This chapter focuses on Eastern Partner countries’ progress in SME innovation and business support since the 2020 assessment according to three dimensions: business development services, SME-specific innovation policy, and green economy policy for SMEs. Analysing business development services encompasses governmental provision of a wide range of support services as well as initiatives to stimulate private business support services, and the existence of such services to support SMEs’ digital transformation more specifically. In addition, the dimension on SME innovation policy analyses the policy framework, and government institutional and financial support for innovative SMEs. The last dimension examines the framework for SME-specific environmental policies as well as incentives and instruments for SMEs to green their activities. Each of these three dimensions contains a dedicated set of policy recommendations for EaP countries to build on in the upcoming years.

SME Policy Index: Eastern Partner Countries 2024

9. Pillar E – Innovation and Business Support

Abstract

Introduction

Productivity growth is a key driver of economic growth and convergence. It is also the channel through which countries generate the resources needed to lift standards of living and reduce inequalities. Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are generally less productive than large companies, although the scope of the difference varies across sectors and countries. Productivity gaps between firms of different sizes are particularly evident in manufacturing, where production tends to be more capital-intensive and larger firms can exploit increasing returns to scale. A recent analysis found that labour productivity of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises in manufacturing stood at 37%, 62% and 75%, respectively, of that of large companies. Productivity gaps are less stark in the services sector, and narrowest in retail trade, which tends to display low labour productivity overall (Marchese, Giuliani and Carlos, n.d.[1]; OECD, 2021[2]).

Improved productivity is also a matter of resource efficiency. Natural resources underpin our economy by providing essential raw materials, water, and other commodities. Besides environmental benefits, their efficient use brings gains from an economic and trade perspective. A development pattern that depletes the economy’s natural asset base without providing secure, long-term substitutes for the goods and services that it provides, is unlikely to be sustainable and entails risks to future growth (OECD, 2015[3]).

At the macro level, determinants of productivity include framework conditions, such as the quality of the competitive environment; the efficiency of the judiciary; financial market development; and the extent to which economic institutions facilitate access to inputs and the allocation of capital and labour to their best uses. At the firm level, drivers of productivity performance relate to managerial and workforce skills and the adoption rate of innovations. SMEs can struggle in this regard, considering that they often face difficulties in obtaining information, offering training to their employees, accessing advanced consulting services and adopting innovative processes.

This is particularly relevant when it comes to the digital transition, an area where SMEs lag behind larger firms, particularly in Eastern Partner (EaP) countries (OECD, 2021[4]). Most SMEs are not fully aware of the potential benefits in productivity and competitiveness, cannot clearly identify their needs, or do not have sufficient capabilities or financial resources to access and effectively use digital instruments. The SME digital gap compared to larger companies slows productivity growth and increases inequalities among people, firms and locations, and the COVID-19 pandemic has increased the need for businesses to operate digitally, making this issue a policy priority for governments (OECD, 2021[5]).

Innovation is also at the heart of the transition to net zero and a cleaner global environment (OECD, 2023[6]). Improved processes and new technologies can make manufacturing more sustainable, reduce pollution, increase resource efficiency, develop products and services with lower carbon footprints and yield other substantial environmental improvements.

This pillar brings together three dimensions of the assessment, which look closely at the policies in place to foster a productive, innovative and green SME sector: 1) business development services; 2) innovation policy for SMEs; and 3) green economy policy for SMEs. As presented in Table 9.1, the regional average scores for the dimensions in Pillar E do not exceed 3.5, which implies ample room for improving policy frameworks in these areas. Nevertheless, the trend observed using comparable scoring methodologies shows (moderate) progress in all dimensions since the previous SBA assessment.

Table 9.1. Pillar E, country scores by dimension and sub-dimension, 2024

|

Armenia |

Azerbaijan |

Georgia |

Moldova |

Ukraine |

EaP average |

EaP average 2024 (CM) |

EaP average 2020 (CM) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Business development services |

3.06 |

3.33 |

4.22 |

3.69 |

3.57 |

3.57 |

3.74 |

3.61 |

|

Services provided by government |

3.38 |

3.96 |

4.51 |

4.17 |

4.08 |

4.02 |

3.92 |

3.99 |

|

Initiatives to stimulate private BDS |

3.14 |

3.19 |

4.10 |

3.72 |

3.20 |

3.47 |

3.57 |

3.22 |

|

BDS for SME digital transformation |

3.11 |

2.91 |

3.59 |

3.51 |

3.53 |

3.33 |

- |

- |

|

Outcome-oriented indicators |

1.40 |

1.80 |

4.20 |

1.80 |

3.00 |

2.44 |

- |

- |

|

Innovation policy for SMEs |

3.00 |

2.85 |

3.44 |

3.11 |

3.03 |

3.09 |

2.47 |

2.31 |

|

Policy framework for innovation |

3.06 |

3.11 |

3.50 |

2.99 |

2.72 |

3.07 |

3.06 |

2.97 |

|

Government institutional support |

2.77 |

2.88 |

3.26 |

3.33 |

3.11 |

3.07 |

2.73 |

3.13 |

|

Government financial support |

3.62 |

2.82 |

3.56 |

3.28 |

2.67 |

3.19 |

3.51 |

2.47 |

|

Outcome-oriented indicators |

1.80 |

1.80 |

3.40 |

2.60 |

5.00 |

2.92 |

- |

- |

|

Green economy policies for SMEs |

2.51 |

2.54 |

3.08 |

3.38 |

2.56 |

2.81 |

2.99 |

2.59 |

|

Environmental policies |

2.89 |

2.82 |

3.57 |

3.70 |

2.44 |

3.08 |

3.16 |

3.00 |

|

Incentives and instruments |

2.54 |

2.40 |

3.14 |

3.60 |

2.92 |

2.92 |

2.87 |

2.32 |

|

Outcome-oriented indicators |

1.00 |

2.33 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.27 |

- |

- |

Note: BDS: business development services. CM: comparable. See the “Policy framework, structure of the report and assessment process” chapter and Annex A for information on the assessment methodology.

Business Development Services

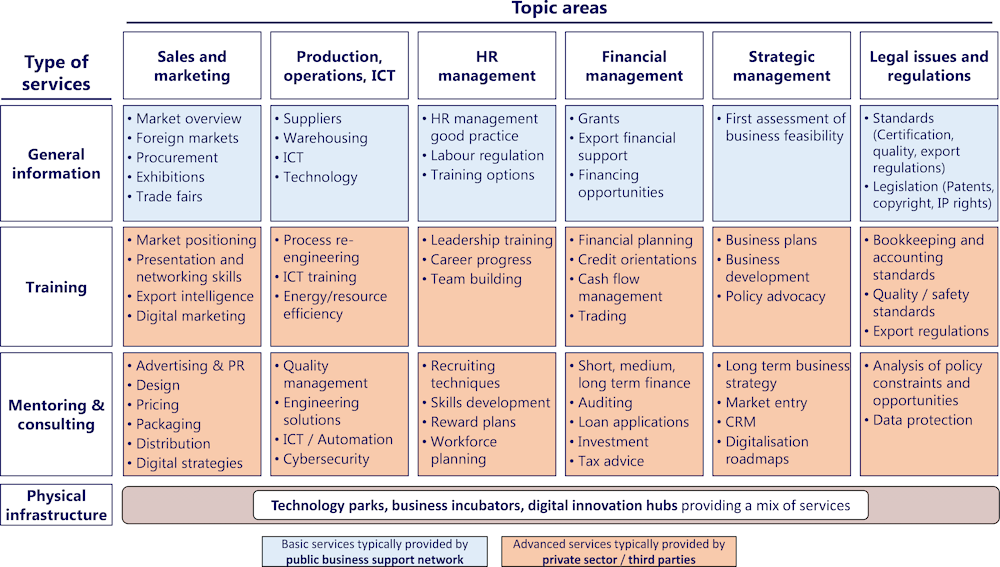

Business development services (BDS) enhance the performance of individual businesses, allowing them to compete more effectively, operate more efficiently and become more profitable. Such services include information provision, training, consulting and mentoring on a wide range of topics, from sales and marketing to strategic management and legal issues (Figure 9.1). BDS should also evolve to respond to changing conditions in the business environment, technological progress and market trends, as evidenced, for instance, by the current wave of initiatives to support business digitalisation, such as the European Digital Innovation Hubs (Box 9.1).

Entrepreneurs with limited skills and knowledge to start and operate a business can benefit significantly from BDS, which save time and resources, help to evaluate potential business opportunities, and encourage SMEs to enter and explore new markets. Ultimately, BDS allow firms to focus on their core competencies while outsourcing non-core tasks to specialised advisors and reducing search costs for relevant information. More advanced BDS can also provide firms with the knowledge and resources required to innovate, grow and internationalise.

Figure 9.1. Business development services: Topic areas and types of services

Note: ICT: information and communication technologies; HR: human resources; IP: intellectual property; PR: public relations; CRM: customer relationship management.

Source: based on (OECD, 2017[7]).

BDS markets generally suffer from information-related failures regarding both the demand and supply of BDS, which disproportionately affect SMEs:

On the demand side, SMEs often have minimal ex ante knowledge about the effectiveness and potential impact on firm performance, which limits their expenditure on such services. They also lack information on the availability of BDS and the type of support required, which may vary depending on the firms’ type of activity and its stage of development. Finally, SMEs may simply be lacking financial resources to access BDS.

