This chapter offers a brief diagnosis of economic, social, environmental and institutional challenges in the Caribbean and suggests possible policy actions to address them. First, it reviews key economic issues related to the lack of competitiveness, trade deficits and the region’s high debt-to-GDP ratio, which in turn reduces its fiscal space and public investment. The following section evaluates the lag in social investment and the need to tackle poverty and inequality, youth unemployment, poor education, lack of social protection, better health and social care, ageing demographics and gender disparities. This chapter also describes the environmental vulnerability of the Caribbean, due to its geo-ecological characteristics, population distribution and economic activity, and analyses challenges related to climate change adaptation, water resources and solid waste management, energy transition and sustainable transportation. The institutional situation is also assessed by exploring the content of development plans and problems regarding access to grants and concessional resources because of the graduation of Small Island Developing States (SIDS). Both local and global actions play a role to overcome these challenges and ensure higher inclusive and sustainable economic growth.

Latin American Economic Outlook 2019

Chapter 6. Special feature: The Caribbean small states

Abstract

Introduction

This chapter draws attention to the main economic, social, environmental and institutional challenges faced by Caribbean countries, particularly the small states. These countries, known as the Caribbean small states (CSS), include Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Monserrat, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago.

Despite high heterogeneity across countries, CSS face many economic challenges. Long-standing low growth and lack of competitiveness are the primary structural challenges. This condition aggravates accumulation of current account deficits and unsustainable debt levels. Fiscal constraint has been affecting public investment in social areas. The labour market has been particularly inefficient, restricting the economic potential of the sub-region. Policy priorities should include industrial restructuring to improve inclusive growth performance through development of new activities and modernisation of infrastructure in key sectors.

CSS need to increase expenditure in social programmes to tackle poverty and inequality. Although the sub-region has dramatically reduced poverty in recent years, half of the population remains vulnerable to falling back into poverty. Also, CSS experience urban-rural gaps on housing stock and access to services. Empowerment of women, human capital development and education can significantly improve competitiveness and be a force for development. The sub-region must address youth unemployment, along with increased migration of highly skilled individuals, in order for countries to move towards a knowledge-based economy.

In the environmental sphere, the impact of natural disasters is the main challenge of the sub-region and public policy must provide coherent direction to face it. Key policy areas to be tackled are climate change adaptation, water resources, solid waste management, sustainable transportation and a transition towards sustainable energy. The external economic and environmental vulnerabilities of CSS are linked to their geo-ecological characteristics. Thus, the combination of climate change impact, population distribution on the coast and pressure on water resources makes it necessary to find synergies among stakeholders to overcome environmental damages.

Policy actions from the global community to invest and provide functional co-operation are fundamental to promote inclusive and sustainable development in this sub-region. Strengthening relationships and partnerships, beyond their level of income per capita, is therefore crucial. Most of these countries still face challenges in their access to finance and grants, while remaining vulnerable to external environmental and economic shocks. CSS should find mechanisms to implement the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and align them with national development plans. They should ensure institutions have multi-sectoral and cross-cutting mechanisms in place to implement the SDGs and reinforce evidence-based processes.

Economic challenges: Structural imbalances, and lack of competitiveness and productivity

