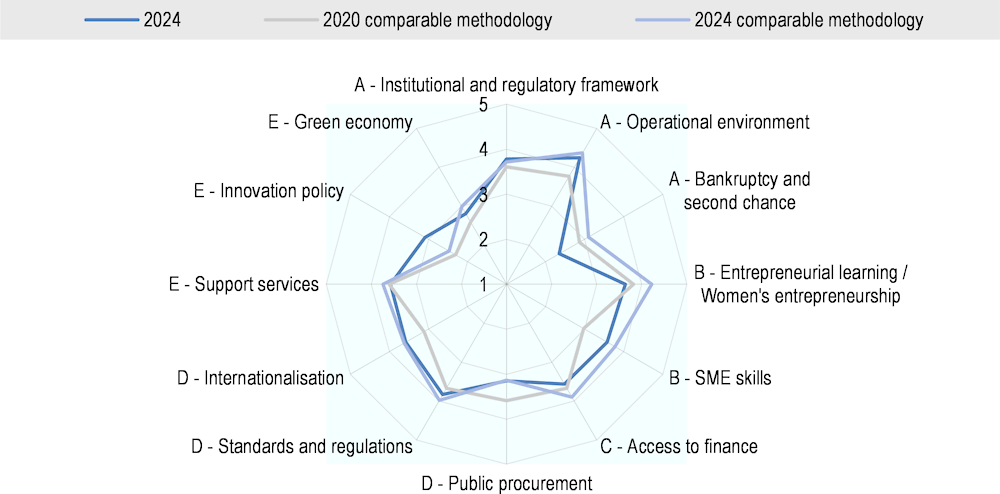

This section provides an overview of key findings of the 2024 Small Business Act for Europe (SBA) assessment for all Eastern Partner (EaP) countries across the dimensions of the five thematic pillars and the selected framework conditions for the digital transformation, as well as key findings for each country. A detailed analysis and cross-country comparison of each pillar and dimension is presented in Part I of this report, while Part II contains full country profiles. Complete scores per dimension, sub-dimension, and thematic block found in Table 2.22 at the end of this chapter. The scoring methodology is presented in Annex A.

SME Policy Index: Eastern Partner Countries 2024

2. Overview: 2024 SME Policy Index scores and key findings

Overview of 2024 key findings for Eastern Partner countries

Key findings by pillar

Digital Economy for SMEs

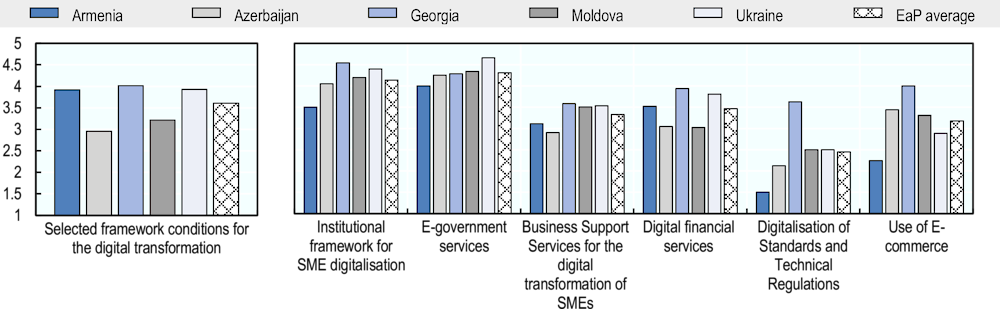

Because of the increasing and strategic importance of the topic, this new round of the SBA assessment entails a new section dedicated to the digital transformation. A pillar on selected framework conditions for the digital transformation has been added, assessing national digital strategies and measures for broadband connectivity and digital skills, while pre-existing pillars contain digitalisation-oriented sub-dimensions. The OECD calculated a weighted average of the scores for each of these aspects, resulting in overall composite scores for SME digitalisation policies (Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1. Composite scores for SME digitalisation policies in EaP countries, by component

Note: See the “Policy framework, structure of the report and assessment process” chapter and Annex A for information on the assessment methodology.

Table 2.1. Performance in selected framework conditions for the digital transformation

|

Selected framework conditions for the digital transformation |

Armenia |

Azerbaijan |

Georgia |

Moldova |

Ukraine |

EaP average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2024 scores |

3.92 |

2.96 |

4.02 |

3.22 |

3.93 |

3.61 |

Note: See the “Policy framework, structure of the report and assessment process” chapter and Annex A for information on the assessment methodology.

