This chapter seeks to shed more light on the role of motherhood in the age profile of the gender wage gap. Since the present cross-country data do not allow looking at the role of motherhood directly due to the absence of information on childbirth, the chapter takes an indirect approach based on the analysis of career breaks, defined as non-employment spells around the age of parenthood (25‑34). Career breaks account for a potentially important fraction of the motherhood penalty, i.e. the shortfall in wage growth following childbirth of mothers relative to fathers, and as a result, the evolution of the gender wage gap within and between firms over the working life.

The Role of Firms in the Gender Wage Gap in Germany

5. The role of career breaks in the gender gap within and between firms

5.1. The incidence and duration of career breaks

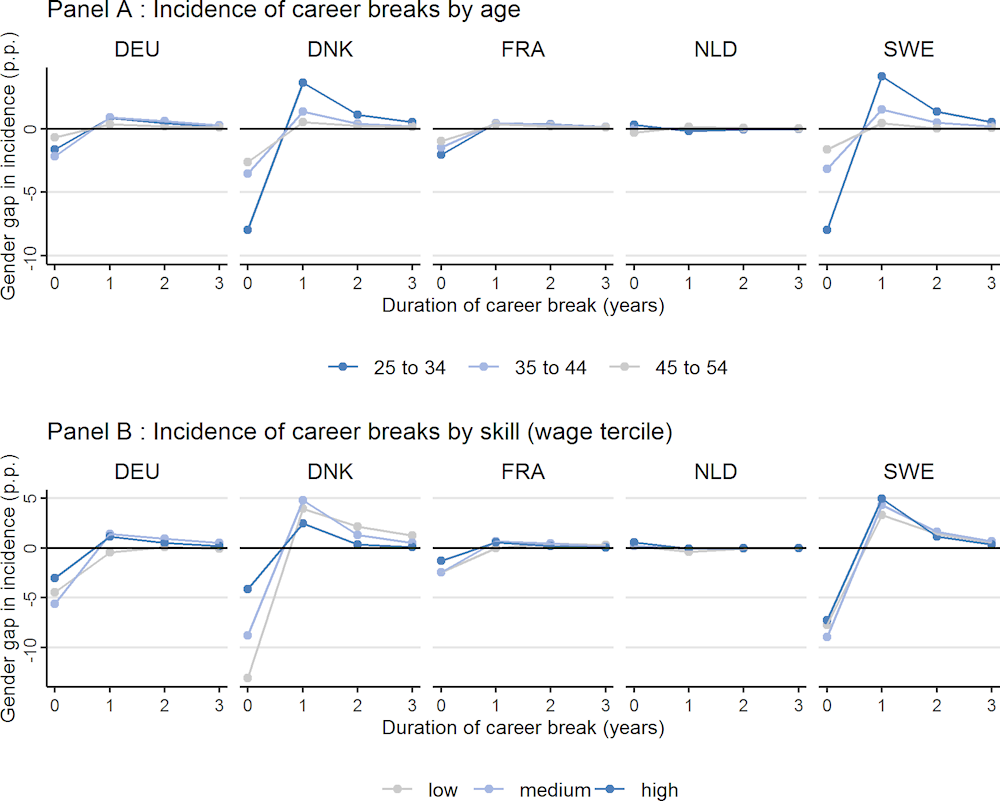

For each of the countries considered, women aged 25‑34 tend to be more likely than men to experience a non-employment spell of one or more years, while gender differences between older workers tend to be negligible (Figure 5.1, Panel A). While non-employment spells may reflect many factors, the difference between women and men for workers aged 25‑34 is likely to be driven by mothers who take a career break following childbirth.

5.1.1. Career breaks are most common along low-skilled women in Germany

In Germany, the gender gap in career breaks is modest, similar to the level observed in France (Figure 5.1). Career breaks are considerably more common in Denmark and Sweden and tend to last longer, while career breaks in the Netherlands are rare (or are more equally shared between men and women). Among women aged 25‑34, low and middle skilled women are more likely to take a career break in Germany and Denmark than more skilled women. This may reflect different factors including the opportunity costs of not working which are more important for high-skilled women.