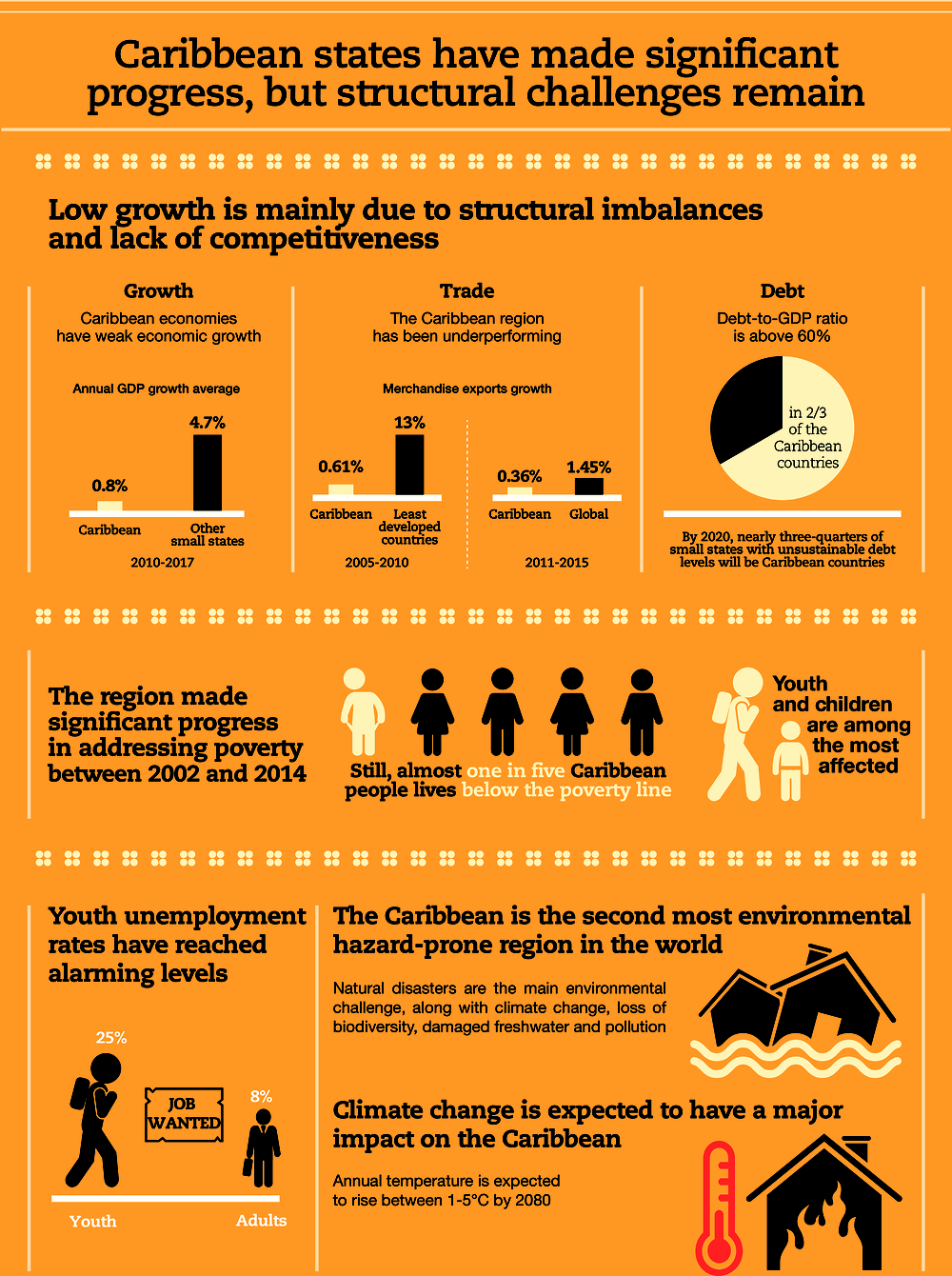

Although CSS have improved income per capita in the past decades, economic performance has remained poor. Since 2010 the countries have shown persistently weak economic growth. Annual gross domestic product (GDP) growth rates average only 0.8% compared with 4.7% in other small states. In 2016, CSS grew on average by 0.7% (ECLAC, 2018). Most CSS countries exhibit high levels of growth volatility, creating uncertainty, hindering economic growth and negatively affecting public finances (Beuermann and Schwartz, 2018).

Low growth in CSS has two key sources: structural imbalances and lack of competitiveness. These imbalances are mirrored in the region’s persistent current account deficits and high levels of public debt (Alleyne, 2018).

Trade, debt and fiscal situation

The Caribbean region (CARICOM) has been underperforming on trade – compared to other developing countries – before and after the 2008-10 recession. Between 2005-10, the sub-region’s merchandise exports grew by only 0.61% compared to exports of least developed countries, which grew by 13.07%. After the crisis, Caribbean countries’ merchandise exports grew annually by 0.36% on average, which was lower than global exports which grew at 1.45% annually. The sub-region is failing to maintain its share of global markets, both in services and goods. This trend has been reinforcing the accumulation of current account deficits, as foreign direct investment and official development assistance (ODA) inflows have also declined in recent years (ECLAC, 2018).

The sub-region faces various challenges to participate in more value-added chains, while continuing to have low levels of market diversification. Better logistics, infrastructure and skills are necessary to produce medium-to-high technology products and engage in wider trade.

Debt in Caribbean countries has improved modestly in recent years. Nevertheless, the state debt-to-GDP ratio in two-thirds of Caribbean Community countries is above 60%. Most CSS record unsustainable debt levels; by 2020, nearly three-quarters of small states with unsustainable debt levels will be Caribbean. In 2015, 4 of the 25 most highly indebted countries in the world (measured by gross general government debt levels relative to GDP) were in the Caribbean: Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Grenada and Jamaica. The sub-region’s total debt service payments represented, on average, over 20% of total government revenue in 2015.

The high cost of debt service has greatly reduced countries’ fiscal space and undermined their ability to fund development priorities. There are several main drivers behind the fiscal deficit in CSS. These include poor economic performance, insufficient fiscal restraint and high financing costs in capital markets. Equally important is the impact of climate change from frequent disasters that reduce both output and government revenue, and that demand high levels of expenditures (Rustomjee, 2017; IMF, 2016; IBRD/World Bank, 2016).

Most Caribbean economies still have space to increase tax revenues more effectively. In 2016, the average tax-to-GDP ratio in the Caribbean was 25.5%. All Caribbean countries had a tax-to-GDP ratio above the Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) average of 22.7%, but below the OECD average of 34.0%. Tax-to-GDP ratios varied widely between countries, ranging from 22.9% in Trinidad and Tobago to 32.2% in Barbados. More than half of tax revenues are collected from taxes on goods and services, which tend to be less redistributive. This is above the LAC and OECD average. The share of tax revenue collected from income and profits is 29.5% of total taxation, a figure above LAC (27.3%) and the OECD (34.1%). This share varies strongly in the Caribbean – from 0% in Bahamas to up to 49% in Trinidad and Tobago. On the other hand, social security contributions account for only 10% of total taxation, a figure below the 15.9% average in LAC and the OECD average of 25.8% (OECD et al., 2018).

Two additional challenges have arisen that add to the vulnerability of many Caribbean economies: greater de-risking by banks and renewed challenges to offshore financial centres. De-risking – in which banks tighten lending to countries at greater risk – leads to the loss of corresponding relations with international banks. De-risking strategies by many large global banks could cripple investment, remittance flows and economic growth in the sub-region. At the same time, Caribbean islands are working to comply with international financial standards, but face renewed challenges. Changing regulations in developed countries could place a significant burden on states with limited negotiating leverage and constitute offshore financial centres. Both challenges require urgent policy interventions to provide viable options for economic diversification.

Fiscal pressures in CSS countries have been affecting public investment in key areas. For example, public capital expenditures rose on average by only 1 percentage point to 5.7% between 2000-15. This scenario is further complicated by a substantial fall of foreign investment and ODA flows (ECLAC, 2018).

