This chapter discusses the role of the centre of government (CoG) in stewarding long-term government visions and translating these into clear priorities through a strategic planning process. Balancing long-term development outcomes with immediate priorities or crisis responses is becoming increasingly important. Through fostering alignment and cohesion across ministries and different levels of government, the CoG helps avoid duplication or conflict in government action. This chapter presents specific practical examples of mechanisms the CoG can use to build good strategic planning practices, including frameworks and standards, guidance, quality reviews and capacity building for ministries. It further discusses these within the context of developing a long-term vision in an increasingly polarised environment.

Steering from the Centre of Government in Times of Complexity

2. Setting the vision, strategic planning and prioritisation

Abstract

Key messages

Setting clear vision, priorities and plans is key to stewarding outcomes across the government.

Centres of government (CoGs) steward these functions, yet are finding this more challenging, particularly in balancing long-term development outcomes with the immediate priorities or crisis responses.

CoGs also need to foster alignment and cohesion across ministries and different levels of government to avoid duplication or conflicting government action. This requires CoGs to build trusted relationships with line ministries and navigate between conflicting agendas at times.

CoGs utilise a range of mechanisms to build good strategic planning practices across the public administration, including setting frameworks and standards, providing guidance, quality review of plans and, indirectly, support or capacity building for line ministries.

In this role, key considerations include balancing national and international commitments, engaging with internal and external stakeholders in planning processes, negotiating different agendas, enhancing strategic thinking capability and linking planning with implementation.

1. Introduction

CoGs are crucial in stewarding a country’s vision, long-term strategy and priorities. From their unique central positioning, they set the overall vision and co‑ordinate strategic planning and prioritisation across the public administration. The data collected through the OECD (2023) “Survey on strategic decision-making at the centre of government” (hereafter the Survey) demonstrate that this is a core role of CoGs. In 2023, 73% of OECD member and accession countries reported that formulating a long-term vision is a top or significant priority for their CoG and 58% of surveyed parties described setting priorities as an important function.

Translating vision and priorities into co‑ordinated action benefits from a co‑ordinated approach across the government and planning of the necessary resources to deliver on the priorities. CoGs are, thus, often performing these functions: 73% of CoGs reported that ensuring alignment across documents and with the budget is a significant or top priority (OECD, 2023[1]).

Strategic planning and prioritisation are activities that tend to involve actors from several areas of the administration as well as external stakeholders. CoGs, therefore, need to ensure consistent quality across the administration and build the overall planning capacity of officials: 88% of CoGs mentioned that setting frameworks, standards, guidance and building capacity for strategic planning is a priority.

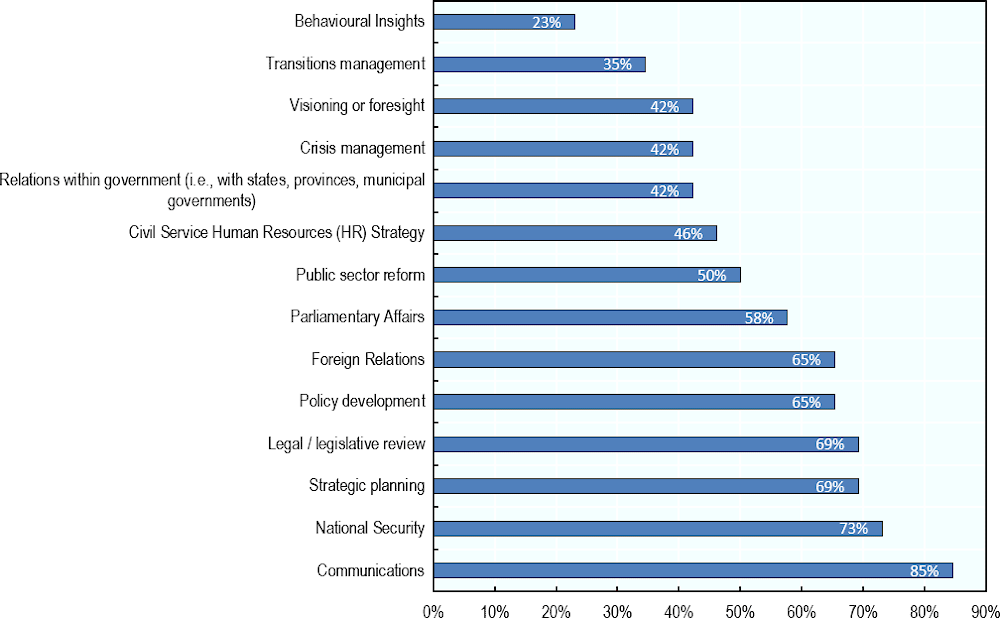

The institutional structures of CoGs vary across countries and according to their functions and priorities. “With easy access to senior government leaders, but relatively small budgets and staff, CoGs embody the ‘engine room’ of decision-making and are well situated to bring together both people and issues to set the direction of travel” (OECD, 2018[2]). For strategic planning activities, 18 out of 26 countries surveyed reported having a dedicated unit or team for strategic planning, while 11 indicated having a dedicated structure for visioning or foresight (OECD, 2023[1]).

Figure 2.1. Existence of dedicated units or teams in the CoG to support functions

Note: n=26. Respondents to the OECD survey were asked: “Is there a dedicated unit or team at the CoG to support the following functions?”.

