This chapter focuses on the co-ordinated and collaborative approaches that the centre of government (CoG) can use to steward cross-cutting policies and overall policy co-ordination. As no single institution or area in the government is responsible for delivering on such policy challenges, it is essential that CoGs build their stewardship and co‑ordination capacities. Many CoGs play key roles in enhancing policy development through co‑ordination, a long-term challenge. This chapter presents cases in practice through examples of taskforces and committees, detailing functions such as quality assurance and cabinet support. More contemporary approaches, including behavioural insight units and experimentation labs, are also discussed. Finally, this chapter discusses the ability of the CoG to directly enhance the quality of policy through review mechanisms, touching on examples such as frameworks, standards and guidance.

Steering from the Centre of Government in Times of Complexity

3. Co-ordinating and enhancing policy development

Abstract

Key messages

Successful policymaking in today’s environment requires more systemic, co‑ordinated and collaborative approaches than many governments are used to. In this context, centres of government (CoGs) are well positioned to steward cross-cutting policies and overall policy co‑ordination.

CoGs are increasingly and more directly involved in driving cross-cutting policies, for instance on climate issues. Clarity of roles between central units and line ministries is key; yet CoGs need to consider how they make coherent decisions and bring a cohesive vision to these issues.

Despite differences in the composition of CoGs, most play key roles in enhancing policy development, co‑ordination and anticipation to reduce the risk of policy conflicts and coherence. Common functions include quality assurance, co‑ordination and supporting cabinet decisions.

CoGs are also increasingly engaging directly with stakeholders in policy development, including through more novel approaches such as citizen assemblies and expert groups. Yet, this is challenging and the increasing two-way distrust can act as a barrier.

CoGs are starting to use more contemporary approaches to policy development, including behavioural insights units, experimentation and innovation labs. The goal is to make policy development more agile and responsive to public needs, reflecting the complexity of issues.

Considerations for CoGs include ensuring clarity of roles and responsibilities around policy development, engaging with the right actors, providing quality data and evidence and lifting the public administration’s policy development capacity.

1. Introduction

CoGs play a crucial role in contributing to democratic resilience, particularly in a context where governments are facing complex challenges and external shocks that are further exacerbated by low levels of trust (OECD, 2022[1]). Despite variations across countries and political system, many CoGs have similar responsibilities related to co‑ordination and policy development.

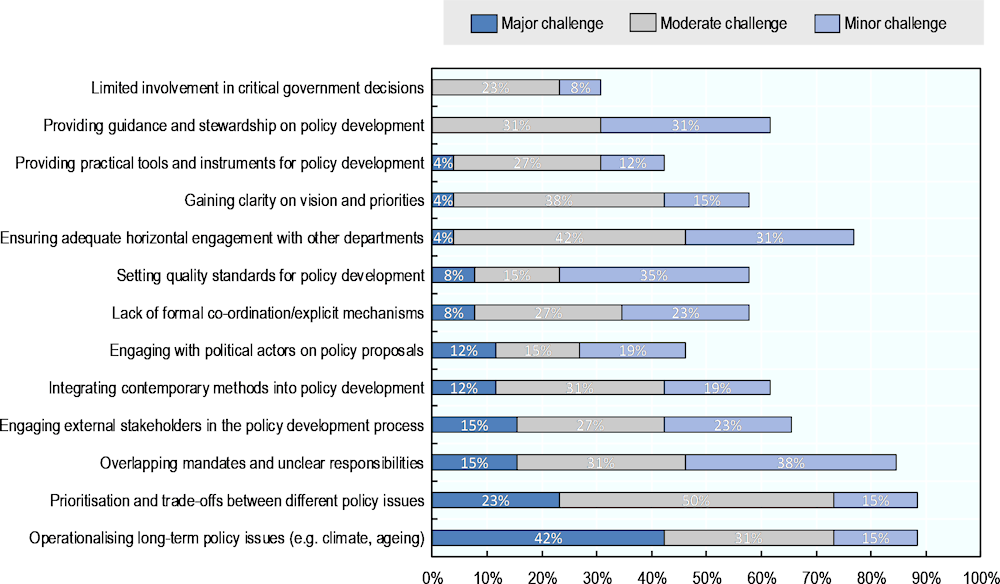

One way CoGs contribute to democratic resilience is by promoting whole-of-government policy responses that overcome traditional administrative barriers. The emergence of cross-cutting policy challenges such as climate change, rising social inequality and migration can no longer be addressed in silos and, as such, have proved challenging for governments (Hynes, Lees and Müller, 2020[2]). These challenges, in tandem with frequent external shocks, require whole-of-government policy responses that overcome traditional administrative barriers and institutionally-developed policy fields (Beuselinck, 2008[3]; Alessandro, Lafuente and Santiso, 2013[4]) that promote co‑ordinated action (OECD, 2021[5]). The OECD Recommendation of the Council on Policy Coherence for Sustainable Development (OECD, 2010[6]) provides guidance to this end; as do the SIGMA Principles of Public Administration (OECD SIGMA Programme, 2023[7]). Principle 3 highlights that good public administrations feature public policies that are coherent and effectively co-ordinated by the centre of government. As shown in Figure 3.1, supporting good public governance through co-ordination and policy development support touches a wide range of challenging areas for the CoG, including in particular operationalising long-term policy issues and prioritisation and trade-offs. By breaking down silos, fostering collaboration and ensuring coherent government actions, CoGs help governments reduce the risk of fragmented actions, duplication and low quality of services, and difficulty in meeting government goals and international commitments.

Figure 3.1. Challenges CoGs face in co-ordination and policy development

Note: n=26. Respondents to the OECD survey were asked: “To what extent are the following factors a challenge for the CoG in respect to co‑ordination and enhancing policy development?”.