Weak institutions lie at the heart of fiscal mismanagement of Caribbean economies. Weak institutions result in deficient policy planning, poor budget design and low fiscal discipline (see Chapter 3; the institutional trap). The lack of medium-term fiscal policy frameworks has worsened the fiscal stance, as fiscal policy tends to be procyclical. Furthermore, lack of, or weak, debt management systems and rules have similarly aggravated the fiscal position in Caribbean economies (Beuermann and Schwartz, 2018).

To boost competitiveness, the region needs to improve in key policy areas such as education and skills, energy, infrastructure and entrepreneurship

The Caribbean economy will continue to exhibit low economic growth rates unless it becomes more competitive. Structural imbalances indicate both lack of export competitiveness and low productivity. The sub-region needs an industrial policy complemented by enabling key factors such as education and skills and sustainable energy. Equally important, trade facilitation should promote new exports and better access to financing. Another enabling factor is stronger infrastructure and support for entrepreneurship, especially for micro, small and medium enterprises. Skills-intensive, creative and technology-driven production of goods and services should drive structural transformation (ECLAC, 2018).

The labour market is significantly inefficient, restricting its economic potential. Some inefficiencies are related to the lack of skilled individuals and the disjuncture between the educational system and the labour market. Despite progress, there are still major deficiencies in education and training. These deficits include low school performance and low pass-through rate from secondary to tertiary education. The region also suffers from low enrolment in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM), particularly in engineering and science and technology. Several studies have addressed the mismatch between skills acquired and labour market needs, especially professional skills linked to specific technical demands, such as information and communication technologies. This highlights the need to align education and training with the requirements of a knowledge-based economy (ECLAC, 2018).

The high cost of energy is undermining the sub-region’s competitiveness and growth. Energy costs in the Caribbean are among the highest in the world (PPIAF, 2014, p. 7). This suggests that development of renewables could mean a great opportunity for the sub-region. Nevertheless, economies faced considerable difficulties in financing renewable energy projects that typically require high upfront financial capital. Innovative financing instruments, such as combining loans and grants in blended financing, along with public-private partnerships, are an option to address these constraints.

Accessibility and mobility of people and goods are key for enhancing competitiveness. The development of the sub-region’s air and maritime infrastructure and services is vital for the connectivity of the Caribbean. Many challenges persist in this area, as only 4 of 12 Caribbean economies had adequate port infrastructure (CDB, 2016). Over the next decade, the sub-region would require about USD 30 billion to modernise its power, transportation, telecommunications, water and wastewater sectors (ECLAC, 2014).

Social development: Overcoming the social vulnerability trap

Low economic performance in past years has been coupled with poor human development gains (Table 6.1).

Table 6.1. The Caribbean and selected regions and groupings: Changes in Human Development Index ranking 2010-15

|

Country |

Change in HDI rank |

Region or grouping |

Average annual HDI growth (percentage) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Antigua and Barbuda |

-7 |

Arab States |

0.45 |

|

Bahamas |

-6 |

Caribbean small states |

0.30 |

|

Barbados |

2 |

East Asia and the Pacific |

0.92 |

|

Belize |

-2 |

Europe and Central Asia |

0.63 |

|

Dominica |

-8 |

Latin America and the Caribbean |

0.58 |

|

Grenada |

-3 |

Least developed countries |

1.08 |

|

Guyana |

-2 |

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

0.33 |

|

Haiti |

-2 |

South Asia |

1.25 |

|

Jamaica |

-6 |

Sub-Saharan Africa |

1.04 |

|

Saint Kitts and Nevis |

2 |

World |

0.61 |

|

Saint Lucia |

-8 |

||

|

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines |

-6 |

||

|

Suriname |

1 |

||

|

Trinidad and Tobago |

-5 |

Source: UNDP (2018).

Evidence suggests the Caribbean has lagged in social investment in recent years, with debt servicing diverting resources from social development. In this regard, lack and inadequacy of resources have constrained social investment in such critical areas as education, sanitation, healthcare, housing, work programmes and skills development. Building sustainable development requires promoting inclusion, autonomy and empowerment, particularly for the most vulnerable.

The Caribbean sub-region needs to address several critical social challenges. These include tackling poverty and inequality; unemployment, especially among youth; access to inclusive and equitable education; inadequate social protection; access to quality health and social care; and preparation for an ageing population. Gender disparities remain primary obstacles to an inclusive and resilient society, which makes gender equality a central and cross-cutting issue (ECLAC, 2018).

Poverty and social inclusion

The Caribbean region made significant progress in addressing poverty between 2002 and 2014. Nevertheless, almost one in five Caribbean people lives under the poverty line. Children and youth are among the most affected (Table 6.2) (ECLAC, 2018).

Table 6.2. The Caribbean: Poverty rate by age group, various years

(in percentages)