On the supply side, BDS providers often lack adequate and up-to-date information on the SME training needs required to provide tailored and timely business support. Private BDS providers may also lack the needed skills and face uncertainty regarding compensation from SMEs and would therefore prefer working with larger companies due to more substantial contracts, longer engagement and less risky payments.

Identifying market failures – which are typically the result of information asymmetries, a lack of trust between parties and financial gaps – should be a first step in designing sound policy frameworks regarding the provision of BDS to SMEs. Governments could intervene to stimulate the emergence of vibrant markets for BDS but should avoid crowding out private initiatives. Policy interventions are then required to ensure that SMEs are informed about the benefits and availability of support services (e.g. information campaigns, awareness raising) and, if needed, incentivised (e.g. co-financing mechanisms) to increase access. Financial support should nevertheless be temporary, as such incentives, if made permanent, are vulnerable to rent-seeking. This approach would thus encourage the development of a sustainable market in BDS provision, shaped by demand, and based on a clear understanding of the company’s needs and expectations.

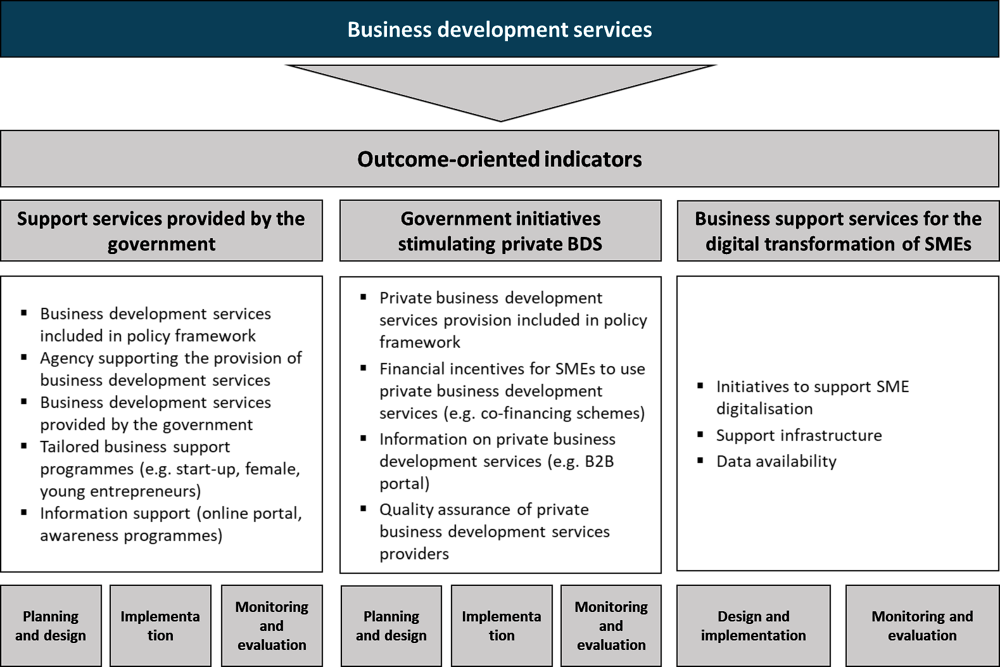

Assessment framework

This dimension considers the availability, accessibility and effective implementation of government initiatives to design and deliver the support needed to stimulate the supply and demand for targeted BDS for SMEs. It also assesses the role of governments in identifying and addressing market failures in BDS markets through public policy tools, such as government-led business support infrastructure and initiatives to promote the development of private BDS providers.

Two important methodological changes have been introduced in this dimension since the previous SBA assessment: i) given the increasing relevance of digital technologies to support business growth and productivity, a new sub-dimension looks at the overall presence of business support services for the digital transformation of SMEs; and ii) the analysis also considers countries’ ability to regularly collect quantitative information to monitor the impact of policies on actual SME performance (“outcome-oriented indicators”).

As a result, the assessment framework for this dimension is composed of the following:

Support services provided by the government: This sub-dimension assesses the recognition of BDS in the overall SME policy framework; the existence of a government institution with a leading role in design, delivery and monitoring of BDS for SMEs; and the extent to which public institutions provide different types of BDS tailored to the needs of different SME segments.

Government initiatives to stimulate private business support services: This evaluates government initiatives aimed at stimulating private markets for BDS. This includes both demand-related factors, such as financial incentives for SMEs to purchase bespoke advisory services, and supply-related factors, such as quality assurance tools for private consultants.

Business Support Services for the digital transformation of SMEs: The third sub-dimension looks at government-led initiatives to support the digital transformation of SMEs. These may include informational support, training, financial instruments and advisory services to better understand company needs, procure digital technologies and develop tailored digital road maps.

The section on outcome-oriented indicators for this dimension considers countries’ ability, (typically through national statistical offices or central banks) to regularly collect statistical information about the following indicators: i) number/share of SMEs benefitting from publicly (co-)funded BDS, ii) performance of SMEs benefitting from publicly (co-)funded BDS (e.g. output growth, employment growth, export growth), and iii) a range of digitalisation-oriented indicators based on the OECD ICT Access and Use by Businesses database (i.e. number/share of businesses with a website, using social media, using enterprise resource planning software, using customer relationship management software, purchasing cloud computing services, using artificial intelligence, performing big data analytics, using the Internet of Things).

Figure 9.2. Assessment framework – Business development services

Analysis

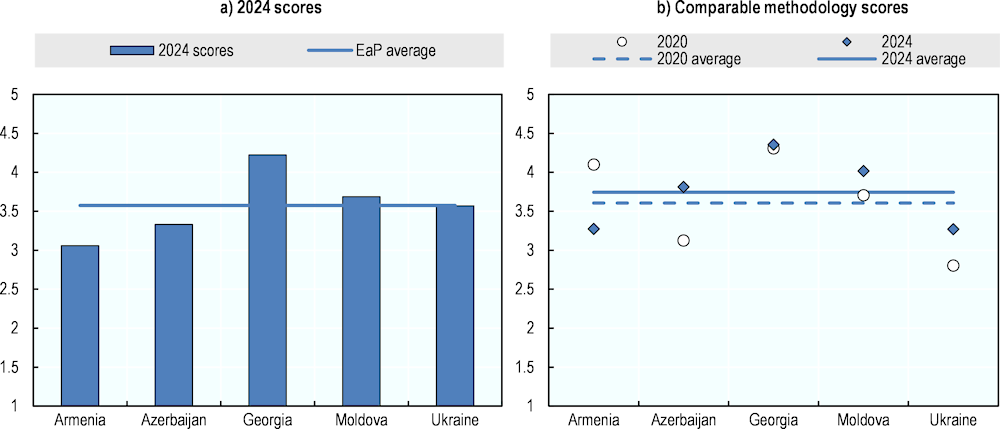

Regional trend and comparison with 2020 assessment scores

Average regional performance on this dimension is 3.57. While this is lower than the average score in the 2020 SBA assessment, the decrease is entirely driven by the introduction of the new sub-dimension on support services for the digital transformation of SMEs and of the outcome-oriented indicators, two areas in which countries perform worse than on the other sub-dimensions.

In fact, the in-depth assessment results for this dimension reveal a generalised improvement in countries’ policy approaches to the design, implementation and monitoring of business development services for SMEs. With the exception of Armenia, all countries have strengthened their SME support agencies and have incrementally expanded the range of services targeting different segments of the SME population. This trend is reflected in the score changes between 2020 and 2024 using comparable assessment methodologies.

Figure 9.3. Business Development Services, dimension scores

Note: See the “Policy framework, structure of the report and assessment process” chapter and Annex A for information on the assessment methodology.

Two organisational models are emerging for government agencies to manage the implementation of support services for SMEs

The first sub-dimension assesses whether BDS are recognised in the overall SME policy framework; the institutional arrangements for design, implementation and monitoring of BDS for SMEs; and the extent to which different types of BDS are tailored to the needs of different SME segments.

Table 9.2. Support services provided by the government, sub-dimension scores

|

Armenia |

Azerbaijan |

Georgia |

Moldova |

Ukraine |

EaP average |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sub-dimension score |

3.38 |

3.96 |

4.51 |

4.17 |

4.08 |

4.02 |

|

Planning and design |

3.55 |

3.55 |

5.00 |

4.27 |

4.27 |

4.13 |

|

Implementation |

3.33 |

4.39 |

4.39 |

4.28 |

4.50 |

4.18 |

|

Monitoring and evaluation |

3.18 |

3.73 |

3.91 |

3.73 |

2.82 |

3.47 |

Note: See the “Policy framework, structure of the report and assessment process” chapter and Annex A for information on the assessment methodology.

Overall, EaP countries’ performance in this sub-dimension has been rather stable. Although support services for SMEs have become less prominent in governments’ strategic documents (e.g. national SME strategies and action plans), this has been compensated by progress in implementation and monitoring. Georgia performs the best on this sub-dimension, continuing its tradition of developing well-structured SME strategies and action plans, relying on two strong implementing agencies. It is also the only country in the region with an advanced system to evaluate the impact of its support programmes on SME performance (See Box 12.3 in the Georgia chapter).

