For governments to optimise their investment potential, it is important that they engage in strategic planning that is tailored, result-oriented, realistic, forward-looking and coherent with development objectives at different levels. This chapter identifies that there is room for Managing Authorities to take a more strategic approach to Operational Programme planning, programming and priority setting. They also need to optimise coordination for programme design and implementation, address information gaps, improve knowledge sharing and expand communication. Building beneficiary capacity is another common challenge to be addressed, as well as engaging with external stakeholders. The chapter also identifies that Managing Authorities should render the programme implementation processes more strategic, and expand performance measurement practices to better support outcome evaluations.

Strengthening Governance of EU Funds under Cohesion Policy

Chapter 4. Generating a more strategic investment cycle among Managing Authorities

Abstract

Introduction

Strategic frameworks, planning and processes drive investment throughout the investment cycle, providing investment initiatives with an anchor into larger development objectives. For governments to optimise their investment potential it is important that they engage in strategic planning that is tailored, result-oriented, realistic, forward-looking and coherent with development objectives at different levels (OECD, 2013[1]). This is just as true for Managing Authorities (MAs) wishing to effectively manage and implement their Operational Programmes (OPs) as it is for other public sector bodies, as well as the private sector. Poor strategic planning, especially the lack of a long-term strategy at the central level, is considered among largest obstacles to ensuring effective public investment, particularly among European Union (EU) subnational governments (OECD-CoR, 2016[2]) (Box 4.1). The lack of long-term strategic planning capacity is also deemed a challenge by subnational EU governments, and a lack of adequate own expertise to design projects represents an important bottleneck in their ability to undertake infrastructure investments, specifically (OECD-CoR, 2016[2]).

Box 4.1. OECD-CoR survey: Identified challenges in the strategic planning and implementation of infrastructure investment in EU countries

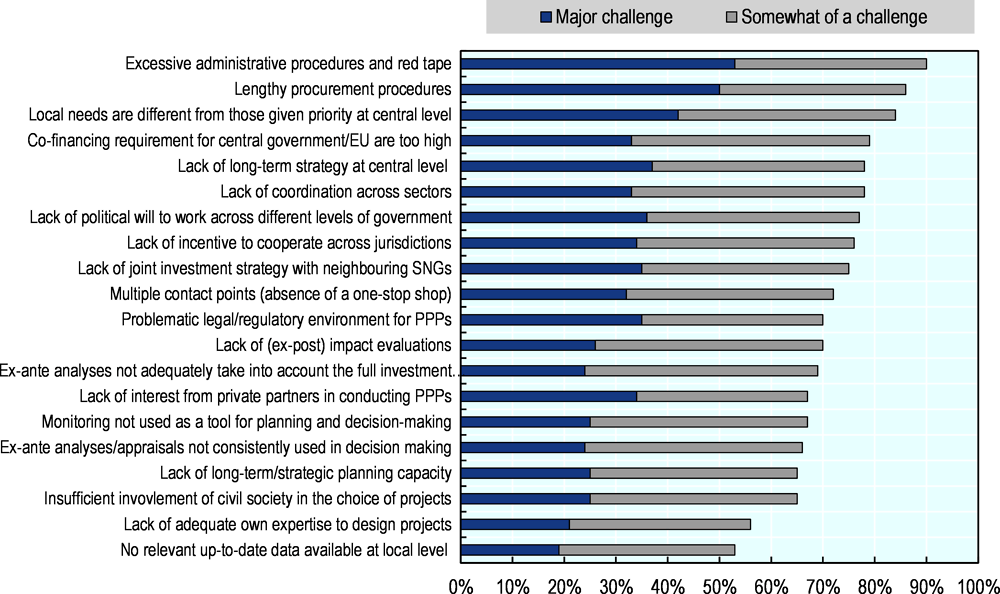

Between March and July 2015, the OECD and the European Union (EU) Committee of the Regions (CoR) conducted a survey of subnational governments in the EU to assess the challenges linked to infrastructure investment. A total of 295 respondents from all EU countries (except Luxembourg) participated in the survey.

The survey’s results show that governance challenges for infrastructure investment are prominent at the subnational level, essentially at the planning stage. At the core of planning, three quarters of respondents identified a lack of co-ordination across sectors, levels of government and jurisdictions as a top challenge. A large majority of respondents (90%) considered excessive administrative procedures and lengthy procurement to be a challenge. Sixty-six percent considered that a monitoring system exists, but that monitoring is pursued as an administrative exercise and not used as a tool for strategic planning and decision-making (Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1. Identified challenges in the strategic planning and implementation of infrastructure investment

While the CoR survey results cited above focused on the investment capacity of subnational governments, the findings are relevant for the MAs and European Structural and Investment Fund (ESIF) management for two reasons. First, there are MAs throughout the EU that operate at a regional level as regional MAs (e.g. in Germany, Greece, Italy, Poland and Spain) and thus invest at the subnational level. Second, and potentially more importantly, ESIF beneficiaries – especially for European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), which accounts for the bulk of the allocated financing – include subnational governments (either regional or local authorities) who must design and implement investment projects to be supported by these funds.

This pilot action highlights that despite contextual and structural differences, in the context of the administrative capacity for ESIF management, MAs appear to face a series of common strategy challenges. These challenges include ensuring a strategic approach to OP programming and implementation, and identifying the priorities that can best support achieving national and local development aims. Striking a balance between top-down and bottom-up input to OP design and implementation can also be challenging, as is building effective information flows and knowledge-sharing mechanisms, and ensuring that operational practices are optimised. Much of this requires refining exiting coordination mechanisms, which in broad terms are firmly in place. Equally important, more could be done to ensure that beneficiaries and other stakeholders are engaged and capacitated, and that performance measurement practices are more strategic, less cumbersome and contribute evidence bases for the development of future Partnership Agreements (PAs) and the OPs that support them. In the forthcoming programming period, these challenges may become accentuated among MAs that move to a greater delegation of functions to regional levels, unless mechanisms are in place to manage them at all levels of OP implementation.

Taking a more strategic approach to OP planning, programming and priority setting

The capacity of national and subnational institutions to design effective strategies, allocate appropriate resources and efficiently administer EU funds can have a positive incidence on the contribution of Cohesion Policy to the economic development of a territory (Bachtler, Mendez and Oraže, 2014[3]). While not the case for all MAs, in those instances where the links between higher-level strategic documents (e.g. national or regional development plans, sectoral development strategies, etc.) are weak, unclear or missing, the result is greater difficulty in seeing the “big picture” and a tendency to get entwined in the technical details and immediate needs of specific projects and OP implementation. Making sure the links between different levels of strategic documents are clear to staff can help better support their capacity to make decisions and undertake day-to-day activities that advance operations. Often, strategic gaps can be seen in project selection and appraisal, as well as in the monitoring and evaluation of OPs. For example, project appraisal indicators or the way MAs monitor the programme progress tends to ensure the degree of “formality” but not necessarily evaluate strategic impact (i.e. outcomes), be it of an individual project or the OP as a whole. Weak strategic underpinnings for OP implementation can lead an MA to focus primarily on the short-term (e.g. rapid absorption) and on technicalities. This can manifest by using the funds in ways that align most closely with past use (limiting the risk of non-compliance with technical guidelines), rather than taking a longer-term strategic approach and promoting investments that may be slightly more innovative (though may require more support to ensure compliance) and which may contribute more effectively to meeting national and regional development objectives.

