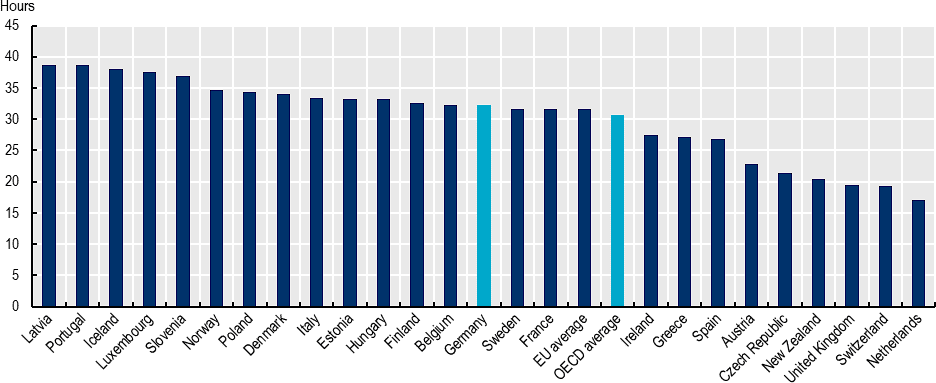

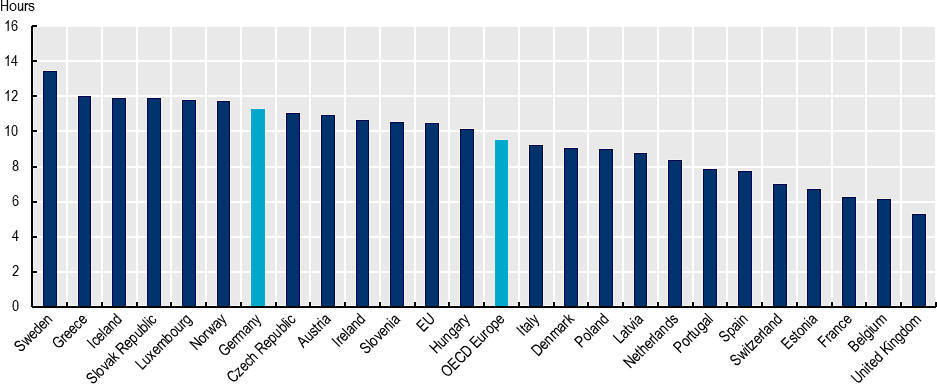

Although the wage gap between similarly skilled men and women increases rapidly around the age when children arrive, considerable wage gaps remain into later working lives. These are linked with significant gaps in hours worked between similarly skilled men and women that grow around the age families have children and remain large through to older ages (as opposed to slight recoveries observed in countries like Denmark).

