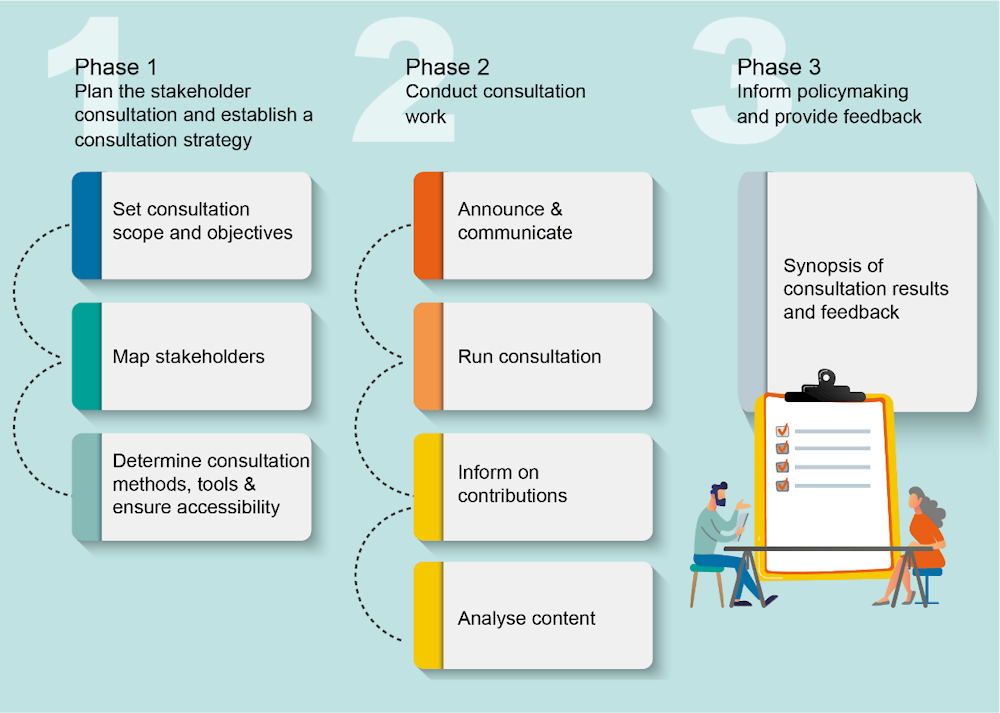

This chapter provides examples and guidance on how to regularly assess the performance of legal frameworks, to see if they have reached their goals and whether social and solidarity economy (SSE) entities comply with their societal objectives. The chapter speaks to the importance of defining a formal evaluation mechanism that includes relevant stakeholders. It touches on the need for criteria to evaluate processes and outcomes, capitalising on regulatory impact analysis (RIA) and international standards to support the evaluation process of legal frameworks for SSE.

Policy Guide on Legal Frameworks for the Social and Solidarity Economy

3. Evaluate the performance of legal frameworks

Abstract

Why is this important?

Periodically evaluating legal frameworks for the social and solidarity economy (SSE) can support many objectives. It can help to assess how legal frameworks impact activities of SSE entities. It can also help to build the necessary information to support reforms, adaptations and improvements to laws. Despite the widespread adoption of legal frameworks for the SSE, only a handful of countries and regions (e.g Canada (Québec), France, Luxembourg and Mexico) have included formal mechanisms to evaluate their performance. The lack of regular evaluation may prevent countries and regions from timely amending, adapting and evolving legal frameworks thus creating additional barriers relative to other legal forms.

To be useful, evaluation requires a formal mechanism to assess both processes and outcomes. In the area of legal frameworks, the “input-process-output-outcome” approach aims to assist authorities in evaluating each step, from the design and implementation to the achievement of strategic objectives of laws and regulations (OECD, 2014[1]). Processes refer to how legal frameworks are developed and enforced. Outcomes refer to whether legal frameworks have reached their objectives and their potential implications (positive and negative) on ecosystem development. This also helps determine the need for updates or revisions of laws.

This section provides guidance to help countries assess the performance of legal frameworks for the SSE. It outlines possible criteria and tools for evaluating processes and outcomes.