Source: OECD (2023[1]), “Survey on strategic decision making at the centre of government”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

This chapter will explore the CoG’s role as a steward of setting the vision, strategic planning and prioritisation through the following structure:

Formulating a long-term vision and strategic planning.

Supporting priority setting.

Ensuring alignment across strategic documents.

Setting frameworks, standards, guidance and building capacity.

2. Formulating a long-term vision and strategic planning

Tackling challenges through long-term policy planning and strategising is more urgent than ever (Schiller, 2022[3]). Governments are faced with increasingly cross-cutting issues and crises while operating in a growingly complex environment (OECD, 2023[4]) and tightening fiscal landscape. This can create a risk for CoGs to overfocus on short-term risks and action. Yet, maintaining long-term vision is essential for countries to combat climate change, achieve their development ambitions.

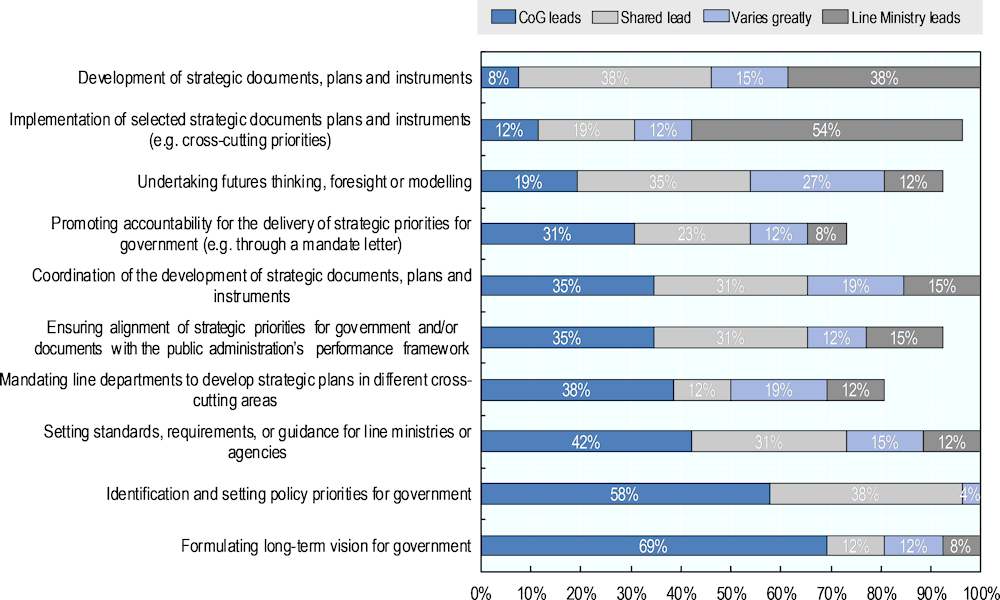

CoGs lead work on strategic planning and on the definition of the country’s long-term vision. They do so by defining overall government long-term visions, then translating this into shorter-term plans and action. The specific vision for the future of the country is the element that underpins most of the strategic planning process and the content of planning documents (OECD, 2018[2]). According to the Survey, in 69% of countries, CoGs lead the formulation of the government’s long-term vision, through national development plans for example. Such plans provide a common framework for all ministries to align specific actions.

Figure 2.2. CoGs are crucial for the development of a long-term vision for the country

Note: n=26. Respondents to the OECD survey were asked: “For each of the below activities regarding setting the vision, priorities and strategic planning, please indicate who has the primary responsibility”.

Source: OECD (2023[1]), “Survey on strategic decision making at the centre of government”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

In some circumstances, CoGs may be directly involved in the development of long-term plans for certain sectors, for example in infrastructure. According to data from the OECD 2020 Survey on the Governance of Infrastructure, in 2020, Finland, Greece, Lithuania, and Türkiye reported that the CoG is the primary institution responsible for assessing the country’s long-term infrastructure needs.

In a rapidly moving environment marked by disruptions and uncertainty, governments need to adjust their efforts continuously. Hence, long-term visions can benefit from periodic reviews and revision updates to ensure they remain relevant to changing circumstances and national trends (OECD, 2022[5]). Boxes 2.1 and 2.2 present the case of Finland and Latvia and their long-term-vision approaches.

Box 2.1. Latvia’s long-term National Development Plan

In 2020, the Latvian government and parliament approved the National Development Plan 2021-2027 (NDP2027). The plan defines the strategic goals, priorities, measures and indicative investment needs for seven years to achieve sustainable and balanced development. The NDP2027 sets 4 strategic goals for 2027 in 6 priority areas and 18 directions for key policies.

The creation of the NDP2027 was centrally led by the Cross-Sectoral Coordination Centre (Pārresoru koordinācijas centrs, PKC), a CoG entity currently integrated into the State Chancellery, with a mandate to develop a long-term strategic approach to public policymaking. The unique position of the PKC made it possible to develop the NDP coherently and collaboratively in accordance with the Latvian Sustainable Development Strategy 2030 and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

In addition, the NDP incorporates engagement with citizens, experts and other stakeholders. Over 150 different stakeholders work in 6 working groups organised by the PKC under the prime minister’s authority. These activities helped the CoG gather insights from different groups, providing valuable input for the plans while building advocacy.

