This chapter presents ten elements of credible corporate transition plans, building on the review of existing approaches to transition plans in Chapter 2 and the challenges encountered by market actors that are identified in Chapter 3. Most existing transition plan approaches cover the following elements: net-zero and interim targets; performance metrics and Key Performance Indicators (KPIs); carbon credits and offsets; actions towards implementation; internal coherence with the company’s business plan; governance and accountability; and transparency and verification. Other elements are largely underdeveloped in existing approaches but are elaborated in this Guidance. They include: consideration of non-climate-related sustainability impacts; integration of corporate transition plans with other sustainable finance tools and tools for Responsible Business Conduct (RBC); just transition aspects; information on prevention of carbon-intensive lock-in; and, where appropriate, tailored approaches for micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) and certain companies in emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs).

OECD Guidance on Transition Finance

4. Elements of credible corporate climate transition plans

Abstract

4.1. Transition plans as part of the broader sustainable finance toolbox

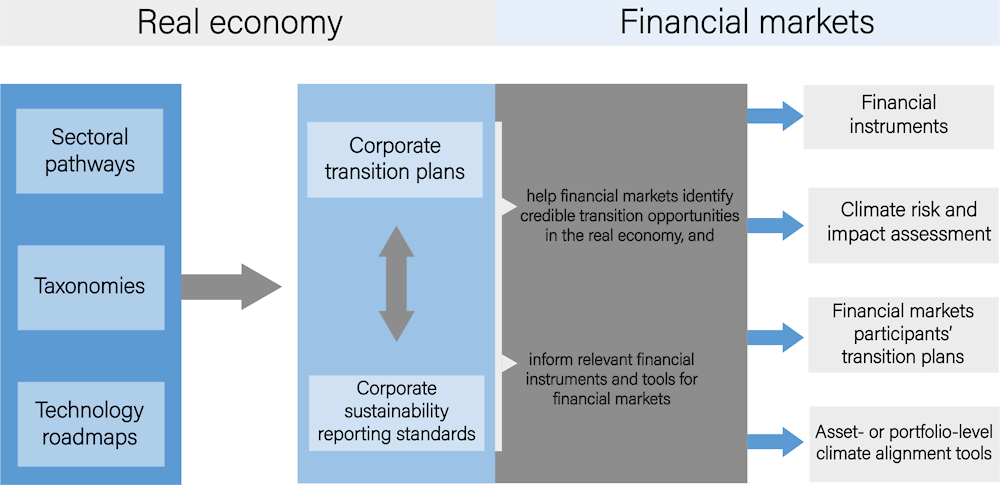

An important starting point for the Guidance is the recognition of existing tools and frameworks, both in transition and sustainable finance. Tools like taxonomies, sectoral pathways, technology roadmaps, and reporting standards are all relevant to and can increase the credibility and comparability of corporate transition plans. Conversely, credible corporate transition plans can minimise the risk of greenwashing in transition finance approaches and transactions by helping to ensure that there is a credible whole-of-entity transition strategy in place, supporting the issuance of relevant financial instruments. In this sense, the Guidance builds on and connects different tools and frameworks, including existing transition and sustainable finance approaches, and helps promote and ensure credible corporate transition plans to minimise the risk of greenwashing in transition finance.

The most relevant tools are shown in Figure 4.1 and discussed further below. Figure 4.1 does not aim to present an exhaustive list of all tools and frameworks that exist in sustainable finance. Instead, it focuses on those on the real economy side that can help increase the credibility of corporate transition plans, and the ones on the financial markets side that can most benefit from such plans.1 They include (i) sectoral pathways; (ii) taxonomies; (iii) technology roadmaps; and (iv) corporate sustainability reporting standards. Sectoral pathways, taxonomies, and technology roadmaps are important inputs for the development of credible corporate transition plans. Corporate sustainability reporting standards form an integral part of corporate transition plans, as they deal with key elements of disclosure that also form part of credible corporate transition plans: All credible corporate transition plans will include elements that are also required, with varying levels of stringency or prescriptiveness, by existing sustainability reporting standards (for example, performance metrics and KPIs). Conversely, only a sub-set of sustainability reporting standards, such as the one being developed by the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG) at EU-level, requires the development of corporate transition plans. Corporate transition plans and the related corporate sustainability disclosure, in turn, are crucial inputs for financial market participants, as they make the link between the real economy and financial markets that is needed to help market actors identify credible transition investments, and develop relevant financial instruments, climate alignment tools, etc.

Figure 4.1. Overview of relevant sustainable and transition finance tools and frameworks

Specifically, they can inform financial market participants and financial markets in the following ways:

The adoption of credible transition plans by corporates can help enable the financing of decarbonisation actions by providing financial market participants with confidence in the corporate’s commitment to decarbonise. Hence, the corporate will be able to issue sustainable debt or raise equity, in the form of sustainability-linked bonds or loans, transition bonds, green bonds or loans, or other instruments, backed by a credible whole-of-entity strategy.

Credible corporate transition plans facilitate the assessment by financial market participants of climate-related financial risk stemming from proposed actions, or inaction, of corporates who may be exposed to transition risk. It also allows financial market participants to assess the climate-related investment opportunities available for different corporates.

Elements of credible corporate transition plans can be useful building blocks for measuring asset- or portfolio-level climate alignment through dedicated tools and methodologies. This is further explored, for instance, in (Noels and Jachnik, forthcoming[1]). The Net-Zero Asset Owner Alliance’s Target Setting Protocol also recognises this connection when stating that portfolio alignment will be achieved through a mixture of capital reallocation, best-in-class, and investing in climate solutions, alongside, for example, the use of sectoral pathways (UNEP, 2022[2]).

4.1.1. Sectoral pathways

Sectoral pathways offer sector-specific trajectories for reducing emissions and consider the specific technological advances and hurdles of different sectors. Sector-specific decarbonisation pathways are often based on underlying scenarios, such as the International Energy Agency (IEA) or One Earth Climate Model scenarios (see, for example, (Teske et al., 2020[3]), (TPI, 2022[4])). For instance, the Net Zero Asset Owner Alliance have developed sectoral pathways to support their 5-year intermediate targets on the pathways towards 1.5°C (Teske et al., 2020[3]).

Sector pathways are particularly important for hard-to-abate sectors where net-zero options are not always immediately feasible or available. They offer a reference point for environmental ambition and credibility. For example, Germany implemented annual emission reduction targets for key sectors, including energy, transport, industry, and agriculture, in its proposed pathway to net-zero emissions (Jeudy-Hugo, Lo Re and Falduto, 2021[5]). However, broad sectoral scope and emissions coverage for economy-wide sectoral pathways is still lacking, with several countries having unclear sectoral scopes for emissions (Jeudy-Hugo, Lo Re and Falduto, 2021[5]).

4.1.2. Technology roadmaps

Moreover, sectoral pathways can inform sectoral technology roadmaps at national, regional, or global level. They are roadmaps developed for specific sectors, which provide an indication of which technologies could be used to achieve emission reduction targets along a decarbonisation pathway for the sector in question. For instance, Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry has been developing comprehensive technological roadmaps, describing transition and innovative technologies that contribute to net zero on a pathway to 2050 for a number of hard-to-abate sectors, such as chemicals and steel. These roadmaps are publicly available and cover seven industries to-date (METI, 2021[6]).

4.1.3. Sustainable, green and transition taxonomies

Sustainable, green and transition taxonomies are definitions for sustainable finance that aim to be comprehensive classification systems (OECD, 2020[7]). They can either be primarily focused on defining “green” economic activities which are aligned with a temperature or other environmental goals or focused on transition activities which improve upon what is currently in place, or a combination of both. With respect to transition activities, different approaches have been employed to strengthen their environmental credibility within taxonomies. The transition feature in taxonomies often refers to two types of activities: (i) activities that are currently transitioning towards a net-zero status, with the ultimate objective of being green, and (ii) activities that are enabling (activities in) the economy to transition towards sustainability (NGFS, 2022[8]). For example, the discussion paper of the Singaporean Green Finance Industry Task Force on their taxonomy includes the condition that no green alternative can exist for the activity to be considered a transition activity (MAS, 2022[9]). Other approaches are less stringent; for example, the Malaysian taxonomy requires companies to demonstrate commitment and willingness to transition to sustainable operations (Bank Negara Malaysia, 2021[10]). Lastly, under the EU Taxonomy, a number of conditions should, according to the legal framework, apply to transition activities, namely: (i) there can be no technologically and economically feasible low-carbon alternative; (ii) the activity has to have emission levels that correspond to the best performance in the sector; (iii) it cannot hamper the development and deployment of low-carbon alternatives; and (iv) it cannot lead to lock-in of carbon-intensive assets (EU, 2020[11]).