Two models are emerging for SME agencies to manage the implementation of support services for SMEs, which can be interpreted as the strategic choice of governments seeking to maximise their assistance to the SME population, given i) the size of their countries and ii) the extent to which the ecosystem of support service providers can complement government initiatives.

Smaller countries with a relatively limited community of support service providers, such as Georgia and Moldova, choose to have a strong role in the direct management and delivery of support programmes. Their national SME agencies, ODA and Enterprise Georgia and ODA (Organisation for the Development of Entrepreneurship), offer a wide range of support mechanisms (financial and non-financial) and engage in a continuous update of their services to meet evolving SME needs. From the point of view of the SME manager or individual entrepreneur, they are the go-to institutions helping SMEs and in most cases are the direct providers of support services.

Larger countries with a vibrant community of non-governmental service providers, such as Ukraine, opt for a more decentralised approach, acting as a platform and leveraging the capabilities of other actors in the ecosystem (e.g. international donors, local authorities, business associations). The online portal Diia.Business, managed by the Entrepreneurship and Export Promotion Office (EEPO), is without doubt the most developed and information-rich one-stop shop for SMEs in the EaP region, representing a gateway for Ukrainian entrepreneurs into the universe of support services available in the country, searchable by geographic location and type of support (e.g. financing, training, consultations).

Regardless of the model chosen, this assessment round reveals a trend towards strengthening SME support agencies across the EaP region. In Moldova, ODA (previously ODIMM) has undergone a reorganisation to incorporate stronger governance mechanisms (clearer mandate, qualification requirements for top management, audited financial statements); in Azerbaijan, KOBIA has expanded its activities and improved its monitoring mechanisms; and in Ukraine, EEPO is now a full-fledged SME support agency, with a broader mandate, more stable financial resources, and more numerous and qualified staff than the previous SME support unit advising the Ministry of Economy. The only exception to this trend is Armenia, where the capacity of the government to assist the SME population has been reduced due to the closure of the previous SME agency, SME DNC, and the transfer of its functions to other government entities.

In addition, since the last SBA assessment, several SME agencies have expanded their geographical footprint and opened offices outside the capital cities in an attempt to better serve local SMEs. This is the case for Azerbaijan (3 SME houses and 21 SME Development Centres), Ukraine (14 Diia.Business Support Centres), and Georgia (3 regional growth hubs). This physical expansion can take place either by opening tenders for independent actors willing to operate local offices of the national SME agency in a “franchise” model (Ukraine) or by keeping all operations, and related costs, internal to the agency (Georgia).

Finally, the range of available support services provided by the government is evolving, demonstrating an improved understanding of the needs of SMEs in the EaP region. While most countries have established financial support instruments for start-ups and trainings on basic business skills, some (Georgia and Moldova, especially) are introducing more complex programmes for different categories of SMEs and their specific needs, such as on greening production, digitalisation, internationalisation and technology upgrades.

Role and involvement of private BDS providers is (slowly) increasing

This sub-dimension measures government mechanisms to promote the development of private markets for BDS provision and stimulate the use of private BDS by SMEs.

Table 9.3. Government initiatives to stimulate private BDS, sub-dimension scores

|

Armenia |

Azerbaijan |

Georgia |

Moldova |

Ukraine |

EaP average |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sub-dimension score |

3.14 |

3.19 |

4.10 |

3.72 |

3.20 |

3.47 |

|

Planning and design |

3.00 |

2.60 |

3.93 |

4.20 |

3.33 |

3.41 |

|

Implementation |

3.31 |

3.44 |

4.33 |

3.67 |

3.49 |

3.65 |

|

Monitoring and evaluation |

3.00 |

3.67 |

3.89 |

3.00 |

2.33 |

3.18 |

Note: See the “Policy framework, structure of the report and assessment process” chapter and Annex A for information on the assessment methodology.

EaP countries’ average performance on this sub-dimension has improved slightly, with the most significant progress occurring in Azerbaijan and Moldova. Moldova, in particular, is the only EaP country acknowledging the role external consultants play in its national SME strategy and action plan, which explains its high score in the planning and design thematic block for this sub-dimension. Across the region, however, governments’ involvement of private players in the provision of BDS to SMEs remains limited or, at least, below potential.

First, governments can directly outsource some of their services for SMEs, especially trainings and consultancy, to specialised advisors. This is the most common form of involvement of private BDS providers across the EaP region, with all countries making use of this option in at least some respect. The clearest example is Azerbaijan, where SMEs can easily request consulting support from advisors pre-selected by KOBIA. Typically, these services are free of charge for end users, and while this format may ease access to business advice for financially constrained entrepreneurs, it also risks distorting the market by over-subsidising services that SMEs might otherwise be willing to pay for.

Second, governments can subsidise (a share of) the costs of consulting services incurred by SMEs through dedicated voucher schemes or other co-financing mechanisms. In practice, a more common version of this kind of support adopted by EaP countries’ SME agencies is to include expenses on business advisors among the eligible costs of broader grant programmes for start-ups and SMEs, as is the case in Georgia and Moldova. This approach has several advantages, as i) it allows SMEs to obtain advisory services from external consultants of their choice as opposed to pre-selected experts; ii) it makes specific industry or business expertise more affordable to SMEs, while typically requiring a cost-sharing mechanism from beneficiaries; and iii) it helps SMEs understand the value they can get from external advisors, thus stimulating demand and, in turn, the supply of consulting services in the countries.

Finally, governments can help increase SME awareness of external advisors by providing information on the availability and quality of private consultants. This can be done, for instance, through publicly available databases of providers of business development services and digital marketplaces, complemented by some quality assurance mechanisms. In the EaP region, only Moldova’s SME agency (ODA) offers this type of information, with a dedicated section of its website listing dozens of private consulting firms, their contact details, a short description of their areas of expertise, as well as the possibility for SMEs to rate their experience working with them.

An important initiative that should be mentioned in this area is the EBRD’s “Advice for Small Business” programme. The programme complements governments’ efforts to enable SMEs to access local consulting services by working on both sides of the market: on the demand side, the programme provides SMEs with co-financing to cover part of the cost of the advisory project (usually in the range of 50-60% of the total cost); on the supply side, it delivers business training and capacity building to local consultants to increase their expertise and ability to serve SMEs. According to the EBRD’s own data, the programme delivers important results for participating SMEs in EaP countries: 60% of them experience significant job creation and 83% see 28% increase in turnover , on average, within one year of advisory project completion (EBRD, 2021[8]).

Tailored programmes to support the digital transformation of SMEs have started to appear

This new sub-dimension captures the availability of dedicated government-led initiatives to support the digital transformation of SMEs, looking at both financial and non-financial instruments.

Table 9.4. Business support services for the digital transformation of SMEs, sub-dimension scores

|

Armenia |

Azerbaijan |

Georgia |

Moldova |

Ukraine |

EaP average |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sub-dimension score |

3.11 |

2.91 |

3.59 |

3.51 |

3.53 |

3.33 |

|

Design and implementation |

3.22 |

3.04 |

3.51 |

3.47 |

3.51 |

3.35 |

|

Monitoring and evaluation |

2.85 |

2.60 |

3.76 |

3.60 |

3.58 |

3.28 |

Note: See the “Policy framework, structure of the report and assessment process” chapter and Annex A for information on the assessment methodology.

The digitalisation of government services for businesses has been many years in the making, across OECD and non-OECD countries. In particular, a large number of dedicated online platforms have been set up to help SMEs and entrepreneurs liaise with the public administration and cut red tape. Typically, these “single digital portals” or “digital one-stop shops” serve as single entry points for accessing digital government services and reducing redundancy in requests from the public administration (OECD, forthcoming[9]). The digitalisation of businesses, primarily intended as the adoption of digital technologies, has also become a very visible trend since at least the early 2000s. The COVID pandemic, however, provided a short-term boost in this direction, requiring many SMEs to move online for the first time to be able to continue their operations.

All EaP countries recognise the importance of supporting SMEs’ digital transformation, although the extent to which this becomes an explicit policy priority translating into concrete support varies greatly across the region. Trainings on various digitalisation-related topics (e.g. transferring business processes online, digital marketing, digital finance) are the most common form of support provided by national SME agencies in EaP countries. Such trainings are typically free of charge, often delivered online, and represent an important first step in the range of services that governments can offer to SME managers and their employees willing to build their skill sets for the digital economy. The “one-to-many” nature of these trainings, however, cannot address the specificities of individual SMEs, which require tailored analysis and recommendations developed by specialised consultants.

For these reasons, some countries have also started to introduce full-fledged programmes for SME digitalisation, delivering individualised assessments and company-specific digitalisation road maps for beneficiaries, complemented by dedicated financial support instruments to procure digital technologies or obtain further specialised advisory services. Moldova has been the “first mover” in this area, with ODA’s dedicated initiative for SME digitalisation operational since 2022, which also included, in its first version, a digital maturity self-assessment. Georgia has followed suit: in 2023, Enterprise Georgia introduced a new programme as part of its regional growth hubs’ services to help SMEs improve their digital skills and adopt digital technologies. With the assistance of digital transformation experts, SMEs first undertake an overall business diagnostic exercise and then develop a tailored plan with recommendations on how to digitalise their operations. Co-financing mechanisms to purchase digital solutions and develop digital skills are also available in both countries, up to EUR ~9 000 in Georgia and EUR ~26 000 in Moldova. In addition, the EU-funded EU4Digital facility opened its EU4Digital Academy, providing free-of-charge digital skills training to SMEs’ employees in EaP countries, in areas such as digitalisation of businesses, digital marketing and e-commerce (EU4Digital, 2023[10]).