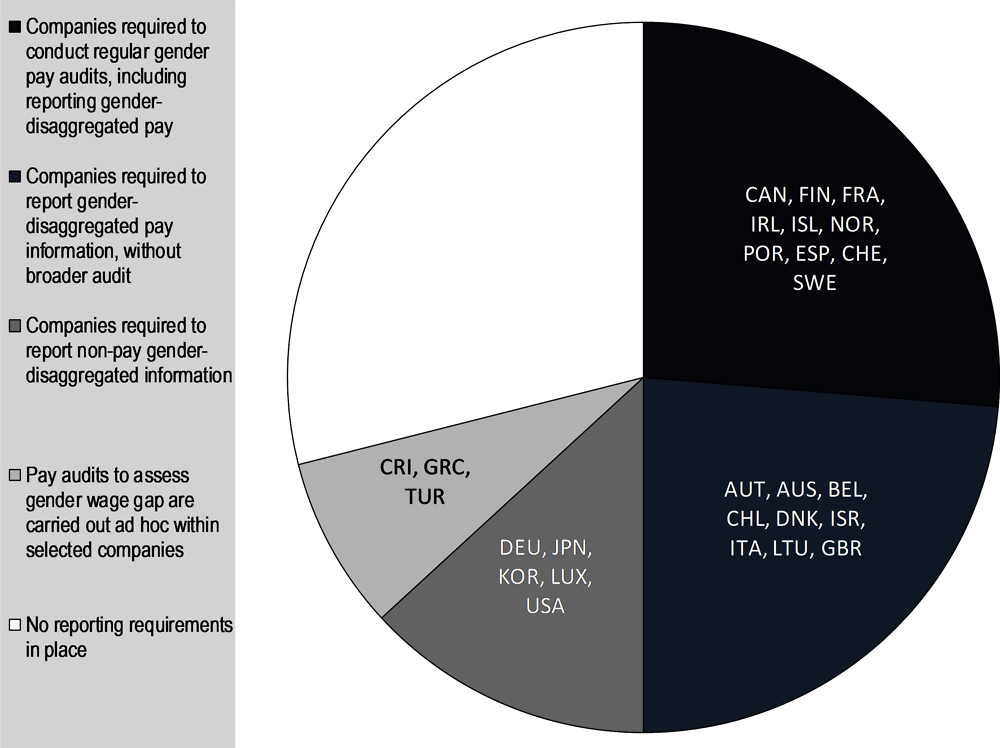

There are elements in the Tax-Benefit system in Germany that support a “one‑and-a-half-earner model” of family income. The system means that the financial incentives to work more hours are greater for the higher-earning partner than the lower-earning partner. Married couples and civil partners can file their taxes together, with joint liability for the aggregated income of the couple (“Ehegattensplitting”). The result is that the couple can jointly be taxed at a lower marginal rate than they would have been if the higher-earner partner had filed taxes on their own (due to progressive tax schedules). If there are large differences in earnings, joint liability reduces the overall tax payment but increases the marginal tax rate for the lower-earning partner (Bachmann, Jäger and Jessen, 2021[19]).

The joint taxation of income with spousal splitting leads to a significantly higher burden for second earners compared to individual taxation. When labour income of couples is sufficiently different between the spouses, the tax filing system that optimises household income allocates the basic tax-free allowance for which no income tax has to be paid to the higher earner. While this yields an overall tax burden that is lowest for the household, the spouse with lower earnings faces a disproportionate share of the tax burden. This is the case because the spouse with lower earnings pays income tax on even low earnings and reaches higher tax bracket thresholds earlier, leading to higher marginal and effective tax rates for the second earner. To illustrate this point, for a taxable income of EUR 45 000 per year, which after standard deductions corresponds to the average income of (male) full-time employees in 2020 (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2021[73]), the first earner pays a marginal tax rate of just over 27% and an average tax rate of just under 13% on their taxable income. For the second earner in this couple, starting at a taxable income of EUR 8 000, the marginal and average tax burden rises steeply. With an annual gross wage of EUR 20 000 to 35 000, which corresponds to the range of most second-earners, the marginal tax rate is consistently 42%, while the average tax rate is between 20% and 30% (Bach, Haan and Wrohlich, 2022[74]). This has been identified as an important reason for the relatively low volume of work of married women in Germany (Blömer, Brandt and Peichl, 2021[75]).

While the Tax-Benefit system does not explicitly target women as second earners, female working spouses are disproportionately considered as such. Since female spouses’ earnings tend to be lower than their male counterparts’, many families face lower incentives to plan for wives working full-time work (OECD, 2017[3]). There are several reasons for this. First, age gaps in relationships often mean that female spouses have been working for a shorter period of time than their partners and therefore tend to be the lower-earning spouse (Schmidt and Stettes, 2021[76]; OECD, 2017[3]). Second, women are still allocated the heaviest burden of unpaid work in the household (OECD, 2021[77]). Third, cultural beliefs that men and women should engage in separate spheres according to a traditional breadwinner-homemaker model are still prevalent (albeit waning) in Germany, and especially in western Germany (Grunow, Begall and Buchler, 2018[50]).

The new government has announced plans to reform the joint taxation system, but effects are yet to materialise. The coalition agreement spells out the intention to remove the current option of being able to transfer the basic tax-free allowance between spouses to avoid these negative consequences for second earners (SPD, BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN and FDP, 2021[78]). The new proposal would still offer benefits for married couples, but distributes them equally with a factor that is calculated based on the share of the income provided by each partner. This will increase the marginal tax rate for main earners and reduce it for second earners. This reform would increase incentives for second earners – mainly women – to enter the labour market or increase their hours. Modelling of these reforms has pointed out that this is a step in the right direction, but that for incentives to be strengthened further, the splitting model has to be reformed (Bach, Haan and Wrohlich, 2022[74]). It remains to be seen whether these reforms will be sufficient to increase female hours in paid work. To further limit the impact of joint family taxation, Germany could introduce a tax-free allowance unique to second earners and consider reforms to the co‑insurance system for spouses of workers (see OECD (2017[3]).