Both green and transition taxonomies can be used by financial market participants to assess the environmental credibility of corporates’ planned capital expenditures, expenditures on research, development and innovation, as well as, to a lesser extent, operating expenditures as part of their transition strategies. This can also help them compare levels of ambition within and between economic regions and sectors. Similarly, taxonomies can be used by corporates to set internal targets, support capital and business planning towards their net-zero targets and provide confidence to financial market participants. These measures are important because they offer insight into whether corporates are deploying sufficient financial means to achieve the climate objectives set out in their disclosure and related transition plans.

One emerging issue in this area is the lack of international comparability of climate alignment approaches, due to the diversity of approaches and underlying methodologies that are being used by different jurisdictions. This was acknowledged by the G20 Sustainable Finance Working Group in 2021 as part of their high-level principles for the future development of alignment approaches. Moreover, taxonomy developers in EMDEs face the challenge of aligning with the principles or criteria of existing taxonomies while also needing to align with local regulations that reflect their own development paths and growth models, which are often at earlier stages of transition (NGFS, 2022[8]). Work is ongoing at international level to enhance coordination and comparability across national and regional taxonomies, such as through the IPSF’s Common Ground Taxonomy (European Commission, 2022[12]) or the joint IMF-World Bank-OECD-BIS operationalisation guidance of the high-level principles for sustainable finance alignment approaches (IMF-World Bank-OECD-BIS, forthcoming[13]). These international coordination efforts can strengthen the usefulness of taxonomies as part of corporate transition planning by increasing their comparability at global level.

4.1.4. Corporate sustainability reporting standards

Sustainability disclosure or reporting standards can deliver a global baseline of sustainability-related information for financial markets on companies’ sustainability-related risks and opportunities (IFRS, 2021[14]). Reporting standards on sustainability are currently being developed by the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB), in order to provide financial market participants with information about companies’ sustainability-related risks and opportunities. These reporting standards aim to offer an overall framework for companies to disclose their environmental information, relevant for financial market participants. Other sustainability-related frameworks have been developed, such as the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board’s (SASB) framework, which offers both a sector-neutral and sector-specific guidance, aiming to set standards for sustainability accounting (SASB, 2020[15]). Beyond these global initiatives, there are national-level reporting standards being developed, such as through the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) (European Commission, n.d.[16]) or the proposed climate-related disclosure by the United States Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) (U.S. SEC, 2022[17]). These frameworks outline how companies should report on sustainability and environmental issues. Companies can utilise these frameworks to offer standardised sustainability reporting within their transition plans, maximising comparability.

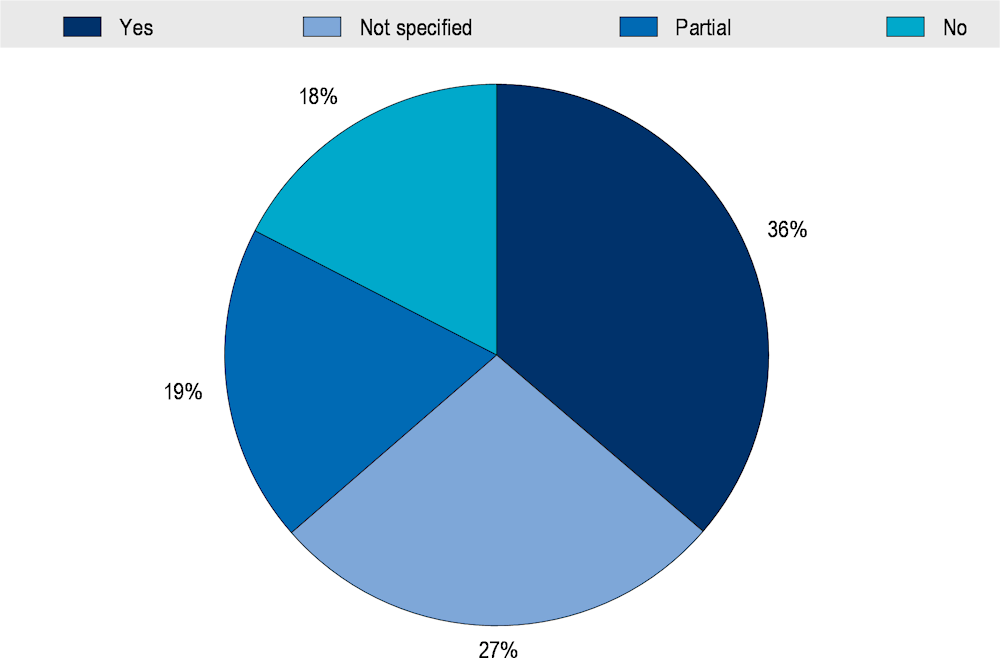

In this context, company-level metrics and targets are essential to assess and compare climate-related risks and opportunities, as well as manage company performance against targets (TCFD, 2021[18]). To measure and track decarbonisation performance, either absolute greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions or GHG emission intensity can be considered. Moreover, within this measurement, consensus seems to be moving towards reporting against all GHG emission scopes to the extent possible, in order to offer a fair assessment of a corporate’s performance, and despite the existing challenges associated with reporting scope 3 emissions (see, for example, (SBTi, 2021[19]), (IFRS, 2022[20]), (Noels and Jachnik, forthcoming[1])). However, companies’ practices regarding reporting on scope 3 emissions and including them in emission reduction targets still vary significantly. For example, only around 36% of the emission reduction targets of largest publicly traded companies analysed by the Net Zero Tracker cover scope 3 emissions (see Figure 4.2 below) (Net Zero Tracker, 2022[21]). Similarly, recent analysis of climate-related strategies and targets of 25 multinational companies shows that while scope 3 emissions accounted on average for 87% of total emissions of the assessed companies, only 8 of them disclosed a moderate level of detail on their plans to address them (New Climate Institute and Carbon Market Watch, 2022[22]).

Figure 4.2. Coverage of scope 3 emissions in corporate emission reduction targets

Note: This is based on Net Zero Tracker’s data collection of 2000 large publicly traded companies’ emission reduction targets (considering the whole spectrum of targets, i.e., net-zero, zero-carbon, climate-neutral, etc.). Out of the 2000 companies analysed, 1041 have a target in place. This chart illustrates the coverage of scope 3 emissions of targets in place. Their data collection is based on companies’ claims.

Source: Authors based on (Net Zero Tracker, 2022[21]).

Naturally, for other environmental objectives different metrics will be more appropriate. Setting industry standards for the use of metrics and calculation methodologies for different environmental objectives could enable greater clarity for investors and comparability within sectors to assess environmental ambition.

4.2. Ten elements to ensure credibility

As set out in Chapter 2 and Annex B, several initiatives by industry, NGOs and think tanks provide principles, analysis, guidance and frameworks on what constitutes a credible corporate transition plan, such as (ACT, 2019[23]; CA100+, 2021[24]; CBI, 2021[1]; CDP, 2021[2]; CPI, 2022[3]; GFANZ, 2021[25]; ICMA, 2020[26]; IFRS, 2022[21]; IGCC, 2022[27]; SBTi, 2021[28]; TCFD, 2021[37]). Based on literature review of such initiatives, insights from the dedicated OECD Industry Survey on Transition Finance and additional consultations and interviews with public and private sector experts, this section provides guidance on the elements of corporate transition plans that are crucial for both corporates and financial market participants to drive meaningful progress towards net zero in a transparent and credible manner.

Transition plans are useful for corporates to explain their goals, commitments, actions and progress towards climate action and sustainability, as well as how they maintain financial performance and competitiveness during their transition. Credible corporate transition plans also allow financial market participants to have a sufficiently robust basis to make informed investment decisions, thereby reducing the risk of greenwashing, and to better manage their own transition risks while harnessing transition opportunities. It is worth noting that, while this Guidance focuses on non-financial corporates, financial market participants are also increasingly called upon to design and implement their own transition plans towards achieving their net-zero commitments (GFANZ, 2021[23]; IGCC, 2022[24]). Financial market participants’ transition plans necessarily relate to corporate transition plans and the credibility of the former will hinge on the credibility of the latter.