The plan outlines the long-term vision and how it translates into operational plans, including information on indicators, responsible authorities and funding.

Finally, the NDP2027 was created in line with the resources available in the country. Policy changes are supported by public investment from the national budget, European Union (EU) funds and other financial instruments. In this context, abrupt crises might change financial possibilities, as was the case with the COVID-19 pandemic and the EU Recovery and Resilience Facility response to it.

Sources: ESDN (2020[6]) , Single Country Profile: Lativa, https://www.esdn.eu/country-profiles/detail?tx_countryprofile_countryprofile%5Baction%5D=show&tx_countryprofile_countryprofile%5Bcontroller%5D=Country&tx_countryprofile_countryprofile%5Bcountry%5D=16&cHash=3adce4de55ca14e7ef913a0bd8b1f355 (accessed on 11 May 2023); PKC (2020[7]), National Development Plan for Latvia 2021-2027, https://www.pkc.gov.lv/sites/default/files/inline-files/NAP2027__ENG.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2023); Ministru kabinets (2023[8]), Latvijas Nacionālais attīstības plāns 2021.-2027. gadam; Latvijas Republikas Valsts kontrole (2022[9]), Ar kādiem izaicinājumiem saskaramies, sagatavojot un īstenojot Latvijas Atveseļošanas un noturības mehānisma plānu? Situācijas izpētes ziņojums.

Box 2.2. Adjusting the course: Long-term and targeted planning in Finland

Finland’s strategic planning has been marked by a political tradition of coalition governments and a siloed public administration. As the number of parties involved in coalitions grew, attempts to capture all of their objectives in government programmes proved difficult.

In 2015, the government of Finland attempted to deviate from this trend, moving beyond siloed priorities with its new strategic government programme Finland Vision 2025. This system was built around 26 strategic objectives in 5 policy areas, complemented by a set of structural reforms. The government allocated EUR 1 billion to ensure the effective implementation of those key projects. This shift to a ten‑year approach, rather than solely focusing on a single parliamentary term, acknowledged the importance of time for the implementation of major, structural reforms. The changes appear to have been effective in delivering on policy goals.

Successive governments have followed the established practice around long-term visions to date. Prime Minister Sanna Marin’s 2019-23 government programme was developed based on long-term objectives, which translated into a cross-sectoral approach. The government identified and focused on four big “priority goals”. These strategic themes and priority goals were further specified in approximately 64 sub-goals with 70 indicators. The CoG can shape the governmental approach toward its programme, encouraging the definition of fewer but targeted policies, while developing a long-term vision within government programmes.

Sources: OECD (2022[5]), Centre of Government Review of Brazil: Toward an Integrated and Structured Centre of Government, https://doi.org/10.1787/33d996b2-en; Finnish Government (2019[10]), Inclusive and Competent Finland – A Socially, Economically and Ecologically Sustainable Society, Programme of Prime Minister Sanna Marin’s Government, 10 December 2019; Ross, M. (2019[11]), “The power of priorities: Goal-setting in Finland and New Zealand”, https://www.globalgovernmentforum.com/the-power-of-priorities-goal-setting-in-finland-and-new-zealand/.

Utilising strategic foresight for long-term visions and strategic planning

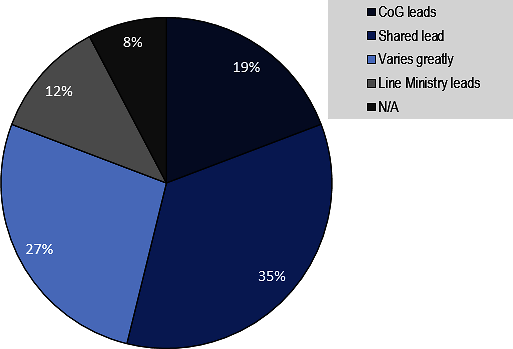

Approaches such as foresight and long-term insights can support the development of long-term visioning. Yet, the adoption of strategic foresight and related methodology in planning processes by CoGs remains low. According to the Survey, in 19% of countries, the CoG is primarily responsible for undertaking future thinking, foresight or modelling activities (OECD, 2023[1]).

Figure 2.3. Futures thinking, foresight or modelling are usually a shared responsibility

Note: n=26. Respondents to the OECD survey were asked: “For each of the below activities regarding setting the vision, priorities and strategic planning, please indicate who has the primary responsibility [undertaking futures thinking, foresight or modelling]”.

Source: OECD (2023[1]), “Survey on strategic decision making at the centre of government”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

In those that do, OECD research has shown that a central dedicated foresight unit can help integrate foresight into strategic planning processes, for example in Finland. Box 2.3 provides an example of New Zealand’s integration of long-term foresight insights into their planning processes. Box 2.4 provides an example of their foresight approach from Portugal. Australia has also piloted a long-term insights process into their planning approaches, recently released by the Prime Minister’s Office.

Box 2.3. Long-term briefings in New Zealand

New Zealand’s Public Service Act 2020 requires chief executives of government departments, independently from ministers, to produce a long-term insight briefing (LTIB) at least once every three years. The LTIB should explore future trends, risks and opportunities.

