Building on OECD (2021[1]), this chapter describes the conceptual framework for analysing the wage gap between men and women with equivalent skills within and between firms, the empirical approach and the data that is used in this review.

The Role of Firms in the Gender Wage Gap in Germany

2. Framework, methodology and data

2.1. Conceptual framework

The conceptual framework is based on two important premises. First, a significant gender wage gap persists even among similarly-skilled men and women. Indeed, in most countries, the gender wage gap tends be larger and more persistent when focusing on similarly-skilled men and women than when focusing on the raw gender wage gap (OECD (2021[1]) showed that Germany is the only country among 23 European countries where the gender wage gap becomes smaller, albeit only slightly, when controlling for differences in skills).This reflects the fact that the gender gap in education has largely closed and that in many countries young women now have higher levels of education than men on average (Goldin, 2014[28]). Second, the gender wage gap tends to increase over the life‑course in most countries, including in Germany (Tyrowicz, van der Velde and van Staveren, 2018[29]). This likely reflects to a large extent the role of childbirth in shaping the career progression of women across occupations and firms (Kleven et al., 2019[30]; OECD, 2018[2]). Consequently a life‑cycle perspective is needed that allows following men and women across firms and jobs within firms as they progress in their careers.

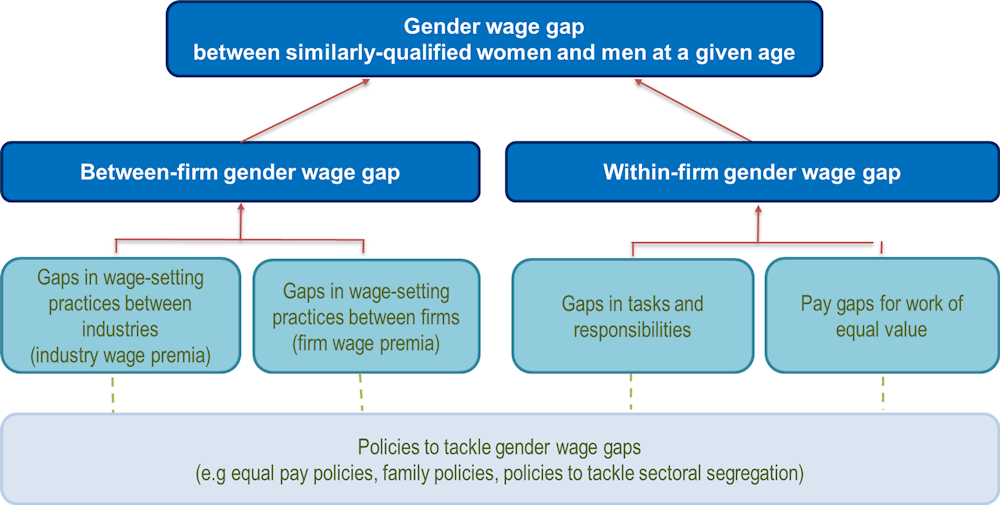

Based on these considerations, this review focuses on the gender wage gap between similarly skilled men and women at each age with an emphasis on the specific role played by firms. The role of firms is analysed by decomposing the gender wage gap into a between-firm and a within-firm component. The between-firm component captures the role of differences in firm wage premia (or “wage‑setting practices”) between firms in the gender wage gap between similarly-skilled men and women due to the sorting of women into low-wage firms and industries. Firm wage premia refer to the component of wages determined by the firm’s characteristics and not those of workers. They may reflect the performance of the firm, its wage‑setting power and human-resource policies. The within-firm component captures differences in pay between similarly-skilled men and women within firms due to differences in tasks, responsibilities or pay for work of equal value (e.g. bargaining, discrimination). The relative size of these different gender-wage‑gap components offers important information for the design of public policies that seek to tackle the gender wage gap. A schematic representation of the decomposition is presented in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1. Framework

Source: OECD (2021[1]), The Role of Firms in Wage Inequality: Policy Lessons from a Large Scale Cross-Country Study, https://doi.org/10.1787/7d9b2208-en.