|

Country |

0–14 |

15–24 |

25–44 |

45–64 |

65+ |

All persons |

Poverty line (USD per adult ale per year) |

Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Antigua and Barbuda |

24.6 |

21.6 |

14.0 |

15.3 |

15.2 |

18.4 |

2366 |

2005–2006 |

|

Bahamas* |

13.9 |

9.1 |

4.9 |

3.5 |

6.3 |

9.3 |

2863 |

2001 |

|

Belize |

50.0 |

43.0 |

35.0 |

31.0 |

34.0 |

41.3 |

1715 |

2009 |

|

Dominica |

38.7 |

29.1 |

27.2 |

21.2 |

23.0 |

28.8 |

2307 |

2008–2009 |

|

Grenada |

50.8 |

47.7 |

33.0 |

24.8 |

13.3 |

37.7 |

2164 |

2007–2008 |

|

Jamaica |

20.2 |

18.6 |

11.9 |

14.0 |

18.7 |

16.5 |

2009 |

|

|

Saint Kitts and Nevis |

31.3 |

28.0 |

17.6 |

10.9 |

10.6 |

21.8 |

2714 |

2007 |

|

Saint Lucia |

36.9 |

32.5 |

25.0 |

21.3 |

19.1 |

28.8 |

1905 |

2005–2006 |

|

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines |

38.1 |

36.1 |

28.0 |

21.7 |

18.8 |

30.2 |

246 |

2007–2008 |

|

Trinidad and Tobago |

23.0 |

22.1 |

15.6 |

11.5 |

6.7 |

16.7 |

2005 |

|

|

Average (simple) |

32.8 |

28.8 |

21.2 |

17.5 |

16.6 |

25.0 |

||

|

Average (population weighted) |

24.1 |

21.9 |

15.1 |

14.3 |

15.6 |

18.8 |

Note: Figures for the Bahamas correspond to the following age groups: 5–14, 15–19, 35–54, 55–64, and 65 and over.

Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), on the basis of F. Jones, “Ageing in the Caribbean and the human rights of older persons: twin imperatives for action”, Studies and Perspectives series-ECLAC Subregional Headquarters for the Caribbean, No. 45 (LC/L.4130; LC/CAR/L.481), Santiago, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), 2016, country poverty assessments and surveys of living conditions.

Several significant factors influence poverty and vulnerability in the sub-region. These include gender, regional disparities, levels of education, occupation and sector of employment, household size and composition, number of household members employed, and quality of housing. Female-headed households, for example, are more vulnerable to poverty. Quality of housing can protect families from natural disasters and ease access to public utilities, which in turn secures better sanitary and health conditions.

Inequality in the Caribbean varies widely, but on average is below LAC economies and considerably above levels in the OECD. Inequality measured by the Gini coefficient, for example, was below the LAC average of 47.8 in all Caribbean economies. However, it was considerably above the OECD average of 33.2. Inequality was highest in Suriname (43.8) and Bahamas (41.9), and the lowest in Barbados (32.2) (Beuermann and Schwartz, 2018).

Urban-rural gaps on housing stock and access to services are evident in the Caribbean. Additionally, decent work of household heads – employment with social benefits – is a significant variable in the incidence of poverty, along with higher education level.

Social programmes must be intensified. This includes active labour market policies, cash transfer programmes, food basket and medicines for those in need. However, poverty and inequality are also to a significant extent associated with structural heterogeneity and low-productivity sectors, which account for more than half of all jobs in some countries. Income is an important driver for addressing inequality, and across the sub-region there are significant disparities in this area (ECLAC, 2018).

Women’s empowerment and autonomy

Women’s potential can be reached only if they have physical, economic and decision-making autonomy. This means i) eliminating all forms of violence against women and girls; ii) accounting for and improving the gender distribution of unpaid domestic work and care responsibilities; iii) addressing inequity and disadvantages in the labour market and promoting entrepreneurship; iv) improving sexual and reproductive health services; and v) enhancing women’s participation and leadership at all political levels in the sub-region (ECLAC, 2018).

Addressing gender-based violence is a major challenge in the Caribbean. Taking action first requires access to data and indicators that can identify the extent of the problem. Violence directly affects the way women develop in their diverse roles in life – from finding a job to having a better education. Likewise, women and girls who are subjected to violence are more vulnerable to human trafficking and international organised crime. Actions must be taken to fight all forms of violence against women and girls.

Other policies that will help empower women are related to reducing school dropout and easing young mothers’ access to employment. Policies for childcare and parental leave could also encourage better distribution of domestic workloads and secure better job development for women.

Human capital development and education

Attaining sustainable development requires without a doubt improvement of human capital. Human capital development can improve Caribbean competitiveness. This will involve complementing social programmes with an improved education system. The new economy also demands enhancing capabilities in STEM.

In terms of education coverage, the main challenges remain at pre-primary and tertiary levels. The Caribbean has achieved universal primary education and near secondary education, with some exceptions. Yet Caribbean countries lag behind in terms of early childhood and tertiary education (Table 6.3). Recent economic challenges have triggered a step backward in access to tertiary education. Some challenges are related to fiscal setbacks, which have led to reduced subsidies for higher education. The pass-through rate to tertiary education in the Caribbean is about 15%, less than half the rate of developed countries (ECLAC, 2018).

Table 6.3. Caribbean community: Gross enrolment rates in education, average for 2008-14

(Percentages of the population in the respective age group)

|

Country |

Pre-primary age |

Primary school age |

Secondary school age |

Tertiary institution age |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Antigua and Barbuda |

89 |

98 |

105 |

23 |

|

Bahamas |

NA |

108 |

93 |

NA |

|

Barbados |

79 |

105 |

105 |

61 |

|

Belize |

49 |

118 |

86 |

26 |

|

Dominica |

99 |

118 |

97 |

NA |

|

Grenada |

99 |

103 |

108 |

53 |

|

Guyana |

66 |

75 |

101 |

13 |

|

Haiti |

92 |

92 |

78 |

13.9 |

|

Jamaica |

82 |

85 |

101 |

18 |

|

Saint Kitts and Nevis |

60 |

100 |

88 |

14 |

|

Saint Lucia |

78 |

105 |

103 |

NA |

|

Suriname |

96 |

113 |

76 |

NA |

|

Trinidad and Tobago |

83 |

106 |

86 |

12 |

Source: UNDP (2015).

