People matter: the capabilities, resources, working conditions, motivations and values of public servants affect the efficiency of public service delivery and the effectiveness of European Structural and Investment Fund management. This chapter analyses key people management challenges for Managing Authorities across three areas: reinforcing skills and competencies, attracting and recruiting the necessary expertise, and engaging and motivating employees to put their skills to work.

Strengthening Governance of EU Funds under Cohesion Policy

Chapter 2. Investing in People for Administrative Capacity

Abstract

Introduction

People are the backbone of any organisation. The capabilities, resources, working conditions, motivations and values of public servants impact the quality of public governance, efficiency of public service delivery and the effectiveness of European Structural and Investment Fund (ESIF) management. OECD Member countries invest considerable resources in public employment. In 2015, an average of 9.5% of GDP was spent in OECD Member countries on general government employee compensation, making this the largest input in the administration of government programmes and services. However, many public administrations reduce the impact of this investment by providing sub-optimal public employment systems and resources that limit the impact of their employees. For this reason the OECD recently adopted the Recommendation on Public Service Leadership and Capability, which sets out 14 principles for a fit-for-purpose public service (Box 2.1).

Box 2.1. OECD Recommendation on Public Service Leadership and Capability

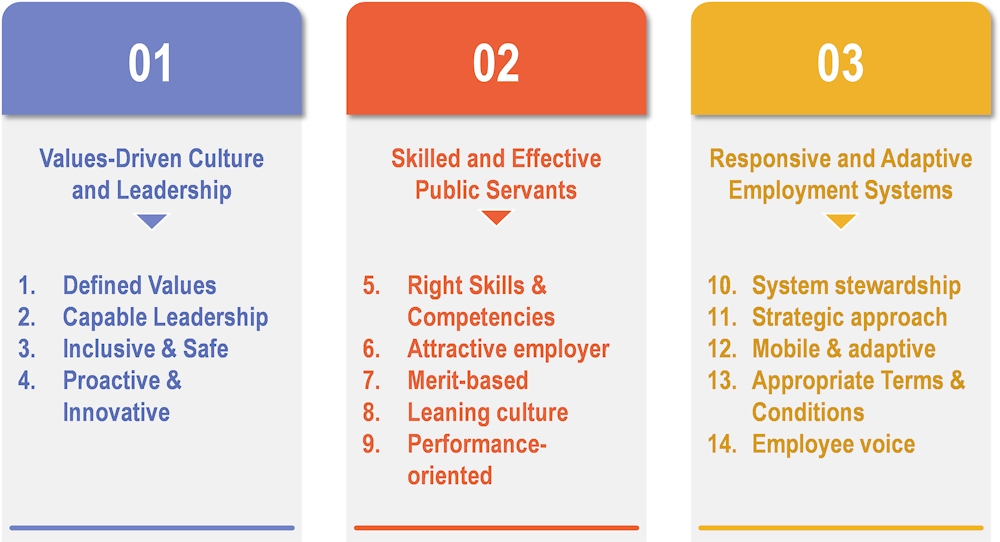

Recommendations of the OECD Council make clear statements about the importance of an area and its contribution to core public objectives. The Recommendation on Public Service Leadership and Capability (PSLC) is based on a set of commonly shared principles, which have been developed in close consultation with OECD countries. This included a broad public consultation, which generated a high level of input from public servants, citizens and experts from around the world. The Recommendation presents 14 principles for a fit-for-purpose public service under three main pillars (Figure 2.1):

Values-driven culture and leadership,

Skilled and effective public servants,

Responsive and adaptive public employment systems.

Figure 2.1. Principles of the OECD Recommendation on Public Service Leadership and Capability

Source: (OECD, 2019[1]). The full text of the Recommendation can be downloaded at: https://www.oecd.org/gov/pem/recommendation-on-public-service-leadership-and-capability-en.pdf

The quality of people and the way they are managed sits at the core of the analytical framework developed by the OECD for this project. In terms of human performance, the well-established Motivation-Opportunities-Ability (MOA) framework states that people need three things in order to achieve their objectives: Motivation; Abilities; Opportunities:

Abilities refer to the skills and knowledge contained within the workforce, and how different workforce development tools, such as training and recruitment, are used to build up the right workforce to deliver.

Motivation can be intrinsic – driven by the desire to improve economic development in one’s community and ensure prosperity for future generations – or it can be extrinsic – e.g. material rewards and sanctions. This puts focus on leadership and management, employee engagement, performance assessment systems and other incentives.

Opportunity to put the skills and motivation to work is the third ingredient to human performance. Here, one can analyse workforce deployment and worker mobility, organisational structure and work design, access to knowledge and resources, etc. This is further discussed in Chapter 3.

Building the capacity of public administrations for better use of EU funds (programming, implementing and verifying) covers a range of operational staff, political and executive leadership, senior management, and organisational structures/factors. The challenges discussed below examine the mix of skills and competences the Managing Authority (MA) seeks to attract and develop in pursuit of better ESIF management. It also looks at how managers and leadership influence workforce development in line with strategic objectives and key activities such as stakeholder management. Securing the timely availability of skilled and motivated staff is a key success factor in the management of public policies; and conditions within the public administration need to be favourable towards recruiting and retaining such professionals.