How can policy makers help?

Infographic 3.1. Guiding questions: Evaluation phase

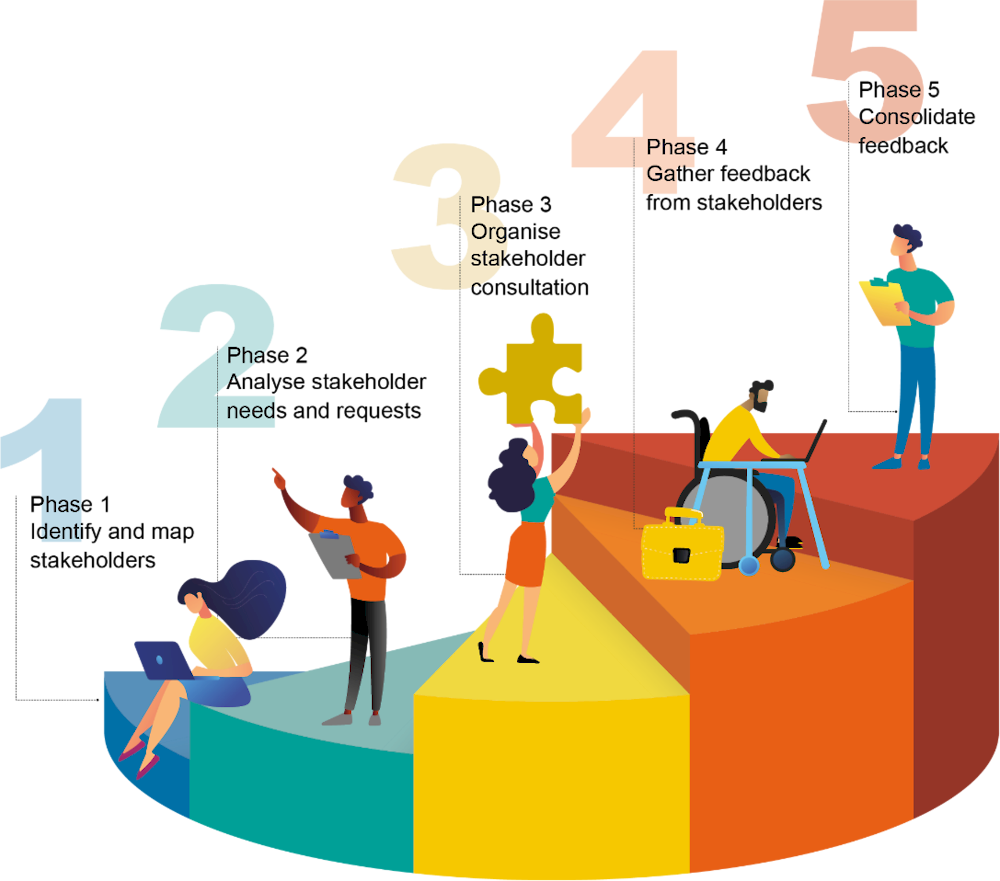

Across countries the following success factors and pitfalls to avoid can help to evaluate the performance of legal frameworks for the SSE.

Infographic 3.2. Success factors and pitfalls to avoid: Evaluation phase

Treasure the law evaluation mechanisms to adjust or improve legal frameworks for the SSE

Define a formal evaluation mechanism that involves stakeholders to regularly assess legal frameworks

Countries and regions that evaluate legal frameworks for the SSE have done so by including formal mechanisms in SSE laws themselves. The need for evaluating legal frameworks for the SSE has been expressed by public authorities and SSE entities in many countries. A formal mechanism helps to provide constant feedback on the performance and unexpected outcomes of legislation. The OECD 2012 Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance, the 2014 Framework for Regulatory Policy Evaluation (Box 3.1) and the EU Better Regulation Guidelines and Toolbox (Box 3.2) offer guidance on the kind of elements which authorities could consider when designing an evaluation mechanism for legislation. For example, the province of Québec (Canada) has tailored international guidance on evaluation to SSE needs and specificities (Box 3.3).

