Spain underwent a decentralisation process beginning in 1978 that led to the establishment of a quasi-federal country based on a three-tier system of subnational government. The Spanish multi-level governance framework is complex and characterised by strong political, administrative and fiscal asymmetries at the regional and local levels. This complexity is reflected in the allocation of responsibilities across the different levels of government as well as in the subnational finance system and tax competences, which differ from one region to another. Andalusia, the most populous and the second largest autonomous community by size, is part of this complex system, with its eight provinces and 785 municipalities. Andalusia has extensive responsibilities to develop and implement policy measures related to climate change and the environment.

Environmental Tax Policy Review of Andalusia

1. The multi-level governance framework and tax competences in Spain and Andalusia

1.1. Spain has a complex and asymmetric multi-level governance framework

1.1.1. Spain is a quasi-federal country

Although the 1978 Spanish Constitution established the country as a unitary parliamentary monarchy, Spain is also referred to as “the State of Autonomies” and described as a quasi-federation that has features of both a federal and a unitary country.

Spain has a three-tier system of subnational government whose autonomy is constitutionally recognised (article 137), composed of 17 autonomous communities, 50 provinces, 8 131 municipalities and two Autonomous Cities (Ceuta and Melilla) in 2022. Autonomous communities have a large degree of autonomy, including the exclusive ability to decide on the organisation of municipalities and provinces within their territory, which is often a prerogative of “state governments” in federal countries. However, unlike federal countries, the functions and finances of lower levels of government are determined within the framework of the national law and not by regional constitution or law, like in unitary countries (OECD, 2022[1]).

Like in many federations, regional governments are represented in the Parliament, in particular in the Senate which is meant to be the house of “territorial representation” (art. 69). Out of the Senate’s 266 members, 58 are appointed by the autonomous communities’ regional assemblies (see below). Each autonomous community appoints one senator and an additional senator for every million inhabitants within its territory (art. 69.5), according to a proportional system reflecting the composition of the regional assembly. The Senate has the authority to seize responsibilities from the autonomous communities if the Community is in breach of the Constitution (art. 155) (Gobierno de Espana, 1978[2]).

1.1.2. Spain has an asymmetric system of subnational governance

In addition to being a quasi-federation, Spain also has an asymmetric system of subnational governance, meaning that not all autonomous communities have the same statute of autonomy, resulting in differentiated responsibilities and fiscal systems between communities as well as asymmetries at the local government levels (Allain-Dupré, Chatry and Moisio, 2020[3]; Garcia-Milà and T. McGuire, 2007[4]).

Regional level

At the regional level, the decentralisation process that followed the 1978 constitution paved the way for the development of the autonomous communities, which were subsequently created through complex procedures from 1979 to 1983. The responsibility transfer process was carried out via a two-speed system with seven “fast-track” autonomous communities (vía rápida) that received a broad range of devolved responsibilities immediately and ten “slow track” communities, which received these responsibilities later. Andalusia was part of the “fast track” autonomous communities. Constituted as an autonomous community in February 1980, the first statute of Andalusia was approved in 1981 by the Spanish national government. As of 2003, the “slow track” autonomous communities have assumed all the same responsibilities as the “fast track” ones.

Despite this harmonisation between the fast and slow track autonomous communities, there are some remaining asymmetries between them. First, 15 of the 17 autonomous communities fall under a “common regime”, while the Basque Country and Navarra fall under a “foral regime”, which provides them with special financial responsibilities and more fiscal autonomy than the other autonomous communities from the common regime. Within the common regime, the Canary Islands has however a specific economic and tax system, especially as an EU outermost region. Second, while the autonomous communities are governed by the Constitution, they also have their own organic law, the Statute of Autonomy through which the central government may transfer or delegate some of its responsibilities to the autonomous communities. The law shall provide the appropriate transfer of financial means to the autonomous communities and the type of control that the central government retains regarding the responsibilities (art.150) (Gobierno de Espana, 1978[2]). As a result, autonomous communities each have their specific statute, allowing for some distinctive features. As the responsibilities of the autonomous communities may vary without the need to change the Constitution, provided that their transfer is adopted within this constitutional framework, this differentiation can increase over time. Since the mid-2000s, several statutes have been reformed on a case-by-case basis, for example, in Catalonia and Valencia in 2006, and in Andalusia (Box 1.1), Aragon, and the Balearic Islands in 2007.

As a general rule, regional governing bodies are composed of a regional assembly, the President of the regional government (presidente) and a government council. The regional assembly is the deliberative body of the autonomous communities and has devolved legislative powers. Its members are elected by direct universal suffrage for a four-year term. The President of the regional government is elected from among the regional assembly members for a four-year mandate (absolute majority of voting members). The government council is composed of the regional president and various regional ministers in charge of different offices (Consejerías). Andalusia has some specific institutional characteristics (Box 1.1).

Vertical coordination between the central government and the autonomous communities is made, on a voluntary basis, through the Conference of Presidents (Conferencia de Presidentes), created in 2004. Chaired by the Prime Minister, it includes the presidents of the 17 regional governments and the two autonomous cities and the central government. Vertical coordination also takes place through sectoral conferences such as the Council of Fiscal and Financial Policy (Consejo de politica fiscal y financiera, CPFF) in economic, fiscal and financial matters.

Horizontal cooperation is facilitated through the Conference of the Governments of the Autonomous Communities, which facilitates identifying shared positions of autonomous communities in negotiations with the central government as well as through the Federation of Spanish Municipalities and Provinces at local level.

Local level

At the local level, the Spanish Constitution guarantees the full legal personality and autonomy of municipalities and provinces (art. 140 and 141) (Gobierno de Espana, 1978[2]). As referred to in art. 2.1 of the law 7/1985, “for the effectiveness of the autonomy constitutionally guaranteed to local entities, the legislation of the central government and that of the Autonomous Communities, regulating the different sectors of public action, in accordance with the constitutional distribution of powers, must ensure that municipalities, provinces and islands have the right to intervene in all matters directly affecting their interests, attributing to them the appropriate powers in accordance with the characteristics of the public activity in question and the management capacity of the local entity, in accordance with the principles of decentralisation, proximity, effectiveness and efficiency, and strictly subject to the regulations on budgetary stability and financial sustainability” (Gobierno de Espana, 1985[5]).