The potential contribution of non-governmental actors to further SME digital transformation should also be noted. Countries where SME agencies have not (yet) introduced advanced support instruments in this area should consider the pool of active players in the ecosystem as potential partners in the development of new support programmes for SME digitalisation. This is especially the case for Armenia and Ukraine, where donor-led initiatives, such as EBRD-trained consultants on SME digitalisation (Armenia) or the fast-growing IT sector (Ukraine) could supply the industry expertise and act as mentors for traditional SMEs to advance in their digital transformation.

Finally, EaP countries’ practices to build the evidence base on the state of SME digitalisation shows ample room for improvement. Only Georgia and, to a lesser extent, Ukraine regularly collect statistical indicators on businesses’ adoption of digital technologies with data broken down by enterprise size class; and Armenia carried out a first pilot survey in 2023 following Eurostat’s model on ICT Usage in Enterprises. These are important indicators to monitor in order to determine whether smaller companies can bridge the digitalisation gap with larger ones, which has been highlighted as a determinant of productivity inequality among firms (OECD, 2021[4]).

Box 9.1. European Digital Innovation Hubs

European Digital Innovation Hubs (EDIHs) help companies as well as public sector organisations to respond digital challenges and become more competitive. Through their regional presence, they can easily reach local companies and address them in the local language while also giving them access to the broader innovation ecosystem. As the network of digital innovation hubs is EU-wide, companies can benefit from European best practices across hubs, which foster co-operation and knowledge transfer between all stakeholders. This unique combination of regional expertise, paired with a European network, enables well-tailored support on digital transformation with access to a community of hubs.

Digital Innovation Hub services

EDIHs receive 50% of their funding from the European Commission and 50% from the respective member state, associated country, or region, or from private sources. The hubs’ services can be divided into four main categories: i) access to technical expertise and the opportunity to “test before invest” in new technology, often through the involvement of third-party companies; ii) support to identify financing and investment opportunities; iii) provision of trainings and skill development; and iv) access to the innovation ecosystem and European network to share skills, resources, and knowledge.

EDIHs have proven to be important enablers for the digital transformation of SMEs. This best practice can be replicated under the EU’s Economic and Investment Plan for the EaP region, which is worth EUR 2.3 billion in grants, blending and guarantees, with a potential to mobilise up to EUR 17 billion in public and private investments (EIB, 2020[11]).

Latvia’s Digital Innovation Hub

Latvia’s Digital Innovation Hub mainly targets SMEs and is co-ordinated by the local IT Cluster. It aims at supporting the digital transformation of local companies by i) raising awareness about the benefits of digitalisation through marketing campaigns, “kickstart” workshops, networking events and trainings on general digital skills; ii) matchmaking with mentors and providing small grants (EUR <5 000) to test new technologies; iii) providing support for technology adoption, through grants and other financial instruments for process digitalisation as well as dedicated skill upgrades; and iv) fostering further digital transformation via corporate hackathons, access to industry experts and grants for more innovative technologies.

The way forward

As EaP countries update their policy approaches to design and implement business development services for their SME populations, the following recommendations could be taken into consideration.

All EaP countries can benefit from the inclusion of dedicated measures to deliver BDS for SMEs in strategic policy documents, which can provide certainty and medium-term planning in implementation. This is particularly relevant for Azerbaijan and Ukraine, which at the moment lack dedicated national strategies for SME policy, although SMEs appear as an important target of Ukraine’s National Recovery Plan drafted in 2022.

As countries expand the local presence of their SME support agencies, they should devise ways to ensure the sustainability of regional offices through strong quality-control mechanisms (if outsourced, such as in Ukraine) and cost/benefit analysis (if developed internally, such as in Azerbaijan and Georgia).

To leverage the existence non-governmental business development services, EaP countries could embed single information portals with information on all actors in the BDS ecosystem into their SME agencies’ websites, including donor-led initiatives and private quality-assured consultants. Ukraine’s Diia.Business portal (https://business.diia.gov.ua/en/business-map) offers a useful example in this respect and an opportunity for peer learning within the EaP region.

To develop a more market-based provision of BDS to SMEs, EaP governments could consider outsourcing support services to private BDS providers and increasing the offer of co-financing mechanisms to SMEs for first-time BDS use, enabling firms to choose their preferred providers. This could be particularly useful in countries such as Azerbaijan, where many BDS are provided free of charge and where such financial support instruments are missing.

Facing evolving SME needs, EaP countries (especially Armenia, Azerbaijan and Ukraine) could upgrade existing initiatives and develop dedicated support programmes for SME digitalisation, which should include elements to enhance digital skills, company-specific digitalisation road-maps and financial support tools to facilitate technology adoption. In addition, further investment in cyber-security (skills and technologies) are needed in all EaP countries, as a key enabler to increase trust and the uptake of digital solutions.

While there has been good progress across the region in monitoring the implementation of action plans and programme take-up, there is a need to improve the evaluation of business support programmes, in particular to assess the impact of BDS on various measures of SME performance, as well as on the emergence of the overall BDS market. Georgia’s experience could be a useful example in this respect (See Box 12.3 in the Georgia chapter).

To build the evidence base to monitor SME digitalisation, all EaP countries could expand the collection of statistical indicators on the adoption of digital technologies in the business sector. The OECD database on ICT Access and Use by Businesses offers an important methodological reference in this respect.

Innovation policy for SMEs

The OECD/Eurostat Oslo Manual (4th edition) defines business innovation as “a new or improved product or business process (or combination thereof) that differs significantly from the firm’s previous products or business processes, and that has been introduced on the market or brought into use by the firm” (OECD/ Eurostat, 2018[14]). It distinguishes between three types of innovation based on their degree of novelty: an innovation can be new to the firm, the market or the world. By introducing new knowledge and technologies in the firm’s production process, innovative practices and activities help firms expand and boost productivity, even if only a small percentage of them advance to the global technological frontier (EBRD, 2014[15]).

Beyond increasing economic output, recent developments and global trends have demonstrated the role innovation can play in tackling global social and economic challenges. Innovation and research and development (R&D) have been at the forefront of the global response to the outbreak of COVID-19, including through the development of vaccines and medical treatments, but also by providing digital solutions to tackle social distancing, which has accelerated the automation and adoption of digital technologies in many spheres of society, and has often been driven by the private sector (OECD, 2022[16]).

SMEs are essential for the generation and diffusion of innovations, but face difficulties in developing and scaling up innovative activities due to their limited size and financial and staff capacity. Although some SMEs are innovation leaders in their field, they generally tend to introduce fewer new products and technologies than larger, more established firms.

Governments can support innovation through public investment in science and R&D. Specifically for SMEs, policy makers can also foster innovation at the firm level, by building an ecosystem conducive to co-operation among firms and creating linkages with universities and research centres, encouraging the use of applied research outputs, facilitating access to technology, protecting intellectual property, and introducing financial incentives for firms to engage in innovative activities.

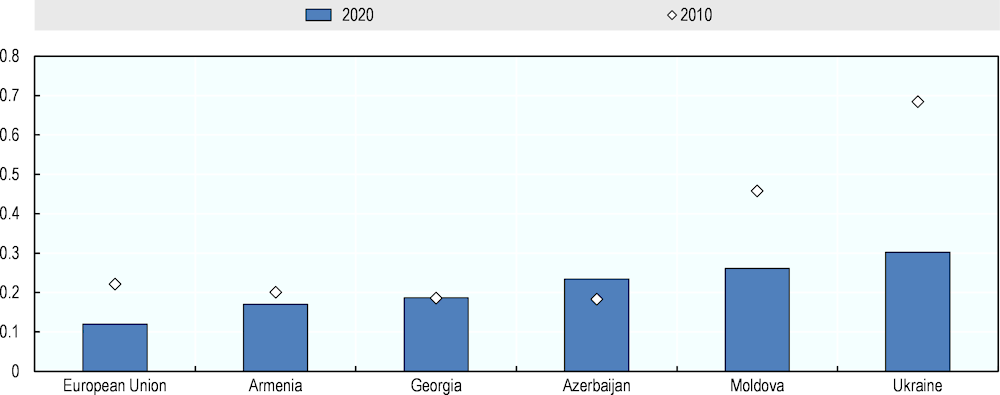

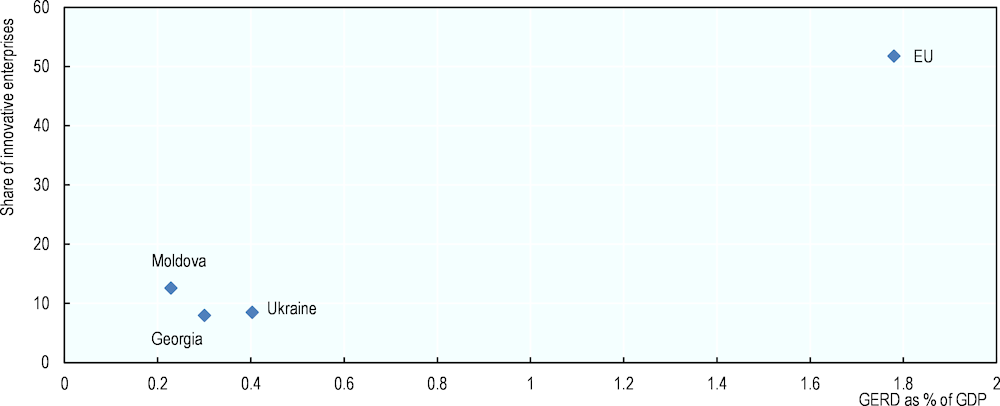

While a data breakdown on innovation activities in the business sector by enterprise size class is not available, overall innovation performance in the EaP region remains well below that of EU countries (Figure 9.4), both in terms of innovation inputs (gross domestic expenditure on R&D, or GERD, as % of GDP) and innovation outputs (share of enterprises introducing product or process innovation).

