This chapter provides guidance as to if, why and when legal frameworks should be developed. It takes into account the maturity of the SSE ecosystem and how legal frameworks can support broader policy objectives such as fostering job creation or tackling informality. The chapter goes on to identify the benefits, boundaries and common characteristics of legal frameworks for SSE development with provides practical insights on how to identify the stakeholders needed to spearhead the legal framework process and distinguish the SSE from other business practices.

Policy Guide on Legal Frameworks for the Social and Solidarity Economy

1. Assess the need for and relevance of legal frameworks

Abstract

Why is this important?

Legal frameworks deeply influence the development of the social and solidarity economy (SSE) and can be helpful in a number of ways. They can help raise visibility and expansion of SSE entities, support them to enter new markets, access finance and gain public recognition such as in France and Spain. Just as they can help to unleash the potential of the SSE, legal frameworks can also create constraints that impede its development such as restricting the SSE to specific sectors, activities or types of business models. They can also stifle the development of the entire SSE ecosystem if they do not adequately meet the needs of SSE entities and do not consider the specific conditions of a given country or region.

Policy makers need to assess if, why and when it may be beneficial to adopt/revise legal frameworks for the SSE and the impact that legislation, or lack thereof, can have for its development. This assessment corresponds to the scoping phase. The need to develop legal frameworks for the SSE depends on local context, legal traditions and culture. This makes it important for policy makers to independently identify the right moment to develop them (OECD, 2022[1]).

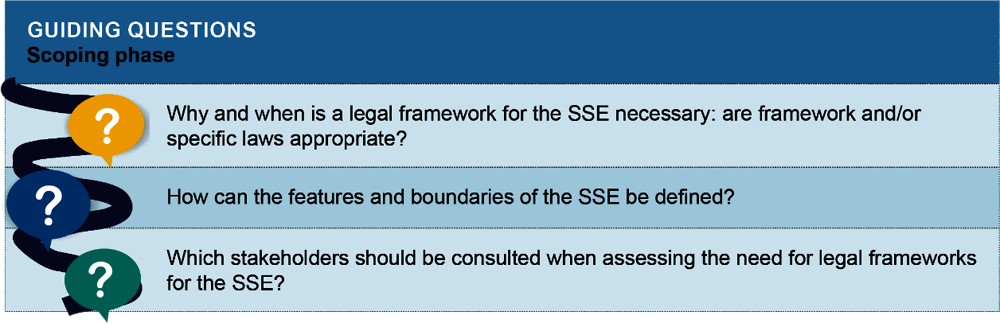

This section equips policy makers with concrete guidance to better identify why and when it could be appropriate and/or relevant to develop legal frameworks for the SSE. It also helps them identify stakeholders that need to be consulted and involved.

How can policy makers help?

Infographic 1.1. Guiding questions: Scoping phase

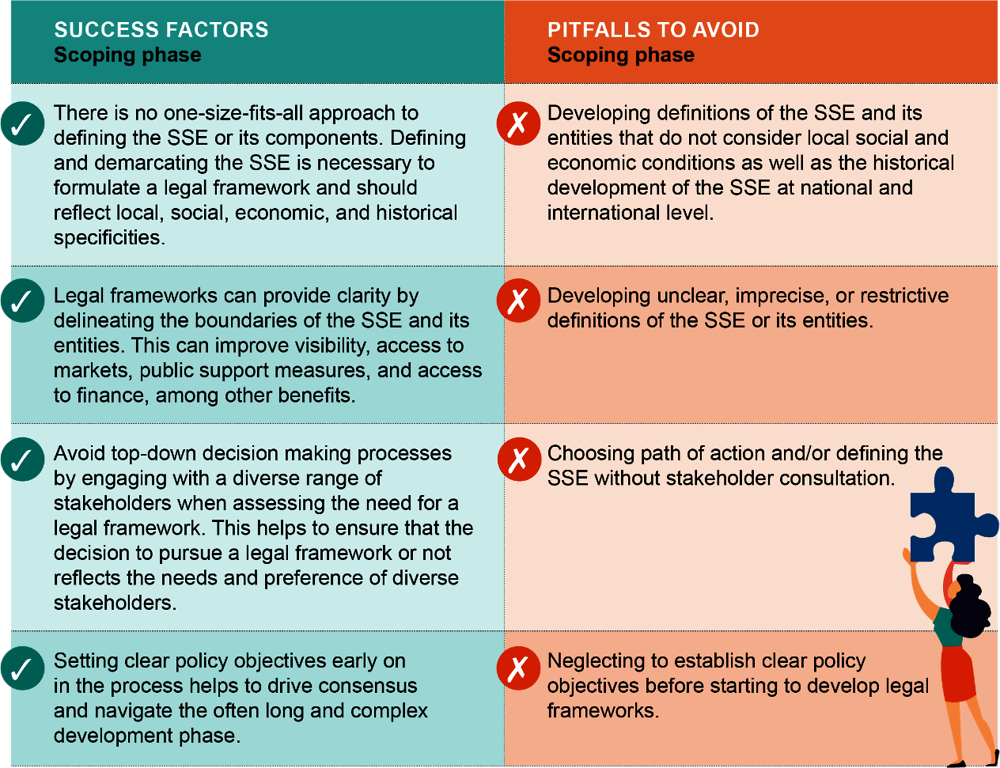

Across countries the following success factors and pitfalls to avoid can help to better capture, if why and when to develop legal frameworks for the SSE.

