This chapter discusses the impact of framework conditions on the administrative capacity of Managing Authorities, and offers possibilities for working within their constraints. Analysis shows that ensuring sound, consistent, and transparent legislation and regulation, including those related to procurement processes, can reduce administrative burden and increase investment stability, thereby contributing to investment management capacity.

Strengthening Governance of EU Funds under Cohesion Policy

Chapter 5. The impact of framework conditions on Managing Authorities

Abstract

Introduction

Framework conditions that affect public investment (i.e. higher-level parameters that support or constrain investment operation and processes) can include budgetary, regulatory and procurement legislation and practices. Ensuring that these conditions are sound, consistent, transparent, and adapted to the objectives pursued (OECD, 2019[1]) contributes to a Managing Authority’s (MA) investment management capacity. If poorly designed, unstable, or improperly explained or understood, framework conditions can negatively affect investment processes and results, causing unnecessary delays and increasing project costs. At the same time, framework conditions can be complex, and may not be consistent or stable over time, among levels of government or even within a single level of government.

An MA’s operational context is framed by legislation and regulations established at the European Union (EU) and national levels, as well as through the Management and Control System (MCS) (Chapter 1, Box 1) that sets the institutional framework as well as the common rules, procedures and monitoring mechanism that govern operations for all MAs in a country. EU-level regulations govern the allocation and use of European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF), including control, verification, monitoring and audit processes. These can change significantly over successive programming periods and are consistently perceived as complex by MAs and other Operational Programme (OP) stakeholders. MAs, Intermediate Bodies (IBs), beneficiaries and other OP stakeholders participating in this pilot action generally cited EU regulations as one of the leading impediments to more efficient and/or effective ESIF investment processes. In addition, EU Member States establish their own national regulations governing the management of EU funds in their territory. These regulations can vary according to country context, institutional parameters, and level of government. MCS, usually established by the bodies responsible for managing EU funds in an EU Member State, can differ according to national governance practices. Thus, while EU regulations are consistent across Member States, national-level frameworks and MCS vary from country to country, each characterised by different levels of stability and complexity, rendering ESIF implementation easier for some MAs than for others.

With the exception of public procurement frameworks, in general the greatest difficulties seem to be not in the existence of framework conditions themselves (there is general agreement that rules, regulations and standards can be valuable), but rather in their characteristics. Top among the challenges highlighted in this pilot project involved national legislative/regulatory practices for ESIF and associated administrative burden; a lack of clarity and/or a lack of consistency in interpreting rules or practices surrounding controls, verifications and audits; and difficulties working within public procurement parameters. Combined, these can generate excessive administrative burden, instability and uncertainty in the investment process, which in turn affects absorption capacity. This can lead to a risk that resources are not deployed in the most effective and efficient manner. For example, MAs may tend to focus on complying with regulations and take a risk-adverse approach when designing calls, or selecting and assessing projects. In addition, there is the potential to lose sight of overall objectives, and cause unnecessary delays and increased project costs.

It is important to recall that many, if not all, framework conditions take time to change and are outside of an MA’s direct control. In light of this, the European Commission has acknowledged that framework conditions pose challenges and has made moves towards greater simplification for the post-2020 programming period. Thus, the discussion below intends simply to highlight the main issues and their implications. It should be noted, however, that some MAs do take matters to hand and play an active role in proposing amendments of relevant legal and regulatory frameworks, putting pressure where it is needed when red tape appears to be causing significant problems in OP implementation. Many MAs are also quick to respond and offer guidance to beneficiaries seeking clarifications on legal frameworks, as well as finding ways to communicate how other beneficiaries addressed similar obstacles. Overall, with respect to framework conditions, MAs and other parties must work together to set realistic and effective parameters and proactively manage difficulties as quickly and efficiently as possible. It is also important to consider active consultation with MAs when designing the framework conditions that structure their work.