Source: OECD (2023[8]), “Survey on strategic decision making at the centre of government”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

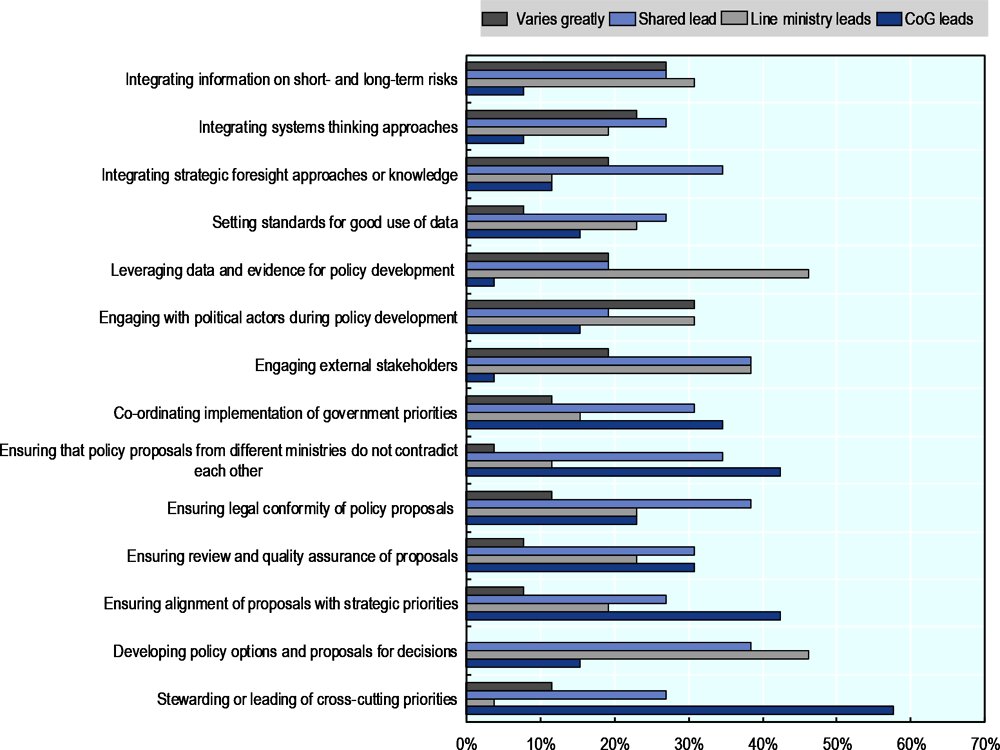

Figure 3.2 shows key policy development and co‑ordination activities and which entity (CoG or line ministries) holds the respective primary responsibility. In practice, CoGs often play a stewardship role in overcoming silos on cross‑cutting policies. In response to the survey (OECD, 2023[8]), 92% of the responding countries said that leading cross-cutting and whole-of-government policies is a priority for the CoG, while 61% co‑ordinate the broader implementation of policy action.

One of the CoGs’ most important responsibilities is translating political commitments into policies and coherent results. In 23 out of 26 countries, co‑ordination, including the alignment of policy to government priorities, is under the CoGs’ leadership (OECD, 2023[8]).

Figure 3.2. Responsibility for activities regarding co‑ordinating and enhancing policy development

Note: n=26. Respondents to the OECD survey were asked: “For each of the below activities regarding co‑ordinating and enhancing policy development, please indicate who has the primary responsibility”.

Source: OECD (2023[8]), “Survey on strategic decision making at the centre of government”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

This chapter addresses CoG practices around policy development in the following structure:

Leveraging mechanisms to support policy co‑ordination and engagement.

Enhancing policy development from the centre through contemporary approaches such as innovation, behavioural insights and experimentation.

Enhancing policy quality through review mechanisms for policies and legislation.

Providing frameworks, standards and guidance and building public sector capacity from the centre.

2. Levering mechanisms to support policy co‑ordination and engagement

CoGs utilise a range of mechanisms to support overall co‑ordination and alignment in policy development. These mechanisms can help align government action at all stages of the policy cycle and ensure there are appropriate resources. Co‑ordination mechanisms can also facilitate policy coherence and peer learning.

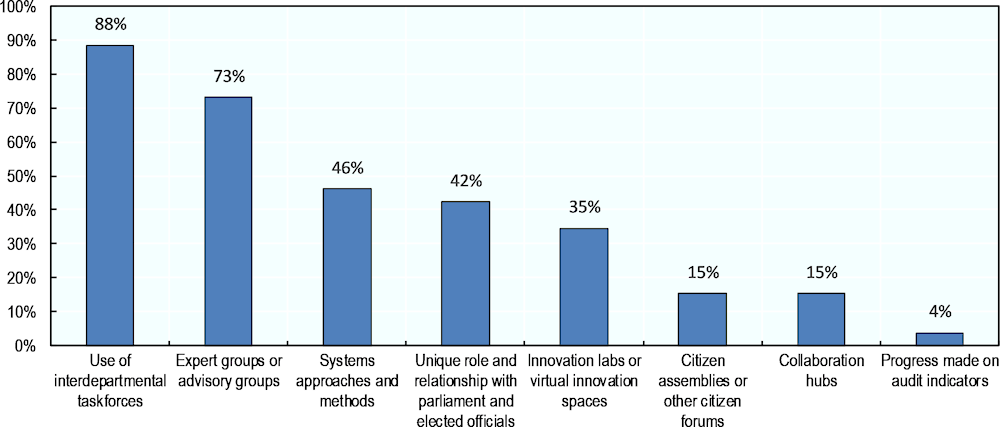

Figure 3.3 presents the various mechanisms used by CoGs for policy co-ordination. They include permanent or temporary taskforces/working groups and councils/committees, citizen assemblies, innovation labs and special relations with parliament and elected officials. Building structures responsible for cross-cutting and sectoral analysis can strengthen the analytical function and co-ordination of analysis overall, as the CoG in Poland has opted to do.

Figure 3.3. Mechanisms used by CoGs to support co-ordination

Note: n=26. Respondents to the OECD survey were asked: “What enabling mechanisms does the CoG leverage to support co‑ordination and coherence?”.

Source: OECD (2023[8]), “Survey on strategic decision making at the centre of government”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

Inter-ministerial co‑ordination mechanisms

Responses to the OECD survey (2023[8]) show that the three co‑ordination mechanisms CoGs most frequently use are interdepartmental taskforces, expert groups and advisory groups (Figure 3.3).

Permanent or temporary taskforces or working groups typically consist of representatives who meet to co‑ordinate and align on policy issues. Fifty-eight percent of countries have reported an increase in the use of ad hoc taskforces or other short-term groups to address specific issues or crises since 2019, while it has remained unchanged in 19% of cases (OECD, 2023[8]). Countries noted key considerations for taskforces including chair leadership, having the right representatives and ensuring there is a clear purpose. Box 3.1 outlines examples from Austria, Canada and Finland on the use of taskforces.

Box 3.1. Inter-ministerial co‑ordination in Austria, Canada and Finland

Inter-ministerial committees for co‑ordination in Canada

Cabinet committees in Canada carry out most of the day-to-day work of the Cabinet of Canada and examine proposals before they are submitted to the Cabinet. There are currently eight Cabinet committees, including one established in legislation, three sub-committees and three ministerial working groups linked to government priorities or current events. One of the committees’ tasks is to study the policy proposals submitted to them and then provide their recommendations to the Cabinet, which ratifies them. The Cabinet Committee on Agenda, Results and Communications is responsible for the government’s strategic programme and priority setting. It also monitors progress against the government’s priorities and considers strategic communications.

