This chapter presents the role of the centre of government (CoG) as a bridge between the political and administrative interface. Specifically, in bridging the relationship between administrative officials and the elected government, the CoG’s relationship-building abilities will be discussed. It explores various practical examples of how the CoG manages this important relationship during times of major global challenges and polarisation through deploying different mechanisms. It details the importance of clear responsibilities, a well-equipped workforce and specific mechanisms to translate political priorities into coherent and co‑ordinated action to drive trust in public institutions. It further discusses the complexities for CoGs in managing the challenges of transitions and coalition governments at the interface.

Steering from the Centre of Government in Times of Complexity

1. Bridging the political-administrative interface

Abstract

Key messages

The centre of government (CoG) often plays a particularly important role in bridging the relationship between administrative officials and the elected government.

The CoG supports the agenda and running of cabinets and cabinet committees, is responsible for translating and overseeing the implementation of government programmes and plays a central role in managing government transitions.

Navigating this role is particularly challenging, especially when managing major global challenges and crises alongside national agendas and geopolitical shifts.

CoG officials should be skilled at building trust with political actors through impartial and evidence-based advice. Further, the CoG should be a safe environment in which frank and fearless advice can be given, allowing for the consideration of multiple trade-offs.

Key areas for consideration include ensuring a clear understanding of the roles and responsibilities between the administrative and political interface, using the right mechanisms to translate political priorities into action and building the skills of administrative officials.

The CoG’s role as a bridge between the administrative and political interface will be subject to various contextual aspects of the system of government, including political cycles, coalition governments, etc.

1. Introduction

Democracy is inherently messy and requires trade-offs and compromises. Helping navigate this, through bridging and fostering relationships between the political and administrative layers of government, is a key role of the CoG. Centres perform this work to translate government agendas into whole-of-government strategies to help governments work on complex issues and make policy trade‑off decisions (OECD, 2018[1]). It is essential for both domestic and global policy, and responses to complex and layered geopolitical issues (Cairney, 2012[2]).

The CoGs’ bridging role is critical to ensuring coherent and co‑ordinated government action and smooth transitions and decision-making. In this sense, CoGs function to ensure that the public administration upholds and implements government’s priorities in a way that follows the principles of openness, integrity and fairness. In doing so, CoGs can influence the overall perception of government competency and values, which drive trust in public institutions (Brezzi et al., 2021[3]). The complex issues and geopolitical shifts currently facing many governments make this role even more challenging.

This chapter will explore the role of the CoG as a bridge and an interface between the political and administrative spheres of government through the following structure:

The political-administrative interface.

Mechanisms used by the CoG as a bridge.

Building the skills of CoG officials at the interface.

Managing challenges at the interface, including coalition governments and transitions.

2. The political-administrative interface

A shared understanding of the delineation of roles between the political and administrative spheres and between the CoG and line ministries is essential. In most democratic systems, the political sphere holds primary policy decision-making authority, while the administrative sphere operates on behalf of the government in operational and related matters (Favero, 2022[4]). Yet, relationships between the political and the administrative can be challenging due to distinct cultures, competing objectives, forms of accountability and power. Under many democratic systems, politicians have the authority to decide policy that shapes action. The public administration can be bound to implement the wishes of the elected government but retains power over information and organisational resources (Vigoda-Gadot and Mizrahi, 2014[5]). Yet, a lot more policy design interactions must occur in practice. While clear roles are important, processes must allow both actors to monitor (Vigoda-Gadot and Mizrahi, 2014[5]) and meaningfully interact with the other (Demir, 2022[6]).

Formal agreements, the codification of relationships and roles, or cabinet manuals can be used to clarify roles (Box 1.1).

Box 1.1. Codifying the roles of the political and administrative layers

In Australia, the Public Service Amendment Bill 2023 is working to define the separate roles of the administrative and political layers further. Amongst other important reforms, the bill outlines a means to strengthen a provision in the original 1999 Public Service Act which prohibits ministerial influence on the direction of agency head employment matters. This new bill is intended to renew and strengthen understanding between ministers and agency heads on the apolitical nature of public service appointments. This explicitly reinforces the previous understanding by codifying it, demonstrating continued work in Australia to delineate the roles of the administrative and political spheres of government.

Source: Australian Government (2023[7]), Australian Government Guide to Policy Impact Analysis, https://oia.pmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-05/oia-impact-analysis-guide-march-2023_0.pdf.