2.2. Empirical approach

To empirically implement the within and between-firm decomposition of the gender wage gap for similarly-skilled men and women, this review builds on Goldin et al. (2017[31]) and Card, Cardoso and Kline (2016[32]). This involves in a first step estimating wage equations with flexible earnings-experience profiles by gender both without and with firm-fixed effects and, in a second step, separately estimating for men and women a wage equation with firm-fixed effects (see Box 2.1). Experience is measured in potential terms using age and therefore does not take account of for example career breaks. The firm-fixed effects capture difference in wage‑setting practices as reflected by firm wage premia, i.e. the part of average firm wages that is unrelated to the characteristics of the workforce. The specification without firm-fixed effects allows documenting the overall gender wage gap at any age conditional on worker characteristics (education). The specification with firm-fixed effects allows documenting the gender wage gap within firms at any age conditional on worker characteristics. The difference in the gender wage gap between the two specifications captures the between-firm component of the gender wage gap due to the sorting of men and women across firms paying different wage premia. The gender-specific wage equations with gender-specific firm-fixed effects allow providing an indication of the role of wage bargaining and discrimination by comparing the firm-fixed effects for men and women within the same firm.

Box 2.1. Decomposing the gender wage gap between and within firms at each age

Basic decomposition of the gender wage gap within and between firms

The decomposition of the gender wage gap at each age within and between firms for workers with similar skills is implemented following Goldin et al. (2017[31]) by estimating the following pair of wage equations without and with firm-fixed effects:

where denotes the wage of worker i in firm j at time t, denotes a vector of observable worker characteristics (education or occupation dummies, decade‑of-birth dummies); denotes the estimated returns to these characteristics (restricted to be the same for men and women);denotes a full set of age dummies, denotes the returns to age for men, denotes a gender dummy that equals one for women and zero otherwise, denotes the gender wage gap at each age and in Equation 2.2 denotes a full set of firm-fixed effects. The firm-fixed effects capture difference in wage‑setting practices as reflected by firm wage premia, i.e. the part of average firm wages that is unrelated to the observable characteristics of the workforce. Equation 2.1 is used to estimate the overall gender wage gap between similarly skilled women and men at each age, while Equation 2.2 is used to get the gender wage gap between similarly skilled women and men at each age within firms. The difference captures the gender wage gap between similarly skilled women and men at each age that is due to sorting.

Extended decomposition of the gender wage gap

The decomposition of the gender wage gap at each age within and between firms can be extended for workers with similar skills, tasks and responsibilities following Card, Cardoso and Klein (2016[32]) by estimating the following wage equation with worker and firm-fixed effects separately for men and women:

where denote worker fixed effects, denote (gender-specific) firm-fixed effects, which capture differences in firm wage premia between firms as well as between women and men within firms, denote year fixed effects, denotes time‑varying worker characteristics, and more specifically a third-order polynomial in potential experience and denotes gender-specific returns to potential experience.

The decomposition is used to identify the role of firm wage premia in the gender wage gap and the extent to which differences in firms wage premia are due to within-firm differences (bargaining and discrimination) or between-firm differences (sorting). The bargaining effect is obtained by comparing the firm-fixed effects of men and women within each firm weighted by the distribution of women across firms, while the sorting component is obtained by comparing the average firm-fixed effect firms for women weighted by the distribution of women across firms with that weighted by the distribution of men across firms.

2.3. Data

The decomposition of the gender wage gap within and between firms is implemented using harmonised linked employer-employee data for Germany as well as four nearby countries (Denmark, France, the Netherlands, and Sweden). The linked employer-employee data used in this study mainly stem from administrative records designed for tax or social security purposes. Consequently, these data tend to be very comprehensive (in some cases, covering the entire population of workers and firms) and of very high quality, notably with respect to information on wages, given the potentially important financial or legal implications of reporting errors and extensive administrative procedures for quality control. Importantly, these data allow measuring gender wage gaps with great precision, decomposing them within and between firms and analysing the determinants of wage and employments gaps within individual firms.

The analysis for Germany is based on the Sample of Integrated Employer-Employee Data (SIEED) produced at the Research Data Centre (FDZ) of the Federal Employment Agency (BA) at the IAB (Schmidtlein, Seth and Vom Berge, 2020[33]). This is a 1.5% random sample of all establishments with the full employment histories of any worker in those firms that was affiliated with social security and included in the Integrated Employment Biographies at any point between 1975 and 2018. The data for Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden refer to the universe of workers and firms, whereas the data for France refer to an 8.5% random sample of workers. For further details on the data for Germany and those for the other countries, please see Table A.1 of the Annex.

