This chapter provides an overview of European Structural and Investment Funds and Cohesion Policy in light of current trends in public investment. It highlights the importance of quality governance practices and administrative capacity in optimising public investment, and underscores the importance of strong administrative capacity among Managing Authorities in order to boost the effectiveness of European Structural and Investment Funds investment. It concludes with a description of the OECD diagnostic framework developed to support administrative capacity building in the context of managing EU funds under Cohesion Policy.

Strengthening Governance of EU Funds under Cohesion Policy

Chapter 1. Building administrative capacity for Cohesion Policy financing

Abstract

Note by Turkey: The information in this document with reference to “Cyprus” relates to the southern part of the Island. There is no single authority representing both Turkish and Greek Cypriot people on the Island. Turkey recognises the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC). Until a lasting and equitable solution is found within the context of the United Nations, Turkey shall preserve its position concerning the “Cyprus issue”.

Note by all the European Union Member States of the OECD and the European Union: The Republic of Cyprus is recognised by all members of the United Nations with the exception of Turkey. The information in this document relates to the area under the effective control of the Government of the Republic of Cyprus.

Introduction

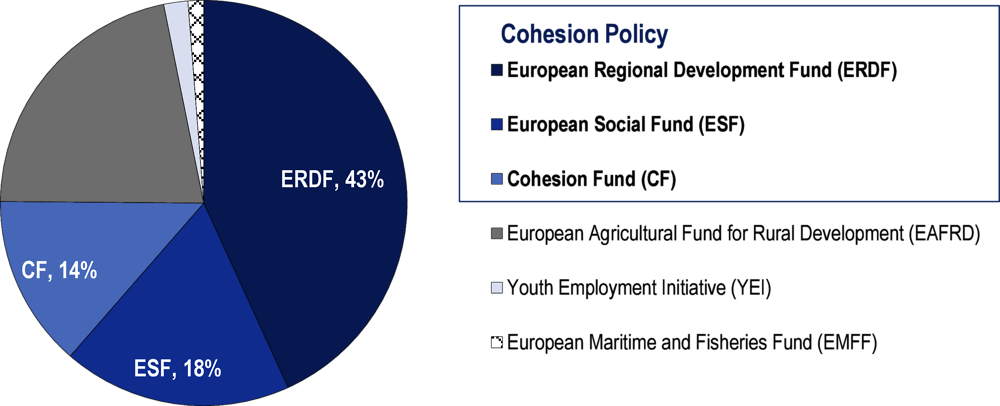

European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF) are the European Union (EU)’s main investment policy tool to support job creation and sustainable economic growth. In particular, Cohesion Policy – funded through the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), the European Social Fund (ESF) and the Cohesion Fund (CF) – accounts for a substantial portion of public investment in the EU, and plays a critical role in achieving EU and EU-Member State development objectives. Equipping Managing Authorities (MAs) with adequate administrative capacity is key to ensuring the effective and efficient implementation of investment programmes and to maximising ESIF potential to contribute to regional, national and EU development.

The importance of effective public and ESIF investment for countries and citizens

In the 2014-2020 programming period, EUR 461 billion, or over half of the total EU budget was allocated to the ESIF, which supports over 500 programmes (European Commission, 2019[1]). This allocation represents a 4.4% increase over the previous programming period in which the planned amount for ESIF was EUR 441 billion (European Commission, 2019[2])1. The funds make it possible to advance national and subnational-level investment in competitiveness, growth and jobs in EU Member States. It is estimated that by 2015 ESIF investment associated with the 2007-2013 programming period supported a 3% increase in GDP among EU 12 countries2, and a similar increase is expected by 2023 associated with the current programming period (European Commission, 2018[3]). The majority of ESIF – EUR 351.8 billion – are dedicated to funding EU Cohesion Policy, through ERDF, ESF and CF (Figure 1.1). As for the 2021-2027 programming period, the European Commission (EC) has proposed an allocation of EUR 373 billion to fund Cohesion Policy, channelled through ERDF, European Social Fund Plus (ESF+), and CF (European Court of Auditors, 2019[4]).

Figure 1.1. Overview of the European Structural and Investment Funds for 2014-2020

Note: For the post-2020 Programming Period, the European Commission has proposed that the Youth Employment Initiative (YEI) be integrated with the next iteration of the European Social Fund, the European Social Fund+.

Source: (European Commission, 2019[1]).

The investment financing provided through ESIF is significant for a number of reasons. First, while it aims to reduce inequalities between EU countries, it can also help reduce disparities within countries through targeted, and ideally place-based, investment. Second, encouraging productivity growth is critical to ensuring greater well-being as it can have a positive impact on income and jobs, health, and access to services. One ingredient for promoting such growth is investment in both “hard” (e.g. transport, energy, Information and Communication Technology, etc.) and “soft” infrastructure (e.g. research and development, human capital and skills, social and community services, etc.), a focus of this current programming period. Finally, since the global financial crisis, the public investment to GDP ratio has dropped in many EU countries (Figure 1.3). ESIF, especially Cohesion Policy funding, offers one way for EU Member States to ensure a reliable source of public investment finance, especially today when investment needs are rising.

The state of public investment: spending is picking up, but needs remain significant

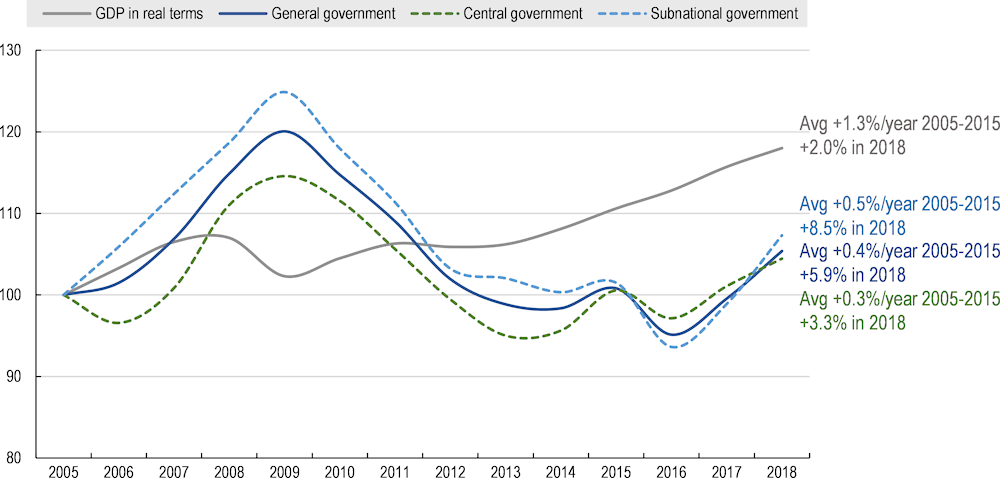

The 2008 global financial crisis put strong pressure on global investment (IMF, 2018[5]; OECD, 2018[6]). The fiscal consolidation strategies and austerity packages that followed the crisis in OECD member countries strongly affected public investment, which was mainly used as an adjustment variable (OECD, 2011[7]; 2013[8]). This also holds true in the European Union. Of the EU 28 countries, public investment has declined since the 2008 crisis. There was a stabilisation between 2012 and 2016, but this was followed by a slight decline in 2015, which can be partially explained by fiscal consolidation, as well as the impact of ESIF. According to the European Investment Bank (EIB), in recent years and among countries that are heavily dependent on ESIF, these funds accounted for around two-fifths of public investment, or nearly 2% of GDP. This caused them to suffer from a “cliff effect” suddenly turning negative after the 2015 deadline for payments under the 2007-2013 programming period (EIB, 2016[9]). Entering the 2014-2020 programming period, and since 2017, public investment started to rise, as countries and regions implement ESIF investments (Figure 1.2). Nevertheless, according to the 2018/2019 EIB report, while public investment is gradually picking up, it remains low. In particular, the fall in government infrastructure investment was most pronounced in countries subject to adverse macroeconomic conditions and more severe fiscal constraints (European Investment Bank, 2019[10]).