Issues such as those relating to human capital and the delivery of Cohesion Policy are at the heart of a key evaluation of the 2007-2013 Programming Period. This evaluation suggests that Technical Assistance (TA) was an important tool to improve people and organisational issues in MAs (European Commission, 2016[2]), and it offers interesting insights into the nature of the challenges faced by MAs:

reinforcing human resources was an important dimension that received TA in all case study countries;

in addition to direct financing of human resource development, remuneration and operating costs often dominated the spending structure of TA;

higher remuneration, e.g. in the form of top-ups allowed to retain trained staff reduced staff turnover;

the development of systems and tools with a focus on management, monitoring and reporting capacities was a key priority of capacity-building activities in almost all case studies, which is explained by the necessity to set up appropriate IT systems.

The most important developments were found to be:

reduction of initially high staff turnovers;

set-up of management and monitoring information systems;

elaboration of tools and procedures for effective knowledge transfer;

mitigating problems with complex public procurement rules;

contributing to the development of evaluation culture.

The primary source for data is qualitative semi-structured interviews with stakeholders carried out in each of the MAs. As such, the conclusions below reflect the aggregate perceptions of staff across the MA in each of the five MAs. Each challenge may not apply directly and wholly to every MA. Nevertheless, each MA participating in the pilot project is affected to greater or lesser degrees by each of the challenges.

Reinforcing skills and competencies for a Managing Authority performance

There is broad consensus that the ‘future of work’ will pose serious challenges to governments, firms and workers. The world of work is changing, skills needs are evolving, and automation has already begun to upend some industries and professions. Against this background, MAs and the public administrations within which they sit have a vital role to play in developing a workforce that is fit-for-purpose and able to adapt to uncertain and rapidly-changing circumstances. Recognising this challenge, the PSLC recommends that OECD countries continuously identify skills and competencies needed to transform political vision into services which deliver value to society, in particular through:

a. Ensuring an appropriate mix of competencies, managerial skills, and specialised expertise, to reflect the changing nature of work in the public service;

b. Reviewing and updating required skills and competencies periodically, based on input from public servants and citizens, to keep pace with the changing technologies and needs of the society which they serve; and

c. Aligning people management processes with identified skills and competencies.

Figure 2.2. OECD Skills Framework for a High Performing Civil Service

The OECD’s 2017 report on Skills for a High Performing Civil Service outlines a generic skills mix necessary in all public sector organisations, which was then adapted to the needs of MAs (Figure 2.2) (OECD, 2017[3]). To assess changes in the skills needed in today’s civil services, the OECD framework identifies four areas, each representing specific tasks and skills required in the relationship between the civil service and the society it serves:

Policy advice and analysis: Civil servants work with elected officials to inform policy development. However, new technologies, a growing body of policy-relevant research, and a diversity of citizen perspectives, demand new skills for effective and timely policy advice. While MAs may not engage directly with elected officials for policy making, there is a need for policy-related skills in MAs to contribute, for example, to the design of OPs, and ensure that project selection is well aligned.

Service delivery and citizen engagement: Civil servants work directly with citizens and users of government services. New skills are required for civil servants to effectively engage citizens, crowdsource ideas and co-create better services. While MAs may not directly engage with a wide group of citizens, they work with a range of stakeholders, including beneficiaries.

Commissioning and contracting: Not all public services are delivered directly by public servants. Governments throughout the OECD are increasingly engaging third parties for the delivery of services. This requires skills in designing, overseeing and managing contractual arrangements with other organisations. This is a core skillset in MAs since much of their work requires the establishment of complex funding and financing arrangements for complex projects.

Managing networks: Civil servants and governments are required to work across organisational boundaries to address complex challenges. This demands skills to convene, collaborate and develop shared understanding through communication, trust and mutual commitment. MAs work as one part of a very complex delivery system, collaborating with other government departments, levels of government, NGOs, private sector entities and others.

Professional civil services are as important as ever to respond to complex challenges and to deliver public value. However, in addition to their professional qualities, civil services must also be strategic and innovative. The framework evaluates the four skills areas mentioned above in light of these three qualities:

Civil servants in a professional civil service are qualified, impartial, values-driven and ethical. These are foundational and suggest the need to ensure civil servants are certified professionals in their area of expertise.

Professional civil servants will also need to be future-oriented and evidence-based. This requires the acquisition of strategic skills, particularly at management levels, to encourage collaboration between areas of expertise and across the four parts of the framework discussed above. This includes skills related to risk management, foresight and resilience.

Sometimes professional and strategic skills reach their limits due to legacy structures and systems of public sector organisations. In these cases, civil servants need to be innovative to redesign the tools of governance and develop novel solutions to persistent and emergent policy challenges.

The skills model identifies various gaps in MAs

Applying the skills model above to the five MAs that participated in this pilot action, the following strengths and gaps could be identified.

Policy advice and analysis skills: The need for a more strategic approach to MA management (discussed in Chapter 4) was often raised during the OECD missions to the five MAs. However, in some MAs, the MA was essentially divorced from any policy function, and instead was positioned as an operational delivery mechanism to various extents. In this way, there was insufficient concern for developing and leveraging policy skills in the MA that could contribute to the design and development of ROPs, and align the work of the MA to the regional development strategies that they advance. Given the proximity of the MA to the delivery of strategy, this raises risks around misalignment of MA activities (e.g. project selection) with strategic objectives. If an MA uses only operational KPIs (e.g. amount spent, number of financial corrections), for example, it may risk not achieving the objectives of the policies that guide their work. In addition, MAs have a lot of practical experience that could be leveraged for better ROP/regional development strategy development.

