Driving sound decision-making practices has traditionally been a centre of government (CoG) responsibility through the facilitation of government and cabinet meetings. This chapter discusses the CoG’s role in undertaking this function, concentrating on how it steers decision-making in times of complexity. It focuses on the role the CoG plays in the decision-making fora of cabinet or government meetings, through agenda management and preparation. Further, this chapter acknowledges that CoGs are increasingly guiding sound decision-making more broadly across government, in regulation, risk, data and fostering public sector integrity. The latter half of this chapter focuses on these functions, detailing practical examples of how the CoG manages these increased functions to drive sound decision-making practices across government.

Steering from the Centre of Government in Times of Complexity

4. Driving sound decision-making practices from the centre

Abstract

Key messages

Centres of government (CoGs) have always traditionally played a role in guiding government decision-making through facilitating cabinet and government meetings. Yet, balancing the focus of the CoG on major policy issues facing governments can be tough.

More recently, CoGs are increasingly guiding good decision-making practices more broadly, including in regulation, risk and data.

The complexity of policy challenges, changing national agendas and competing priorities complicates CoGs’ role in coherently supporting good decision-making across the public service. They are required to do more mediating and negotiating between actors.

While CoGs add value to government decision-making practices, the risk is that they are perceived as blockers or braking mechanisms. Building an environment that fosters productive and trusted relationships between the CoG and line ministries is essential.

CoGs are crucial gatekeepers of the quality of the proposals put forward for debate during cabinet and government meetings and other decision-making fora. At times, balancing speed or agility with quality and integrity may be challenging.

Embedding a public administration culture of evidence-informed decisions is important. CoGs can support sound decision-making by putting in place incentives, guidance materials and standards that foster transparency and adequate engagement with stakeholders.

1. Introduction

CoGs play a role in guiding good public administration practices that allow sound decision-making. CoGs most traditionally ensure that decisions made in cabinet or government meetings are evidence-informed, well-prepared and aligned with government priorities. They can also foster good practices in decision-making across the administration in varied areas, including regulation or risk management.

Right now, with complex and cross-cutting challenges facing governments, sound decision-making requires consideration of unclear trade-offs and a multitude of actors (DeSeve, 2016[1]). CoGs must ensure coherence of decision-making practices throughout the public administration, balancing transparency and integrity with experimentation and risk. CoGs are well placed to harness leadership support for the use of evidence in decision-making (OECD, 2015[2]).

This chapter will explore the CoG’s role in driving sound decision-making within the following structure:

Supporting decision-making at cabinet and government meetings.

Stewarding good decision-making across other functions through regulation, risk management, data practices and fostering integrity in the public service.

2. Supporting decision-making at cabinet and government meetings

In most OECD member and accession countries, cabinet or government meetings are the highest-level forum for the discussion of policies, programmes and initiatives. As the supporting structure for the executive branch, CoGs are highly involved in these spaces (OECD, 2020[3]). They provide policy advice to help decision-makers debate policy options based on evidence and impacts (OECD, 2018[4]). According to the OECD survey (2023[5]), 73% of countries consider this a top priority. This section is an overview of CoG practices that foster quality decision-making in cabinet and government meetings, including agenda setting, managing preparation and conclusion of meetings.

Figure 4.1. The CoG guides in multiple decision-making areas

Source: Author’s own elaboration.

Setting the agenda

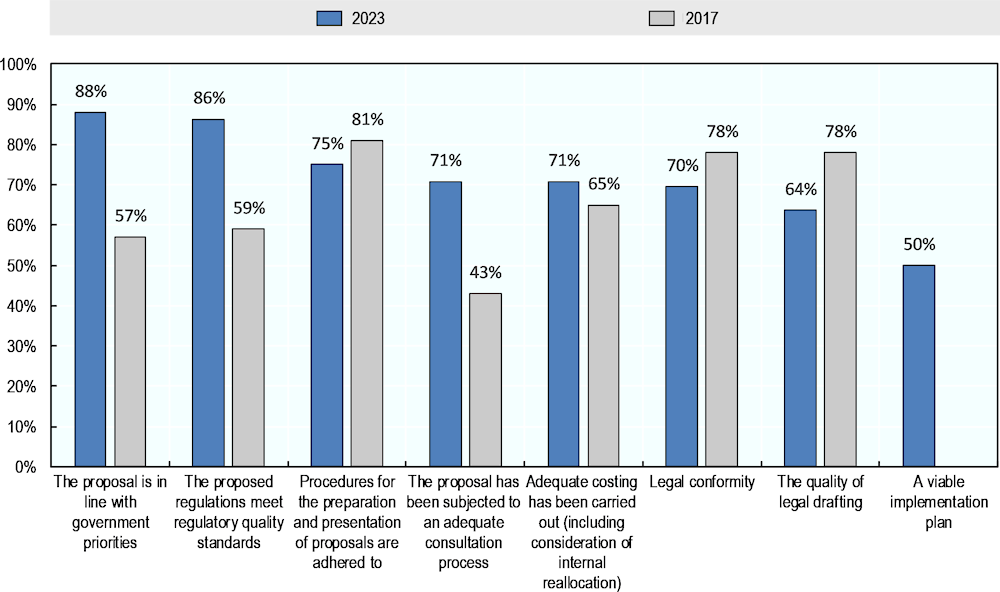

The CoG has an important role to play in deciding which items appear on the agenda of these decision-making meetings. It can drive sound decision-making by deciding what evidence and advice to present to decision-makers (OECD, 2018[4]). The CoG can directly manage the preparation of agenda items. In 2023, 73% of the surveyed CoGs indicated that one of their activities is to review draft policies proposals, legislation or other policy documents, ensuring that the proposed regulations meet standards; 65% of surveyed CoGs also review if the proposal has been subjected to an adequate consultation process. The CoG can also directly manage the agenda, including proposals from line ministries. In 38% of countries surveyed, CoGs help develop policy options.