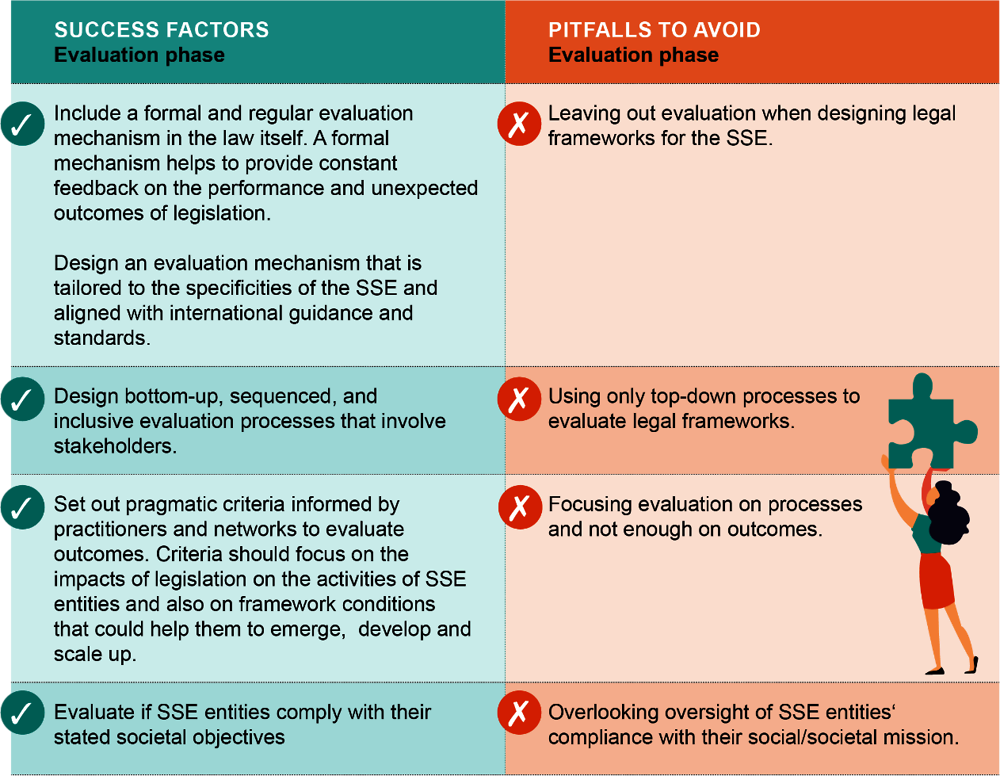

Typically, evaluation mechanisms would include stakeholder consultation, ex-ante and ex-post assessment and periodicity.

Stakeholder consultation. Consultation should be open to interested groups and the public. Engaging stakeholders during the regulation-making process and designing consultation processes aim to maximise the collection of quality information as well as local SSE practices are reflected and integrated in laws. A wide range of approaches could be used including informal consultation, circulation for comments, public hearings or creation of advisory bodies. For example, article 16 of the 2013 Social Economy Act implemented in the Province of Québec (Canada) introduced an accountability mechanism. The Act recognises stakeholder roundtables and establishes an obligation for dialogue between provincial authorities and stakeholders (Box 3.3).

Ex-ante assessment. This helps to determine the need for introducing new regulation or if revising existing legislation is sufficient.

Ex-post evaluation. This helps to assess if laws are effective, efficient, coherent and simple to use. For example, in the Netherlands, the senate assesses legislation based on the criteria of effectiveness and simplicity which are common principles that need to be included in laws.

Periodicity. Evaluation needs to be clearly defined in time to inform when it takes place. For example, in France the 2014 Law on the Social and Solidarity Economy states that an assessment of the law needs to be performed every two years. In Luxembourg, the 2016 Law that created a new legal status for social enterprises, the Societal Impact Companies (Sociétés d’Impact Sociétal – SIS) specifies that the law must be assessed, under the responsibility of the ministry in charge of the social and solidarity economy, within three years after its enforcement.

Box 3.1. OECD Framework for Regulatory Policy

Pursuing “regulatory quality” is about enhancing the performance, cost-effectiveness, and legal quality of regulations and administrative formalities. The notion of regulatory quality covers processes, i.e. the way regulations are developed and enforced and their compliance with the principles of consultation, transparency, accountability and evidence. It also covers outcomes, i.e. whether regulations are effective, efficient, coherent and simple.

