This chapter focuses on the average difference in pay between similarly skilled men and women in Germany in comparison with selected nearby countries. It starts by decomposing the gender gap in labour earnings into the components associated with the gaps in working time and hourly wages. It then analyses to what extent the gender gap in hourly wages is concentrated within or between firms (standard decomposition). It concludes by analysing to what extent the gender gap in average hourly wages and along the wage distribution reflects differences in tasks and responsibilities or differences in pay for work of equal value (detailed decomposition).

The Role of Firms in the Gender Wage Gap in Germany

3. The gender gap in average pay and the role of firms

3.1. The gender gap in monthly earnings, wages and working time

3.1.1. The gender gap in earnings in Germany is high due to a large gap in hours worked in combination with a significant gap in hourly wages

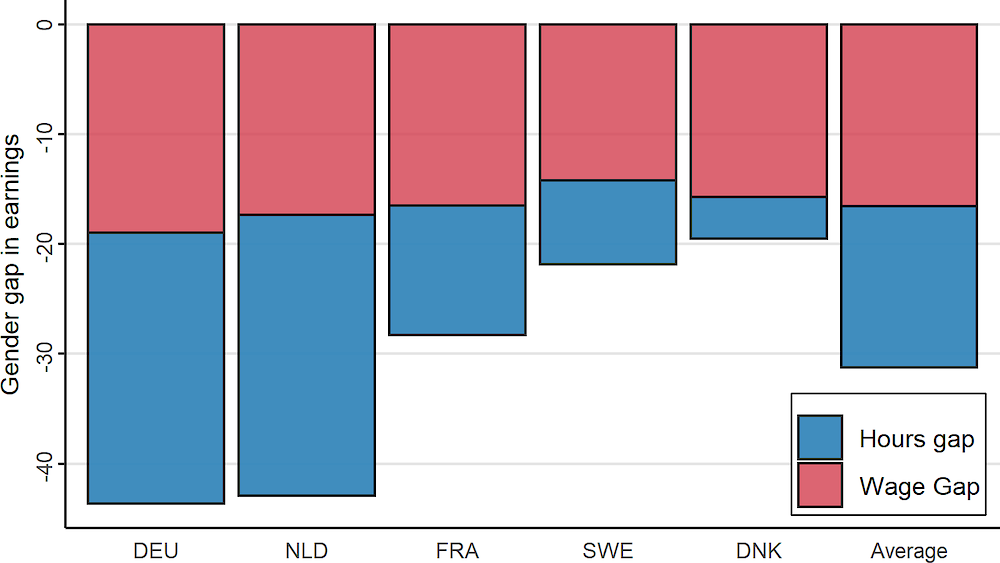

The gender gap in monthly earnings was above 40% in Germany on average during the period from the 2002 to 2018. This is similar to the gap in the Netherlands but more than twice as high as in countries such as Denmark and Sweden where it was around 20% (Figure 3.1). The relatively high gender gap in earnings in Germany reflects a very high gap in hours worked (25%) and an above‑average gap in hourly wages (19%) – see Figure 3.1. A similar picture is observed for the Netherlands which also exhibits a very high gap in hours worked and above‑average gaps in hourly wages. Denmark stands out as the country with the smallest gap in working time, while Sweden stands out as the country with the smallest gap in hourly wages.

Figure 3.1. The role of wages and hours in the gender gap in earnings

1. Decomposition of the gender earnings gap between similarly-skilled women and men into the gap in hourly wages and the gap in working time. The earnings and wage gaps between similarly-skilled women and men are estimated by regressing respectively log earnings and log wages on a gender dummy, education/occupation dummies, flexible earnings-age profiles by gender and decade‑of-birth dummies to control for cohort effects. The hours gap between similarly skilled women and men is obtained by taking the difference between the residual gap in earnings and the residual gap in wages.

2. The gender wage gap for Germany does not reflect the part-time wage penalty since the gender wage gap is measured for full-time workers only. Given evidence in the literature of a substantial part-time wage penalty in Germany, the gender wage gap for all workers is likely to be larger in Germany than shown in the figure (Gallego Granados, Olthaus and Wrohlich, 2019[35]).

Reference period: 2002‑18 for Germany; 2010‑19 for the Netherlands; 2002‑18 for France; 2001‑17 Denmark; and 2002‑17 for Sweden. Average: Simple average across countries shown.