Clear rules and procedures govern the development and submission of proposals. These are typically led by the CoG. For example, in Latvia, the Unified Portal for the Development and Agreement of Draft Legal Acts, developed and administered by the CoG, centralises the agenda and protocol for cabinet sittings. Other examples include countries such as Estonia, where the CoG leverages digital platforms for the submission of proposals (Box 4.1), while in Canada, it can set requirements for the development of the proposal itself (Box 4.2).

Box 4.1. Leveraging digital tools to support decision-making at the highest level

Case study: Estonia’s e-Cabinet

The information system for cabinet meetings in Estonia, known as e-Cabinet, is a tool that streamlines the decision-making process for cabinet meetings. This database and scheduler organises and updates relevant real-time information. Driven by the CoG, ministers and their teams are given a clear overview of every agenda item. Well before the start of the weekly cabinet session, ministers access the system to examine each item on the agenda and define their position on the topic. They can indicate if they have any objections or if they wish to speak on the subject. In this way, ministers’ positions are known in advance. Proposals to which there are no objections are adopted without debate, saving time. Meeting minutes are also published on the website. Since adopting a paperless e-cabinet system, the average length of weekly cabinet meetings has fallen from 4 to 5 hours to between 30 and 90 minutes.

Source: OECD (2023[6]), OECD Public Governance Reviews: Czech Republic: Towards a More Modern and Effective Public Administration, https://doi.org/10.1787/41fd9e5c-en (accessed on 23 May 2023).

Box 4.2. Case study: Memoranda to Cabinet as quality control in the government of Canada

Memoranda to Cabinet (MCs) are a tool for proposing policies and supporting rigorous, evidence-based decision-making within the Cabinet of Canada. MCs are brought forward by ministers to aid in cabinet deliberations when considering the introduction of new laws or initiatives, changes to existing legislation or programmes, or responses to parliament. There are several steps required to bring the proposal to the cabinet.

1. MC drafters must consult the CoG, which ensures the proposal is in line with government priorities, is appropriately costed and has been subjected to adequate and systematic analysis.

2. The department bringing forward the proposal must hold at least one meeting with the Privy Council Office.

3. Drafters organise consultations with other affected agencies and departments to address potential cross-cutting obstacles, collect additional information and address potential concerns.

4. The MC is discussed in the relevant cabinet policy committee, where decision-makers review the memoranda and prepare a recommendation for the cabinet.

Once a policy has been well discussed and a positive agreement has been reached, the MC is passed to the cabinet for ratification.

MCs follow a specific format. They describe the main issues at stake and list a set of actions, providing a clear rationale, a detailed approach and a consistency check of the proposal against key government objectives such as climate goals. They then set out how the policy would be addressed in parliament or through other measures.

The MCs’ development process has several internal control mechanisms to ensure the quality of the proposals that reach the cabinet for discussion. MCs are overseen by responsible minister(s). The Privy Council Office informs the chair of each cabinet committee about the progress of MCs. The chief financial officer of the sponsoring minister’s department reviews due diligence issues. Moreover, agencies in the CoG brief the prime minister, minister of finance and president of the Treasury Board on proposals.

Drafting MCs can take considerable time given the expected level of analysis and required consultations with the CoG and other agencies. A key to success is ensuring that planning and drafting take place well in advance so that the process is not rushed and that ministers can receive proposals well in advance of cabinet consideration so that they can internalise the information.

Note: The CoG in Canada is composed of the Privy Council Office, Finance Canada and the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS).

Source: Government of Canada (2020[7]), Machinery of Government, https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/transparency-transparence/mtb-ctm/2019/binder-cahier-1/1G-support-appuie-eng.htm (accessed on 9 June 2023); Information provided by the Privy Council Office.

Managing the preparation

CoGs support effectiveness at the decision-making stage by bringing together senior officials ahead of deliberations. They foster co‑ordination across policies and portfolios through mechanisms such as commissions, inter-ministerial working groups and ad hoc exchanges. In several OECD member and accession countries, CoGs facilitate these discussions, review supporting materials and act as an arbitrator in case of disputes between government entities (OECD, 2015[2]).

In some countries, informal sessions may be more common or even institutionalised. Box 4.3 showcases the examples of Finland and New Zealand, where CoGs have introduced preliminary meetings among line ministers and other policymakers to improve cabinet decision-making processes.

Box 4.3. Support to cabinet meetings

Support to cabinet meetings

In New Zealand, cabinet meetings are preceded by standing cabinet committees. Cabinet committees provide the opportunity for more detailed review and discussion of proposals and issues before they are submitted to the cabinet for decision. Officials’ committees provide support for most Cabinet committees and their chairs to progress the government’s policy agenda. The officials’ committees help to ensure policy cohesion, provide quality assurance during the drafting process, and ensure papers are progressed through the committee process in a timely manner.

Ministerial commissions in Finland

Finland has developed standing inter-ministerial committees to promote public policy coherence. They are involved in decision-making and the preparation of the government’s plenary session.