Figure 1.2. Public investment in EU-28 from 2005 to 2018 (change in real terms)

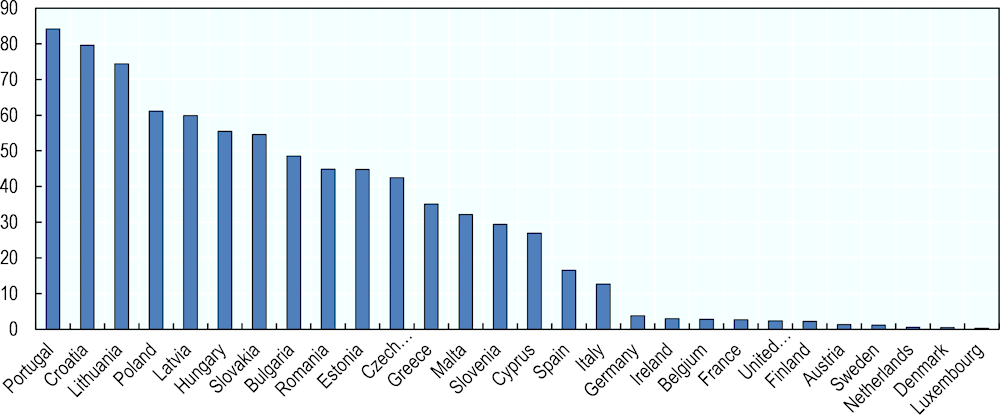

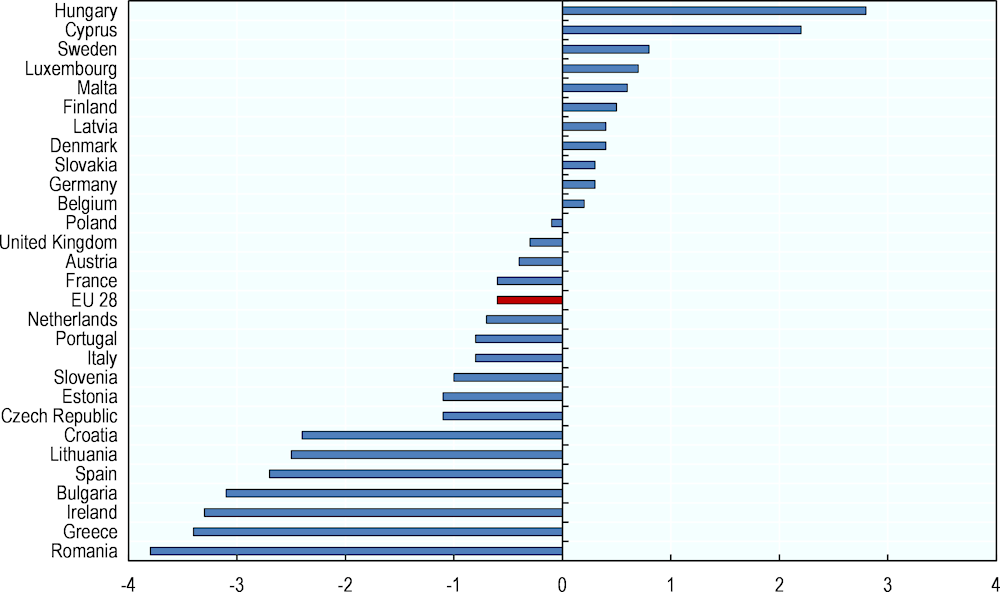

On average, public investment in the EU 28, as a share of GDP, decreased by 0.6 percentage points between 2008 and 2018 (Figure 1.3). Looking at each country, this drop has been particularly large in some EU Member States that are also major recipients of ESIF funding (e.g. Bulgaria, Croatia, Greece, Lithuania, Romania, and Spain).

Figure 1.3. Many governments in the EU have reduced public investment since the crisis

Note: The 2018 investment-to-GDP ratio for France and the Netherlands are provisional.

Source: Authors’ calculation based on (Eurostat, 2019[11]).

Meanwhile, there are significant needs for investment expenditure by all levels of government. It is estimated that between 2016 and 2030, approximately USD 95 trillion in public and private investment in energy, transport, water and telecommunications infrastructure will be necessary to support growth and sustainable development given the profound economic and demographic changes across the globe (OECD, 2017[13]). This is equivalent to about USD 6.3 trillion per year in the next 15 years. To this should be added an additional USD 300 billion annually if climate concerns are taken into consideration (OECD, 2017[13]); and in the EU, a further EUR 100-150 billion will be needed between 2018 and 2030 to bridge an investment gap in social infrastructure3 (European Commission, 2018[14]). The sticking point, however, is that investment in global infrastructure currently amounts to about USD 2.5 trillion per year (McKinsey Global Institute, 2016[15]; Brookings Insitution, New Climate Economy, and Grantham Research Insitute, 2015[16]). In addition, investment in physical infrastructure alone is not enough to secure regional growth and development – it is only one of many contributing factors. It is just as important to ensure effective investment in “soft infrastructure” such as a robust business environment and appropriate human capital formation. Many, if not all, of these hard and soft infrastructure needs are captured in the EU’s 11 Thematic Objectives (investment priorities) for the 2014-2020 programming period (European Commission, n.d.[17])4.

A growing body of work points to the positive effects of public investment on growth, and OECD research shows that countries with higher levels of public investment increase their productivity faster than countries with lower levels of public investment (Fournier, 2016[18]). In the long-run, increasing the share of public investment in primary government spending by one percentage point could increase the long-term GDP level by about 5% (Fournier, 2016[18]; OECD, 2013[8]). Several studies show that improving the management of public investment can also lead to substantial savings and enhanced productivity (OECD, 2013[8]; IMF, 2015[19]; McKinsey Global Institute, 2016[15]; McKinsey Global Institute, 2013[20]). Some estimates show that it is possible to generate savings of about 40% on infrastructure projects by making project selection, delivery, and the management of existing assets more effective (McKinsey Global Institute, 2016[15]; 2013[20]).

EU Cohesion Policy financing: its benefits and challenges

ESIF are used to finance investment dedicated to enhance economic and social development, reduce regional imbalances and contribute to meeting the development targets outlined in the Europe 2020 strategy, which emphasises smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. They have helped reduce the impact of the double dip recession, making a substantial contribution to the current recovery (European Commission, 2018[3]). For the five countries participating in this project, ESIF remains a major source of public investment for projects designed to stimulate economic development, sustain SMEs, and boost entrepreneurship and employment. Designed to reduce infra- and intra-regional disparities, and more generally to improve inclusion and well-being, Cohesion Policy thus represents the “visible hand” of the EU. The EC provides many examples of successful projects funded through ESIF: for example, ESIF financing has been used to reduce the energy consumption of public and private buildings in Bulgaria and to build modern motorways in Greece. In Croatia, ESIF is providing valuable support to improve the competitiveness of SMEs. ESIF help reduce the number of jobless households in Lublin, Poland, and have facilitated access by more than 750 000 people in Spain to improved basic services (European Commission, n.d.[21]).

Within ESIF, Cohesion Policy is a pillar of the EU’s effort to help governments make a tangible and lasting difference in citizen lives by closing socio-economic disparities. Cohesion Policy investments represent one third of the total EU budget and have funded the equivalent of 8.5% of government capital investment in the EU (European Commission, 2019[1]). While all EU Member States benefit from Cohesion Policy funding, its scale and relative importance as a source of development funding varies – representing up to or over 80% of public investment in some countries and less than 10% in others (Figure 1.4). Successfully managing the investment opportunities and resources that Cohesion Policy funding offers is a challenge, and requires effective administrative capacity of the investment cycle.

Figure 1.4. Cohesion policy funding as an estimated share (%) of public investment, 2015-2017

Partnership Agreements (PAs) negotiated between the EC and Member States set out national-level ESIF investment priorities. PAs are designed to achieve the 11 EU Thematic Objectives (TOs) for 2014-2020 via a series of sectoral or thematic, national and regional, Operational Programmes (OPs). PAs also establish an indicative annual financial allocation for each OP. Across the EU, responsibility for managing and implementing OPs is assigned to institutions designated as Managing Authorities (MAs). MAs are usually housed in Ministries, often as specific units. EU Member States can also delegate functions to regional administrations, creating regional MAs with responsibility for ESIF in their territory. MAs, both national and regional, are quite diverse, representing the central and the subnational government levels, including states (in federal countries) and regions.

The operations of each MA is governed by a Management and Control System (MCS) that sets the institutional and legal framework for ESIF investment and OP implementation, as well as the common rules, procedures and monitoring mechanism in a country (Box 1.1). MAs are responsible for a range of activities that require technical knowledge and a broad array of professional competencies. They frequently operate in a tightly controlled legislative and regulatory environment where processes and procedures are clearly set out in order to minimise the potential for error or fraud. MAs can delegate some of their activities to Intermediate Bodies (IBs) while still remaining responsible for overall governance. Beneficiaries are the legal entities, usually businesses, government authorities (e.g. line ministries, agencies, city or municipal governments, etc.), non-governmental organisations (NGOs), or universities which apply for and can receive ESIF financing for a project designed to align with one or more TOs referred to in the OPs.

