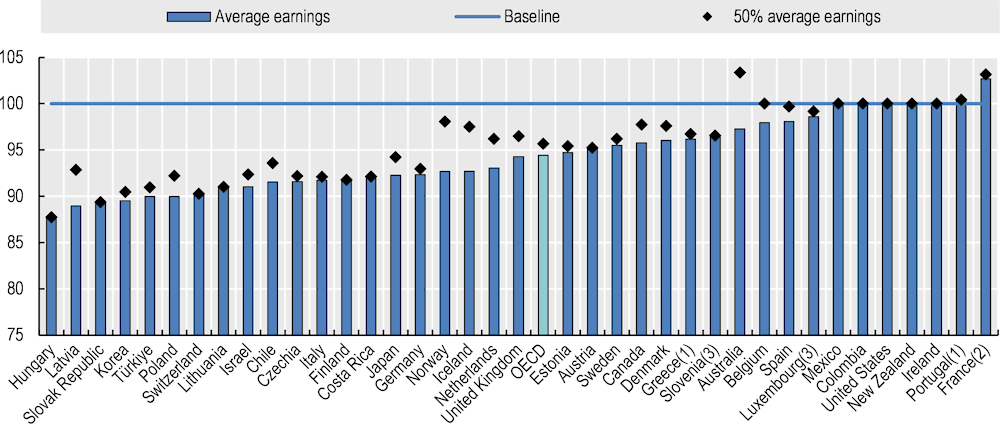

Whilst starting late reduces earnings-related pensions, periods of unemployment normally provide some pension protection through credited years of contribution for example. In addition, residence‑based and contributory minimum pensions help cushion the impact of unemployment breaks. This indicator shows how these career breaks affect future pension entitlements. Workers with average earnings and having five years out of the labour market due to unemployment will have a pension equal to 94% of that of a full-career worker on average across the 38 OECD countries. Benefits are below 90% of the full-career worker in Hungary, Korea, Latvia and the Slovak Republic as there is limited credit provided to cushion the impact of the break.

Pensions at a Glance 2023

Impact of unemployment breaks on pension entitlements

Key results

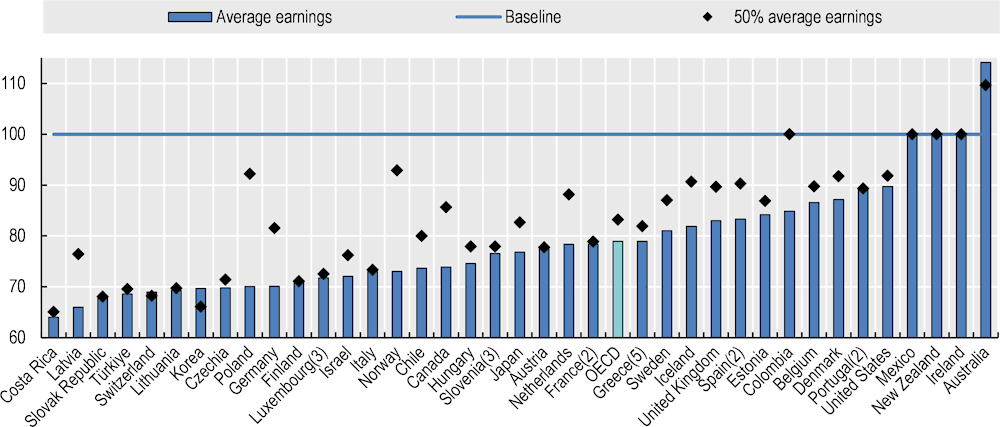

Most OECD countries provide some degree of unemployment credit for at least an initial period. On average five years of unemployment will result in a pension of 94% of that of a full-career worker for the average‑wage case. When starting the career 5 years later and then having a period of 10 years of unemployment during the career, this falls to 79%, with both scenarios leading to a higher required retirement age in a few countries. For low earners, the impact of these two career-break cases on pensions is slightly lower, with a relative pension of 95% and 83%, respectively, compared with the full-career baseline. Compared with a full-career worker in a country with a normal retirement age of 66 for example, these 5‑ and 15‑year missing years represent about 11.5% and 34% of the career length, respectively. Without any protection, these shares would provide an order of magnitude of the expected negative impacts of these breaks on pensions.