The section below summarises the main findings of the assessment of selected framework conditions for the digital transformation, examining i) the overall policy framework for the digital transformation, including the national digital strategy or its equivalent; ii) broadband connectivity; and iii) digital skills.

National Digital Strategy

National digital strategies allow governments to outline their approaches to a topic by listing their policy priorities and objectives in this regard. These strategies can help countries accelerate the digital transformation of their economies and societies by ensuring a comprehensive policy approach and facilitating co-ordination among various stakeholders (Gierten and Lesher, 2022[1]).

EaP countries have prioritised the integration of digitalisation into their policies and have been developing policy frameworks to achieve this, although these differ in nature and scope. Among them, Armenia stands as the only country in the region to have already adopted a National Digital Strategy (NDS), the Digitalisation Strategy of Armenia for 2021-25. Meanwhile, Azerbaijan, Georgia and Moldova have formulated similar multi-year strategies, but these are awaiting approval and are expected to be adopted by the end of 2023. Policy objectives related to digitalisation are currently dispersed across different policy documents, including overarching country strategies like in Azerbaijan and Georgia, or an innovation strategy for Moldova. Georgia has also incorporated digitalisation-related provisions in its ongoing broadband and SME strategies. Finally, Ukraine has embedded its strategic vision for digital transformation in several governmental documents1, including the National Economic Strategy 2030.

However, the current policy documents for the digital transformation allocate limited attention to the digitalisation of SMEs in non-IT sectors. Armenia’s NDS includes provisions to expedite SME digitalisation, particularly by raising the private sector’s awareness about digital tools, promoting businesses’ use of new technologies, and further advancing e-commerce and innovative solutions. Other EaP countries have outlined a few measures in these strategies, yet these remain limited and often revolve around digital skills.

Regarding policy governance, all EaP countries have put forth efforts to establish multi-stakeholder approaches. The formulation of strategic policy documents for digitalisation has benefitted from contributions from various actors. Typically, this involves the establishment of dedicated working groups comprised of ministries, public agencies, international experts (consulting firms and/or international organisations), and sometimes businesses and business associations. These mechanisms, along with the clear designation of leading stakeholders for the NDS, have facilitated co-ordination among these actors.

One of the main weaknesses for most EaP countries remains the deficiency in data collection related to digital transformation, which impedes monitoring and evaluation practices. Besides insights on broadband connectivity, statistical offices only collect a limited number of indicators, and this rarely covers businesses’ adoption and use of digital tools. In this context, Georgia and Ukraine appear as frontrunners and Azerbaijan has recently made substantial progress. Nonetheless, more could be done to align with OECD and EU databases and methodologies. Current policy documents lack quantifiable targets to assess progress, such as advancements in digital skills development and SME digitalisation.

EaP countries could strengthen their policy frameworks for the digital transformation by:

Consolidating policy approaches to digitalisation and ensuring co-ordination throughout implementation: EaP countries should adopt comprehensive NDSs that outline clear objectives, measurable targets, and budgets. Successful implementation will require the involvement and co-ordination of all relevant public and private stakeholders.

Promoting inclusive SME digitalisation: Policymakers must include provisions for digitalisation in small non-IT businesses, fostering both technology adoption and digital culture.

Ensuring effective monitoring and evaluation: Countries should collect more data on the digital transformation to foster evidence-based policymaking and efficient impact evaluation.

Broadband connectivity

A crucial prerequisite for economies and societies to harness the potential of digital transformation lies in securing Internet access that is efficient, affordable and dependable. Not only do some OECD countries acknowledge this as a fundamental right, but it is also listed as one of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Over the past years, broadband adoption has been steadily increasing in EaP countries, although significant disparities remain. Georgia stands out as the most connected EaP country, while Ukraine has demonstrated significant progress, witnessing a remarkable increase of 52% in fixed subscriptions and 254% in active mobile subscriptions between 2016 and 2021. However, despite this advancement, connectivity levels in the EaP region still fall short of the benchmarks set by both the OECD and the EU.

The quality of broadband is another critical factor for enabling individuals and businesses across the EaP region to fully benefit from digitalisation. However, recent data underscores persisting regional disparities. For example, while Moldova and Ukraine benefit from a good connection speed – one that is comparable to OECD and EU levels – Azerbaijan grapples with Internet speed challenges.