Quality of education remains a challenge in the Caribbean. Only about 23% of students who entered the final Caribbean Secondary Education Certificate (CSEC) examinations in 2015 and 2016 took the exam. What is more, roughly only 65% of them achieved pass grades. Over the same period, CSEC pass rates in mathematics and most sciences declined. While the number of students passing the CSEC English-language exams increased slightly, only 15%-17% of all students succeeded in this component of the exam (Caribbean Examinations Council, 2015, 2016; ECLAC, 2018).

Students entering the education system have relatively high failure rates and lack of proficiency. These outcomes highlight the inefficiency of investment in the education system. Another concern is the shortage of teachers and lack of teacher readiness. These problems have been exacerbated by increased migration of qualified teachers at primary and secondary levels to North America, the United Kingdom and Europe (ECLAC, 2018).

Workforce mobility and employment issues

The contracting workforce, characterised by increasing job loss and limited job creation, has mostly affected women and youth in the Caribbean, making them more vulnerable (Kandil et al., 2014).

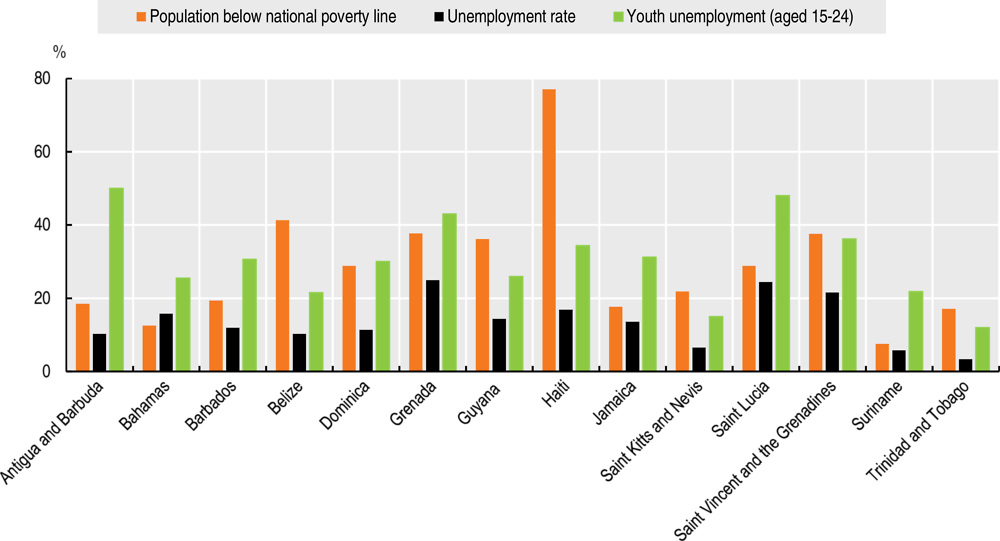

Youth unemployment rates, rising for over a decade, have reached alarming levels. On average, the rate was nearly 25% for the Caribbean – more than three times the adult unemployment rate of 8% (CDB, 2015). Also, gender gaps between young women and men experiencing unemployment are around 10%. According to some estimates, youth unemployment cost the Caribbean, on average, 1.5% of its annual GDP (CDB, 2015). Youth unemployment rates reach above 40% in Antigua and Barbuda, Grenada and Santa Lucia (Figure 6.1) (ECLAC, 2018).

Figure 6.1. Population below national poverty line, unemployment rate and youth unemployment in the Caribbean

Critical sectors in the Caribbean have lost talent. Professional workers, especially in critical sectors such as nursing, allied health, teaching and engineering professions, have more mobility. The departure of such professionals to more developed nations has resulted in a shortage of qualified labour. They leave the Caribbean for many reasons, including poor working conditions; remuneration and benefits that are not commensurate with qualifications; underuse of skills; and insufficient training and opportunities for career progression (ECLAC, 2018).

Social protection

There are inadequacies in the provision of social protection in the Caribbean owing to cyclical spending, insufficient targeting of poor and vulnerable groups, and gaps in social insurance. Although more resources are urgently needed, CSS should also aim to reduce imbalances in family allowance programmes and unemployment insurance, since only 40% to 50% of the regional workforce is in formal employment (Barrientos, 2004; Williams et al., 2013). Rapid demographic changes will also need to be considered in social protection programmes. These changes include the increasing number of older persons and high rates of migration among the young.

CSS has made progress on social security coverage, as all the English-speaking Caribbean countries have social security systems. All countries except Dominica, Grenada and Saint Lucia have non-contributory schemes. Some countries have also recently expanded the coverage and quality of pension schemes offered to people above 65 years of age. Others have provided security coverage to those who have no other pensions or are in particularly vulnerable situations. Despite this progress, non-contributory pension schemes are not well funded except in Trinidad and Tobago (ECLAC, 2018).

The Caribbean sub-region should give highest priority to both education and targeted social protection, including health. Other priorities consist of health challenges faced by the sub-region, especially on prevalence of non-communicable diseases related to unhealthy eating habits; physical inactivity; obesity; tobacco and alcohol use; and inadequate use of preventive health services.

Environmental vulnerability: Constraints and opportunities

The Caribbean is the second most environmental hazard-prone region in the world. Natural disasters are the main environmental challenges, along with concerns about climate change, loss of biodiversity, anthropogenic stressors on freshwater and land-based sources of pollution. The tourism industry, the main export sector of the economy, has also put pressure on natural ecosystems. Undoubtedly, a prosperous economy in the Caribbean and high quality of life depend on a healthy environment, which also provides the basis for all human activity.

The complex environmental challenges will require co-ordination of economic, social and environmental policies and coherent governance frameworks. Some of these challenges are related to climate change adaptation, water resources and solid waste management, energy transition and sustainable transportation.

