landfill |

5.28 |

||||

|

Portugal |

2007 |

MSW Landfill |

22.00 |

||

|

Waste Incineration without energy recovery |

7.70 |

||||

|

UK |

1996 |

MSW Landfill |

98.6 |

||

|

Slovak Republic |

2004 |

Industrial waste Landfill |

7.00 |

||

|

Inert Waste Landfill |

66.00 |

||||

|

MSW Landfill |

MSW separate collection: <10% = 33; <20% = 30; <30% =27; <40% = 22; >50% = 19; >60%=15; > 60%=11 |

||||

|

Czech Republic |

MSW Landfill |

20.00 |

|||

|

Romania |

2019 |

MSW Landfill |

17.00 |

||

|

Sweden |

2000 |

MSW Landfill |

51.00 |

||

|

Switzerland |

Stabilised waste and Construction Waste Landfill |

13.76 |

|||

|

Inert Waste Landfill |

4.30 |

Note: The Spanish regions with waste disposal tax do not appear in this table. These are presented in Table 8.5.

Source: Own elaboration based on (OECD, 2022[3]) and (CEWEP, 2022[7]).

Annex 8.B. Case studies on landfill taxes in other OECD countries

Annex Table 8.B.1. Landfill tax in the United Kingdom

|

Legal bases |

Finance Act of 1996 |

|

Objective |

To encourage efforts to minimise the amount of material produced and the use of alternative waste management options, such as recycling or composting. |

|

Level of responsibility |

Central government (the United Kingdom) |

|

Tax setter(s) |

Central government (the United Kingdom) |

|

Revenue beneficiary(ies) |

Central government (the United Kingdom) |

|

Tax payer(s) |

Operators or controllers of landfill sites transfer the cost to waste producers, the waste industry and local authorities to dispose municipal waste. |

|

Tax base (including main exemption(s), credits or deductions) |

The landfill Tax is charged on material disposed of at a landfill or unauthorized waste site, and the tax base is tons of waste. Exemptions apply to the following waste fractions, disposed at authorised landfill sites:

|

|

Tax rate(s) (including their calculation) |

The tax rate is based on the weight of waste, differentiated by two rates. As of 1 April 2022, the standard rate is GBP 98.6 (EUR 114.49) per tonne and the lower rate amounts to £3.15 (EUR 3.65) per tonne. |

|

Governance and implementation |

The landfill tax was the first UK tax to have an explicit environmental purpose. Nevertheless, it was considered “a popular tax” as it benefited from widespread support from industry, local authorities and NGOs due to the expected use of revenue to partially offset the burden to business (revised in 2003 to only 6%). The final instrument design was fine-tuned during a consultation period, which continued after its implementation. In 1998, it was suggested to increase the tax rates since the previous rates were shown to be insufficient to shift away from incineration towards more investment in recycling. This suggestion was implemented, and since then, the tax rates have been constantly updated (Eunomia, 2016[25]). |

|

Environmental, social & health impacts |

Combined with other policy measures, the tax has significantly contributed to reducing the quantity of waste sent to landfills: in 1996-1997, 50 million tonnes annually were sent to landfill, while it declined to around 12 million tonnes in 2015-2016 (Eunomia, 2016[25]). |

Annex Table 8.B.2. Belgium, Flanders: Tax on Landfilling and Incineration of Waste

|

Legal bases |

Decree of December 23, 2011, on the sustainable management of material cycles and waste |

|

Objective |

To reduce or avoid altogether the landfilling of waste |

|

Level of responsibility |

Region (Flanders) |

|

Tax setter(s) |

Region (Flanders) |

|

Revenue beneficiary(ies) |

Region (Flanders) |

|

Tax payer(s) |

Landfill and incineration operators |

|

Tax base (including main exemption(s), credits or deductions) |

The tax base is the tons of waste. |

|

Governance and implementation |

Landfill taxes and bans on landfilling certain waste streams (e.g., separated waste and untreated municipal waste) have been used to shift from landfilling to incineration and recycling. These instruments are complemented with obligatory separated waste collection, pay-as-you-throw schemes, extended producer responsibility, as well as quotas on waste production per capita. Flanders also applies landfill taxes to waste exported for landfilling with the deduction of any taxes paid in the recipient country (a similar mechanism is used for waste exported for incineration) (OECD, 2021[28]). |

|

Environmental, social & health impacts |

The mix of waste policies in Flanders described above has contributed to reduce the average household waste from 555kg in 2007 to 490kg in 2017, resulting in only 1% of average household waste being directed to landfill sites. In 2012, Flanders only had 17 operational landfills in contrast with 118 in 1985 (Interreg Europe, 2018[29]). |

Annex Table 8.B.3. Tax rate(s) (including their calculation)

Depends on the waste fate and the type of waste:

|

[EUR/t] |

|

|

Landfilling of flammable waste |

101.91 |

|

Landfilling of non-flammable waste |

56.05 |

|

Incineration without permit |

270.84 |

|

Landfilling of household waste that cannot be incinerated in an incinerator |

36.12 |

|

Landfilling of flammable recycling residues (some categories have a lower tax rate = compensation factor) |