Moreover, affordability remains a concern. Although ICT prices are among the cheapest in the world in absolute terms, a comparison of tariffs as a percentage of gross national income (GNI) per capita reveals that Internet access remains relatively less affordable in the EaP region than in OECD and EU countries, particularly for fixed broadband. In 2021, Armenia, Georgia and Moldova still exceeded the ITU’s 2% threshold.2 This affordability challenge can hinder business uptake, especially in conducting online operations that require robust, fast and dependable connections, a demand which fixed broadband is better suited to meet.

Data remains scarce across EaP countries regarding broadband uptake among businesses. Only Georgia and Ukraine have collected such indicators, revealing that firms’ connectivity in their territories lags behind that of OECD and EU countries. The gap in connectivity between SMEs and large enterprises is also more pronounced: For instance, in Ukraine, 84.5% of small firms have access to the Internet compared to 96% in the OECD. Similarly, most small Georgian companies do not have access to high-speed Internet (Geostat, 2022[2]).

Policymakers across the EaP region have been taking measures to tackle these digital divides. Georgia has prioritised the development of high-speed Internet by formulating a dedicated broadband strategy aimed at increasing competitive pressure, attracting investments, and building digital skills and demand. Armenia and Ukraine have been developing their broadband plans, although they are yet to be finalised and adopted. Current national broadband policies in EaP countries prioritise the expansion of fibre and/or 5G technology and investment in infrastructure development. However, broadband policies could benefit from more regular consultations with relevant stakeholders. A sustained multi-stakeholder dialogue involving consumers, network operators, local governments and regulatory could help ensure that the opinions of all parties are adequately considered (OECD, 2021[3]).

Moving forward, key recommendations for policymakers include:

Fostering competition, e.g. by promoting co-investment, infrastructure sharing, and adequate legal and regulatory frameworks. The latter should undergo regular reviews to ensure their continued adequacy. Making multistakeholder consultations on Internet connectivity a more integral part of policy formulation is highly important in this regard.

Increase demand for quality broadband by fostering digital literacy among citizens and firms, addressing information asymmetries and providing open and reliable data on subscriptions, coverage and quality of service.

Digital skills

Digital skills are an absolute pre-requisite for a successful digital transformation. Economies and societies indeed need both digital-savvy citizens to tap into the potential of new technologies in everyday life, and IT specialists to meet increasing labour market demand.

All EaP countries have made good progress in including digital competence in their education curricula. Armenia and Moldova have included it as a key competence for all education levels, while Georgia has focused its formal education efforts on vocational education and training (VET). In most of them, teacher training in digital fields has also been on the rise. Lifelong learning opportunities in digital skills for citizens have widened, considerably fostered by private sector stakeholders across the region. On the other hand, support for digital skills development among small firms remains limited. In general, Ukraine appears at the forefront of digital literacy measures: the country has implemented a wide range of initiatives and tools, including a self-assessment test for individuals to evaluate their digital skills and a digital competence framework based on the EU’s Digital Competence Framework for Citizens (DigComp) to serve as a common reference.

Nevertheless, digital skills levels across the region have not yet reached OECD and EU levels. Data collection on digital literacy remains an important issue, with few insights being available, especially on firms. While EaP countries have included digital skills provisions in overall policy initiatives for digitalisation, the lack of available indicators impedes monitoring and evaluation. Skills assessment and anticipation exercises are also still at a nascent stage in all EaP countries, with only Georgia having developed a systemic approach. Indeed, most tools, such as surveys and/or sectoral studies, are conducted on an ad hoc basis by donors/development partners. Labour market forecasts, when available, do not delve into digital skills aspects.

Finally, while several ministries and governmental agencies are involved in the elaboration of digital skills policies, the latter could benefit from a stronger involvement of certain stakeholders – such as ministries of labour and national employment agencies, but also teachers and private sector representatives.

Going forward, policymakers could complement their existing policy approaches by:

Strengthening multi-stakeholder approaches to digital skills development

Implementing digital skills as a key competence at all education levels

Adopting a framework for digital competences to serve as a common reference, following the example of DigComp 2.1

Developing digital skills assessment and anticipation tools

Stepping up support for digital skills development among firms, especially small ones.

Pillar A: Responsive Government

To adeptly navigate the intricate interplay between SME policy and other domains of policymaking, governments must establish a clear vision for SME policy that is backed by strategic guidelines. They must foster a broad consensus amongst all stakeholders, including the business community, SME associations, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and relevant partner organisations. Pillar A, which iscentred on responsive government, assesses the progress achieved by EaP countries since 2020 regarding the institutional and regulatory framework for SME policy, the operational environment for SMEs, and bankruptcy and second chance.