Climate change adaptation

The geo-ecological characteristics of Caribbean small islands – generally small landmass and large marine area – combined with their population distribution and economic activity make them particularly vulnerable to external environmental and economic shocks. The concentration of people on the coast, for example, increases exposure of the population to the impact of natural phenomena, especially hurricanes.

Climate change is expected to have major impacts in the Caribbean. As one implication of climate change in CSS, mean annual temperatures are expected to rise between 1°C and 5°C by 2080. Other changes will manifest in more varied precipitation levels; while some areas will have more rain, others will have less. Sea levels are also expected to rise, leading to loss of coastline. Other environmental events may be related to the influence of El Niño Southern Oscillation, volcanic and tectonic crustal motions, and variations in the frequency or intensity of extreme weather events (ECLAC, 2011; IDB 2014; Mimura et al., 2007).

The Caribbean must overcome several issues before it can adapt effectively to climate change. These include weak institutional capacity, limited availability of data and information, lack of long-term environmental planning, inadequate policies and incoherent governance. Policy makers also need to leverage synergies between climate change adaptation and mitigation, and disaster risk management.

Water resources and solid waste management

Factors such as population growth and scarcity of water resources challenge the traditional approach to water management. Projections show that, because of climate change, the Caribbean region will become markedly drier. The proper management of water resources is of great importance in the conservation of marine ecosystems and groundwater. Even though most countries report over 95% access to water, potable water sustainability could be at risk owing to inefficient water use by core sectors of the economy; lack of wastewater management and long-term planning; and inefficient oversight of regulatory frameworks.

Key alternatives that might address water-resource challenges include: i) rainwater harvesting at the individual residence level; ii) use of desalination to provide potable water; iii) design and development of irrigation systems that optimise harvesting and use of ground, surface and rainfall resources; iv) recycling and reuse; and v) wastewater management (GWP, 2014).

Although solid waste management has not been a top environmental priority in the Caribbean, recent data have shown the significant impact of solid waste on the ocean. Evidence shows 85% of wastewater entering the Caribbean Sea remains untreated and 51.5% of households lack sewer connections (Cashman, 2014). Wastewater discharge has been a large contributor to the loss of over 80% of living coral in the Caribbean over the past 20 years (Villasol and Beltrán, 2004).

There are critical strategies for enhancing waste management operations in the Caribbean. These strategies include: i) implementation of fully integrated solid waste management systems; ii) promotion of national composting; iii) promotion of recycling; iv) review of fee structures for municipal solid waste management; v) strengthened institutional and regulatory frameworks for municipal solid waste management; and vi) promotion of public-private partnerships for solid waste management (Phillips and Thorne, 2013).

Energy transition

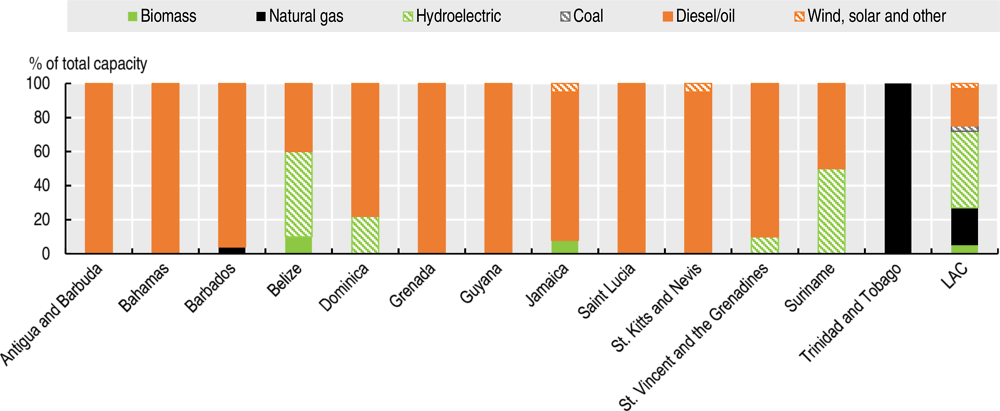

The demand for energy services in the Caribbean has increased considerably over the last decade, and the sub-region still relies heavily on fossil fuels. CSS has only four fuel-producing nations: Barbados, Belize, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago. However, large deposits of high-grade oil have recently been found off the coast of Guyana, while Grenada has found oil and gas in huge commercial quantities (ECLAC, 2018).

As there is still space for improvement, most countries aim to improve the role of renewables but enforcement of regulations has been called sluggish. Trinidad and Tobago has committed to increase the percentage of renewable energy sources in its overall energy supply to 10% by 2021; Grenada seeks to achieve a 20% contribution of renewables in all domestic energy usage by 2020. Nevertheless, the Caribbean is still yet to achieve energy diversification (McIntyre et al., 2016) (Figure 6.2).

Figure 6.2. Installed generation capacity, Caribbean and LAC, 2015 or latest

(Percentages of total capacity)

The Caribbean sub-region shows great potential for transitioning to a more sustainable energy matrix. Some issues that hinder the modernisation of energy systems include fiscal constraints, data gaps, lack of local capabilities, weak local markets, and incomplete or inadequate governance frameworks.

Sustainable transportation

Transportation is the main energy consumer in the Caribbean. Transportation accounts for 36% of the total primary energy consumed in the sub-region (IMF, 2016). This highlights the importance of increasing energy efficiency in the transportation sector as one of several strategies to improve sustainable energy consumption. However, efforts to transition to renewable energy in domestic transportation systems remain modest. A mixed policy option in this regard includes investments and systemic changes in areas such as urban planning, development of public transportation alternatives, establishment of goals for sectoral emissions, introduction of incentives to promote use of energy-efficient vehicles and adjustments to users’ behaviour.