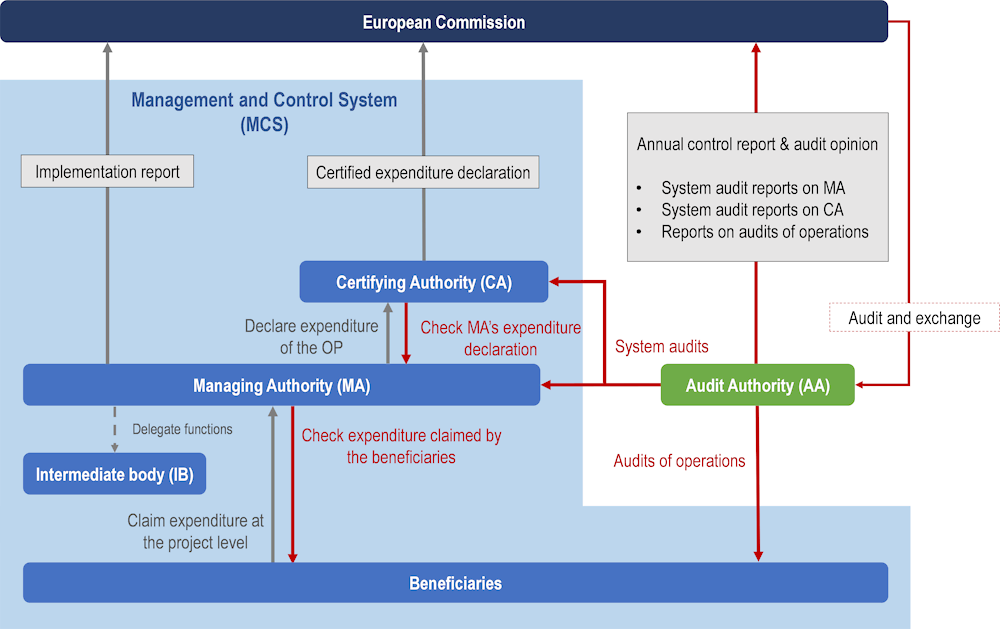

Box 1.1. The Management and Control System and key functions of different authorities

ESIF funding is implemented under a ‘shared management’ system, which means the European Commission entrusts the Member States with implementing programmes at the national level. The Member States have primary responsibility for setting up a Management and Control System (MCS) that complies with the requirements of EU Regulations, while the EC plays a supervisory role by satisfying itself that the arrangements governing the MCS are compliant (Figure 1.5). This ‘shared management’ model creates a complex system of multiple checks where EU, national and programme-level bodies participate in a range of internal and external management and control activities. The MCS include all the ex-ante financial controls (i.e. before the EU claims), while the audit bodies carry out ex-post controls (i.e. after EU claims).

Figure 1.5. Management and Control System in Cohesion Policy implementation: Structure and activities

Note: Lines and texts in red suggest all the checks and control activities; Cohesion Policy expenditure is also subject to audit by the European Court of Auditors, although this is not visually presented in the graph.

Source: Authors’ illustration based on (Byrne, 2014[23]; European Court of Auditors, 2013[24]).

Management and control activities of different entities

Managing Authorities (MAs) are responsible for granting and appraising applications, selecting projects for funding, managing administrative and on-the-spot verifications, authorising payments, collecting data on each operation, and establishing anti-fraud measures. In addition, MAs should provide guidance and support to beneficiaries.

Certifying Authorities (CAs) are responsible for making declarations to the EC and verifying the accuracy of programme accounts. They are also involved in procedures for certifying interim payment applications to the EC. CAs are also responsible for maintaining the computerised accounting records for each operation (e.g. amounts withdrawn, recovered, etc.).

Audit Authorities (AAs) ensure the effective functioning of an OP’s management systems and internal controls. In most cases, AAs are independent of EU funding offices and ministries, generally associated with State chancelleries, Ministries of Finance or Supreme Audit Institutions. AAs themselves are subject to the audit by the European Commission DG Audit and the European Court of Auditors.

MAs may entrust some of their management functions for the OP to one or more Intermediate Bodies (IBs). IBs can be line ministries, regional authorities, local authorities, regional development associations or other public or private bodies.

Beneficiaries are legal entities that receive EU funding, and are usually businesses or government authorities (e.g. line ministries, agencies, city or municipal governments, etc.), but sometimes also civil society organisations, universities, etc. Beneficiaries are responsible for ensuring a clear audit trail throughout the project delivery cycle and providing project information to other authorities in the MCS.

Quality governance contributes to optimising public investment spending

Evidence suggests that institutional quality and governance processes affect the expected returns to public investment and have a positive influence on the capacity of public investment to leverage private investment, rather than to crowd it out (OECD, 2018[26]). Thus, the quality of government and governance at all levels is a key factor in whether cohesion investment translates into greater growth (OECD, 2013[8]).

Meanwhile, the impact of public investment depends largely on how it is managed. If well managed, it acts as a catalyst to promote growth and attract private investment. Conversely, inefficient public investment processes can lead to suboptimal outcomes. Through its Public Investment Index assessment, the IMF points out that around 30% of the potential gains from public investment are lost due to inefficiencies in public investment processes (IMF, 2015[27]). Poor local institutions and government quality can affect investment processes by generating development strategies that are "good looking, but without substance", often promoting the interests of specific political and/or economic groups and resulting in an ineffective use of significant but scarce financial resources (Crescenzi and Giua, 2016[28]).

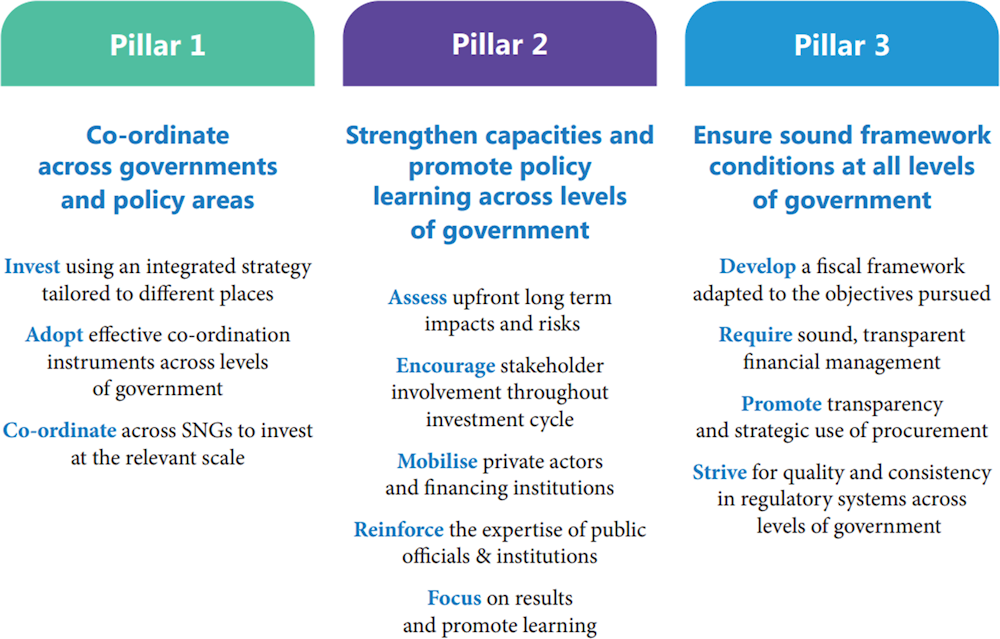

Governance mechanisms and good institutional conditions support public spending and investment

OECD and European countries have a long tradition of using different mechanisms5 to ensure that governance practices support public spending and investment that contributes to regional development. To help national and subnational governments more effectively invest public funds, particularly in light of declining resources and increasing needs, in 2014 the OECD Council adopted the Recommendation on Effective Public Investment across Levels of Government. The Recommendation is founded on three Principles for Action, which are grouped into a series of 12 recommendations. These focus on governance for investment practices, and are intended to guide policy and decision makers at all levels of government as they design and implement public investment strategies (Figure 1.6).

