This chapter provides on overview of the main findings and policy lessons of the report. The empirical evidence is discussed in more detail in Chapters 2 to 5, while a detailed policy discussion is provided in Chapter 6.

The Role of Firms in the Gender Wage Gap in Germany

1. The gender wage gap in Germany and the role of firms: New evidence and policy lessons

1.1. New evidence on the gender wage gap

The gender wage gap between similarly skilled men and women stands at about 19% in Germany (on average over the period 2002‑18 among full-time workers). While this is lower than in most OECD countries, it is higher than in several nearby countries. This review provides a detailed analysis of the gender wage gap in Germany with a specific focus on the role of firms using administrative data that link employees and their employers. The analysis is placed in context by presenting comparable results for four selected nearby countries: Denmark, France, the Netherlands and Sweden. These benchmark countries share a number of important features with Germany. In these countries, the gender wage gap – after controlling for differences in skills – is similar or lower, notably in Sweden, ranging from about 14 to 19%; labour force participation among women is high and almost as high as for men; and part-time work tends to be common in Germany and the Netherlands.

1.1.1. About three‑quarters of the gender wage gap between similarly skilled men and women in Germany reflects differences within firms, while the remaining one‑quarter reflects differences in pay between firms

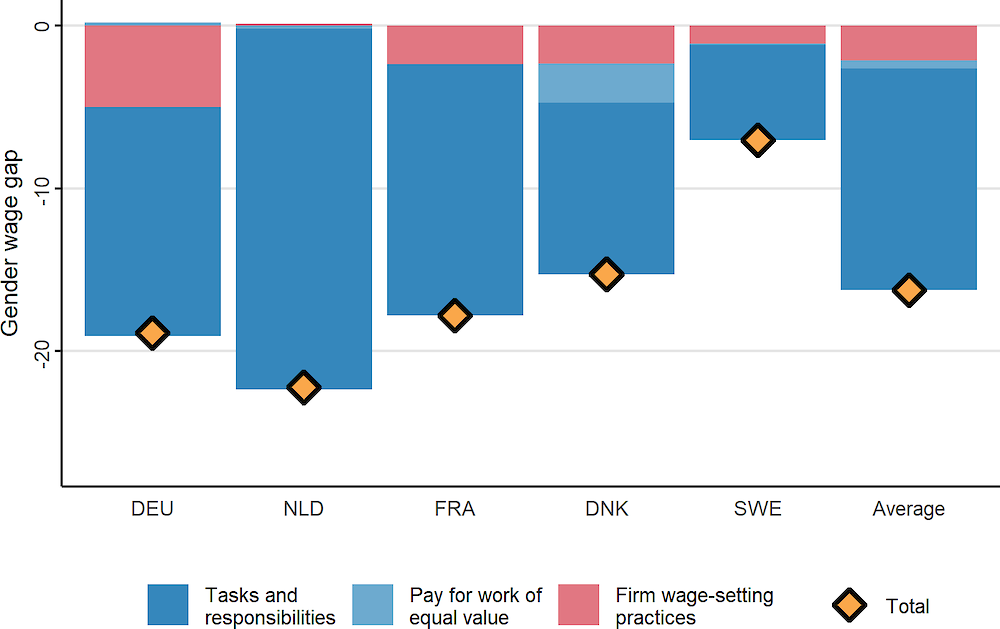

About three‑quarters of the gender wage gap between similarly skilled men and women reflects differences within firms (Figure 1.1, dark and light blue areas). These are mainly due to men and women having different tasks and responsibilities in the firm, while differences in pay for work of equal value tend to be small. Consequently, the key priority for policy is how to promote access for women to better jobs within firms. Pay transparency measures have an important role to play in this regard. Such measures are to a large extent motivated by the objective of tackling wage discrimination; yet, they usually do not focus on pay for equal work as only limited attention is given to differences in qualifications, tasks and responsibilities for the gender wage gap within firms. Indeed, their objective is to raise awareness about systematic pay differences within firms, irrespective of the exact source, and create discussion about their roots. The hope is that by questioning the adequacy of a firms’ existing remuneration, recruitment and promotion policies, this would promote the adoption of more gender-responsive human-resource frameworks.