Generally, the provinces’ deliberative body is the provincial deputation (diputación provincial), which is composed of members elected by and from the municipal councillors of the province, following municipal elections. The deputation elects a president (presidente de la provincia) from among its members. The Balearic and Canary Islands are organised as “island councils” instead of provincial governments. At the municipal level, the deliberative body is the local council (pleno), whose members are elected every four years by direct universal suffrage. The council is chaired by a mayor (alcalde), elected from amongst the local council members, who is the head of the executive body.

The two Autonomous Cities of Ceuta and Melilla, located in North Africa, are municipalities with more responsibilities, close to those of the autonomous communities. They each hold a special individual Statute of Autonomy, approved in 1985, which establishes their institutional system (i.e. an assembly, a President and a governing council), their responsibilities and their economic and financial structure (The Congress of Local and Regional Authorities, 2013[6]).

Andalusia counts 8 provinces and the largest number of municipalities in Spain: 785 municipalities i.e. 9% of all Spanish municipalities. In 2019, more than 66% of Andalusian municipalities have fewer than 5,000 inhabitants, and in them live just over 10% of the population, occupying approximately 51% of the Andalusian territory (Junta de Andalucia, 2020[7]). There are also some characteristics specific to Andalusia, related to local responsibilities and funding as well as institutional relations between the regional and local governments (Box 1.1).

Vertical coordination between the central government and local governments takes place with the National Commission for local Administration (Comisiòn Nacional de Administracion Local), which was created in 1985. Autonomous communities have their own fora for coordinating with local governments under their jurisdiction, including in Andalusia (Box 1.1).

Horizontal coordination is facilitated by the Federation of Spanish Municipalities and Provinces. Inter-municipal cooperation happens through mancomunidades and comarcas which carry out joint projects or provide common services, for example in the environmental sector (water, waste). There are around 1 000 inter-municipal cooperation entities in Spain, including around 115 in Andalusia (to check and update). The law 27/2013 also promotes the integration or coordination of municipal services (e.g. education, social services, healthcare) through financial incentives.

Box 1.1. Institutional organisation of Andalusia at the regional and local levels

Andalusia was recognised as an autonomous community on February 28, 1980 and its Statute of Autonomy (Estatuto de Atuonomia de Andalucia) was approved by the Spanish government in 1981. A new Statute of Autonomy for Andalusia was approved in March 2007 by the Spanish parliament and by referendum to deepen self-government and the decentralised possibilities enabled by the Spanish Constitution (Junta de Andalucia, 2007[8]). The last regional election in Andalusia was held in June 2022.

The Andalusia Statute established the regional government of Andalusia (Junta de Andalucia), composed of a regional assembly (Parlamento de Andalucía), the President of the regional government (Presidente de la Junta de Andalucía) and a government council. The Statute also established a defender of the Andalusian people (i.e. ombudsperson), a consultative council, a regional chamber of accounts, an audiovisual council of Andalusia and a regional economic and social council.

The main functions of the Parliament of Andalusia are to enact, amend or repeal laws and to appoint and remove the President of the Regional Government. The President of the Regional Government of Andalusia is the executive chief of the Autonomous Community and the representative of the State in daily affairs. The Government Council of Andalusia is in charge of carrying out the executive and administrative functions. The current Council of government is composed of 13 ministries (Junta de Andalucia, 2022[9]).

The Statute recognises Seville as the capital city and the eight provinces that compose the territory of Andalusia (Huelva, Seville, Cordoba, Jaen, Cadiz, Malaga, Granada and Almeria).

The 2007 Statute of Autonomy of Andalusia provides full guarantee and protection of local autonomy. Local autonomy is grounded in art. 92.1 of the Statute, which recognises municipalities’ own responsibilities. Art. 192.1 grants the participation of local governments in the tax system of the autonomous community, through the implementation of a municipal fund of an unconditional nature. The Statute also recognises the full capacity of local self-organisation and the principle of subsidiarity.

The institutional relations between the regional government of Andalusia and local governments are defined in art. 98 of the Statute (Junta de Andalucia, 2007[10]), which was followed by the law 5/2010 on local autonomy in Andalusia (Autonomia Local de Andalucia). As per art. 57 of the law, the Andalusian Council of Local Government (Consejo Andaluz de Gobiernos Locales) was created as the representative body of the municipalities and Provinces before the regional government of Andalusia in order to guarantee the respect of local responsibilities. Through this body, local governments are involved in all parliamentary proceedings and legislation affecting local responsibilities in Andalusia (Junta de Andalucia, 2010[11]). The body adopts its own rules for procedure and organisation. It is composed of local governments’ representatives and five locally elected officials proposed by the association of municipalities and provinces. The president shall be elected by an absolute majority of the council. Additionally, the Andalusian Council of Local Consultation (Consejo Andaluz de Concertacion Local) was established as a joint consultative body, gathering representatives from the regional government of Andalusia, municipalities and Provinces (The Congress of Local and Regional Authorities, 2013[6]).

1.1.3. Allocation of responsibilities across the EU, national, regional and local levels of government

As a member of the European Union, Spain shares some responsibilities with the European Union. According the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), there are three types of EU “competences”1: exclusive, shared, and supporting (i.e. competence to carry out actions to support, coordinate or supplement the actions of the Member States) (European Union, 2012[12]).

Environment is a shared responsibility, for which both the EU and Member States are able to legislate and adopt legally binding acts. Other areas of shared responsibilities that may be related to environment and climate change are social and territorial cohesion, agriculture and fisheries, transport, trans-European networks, and energy.

The EU is obligated to exercise its responsibilities according to the principle of proportionality (i.e. the content and scope of EU action may not go beyond what is necessary) and the principle of subsidiarity (i.e. the EU may act only if the action of Members States is insufficient to achieve an objective for non-exclusive responsibilities).