Figure 1.6. Recommendation on Effective Public Investment across Levels of Government: Principles for Action

Notes: For the full text of the OECD Recommendation on Effective Public Investment across Levels of Government, please see (OECD, 2014[29]); For the Toolkit for Implementation please visit https://www.oecd.org/effective-public-investment-toolkit/.

Source: (OECD, 2019[30])

The importance of good institutional conditions and governance for the efficient use of EU funds has been widely cited in the academic literature (De la Fuente, 2002[31]; Ederveen, de Groot and Nahuis, 2006[32]; Ederveen et al., 2003[33]) and dovetails with other findings regarding the importance of quality governance and government for effective investment spending (European Commission, 2018[3]). Survey data from 202 EU regions stresses that the quality of regional governance can act as a key determinant for the effective use of EU funds (Charron, Dijkstra and Lapuente, 2014[34]); and in Italy, for example, heterogeneity in regional administrative capacity has been linked to greater or lesser success in absorbing Structural and Cohesion Funds (Milio, 2007[35]).

Defining administrative capacity building for ESIF investment

Article 18 of the Common Provisions Regulation on ESIF emphasises the inter-related nature of the challenges facing EU Member States, from environmental and energy concerns to social inequality (European Union, 2013[36]). The projects funded through ESIF are, thus, intended to be integrated, multi-sectoral and multi-dimensional. As such, the guidance to MAs for the 2014-2020 period is correspondingly detailed in order to facilitate achieving these objectives. For example, for the 2014-2020 programming period, the volume of rules for Cohesion Policy alone runs to over 600 pages of legislation and 5 000 pages of guidance (European Commission, 2017[37]). The European Commission High Level Expert Group that monitors simplification for beneficiaries of ESIF for the next programming period acknowledged that excessive and overlapping guidance at the EU level “has long passed the point of being able to be grasped either by beneficiaries or by the authorities involved” (European Commission, 2017[37]). The simplification of ESIF guidance is a key aspect of the post-2020 period.

Investment and administrative capacity

Quality governance for successful ESIF investment depends on a variety of factors. Certainly, it depends on ensuring good institutional conditions. But it also depends upon various capacities, including investment capacity (Box 1.2) and administrative capacity. In practical terms, the importance of capacity has been supported by findings indicating that, for the EU 12, the planning and implementation for Structural Funds was affected by weak coordination, high turnover of staff, lack of skills and frequent institutional change in the first two framework periods after accession (Bachtler and McMaster, 2008[38]; McMaster and Novotny, 2005[39]). This illustrates the fundamental impact of human resource management and organisational development on administrative capacity. While time, experience and institutional memory appear to help MAs address these weaknesses, this pilot action highlights the room to support MAs all along the learning curve, regardless of their level of experience, and the value in creating opportunities for MAs to learn from one another.

Maximising the effectiveness of ESIF requires public servants with the right tools, skills and systems to develop and manage complex projects, as well as multi-level governance systems that support public investment. This is particularly important given that public investment through EU funds is a shared responsibility among national, regional, local, and the European levels of government, requiring effective multi-level governance mechanisms as well as skilled public servants to manage and administer investment cycles at all levels of government.

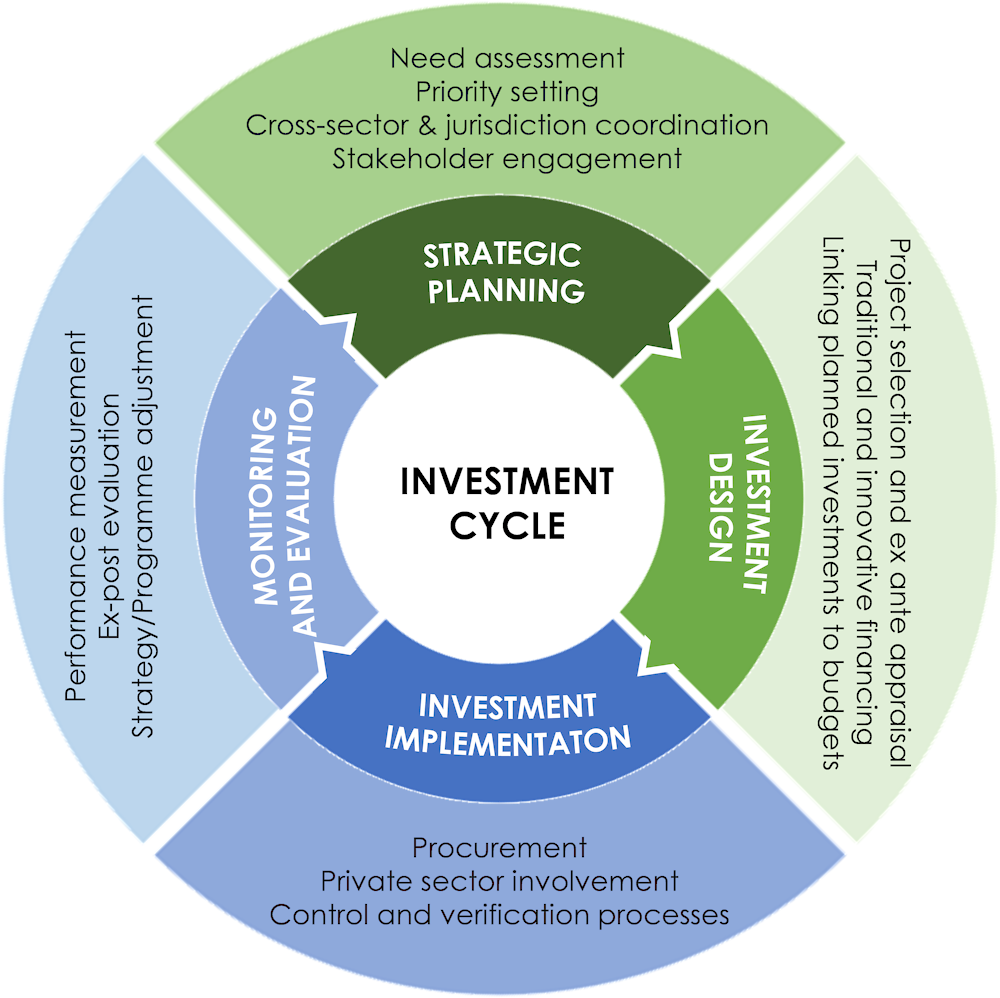

Box 1.2. Defining capacity for effective investment

The issue of investment capacity is fundamental for all actors involved in ESIF investment – including governments, national coordinating bodies, MAs, IBs, beneficiaries and other relevant stakeholders – in order to design OPs, prioritise investment needs, select projects and monitor, evaluate and recalibrate performance. With respect to public investment, capacity refers to the institutional arrangements, technical capabilities, human, economic and financial resources, and policy practices that affect public investment. Strong investment capacities are an enabler to achieve important goals at different stages of the investment cycle (Figure 1.7).

Figure 1.7. The investment cycle

To support the effective management of public investment throughout the investment cycle, there are a number of abilities or actions that are fundamental to cultivate and support in each phase. Among these are:

Strategic Planning

Engage in strategic planning that is tailored, results-oriented, realistic, forward-looking and coherent with national and/or other higher-level objectives (e.g. Partnership Agreements). ✦

Ensure the quality and availability of technical and managerial expertise necessary for planning and executing public investment, throughout the investment cycle. ✦

Coordinate across sectors and/or jurisdictions to achieve an integrated (and place-based) approach and to ensure complementarities.

Involve stakeholders in planning to enhance the quality and support for investment choices, while also preventing risk of capture by specific interest groups.

Design mechanisms to monitor and manage risks to integrity and accountability throughout the investment cycle.

Investment design

Conduct rigorous ex ante appraisal. ✦

Link strategic plans to multi-annual budgets

Tap into traditional and innovative sources of financing. ✦

Investment implementation

Design and maintain transparent, competitive, public procurement processes with appropriate internal control systems. ✦

Mobilise private sector financing without compromising long term sustainability of public investment projects.

Engage in “better regulation” at all levels of government, and ensure that regulations are coherent among them.

Monitoring and Evaluation

Design and use monitoring indicators systems with realistic, performance-promoting targets. ✦

Conduct regular and rigorous ex post evaluation.

Use monitoring and evaluation information to enhance decision making and identify necessary adjustments.

Note: ✦ = a critical action for all actors involved in public investment processes.