Bearing in mind data gaps and a comprehensive understanding of the transportation sector, decision makers and planners should consider measures aligned with land use and transportation planning strategies. The adaptation or transformation of public transportation systems in the Caribbean could provide a great opportunity to address other problems such as employment challenges in some rural and urban areas (ECLAC, 2018).

Institutional challenges: Aligning development frameworks with global sustainable development agendas

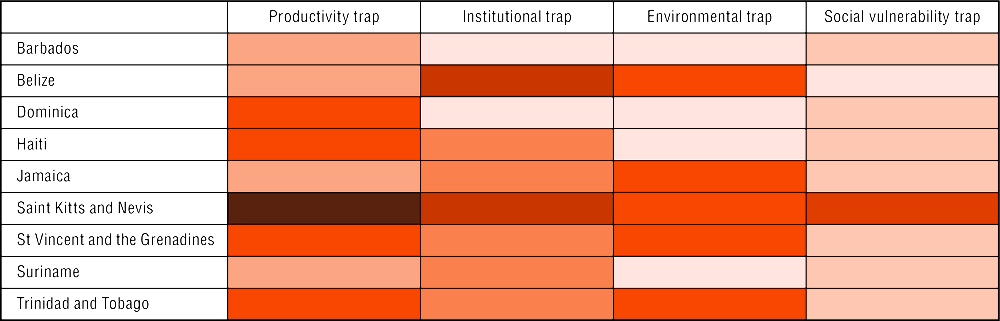

In the Caribbean, on average, countries identify institutional strengthening and productivity growth as their most pressing policy issues. Based on a review of development plans in the sub-region, strategic objectives were classified according to four major development traps described in Chapter 3: productivity, institutional, environmental and social vulnerability. In development planning tools, institutional strengthening and productivity growth are the most mentioned topics (Figure 6.3). Nine countries mentioned macro stability, growth and employment as key topics for productivity. Five countries mentioned reform and modernisation of the state as a strategic priority for institutional strengthening. Sub-regions have some differences on environmental issues. These have a higher presence in the Caribbean, due in part to the sub-region’s exposure to natural phenomena. On social vulnerability, six Caribbean countries stated that social and human development is a key priority.

Figure 6.3. Intensity of specific topics in development plans, Caribbean (nine countries)

Note: Each strategic objective of the national development plans for every country was classified according to a broad thematic area. Subsequently, strategic objectives were grouped according to their thematic link with the four development-in-transition traps. Next, a relative indicator was calculated by country, giving the maximum value to the country that covers all topics in every category in its strategic objectives. The colours indicate the intensity of the topics included in the strategic objectives. The darker the colour, the more frequently the related topic is mentioned as a priority in the development plan.

Source: ECLAC (2018), based on official information provided in development plans.

The main challenges of Caribbean countries in formulating and implementing development plans include financing, particularly inadequate access to concessional resources and grants; weak technical capacities, especially for production of disaggregated data; insufficient public awareness and political buy-in; and shortcomings in establishing effective institutional mechanisms to implement the plans.

Caribbean countries should also ensure institutional mechanisms to implement the SDGs, while plans should have multisectoral and cross-cutting structures. These mechanisms can benefit from involvement of all stakeholders, including civil society organisations, academia and the private sector. Countries that have not yet done so should initiate public awareness-raising and information campaigns in respect of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

More evidence is needed to understand the impacts of different forms of international co-operation on development opportunities to ensure that co-operation instruments and approaches meet countries’ needs. Over 2012-15, SIDS in the Caribbean received the largest share of concessional flows (44% of the total received by SIDS, or USD 8.4 billion). However, these flows were largely concentrated in Haiti and the Dominican Republic (64% of total funds received by Caribbean SIDS). SIDS should also attempt to find new ways to obtain resources for development such as green or blue bonds (OECD, 2018).

CSS should urge their multilateral and bilateral partners to continue and intensify co-operation with Caribbean regional institutions and member states to strengthen their capacity to produce and disseminate disaggregated data. Well-developed statistics are crucial to measure the effectiveness of programmes and policies (OECD, 2018).

Triangular co-operation is essential to achieve sustainable development in the Caribbean. Already, 66% of all triangular co-operation projects towards the SIDS were destined for the Caribbean. This type of co-operation can combine resources and expertise with mutual learning and policy dialogue (Chapter 5). There is scope to foster programmes that allow the exchange of experiences between regions through triangular co-operation (OECD, 2018).

Conclusions

Weak economic growth has been persistent in Caribbean small states with high levels of growth volatility. This results in uncertainty and a negative effect on public finances. Low economic growth can mainly be explained by structural imbalances and lack of competitiveness. Structural imbalances include trade, debt and fiscal stance. The Caribbean region has been underperforming on trade − compared to other developing countries − with low participation in value-added chains, and low levels of market diversification. Despite modest improvements in recent years, debt in most Caribbean countries is above 60% of GDP. Low tax revenues, high debt servicing and low fiscal space have affected public investment in key areas, further limiting a higher level of inclusive and sustainable growth. Structural imbalances also point to a competitiveness trap. Lack of competitiveness due to lags in education and skills, sustainable energy, infrastructure and entrepreneurship also hinders economic growth.

Social inclusion remains a challenge for Caribbean small states. Despite recent improvements, more than half of the region’s population remains vulnerable to poverty. In the Caribbean, a large percentage of the population still lives under the poverty line. Poverty and vulnerability are mainly influenced by gender and regional disparities, levels of education, occupation and quality of employment, size and composition of the household, number of household members employed and quality of housing.