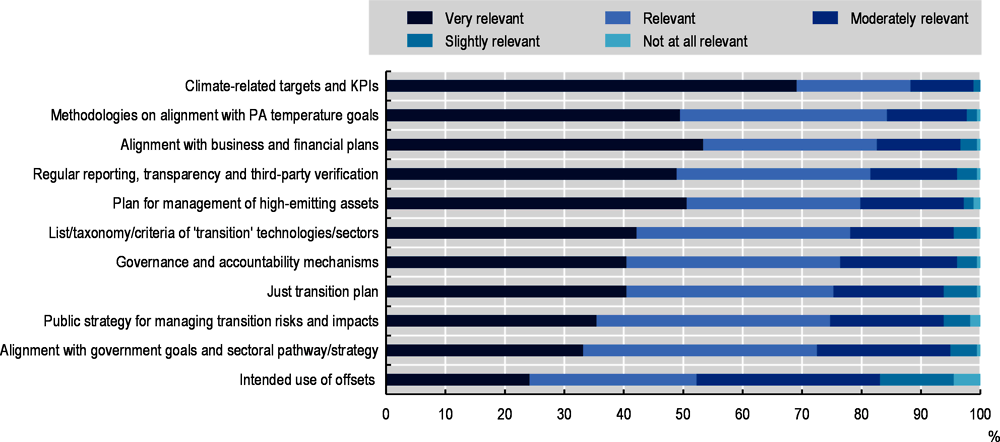

The list of ten elements of credible corporate transition plans presented below builds on emerging practices and approaches for transition finance and transition plans and identifies further elements where additional information and transparency is warranted. It draws on and complements different elements presented by existing initiatives, as listed above, and laid out in Chapter 2 (notably, CPI, CBI, TCFD, ISSB, CDP, GFANZ, ICMA, CA100+, and SBTi). The degree of relevance of these elements has been tested through the OECD Industry Survey on Transition Finance, whose results show that on average 77% of respondents considered the proposed elements of credible transition plans as either relevant or very relevant (see Figure 4.3 below). This approach can also act as an umbrella for existing tools and frameworks relevant to transition finance (such as taxonomies, roadmaps, pathways, and sustainability reporting standards), as it can connect these elements in one clear transition plan, accessible to financial market participants for making investment decisions. By identifying elements where additional transparency is warranted, compared with existing approaches, the Guidance can also inform corporates seeking to establish credible transition plans, and policymakers seeking to develop or strengthen existing transition finance approaches and approaches to corporate transition plans.

Figure 4.3. Relevance of key elements of credible transition plans

Note: The number of respondents for this survey question was 178.

Source: 2022 OECD Industry Survey on Transition Finance.

4.2.1. Element 1: Setting temperature goals, net-zero, and interim targets

To be credible, a corporate transition plan will clearly set out and explain its net-zero target and associated interim targets. These targets will be in line with the global temperature goal of the Paris Agreement. It will specify how the corporate aims to concretely achieve those targets through tangible decarbonisation actions (see further guidance as part of the subsequent elements presented in this section). Targets will clearly specify the underlying assumptions and methodologies, and in particular how they relate to the selected global temperature goal (see also Box 3.1 in Chapter 3 for further information). Explaining how climate scenario analysis was used to set targets (including underlying assumptions and limitations), whenever feasible, also brings credibility to corporate transition plans (TCFD, 2021[18]).2

Setting net-zero and interim targets based on science, meaning, in a manner consistent with the IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C, to ensure no or limited overshoot of 1.5°C globally above pre‑industrial levels, is crucial to ensuring credibility. Practically, this requires global net anthropogenic CO2 emissions to decline by about 45% from 2010 levels by 2030, reaching net zero around 2050, including similar deep reductions for non-CO2 GHG emissions (IPCC, 2018[25]).

The exact target dates for achieving net zero may vary by sector and jurisdiction, as achieving net zero by 2050 globally can entail different levels of effort by different sectors and industries, and commitments by national jurisdictions vary. For example, according to the IEA, emissions from electricity should reach net zero globally by 2040, while heavy industry would not fully reach net-zero even by 2050, with “more than 90%” of production across heavy industry being “low-emission” at that point (IEA, 2021[26]). Similarly, while some countries have adopted net-zero targets that are more ambitious than 2050, such as the Swedish target of 2045 (Government Offices of Sweden, 2022[27]) or Finland’s target of 2035 (OECD, 2021[28]), others have adopted targets for after 2050, such as China’s 2060 or India’s 2070 targets (Climate Action Tracker, 2022[29]). The IEA estimates that the pledges announced at the COP26 Climate Change Conference, together with the announcements made before then, if implemented in full, may be sufficient to hold the rise in global temperatures to 1.8°C by 2100 (IEA, 2021[30]). As such, these targets may collectively be consistent with limiting the increase in global temperatures to below 2°C.3 In order to account for this variety and allow for proportionality, companies could use an IPCC reference scenario that is consistent with limiting warming to below 2°C, if they cannot, in their assessment, use 1.5°C as their benchmark. The lack of a national net-zero target, or the setting of a target with a later date (i.e. after 2050), or the lack of sufficient enabling policies to incentivise company decarbonisation may be factors that could prevent some of the companies operating in those jurisdictions from being able to comply with a 1.5°C trajectory. At a global level, complying with a 2°C trajectory would require reaching net zero by around 2070 (IPCC, 2022[31]). It is important for companies that choose a below 2°C scenario to provide a reasoned and detailed justification to explain why being consistent with a 1.5°C scenario is not possible for them, to avoid greenwashing and allow investors to evaluate the level of environmental ambition considering all the relevant evidence.

To allow investors to situate the company’s activities within the relevant national policy context, the plan will include an explanation as to how the plan’s targets compare to the relevant NDC and national net-zero target, if any. Where the ambition and stringency of the relevant NDC and national net-zero target is inconsistent with the plan’s net-zero target and associated temperature goal, the plan will recognise this and provide an explanation of how the risks associated with this discrepancy are addressed.

Importantly, according to the IPCC, pathways limiting warming to 1.5°C and pathways limiting warming to 2°C both project a peak in global GHG emissions by 2025 at the latest and “assume immediate action” (IPCC, 2022[31]). To avoid carbon-intensive lock-in, credible near-term interim targets will reflect this peak and need for immediate action, irrespective of which of the two pathways is chosen. This has been reaffirmed at the 2022 OECD Ministerial Council Meeting, where Ministers and Representatives of OECD Members and non-Members stated that they “are committed to developing and implementing ambitious climate actions aimed at achieving net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, including through deep emissions reductions in this critical decade to keep a limit of 1.5°C temperature increase within reach” (OECD, 2022[32]).

More generally, any robust long-term transition goal will be accompanied by interim (e.g., 3/5-year) quantifiable, detailed and time-bound targets, including and explanation of the methodologies and assumptions used to derive them (Jeudy-Hugo, Lo Re and Falduto, 2021[5]). Given the need to reduce emissions urgently in this decade and to avoid lock-in, it will be important for transition plans to avoid back-loading important investment decisions that are necessary for the company’s decarbonisation strategy (IPCC, 2022[31]). Instead, the focus must be on emission reductions in this decade.

4.2.2. Element 2: Using sectoral pathways, technology roadmaps, and taxonomies

To support net-zero and interim targets, a credible corporate transition plan will be based on available sectoral pathways and technological roadmaps. The former can ensure that there is a clear emissions trajectory the company is following, in line with the selected target. The latter provides more concrete information on how the company intends to achieve these targets by setting out, at a high level, the main technologies that will be used to achieve those targets.

A credible corporate transition plan will include an explanation as to how the plan’s targets compare to relevant national-level frameworks, such as sector-specific transition pathways and roadmaps, where these are available. This explanation will allow investors to situate the company’s activities within the relevant national policy context. In cases where the ambition and stringency of national-level, sector-specific pathways and roadmaps is inconsistent with the plan’s net-zero target and associated temperature goal, the plan will recognise this and provide an explanation of how the risks associated with this discrepancy are addressed.