Negotiation among both sides of the interface is critical to reaching a common framework and is an important part of the CoG’s role. There is always tension between political and administrative accountability, which blurs the roles of each actor. Balancing goals, autonomy and accountability of ministers with regard to senior public officials is always a careful balance (Giauque, Resenterra and Siggen, 2009[8]; OECD, 2023[9]).

3. Mechanisms used by the CoG to translate political priorities to the administration

One of the primary reasons for CoGs to play a bridging role is to ensure that the public administration implements the government agenda. This involves alignment between strategic priorities, public administration objectives, and institutional, financial or legal capabilities. To bridge potential gaps, act as an interface and effectively translate the political vision into action, CoGs can use several mechanisms. Box 1.2 discusses mechanisms used in Australia, Denmark, Finland and Hungary. The most common mechanisms which emerge from these examples include:

Joint consideration of objectives between the line ministries and CoG.

Performance work which anchors government priorities.

A detailed articulation of strategies.

An agreement to proceed (e.g. memorandum of understanding).

Box 1.2. Translating the government agenda to the public administration through the CoG

Australia

In Australia, strategic government priorities are reflected throughout the public administration by tying them to the performance framework. The CoG, from a whole-of-government perspective, makes this a planning and reporting priority. The performance framework establishes roles, performance expectations, reporting and communication channels that prioritise responsiveness to the minister and align planning with the goals of the government in power.

This approach is more top-down, which reflects the fact that all ministers belong to the same party. However, this mechanism lacks the opportunity for the two-way negotiation present in the Danish and Finnish examples. This can create a greater need for critical discussions during each policy or event cycle.

Hungary

The CoG in Hungary – the Prime Minister’s Office – plays a crucial role in bridging the gap between political leadership and the civil service. The office can co‑ordinate and streamline policy initiatives to ensure alignment with overall government goals and priorities. The main political co‑ordinator of the government is the Cabinet Office of the Prime Minister, which establishes clear and open lines of communication. This helps the administration’s programme of work by clearly conveying the expectations, guidelines or any changes to government policy from a high level within the government.

Denmark

In Denmark, “settlement” agreements regarding Danish policies are used between the CoG, ministers and external parties. While the government sets the overall direction and priorities for Denmark’s European Union (EU) policy, parties outside the government take part in negotiations to develop the overall guidelines for future EU policymaking.

The government develops the course of the policy, which is called the “settlement”. For this proposed course to take effect, all parties involved in drafting the agreement must agree to the policy. If the parties dispute a proposed change, it cannot take place until after a parliamentary election.

Finland

A government programme is negotiated and agreed to by all ministers. They ensure the alignment of each line ministry with the broader government aims. The state secretary assists in drafting policy outlines, conducting inter-ministerial co‑ordination, harmonising policy positions and implementing the government programme in the ministry’s administrative branch.

4. Building the skills of CoG officials at the interface

A key enabler for the CoG to effectively function as a bridge between the political and administrative spheres is a skilled workforce that has good relations with the rest of government. The CoG needs a diverse and well-trained set of staff to achieve successful policy outcomes in a range of areas. Administrators must serve elected governments and yet remain non-partisan. In order to so, CoG staff must be skilled in consistently interpreting, establishing and defending the line between appropriate responsiveness and inappropriate partisanship (Grube and Howard, 2016[10]). Staff should also be skilled mediators to facilitate conversation at the interface.

The CoG also plays a key role in translating the government agenda into public service objectives. Key functions include negotiation, sharing of information, monitoring and fostering commitment. They require communication skills, monitoring expertise and the ability to translate evidence into knowledge.

The CoG also has a central role to play in transition management, as discussed later. This includes record keeping, planning for government changes, sourcing and maintaining live documents that capture performance, long-term plans and strategic outlook and developing information storage systems that are accessible to decision-makers and incoming governments. A CoG best supports this type of work with a variety of staff, including those with specialist information management skills, strategic capacity and deep process understanding of government workings. Generally, the mix of skills required suggests that the CoG benefits from a mixture of political and administrative staff. Box 1.3 outlines Hungary’s approach to ensuring the right skills at the CoG.

Box 1.3. Maintaining a high-performing CoG in Hungary

In recognition of the specific expertise and increasing pressures on the CoG, the government of Hungary implements a range of initiatives to support a high-performing CoG. This includes specialised yearly training for staff and compulsory public administration entry-level examinations and for seniors in managerial-level positions at the University of Public Service to equip them with the skills and knowledge necessary to handle the nuances of central government functions and today’s challenges. This training covers several policy areas and material needed for the professional conduct of a civil servant, so helps maintain the professionalism of the civil service.