The remaining one‑quarter of the gender wage gap is due to the fact that women are disproportionately employed in low-wage firms and low-wage industries (red areas). The between-firm gender wage gap reflects both the degree of gender segregation across firms and industries paying different wages and the importance of wage differences between firms and industries for workers with similar skills. The concentration of women in low-wage firms may amongst others be the result of discriminatory hiring practices by employers or the preferences of women for firms with flexible working-time arrangements. Firms that are more likely to offer part-time work arrangements also tend to offer lower wages. Pay differences between firms for similarly skilled workers are particularly large in Germany and have become more pronounced since the 1990s. This has been attributed to the erosion of collective bargaining and a greater emphasis on decentralised wage‑setting. The between-firm component of the gender wage gap is larger in Germany than in the benchmark countries where more centralised collective bargaining practices at sector-level have remained widespread.

The gender wage gap tends to be particularly high among high-wage workers. In Germany, the wage gap between similarly skilled men and women is about 50% higher for workers with high skills than workers with low or medium skills. This largely reflects greater differences in pay for work of equal value due to differences in worker bargaining power or employer discrimination. Compared to low-skilled workers, a larger fraction of pay is determined through individual bargaining and male workers appear better placed to take advantage of this. By contrast, the role of sorting across firms appears to be less important for workers with high skills. High skilled women are about as likely as their male counterparts to work in high-wage firms, whereas low-wage women are much less likely to work in high-wage firms. Differences in tasks and responsibilities are particularly important for workers with either low or high skills, but less so for workers with medium skills.

Figure 1.1. The role of differences in tasks and responsibilities, pay for work of equal value and firm wage‑setting practices in the gender wage gap

Note: Decomposition of gender wage gap between similarly-skilled women and men in components related to differences in tasks and responsibilities, pay for work of equal value (bargaining and discrimination) and differences in wage‑setting practices between firms (sorting). Reference period: 2002‑18 for Germany 2010‑19 for the Netherlands; 2002‑18 for France; 2001‑17 for Denmark; and 2002‑17 for Sweden. Average: Simple average across countries shown.

1.1.2. The gender wage gap within and between firms increases sharply around the age of childbirth, in large part due to gender differences in job mobility

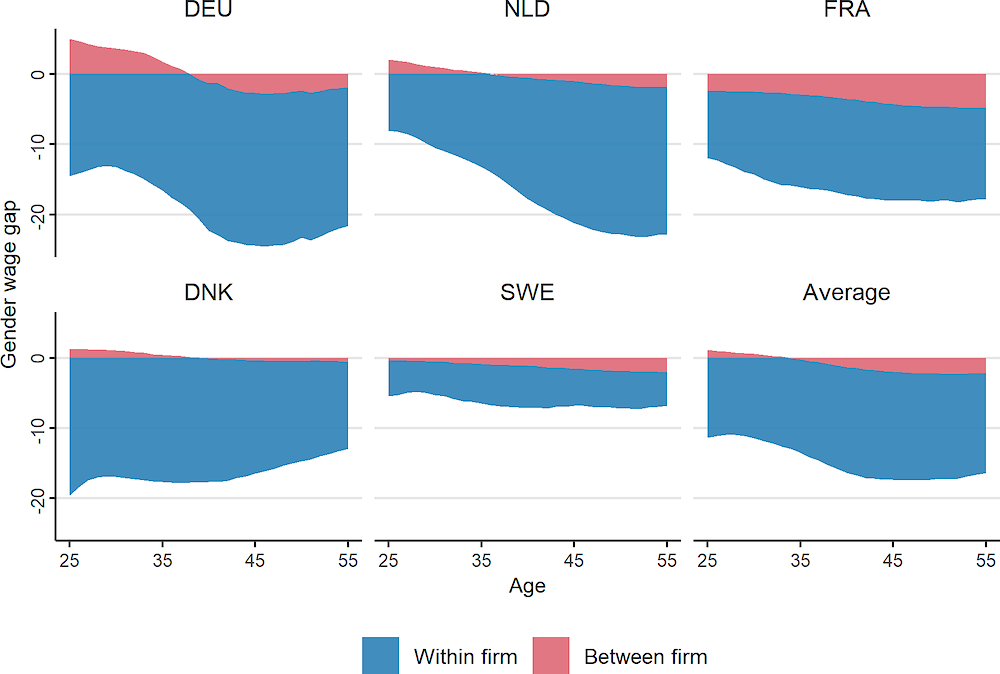

The gender wage gap increases sharply around the age of childbirth in Germany (ages 30‑40), and much more so than in the benchmark countries (with the exception of the Netherlands which exhibits a similar pattern) (Figure 1.2). The gender wage gaps grows both between and within firms. A possible explanation is that men increasingly sort into high-wage jobs as they advance in their careers, while women stay behind or may even be constrained to move into lower-wage jobs, which offer more flexible working time arrangements and make it easier to combine work and family responsibilities. The growth in the gender wage gap also coincides with a similarly sharp increase in the gender gap in working time as many women switch to part-time work after returning from maternity leave.

