This chapter presents the increasing role of the centre of government (CoG) in anticipating, preparing for and managing crises. This challenging role requires the CoG to assist the government in making rapid and well-informed decisions while balancing trade-offs. The chapter discusses specific practical examples of the CoG anticipating future disruptions through foresight and risk assessment and preparing for the future by learning from the past. It then presents the role the CoG must play in whole-of-government co-ordination during crises, supporting crisis response across new institutional arrangements and frameworks. Finally, it discusses the CoG’s support in engaging with external stakeholders during crises, including scientific advice, involving broader external stakeholders such as citizens, non-governmental organisations and the private sector, and supporting public communications.

Steering from the Centre of Government in Times of Complexity

7. Anticipating, preparing for and managing crises

Abstract

Key messages

The increasing complexity and volatility of global contexts have raised expectations for centres of governments (CoGs) to anticipate, prepare for and manage crises. Some have set up a dedicated unit or team at the CoG to support crisis management since the COVID-19 pandemic.

CoGs recognise the growing challenge of their role. They must assist governments in making rapid and informed decisions while balancing trade-offs against a backdrop of uncertainty. Furthermore, governments often acquire new powers during crises and CoGs must ensure this is handled carefully.

The use of foresight and scenarios to anticipate future developments is an increasingly important aspect of preparing for future crises and is slowly gaining popularity across CoGs.

Engaging with citizens and external stakeholders is crucial during times of crisis. External partners, including the scientific community, often possess specialised expertise and knowledge that prove valuable in addressing complex and rapidly evolving crises.

CoGs play a vital role in communications. Ensuring trustworthy and coherent messaging, particularly considering the rise of misinformation, is an important yet challenging task.

Considerations include equipping CoGs with the necessary capacities to respond during crises while also building their agility and resilience to future disruptions. CoGs must carefully consider appropriate engagement and communications to maintain trust and integrity during crises.

1. Introduction

The management of crises and swift reaction to disruptions are core government competencies. During times of crisis, whether it be a natural disaster, terrorist attack, pandemic or an event we have not yet considered, citizens turn to the government for leadership. Trust in the government is crucial during these periods, as evidence suggests it facilitates swift compliance with policy measures necessary to minimise the impact on society (Brezzi et al., 2021[1]). For instance, pre-pandemic levels of trust influenced compliance with containment policies during the first wave of COVID-19. While governments did benefit from initial popular support, this was not long-lasting.

CoGs play a crucial role in crisis management by providing political leadership and a central point of co‑ordination for decision-making during times of crisis (Figure 7.1). CoGs are increasingly involved in anticipating and managing crises, with 85% of CoGs reporting that risk management and anticipation are a priority for them (OECD, 2023[2]). To support this growing function, 42% of countries have set up a dedicated unit or team at the CoG to support crisis management. By providing political leadership and a central point of co‑ordination, CoGs can contribute to the efficient management of crises and the implementation of necessary measures. Their involvement also helps maintain public trust.

Figure 7.1. CoGs play a crucial role as a central point of co-ordination during crises

Source: Author’s own elaboration.

The changing nature of the crises themselves complements their intensity. For instance, the COVID-19 pandemic had two amplifying characteristics compared to natural disasters: a rapid global spread and multidimensionality not only in terms of prevention and management of health risks but through spill-over effects to many other crucial areas, including the economy, society and trust in government and democratic institutions. Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine has brought similar effects, as the security threat is compounded by impacts to the energy sector, for example. Over the last three years, CoGs have taken on further responsibilities to address the challenges posed by current crises. In 85% of the surveyed countries, CoG activities related to crisis management have increased mainly through the development of ad hoc taskforces or groups to deal with short-term issues (OECD, 2021[3]).

This chapter will explore the CoG’s role and activities as a stabiliser during times of crises through the following structure:

Anticipating and preparing for future crises.

Whole-of-government co-ordination and crisis management.

Engaging with external stakeholders during crises.