In Spain, many responsibilities are also shared between the national and subnational levels of government. A major decentralisation process took place with the adoption of the 1978 Constitution and the subsequent laws. In the 2000’s, two major areas of responsibility were transferred from the central government to the autonomous communities (education in 2000 and healthcare in 2002). Reforms of autonomous communities’ statutes were also carried out on a case-by-case, transferring other areas of responsibility.

As per the Spanish Constitution, the autonomous communities may assume responsibilities that do not fall under the central government’s jurisdiction. As a general rule, 23 areas are listed in the Constitution as responsibilities not expressly attributed to the central state and therefore devolved to autonomous communities.

In addition, there are also shared responsibilities between the central government and the regional governments. In particular, they are responsible for the development and implementation of the central government’s basic legislation on economic activity, education, universities, public health, social protection, municipal and provincial supervision and environment as well as for the execution of the central government’s legislation on labour, administration of justice, and intellectual and industrial property. Andalusia, as other autonomous communities, has extensive responsibilities regarding policy measures in the environment and climate sphere, as environmental protection is a regional responsibility. The region has also responsibilities in areas related to the green transition, such as transport, economic development, agriculture and forestry, water management, regional planning and housing (see Table 1.1).

As indicated above, the exact allocation of responsibilities is determined by each Community’s Statute of Autonomy. Conflicts on the overlap of responsibilities between the central and regional governments are settled by the Constitutional Court.

At the local level, the organic law 7/1985 sets the framework of the local government system (Ley reguladora de las bases del régimen local - LBRL) and defines the basis of local responsibilities (Gobierno de Espana, 1985[5]). According to art. 2.1, the allocation of responsibilities in Spain shall respect the principle of subsidiarity, meaning that public responsibilities shall be exercised by authorities which are the closest to citizens (The Congress of Local and Regional Authorities, 2021[13]; Gobierno de Espana, 1985[5]). The organic law adopted in 2013 (Law 27/2013 on the Rationalisation and Sustainability of Local Administration – LRSAL) aimed at clarifying responsibilities between municipalities and provinces and preventing duplication (Gobierno de Espana, 2013[14]; OECD-UCLG, 2019[15]).

Provincial responsibilities are generally defined as ensuring the coordination and provision of municipal services, as well as investment projects of supra-municipal interest. They are in charge of the overall coordination of local government with the autonomous community and the central government, and guaranteeing compliance with solidarity and budget-balance principles among the municipalities they are comprised of. They must provide technical, legal, and economic assistance to small municipalities (fewer than 5 000 inhabitants).

Municipal responsibilities vary between mandatory “core responsibilities” and optional tasks clarified by the law LRSAL, according to their population size. All municipalities are responsible for local services including local public utilities, public lighting, road maintenance and municipal police. Larger municipalities (more than 20 000 inhabitants) have additional responsibilities such as social service allowances, civil protection, public transport and environmental protection.

The devolution of powers to municipalities may differ substantially from one autonomous community to the next. Besides the responsibilities allocated by the law, local governments may also adopt their own rules in accordance with national and regional legislation.

Table 1.1. Responsibilities across the levels of government according to the Constitution and the Statute of autonomy of Andalusia

|

Categories |

Central government |

Andalusia |

Provinces |

Local governments (depending on the size of the municipality) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

General public services (administration) |

Regulation guaranteeing equality of all Spanish in the exercise of their rights; Nationality, immigration, emigration, foreign policy and asylum law; International relations; Post Office services; Basic legislation of public administration; Statistics for general purposes; Authorisation for referendums; Municipal and provincial supervision (shared with the autonomous communities) |

Exclusive responsibilities: Organisation and structure of regional government institutions; Electoral rules and procedures in Andalusia; Management of assets of public domain and patrimonial of Andalusia Shared responsibilities: Legal regime and statutory regime of regional staff; Common administrative procedures; Administrative contracts and concessions |

Internal administration; Coordination of municipalities with the autonomous communities and the central government; Technical, legal, and economic assistance to municipalities with less than 5.000 inhabitants; Provision of public services of supra-municipal character |

Internal administration |

|

Public order and safety |

Defence and security; Justice administration; Commercial, criminal and penitentiary legislation; Procedural legislation; Civil legislation; Intellectual and industrial property; Production and sale of arms and explosives; Public safety |

Exclusive responsibilities: Supervision and protection of regional facilities; Coordination with local police forces; Establishment of Andalusia's public security policies under the terms in art. 149 of the Constitution; Creation, organisation and command of an Andalusian Police; Civil protection |

Municipal police; Civil protection; Firefighting services (municipalities with more than 20 000 inhab.) |

|

|

Economic affairs and transports |

Customs and tariff regulations; Foreign trade; Monetary system; General finances and central government’s debt; National ports, airports, control of air traffic, weather service; Railway and transports of supra-regional interest; Maritime fisheries; Merchant navy and shipping registry |

Exclusive responsibilities: Agriculture, livestock and rural development; Maritime and recreational fishing, aquaculture; Transport (see Part II, Table 2.6); Commercial activity; Cooperatives and social economy entities; Promotion of competition for economic activities in Andalusia; Promotion and planning of economic activity in Andalusia; Industry, except for the responsibilities of central government; Consumer rights; Regional tourism Shared responsibilities: Planning of the fishing sector, as well as for fishing ports |

Cooperation in the promotion of economic and social development and in planning of the provincial territory; Implementation of capital expenditure projects outside the municipal territorial boundaries (including secondary road networks, some hospitals etc.) |

Local public road maintenance (all municipalities); Collective urban transportation (municipalities with more than 50 000 inhab.); Markets |

|

Environment protection |

Legislation, regulation and concession of hydraulic resources when the waters flow through more than one autonomous community; Basic legislation on environmental protection; Organisation of mining and energy |

Exclusive responsibilities: Environment (see Part II, Table 2.4) Energy (see Part II, Table 2.4) Water (see Part III, Table 5.1) Shared responsibilities: Environment (Part II, Table 2.4) Energy (see Part II, Table 2.4) Water (see Part III, Table 5.1) |