Figure 5.1. Career breaks in Germany are most common among young women with low skills

Note: Reference period: 2002‑18 for Germany (full-time and part-time workers); 2010‑19 for the Netherlands; 2002‑18 for France; 2001‑17 Denmark; 2002‑17 for Sweden. Skill groups are defined in terms of terciles of the wage distribution by gender and year of birth.

5.2. The short-term wage effects of career breaks

Career breaks could have important implications for the earnings of women as well as their longer-term professional careers. Earnings losses may result from either a reduction in working time as women move into part-time work following a career break or a reduction in the hourly wage due to their slower upward mobility within firms or their sorting into lower wage firms.

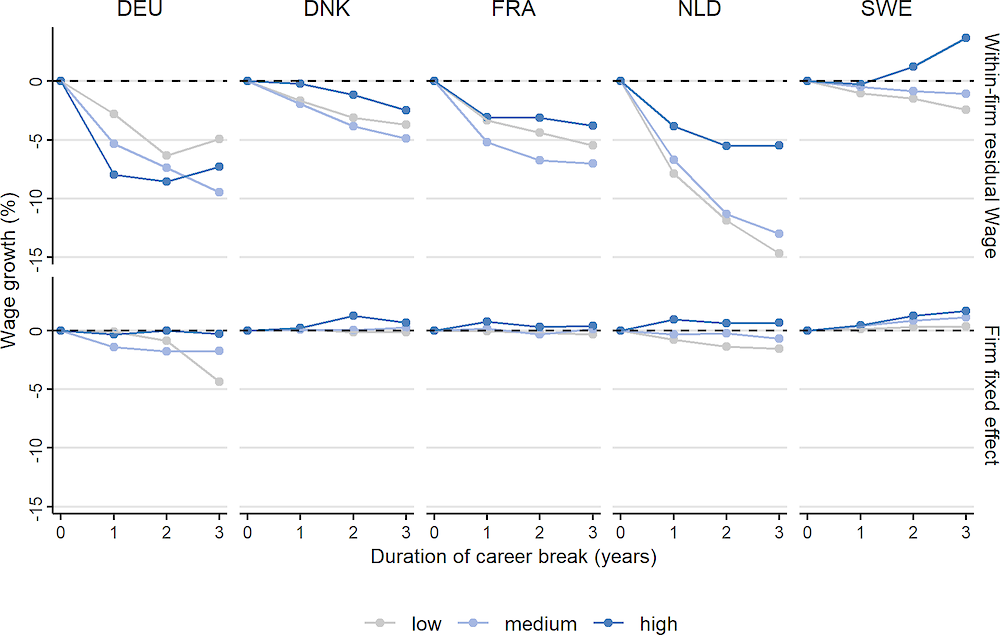

5.2.1. Career breaks carry considerable earnings losses in Germany due to lower hourly wage growth as well as the shift to part-time work

Career breaks slow earnings growth within firms (Figure 5.2, top panel). The evidence suggests that hourly wage losses due to missed experience or human capital depreciation in Germany are sizeable and amount to about 5% for career breaks of one year, roughly in line with previous findings in Boll and Leppin (2015[49]). There is a quite bit of variation in the size of wage losses across the benchmark countries – partly due to the role of small sample sizes in some countries –, with larger wage losses observed in the Netherlands (where career breaks are rare) and smaller wage losses in Denmark, France and Sweden. In part, these differences are likely to reflect the likelihood with which women move to part-time work following career breaks. Part-time among mothers with children (0‑14 years old) is much more common in the Netherlands (50%) than in Sweden (9%), Denmark (9%) and France (15%) (OECD, 2022[16]). When allowing for changes in working time in Germany, earnings losses are substantially larger, particularly for low and medium-skilled workers (Box 5.1). This suggests that many lower and medium-skilled workers do not return to full-time work after a career break.

There is some indication that low-skilled women move to lower-wage firms following a career break in Germany (bottom panel). Previous work for Germany by Bruns (2019[34]) suggests that the effects of sorting following childbirth may be even more significant, accounting for a quarter of the long-term wage penalty associated with motherhood. The present analysis may only capture the effects of sorting to a limited extent as many of the women sorting into lower-wage firms in Germany may do so without taking a career break, while many of the women taking a career break may actually return to their previous employer. In other countries, there is little evidence that career breaks lead to the sorting of women into lower wage firms.1

Figure 5.2. Career breaks tend to be associated with significant wage losses

Note: Germany: full-time women aged 25 to 34. Reference period: 2002‑18 for Germany 2010‑19 for the Netherlands; 2002‑18 for France; 2001‑17 Denmark; 2002‑17 for Sweden.