The term administrative capacity has no standard definition, despite extensive use. In the context of the EU, and particularly Cohesion Policy implementation, it can be conceptualised as the combination of capabilities used by countries to achieve effective spending of EU funds, namely human resources (numbers, quality in terms of skills and expertise, human resource management systems that structure incentives, etc.), organisational structure (institutional design, coordination and accountability of bodies in the management and implementation processes), systems and tools (including adaptability to procedures), and governance (legal and procedural arrangements) (Surubaru, 2017[44]; European Committee of the Regions, 2018[45]; EC-DG REGIO, 2018[46]).

Building on this, administrative capacity building (ACB) can be defined as developing skills, experience, technical, management and strategic capacity within an organisation. It is often achieved through the provision of technical assistance, short- and long-term training, as well as specialist inputs. The process of administrative capacity building may involve human, material and financial resources development, but also strategic planning (OECD, 2002[47]) .

Administrative capacity building is also a “learning-by-doing” process in which national and subnational governments can acquire necessary capacities on a daily basis through practice. To build the capacities needed, the “learning-by-doing” process should go hand-in-hand with differentiated and targeted capacity building activities and technical assistances. The administrative capacity of national, regional and local authorities to effectively manage such complex investments and financing mechanisms and ensure quality institutions and governance are therefore crucial for the successful delivery of EU funds and ultimately better cohesion across the EU.

Investing in ACB helps improve ESIF management, which eventually leads to optimising the absorption rate (spending available funds fully); to minimising irregularities (spending funds correctly); and most importantly, to maximising impact and sustainability (spending them strategically) (European Commission, 2018[48]). In other words, ACB increases the capacities of organisations involved in the management of European funds to effectively perform their duties and ensure more performant ESIF investment.

Building administrative capacity through Technical Assistance for Managing Authorities

Administrative capacity is recognised as one of the key factors contributing to the success of Cohesion Policy (Boijmans, 2013[49]; Rodriguez-Pose and Garcilazo, 2013[50]). Given its importance for effective and sustainable ESIF investment, the EU is committed to supporting Member States and their MAs build such capacity. Managing Authorities are quite diverse, representing both the central and the subnational government levels, including states (in federal countries) and regions. They are confronted with similar challenges related to skills, competencies or organisational capabilities, the ways they communicate with beneficiaries and/or the public, coordinate and interact with internal and external stakeholders, and arrange impact assessments, evaluation, monitoring and audits. How these challenges manifest, will differ according to the institutional and political context of a country or a region, as well as their length of Cohesion Policy experience etc. Gaps in their administrative capacities are widely recognised by Member States and EU bodies, hence the availability of support for public administration reform and technical assistance through Cohesion Policy.

The European Commission has made administrative capacity building central to Cohesion Policy and the Europe 2020 strategy. Since the beginning of the current programme period, the EC, and specifically DG REGIO, offers EU Member State administrations diverse mechanisms to strengthen their institutional capacity and professionalise those managing ESIF. These include investments in efficient public administration made under Thematic Objective 11, Technical Assistance to authorities that manage ESIF (Box 1.3), as well as specific programmes, such as TAIEX-REGIO PEER 2 PEER; Integrity Pacts; S3 Platform, Urban Development Network, guidance for practitioners on how to avoid public procurement errors; training seminars; and the EU Competency Framework for managing and implementing the ERDF/CF together with its self-assessment tool, which identify and address competency gaps.

Box 1.3. Thematic Objective 11 and Technical Assistance for ESIF implementation

EU Cohesion Policy funding invests in institutional capacity building and reforms under Thematic Objective (TO) 11: “Enhancing institutional capacity of public authorities and stakeholders and efficient public administration.” In addition to the investments under TO11, Technical Assistance (TA) is also available to authorities that administer and use ESIF. The purpose of this TA is to help them perform the tasks assigned to them under the various European Structural and Investment Fund Regulations. It is important to note that there are overlaps in the types of activities that can be funded under each instrument.

Thematic Objective 11

Thematic Objective (TO) 11 has a slightly different focus depending on which EU fund is involved. The European Social Fund (ESF) has a wide scope, supporting the efficiency of the public administration as a whole, whereas the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and the Cohesion Fund (CF) focus on administration and services related to the implementation of the ERDF and CF respectively, or support of actions under the ESF.

Investments can focus on three broad dimensions of building institutional capacity:

1. structures and processes;

2. human resources;

3. service delivery (e.g. the provision of equipment and infrastructure, and reforming human resources processes and strategies to support the modernisation of public services in areas such as employment, education, health, social policies and customs).

In addition, as effective Cohesion Policy also depends on the abilities of beneficiaries in areas such as project development and monitoring, procurement, and financial management, beneficiaries are also eligible to receive similar capacity-building attention. Furthermore, funding can be used for capacity building for stakeholders delivering employment, education, health and social policies, and sectoral and territorial pacts to mobilise for reform at national, regional and local levels. This includes enhancing the capacity of stakeholders, such as social partners and non-governmental organisations, to help them deliver more effectively.

Technical assistance

Technical Assistance (TA) can take the form of separate TA OPs and/or of a Priority Axis in other OPs. Money for TA is made available through the ERDF, ESF and CF. EU rules place a limit on the proportion of funding from the OPs that can be allocated to TA. If TA is initiated by or on behalf of the European Commission, that ceiling is 0.35% of the annual provision for each fund. If technical assistance comes from the Member States, the ceiling is 4%.

The scope of TA at the initiative of the Member States is defined in Article 59 (1) of the Common Provisions Regulation, and more clearly specified in the Draft Guidance Fiche for 2014-2020 programming (European Commission, 2014[50]), stating that the scope is limited to:

Actions linked to functions necessary for the implementation of the ESIF. In relation to the ERDF, CF and ESF, these functions are fulfilled by the MA, Certifying Authority, Audit Authority, IBs, and the Monitoring Committee. Although also other bodies can have responsibilities of these functions, they are not eligible for TA;

Actions for the reduction of the administrative burden on beneficiaries linked to ESIF (including electronic data exchange systems);

Capacity building of Member State authorities and beneficiaries solely linked to the administration and use of ESIF;

Capacity building of relevant partners involved in the implementation of partnership and actions to support the exchange of good practices between such partners.

Source: (EC-DG REGIO, 2019[51]), also see Articles 58 & 59 of the Common Provisions Regulation governing ESIF (European Commission, 2018[52])

Designing Roadmaps for administrative capacity building with the OECD diagnostic framework

There are a number of proposed changes to the Cohesion Policy framework6 for the 2021-2027 programming period, including simplification and fewer policy objectives (Box 1.4). Continuing to build administrative capacity, for example through simpler and stronger governance structures and mechanisms will be critical. One large change will be in how support to capacity building is funded. While Technical Assistance (TA) will still exist, there will no longer be a separate thematic objective (currently TO 11) dedicated to institutional capacity building. The Commission proposes two types of TA under Cohesion Policy: a) traditional TA, for which payments from the European Commission to the Member States is made on the basis of a flat rate; and b) additional TA to reinforce capacity of Member State authorities (MAs, Certifying Authorities, Audit Authorities, etc.), IBs, beneficiaries and other relevant partners for the effective administration and use of the Funds. For the latter type of TA payments to Member States will be based on results achieved or conditions fulfilled, and actions, deliverables and corresponding payments can be agreed in roadmaps for administrative capacity building [Recital 25 of the Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council COM (2018) on the common provisions COM(2018) 375 final] (European Commission, 2018[52]). However, the Roadmaps can cover all capacity building actions under Cohesion Policy, including capacity building directly linked to investments which can be supported under the budgets for five policy objectives [Article 2.3(a) of the ERDF and CF Regulation COM(2018) 372 final] (European Commission, 2018[52]).

Box 1.4. ESIF 2021-2027: Simplified rules and more flexibility

The European Commission (EC) is now developing the framework for the 2021-2027 programming period in which it is proposing a smarter and simpler procedure for the use of ESIF and the enforcement of its regulations. This includes several initiatives to reduce administrative costs, introduce greater flexibility and strengthen an integrated approach to investment.

Simplification

The EC proposes 80 simplification measures for the upcoming programming period, covering the legal framework, the application of conditionalities, OP programming and implementation, control and audit, and the use of financial instruments. For example:

A Common Provisions Regulation (CPR) will set out a single regulation framework for seven shared management funds, namely ERDF, CF, ESF+, EMFF, the Asylum and Migration Fund (AMF), the Border Management and VISA Instrument, and the Internal Security Fund. In addition, five Policy Objectives (POs) are proposed, down from the 11 TOs in the 2014-2020 period, and with simpler wording.

Reducing the number of conditionalities from 40 to 20 and to be called ‘enabling conditions’.