Service delivery and engagement: While MAs may not deliver services directly to citizens, they do so with beneficiaries. In all of the diagnostics there was a recognition of the need to better communicate and engage with stakeholders beyond the MA, and in particular with ESIF beneficiaries. Some MAs work very closely with their beneficiaries and count them as close partners in the operation of successful ESIF. There was often recognition that beneficiaries not only needed more information and support to prepare and implement projects, but also had insights that could be used to improve the design of strategies and processes by the MA. Part of the challenge is that stakeholder management and engagement tend not to be a professionalised function in most of the MAs that participated in this pilot action, and therefore is often undertaken by people who do not see it as core to their work, and who lack the necessary skills and time.

Commissioning and contracting: MAs carry out a range of actions related to the control, distribution and use of ESIF funds, such as ex-post control and reviewing the lawfulness of public procurement during verification of beneficiary expenses. This is a core function of the MAs and is an area of clear need for capacity-building on the skills and competencies required to carry out effective and efficient public procurement tenders. Rarely do employees of an MA have a background in engineering or other technical specialties that would enable them to fully understand the complexity of the projects they manage. With this kind of skills asymmetry, many MAs resort to rule-oriented process specialisation (e.g. ensuring that forms are filled out correctly) rather than substance and understanding (e.g. ensuring that what’s in the forms really makes sense and is viable). A related challenge is that the rules they follow are often perceived to be somewhat vague and open to interpretation, and therefore require a high degree of legal understanding and authority. This is further discussed in Chapter 5.

Managing networks: Collaboration within the MA and across the Management and Control System (MCS) is another area which emerged as a common challenge, particularly when multiple ministries and agencies, levels of government or sectors are required to work together to develop and implement ESIF-funded projects. This kind of coordination function was also rarely centralised and professionalised, but rather dispersed across the MA and not always conducted systematically. This suggests the need to recognise this as a core skill and support its development and deployment.

Turning to the three dimensions (professional, strategic and innovative) of the framework also enables a discussion of the following gaps:

Professional: Most MAs struggle to find people with the right qualifications and knowledge. This is generally due to a combination of labour market limitations, unattractive pay and employment offers, and/or hiring constraints imposed across the civil service (e.g. hiring freezes). In order to find a solution, many MAs resort to hiring generalists who learn to follow complex rules without the professional skills needed to understand the complex projects and systems they are managing.

Strategic: Aligning MA operations with strategic objectives of OPs and development strategies requires effective leadership and management to link the various work streams in a coherent manner. Management and leadership skills were often identified as lower priority in many MAs. They were often not prioritised in recruitment and promotion. In some cases, senior managers are appointed by political leaders with little control in place to ensure they have the necessary skills and knowledge.

Innovation: With a rules-based system where employees only see their small part and have little time to consider improvements, it is not easy to identify the ways forward in terms of system improvements. Most employees interviewed felt a sense of powerlessness to make adjustments that they felt would improve operations and strategic impact of the MA.

To fill the skills gaps identified, MAs can use a combination of recruitment and training. The next parts of this Chapter look at those in turn.

Attracting and recruiting the necessary expertise

Recruiting candidates to fill skills gaps requires two interrelated functions. First, MAs need to be able attract candidates to apply for the positions they need. The OECD PSLC Recommendation suggests that public organisations attract and retain employees with the skills and competencies required from the labour market, in particular through:

1. Positioning the public service as an employer of choice by promoting an employer brand which appeals to candidates’ values, motivation and pride to contribute to the public good;

2. Determining what attracts and retains skilled employees, and using this to inform employment policies including compensation and non-financial incentives;

3. Providing adequate remuneration and equitable pay, taking into account the level of economic development; and

4. Proactively seeking to attract under-represented groups and skill-sets.

Secondly, public sector organisations need to use an appropriate set of tools to assess candidate skills and ensure they choose the candidate most likely to perform well in the position. Hence, the PSLC recommends recruiting, selecting and promoting candidates through transparent, open and merit-based processes, to guarantee fair and equal treatment, in particular through:

a. Communicating employment opportunities widely and ensuring equal access for all suitably qualified candidates;

b. Carrying out a rigorous and impartial candidate selection process based on criteria and methods appropriate for the role and in which the results are transparent and contestable;

c. Filling vacancies in a timely manner to remain competitive and meet operational staffing needs;

d. Encouraging diversity – including gender equality- in the workforce by identifying and mitigating the potential for implicit or unconscious bias to influence people management processes, ensuring equal accessibility to under-represented groups, and valuing perspective and experience acquired outside the public service or through non-traditional career paths; and

e. Ensuring effective oversight and recourse mechanisms to monitor compliance and address complaints.

MAs were generally very restrained in their abilities to recruit candidates to fill skills gaps

Regarding attractiveness, many MAs report low numbers of qualified applicants to job openings. This is often due to a range of factors such as pay freezes and tightening labour markets. In cases where the pay is too low to attract the needed skills, MAs and their leadership should carefully consider options to provide a more competitive employment package. Many MAs do this by using their Technical Assistance budget to “top-up” the salaries of those working on ESIF. MAs report that this has helped reduce some problems related to staff turnover, although such problems still exist in many MAs due to heavy workloads and stress. It also affects internal salary equilibrium across the broader public administration.