Figure 9.4. Innovation performance in EaP countries vs. EU (2020)

Notes: GERD = gross domestic expenditure on research and development. Data for innovative enterprises in Georgia (process innovation) are for 2022. Data for Armenia and Azerbaijan are not available.

Source: National Statistical Offices for EaP countries; Eurostat for the EU.

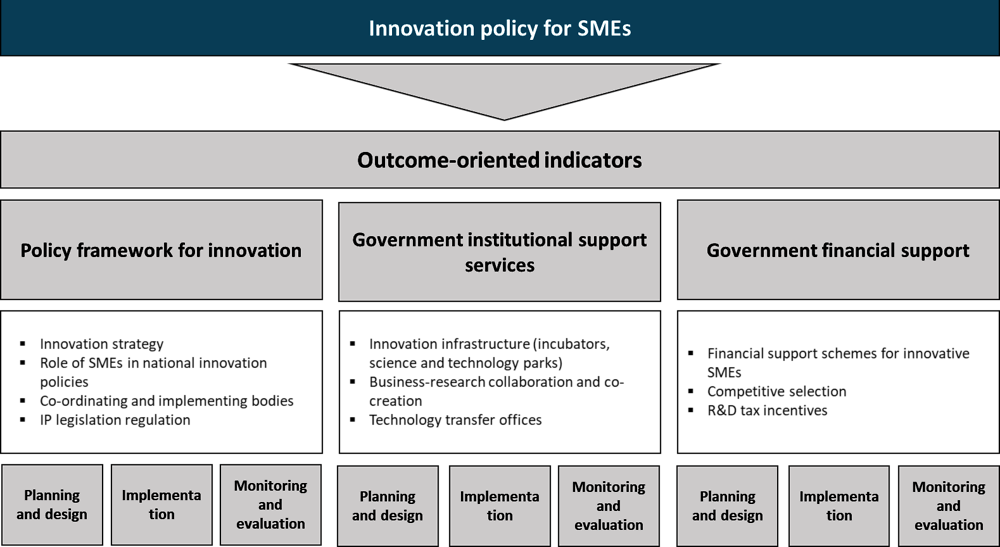

Assessment framework

This dimension considers the strength of the policy framework for innovation, with particular reference to SME innovation, the different support services provided by governments to stimulate innovative activities by SMEs, and the availability of direct and indirect financial support instruments to incentivise SME innovation.

Compared to the previous SBA assessment, the main methodological changes introduced in this dimension are the removal of a sub-dimension on “non-technological innovation” (while keeping relevant questions and incorporating them into the other sub-dimensions) and the analysis of countries’ ability to regularly collect quantitative information to monitor the impact of policies on actual SME innovation performance (“outcome-oriented indicators”).

As a result, the assessment framework for this dimension is composed of the following:

Policy framework for SME innovation: This sub-dimension assesses the overall policy approach to foster innovation in the business sector, with particular reference to dedicated national strategic frameworks, the existence of a co-ordinating agency and specific provisions for SMEs.

Government institutional support services for innovative SMEs: This captures the availability and quality of institutional measures to support innovation in the SME sector, with a focus on innovation infrastructure: incubators, science and technology parks, innovation centres and technology transfer offices.

Government financial support for innovative SMEs: Here, the availability of direct and indirect financial support measures to encourage SMEs to innovate and carry out R&D activities is evaluated. The role of demand-side policies such as public procurement of innovation and functional procurement is also considered.

The section on outcome-oriented indicators for this dimension considers countries’ ability, (typically through national statistical offices or central banks) to regularly collect statistical information about the following indicators: i) labour productivity in SMEs; ii) SMEs introducing product/process innovations; iii) R&D expenditure in the business sector, by business size class; and iv) sales of new-to-firm innovations as a share of the firm’s turnover.

Figure 9.5. Assessment framework – Innovation policy for SMEs

Analysis

Regional trend and comparison with 2020 assessment scores

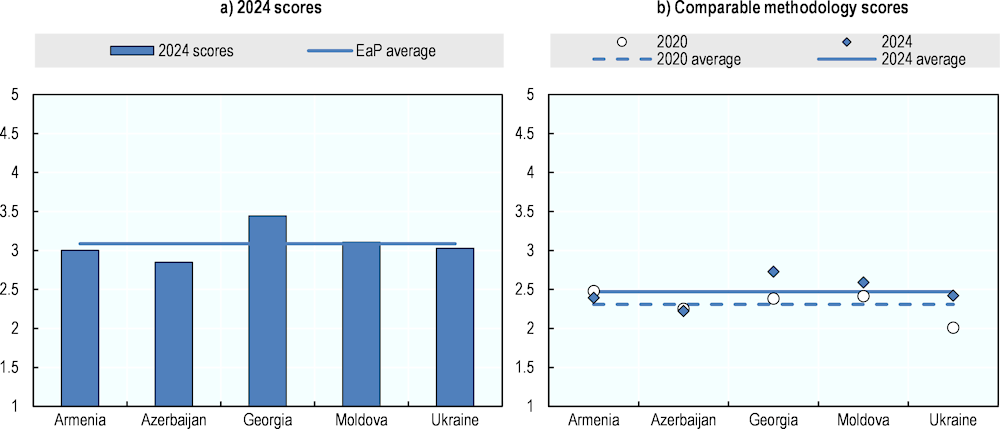

Regional performance on this dimension is reflected in an average score of 3.09. This is a slight increase compared to the 2020 SBA assessment, and is also reflected in the regional trend visible using comparable assessment methodologies.

While the policy frameworks for innovation have not evolved greatly in the last four years, the options for obtaining financial support for innovative SMEs have become more diversified and represent the area with the most interesting developments. The main improvements are recorded in Ukraine, which started from the lowest base in 2020 and whose performance is also boosted by the national statistical office’s advanced practices to collect outcome-oriented indicators for this dimension.

Figure 9.6. Innovation policy for SMEs, dimension scores

Note: See the “Policy framework, structure of the report and assessment process” chapter and Annex A for information on the assessment methodology.

Policy frameworks for innovation lack a strong focus on SME innovation

This first sub-dimension looks at the overall strategic approach that SME policies are based on, as well as co-ordination and implementation mechanisms. It evaluates the level of development of the overarching policy framework for supporting the innovation of the business sector, especially of SMEs.

Table 9.5. Policy framework for innovation, sub-dimension scores

|

Armenia |

Azerbaijan |

Georgia |

Moldova |

Ukraine |

EaP average |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sub-dimension score |

3.06 |

3.11 |

3.50 |

2.99 |

2.72 |

3.07 |

|

Planning and design |

3.56 |

3.03 |

3.08 |

3.13 |

3.40 |

3.24 |

|

Implementation |

3.27 |

3.58 |

3.93 |

3.04 |

2.47 |

3.26 |

|

Monitoring and evaluation |

1.70 |

2.20 |

3.25 |

2.60 |

2.10 |

2.37 |

Note: See the “Policy framework, structure of the report and assessment process” chapter and Annex A for information on the assessment methodology.

Policy frameworks for innovation in EaP countries have not substantially improved since the previous SBA assessment. Dedicated national strategies for innovation with clearly defined and operational action plans tend to be the exception rather than the rule, and only present in Moldova (the “National Programme in the Field of Research and Innovation 2020-2023”) and Ukraine (the “Innovation Development Strategy 2030”). However, countries compensate for this shortcoming by incorporating elements of innovation policy in other strategic documents, such as the governments’ broad strategy for socio-economic development (Armenia and Azerbaijan) and/or the national SME strategies (Armenia and Georgia). Nevertheless, innovation and SME industrial or technology policy remain generally separated. This, in turn, continues to hamper science-business linkages for intellectual property, and prevents the integration of innovation angles into large-scale SME support programs that effectively deliver on established performance goals. Additionally, specific policy targets on SME innovation remain very rare, which can be interpreted as a reflection of the limited understanding of the barriers to SME innovation and relatively low ranking of this policy area in EaP governments’ economic reform priorities.