Regulatory changes create instability and generate administrative burden

Stakeholders across different MAs tend to consider that the rules and regulations associated with OP implementation – be they stemming from the EU, from the national government or part of the MCS – can be unclear, unstable, excessive, and generate unnecessary administrative burden for OP implementation. European-level regulations and requirements, which are complicated, are often incorporated into national legislation, adding another layer of complexity, reducing the room for manoeuvre and potentially increasing red tape. Simplifying procedures is crucial to promote effective public investment, in particular where capacities are low, a point that the European Commission is reinforcing through greater simplification in the next programming period. An excessive amount of legislation and guidance or the proliferation of multiple conditions coupled with weak capacities can lead to inefficient investment. Moreover, administrative burden combined with unequal capacities within countries, risk deepening pre-existing inequalities (OECD, 2018[2]). Pilot MAs report difficulties arising from unclear, complex or frequently changing legislation, as well as a “one-size-fits-all” approach to programming requirements.

Unclear, complex and changing regulations at the EU and national levels

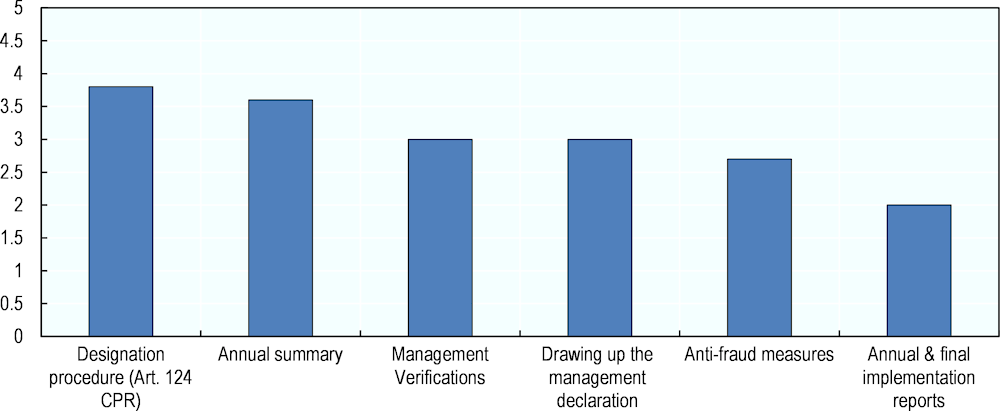

A lack of clarity and a high degree of complexity in the rules governing ESIF use, be they EU or national-level rules, is a common theme brought up among OP stakeholders in each participating country. MAs in some countries note that in order to counter any uncertainty, different national control bodies respond by introducing new or additional control activities for ESIF, often stricter than those established in EU or national regulations. This can generate more administrative burden for the MAs, and higher transaction costs for IB and beneficiaries. One of the causes of complexity identified by MAs and other OP-implementing authorities is the untimely and fragmented provision of EU guidance, which further leads to legal uncertainty and ambiguity (Ferry and Polverari, 2018[3]). For example, designation procedures (i.e. ensuring that the MA and CA have the necessary and appropriate MCS set up) are considered by some MAs the most complex tasks in ESIF management for this programming period (Figure 5.1). Initially in this period, the European Commission intended to simplify these procedures by allowing Member States to carry out the designation without direct Commission review. However, in practice, following the various guidance and checklists from the European Commission increased the workload of Member States. In addition, Member States tend to establish a ‘heavy’ procedure to guarantee compliance and limit the scope of retroactive audit measures. The implication is that MAs, national authorities and the European Commission (EC) need to work together to find the right balance between systems that are sufficiently rigorous to detect irregularities and yet not too demanding or complex for administrations (Ferry and Polverari, 2018[3]).

Figure 5.1. Complexities facing MAs in the 2014-2020 programming period

Note: This is the survey result from 15 MA staff from seven different OPs. The designation procedure means ensuring that the MA and CA have the necessary and appropriate MCS set up. Management verifications include administrative verifications and on-the-spot checks. Annual summaries are those of accounts on the expenditure that was incurred as well as audit and control procedures.