In order to attract professionals, MAs could more clearly articulate the non-financial benefits of working in their organisation, appealing to candidates’ desire to contribute to economic development and learn how ESIF processes work. This kind of employer branding effort has to be reinforced with real support, however. The use of on-boarding mechanisms or induction training and career development tends to be under-developed in MAs and these tools, if well developed and communicated about, can help to attract promising candidates.

In some MAs, the specific hiring process is conducted by the MA with approval from a central authority, and here steps could be taken to improve hiring processes to align with strategic orientations of the OP. Hiring criteria could be better aligned to the skills needed and/or the willingness and ability to develop them, and hiring managers could be more effectively trained in selection techniques. Another action that appears in some of the Roadmaps is to better coordinate with universities and leverage possible expertise among students and faculty for specific projects that could add value to the MA.

In most of the participating MAs, the biggest problem with recruitment were freezes imposed by central administration offices. In many cases, MAs were not free to hire new staff to meet operational needs without agreement from central authorities, even when funding was considered available. There was often a sense of frustration that the relevant HR authorities (e.g. the HR office of the ministry housing the MA, and/or ministry of public administration) did not understand the specific needs of MAs and were very slow to react to requests. MAs often felt captured in a public employment system that was not fit to their purpose.

Slow and ineffective public employment and HR systems, coupled with what appears to be an increased workload in many MAs, is creating high-stress working environments in which not even TA top-ups are enough to retain the best employees and keep them engaged and motivated. This generated in a sense of powerlessness among MA management and leadership, which lacked the tools and support necessary to make the changes needed to improve their workforce development situation. In that sense, most of the skills development focus was on training rather than on recruitment possibilities.

Nevertheless, there are examples of MAs that have developed innovative solutions to recruitment challenges. For example, in preparation for the 2021-2027 period, Calabria, Friuli-Venezia-Giulia and Umbria in Italy have collaborated to set up a registry of chartered accountants specialised in the management and control of programmes co-financed by ESIF (Agenzia per la Coesione Territoriale, 2019[4]). This project was extended to include other administrations, such as those in Emilia-Romagna, Liguria, Sicilia and Trento. The purpose is to facilitate access by MAs to candidates with sought-after skills but who can prove difficult to attract. The registry was be piloted until end 2019 and will be assessed by independent evaluations occurring as part of the Italian Plans for Administrative Reinforcement (PRA).

Table 2.1 below highlights some possible actions identified by the five MAs participating in this pilot project, and their stakeholders, to address the challenge of taking a more strategic approach to recruitment.

Table 2.1. Sample Action Table: re-examining recruitment strategies

|

Goals/sub-goals |

Identified potential actions |

|---|---|

|

Encourage more people to apply for positions at the MA Test a broader range of skills and competences during assessment Identify ways to link recruitment to business needs |

✓ Greater effort to reach a broader range of prospective candidates through different media |

|

✓ Development of a competency framework for use in recruitment and performance assessment |

|

|

✓ More strategic use of temporary staff contracts where standard recruitment procedures are not possible |

|

|

✓ Identify ‘offer’ to prospective candidates |

Given the significant limitations placed on recruitment, most MAs aim to address skills shortages through training opportunities for their current workforce. In this area, assessment is not only needed in the quantity of training available to staff (cut back in most OECD countries following the 2008 crisis), it is critically important that the quality of training is aligned with organisational objectives and labour market needs. Training also goes beyond a tool for equipping staff with the know-how they need to perform tasks. Metsma argues that it plays a key role in staff motivation, and indeed surveys of recent graduates frequently cite the opportunity to learn as a key motivator (Gallup, 2016[5]). Moreover, training can also be seen as a tool to inculcate shared values and a positive organisational culture (Metsma, 2014[6]).

The PSLC takes a similarly expansive view of training and development and recommends developing necessary skills and competencies by creating a learning culture and environment in the public service, in particular through:

a. Identifying employee development as a core management task of every public manager and encouraging the use of employees’ full skill-sets;

b. Encouraging and motivating employees to proactively engage in continuous self-development and learning, and providing them with quality opportunities to do so; and

c. Valuing different learning approaches and contexts, linked to the type of skill-set and ambition or capacity of the learner.

Training in MAs meets some short-term needs but there is scope to take a more strategic and long-term approach to leaning and development

Two recurring themes in interviews with MA staff were (i) that training was insufficient to keep them abreast of the latest developments with legislation, regulations, procedures and processes; and (ii) that training was not perceived as something that added significant value to day-to-day work and longer-term career and personal development.

For example, in one MA, staff noted that training courses occurring abroad were seen by managers as ways to reward staff. While this may be considered a legitimate management technique designed to galvanise performance (and in some cases was perceived to be the only “reward” that the management team could offer to high-performers), the result was that part of the staff conceived of training as a ‘perk’ or bonus to be assigned by a hierarchical superior. In another MA, new staff are immediately entrusted with significant responsibilities but lack the training and guidance to carry them out effectively.

In some cases, managers volunteer to run training sessions based on their own experience. While this is a laudable effort to transmit knowledge, it is illustrative of the constraints the MA faces in developing a comprehensive learning and development strategy. In another MA, where staff were obliged to attend a minimum number of training courses each year, there was a clear signal in interviews that the training did not meet the expectations of staff or add value to day-to-day work.

What emerges from the above examples is that, on the whole, training initiatives are either un-coordinated or carried out on an ad-hoc basis. Or, where a training strategy exists, there is little evidence to suggest that it is systematically applied and reviewed.