Importantly, a credible corporate transition plan will clarify how and for which technologies future operating and capital expenditures (including research, development and innovation expenditures) will be used, in order to achieve targets. Where available and relevant, this technology selection could be based on sustainable, green, or transition taxonomies and classification systems. In this context, a credible transition plan will also specify the mechanisms to be put in place to prevent carbon-intensive lock-in, if proposed investments in the plan present such a risk, notably investments relating to fossil fuel assets and infrastructure (see Box 4.1). To help clarify alignment with a pathway compliant with the temperature goal of the Paris Agreement, mechanisms to prevent lock-in in transition plans will explicitly identify possible assets and infrastructures at risk and the implementation of safeguards to minimise this risk. This can include futureproofing of assets, the use of sunset clauses and gradually more stringent emissions criteria to bring the emissions of relevant assets in line with net zero, as well as investment in R&D&I and plans for early retirement, where necessary.

Box 4.1. Selecting technologies for decarbonisation

To reach net-zero targets, companies need to have (and provide) clarity on which economic activities and specific technologies can put them on the right path towards those targets and avoid future lock-in into carbon-intensive assets. Which technologies can fulfil these functions will depend on the sector as well as the socio-political and economic context, within which the corporate operates. The acceptability of different technologies is not only based on technological and economic feasibility but can be impacted by socio-political circumstances.

Technology selection can be guided by sectoral technology roadmaps (see, for example the IEA Iron and Steel Technology Roadmap, (IEA, 2020[33])) and ideally be complemented through more detailed criteria that may be contained in relevant taxonomies and classification systems. To be credible, transition plans need to detail the set of actions and activities planned to achieve targets, including actions to decarbonise ongoing activities, develop or deploy low-emission technologies, diversify, adapt, or adjust activities and product mixes, phase out activities that cannot be brought in line with net-zero emissions goals, as well as actions to address emissions of supply chain both up- and downstream of the business.

In the area of climate change mitigation, when it comes to activities included in green taxonomies, relevant activities are frequently categorised into ‘low-carbon activities’ (e.g., electricity generation from renewables) and “enabling activities” (e.g., manufacture of wind turbines) (see, for example, (EU, 2020[11]), (National Treasury, Republic of South Africa, 2022[34]), (ASEAN, 2021[35]), (CBI, 2021[36])), though in some cases they cover only ‘low-carbon activities’ (European Commission, 2022[37]). Enabling activities are often considered on equal footing with low-carbon activities in terms of their ability to contribute to global net-zero targets.

Actions like renewable energy procurement, energy efficiency, and value-chain decarbonisation are suitable for almost all companies. Other actions will be sector-specific: for example, using electric and other zero-emission vehicles are actions suitable for transport sector companies, such as logistics firms, but likely less relevant for other industries. Some planned actions will reflect assumptions on the availability and cost of technologies in coming years. For example, some sectors rely on low-emission technologies (green hydrogen, carbon capture, utilisation and storage) that are either currently under development, at the demonstration or prototype phase or that currently have cost and performance gaps with established technologies.

Importantly, when selecting technologies in a manner that ensures alignment with the Paris Agreement’s temperature goal, companies and financial market participants should bear in mind three important findings by the IPCC and the IEA:

To reach net zero by 2050, no additional fossil fuel exploration should take place (IEA, 2021[38]).

Existing and planned fossil fuel infrastructure, without additional abatement, is equal to CO2 emissions consistent with 2°C pathways and exceed emissions in 1.5°C pathways (IPCC, 2022[31]).

Continuing to install “unabated” fossil fuel infrastructure will lead to emissions lock-in. “Abatement” is in this context defined as “interventions that substantially reduce the amount of GHG emitted throughout the life-cycle”, such as by “capturing 90% or more from power plants, or 50-80% of fugitive methane emissions from energy supply” (IPCC, 2022[31]).

Corporate transition plans that rely on investments in fossil fuel exploration, sale, and distribution will therefore likely not be compatible with the temperature goal of the Paris Agreement and lead to carbon-intensive lock-in.

4.2.3. Element 3: Measuring performance and progress through metrics and KPIs

Credible climate change mitigation-related metrics and KPIs used in transition plans are expected to cover lifecycle GHG emissions, both in absolute terms and intensity-based, and for subsidiary companies. Various accounting methodologies, for example customised for different sectors or for developing countries, for each scope of emissions are detailed in the GHG Protocol Corporate Accounting and Reporting Standard. A credible plan details the KPIs the company will use to measure its performance and progress, and provides the definition of the KPIs, the applicable scope, and the measurement methodology. Credible KPIs are relevant and material to the company’s selected goals and targets, measurable, externally verifiable, and able to be benchmarked (ICMA, 2020[39]).

As discussed earlier in this chapter, there is a growing consensus among market actors on the necessity of reporting scope 3 emissions to the extent possible. Therefore, credible targets will cover emission scopes 1, 2 and, as a rule, 3. Scope 1 emissions are direct emissions of an asset owned by the company (e.g., the direct emissions from a gas-refining operation), scope 2 emissions are indirect emissions from the generation of electricity (e.g., the electricity needed to run the refinery), and scope 3 emissions are all other indirect emissions (except scope 2), both upstream and downstream (see, for example, (MSCI, 2020[40]), (Shrimali, 2021[41])). Targets will include the base year, the targeted reduction (%), the target year, the target’s unit of measurement (e.g., tCO2e and kgCO2e/USD), the year in which the target was set, the percentage of emissions covered by the target, as well as the relevant source documents (CA100+, 2021[42]).

Corporate scope 3 emissions are on average “5.5 times the amount of combined scope 1 and scope 2 emissions” (Shrimali, 2021[41]). Therefore, reporting of scope 3 emissions can avoid shifting the carbon emissions of a business onto its supply chain, accurately capture the climate-related impacts of a business and highlight where the greatest opportunities for emission reductions lie. However, their measurement is challenging due to various sources of uncertainty, such as on the calculation methodologies used, the availability of data (and subsequent use of estimates), and limited ability to influence action up- and downstream, to name a few (see, for example (IFRS, 2022[20]), (Shrimali, 2021[41])).

Against this background, there are divergent approaches among existing disclosure and transition finance initiatives on when scope 3 emissions should be reported and included in target-setting. Existing initiatives tend to be relatively vague in the language employed and frequently do not require explanations or justifications in case of omission, which decreases credibility of plans and comparability across plans. For example, the TCFD recommends the disclosure of “material” scope 3 emissions, when “appropriate” but does not require it (TCFD, n.d.[43]). The current ISSB draft climate-related disclosure requirements generally require the disclosure of scope 3 emissions but also provide the option for companies not to report them, if companies specify which activities have been excluded from reporting. In the case of value chain emissions that are based on reporting by other entities, companies additionally are required to state the reasons for the omission (IFRS, 2022[20]). The proposal for European Sustainability Reporting Standards by EFRAG requires that “significant” scope 3 emissions are reported. Lastly, according to SBTi’s Net Zero Standard, companies must include “relevant” scope 3 emissions in their near-term targets, if they make up 40% or more of total scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions. This Net Zero Standard also requires all companies involved in the sale or distribution of natural gas and/or other fossil fuels to set scope 3 targets for the use of sold products, irrespective of the share of these emissions compared to the total scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions of the company. In addition, all companies must include emissions from all relevant scope 3 categories in long-term targets (SBTi, 2021[44]).

Requirements that use terms such as “significant”, “relevant”, and “material” without providing additional definitions, can lead to a lack of clarity as to which scope 3 emissions should be reported and under which circumstances. This can decrease the credibility of relevant transition plans. Recognising that this is an evolving space, the Guidance considers scope 3 emissions as follows: A credible transition plan will, as a rule, contain scope 3 emissions as part of metrics, targets, and related reporting. However, it is understood that while the inclusion of scope 3 emissions will likely always be relevant for some companies, such as those involved in the extraction, processing, sale or distribution of fossil fuels, they may not always be relevant for all companies in all sectors, such as information technology or communication services (MSCI, 2020[40]). Similarly, some companies, such as some MSMEs, may not be able to obtain or reasonably estimate scope 3 emissions data. To increase clarity and credibility, it is therefore important that:

The corporate includes an explanation on which of the company’s activities were covered in its measure of scope 3 emissions and which were excluded, if any, as well as provides a detailed explanation for the reasons for any exclusions.

If emissions information from entities in the value chain is included in the company’s measure of scope 3 emissions, then the company will explain the basis for measurement. Companies can usefully employ supply chain mapping, as set out in the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct (OECD, 2018[45]), to better assess which parts of the supply chain will be most relevant to their scope 3 measurement.

Omission of scope 3 emissions data can be justified in limited cases and where a careful explanation is provided as part of the plan, including the assumptions used to determine omissions, to provide for comparability across plans and sectors for investors and avoid greenwashing.