Figure 2.4. Long-term insight briefing process

The first round of LTIBs were presented to parliamentary select committees from mid-2022 to mid-2023. After parliamentary scrutiny, the LTIBs were made available in the public domain. Public consultation on draft briefings is a requirement of the process. Prior to the Public Service Act 2020, New Zealand’s senior policy community had discussed the challenges of building long-term issues and strategic foresight into policy formulation. It held workshops on a future policy heat map and policy stewardship. While there is no associated programme to build capability in strategic foresight, the LTIB requirement process may catalyse demand for strategic foresight capabilities. The second round of LTIBs is about to commence.

Sources: DPMC (2021[12]), Long-term Insights Briefings, https://www.dpmc.govt.nz/our-programmes/policy-project/long-term-insights-briefings (accessed on 10 May 2023), Author’s own elaboration for the figure based on DPMC (2021[12]), Long-term Insights Briefings, https://www.dpmc.govt.nz/our-programmes/policy-project/long-term-insights-briefings ; Author’s own elaboration for the figure.

Box 2.4. The Public Administration Planning and Foresight Services Network (RePlan): A lever for evidence-informed and inclusive planning and policymaking in Portugal

In 2021, the Portuguese government established an inter-ministerial network for planning and foresight services of the public administration. Its objective is to support the government in building and aligning strategies for cross-cutting issues.

Thus, in Portugal, the planning processes are underpinned by a wide range of sources of data and evidence. Yet, many inter-ministerial networks associated with the large range of planning instruments being enforced in Portugal can hinder the ability to explore synergies in the planning processes. Streamlining the number of networks and prioritising those that concern the whole-of-government are strategic priorities for RePLAN.

It acknowledges the role the CoG can play as a central leadership hub, to facilitate co-ordination, collaboration and co-operation across the public administration, including through the use of foresight in the planning process. Although RePLAN was de facto established in November 2022 and is still in its early stages, it has already identified some key success factors:

The establishment of a long-awaited convening platform that brings together different practices such as foresight offers an opportunity for synergies, increased efficiency and effectiveness in core governance areas such as strategic planning and policy evaluation.

A clear mandate, government empowerment and continuous political support.

The engagement of relevant stakeholders from civil society, academia and the private sector to drive evidence-informed and inclusive strategies and plans.

Source: Information provided by representatives of PlanAPP, Portugal.

Engaging with stakeholders to support strategic planning

Engaging with stakeholders is crucial to informing strategic planning, for example to bring in knowledge and expertise of others and to build collective buy-in. CoGs’ central positioning allows them to co‑ordinate the engagement of stakeholders to integrate different perspectives and harness expertise and support from a wide range of parties (Brown, Kohli and Mignotte, 2021[13]). A structured process which engages a wide audience helps ensure effective prioritisation, which is an important component of strategic planning (Shostak et al., 2023[14]).

First, CoGs can draw on the knowledge, expertise and experience of line ministries and other government agencies in strategic planning processes. This ensures that sectoral priorities are fed into the overarching strategies and helps line ministries to understand and support the government’s vision. CoGs can use different methodologies to engage with line ministries, including inter-ministerial meetings, committees and retreats/seminars at the highest levels.

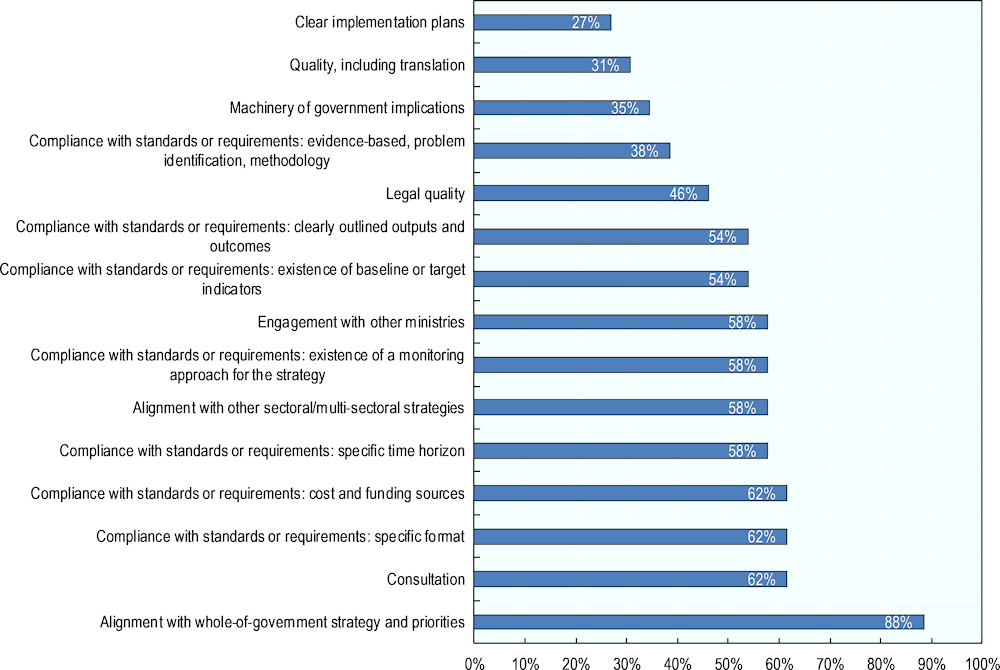

Experiences in OECD member countries show that when planning and prioritisation processes are open and underpinned by external stakeholder engagement activities, they can enhance legitimacy and buy-in for high-level national goals (OECD, 2020[15]). Box 2.5 demonstrates the importance of external engagement in Estonia’s long-term planning processes. While the CoG leads direct engagement in some cases, in others, it is responsible for ensuring that strategic documents or instruments prepared by other areas of the administration adhere to consultation requirements. This is the case in 62% of CoGs surveyed as part of the Survey.