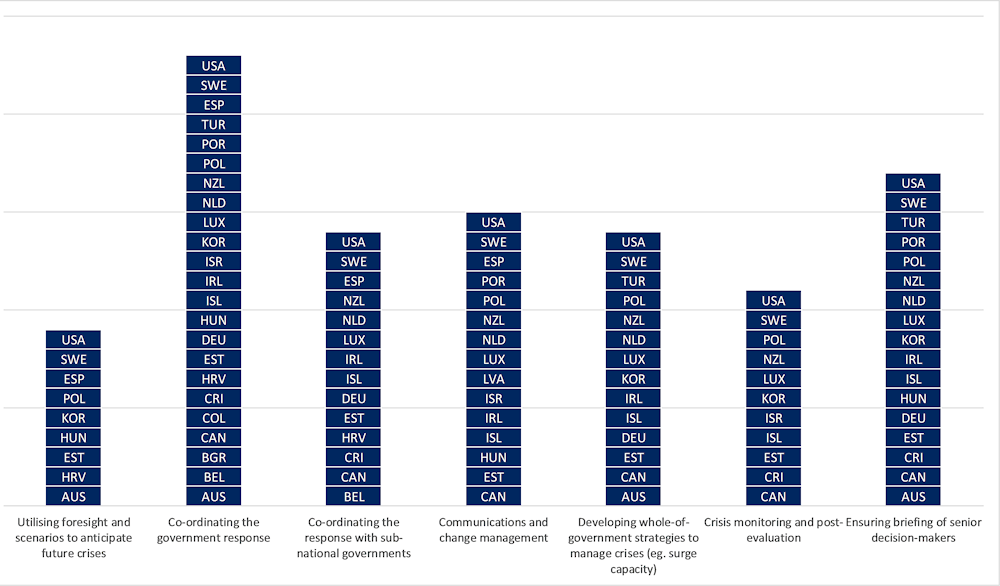

Figure 7.2. The role of the CoG in crisis anticipation, preparedness and management

Note: n=26. Respondents to the OECD survey were asked: “What is the role of the CoG in preparing and managing crises?”.

Source: OECD (2023[2]), “Survey on strategic decision making at the centre of government”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

2. Anticipating and preparing for future crises

Anticipating future disruptions

Countering multi-dimensional crises has increased the relevance of strategic foresight and national risk assessments. The OECD Recommendation of the Council on the Governance of Critical Risks recommends that adherents to “develop risk anticipation capacity linked directly to decision-making through the development of capacity for horizon scanning, risk assessments” (OECD, 2014[4]).

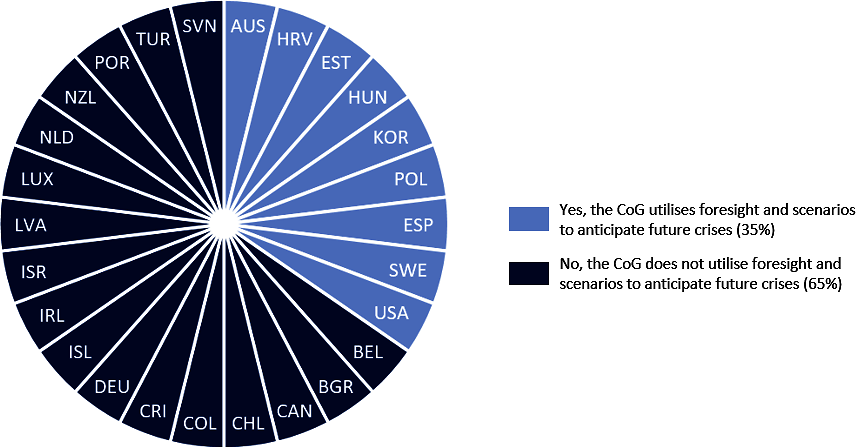

Finland, Ireland, and Luxembourg all have examples of such capacities at the centre (including national risk assessments). Some CoGs (Figure 7.3) have dedicated foresight units to assess critical risks and anticipate future crises. Box 7.1 outlines Finland’s national foresight system.

Figure 7.3. The CoG’s use of foresight and scenarios to anticipate future crises

Note: n=26. Respondents to the OECD survey were asked: “What is the role of the CoG in preparing and managing crises? [Utilising foresight and scenarios to anticipate future crises]”.

Source: OECD (2023[2]), “Survey on strategic decision making at the centre of government”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

Box 7.1. Finland: Using foresight from the centre for anticipating the future

Finland’s national foresight system includes a Government Report on the Future co‑ordinated by the Prime Minister’s Office with inputs from key stakeholders. The report forms the basis for dialogue on the future in the government and parliament and aims to identify issues that will be important for decision-making and require special attention in the future. The report has a high-level steering group with five state secretaries.