Infographic 1.2. Success factors and pitfalls to avoid: Scoping phase

Determine why and when legal frameworks for the SSE should be developed

Determining why and when legal frameworks are needed is influenced by many factors. In most countries, the structure and purpose of legal frameworks for the SSE are conditioned by local histories, institutional organisation and even global and local crises (OECD, 2022[1]). Legal frameworks also evolve differently in countries with centralised or quasi-federal and federal systems of government where both national and subnational levels can legislate (e.g., Brazil, Canada, Spain and the United States). In addition to those geographic and jurisdictional boundaries, there are other conditions that can affect the decision to adopt SSE legal frameworks or not. This includes the perceived role and function of the economy in addressing social issues, which in turn will influence the role that legislatures and courts play in establishing and responding to SSE initiatives. Several of these conditions may be more prevalent in some forms of administrative organisation than others.

Consider the maturity of the SSE ecosystem

The maturity of the SSE ecosystem affects the development of legal frameworks. The timing for the introduction of legal frameworks with respect to the level of development of the SSE ecosystem components matters. Existing legislation on the diverse components of the SSE can already be enabling and allow to harness its potential. Legislation that is introduced too early can be displeased by SSE entities.

It can also stifle innovation and constrain the development of the SSE. Countries can also decide that a legal framework is not always necessary to support the SSE.

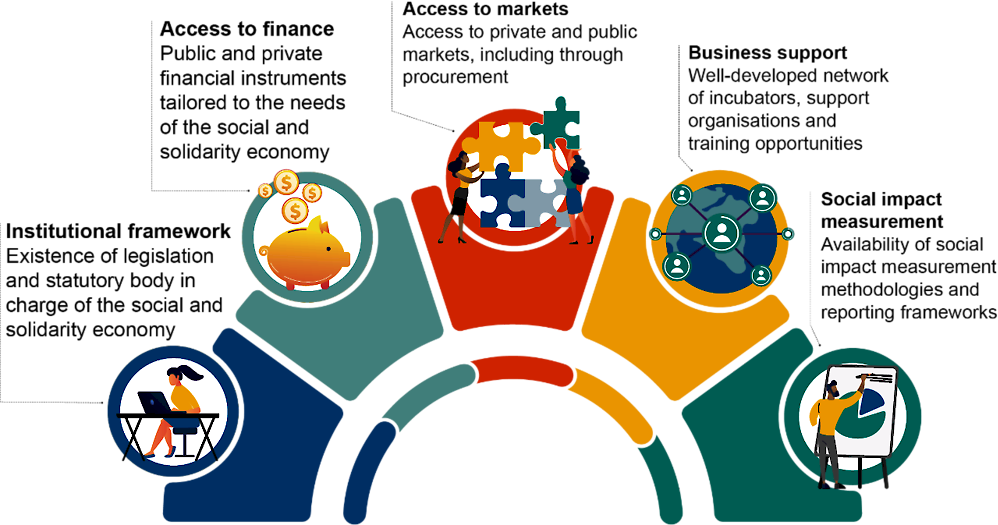

For example, the following elements, among others, might help to assess the maturity of the SSE ecosystem (OECD, n.d.[2]) :

Infographic 1.3. Indicative elements for mature SSE ecosystems

Source: Authors’ elaboration

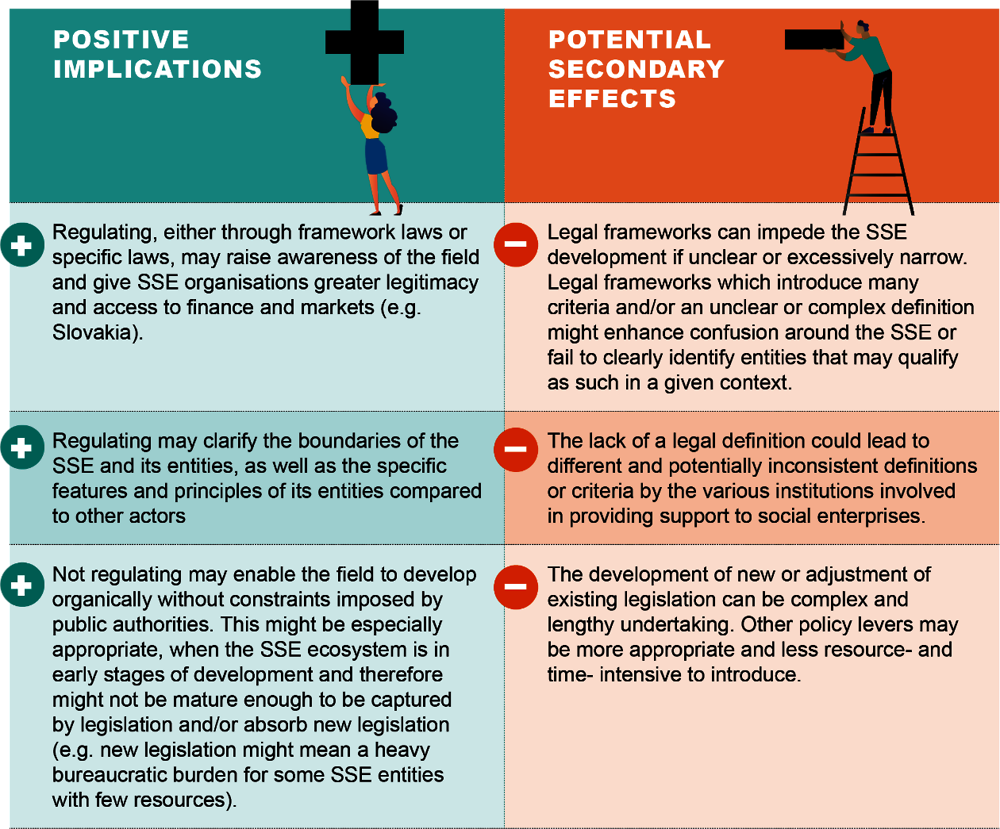

Depending on the maturity of the SSE ecosystem, positive implications and potential secondary effects of legislation weigh differently.