Figure 2.5. CoGs review a wide range of aspects of strategy documents, plans or instruments

Note: n=26. Respondents to the OECD survey were asked: “Which aspects of strategy documents, plans or instruments does the CoG review?”.

Source: OECD (2023[1]), “Survey on strategic decision making at the centre of government”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

Box 2.5. Estonia 2035 action plan

The elaboration of Estonia 2035, the national long-term development strategy, was heavily underpinned by stakeholder engagement activities. It gathered views from almost 17 000 participants, including experts, researchers, politicians, business representatives and citizens, among others. Moreover, once a year, the CoG holds the Strategy Day of the Opinion Journey, an event aimed at fostering discussions among policymakers and other stakeholders to overview the achievement of the goals, co-create policies and, in particular, collect data and evidence within the framework of the Estonia 2035 strategy.

During the Strategy Day of the Opinion Journey in 2022, close to 140 discussions were chaired and organised by citizens, involving more than 1 000 people. Approximately 800 ideas and proposals on 12 topics were suggested by the participants. Evidence gathered through this activity will be submitted to the Government Office and will help inform the new version of the Estonia 2035 action plan.

The Government Office organised a roundtable seminar with discussion chairpersons and policymakers across the government to filter out the most relevant solutions and exchange views on what should be prioritised. This was also complemented by innovation sprints: around 40 public sector issues get solved annually by means of design methods facilitated by the Public Sector Innovation Unit of the Government Office.

The development of the action plan, together with a wide range of stakeholders, was important to gather the feedback, experiences and points of view from those who will be mostly impacted by the actions and priorities included in the strategy. In this context, it is important to ensure the constant inclusion and input of minorities and underrepresented groups, leaving no one behind and addressing all needs. Overall, working closely with different stakeholders can foster acceptance and support for the long-term national goals from stakeholders inside and outside the CoG.

Sources: Government Office of Estonia (2021[16]), Estonia 2035, https://www.valitsus.ee/en/node/31 (accessed on 10 May 2023); Government Office of Estonia (2022[17]), “The Strategy Day of the Opinion Journey brings together policy makers and discussion leaders from across Estonia”, https://www.riigikantselei.ee/en/news/strategy-day-opinion-journey-brings-together-policy-makers-and-discussion-leaders-across (accessed on 10 May 2023).

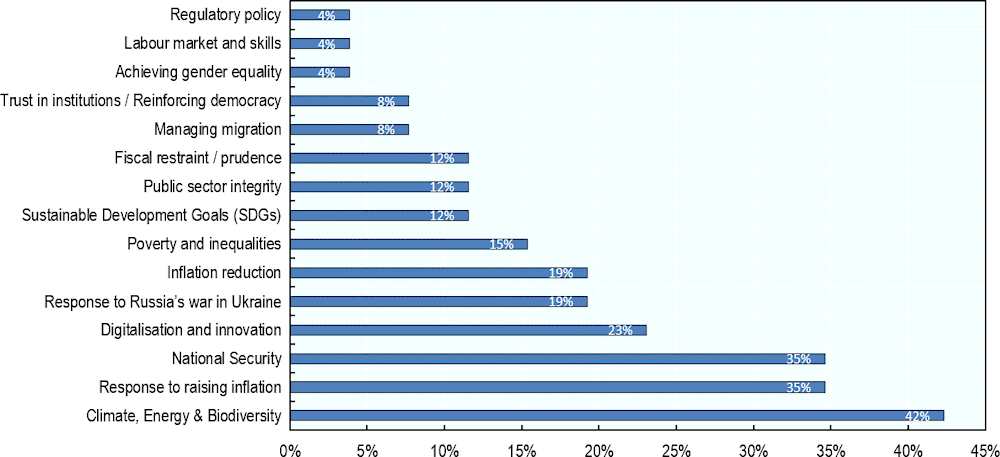

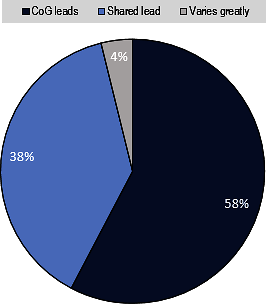

3. Prioritisation

Having a long-term vision provides an overarching frame for policy and resource allocation decisions. Governments must reconcile the immediate nature of challenges, such as rising inflation or the global energy crisis, with other long-term objectives and policies. This leads to the difficult task of prioritisation, which is a priority function for 88% of the CoGs surveyed in 2023. How the role is carried out varies greatly across surveyed countries, with 56% of CoGs leading this function and 40% sharing the lead with line ministries (OECD, 2023[1]).

Figure 2.6. Climate, energy and biodiversity rank among the top priorities for CoGs in 2023

Note: n=26. Respondents to the OECD survey were asked: “What are the top three strategic priorities that the CoG is mandated to lead this year (2023)?”.