Institutional and regulatory framework for SME policy

Creating robust and transparent institutional and regulatory framework is pivotal in promoting entrepreneurship and bolstering SME growth. This includes defining clear parameters to identify SMEs; identifying institutions responsible for SME policy design, delivery, monitoring and evaluation; and devising mechanisms for policy discussion and alignment.

The EaP region has made incremental progress in this dimension since 2020 (see Table 2.2). All the countries, except for Armenia and Ukraine, reported gradual improvements across most of the sub-dimensions, with Georgia confirming its position as a frontrunner. These results demonstrate the region’s commitment to SME support and business environment reforms during a particularly challenging period, characterised by a series of negative events that have disrupted policymaking, including the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Nevertheless, all the countries have aligned their national SME definitions with that of the EU in terms of employment criteria, though other parameters still differ. Almost all EaP governments have developed medium-term SME strategies, with variations in structure and evaluation practices.

However, sectoral gaps persist. By the end of June 2023, Georgia was the only country implementing a dedicated strategy covering the period 2021-2025. SME development agencies have expanded beyond entrepreneurship promotion to offer targeted business services supporting enterprise growth and digitalisation; and in Armenia, Georgia and Moldova they also provide credit guarantees to SMEs. Azerbaijan, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine enhanced their agencies’ capacities during the pandemic. Nevertheless, legislative and regulatory simplification, including RIAs, witnessed a setback due to pandemic-related disruptions.

Some progress has been made. Moldova stands out as a leader in systematic RIA application. EaP governments have made strides regarding public-private consultations, reflecting improved online practices and greater SME involvement. Finally, all countries have started taking SME digitalisation into consideration in their institutional and policy frameworks for SMEs, with the establishment of electronic platforms, strategic directions, agency roles, and monitoring across the region. In fact, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia and Ukraine have displayed a strong commitment to SME digital transformation, having allocated resources to relevant agencies.

Looking forward, policymakers should focus on:

Securing implementation through shorter-term action plans and creating synergies between SME development strategies and sector/activity-oriented development plans.

Developing more advanced instruments of policy co-ordination with other sets of strategies (local development, skill development and digitalisation) and the broader national economic development plans.

Systematically applying RIA to all new legislative and regulatory acts that are expected to have a significant impact on the business sector and introducing RIA SME tests.

Upgrading the governance mechanisms of SME agencies, following the recent example of Moldova.

Broaden the involvement in public private consultation (PPC) including by expanding the use of digital platforms and involving businesses operating in new emerging sectors (i.e., ICT, agri-bio enterprises, small tourist operators and logistics).

Strengthen policy and institutional frameworks for the digital transformation of SMEs in non-IT sectors.

Table 2.2. Progress in the institutional and regulatory framework dimension

|

Institutional and regulatory framework |

Armenia |

Azerbaijan |

Georgia |

Moldova |

Ukraine |

EaP average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2024 scores |

3.24 |

3.69 |

4.37 |

3.93 |

3.68 |

3.78 |

|

2024 scores (CM) |

3.29 |

3.49 |

4.19 |

3.82 |

3.80 |

3.72 |

|

2020 scores (CM) |

3.68 |

3.36 |

3.69 |

3.68 |

3.64 |

3.61 |

Note: CM stands for Comparable Methodology. See the “Policy framework, structure of the report and assessment process” chapter and Annex A for information on the assessment methodology.

Operational environment for SMEs

The operational environment for SMEs is essential for fostering business growth without undue bureaucratic barriers. This dimension evaluates the extent to which public administrations have undertaken efforts to simplify regulations, reduce costs and alleviate administrative burdens on SMEs.

Since 2020, the operational environment for SMEs in the EaP region has improved overall. All EaP countries have made significant progress by increasing their provision of e-government services. Ukraine’s Diia initiative is seen as the most advanced tool in this regard, providing a wide range of e-services accessible throughout the country. Digital government platforms are also operational in Armenia, Georgia, and Moldova.