In practice, this means that laws and regulations should:

1. serve clearly identified policy goals, and are effective in achieving those goals;

2. be clear, simple, and practical for users;

3. have a sound legal and empirical basis,

4. be consistent with other regulations and policies;

5. produce benefits that justify costs, considering the distribution of effects across society and taking economic, environmental and social effects into account;

6. be implemented in a fair, transparent and proportionate way;

7. minimise costs and market distortions;

8. promote innovation through market incentives and goal-based approaches; and,

9. be compatible as far as possible with competition, trade and investment facilitating principles at domestic and international levels.

Source: (OECD, 2012[2]; OECD, 2014[1]; OECD, 2018[3])

Box 3.2. The EU Better Regulation Guidelines and Toolbox

The European Commission's Better Regulation policy emerged in the early 2000s and has gradually evolved since. The Commission applies it in its own law- and policy-making and encourages also the other EU institutions and the EU Member States to do likewise.

In 2015, the European Commission released the Better Regulation’ Guidelines. ‘Better Regulation’ is defined in these Guidelines as an approach to policy and law-making that reaches objectives at minimum costs and ensures that political decisions are prepared transparently with the involvement of stakeholders and informed by the best possible evidence.

It is based on the principles of necessity (need for intervention), proportionality (not to go beyond what is strictly needed), subsidiarity (to act at the appropriate level of governance and only at EU level when it cannot be done nationally or locally) and transparency.

The Better Regulation Guidelines set out in particular that law and policy-making have to be:

open and transparent;

backed by the comprehensive involvement of stakeholders and;

informed by a sound evidence base.

The Better Regulation’ Guidelines are complemented by the Better Regulation "Toolbox". Three tools provide Better Regulation with the means to deliver evidence-based policy-making, namely:

ex-ante impact assessment (also referred to as RIA in some countries);

ex-post evaluation and;

involvement of the public and stakeholders through consultation.

Better Regulation should lead to an improved quality of legislation, simplification and a reduction of regulatory burdens, including cumulative ones – all while maintaining benefits. Inspired by the drive for sustainable development, it takes into consideration the social, environmental and economic impact of policies and laws.

Source: (European Commission, 2017[4])

Box 3.3. The Accountability Mechanism of the Québec Social Economy Act (Canada)

The Province of Québec in Canada adopted the Social Economy Act in 2013 with the objective to recognise the contribution of the social economy to socioeconomic development and to sustain the government’s commitment to the social economy in the long run.

The Act sets up an accountability mechanism to assess its outcomes. This accountability mechanism relies on three pillars:

the establishment of a privileged relationship, encouraging dialogue, between the government and the social economy stakeholders, and the member-organisations of the Panel of Social Economy Partners, namely the Chantier de l’économie sociale, the Conseil québécois de la coopération et de la mutualité;

an obligation to adopt an action plan on the social economy, after consultation of the social economy stakeholders, every five years. The action plan also establishes the reporting mechanisms to account for the policy actions taken to support the social economy;

a requirement to publish a report on the implementation of the action plan, which is also tabled in the National Assembly. The report serves, in combination with stakeholder consultations, as the basis to design the subsequent action plan.

In addition, a ten-year report is envisaged to assess the Social Economy Act and its long-term effectiveness, with the objective of taking stock, reporting on changes having taken place, and adapting law to changing realities.

Source: Social Economy Act (Québec, 2013), OECD stakeholder consultations, OECD international expert meeting on “Leveraging Legal Frameworks to Scale the Social and Solidarity Economy” (10 December 2020), (Québec, 2020[5])

Set out pragmatic criteria to evaluate processes and outcomes

Evaluation criteria that are used often cover processes and outcomes. A pragmatic approach to criteria could be informed by practitioners and networks. Criteria could include impact measurement to understand in which context some legal options are more appropriate than others. The assessment should also benefit from feedback of users/beneficiaries of legal frameworks.