5. Managing challenges at the interface: Coalition governments and transitions

Managing relationships through coalition governments

Coalition governments are becoming more prominent for many reasons, including in the context of polarisation and threats to democracy. Coalition governments do not always have relationships or mechanisms to collaborate and function effectively, challenging the CoG’s role. In this context, internal stakeholder management has become increasingly important (Shostak et al., 2023[11]).

Coalition governments may require the CoG to increase focus on central co‑ordination and relationships due to the necessity of maintaining good relationships with all parties. This may also involve sharing co‑ordination powers with line ministries and engaging in discussions outside of the government (OECD, 2018[1]). This can also differ between parliamentary and presidential systems. Boxes 1.4, 1.5 and 1.6 outline cases in Denmark, Finland and Spain, where coalition government arrangements have required the CoG to adapt.

Box 1.4. Finland – Managing CoG functions in a coalition government

In Finland, the government is formed through a coalition between a range of parties. The parties representing the new parliament negotiate a political programme and the composition of the new government, after which the parliament elects the prime minister. The president then appoints the other ministers in accordance with a proposal made by the prime minister.

In this regard, the CoG – the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) – supports the development and agreement of a government programme, which sets out the main tasks facing the incoming administration. Some discussions and decisions can also occur outside of the government and the CoG can be asked for support.

The prime minister is the political leader of the government and is responsible for obtaining agreement and co‑ordinating government work with that of parliament. This includes monitoring the implementation of the programme and is supported by the PMO, plenary sessions, statutory ministerial committees and state secretaries, among others.

Government plenary sessions are held once a week and proposals are made to the president of the republic on matters that come under the authority of the president. They have the power to issue decrees and make decisions on matters under the authority of the government. Division of the government’s decision-making authority between the plenary session and the individual ministries provided for in the constitution, government act and the government rules of procedure.

A state secretary may also be appointed to the PMO. The state secretary is the closest adviser to the prime minister. They direct preparatory work, promote and monitor the implementation of the government programme, manage co‑operation between ministries and may assist ministers in political steering and planning. They also assist and represent the ministers in drafting policy outlines, inter‑ministerial co‑ordination, harmonising policy positions, implementing the government programme in the ministry’s administrative branch, and handling EU and other international duties.

Source: Finnish Government (n.d.[12]), About the Government, https://valtioneuvosto.fi/en/government (accessed on 7 September 2023).

Box 1.5. Denmark: Consensus and co‑operation in a coalition government

With a high incidence of minority government and minority coalitions and a strong focus on consensus and co-operation, Denmark has made use of coalition agreements and strong centralised government co‑ordination using committees to seek consensus for cabinet decisions and a collectively drafted government platform. The prime minister must drive consensus between different parties in government and ensure all relationships to support the coalition are secure. To do this, the prime minister holds many co‑ordinating meetings, both with the leaders of the government parties and with the ministers.

A department comprises permanent and politically neutral civil servants, acts as the secretariat to the minister and performs planning, development and strategic work. Civil servants remain in post upon a change of government. Most civil servants work in agencies that are separate operational organisations reporting to the minister. The minister also has their own secretary and communications personnel who are partisan and do not remain when the government changes.

Each minister holds full executive power and responsibility over their portfolio. The cabinet is not a collective decision-maker. To support these arrangements and reduce the potential for ministerial decisions that are not planned, coalition agreements are used and economic and co‑ordination committees work to resolve conflicts among the parties.

The sitting government sets the direction for Denmark’s EU policy. Parties outside government, however, still take part in negotiations about the overall guidelines for future EU policymaking. The parties in parliament determine the course of Danish EU policy by entering into a settlement agreement. For a Danish policy about the European Union to change, all parties who crafted the original agreement must concur. If the parties dispute a proposed change, it cannot take place until after a parliamentary election.

Source: Danish Parliament (n.d.[13]), The Government, https://www.thedanishparliament.dk/en/democracy/the-government (accessed on 8 September 2023); Christiansen, F. (2021[14]), “Denmark: How to form and govern minority coalitions”, https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198868484.003.0005 (accessed on 8 September 2023).