4.2.4. Element 4: Providing clarity on use of carbon credits and offsets

Though the terms ‘carbon offsets’ and ‘carbon credits’ are sometimes used interchangeably, they have distinct definitions: According to the Voluntary Carbon Markets Integrity Initiative (VCMI), a carbon credit is “an emissions unit that is issued by a carbon crediting program and represents an emission reduction or removal of greenhouse gases.” Offsetting refers to the process of compensating or cancelling out GHG emissions through “investments in activities that reduce or remove an equivalent amount of GHG emissions, and which are located outside the boundaries of the organisation or a particular product system”. These investments are often made through the purchase (and retirement) of “an amount of carbon credits equivalent to the volume of GHG emissions that is being compensated” (VCMI, 2021[46]). Together, carbon credits and carbon offsets can be understood as “mitigation actions beyond the value chain”, i.e., activities that avoid or reduce emissions outside of a company’s value chain or remove and store emissions from the atmosphere (EFRAG, 2022[47]).

The IPCC distinguishes between two types of CO2 removal: “either enhancing existing natural processes that remove carbon from the atmosphere (e.g., by increasing its uptake by trees or other ‘carbon sinks’) or using chemical processes to, for example, capture CO2 directly from the ambient air and store it elsewhere (e.g., underground)” (IPCC, 2018[25]). OECD analysis acknowledges that removals might need to play a role in balancing out emissions in hard-to-abate sectors where direct mitigation may be extremely costly or technically difficult. Any such use would, however, need to be accompanied by rapid and deep decarbonisation to reduce the absolute level of demand for international credits over time (Jeudy-Hugo, Lo Re and Falduto, 2021[5]).

The idea behind using carbon credits as offsets is to achieve ‘equivalent’ environmental outcomes in a way that is cost-effective and has the potential to deliver finance for emission reductions where it is needed the most. However, there is concern that by counterbalancing emissions, companies are dis-incentivised from reducing their own emissions (VCMI, 2021[46]), thus increasing the risk of carbon-intensive lock-in (EFRAG, 2022[47]). Moreover, carbon markets (voluntary and compliance markets), which form the basis of carbon offset and credit transactions, are heterogeneous and differing crediting activities follow different quality standards with varying levels of environmental integrity. Discussions are ongoing regarding transparency, as well as the role and stringency of different standards in voluntary and compliance markets.

OECD analysis finds that many methodologies to assess the alignment of finance with climate mitigation policy goals currently fail to explicitly assess the treatment of offsets (Noels and Jachnik, forthcoming[1]). Similarly, existing approaches to transition plans and the relevant climate disclosure standards vary in their treatment of offsets. Some initiatives do not consider them to be a substitute for the rapid and deep reduction of a company’s own value chain emissions (see, for example, (SBTi, 2021[44]), (CBI, 2020[48])). This is because a company’s contribution to the emission reductions of others or development of sequestration does not have a direct impact on the GHG emissions of its own value chain, meaning that offsetting and reducing one’s own emissions could be considered as non-fungible actions (Carbone4, 2019[49]).

For example, the proposal by EFRAG as part of the European Sustainability Reporting Standards under development requires the exclusion of purchased offsets or allowances from the calculation of scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions. It allows companies to report the purchase of offsets voluntarily but requires them to do so separately from the GHG inventory and to not disclose offsets as a means to reach their GHG reduction targets, in order to reduce the risks outlined above (EFRAG, 2022[47]). Others, such as the proposal by the ISSB on Climate-related Disclosures, allow for the use of offsets but require additional information on the basis of the carbon removal, the type of verification scheme for the offsets, as well as “any other significant factors necessary for users of […] financial reporting to understand the credibility of the offsets used by the entity” (IFRS, 2022[50]).

Considering ongoing debates and differing views on the use of mitigation actions beyond the value chain (VCMI, 2021[46]), it is important for corporates to consider the risk that use of carbon credits and offsets could decrease the credibility of a corporate transition plan. A credible transition plan will not consider them as an alternative to cutting a company’s emissions today or as a reason for delayed mitigation action, but rather as part of the portfolio of solutions to accelerate the pathway to net zero. Best practices for transition plans that do consider the use of offsets include explicitly describing any intended use of carbon credits and offsets (GFANZ, 2021[23]; CA100+, 2021[42]; TCFD, 2021[18]), the basis for their carbon removal (i.e., whether it is nature- or technology-based), the applicable verification or certification scheme (IFRS, 2022[50]), the quality criteria to be used to assess credibility of offsets, and considering not including them in the GHG inventory and as a contribution to GHG targets. Best practices also include providing an explanation of the additionality and permanence of the offsets, the extent to which they are being used as a last resort (see, for example, (Shrimali, 2021[51])), and clearly stating the share of emissions to be mitigated using offsets (which should decline over time) (CPI, 2022[52]) and their explicit role in the company’s mitigation strategy.

4.2.5. Element 5: Setting out a strategy, actions, and implementation steps, including on preventing carbon-intensive lock-in

A credible transition plan will set out a clear strategy on the path the company intends to take to achieve its targets. The strategy will articulate the transition risks and opportunities that the company expects to face in the short-, medium- and long-term, as well as any foreseen limitations, constraints, and uncertainties to the achievement of the plan’s targets (CDP, 2021[53]; TCFD, 2021[18]). Transition opportunities may include, amongst others, increased sales from products and services that are vital for the transition like the manufacturing and / or installation of renewable energy equipment such as wind turbines or solar panels (sometimes referred to as ‘enabling activities’, as set out above), first-mover advantages, long-term cost savings, and efficiency gains. Transition risks include (i) policy and legal risks that reflect policy changes or litigation action; (ii) technology risk arising from emerging technologies which may impact competitiveness of certain companies; (iii) market risk, arising from changing supply and demand; and (iii) reputational risk, linked to changes in perceptions of customers or society at large (TCFD, 2017[54]).

Assessing the likelihood of achieving the plan’s targets using multiple climate-related scenarios, whenever feasible, will increase the plan’s credibility (TCFD, 2021[18]). Scenario analysis can help companies better understand how transition risks and opportunities (alongside physical risks) might develop and better assess how the business could be affected over time, ultimately supporting the company’s strategic decision-making under uncertainty (TCFD, 2020[55]). In this context, a credible transition plan will also identify levers and corrective actions that could be taken to address or correct underperformance against a target.

To be credible, a transition plan will set out concrete actions to be taken to achieve the defined targets and the capital investments needed, using relevant tools like technology roadmaps and taxonomies, as referenced above. Actions focus on decarbonisation strategies along the value chain, in line with the latest IPCC findings outlined above, which emphasise that deep emission reductions are necessary during this decade and that continued installation of unabated fossil fuel infrastructure will lead to emissions lock-in. In that context, credible planning will identify existing assets and infrastructures, as well as new investments, which are at risk of leading to emissions lock-in and clearly set out the steps to be taken to prevent such lock-in.

Connected to the previous point, the plan also will describe any strategy and process for the responsible retirement for high-emitting corporate assets (GFANZ, 2021[23]), including on how just transition considerations are incorporated (see further details below on just transition). For example, GFANZ suggests setting out a specific phase-out plan as part of transition plans, which could outline, amongst others, how the phase-out is aligned with any net-zero/climate-related strategy, how just transition considerations are taken into account, key milestones such as phase-out timing, key metrics and targets, governance mechanisms, financing plans and key assumptions and uncertainties with the plan (GFANZ, 2022[56]) (see also Box 3.2 in Chapter 3 on coal phase-out).

4.2.6. Element 6: Addressing adverse impacts through the Do-No-Significant-Harm (DNSH) Principle and RBC due diligence

Considering not only climate mitigation targets, but also other environmental objectives (e.g., increasing adaptation and resilience, preventing biodiversity loss, limiting pollution, ensuring sustainable water management, waste management and circular economy considerations, etc.) and social considerations (e.g., pursuing gender equality and women’s empowerment, quality jobs, preventing displacement etc.) can increase the credibility of a transition plan.

Moreover, credibility can also be increased by articulating how the company intends to apply the DNSH Principle and thereby avoid harm to sustainability objectives other than climate mitigation, both at activity- and entity-level. Should there be any unavoidable trade-offs or negative effects on one or more sustainability objectives due to the company’s operations, these could be clearly documented. Ongoing discussions around the DNSH Principle today show that its implementation is still challenging for most entities, so some may choose not to address issues around DNSH in their transition plans.