Infographic 1.4. Pros and cons of legal frameworks

Source: Authors’ elaboration

Establish clear policy objectives for legal frameworks

Legal frameworks for the SSE can support a wide range of policy objectives (Box 1.1). Countries and regions often introduce legal frameworks for the SSE to enhance the recognition and visibility of the SSE (France, Spain, Portugal, or at a subnational level in the province of Québec (Canada) (Almeida and Ferreira, 2021[3]). Additional policy objectives may include welfare state development, reducing informality, and creating jobs for specific groups.

Box 1.1. Examples of policy objectives underpinning legal frameworks for the SSE

Canada

In the province of Québec, the Social Economy Act (2013) aims to support the development of the social economy and to facilitate access to support measures. Furthermore, the Act defines the role of the Government and the Administration in the social economy (e.g. requirements for all ministers of the government to recognise the social economy as an integral part of the socioeconomic structure of Québec, functions of the Minister of Economy, the creation of social economy action plan and correlated five-yearly review).

France

The French Social and Solidarity Law of 2014 created a coherent policy regarding SSE entities to support their job creation potential. It created a common framework encompassing a range of organisations using diverse types of legal forms. Earlier, France also established the State Secretariat for the Social and Solidarity Economy in 2000 to help increase the visibility of the SSE and promote effective policy making.

Greece

The 2016 Law on Social and Solidarity Economy in Greece was adopted as an instrument for both the productive reconstruction of the Greek economy and for the socio-economic transformation to a more sustainable economy, after the financial crisis in 2008 and the financial austerity measures in the years after. The law adopts an expansive view of the SSE with the aim of promoting it across as many sectors of economic activity as possible. Additionally, it established the Special Secretary of the Social Economy and created a new legal status enabling entities of any legal form that meet specific criteria to register on the National Registry of the Social and Solidarity Economy.

Luxembourg

Luxembourg created a dedicated solidarity-based economy ministry in 2009 that subsequently evolved into the Ministry of Labour, Employment and Social and Solidarity Economy (MLESSE) in 2013. The 2016 Law on the Societal Impact Company (SIS) provides a definition of the SSE as business models that meet specific conditions related to economic activity, profit distribution, management and social purpose.

Improve clarity and recognition. Most countries often make the decision to develop legal frameworks by the need to enshrine a definition of the SSE in the law, including its purposes and principles, as well as to define ownership and governance rules related to SSE entities. For example, the 2015 Law of Social Economy (no. 219) of Romania was adopted because of the lack of a clear legal framework for the SSE, as well as to facilitate access to funding opportunities offered by the EU (Box 1.2) (European Economic and Social Committee, 2018[7]). In Spain, article 1 of the Law on the Social Economy (5/2011) refers to “the establishment of a legal framework common for all the entities that are part of the social economy, and the promotion measures applicable to them.” In Portugal, article 1 of the 2013 Social Economy Framework Law indicates that the law aims to establish “the general bases of the legal system of the social economy, as well as the measures to encourage its activity according to its own principles and purposes” (OECD, 2022[1]).

Box 1.2. Clarifying the SSE for better support allocation - Romania

In 2015, Romania introduced the Law 219/2015 on Social Economy with the aim to define the social economy, regulate different types of social enterprises and establish measures to promote and support it. The Law also regulates the principles of the social economy. Amended in 2022, the Law was simplified and provided for the certification with the status of social enterprises for legal entities active in the field of the social and solidarity economy (SSE). Different types of entities can be certified as social enterprises whatever their legal form may be. To be recognised as a social enterprise, legal entities that comply with the principles as determined by the Law can apply for a social enterprise certificate, awarded by the National Agency for Employment. Thus, different types of organisations can act as social enterprises while using various forms of incorporation. As of 2015, entities, established by the specific legislation regulating their legal form (such as associations, cooperatives, foundations, NGOs, etc.) can carry out social economy activities only if they are certified according to the Law no. 219/2015. By March 2021, 1 641 entities were certified as social enterprises. The highest number of social enterprises were certified in the years when financing through the European Social Fund was available (notably in 2021, 1849 entities were certified as Social Enterprises (SE)).

Moreover, the law introduces the status of “social insertion enterprise”, which is to be understood as a new category of work integration and social enterprises (WISEs), specifically regulated by this law that emphasises the instrumental use of the social economy towards the aim of social inclusion. Social enterprises that meet the additional criteria set out in the Law (e.g. at least 30% of employees belong to vulnerable groups) can apply for the status of social insertion enterprise that is certified by the award of the so-called “social label”. By March 2021, 45 Social Insertion Enterprises (SIE) were certified.

Furthermore, the Law sets out the establishment of a Single Register of Social Enterprises, to be administered by the National Agency for Employment, with the aim to overlook the situation and the evolution of the social economy sector at national level.

Enlarge the scope of the SSE. This often relates to the development of social enterprises, where a number of countries provided a more comprehensive framework that allows these entities to operate. In France, the 2014 Framework Law on the Social and Solidarity Economy introduced the concept of social enterprises. In India, legislation enacted in 2003 enabled a new generation of cooperatives known as producer companies (UNSRID, 2016[11]). This legislation refers to the Indian Companies Act of 1965 that was amended in 2003 and superseded by the Companies Act of 2013 that was amended several times since then. In Italy, social cooperatives were active since the early 1970s without a specific formal legal recognition (Fici, 2015[12]). They pushed for a legal framework that was adopted in 1991.