Figure 1.2. The gender gap within and between firms rises more strongly in Germany than in other selected countries

Note: Decomposition of gender wage gap between similarly-skilled women and men within firms and between firms by age. Reference period: 2002‑18 for Germany 2010‑19 for the Netherlands; 2002‑18 for France; 2001‑17 for Denmark; and 2002‑17 for Sweden. Average: Simple average across countries shown.

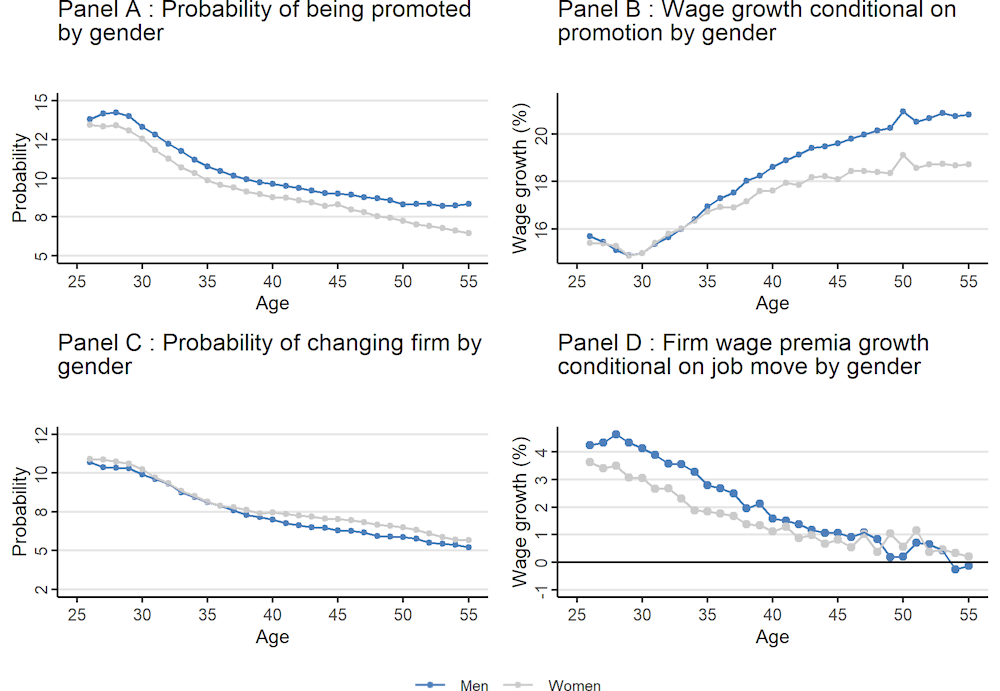

The increase in the gender wage gap with age reflects significant gender differences in upward job mobility within firms (i.e. promotions) and between firms (OECD, 2021[1]). Women are less likely to move up the job ladder than men, as a result of promotions within firms (as measured by significant wage increases from one year to the next) or by moving to higher-wage firms. Indeed, the bulk of the increase in the gender wage gap within firms between ages 25 and 45 can be attributed to the gap in the probability of being promoted (Panel A, while smaller wage increases conditional on being promoted also play a role (Panel B). In Germany, gender differences in the incidence and nature of promotions explain up to 80% of the increase in the gender wage gap within firms between 25 and 45 (compared with 75% in the benchmark countries). Job mobility between firms explains less of the gender wage gap’s evolution, particularly in Germany. Women are not less likely to change jobs (Panel C), but when they do, they get significantly smaller increases in firm wage premia than men (Panel D). This suggests that women often change jobs not for pay but for personal reasons, e.g. having more flexible working-time arrangements, working closely from home, or following a partner (OECD, 2018[2]). Differences in the nature of job mobility between firms account for 16% of the increase in the between-firm gender wage gap between age 25 and 45 in Germany (compared with 65% in the benchmark countries).

Figure 1.3. Gender differences in job mobility within and between firms in Germany

Note: Sample restricted to full-time workers. Job-to-job mobility rate is defined as the number of workers changing firm between year t and t‑1 as a share of employment in year t‑1. The probability of being promoted is defined as the share of persons in employment at t‑1 experiencing a significant increase in pay between t and t‑1 (more than 10%).