Governance arrangements and mechanisms for inter-ministerial co‑ordination in Finland

Finland has established a number of co‑ordination mechanisms to support strategy and decision-making supported by the CoG, particularly the Government Strategic Department. They bring together different line ministries and are usually shared by one or two lead ministries, depending on the topic. Finland has created:

Four permanent Ministerial Committees on Finance, Economic Policy, European Union (EU) Affairs and Foreign and Security Policy that play a key role in co‑ordinating government policies.

Thematic working groups focusing on a few government priorities (e.g. the Ministerial Working Group on Developing the Digital Transformation, the Data Economy and Public Administration) that help steer, monitor and implement those priorities.

Functional working groups on research and foresight.

The Conference of General Secretaries in Austria

In response to a constantly changing environment, the Austrian government established the practice of the Conference of General Secretaries. Introduced in 2018, the conference brings together high-ranking officials from various federal ministries. It aims to address common challenges, share best practices and co‑ordinate administrative policies across different policy areas.

The conference entails systematic preparation and monitoring of joint or overarching tasks and projects of federal ministries on presidential and cross-sectional matters, as well as on government programme issues. Such assignments and projects can also be assigned to the Conference of General Secretaries by resolution of the government as regards preparation, monitoring of implementation and monitoring.

Sources: Government of Canada (2020[9]), Machinery of Government, https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/transparency-transparence/mtb-ctm/2019/binder-cahier-1/1G-support-appuie-eng.htm (accessed on 31 October 2023); Government of Finland (2023[10]), Ministerial Committees and Working Groups, https://valtioneuvosto.fi/en/government/ministerial-committees (accessed on 31 October 2023); information provided by representatives of the Federal Chancellery of Austria (2023).

There is a risk of an excessive use or proliferation of inter-ministerial taskforces and committees, and CoGs should regularly review these. Box 3.2 provides an example from Australia.

Box 3.2. Inter-ministerial co-ordination structures in Australia

In 2020, the National Cabinet agreed to review ministerial councils and fora to rationalise and reset their structure and work programmes. The report to the National Cabinet set out recommendations on the following key themes: i) a streamlined intergovernmental structure; ii) other national bodies; iii) interactions with the National Cabinet infrastructure; iv) mirroring and building on the National Cabinet model; v) encouraging delivery and good process; vi) reducing bureaucracy; vii) maintaining a streamlined and fit-for-purpose structure.

Criteria and objectives for bodies were outlined and they were required to meet at least two of the three defined objectives for continued operation, which were also used later to assess if new ministerial meetings needed to be established. Proposed new fora should meet a minimum of two objectives:

1. Enable national co‑operation and consistency on enduring strategic issues: Focus on shared, complex and long-term policy areas where there are vertical interrelated roles between the different levels of government requiring sustained co‑operation for effective implementation.

2. Address issues requiring cross-border collaboration: Focus on policy areas and issues where the horizontal alignment and complementarity of government policy or service provision improves delivery of and access to services or employment opportunities. A recent example was the co-ordination required to facilitate efficient movement of freight across otherwise closed intrastate borders during the COVID-19 crisis.

3. Perform regulatory policy and standard-setting functions: Focus on issues related to shared legislative and regulatory requirements where a cross-jurisdictional mechanism must approve and create or update requirements for policies, standards or codes.

Source: Australian Government (2020[11]), Guidance for Intergovernmental Meetings, https://www.pmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/resource/download/guidance-intergovernmental-meetings.pdf (accessed on 11 September 2023).

The use of expert or advisory groups can leverage external insights and support the co‑ordination and development of policy. It is also prevalent for CoGs, with 73% of CoGs making use of expert or advisory groups (OECD, 2023[8]). Consisting of subject matter experts, academics, civil society organisations, private sector representatives and other relevant stakeholders, they can help ensure that policy decisions are based on evidence-based insights, technical expertise and practical experience.

Two examples of expert or advisory groups from Ireland and Iceland are outlined in Box 3.3. These groups are instrumental in ensuring quality policy development and providing valuable quality policies. Box 3.3 also outlines France’s establishment of a think tank to act as a group of experts for policymaking.

Box 3.3. Use of expert groups mechanisms at the centre for policy development

The Policy Council for Effective Policy Development in Iceland

Since its establishment in 2015, this policy council within the Government Offices serves as a co‑ordination and consultation platform to strengthen the administration’s capacity for effective policymaking. Composed of representatives from all ministries, the council aims to share experiences and creates training courses, tools and data to support officials involved in policymaking. The council:

1. Formulates criteria, including best practices, for strategic planning.

2. Provides advice, recommendations and suggestions to enhance skills and knowledge among Government Offices employees.

3. Strengthens and co‑ordinates working practices of ministries on policy development.

4. Establishes guidelines on how policies and plans should interact with funding, legislative proposals and parliamentary resolutions, ensuring alignment in policy implementation.

5. Serves as an active forum for promoting informed debates on future opportunities and threats.

Ireland’s National Economic and Social Council for better policies

The National Economic and Social Council (NESC) was established in 1973 and advises the Taoiseach (the prime minister of the Republic of Ireland) on strategic policy issues relating to sustainable economic, social and environmental development in Ireland. The members of the NESC are representatives of business and employers’ organisations, trade unions, agricultural and farming organisations, community and voluntary organisations and environmental organisations, as well as heads of government departments and independent experts. The composition of the NESC plays an important and unique role in bringing different perspectives from civil society together with the government. This helps the NESC analyse the challenges facing Irish society and develop a shared understanding among its members of how to tackle them. The Secretary General of the Department of the Taoiseach chairs the NESC meetings. At each meeting, the NESC discusses reports drafted by its secretariat. The NESC decides its work programme on a three-year basis, with inputs from the Department of the Taoiseach.

France Stratégie’s think tank for cross-cutting policy development

In 2013, government policy analysis body France Stratégie created an exchange platform to discuss and provide recommendations on social and environmental responsibility (RSE). The platform focuses on social, environmental and economic challenges at large, looking at issues such as United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), competitiveness and climate change. Recommendations to the government and to all stakeholders, including businesses and non-governmental organisations (NGOs), suggest priority actions and identify and disseminate good practices.

The platform gathers experts, including 50 members from the government, civil society, academia, trade unions, business organisations, NGOs, think tanks, education institutions, ministries and the Senate. Principles and rules for the functioning of the platform were formalised and agreed upon by all participants at the onset, including a charter for expressing diverging views. Mapping and identifying the right people to involve have been important tasks underpinning the platform’s success. Members meet during general assemblies several times a year and during specific working meetings.