Staff expressed a desire for training that could improve their skills, improve the work of their MAs, and improve the impact of the projects they manage. Training was often requested on specific legislative and regulatory/procedural requirements for ESIF administration because many staff felt that these complex requirements changed often, at short notice, and with little consultation on their design or impact. This sense of ‘moving the goalposts’ creates delays in programming due to the need to learn and adapt to new requirements. It increases the workload of staff, pushes up transaction costs in engaging with actors at various levels of the MCS, and over time can lead to demotivation and disengagement.

In most OECD countries, competency frameworks are used to align training and development to organisational and individual development needs, and link training to career progression. The lack of a competency framework in most MAs means training does not address the long-term needs of the organisation, nor of individuals. Instead, training is either seen as a perk or a burden rather than as a core staff and organisational development activity.

There also appeared to be very little investment in induction training for new hires or those recently assigned to new roles and tasks. Many of the staff in MAs recognised that formal induction programmes could help new hires to learn about the strategic importance of their jobs, and how they fit into the broader ESIF system. However, in the absence of such programmes, new hires and existing staff are expected to learn ‘on-the-job’ with little systematic support.

Work load pressure means training is rarely prioritised or encouraged. This is particularly true when learning is not well aligned to the needs of individuals and their organisations. If training is not appropriately tailored to local reality, it risks getting labelled as a waste of time and written off completely.

Targeted management/leadership training was particularly underdeveloped. This may in part be due to a sense that managers in some MAs have very little discretion, and senior leaders are sometimes political appointees with little long-term commitment and vision for the MA. However these perceptions suggest an even greater urgency for meaningful leadership interventions.

The Campania region in Italy may provide food for thought in this regard, as it carries out a gap analysis on skills for the senior management of the Regional Council of Campania (Agenzia per la coesione Territoriale, 2019[7]). The results of this analysis are shared with the National School of Administration, which then plans training accordingly. The process is governed by a special agreement between the SNA and the Campania Region.

There is also little engagement with beneficiaries to identify their training needs, despite broad acknowledgement that time invested in training beneficiaries on various programming procedures pays off in the long-term with fewer errors in paperwork. While training beneficiaries may not always be the MA’s immediate responsibility, there was often recognition that the capacity of many beneficiaries urgently needed improvement, and investments in this area, by MAs, National Coordination Authorities or others, would be an investment with high return.

Towards a more strategic approach to learning and development

Training is a valuable tool in addressing skills and competency gaps. However, one of the key observations of this project is that the scope of much of the training carried out by MAs is relatively narrow. The analysis conducted of the five diagnostics reveals that the complexity of managing EU funds requires a broader perspective and range of professional competences. Rather than just playing a stop-gap role to ensure MA staff implement changes in legislation, learning and training should contribute to the strategic development of the MA and its employees. In this sense it should differentiate between the needs of staff at the operational and leadership levels. The operational and strategic challenges faced by MA staff require the development and deployment of a range of behavioural, cognitive and interpersonal competencies, such as creative problem-solving, strategic thinking and communication, negotiation and complex project management.

Ahead of the post-2020 period, this is a significant challenge. Success in channelling ESIF will depend not only on accumulated institutional expertise, but on the ability of MAs to develop a targeted, relevant and accessible learning and development strategy that goes to the heart of the operational and strategic challenges faced by staff. The main vehicle for MAs to reach the adequate level of skills and competencies to manage ESIF is a long-term “learning and developing strategy” which should also include an institutional link to hiring processes and job profiles in the MA.

To develop such a strategy, an important preliminary step, highlighted in many of the Roadmaps, is the need for an evidence-based gap analysis, to understand which skills and competences are available in the MA, and which ones should be developed in order to properly manage ESIF-financed projects. The European Commission’s competency framework and self-assessment tool is designed to provide this kind of analysis (Box 2.2).

Box 2.2. EU Competency Framework for the management and implementation of the ERDF and the Cohesion Fund

The implementation of European Regional Development Fund and Cohesion Fund Programmes requires strong administrative capacity. Therefore, the European Union developed a tool that addresses the competencies of employees involved in the management of the funds. These include the following practical tools that support human resources development:

The Competency Framework covering all institutions involved in the management of the funds.

The competency Self-Assessment Tool based on the Competency Framework.

A recommended training Blueprint.

The Competency Framework and Self-Assessment Tool are job-aids to help institutions managing the funds in strengthening their human resources capacity. The Competency Framework and Self-Assessment are flexible and customizable, so that they apply to the different organisational structures in the Member States. The Self-Assessment Tool allows for a competency assessment on individual and institutional level. The outcomes of the assessment provide an important base for individual development plans, overarching human resources strategies and training plans. The recommended Blueprint for a European Regional Development Fund and Cohesion Fund training provides guidance on the structure of a learning offer, which is functional to strengthening the competencies defined in the Competency Framework.

Source: (European Commission, 2016[8])

Based on an assessment of skills gaps, a learning strategy could then map out different learning opportunities that could be used to help fill those gaps. This may include courses offered locally, by national schools of government, by the national coordination authority, by the EC or private contractors. It could also include other forms of learning, such as mentorship and coaching, job shadowing, short-term assignments and secondments. This mapping of different learning opportunities is an essential step as often MA managers were unaware of training and development opportunities within their own administrations, and at the European level (Box 2.3).