Waste collection; Cleaning; Drinking water supply systems; Sewage (all municipalities); Public park; Waste treatment (municipalities with more than 5 000 inhabitants.); Urban environmental protection (municipalities with more than 50 000 inhab.) |

|

|

Housing and community amenities |

Public works of general interest or of supra-regional interest |

Exclusive responsibilities: Housing; Public works or regional interest; Town, land and costal planning Shared responsibilities: Right of reversion in urban expropriations |

Urban policies; Water supply; Public lightning; Cemetery and funeral services (all municipalities) |

|

|

Health |

External health measures; Bases and coordination of health matters; Legislation on pharmaceutical products |

Exclusive responsibilities: Organisation, internal functioning, evaluation, inspection and control of health centres; Research for therapeutic purposes Shared responsibilities: Internal health; Protection and promotion of public health in all areas; Implementation of the central government’s legislation on pharmaceutical products; Planning and coordination in health with the central government |

Participation in the management of first healthcare |

|

|

Culture and recreation |

Basic legislation on the organisation of press, radio, television and social communication; Promotion of Spanish cultural and artistic heritage and national monuments |

Exclusive responsibilities: Museums, libraries and music conservatories of regional interest; Handicraft activities; Artistic and cultural activities in Andalusia; Cultural heritage; Promotion of the regional language; Planning, coordination and promotion of sports and leisure activities; Organisation of recreational activities |

Public library (municipalities with more than 5 000 inhab.); Sport facilities (municipalities with more than 20 000 inhab.) |

|

|

Education |

Promotion and coordination of scientific and technical research; Regulation on academic degrees and professional qualifications; Education (shared); Universities (shared) |

Exclusive responsibilities: Early childhood education; Programming and coordination of the Andalusian University system, creation of public Universities and authorisation of private Universities; approval of the Statutes of public Universities; funding of Universities; remuneration for staff; Organisation, control, monitoring and accreditation of research centres in Andalusia Shared responsibilities: Establishment of curricula and issuance of academic and professional qualifications in non university education; All matters other than those referred above regarding Universities; Coordination of the research centres of Andalusia |

||

|

Social protection |

Legislation and financial system of the Social security; social assistance (shared) |

Exclusive responsibilities: Social services; Volunteer work; Social protection of minors; Social protection of family and child |

Social service allowances (municipalities with more than 20 000 inhab.) |

Source: Author’s own elaboration based on (Gobierno de Espana, 1978[2]; Junta de Andalucia, 2007[8]; OECD-UCLG, 2022[16]).

1.2. Subnational government finance in Spain and tax competences across levels of government

1.2.1. Subnational government finance in Spain

Provisions on fiscal matters relating to subnational governments are detailed in Articles 156, 157 and 158 of the Constitution, in law 22/2009 on the financing of autonomous communities and the Basic Law on Local Government 7/1985, revised in 2013 by the LRSAL, as well as in the successive Budgetary Stability Acts adopted in 2001, 2006, 2009 and 2012. Most fiscal powers are concentrated in the autonomous communities, to the detriment of local governments (OECD-UCLG, 2022[17]).

The two autonomous communities of the foral system (Basque Country and Navarra) have an almost complete spending and revenue autonomy. They benefit from all taxes, except import duties, payroll taxes, VAT and excise duties, under the condition that the overall effective tax burden does not fall below that of the rest of Spain. Besides, within the common regime, the Canary Islands has a specific economic and tax system due to historical and geographic reasons and its status as an EU “outermost region”. The particularities of the “foral” territories and of the Canary Islands are mentioned in the Additional Provisions of the Spanish Constitution.

The rest of the Autonomous Communities have a more homogeneous financing system. Under the common regime, as per article 157 of the Constitution, the autonomous communities receive revenue from different sources: taxes (own-source and shared), user charges and fees (see Box 1.2 for definitions), inter-government transfers including grants from the central government and the inter-regional clearing fund2, property and private law income and revenues from financial operations (Gobierno de Espana, 1978[2]). This constitutional framework was completed by the organic law 8/1980 on the Financing of the autonomous communities (LOFCA) and by the Statutes of Autonomy.

Box 1.2. OECD definition of taxes, user charges and fees

It is not always straightforward to distinguish between user charges and fees that are treated as taxes and those that are not, since the strength of the connection between a charge or fee and the service provided may largely vary, as well as the amount of the charge or fee and the cost of service provision. The OECD Interpretative Guide to Revenue Statistics provides a definition of taxes and user charges and fees, which is used as a reference in this report. The Guide also provides examples of borderline cases where user charges and fees could be considered as a tax.

Taxes: the term “taxes” is defined as compulsory unrequited payments to the general government or to a supranational authority. Taxes are unrequited in the sense that benefits provided by government to taxpayers are not normally in proportion to their payments. The term does not include fines, penalties and compulsory loans paid to government.

Fees, user charges and licence fees: where the recipient of a service pays a fee clearly related to the cost of providing the service, the levy may be regarded as requited and would not be considered as a tax. The main charges and fees include court fees, driving licence fees, harbour fees, passport fees, radio and television licence fees where public authorities provide the services, etc.

In the following cases, however, a levy could be considered as ‘unrequited’:

where the charge largely exceeds the cost of providing the service;

where the payer of the levy is not the receiver of the benefit (e.g., a fee collected from slaughterhouses to finance a service which is provided to farmers);

where government is not providing a specific service in return for the levy which it receives even though a licence may be issued to the payer (e.g., where the government grants a hunting, fishing or shooting licence which is not accompanied by the right to use a specific area of government land);

where benefits are received only by those paying the levy but the benefits received by each individual are not necessarily in proportion to his payments (e.g., a milk marketing levy paid by dairy farmers and used to promote the consumption of milk).

For the purpose of this report, the term “levy” refers to both taxes and user charges and fees.