Several obstacles impede a more strategic approach to OP planning, programming and priority setting among MAs. Among the pilot project MAs, in a few cases, a high-level strategic framework was not in place to guide the OP design and implementation. More commonly however, there appears to be a limited ability – or potentially limited opportunity – to capitalise on the complementarities and synergies among the different projects, programmes, or Priority Axes forming an OP, thereby affecting the MA’s capacity to optimise existing resources. MAs can also face difficulties in setting priorities that reflect national and subnational development needs and align with the implementation capacity of beneficiaries.

Clear links to higher-level strategic frameworks can support strategic planning for OP investment

A strategic guideline for investment, often a higher-level strategic framework, can serve as an anchor and offer a long-term vision for development with clear objectives and development priorities. For ESIF, this strategic guideline is embodied in the PA between the European Commission and EU Member States, with OPs being the means to implement the strategy. PAs and OPs are frequently developed in parallel. An EU study indicates this to be the case about 60% of the time for Cohesion Policy OPs (EC-DG REGIO, 2016[4]). While it was frequently the PA that provided the strategic framework for OPs, thereby facilitating the ability to establish a clear hierarchy between the two frameworks, in the case of European Social Fund (ESF) particularly, strategic issues were often first decided through the OP (European Commission, 2016[5]). The reasons behind this may include a need to respond quickly to planning requests, as well as limited experience working within the Cohesion Policy and ESIF structures (particularly in the case of newer EU Member States).

At a national level, a clearly articulated long-term investment strategy, be it for overall development or for a specific sector, can help align priorities between the OP and national level objectives. Higher-level national strategies and an OP are mutually supportive. This is particularly important as an OP is, itself, not a strategic guideline for investment. Rather it depends on already established strategic guidelines to clarify long-term investment objectives, and guide the prioritisation of projects by sector, programme and level of government.

Ultimately, higher-level strategic frameworks offer MAs a clear path to follow or refer back to throughout the OP implementation. Even though in the current 2014-2020 cycle a clear and better linkage to EU 2020 goals as well as own national strategies was a conditionality for allocating ESIF funds, a lack of strategic guidance, and limited ability to go beyond the technical details was an often mentioned problem among pilot MAs. Despite links between ESIF allocations and the EU2020 strategy as well as other EU or national goals established in PAs, these may not be sufficiently evident and/or do not help guide the actions and operations of implementing staff.

Specifically with respect to national- or regional-level development strategies, these can help ensure that OP design and implementation takes a place-based rather than spatially-blind approach, potentially maximising the contribution of an OP to the growth potential of a specific territory. This is particularly important for regional MAs and Regional Operational Programmes (ROPs). ROP programming ideally should reflect territorial specificities, be aligned to regional development needs, and be adapted to different local contexts, such as the degree of subnational autonomy, market conditions, or institutional or beneficiary capacities. For example, national MAs can provide tailored support to regional MAs to improve their OP or ROP implementation capacities in cases where there is a misalignment between OP objectives and regional “market” realities. In addition, development strategies serve as additional guidance for ensuring that the OPs/ROPs help regional actors meet broader development and investment goals. For example, in 2011-2012, Poland introduced the Long Term National Development Strategy: Poland 2030: The Third Wave of Modernity. Before that, Poland put in place the Medium Term National Development Strategy (MTNDS), setting out strategic development objectives for the country from 2010 to 2020, and identifying key development activities, including those that could be supported by EU funds in the 2014-2020 period. Nine integrated strategies, including the National Strategy for Regional Development 2010-2020, were also developed under the MTNDS, aiming to assist the achievement of the development objectives (Polish Minstry of Economic Development, 2017[6]). Similarly, the Czech Republic is creating a National Investment Plan covering the period up to 2030, which aims to be financed by the state budget, ESIF resources, and private investors, among others. The Plan includes a long-term fiscal framework and, having gathered information on local needs, targets transport, energy and other infrastructure as primary national investment priorities based on identified local needs (OECD, 2019[7]).

Just as important as ensuring links between higher level strategies and OPs, is ensuring that MAs have input into their OP’s design at the very early stages. An OECD study on the governance of infrastructure investment highlights that, in many countries, consultation with stakeholders tends to take place in the investment preparation phase but is less common in setting an overall vision, prioritising investments or assessing needs (OECD, 2017[8]). Responsibility for preparing the various framework documents that provide strategic guidance to OPs, be they national or sector strategies, or the country’s Partnership Agreement with the EU, rests with the national authorities and line ministries. MAs are implementing agents who work under determined structures and framework conditions. Yet they have expertise and knowledge that is valuable for not only OP implementation, but for future programming as well. Thus, if they are not responsible for designing or structuring their OP, bringing their perspective into the early discussion phase is part of the strategic planning component of the investment cycle. Doing so helps responsible authorities tap into an MA’s experience with OP implementation and their understanding of beneficiary needs, as well as what may or may not work. This, in turn, helps better align the OPs with sectoral and regional investment needs and specificities, and maximise coherence among policies and programmes. It can also help MAs identify, early on, where the synergies and complementarities lie within their OP to effective design Priority Axes programming in a way that harnesses these ex ante, rather than trying to accomplish the task ex post.

Setting OP investment priorities that reflect national and regional development needs

Strategic priority setting can be complex and require a sophisticated approach to balance different factors. It is, however, fundamental in order to focus programme implementation and avoid wasting resources on secondary issues, thereby supporting more effective and efficient absorption of ESIF. MAs must take into consideration the higher-level priorities established in the PA, as well as national and often regional priorities for development and their capacity (including resources) to invest. Balancing these various factors can be tricky. In a case study of Scotland’s European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and the European Social Fund (ESF) OPs (2014-2020), stakeholders stated that one of the challenges affecting policy efficiency and additionality was the discrepancy between the priorities set conceptually and strategically (e.g. a focus on research and development investment as part of the ‘smart growth’ agenda) and the availability of local match funding, as well as the match funding to be ensured by third sector organisations, to actually develop and deliver projects in specific areas (Dozhdeva, Mendez and Bachtler, 2018[9]). Investment priorities can also be influenced by different actors (e.g. government agencies, ministries etc.), whose objectives are supported by OP spending. This adds additional complexity to the MA’s work when considering which investments may most effectively respond to national and subnational needs and aims. Balancing technical requirements established by the EU (e.g. eligible costs, ring-fencing, mid-term review based on performance framework, etc.) and strategic considerations associated with investment needs and capacity – be they national, sectoral or regional – is an intricate task for the MAs when setting priorities. In addition, care needs to be taken that priority-setting is not driven by the inertia of out-of-date plans, prior assumptions, or narrow political considerations (OECD, 2013[1]).

The importance of a multi-stakeholder or “partnership” approach to investment planning processes cannot be emphasised enough. Strong top-down processes in priority setting can weaken OP implementation by limiting stakeholder input and the ability to take into consideration the needs and capacities of beneficiaries, be they regional or local authorities, the private sector, civil society or others. There is evidence indicating that strategies combining top-down with bottom-up approaches are among the most effective (Crescenzi and Giua, 2016[10]). This pilot illustrated that top-down approaches could originate at a national level or at the MA level vis-à-vis beneficiaries. This was illustrated by instances where priorities are established at a central level based on the impact they are expected to achieve regionally; and instances where the contribution to priority identification and setting by subnational-government beneficiaries is limited. Regardless of where a top-down approach originates, bringing OP stakeholders into the process of defining and validating priorities (and investment needs) can help ensure priority robustness, add to evidence bases, and increase the potential for project take up when calls are made. Setting priorities, and acting on them effectively, requires fruitful co-ordination and communication within the MA and between the MA and other ESIF stakeholders, including regional governments (where applicable), the national government and the European Commission, as well as Intermediate Bodies (IBs), regional and local authorities and beneficiaries. This can help ensure that subnational specificities, beneficiary capacities and overall investment needs are further integrated into the process, thereby facilitating more effective OP implementation. It can also generate greater trust by lending a greater degree of transparency to the whole OP investment process – a process that may be considered opaque, particularly by private sector beneficiaries. For example, in London, the London Economic Action Partnership brings together entrepreneurs, businesses, the Mayoralty and the London Council in order to identify investment priorities and strategic actions of ESIF programmes to support job creation and economic growth in the capital. A Committee is also set up within this Partnership to oversee the ESIF programmes and ensure that they meet the strategic priorities of London (ECORYS, n.d.[11]).