Three main challenges can be identified: (i) application of the DNSH Principle at the entity level, instead of the economic activity level; (ii) the principle’s applicability outside of the European Union, where it was originally elaborated; and (iii) the limited activity and sectoral coverage of its criteria. The DNSH Principle was first introduced into law as part of the EU Taxonomy, where specific qualitative and quantitative criteria are specified, in order to apply the principle at economic activity or project level, and design projects in a manner that does not do significant harm to broader environmental objectives. However, since the criteria rely to a large extent on European legislation (see, for example, appendix B, C, or D of (EU, 2021[57])), they can be difficult to apply outside of Europe. In this context, DNSH criteria have not been included in the IPSF Common Ground Taxonomy, which maps activities included in the European and the Chinese taxonomies (EU, 2022[58]). Moreover, since the DNSH criteria were developed as part of the existing EU Taxonomy, they cover only the activities included in that taxonomy. While some of the existing criteria might be generic enough to be applicable beyond the activities they were specified for, this might not always be the case. This means that there may currently be no criteria available for activities that are not already included in the EU Taxonomy, but that may form an important part of a corporate’s business activities where the company may wish to still prevent and mitigate harm as part of their transition plan.

Given these challenges, an alternative way to operationalise the DNSH Principle as part of transition plans, especially for companies outside of Europe and companies whose activities are not entirely captured by the EU Taxonomy’s existing criteria, is for businesses and investors to conduct risk-based due diligence based on OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct (RBC) (OECD, 2018[45]). Both the DNSH Principle and the RBC framework set out an expectation that businesses, including investors, avoid and address adverse impacts of their operations (or economic activities), including in their supply chains. The outward-facing approach of RBC due diligence can help them identify, prevent, and mitigate risks on people and planet and similarly on other sustainability objectives (see step 3 of the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for RBC, which sets out practical actions to be taken to “cease, prevent and mitigate adverse impacts”).

Further, the RBC framework can help entities address harm on the full range of sustainability risks and impacts, including social objectives, covered by the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises [OECD/LEGAL/0144, annex]. For example, the OECD has developed sectoral guidance which helps enterprises identify and address environmental and social risks in particular sectors, including in minerals supply chains that will play a significant role in the energy transition (OECD, 2016[59]). As shown in Box 4.2, the minerals sector is one example where investments that contribute to climate change mitigation may present challenging trade-offs with other sustainability objectives, such as risks arising from inadequate waste and water management, and adverse impacts from inadequate worker safety, human rights abuses (such as child labour) and corruption. Companies that conduct effective RBC due diligence can identify, prevent, and mitigate those adverse impacts and fully operationalise the DNSH Principle embedded in a growing number of sustainable finance tools and frameworks.

Box 4.2. The concept of DNSH – the emerging tug-of-war of environmental objectives

The Do-No-Significant-Harm (DNSH) Principle is initially defined under the EU Taxonomy Regulation. The principle requires that economic activities that are classified under the EU Taxonomy as environmentally sustainable do no significant harm to any of the six environmental objectives set out in the Regulation (EU, 2020[11]). These environmental objectives are climate change mitigation, climate change adaptation, pollution prevention, water, circular economy, and biodiversity. The Taxonomy Regulation defines how to evaluate if an activity does significant harm to a specific environmental objective. For example, an activity does significant harm to biodiversity and ecosystems if it is significantly detrimental to the condition and resilience of ecosystems, or the conservation status of habitats and species (EU, 2020[11]). Since the adoption of the DNSH Principle in the EU Taxonomy, other regional taxonomies and definitions have incorporated the Principle in their definition of sustainable activities, including the Malaysian and Singaporean taxonomies ( (Bank Negara Malaysia, 2021[10]), (MAS, 2022[9])). The Principle can be useful for transition plans to ensure overall environmental integrity within corporates’ transition strategies, by not trading off one environmental issue for another.

For each of the activities defined under the EU Taxonomy, thresholds or criteria for DNSH are established, because there is a risk that some activities which are essential for achieving one environmental objective can do significant damage to at least one other environmental objective. DNSH, as set out in the EU Taxonomy, requires that the relevant criteria take into account lifecycle considerations. There are several possible mitigating measures for different types of projects, which are aimed at minimising harm within the boundaries of the project or asset itself. Examples include measures taken by hydropower plants to ensure fish migration, ecological flow, and to prevent the eutrophication of water bodies, and associated significant harm to biodiversity (EU, 2021[57]). For some types of activities, such as purchase and operation of electric vehicles, DNSH criteria also take into account the end-of-life of vehicle fleets, such as when ensuring that the operator has a waste management plan in place to ensure maximum reuse and recycling of batteries and electronics (EU, 2021[57]).

However, there is also a case to be made for analysing the possibility of significant harm within the supply chains of low-carbon technologies, beyond the boundaries of the project or asset. One prominent example is critical minerals. The mining of minerals, crucial to the deployment of climate mitigation technologies, such as low-carbon energy generation, storage, and electric vehicles, also does significant harm to other environmental objectives, including biodiversity, water, and pollution prevention (IEA, 2021[60]). However, to achieve either the IEA’s sustainable development scenario (SDS) or net zero by 2050, mineral demand would increase by 4x and 6x, respectively by 2040 (IEA, 2021[60]). The need to increase extraction of these minerals to achieve climate objectives creates a trade-off with other environmental objectives due to the negative impacts of increased mining. In particular, there are substantial overlaps between global natural capital hotspots and critical mineral reserves, such as in South America, the United States, and parts of Asia (see, for example, (ENCORE, 2022[61]) and (U.S. Geological Survey, 2022[62])). This suggests that the expansion of mining activities to achieve a net-zero future may have material implications for biodiversity. These trade-offs would ideally be considered within corporates’ transition plans, as well as within their financing, to ensure one environmental crisis is not traded out for another.

4.2.7. Element 7: Supporting a just transition

According to the ILO, “a just transition maximises positive economic, social and decent work gains and minimises and mitigates negative impacts” and ensures that “processes and outcomes are inclusive and fair” (ILO, 2022[63]). A credible transition plan will consider how the company’s transition is expected to impact workers, suppliers, local communities and consumers (LSE, 2021[64]). The plan will outline the measures taken to mitigate any negative impact, taking into account the ILO Tripartite Declaration of Principles concerning Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy (ILO, 2017[65]), ILO Guidelines for a Just Transition (ILO, 2015[66]), the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises [OECD/LEGAL/0144, annex] and the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct (RBC) (OECD, 2018[45]), and the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (United Nations, 2011[67]). In particular, the OECD Due Diligence on RBC can help companies avoid and address adverse impacts related to workers, human rights, the environment, consumers, and other dimensions that may be associated with their operations, supply chains and other business relationships.

To help ensure just transition elements are well-integrated and reflect relevant stakeholders’ interest, credible transition plans will be developed through a process that ensures regular and continuous stakeholder engagement and social dialogue, which includes representatives of workers, unions, affected communities and suppliers. The transition plan will have a related human resources strategy ensuring decent work,4 adequate capacity and skills, with a plan for retaining, retraining, reskilling, and education opportunities (CBI, 2021[68]).

The process set out by the OECD Due Diligence Guidance on RBC can involve prioritisation -- where it is not feasible to address all identified impacts at once, a company can prioritise the order in which it acts based on the severity and likelihood of the adverse impact. Once the most significant impacts are identified and dealt with, the company can then move on to address less significant impacts (OECD, 2018[45]). Similarly, to be able to effectively prioritise and deliver just outcomes, corporate efforts in this area should form part of and be informed by coordinated national or subnational policy strategies on the Just Transition.

4.2.8. Element 8: Integration with financial plans and internal coherence

A credible transition plan will not be prepared separate from and without reference to the corporate business plan. Rather, a credible transition plan will be integrated into the corporate business plan. It will make direct reference to the company’s financial plan and be done concurrently with financial reporting. Doing so can explicitly address any needs and commitments for capital expenditure, operating expenditure, merger and acquisition activities and research and development expenditures necessary for the delivery of the transition plan and related targets, so that capital stock, working capital and overall business streams are aligned with the company’s transition targets and KPIs. For some companies, capital allocation plans that support a repositioning of the capital stock will be critical. For others, operating expenditure may be more significant, including costs of retraining and redeploying staff or decommissioning stranded assets, or staff costs to operationalise low-carbon production practices (CBI, 2021[36]).