The platform has enabled France Stratégie and, more broadly, the government to engage a wide range of expert views in a co‑ordinated manner for informing policy decision-making.

Source: OECD (2023[12]), Strengthening Policy Development in the Public Sector in Ireland, https://doi.org/10.1787/6724d155-en.

Broader stakeholder engagement and insights for policy development

Engaging with stakeholders throughout the policy development process is just as important as during the strategic planning process. Developing interconnected policy responses has become more challenging as more stakeholders are involved (Slack, 2007[13]). From 2019 to 2023, the number of stakeholders CoGs regularly liaise with (e.g. scientific experts, business associations and civil society organisations) has increased in 16 of the 26 surveyed countries (OECD, 2023[8]). Stakeholder engagement is the third most frequently cited major challenge for CoGs (42% of CoGs noted this as a major or moderate challenge) (OECD, 2023[8]). While many countries have consultation processes, some note two-way distrust and politicisation as potential key barriers to engaging meaningfully with civil society. The 2023 SIGMA Principles for Public Administration highlight in Principle 5 that a good public administration will feature active consultation of all key internal and external stakeholders and the general public during policy development (OECD SIGMA Programme, 2023[7]).

Even though line ministries are often responsible for stakeholder engagement, the CoGs often ensure consistent involvement of stakeholders at the different stages of policy development by setting standards or providing guidance. This is reinforced through the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Open Government (OECD, 2017[14]; 2022[15]). Three such examples of CoG practices are highlighted in Box 3.4.

Box 3.4. Engaging with stakeholders for better policy development

Engaging stakeholders through the Wellbeing Economy Forum in Iceland

Over the last few years, well-being-focused economic approaches have gained momentum and Iceland has proven to be among the leaders in striving to shift to a well-being economy. In this aspiration, on 14-15 June 2023, Iceland held its first Wellbeing Economy Forum.

The forum was organised and steered by the CoG (Prime Minister’s Office) together with the Directorate of Health and the city of Reykjavík. Its main objective was to connect stakeholders from different backgrounds in order to pursue innovative policy approaches aimed at improving well-being of society. In sharing various insights and practices across sectors, the forum brought together different stakeholders, including politicians, policymakers, scholars and experts from Iceland and worldwide.

As a member of the Wellbeing Economy Governments partnership, Iceland has demonstrated its emphasis on well-being and sustainability, incorporating a focus on increasing the quality of life in the government’s strategic plans. Moreover, the government of Iceland has formulated the country’s well‑being indicators and priorities; however, a comprehensive transition requires addressing a wide range of challenges. Therefore, such types of fora can not only highlight and re-emphasise governmental ambitions but also give a platform for collaborative efforts to address pressing economic, social and environmental challenges. The innovative ideas and policies on how to deliver sustainable well-being can be later deliberated and implemented by the CoG and administration. In addition, to have an impact, the support from senior leadership that promotes the forum both internally and externally is crucial. However, strong political patronage can also cause problems when there is a change of government. Currently, the Wellbeing Economy Forum is intended to be held annually.

A centre of excellence bringing in external voices to achieve SDGs in Romania

The centre of government in Romania continues to strive for and steward a public administration that is more forward-looking, innovative and apt for dealing with complex issues in a coherent manner. For example, the CoG is creating a Centre of Excellence for Public Administration in the field of Sustainable Development (CExDD) that seeks to cultivate a forward-looking mindset of the public administration that leverages the expertise and knowledge of a diverse range of stakeholders. The CExDD is a structure that can encompass research, education and dialogue on sustainable development, and help both seek new policy opportunities while also training and building capacity for their public sector staff. There is no similar structure at the central level. Romania is seeking to be the most competitive hub for dialogue on sustainable development in relation to public administration responsibilities, exercising European regional leadership in this field.

It is important that every structure or stakeholder is involved in the CExDD creation process. For this to happen, the CoG acknowledges the importance of raising awareness and the importance of sustainable development objectives across the administration and stakeholders. Furthermore, the achievement of the SDGs and implementation of policies also depend on a competent, efficient and quality public service. The CExDD will aim to be a platform that allows more collaboration with stakeholders and across the public administration, as a more contemporary approach to the usual mechanisms of the administration and in view of building staff capacity.

There is political determination and advocacy for this work, which supports the completion of the institutional architecture and design of the CExDD and use of contemporary techniques for the implementation of the National Strategy for Sustainable Development of Romania 2030. The CoG acknowledges that identifying and involving the most appropriate stakeholders is essential for a successful outcome of any such reform effort, and all the more so in co-creating this centre of excellence.

Driving such an ambitious effort is not easy. In setting up the CExDD, the CoG has faced a couple of challenges. First, it encountered administrative issues when identifying the legal framework for acquiring the technical assistance needed to design the architecture. The CoG then had to establish a list of stakeholders who could support this initiative and harmonise each stakeholder’s role in the process. Additionally, the design of the CExDD also required careful consideration, in view of the most effective setup to drive outcomes budget and inputs. The CoG focused on co-creative processes to help work through these challenges.

Fostering cross-sectoral co-ordination and transformation from the centre: Germany’s Alliance for Transformation

Considering a commitment to the 2021 coalition agreement and current transformation efforts, the German federal government launched the Alliance for Transformation (AFT) in 2022. As a discussion forum organised and steered by the Federal Chancellery, the main objective of the AFT is to develop a coherent long-term vision and propose ways to shape transformation efforts to make the country climate-neutral, more digital and more resilient. The AFT brings together around 45 representatives from various sectors, such as trade unions, the private sector, academia and civil society, and connects them with high-level decision-makers. This practice complements standard stakeholder meetings held in federal ministries, offering ways to have open conversations on complex issues.

All meetings begin with a personal debrief by the Chancellor on the current situation and government policies. In this context, the Chancellery is responsible, as the CoG, for organising and preparing the meetings. Although meetings take place several times a year, in-depth work is also done at a more technical level between the gatherings. The analysis and actionable recommendations of the group are presented in the next AFT high-level meeting to discuss their implications and implementation. Throughout the taskforce process, the Chancellery has a moderating and monitoring role to keep track of progress and reports back to the Chancellor.

The results of the first two AFT taskforces were presented in the third high-level meeting on 2 June 2023. One focused on the accelerated expansion of renewable energy and the transition to a climate-neutral economy, while the other dealt with targeting skilled labour needed for the energy transition. Both topics are fundamental for Germany’s transformation process and for maintaining global competitiveness. The latest high-level event, held on 23 November 2023, addressed the circular economy and its potential for economic growth, sustainability and resilience.