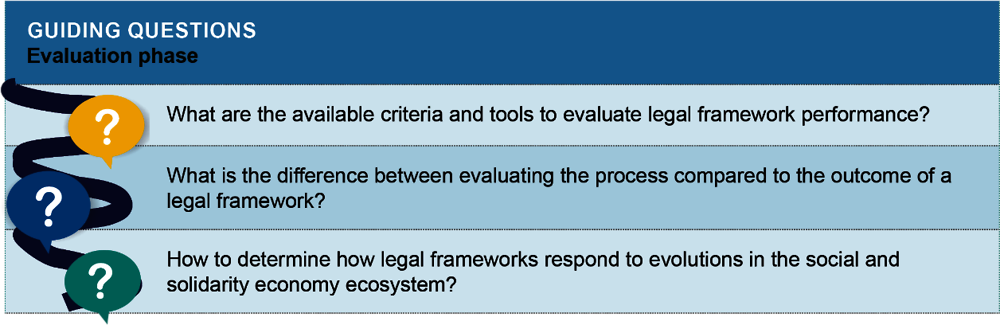

Processes

Successful processes leading to the design of legal frameworks for the SSE usually are bottom-up, sequenced and inclusive of stakeholders (Infographic 3.3). Some countries developed good practices (sometimes enshrined in the law itself) to ensure that steps leading to the design of legal frameworks are the outcome of co-construction processes involving networks and stakeholders across levels of government and sectors (Box 3.4).

Infographic 3.3. Main steps of the consultation process

Infographic 3.4. Phases of the consultation process

Box 3.4. Examples of inclusive and open processes to legal frameworks for social enterprises

Denmark: A specific National Committee was created in order to prepare the Act of 2014.

France: Although the 2014 Framework Law on the Social and Solidarity Economy does not set a specific method or tool to assess the performance of the law, it states the need for a bi-annual assessment. It also refers to the bi-annual conferences that mobilise national and subnational authorities as well as SSE representatives and networks to take stock of achievements and explore opportunities to improve laws, policies and strategies.

In Mexico: The 2012 Law on the Social and Solidarity Economy specifies that an independent entity should have the responsibility to evaluate legal frameworks. The Council for the Evaluation of Social Policies is responsible for evaluation. Having a specialised institution leading the evaluation process is considered as a success factor. Nevertheless, the institution being part of the administration, the evaluation process might be viewed as a control mechanism (Raquel Ortiz-Ledesma, 2019[7]).

Slovakia: A two-year long consultation process was held during which inputs were collected from academics, social entrepreneurs and local governments, before adopting the Act on Social Economy and Social Enterprises in 2018.

Spain: A partnership model was developed to promote strong involvement of different stakeholders in processes pertaining to laws such the Law on the Social Economy in 2011 (Law 5/2011) which recognises the concept of social enterprise. The stakeholders include regional authorities, universities, associations, and the private sector (e.g. the Mondragon Cooperative Corporation) in addition to the Spanish Business Confederation of Social Economy (CEPES): an umbrella organisation created in 1992 representing the companies of the social economy.

Source: (OECD, 2022[8])

Outcomes

Outcomes of legislation are usually linked to the issues and priorities that supported the introduction of laws. As a result, assessments of outcomes need to be country-specific and use criteria that measure the impacts of legislation on activities of SSE entities. For example, they could include the number of business closures (in the case of social enterprises); the geography of SEE entities (urban/rural); the number and quality of jobs created by them and their contribution to the implementation of strategic priorities and policies. This could help to better understand why some legal frameworks are not appropriate in supporting SSE entities, and identify their unexpected consequences such as more red tape, additional administrative burdens, heavy reporting procedures restrictions; complexity; lack of demand for legislation, or poor knowledge of SSE entities needs. Strategies to assess the outcomes of legal frameworks for the SSE should include end-users/ beneficiaries of regulation i.e. SSE networks and/or their representatives. This could facilitate revisions and updates of laws when appropriate as demonstrated by the example of Luxembourg (Box 3.5).

Ultimately, the assessment of outcomes should help countries set better framework conditions for the SSE. As such, it should help achieve more recognition and visibility of the SSE; legal clarity around definitions; removal of market barriers or distortions for SSE entities; better access to finance; design of tailored taxation, etc.