The Committee for the Future was established in 1993 by the parliament of Finland. It is a key forum for raising awareness and discussing long-term challenges related to futures in Finland. The prime minister represents the executive in the Committee of the Future, which draws members from across all parliamentary parties and thus helps to diffuse the knowledge about future risks and disruptions. The committee prepares the parliament’s response to the Government Report on the Future every four years. The Prime Minister’s Office co-ordinates the Government Foresight Group which brings together strategic foresight experts. The group serves as an advisory body in the preparation of the Government Report on the Future and the ministries’ futures reviews.

Source: OECD (2021[5]), Policy Brief - Towards a Strategic Foresight System in Ireland, https://oecd-opsi.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Strategic-Foresight-in-Ireland.pdf; OECD (2022[6]), Anticipatory Innovation Governance Model in Finland: Towards a New Way of Governing, https://doi.org/10.1787/a31e7a9a-en (accessed on 5 September 2023).

Being prepared for future crises by learning from the past

To anticipate future crises and prepare accordingly, foresight approaches should be complemented by learning from the past. The 2021 OECD Survey on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions found that, on average, across countries, 49.4% of respondents expressed confidence that their government would be prepared to protect people’s lives in the event of a new pandemic (OECD, 2022[7]). The COVID-19 pandemic showed that governments that drew on lessons learnt from past crises often demonstrated greater resilience (OECD, 2014[4]). The countries where most people believe that their government has learnt from the pandemic are also the countries where a higher number of people are likely to have trust in that government. Box 7.2 offers one example from Korea on how it integrated past learnings into the management of COVID-19.

Box 7.2. Learning from previous crises and rooting new practices in Korea

Korea’s response to COVID-19 demonstrated the value of the institutional capacity to analyse lessons from previous crises and root new practices to be better prepared for the future. After the 2015 MERS coronavirus outbreak in Korea, the government enacted 48 reforms to boost public health emergency preparedness. These included guidelines for screening facilities, comprehensive testing and contact tracing, and supporting people in quarantine to make compliance easier (Kim et al., 2021[8]). These systems helped to quickly contain the spread of COVID-19 and allowed economic and social activities to resume earlier than in many other OECD countries.

Source: OECD (2021[3]), Government at a Glance 2021, https://doi.org/10.1787/1c258f55-en.

3. Whole-of-government co-ordination and crisis management

CoGs play an important role by supporting decision-making and co‑ordination across government agencies (OECD, 2020[9]) during times of crisis. The OECD Recommendation of the Council on the Governance of Critical Risks recommends that adherents to “put in place governance mechanisms to co-ordinate on risk management and manage crises with government” (OECD, 2014[4]).