Systematic gender differences in the extent and nature of job mobility between and within firms show that men and women do not have the same opportunities for career advancement. Policies that make it easier for women to stay in work (and not have to drop out of the labour force for family commitments) and gain experience just as men, so they have equal chances for career progression within and across firms are therefore key. This includes family policies that contribute to a more equal sharing of household responsibilities (e.g. incentivising fathers to take more parental leave) as well as support a more equal sharing of paid part-time and full-time work (e.g. universal childcare, reducing effective marginal tax rates on second earners) (OECD, 2017[3]; OECD, 2019[4]), but also policies directed at firms that encourage a more equal representation of women in high-paid occupations (e.g. pay transparency measures, voluntary target-setting and quota’s towards gender balance in leadership positions).

1.1.3. Career breaks around childbirth contribute to the motherhood penalty in earnings and the rise in the gender wage gap within firms

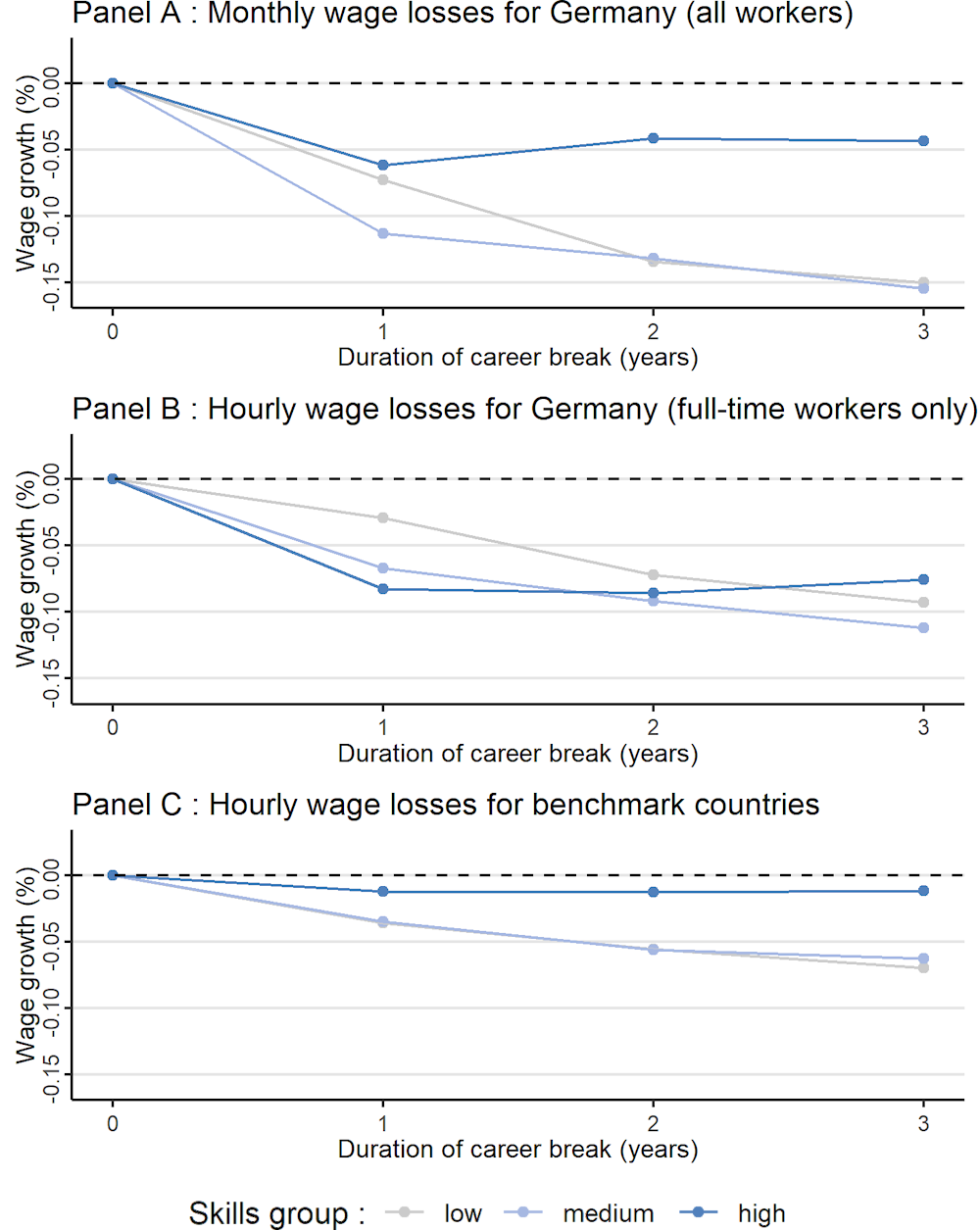

Career breaks around the age of childbirth account for a large fraction of the “motherhood penalty”, i.e. the shortfall in wage or earnings growth following childbirth. These in turn play an important role in determining the evolution of the gender wage and earnings gaps over the working life. Career breaks around the age of childbirth, measured as non-employment spells, are more common among low-skilled women and carry considerable earnings losses (Figure 1.4). Women’s missed experience or human capital depreciation during career breaks result in lower wage growth within firms (Panel B). While most women return to the same firm after a career break, many women switch to part-time work, further reducing their earnings (Panel A). This is particularly common among women with low to medium levels of skills.

Significant differences across OECD countries in the incidence and duration of career breaks may signal the role played by family policies (e.g. child-care, parental leave, working-time regulations), as well as the broader institutional set-up (e.g. employment protection, collective bargaining). However, they also reflect deeply engrained cultural differences in social norms. For instance, traditional gender norms, which favour a predominantly female provision of care work, are substantially more common in Germany than in Sweden. Traditional gender norms may also explain the greater prevalence of career breaks in Western Germany compared with Eastern Germany. This suggests that family policies need to be complemented with other policies that can help foster gender-friendly social norms (e.g. school interventions, pay transparency measures).

Figure 1.4. Wage losses following career breaks around motherhood

Note: Sample: Women aged 25 to 34. Reference period: 2002‑18 for Germany; 2010‑19 for the Netherlands; 2002‑18 for France; 2001‑17 Denmark; 2002‑17 for Sweden. Skill groups are defined based on terciles of the wage distribution by gender and year of birth.

1.2. A policy package to curtail gender pay gaps