On the institutional setting and implementation side, countries’ performance is more heterogeneous. Traditionally, support for innovation in EaP countries has been directed to universities and research centres carrying out fundamental research, often administered by the responsible ministries. However, in the last decade, EaP governments have re-oriented the focus of their support for innovation towards the business sector. As a result, dedicated innovation agencies have been created in some EaP countries (Georgia, Moldova and, most recently, Azerbaijan), but their mandates and areas of intervention differ greatly and range from start-up development to technology transfer and go as far as carrying out nuclear research (Azerbaijan). Georgia’s Innovation and Technology Agency appears to be the best example in the region, with a track record of providing a wide range of support instruments for start-up development and the IT sector.

Monitoring and evaluation of innovation policies for SMEs show ample room for improvement. Three main factors appear to be behind the relatively low performance in this area. First, as national policy documents do not focus on the SME sector, there is a scarcity of SME-specific initiatives that can be assessed. Second, EaP countries typically tend to monitor the implementation of activities rather than evaluate the impact of support programmes; the only exception in this regard is Georgia, which is planning to expand Enterprise Georgia’s impact evaluation methodology to Georgia’s Innovation and Technology Agency’s (GITA) operations as well. Third, outcome-oriented indicators in the area of SME innovation are generally not available, with the notable exceptions of Azerbaijan and Ukraine. Ukraine participated in the EU Community Innovation Survey 2020 and reports on nationwide statistical information on sales of new-to-firm innovations as a share of turnover. Azerbaijan‘s statistical office compiles data on R&D expenditure by enterprise size class.

Institutional support is slowly evolving, with interesting developments in technology transfer

The second sub-dimension assesses the availability of institutional support for innovative SMEs, including innovation infrastructure such as incubators, science and technology parks, technology transfer offices and innovation centres.

Table 9.6. Government institutional support services for SMEs, sub-dimension scores

|

Armenia |

Azerbaijan |

Georgia |

Moldova |

Ukraine |

EaP average |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sub-dimension score |

2.77 |

2.88 |

3.26 |

3.33 |

3.11 |

3.07 |

|

Planning and design |

3.00 |

3.00 |

3.70 |

3.70 |

3.30 |

3.34 |

|

Implementation |

3.08 |

3.17 |

3.33 |

3.33 |

3.00 |

3.18 |

|

Monitoring and evaluation |

1.67 |

2.00 |

2.33 |

2.67 |

3.00 |

2.33 |

Note: See the “Policy framework, structure of the report and assessment process” chapter and Annex A for information on the assessment methodology.

Government in-kind support services for innovative companies continue to expand in EaP countries, although they remain heavily oriented towards assisting entrepreneurs active in the digital and IT sectors. All countries have more or less widespread networks of incubators and accelerators supporting business creation and innovative start-ups with co-working facilities, trainings and networking opportunities. Such initiatives can be managed directly by governments (Azerbaijan’s SABAH.lab) but are often sponsored and implemented by private players (Ukraine Start-up Fund’s accredited accelerators), non-governmental organisations (Moldova’s Tekwill) and the donor community (Armenia’s Enterprise Incubator Foundation).

Science and technology parks can also support resident companies (both newly created and established ones) with logistical infrastructure as well as research and prototyping laboratories. Progress in this area has been more mixed: Georgia’s GITA has expanded its physical infrastructure and opened two new techno parks (now eight in total); Armenia, Azerbaijan and Moldova have not introduced considerable expansions to their existing facilities; Ukraine adopted several laws to stimulate the development of industrial parks and manufacturing in the country, and even though 60 industrial parks were registered as of early 2023, most of them are reportedly not active and the government did not allocate any budget in this area in 2022.

The most interesting developments have occurred in the area of science-business linkages, where EaP countries’ performance has traditionally been very weak in spite of a legacy of directing public funding towards supporting basic research carried out by public universities and research organisations. This has started to change in recent years, with renewed efforts to promote science-industry interactions, technology transfer and co-creation of knowledge. This is particularly the case in Georgia, where the innovation agency, GITA, carried out a first technology transfer pilot programme with the goal of identifying scientific outputs with high commercial potential and assisting the research teams to negotiate licensing and business deals with potential business partners. Ukraine has also expanded its network of Technology and Innovation Support Centres (17 active in 2023), offering support to innovators to register for IP protection, enter into IP agreements with partners and clients, and help with technology search.

Government financial support for innovative SMEs remains primarily focused on the IT sector

This sub-dimension analyses the availability and effectiveness of the direct and indirect financial incentives the EaP governments are providing to encourage SMEs to engage innovative activities, from investing in R&D to purchasing innovative technologies.

Table 9.7. Government financial support for innovative SMEs, sub-dimension scores

|

Armenia |

Azerbaijan |

Georgia |

Moldova |

Ukraine |

EaP average |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sub-dimension scores |

3.62 |

2.82 |

3.56 |

3.28 |

2.67 |

3.19 |

|

Planning and design |

3.55 |

3.00 |

3.55 |

3.55 |

3.18 |

3.36 |

|

Implementation |

3.86 |

3.00 |

3.86 |

3.29 |

2.71 |

3.34 |

|

Monitoring and evaluation |

3.22 |

2.11 |

2.91 |

2.78 |

1.67 |

2.54 |

Note: See the “Policy framework, structure of the report and assessment process” chapter and Annex A for information on the assessment methodology.

The lack of financing is reportedly one of the most important constraints on innovative activities, given the inherently risky nature of innovation and uncertainty of financial returns. The problem is even more pronounced for smaller, knowledge-intensive companies due to the relative intangible nature of their assets. Governments can help overcome such obstacles by making it easier for SMEs to innovate and reduce the financial risk of investing in innovative projects. Well-designed financial support aims at catalysing experimentation with new ideas, “crowding-in” private investment in R&D and acknowledges the complexity of engaging in innovation activities and accompanying SMEs along the entire innovation cycle (development, engineering, production and commercialisation).

Overall, the average performance of EaP countries on this sub-dimension has improved since the previous SBA assessment, mostly driven by positive developments in Armenia and Ukraine. However, a disproportionate focus on the IT sector and start-up segment persists. While this can be seen as a response to the growing IT skills and IT-oriented entrepreneurship in the EaP region1, governments should not neglect other sectors that could benefit from public support to innovation. Agriculture, for instance, could benefit from the diffusion of relatively simple technologies to increase the productivity of what still remain mostly small-scale producers.

Direct financial support instruments for innovative SMEs have become available in all EaP countries. These typically take the form of grants in the range of USD 9 000 (Ukraine) to EUR 54 000 (Georgia) and can have diverse objectives, such as to stimulate enterprise creation and idea commercialisation (Armenia and Ukraine), facilitate prototyping and improve manufacturing (Moldova), and develop products and services with the potential for internationalisation (Georgia). Such grants are typically awarded via a competitive process and, even though they can make a real difference for the winners, they are, by design, only able to reach a limited number of beneficiaries. Furthermore, the extent to which risk-sharing features are considered when designing grants for innovation varies greatly from country to country: while Azerbaijan’s grants do not require any contributions from beneficiary SMEs, Moldova’s “Program to Support Digital Innovations and Technological Start-ups” covers at most 80% of the amount of the investment project, and Georgia’s innovation matching grants (discontinued in 2022) required up to 50% of the eligible project costs to be secured from beneficiaries. It should also be noted here that EaP countries continue to be eligible for the main EU funding programme for research and innovation (Horizon 2020, followed by Horizon Europe), although their actual participation in terms of funding received, especially by SMEs, is very small (Box 9.2).

Indirect financial incentives for innovation and R&D remain rare and limited with respect to the targeted sectors and business population. Azerbaijan has introduced a “Startup certificate”, through which micro and small businesses can benefit from a tax exemption on the profits generated by the sale of innovative products or services for a period of three years. The Ukrainian government has recently established Diia.City, a legal and tax environment incentivising investment and employment for companies operating in the IT sector. The most interesting development in this area has occurred in Armenia, which has introduced a new set of “measures to modernise the economy”. Through this programme, entrepreneurs benefit from subsidised loan and leasing agreements to purchase new machinery and equipment. This package has been very well received by Armenian entrepreneurs, with nearly 1 000 credit and leasing agreements signed in the first 9 months of the programme and manufacturing companies reportedly starting to export thanks to the increased quality of their production.

Box 9.2. EU support for research and innovation: Horizon 2020 and Horizon Europe

Following Horizon 2020, the biggest EU research and innovation programme with a budget of almost EUR 80 billion of funding, an even bigger successor programme called Horizon Europe was launched in 2021 with a budget of EUR 95.5 billion until 2027. The new programme is meant to facilitate collaboration and strengthen the impact of research and innovation within the context of economic development. The investments made possible through the programme should boost economic growth and enhance industrial competitiveness.

Horizon Europe consists of three pillars, reflecting the topics of excellent science, global challenges and European industrial competitiveness, and an innovative Europe, which are built upon the evaluation of the previous Horizon 2020 programme. The first pillar is promoting financing for researchers through the European Research Council and provides fellowships to new talented researchers. The second pillar is exploiting European clusters supporting collaborative research on key subjects such as health and digitalisation. The third pillar includes the new feature of the European Innovation Council that especially focuses on supporting SMEs and start-ups. The new programme is supposed to maximise the impact of the investments in research and innovation through better access to support also for riskier investments and more collaboration on a European level.

EaP countries participate in Horizon Europe and participated in Horizon 2020 with different degrees of involvement. Georgia and Ukraine have benefitted the most, with the highest amounts of contributions received and the largest degree of SME participation. Ukraine and Armenia were awarded the largest average grant.