The OECD has worked with several EU countries to map and develop capability in thematic areas. For example, the Public Procurement Unit of the OECD Directorate for Public Governance worked with local authorities in Bulgaria to support the development of administrative capacity, training and dissemination of information, ensuring the effective application of public procurement rules through appropriate mechanisms. This included a ‘Train the Trainers’ initiative where the purpose was to provide future trainers with high quality material on public procurement to enable them to train procurement officials effectively all around the country (OECD, 2016[9]).

Box 2.3. Regional Competence Centre for Simplification in the Friuli Venezia Giulia region in Italy

The Friuli Venezia Giulia (FVG) Region is one of 20 Italian regions. Located in the north east of the country, bordering with Austria and Slovenia, it established a Regional Competence Centre to meet training needs that cannot be met by the regional staff training programme. Under the programme, regional and local civil servants have formed a "community of innovators" to improve the analysis and design capacity of public services, focussing on improving skills, such as use of data, that are not traditionally tested for during recruitment, even at management level.

Since February 2018, the Centre for Regional Competence for Simplification has conducted around 40 interviews with regional managers and officials, to build an evidence base for future learning and development strategies.

Training actions are organized using the “agile” logic underlying the digital development, maximizing the learning process in experimental workshops of construction and team work. Classroom groups gather all the roles involved in the process and its digital review: service managers, officials and project managers, managers of other services, analysts and software developers. Originally designed for about sixty regional employees, the programme was enriched along the way with new requests from participants in the first modules.

The Regional Competence Centre is working towards the development of a 2020-2021 training plan focussing on equipping administrators and officials of municipalities with the competences to work flexibly and adapt to changing circumstances, and to engage better with stakeholders.

Another focus of the learning and development strategy should be on managers, as they constitute a key group that should take part and benefit from training. In this sense, the strategy should be linked to organisational hierarchy, so that new managers and those who aspire to become managers can access learning opportunities that will maximise their impact and ensure they have the skills necessary to manage and motivate teams.

With a precise strategy, by defining their “starting level”, managers could assign learning objectives to staff, which could access the strategy to understand how their skills and competencies can evolve and help their career and personal development.

Two other key elements of this strategy could also be the implementation of induction and mentoring programmes. Induction training is fundamental to accelerate the process of integration for new staff. Mentoring, which could be included as part of an induction programme, is crucial to avoid the loss of experience when staff leave for jobs outside the MAs.

A mentoring programme could also be applied to new managers to facilitate their transition to new responsibilities, as well as dedicated coaching or training sessions. The direction to pursue is the design of a common training and, eventually, a common competency framework.

Encouraging staff to take greater ownership of their own learning and development objectives, such as through creating a greater link with periodic performance assessments or the development of an ‘on-demand’ course catalogue for common training needs would be one way to shift the perception of training.

Table 2.2 below highlights some possible actions identified by the five MAs participating in this pilot project, and their stakeholders, to address the challenge of taking a more strategic approach to learning and development initiatives.

Table 2.2. Sample Action Table: taking a more strategic approach to learning and development initiatives

|

Goals/sub-goals |

Identified potential actions |

|---|---|

|

Training that corresponds to day-to-day and strategic business needs Training that caters for different levels, i.e. operational level and management Training integrated to performance management as part of a long-term training strategy or plan |

✓ Conduct a training needs analysis |

|

✓ Develop alternative formats to classroom-based training, such as interactive workshops, online courses, role-playing exercises, etc. |

|

|

✓ Develop a plan or strategy to frame learning and development needs for the MA |

|

|

✓ Pilot a short-term mobility programme to enable MA staff to experience the work of different units of the MA |

Engaging and motivating employees to put their skills to work

Engaged employees are those who are “committed to their organisation's goals and values, motivated to contribute to organisational success, and are able at the same time to enhance their own sense of well-being” (Macleod and Clarke, 2009[11]). Levels of engagement matter significantly for an individual’s performance and have proven to be one the best predictors of individual task performance and organisational citizenship behaviour (loosely defined as voluntary activities that go beyond the tasks required in a work contract and that support organisational effectiveness) (Rich, Lepine and Crawford, 2010[12]). Empirical evidence, for instance, links employee engagement to improved productivity and willingness to innovate. For example, employees with high levels of engagement are much more likely to:

contribute to innovation by involving themselves and their ideas in their work (Salanova and Schaufeli, 2008[13])

strengthen resilience and self-initiative by asking for feedback and support, if needed (Bakker, 2011[14])

work energetically without suffering from burnout (Salanova and Schaufeli, 2008[13]), and;

are able to detach from work (Sonnentag, Binnewies and Mojza, 2010[15]). This is relevant for HR policies that focus on the reconciliation of work and family, work-life balance and corporate health management.

These benefits can, in turn, translate into improved outcomes for organisations. Indeed, organisations with engaged employees report cost savings from higher levels of retention and fewer lost days from sick leave. They also have improved outcomes in the form of higher levels of citizen satisfaction with public services. For example, one study shows that 78% of highly engaged public sector employees say they are able to impact public service delivery, while only 29% of disengaged employees feel the same way. In Germany, the federal civil service agency has found a link between levels of employee engagement (as measured through a composite index) and levels of reported citizen satisfaction with public services.

Because of the importance of employee engagement, many governments closely monitor this factor through civil service employee surveys which enable public employment practitioners to identify areas of high and low engagement and thereafter take appropriate action. Most commonly, employee surveys are used to gauge engagement levels in individuals, teams and organisations.