A key analytical insight is that the wage gap between men and women with similar skills in Germany, as well as other nearby countries, mainly reflects the tendency of women to work in jobs with less demanding tasks and responsibilities than men, and to a lesser extent also in jobs located in lower wage firms. Moreover, these gender differences tend to grow after having children, and much faster in Germany than in other nearby countries. Much of this can be attributed to the unequal sharing of household responsibilities between parents, highlighting the importance of gender-sensitive family policies, but also of broader measures that can shift social norms. This includes quotas, and target setting towards greater gender balance in leadership positions, gender reporting requirements and pay transparency measures, which several countries have recently introduced and appear to be promising. However, these latter initiatives are relatively “young” and more work is needed to better understand how the design of gender reporting requirements affects their effectiveness and to what extent complementary policies are needed. Moreover, there is also a need to reduce gender wage gaps due to differences in wage‑setting practices or gender segregation across firms.

There are many other aspects that affect gender pay gaps. First education and educational choices matter. In this regard, women have made great strides. Nowadays young women in OECD countries are on average more likely to obtain higher educational attainment than young men (OECD, 2021[5]). Nevertheless, young men are still more likely than young women to graduate in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) studies, which generally lead to career patterns in higher paid occupations and jobs. In general these educational choices are related to attitudes rather than aptitude (OECD, 2015[6]), and changing social norms that affect educational choices takes time.

Changing workplace behaviour also takes time. A big gender gap can be seen in the way how working men and women take leave of absence to care for young children, or make use of flexible workplace practices such as part-time work to find a better work/life balance. In addition, how parents can participate in work also depends on the availability and accessibility of affordable formal childcare. Another factor is the tax benefit system and the financial incentives it generates to work and work full-time. A detailed analysis of all the different factors and policies that affect the gender wage gap within and across firms is beyond the purview of this study, but below directions for (further) policy reform are outlined that could help, in time, to further reduce gender pay gaps across the life‑course.

1.2.1. Family policies to counter increasing wage gaps over the life course

The arrival of children has a big impact on family life and tends to increase pressures on work-life balance – see also OECD (2021[7]). In Germany, as well as in the Netherlands and France (to a smaller extent), the gender pay gap increases rapidly between the ages of 30 and 40. At this stage in the life course, women are more likely to take paid leave and or work part-time, which has negative repercussions for career and earnings progression. Policies that help men and women better share paid and unpaid work can therefore contribute considerably to narrowing gender pay gaps within and across firms. When periods of parental leave and part-time work are time‑limited and shared by men and women, the risk of women being side‑lined in promotions and pay increases can be mitigated.