Other inter-ministerial working groups focus on the government’s priorities during its term of office. They drive work on the priorities forward by co-ordinating between ministries for collaboration. These working groups meet at least several times a year and are disbanded when there is a change of government, when new working groups based on the new government’s priorities are put in place. This approach helps streamline and prevent duplication of work.

In both Finland and New Zealand, these fora provide opportunities for exchange and feedback ahead of the decision-making phase. This can increase efficiency during cabinet meetings and ensures that proposals that reach this stage align with government priorities and are supported by the cabinet.

Source: New Zealand Government (2023[8]), Cabinet Manual, https://www.dpmc.govt.nz/our-business-units/cabinet-office/supporting-work-cabinet/cabinet-manual (accessed on 26 May 2023); Government of Finland (2021[9]), Ministerial Committees and Working Groups, https://valtioneuvosto.fi/en/government/ministerial-committees (accessed on 7 June 2023).

Communicating the outcomes

While the discussions during cabinet or government meetings tend to be confidential, several countries prepare minutes or proceedings of the decisions made during the session. The agreements and commitments reached during the meeting are made public. This provides an element of accountability, as it sheds light on the implementation of priorities by the government.

3. Guiding sound decision-making across broader functions

More recently, CoGs have been called upon to guide broader decision-making practices across public administration. This includes practices in regulation, risk, data and fostering public sector integrity.

Guiding high-quality regulatory practices

Ensuring regulatory quality is an important objective in support of the government’s decision-making function. In line with the OECD Recommendation on Regulatory Policy and Governance, a “whole-of-government” approach to regulatory policy can support administrations in attaining public objectives (OECD, 2012[10]). CoGs can play a role in both the governance arrangements of rulemaking and regulatory management tools that administrations can use to ensure that regulations are effective and conducive to public objectives.

The CoG can support regulatory governance with gatekeeping functions, the provision of guidance, promoting the whole-of-government regulatory policy, using tools such as regulatory impact assessments and ex post evaluations, and evaluating regulatory policy. Positioning these functions close to the CoG can benefit the adoption of the policy throughout the administration (OECD, 2012[10]). Box 4.4 presents the example of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA), the regulatory oversight body in the United States, which is located in the Office of Management and Budget.

Figure 4.2. Quality insurance of draft policy proposals and legislations at the CoG

Note: n=26. Respondents to the OECD survey were asked: “When reviewing draft policy proposals, legislation or other policy documents, which aspects does the CoG ensure?”.

Source: OECD (2023[5]), “Survey on strategic decision making at the centre of government”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

Box 4.4. Regulatory oversight bodies close to the CoG

The Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, United States

The Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) is a statutory part of the Office of Management and Budget within the Executive Office of the President. OIRA is the United States government’s central authority for regulatory oversight of executive branch regulations and regulatory policy. Because OIRA is positioned in the CoG, it can co‑ordinate actions across the entire federal administration.

In addition to reviewing drafts of proposed and final regulations, OIRA scrutinises ex post evaluations of regulations and reviews. It approves government collections of information from the public and oversees the implementation of government-wide policies in the areas of information policy, privacy and statistical policy. OIRA also co-ordinates international regulatory co-operation.

Having a regulatory oversight body allows for a horizontal view of the policymaking environment and facilitates access to information from different parts of the government.

Source: The White House (2023[11]), Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/information-regulatory-affairs/ (accessed on 6 April 2020); Renda, A., R. Castro and G. Hernández (2022[12]), “Defining and contextualising regulatory oversight and co-ordination”, https://doi.org/10.1787/a4225b62-en.

CoGs can play a decisive role in promoting innovative approaches to regulatory policy and contributing to the necessary changes in institutional culture and mindsets across the administration (OECD, 2021[13]). Flexible and adaptable regulatory approaches led by the centre can support innovative decision-making and manage risks. Box 4.5 presents the case of Canada’s Centre for Regulatory Innovation, a CoG initiative to help regulation keep pace with new developments.

Box 4.5. Canada’s Centre for Regulatory Innovation

Canada’s Centre for Regulatory Innovation, established in 2018, is part of the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat and works across the government to support regulators to increase their toolbox regarding innovative approaches and practices, develop the capacities to carry out regulatory experimentation, and engage and exchange with other practitioners.

To that effect, the CoG provides regulators with resources, advice and expertise in the development of regulatory experiments and sandboxes, among others. The centre has also made available a set of capacity-building and training resources: The Regulators’ Experimentation Toolkit and GCWiki page offer information on applying for regulatory innovation funding and describe the projects the centre has supported to date.

The CoG provides a bridge between regulators and businesses with the objective of encouraging innovation while limiting potential risks and protecting consumer trust. The CoG mandate derives from a high-level commitment from the Canadian administration to improve the regulatory environment for businesses, allowing regulators to adopt a future-looking perspective to rulemaking. Future actions to harness the power of innovation through better regulation include the development of capacities across regulators to make the most of agile regulatory practices.

Sources: OECD (2021[13]), OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2021, https://doi.org/10.1787/38b0fdb1-en; Government of Canada (2022[14]), Centre for Regulatory Innovation, https://www.canada.ca/en/government/system/laws/developing-improving-federal-regulations/modernizing-regulations/who-we-are.html (accessed on 26 May 2023); Government of Canada (2022[15]), Regulators’ Capacity Fund: Lessons Learned Report, https://wiki.gccollab.ca/images/1/12/RCF_Lessons_Learned_Report_2022_-_English_(Final).pdf (accessed on 26 May 2023).