3.2. The gender wage gap within and between firms

3.2.1. About one‑quarter of the gender wage gap in Germany reflects the tendency of women to work in low-wage firms

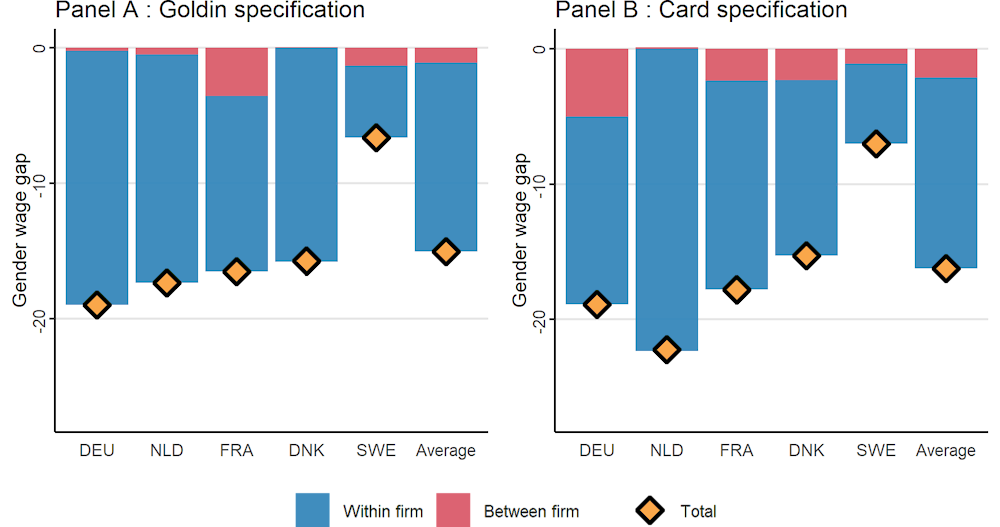

About three‑quarters of the gender gap in average hourly wages between similarly skilled men and women in Germany reflects differences within firms due to differences in tasks, responsibilities and pay for work of equal value. The remaining one‑quarter of the gender wage gap reflects differences in pay between firms is due the sorting of women in low-wage firms (Figure 3.2, AKM specification). This is broadly similar to what is found in previous work for Germany by Bruns (2019[34]), but higher than what is found for nearby countries.

While these results tend to be robust to the use of different specifications in most countries, this is not the case in Germany. The results for Germany highlighted above are based on a specification which controls for unobserved worker characteristics through the inclusion of worker fixed effects, similar to Bruns (2019[34]).1 However, when using the baseline specification that only controls for the observable characteristics of workers (education, age), there is no evidence that sorting contributes to gender wage gap in Germany. This suggests that pay differences between firms in the baseline specification reflect to an important extent unobserved differences in worker composition. Since the interest is here in the role of firms in the gender wage gap while abstracting from compositional differences, the specification that controls for workforce composition through the inclusion of worker fixed effects is preferred.

3.2.2. The between-firm gender wage gap reflects the role of gender segregation in a context of pronounced differences in wage‑setting practices across firms

The relative importance of sorting in the gender wage gap in Germany reflects in part gender segregation across firms, i.e. the concentration of women in firms offering low wages for a given distribution of wage premia dispersion across firms. Segregation across firms is likely to reflect a combination of factors, due to discriminatory hiring practices by employers (demand side) and the preferences of women to work in certain economic activities, the skills these activities require or the way they are organised (supply side). For example, women may be constrained to opt for firms with flexible working-time arrangements due to childcare responsibilities and unpaid homework, but such firms also tend to offer lower wages (Box 3.1).

The relative importance of sorting in the gender wage gap is also likely to reflect the presence of pronounced differences in wage‑setting practices across firms. Indeed, Criscuolo et al. (2020[36]) show that the share of firm wage premia dispersion in overall wage dispersion is highest in Germany among a sample of 20 OECD countries and has increased significantly over time, accounting for much of the increase in overall wage inequality (Criscuolo et al., 2020[36]; Card, Heining and Kline, 2013[37]). The rise in wage‑premia dispersion has also been a key factor behind the slowdown in wage convergence between men and women since the 1990s (Bruns, 2019[34]). Changes in the system of collective bargaining have been identified as one of the drivers of rising wage‑premia dispersion (Card, Heining and Kline, 2013[37]; Bruns, 2019[34]).