101.91 |

|

Landfilling of non-combustible recycling residues (some categories have a lower tax rate = compensation factor) |

56.05 |

|

Landfilling of dredging sludge on a specific site therefore permitted |

0.19 |

|

Landfilling of residues from permitted treatment facilities of sewage sludge |

5.42 |

|

Landfilling of residues from soil remediation |

3.98 |

|

Landfilling of sludge residues from the cleaning of sieving sand |

5.42 |

|

Landfilling of inert waste |

19.87 |

|

Landfilling of ore residues |

9.03 |

|

Landfilling of iron oxide of waste from zinc production |

9.03 |

|

Landfilling of gypsum or calcium waste |

1.81 |

|

Landfilling of immobilized non-flammable waste |

30.58 |

Source: (Interreg Europe, 2018[29])

Annex Table 8.B.4. Regional landfill taxes in Italy

|

Legal bases |

National law 549/1995 and all additional regional laws |

|

Objective |

To improve the waste management cycle by reducing the share of waste being landfilled, making landfills less convenient, supporting waste initiatives to reduce waste generation, and incentivising recycling and energy recovery alternatives. |

|

Level of responsibility |

Regions (Italy) |

|

Tax setter(s) |

Regions (Italy) |

|

Revenue beneficiary(ies) |

Regions and municipalities (Italy) |

|

Tax payer(s) |

Landfill operators |

|

Tax rate(s) (including their calculation) |

The tax rates vary regionally within the maximum threshold of EUR 25.8 per tonne, which is set by the central government. The rates are obtained by multiplying the unit amounts, differentiated by categories of waste, quality and conditions of delivery by the quantity, expressed in tons, of the waste delivered. The categories are the following: (i) urban waste and waste from urban treatment, (ii) inert waste, (iii) non-hazardous special waste, and (iv) special hazardous waste (European Commission, 2021[5]). |

|

Tax base (including main exemption(s), credits or deductions) |

The tax base is the tons of waste. |

|

Governance and implementation |

The landfill tax was introduced on 1 January 1996 to promote the separate waste collection and to support recycling and energy recovery plants. Although a landfilling reduction has been recorded since 1996, 22% of the total municipal waste was disposed of in landfills in 2018, which is far above the EU 10% target set for 2035. The main reason for this is the current relatively low rates of regional taxes. Since 2018, the Italian Regulatory Authority for Energy, Networks and Environment (ARERA) has been leading discussions and open consultation for tax enhancement and determining a “zero landfill” goal. Finally, to increase the effectiveness of the tax, the European Commission has recommended that Italy reforms the tax by increasing the rates and harmonising them across regions (European Commission, 2021[5]). |

|

Environmental, social & health impacts |

Since tax rates are determined at the regional levels, the effectiveness of taxes depend on the region considered. In Veneto, separate waste collection went from 34.4% in 2001 to 76.1% in 2020, whilst in Sicily, it varied from 3.3% to 43.3% in the same period (ISPRA, 2022[31]). Despite the reduction of landfilling, landfilling levels remain above the EU 10% target for 2035. Due to the tax's relatively low levels, it is also unclear whether landfilling decreased because of the tax or due to other mechanisms, such as pay-as-you-throw (PAYT) schemes, the improved sorting and recycling infrastructure, and other incentives (e.g., modulation of fees according to municipalities waste management performance) (European Commission, 2022[32]). For instance, Treviso in Veneto introduced a PAYT system in 2014 where 85 000 residents pay waste fees, which are 60% based on the number of people living in the same household, and 40% varies according to the amount of mixed waste. After the implementation of the tax, the separate collection in Treviso increased from 55% in September 2013 to 80% in December 2014, and the production of mixed waste decreased from 20kg/resident/month to 6kg/resident/month over the same period (European Commission, 2019[33]). |

Annex 8.C. Taxes on Aggregates extraction in OECD countries

Annex Table 8.C.1. EU Environmental taxes on aggregates extraction in OECD countries

|

Country |

Year |

Material |

Ad Quantum tax 2020 |

Ad Valorem 2020 |

Earmarked |

Funds destination |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

(€/m3) |

(% benefit) |

(% market price) |

|||||

|

Estonia |

1991 |

Clay-cement |

0.79 |

Yes (partly) |

Natural regeneration of resources, preserving the environment and repairing environmental damage. In 2014, 44% of the collection went to the general state funds. |