Source: (Ferry and Polverari, 2018[3]).

Changes, sometimes frequent, to rules, regulations, and occasionally to key national strategic documents (e.g. national development strategies or sector strategies), are another trouble-spot for MAs. They require an on-going effort to interpret and understand potential impact, especially as such changes can lead to increasingly complex controls in order to avoid financial corrections. There are different reasons behind such changes. For example, they can arise if policies and rules are insufficiently robust and need to be adjusted; due to political influence or political change; or they can be the result of limited learning opportunities and/or insufficient evidence of regulatory or policy effectiveness, with decisions taken well before the conclusion of an expenditure cycle (Crescenzi and Giua, 2016[4]).

In some countries, eligibility rules can change midway through a project implementation cycle, and the new rules will apply to already-approved projects (rather than “grandfathering”1 the old rules). In Romania, for example, stakeholders strongly criticised frequent changes to national-level procedures and documentation by the government as a practice of “changing the rules during the game”. Such changes, although often necessary, had strong implications for the management of the funding and frequently triggered other unforeseen problems (Surubaru, 2017[5]). In other instances, line ministries may change their sectoral strategies every two or three years, or with the entry of a new government, which can then affect investment priorities at the OP level. In some MAs, OPs are linked to sectoral budget plans instead of overall sectoral strategies, or national budgets, or as part of an overall national ESIF budget line, when possible. This, too, can affect the stability of OP implementation, for instance if sector budgets are annual with limited year to year forecasting, or if circumstances generate limited budget predictability and severe adjustments, and/or if the MA depends on line ministries for co-financing. Single budget lines for ESIF can be helpful in this respect. In addition, greater recourse to financial instruments, in line with the European Commission recommendations, may also be valuable, though MA and beneficiary capacity to better capitalise on the opportunities afforded by using financial instruments may need to be built.

Frequent changes can also generate additional administrative work and insecurity (i.e. the possibility of financial corrections), which may lead to delays and can potentially discourage beneficiaries from responding to calls due to limited appeal of ESIF co-financed projects. It can also discourage innovation – not only in OP management processes but in the project proposals submitted by beneficiaries. By creating additional uncertainty and room for error in the project implementation process, such changes affect the consistency, stability and certainty that supports effective OP implementation and ESIF investment.

Such changes, especially those relating to regulation and legislation, also affect beneficiaries; and contributes to the ongoing need for effective and clear communication regarding changes and their practical implications, as well as support to properly implement them. This means that the MAs themselves must be clear about what the changes mean and how they should be applied.

The frequent changes to rules and regulations underscores the importance of accessible training, efficient information flows and active knowledge sharing throughout the OP management system. Regular opportunities for training at the technical and expert level – i.e. among those most involved in applying and explaining the rules – is fundamental. This can be in the form of hands-on workshops where staff learn how to better understand/interpret and apply new rules and regulations, for example. Such learning opportunities should be offered regularly and ideally tailored to different MA departments, as well regional MAs, IBs and beneficiaries. Establishing a working group or network of OP stakeholders (ideally across MAs) to act as a consultative body that can evaluate the impact of proposed legislative changes governing the use of ESIF could help identify potential difficulties in interpretation.

Adjusting Management and Control Systems to minimise one-size-fits-all approaches

Many MAs and OP stakeholders in this pilot project described approaches to the regulatory framework for ESIF as “inflexible”. While this may be inherent to the concept of regulations in general, it can depend on how they are designed, and when greater or lesser degrees of flexibility may be appropriate. What was evident in many cases is a “one-size-fits-all” approach to the rules governing administration and management procedures for project implementation. In more than one case, these are set without distinguishing between project type, sector or size (e.g. ERDF vs ESF, environment vs infrastructure, large and long term vs small and quick, high value versus modest value, etc.).