3.2.3. Gender segregation across firms in part reflects differences in working-time arrangements, including the availability of part-time work

From a policy perspective, the importance of sorting for the gender wage gap in Germany raises two key challenges. The first is how to make jobs in high-wage firms more accessible to women. Supporting the use of flexible work arrangements across occupations and firms, including part-time work and telework, could help. This would reduce the segregation of women and men across firms and jobs with flexible working-time practices and the contribution of compensating wage differentials to the gender wage gap. The second is how to reduce wage‑premia dispersion across firms. This could involve policies that reduce productivity differences between firms by enabling low-productivity firms to catch-up or exit the market, policies that promote job mobility and strengthening wage‑setting institutions, for example by promoting the use of coverage extensions of sectoral collective agreements or the introduction/revaluation of the statutory minimum wage (OECD, 2021[1]).

Figure 3.2. The gender wage gap between and within firms

Note: Decomposition of gender wage gap between similarly-skilled women and men within firms and between firms using respectively the basic decomposition (Goldin et al., 2017[31]) and the extended decomposition (Card, Cardoso and Kline, 2016[32]) (see Box 2.1 for detail).

The overall wage gap between similarly-skilled men and women is obtained from a regression of log wages on a gender dummy, education/occupation dummies, flexible earnings-experience profiles by gender and decade‑of-birth dummies to control for cohort effects. The wage gap between similarly-skilled women and men differs may differ slightly between the two specifications due to differences in the sample. Reference period: 2002‑18 for Germany; 2010‑19 for the Netherlands; 2002‑18 for France; 2001‑17 for Denmark; and 2002‑17 for Sweden. Average: Simple average across countries shown.

Box 3.1. Firms offering flexible working time arrangements not only employ more women but also tend to pay lower wages

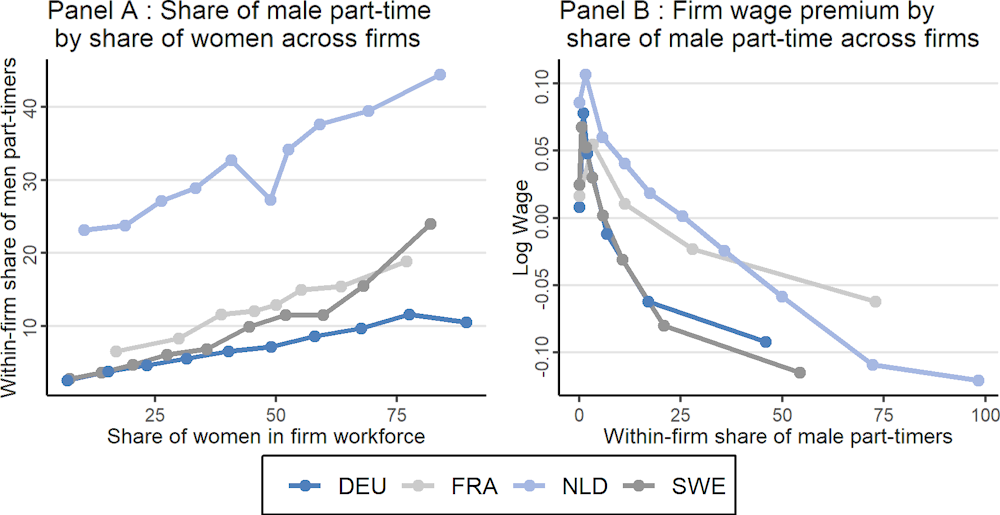

To shed light on the role of flexible working time arrangements for the sorting of women into low-wage firms, Figure 3.3 relates the incidence of part-time work within firms to the corresponding share of women in the workforce (Panel A) and the firm wage premium (Panel B).

Women are more likely to work in firms where part-time work among men is more common (Panel A). In firms with a high share of women (75%) more than 10% of male employees work part-time in Germany, while in firms with a low share of women (25%) less than 5% of males work part-time. A similar pattern is observed for France, the Netherlands and Sweden (the main difference is that part-time work is much more common in all firms in the Netherlands). This suggests that differences in the availability of part-time work across firms along with gendered “preferences” for flexible working-time arrangements contribute to gender segregation across firms.

The prevalence of part-time work is associated with lower firm wage premia (Panel B). In Germany, firm wage premia are about 10% lower in firms with a high share of part-time among male workers (50%) than in firms without any part-time among men. A similar pattern is observed for the other countries. As a result, sorting of women across firms that differ in the scope of working part-time contributes to the between-firm component of the gender wage gap. These findings may indicate that women are willing to accept a lower hourly wage in exchange for the possibility of working part-time (consistent with the theory on compensating differentials).