Box 3.5. Luxembourg’ outcome assessment of legal frameworks for the SSE

In 2016, Luxembourg adopted a law to regulate the creation of social enterprises under a new legal status: the Societal Impact Companies (Sociétés d’Impact Sociétal – SIS). This law defines principles of the social and solidarity economy (SSE) and stipulates that the law must be assessed within three years after its enforcement. Since 2016, two evaluations were conducted with the involvement of stakeholders. The Luxembourg Ministry of Labour, Employment and Social and Solidarity Economy (MTEESSS) conducted consultations, including workshops, expert consultations, surveys, and a large-scale seminar with SSE crucial stakeholders.

As a result, amendments to the law that were adopted in 2018 resolved many of the residual uncertainties related to the transition of SSE entities to the SIS regime. Specifically, this entailed amending existing legislation to extend specific rights such as tax exemptions to SISs that previously advantaged non-profit organisations and foundations.

Consequently, the number of SISs increased: as of July 2019, there were 31 registered SISs, 25 of which obtained their accreditation after the 2018 amendment. The most recent amendment in 2021 took into account the unprecedented challenges SISs had to face during the COVID-19 pandemic and addressed the need to reduce the administrative burden to create incentives for more entrepreneurs to adopt the SIS accreditation.

Source: (OECD, 2022[8])

Regulatory Impact Analysis (RIA) could support evaluation of outcomes of legal frameworks for the SSE. RIA is a decision tool to (i) systematically and consistently examine potential impacts arising from government action and (ii) communicate the information to decision-makers. Legal frameworks are often designed without enough knowledge of their consequences due to the lack of ex-ante assessment. This lack of understanding could lead to regulations being less effective, unnecessary and even burdensome. Therefore, Regulatory Impact Analysis applied to legal frameworks for the SSE can be an effective strategy for improving their quality and ensuring that regulations are fit for purpose and will not cause more issues than they solve. The OECD developed a set of best practices for RIA that could inspire evaluation of outcomes of legal frameworks designed for the SSE (Box 3.6).

Box 3.6. Regulatory Impact Analysis (RIA)’s Best Practices

1. Maximise political commitment to RIA

Reform principles and the use of RIA should be endorsed at the highest levels of government. RIA should be supported by clear ministerial accountability for compliance.

2. Allocate responsibilities for RIA programme elements carefully

Locating responsibility for RIA with regulators improves “ownership” and integration into decision-making. An oversight body is needed to monitor the RIA process and ensure consistency, credibility and quality. It needs adequate authority and skills to perform this function.

3. Train the regulators

Ensure that formal, properly designed programmes exist to give regulators the skills required to do high quality RIA.

4. Use a consistent but flexible analytical method

The benefit/cost principle should be adopted for all regulations, but analytical methods can vary as long as RIA identifies and weighs all significant positive and negative effects and integrates qualitative and quantitative analyses. Mandatory guidelines should be issued to maximise consistency.

5. Develop and implement data collection strategies

Data quality is essential to useful analysis. An explicit policy should clarify quality standards for acceptable data and suggest strategies for collecting high quality data at minimum cost within time constraints.

6. Target RIA efforts

Resources should be applied to those regulations where impacts are most significant and where the prospects are best for altering regulatory outcomes. RIA should be applied to all significant policy proposals, whether implemented by law, lower level rules or Ministerial actions.

7. Integrate RIA with the policy-making process, beginning as early as possible

Regulators should see RIA insights as integral to policy decisions, rather than as an “add-on” requirement for external consumption.

8. Communicate the results

Policy makers are rarely analysts. Results of RIA must be communicated clearly with concrete implications and options explicitly identified. The use of a common format aids effective communication.

9. Involve the public extensively

Interest groups should be consulted widely and in a timely fashion. This is likely to mean a consultation process with a number of steps.