Generally speaking, OPs demand the same amount and type of documentation and licenses, number of approvals, and obligations for large, long-term and expensive projects as it does for small, short-term and less expensive ones, or regardless of the size of the beneficiary (e.g. a large company versus an SME, or a metropolitan area or Integrated Territorial Investment (ITI) versus a small, remote local authority). While this standardisation can facilitate higher-level management, control, and coordination, it leaves little room for an MA’s operational and implementation levels to tailor responses to specific challenges. It can lead to an ineffective use of already tight resources, as small projects demand the same amount of time and attention as larger ones that may have greater economic and development impact. In addition, there is the potential to lose sight of overall objectives, and cause unnecessary delays and increased project costs – particularly difficult for small projects with limited resources. This is a particularly significant issue for MAs whose OPs can involve multiple sectors or themes and projects of fundamentally different natures. One option is to introduce a greater degree of proportionality in checks and controls placed on projects based on the level of associated risk.

In the 2021-2027 programme period, more cross-sector and integrated programmes, measures and projects are expected. Introducing greater flexibility or room for MAs to adjust the procedures according to projects and beneficiaries could help further strengthen the integrated approach in OP implementation. This may require adjustments to the MCS. For countries that might consider this, to determine whether recalibration of the system is necessary and ensure that adjustments promote an improved system, consultation with MAs, IBs and beneficiaries is fundamental for determining perceptions and needs regarding greater flexibility.

Bringing MAs together with other key authorities to identify, discuss, adjust and solve matters inherent to the MCS could prove valuable. For example, in Greece, the National Coordination Authority is planning to introduce a Management and Control System Network to help address some of the rigidities in the MCS and in regulatory frameworks that affect all Greek MAs. This kind of network could serve as an information/experience sharing platform, as well as a consultative forum for MAs on critical matters such as system amendments, legal framework amendments and their impact, etc.

The impact of such a network could be boosted by the creation of an EU-wide network of MAs and coordinating bodies, sponsored by the EC, and open to national and regional level MAs. An EU-level network could serve as a powerful forum for information and knowledge exchange among MAs, discussion of common problems, identification of potential solutions, and sharing of good practices that could then be adapted and applied by MAs to their own country contexts. It could also be a useful source of information and a coordination mechanism for the EU as well, particularly when it is preparing strategy documents and programming initiatives.

High administrative burden can slow investment processes

Administrative burden and excessive red tape is a central challenge to effective investment (OECD, forthcoming[6]; OECD, 2018[2]), and one that MAs, IBs and beneficiaries consistently emphasised during this pilot project. ESIF investment rules and control activities that change often or which are excessively strict can result in higher day-to-day administrative burden for the MA and greater transaction costs for the IBs and beneficiaries, particularly if the rules adopted impose new, additional or more stringent requirements. For example, it is not unheard of for contracting authorities, and sometimes other control bodies, to require not only the necessary documentation per European directives, but also documentation requested in national legislative framework(s), and additional supporting documents to further verify the projects (including, on occasion, documentation that was relevant in past periods). This intensification of bureaucracy, while on the one hand potentially trying to minimise the possibility of financial corrections, on the other substantially increases the workload/management cost for everyone in the system – from the MA to beneficiaries – and particularly in sectors where there are many small projects. Ultimately, the result is lower OP implementation efficiency. If taken to an extreme, it also can mean less absorption due to a system that discourages investors (e.g. private sector) from applying to co-financed project opportunities given the associated transaction costs. MAs have some tools available to them to help streamline processes and alleviate the administrative burden in daily operations. Bulgaria, for example, introduced the electronic tendering and e-monitoring of public contracts systems in 2017. The central purchasing body in Italy, Consip S.p.A2, defined a framework contracts for the ESIF programmes, to standardise and centralise the process for all MAs, CAs and AAs, as well as IBs, to request and select expert support services and technical assistance (Consip, 2016[7]).