Figure 3.3. Women are more likely to work in firms where part-time is more common and wages tend to be lower

3.2.4. The within-firm gender pay gap overwhelmingly reflects differences in tasks and responsibilities, while differences in pay for work of equal value within firms are small

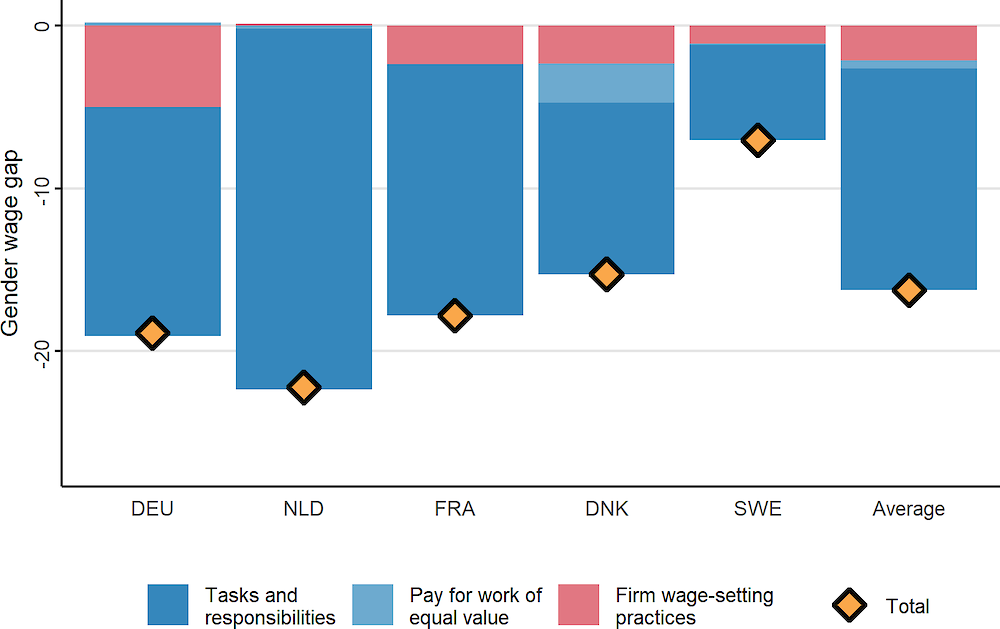

The within-firm gender wage gap in Germany largely reflects differences in tasks and responsibilities, while differences in pay for equal work due to differences in wage bargaining and discrimination appear negligible. A similar pattern is observed for France, the Netherlands and Sweden, whereas differences in pay for work of equal value may be somewhat more important in Denmark (Figure 3.4).2 These findings are based on the “detailed decomposition” as proposed by Card, Cardoso and Kline (2016[32]) and discussed in Box 2.1. This not only considers differences in wage‑setting practices across firms as in the “basic decomposition” (sorting), but also differences in firm wage‑setting practices between women and men within firms due to differences in bargaining strength between women and men or wage discrimination by employers. Previous studies for Germany by Bruns (2019[34]) and France by Coudin et al (2018[38]) using a similar methodology provide similar findings.3 While differences in pay for work of equal value may be small in Germany, the present estimates are best considered as lower bounds (see Box 3.2).

Figure 3.4. The role of differences in tasks and responsibilities, pay for work of equal value and firm wage‑setting practices in the gender wage gap

Note: Detailed decomposition of gender wage gap between similarly-skilled women and men in components related to differences in tasks and responsibilities, pay for work of equal value and firm wage‑setting practices (see Box 2.1 for details). The overall wage gap between similarly-skilled women and men is obtained from a regression of log wages on a gender dummy, education/occupation dummies, flexible earnings-experience profiles and decade‑of-birth dummies to control for cohort effects. Reference period: 2002‑18 for Germany; 2010‑19 for the Netherlands; 2002‑18 for France; 2001‑17 Denmark; and 2002‑17 for Sweden. Average: Simple average across countries shown.

Box 3.2. Technical discussion: How are differences in pay for work of equal value measured?