CoGs can also promote regulatory quality through the development of guidelines and requirements for quality and future-proofed regulation. Box 4.6 highlights the case of Australia’s Office of Impact Analysis, a body in the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet that provides capacity building to line ministries and agencies in the development of regulatory impact assessments.

Box 4.6. Building capacities for better regulation across the administration

Australia’s Office of Impact Analysis

The introduction of better regulation requirements benefits from the development of guidelines and capacity-building activities that provide line ministries, regulatory agencies and other entities with the tools to successfully implement these obligations.

Australia’s Office of Impact Analysis (OIA, formerly OBPR) offers capacity building on the impact analysis of regulatory proposals put forward by ministries or other entities. The office provides different kinds of training and resources free of charge to public officials. The contents, scope and purpose of the coaching activities are based on the audience and their needs. The OIA has five streams of capacity:

General policymaker training or “RIA 101”.

Ministry-specific training.

First-year cohort training.

Ad hoc “needs-based” training.

International and interstate training.

The OIA’s central location gives it an overarching view. It devotes an important part of its resources to engaging with regulators and bridging the knowledge gap in the use of RIA for policymaking. Certainly, embedding the use of regulatory management tools in the day-to-day activities of decision-makers goes beyond just the introduction of obligations and requires a proactive effort from the centre to facilitate their use. In the case of Australia, this has helped develop a high-performing regulatory system.

Source: Australian Government (2023[16]), Guide to Policy Impact Analysis, https://oia.pmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-05/oia-impact-analysis-guide-march-2023_0.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2023).

Guiding risk management

The CoG has traditionally taken on a significant role in risk management by supporting decision-makers and co‑ordinating government action. Out of the OECD CoGs surveyed in 2023, 12% identified risk management and risk anticipation as their top or significant priority for driving sound decision-making. The OECD Recommendation of the Council on the Governance of Critical Risks recommends that members build preparedness through foresight analysis and risk assessment frameworks to better anticipate complex and wide-ranging impacts (OECD, 2014[17]).

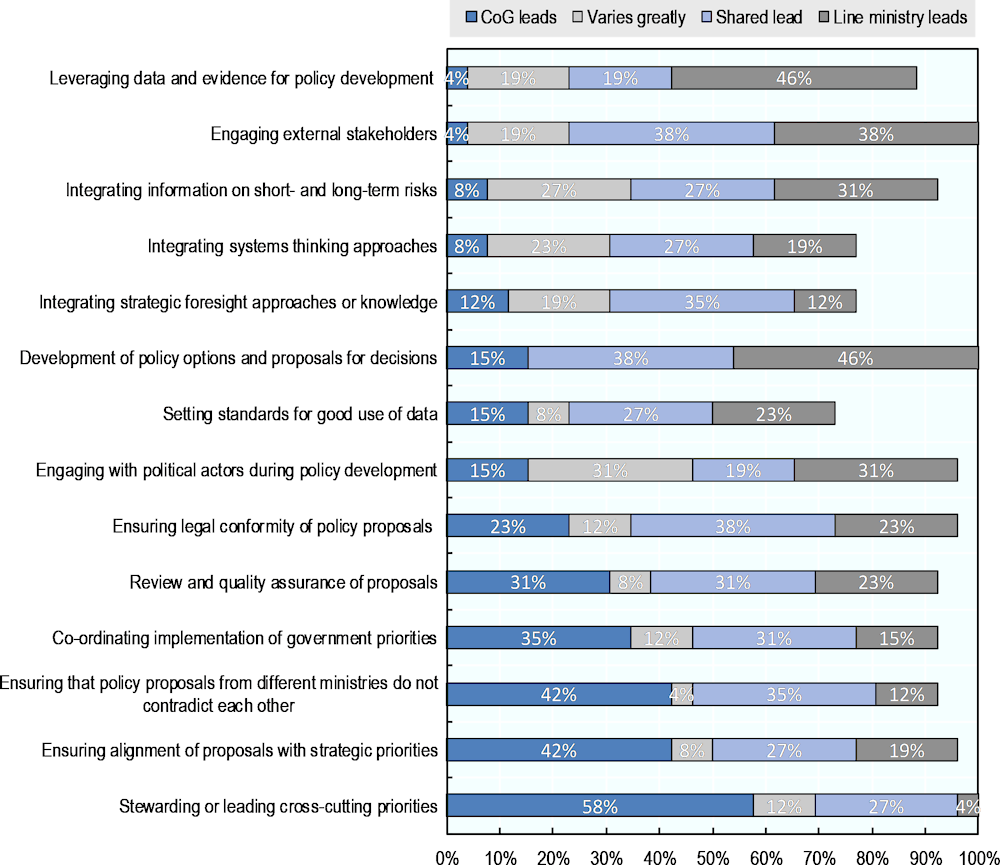

Eight percent of the surveyed CoGs responded having a lead responsibility for integrating information on short- and long-term risks in policy development and, further, 27% share this responsibility with line departments. The CoG typically shares evidence from departments and scientific bodies with senior government officials (OECD, 2018[4]). Linking policy advice with the best available scientific advice – namely, high-quality, and timely advice – can add significant value during a crisis (OECD, 2018[18]). This supports better decision-making through the risk management cycle and can help design more effective policy interventions. Identifying potential impacts can be challenging, particularly during fast-paced or uncertain periods. This means that administrators may find it challenging to move from a “reactive” to a “proactive” approach as they might not have all of the relevant resources to make evidence-based decisions.