The review focuses mainly on the gender gap in hourly wages, while the gaps in monthly earnings and working time are also used to provide indication of the broader context. Wages and earnings are consistently measured in gross terms (before the deduction of taxes and adjustments), while taking account of bonuses and overtime payments where possible. Among the countries considered, Germany is the only country for which no detailed information on working time is available. Following Bruns (2019[34]), hourly wages are approximated by focusing on monthly earnings for full-time workers. The difference in the gender gap in monthly earnings (for all workers irrespective of their working time status) and that in hourly wage yields the gap in working time and hence provides an indication of the distribution of part-time work between men and women. For all countries, the analysis is restricted to individuals aged 25‑60 in the private sector in firms employing at least one woman and one man. It excludes the self-employed, apprentices and workers in mini-jobs. Mini-jobs are defined for the present purposes as earning less than 10% of the full-time median in the German data, and less than 20% of the full-time minimum wage or, if no minimum wage exists, 10% of the full-time median in the other countries.

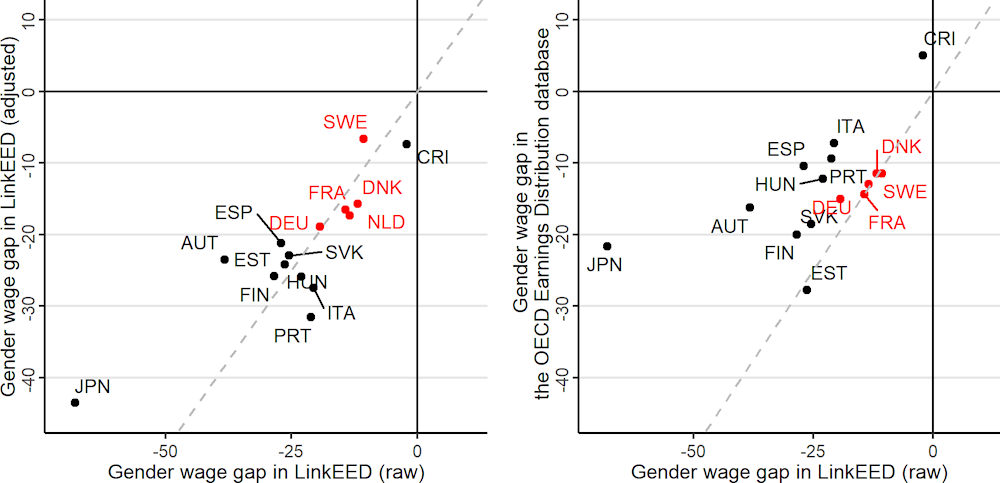

The gender wage gap in Germany is the highest among the five countries considered in this review, but about average when considering a broader group of countries for which data are available in the OECD Linked Employer-Employee Database (LinkEED) (Figure 2.2). For the five countries considered in this review, the raw gender wage gap tends to be lower than that for other countries included in OECD LinkEED, both when focusing on the raw gender wage gap and when focusing on the adjusted wage gap between similarly skilled men and women (Panel A). Moreover, for the five countries considered in this review, the gender gap is very close to what is documented in the OECD Earnings Distribution database, which is the source for the official OECD estimates of the gender wage gap (Panel B). For other countries included in OECD LinkEED, the gender wage gap tends to be larger than in the OECD Earnings Distribution database, resulting in a somewhat different cross-country ranking (see the note to Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2. Comparing different measures of the gender wage gap

Note: Differences in gender wage gap results reflect in part the focus of the OECD Earnings Distribution database on full-time workers, whereas the gender wage gap in OECD LinkEED also comprises part-time workers (with the exception of Germany), which typically receive lower wages and are more likely to be female. Another difference is that the OECD Earnings Distribution Database does not always take account of bonuses and overtime payments, which tend to be more important for men, understating the true gender wage gap. This explains the sizeable difference in the estimated gender wage gap for Japan.

Reference period: 2001‑13 for Japan; 2002‑17 for Portugal; 1996‑2015 for Italy; 2002‑19 for the United Kingdom; 2003‑17 for Hungary; 2004‑16 for Finland; 2003‑18 for Estonia; 2000‑18 for Austria; 2014‑19 for the Slovak Republic; 2006‑18 for Spain; 2002‑18 for Germany; 2010‑19 for the Netherlands; 2002‑18 for France; 2001‑17 Denmark; 2006‑17 for Costa Rica; and 2002‑17 for Sweden.

Source: OECD Earnings Distribution Database and OECD LinkEED.