Source: OECD (2023[1]), “Survey on strategic decision making at the centre of government”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

Figure 2.7. Setting priorities is at the core of the CoG’s work

Note: n=26. Respondents to the OECD survey were asked: “For each of the below activities regarding setting the vision, priorities and strategic planning, please indicate who has the primary responsibility [identification and setting policy priorities for government]”.

Source: OECD (2023[1]), “Survey on strategic decision making at the centre of government”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

Prioritisation is a crucial part of the early stages of strategic planning and policy formulation. It enables more realistic commitments and increases the likelihood of follow-through (OECD, 2020[15]). Inadequate prioritisation can create issues such as duplication across ministries or incomplete work (Plant, 2009[18]). Prioritisation approaches are often about creating alignment and collaboration of the public administration on what matters most.

Box 2.6. Prioritisation in New Zealand and the United Kingdom

A focus on outcomes approach in the United Kingdom

In 2010, the United Kingdom government created a dedicated cabinet sub-committee to identify the top priorities from a whole-of-government perspective. The previous approach, which asked individual departments to identify priorities, was replaced by the committee’s work to create centralised vision, relying on cross-departmental agreement and progress measurements.

Outcome delivery plans (ODP), introduced in 2021, lay out specifics of how each department works to achieve its priority outcomes. Instead of the narrow departmental priorities from the previous single department plans, ODPs emphasise interdepartmental work. This enables better outcomes for cross-cutting priorities and centralised monitoring.

The ODP is a helpful tool for the prime minister to oversee performance across institutions and to hold ministers and the civil service accountable. Key enablers were setting clear responsibilities and consistent co‑ordination mechanisms, and ensuring departmental equality in terms of visibility and contribution to the plans.

Boosting performance through focused priorities in New Zealand

New Zealand has long been considered at the forefront of public administration, experimenting with new ways of organizing and delivering public services. Even so, successive New Zealand governments had mixed results from using traditional public management tools to lift the performance of the public service and address cross-cutting problems that required multi-agency action. To address this, in 2012 New Zealand adopted the Better Public Services programme with a limited number of priorities and gathered institutions around their achievement. Better Public Services seeks to retain the strengths of our State services while addressing weaknesses such as fragmentation, government agencies working in silos, and inefficiencies.

The government of New Zealand met several times to agree on the ten most persistent social problems to be addressed by the public administration over a five-year term. The plan prescribed ambitious interagency performance targets. The New Zealand government generally let each group of agencies determine how best to achieve its target, with the exception of requiring all agencies to prepare and submit an initial action plan. Public reports were published every six months, making the group collectively accountable. Performance increased in all areas.

This approach required the public administration, including the CoG – the Department of the Prime Minister of Cabinet, the Treasury and the Public Service Commission – to help steer the new initiative. Commitment to the goals set out and a relatively stable political environment were key enablers.

Source: Using interagency co‑operation to lift government performance in Aotearoa New Zealand, ANZSOG; Scott & Ross, (2017[19]), Interagency Performance Targets: A case study of New Zealand’s Results Programme, IBM Center for the Business of Government, https://www.businessofgovernment.org/sites/default/files/Management%20Dr%20Rodney%20Scott.pdf

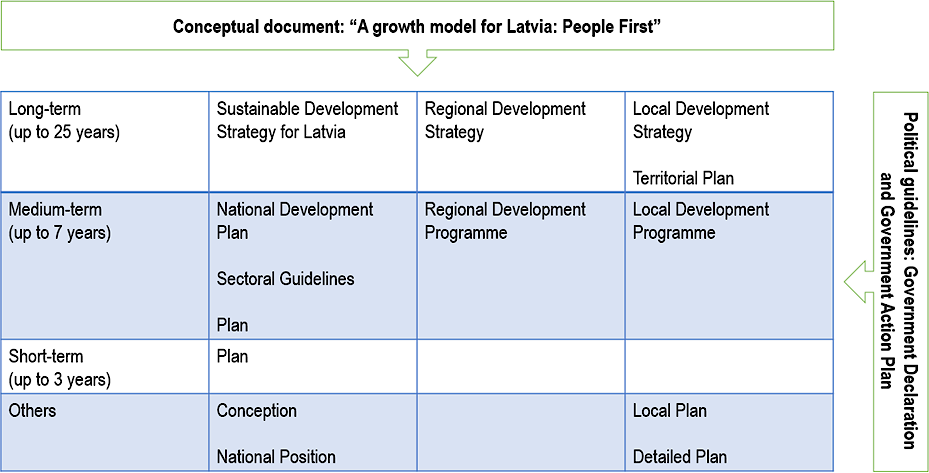

4. Ensuring alignment across the entire strategic planning ecosystem

The strategic planning ecosystem includes a series of processes, instruments, actors and interactions that come together to create effective strategic planning for government action. It is a priority for 92% of countries surveyed and requires consideration of the whole system (OECD, 2020[15]). In 35% of countries surveyed, CoGs play a leading role in this.

Complicated or ineffective planning systems can be a challenge, for example in cases where there is a high number of inherited plans from previous administrations in addition to new documents. Countries have identified several approaches to manage this issue. For instance, in some countries such as Finland, the Prime Minister’s Office is auditing over 100 planning documents with the aim to reduce their number. Another option to address this issue is the definition of a hierarchy across different instruments. Latvia (Box 2.7) has embedded this in its legal framework with the objective of increasing policy coherence and coverage (Government of Latvia, 2018[20]).