However, data collection on SME e-government services usage remains limited. All EaP countries offer company registration procedures that are relatively simple, fast and inexpensive; Georgia and Armenia have confirmed their position as leaders in this area. Business licensing has also advanced, as all EaP countries have streamlined procedures and established online portals to handle applications. Moldova’s one-stop-shop platform and Georgia’s provision of online services serve as good examples on this matter. Tax compliance procedures have evolved, most notably because the COVID-19 pandemic prompted temporary tax measures for economic recovery. In fact, since 2020, EaP countries have introduced simplified tax regimes, and efforts to ease tax declaration and payment procedures have continued.

EaP countries should maintain this momentum in policymaking by focusing on the following:

Collecting data on the use of e-government services by different categories of SME (by size, type of ownership and location) to improve their design.

Regularly gathering indicators on online registration and monitor the performance of registration agencies across the countries.

Calculating the effective tax rate applied to different categories of SMEs and evaluating the impact of special tax regimes and tax incentives on individual entrepreneurs and small enterprises to avoid distorting effects.

Implementing an automatic VAT-refund system and minimising the potential for fraud and misuse by applying risk-assessment technics.

Table 2.3. Progress in the operational environment dimension

|

Operational environment framework |

Armenia |

Azerbaijan |

Georgia |

Moldova |

Ukraine |

EaP average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2024 scores |

3.99 |

4.25 |

4.51 |

4.34 |

4.11 |

4.24 |

|

2024 scores (CM) |

4.05 |

4.28 |

4.65 |

4.50 |

4.36 |

4.37 |

|

2020 scores (CM) |

2.92 |

4.44 |

4.33 |

3.48 |

3.70 |

3.77 |

Note: CM stands for Comparable Methodology. See the “Policy framework, structure of the report and assessment process” chapter and Annex A for information on the assessment methodology.

Bankruptcy and second chance

Efficient insolvency regimes are essential for ensuring a healthy market since well-structured laws enhance capital allocation, increase productivity and boost cross-border investment. More specifically, timely detection of financial distress, early warning mechanisms, advisory services, well-designed bankruptcy procedures, and second-chance initiatives are crucial in supporting SMEs. This dimension assesses the extent to which EaP countries are facilitating market exit and re-entry by adopting effective and efficient frameworks to prevent and face insolvency, as well as to re-start a business after bankruptcy.

The EaP region’s progress in the areas of bankruptcy and second chance has been uneven. All countries, except Armenia, have demonstrated some improvement since the 2020 assessment. However, overall, this dimension remains one of the weakest performance areas, explained by insufficient preventive measures and second chance promotion initiatives. All EaP countries show significant room for improvement in their measures to identify financial distress and prevent insolvency. While in all the countries (except Armenia) businesses in financial distress can access information on available government support, information on tools and support for SMEs often lacks visibility and accessibility. Moreover, all the countries except Georgia have yet to develop systems to monitor existing measures to prevent insolvency.

Regarding survival procedures, EaP countries prove to have well-designed bankruptcy frameworks. However, average scores were negatively affected by changes to the assessment methodology. Somewhat positive results emerged from the EBRD Business Reorganisation Assessment, which showed that, on average, EaP countries perform at the same level as other assessed countries. In addition, since 2020, all countries except Ukraine have amended their legislative framework for bankruptcy, bringing important improvements. However, more comprehensive data collection and monitoring efforts are needed. Promoting second chance appears as the weakest sub-dimension since none of the EaP countries have comprehensive policies or strategies promoting a fresh start for entrepreneurs’ post-bankruptcy.

Moving forward, EaP countries should:

Establish comprehensive early-warning systems to prevent bankruptcy.

Introduce simplified insolvency proceedings for small cases or SMEs.

Adopt proactive second-chance strategies, facilitating fresh starts for honest entrepreneurs.

Develop monitoring mechanisms for insolvency procedures and programmes.

Collect systematic data on SME insolvency for informed policies.

Table 2.4. Progress in the bankruptcy and second chance dimension

|

Bankruptcy and second chance |

Armenia |

Azerbaijan |

Georgia |

Moldova |

Ukraine |

EaP average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2024 scores |

1.97 |

1.91 |

3.36 |

2.00 |

2.52 |

2.35 |

|

2024 scores (CM) |

2.35 |

3.10 |

3.49 |

2.79 |

3.75 |

3.10 |

|

2020 scores (CM) |

2.66 |

2.76 |

3.06 |

2.63 |

3.24 |

2.87 |

Note: CM stands for Comparable Methodology. See the “Policy framework, structure of the report and assessment process” chapter and Annex A for information on the assessment methodology.