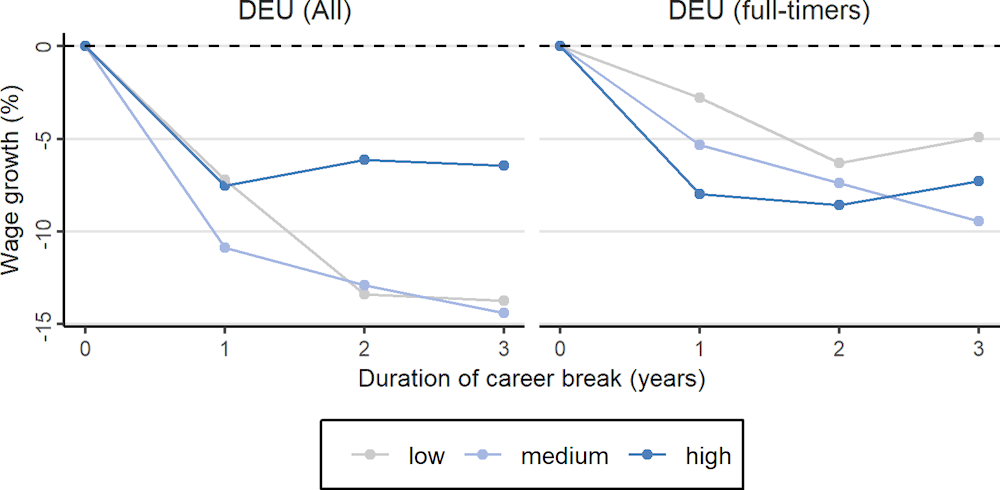

Box 5.1. The short-term earnings losses of career breaks in Germany

Career breaks may lead to earnings losses because of their implications for wage growth but also because women switch to part-time following a career break to facilitate combining work and child-care responsibilities. To shed some light on this issue, the analysis for Germany is repeated for all workers, including those working part-time, and compared with that for full-time workers as in the main text (Figure 5.3). This suggests that within-firm earnings losses are considerably larger when taking account of changes in working time, particularly among low and medium-skilled women. While the short-term earnings associated with career breaks for high-skilled women amount to about 5%, for low and medium skilled women, these are around 10%.

Figure 5.3. The short-term earnings losses of career breaks

Note: Women aged 25 to 34 – DEU (full-timers): full-time workers only DEU (All): full-time and part-time workers.

5.2.2. Both policies and institutions and social norms are likely to shape the incidence and nature of career breaks

Further analysis based on a larger sample of countries documented in OECD (2021[1]) reveals large differences in the incidence and duration of career breaks across Eastern, Northern, Western European countries, which suggest that family policies such as child-care, parental leave, working-time regulations, but also the broader institutional set-up in relation to for example employment protection and collective bargaining have a significant impact. However, these cross-country patterns may also in part reflect deeply engrained cultural differences between countries in the form of social norms. For instance, traditional gender norms, which favour a predominantly female provision of care work, are substantially more common among men and women in Germany than in Sweden and the Netherlands (Grunow, Begall and Buchler, 2018[50]) and particularly so in Western Germany (Bauernschuster and Rainer, 2011[51]).2 Career breaks around motherhood are more widespread in Western Germany and associated with larger earnings losses (Box 5.2). The importance of social norms suggests that family policies need to be complemented with other policies that can help foster gender-friendly social norms (e.g. school interventions).