Source: (OECD, 2021[18])

Recent fiscal decentralisation reforms modified the subnational financing structure, resulting in a significant increase in tax revenue as a percentage of total subnational government revenue. In particular, the organic law 22/2009 on the financing of the autonomous communities has introduced major changes including on subnational taxation (increase in the regional shares of shared taxes), a reform of the equalisation system and a change in intergovernmental transfers. Despite the reform, inter-governmental transfers remain the primary source of regional government revenue (Box 1.3).

As per the Constitution and laws, local governments have the capacity to regulate their own finances, which includes the power to establish their own taxes, to benefit from spending autonomy and to receive revenue from an unconditional nature from higher levels of government. In Andalusia, the 2007 Statute of Autonomy also grants local governments with the principles of autonomy, fiscal responsibility, equity and solidarity in Andalusia. It also stipulates that local governments shall have sufficient resources for the provision of local services.

Box 1.3. Subnational government finance in 2020: key data

Spain has undergone thorough decentralisation in recent decades, shifting from a highly centralised system before 1978 to a highly decentralised one.

Today, Spain is one of the most decentralised countries in the OECD, with subnational governments responsible for almost half of total public spending in 2020 (i.e. 47.3%), amounting to 24.8% of GDP. This lies above the OECD average (respectively 36.6% and 17.1%) and the average for OECD federal countries (respectively 43.5% amounting to 20.6% of GDP)1. The regional level represented almost three-quarters of total subnational government expenditure, while the local level accounted for the remaining (see the below note for the scope of fiscal data).

Spanish subnational governments are responsible for almost all public spending in health, education, environmental protection, and housing and community amenities. The autonomous communities, in particular, play a crucial role in infrastructure investment, research and development, and economic development policies. Subnational government direct investment represented 67.1% of total public investment in 2020, above the OECD average (54.6%) and the OECD average for federal countries (61.5%).

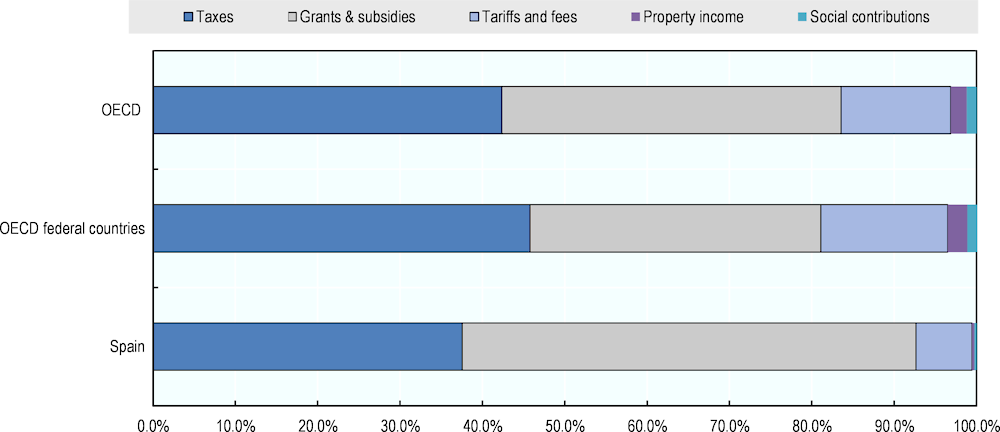

On the revenue side, tax revenue accounted for almost 40% of total Spanish subnational government revenues (37.5%) in 2020. This lies below the OECD average (42.4%) and the OECD average for federal countries (45.8%) (Figure 1.1). Tax revenue of subnational government amounted to 9.3% of GDP and 40.8% of total tax revenue in Spain, similar to the OECD average for federal countries in terms of GDP but below the average in terms of total tax revenue (44.5%). By contrast, the share of grants and subsidies in Spanish subnational government revenue remained quite high compared to other OECD federations (respectively 55.1% vs. 35.4%).

Figure 1.1. Subnational government revenue breakdown in all OECD countries, OECD federal countries and Spain in 2020

At the regional level, tax revenue represented 35.5% of regional revenue in 2020, while grants and subsidies represented 60.2% of revenue and tariffs and fees 6% (OECD-UCLG, 2022[17]). At the local level, tax revenue represented 48.8% of local government revenue in 2020, while grants and subsidies accounted for 41.2% and tariffs and fees 9% (OECD-UCLG, 2022[17]).

Note: The scope of fiscal data for Spanish subnational governments encompasses: (i) at the “regional level”: autonomous communities, regional administrative agencies, regional universities and regional corporations that are non-market producers; (ii) at the “local level”, local authorities (municipal, provincial and islands), associations and groupings of municipalities, autonomous cities (Ceuto and Melila) and bodies reporting to them (e.g. public organisations, corporations and foundations).

1. OECD federal and quasi-federal countries include Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Germany, Mexico, Spain, Switzerland and United States.

Source: (OECD-UCLG, 2022[17]).

1.2.2. Tax competences across levels of government

The EU has limited competences on tax policy, which remain in the hands of Member States. Tax proposals at the EU level typically require unanimity voting at the Council of the EU. The EU shall ensure harmonisation of legislation concerning turnover taxes, excise duties and other forms of indirect taxations under art. 110 to 113 (European Union, 2012[12]).

The primary power to raise taxes in Spain is provided to the central government by the 1978 Spanish Constitution (art. 133). However, the autonomous communities and local governments benefit from “assigned taxes” (shared taxes) and may also establish and raise taxes in accordance with the Constitution and legislation (Gobierno de Espana, 1978[2]).

Parts of the Spanish tax system is currently under review. The “White Book for the reform of the tax system and its adaptation to the reality of the 21st century” (White Book for Tax Reform in Spain, Comité de personas expertas (2022[19]) published on March 2022 proposed a diagnosis of the tax system, including on environmental taxation.3

Autonomous communities’ taxes

Under the foral regime, the Basque Country and Navarra have higher fiscal autonomy compared to other autonomous communities. They benefit from a full autonomy on all taxes, except import duties, payroll taxes, VAT and excise duties. They can establish and regulate their own tax system without sharing taxes with the central government. They should however keep a similar tax pressure as the rest of the country and have to provide part of their revenue (cupo) to the central government.