Scale up the SSE. Legal frameworks could also contribute to scaling up SSE entities and their entry into new sectors (Hiez, 2021[13]). By raising the visibility of SSE entities, legal frameworks can be an important lever to help them overcome challenges that they face when deciding to scale up (OECD/European Union, 2016[14]). For example, in Portugal, the SSE has significantly grown, in terms of its weight in wealth production and job creation, since the adoption of the Portuguese Social Economy Framework Law in 2013 (Monteiro, 2022[15]). Between 2013 and 2016 an increase of 17.3% in the number of entities and 14.6% in gross value added has been observed (Monteiro, 2022[15]).

Support welfare state development. Consultations with stakeholders in some countries (e.g. Denmark) with mature welfare states have revealed a lower need to develop strong SSE ecosystems. In other countries, legislation for the SSE targeted entities with a focus on serving broader communities and/or able to fill certain gaps in the provision of public services (e.g. India). Another example is the United States where the private sector, both for-profit and non-profit, traditionally plays an important role in the delivery of welfare services (Elizabeth T. Boris, 2010[16]; Plerhoples, 2022[17]). In 2010, researchers estimated that over half of the social services provided in the United States were channeled through public-private partnerships whereby government funding reached intended beneficiaries through not-for-profit service providers (Elizabeth T. Boris, 2010[16]). This shifting role of the federal government has contributed to the considerable growth of the non-profit sector in the United States. Additional research from the Johns Hopkins Center for Civil Society Studies found that the United States’ nonprofit sector was the third largest employer in the United States’ economy, overtaking even the manufacturing sector (Salamon and Newhouse, 2020[18]).

However, the emergence of SSE ecosystems is not always linked to the welfare state development. The SSE is also active in other fields (e.g., consumption, circular economy). SSE ecosystems can develop from the bottom-up even in countries where the welfare state is developed (e.g., France, the province of Québec, Canada), and not all of the SSE entities provide goods and services that substitute or complement public services. For example, cooperatives serve their members in a variety of services and production activities (OECD, 2022[1]). Additionally, the perceived role that corporations and other economic actors in the SSE play in the delivery of important social services and/or in advancing larger social goals is also important (Box 1.3). Similarly, the role and level of government authority in ensuring the delivery or advancement of these services and goals also needs to be ascertained during the scoping and development phases. As suggested below, at each juncture in the scoping and development phases of an SSE framework are questions of whether and where government action is appropriate. Accordingly, an understanding of the authority, culture and tradition is useful to help ground these discussions and determinations.

Foster job creation. Countries have also adopted legal frameworks for the SSE or its components to address poverty and income inequality or promote job creation and employment of disadvantaged groups (Brazil, Mexico) (Gaiger, 2015[19]). In Mexico, SSE entities like cooperatives provide an instrument for employment and self-employment, and in doing so, offer an alternative for traditional firms. In Korea, the Social Enterprise Promotion Act (2007) aimed to stimulate work integration and reduce unemployment (ILO, 2017[20]). In Finland, the Act on Social Enterprises (2003, last amended in 2019) has strongly focused on creating employment opportunities by requiring that 30% of social enterprise employees have a disability or experience long-term unemployment. In Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Germany, Romania, Slovenia and Spain, statuses recognising WISEs specifically have been introduced to facilitate work integration of people with disability (European Commission, 2020[21]) In 2022, Poland passed the Act on Social Economy regulating the social enterprise status. This status is available to several legal forms, provided they operate for the purpose of reintegration (persons at risk of social exclusion will account for 30% of the employed in total) or for providing social services to the local community.

Tackle informality. The SSE has been identified as a vehicle that could help to tackle labour informality, given its ability to reach disadvantaged groups, facilitate access to training and support the formalisation of work through its entities, such as cooperatives (ILO, 2018[22]; OECD, 2022[23]). In India, for example, informal entities remain widespread, in particular in rural areas. Internal migration from rural to urban areas has driven the emergence of newer forms of informality as well as the need for novel forms of co-operation to ensure the provision of basic social and economic needs (Box 1.4). In countries such as Brazil, these trends have led to the emergence of mutual help and economic co-operation in these urban areas (Gaiger, 2017[24]). Conducive and tailored legal frameworks can help unleash the SSE’s full potential for tackling informality and its impacts and provide solutions to support the transition to formal work in many economic sectors. In addition to that, novel multidimensional strategies that integrate a range of policies are needed to address informality holistically (OECD, 2022[23]).

Box 1.3. Regulation of the non-profit sector in the United States

Regulation of the non-profit sector in the United States is shared by the federal and state governments. The primary agency charged with federal oversight is the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), which generally focuses on whether organisations meet tax-exempt requirements and comply with federal laws, including those governing the use of funds intended for a charitable purpose. The IRS makes determinations about whether organisations will be granted federal tax-exempt status. Depending on the state jurisdiction where not-for-profit organisations are incorporated, these federal tax-exempt determinations by the IRS also may confer comparable or similar tax-exempt status under state and local laws. The IRS also receives annual reporting of financial data from tax-exempt organisations.