Continue to promote more equal uptake of parental leave by fathers and mothers

Since 2007, subsequent reforms have progressively changed the German parental leave system into one that encourages mothers to take parental leave for one year (rather than two or three, as previously), incentivises fathers to take at least two months of leave, and facilitates leave‑taking by both parents on a part-time basis (OECD, 2017[3]). In terms of the effective duration of paid leave for fathers and mothers, the German system is comparable to that of Sweden (where 90 days are earmarked for each parent (Försäkringskassan, 2022[8])) and Denmark (where 11 weeks are earmarked to each parent for parents to children born from 2 August 2022 (Beskæftigelsesministeriet, 2022[9])). These reforms to the German parental leave system were a good step forward in ensuring that mothers return to work (Bechara, Kluve and Tamm, 2015[10]), and that fathers take more leave to care for children. Following the introduction of the non-transferability element of two bonus months of paid parental leave in 2007, German fathers almost doubled their uptake of parental leave entitlements. By 2018, 40 fathers for every 100 births were taking some leave (Destatis, 2021[11]). Under the new coalition government, the number of bonus months is scheduled to be increased to three months (Die Bundesregierung, 2021[12]), which would be the same as the 90 days of non-transferable leave awarded in Sweden.

Paid parental leave is available for twice as long, at half the payment rate, when the recipient works part-time (Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, 2019[13]). Parents can take up to 24 months (not including bonus months) of Parental Allowance Plus per child when combining the parental leave allowance with some earnings from work, which with the planned additional bonus month could be 30 months of part-time leave across both parents. In addition, “the bridging part-time leave and work legislation” offers the guarantee to return to full-time work after a given period of time (Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, 2020[14]). One option would be to facilitate parents splitting leave at a higher wage replacement, but for a shorter period of time. The higher wage replacement would further incentivise primary earners to use and share the part-time leave options with partners. The new coalition government aims to simplify relevant administrative processes for take up, but it is unclear what the effect of such efforts might be.

Provide extended-hours education and care for all young children

To facilitate an earlier return to work and particularly to full-time work, a comprehensive early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) system is also key. Broadly in parallel with parental leave reform, German policy has moved in this direction since the mid‑2000s. Out-of-pocket centre‑based net childcare costs for parents are the lowest across the OECD (OECD, 2022[15]), and thanks to a marked increase in recent years – ECEC participation rates are now just above the OECD average. Nevertheless, capacity continues to be an issue. In 2018, 38% of 0‑2 year‑olds were enrolled in early childhood education and care services in Germany. This is similar to the OECD average (36%) but significantly lower than, for example, France (60%) (OECD, 2022[16]). It appears that the growing supply of childcare places for under‑3‑year‑olds has not kept up with increased demand over the past five years (Geis-Thöne, 2020[17]; OECD, 2017[3]).

Families working full-time need care support when children attend school to cover the hours not covered by the curriculum. Only 21% of 6‑11 year‑olds in Germany attended centre‑based out-of-school-hours services in 2019, compared to 66% in Denmark and 62% in Sweden (OECD, 2022[16]).

It is important that supply increases in line with demand so that parents are able to return to full-time work as soon as they wish. A growing gap between demand and supply in early childhood education and care and out-of-school-hours spaces would hamper the ability of both parents to return to full-time employment as children get older, and this is likely to disproportionately affect mothers. There is an opportunity for Germany to do more to increase the supply of childcare places and out-of-school provision in areas where they are most needed. As a secondary benefit, expanding provision to more children would also present an opportunity to recruit more men into the childcare and education sector (OECD, 2019[18]).

Reduce financial incentives for (female) spouses to take up part-time work

In Germany, the gap in hours worked between men and women increases around childbearing age and remains large into later life, contributing to the persistence of the pay gap at older ages. The lack of out-of-school-hours services may contribute to parents opting to remain in part-time work, but there are also elements in the tax/benefit system that weaken the financial incentives for spouses with the lowest earnings in households (often women) to work full-time. Indeed, married couples and civil partners can file their income taxes together, with joint liability for the aggregated income of the couple (“Ehegattensplitting”). The result is that the couple can jointly be taxed at a lower marginal rate than they would have been if the members of the couple had filed taxes on their own (due to progressive tax schedules). If there are large differences in earnings, joint liability reduces the overall tax payment but increases the marginal tax rate for the lower-earning partner (Bachmann, Jäger and Jessen, 2021[19]).

The new government has announced plans to reform the joint taxation system. The coalition agreement spells out the intention to reform the combination of tax classes (Die Bundesregierung, 2021[12]). Rather than apply one tax rate on joint earnings, each individual partner would have to pay taxes on their individual earnings. Due to progressive tax schedules, this will increase the marginal tax rate for main earners and reduce it for second earners, i.e. increase incentives for second earners – mainly women – to work more hours for pay.