Fostering a successful mechanism such as the AFT can of course be challenging at times. Bringing together a range of stakeholders across sectors is no easy task; thus, the continued encouragement of open dialogues is a top priority. Translating the proposals into policy efforts is the key objective.

Sources: WEF (2023[16]), At the Forum Discussed the Conditions, Experiences and the Outcomes for Sustainable Economy, https://www.wellbeingeconomyforum.is/2022-forum (accessed on 11 September 2023); Information provided by representatives of the General Secretariat of the government of Romania; Federal Government of Germany (2022[17]), “Focus on climate-neutral economy, digitalisation and sustainable work”, https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/schwerpunkte/klimaschutz/alliance-for-transformation-2052454 (accessed on 11 September 2023).

Some CoGs are starting to use newer forms of engagement. One‑third of CoGs (35%) report using innovation labs or virtual innovation spaces to support policy co‑ordination. Additionally, CoGs are using citizen assemblies and fora to support more participatory and devolved policy processes. However, only 4 out of 26 CoGs surveyed (15%) report using these mechanisms for co‑ordination (see Figure 3.3).

CoGs in several OECD member countries have developed guidelines or toolkits for line ministries and agencies to design and foster innovative stakeholder engagement in policy development. France has for instance established the Inter-ministerial Centre for Citizen Participation (see Box 3.5) that offers strategic and methodological support to ministries on citizen engagement. Portugal’s CoG facilitates ePortugal and Portugal BASE, which provide transparency of information to citizens on government issues, services and procurement to build transparency. Further discussion on engaging with stakeholders can be found in Chapter 8.

Box 3.5. Supporting line ministry engagement with stakeholder engagement in France

In France, the Inter-ministerial Centre for Citizen Participation (CIPC) provides strategic and methodological supports to line ministries looking to increase stakeholder engagement in policy development. Created in 2019 within the CoG’s Inter-ministerial Directorate for Public Transformation, the CIPC offers support through training and capacity building on new methods of participation, recommendations and access to staff specialised in facilitating consultations. The CIPC focuses on enabling line ministries to go further than surveys or qualitative studies, which could result in merely the expression of opinions or measures of satisfaction. Rather, the focus lies in participatory methods being used to have citizens reflect and develop perspectives amongst themselves in a collaborative manner. The CIPC has piloted a specific platform (participation-citoyenne.gouv.fr) which allows citizen access to current public consultations, information about prior consultations and the impact of citizen contributions to previous consultation projects, with the aim of encouraging further engagement.

Source: Government of France (2023[18]), Le Centre interministériel de la participation citoyenne, https://www.modernisation.gouv.fr/associer-les-citoyens/le-centre-interministeriel-de-la-participation-citoyenne.

3. Enhancing policy development from the centre through contemporary approaches such as innovation, behavioural insights and experimentation

Governments must adapt to the new and complex policy challenges the public sector faces. Using innovative approaches for policy development is no easy task. The survey shows that integrating such methods into policy development practices is perceived as a major or moderate challenge by almost half (43%) of CoGs surveyed. This is because these methods at times conflict with current forms of governance or decision-making. Such methods can include public innovation such as labs, behavioural insights and experimentation, discussed below.

Innovation labs

Innovation labs, also known as policy labs or policy innovation labs, are specialised units or institutions that aim to foster innovation and promote effective policy design and implementation. Innovation labs can act as testing grounds, where novel ideas and concepts are examined, tested and refined before being applied in practice, thus lowering the risk of policy failures. Many CoGs lead or house innovation labs, or support innovation labs by providing funding or access to data. Sharing information is an important first step towards co-ordination (Shostak et al., 2023[19]). Latvia serves as an example of how a CoG uses an innovation lab for policy outcomes (see Box 3.6).

Box 3.6. Latvia’s Innovation Laboratory

The Latvian Innovation Laboratory (InLab) has become the main driver of innovation across the country’s public sector. Led by the State Chancellery, InLab brings together public employees who co‑create solutions to address long-standing horizontal issues. It promotes changes in the mindset of civil servants, putting a user-centred approach at the centre of its work.

InLab tests innovative methods for policymaking. In total, the laboratory has developed 47 prototypes or solution designs. Examples include the remuneration policy for medical personnel, the administrative simplification strategy, the future of work policy as well as the shadowing and entrepreneur programme.

InLab’s experience revealed that there are some critical factors to be met for success. Among those, high-ranking officials’ support is essential to fostering innovation in the public sector. In addition, a secured budget, constant improvement of the methodology and regional coverage are very important for continuous innovation activities. The State Chancellery is currently working on adding behavioural insights, systems thinking, foresight and design imagining approaches and expanding its scope in the regions of Latvia.

Source: OECD (2020[20]), Public Sector Innovation Laboratory, https://oecd-opsi.org/innovations/public-sector-innovation-laboratory/ (accessed on 11 September 2023); LV Portals (2022[21]), Spilgtākās inovācijas valsts pārvaldē: no inovāciju laboratorijas līdz e-valdības risinājumam, https://lvportals.lv/dienaskartiba/347540-spilgtakas-inovacijas-valsts-parvalde-no-inovaciju-laboratorijas-lidz-e-valdibas-risinajumam-2022 (accessed on 11 September 2023).

CoGs can also help to facilitate the adoption and replication of labs’ policy practices or innovation across government by providing guidance and resources. Additionally, they may use communities of practices to promote learning of good policy innovation practices. One example is the United Kingdom’s Policy Design Community (Box 3.7).

Box 3.7. The United Kingdom’s Policy Design Community for innovative outcomes

The United Kingdom has established a multidisciplinary policy design community as part of its innovative public policy efforts. It provides a collaborative network for policy design thinking and innovation practitioners from both central and local governments. This aims to create more effective civil servants, more meaningful outcomes and better services for citizens.

The community organises meetings and practice sessions several times a year. Public officials interested in policy design are encouraged to join the official mailing list and Slack communication platform channel, thus facilitating day-to-day information flow. The community regularly shares its practices on its official government blog.

Currently, the community brings together officials from more than 60 diverse governmental organisations. It also engages stakeholders outside the government, such as university researchers. In addition, the United Kingdom’s policy design community is expanding its activities by developing a policy design course for all policymakers, formalising policy design as a career path and establishing citizen co-design measures.

Source: UK Government (n.d.[22]), About This Blog, https://publicpolicydesign.blog.gov.uk/about-this-blog/ (accessed on 11 September 2023).