For the 2021-2027 programming period, the European Commission has proposed several reforms aiming to reduce administrative burden in ESIF implementation. These include establishing one single rulebook, the Common Provisions Framework, to cover all ESIF management; reducing the number of TOs to enable synergies and flexibility between various strands within a given objective; streamlining and reordering ex ante conditionalities according to their priority level; as well as simplifying access to funds for beneficiaries through fewer rules and lighter control procedures (European Policies Research Centre, 2019[8]). In addition, the European Commission is proposing that Simplified Costs Options be applied to small projects. Doing so would permit OP authorities and beneficiaries to agree on a specific budget and expected outcomes on a case-by-case basis and increase support of smaller projects. If well-implemented, these initiatives could have significant potential in reducing administrative costs and introducing greater flexibility for MAs and other authorities in ESIF management, as well as for beneficiaries (European Training Centre in Paris, 2018[9]).

Inconsistent control, verification and audit interpretations generate uncertainty

The procedures and guidelines for OP project selection, control and verification, and audits appear to be open to a degree of interpretation. This creates uncertainties with respect to eligibility criteria among project applicants, complicates the application process and affects monitoring and control mechanisms. The problem can be particularly acute with respect to control and audit activities. The problem arises when a controller interprets an application or procurement process in one way (e.g. nothing wrong), and a subsequent controller in another point of the monitoring and control process interprets it in another (e.g. something is incorrect). In some OPs, there are reportedly up to eight controls for large European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) projects, entailing a high likelihood of different control results. This type of uncertainty contributes to insecurity among beneficiaries, adds to the administrative burden of the MA (as each point of control can require additional documentation), and can result in financial corrections that may be highly onerous, particularly for smaller beneficiaries with small budgets and/or limited liquidity for project implementation. Ultimately, inconsistency in control processes can lead to delays, affect absorption, and limit the attractiveness of ESIF co-financing for beneficiaries. Different interpretations in audits also contribute to the lack of clarity, or degree of unpredictability, associated with project implementation. The problem that arises in audits is similar to the one described for monitoring and control processes: audit approaches (and sometimes findings) can differ by auditor or by on-the-spot verification teams.

To reach a satisfactory level of certainty within an MCS’s monitoring and verification process, instructions regarding all main issues/risks should be clear and easy to understand, free from vagueness or ambiguity, based on specific regulations as well as general guidelines. This may call for an agreed upon approach between the European Commission and Member States regarding a number of specific challenging issues requiring further clarification, in order to attain common understanding between all relevant stakeholders [i.e. beneficiaries, MA, national coordinating bodies, Certifying Authority (CA), and Audit Authority (AA)]. Doing so could permit parties to request the same evidence and reach the same conclusions upon specific issues, regardless of where within the MCS the control, verification or audit is being carried out. A consistent interpretation of rules by EU and national level auditors and evaluators and clear and agreed upon interpretation guidelines established among them, may be one step towards mitigating the problem. Nevertheless, after having clearly defined the interpretation on crucial topics and having arrived at a common understanding, the need to adapt to new guidelines should be expected from time to time.

There are number of activities that could be undertaken to help minimise the incidence or impact of an inconsistent interpretation of rules and regulations for control, verification or audit purposes. For example, annual meetings of an EU Member State’s national coordinating body for EU funds, its CA and AA could be organised in order to share experience and information, and formulate/promote a common understanding on specific cases. Incorporating MA perspectives and/or proposals in the preparation of such meetings (e.g. agenda setting) could be useful. It should be noted that such meetings are not intended to compromise the independence of the institutions involved, particularly in terms of undertaking their activities and reporting relevant findings. Rather, the aim is to gather as much expertise and perspective as possible to identify what is and what is not possible in specific cases. Opening these meetings to an observer from the European Commission/Audit bodies, as well as MAs even if on an ad hoc basis, may be valuable.

Another, potentially firmer, option is to pilot an Audit Committee. It could be composed of representatives from national (and regional where appropriate) audit bodies that could set interpretation standards, promote consistency for how rules are interpreted, establish who is responsible for auditing what, and avoid audit overlapping, ideally helping build stability and predictability into the system. If such a committee already exists at a national level, then consideration should be given to establishing a working group or sub-committee dedicated to establishing and agreeing upon a standard set of interpretations for ESIF project selection and control processes, and setting an audit plan that could be published and disseminated among stakeholders. While the upfront resource commitment may be high, in the medium to long run greater consistency and predictability in how rules are interpreted could help minimise problems, translating into greater stability in OP implementation and contributing to more efficient fund absorption.