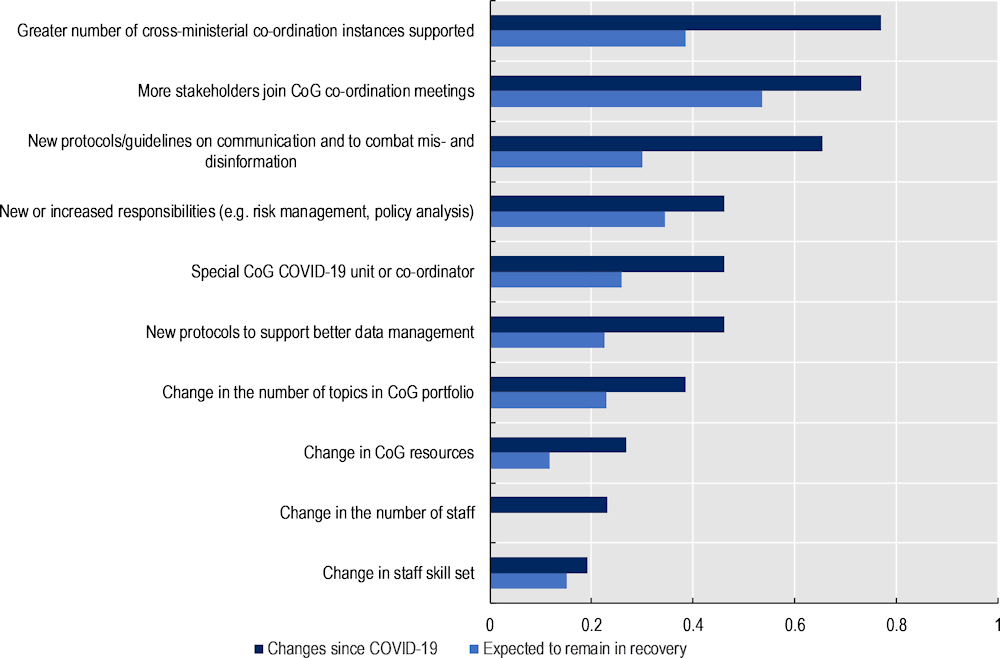

In the event of a crisis, CoGs most commonly focus on the management and co-ordination of government operations (OECD, 2018[10]). Following the COVID-19 pandemic, 85% of CoGs now highlight risk management as one of their priorities and 88% report that it is the CoG’s role to co‑ordinate the government’s response to a crisis (OECD, 2023[2]). Almost half of OECD governments deployed new institutional arrangements to manage the pandemic, either in the form of a dedicated unit or an appointed co-ordinator (OECD, 2020[9]) and many CoGs assumed new responsibilities since COVID-19 (Figure 7.4). In Luxembourg, for instance, the composition of the crisis unit in charge of COVID-19 had to evolve slightly twice to adapt to the scale of the pandemic (OECD, 2022[11]). An example of Belgium’s approach from the centre of government, and an example of an evolving framework for managing crises can be found in Australia (Box 7.3).

Box 7.3. Crisis responses in Belgium and Australia

Belgium’s crisis management approach to COVID-19

Following the declaration of the federal phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, the federal government of Belgium became officially in charge of co-ordinating the crisis response. Between March 2020 and October 2020, crisis response was co-ordinated by the National Security Council, which was led by the Prime Minister and to which the Minister Presidents of the federated entities were invited. This phase saw the creation of ad hoc structures seeking to assist the executive in tackling this new virus. From October 2020 until March 2020, the crisis was mainly led by the Concertation Committee, a body in which the Prime Minister and the Minister Presidents hold equal decision-making power. This phase also saw the creation of a Corona Commissariat, which sought to clarify the overall governance structure and centralise the crisis response in a single delivery unit.

Belgium has a National Risk Assessment process in place. Yet, opportunities exist for Belgium to raise awareness of the assessments across government and society, and to increase the use of the assessments in informing policy and decision-making.

Australia’s cross-government framework on managing the crisis and recovery.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic and multiple natural disasters, Australia has recognised the need to evolve its approach to dealing with crises. The country has developed a simple and clear cross-government crisis management framework that is regularly updated based on future needs and lessons learnt from the previous crisis. It includes the ability to respond through shifts, for example, utilisation of surge reserves, enabling allocation of additional staff in case certain institutions require it during times of emergency.

The overall framework prescribes criteria when crisis management duties move up to the prime minister (and the CoG). It also defines political and administrative responsibility in various types of crises, from cyberattacks to energy crises and natural disasters. Distinct definitions of crisis areas are further complemented with a clear definition of responsibility.

Sources: Australian Government (2021[12]), Australian Government Crisis Management Framework (AGCMF), https://www.pmc.gov.au/publications/australian-government-crisis-management-framework-agcmf (accessed on 7 September 2023), (OECD, 2023[13]), Evaluation of Belgium’s COVID-19 Responses, https://doi.org/10.1787/990b14aa-en.

Figure 7.4. Changes in CoGs during COVID-19 and recovery planning

Note: Responses from 26 OECD countries: Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Colombia, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Korea, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Mexico, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Sweden and the Republic of Türkiye.

Sources: OECD (2021), Government at a Glance 2021, OECD Publishing, Paris, https:/doi.org/10.1787/1c258f55-en.