The IRS is not the only federal agency, however, to oversee not-for-profit organisations. Other federal agencies also provide specialised oversight in their particular areas of expertise, such as the Federal Trade Commission, which among other things regulates non-profits for unfair or deceptive acts or practices (such as deceptive fundraising practices), and the Department of Justice, which among other competencies has enforcement authority over non-profit organisations engaged in economic crime (such as fraud and foreign corrupt practices, among others).

At the state level, the state attorney general is typically responsible for regulating the not-for-profit organisations incorporated in her/his state.

Source: Internal Revenue Code Section 501I (3); see generally, explanation of requirements to receive tax exemptions a non-profit charitable organisation (https://www.irs.gov/charities-non-profits/charitable-organizations/exemption-requirements-501c3-organizations).

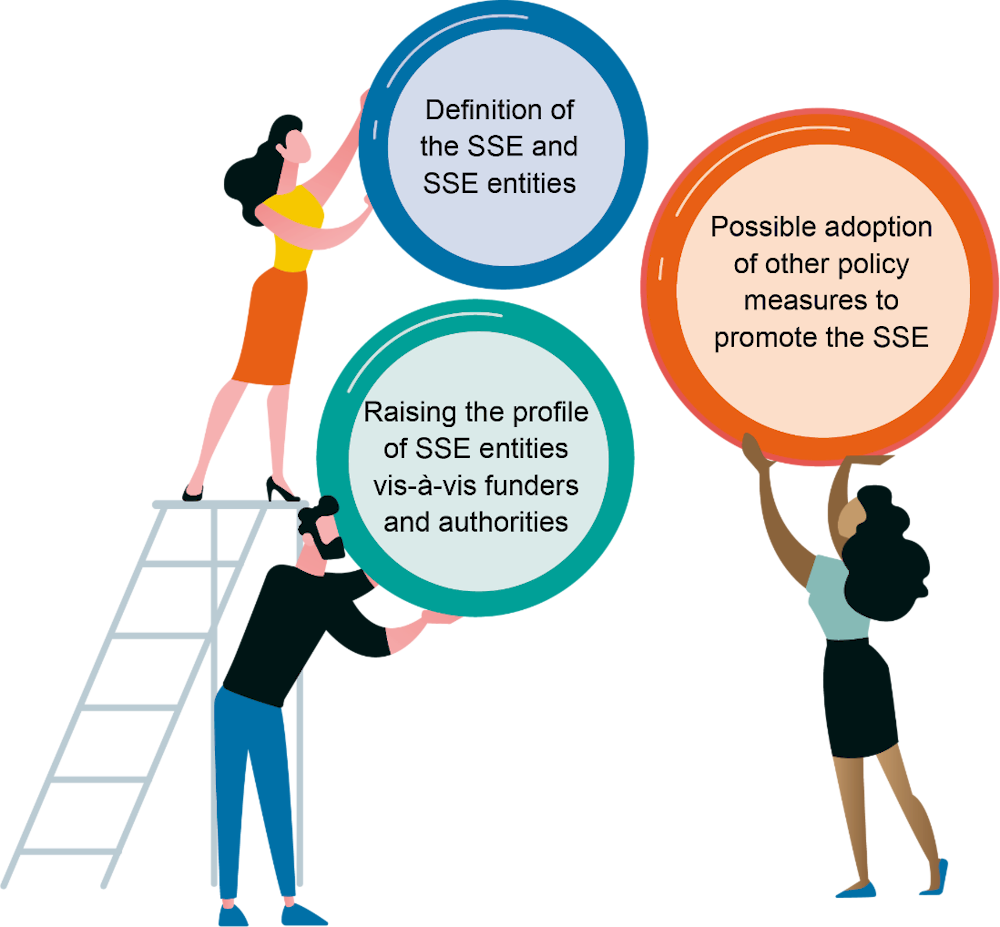

Identify the benefits of legal frameworks

The adoption of legal frameworks usually brings three major benefits for SSE development: i) definition of the SSE and SSE entities; ii) possible adoption of other policy measures to promote and support the SSE; and iii) raising its profile vis-à-vis funders and authorities (See infographic 1.5).

Infographic 1.5. Potential benefits of legal frameworks for the social and solidarity economy

Source: Authors’ elaboration

Definition of the SSE and SSE entities. Legal frameworks are approved by parliaments. As such, they carry more authority than other policy instruments such as strategies and action plans. On the other hand, legal frameworks cannot be easily revised in the event of political change, as this requires a formal process. In most cases, they identify and recognise the SSE as a field (for example through framework laws) and/or the main features, mission governance rules and activities of SSE entities (through specific laws).

Possible adoption of other policy levers to promote the SSE. Legal frameworks facilitate the adoption of differentiated legal regimes and a wide range of support measures for SSE entities: tax and fiscal arrangements; tailored access to public procurement; access to suitable and targeted public funding schemes; reduction of incorporation and registration costs; specific incentives to encourage employment of specific groups (e.g. disadvantaged individuals or persons with disabilities). In addition, entities also know what is legally required from them to qualify for public support.

Raising the profile of SSE entities vis-à-vis funders and authorities. Legal frameworks provide an opportunity to raise the profile of SSE entities towards other stakeholders. Clear labelling helps identify the potential benefits of investing in and/or collaborating with SSE entities while supporting their social mission. SSE entities are built for and prioritise their social/societal mission over profit-maximisation for personal enrichment, and this is secured in their legal form or statutes through various mechanisms (e.g. limited profit distribution, non-distributable profit reserves, asset-locks, etc.).