Capturing complementarities and synergies across and within OPs

OPs are all, or almost all, composite structures, formed by a number of different Priority Axes. With composite structures, bringing together the various relevant sectors involved to contribute input into programme and project design and/or implementation can improve capacity to identify and capitalise on cross-sector synergies and strengthen strategic complementarities. While most Priority Axes and related programmes can benefit from cross-sector input, their design, priorities and associated projects can often and easily be organised by line ministries working vertically within their sectors, or central authorities responsible for ESIF programming. Many countries commonly apply this sector-oriented approach to infrastructure investment. In an OECD survey of infrastructure governance, 12 out of 27 respondents stated that infrastructure development was linked to sectoral plans and generally not developed in an integrated (i.e. cross-sector) fashion (OECD, 2017[8]). There is nothing inherently wrong in this, as sector strategies are very helpful, especially for sector driven MAs (e.g. MAs responsible for environment, transport, energy, education, etc.). However, its effectiveness also rests with cross-sector consultation and coordinated, mutually-reinforcing programming. Not doing so may accentuate a fragmented implementation approach where the priorities of individual ministries or relevant institutional bodies compete rather than complement each other, limiting the ability of MAs to achieve OP objectives in a strategic manner.

However, sectoral actors, including line ministries, often lack mechanisms and incentives to identify and capitalise on synergies and complementarities, or such mechanisms and incentives are not institutionalised, or they are insufficient. Introducing a horizontal or integrated approach when programming is designed and/or implemented by bringing together various sectors, can rapidly help identify and capitalise on complementarities or synergies, and national coordination bodies can play an important role in this regard. In Spain, for example, the public policy thematic network “Red de Políticas de I+D+I” focusing on R&D and innovation was established to exchange information on Cohesion Policy implementation across the country and promote the coordinated use of the Structural Funds with other policies, including coordination among different government levels. In the 2014-2020 period, the role of this network was formally included in the Partnership Agreement as well as in national and regional OPs (European Parliament - DG Internal Policies, 2016[12]). In the current programming period, the European Commission has introduced some new features and instruments aiming to reinforce an integrated territorial approach to ESIF. These include Integrated Sustainable Urban Development (ISUD), Integrated Territorial Investment (ITI) (a tool to achieve ISUD) (Box 4.2), and Community Led Local Development (CLLD) financed by the Structural and the Rural Development Funds. These instruments permit combining resources from different funds. Thus, they are highly multi-sector and require strong coordination across the whole investment cycle.

Box 4.2. Integrated Territorial Investment (ITI) as a tool for promoting cross-jurisdiction cooperation

Integrated Territorial Investments (ITIs) offer one way to manage subnational (local) fragmentation and build scale for potentially greater returns on ESIF investment. ITIs allow Member States to implement OPs in a cross-cutting way and to draw on funds from several Priority Axes of one or more OPs, helping promote the implementation of an integrated strategy for a specific territory. They are one of the tools introduced to implement the Integrated Sustainable Urban Development (ISUD) initiative, a compulsory feature of ESIF 2014-2020, which requires a commitment of a minimum of 5% of ERDF resources.

ITIs are currently used in 20 EU Member States. They are not compulsory and there is no extra financial incentive provided to encourage their use in this programming period. MAs in this pilot project indicate that ITIs have the possibility of being a very powerful instrument for co-ordinated investments between different Thematic Objectives, funding streams, priorities and programmes. In most cases, ITIs are used for large infrastructure investments that draw from ERDF and involve cross-jurisdiction cooperation. In spite of the potential benefits of ITIs, the uptake is limited for a number of reasons, including: limitations in national laws (e.g. with respect to creating joint municipal bodies or associations), complex implementation arrangements precisely due to legal obstacles, and limited capacity (at the local and/or MA levels). For example, while ITIs are often used in cross-jurisdictional co-operation investment, in some EU Member States, national legislation does not recognise the legal status of cooperative agreement among municipalities.

With respect to capacity, this includes the capacity to introduce and implement ITIs, and the ability to encourage their use. For example, local authorities often need to work together on designing and implementing an investment project, particularly ITIs. Thus, enhancing the capacity of MAs to promote effective cross-jurisdictional co-operation and co-ordination for public investment becomes essential. Starting the preparation of ITIs early in the programming cycle, and clearly identifying objectives and potential programmes to support these, can be valuable, as was the case of the Netherlands, where Dutch cities started to prepare ITIs and had discussions with the European Commission in 2012, two-years ahead of the 2014-2020 programming period.

Additional challenges associated with ITI use include establishing a coherent framework by which the mechanism can help address a variety of territorial challenges, reconciling territorial and sector polices, and ensuring solid territorial development strategies. While ITI use has been limited in the 2014-2020 programming period, mid-term evaluations were encouraging, and it is expected that in the 2021-2027 period there will be a greater reliance on ITIs.

Ideally, building on complementarities and synergies should take place across OPs with the support of central units responsible for coordinating ESIF programming. Barring this, at the outset of a programming period individual MAs could identify the complementarities or synergies that they wish to emphasise within their OPs and build on these through programming, project selection and evaluation mechanisms, and incentive structures. For example, more integrated outcome indicators can be introduced in the monitoring of projects, Priority Axes and programmes, beyond the sectoral output and impact indicators. This is particularly true for Priority Axes that are highly multi-sectoral and integrated. Incentives and rewards (e.g. bonus points) could be introduced to project selection and call process for projects that can contribute to meeting objectives in more than one programme area or sector. This can help create links between Priority Axes, especially those may have difficulty attracting projects. The Welsh Government has developed the Economic Prioritisation Framework (EPF) that highlights existing assets and investments in both thematic and spatial areas. It illustrates a broader investment context so that EU projects are not designed in isolation, and helps make sure each EU funding proposal adds something new and valuable to existing investment. Ultimately, the EPF helps identify potential links among projects, encourage collaboration, and avoid duplication (Welsh Government, 2018[17]; Welsh European Funding Office, 2019, unpublished[18]).

Table 4.1 below highlights some possible actions identified by the five MAs participating in this pilot project, and their stakeholders, to address the challenge of taking a more strategic approach to OP planning, programming and priority setting.