Moreover, the transition plan will be linked to the company’s purchasing plan for engagement with suppliers, the marketing/sales plan for the engagement with customers as well as be linked to the policy/advocacy plan, for the engagement with trade unions, industry associations, and policymakers (CBI, 2021[68]; GFANZ, 2021[23]; CA100+, 2021[42]).

4.2.9. Element 9: Ensuring sound governance and accountability

A whole-of-entity approach will be essential in both the design and implementation of the transition plan, involving all relevant stakeholders (workers, suppliers, consumers, impacted communities, if any, etc.). A credible plan will clearly define a process and responsibilities for regular monitoring and reporting of progress towards targets, as well as for any timely and regular revision and update of this plan (e.g., on an annual basis), to take stock of lessons learnt, revisit assumptions, and identify levers for action, especially in areas that may be falling behind. The plan will be subject to board and senior management approval and oversight.

4.2.10. Element 10: Transparency and verification, labelling and certification

A credible transition plan will contain company commitments to regularly disclose targets (and underlying assumptions) and progress towards their achievement, to both internal and external stakeholders. The company will pursue third-party verification of its plan and related targets. This is also recommended as part of the OECD Policy Guidance on Market Practices to Finance a Climate Transition and Strengthen Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Investing, which states that effective monitoring, including through third-party verification, of data and targets used in transition plans should be encouraged (OECD, forthcoming[69])

Standards for verification and appropriate verification providers will depend on the jurisdiction in which the corporate operates and the contents of the transition plan. There is currently no international framework for accreditation of verifiers for corporate transition plans. However, some existing initiatives set out verifiers or verification standards that they recommend or require for compliance with their standards or certifications, which can provide some guidance to users and preparers of transition plans on the appropriateness of different verifiers (see, for example, (CDP, 2022[70]), (CBI, 2022[71])). In addition, it is encouraged that policymakers collaborate with stakeholders and experts to improve existing verification and monitoring frameworks offered by third parties (OECD, forthcoming[69]).

Some companies may in addition be able to achieve certification, such as through SBTi (SBTi, 2021[44]) or through future schemes that are currently under development like, for instance, through CBI (CBI, 2021[36]). This can increase credibility but may not be feasible for all companies.

References

[35] ASEAN (2021), ASEAN Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance.

[10] Bank Negara Malaysia (2021), Climate change and Principle-based Taxonomy, https://www.bnm.gov.my/documents/20124/938039/Climate+Change+and+Principle-based+Taxonomy.pdf.

[42] CA100+ (2021), Net Zero Company Benchmark, https://www.climateaction100.org/net-zero-company-benchmark/ (accessed on 29 April 2022).

[49] Carbone4 (2019), Stop saying “carbon offset”: Moving from “offsetting” to “contributing”, https://www.carbone4.com/stop-saying-carbon-offset-from-offsetting-to-contributing (accessed on 6 July 2022).

[71] CBI (2022), Approved Verifiers under the Climate Bonds Standard, https://www.climatebonds.net/certification/approved-verifiers (accessed on 20 June 2022).

[68] CBI (2021), Transition finance for transforming companies, https://www.climatebonds.net/files/files/Transition%20Finance/Transition%20Finance%20for%20Transforming%20Companies%20ENG%20-%2010%20Sept%202021%20.pdf.

[36] CBI (2021), Transition finance for transforming companies: Avoiding greenwashing when financing company decarbonisation, https://www.climatebonds.net/files/files/Transition%20Finance/Transition%20Finance%20for%20Transforming%20Companies%20ENG%20-%2010%20Sept%202021%20.pdf.

[48] CBI (2020), Financing Credible Transitions: Summary Note, https://www.climatebonds.net/resources/reports/financing-credible-transitions-summary-note.

[70] CDP (2022), Verification, https://www.cdp.net/en/guidance/verification (accessed on 20 June 2022).

[53] CDP (2021), Climate Transition Plan: Discussion Paper, https://cdn.cdp.net/cdp-production/cms/guidance_docs/pdfs/000/002/840/original/Climate-Transition-Plans.pdf?1636038499.

[29] Climate Action Tracker (2022), Countries, https://climateactiontracker.org/countries/ (accessed on 20 June 2022).

[52] CPI (2022), What Makes a Transition Plan Credible? Considerations for financial institutions, https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Credible-Transition-Plans.pdf.

[47] EFRAG (2022), Draft European Sustainability Reporting Standard E1 Climate change, https://www.efrag.org/Assets/Download?assetUrl=/sites/webpublishing/SiteAssets/Appendix%202.5%20-%20WP%20on%20draft%20ESRS%20E1.pdf&AspxAutoDetectCookieSupport=1g.

[61] ENCORE (2022), Hotspots, https://encore.naturalcapital.finance/en/map?view=hotspots (accessed on 31 May 2022).

[58] EU (2022), International Platform on Sustainable Finance, https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/business_economy_euro/banking_and_finance/documents/220603-international-platform-sustainable-finance-common-ground-taxonomy-table-faq_en.pdf.

[57] EU (2021), “Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/2139 of 4 June 2021 supplementing Regulation (EU) 2020/852 of the European Parliament and of the Council”, Official Journal of the European Union, Vol. OJ L 442, pp. 1–349, http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg_del/2021/2139/oj.

[11] EU (2020), Regulation (EU) 2020/852 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 June 2020 on the establishment of a framework to facilitate sustainable investment, and amending Regulation (EU) 2019/2088, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:32020R0852.

[12] European Commission (2022), International Platform on Sustainable Finance, https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/banking-and-finance/sustainable-finance/international-platform-sustainable-finance_en (accessed on 14 June 2022).

[37] European Commission (2022), International Platform on Sustainable Finance on Common Ground Taxonomy - Instruction report (updated), https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/business_economy_euro/banking_and_finance/documents/220603-international-platform-sustainable-finance-common-ground-taxonomy-instruction-report_en.pdf.

[16] European Commission (n.d.), Corporate sustainability reporting, https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/company-reporting-and-auditing/company-reporting/corporate-sustainability-reporting_en (accessed on 14 June 2022).

[56] GFANZ (2022), The Managed Phaseout of High-emitting Assets, https://assets.bbhub.io/company/sites/63/2022/06/GFANZ_-Managed-Phaseout-of-High-emitting-Assets_June2022.pdf.

[23] GFANZ (2021), GFANZ Progress Report, https://assets.bbhub.io/company/sites/63/2021/11/GFANZ-Progress-Report.pdf.

[27] Government Offices of Sweden (2022), The Swedish climate policy framework, https://www.government.se/495f60/contentassets/883ae8e123bc4e42aa8d59296ebe0478/the-swedish-climate-policy-framework.pdf.

[39] ICMA (2020), Climate Transition Finance Handbook, https://www.icmagroup.org/assets/documents/Regulatory/Green-Bonds/Climate-Transition-Finance-Handbook-December-2020-091220.pdf.

[30] IEA (2021), COP26 climate pledges could help limit global warming to 1.8 °C, but implementing them will be the key, https://www.iea.org/commentaries/cop26-climate-pledges-could-help-limit-global-warming-to-1-8-c-but-implementing-them-will-be-the-key (accessed on 8 July 2022).

[38] IEA (2021), Net Zero by 2050 - A Roadmap for the Gobal Energy Sector - Summary for Policy makers, IEA Publications, https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/7ebafc81-74ed-412b-9c60-5cc32c8396e4/NetZeroby2050-ARoadmapfortheGlobalEnergySector-SummaryforPolicyMakers_CORR.pdf.

[26] IEA (2021), Net-Zero by 2050: A Global Roadmap for the Energy Sector, https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/deebef5d-0c34-4539-9d0c-10b13d840027/NetZeroby2050-ARoadmapfortheGlobalEnergySector_CORR.pdf.

[60] IEA (2021), Total mineral demand for clean energy technologies by scenario, 2020 compared to 2040, https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/total-mineral-demand-for-clean-energy-technologies-by-scenario-2020-compared-to-2040 (accessed on 15 June 2022).

[33] IEA (2020), Iron and Steel Technology Roadmap, https://www.iea.org/reports/iron-and-steel-technology-roadmap.

[20] IFRS (2022), Draft IFRS S2 Climate-related Disclosures, https://www.ifrs.org/content/dam/ifrs/project/climate-related-disclosures/issb-exposure-draft-2022-2-climate-related-disclosures.pdf.