Box 1.6. Bridging the political-administrative interface in a coalition government in Spain

As has been the case in Spain in recent years, the formation of coalition governments requires greater co‑ordination and collaboration efforts to guarantee the coherence of government action and public policies.

This is the role of the CoG’s public policy department within the president’s office, which acts as the bridge and link between the presidency and the rest of the government ministries and agencies. The department supports the design and evaluation of the executive’s public policies. It must provide the president with accurate information on government action to inform decision-making. It must equally promote co‑ordination between ministries to drive coherence and alignment of government action.

The CoG is often remote from the day-to-day design and management of public policies, so a unit in charge of compiling all of the necessary information for the head of government as well as co‑ordinating and pursuing coherence in actions, ensures better achievement of objectives. In complex societies and contexts, information gathering and management can be a challenge for this function. As part of its work as a provider of consistency, the quality of the data and the data compilation and analysis capacity of the tool used for this purpose are key factors.

Source: Information provided by representatives of the General Secretariat of the Presidency of the Government.

Managing smooth election transitions

Building and maintaining institutional memory is a key task for CoGs. The CoG can be effective at managing transitions due to its systemic leverage, including agreements, committees, digital record keeping and information-sharing platforms. It can also appoint permanent staff to oversee these.

Staff turnover is critical to institutional memory. The experience and issues of trust for the CoG can also be shaped by the number of political staff in critical roles within the CoG. Brazil and the United States (see Boxes 1.7 and 1.8), for example, have a high level of staff turnover with changes of government. This requires the safe transfer of information and accountability for records storage and the continuation of long-term programmes. Parliamentary systems, with numerous possible outcomes at times of transition, also require significant transition planning (Box 1.9).

Box 1.7. Brazil – Facilitating the transition of government with a high turnover of staff

Brazil’s planning and managing of the transfer of power is crucial as transitions are characterised by a high degree of turnover. Over 50% of the senior staff has changed, including the head of the CoG. This creates challenges for building trust and, to ensure policy continuity, Brazil has introduced several tools to smooth the transition. These tools facilitate a more structured information flow. They include:

A transition portal: A website for officials in the Special Commission, directors and superior advisers, including special government transition positions, for the dissemination of information.

Agenda 100: A list of government commitments relating to legal requirements, international agreements, the parliamentary agenda and economic aspects. Developed by the outgoing government for the incoming, it outlines the long-term goals to support policy coherence. It informs the government about potential risks regarding unilateral breaches of agreements and contracts, fines, legal sanctions and diplomatic sensitivities.

A server’s guide: This guide is available to all members of the new government and provides information on the law that regulates the relationship between the administration and public servants, including the appointment of new civil servants, recruitment, remuneration and functions.

Source: OECD (2022[15]), Centre of Government Review of Brazil: Toward an Integrated and Structured Centre of Government, https://doi.org/10.1787/33d996b2-en.

Box 1.8. The United States: Supporting presidential transitions

Presidential transitions in the United States require significant co‑ordination and resources. While the transition of administration is supported by the General Services Administration (GSA), the CoG has a crucial role in the White House Transition Coordinating Council and the Agency Transition Directors Council (ATDC). Both are comprised of different CoG officials, including public servants and transition representatives for each eligible candidate. Priority is given to the appointment of staff to centralise co‑ordination and report all issues directly to the president.

Pre-election transition planning is used to prepare for a change in president and administration, which means that both the above-mentioned councils should be created six months prior to the presidential election. The ATDC meets at least once a year in non-presidential and regularly in presidential election years. With the help of the CoG, the outgoing administration negotiates the transition terms. By 1st November of the election year, all agreements made should be reflected in a memorandum of understanding (MOU).

If the CoG of the outgoing administration co-operates with the incoming, it can facilitate and ensure a smooth transfer of power. Additional mechanisms are in place to ensure co-operation, including a Federal Transition Coordinator appointed by the GSA and a requirement for each MOU to include an ethics plan that guides the conduct of the transition and applies to the president and transition teams of all eligible candidates throughout the transition period.

Sources: GSA (2022[16]), GSA’s Role in Presidential Transitions, https://www.gsa.gov/about-us/mission-and-background/gsas-role-in-presidential-transitions?topnav=about-us; Kumar, M. (2021[17]), Rules Governing Presidential Transitions: Laws, Executive Orders, and Funding Provisions, https://whitehousetransitionproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/WHTP2021-05-Rules-Governing-Presidential-Transitions.pdf; information from the OECD Expert Group on Strategic Decision Making at the Centre of Government – Special Session on Transition Management, United States Congress (2020[18]), Presidential Transition Enhancement Act of 2019, https://www.congress.gov/116/plaws/publ121/PLAW-116publ121.pdf.