At a minimum and if not already done, a reference of “control and audit precedents” should be published (electronically and/or on paper) and available to all stakeholders (e.g. IBs, beneficiaries, consultants, etc.). This could help guide project designers and applicants in understanding what may generate a red flag in the selection and implementation process, and help reduce the potential for irregularities and audits. It also could help controllers (and auditors) harmonise their interpretations.

Reinforcing capacity to manage public procurement processes

Clear and effective procurement laws and processes are integral to ESIF management and implementation, as well as to public investment in general. Improving the quality and reliability of public procurement systems can foster large savings: even a 1% efficiency gain could generate a savings of approximately EUR 20 billion per year in the EU (European Commission, 2019[10]). At the same time, procurement practices represent one of the largest framework challenges for MAs and beneficiaries alike. In many instances, particularly among smaller beneficiaries, there may be limited capacity in terms of resources and technical knowledge to effectively participate in and/or manage procurement processes (OECD, 2019[1]). Poor procurement practices, unclear or often-changing procurement laws, or lengthy procurement processes can all impede the effective implementation of ESIF projects. When these are combined with limited institutional capacity, inadequate knowledge of good procurement practices, or insufficient human resources to deal with procurement procedures, there is significant margin for procurement processes to lead to higher transaction costs and financial adjustments in the case of EU funds.

Procurement legislation is often complex and subject to constant updates and adjustments in order to address new issues and circumstances. For example, it is not unheard of for procurement laws to be adjusted six to eight times in a seven-year period (Surubaru, 2017[5]). One pilot MA experienced more than 280 amendments, modifications or additions to a new procurement law over a two year period. Keeping up with the changes, understanding their implications and how to apply them, then communicating these to IBs and beneficiaries, and actively helping ensure compliance is a fundamental yet resource intensive task of the MAs. Ensuring compliance, however, can be more difficult due to room for legal interpretation, particularly when the law is unclear or frequently changed. The Commission, under the coordination of DG REGIO, has developed the Guidance for practitioners on the avoidance of the most common errors in public procurement of projects funded by the European Structural and Investment Funds (2018[11]), which MAs and other authorities in the MCS can consult. The OECD has also developed a set of principles for good public procurement practices which could help MAs reinforce the strategic and holistic use of public procurement (Box 5.1).

Box 5.1. OECD work to promote better procurement practices

According to the European Court of Auditors, a significant part of EU Cohesion Policy funding, particularly for the European Regional Development Fund and the Cohesion Fund, is spent through public procurement. Meanwhile, failure to comply with public procurement rules is still a significant source of error in implementing Cohesion Policy. Nevertheless, systematic analysis of public procurement errors is limited in EU Member States.

The OECD has developed policy tools, case reviews and various research to help countries and regions improve their public procurement systems and practices. For example, the Methodology for Assessing Procurement Systems provides a tool for all countries to assess the quality and effectiveness of procurement systems. Country reviews have been conducted, ranging from special focus on competitive tendering, e-procurement system, to comprehensive analysis on the whole procurement system of the country.

In addition, the OECD Recommendation on Public Procurement was developed as a reference for modernising procurement systems and can be applied to procurement at all levels of government. It addresses the entire procurement cycle while integrating public procurement with other elements of strategic governance such as budgeting, financial management and additional forms of service delivery. The Recommendation is complemented by an online toolbox offering policy tools, specific country examples, and indicators for governments to assess and enhance the public procurement system.

Ensure an adequate degree of transparency of the public procurement system in all stages of the procurement cycle.

Preserve the integrity of the public procurement system through general standards and procurement-specific safeguards.

Facilitate access to procurement opportunities for potential competitors of all sizes.