Behavioural insights

In many OECD member countries, behavioural insight (BI) units work with governments to apply behavioural insights to public policy. BIs draw from behavioural economics and psychology to understand how people make decisions and behave in specific contexts. These insights allow policymakers to design policies that account for behavioural biases and motivations, thus increasing the legitimacy and effectiveness of policy interventions. While some governments embed these units in line ministries, in many countries, such as Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom, BI units have been integrated into the CoG (OECD, 2018[23]). Box 3.8 provides an example on the use of BI in Canada for policy development.

Box 3.8. The Program of Applied Research on Climate Action (PARCA) in Canada: Informing decision-making through evidence from behavioural science

Canada recognises the need to achieve rapid and effective climate action and the importance of changing behaviours as a part of the solution. Thus, the CoG Impact and Innovation Unit (IIU), in collaboration with two ministries, launched PARCA, a behavioural insights-based approach to informing policy action on climate issues, situated in the Privy Council Office. PARCA generates behaviourally informed evidence to align government policy decisions with an accurate understanding of how Canadians think, feel and act in relation to climate change. It leverages the IIU’s centralised role in the government of Canada to maximise the impact by:

Generating data to understand how Canadians think, feel and act in response to climate change in order to identify the potential for promoting greater individual action.

Using experimental testing and evidence in the design of policy, programmes, regulations and communications.

Aligning priorities across government by connecting lead departments in climate-related areas to work on shared priorities, such as increasing uptake of climate-friendly home retrofits.

Exploring the feasibility of other opportunities to leverage findings from applied behavioural science to guide policy developments.

It consists of three phrases:

1. Ongoing national data collection gathers evidence about how Canadians think, feel and act in relation to climate change and identifies key problems of interest.

2. Rapid in-depth studies isolate drivers and barriers to desired behaviour changes and test potential solutions to identified problems.

3. In-field experiments test research findings in the real world in collaboration with trusted partners and build evidence for initiatives that are likely to produce meaningful outcomes at scale.

Findings inform lead policy analysis, programme, regulatory development and public communications in lead departments and support overall central management of the climate change agenda.

Source: Government of Canada (2023[24]), The Program of Applied Research on Climate Action in Canada, https://impact.canada.ca/en/behavioural-science/parca (accessed on 31 October 2023).

Experimentation from the centre

CoGs can also promote a culture of experimentation in policy development. They can do this through frameworks, guidelines and resources, enabling policymakers to design and pilot policy interventions and test their effectiveness on a smaller scale. Experimentation allows policymakers to gather evidence on the impact of policies, identify effective approaches and refine policies based on findings. Achieving this requires the capacity for policy prototyping and piloting, and appetite, support and capacity for innovation in the public sector (OECD, 2020[25]). Box 3.9 provides an example of the Slovak Republic’s CoG enhancing experimentation on policy issues through its new Research and Innovation Authority.

Box 3.9. Experimentation through the Research and Innovation Authority in the Slovak Republic

The Slovak Republic is acknowledged as an “emerging innovator”, with its innovation performance lagging behind most EU countries. Therefore, in recovering from the economic downturn caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the Slovak Republic has taken active steps in building its research, experimentation and innovation capacities. In this context, the Research and Innovation Authority (RIA) was established at the central Office of the Government in October 2021.

The objective is to centralise research and innovation to address key challenges in a more co‑ordinated manner. Its placement within the CoG enables advocacy from the highest level and the connection of field professionals with the country’s senior leadership. The RIA trials and experiments policy issues and enhances the government’s broader experimentation and innovation capacity. It also supports the Slovak CoG in decision-making and reforms broader innovation governance.

This is an example of how the CoG can enhance capacities such as experimentation and innovation.

Source: Government of the Slovak Republic (n.d.[26]), VAIA, https://vaia.gov.sk/sk/o-nas/vaia/ (accessed on 11 September 2023).

Additionally, broader approaches such as systems approaches are also being used by the government. Almost half of the surveyed countries (46%) report using systems approaches and methods to support co‑ordination. These approaches must be embedded into existing systems and mechanisms to have a lasting impact. This is a key reason why many CoGs are driving such practices and integrating this continues to be a main challenge for many CoGs.

4. Enhancing policy quality and alignment through review mechanisms for policies and legislation

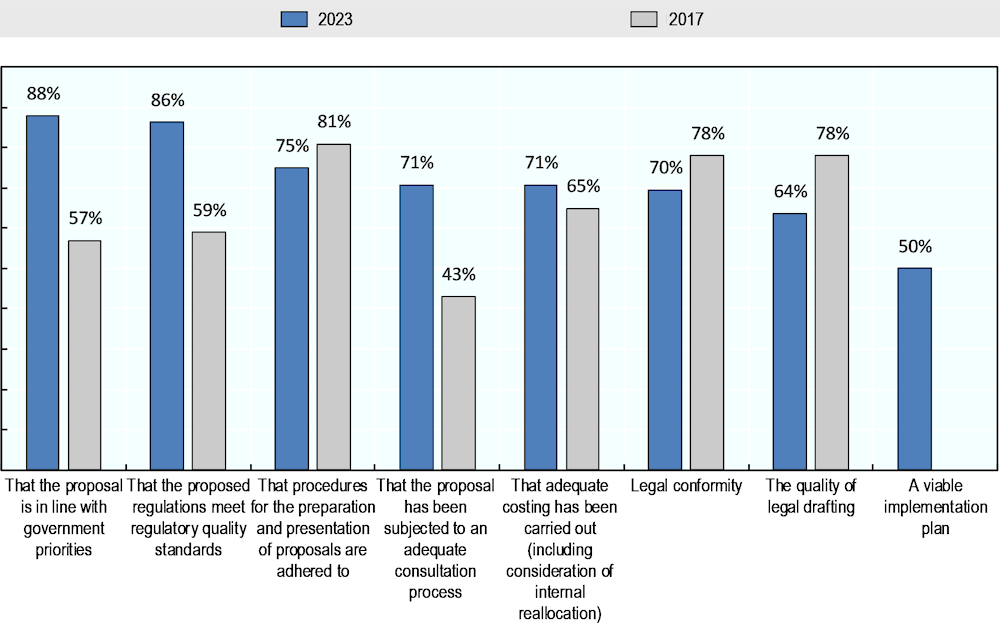

CoGs have always been gatekeepers of cabinet processes and decision-making (further discussed in Chapter 4). In most OECD countries, the CoG is responsible for reviewing and quality-controlling draft policy proposals, legislation or other policy documents submitted to the cabinet (Figure 3.4). They provide feedback on draft policies to line ministries and other agencies (OECD, 2023[8]). Their role can include:

1. Assessing against required processes, legal and regulatory compliance and analysis, and ensuring that adequate consultation has been undertaken.