Box 1.9. Canada: Managing transitions at the CoG in parliamentary systems

Transition governments in parliamentary systems can be complex due to the many possible outcomes. For example, a new majority/minority party could be elected, a party remain as a minority/minority but experience a party leadership change, or the same party could retain its majority/minority government.

In Canada, government transitions involve significant consultation and preparation in conjunction with line ministries well in advance of the actual transition of power. Careful planning begins up to six months prior to the election, where the prime minister of the current administration will normally authorise the clerk of the Privy Council (secretary to the cabinet) to begin transition planning. The leader of the opposition, i.e. the potential new prime minister, receives oral briefings on the preparation work. Meetings between the leader of the opposition and the clerk and the Privy Council Office (PCO) take place in lieu of specific contact between the opposition and current line ministers.

During the election, the PCO will monitor and survey election events. Normal decision-making capacities of the government are significantly reduced, with limited cabinet meetings. Following an election which results in a change of administration, the outgoing prime minister becomes head of a caretaker administration, limiting decision-making power as ministers prepare to leave office. The clerk and prime minister-designate meet regularly over the days before the formal transition, wherein the clerk briefs the prime minister-designate on key issues.

Source: OECD (1988[19]), “Management Challenges at the Centre of Government: Coalition Situations and Government Transitions”, https://doi.org/10.1787/5kml614vl4wh-en.

A recent OECD survey showed that there is typically some level of continuity within the CoG (OECD, 2023[20]). This creates an opportunity for the CoG to build permanent systems and organisational memory.

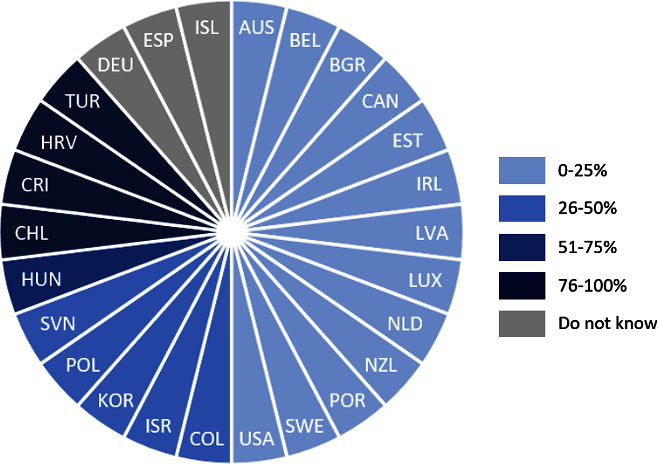

Figure 1.1. Change in the CoG senior management within six months following the transition

Note: n=26. Respondents to the OECD survey were asked “What proportion of the senior management of the CoG changed within the first six months following the last transition of government?”.

Source: OECD (2023[20]), “Survey on strategic decision making at the centre of government”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

6. Common challenges and enablers

Common challenges

The bridging role of the CoG is increasingly complex, with major global challenges and crises, alongside changing national agendas and geopolitical shifts. It can be more challenging with governments attempting to respond to declining trust and increasing polarisation.

CoGs need to ensure a productive, two-way relationship between the political and administrative interface. This relationship must allow for political directions to be implemented by the public administration. At the same time, it needs to allow for frank advice on the feasibility of policies from line ministries to be considered by the government.

Coalition governments may present unique challenges for the CoG. This context may require enhanced focus on communication and co‑ordination mechanisms to maintain good working relationships between all parties.

Periods of transition, as moments when institutional memory and staff expertise are frequently replaced (including within the CoG), may also require the focus of the CoG. Managing transitions – through agencies or building processes and guidelines – can be a challenge for CoG staff to pre-empt and address.

Key enablers

Ensuring clarity between the roles, accountabilities and interaction mechanisms between the political and administrative spheres is important. CoGs can facilitate this through manuals, agreements and ongoing discussions.

CoGs should not just focus on transactional elements of the interface but also on relational elements. Some CoGs find it effective to have regular, informal discussions between both sides of the interface, including with the line ministries.