1.2.2. Policies targeted at firms to tackle gender wage gaps within and between firms

The gender wage gap is largely concentrated within firms. A wide range of public policies can address gender wage gaps within firms. For example, equal pay laws and anti-discrimination laws are in place across the OECD. These are crucial for establishing workers’ rights, but in practice they put the onus on individual workers to ensure that equal rights are adhered to. These laws can therefore do little to close gender pay gaps more broadly. However, there are other policy measures that directly target firms to help curtailing gender pay gaps within firms, including pay transparency tools, quotas and voluntary targets. Wage‑setting institutions can further help to reduce gender wage gaps between firms, which are more pronounced in Germany than in nearby countries.

Continue to evaluate the effectiveness of new pay transparency measures

To reduce persistent gender wage gaps and more specifically raise awareness and spur discussions about systematic pay differences within firms, pay transparency measures have gained momentum in policy packages over the past decade. In European OECD countries their development was often inspired by the 2014 European Commission Recommendation on strengthening the principle of equal pay between men and women through transparency (European Commission, 2014[20]).

The primary value of pay transparency measures is to provide aggregate statistics as benchmarks against which employees can compare their own pay packages and to stimulate debates about equal pay within firms, in the media and in society at large. Job classification systems to provide benchmarks and correct for potential gender bias in job valuations (commonly used, although not mandated, in the Netherlands); non-pay reporting of gender-disaggregated information (used in Germany); regular gender pay reporting, without audit (found in Denmark); and regular pay gap reporting but with Audit (used by France and Sweden). Some countries, including Denmark, France, and Sweden, discourage non-compliance through the ability to issue fines (Ceballos, Masselot and Watt, 2021[21]).

Since these instruments have been introduced relatively recently, there are still questions about how best to design pay transparency policies. As this type of policy packages gain momentum it will be useful if countries collected data and undertook impact evaluations to understand more about their effectiveness, including the amount of detail that should be reported, to whom the information should be shared, how to best leverage the information in tribunals and courts, and how to streamline processes for firms.

Strengthen job classification systems to better inform evaluation of competence and pay

Job classification systems can help objectively match roles and responsibilities with individuals in possession of the required skills. Skills mismatch is particularly important in Germany where more young women than men are overqualified relative to the skills requirements of their position (Berlingieri, 2012[22]). In a similar vein, job classification systems provide more transparency in terms of what is required for a promotion, which can contribute to more objective recruitment and promotion practices. Both these factors can contribute to more women receiving promotions to better-paid roles and responsibilities within firms, which in turn would contribute to reducing the considerable wage gaps within firms. Finally, gendered norms and expectations play a role in sustaining gender wage gaps as they influence job search and wage negotiations to the benefit of men relative to women. The combination of pay transparency measures and job classification systems makes salaries more transparent for men and women across specific job categories.

Improve workers’ access to information on wages through pay reporting measures

In 2017, Germany mandated that companies must report on the measures they have taken to promote gender equality and equal pay, and the results are subsequently published in the Federal Gazette. However, the German reporting policy deviates from reporting policies in some other OECD countries where companies are required to report average and/or median pay gaps to stakeholders like employees, workers’ representatives, social partners, a government body, and/or the public (OECD, 2021[23]). In Germany, companies (given that they employ more than 200 staff) only have to provide, upon request, the average wage of a group of colleagues of the opposite sex doing work of equal value to the member of staff in question (Aumayr-Pintar, 2019[24]). In addition to providing staff with some benchmark, the publication of pay reporting results can put firms with large wage gaps in a bad light, making it difficult for them to attract talent and/or clients and/or satisfy shareholders. This could spur management to take action against gender pay gaps. Sharing information about the average wages of men and women within firms, especially when disaggregated by job classification, can support underpaid workers to negotiate up their wage (Baggio and Marandola, 2022[25]).

Explore comprehensive equal pay auditing to mainstream gender sensitive thinking

Equal pay audits usually require analysis of the proportion of men and women in each category of employee or position, an analysis of the job evaluation and job classification system used, and detailed information on pay and gender pay differentials. They often offer more straightforward avenues for follow-up action than simpler pay reporting measures, and reduce pressure on individuals to address their own disadvantage (OECD, 2021[23]). Audits can directly affect gender pay gaps in ways similar to simpler pay transparency measures. However, their key contribution is to mainstream gender sensitive thinking within firms and provide evidence for more targeted action by policy makers and firms. Audits can highlight underlying drivers, including wage gap increases during years of childrearing and pay gaps due to corporate hierarchies. Auditing requirements could be introduced for large as well as small firms provided there are ways (e.g. provision of financial support towards the cost, on-line calculators) to offset the administrative burden that (primarily smaller) firms face.