Box 2.7. Embedding in law the hierarchy of planning documents: Latvia

The 2009 Latvian Development Planning System Law outlines development planning principles, types of planning documents, their hierarchy and relations, and allocates responsibilities to institutions in the planning process. The law outlines specific requirements for development planning documents: strategic objectives and results, a description of existing problems and solutions, an impact assessment and future implementation and evaluation. The necessary financial resources and responsible institutions are also identified.

This clear hierarchy makes the whole system of planning documents easier to understand for both policymakers and the public. If used as a practical tool in daily policymaking, it can also promote synergies among different institutions and levels, thus contributing to better policy alignment, coherence and more efficient use of resources.

Figure 2.8. Conceptual model of growth for Latvia

Sources: OECD (2018[21]), Policy Coherence for Sustainable Development Country Profiles: Latvia, https://web-archive.oecd.org/2019-04-25/517370-Country%20Profile%20Latvia.pdf; Pārresoru koordinācijas centrs (n.d.[22]), Politikas plānošanas rokasgrāmata.

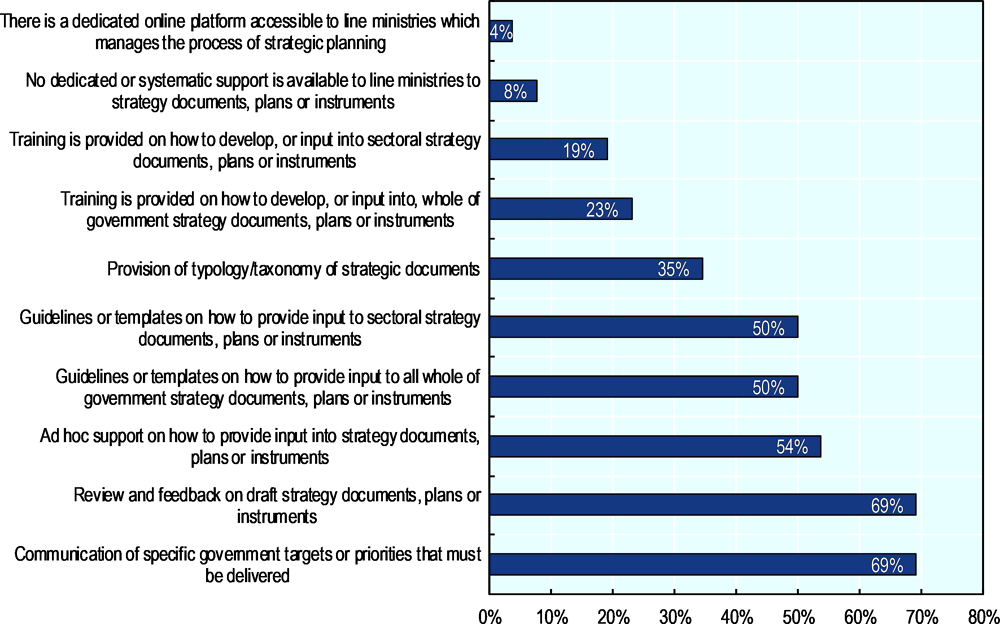

5. Setting frameworks, standards, guidance and building capacity

CoGs are naturally positioned to guide good public administration practices, including strategic planning. In 2023, 62% of surveyed CoGs indicated setting frameworks, standards, guidance and building capacity in strategic planning as top priorities. In 42% of the countries, CoGs are the lead structure for defining the standards, requirements or guidance for line ministries or agencies about setting the vision, priorities and strategic planning. The use of new or contemporary approaches, such as systems thinking, has increased in 42% of the surveyed CoGs (OECD, 2023[1]), through offering toolkits or handbooks for example. CoGs also provide reviews and feedback on draft documents in 69% of surveyed countries. Half of the CoGs develop guidelines or templates for strategic planning.

Figure 2.9. CoGs support line ministries and agencies in several ways

Note: n=26. Respondents to the OECD survey were asked: “What support does CoG provide to line ministries and other agencies to develop strategy documents, plans and instruments?”.

Source: OECD (2023[1]), “Survey on strategic decision making at the centre of government”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

6. Common challenges and enablers

Through a synthesis of information collected through country practices, desk research, interviews and the experiences shared by participants of the informal OECD Expert Group on Strategic Decision Making at the Centre of Government, the following key considerations can be identified:

Common challenges

CoGs are finding it more difficult to balance long- and short-term priorities and trade-offs. This is due to shifting national agendas, policy complexity and continued disruptions and crises. Relatedly, ensuring that planning documents are aligned is difficult even where there are clear hierarchy frameworks because of shifting priorities or cross-cutting issues.

Developing a long-term vision supported by key actors can be difficult in an increasingly polarised environment. CoGs might face a trade-off between defining a specific vision that only reflects a small share of the population and a broader vision that could be perceived as vague.

Dealing with cross-cutting issues requires a whole-of-government approach for the development of strategies and plans. However, administrations typically work in functional silos. CoGs are increasingly trying to overcome these silos through more collaborative planning approaches.