For autonomous communities that are under the common regime, autonomous communities may act as “delegates” or “collaborators” of the central government for tax collection, management and settlement of the central government’s tax revenue, in conformity with the law (art. 156). Tax competences are also defined in each Statute of Autonomy, such as the Andalusia’s one (Box 1.4).

Autonomous communities may (i) have “assigned taxes” from the central government according to tax sharing arrangements (wholly or partially), (ii) put a surcharge on central government’s taxes, or (iii) establish own-source taxes and special levies provided that they do not levy a taxable fact already levied by the central government or by the municipalities, which explains why most own-source regional taxes are on environmental facts.

Newly created taxes established by the central government, which were originally levied by the autonomous communities and represent a reduction in the autonomous community’s revenue, requires compensatory measures in favour of the autonomous communities.

Likewise, newly created taxes established by the autonomous communities, which were originally levied by the municipalities and entail a decrease in the municipality’s revenue, requires compensatory measures in favour of the municipalities (art. 6) (Gobierno de Espana, 2009[20]).

Under the common regime, the “assigned taxes” imply that the central government is responsible for the establishment and regulation of these taxes, while the revenue is wholly or partially shared and distributed to the autonomous communities (art. 10) (Gobierno de Espana, 2009[20]). Autonomous communities have some leeway on assigned taxes (ceilings on rates, tax exonerations and exemptions, etc.). For example, in the context of the personal income tax (PIT), they are able to increase or decrease tax exemptions on the regional share (e.g. max. of 10% greater or less than the national level; art. 69 ley 35/2006) and can also have discretion regarding the number of tax brackets, although they must have a progressive rate scale (art. 46 ley 22/2009).

Taxes assigned to the autonomous communities include the following:

assignment of 50% of the personal income tax (PIT) receipts (impuestos sobre la renta de las personas fisicas; IRPF) (instead of 33% before the 2009 tax reform);

assignment of 50% of the value added tax (VAT) receipts (impuestos sobre el valor añadido);

assignment of 58% of the receipts from excise taxes (impuestos sobre consumos especificos) on beer, wine and fermented beverages, intermediate products, alcohol and derived beverages, hydrocarbons and tobacco products;

assignment of the full receipts from the electricity tax and certain means of transport (vehicle registration tax), the wealth tax, inheritance and gift/donation tax, tax on capital transfers and documented legal acts (stamp duty), gambling tax and vehicle excise tax.

Autonomous communities may establish surcharges on these “assigned taxes”, as well as on non-assigned taxes at the national level that tax the income or assets of persons with residence within their territories, provided that the surcharges does not imply a reduction in the central government’s revenue, nor distort their nature or structure (art. 12) (Gobierno de Espana, 2009[20]).

Own-source taxes are created by the autonomous communities and shall

be on assets located or income or expenditure originated within their territory, and

not harm the free movement of persons, goods and capital services, nor affect the location of residence of persons or the location of companies and capital within the country (art. 9) (Gobierno de Espana, 2009[20]).

The autonomous communities may also establish fees on the use of their public domain, on the provision of a public service or the performance of an activity that affects the taxable person, with an expected return that do not exceed the cost of these services or activities. When the central government or municipalities transfer goods of public domain to the autonomous communities, the fees levied on the services or activities related to these specific goods are also transferred to the communities (art. 7) (Gobierno de Espana, 2009[20]).

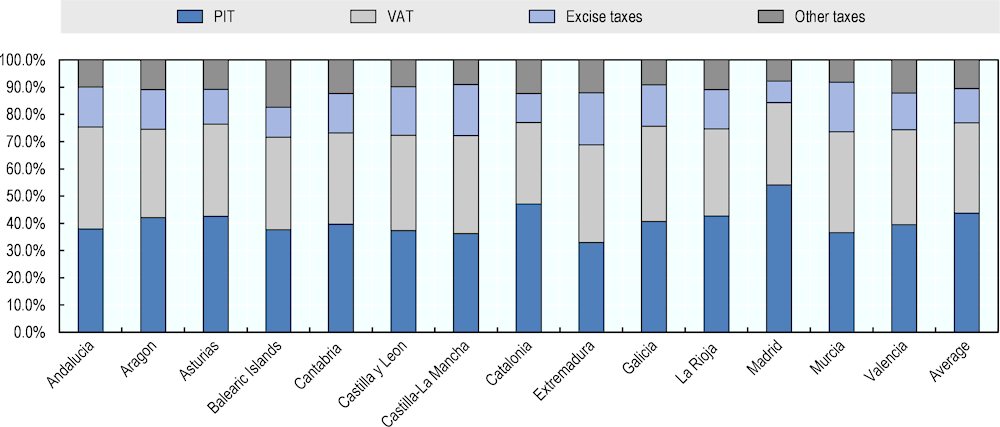

In Andalusia, the PIT represented 37.9% of tax revenue in 2020, the VAT 37.5%, excise taxes 14.8% and other taxes the remaining 9.8%, below the averages of autonomous communities (respectively 43.7%, 33.1% and 12.6%, excluding the Basque Country, Navarra and the Canary Islands that have specific financing systems). (Figure 1.2) The autonomous communities under the common regime do not receive corporate income tax (CIT) receipts.

Figure 1.2. Revenues from PIT, VAT and excise taxes as a share of total tax revenue in autonomous communities in 2020

Note: The Basque Country, Navarra and the Canary Islands are not presented in the above figure as they have a specific financing system.

Source: Author’s own elaboration based on (Ministerio de Hacienda y Funcion Publica, 2022[21]).

The Superior Council of Tax Coordination, made up of representatives of the central government’s tax administration and the autonomous communities, is responsible for coordinating the management of “assigned taxes”, together with the Territorial Councils for Tax Coordination and Management that operate within each autonomous community’s territory (OECD-UCLG, 2022[17]).