When defining and measuring engagement, it is important to distinguish between an employee’s commitment to the organisation (organisational commitment, or “organisational engagement”) and engagement with their job (work engagement). Organizational commitment is defined as a psychological attachment of employees to their organisations. Allen and Meyer (1990[16]) developed a model of organizational commitment that conceptualizes commitment as consisting of three components: affective, normative and calculative.

Affective commitment refers to a positive feeling of affection towards the organisation as reflected in a strong desire to remain and a feeling of pride in being part of the organisation.

Normative commitment reflects a moral feeling or obligation to continue in the organisation. Employees with high levels of the normative component feel that they ought to remain, and they feel bad about leaving the organisation even if a new employment opportunity appears.

Calculative commitment reflects an intention to remain in the organisation because leaving would have tremendous negative effects in terms of costs to the employee.

On the other hand, work engagement has been also described with critical elements such as work focus, energy and absorption in a job. Schaufeli et al. defined it as a ‘positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigour, dedication, and absorption’ (Schaufeli et al., 2002[17]).

Vigour refers to high levels of energy and mental resilience while working, the willingness to invest effort in one’s work, and persistence even in the face of difficulties.

Dedication is characterized by a sense of significance, enthusiasm, inspiration, pride and challenge at work.

Absorption consists of being fully concentrated, happy and deeply engrossed in one’s work whereby time passes quickly, and one has difficulty detaching oneself from work.

It is important to note that both organisational and work engagement are distinct but related concepts in terms of impacting performance. That is, some employees in an organisation can be engaged with their work but not committed to the organisation. Or conversely, committed to the organisation but not engaged with their work. Of course, it is also possible for employees to be both committed and engaged (the ideal) or neither committed nor engaged.

Employee engagement is suffering in some MAs

It was beyond the scope of the diagnostic phase of this pilot project to conduct employee surveys to gauge and compare levels of engagement in MAs or Management Control Systems more broadly. As such, it is important to note that the following assessment has been made on the basis of (representative) multi-stakeholder workshops and interviews. For the same reason, it is also difficult to ascertain the exact drivers of low employee engagement, where it was reported. This lack of data on engagement, however, is perhaps the most important finding in and of itself, as this is an important metric that MAs and MCSs should be systematically monitoring.

Anecdotally, several (though not all) of the five participating MAs reported issues with low employee engagement stemming namely from: perceptions of poor management practices; lack of career development opportunities; perceived lack of fairness in the assignment of promotions, bonuses, or training opportunities; and high levels of workload (particularly during certain times of the year and for those dealing with both beneficiaries and other government institutions). A perception of highly bureaucratic procedures, and the implications this had on individual ability to carry out duties effectively, was also mentioned as a possible source of frustration for employees and of lower engagement. Unsurprisingly, the MAs reporting higher levels of employee turnover (churn) were those also reporting lower levels of engagement.

Performance management systems were also reported to influence levels of employee engagement. While well-intentioned, some fell short of individual staff expectations since they were not seen as being linked to career development opportunities or salary increases. On the whole, performance management regimes did not result in employees receiving constructive feedback, but rather they seemed to have a significant effect on the motivation of staff, who felt that their efforts are not being recognised or rewarded, causing some to eventually burn out and leave the MA.

As mentioned earlier, many countries actively manage employee engagement. This is usually based on a process of measurement through employee surveys, which enable public organisations to benchmark their results, identify areas of high and low engagement, and take appropriate action. Well-designed employee surveys enable an understanding not only of relative levels of engagement across and within organisations, but also the factors that drive low or high engagement, and thereby the levers available to management to address and improve engagement

The majority of participating MAs do not have in place a strategy for measuring or improving employee engagement, with little to no data from employees collected through perception surveys. As such, the Roadmaps focus on addressing this critical “information gap” through the development and implementation of their own employee surveys. This is a key first step to assessing where problematic teams/leadership might exist, as well as uncovering the specific drivers as per different entities within the MA or MCS. MA or MCS employees who are also civil servants might complete employee surveys implemented by their central or regional administrations, however given that many personnel working on ESIF may be public employees (i.e. without civil service status), or contractors, it was deemed important that MAs design and run their own surveys aside from these.

While collecting quality employee engagement data is one key first step, this is certainly not sufficient without adequate follow-up and action from leadership. Indeed, measuring employee engagement through employee surveys will not, in itself, contribute to improving employee engagement levels if nothing is done with the results. As such, several Roadmaps include actions to conduct leadership workshops or seminars around employee engagement to review and discuss results, with the ultimate goal of designing and implementing interventions that address pockets of low engagement.

Managers and leadership were targeted for the seminars for several reasons. First, middle to upper managers have the power to implement changes that may boost engagement. Issues like work-life balance and the working environment are areas where managers can have a high degree of influence. Additionally, managers’ leadership styles can influence engagement – the way they communicate with employees, for example. The United Kingdom offers an example on the types of leadership behaviours that were found to increase engagement (Box 2.4). This places expectations on the skills and capacities of managers. Positive leadership traits and behaviours should be reflected in competency frameworks, which were also reflected in other Roadmaps actions to strengthen managerial capacities.

Box 2.4. Leading for engagement: Findings from the UK experience

While organisational hierarchies change over time, the metadata from the People Survey on team-level reports provides information that can link team-level results over time.