Table 4.1. Sample Action Table: taking a more strategic approach to OP implementation

|

Goals/sub-goals |

Identified Potential Actions |

|---|---|

|

Establish clear links to higher-level strategic frameworks Set OP priorities that reflect national and regional development needs Capture complementarities and synergies across the OP and Priority Axes |

✓ Undertake a strategic evaluation of the OP’s Priority Axes, including typology of projects and budget allocation, to identify the synergies that could contribute to greater territorial development, especially among Priority Axes with low absorption rates. |

|

✓ Design and pilot, and evaluate a project selection process, with incentives, that requires cross-sector inputs under one or two Priority Axes or additional incentives for specific integrated projects and programmes. |

|

|

✓ Launch a pilot action (or experiment) to test mechanisms encouraging programmes and projects that build and promote complementarities and synergies across OPs |

|

|

✓ Experiment with identifying and structuring incentives for inter-municipal/cross-jurisdiction cooperation, and build pilot results into next period. |

|

|

✓ Develop trainings for MA, and IB officials on strategic planning, policy development, and strategic operational issues to support the programming, building on work and activities of other departments. Reinforce the learning by organising small team discussions on strategic planning and programming for the OP (particularly helpful for new staff). |

|

|

✓ Develop a modular series of educational seminars or hands-on workshops for beneficiaries, in strategic planning, priority setting, EU funding mechanisms, investment budgeting, project design and application requirements, etc. |

Optimising coordination for OP design and implementation

Effective coordination among public investment actors – in this case among MA units, between the MA and its diverse stakeholders (e.g. IBs and beneficiaries), and among different government actors participating in the investment process (e.g. line ministries, subnational governments) – is fundamental to optimising public investment outcomes (OECD, 2014[19]). It is the first pillar in the OECD Recommendation for more Effective Public Investment across Levels of Government, and a lack of coordination across sectors was identified as a challenge in the 2016 OECD/CoR survey highlighted in Box 4.1. A number of factors can affect coordination capacity. For example, cross-sector coordination can be stymied by a lack of political will or an administrative culture unaccustomed to working cooperatively across sectors or among different levels of government (OECD-CoR, 2016[20]). The lack of coordination among sectoral and territorial approaches, policies and programmes is a long standing problem in many countries, and affects ESIF management. Such a situation can arise if the coordinating ministry is deemed weak by line ministries who subsequently resist coordination efforts, or when the mix of instruments and programmes or calls lead to perverse or split incentives (Kalman, 2002[21]). It can also lead to a duplication of tasks and confusion in the system (Bachtler, Mendez and Oraže, 2014[3]). MAs with complex administrative structures can also find it challenging to ensure effective coordination arrangements between the MA, relevant ministries, IBs, beneficiaries and other relevant bodies in the OP implementation system.

Ensuring sufficient coordination in the OP implementation process by actively establishing partnerships among actors at different levels of government is key. This can help reduce information asymmetries and ensure the alignment of strategic priorities for the OP. Looking ahead, it promises to increase in importance among those countries that promote more integrated investment models, such as ITIs. Overall, coordination was not identified by the pilot MAs to be a significant challenge to administrative capacity and OP implementation. However, several points were underscored.

Striking a balance between “hard” and “soft” coordination mechanisms

First, “hard” coordination mechanisms1, such as rules, regulations, standards, and formal agreements (e.g. PAs between individual EU Member States and the EC) are used to manage MAs, and used by MAs to manage OP implementation, structuring project selection and call processes, control and verification processes, etc. If poorly designed, unclear or improperly implemented, these can present practical challenges, such as excessive administrative burden (see Chapter 5), but are generally accepted as part of the process.

Second, “softer” mechanisms, including strategies, plans, and dialogue mechanisms, are easier for MAs to create and/or to use, and there appears to be a preference for dialogue mechanisms. Informal dialogue mechanisms include ad hoc meetings and informal exchanges – a format many MAs, particularly those in smaller countries, rely on. Informal dialogue is also valued by MAs in their relationship with the EC. A 2016 study2 highlights that 85% of respondents (comprised of MAs and other stakeholders) agreed that informal dialogue between EU Member States and the EC is useful for programming issues, for example in terms understanding new requirements, while also granting the opportunity to give relevant feedback. In the end, this can contribute to better adherence (EC-DG REGIO, 2016[4]). Clear and regular communication and information exchange with the EC can also help minimise the impact of over- and unclear regulation, as well as ensure synchronisation in the work and agreements for the next programming period.

Formal dialogue mechanisms include stakeholder dialogue fora, thematic networks, committees, working groups, and communities of practice, for example. Effective exchanges between national government, MAs, regional MAs, and beneficiary local authorities, are particularly important in order to ensure that national strategies are sensitive to, or make room for, regional MAs to tailor regional-level interventions and investments to respond to local needs. Ensuring that the outcomes of these exchanges are integrated into the knowledge base and capacities of beneficiaries could be valuable for strengthening the partnership between the national and regional MAs and their beneficiary base.

Another popular dialogue-based coordination mechanism is thematic networks and working groups composed of MA and IB representatives, such as those established for procurement, state aid, anti-fraud, publicity, and evaluation, as well as inter-ministerial bodies focused on accelerating project implementation. These dialogue mechanisms bring participants up-to-date on challenges, issues and new requirements, as well as offer an opportunity to network, exchange experiences, and seek advice from peers and others. They are frequently used and generally highly valued by MA staff and stakeholders.

It is important to manage and, ideally, avoid dialogue fatigue, a fact also acknowledged by members of different MAs. While dialogue mechanisms are favoured by MAs, staff members highlight the number of meetings, working groups, committees and subcommittees for ESIF coordination and monitoring, etc. in which many of them already participate. They not only warned about spreading already limited human resources more thinly but also about duplicating effort. They also emphasised that not all such bodies are timely, regular or effective. Thus, often the need is not for a new dialogue body, but to use those that exist in ways that might better advance an MA’s coordination needs. This could mean expanding mandates or activities or adjusting agendas, for example. To manage dialogue fatigue is it is essential to be clear as to why the dialogue is being established before establishing it, the objectives for the dialogue, its expected results and next steps for action if relevant. It is also useful to identify and communicate beforehand if the dialogue mechanism is temporary and established for a specific purpose, or if it will be considered permanent. Rationalising existing dialogue bodies may occasionally be necessary, as well. Finally, it is important to avoid getting “stuck in the dialogue” – talking and meeting rather than using the dialogue mechanism as a tool to advance action (e.g. identifying priorities, discussing common problems or risks, establishing practical solutions, etc.) in a coordinated manner.

Third, there is room to strengthen stakeholder dialogue among actors within the Management and Control System (MCS), and to establish dialogue among a country’s different MAs, as well as IBs in many cases. In Spain, for example, the Economic and Regional Policy Forum brings together national and regional MA and IB authorities to discuss ESIF management. As an expert network it provides space for knowledge sharing on challenges, issues, and new requirements or regulations, while also offering participants an opportunity to seek advice and exchange experiences. These can be more thematic and concentrate on certain areas, e.g. procurement, ex ante project evaluation, etc. Such networks could also reinforce MA/IB coordination and collaboration, especially with respect to identifying and discussing real and potential programming and technical project problems, finding realistic solutions.

There is also significant room to expand dialogue with external stakeholders, especially beneficiaries, but also subnational government authorities, the consultants that support beneficiaries, associations of local authorities, private sector representatives such as chambers of commerce or trade associations, etc., which is explored in the section on stakeholder engagement.