The CoG must be agile and responsive to take on its often-increased role adequately during crises. For instance, in Poland, the prime minister has been granted spending authority for special-purpose aid funds both during the COVID-19 pandemic and to provide assistance to Ukraine and Ukrainian refugees. Box 7.4 provides an example of how Romania’s CoG was brought in to co‑ordinate the large-scale response to the refugee crisis following Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Box 7.4. Stewarding and guiding cross-cutting policies in a time of crisis, Romania

Romania was emerging from the COVID-19 crisis that had already pushed the country’s social and economic limits when the war in Ukraine commenced. Over 3 million Ukrainians crossed the borders into Romania, resulting in immediate emergency response needs, as well as medium- to long-term priorities around inclusion and safety.

The Chancellery responded rapidly to this cross-cutting issue through a whole-of-government effort, including collaborating with key stakeholders on a national plan. Romania established a clear decision-making and co‑ordination structure to enable agencies with different responsibilities at all levels of government to plan, co‑ordinate and interact effectively at the policy level and on the ground in response to the crisis. These included the establishment of a working group (Strategic Humanitarian Coordination Group) at the CoG. The CoG also helped to ensure coherence across the global stage.

Source: Information from the Chancellery of Romania.

4. Engaging with external stakeholders during crises

Scientific advice during crises

CoGs provide direct support and advice to heads of government and the council of ministers or cabinet and facilitate cabinet decision-making. In a clear majority of countries (65%), the CoG is responsible for ensuring the briefing of senior decision-makers in times of crisis (OECD, 2023[2]). A key challenge for them is to ensure the incorporation of impartial, trusted evidence at speed. In this context, CoGs are increasingly acknowledging the importance of bringing in scientific, impartial advice during crises (OECD, 2021[3]). In many cases, CoGs started to rely more on expertise provided by scientific advisory committees, taskforces or expert groups, with some created on an ad hoc basis, while others pre-dating the pandemic. For example, in Poland, advanced data analysis techniques were used by experts from universities and research centres for forecasting purposes during the pandemic. Many of these committees report to the CoG, for example in Australia, where the scientific medical advice answered to the Ministry of Health and the Prime Minister’s Office. Boxes 7.5 and 7.6 outline examples from Poland and the United Kingdom on the use of external or scientific bodies for decision-making at the CoG. Other countries such as Luxembourg, Spain and Switzerland have also created scientific bodies to provide advice to government.

Box 7.5. The Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies, United Kingdom

The Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) in the United Kingdom is a critical body of expert scientists and researchers convened during times of crises, particularly public health emergencies such as pandemics. Established to provide evidence-based advice to the government and ensure that timely and co-ordinated scientific advice is made available to decision-makers, SAGE plays a pivotal role in shaping the nation’s response strategies. Who participates in SAGE meetings depends on the nature of the emergency and the issues under consideration and members are drawn from government, academia and the private sector. SAGE assesses data, conducts research and offers recommendations to inform government decisions, thereby helping to guide policies related to the ongoing crisis. SAGE’s contributions in the face of challenges like the COVID-19 pandemic highlight its essential role in providing rigorous scientific insights to support effective crisis management and safeguard public health.

Source: OECD (2021[3]), Government at a Glance 2021, https://doi.org/10.1787/1c258f55-en.

Box 7.6. The Centre for Eastern Studies, Poland

The government-funded think tank, the Centre for Eastern Studies (OSW), established in 1990, provides the CoG with in-depth expertise and analysis. The OSW is a public institution funded by the government of Poland, and its wide-ranging policy portfolio includes research on several pressing international topics of importance to the Polish government, for example through timely policy advice on the international implications of challenges caused by Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine. The OSW serves as a source of analysis, expert opinion and expertise in forecasting for Poland.

The OSW demonstrates the value that flexible sources of expertise can offer to the CoG in times of crisis when already well integrated into CoG processes. An expert unit with strong links to the centre of government (i.e. direct subordination to the prime minister and funding by the Prime Minister’s Office) can immediately become part of the decision-making and advisory processes for the management of crisis situations under the CoG’s responsibility. This institutional setup avoids requiring the creation of new structures in the CoG, instead focusing on the agility and responsiveness of an existing unit to make rapid decisions based on deep analysis. The permanent source of knowledge that the OSW offers the CoG in Poland is a valuable tool, particularly during crises, eliminating the frequent trade-off between timely and high-quality expertise.

Source: Information provided by representatives of the Government of Poland; OSW (n.d.[14]), About Us, https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/o-nas (accessed on 1 December 2023).