Pillar B: Entrepreneurial Human Capital

Entrepreneurial human capital is essential for economic growth, competitiveness, job creation and wellbeing. This pillar assesses the policy design, implementation and monitoring of the policies in the following areas, which are key for human capital development:

Entrepreneurial learning – development of entrepreneurship key competence as a combination of knowledge, skills and attitudes people should possess for successful career and personal development;

Women's entrepreneurship – the creation of a policy environment in which women can engage on equal terms with men in entrepreneurship, the creation of new jobs, and generation of new value for the national economies and internationally; and

Skills for SMEs – the development of specific, occupational skills for successful entrepreneurship.

Entrepreneurial learning and women’s entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurial learning, which is a central theme of Principle 1 of the SBA, fosters essential competencies and mindsets for economic growth. It transforms societal views, driving innovative human capital.

Since 2020, EaP countries have worked to advance policies and develop frameworks supporting entrepreneurial learning. The EaP average score for this dimension is 3.64, with Georgia and Moldova leading the way. Ukraine has integrated entrepreneurial learning into its overarching economic strategy, while most countries have incorporated it into their education strategies and, in the case of Armenia and Georgia, into their SME strategies. However, not all countries have established formal policy partnerships on entrepreneurial learning.

Significant progress has been made in embedding entrepreneurship as a key competence in national curricula. Armenia and Azerbaijan have made notable strides by updating their curricula to highlight entrepreneurial mindset and skills, with the latter launching new VET infrastructure and career guidance services. Georgia has made efforts to align with the Entrepreneurship Competence (EntreComp) Framework. Online learning solutions, catalysed by the COVID-19 pandemic, have paved the way for the development of innovative teaching methods. Azerbaijan's tehsilim.edu.az and Ukraine's All-Ukrainian Online School are good examples of the creation of dedicated online platforms. There has been additional progress on teacher training across most countries, with major progress being achieved in Georgia with the establishment of a Skills Agency.

In addition, EaP countries have been making efforts towards developing non-formal learning opportunities on entrepreneurship. Azerbaijan, Moldova and Ukraine have introduced normative-legal frameworks to allow for the certification of competencies acquired in informal ways.

Finally, collaboration between higher education institutions and businesses has been growing across the region, often with donor support, promoting innovative practices. However, co-operation between general schools and SMEs on entrepreneurial learning remains underdeveloped.

Overall, while strong achievements have been shown, the monitoring and evaluation of policies – including learning outcomes, teacher competencies, and students’ labour market results – need to be enhanced to ensure policy impact.

Women's Entrepreneurship

This dimension is embedded within Principle 1 of the SBA, which addresses gender disparities in business ownership. It highlights the need for comprehensive policies, collaborative approaches and disaggregated data to bridge gender gaps and empower women’s engagement in business.

EaP countries have sustained efforts to support women entrepreneurs. Georgia and Moldova maintain strong performances across all thematic blocks, averaging 4.90 and 4.40, respectively, while Ukraine has made impressive progress, reaching 4.21. Armenia’s approach remains consistent, addressing the topic in policy documents. All the countries have implemented a range of support measures for women entrepreneurs, albeit to a varying extent. Most of these initiatives are promoted online, primarily through the official websites of SME agencies and/or business associations at the national level. Ukraine stands out as the only country to have created a comprehensive one-stop-shop, Diia.Business, offering a consolidated view of the available support measures. In addition, territorial coverage has broadened, with the establishment of several regional initiatives and/or support centres to assist women entrepreneurs. Efforts to bridge the gender gap in STEM fields have progressed, focusing on awareness-raising and IT skills training. Private sector involvement and international donor support continue to bolster women's entrepreneurship initiatives. However, formal policy partnerships and comprehensive action plans are lacking, notably in Azerbaijan.

While data on women's entrepreneurship remains limited, available insights do shed light on persisting challenges, despite notable improvements. Barriers include access to finance and networks, as well as gender stereotypes, which were exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, as the containment measures increased time spent on domestic tasks. Addressing these issues requires better data. While there are studies assessing barriers to women’s entrepreneurship in these countries, apart from Ukraine, these are not conducted annually.

EaP countries have made noteworthy progress in entrepreneurial learning and women's entrepreneurship. Nevertheless, to advance, EaP countries should consider:

Strengthening policy frameworks for entrepreneurial learning, including introducing entrepreneurship as a key competence at all education levels.

Stepping up efforts on teacher training.