For the average‑wage worker, pension shortfalls relative to someone with a full, unbroken career varies widely across countries. They are larger for longer duration of career absence and for high earners. In Hungary, Korea, Latvia and the Slovak Republic the pension loss after a five‑year unemployment break is around 11% or more as only the first year is partially covered in Hungary and Latvia, with no credit at all in the Slovak Republic and with Korea providing full credit for the first year only, based on last earnings.

In other countries, pension rules can fully offset the fallout from spells of unemployment. This applies for example in Ireland, Spain and the United States. In Spain and the United States, this is because total accrual rates and the reference wage used to compute benefits are not affected – for example, pension entitlements stop accruing in Spain and the United States after 38.5 – which on top take only part of the career to calculate the reference wage – and 35 years, respectively. In Ireland, this is because such a break does not affect the contribution-based basic pension level. In New Zealand, as well, periods of unemployment do not affect the basic pension as it is entirely residence based. The Netherlands’ residence‑based basic pension provides a constant level of benefit irrespective of unemployment periods but the occupational pension is sharply reduced by unemployment breaks. In Australia and Iceland, although there is no protection in the FDC pension schemes, both countries have basic pensions that are gradually withdrawn against other income, so whilst this does not provide protection for the five‑year case it does cushion the impact of the longer unemployment break scenario.

In Greece, Luxembourg and Slovenia the loss in future benefits is small but the individual needs to work one, three and three years longer, respectively, to get a full pension (i.e. without penalty). For Greece and Slovenia, the limited loss is also due to the indexation of benefits in payment, as the full-career worker will have been receiving pensions indexed below wage growth, therefore declining in relative terms. Average‑wage workers have to retire later to benefit from a full pension after experiencing a five‑year unemployment break in France and Portugal as well due to the required contribution rules and in both cases the benefit level is slightly above 100% of the full career case.

There are countries which afford low-paid workers better protection against long-term unemployment than average earners, because contributory minimum pensions and resource‑tested schemes play a crucial role – Australia, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Iceland, Mexico, Norway and Poland. By contrast, lower earners in Germany are more affected by the longer unemployment break than average earners, as low earners then lose their entitlement to the supplemental component of the pension due to their shorter contribution period.

Definition and measurement

For the unemployment career case, men are assumed to embark on their careers as full-time employees at 22 or 27 for the late entry case, and to stop working during a break of up to ten years from age 35 due to unemployment; they are then assumed to resume full-time work until normal retirement age, which may increase because of the career break. Any increase in retirement age is shown in brackets after the country name on the charts, with the corresponding benefits for the full career worker indexed until this age. The simulations are based on parameters and rules set out in the online “Country Profiles” available at http://oe.cd/pag.

Figure 5.1. Gross pension entitlements of low and average earners with a 5‑year unemployment break versus worker with a full career

Note: Figure in brackets refers to increase in retirement age due to the career break. Individuals enter the labour market at age 22 in 2020. The unemployment break starts in 2033. Low earners in Colombia, New Zealand and Slovenia are at 64%, 63% and 56% of average earnings, respectively, to account for the minimum wage level.

Source: OECD pension models.

Figure 5.2. Gross pension entitlements of low and average earners with a 10‑year unemployment break after entering the labour market 5 years later

Note: Figure in brackets refers to increase in retirement age due to the career break. Individuals enter the labour market at age 27 in 2025. The unemployment break starts in 2033. Low earners in Colombia, New Zealand and Slovenia are at 64%, 63% and 56% of average earnings, respectively, to account for the minimum wage level.

Source: OECD pension models.