In 2014 and 2015, the Cabinet Office team linked team-level data from the 2011 to 2014 surveys to identify two types of teams: those that had maintained high levels of employee engagement or well-being over the timespan, and those that had seen substantial increases in the levels of employee engagement or well-being. Having identified these types of teams, case study interviews were undertaken with a selection of employees that represented the range of different activities in government (policy advice, corporate services, front-line service delivery, regulation, etc.). The results of these case study interviews identified eight common factors that support high or improved levels of employee engagement and well-being:

Leaders who are passionate, visible, collaborative and welcome feedback.

Prioritise feedback, involvement and consultation.

Encourage innovation and creativity.

Make time for frontline exposure.

Challenge negative behaviours.

Support flexible working approaches.

Build team spirit and create time for people to talk to each other.

Take action on People Survey results.

Second, in the Roadmaps, managers were chosen as the recipients of the workshops/seminars on engagement in order to create a sense of accountability around this important issue. Comparative data (i.e. benchmarking employee engagement results by team or organisational units) can be a powerful incentive for managers to make real changes. Countries like Australia, Canada, the UK and the US use Dashboards to communicate results, and employee engagement data are included in performance discussions.

Concerning performance management systems, MAs sometimes have a degree of flexibility on the application of these regimes, which the OECD often found to be misaligned to promoting engagement and motivation. Roadmaps therefore included actions focused on reviewing performance management systems to ensure that they are rewarding the kind of performance expected and encouraging employees, rather than focusing only negative consequences. The actions also emphasized improving communication around the tools, so that staff had a better understanding of what was being assessed and how the system was designed to work. Finally actions also emphasised the need to make sure that all of the managers had a common view of the system and could apply it evenly across their workforce.

Table 2.3 below highlights some possible actions identified by the five MAs participating in this pilot project, and their stakeholders, to address the challenge of employee engagement.

Table 2.3. Sample Action Table: employee engagement

|

Goals/sub-goals |

Identified potential actions |

|---|---|

|

An engaged and motivated workforce Senior management able to access and use data to inform change |

✓ Greater data-gathering through periodic employee engagement surveys |

|

✓ More strategic use of induction sessions for new staff |

|

|

✓ Review performance management system |

References

[4] Agenzia per la Coesione Territoriale (2019), Piani di rafforzamento amministrativo (PRA): Rete dei responsabili PRA presentazione Buone pratiche, http://www.pra.gov.it/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Slide-Riunione_BP-PRA_25.01.2019.pdf.

[7] Agenzia per la coesione Territoriale (2019), Relazione sulla progettazione, programmazione e realizzazione del percorso formativo manageriale denominato ’Gestione e svilippo delle risorse umane’, http://www.pra.gov.it/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/2019.09.05_Relazione-best-practice-corso-manageriale.pdf.

[16] Allen, N. and J. Meyer (1990), “The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization”, Journal of Occupational Psychology, Vol. 63/1, pp. 1-18, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1990.tb00506.x.

[14] Bakker, A. (2011), An evidence-based model of work engagement, https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0963721411414534.

[10] Centro di Competenza per la Pubblica Amministrazione (2019), Centro di Competenza per la Pubblica Amministrazione, Official website, https://compa.fvg.it/ (accessed on 28 August 2019).

[2] European Commission (2016), Delivery system final report - work package 12: ex-post evaluation of Cohesion Policy programmes, https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docgener/evaluation/pdf/expost2013/wp12_final_report.pdf.

[8] European Commission (2016), EU Competency Framework for the management and implementation of the ERDF and the Cohesion Fund, https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docgener/studies/pdf/comp_fw/eu_comp_fw_report_en.pdf.

[5] Gallup (2016), How Millenials Want to Work and Live, https://www.gallup.com/workplace/238073/millennials-work-live.aspx.

[18] Government of the United Kingdom (2015), Engagement and Wellbeing: Civil Service Success Stories, https://coanalysis.blog.gov.uk/2015/07/08/engagement-and-wellbeing-civil-service-success-stories/ (accessed on 28 August 2019).

[11] Macleod, D. and N. Clarke (2009), Engaging for Success: Enhancing performance through employee engagement, https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/1810/1/file52215.pdf.

[6] Metsma, M. (2014), The impact of cutback management on civil srvice training: the case of Estonia, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266373673_The_Impact_of_Cutback_Management_on_Civil-Service_Training_The_Case_of_Estonia.

[1] OECD (2019), OECD Recommendation on Public Service Leadership and Capability, OECD Publishing, https://www.oecd.org/gov/pem/recommendation-public-service-leadership-and-capability-2019.pdf.

[3] OECD (2017), Skills for a High Performing Civil Service, OECD Publishing, http://dx.doi.org/0.1787/9789264280724-en.

[9] OECD (2016), Public Procurement Training for Bulgaria: Needs and Priorities, OECD Publishing, https://www.oecd.org/gov/public-procurement/publications/public-procurement-training-bulgaria_EN.pdf.

[12] Rich, B., J. Lepine and E. Crawford (2010), ob Engagement: Antecedents and Effects on Job Performance, http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2010.51468988.

[13] Salanova, M. and W. Schaufeli (2008), A cross-national study of work engagement as a mediator between, https://www.wilmarschaufeli.nl/publications/Schaufeli/287.pdf.

[17] Schaufeli, W. et al. (2002), “The Measurement Of Engagement And Burnout: A Two Sample Confirmatory Factor Analytic Approach”, Journal of Happiness Studies, Vol. 3/1, pp. 71-92.

[15] Sonnentag, S., C. Binnewies and E. Mojza (2010), Staying well and engaged when demands are high: the role of psychological detachment, http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0020032.