Box 4.7. Risk management from the centre

Ireland’s National Risk Assessment

The Department of the Taoiseach (the prime minister of the Republic of Ireland) prepares and publishes an annual National Risk Assessment where it identifies and discusses the significant risks facing the country. First published in 2014, the National Risk Assessment provides a systematic approach to identifying and debating strategic risks facing Ireland over the short, medium and long terms. The National Risk Assessment underpins all of the specific risk management activities that different departments and agencies carry out. Its development is informed by stakeholder engagement activities that are aimed at collecting the views of citizens, organisations and public representatives on the draft list of risks identified by the Taoiseach.

The results of the National Risk Assessment can be a useful source of information to consider during the decision-making process and provide the basis for developing policies that will help build resilience. The CoG’s engagement in the development and presentation of the National Risk Assessment signals the cross-cutting nature and importance of this document as a guide for informing public action.

Source: Government of Finland (2021[19]), National Risk Assessment 2021/2022: Overview of Strategic Risks, https://www.gov.ie/en/policy-information/795550-national-risk-assessment/#national-risk-assessment-20212022-overview-of-strategic-risks (accessed on 26 May 2023); OECD (2017[20]), National Risk Assessments: A Cross Country Perspective, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264287532-en (accessed on 25 May 2023).

Guiding good data practices

CoG stewardship can improve the capacity for an evidence-informed approach to decision-making. Ensuring the use of accurate and reliable information can be a challenge in fast-paced or high-volume contexts. CoGs can support this by creating mechanisms, practices and guidance that help accelerate and standardise data management and use.

Box 4.8 highlights the CoG’s role in leading and co‑ordinating decisions on digital government in Portugal and the United Kingdom.

Box 4.8. Digital government leadership from the CoG

Case study: The Central Digital and Data Office and Government Digital Service, United Kingdom

The Central Digital and Data Office (CDDO) and the Government Digital Service (GDS) of the United Kingdom lead the digital government agenda at the centre of government and are part of the Cabinet Office. The CDDO leads the government’s Digital, Data and Technology (DDaT) Function and sets the strategic direction for the government on digital, data and technology. It also administers standards such as the Government Service Standard, the Technology Code of Practice and the Cabinet Office digital and technology spend controls. The GDS works across the whole government to assist departments in transforming its public services. It has built and maintained several cross-government-as-a-platform tools such as GOV.UK, GOV.UK Verify, GOV.UK Pay, GOV.UK Notify and the Digital Marketplace.

Case study: The Administrative Modernisation Agency, Portugal

Portugal’s digital transformation agency, the Administrative Modernization Agency, was created in 2007 and sits within the Presidency of the Council of Ministers. It exercises the powers of the Ministry of State Modernization and Public Administration in modernisation, administrative simplification and digital government and is under the supervision of the Secretary of State for Innovation and Administrative Modernization. The agency has a top role in the development, promotion and support of the public administration in several technological fields and is in continuous contact with focal points at institutions relevant to the implementation of digital government projects. It is responsible for the approval of information and communication technology (ICT) and digital projects over EUR 10 000 and chairs the Council for ICT in public administration.

Source: OECD (2021[21]), The E-Leaders Handbook on the Governance of Digital Government, https://doi.org/10.1787/ac7f2531-en (accessed on 6 September 2023); UK Government (2023[22]), Central Digital and Data Office, https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/central-digital-and-data-office (accessed on 6 September 2023).

CoGs can leverage the technological developments of digital transformation to boost the availability and use of high-quality data in decision-making. This frequently involves centre‑led new governance arrangements, policy and legislative change, infrastructure construction and capability development.

While line ministries most frequently lead on leveraging data and evidence for policy development, many CoGs have overseen the establishment of national data strategies to ensure the creation of systems that maximise and protect data’s public value and facilitate the use of evidence by policymakers (OECD, 2017[23]). Box 4.9 highlights the examples of Australia and Germany’s use of the CoG in national data strategies to enhance capacity.

Figure 4.3. Setting standards for good use of data tends to be a shared responsibility

Note: n=26. Respondents to the OECD survey were asked: “For each of the below activities regarding co‑ordinating and enhancing policy development, please indicate who has the primary responsibility”.

Source: OECD (2023[5]), “Survey on strategic decision making at the centre of government”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

Box 4.9. Enhancing data capability in Australia and Germany

Case study: Australia’s development of data capability

Australia’s big data transition has been a multi-agency collaborative endeavour primarily co‑ordinated by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, with the role more recently transitioned to the Department of Finance. Data sharing and collaboration were supplemented by the establishment of enabling policy, legislative arrangements and infrastructure.

The 2015 Public Sector Data Management Project provided the initial call to action and signalled the policy shift to increased data sharing and use. The project focused on building cross-agency and sector partnerships, building confidence through high-value projects and quick wins, and systematising data sharing and use through policy frameworks and legislative change.

This networked approach has enabled responsibility for whole-of-government functions to be shared. This both disperses the effort and ensures that components are led by those agencies with the necessary knowledge, skills and authority. Additionally, when the COVID-19 pandemic emerged in early 2020, the five-year investment in data collaboration could be pivoted to address this highly data-dependent crisis. The Australian government’s data and analytics community knew and trusted each other’s capacities and expertise. As responsibilities were dispersed throughout the network, so was the load during this critical time. While shared infrastructure, capability and trusted networks can be slow to build, they have broad applications and, once in place, are essential for an agile government.