Leveraging broader external stakeholders

Engaging with external stakeholders is also important during times of crisis. External partners, such as citizens, non-governmental organisations and the private sector, often possess specialised knowledge that is valuable in crises (OECD, 2018[15]). Collaboration with these stakeholders can also foster transparency and trust, building individuals’ capacity to act in times of crisis (OECD, 2014[4]).

Most (77%) CoGs consulted stakeholders on the design of COVID-19 response strategies but only 35% actively involved stakeholders in their design (OECD, 2021[16]). This could be due to governments prioritising speed over transparency and oversight.

CoGs also need to consider how they engage with different levels of government. Depending on the governance structure, many crisis management functions are fulfilled by local authorities. Most CoGs (14 out of 26) are responsible for co‑ordinating crisis responses with subnational governments. Box 7.7 outlines Latvia’s engagement mechanism with these actors during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Box 7.7. Involving various levels of government and external stakeholders in crisis management in Latvia

In Latvia, there was a recognition of the need to involve a wide range of stakeholders as well as all levels of government when dealing with crises. A new COVID-19 Crisis Recovery Strategic Group was established. Led by the prime minister, the group was composed of the Association of Local and Regional Governments, the Academy of Sciences, the Employers’ Confederation, the Chamber of Commerce and Industry and the National Trade Union Confederation, among others. Importantly, it also included civil society through a representative nominated by the Memorandum Council. It also involved the parliament to ensure it supported the highest level of decision-making.

Source: OECD (2021[3]), Government at a Glance 2021, https://doi.org/10.1787/1c258f55-en.

Some CoGs also adopted more innovative approaches to engaging with citizens and stakeholders during times of crisis (for example, utilising digital platforms or innovation challenges). Box 7.8 outlines one example from Estonia, which utilised a hackathon approach to try to better deal with the pandemic.

Box 7.8. Triggering grassroot innovation with Hack the Crisis, Estonia

The challenges produced by the COVID-19 crisis constituted a shock to governments worldwide. Estonia has faced rapidly increasing infection rates, especially in certain hotspots. The government acknowledged that it did not have all of the answers and that new ideas and collaboration were essential to respond to the crisis as effectively as possible, and thus ran a Hack the Crisis event to gain ideas.

The central innovation institution Accelerate Estonia was charged with leading these efforts. Accelerate Estonia partnered with Estonian non-profit Garage48 to kick off the virtual hackathon just a few hours after it was approved. The government offered a cash prize of EUR 5 000 for each of the top 5 ideas to help the teams behind them further develop the concepts. Start-ups also contributed support packages, such as co-working spaces providing resources for the winners.

By the end of the hackathon 2 days later, 96 ideas had been proposed by over 1 000 participants. Many of the actions added positive outcomes and some are still used today.

The success of Hack the Crisis in Estonia and its significant following on Twitter through #HacktheCrisis sparked a global movement replicating the structure and approach around the world. More than 60 countries have held their version of Hack the Crisis, which was further evolved into a Global Hack initiative.

Source: OECD (2020[17]), Embracing Innovation in Government: Global Trends 2020, https://trends.oecd-opsi.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/OECD-Innovative-Responses-to-Covid-19.pdf (accessed on 11 September 2023).

Public communication

Effective public communication by the CoG in times of crisis is key. CoGs play a crucial role in disseminating clear, consistent and transparent information to the public, building trust and mitigating panic. This is increasingly more critical in the fight against dis- and misinformation (OECD, 2020[18]; 2020[19]). Finally, it can help reach specific segments of the population and facilitate dialogue with citizens who may be marginalised.