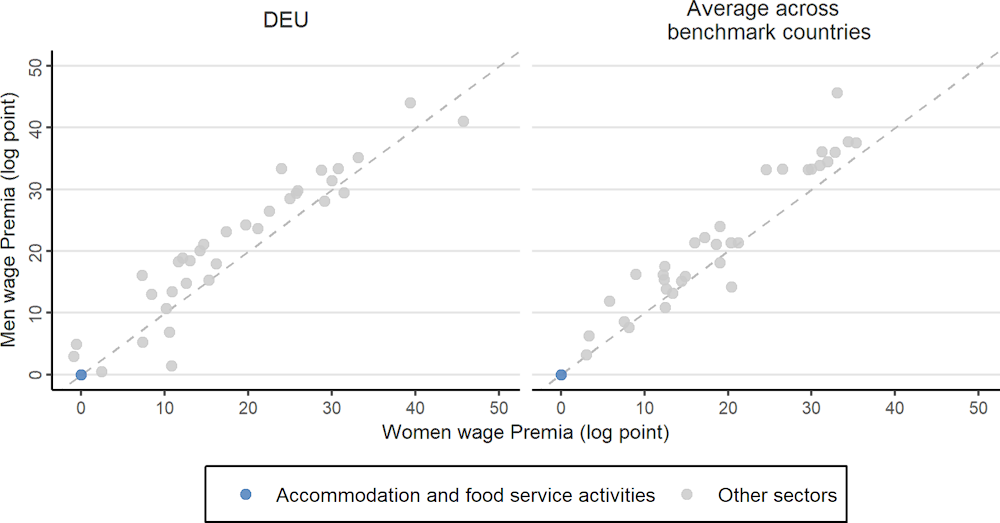

Differences in pay for work of equal value are analysed by comparing the firm-fixed effects for men and women in the same firm. Since the firm-fixed effects are only identified up to a constant this requires making a normalisation assumption that allows focusing on relative differences in firm wage premia between men and women across firms. Following Card et al. (2016[32]), this is achieved by assuming that there is a reference sector in which there are no rents to be shared with workers (firm wage premia are zero) and hence there are no differences in pay for work of equal value (no differences in wage premia between men and women within firms). The reference sector is accommodation and food services as firm wage premia in this sector tend to be lower than in other sectors in Germany as well as in the benchmark countries (Figure 3.5). However, this does not necessarily mean that there are no rents at all in the accommodation and food-services sector and consequently that there are no differences in firm wage premia or pay for work of equal value between men and women within firms. As a result, the component associated with differences in pay for work of equal value is likely to be underestimated.

Figure 3.5. Firm wage premia tend to be low in the accommodation and food services sector

Note: The plot represents the average firm-fixed effects by industry for men and women. The gender-specific firm-fixed effect are recovered from a wage regression with individual fixed effects and a flexible gender specific earnings-experience as additional controls. The firm-fixed effects are normalised with respect to the average in the accommodation and food services sector for which the firm-fixed effects are set to zero.

3.2.5. Promoting equal opportunities for career progression is key

The main implication for policy is that to reduce the gender wage gap it is crucial to promote equal opportunities for career progression. Unequal opportunities for career progression within firms may result from a broad range of factors, including discrimination in hires and promotions by employers and the individual circumstances of men and women, related to the unequal sharing of family responsibilities, that may constrain career choices and shape preferences for non-wage working conditions (e.g. flexible hours, short commuting times). To better understand how to foster more equal opportunities for career advancement, Chapter 5 analyses job mobility patterns within and between firms using a dynamic perspective.

3.2.6. Pay transparency measures can help raise awareness about systematic differences in pay within firms

Even if differences in pay for work of equal value are small, this does not imply that pay transparency measures, such as those recently introduced in Germany, do not have an important role to play (OECD, 2021[23]). While such measures are to an important extent motivated by the objective of tackling wage discrimination, pay transparency measures do not usually focus on pay for equal work, but rather systematic pay differences within firms, with only very limited attention given to differences in qualifications, tasks and responsibilities. Indeed, their objective is to raise awareness about systematic pay differences within firms and create discussion about their underlying sources (Chapter 6). The hope is that by questioning the adequacy of a firms’ existing remuneration, recruitment and promotion policies this would promote the adoption of more gender-friendly human-resource frameworks. It is crucial that the evaluation of pay transparency measures also takes account of these broader policy objectives related to recruitment and promotion.

3.3. The gender wage gap along the wage distribution

The between-firm and within-firm components of the gender wage gap may vary for workers for different wages or skills. To shed light on this issue, the decomposition of the gender wage gap between and within firms is implemented according to the (time‑invariant) level of transferable skills of men and women measured using workers fixed effects in wages.