Case study: Data labs, chief data officers or chief data scientists in federal ministries and the Federal Chancellery in Germany

All German federal ministries and the Federal Chancellery have established a data lab and created the position of a chief data officer or scientist. The mission of the labs, which work together horizontally, is to foster the use of data, establish a data culture, raise the level of data literacy and contribute to data-driven policy and decision-making.

Their work includes:

Performing data analysis.

Providing and elaborating infrastructure for the supply and exchange of data.

Identifying and implementing relevant use cases for automation or use of data.

Establishing a data governance in the ministries and government-wide.

Some labs were integrated into existing units, while others created new units or interdepartmental groups. Each is made up of a team from diverse backgrounds, ranging from data scientists and engineers to political scientists and physicists. The establishment of these labs is a key measure of Germany’s first Data Strategy (2021), the German Recovery and Resilience Plan (2021) and Germany’s Digital Strategy (2022).

Sources: Australian Government (2016[24]), Public Sector Data Management, https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2016-07/apo-nid236601.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2023); Information provided by the German Chancellery.

As governments mainstream the use of digital technologies and data across government, they must consider robust data governance frameworks that support data access and sharing across the public sector and when needed with external actors. This includes legal and administrative structures, institutional arrangements and mechanisms, policy instruments, co‑ordination and advisory fora and technical aspects including shared data infrastructures and data standardisation and interoperability. It often requires clear and solid leadership, together with the involvement and accountability of relevant stakeholders of the ecosystem. A successful digital transformation requires close co‑ordination between the digital government strategy design and execution, efficient and agile management, consistent and coherent planning, and investment in digitalisation projects and initiatives in the public sector (OECD, 2021[21]).

With the increased role of the CoG in cross-cutting complex issues that require evidence-informed decision-making, supporting the exchange of timely, high-quality data across the public administration is essential. The CoG can serve to co‑ordinate the use of data across line ministries and other stakeholders, as it does in the example of Finland.

Box 4.10. Leveraging research data from the centre in support of decision-making in Finland

The TEA Working Group is a unit within the Finnish CoG whose main goal is to promote co‑operation and information exchange between the ministries. Appointed and annually assessed by the Prime Minister’s Office, it brings together representatives from all ministries, thus ensuring comprehensive horizontal oversight of ministerial research, foresight and assessment activities. To eliminate overlap, ensure continuity and strengthen evidence-informed decision-making, it guides the analysis, assessment and research process of governing institutions. It has also been a key actor in deciding the research topics to be included in the annual government research plan.

The TEA Working Group’s horizontal approach fosters a more comprehensive view of the needs and challenges that the Finnish society might face in the future. The findings from the different research activities have been directly linked to the government plan for analysis, assessment and research, which has provided a source of data for decision-making by ministries and the government.

Sources: Government of Finland (n.d.[25]), Government Working Group for the Coordination of Research, Foresight and Assessment activities, https://tietokayttoon.fi/en/government-working-group-for-the-coordination-of-research-foresight-and-assessment-activities; Pellini, A. (n.d.[26]), “Making research evidence count: Insights from Finland’s Policy Analysis Unit”, https://odi.org/en/insights/making-research-evidence-count-insights-from-finlands-policy-analysis-unit/.

Fostering public sector integrity, openness and public participation

Public integrity is one of the determinants of trust in the government (OECD, 2022[27]). CoGs have an important responsibility when it comes to fostering public integrity. They are well placed to co‑ordinate and/or contribute to the development and mainstreaming of integrity frameworks for decision-making. CoGs can also help set clear standards, proportionate sanctions and effective procedures to help prevent violations of public integrity and identify and manage actual, perceived and/or potential conflicts of interest (OECD, 2017[28]). CoGs can also encourage public integrity within the public administration by building knowledge, skills and commitment to public integrity amongst public officials. Providing sufficient information and training, including guidelines and consultation mechanisms, is key to fostering a culture of integrity in the administration (OECD, 2020[29]).

CoGs can improve access to information, promote open government and ensure effective oversight mechanisms across the administration (OECD, 2022[30]). CoGs, therefore, have an important role in promoting public participation in decision-making. For example, in Latvia, the CoG plays an important role in raising awareness about the importance of public participation to ensure meaningful and proactive citizen involvement in policy. The CoG systematically reviews draft legal acts for citizen inclusion, aligning with the 2024 Guidelines for Ensuring Public Participation in Public Administration, and will offer an e‑course on this in 2024.

Box 4.11. Assigning responsibility for public integrity to a central government body

Countries may place core responsibilities for integrity with a central government body, whereas others will make this the responsibility of an independent or autonomous body. Regardless of structure, counties should ensure that the institutional actors have the appropriate level of authority.

United Kingdom

The Joint Anti-Corruption Unit is in the Cabinet Office and is responsible for overseeing the implementation of the UK Anti-Corruption Strategy and supporting the Prime Minister’s Anti-Corruption Champion. The UK 2017-22 Anti-Corruption Strategy was developed through extensive cross-government discussion led by the Joint Anti-Corruption Unit.

Peru

The Secretariat of Public Integrity (Secretaria de Integridad Pública) is in the Presidency of the Council of Ministers and is responsible for governing integrity policies in Peru. Created in April 2018 by Supreme Decree 042-2018-PCM, it is the technical body in charge of conducting and supervising compliance with the National Policy of Integrity and Fight against Corruption at both the national and subnational levels, as well as of developing mechanisms and instruments to prevent and manage the risks of corruption. It is also responsible for proposing, co-ordinating, conducting, directing, supervising and evaluating policies, plans and strategies concerning integrity and public ethics. As governing entity for integrity, the Secretariat of Public Integrity provides advice, guidance and rules.