Table 9.8. Participation of EaP countries in Horizon 2020 and Horizon Europe

|

Country |

Net EU contribution (EUR) |

Participating entities (number of unique organisations) |

Average grant (EUR) |

SME share of EU contribution |

Number of unique SMEs involved in projects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Armenia |

7 163 926 |

23 |

159 198 |

2.3% |

4 |

|

Azerbaijan |

686 989 |

19 |

28 625 |

0.0% |

0 |

|

Georgia |

11 141 839 |

44 |

148 558 |

4.8% |

3 |

|

Moldova |

10 478 020 |

48 |

105 839 |

17.9% |

7 |

|

Ukraine |

63 195 461 |

210 |

208 566 |

31.0% |

47 |

Note: Numbers in the table refer to EaP countries’ participation in both Horizon 2020 and Horizon Europe as of July 2023. OECD analysis on selected indicators since the beginning of Horizon 2020. Armenia, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine are “associated countries” and as such enjoy equal participation rights as EU member states.

Source: (European Commission, 2023[17]).

Box 9.3. Indirect financial incentives for innovation

Governments can support innovation in the business sector through both direct and indirect financial incentives. On the one hand, direct incentives such as grants and subsidised loans are a common way to encourage SMEs to innovate. These direct financial supports are, however, prone to misallocations as they are received by the beneficiaries before any investment is made.

On the other hand, indirect incentives provide a good alternative as they are granted after the firm has already invested in new technology or R&D activities. Examples of indirect support are broad-based (i.e. available to a large number of companies) fiscal incentives, such as tax allowances, exemptions or deductions, as well as tax credits. The specific functioning of the tax benefit, however, differs depending on the instrument: while tax allowances, exemptions and deductions reduce the taxable amount before assessing the tax, a tax credit is the amount subtracted directly from the beneficiary’s tax liability after it has been computed. With regard to R&D, allowing related expenses to be fully deducted remains the default among OECD countries.

Indirect financial incentives need to also be carefully designed in order to be beneficial for the addressed firms. Tax benefits on profit, for example, might not lead to the desired stimulation of investment in innovation among SMEs, particularly in the case of innovative start-ups, which may not yet make any profits and thus may not be able to take advantage of such tax benefits. Thus, for firms with insufficient tax liability, standard types of tax relief instruments do not work efficiently on their own. Indirect support instruments can, therefore, be refined further to address these segments of companies.

One way to do so is through carry-over provisions of tax benefits. These are popular instruments among OECD countries and partner economies, as they allow moving the tax benefit on profits to future years. Thus, when the company will make a profit, it will be able to claim the carry-over and reduce its tax payment for that period. The time horizon for the claim can be finite or infinite, and varies substantially across OECD countries: in 2022, it ranged from 3 years (the Czech Republic) to 20 years (the United States).

A step further is the provision of offsetting payments or “refunds”, which can be particularly beneficial for young and innovative firms at the stage of investing in developing and launching their products. In this case, the tax authority uses a tax refund to cover the company’s unpaid claims and thus setting these off with their tax credit. This can also be applied to offset payroll taxes or social security contributions.

Source: (OECD, 2021[18])

The way forward

While renewing their policies to build a more innovative SME sector, EaP countries should focus on the following reform priorities. The EC-OECD STIP Compass database (https://stip.oecd.org/stip/) collects information on innovation policies across OECD and partner countries and could inspire policy reforms in the EaP region based on international policy examples.

All EaP governments can better highlight the role of SME innovation in their strategic documents. Whether in national strategies for innovation or in sectoral SME strategies, the specific obstacles for SME innovation should be acknowledged, addressed through dedicated measures and monitored against SME-specific policy targets.

Some countries (especially Armenia and Ukraine) could strengthen their co-ordination and implementation capacity by clearly identifying bodies tasked with supporting SME innovation and building staff capacity to design and implement dedicated programmes.

To foster science-business linkages, governments should build the skills of agencies tasked with technology transfer and intensify co-operation between academia and the private sector. This is particularly relevant for countries where successful donor-led initiatives are coming to an end (e.g. Georgia) or where governments’ efforts are at a very initial stage (e.g. Armenia). For instance, enhancing co-operation would require promoting start-ups based on applied research insights and co-financing of research services, as well as ensuring closer ties between applied public research and its commercial demand and potential applications.

When devising specific support programmes for SME innovation, governments should consider assisting the SME population beyond the start-up segment as well as services to support technology absorption in more mature SMEs (as is the case in Georgia and Moldova).

With regards to direct financial incentives for innovation, governments (especially Azerbaijan and Ukraine) should ensure that a matching component is required when awarding grants/soft loans, to share risks with beneficiaries of financial instruments for innovation.

Governments should also consider introducing more flexible indirect financial incentives for innovation, which are more market-based and less prone to distortions than direct instruments (Box 9.3), and broadening the set of potential beneficiaries of support programmes. Alternative finance, crowdfunding, and cooperation with networks of business angels can be considered.

Last, to empower national administrations to monitor and evaluate the impact of their innovation policies, governments should strengthen the national statistical office’s capacity to collect information about SME innovation performance. Eurostat’s Community Innovation Survey and the European Innovation Scoreboard offer useful references in this respect.

SMEs in a green economy

Human-induced climate change is under way and accelerating, leading to many weather and climate extremes in every region across the globe. This has led to widespread adverse impacts, disrupting economies, transforming eco-systems, and causing damages to nature and people, especially the most vulnerable groups (IPCC, 2023[19]). To address this key global policy challenge, countries are pledging to mitigate and adapt to climate impacts with self-defined Nationally Determined Contributions, detailing their commitments to cut greenhouse gas emissions and limit global average temperature rise to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

The primary focus has traditionally been on large corporations, seen as the largest emitters of greenhouse gases. However, it is estimated that over 80% of their emissions are derived from their supply chains, which are often composed of smaller enterprises that perform essential services in the production process. Thus, although individual SMEs may not be large carbon emitters, the collective emissions of this business segment, amounting to roughly 90% of businesses worldwide, mean that SMEs will be critical to achieving global decarbonisation targets (WTO, 2022[20]). EaP countries have ample margins to decarbonise their economies to bring them closer to greener economies (Figure 9.7).

Figure 9.7. Carbon intensity of EaP economies

Environmental challenges, and related “green economy” opportunities, deserve further attention from policy makers when it comes to the promotion of biodiversity and combating environmental degradation. Biodiversity and eco-system services provide invaluable – but often invisible – benefits at global, regional and local scales. These include services such as nutrient cycling, habitat provisioning, pollination, erosion control and climate regulation. The need to mainstream biodiversity and ecosystem services more effectively into national and sectoral policies has recently gained renewed impetus on the global policy agenda (OECD, 2018[21]).

Furthermore, a growing number of companies worldwide recognise the advantages of resource efficiency and cleaner production in terms of reduced costs in materials, energy, water and compliance with environmental requirements, as well as in responding to customers’, investors’ and local communities’ expectations. However, SMEs, and particularly micro-businesses, have limited capacity to learn about and interpret environmental regulations, along with financial constraints to invest in green practices beyond environmental requirements (OECD, 2023[22]).

Governments have a range of tools at their disposal to support SMEs in adopting greener practices. These can be roughly divided into regulatory, financial, and informational tools. Regulatory tools involve using the regulatory system to incentivise better environmental performance, including by providing incentives for firms that exceed environmental standards. Financial tools include ensuring that SMEs can access financial resources to implement green practices, as well as helping to create markets, for example by implementing green public procurement policies. Informational tools include providing SMEs with the information they need to adopt green practices, as well as providing recognition and certification for those that do. Good policies can help shift the conversation about greening SMEs into a discussion about the business benefits that greening can bring, rather than the costs.

A key issue for SMEs is understanding the benefits of adopting more resource-efficient practices, and the positive impact that these practices can have on their bottom line. While businesses may be aware that they can reduce their costs by using less energy, water and material inputs and by cutting their waste levels, they may not be aware of how to do it, or whether they are able to fund it (OECD, 2018[23]) Addressing this issue includes supporting access to finance, as well as providing direct support to SMEs in terms of what measures they can take to improve their performance. Governments also have a role in improving the business case for SMEs, by developing new markets through green public procurement, and by recognising green achievement through awards and ecolabels and communicating it to the public (OECD, 2018[23]).