2. Ensuring that policy proposals align with the overall government programme and priorities and reducing the risk of policy conflicts by making sure actors are considered at relevant policy stages.

3. Reviewing viability for implementation (less prevalent) and financial criteria aspects.

CoGs consistently try to align outcomes with broader government objectives, such as long-term sustainable development: 81% of CoGs ensure a co‑ordinated and coherent approach by communicating these objectives across the administration, reviewing proposals to align with overall government priorities (Figure 3.4).

Figure 3.4. Revision of policy proposals, legislation and other policy documents

Note: n=26 (2023). Respondents to the OECD survey were asked: “When reviewing draft policy proposals, legislation or other policy documents, which aspects does the CoG ensure?”. In 2017, legal conformity and quality of legal drafting were a single response option. The 2017 survey did not ask about the existence of an implementation plan.

Source: OECD (2023[8]), “Survey on strategic decision making at the centre of government”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris; OECD (2018[23]), Centre Stage 2 -The Organisation and Functions of the Centre of Government in OECD Countries, https://web-archive.oecd.org/2021-05-18/588642-report-centre-stage-2.pdf (accessed on 19 May 2020).

5. Providing frameworks, standards and guidance and building public sector capacity from the centre

Frameworks and standards play a crucial role in policy co‑ordination. They act as guidance to follow, ensuring that policies are aligned with the government vision and are of high quality. Sometimes, CoGs create the standards while, at other times, promote line ministry standards across the government. They can do this in various ways, including events, toolkits and websites (Brown, Kohli and Mignotte, 2021[27]).

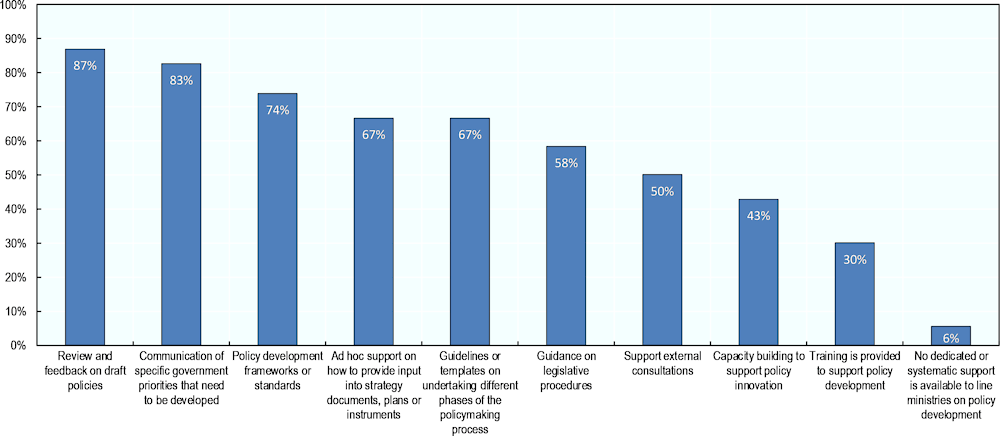

Figure 3.5 outlines the various roles CoGs play in this regard. Seventeen of 26 CoGs provide line ministries with policy development frameworks or standards. In 88% of countries, setting frameworks, standards, guidance and building capacity of the public administration in policy development is a priority for the CoG. In ten countries, the CoG is primarily responsible for setting standards, defining requirements and providing guidance to line ministries and agencies (OECD, 2023[8]). The survey also shows that CoGs provide support through guidelines and templates, review of draft policy proposals and ad hoc support to ministries, providing input into strategy documents, plans or instruments.

An area of support with notably less CoG involvement is capacity building. Training provision requires expertise and resources that the centre may not always have. Only 43% of CoGs focus on capacity building for innovation and less than a third of CoGs (30%) provide training on policy development.

Figure 3.5. Support provided by the CoG to line ministries and agencies in policy development

Note: n=26 (2023). Respondents to the OECD survey were asked: “What support does CoG provide to line ministries and other agencies in policy development?”.

Source: OECD (2023[8]), “Survey on strategic decision making at the centre of government”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

Box 3.10 outlines examples from Australia and New Zealand on CoG policy units that set standards and provide guidance to the public administration on policy development.

Box 3.10. Setting standards and providing guidance for enhancing policy development

New Zealand

The New Zealand government recognises that great policy advice is the foundation of effective government decision-making. It underpins the performance of the economy and the well-being of all people. The CoG established an initiative called the Policy Project, aiming to build a high-performing policy system that supports and enables good decision-making.

The initiative develops and promotes common standards, equipping policy practitioners, teams and agencies with tools, information and advice to develop their skills and capabilities in policy development, making use of tools such as newsletters for communication.

Australia

Australia’s prime minister and cabinet set standards and provide guidance and resources to the public administration on policy frameworks, proposal processes and policy impact analyses. The new policy impact analysis guidance helps policymakers reflect on how policies can affect people, businesses and community in order to better shape policy proposals, costs and benefits. The CoG has released a framework with standards on this and created forms, templates, guidance on processes, self-assessments and training videos.

Sources: New Zealand Government (2023[28]), The Policy Project, https://www.dpmc.govt.nz/our-programmes/policy-project (accessed on 31 October 2023); Australian Government (2023[29]), Australian Government Guide to Policy Impact Analysis, https://oia.pmc.gov.au/resources/guidance-impact-analysis/australian-government-guide-policy-impact-analysis (accessed on 31 October 2023).

6. Common challenges and enablers

Through the synthesis of information collected through country practices, desk research, interviews and the experiences shared by participants in the OECD informal Expert Group on Strategic Decision Making at the Centre of Government, the following key considerations can be identified.

Common challenges

As the external environment is becoming more challenging to navigate, CoGs are finding it more difficult to operationalise long-term policy ambitions and consider trade-offs on policy options.

Despite their value, there is a risk of over-proliferation of co‑ordination mechanisms and bodies. This can cause duplication of work, dilution of purpose or administrative burden.

Increasing co‑ordination and strategic capacities for aligned policy development across government is a long-term challenge. CoGs need to support good relationships with line ministries and navigate, at times, the personal agendas of individual ministers or ministries.

CoGs recognise the importance of balancing their role as stewards and the line ministry’s role in driving policies. This can be challenging as lines are blurred between co‑ordination and implementation.

Frameworks, standards and guidance work may stretch the CoG’s capacity. In some contexts, some non-CoG entities (e.g. line ministries or institutes of public administration) take this on. However, CoGs still need to agree, promote and assure such standards.

Common enablers

Political leadership and a clear strategic vision with well-communicated priorities are essential elements for the success of the CoG in policy co‑ordination and development.