Reinforcing coordination between national and subnational level authorities

Effective coordination mechanisms between national and regional levels need to be established early on, ideally in the OP design phase but also in the programming and implementation phases. These can be a driving factor behind successful OPs and ROPs and investment results, particularly since subnational level authorities are most knowledgeable about regional specificities, investment needs and beneficiary capacities. In addition, they are well placed to identify overlaps and synergies between national and regional programming ex ante to ensure that actions are mutually supportive and build on each other. Late identification of overlap in objectives, project types and possible beneficiaries during the launch of programmes and project calls can lead to disputes in jurisdiction, responsibilities and beneficiaries, causing complications and delays. In regions with a smaller pool of potential beneficiaries, a lack of vertical coordination can result in a form of competition for funds offered by the region and those by other national programmes. Undertaking a joint national/regional analysis exercise could be useful to identify areas of potential programming complementarities and overlap. The results could be used to collaboratively establish programming that pursues complementary development objectives, limits (and ideally avoids) national/regional overlaps, and fills in programming gaps. “Hard” mechanisms, such as national-level requirements for distributing and using EU funds in regional public investment projects is one technique to ensure that ROPs are consistent with central priorities. An OECD case study on Wielkopolska, Poland reveals that local authority investment projects may be financed using EU funds on the condition that they contribute to the implementation of a multi-annual development strategy. The study highlights that, generally speaking, there is a positive impact on regional programme effectiveness and the sustainability of project financing when there is room for subnational governments to negotiate and influence conditions set by the national level. This experience suggests that conditions around which the two levels agree may work better than those imposed by one side or the other (OECD, 2013[22]). In addition, coordination with regional MAs or IBs may be insufficient among some MAs, due at least in part to administrative obstacles embedded in a bureaucratic approach to dialogue and information exchange. In such cases, the high transaction costs for staff at the regional or local level to be in touch with MA officers inhibits more effective coordination.

Table 4.2 below highlights some possible actions identified by the five MAs participating in this pilot project, and their stakeholders, to address the challenge of Optimising coordination for OP design and implementation.

Table 4.2. Sample Action Table: optimising coordination for OP design and implementation

|

Goals/Sub-goals |

Identified Potential Actions |

|---|---|

|

Making the most of existing coordination mechanisms Optimising coordination between MAs and IBs |

✓ Establish or improve active and dynamic dialogue among OP stakeholders to identify strengths, risks, challenges, and implementation problems early on and to develop innovative, joint solutions, with an eye on building beneficiary capacity and reducing delays. |

|

✓ Organize a network or working group of expert technical officials across and within MAs and IBs to identify problems and develop collective solutions regarding OP implementation, exchange information, experiences, and build the overall knowledge base. (This can be done within one MA and its IBs, or among MAs in one country). |

|

|

✓ In consultation with IBs, strengthen the monitoring and feedback mechanism between the MA and the IBs and beneficiaries, with the aim of boosting IB ability to respond to problems in a timely manner and building ownership for results. |

|

|

✓ Ensure regular meetings across the Management and Control System with clear agendas and establish platforms for easy communication and knowledge sharing in general and on thematic issues. |

|

|

✓ Implement annual technical meetings with IBs to identify potential project problems, discuss necessary adjustments and to collaboratively develop solutions; exchange information experiences on specific projects or project types (e.g. environment); develop an advisory and consultative mechanism to identify and solve problems early on |

Addressing information gaps, improving knowledge sharing and expanding communication

ESIF investment relies on effective information flows and knowledge sharing among multiple stakeholders at all levels of government, and beyond. Without good and timely communication among those responsible for OP implementation, large biases and information asymmetries may arise. To address this, building a stronger bottom-up approach to information and knowledge sharing as well as more targeted communications throughout the OP implementation system can be helpful. Good practices to manage information and knowledge gaps include those that create channels for clear and efficient information flows, as well as constant and regular knowledge sharing, be it among the different departments and units in an MA, between an MA and other bodies and authorities in the MCS, with other national and regional MAs in the country or abroad, or with beneficiaries and citizens. Currently, many MAs have participated in various networks to promote professional exchange on OP implementation processes (e.g. public procurement, evaluation, anti-fraud, risk management, etc.), which are deemed helpful for information exchange. This type of information and knowledge sharing could be furthered reinforced through regular opportunities and platforms for exchange across MAs in the EU. At the same time, it is important ensure the inclusiveness of these networks (i.e. the participation of operational-level staff and beneficiaries) and that the exchange outcomes contribute to the knowledge base for more effective OP management.

This pilot action highlighted that there is room for MAs to improve information flows and exchange throughout their OP programming and implementation system – generally by fostering greater consistency and fluidity of exchange, as well as ensuring that it is more timely and appropriately targeted. At the project implementation level, information gaps may lead to lower efficiency and effectiveness of OP implementation. For example, diverse stakeholders, and particularly beneficiaries, indicate information accessibility issues regarding the spectrum of support and funds available. Information on pros and cons, benefits and costs of using ESIF funds can be better clarified to beneficiaries, certainly for grants but especially for other, innovative financial instruments. In addition, introducing regular opportunities for two-way communication with IBs and beneficiaries regarding changes in regulations, processes or programmes might be helpful and contribute to reducing delays by enhancing capacity, especially at the beneficiary level. Ensuring regular and well-structured exchange with beneficiaries could offer additional insight into investment needs and the actual beneficiary capacity. This could help an MA better tap into the “on the ground” knowledge of beneficiaries, thereby supporting more effective OP design, monitoring, and implementation, while also building subnational capacity.

Information flows and knowledge sharing within the MA and throughout the MCS

Ensuring effective and smooth, clear and simple information flows within an MA as well as throughout the system (MA, IBs, beneficiaries, etc.) is part of effective OP implementation. Limited and/or irregular use of mechanisms to disseminate up-to-date information and knowledge is one obstacle to ensuring that relevant or new information is shared throughout the MA, or between MAs and other actors in the system. This can be particularly true with respect to two-way communication in hierarchical, top-down, or centralised administrative cultures. Within MAs, opportunities for different departments to meet, both at the department head and technical levels, can help keep information flowing across teams, and build institutional knowledge across sectors and activities. They also support a more transparent and accountable environment. Ensuring that such meetings happen on a formalised and regular basis (weekly, bi-monthly, monthly, etc.), with a clear agenda, free information exchange, articulated next steps or expectations, and responsibility for decision follow-up can smooth information flows and knowledge exchange throughout the OP investment process.

Easier information exchange and regular opportunities to exchange knowledge and good practices can also help actors involved in OP implementation share problems and jointly identify solutions. In Bulgaria, the Council of Ministers organises regular meetings among all Bulgarian MAs at which problems are discussed and solutions are sought. To optimise the impact of such meetings on OP implementation, including MA managers and technical experts in the discussion even if on an ad hoc basis, or at a minimum making sure the results of such meetings are received by staff involved in daily decision-making and execution is valuable. Effective two-way information exchange is also necessary. Embedding multi-directional (i.e. top-down, bottom-up, and across departments) knowledge-sharing mechanisms and practices throughout an MCS is one way to accomplish this. MAs can support such knowledge-sharing by establishing better two-way exchange with their IBs, beneficiaries and other stakeholders through periodic but regular interaction. Such interaction can help identify and mitigate possible administrative, operational or investment risks. It can offer insight into the impact of an OP, a Priority Axis or an individual project, thereby providing the MA with valuable insight on what might work well, and where adjustments may be needed to improve the OP implementation processes. It also facilitates dynamic feedback, helps create ownership among actors, and reinforces trust in institutions and processes.

Electronic tools and online sharing is an effective exchange channel not only for MA staff but also between an MA and other stakeholders. Information and knowledge exchange platforms for managerial and technical staff across MAs help improve information flows and promote greater knowledge sharing throughout the implementation system. For example, some MAs have established electronic systems (e.g. the Integrated Documents Management system in Greece) or internal online platforms (e.g. the European Structural and Investment Funds Information Portal in Bulgaria) where information on the OP is regularly updated and it can be accessed by all MAs. This helps streamline OP investment management and implementation procedures.