Recognise that any use of the public procurement system to pursue secondary policy objectives should be balanced against the primary procurement objective.

Foster transparent and effective stakeholder participation.

Develop processes to drive efficiency throughout the public procurement cycle in satisfying the needs of the government and its citizens.

Improve the public procurement system by harnessing the use of digital technologies to support appropriate e-procurement innovation throughout the procurement cycle.

Develop a procurement workforce with the capacity to continually deliver value for money efficiently and effectively.

Drive performance improvements through evaluation of the effectiveness of the public procurement system from individual procurements to the system as a whole, at all levels of government where feasible and appropriate.

Integrate risk management strategies for mapping, detection and mitigation throughout the public procurement cycle

Apply oversight and control mechanisms to support accountability throughout the public procurement cycle, including appropriate complaint and sanctions processes.

Support integration of public procurement into overall public finance management, budgeting and services delivery processes.

Ineffective coordination mechanisms between a national public procurement administrative body and the ESIF management system actors can lead to time-consuming and inefficient procedures for resolving procurement issues arising from OP implementation, particularly given that the necessary communication to resolve problems will likely be ad hoc. Managing this situation will require better defining the procurement approach, and potentially better codifying how to address (or avoid) common problems in order to avoid procurement irregularities. This is particularly important for small and medium-sized beneficiaries that often lack the necessary technical knowledge to deal with complex procurement procedures (e.g. local authorities conducting and monitoring the whole procurement processes, or SMEs responding to a tender). Some MAs are introducing mechanisms, such as guidelines and early actions as a form of assistance, as well as thematic working groups dedicated to public procurement. Procurement challenges are an issue that MAs are acutely aware of and take what steps they can to support beneficiaries.

EU Member States are actively introducing practical mechanisms to better support procurement processes, which can be of value to MAs, IBs and beneficiaries. Such support includes procedure guidance, help desks, IT tools, and so on. For example, in France, the Ministry of Economy and Finance publishes an extensive manual on public procurement that includes methodologies for different procedures, examples of good practices, and Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs). It also operates a call centre and an e-mail inbox that helps handle questions from public buyers at local and regional levels. This type of tool serves as useful operational support for public buyers. Slovenia operates a telephone hotline, while Finland uses a one-stop-shop website, and in the Netherlands a help-desk offers guidance and help to any public authority undertaking a public procurement process. In the Czech Republic, a civil society organisation, the Association for Public Procurement, developed an online case-law collection on public procurement in a Lexicon on Public Procurement Law. It allows contracting authorities and bidders to better understand and interpret public procurement law. Meanwhile, Croatia has introduced IT tools such as electronic public procurement plans, prior market consultations for draft tender documents, and e-contract registers (European Commission, 2016[13]).

Table 5.1 below highlights some possible actions identified by the five MAs participating in this pilot project, and their stakeholders, to address these framework condition challenges.

Table 5.1. Sample Action Table: striving for simplicity, stability and clarity for OP implementation

|

Goal/Sub-goals |

Identified Potential Actions |

|---|---|

|

Reduce complexity, instability and administrative burden in the system, and build greater flexibility into the parameters for programmes Ensure more consistent interpretation of rules to build greater predictability and stability into the system Ensure greater clarity in procurement legislation and better manage uncertainty generated by governance practices and the procurement process |

✓ Support regular and accessible training and knowledge sharing mechanisms for technical/expert MA officials in understanding and applying new rules and regulations. |

|

✓ Introduce a Management and Control System Thematic Network of the MAs, the Certifying Authority and (other) national/regional bodies as well as the National Coordination Body/Authority to serve as an information/experience exchange platform. The participation of an observer from the Audit Authority, even on an ad hoc basis, could be considered. This network can also act as a forum to build the overall knowledge base and for consultation among MAs on system amendments, to discuss proposals for amendments to the legal framework, etc. |

|

|

✓ Organise annual meetings with national bodies, the Certifying Authority and the Audit Authority to share experiences and information, and enhance common understanding on specific cases. |