Box 1.4. The evolving policy landscape for cooperatives in India

The cooperative movement in India traces its origin to the early 1900s. It started in the agriculture and related sectors as a mechanism for pooling people’s limited resources aiming to access the benefits of the economies of scale. Today, cooperatives still play a major role in India’s economy with a prominent presence in sectors such as housing, dairy, savings and credit. There are more than 290 million members in 854 000 cooperatives, accounting for 13.3% of direct employment and 10.91% of self-employment in India. Cooperatives are present throughout the country, though with notable differences among jurisdictions. For example, while in the State of Maharashtra there are more than 205 000 cooperatives registered, only 81 organisations are present in the Union Territory of Lakshadweep.

In 2021, cooperative affairs were transferred from the Ministry of Agriculture to the newly established Ministry of Cooperation. This ministry provides a separate administrative and policy framework to oversee the cooperative movement in the country. Main activities of the Ministry include facilitating the development of Multi-State Cooperative Societies and ease of business for cooperatives. Additionally, a new National Cooperation Policy is being formulated to fulfil the mandate given to the Ministry of Cooperation. The new policy aims to create an appropriate policy, legal and institutional framework to help cooperatives unleash their potential, among other objectives. The latest development concerning the cooperative sector is the submission of a bill in December 2022 by the Ministry of Cooperation to amend the Multi-State Cooperative Societies Act (2002). The amendment seeks to strengthen the governance, improve the monitoring mechanism and ensure the financial discipline of Multi-State Cooperatives Societies.

Identify stakeholders to be consulted on the need for legal frameworks

The need for legal frameworks can be spearheaded by public authorities or emerge through bottom-up processes led by grassroots movements. Stakeholder consultations are an effective way for policy makers to gauge the need and support for legal frameworks for the SSE. It is preferable to include SSE networks, umbrella organisations and federations in decisions to pursue legal frameworks for the SSE. Doing so helps to better capture the realities and needs on the ground by enriching policy makers understanding of the SSE with stakeholder perspectives and aligning SSE needs with strategic objectives of policy makers. For example, Denmark created a specific National Committee in order to prepare the Act on Registered Social Enterprises of 2014. Slovakia held a two-year long consultation process and collected input from academics, social entrepreneurs, (local) governments, etc. before adopting the Act on Social Economy and Social Enterprises in 2018 and defining the scope of SSE in the country.

Other countries have institutionalised the participation of civil society organisations in their legislative process. They have done so through formal mechanisms such as official participation and consultation periods, through informal mechanisms or through general customs (advocating or lobbying by civil organisations or federations). For example, the implementation of the SSE in the Province of Québec (Canada) has shown that strong institutional participation by civil society groups such as trade unions, employer organisations, and the public can improve SSE-related policy making (Mendell, 2008[30]). The Québec 2013 Social Economy Act recognises privileged interlocutors, namely the Chantier de l’économie sociale and the Conseil québécois de la coopération et de la mutualité,and establishes a partners’ table on the social economy to be consulted on social economy affairs. In France, the 2014 Framework Law on the Social and Solidarity Economy established biennial stakeholder consultations on the SSE, helping to ensure regular bottom-up feedback (OECD, 2022[1]). Additionally, the National Council of the Social Economy, a policy shaping body, brings together diverse stakeholders such as practitioners, experts and academics to discuss the SSE in France (OECD, n.d.[31]).

In certain instances, consultations have made it clear that stakeholders prefer that policy makers do not pursue certain legal options. This is best highlighted by the case of Ireland (Box 1.5) in which stakeholders preferred not to establish a specific legal form for social enterprises.

Box 1.5. Ireland: Exploring the possibility to adopt a dedicated legal form for social enterprises

In July 2019, the Irish Government’s Department of Rural and Community Development introduced the National Social Enterprise Policy 2019-2022, which includes a definition of social enterprises but also acknowledges that further research on legal forms for social enterprises is needed. To this end, Rethink Ireland and the Department of Rural and Community Development commissioned a research study that consulted policy makers, social enterprises, network organisations and academics to gain insights on the barriers experienced by social enterprises as they relate to legal form, as well as the benefits and necessity of creating a dedicated legal form for social enterprises. Ultimately, the study did not recognise the need for a distinct legal form for the following reasons.

Many of the barriers identified were less to do with legal form, and more to do with compliance, access to resources, governance, visibility and recognition of social enterprises. The majority of the Irish social enterprises surveyed agreed that a dedicated legal form would resolve many issues and could facilitate the future development of the SSE. However, the majority (59%) of respondents also believed that their current legal form met their current and future needs. There was also a view that some of the identified barriers could be alleviated by greater use of existing legal forms, such as those of a company, an association, a cooperative, or hybrid structures reflecting both for-profit and not-for-profit components of a social enterprise. Moreover, respondents held very different views regarding the features that a dedicated form would comprise.

Additionally, issues relating to clarity about social enterprises and simplifying governance systems would remain to be addressed, irrespective of whether or not a specific legal form was adopted. Finally, the task of establishing a relatively permanent legal form would imply a significant and lengthy undertaking. Considering all this, the study recommended utilising other policy levers to support social enterprises before seeking to adopt a dedicated legal form based on the development of the SSE.

Determine the boundaries and common characteristics of the SSE

Define the features and boundaries of the SSE

The SSE and its related concepts include a range of diverse entities. It merges two notions: the social economy and the solidarity economy. The social economy encompasses associations, cooperatives, foundations, mutual societies and social enterprises, while the solidarity economy refers to more spontaneous, grassroots-level initiatives (OECD, 2022[23]). There are many types of SSE entities, with various social objectives, business models and legal forms that have emerged worldwide, which can make it challenging for policy makers, practitioners and academics to develop a common definition or clear boundaries for the SSE.