[50] IFRS (2022), Exposure Draft IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standard - [Draft] IRFS S2 Climate-related Disclosures, https://www.ifrs.org/content/dam/ifrs/project/climate-related-disclosures/issb-exposure-draft-2022-2-climate-related-disclosures.pdf.

[14] IFRS (2021), International Sustainability Standards Board, https://www.ifrs.org/groups/international-sustainability-standards-board/ (accessed on 14 June 2022).

[24] IGCC (2022), Corporate Climate Transition Plans: A guide to investor expectations, https://igcc.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/IGCC-corporate-transition-plan-investor-expectations.pdf.

[72] ILO (2022), Decent work, https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/decent-work/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 1 May 2022).

[63] ILO (2022), Finance for a Just Transition and the Role of Transition Finance, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/documents/genericdocument/wcms_848640.pdf.

[65] ILO (2017), Tripartite Declaration of Principles concerning Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/---emp_ent/---multi/documents/publication/wcms_094386.pdf.

[66] ILO (2015), Guidelines for a just transition towards environmentally sustainable economies and societies for all, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_emp/@emp_ent/documents/publication/wcms_432859.pdf.

[13] IMF-World Bank-OECD-BIS (forthcoming), Operationalization guidance of the high-level principles for sustainable finance alignment approaches.

[31] IPCC (2022), Sixth Assessment Report - Mitigation of Climate Change: Summary for Policymakers, https://www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-report-working-group-3/ (accessed on 21 April 2022).

[25] IPCC (2018), Summary for Policymakers — Global Warming of 1.5 ºC, https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/chapter/spm/ (accessed on 1 May 2022).

[5] Jeudy-Hugo, S., L. Lo Re and C. Falduto (2021), “Understanding countries’ net-zero emissions targets”, OECD/IEA Climate Change Expert Group Papers, Vol. 2021/03.

[64] LSE (2021), 2021 Report of the UK Financing a Just Transition Alliance, https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Just-Zero_2021-Report-of-the-UK-Financing-a-Just-Transition-Alliance.pdf.

[9] MAS (2022), Identifying a Green Taxonomy and Relevant Standards for Singapore and ASEAN, https://abs.org.sg/docs/library/second-gfit-taxonomy-consultation-paper.

[6] METI (2021), Taskforce Formulating Roadmaps for Climate Transition Finance Established, Plus Call for Examples of Model Projects, https://www.meti.go.jp/english/press/2021/0604_003.html (accessed on 14 June 2022).

[40] MSCI (2020), Scope 3 Carbon Emissions: Seeing the Full Picture, https://www.msci.com/www/blog-posts/scope-3-carbon-emissions-seeing/02092372761 (accessed on 13 June 2022).

[34] National Treasury, Republic of South Africa (2022), South African Green Finance Taxonomy, http://www.treasury.gov.za/comm_media/press/2022/SA%20Green%20Finance%20Taxonomy%20-%201st%20Edition.pdf.

[21] Net Zero Tracker (2022), Net Zero Tracker, https://zerotracker.net/analysis (accessed on 10 June 2022).

[22] New Climate Institute and Carbon Market Watch (2022), Corporate Climate Responsibility Monitor 2022, https://newclimate.org/sites/default/files/2022-06/CorporateClimateResponsibilityMonitor2022.pdf.

[8] NGFS (2022), Enhancing market transparency in green and transition finance, https://www.ngfs.net/sites/default/files/medias/documents/enhancing_market_transparency_in_green_and_transition_finance.pdf.

[1] Noels, J. and R. Jachnik (forthcoming), Assessing the climate consistency of finance: taking stock of methodologies and their links to climate policy objectives, OECD Environment Working Papers, http://www.oecd.org/environment/workingpapers.htm .

[32] OECD (2022), 2022 Ministerial Council Statement, https://www.oecd.org/mcm/2022-MCM-Statement-EN.pdf.

[28] OECD (2021), Regional Outlook 2021 - Country notes Finland, https://www.oecd.org/regional/RO2021%20Finland.pdf.

[7] OECD (2020), Developing Sustainable Finance Definitions and Taxonomies, Green Finance and Investment, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/134a2dbe-en.

[45] OECD (2018), OECD Due Diligence Guidance on Responsible Business Conduct, OECD Publishing, https://mneguidelines.oecd.org/OECD-Due-Diligence-Guidance-for-Responsible-Business-Conduct.pdf.

[59] OECD (2016), OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas: Third Edition, OECD publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264252479-en.

[69] OECD (forthcoming), Policy Guidance on Market Practices to Finance and Strengthen ESG Investing: Input to the G20 Sustainable Finance Working Group, OECD Publishing.

[74] PRI (2020), How Policy Makers Can Implement Reforms for a Sustainable Financial System: Part I - a Toolkit for Sustainable Investment Policy and Regulation, https://www.unpri.org/download?ac=12247.

[15] SASB (2020), Proposed changes to the SASB conceptual framework & rules of procedure: Basis for conclusions and invitation to comment on exposure drafts, https://www.sasb.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/PCP-package_vF.pdf.

[44] SBTi (2021), SBTi Corporate Net-Zero Standard, https://sciencebasedtargets.org/resources/files/Net-Zero-Standard.pdf.

[19] SBTi (2021), SBTi Criteria and Recommendations, https://sciencebasedtargets.org/resources/files/SBTi-criteria.pdf.

[41] Shrimali, G. (2021), Measuring and Managing Scope 3 Emissions, https://energy.stanford.edu/sites/g/files/sbiybj9971/f/measuring_and_managing_scope_3_emissions_-_executive_summary_0.pdf.

[51] Shrimali, G. (2021), Transition Bond Frameworks: Goals, Issues, and Guiding Principles, https://energy.stanford.edu/sites/g/files/sbiybj9971/f/transition_bond_frameworks-_goals_issues_and_guiding_principles_0.pdf.

[18] TCFD (2021), Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures - Guidance on Metrics, Targets, and Transition Plans, https://assets.bbhub.io/company/sites/60/2021/07/2021-Metrics_Targets_Guidance-1.pdf.

[55] TCFD (2020), Guidance on Scenario Analysis for Non-Financial Companies, https://assets.bbhub.io/company/sites/60/2020/09/2020-TCFD_Guidance-Scenario-Analysis-Guidance.pdf.

[54] TCFD (2017), Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures, https://assets.bbhub.io/company/sites/60/2020/10/FINAL-2017-TCFD-Report-11052018.pdf.

[43] TCFD (n.d.), Metrics and Targets, https://www.tcfdhub.org/metrics-and-targets/ (accessed on 14 June 2022).

[3] Teske, S. et al. (2020), Sectoral pathways to net zero emissions, https://www.unepfi.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/OECM-Sector-Pathways-Report-FINAL-20201208.pdf.

[4] TPI (2022), TPI Sectoral Decarbonisation Pathways, https://www.transitionpathwayinitiative.org/publications/100.pdf?type=Publication.

[62] U.S. Geological Survey (2022), Mineral Commodity Summaries 2022, https://doi.org/10.3133/mcs2022.

[17] U.S. SEC (2022), SEC Proposes Rules to Enhance and Standardize Climate-Related Disclosure for Investors, https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2022-46 (accessed on 14 June 2022).

[2] UNEP (2022), UN-convened Net-Zero Asset owner Alliance: Target Setting Protocol - Second Edition, UN Environment Programme Finance Initiative.

[73] UNFCCC (2015), The Paris Agreement, https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement.

[67] United Nations (2011), UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/documents/publications/guidingprinciplesbusinesshr_en.pdf.

[46] VCMI (2021), Aligning Voluntary Carbon markets with the 1.5°C Paris Agreement Ambition, https://vcmintegrity.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/VCMI-Consultation-Report.pdf.

Notes

← 1. For a more holistic and general overview of sustainable finance tools and frameworks, see for instance (PRI, 2020[74]).

← 2. See TCFD’s Guidance on Scenario Analysis for Non-Financial Companies for further insights on the role of scenario analysis in setting climate-related targets (TCFD, 2020[55]).

← 3. Article 2.1a of the Paris Agreement commits to “holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels” (UNFCCC, 2015[73])

← 4. The ILO defines decent work as “work that is productive and delivers a fair income, security in the workplace and social protection for families, better prospects for personal development and social integration, freedom for people to express their concerns, organize and participate in the decisions that affect their lives and equality of opportunity and treatment for all women and men” (ILO, 2022[72]).