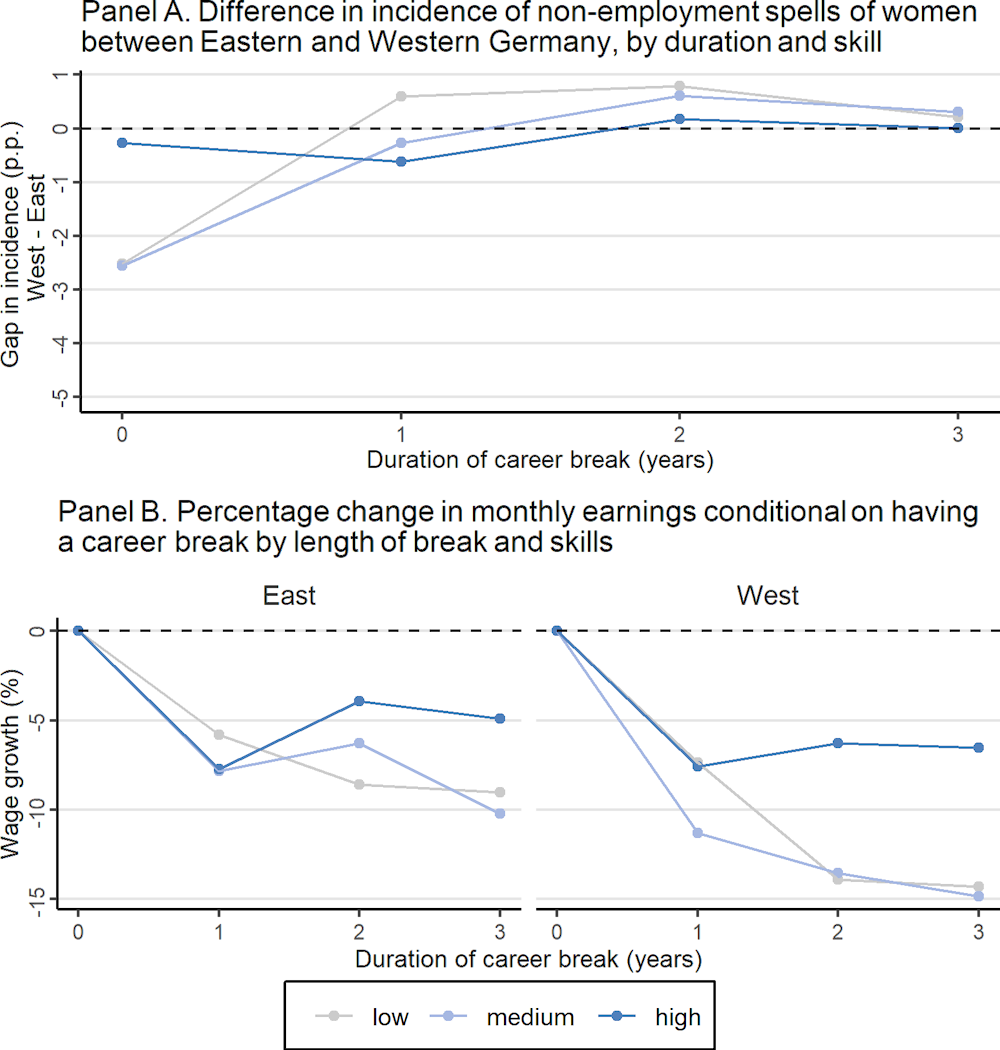

Box 5.2. Gender norms and career breaks: A comparison of Eastern and Western Germany

Enduring differences in social and cultural norms between the eastern and western parts of Germany are a well-documented aspect of German society. For example, Bauernschuster and Rainer (2011[51]) show that, in 2008, almost 20 years after reunification, individuals in eastern Germany hold significantly more egalitarian gender attitudes than their western counterparts. These differences have been found to contribute to the motherhood penalty, which is particularly acute in western Germany (Collischon, Eberl and Reichelt, 2020[52]).

Career breaks are more common in western Germany and have potentially more significant consequences for earnings (Figure 5.4). The difference in career breaks is particularly pronounced among low- and medium-skilled women, while the gap is negligible for high-skilled women. Earnings losses also tend to be more pronounced in Western Germany due to the tendency of women to switch to part-time work after returning from a career break, particularly among low and medium skilled women.

Figure 5.4. Career breaks around motherhood are more widespread in western Germany and associated with larger earnings losses

Note: All women aged 25 to 34 including part-time. Eastern and Western Germany are defined using the place of work. Reference period: 2002‑18 for Germany.

Notes

← 1. Coudin et al. (2018[38]) found for France that the motherhood penalty in wages is closely related to the tendency of young mothers to move to firms close to home and firms with flexible working-time policies.

← 2. Evidence for Denmark also shows that the motherhood penalty is highly persistent over time and tends to be transmitted across generations (Kleven et al., 2019[44]).