Policy makers need to develop a clear understanding of the SSE (or, in certain countries, the social economy or third sector) and its respective entities. The SSE shares common underlying principles and practices. SSE entities pursue societal objectives, often at the local level, in a manner that prioritises people over the pursuit of profit for personal enrichment. They also implement distinct ownership and decision-making practices. Additionally, collaboration and co-operation are central values for SSE entities that enable them to partner with other SSE entities, public and private sector actors to achieve social objectives and access resources (OECD, Forthcoming[34]). This can help to develop coherent policy objectives or co-ordinate efforts related to the SSE. It can also enhance public engagement with the SSE and ultimately accelerate the development of the overall SSE.

Adopt a pragmatic approach to demarcate the SSE from other practices

Multiple approaches can be used to defining and demarcating the SSE. Such approaches have evolved at different moments and were conditioned by distinct cultural, economic and social conditions, as well as the needs and viewpoints of stakeholder groups, including academics, practitioners and policy makers (Galera and Chiomento, 2022[35]). They have typically described the SSE or related concepts as a set of initiatives that are not public or not-for-profit and utilise alternative business models to provide goods and services while achieving societal objectives. Similarly, private-sector business practices that promote societal goals can sometimes make it difficult to differentiate between SSE actors and initiatives and the rest of the economy (Box 1.6). Academics, policy makers and stakeholder groups have sought to define the SSE and related concepts for distinct reasons, which has contributed to varying definitions of the SSE, the social economy, the third sector, and the entities that comprise them (OECD, Forthcoming[34]).

By adopting a pragmatic approach, policy makers can distinguish SSE entities from others, often to implement targeted policy measures. As countries have adopted formal definitions and developed legal frameworks for the SSE and its entities, they have adapted their definition of the SSE to reflect their historical, economic and social context. Academic approaches to defining the SSE typically aim to clarify their area of study and identify the motivations of SSE actors. They can help inform efforts by policy makers seeking to demarcate SSE entities from other entities and practices that might seem similar.

Box 1.6. Distinguishing the SSE from other business practices

Conventional enterprises have adopted a range of business practices designed to make their activities more socially and/or environmentally friendly. Generally speaking, these efforts promote social and environmental considerations in a number of ways, such as by addressing negative externalities created by business activity or actively promoting certain social or environmental goals. Importantly, using practices does not enable businesses to qualify as part of the SSE as they retain the pursuit of profit as their primary motive and may not limit profit distribution or concentrated decision-making power.

These practices include approaches such as Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), which originally emerged in the mid-20th century and refers to instances where businesses uphold social and environmental objectives that are not immediately related to its fundamental economic performance or legal responsibilities. This can mean both actively engaging in socially beneficial practices such as philanthropy as well as avoiding or offsetting social or environmental harm.

This notion of responsibility beyond profit maximisation and shareholder returns encapsulated by CSR has served as the foundation of other concepts such as stakeholder theory, corporate citizenship, and the principles of Responsible Business Conduct (RBC). RBC encompasses principles and standards that minimise the negative effects business activities while also promoting sustainable development. This practice integrates environmental, human rights and social considerations into the decision-making process of firms and is particularly important for multi-national enterprises that operate across numerous different national legal, social and environmental contexts.

Environment, Social and Governance (ESG) Criteria assess enterprise performance with respect to the environment, climate change, resource management, human rights, labour practices, product safety, transparency and accountability. This enables investors and consumers to identify more sustainable, socially responsible firms. There are multiple approaches to ESG reporting such as the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, which provides companies with guidance and standards of due diligence that help them to identify and avoid potential negative effects of their activities.

Social purpose businesses are conventional enterprises that also promote social and/or environmental objectives. This concept goes beyond traditional CSR practices by integrating social and environmental objectives into the core of an enterprise’s business practices. This approach has been adopted by notable firms such as BlackRock, which actively seeks to drive social and environmental benefits with its investments while still prioritising profits.

References

[6] Adam, S. (2019), “Legal provisions for Social and Solidarity Economy Actors. The case of Law 4430/2016 in Greece”, International Journal of Cooperative Law, Vol. 97/103.

[8] ADV Foundation (2022), Registrul național de evidență a întreprinderilor sociale – date la zi!, https://alaturidevoi.ro/registrul-national-de-evidenta-a-intreprinderilor-sociale-date-la-zi/.

[9] ADV Foundation (2021), Barometer of the Access to Financing of Social Economy Enterprises from Romania, https://alaturidevoi.ro/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/the-barometer-of-the-access-to-financing-of-social-economy-enterprises-from-romania.pdf.

[3] Almeida and Ferreira (2021), Social Enterprise in Portugal. Concept, Contexts and Models.

[36] Eilbirt, H. and R. Parket (1973), “The practice of business: the current status of corporate social responsibility”, Business Horizons, Vol. 16/4, pp. 5-14.

[16] Elizabeth T. Boris, E. (2010), Human Service Nonprofits and Government Collaboration: Findings from the 2010 National Survey of Nonprofit Government Contracting and Grants, https://www.councilofnonprofits.org/sites/default/files/documents/Full%20Report.pdf.

[21] European Commission (2020), Social enterprises and their ecosystems in Europe. Comparative synthesis report, Publications Office of the European Union, https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=738&langId=en&pubId=8274&furtherPubs=yes.

[10] European Commission (2019), Social Enterprises and Their Ecosystems in Europe: Romania, https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=20959&langId=en.