Communication with beneficiaries and citizens

The European Commission establishes communications requirements for ESIF implementation. This can include signage for projects or other ESIF-financed initiatives, webpages for the various funds, manuals, and training for beneficiaries on communications requirements, for example. This is all very valuable for increasing the visibility of funds. What appears to be missing however, is an approach that actively communicates the benefit or value that the funds offer beneficiaries to realise their own goals, and to citizens more broadly. In other words, communication that can answer the “what is in it for me” question that can arise, especially when engaging with funds is or is perceived to be lengthy and burdensome, without guarantee (i.e. beneficiaries may respond to a call but are not guaranteed to receive funds through the call if their project is not selected), or risky (e.g. a need to secure co-financing, or the possibility of financial corrections). This is particularly important for non-government beneficiaries (i.e. the private sector, civil society organisations, academia, etc.).

To better communicate the value of an OP and its contribution to community needs, MAs could more frequently consider developing a communications strategy and a corresponding implementation plan that extends through the programming period and targets OP beneficiaries, as well as citizens. For beneficiaries, a contextualised communication strategy could include not only how to access funds but also the impact that an ESIF-funded initiative could have in terms of meeting their objectives according to their category of beneficiary (i.e. a local authority, a business etc.). It is important that the communication approach and message resonate with different types of beneficiaries (e.g. small versus large municipalities; urban versus non-urban centres; micro and small and medium enterprises (SMEs) versus large enterprises; private versus academic research facilities, etc.), use simple, every-day language and be disseminated through various forms of media (e.g. print, newsletters, social media, digital or online networks, etc.). Communication templates (including key messages, page layouts, simplified terminologies, visual supports, etc.) could be developed at the national level for adjustment at the local level according to need.

Consideration can also be given to tailoring such plans to communicate with citizens and potentially individual communities. This might be particularly useful in cases of large infrastructure investment, which can be disruptive and inconvenient for communities before the benefits are seen and appreciated. It would serve a dual purpose: first to explain the project and its objectives to community residents/citizens and second to highlight the role of EU funding in the project’s realisation. It can also provide citizens with insight into how projects implemented with EU funds work, what they have helped communities accomplish thus far, and what the MA and the local authority aim to achieve in the future with such programming. The development of a communication strategy should incorporate the opportunity for citizens to express their opinions and understanding of local investment needs, proposed project results, or EU funds in general. Surveys or public consultation events are a means to obtain such information. This is fundamental to help build trust in the process and serve as an accountability mechanism, particularly in those places where citizens are distrustful of co-financed interventions due to a lack of trust in legislation and a perception of favouritism in the award system. Citizen communication can be managed centrally, among MAs in the country, by an individual MA or can be developed in collaboration with individual communities to tailor messages specific to community interventions. Any communication however should use simple, every-day language and be disseminated through various forms of media (e.g. print, newsletters, social media, digital or online networks, etc.). It should also be managed strategically, for example through periodic analysis on comments and feedback from the public in order to adjust the communications plan as necessary. Such analysis can also highlight early-on where there may be dissatisfaction or disagreement with investment initiatives, and provide the implementing authorities with the opportunity to address citizen concerns, explaining why something may be necessary or, conversely why something cannot be done. This goes beyond the regulated communication programmes that each MA must have in place, and becomes a more strategic activity to build awareness of the role and importance of ESIF investment in the development and quality of life of a country, region, city, town, area, etc. In Portugal, authorities from different programmes associated with EU funds created a network of communicators and launched several ground-breaking campaigns, such as the “Have you heard of ... EU-funded project?”, disseminated by printing the question and name of the participating projects on five million sugar packets. These campaigns, coordinated across MAs, successfully helped increase the awareness of EU funding among the citizens from 29% in 2015 to 44% in 2018 (European Commission, 2018[23]).

Table 4.3 below highlights some possible actions identified by the five MAs participating in this pilot project, and their stakeholders, to address the challenge of addressing information gaps, improving knowledge sharing and expanding communication.

Table 4.3. Sample Action Table: addressing information gaps, improving knowledge sharing and expanding communication

|

Goals/Sub-goals |

Identified Potential Actions |

|---|---|

|

Improve information flows across the OP implementation system and within the MA Strengthen knowledge sharing within the MA and throughout the Management and Control System Enhance communication with beneficiaries and citizens |

✓ Establish regular cross-sector meetings between the relevant MA departments (and among department heads), as well as with IBs and other key stakeholders as necessary. Ensure meetings have clear agendas, next steps, and responsibilities for decisions taken. |

|

✓ Develop an information and communication strategy tailored to the OP and its beneficiaries, and implement a communications campaign that identifies and explains the full spectrum of support and funds available to beneficiaries and what they can gain from their use. Use clear, every-day language and target the message and communication challenges (i.e. newsletter, calendar, social media, networking events, surveys, etc.) according to beneficiary type. |

|

|

✓ Create information material for beneficiaries (in clear, easy to understand language) that articulates what the OP aims to achieve, its concrete objectives, how it can be of value to their communities, and how to access funds. Enhance the visibility of the OP’s objectives and successes to beneficiaries and the public, possibly via social media. |

Building beneficiary capacity

Beneficiaries are key stakeholders in the whole ESIF investment cycle – certainly as project implementers on the ground, but also as essential resources for insight on prioritising investment needs, programme planning, establishing appropriate assessment and evaluation criteria, etc. A lack of appropriate skills is a key barrier to effective public investment (OECD, 2014[19]), particularly among smaller beneficiaries, be they local authorities or SMEs. Reinforcing expertise and capacity is essential to help them manage the complexities linked to financing public investment with EU funds. One of the larger capacity gaps confronting beneficiaries is limitations in effective project design. For example, the 2015 OECD-CoR survey found that around two-third of subnational governments reported failure to take into account the full life cycle of infrastructure investment when designing projects (Allain-Dupré, Hulbert and Vincent, 2017[24]). This is significant, particularly given that subnational authorities often act as beneficiaries. Other gaps include difficulties aligning with project selection criteria, engaging in the call process, and navigating procurement requirements, all of which can play a role in the application or avoidance of financial corrections.

Building beneficiary capacity throughout the investment cycle can help them become more effective partners in the ESIF investment process. This can include taking into account their capacity levels in the investment planning phase, supporting them in the investment implementation process, and helping increase their ability in project and programme data collection and reporting to support monitoring and evaluation. This means beneficiary support usually involves multiple departments, units and experts in the MA (or IBs), and beneficiaries may have difficulty in identifying the right interlocutor to help answer their questions. Ideally, a single point of contact is very helpful to address this problem, while also ensuring an efficient and user-friendly channel for beneficiaries to seek help. A single contact point can facilitate closer engagement and support between MAs/IBs and the beneficiaries through project development and delivery: from the development, assessment and approval of business plans, the ongoing monitoring of progress (reporting and meetings), and closing those projects. This practice has been adopted by many national and regional MAs, including in Slovenia (targeting enterprise beneficiaries), Malta (targeting the ICT-related investment priority, with a specific focus on providing information on various regulations), and Wales (targeting all OP beneficiaries) among others (European Commission, 2017[14]; Welsh European Funding Office, 2019, unpublished[18]; EU-Skladi, 2014[25]; Government of Malta, 2015[26]). However, such a mechanism has not been universally established among MAs. Thus, more consideration should be given to streamlining the process of interacting with and supporting beneficiaries in order to increase efficiency and effectiveness.

This pilot action highlighted that in the short and medium term, more attention needs to be placed on addressing the various capacity gaps among beneficiaries. Making sure processes and procedures are clear, and being able to closely support beneficiaries is a fundamental step towards addressing irregularities, optimising operations and enhancing fund absorption.