Australia

Promoting integrity is a key part of Australia’s public sector reforms run by the CoG. It underpins the trust of the Australian public, who rely on the CoG to serve their interests and deliver the best outcomes for Australia. The Secretaries Board (comprised of all heads of agencies) is committed to promoting a pro‑integrity culture where all staff feel confident to contribute ideas, provide frank and independent advice and report mistakes. In this spirit, the Secretaries Board set up the APS Integrity Taskforce. Australia has embedded integrity principles into the senior executive performance and leadership frameworks. Additionally, Australia is establishing an independent National Anti-Corruption Commission.

Sources: OECD (2021[31]), Integrity in the Peruvian Regions: Implementing the Integrity System, https://doi.org/10.1787/ceba1186-en; OECD (2020[29]), OECD Public Integrity Handbook, https://doi.org/10.1787/ac8ed8e8-en; Australian Government (2023[32]), “The Fraud Rule is changing”, https://www.counterfraud.gov.au/news/general-news/fraud-rule-changing (accessed on 1 December 2023).

Decision-making with integrity is done through a skilled and professional workforce, including in their use of public service values and standards of integrity in day-to-day actions. Box 4.12 presents the case of the Australian Public Service Commission, an agency in Australia’s CoG that plays a crucial role in stewarding the performance of the public service workforce and promoting integrity.

Box 4.12. Fostering the right skills for decision-making across the administration

The Australian Public Service Commission

The Australian Public Service Commission (APSC) is an agency under the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet responsible for strengthening the capabilities of the Australian Public Service workforce. Given the need for more agile working methods and the fast-paced context in which governments are operating, the APSC is working on future-proofing the Australian public service through the commission’s strategic planning via four priorities: support quality public service workforce management, build leadership for the future, lift public service capability and foster trust and integrity.

Within the APSC, the Integrity Agencies Group (IAG) works to ensure integrity is at the centre of public sector work. The IAG meets twice a year and leads co-ordination and promotion of integrity by identifying existing gaps, sharing information, engaging with major reform initiatives by providing guidance on modern integrity practices and promoting integrity frameworks such as complaint resolution and auditing. The APSC’s location in the CoG places it in a position to disseminate good practices and foster the development of a high-quality workforce throughout the Australian administration.

Sources: Australian Government (2023[33]), Australian Public Service Commission, https://www.apsc.gov.au/ (accessed on 6 June 2023); APSC (2019[34]), The Australian Public Service Commission: Capability Review and Strategy for the Future, https://www.apsc.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-03/australian_public_service_commission_-_capability_review_and_future_strategy.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2023).

4. Common challenges and enablers

Through a synthesis of information collected through country practices, desk research, interviews and the experiences shared by participants of the OECD informal Expert Group on Strategic Decision Making at the Centre of Government, the following key considerations can be identified.

Common challenges

The CoG’s role in driving good decision-making in cabinet and government meetings may be more challenging in times of a coalition government and polarisation. This may require the CoG to adapt approaches by focusing more on central co‑ordination, building relations and mediation.

The CoG must also balance its role as gatekeeper and process manager of agenda setting and screening cabinet items, ensuring the necessary flexibility to promote agile decision-making. The CoG must maintain good relationships and a sound understanding of line ministry issues and contexts to be able to, if necessary, adapt timelines or agendas to respond to a rapidly evolving environment.

Collecting data in simple formats under short timelines while ensuring reliability and quality can be challenging. At the current juncture, with increasingly complex and pressing horizontal issues, the CoG must develop clear and constant communication channels with knowledge producers and diverse stakeholders.

CoGs may find it initially challenging to embed good practices on regulation or risk-based approaches in the daily work of decision-makers. In the CoG’s close position to the highest political level, it can leverage political leadership from the highest level to generate support.

CoG experiences note that a careful balance is required when dealing with the major policy facing government, such as trust, polarisation and democracy.

Key enablers

The CoG can play an important role in embedding a culture of evidence-informed decision-making. Systematically ensuring that proposals are informed by evidence can be a key enabler for better public outcomes. CoGs need to have a good grasp of the overall ambitions of the government and the external operating environment to guide good decision-making practices.

The CoG’s role in promoting and co‑ordinating the use of better practices regarding regulation, risk or public integrity can be strengthened by the availability of guidance and capacity-building materials to facilitate the adoption of these practices.

Clearly defined procedures, roles, responsibilities and instruments are useful elements to build consensus on the requirements and preparations of cabinet meetings.

Formal and informal spaces to exchange and discuss potential policies can build consensus in the cabinet and help ensure that proposals take into consideration their potential impacts.

Identifying key information flows and sources can facilitate the use of evidence in decision-making. Strengthening the data governance ecosystem, including the role of the CoG as a knowledge broker, can increase the availability of timely and high-quality data.

As CoGs play a greater role in guiding good decision-making practices, levers such as setting standards and guidelines, training, new structures or mandates and shifting culture are key.

CoGs need to have the right skills to support the greater collaboration, negotiation and potential arbitration that current government contexts demand.

References

[34] APSC (2019), The Australian Public Service Commission: Capability Review and Strategy for the Future, Australian Public Service Commission, https://www.apsc.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-03/australian_public_service_commission_-_capability_review_and_future_strategy.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2023).