Engaging with citizens has proven to be a challenge for some CoGs. Several CoGs have identified low citizen participation in the long-term planning process as a challenge to inform the development of national priorities and strategies.

Key enablers

Clear roles and responsibilities around strategic planning processes and co‑ordination are key to effective strategic planning processes, along with the government’s national agenda clarity.

Putting in place the building blocks to support the CoG in addressing long-term commitments while delivering on short-term government priorities should be considered, for example in allocating budgets and resources dedicated to both long- and short-term priorities.

A clear framework for the hierarchy of high-level strategic plans can be useful to avoid inconsistencies and promote continuity across strategies.

CoGs should continue to use a collaborative strategic planning approach, including across ministries and with other stakeholders. The CoG’s convening power can support this including through periodic, face-to-face meetings where representatives from the CoG and ministries can address relevant topics or meet with experts and stakeholders.

Enhancing strategic thinking and planning capabilities in the administration is helpful, first and foremost for the CoG and across line ministries, through ministry planning focal points for example.

References

[13] Brown, D., J. Kohli and S. Mignotte (2021), Tools at the Centre of Government: Research and Practitioners’ Insight, University of Oxford, https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2021-09/Tools%20at%20the%20centre%20of%20government%20-%20Practitioners%27%20Insight%202021.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2023).

[12] DPMC (2021), Long-term Insights Briefings, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, New Zealand Government, https://www.dpmc.govt.nz/our-programmes/policy-project/long-term-insights-briefings (accessed on 10 May 2023).

[6] ESDN (2020), Single Country Profile: Lativa, https://www.esdn.eu/country-profiles/detail?tx_countryprofile_countryprofile%5Baction%5D=show&tx_countryprofile_countryprofile%5Bcontroller%5D=Country&tx_countryprofile_countryprofile%5Bcountry%5D=16&cHash=3adce4de55ca14e7ef913a0bd8b1f355 (accessed on 11 May 2023).

[10] Finnish Government (2019), Inclusive and Competent Finland – A Socially, Economically and Ecologically Sustainable Society, Programme of Prime Minister Sanna Marin’s Government, 10 December 2019.

[20] Government of Latvia (2018), Latvia: Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals, https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/19388Latvia_Implementation_of_the_SDGs.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2023).

[17] Government Office of Estonia (2022), “The Strategy Day of the Opinion Journey brings together policy makers and discussion leaders from across Estonia”, https://www.riigikantselei.ee/en/news/strategy-day-opinion-journey-brings-together-policy-makers-and-discussion-leaders-across (accessed on 10 May 2023).

[16] Government Office of Estonia (2021), Estonia 2035, https://www.valitsus.ee/en/node/31 (accessed on 10 May 2023).

[9] Latvijas Republikas Valsts kontrole (2022), Ar kādiem izaicinājumiem saskaramies, sagatavojot un īstenojot Latvijas Atveseļošanas un noturības mehānisma plānu? Situācijas izpētes ziņojums.

[8] Ministru kabinets (2023), Latvijas Nacionālais attīstības plāns 2021.-2027. gadam.

[4] OECD (2023), Governing Green from the Centre, OECD, Paris.

[1] OECD (2023), “Survey on strategic decision making at the centre of government”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

[5] OECD (2022), Centre of Government Review of Brazil: Toward an Integrated and Structured Centre of Government, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/33d996b2-en.

[15] OECD (2020), Policy Framework on Sound Public Governance: Baseline Features of Governments that Work Well, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c03e01b3-en.

[2] OECD (2018), Centre Stage 2: The Organisation and Functions of the Centre of Government in OECD Countries, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/gov/report-centre-stage-2.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2023).

[21] OECD (2018), Policy Coherence for Sustainable Development Country Profiles: Latvia, OECD, Paris, https://web-archive.oecd.org/2019-04-25/517370-Country%20Profile%20Latvia.pdf.

[22] Pārresoru koordinācijas centrs (n.d.), Politikas plānošanas rokasgrāmata.

[7] PKC (2020), National Development Plan for Latvia 2021-2027, Cross-Sectoral Coordination Centre, Latvia, https://www.pkc.gov.lv/sites/default/files/inline-files/NAP2027__ENG.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2023).

[18] Plant, T. (2009), “Holistic strategic planning in the public sector”, Performance Improvement, Vol. 48/2, pp. 38-43, https://doi.org/10.1002/PFI.20052.

[11] Ross, M. (2019), “The power of priorities: Goal-setting in Finland and New Zealand”, https://www.globalgovernmentforum.com/the-power-of-priorities-goal-setting-in-finland-and-new-zealand/.

[3] Schiller, C. (2022), Liberal Democracies Must Demonstrate Long-term Thinking and Acumen in Crisis Management, Bertelsmann Stiftung, https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/de/publikationen/publikation/did/liberal-democracies-must-demonstrate-long-term-thinking-and-acumen-in-crisis-management (accessed on 5 May 2023).

[19] Scott, R. and R. Boyd (2017), “Interagency Performance Targets: A Case Study of New Zealand’s Results Programme”, http://www.businessofgovernment.org (accessed on 6 February 2024).

[14] Shostak, R. et al. (2023), The Center of Government, Revisited: A Decade of Global Reforms, Inter-American Development Bank, Washington, D. C., https://doi.org/10.18235/0004994.