||

|

Clay-ceramic |

0.75 |

||||||

|

Clay-Infusible |

1.42 |

||||||

|

Dolomite-fill |

0.94 |

||||||

|

Dolomite-high quality |

2.36 |

||||||

|

Dolomite-low quality |

1.40 |

||||||

|

Dolomite-technology |

3.34 |

||||||

|

Gravel-construction |

2.43 |

||||||

|

Gravel-fill |

0.60 |

||||||

|

Limestone-fill |

0.98 |

||||||

|

Limestone-finish |

2.94 |

||||||

|

Limestone-high quality |

2.36 |

||||||

|

Limestone-low quality |

1.49 |

||||||

|

Limestone-technology |

2.49 |

||||||

|

Sand-construction |

1.55 |

||||||

|

Sand-fill |

0.42 |

||||||

|

Sand-tech |

1.64 |

||||||

|

Lithuania |

1991 |

Clay, Devonian period |

0.86 |

Yes (partly) |

20% of the revenue is transferred to the municipalities where the material is extracted and the funds are used to finance the Environment Protection Support Program of the municipality. |

||

|

Clay, others |

0.51 |

||||||

|

Clay, Triassic |

0.84 |

||||||

|

Dolomite |

0.99 |

||||||

|

Limestone |

0.84 |

||||||

|

Quartz sand |

1.59 |

||||||

|

Sand |

0.38 |

||||||

|

Construction sand |

0.48 |

||||||

|

Sand used for silicone |

0.44 |

||||||

|

Land used for construction |

0.26 |

||||||

|

Sweden |

1996 |

Natural gravel |

1.58 (2007) |

No |

State general fund. |

||

|

Croatia |

1959 |

Materials (without specifications) |

2.6% (5% in protected areas) (2003) |

Yes |

Investments associated with economic development and environmental protection measures. |

||

|

Cyprus |

1990 |

Materials (without specifications) |

0.26 (1999) |

Yes |

75% of the funds are used to regenerate the environmental damage in municipalities affected by extractive activity, the remaining 25% destined to projects for the restoration of abandoned quarries. |

||

|

Czech Republic |

1991 |

Materials (without specifications) |

3.00(2011) |

Up to 10% |

Yes |

25% allocated to projects for the restoration of abandoned quarries. Economic compensation for damages due to mining activity. |

|

|

Denmark |

2006 |

Materials (without specifications) |

0.7 (2009) |

||||

|

France |

1999 |

Materials (without specifications) |

0.20* |

||||

|

United Kingdom |

2002 |

2.50* |

|||||

|

Italy** |

1998 |

It depends on the region |

Up to 10.5% in Tuscany |

Yes |

50% goes to environmental recovery and remediation of disused quarries and degraded areas. |

||

Note: In the OECD database these taxes appear as: mining charges, mineral extraction charges, natural gravel tax, quarrying charge, aggregates tax and general tax on pollution. The taxes of UK and Italy were not found in the OECD database. (*) Tax per tonne of material (**) Regional tax.

Source: Own elaboration based on the OECD database (OECD, 2022[3]).

Annex 8.D. Consumer products taxes in OECD countries

Annex Table 8.D.1. Consumer products levied with environmental taxes in OECD countries

|

Product |

Country applying environmental tax |

|---|---|

|

Household batteries |

Croatia, Denmark, Hungary, Iceland, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Sweden |

|

Disposable tableware |

Belgium, Denmark, Latvia |

|

Disposal cameras |

Belgium |

|

Aluminium foil |

Belgium |

|

Plastic carrier bags |

Belgium, Denmark, Hungary, Ireland |

|

Packaging items |

Denmark, Latvia |

|

Electric light bulbs |

Denmark, Latvia, Slovakia |

|

Motor vehicle batteries |

Bulgaria, Iceland, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal, Sweden |

|

Car tyres |

Bulgaria, Canada, Croatia, Denmark, Finland, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Portugal, Slovakia |

|

Paint, other solvent-containing products |

Belgium, Canada |

|

Pesticides |

Canada, Denmark, Norway |

|

Vehicles oils and lubricants |

Canada, Croatia, Finland, Norway |

|

Consumer electrical products |

Canada, Hungary, Italy, Malta, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia |

Source: Own elaboration using (OECD, 2015[34]) as main source of information.

Annex Table 8.D.2. Volume-based tax rate of the Danish packaging tax (in DKK/unit for 2022)

|

Volume (cl) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

<10 |

10-40 |

41-60 |

61-110 |

111-160 |

>160 |

|

|

Cardboard or laminate |

0.08 |

0.16 |

0.26 |

0.53 |

0.79 |

1.05 |

|

Other (glass, plastic, metal, etc.) |

0.14 |

0.26 |

0.42 |

0.84 |

1.27 |

1.69 |

Annex 8.E. EPR schemes in Spain

Annex Table 8.E.1. EPR schemes applied in Spain in 2022

|

Waste Flow |

Producer Responsibility Organization |

Spanish Regulation |

EU Directive |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Packaging |

Light packaging (including plastic, metal, beverage carton and paper/cardboard) |

ECOEMBES |

Law 11/2997 Royal Decree 782/1998 |

Directive 2018/852 |

|

Glass Packaging |

ECOVIDRIO |

|||

|

Medical Products Packaging and Expired Medicines |

SIGRE |

|||

|

Phytosanitary Products Packaging |

AEVAE |

Royal Decree 1416/2001 |

||

|

Agriculture Products Packaging |

SIGFITO |

|||