Three quarters (75%) of tax revenue from the autonomous communities goes to the Guarantee Fund for Basic Public Services (Fondo de Garantía de Servicios Públicos Fundamentales) (the rest being central government’s contribution), which is an equalisation fund to ensure that each autonomous community receives the same revenue according to its need to finance essential public services. The redistribution is based on an adjusted population criterion.

Box 1.4. Tax competences of the Autonomous Community of Andalusia

Under the 2007 Statute of Autonomy, art. 180 provides that Andalusia is responsible for the establishment and regulation of its own taxes, as well as their management, settlement, collection, inspection and review (Junta de Andalucia, 2007[10]). Andalusia established several own taxes, user charges and fees, of which several that are related to the topic of the present report: the tax on underused land, the tax on gas emissions into the atmosphere, the tax on discharges into coastal waters, the tax on deposit of radioactive waste, the tax on the deposit of hazardous waste, the charge for the improvement of hydraulic infrastructures of interest of the autonomous community, the tax on customer deposits with credit institutions and the tax on single-use plastic bags.

Regarding “assigned taxes” that have been fully transferred to Andalusia by the central government, the autonomous community exercises the regulatory powers and, by delegation of the central government, the management, settlement, collection, inspection and review of these taxes, in accordance with the law that establishes the scope and conditions of the assignment.

For the other “assigned taxes” that have not been fully transferred to the autonomous community, the management, settlement, collection, inspection and review are entitled to the central government, without prejudice to the collaboration that may be established between the central government and the community (art. 180) (Junta de Andalucia, 2007[10]).

A Tax Agency has been created for the purpose of managing the above-mentioned tasks associated to own and assigned taxes in Andalusia (Agencia Tributaria). The Tax Agency may also collaborate with other administrations (art. 181) (Junta de Andalucia, 2007[10]).

Provincial and municipal taxes

The Spanish Constitution grants provinces and municipalities the autonomy to manage their respective interests. Each Statute of Autonomy also grants local governments with principles of fiscal autonomy, fiscal responsibility, equity and solidarity, like in Andalusia (Box 1.5).

Provinces have the power to levy a surtax on the local business tax and are also entitled to some shared tax revenue (PIT, VAT and CIT). They do not have own-sources taxes.

Municipalities can finance their responsibilities through their own taxes and assigned taxes from the autonomous communities and the central government (art.142) (Gobierno de Espana, 1978[2]).

Across all communities, municipal own-source tax revenue represents the main source of revenue, which includes a property tax (IBI), a vehicle tax (IVTM), a local business tax and two optional taxes (a tax on the increase in the value of urban land “IIVTNU – plus valia” and a tax on construction, facilities and infrastructure). Given their extended scope of responsibilities, larger municipalities (more than 75 000 inhabitants) have a special status and benefit from additional assigned taxes (PIT, VAT and excise taxes).

Although this is rarely used, municipalities can also raise environmental-related taxes (OECD-UCLG, 2022[17]), such as the circulation tax or fees for the provision of water supply, sewage and wastewater treatment services. Unlike regions, municipalities are not allowed to create new taxes. Local taxes should be listed in a national law.

Box 1.5. Tax competences of local governments in Andalusia

According to the 2007 Statute of Autonomy, Andalusian local governments are responsible for the management, collection and inspection of their taxes, without prejudice to the delegation or collaboration they may establish with other levels of government (art. 191) (Junta de Andalucia, 2007[10]).

Art. 192 of the Statute defines the collaboration between local governments and the autonomous community. Local governments shall participate in the tax system of the autonomous community through the implementation of a municipal levelling fund of an unconditional nature.

They may also delegate to the autonomous community the management, settlement, collection and inspection of their own taxes or through other forms of collaboration.

Regarding the taxes they share or unconditional subsidies they receive from the central government, local governments shall receive them through the autonomous community, which then redistribute them according to criteria established by the law. The article also specifies that any allocation of responsibilities shall be accompanied by appropriate compensation (Junta de Andalucia, 2007[10]).

The White Book for Tax Reform in Spain

Parts of the Spanish tax system is currently under review. The Secretary of State for Finance has commissioned a Committee of 17 external experts to work on a “White Book for the reform of the tax system and its adaptation to the reality of the 21st century” (Libro Blanco para la reforma del sistema tributario y su adaptación a la realidad del siglo XXI). Published on March 2022, the White Book elaborates a diagnosis of the tax system as a whole and includes specific analyses in the domain of environmental taxation, corporate taxation, property taxation, the digital economy and the promotion of innovation (Comité de personas expertas, 2022[19]). The present analysis considers the proposals and considerations in the area of environmental taxation put forward in the White Book where relevant.

Chapter 2 of the White Book is fully dedicated to environmental tax reform, which is at the centre of the current report. In total, the Committee has formulated 19 proposals and included analyses in the following domains: electricity, transport, waste and water. The proposals and recommendations of the Committee have a technical basis (environmental, socioeconomic and legal), an analysis of significant experiences in other countries and existing academic evidence, and are specified in recommendations that are judged viable from an administrative and management point of view. When the information is available, the Committee's proposals are accompanied by quantitative simulations of their environmental, distributive and revenue impacts. According to a recent report, the IMF estimates that a harmonisation of environmental taxes in Spain with EU average would represent an additional 0.7 to 0.9 point of GDP (IMF, 2022[22]).

Among the proposed measures, the Committee considers that transport and energy are two of the priority action sectors for reviewing current taxation. In addition, it emphasises the importance of improving the existing water and waste taxation design, as these are sectors where the challenges are of great relevance for Spanish society. The proposals for environmental tax reform are presented in the Table 1.2 below and further detailed in the respective sections of the report.