|

|

✓ Support the active participation of regional MAs in current or newly created networks dedicated to identifying common challenges and speaking to national and EU authorities in negotiation, legislative, regulatory and other rule-setting processes. |

|

|

✓ Pilot an Audit Committee with representatives from relevant national, regional, MA/IB auditing bodies that can disseminate planned controls and an audit calendar to relevant stakeholders, and establish and share consensus around the interpretation of regulations to avoid duplication in audits and create greater certainty for implementing bodies and beneficiaries. Such a committee could be modelled on one at the national level, or be a sub-group (i.e. a regional subcommittee) of the existing national level body. |

|

|

✓ Publish a reference of “control and audit precedents”, electronically and/or on paper, and make these available to IBs, beneficiaries, consultants, etc. |

|

|

✓ Test/pilot the inclusion of auditors in the full investment strategy design and programming cycle (i.e. OP design, priority setting, project design, selection and evaluation criteria, and selection process) to see if evaluations improve and irregularities decrease. |

References

[4] Bachtler, J. et al. (eds.) (2016), Different approaches to the analysis of EU Cohesion Policy - Leveraging complementarities for evidence-based policy learning, Routledge, http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9781315401867.

[7] Consip (2016), Gara Servizi di assistenza tecnica per le Autorità di Gestione e di Certificazione PO 2014-2020, http://www.consip.it/bandi-di-gara/gare-e-avvisi/gara-servizi-di-assistenza-tecnica-per-le-autorita-di-gestione-e-di-certificazione-po-2014-2020.

[10] European Commission (2019), Public Procurement, Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs, https://ec.europa.eu/growth/single-market/public-procurement_en (accessed on 23 August 2019).

[11] European Commission (2018), Public Procurement Guidance for Practitioners on on avoiding the most common errors in projects funded by the European Structural and Investment Funds, European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/policy/how/improving-investment/public-procurement/guide/.

[13] European Commission (2016), The Use of New Provisions During the Programming Phase of the European Structural and Investment Funds, Final Report, European Union, https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/policy/how/studies_integration/new_provision_progr_esif_report_en.pdf.

[8] European Policies Research Centre (2019), Reforming the MFF and Cohesion Policy 2021-27: pragmatic drift or paradigmatic shift?, European Policies Research Centre.

[9] European Training Centre in Paris (2018), ESIF Common Provisions Regulation: what’s new for 2020?, http://etcp.fr/esif-common-provisions-regulation-whats-new-2020/ (accessed on 26 August 2019).

[3] Ferry, M. and L. Polverari (2018), Research for REGI Committee – Control and simplification of procedures, European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2018/601972/IPOL_STU(2018)601972_EN.pdf.

[1] OECD (2019), Effective Public Investment across Levels of Government: Implementing the OECD Principles, OECD Publishing, https://www.oecd.org/effective-public-investment-toolkit/OECD_Principles_For_Action_2019_FINAL.pdf.

[2] OECD (2018), Rethinking Regional Development Policy-making, OECD Multi-level Governance Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264293014-en.

[12] OECD (2015), The OECD Recommendation on Public Procurement, OECD Publishing, https://www.oecd.org/gov/public-procurement/OECD-Recommendation-on-Public-Procurement.pdf.

[6] OECD (forthcoming), Monitoring Report on the Implementation of the Recommendation of Effective Public Investment across Levels of Government, OECD Publishing.

[5] Surubaru, N. (2017), “Administrative capacity or quality of political governance? EU Cohesion Policy in the new Europe, 2007-2013”, Regional Studies, Vol. 51/6, pp. 844-856, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1246798.

Notes

← 1. Grandfathering refers to regulations or legislation that is applied to cases only after the legislation has passed, rather than to all cases before and after the regulatory change.

← 2. Consip S.p.A. is a company exclusively held by the Italian Ministry of Economy and Finance. It serves only the public administration sector and operates as a central purchasing body through the use of ICT and innovative procurement tools.