Allowing the designation of the 2014-2020 MCS to be carried into the next period.

Extending the use of Simplified Cost Options, meaning that instead of reimbursing actual expenditures based on invoices, more payments will be made based on a flat rate, unit costs or lump sums.

Strengthening single audit arrangements.

Flexibility

The EC also aims to create a more proportionate system for the 2021-27 period by introducing greater flexibility in regulations and OP management processes. For example:

Management verifications and checks will be carried out using a risk-based approach, differentiating projects and programmes.

Simpler audit requirements will be applied to OPs with a good track record and MCS that are properly functioning.

Reimbursing Technical Assistance can be done via a flat rate (between 2.5% and 6% of each interim payment, depending on funds and based on progress in programme implementation). This may be complemented with targeted administrative capacity building measures using reimbursement methods that are not linked to costs. Actions and deliverables as well as European Union corresponding payments can be agreed upon in a roadmap.

For more detailed information, please see

Simplification Handbook: 80 simplification measures in cohesion policy 2021-2027 https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docgener/factsheet/new_cp/simplification_handbook_en.pdf

Full text of the European Commission’s Proposal https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/budget-may2018-common-provisions_en.pdf

To support EU Member States and their MAs adapt to this shift, DG REGIO’s Unit E.1 Administrative Capacity Building and European Solidarity Fund launched a pilot project, with the support of the OECD, to give an initial shape and test an approach to designing Administrative Capacity Building Roadmaps that could eventually be used for more strategic use of technical assistance in the 2021-2027 ESIF programming period.

As part of the project, the OECD gathered information and documentation from five pilot MAs7 through a questionnaire and an OECD study mission to each MA. During the mission, in addition to interviews with a wide range of MA and OP stakeholders, a full day, interactive workshop with stakeholders was held to jointly identify the challenges confronting the MA in the implementation of their OP, to highlight priorities for action, and to begin articulating potential solutions. An analytical framework designed by the OECD supported the workshop structure and discussions, and provided the basis for the Roadmaps that emanated from these discussions. While each Roadmap was tailored to the needs of the individual MA, all Roadmaps had the same structure (Table 1.1). Further details on the project background and methodology can be found in Annex A.

Table 1.1. Sample Roadmap for Administrative Capacity Building in Managing Authorities

|

Roadmap for the MA for the OP |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Challenge area 1: People and organisational management |

||||||

|

Goal/Sub-goal |

Action |

Owner (responsible for action) |

Implementing stakeholders |

Timing / Date |

Deliverable(s) (optional) |

Milestones (optional) |

|

Goal (i) Sub-goals (optional) |

Action (i) |

e.g. MA, national authority |

e.g. MAs, IBs, national authority |

e.g. date by when action complete |

e.g. meetings, reports |

|

|

Action (ii) |

||||||

|

Goal (ii) |

Action (i) |

|||||

|

Action (ii) |

||||||

|

Challenges area 2: Strategic planning and coordination |

||||||

|

Goal (i) Sub-goals (optional) |

Action (i) |

e.g. MA, national authority |

e.g. MAs, IBs, national authority |

e.g. date by when action complete |

e.g. meetings, reports |

|

|

Action (ii) |

||||||

|

Goal (ii) |

Action (i) |

|||||

|

Action (ii) |

||||||

|

Challenge area 3: Framework conditions |

||||||

|

Goal (i) Sub-goals (optional) |

Action (i) |

e.g. MA, national authority |

e.g. MAs, IBs, national authority |

e.g. date by when action complete |

e.g. meetings, reports |

|

|

Action (ii) |

||||||

|

Goal (ii) |

Action (i) |

|||||

|

Action (ii) |

||||||

The OECD analytical framework for administrative capacity building

It is important to stress that each MA drove the development process of their Roadmap, identifying actions, timelines and stakeholders, and that the goals, ideas and solutions captured in the Roadmaps were elaborated with the active participation of OP stakeholders in each country. The OECD provided the framework for thinking through the issues, helped articulate the actions, and facilitated the discussions.

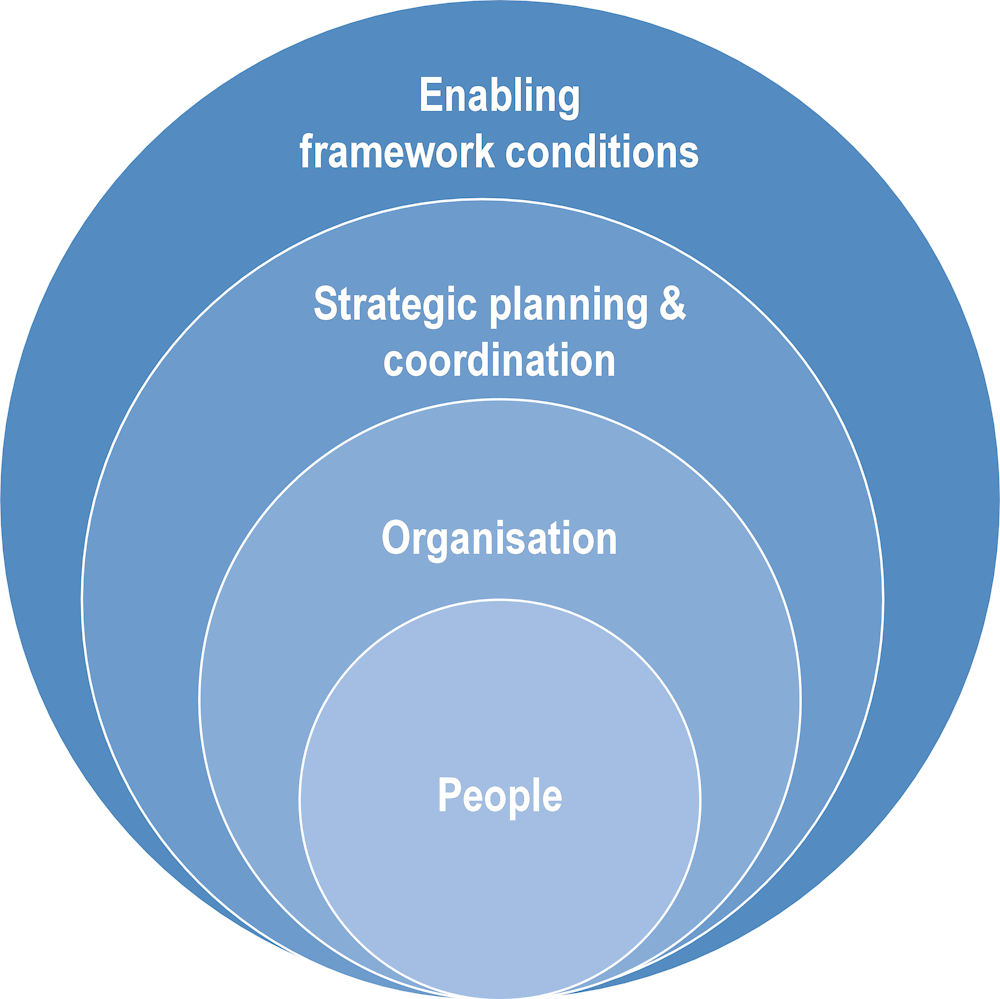

To assist MAs think through and design their administrative capacity building Roadmaps, the OECD developed a concentric framework that captures the various dimensions that MAs must work with and/or consider as they move forward in the design and implementation of their ESIF OPs (Figure 1.8). Each dimension moves upward through the organisational and governance structures supporting OP implementation and ESIF investment.

Figure 1.8. OECD Analytical framework for administrative capacity building

People

People are the backbone of any organisation. Thus the OECD has recently worked closely with member countries to develop the 2019 OECD Recommendation on Public Service Leadership and Capability (PSLC) which sets out 14 principles for a fit-for-purpose public service workforce. The People dimension of this framework follows the second pillar of the PSLC which promotes civil service capacity to achieve operational and strategic objectives, in this case by identifying the mix of skills and competences needed in a high performing MA. It looks at how skills gaps are identified and addressed, both by attracting and recruiting the skills and expertise needed from the labour market, and by using learning and development tools, including training, to build workforce capacity. It also looks at how the workforce can be motivated to put its skills to best use. This suggests a review of incentives and performance management systems to set goals and measure their progress towards them, as well as the role of leaders and managers to motivate their employees.

