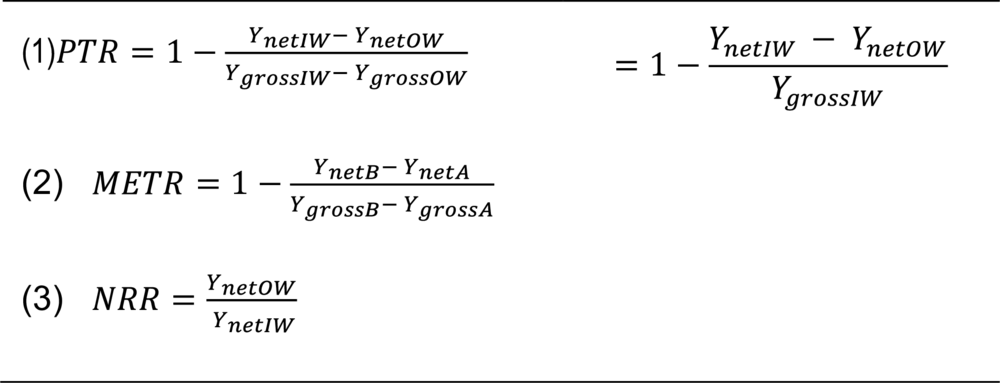

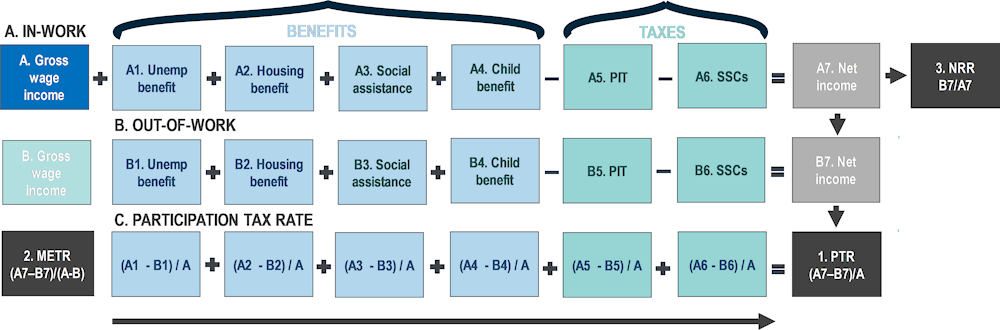

The participation tax rate measures the incentives to enter work produced by the tax and benefit system. Figure A A.3. provides a diagrammatic illustration for calculating the financial measures in Figure A A.2.. Figure A A.3. shows that PTRs can be conceptualised as the difference between net income in-work and out-of-work as a share of gross wage income. The PTR can be further decomposed into tax and benefit components as a share of gross wage income. The PTR tell us about the role of the tax and benefit system in individual incentives by measuring how much is taxed away and lost in benefits as an individual moves from unemployment to work (or perhaps more simply the proportion of gross earnings lost in more tax and less benefits). Since PTRs are calculated as a share of wages, PTRs will only accurately represent the incentives faced by unemployed individuals that, as part of their decision to enter work, incorporate what they could hypothetically earn if they were in work. However, if an unemployed individual adopts as a conceptual benchmark their net out-of-work income (and disregards their hypothetical in-work gross income), then the incentive they respond to would be better measured by a straightforward proportion of the additional net income that they would gain from working (for further discussion and an example, see Figure 4.21). Figure A A.3. also illustrates how the NRR can be calculated as net income out-of-work as a share of net income in-work and the METR by replacing out-of-work gross income with a lower level of in-work income.

Work attractiveness as measured by the PTR is only increased by tax and benefit cuts that widen the gap between net income in-work and out-of-work. Since the PTR measures the difference in net income in and out of work, lower taxes or reduced benefits will not increase work incentive if they are provided equally for the employed and unemployed. For example, universal child benefit or housing benefit provided to families regardless of employment status will have no impact on incentives as measured by the PTR. Instead, work attractiveness will only increase if the gap between net income in-work and out-of-work is widened.

PTR and METR financial measures have caveats including that they do not examine dynamic affects and so complementing them with mobility analysis is important. To what extent are low paying job stepping stones to better careers? The static nature of financial measures such as PTRs and METRs is that they do not capture dynamic effects such as whether a low-paid job may be seen as a steppingstone to a better career . While policymakers are rightly concerned about high at-risk-of-poverty rates for some groups, it is often wrongly assumed that the same individual stay poor. On the contrary, in many countries the membership of the so-called poor is in constant flux – that poor people this year are not necessarily the poor people next year. The extent of this flux is captured by income mobility (who moves up and down the income ladder over time), which is then an important complement to such financial measure analysis. In addition, it could be that certain policies affect the pattern of mobility by acting as a ‘mobility lever’ to help move lower income workers up the income ladder over time ( (Mitnik et al., 2015[1])). For example, extending the duration of unemployment benefit could provide low-income workers with more time to find a job that matches skills that then leads to a better job and upward mobility. Such a dynamic process is not captured in what would be measured as a high PTR and a low work incentive. A further dynamic process not captured by these financial measures is that individuals may respond differently to time-limited incentives. Building further on the unemployment benefit example described above, the incentive to work is unlikely to remain constant (as predicted by a PTR) over time-limited unemployment spells durations. In Lithuania, the PTR is the same during unemployment durations between 6 and 9 months, although the likelihood and intensity with which the unemployed try to find a job likely increases during those final months.