Continue to use quotas and soft measures to help breaking the glass ceiling

The different family, fiscal and wider social policy measures above encourage both men and women to return to high-quality jobs following career breaks and compete for promotion on an equal footing. In addition, various countries have introduced mandatory quotas, voluntary target setting and/or a range of other measures such as disclosure requirements, capacity-building actions, certificates and awards (OECD, 2017[26]). In 2015, Germany adopted a law that required some supervisory boards of publicly traded companies to have at least 30% women and 30% men, and other companies to set voluntary targets (Zeldin, 2015[27]). Germany ranks among the top 10 of OECD countries with the highest share of women on boards of publicly listed companies. Targets and quotas can help address gender gaps in the short and medium term, but they are not a sustainable solution in themselves. The key to sustainable success is the development of a gender-balanced cohort of competent employees for promotions into senior positions within companies and across sectors. For instance, while Sweden does not have mandatory quotas, the Government’s gender equality target stipulates that at least 40% of boards should be made up of women. Progress has been made over the past few years and by 2020, 38% of board seats were held by women. A more gender balanced workforce throughout organisational hierarchies is key to narrowing gender pay gaps within-firms and between sectors.

Wage‑setting institutions can help reduce the gender wage gap between firms

Strengthening wage‑setting institutions in the form of minimum wages and collective bargaining can help reduce the between-firm gender wage gap by compressing wage differences between firms. Differences in pay between firms (unrelated to worker composition) in countries with more centralised collective bargaining arrangements are about half that in countries with decentralised ones. It appears that in Germany, decreasing collective bargaining coverage has contributed to growing differences in wage premia between firms, which in turn has slowed down progress in narrowing the gender wage gap. The introduction of a statutory minimum wage in 2015 has likely slowed the growth in wage premia dispersion and reduced the gender wage gap between firms among low-wage workers. Recent increases in the minimum wage are expected to lead to a further narrowing of this gap.

Box 1.1. Policy recommendations

Progress in reducing gender pay gaps has been slow. However, that should not deter government policy and firms to focus on improving workplace conditions and career opportunities for men and women to continue narrowing gender wage gaps in future. In Germany, more so than in several other nearby countries, the gender wage gap widens during childrearing years. Since the mid‑2000s, German policy has moved towards supporting a more gender – balanced reconciliation of work and family life, and German policy should carry on along this path. In particular:

Continue to use paid parental leave policies to promote equal use by fathers and mothers. One option could be to facilitate parents splitting leave at a higher wage replacement, but for a shorter period of time.

Continue to invest in the capacity (also in hours) and quality of Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) and out-of-school hours (OSH) services, particularly in areas where such support is most needed.

Make changes to the tax/benefit system to ensure that both partners in a couple family have equally strong financial incentives to work. Changes to the joint taxation system that will reduce marginal tax rates for secondary earners – mainly women, and incentivise them to supply extra hours to the market, would be welcome.

Firms and their management should make their workplace practices conducive to combining work and family life, by encouraging fathers to take parental leave or working part-time for a specified period, and increase full-time work opportunities to returning mothers so that firms can make use of a wider pool of productive workers.

Three‑quarters of the gender wage gap between similarly skilled men and women is due to within-firm differences in wages, and the following labour market policies can also help reduce gender wage gaps:

Use pay transparency measures to directly address gender wage gaps by providing objective and measurable data. Germany should adopt a more comprehensive set of pay transparency tools to allow firms, employees and policy makers to maintain informed discussions about developments of the gender wage gaps in workplaces.

Strengthen job classification systems (currently optional in Germany) which help objectively match roles and responsibilities with individuals in possession of the required skills. Skills mismatch is particularly important in Germany where more young women than men are overqualified relative to their position.

Consider introducing a combined package of job-classification systems and pay transparency measures to provide employees with benchmarks to which they can compare their own pay packages. This would contribute to reducing within-firm gender wage gaps, but also increase awareness of job-opportunities elsewhere and enhance mobility across firms.

Evaluate comprehensive equal pay auditing systems to mainstream gender sensitive thinking. Consider introducing detailed equal pay audits, on a pilot basis, as the detailed information they generate potentially offer more straightforward avenues for follow-up action than simpler pay reporting measures. They also help mainstream gender sensitive thinking within firms.