Organisation

Women and men with the right skills also require an organisational structure and support that enable and empower them to put their skills to work. Recent empirical research shows that low organisational complexity and high personnel stability are important indicators of organisational capability (Andrews, Beynon and McDermott, 2015[57]). Employee actions are shaped to a large degree by the system in which they operate. This is the second level of analysis. This dimension looks at the systems, tools, business processes and culture that influence how staff of the MAs work. It looks at whether these tools and systems are aligned to the MA’s strategic objectives, and supported by agile governance structures to facilitate effective data-informed decision-making. HR systems bring in the right people and support them to contribute, and effective organisational development ensures people are able to deliver. ICT and information management systems are also essential, to facilitate communication and ensure that leadership is equipped to make data-informed decisions.

Strategic planning and co-ordination

The strategic planning dimension examines various aspects throughout the whole investment cycle, from strategy development, priority setting, coordination, project planning and selection, to project implementation, stakeholder engagement, and monitoring and evaluation. In a survey conducted by the OECD and Committee of the Regions (CoR) in 2015, poor strategic planning was identified one of the most important challenges for public investment, beyond the financing challenge (OECD-CoR, 2015[58]). The OECD Recommendation on Effective Public Investment across Levels of Government (OECD, 2014[29]) emphasises the pre-conditions for good strategic planning, in particular for the involvement of external stakeholders and private actors. The Principles also stress the importance of coordinating across levels of government, and across jurisdictions, as well as cross-sectoral coordination for effective investment strategies. The Recommendation, with 12 Principles, is complemented with an Implementation Toolkit that includes a set of indicators to help countries, regions, cities and other local authorities self-assess their strategic planning capacities, the bottlenecks they face, and the priorities for action (OECD, 2019[30]).

Framework conditions

Appropriate framework conditions are crucial for creating an enabling environment for all level of government to invest effectively. These conditions include a fiscal framework adapted to the investment objectives pursued, sound and transparent financial management, transparency, and the strategic use of public procurement, as well as consistent and clear regulatory and legislative systems.

The capacity of MAs to operate effectively is subject to many factors beyond their control: priority setting by the government, regulations such as EU rules, procedures, and conditionalities, budgetary allocations and fiscal rules to manage public investment, etc. Decentralisation frameworks can also affect the way regional authorities manage ESIF. Framework conditions determine the way the principle of partnerships work with the private sector (business community), non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and citizens. It is thus essential to take a holistic and comprehensive approach to understand clearly the bottlenecks hindering the effective and efficient functioning of the MA, and ways to address them. When doing so, the possibility of introducing some flexibility in the system, without changing the overall framework conditions, increases.

References

[41] Allain-Dupré, D., C. Hulbert and M. Vincent (2017), “Subnational Infrastructure Investment in OECD Countries: Trends and Key Governance Levers”, OECD Regional Development Working Papers, No. 2017/05, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/e9077df7-en.

[57] Andrews, R., M. Beynon and A. McDermott (2015), Organisational Capability in the Public Sector: A Configurational Approach, http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muv005.

[38] Bachtler, J. and I. McMaster (2008), “EU Cohesion Policy and the Role of the Regions: Investigating the Influence of Structural Funds in the New Member States”, Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, Vol. 26/2, pp. 398-427, http://dx.doi.org/doi.org/10.1068/c0662.

[49] Boijmans, P. (2013), The secrets of a successful administration for Cohesion Policy, RSA European Conference, DG Regional and Urban Policy - Unit E1 "Competence Centre for Administrative Capacity-Building and the Solidarity Fund", https://3ftfah3bhjub3knerv1hneul-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/The_secrets_of_a_successful_administration_for_Cohesion_Policy_-_Pascal_Boijmans.pdf.

[16] Brookings Insitution, New Climate Economy, and Grantham Research Insitute (2015), Driving Sustainable Development through Better Infrastructure: Key Elements of A Transformation Program, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/07-sustainable-development-infrastructure-v2.pdf.

[23] Byrne, D. (2014), Management and control systems , presentation organised by EIPA-Ecorys-PwC, European Commission Publishing, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2018/601972/IPOL_STU(2018)601972_EN.pdf.

[34] Charron, N., L. Dijkstra and V. Lapuente (2014), “Regional Governance Matters: Quality of Government within European Union Member States”, Regional Studies, Vol. 48/1, pp. 68-90, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2013.770141.

[28] Crescenzi, R. and M. Giua (2016), “The EU Cohesion Policy in context: Does a bottom-up approach work in all regions?”, Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, Vol. 48/1, pp. 2340-2357, http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0308518X16658291.

[43] Dabla-Norris, E. et al. (2010), Investing in Public Investment: An Index of Public Investment Efficiency, IMF Working Paper WP/11/37, International Monetary Fund, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2011/wp1137.pdf.

[55] De Falco, F. (2019), Cohesion Policy and ESI Funds in 2021-2027: a policy debate, article on EULOGOS-ATHENA, https://www.eu-logos.org/2019/05/22/cohesion-policy-and-esi-funds-in-2021-2027-a-policy-debate/.

[31] De la Fuente, A. (2002), “On the sources ofconvergence: A close look at the Spanish regions”, European Economic Review, Vol. 46/3, pp. 569-599.

[51] EC-DG REGIO (2019), Directorate-General Regional and Urban Policy, https://ec.europa.eu/info/departments/regional-and-urban-policy_en.

[46] EC-DG REGIO (2018), Call For Expression Of Interest: For Managing Authorities To Participate In A Pilot Action On Frontloading Administrative Capacity Building To Prepare For The Post-2020 Programming Period, European Commission Directorate-General Regional And Urban Policy, https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/tender/pdf/expression/administrative_capacity_building.pdf.

[32] Ederveen, S., H. de Groot and R. Nahuis (2006), “Fertile Soil for Structural Funds?A Panel Data Analysis of the Conditional Effectiveness of European Cohesion Policy”, Kyklos, International Review for Social Sciences, Vol. 59/1, pp. 17-42, http://10.1111/j.1467-6435.2006.00318.x.

[33] Ederveen, S. et al. (2003), Funds and Games: The Economics of European Cohesion Policy, ENEPRI Occasional Paper No. 3, http://aei.pitt.edu/1965/.

[9] EIB (2016), Investment and Investment Finance in Europe: Financing productivity growth - Key Findings, European Investment Bank, https://www.eib.org/attachments/efs/investment_and_investment_finance_in_europe_key_findings_2016_en.pdf.

[22] European Commission (2019), Data: % of cohesion policy funding in public investment per Member State, https://cohesiondata.ec.europa.eu/Other/-of-cohesion-policy-funding-in-public-investment-p/7bw6-2dw3 (accessed on 6 August 2019).

[2] European Commission (2019), ESIF 2007-2013 EU Payments (daily update), https://cohesiondata.ec.europa.eu/2007-2013/ESIF-2007-2013-EU-Payments-daily-update-/aqhg-azqx.

[1] European Commission (2019), ESIF 2014-2020 Finance Implementation Details, https://cohesiondata.ec.europa.eu/2014-2020/ESIF-2014-2020-Finance-Implementation-Details/99js-gm52.

[54] European Commission (2019), New Cohesion Policy, https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/2021_2027/.

[14] European Commission (2018), Boosting investment in social infrastructure in Europe: Report of the High-Level Task Force on Investing in Social Infrastructure in Europe, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs (European Commission), http://dx.doi.org/10.2765/794497.

[56] European Commission (2018), EU Budget for the future: Cohesion Policy 2021-2027, presentation, http://www.dgfc.sepg.hacienda.gob.es/sitios/dgfc/es-ES/ipr/fcp2020/fcp2020Demyo/Documents/CP_2021-27_Madrid_21.6.18.pdf.

[52] European Commission (2018), Proposal for a REGULATION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL laying down common provisions on the European Regional Development Fund, the European Social Fund Plus, the Cohesion Fund, and the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund and financial r, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2018%3A375%3AFIN.

[48] European Commission (2018), Quality of Public Administration - A Toolbox for Practitioners, https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/quality-public-administration-toolbox-practitioners.

[3] European Commission (2018), Seventh report on economic, social and territorial cohesion, https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docoffic/official/reports/cohesion7/7cr.pdf.

[37] European Commission (2017), Final conclusions and recommendations of the High Level Group on Simplification for post 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/information/publications/reports/2017/esif-simplification-hlg-proposal-for-policymakers-for-post-2020.

[59] European Commission (n.d.), European Structural and Investment Funds, https://ec.europa.eu/info/funding-tenders/funding-opportunities/funding-programmes/overview-funding-programmes/european-structural-and-investment-funds_en (accessed on 31 July 2019).