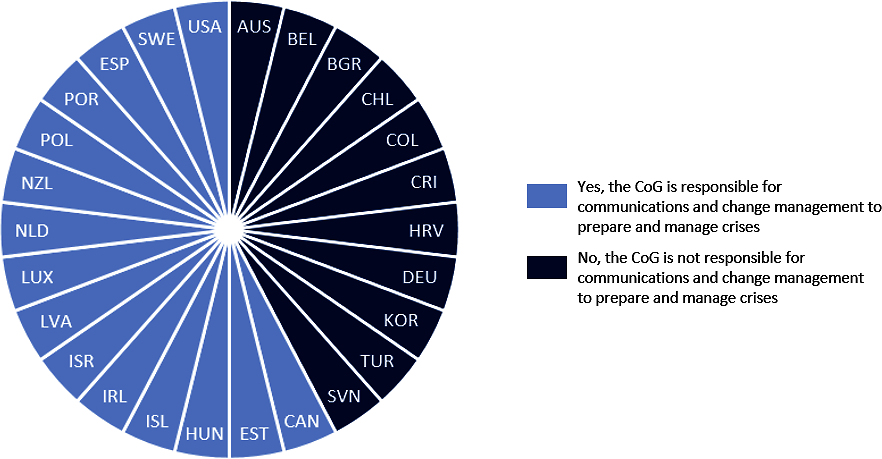

Responses to the OECD’s survey on strategic decision-making at the centre of government show that more than half of CoGs (58%) assume responsibilities related to communications and change management in times of crises (see Figure 7.5) (OECD, 2023[2]). During the COVID-19 pandemic, most CoGs adopted new protocols and guidelines to combat mis- and disinformation (Figure 7.4).

Figure 7.5. The CoG’s responsibility for communications and change management in times of crisis

Note: n=26. Respondents to the OECD survey were asked: “What is the role of the CoG in preparing and managing crises? [Communications and change management]”

Source: OECD (2023[2]), “Survey on strategic decision making at the centre of government”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

CoGs are working to make their messages and contents more compelling and adapted to specific or vulnerable segments of the population, including the use of social media (OECD, 2015[20]) (for example, countries like Australia, New Zealand and others utilised social media for public communication).

A good example is the United Kingdom’s Government Communication Service, which also brought in citizens’ insights during the pandemic. The service created a daily insights and evaluation dashboard for public communicators across the government. It summarises data collected through focus groups and surveys measuring public mood, trending topics and the state of public opinion on government measures. Similarly, the Finnish Prime Minister’s Office, in collaboration with the National Emergency Supply Agency and the private sector, has been working with social media influencers to provide clear and reliable information.

Clear language and the customisation of communication material have also proven effective in sharing complex information with different segments of the population. Disseminating information in more than one language to reach specific groups has also been observed in CoGs, such as in Belgium, where key messages were translated into nine languages. Several other CoGs, such as those in France and the United Kingdom, have promoted specific video, audio and written material.

5. Common challenges and enablers

Through the synthesis of information collected through country practices, desk research, interviews and the experiences shared by participants of the OECD informal Expert Group on Strategic Decision Making at the Centre of Government, the following key considerations can be identified.

Common challenges

One consideration for CoGs as they gain greater responsibilities during times of crisis is matching this with the right resources and capabilities. While many CoGs assumed new responsibilities during the COVID-19 crisis, in most cases, these increased responsibilities did not come with additional resources. Only 27% of CoGs experienced a change in the financial resources available to them, and only 23% had a change in staffing levels.

CoGs are often given additional decision-making powers during crises, which can create sensitivities and make it harder for citizens and stakeholders to understand and engage with the crisis management structures. CoGs need to balance these powers with well-defined structures that give due consideration to the needs of all of society, while maintaining trust and integrity in government decision-making.

A key challenge for CoGs is how to rapidly bring in trusted and impartial advice into decision-making while ensuring timely and accurate information is provided to the public. This challenge has been exacerbated by the effects of misinformation and disinformation.

Key enablers

CoGs can mobilize their national risk assessment process and complement it with a range of strategic foresight approaches to feed into strategic planning and crisis preparation. These include conducting scenario planning, horizon scanning, trend analysis, and debates on alternative futures with both policymakers and stakeholders. It is important to ensure that key institutions responsible for democratic accountability, such as parliaments and federated entities, are involved in assessments, and that these processes inform policy and decision-making.

CoGs could consider leveraging digital and data technology to engage with a broader audience and leverage knowledge from across the whole of society. It is important for CoGs to make use of trusted channels to communicate and engage citizens and stakeholders, both when preparing for crises, as well as when dealing with them.

CoGs may need to consider increasing oversight and accountability mechanisms for crisis management, for example through greater use of Parliamentary oversight, specialized commissions of inquiry, or audits conducted by Supreme Audit Institutions.