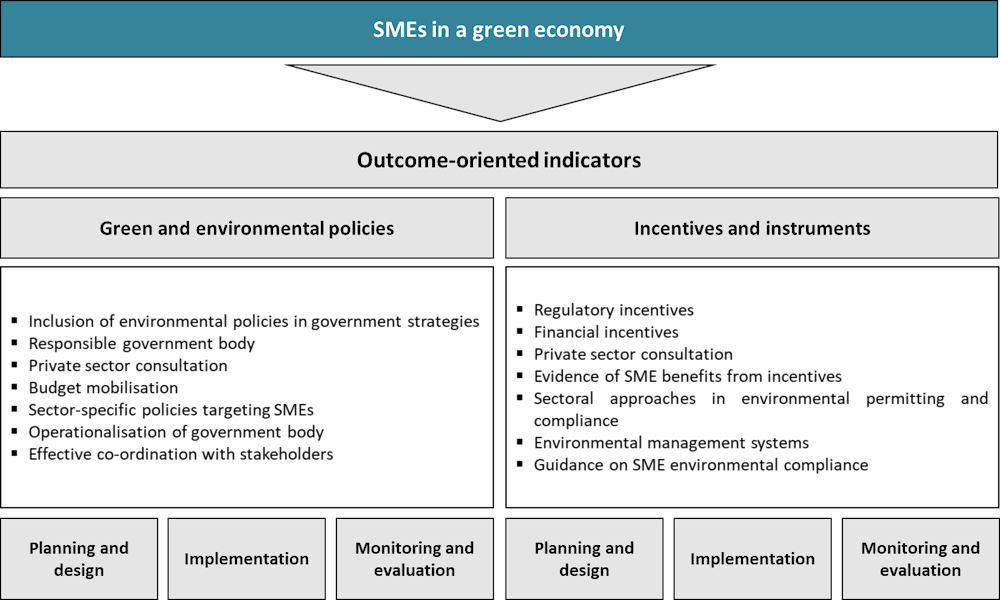

Assessment framework

This dimension analyses governments’ approaches to help SMEs improve their environmental performance, both via the general policy framework for green and environmental policies, as well as through dedicated regulatory and financial incentives.

Small changes have been introduced to the methodology of this dimension since the previous assessment: to better capture reporting requirements on environmental performance and the availability of green finance instruments; and to analyse countries’ ability to regularly collect quantitative information about actual SME environmental performance (“outcome-oriented indicators”).

As a result, the assessment framework for this dimension is composed of the following:

Framework for green and environmental policies targeting SMEs: This sub-dimension examines the overall set of environmental policies targeting SMEs, as well as the greening aspects in national SME, sectoral and innovation policy frameworks. It also considers the presence of operational government agencies assisting SMEs with the adoption of greener practices.

Incentives and instruments: The second sub-dimension explores the existence and implementation of different instruments and measures of whether the government provides regulatory and financial incentives to SMEs, whether there is any evidence that SMEs benefit from those incentives, and how such support schemes are structured and delivered.

The section on outcome-oriented indicators for this dimension considers countries’ ability, (typically through national statistical offices or responsible government agencies) to regularly collect statistical information about the following indicators: SMEs having adopted environmental management systems; SMEs having implemented resource-efficiency and pollution-reduction measures; SMEs that offer green products or services; SMEs with a turnover share more than 50% generated by green products or services; and the number of environmental public procurement contracts.

Figure 9.8. Assessment framework – SMEs in a green economy

Analysis

Regional trend and comparison with 2020 assessment scores

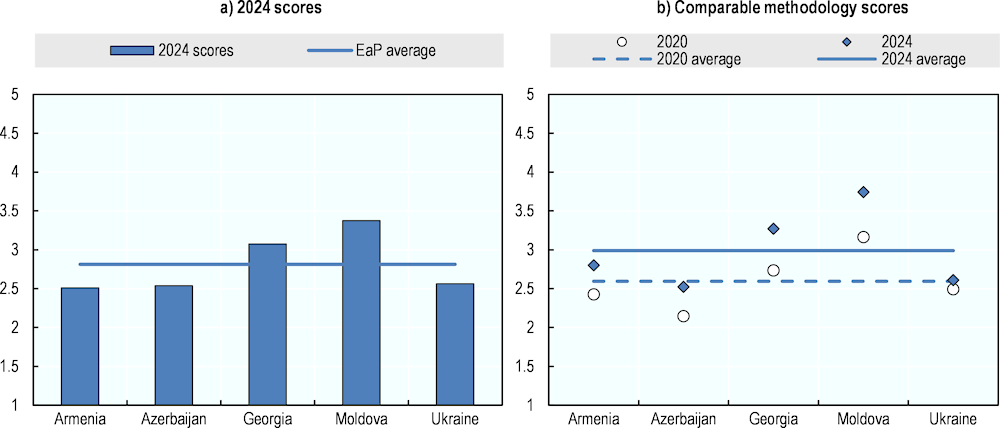

Regional performance on this dimension is reflected in an average score of 2.81. This is a marginal improvement compared to the 2020 SBA assessment, although it becomes more pronounced when looking at scores generated by comparable assessment methodologies.

Overall, policy settings for environmental protection across the region rarely address SME specificities, and financial incentives are not widely available. Moldova is a welcome exception in this respect; it is both the best performer and the country that has improved the most on this dimension, thanks to the clear recognition of SMEs in recently adopted environmental policies, as well as to the introduction of dedicated financial support instruments for SME greening.

Figure 9.9. SMEs in a green economy, dimension scores

Note: See the “Policy framework, structure of the report and assessment process” chapter and Annex A for information on the assessment methodology.

Environmental policy frameworks rarely address SME specificities

This first sub-dimension evaluates the introduction of greening initiatives in the policy framework for SMEs. It examines whether strategic enterprise and innovation policy documents cover eco-efficiency and eco-innovation, and the extent to which SMEs are explicitly reflected as a target group.

Table 9.9. Policy frameworks for greening SMEs, sub-dimension scores

|

Armenia |

Azerbaijan |

Georgia |

Moldova |

Ukraine |

EaP average |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sub-dimension scores |

2.89 |

2.82 |

3.57 |

3.70 |

2.44 |

3.08 |

|

Planning and design |

3.00 |

3.00 |

4.32 |

3.40 |

3.62 |

3.47 |

|

Implementation |

3.00 |

3.16 |

3.16 |

4.00 |

1.83 |

3.03 |

|

Monitoring and evaluation |

2.45 |

1.73 |

3.18 |

3.55 |

1.73 |

2.53 |

Note: CM stands for comparable methodology. See the “Policy framework, structure of the report and assessment process” chapter and Annex A for information on the assessment methodology.

This round of SBA assessment reveals how all EaP countries acknowledge the importance of supporting green economic growth in high-level planning documents, a sign that environmental concerns are becoming more salient as governments in the region join the global trend to mitigate the causes and adapt to the effects of climate change. However, the focus on SMEs in such strategic documents remains rather limited. Only Georgia, Moldova and, to a lesser extent, Armenia include specific provisions for SMEs in their strategic policy documents. Moldova’s national development strategy “European Moldova 2030”, clearly stipulates greening SMEs as a priority through the creation of green jobs and the promotion of eco-innovations and eco-labelling for products and services offered by SMEs. Georgia included the “Development of the Green Economy for SMEs” as one of the seven strategic directions of its ongoing SME Development Strategy 2021-2025, with specific actions to develop eco-tourism, eco-innovation and access to green finance. Other EaP countries lag behind in this respect, with no clear mention of SME-related initiatives or measurable targets in their strategic policy documents. While it may be worth noting that some of the countries (Azerbaijan) have adopted green economy policies that will affect SMEs, they do not specifically target this segment of the enterprise population and therefore risk overlooking their specific size-related barriers and needs to improve SME environmental performance.

On the implementation side, SME agencies in the EaP region typically do not engage in the promotion of greening initiatives, and the ministries responsible for environmental issues tend to minimise outreach to SMEs. As a result, SME considerations in overall guidance and support on environmental policy for businesses remain limited, and often left to sectoral business associations. The only exception in this regard is Moldova, where ODA, the local SME agency, has assumed a strong role in promoting greening practices directly to entrepreneurs (see the next section). Furthermore, most countries have not committed significant budgets to supporting the greening of SMEs, and many programmes and initiatives remain heavily reliant on donor funding.

Finally, monitoring and evaluation persists as the weakest area of this sub-dimension for almost all the countries. The generalised lack of SME-specific activities and targets in environmental policy documents means that governments do not commit to look at the effects of their policies on the SME sector, and even when there are SME-specific policy actions (such as in Georgia and Moldova), the focus is on monitoring implementation rather than on impact evaluation. This is also because all countries have very limited statistical production of outcome-oriented environmental indicators, which is a prerequisite to track progress of SME environmental performance at the national level.

Incentives and instruments for green SMEs remain rare, but all countries have made some progress

The second sub-dimension considers the various tools and instruments in place to support SMEs in their greening efforts. It particularly explores whether governments provide regulatory and financial incentives to SMEs, whether there is any evidence that SMEs benefit from those incentives, and how such support schemes are structured and delivered.

Table 9.10. Incentives and instruments, sub-dimension scores

|

Armenia |

Azerbaijan |

Georgia |

Moldova |

Ukraine |

EaP average |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sub-dimension scores |

2.54 |

2.40 |

3.14 |

3.60 |

2.92 |

2.92 |

|

Planning and design |

3.61 |

2.39 |

3.50 |

4.39 |

3.55 |

3.49 |

|

Implementation |

2.39 |

2.58 |

3.36 |

2.82 |

2.85 |

2.80 |

|

Monitoring and evaluation |

1.00 |

2.00 |

2.00 |

4.00 |

2.00 |

2.20 |

Note: See the “Policy framework, structure of the report and assessment process” chapter and Annex A for information on the assessment methodology.

Traditionally an area of weak performance due to the regulatory focus on large polluters and a generalised lack of SME-specific financial incentives, this sub-dimension records some progress for all countries since the previous SBA assessment, although the reasons for this trend vary.