[21] European Commission (n.d.), European Structural and Investment Funds - Explore Project Stories, https://cohesiondata.ec.europa.eu/projects.

[17] European Commission (n.d.), Glossary - Thematic objectives, https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/policy/what/glossary/t/thematic-objectives (accessed on 31 July 2019).

[45] European Committee of the Regions (2018), Administrative capacity of local and regional authorities: Opportunities and challenges for structural reforms and a more effective European economic governance, https://cor.europa.eu/en/engage/studies/Documents/Administrative-capacity/AdminCapacity.pdf.

[4] European Court of Auditors (2019), Rapid case review: Allocation of Cohesion Policy funding to Member States for 2021-2027, European Union, https://www.eca.europa.eu/lists/ecadocuments/rcr_cohesion/rcr_cohesion_en.pdf.

[24] European Court of Auditors (2013), Taking Stock Of ‘Single Audit’ And The Commission’S Reliance On The Work Of National Audit Authorities In Cohesion, Special Report No 16, European Court of Auditors, https://publications.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/eff3ae5c-040b-4b44-a66e-8f457e926a93/language-en.

[10] European Investment Bank (2019), EIB Investment Report 2018/2019: retooling Europe’s economy - Key findings, The European Investment Bank, https://www.eib.org/attachments/efs/economic_investment_report_2018_key_findings_en.pdf.

[53] European Training Centre in Paris (2018), ESIF Common Provisions Regulation: what’s new for 2020?, http://etcp.fr/esif-common-provisions-regulation-whats-new-2020/ (accessed on 26 August 2019).

[36] European Union (2013), “Regulation (EU) No 1303.2013 of the European Parliament of of the Council”, Official Journal of the European Union, p. L 347/320, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32013R1303&from=en.

[12] Eurostat (2019), GDP and main components (output, expenditure and income) (nama_10_gdp), https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=nama_10_gdp&lang=en (accessed on 2019).

[11] Eurostat (2019), Government revenue, expenditure and main aggregates, https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=gov_10a_main&lang=en (accessed on October 2019).

[25] Ferry, M. and L. Polverari (2018), Research for REGI Committee – Control and simplification of procedures, European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2018/601972/IPOL_STU(2018)601972_EN.pdf.

[18] Fournier, J. (2016), “The Positive Effect of Public Investment on Potential Growth”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1347, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/15e400d4-en.

[5] IMF (2018), World Economic Outlook: Cyclical Upswing, Structural Change, International Monetary Fund, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2018/03/20/world-economic-outlook-april-2018.

[27] IMF (2015), Making Public Investment More Efficient, The OECD Senior Budget Officials Meeting, International Monetary Fund, presented by Marco Cangiano, https://www.slideshare.net/OECD-GOV/making-public-investment-more-efficient-marco-cangiano-imf.

[19] IMF (2015), The Macroeconomic Effects of Public Investment : Evidence from Advanced Economies, International Monetary Fund, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2016/12/31/The-Macroeconomic-Effects-of-Public-Investment-Evidence-from-Advanced-Economies-42892.

[15] McKinsey Global Institute (2016), Bridging Global Infrastructure Gaps, Mckinsey & Company, https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Industries/Capital%20Projects%20and%20Infrastructure/Our%20Insights/Bridging%20global%20infrastructure%20gaps/Bridging-Global-Infrastructure-Gaps-Full-report-June-2016.ashx.

[20] McKinsey Global Institute (2013), Infrastructure productivity: How to save $1 trillion a year, Mckinsey & Company, https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Industries/Capital%20Projects%20and%20Infrastructure/Our%20Insights/Infrastructure%20productivity/MGI%20Infrastructure_Full%20report_Jan%202013.ashx.

[39] McMaster, I. and V. Novotny (2005), Implementation and management of EU cohesion funds, EPRC Benchmarking Regional Policy in Europe Conference, https://pureportal.strath.ac.uk/en/publications/implementation-and-management-of-eu-cohesion-funds.

[35] Milio, S. (2007), “Can Administrative Capacity Explain Differences in Regional Performances? Evidence from Structural Funds Implementation in Southern Italy”, Regional Studies, Vol. 41/4, pp. 429-442, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00343400601120213.

[40] Mizell, L. and D. Allain-Dupré (2013), “Creating Conditions for Effective Public Investment: Sub-national Capacities in a Multi-level Governance Context”, OECD Regional Development Working Papers, No. 2013/4, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5k49j2cjv5mq-en.

[30] OECD (2019), Effective Public Investment across Levels of Government: Implementing the OECD Principles, OECD Publishing, https://www.oecd.org/effective-public-investment-toolkit/OECD_Principles_For_Action_2019_FINAL.pdf.

[6] OECD (2018), OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2018 Issue 1, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_outlook-v2018-1-en.

[26] OECD (2018), Rethinking Regional Development Policy-making, OECD Multi-level Governance Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264293014-en.

[13] OECD (2017), Investing in Climate, Investing in Growth, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264273528-en.

[29] OECD (2014), Recommendation of the Council on Effective Public Investment Across Levels of Government, OECD Publishing, http://www.oecd.org/regional/regional-policy/Principles-Public-Investment.pdf.

[8] OECD (2013), Investing Together: Working Effectively across Levels of Government, OECD Multi-level Governance Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264197022-en.

[7] OECD (2011), OECD Regional Outlook 2011: Building Resilient Regions for Stronger Economies, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264120983-en.

[47] OECD (2002), Glossary of Statistical Terms: ’Capacity Building’, https://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=5103.

[58] OECD-CoR (2015), Results of the OECD-CoR Consultation of Sub-national Governments—Infrastructure planning and investment across levels of government: current challenges and possible solutions, Commitee of the Regions of European Union and OECD, https://portal.cor.europa.eu/europe2020/pub/Documents/oecd-cor-jointreport.pdf.

[42] Rajaram, A. et al. (2010), A Diagnostic Framework for Assessing Public Investment Management, Policy Research Working Paper 5397, The World Bank, Africa Region, Public Sector Reform and Capacity Building Unit & Poverty Reduction and Economic Management Network, Public Sector Unit, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/396891468330305148/pdf/WPS5397.pdf.

[50] Rodriguez-Pose, A. and E. Garcilazo (2013), “Quality of Government and the Returns of Investment: Examining the Impact of Cohesion Expenditure in European Regions”, OECD Regional Development Working Papers, No. 2013/12, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5k43n1zv02g0-en.

[44] Surubaru, N. (2017), “Administrative capacity or quality of political governance? EU Cohesion Policy in the new Europe, 2007-2013”, Regional Studies, Vol. 51/6, pp. 844-856, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1246798.

Notes

← 1. The data for both 2007-2013 and 2014-2020 period exclude the funding for Instrument for Pre-accession Assistance (IPA).

← 2. EU 12 countries are Bulgaria, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia. For the 2014-2020 period, Croatia is also included in the estimate.

← 3. Social infrastructure refers infrastructure supporting social services including, for example in education services, social care, community support, emergency services, arts and cultural services in a community.

← 4. The Thematic Objectives are: 1. Strengthening research, technological development and innovation; 2. Enhancing access to and use and quality of information and communication technologies (ICT); 3. Enhancing the competitiveness of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs); 4. Supporting the shift towards a low-carbon economy in all sectors; 5. Promoting climate change adaptation, risk prevention and management; 6. Preserving and protecting the environment and promoting resource efficiency; 7. Promoting sustainable transport and removing bottlenecks in key network infrastructures; 8. Promoting sustainable and quality employment and supporting labour mobility; 9. Promoting social inclusion, combating poverty and any discrimination; 10. Investing in education, training and vocational training for skills and lifelong learning; 11. Enhancing institutional capacity of public authorities and stakeholders and efficient public administration (European Commission, n.d.[59])

← 5. Such mechanisms include monitoring and evaluation systems, grant conditionalities, financial instruments for regional development policies, and contracts or other agreements to support effective partnerships among different levels of governments.

← 6. These are still under negotiation with MS and EP at the time of drafting this report.

← 7. The five Managing Authorities are: the Managing Authority for the Regions in Growth Operational Programme in Bulgaria; the Managing Authority of the Competitiveness and Cohesion Operational Programme in Croatia; the Managing Authority of the Transport Infrastructure, Environment and Sustainable Development Operational Programme in Greece; the Managing Authority of the Regional Operational Programme for the Lubelskie Voivodeship in Poland; and the Managing Authority for the Regional Operational Programme for Extremadura in Spain.