Building the right skills within the workforce is a crucial enabler for the continued effective functioning of CoGs. This is important to effectively manage co‑ordination mechanisms, capacity building and generally leverage the expertise of the administration to execute priorities. CoG must ensure that the staff of the administration have the diverse skills necessary to perform at a high level. CoGs need to consider their overall mix of political versus non-political staff in this regard.

Clear mechanisms to translate the government agenda to the work of the public administration are also key enablers for the functioning of the government. A range of top-down and bottom‑up mechanisms to do this can be useful. The alignment between the priorities of the administration at all levels is essential for the effective implementation of the government priorities.

References

[7] Australian Government (2023), Australian Government Guide to Policy Impact Analysis, Office of Impact Analysis, https://oia.pmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-05/oia-impact-analysis-guide-march-2023_0.pdf.

[3] Brezzi, M. et al. (2021), “An updated OECD framework on drivers of trust in public institutions to meet current and future challenges”, OECD Working Papers on Public Governance, No. 48, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b6c5478c-en.

[2] Cairney, P. (2012), Understanding Public Policy: Theories and Issues, Bloomsbury Publishing.

[14] Christiansen, F. (2021), “Denmark: How to form and govern minority coalitions”, in Bergman, T., H. Back and J. Hellstrom (eds.), Coalition Governance in Western Europe, Comparative Politics, Oxford Academic, Oxford, https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198868484.003.0005 (accessed on 8 September 2023).

[13] Danish Parliament (n.d.), The Government, https://www.thedanishparliament.dk/en/democracy/the-government (accessed on 8 September 2023).

[6] Demir, T. (2022), “Politics and administration”, in Farazmand, A. (ed.), Global Encyclopaedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance, Springer, Cham.

[4] Favero, N. (2022), “Politics and bureaucracy”, in Farazmand, A. (ed.), Global Encyclopaedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance, Springer, Cham.

[12] Finnish Government (n.d.), About the Government, https://valtioneuvosto.fi/en/government (accessed on 7 September 2023).

[8] Giauque, D., F. Resenterra and M. Siggen (2009), “Trajectoires de modernisation et relations politico-administratives en Suisse”, Revue Internationale des Sciences Administratives, Vol. 75, pp. 757-781, https://www.cairn.info/revue-internationale-des-sciences-administratives-2009-4-page-757.htm (accessed on 8 September 2023).

[10] Grube, D. and C. Howard (2016), “Promiscuously partisan? Public service impartiality and responsiveness in Westminster systems”, Governance, Vol. 29/4, pp. 517-533, https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12224 (accessed on 7 September 2023).

[16] GSA (2022), GSA’s Role in Presidential Transitions, General Services Administration, United States, https://www.gsa.gov/about-us/mission-and-background/gsas-role-in-presidential-transitions?topnav=about-us (accessed on 7 September 2023).

[17] Kumar, M. (2021), Rules Governing Presidential Transitions: Laws, Executive Orders, and Funding Provisions, The White House Transition Project, https://whitehousetransitionproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/WHTP2021-05-Rules-Governing-Presidential-Transitions.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2023).

[9] OECD (2023), Public Employment and Management 2023: Towards a More Flexible Public Service, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5b378e11-en.

[20] OECD (2023), “Survey on strategic decision making at the centre of government”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

[15] OECD (2022), Centre of Government Review of Brazil: Toward an Integrated and Structured Centre of Government, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/33d996b2-en.

[1] OECD (2018), Centre Stage 2: The Organisation and Functions of the Centre of Government in OECD Countries, OECD, Paris, https://web-archive.oecd.org/2021-05-18/588642-report-centre-stage-2.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2023).

[19] OECD (1988), “Management Challenges at the Centre of Government: Coalition Situations and Government Transitions”, SIGMA Papers, No. 22, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5kml614vl4wh-en.

[11] Shostak, R. et al. (2023), The Center of Government, Revisited: A Decade of Global Reforms, Inter-American Development Bank, Washington, D. C., https://doi.org/10.18235/0004994.

[18] United States Congress (2020), Presidential Transition Enhancement Act of 2019, https://www.congress.gov/116/plaws/publ121/PLAW-116publ121.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2023).

[5] Vigoda-Gadot, E. and S. Mizrahi (2014), “Managing the democratic state: Caught between politics and administration”, in Vigoda-Gadot, E. and S. Mizrahi (eds.), Managing Democracies in Turbulent Times: Trust, Performance, and Governance in Modern States, Springer Berlin, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-54072-1 (accessed on 25 September 2023).