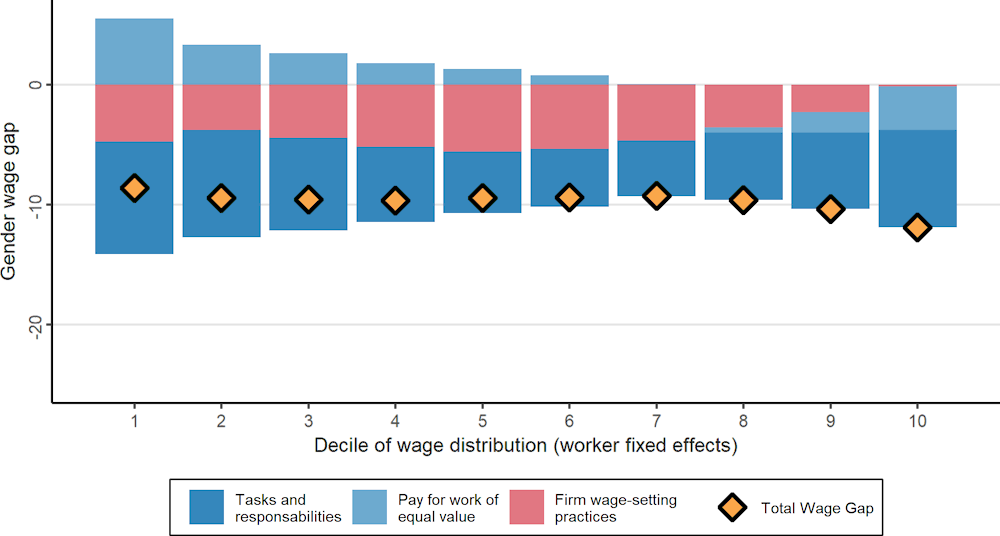

3.3.1. The within-firm gender wage gap is larger for workers with higher levels of transferable skills

In Germany, the wage gap between similarly skilled men and women is about 50% higher for workers with high levels of transferable skills than workers with low to medium levels (Figure 3.6). A qualitatively similar picture tends to be observed in other OECD countries (OECD, 2017[39]). The larger gap in pay for workers with high skills largely reflects the greater importance of differences in pay for work of equal value due to differences in worker bargaining power or employer discrimination. By contrast, the role of sorting across firms appears to be less important for workers with high transferable skills and more important for workers with low transferable skills. Differences in tasks and responsibilities are particularly important for workers with either low or high skills, but less so for workers with medium levels of skills. Part of the high gender wage gap for high-skilled women reflects limited access to top jobs.

Figure 3.6. The role of differences in tasks and responsibilities, pay for work of equal value and firm wage‑setting practices along the wage distribution

Note: Decomposition of gender gap along the distribution of worker fixed effects in components related to differences in tasks and responsibilities, pay for work of equal value and firm wage‑setting practices (see Box 2.1 for detail). The overall wage gap between similarly-skilled women and men is obtained from a regression of log wages on a gender dummy, education dummies, flexible earnings-experience profiles and decade‑of-birth dummies to control for cohort effects. Reference period: 2002‑18 for Germany.

3.3.2. Enhancing women representation on company boards

Gender quotas and voluntary target setting can help to promote the representation of women on company boards. While legally binding quotas may be more effective in increasing women’s representation in the short term, they need to be used judiciously to avoid the risk that they undermine firm performance, particularly if targets are set too high given the number of suitably-qualified women in the sector/occupation (Hwang, Shivdasani and Simintzi, 2018[40]). Finely targeted quotas such as those related to company boards seem to hold some promise in this regard. Recent evaluations suggest that such quotas enhance the representation of women in company boards, but also that they have limited spill over effects on the career progression of other women in those firms (Bertrand et al., 2019[41]; Maida and Weber, 2020[42]).

Notes

← 1. The importance of sorting is very similar when estimating wage regressions with worker and firm-fixed effects as in Abowd et al. (1999[45]) or when estimating them separately for men and women as in Card et al. (2016[32]) and as done in Figure 3.2 and Figure 3.4.

← 2. The low pay gap due to differences in tasks and responsibilities in Sweden is consistent with the relatively high share in managerial positions. This was 42% in Sweden in 2020 compared with around 28% in Denmark and Germany (OECD, 2020[94]).

← 3. A larger role for bargaining and discrimination has been documented for other countries such as Estonia and Portugal (Card, Cardoso and Kline, 2016[32]; Masso, Meriküll and Vahter, 2021[93]; OECD, 2021[1]).