CoGs can utilize their coordination capacities to bring together different government bodies, scientific experts, and external partners in decision-making approaches. CoGs can utilize their central positioning to help ensure consistent, accurate, and trusted communication to the public and across all levels of government. In cases where CoGs lead such communications, they should pay attention to communication with vulnerable groups and minorities.

It is important to learn from crises, and CoGs can strengthen their crisis preparedness by ensuring there is a structured process for continually improving their capabilities. They could further leverage monitoring and post-crisis evaluations to learn from both ongoing (especially relevant for protracted crises like the COVID-19 pandemic) and from past crises (including those that happen in their country and further afield).

References

[12] Australian Government (2021), Australian Government Crisis Management Framework (AGCMF), https://www.pmc.gov.au/publications/australian-government-crisis-management-framework-agcmf (accessed on 7 September 2023).

[1] Brezzi, M. et al. (2021), “An updated OECD framework on drivers of trust in public institutions to meet current and future challenges”, OECD Working Papers on Public Governance, No. 48, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b6c5478c-en.

[8] Kim, Y. et al. (2021), “Interorganizational coordination and collaboration during the 2015 MERS-CoV response in South Korea”, Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, Vol. 15/4, pp. 409-415, https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2020.32 (accessed on 11 September 2023).

[13] OECD (2023), Evaluation of Belgium’s COVID-19 Responses: Fostering Trust for a More Resilient Society, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/990b14aa-en.

[2] OECD (2023), “Survey on strategic decision making at the centre of government”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

[6] OECD (2022), Anticipatory Innovation Governance Model in Finland: Towards a New Way of Governing, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/a31e7a9a-en (accessed on 5 September 2023).

[7] OECD (2022), Building Trust to Reinforce Democracy: Main Findings from the 2021 OECD Survey on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions, Building Trust in Public Institutions, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b407f99c-en (accessed on 27 February 2023).

[11] OECD (2022), Evaluation of Luxembourg’s COVID-19 Response: Learning from the Crisis to Increase Resilience, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/2c78c89f-en.

[3] OECD (2021), Government at a Glance 2021, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1c258f55-en.

[5] OECD (2021), Policy Brief - Towards a Strategic Foresight System in Ireland, OECD, Paris, https://oecd-opsi.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Strategic-Foresight-in-Ireland.pdf.

[16] OECD (2021), “Survey on building a resilient response: The role of centre of government in the management of the COVID-19 crisis and future recovery efforts”, OECD, Paris, https://qdd.oecd.org/subject.aspx?Subject=GOV_COG_2021.

[9] OECD (2020), “Building resilience to the Covid-19 pandemic: The role of centres of government”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/building-resilience-to-the-covid-19-pandemic-the-role-of-centres-of-government-883d2961/.

[18] OECD (2020), “Combatting COVID-19 disinformation on online platforms”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/combatting-covid-19-disinformation-on-online-platforms-d854ec48/ (accessed on 6 September 2023).

[17] OECD (2020), Embracing Innovation in Government: Global Trends 2020, OECD, Paris, https://trends.oecd-opsi.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/OECD-Innovative-Responses-to-Covid-19.pdf (accessed on 11 September 2023).

[19] OECD (2020), “Transparency, communication and trust: The role of public communication in responding to the wave of disinformation about the new Coronavirus”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/building-resilience-to-the-covid-19-pandemic-the-role-of-centres-of-government-883d2961/#section-d1e1596 (accessed on 6 September 2023).

[15] OECD (2018), Assessing Global Progress in the Governance of Critical Risks, OECD Reviews of Risk Management Policies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264309272-en (accessed on 7 September 2023).

[10] OECD (2018), Centre Stage 2: The Organisation and Functions of the Centre of Government in OECD Countries, OECD, Paris, https://web-archive.oecd.org/2021-05-18/588642-report-centre-stage-2.pdf (accessed on 19 May 2020).

[20] OECD (2015), The Changing Face of Strategic Crisis Management, OECD Reviews of Risk Management Policies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264249127-en.

[4] OECD (2014), Recommendation of the Council on the Governance of Critical Risks, OECD, Paris, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0405 (accessed on 4 September 2023).

[14] OSW (n.d.), About Us, Centre for Eastern Studies, https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/o-nas (accessed on 1 December 2023).