[7] European Economic and Social Committee (2018), Best practices in public policies regarding the European Social Economy post the economic crisis, https://www.eesc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/files/qe-04-18-002-en-n.pdf.

[12] Fici, A. (2015), Recognition and legal Forms of Social Enterprise in Europe: A Critical Analysis from a Comparative Law Perspective., https://euricse.eu/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/WP-82_15_Fici2.pdf.

[24] Gaiger, L. (2017), The Solidarity Economy in South and Northern America: Converging Experiences, https://doi.org/10.1590/1981-3821201700030002.

[19] Gaiger, L. (2015), The legal framework for Solidarity Economic Enterprises in Brazil: backgrounds and perspectives, https://emes.net/content/uploads/publications/the-legal-framework-for-solidarity-economic-enterprises-in-brazil-backgrounds-and-perspectives/ESCP-5EMES-10_Lega_framework_solidarity_Economic_Entreprises_Brazil_Gaiger.pdf.

[35] Galera, G. and S. Chiomento (2022), “L’impresa sociale: dai concetti teorici all’applicazione a livello di policy”, Impresa Sociale, Vol. 1/2022, https://rivistaimpresasociale.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/magazine_article/attachment/285/ImpresaSociale-2022-01-galera-chiomento.pdf.

[4] Gidron, B. and A. Domaradzka (eds.) (2021), The Social and Solidarity Economy in France Faced with the Challenges of Social Entrepreneurship, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-68295-8_7.

[26] Government of India (2021), Strengthening the Cooperative Movement, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleseDetailm.aspx?PRID=1776506.

[13] Hiez, D. (2021), Guide to the writing of law for the Social and Solidarity Economy, https://orbilu.uni.lu/bitstream/10993/50283/1/Guide%20ESS.pdf.

[25] ICA (2021), Mapping: key figures. National Report: India.

[27] ICA (2020), Legal Framework Analysis within the ICA-EU Partnership. National Report - India, https://coops4dev.coop/sites/default/files/2021-06/India%20Legal%20Framework%20Analysis%20National%20Report.pdf.

[22] ILO (2018), Women and men in the informal economy: a statistical picture (third edition), https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/documents/publication/wcms_626831.pdf.

[20] ILO (2017), Public policies for the social and solidarity economy: towards a favourable environment. The case of the Republic of Korea.

[32] Lalor, T. and G. Doyle (2021), Research on Legal Form for Social Enterprises, https://rethinkireland.ie/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Research-on-Legal-Form-for-Social-Enterprises.pdf.

[30] Mendell, M. (2008), The Social Economy in Quebec. Lessons and Challenges for Internationalizing Co-operation.

[28] Ministry of Cooperation (2022), List of Cooperative Societies / Banks registered under MSCS Act w.e.f. 1986 onwards, https://mscs.dac.gov.in/Proposals/ALL_REG_MSCS.pdf.

[29] Ministry of Cooperation (2022), Union Home and Cooperation Minister Announces Constitution of National Level Committee for Drafting the National Cooperation Policy Document, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1857025#:~:text=The%20existing%20National%20Policy%20on,reliant%20and%20democratically%20managed%20institutions.

[15] Monteiro, A. (2022), The Social Economy in Portugal: legal regime and socio-economic characterization.

[1] OECD (2022), “Legal frameworks for the social and solidarity economy: OECD Global Action “Promoting Social and Solidarity Economy Ecosystems””, OECD Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED) Papers, No. 2022/04, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/480a47fd-en.

[23] OECD (2022), Recommendation of the Council on the Social and Solidarity Economy and Social Innovation.

[37] OECD (2020), OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2020 Issue 1, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/0d1d1e2e-en.

[39] OECD (2018), OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct.

[40] OECD (2014), OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises. Responsible Business Conduct Matters.

[2] OECD (n.d.), Better Entrepreneurship Policy Tool, https://betterentrepreneurship.eu/.

[31] OECD (n.d.), OECD Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED) Papers, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/20794797.

[34] OECD (Forthcoming), Untangling the Complexity: A Conceptual Overview to the Social and Solidarity Economy.

[14] OECD/European Union (2016), Policy Brief on Scaling the Impact of Social Enterprises, https://doi.org/10.2767/45737.

[17] Plerhoples, A. (2022), Purpose Driven Companies in the United States,, https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/2440.

[41] Pollman, E. and R. Thompson (eds.) (2021), The shareholder-stakeholder alliance.

[38] Porter, M. and M. Kramer (2011), Creating Shared Value: How to reinvent capitalism -- and unleash a wave of innovation and growth.

[18] Salamon, L. and C. Newhouse (2020), The 2020 Nonprofit Employment Report, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Center for Civil Society Studies, https://baypath.s3.amazonaws.com/files/resources/2020-nonprofit-employment-report-final-6-2020.pdf.

[5] Sarracino, F. and C. Peroni (2015), Assessing the Social and Solidarity Economy in Luxembourg, EMES Conference Selected Papers, https://emes.net/publications/conference-papers/5th-emes-conference-selected-papers/assessing-the-social-and-solidarity-economy-in-luxembourg/.

[33] Thomson Reuters Foundation and Mason Hayes & Curran LLP (2020), Social Enterprises in Ireland. Legal Structures Guide, https://www.socent.ie/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Social-Enterprises-In-Ireland-TrustLaw-Guide-November-2020.pdf.

[11] UNSRID (2016), Promoting Social and Solidarity Economy Through Public Policy, https://cdn.unrisd.org/assets/legacy-files/301-info-files/7E583F050CE1D2A4C125804F0033363E/Flagship2016_Ch4.pdf.