To avoid overlapping mandates and unclear responsibilities and empower the CoG with regard to other actors, governments must ensure clear roles and mandates for policy development.

CoGs need sufficient resources and capacity to co‑ordinate across government, enhance coherence and steward policy development. Officials working at the centre need technical knowledge for the review of policy proposals and draft items, and technical skills such as the use of data, communication and project management. Additionally, relationship building and political navigation skills are important.

Policy challenges require collaboration across institutions and advice from external voices. Thus, CoGs should use fit-for-purpose mechanisms such as taskforces, working groups, advisory bodies and expert groups, with clear purposes, processes, timeframes and objectives. CoGs need to ensure that there is two-way trust, including with citizens, if this is to work.

Given their ability to work across all ministries and agencies, CoGs should identify and facilitate the regular exchange of practices, tools and material to foster continuous improvement of policy development processes.

Due to the constantly evolving policy development environment, CoGs should deploy an adaptive approach that is responsive to changing needs, emerging challenges and evolving circumstances.

References

[4] Alessandro, M., M. Lafuente and C. Santiso (2013), “The role of the center of government - A literature review”, Institutions for Development, Technical Note, Inter-American Development Bank, Washington, DC, https://publications.iadb.org/handle/11319/5988.

[29] Australian Government (2023), Australian Government Guide to Policy Impact Analysis, Office of Impact Analysis, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, https://oia.pmc.gov.au/resources/guidance-impact-analysis/australian-government-guide-policy-impact-analysis (accessed on 31 October 2023).

[11] Australian Government (2020), Guidance for Intergovernmental Meetings, Australian Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, https://www.pmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/resource/download/guidance-intergovernmental-meetings.pdf (accessed on 11 September 2023).

[3] Beuselinck, E. (2008), “Shifting public sector coordination and the underlying drivers of change: A neo-institutional perspective”, KU Leuven, Leuven, https://soc.kuleuven.be/io/pubpdf/IO02050140_2008_Beuselinck.pdf.

[27] Brown, D., K. Kohli and S. Mignotte (2021), Tools at the Centre of Government - Research and Practitioners’ Insight, https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2021-09/Tools%20at%20the%20centre%20of%20government%20-%20Practitioners%27%20Insight%202021.pdf.

[17] Federal Government of Germany (2022), “Focus on climate-neutral economy, digitalisation and sustainable work”, https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/schwerpunkte/klimaschutz/alliance-for-transformation-2052454 (accessed on 11 September 2023).

[24] Government of Canada (2023), The Program of Applied Research on Climate Action in Canada, https://impact.canada.ca/en/behavioural-science/parca (accessed on 31 October 2023).

[9] Government of Canada (2020), Machinery of Government, https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/transparency-transparence/mtb-ctm/2019/binder-cahier-1/1G-support-appuie-eng.htm (accessed on 31 October 2023).

[10] Government of Finland (2023), Ministerial Committees and Working Groups, https://valtioneuvosto.fi/en/government/ministerial-committees (accessed on 31 October 2023).

[18] Government of France (2023), Le Centre interministériel de la participation citoyenne, Ministère de la transformation et de la fonction publiques, https://www.modernisation.gouv.fr/associer-les-citoyens/le-centre-interministeriel-de-la-participation-citoyenne.

[26] Government of the Slovak Republic (n.d.), VAIA, Government Office of Slovakia, https://vaia.gov.sk/sk/o-nas/vaia/ (accessed on 11 September 2023).

[2] Hynes, W., M. Lees and J. Müller (eds.) (2020), Systemic Thinking for Policy Making: The Potential of Systems Analysis for Addressing Global Policy Challenges in the 21st Century, New Approaches to Economic Challenges, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/879c4f7a-en.

[21] LV Portals (2022), Spilgtākās inovācijas valsts pārvaldē: no inovāciju laboratorijas līdz e-valdības risinājumam, https://lvportals.lv/dienaskartiba/347540-spilgtakas-inovacijas-valsts-parvalde-no-inovaciju-laboratorijas-lidz-e-valdibas-risinajumam-2022 (accessed on 11 September 2023).

[28] New Zealand Government (2023), The Policy Project, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, https://www.dpmc.govt.nz/our-programmes/policy-project (accessed on 31 October 2023).

[12] OECD (2023), Strengthening Policy Development in the Public Sector in Ireland, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/6724d155-en.

[8] OECD (2023), “Survey on strategic decision making at the centre of government”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

[1] OECD (2022), Building Trust to Reinforce Democracy: Main Findings from the 2021 OECD Survey on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions, Building Trust in Public Institutions, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b407f99c-en.

[15] OECD (2022), Open Government Review of Brazil : Towards an Integrated Open Government Agenda, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/3f9009d4-en.

[5] OECD (2021), Better Governance, Planning and Services in Local Self-Governments in Poland, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/550c3ff5-en.

[25] OECD (2020), Policy Framework on Sound Public Governance: Baseline Features of Governments that Work Well, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c03e01b3-en.

[20] OECD (2020), Public Sector Innovation Laboratory, Observatory of Public Sector Innovation, OECD, Paris, https://oecd-opsi.org/innovations/public-sector-innovation-laboratory/ (accessed on 11 September 2023).

[23] OECD (2018), Centre Stage 2 -The Organisation and Functions of the Centre of Government in OECD Countries, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://web-archive.oecd.org/2021-05-18/588642-report-centre-stage-2.pdf (accessed on 19 May 2020).

[14] OECD (2017), Recommendation of the Council on Open Government, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/gov/Recommendation-Open-Government-Approved-Council-141217.pdf.

[6] OECD (2010), “Recommendation of the Council on Policy Coherence for Sustainable Development”.

[7] OECD SIGMA Programme (2023), “The Principles of Public Administration”, https://www.sigmaweb.org/publications/Principles-of-Public-Administration-2023.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2023).

[19] Shostak, R. et al. (2023), The Center of Government, Revisited: A Decade of Global Reforms, Inter-American Development Bank, Washington, D. C., https://doi.org/10.18235/0004994.

[13] Slack, E. (2007), “Managing the coordination of service delivery in metropolitan cities: The role of metropolitan governance”, Policy Research Working Paper, No. 4317, World Bank, Washington DC.

[22] UK Government (n.d.), About This Blog, https://publicpolicydesign.blog.gov.uk/about-this-blog/ (accessed on 11 September 2023).

[16] WEF (2023), At the Forum Discussed the Conditions, Experiences and the Outcomes for Sustainable Economy, Wellbeing Economy Forum, https://www.wellbeingeconomyforum.is/2022-forum (accessed on 11 September 2023).