Meeting the challenges behind building beneficiary capacity

In most cases, beneficiaries reported that there is room for the participating MAs, and also IBs, to improve the frequency and quality of their guidance and support. Yet, providing sufficient and effective support to beneficiaries poses a significant challenge to the MAs and IBs for a number of reasons. First, the heterogeneity of beneficiaries as a group, and the differences in their needs, resources and investment practices means that capacities will differ and capacity gaps may be extremely diverse. This makes offering tailored support potentially more resource intensive, and calls on a significant degree of flexibility in the capacity of MAs and IBs to offer such support. It requires that MAs and IBs develop a comprehensive understanding of their OP’s beneficiaries and their actual capacity at the start of a programming period. By doing so, the MA may be better able to tailor programming and calls to the ability of beneficiaries to respond, or to know early-on where capacity bottlenecks may arise in order to address them before they grow too large. This can be time and resource intensive.

Second, the very same challenges that confront MAs also confront beneficiaries, such as frequent changes to laws and regulations. MAs themselves must be able to manage such change before they can effectively help others.

Third, ineffective information and knowledge flows, be they in terms of frequency, the nature or type of information exchanged, the channel used, etc., is a limitation to beneficiary capacity building. In a survey carried out by a pilot MA, only 27.6% respondents3 knew about the information meetings organised by the MA for explaining the project application and selection criteria, and only 15.6% participated in such meetings.

Finally, identifying the capacity gaps of a targeted group of beneficiaries offers the MA insight into the problems that need to be addressed and who should be responsible for/involved in building beneficiary capacity. Does the problem only exist among beneficiaries of a specific OP? In which case the relevant MA can address the matter. Or, is it a systemic issue requiring support from the national coordination body and a cooperative approach among all MAs? Then the question arises of how to reach beneficiaries in a coordinated and efficient manner as they may face similar difficulties. Is it through associations targeting a beneficiary type (e.g. associations of local authorities) or a specific investment sector (e.g. transport)? In most cases there is room for multiple bodies to contribute to the capacity building effort, but it must be clear who is responsible for which aspect. For example, many small municipalities may lack capacity in data collection and reporting. To address this problem, a data task force can be created with experts from the national statistical authorities or relevant units, MAs, and representatives from line ministries and municipalities to understand beneficiary difficulties and seek for solutions. It could also help identify incentive structures that would improve municipal data reporting. This approach can be applied to tackling other capacity issues as well.

In general, organising training programmes is a common way to provide support to beneficiaries. Optimally, trainings should include both general explanations on EU funding mechanisms, objectives and benefits, financial and administrative requirements etc., and specialised topics and procedures in implementation. For the latter, thematic workshops can be useful, focussing on effective project design, implementation and results monitoring, identifying the most common procurement challenges confronting SMEs, or emphasising specific capacities necessary at the local authority level to generate integrated projects or ITIs. MAs and IBs can also collaborate with other institutions to design and deliver these workshops. Making sure that current and future workshops or training programmes are well targeted is a basic step towards supporting beneficiaries. For example, the Croatia Agency for SMEs, Innovation and Investments (an IB) delivered a very fruitful stakeholder workshop focused on identifying the most common errors leading to irregularities. Ideally, such workshops should cover topics that the beneficiaries themselves highlight as important or of interest, such as regulatory issues, state aid, etc. There are a number of ways to obtain such information, including through direct communication with beneficiaries or through surveys carried out to identify the needs of the targeted groups. Doing so can also help provide tailored assistance to different beneficiaries.

Promoting ongoing information exchange with and among beneficiaries

The importance of effective and ongoing information exchange with beneficiaries cannot be emphasised enough. Creating opportunities for regular and constant knowledge exchange is an effective way to manage capacity building, which takes time. Workshop and trainings, as mentioned above, serve a dual purpose – to share information and to build expert and practitioner networks, promoting exchange among beneficiaries themselves, including on good practices and techniques to avoid financial corrections. Regular working meetings or interactive workshops, distinct from trainings or broader networks, are also an option, as are communication materials targeting specific beneficiary concerns. Online platforms can also be mobilised as complementary mechanisms. Regular and clear updates regarding procedural changes, as well as information generated from workshops (e.g. frequently asked questions, pitfalls to avoid, common experiences and good practices), can be provided in an electronic format via OP websites, as well as the websites of organisations that beneficiaries may frequently visit (e.g. chambers of commerce, association of local authorities, etc.). Free online tutorials for beneficiaries that cover common questions, mistakes or misunderstandings, the ins and outs of applying to and implementing ESIF-funded projects, including questions of eligibility, etc. are also an option.

Partnering with beneficiary-support organisations

Professionals, professional organisations or associations, such as consultants, business chambers, and subnational government associations closely associated with targeted beneficiaries, should be included in capacity support practices. They can help MAs identify areas of particular weakness among their beneficiary constituents and contribute to workshop design and delivery, for example. Conversely, they are also important to include as participants in any beneficiary capacity building initiative in order to ensure that they are up to date on financial and administrative requirements, as well as opportunities associated with ESIF investment. This is particularly important since private beneficiaries, in particular SMEs, often rely on consultancies to help them with applications and managing projects financed by ESIF. MAs can regularly share updated information with the groups and associations who work closely with beneficiaries, while also gathering insight from them regarding OP design and implementation.

Table 4.4 below highlights some possible actions identified by the five MAs participating in this pilot project, and their stakeholders, to address the challenge of building beneficiary capacity.

Table 4.4. Sample Action Table: building beneficiary capacity

|

Goals/Sub-goals |

Identified Potential Actions |

|---|---|

|

Increase beneficiary awareness and understanding of ESIF financing processes and opportunities Increase beneficiary capacity to respond to project calls and implement ESIF financed projects Promote ongoing exchange with beneficiaries |

✓ Reinforce current beneficiary training programme activities with a module specifically focused on ESIF based on reported needs; update the scope of the training during the programming period. |

|

✓ Increase the availability and targeted focus of workshops for beneficiaries of all Priority Axes, for example, to support the application process, data collection needs and requirements, and practical tips to avoid financial corrections. Develop mechanisms to support information and knowledge exchange, e.g. by making information available on frequently asked questions, common experiences, good practices, common errors, etc. |

|

|

✓ Develop and launch a “knowledge workshop” series for beneficiaries on a specific theme and sponsored by the MA (or group of MAs, or national coordination body), targeting specific topics and bringing together relevant stakeholders to learn about managing or resolving issues surrounding the selected topic |

|

|

✓ Create a single contact point, or develop and distribute a clear contact list of different departments, with description of their responsibilities, to direct beneficiaries to reach the right interlocutor easily |

Actively engaging with a broad-base of external stakeholders

Active engagement with stakeholders throughout the investment cycle is an obligation in the Common Provisions Regulation for ESIF (Box 4.3). It is also the fifth of the 12 Principles forming the OECD Recommendation on Effective Public Investment across Levels of Government. It can help validate priorities and targeted actions, for example (OECD, 2019[7]). External stakeholders in ESIF funding and OP implementation are those outside of the MCS. While “internal” stakeholders include the MA, IBs, national coordinating bodies, and the EC, “external” stakeholders represent a broad range of interests within a country or region – from national authorities (e.g. line ministries and agencies) and subnational authorities (e.g. regional and local governments), to the private sector, professional organisations, civil society organisations, academia, etc. They also include beneficiaries, and those who support beneficiaries, such as consultants, professional or business associations, subnational government associations, etc.