[33] Australian Government (2023), Australian Public Service Commission, https://www.apsc.gov.au/ (accessed on 6 June 2023).

[16] Australian Government (2023), Guide to Policy Impact Analysis, Office of Impact Analysis, https://oia.pmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-05/oia-impact-analysis-guide-march-2023_0.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2023).

[32] Australian Government (2023), “The Fraud Rule is changing”, Commonwealth Fraud Prevention Centre, https://www.counterfraud.gov.au/news/general-news/fraud-rule-changing (accessed on 1 December 2023).

[24] Australian Government (2016), Public Sector Data Management, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2016-07/apo-nid236601.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2023).

[1] DeSeve, E. (2016), Enhancing the Government’s Decision-Making: Helping Leaders Make Smart and Timely Decisions, Partnership for Public Service and IBM Center for the Business of Government, https://www.businessofgovernment.org/sites/default/files/Enhancing%20the%20Government%27s%20Decision-Making.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2023).

[14] Government of Canada (2022), Centre for Regulatory Innovation, https://www.canada.ca/en/government/system/laws/developing-improving-federal-regulations/modernizing-regulations/who-we-are.html (accessed on 26 May 2023).

[15] Government of Canada (2022), Regulators’ Capacity Fund: Lessons Learned Report, https://wiki.gccollab.ca/images/1/12/RCF_Lessons_Learned_Report_2022_-_English_(Final).pdf (accessed on 26 May 2023).

[7] Government of Canada (2020), Machinery of Government, https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/transparency-transparence/mtb-ctm/2019/binder-cahier-1/1G-support-appuie-eng.htm (accessed on 9 June 2023).

[9] Government of Finland (2021), Ministerial Committees and Working Groups, https://valtioneuvosto.fi/en/government/ministerial-committees (accessed on 7 June 2023).

[25] Government of Finland (n.d.), Government Working Group for the Coordination of Research, Foresight and Assessment activities, Prime Minister’s Office, https://tietokayttoon.fi/en/government-working-group-for-the-coordination-of-research-foresight-and-assessment-activities.

[19] Government of Ireland (2021), National Risk Assessment 2021/2022: Overview of Strategic Risks, https://www.gov.ie/en/policy-information/795550-national-risk-assessment/#national-risk-assessment-20212022-overview-of-strategic-risks (accessed on 26 May 2023).

[8] New Zealand Government (2023), Cabinet Manual, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, https://www.dpmc.govt.nz/our-business-units/cabinet-office/supporting-work-cabinet/cabinet-manual (accessed on 26 May 2023).

[6] OECD (2023), OECD Public Governance Reviews: Czech Republic: Towards a More Modern and Effective Public Administration, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/41fd9e5c-en (accessed on 23 May 2023).

[5] OECD (2023), “Survey on strategic decision making at the centre of government”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

[27] OECD (2022), Building Trust and Reinforcing Democracy: Preparing the Ground for Government Action, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/76972a4a-en.

[30] OECD (2022), Recommendation of the Council on Principles for Transparency and Integrity in Lobbying, OECD, Paris, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0379 (accessed on 25 May 2023).

[31] OECD (2021), Integrity in the Peruvian Regions: Implementing the Integrity System, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ceba1186-en.

[13] OECD (2021), OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2021, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/38b0fdb1-en.

[21] OECD (2021), The E-Leaders Handbook on the Governance of Digital Government, OECD Digital Government Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ac7f2531-en (accessed on 6 September 2023).

[29] OECD (2020), OECD Public Integrity Handbook, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ac8ed8e8-en.

[3] OECD (2020), Policy Framework on Sound Public Governance: Baseline Features of Governments that Work Well, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c03e01b3-en.

[4] OECD (2018), Centre Stage 2: The Organisation and Functions of the Centre of Government in OECD Countries, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/gov/report-centre-stage-2.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2023).

[18] OECD (2018), Scientific Advice During Crises: Facilitating Transnational Co-operation and Exchange of Information, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264304413-en.

[23] OECD (2017), Meeting of the OECD Council at Ministerial Level Going Digital: Making the Transformation Work For Growth and Well-Being, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/mcm/documents/C-MIN-2017-4%20EN.pdf (accessed on 23 August 2018).

[20] OECD (2017), National Risk Assessments: A Cross Country Perspective, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264287532-en (accessed on 25 May 2023).

[28] OECD (2017), OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Integrity, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/gov/ethics/OECD-Recommendation-Public-Integrity.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2021).

[2] OECD (2015), Centre Stage: Driving Better Policies from the Centre of Government, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/gov/Centre-Stage-Report.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2023).

[17] OECD (2014), Recommendation of the Council on the Governance of Critical Risks, OECD, Paris, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0405 (accessed on 4 September 2023).

[10] OECD (2012), Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264209022-en.

[26] Pellini, A. (n.d.), “Making research evidence count: Insights from Finland’s Policy Analysis Unit”, Overseas Development Institute, https://odi.org/en/insights/making-research-evidence-count-insights-from-finlands-policy-analysis-unit/.

[12] Renda, A., R. Castro and G. Hernández (2022), “Defining and contextualising regulatory oversight and co-ordination”, OECD Regulatory Policy Working Papers, No. 17, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/a4225b62-en.

[11] The White House (2023), Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, Office of Management and Budget, https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/information-regulatory-affairs/ (accessed on 6 April 2020).

[22] UK Government (2023), Central Digital and Data Office, https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/central-digital-and-data-office (accessed on 6 September 2023).