Natural disasters are the main environmental challenges in the Caribbean, along with concerns about climate change, loss of biodiversity, anthropogenic stressors on freshwater and land-based sources of pollution. The geo-ecological characteristics of Caribbean small islands and the concentration of the population increase exposure to natural phenomena, especially hurricanes. As a result, Caribbean small islands will likely experience some of the biggest impacts of climate change.

To increase sustainable and inclusive growth, as well as confront environmental challenges, Caribbean small states must improve domestic capacities; the global community plays an important role in that regard. CSS should formulate and implement development plans that include increasing finances, strengthening technical capacities, increasing public awareness and political buy-in; and establishing effective institutional mechanisms to implement the plans. More evidence is needed to understand the impact of different forms of international co-operation on development opportunities in Caribbean countries.

References

Alleyne, D. (2018), “Macroeconomic policies to promote sustainable growth”, Social and Economic Studies, forthcoming.

Barrientos, A. (2004), Social Protection and Poverty Reduction in the Caribbean: Draft Regional Report, Caribbean Development Bank/Department for International Development/Delegation of the European Union to Barbados, the Eastern Caribbean States, the OECS and CARICOM/CARIFORUM [online], http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.595.8703&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

Beuermann, D.W. and M.J. Schwartz (eds.) (2018), Nurturing Institutions for a Resilient Caribbean, Inter-American Development Bank, Washington, DC.

Caribbean Examinations Council (CXC) (2016), CXC Annual Report 2016, St. Michael, Barbados.

Caribbean Examinations Council (CXC) (2015), CXC Annual Report 2015, St. Michael, Barbados.

Cashman, A. (2014), Water Security and Services in the Caribbean, Mdpi Water, St Michael, Barbados.

CDB (2016), Transforming the Caribbean Port Services Industry: Towards the Efficiency Frontier, Caribbean Development Bank, St. Michael, Barbados.

CDB (2015), Youth are the Future: The Imperative of Youth Employment for Sustainable Development in the Caribbean, Caribbean Development Bank, St. Michael, Barbados.

ECLAC (2018), Caribbean Outlook, 2018 (LC/SES.37/14/Rev. 1), Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, Santiago.

ECLAC (2014), Regional Integration: Towards an Inclusive Value Chain Strategy (LC/G.2594 SES.35/11), Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, Santiago.

ECLAC (2011), Caribbean Development Report Volume III: The Economics of Climate Change in the Caribbean, ECLAC Subregional Headquarters for the Caribbean, Port of Spain, December.

GWP (2014), “Integrated water resources management in the Caribbean: The challenges facing Small Island Developing States”, Technical Focus Paper, Global Water Partnership, Stockholm, https://www.gwp.org/globalassets/global/toolbox/publications/technical-focus-papers/04-caribbean_tfp_2014.pdf.

IBRD/World Bank (2016), World Bank Group Engagement with Small States: Taking Stock, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and World Bank, Washington, DC.

IDB (2014), Climate Change at the IDB: Building Resilience and Reducing Emissions, Inter-American Development Bank, Washington, DC [online] https://publications.iadb.org/en/publication/16884/climate-change-idb-building-resilience-and-reducing-emissions.

IMF (2016), “Small states’ resilience to natural disasters and climate change: Role for the IMF”, IMF Policy Paper, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

Jones, F. (2016), “Ageing in the Caribbean and the human rights of older persons: twin imperatives for action”, Studies and Perspectives series-ECLAC Subregional Headquarters for the Caribbean, No. 45, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, Santiago, Chile [online] https://repositorio.cepal.org/handle/11362/39854.

Kandil, M. et al. (2014), “Labor market issues in the Caribbean: Scope to mobilize employment growth”, IMF Working Papers, No. WP/14/115, International Monetary Fund (IMF).

McIntyre, A. et al. (2016), “Caribbean energy: Macro-related challenges”, IMF Working Paper, No. WP/16/53, International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Mimura, N. et al. (2007), Small Islands. Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, M.L. Parry, O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van del Linden and C.E. Hanson, (Eds.), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 687-716

OECD (2018), Making Development Co-operation Work for Small Island Developing States, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264287648-en.

OECD et al. (2018), Revenue Statistics in Latin America and the Caribbean 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/rev_lat_car-2018-en-fr.

Phillips, W. and E. Thorne (2013), “Municipal solid waste management in the Caribbean: A benefit-cost analysis”, Studies and Perspectives Series - ECLAC Subregional Headquarters for the Caribbean, No. 22 (LC/L.0210; LC/CAR/L.349), Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), Santiago, Chile.

PPIAF (2014), Caribbean Infrastructure PPP Roadmap, Public-Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility, Washington, DC.

Rustomjee, C. (2017), “Pathways through the silent crisis: Innovations to resolve unsustainable Caribbean public debt”, CIGI Papers, No. 125, April, Centre for International Governance Innovation, Waterloo, Canada.

UNDP (2018), “Trends in the Human Development Index, 1990–2017”, in Human Development Reports, United Nations Development Programme, New York, http://hdr.undp.org/en/composite/trends.

UNDP (2016), Caribbean Human Development Report – Multidimensional Progress: Human Resilience beyond Income, United Nations Development, Programme, New York, http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/undp_bb_chdr_2016.pdf.

UNDP (2015), Human Development Report 2015: Work for Human Development, United Nations Development Programme, New York, http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/2015_human_development_report.pdf.

Villasol, A. and J. Beltrán (2004), “Global international waters assessment: Caribbean Islands”, Global Regional Assessment, No. 4, University of Kalmar, Sweden, and United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi.

Williams, A. et al. (2013), “Tailoring social protection to Small Island Developing States: Lessons learned from the Caribbean”, Discussion Paper, No. 1306, World Bank.