Table 1.2. Environmental tax reform proposals put forth by the White Book

|

Environmental areas |

Proposals |

|---|---|

|

Electricity |

1. Elimination of the tax on the value of electricity production 2. Introduction of measures to improve the design and effectiveness of regional taxes with effects on the electric sector 3. Modifications in the electricity tax to promote electrification and energy efficiency |

|

Transport |

4. Taxation of aviation, maritime and agricultural fuels 5. Equalisation of the taxation of diesel and automotive gasoline 6. General increase in taxation of hydrocarbons 7. Modification of the registration tax to promote a sustainable vehicle fleet 8. Configuration of the circulation tax to penalise the most polluting technologies 9. Creation of a municipal tax on congestion in certain cities 10. Consideration of tax mechanisms for the use of certain road infrastructures 11. Creation of a tax on airline tickets |

|

Waste |

12. Intensification and extension of the taxes of the law on waste and contaminated soils 13. Reformulation of municipal waste taxation to link it to generation payment systems* 14. Creation of a tax on gravel extraction 15. Creation of a tax on nitrogenous facilities 16. Extend and harmonise taxation on certain emissions from large industrial and livestock facilities |

|

Water |

17. Introduction of coordination and cooperation measures to improve the design and effectiveness of regional taxes on environmental damage to water 18. Reform of taxes associated with coverage of hydraulic infrastructure costs 19. Creation of a tax on the extraction of water resources |

Note : The Spanish Agency for Fiscal Responsibility (AIREF) is currently working on a spending review of the regional and local cycle for waste treatment (Autoridad Independiente de Responsabilidad Fiscal, 2022[23]).

References

[3] Allain-Dupré, Chatry and Moisio (2020), Asymmetric decentralisation: trends, challenges and policy implications, OECD Regional development Papers, https://doi.org/10.1787/0898887a-en.

[23] Autoridad Independiente de Responsabilidad Fiscal (2022), Plan de actuaciones de la AIReF.

[4] Bird, R. (ed.) (2007), Garcia-Milà, T. and T. McGuire (2007), “Fiscal Decentralisation in Spain: An Asymmetric Transition to Democracy”, Edward Elgar Publish.

[19] Comité de personas expertas (2022), Libro Blanco Sobre la Reforma Tributaria.

[24] European Commission (2022), Commission proposes new Euro 7 standards to reduce pollutant emissions from vehicles and improve air quality [press release], https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_22_6495.

[29] European Commission (2021), Green taxation and other economic instruments - Internalising environmental costs to make the polluter pay.

[27] European Commission (2017), “REFIT evaluation of Regulation (EC) No 166/2006 concerning the establishment of a European Pollutant Release and Transfer Register (E-PRTR)”, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52017SC0710&from=en.

[12] European Union (2012), Consolidated version of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

[14] Gobierno de Espana (2013), Law 27/2013, Of 27 December, Rationalization And Sustainability Of The Local Administration.

[20] Gobierno de Espana (2009), Ley Orgánica 3/2009, de 18 de diciembre, de modificación de la Ley Orgánica 8/1980, de 22 de septiembre, de Financiación de las Comunidades Autónomas.

[5] Gobierno de Espana (1985), Ley 7/1985, de 2 de abril, Reguladora de las Bases del Régimen Local.

[2] Gobierno de Espana (1978), The Spanish Constitution.

[22] IMF (2022), 2021 Article IV Consultation with Spain.

[9] Junta de Andalucia (2022), Decreto del Presidente 10/2022, de 25 de julio, sobre reestructuración de Consejerías.

[7] Junta de Andalucia (2020), New Trends in the Structuring of Andalusia, https://www.centrodeestudiosandaluces.es/.

[11] Junta de Andalucia (2010), Ley 5/2010, de 11 de junio, de autonomía local de Andalucía.

[10] Junta de Andalucia (2007), Ley Orgánica 2/2007, de 19 de marzo, de reforma del Estatuto de Autonomía para Andalucía.

[8] Junta de Andalucia (2007), Organic law 2/2007 dated 19 March 2007 on Reform of the Statute of Autonomy for Andalusia.

[30] Labandeira, X. (2022), Taxation and Ecological Transition during Climate and Energy Crises: the Main Conclusions of the 2022 Spanish White Book on Tax Reform, Real Instituto Elcano WP 09-2022, https://www.realinstitutoelcano.org/en/work-document/taxation-and-ecological-transition-during-climate-and-energy-crises/.

[21] Ministerio de Hacienda y Funcion Publica (2022), Autonomous Community Funding.

[1] OECD (2022), 2022 Synthesis Report World Observatory on Subnational Government Finance and Investment, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b80a8cdb-en.

[26] OECD (2022), Air pollution effects (indicator), https://doi.org/10.1787/573e3faf-en (accessed on 29 November 2022).

[18] OECD (2021), Interpretative Guide to Revenue Statistics.

[28] OECD (2020), Financing Water Supply, Sanitation and Flood Protection: Challenges in EU Member States and Policy Options, OECD Studies on Water, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/6893cdac-en.

[16] OECD-UCLG (2022), 2022 Report of the World Observatory on Subnational Government Finance and Investment - Country Profiles.

[17] OECD-UCLG (2022), 2022 Report of the World Observatory on Subnational Government Finance and Investment – Key Findings, https://doi.org/10.1787/b80a8cdb-en.

[15] OECD-UCLG (2019), Report of the World Observatory on Subnational Government Finance and Investment – Country Profiles, https://www.sng-wofi.org/country-profiles/Fiche%20SPAIN.pdf.

[25] Responsible Travel (2022), Tourist taxes map, https://www.responsibletravel.com/copy/tourist-taxes-map (accessed on 29 November 2022).

[13] The Congress of Local and Regional Authorities (2021), Monitoring of the application of the European Charter of Local Self-Government in Spain.

[6] The Congress of Local and Regional Authorities (2013), Local and regional democracy in Spain.

Notes

← 1. Although the Treaty uses the term of “competence”, this report uses the term “responsibility” to refer to a ”legal competence” and uses the term “tax competence”, in accordance with this project’s Detailed Project Description (DPD), in order to clearly distinguish between “legal competences” and “tax competences”.

← 2. The inter-regional clearing fund is a transfer from the central government to the autonomous communities and Provinces for investment expenditure, with the aim to correct economic imbalances between the autonomous communities and implement the principle of solidarity (art. 158).

← 3. A non-official English summary of these suggestions were recently published (Labandeira, 2022[30]).