10. Apply RIA to existing as well as new regulation

RIA disciplines should also be applied to reviews of existing regulation

Understand how to best oversee SSE entities’ compliance with their stated societal objectives

Explore how to best oversee SSE entities compliance

Another way to evaluate if legal frameworks have reached their goals, is to consider whether SSE entities comply with their stated societal objectives. Oversight of SSE entities’ compliance likely depends on the extent to which the SSE is benefiting from any governmental subsidy, procurement priority, or regulatory forbearance. The more SSE entities enjoy benefits not ordinarily available to other economic actors, the more likely governments want to ensure that they are upholding the societal objectives that caused those benefits to accrue in the first place. Otherwise, there is a risk of other non-SSE entities misrepresenting themselves to access benefits that are intended for SSE actors.

The next question is which authorities should manage the oversight process? It is worth looking at how other economic activity is regulated or supervised in a specific country or region. In some countries, regulatory oversight and supervision is allocated according to the form of entity being overseen. For countries that have created specific SSE legal forms and that have a tradition of regulating by form (over function), the government authority that is providing a benefit may be best suited to taking on an oversight and supervisory role. For example, in Colombia, the Superintendence of the Solidarity Economy is the national entity that supervises cooperatives and other SSE entities. However, this might be challenging for countries that have either limited, or, if any, expressly defined legal forms of SSE entities. For example, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) supervises financial organisations, such as member owned mutual companies, that are authorised as deposit-taking institutions. For those countries, oversight and supervision may be dispersed across multiple government agencies and throughout various levels of government (state, provincial, municipal). Dispersed oversight can put additional pressure on government authorities to co-ordinate with each other, particularly to avoid parties engaging in regulatory triage by seeking the most lenient regulatory oversight.

Another point for examination is the role of the marketplace -both its private and public sector actors- in providing feedback to the SSE. Stakeholder consultations indicate that countries and regions are quite likely to benefit from building frameworks that encourage market responses to the behavior of SSE actors. This requires developing a framework that promotes transparency and public disclosure to stakeholders in the SSE. Some of this framework can piggyback on pre-existing mechanisms that foster transparency. But there are likely to be opportunities for this framework to be augmented with additional disclosure regimes developed.

Use evaluation to respond to evolutions in the SSE

Adjust to emerging needs

Countries could use legal assessments to adopt a dynamic approach to legal frameworks for the SSE. Like most legislation, legal frameworks for the SSE can become obsolete over time or need to be updated/adjusted to bring parity with new social or economic situations/evolutions. SSE entities inherently operate in dynamic markets and have ever-evolving needs and challenges. For example, SSE entities are expected to play a greater role to support the transition to more inclusive and greener economies and societies. As such, policy makers need to be prepared to adapt legal frameworks to new market developments and the evolving needs of stakeholders.

Political momentum needs to be sustained over time as challenges may emerge during the design and implementation of legal frameworks. Establishing a formal accountability mechanism such as the one developed by the Province of Québec in Canada can be a useful way to ensure the adaptability of legal frameworks over the long run while sustaining political momentum. Likewise, such mechanisms can help to link monitoring activities directly to policy actions that keep legal frameworks attuned to the real-world needs of social enterprises. The activities conducted as a result of such processes in Luxembourg testifies to the benefits of such approaches over time. Integrating such requirements helps to ensure that the necessary financial and human resources are available for future evaluations even if policy priorities have shifted towards new areas.

References

[6] European Commission (2021), Better Regulation Guidelines, https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/swd2021_305_en.pdf.

[4] European Commission (2017), EU Better Regulation Toolbox, https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/better-regulation-toolbox_1.pdf.

[8] OECD (2022), Designing Legal Frameworks for Social Enterprises: Practical Guidance for Policy Makers, Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/172b60b2-en.

[3] OECD (2018), OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264303072-en.

[1] OECD (2014), OECD Framework for Regulatory Policy Evaluation, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264214453-en.

[2] OECD (2012), Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance, https://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/49990817.pdf.

[5] Québec (2020), Application de la loi sur l’économie sociale. Rapport 2013-2020.

[7] Raquel Ortiz-Ledesma (2019), “Legal-political frameworks that promote Social and Solidarity Economy in Colombia and Mexico. A comparative cartography”, Deusto Journal of Human Rights, Vol. 4, https://djhr.revistas.deusto.es/article/view/1703/2128.