Box 4.3. Stakeholder engagement and the partnership principles in ESIF regulation

Establishing partnerships with stakeholders throughout the investment cycle is an important component in managing ESIF. In recognition of this, it is included in Article 5 of the ESIF Common Provisions Regulation (1303/2013) as an obligation, and it is further elaborated in the European Code of Conduct on Partnership in the Framework of ESIF.

These regulations apply a broad scope to defining the stakeholders that should be considered partners, ranging from national, regional, local and urban authorities, and economic and social partners, to relevant civil society bodies (e.g. environmental partners, non-governmental organisations, and bodies responsible for promoting social inclusion, gender equality and non-discrimination, etc.), among others. The principles cover the whole investment cycle, including promoting transparent procedures in partner identification, timely disclosure, ensuring appropriate channels for consulting relevant partners when preparing the Partnership Agreement and OPs, involving partners in the preparation of calls and evaluation, and strengthening the institutional capacity of relevant partners.

Developing a strong, trusting, and cooperative relationship – a partnership – between the MA and external stakeholders, as well as with internal stakeholders, can facilitate the alignment of policy objectives and priorities, contribute to needs assessments, build programme legitimacy, support feedback and evaluation processes, and improve project quality overall. Not only does engagement generate a greater understanding of the different needs and interests among the various stakeholders involved, it contributes to improving the uptake of and compliance with programming, while boosting investment and project quality (OECD, 2019[7]). Building such partnerships with external stakeholders appears to be a challenge for many MAs, regardless of their years of experience in OP implementation. The European Network of Civil Society Associations indicates that non-government organisations (NGOs) in a variety of EU Member States do not consider themselves to be treated as active or “equal” partners, not having received MA feedback on comments made during the OP preparation process. In other cases there is a strong perception that communication with the MAs is “one-way”, steered by the national level and not fully inclusive of different types of subnational authorities (European Commission, 2016[29]).

Strengthening OP design and delivery through stakeholder engagement

Effective stakeholder engagement can help MAs build stronger evidence bases for programming, ensure that projects reflect beneficiary needs and – ideally – take into consideration beneficiary capacity to submit relevant and well-designed proposals. It works both ways however, as such engagement can also introduce greater understanding regarding the OP’s objectives and priorities and the MA’s expectations among external stakeholders, which contributes to building a common understanding between the parties. In addition, introducing an external perspective into the OP design, management and implementation processes can help identify risks and problems before they grow too large, and contribute to fostering more innovative solutions.

Stakeholder engagement also contributes to a sense of OP ownership – certainly among internal stakeholders, but among external stakeholders. By bringing stakeholders into the objective and priority setting process, for example, it can encourage stakeholders to articulate, agree on and then work to meet “their” investment objectives and to comply with constraints, thereby contributing to a more effective investment process. For example, in Wales many ERDF programmes support investments in place-based infrastructure, e.g. tourism, business sites or other infrastructure assets that support regional development. Developing programmes that accomplish this involves a process of regional prioritisation through which projects are (or should be) prioritised by regional bodies, providing advice to the Welsh European Funding Office (WEFO) that also directly informs the relevant investment decisions (Welsh European Funding Office, 2019, unpublished[18]). Ownership of objectives and initiatives however, develops over time and through constant interaction between implementation authorities and external stakeholders, particularly beneficiaries. An EU report on increasing the engagement of partners in ESIF implementation pointed out that in some cases, while stakeholder engagement is formally implemented it does not allow for real participation in the governance process, potentially hampering the development of a sense of policy ownership on the ground (regionally and locally) (European Parliament, 2017[30]). Greater simplicity, greater flexibility, and better relationships between internal and external stakeholders can help foster a stronger sense of ownership.

Stakeholder engagement should be undertaken throughout the OP investment cycle, from the planning and implementation process to the monitoring and evaluation phase. Such engagement is fundamental on two fronts. The first is to ensure that the approach taken to programme design, and the expectations associated with it, align with the realities of implementation capacity (be it of the MA, IBs, or beneficiaries), which is often limited in terms of administrative, political, financial and information resources. This is particularly true at the local authority level (Andreou, 2010[31]), as well as among beneficiaries that are SMEs. The second is to build ownership for OP-related projects among beneficiaries, including regional and local authorities. In the case of regional authorities, regional MAs can act in the interest of their regional OP and also as IBs for national OPs, and so they need to “buy-into” or “own” the objectives of the national OP and agree with the implementation process. In the case of local authorities, they not only face weak capacity, they also may face a citizenry (i.e. electoral base) that is sceptical of EU funds, often valuing other social or national funds for projects in their community. Making sure these stakeholders are part of the strategic process can contribute to smooth OP implementation in the long term. However, strategic engagement between the MAs and local authorities or third sector organisations appear limited in most cases.

MA capacity to manage the stakeholder engagement process can be limited. A study by the EC identified some cases where relevant stakeholders were not involved in drafting the OP nor did they receive information about it (EC-DG REGIO, 2016[4]). This may be due to a lack of time or resources on the part of an MA, just as it may imply a lack of understanding among stakeholders as to the strategic aspects of their participation, or a lack of interest. Regardless of the reason, it leads to limited stakeholder input into questions of strategic direction.

Building multi-stakeholder dialogue platforms for broader and more effective stakeholder input

Introducing a multi-stakeholder perspective into the investment cycle helps the MA gain greater insight into the needs, priorities and capacities of communities and businesses by tapping into stakeholder experience, expertise and insights relevant to priority setting, project design and implementation. It can also unlock the potential for innovative projects. Well-managed stakeholder consultation processes can also help limit corruption, capture and mismanagement, particularly for large infrastructure projects (OECD, 2017[8]). They also improve legitimacy, strengthen trust in government and cultivate support for and adherence to specific investment projects (OECD, 2017[8]; OECD, 2014[32])).

To make such broad stakeholder engagement practicable, establishing an ESIF dialogue forum that includes external stakeholders could be beneficial. Such an ESIF forum can be cross-sector and with a broad participant base from other public sector, private sector and civil society bodies in order to ensure that regional and local perspectives are incorporated into the initial strategy setting process and OP strategic implementation. A forum of this sort can be complemented by various activities, such as study tours for external stakeholders to understand the daily operation of the different bodies in the MCS, citizen panels to discuss specific topics, etc. The Monitoring Committee can serve as a platform to discuss how such a forum could be structured, and in broader terms, the Forum could play an active role in developing and improving stakeholder engagement activities.

Table 4.5 below highlights some possible actions identified by the five MAs participating in this pilot project, and their stakeholders, to address the challenge of actively engaging with a broad base of external stakeholders.

Table 4.5. Sample Action Table: actively engaging with a broad base of external stakeholders

|

Goals/Sub-goals |

Identified Potential Actions |

|---|---|

|

Strengthen OP design and delivery through stakeholder engagement Build multi-stakeholder dialogue platforms for broader input |

✓ Increase engagement across stakeholder groups by introducing a regular forum for multi-stakeholder, multi-level interaction and input. One option is to organise working groups (potentially based on existing Thematic Working Groups) with representatives from different levels of government and beneficiaries, to support the strategic planning and programming process, including priority setting. This can be expanded to encompass all OPs/MAs, as well as line ministries, municipal associations, etc. in order to identify broad challenges and solutions for ESIF management. |

|

✓ Carry out a survey or analysis of municipalities, counties and enterprises, including those that do not use ESIF, to understand their needs and their financial models, using the information as an evidence base to design future programming and calls. |

|

|

✓ Establish a strategic dialogue forum for the OP that includes internal and external stakeholders, and which could support vision setting, strategy design and investment priorities, as well as serve as an opportunity for information and knowledge exchange |

Rendering OP implementation processes more strategic