Enhancing co-operation between schools and SMEs to offer practical experiences for students.

Improving monitoring and evaluation practices for entrepreneurial learning outcomes.

Ensuring co-ordination among stakeholders involved in women's entrepreneurship policies and programmes.

Collecting more comprehensive data on gender-related issues and assessing the impact of existing programmes.

Extending support measures beyond early-stage entrepreneurship to aid women entrepreneurs in scaling up.

Addressing gender stereotypes and promoting women's participation in higher value-added sectors.

Developing incentives to reduce women's participation in the informal economy.

Table 2.5. Progress in the Entrepreneurial learning and Women’s entrepreneurship dimensions

|

Entrepreneurial learning and women’s entrepreneurship |

Armenia |

Azerbaijan |

Georgia |

Moldova |

Ukraine |

EaP average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2024 scores |

2.91 |

3.07 |

4.17 |

4.09 |

3.95 |

3.64 |

|

2024 scores (CM) |

3.35 |

3.70 |

4.74 |

4.74 |

4.56 |

4.22 |

|

2020 scores (CM) |

2.60 |

3.89 |

4.45 |

4.29 |

3.83 |

3.81 |

Note: CM stands for Comparable Methodology. See the “Policy framework, structure of the report and assessment process” chapter and Annex A for information on the assessment methodology.

SME skills

Principle 8 of the SBA emphasises the significance of enterprise skills in unlocking SMEs' potential and fostering national economic growth. This SME skills dimension is focused on two main themes, namely the provision of training services for SMEs and skills intelligence and its use for policy and practice.

All EaP countries have made progress in this area since the previous assessment. Notable advancements were observed in Moldova and Ukraine, which have been catching up with Georgia, while institutional changes disrupted improvements in Armenia. SME training services have been made available in all EaP countries and opportunities continue to be expanded. Azerbaijan and Ukraine have made noteworthy progress in this regard with the creation of a network of operators by KOBIA in the former and the launch of Diia.Business for entrepreneurial knowledge and consulting in the latter. All the countries have made efforts to develop courses covering different skills, notably digital and green ones. Moldova is a leader in this domain, with its SME Agency, ODA, having implemented several full-fledged programmes. Georgia has been actively working towards expanding its support, notably for the digital transformation of small firms in non-IT sectors. Meanwhile, Armenia’s approach differs, with most of its SME/start-up skills development programmes being delivered by NGOs.

Online training has also become increasingly available in EaP countries. However, its implementation across the region is uneven. Moreover, the learning outcomes and overall impact of the materials launched thus far could be made more interactive. Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine are enhancing smart specialisation strategies for growth, but further measures such as targeted training are needed to fully engage SMEs in prioritised areas.

On SME skills intelligence, most EaP countries have enhanced their frameworks, gathering sex-disaggregated training statistics and feedback helping to inform new course development. However, assessing the tangible impact of training on skills and SME performance remains infrequent. National frameworks for SME skill data collection and analysis have been strengthened, with Georgia leading through annual surveys and sector-specific studies, and Azerbaijan making notable progress since 2020. Armenia and Ukraine have yet to fully implement such practices.

Finally, skills assessment and anticipation tools in the EaP region are early in their development.

Moving forward, EaP countries could strengthen their approaches to SME skills development by:

Raising awareness of available training provisions for SMEs.

Developing online training opportunities by introducing innovative and digital learning methods.

Capturing the impact of training on skills development and SME performance to improve monitoring and evaluation practices.

Introducing certification of the skills acquired, to help ensure the quality of training.

Strengthening systemic approaches to data collection on SME skills, training, and barriers to participation in training.

Implementing skills anticipation tools.

Offering courses to SMEs in the priority areas identified for smart specialisation.

Table 2.6. Progress in the SME skills dimension

|

SME skills |

Armenia |

Azerbaijan |

Georgia |

Moldova |

Ukraine |

EaP average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2024 scores |

2.37 |

3.59 |

4.12 |

3.89 |

3.91 |

3.57 |

|

2024 scores (CM) |

2.13 |

3.80 |

4.43 |

4.40 |

4.12 |

3.78 |

|

2020 scores (CM) |

1.80 |

2.80 |

4.00 |

3.30 |

2.97 |

2.97 |

Note: CM stands for Comparable Methodology. See the “Policy framework, structure of the report and assessment process” chapter and Annex A for information on the assessment methodology.

Pillar C: Access to Finance

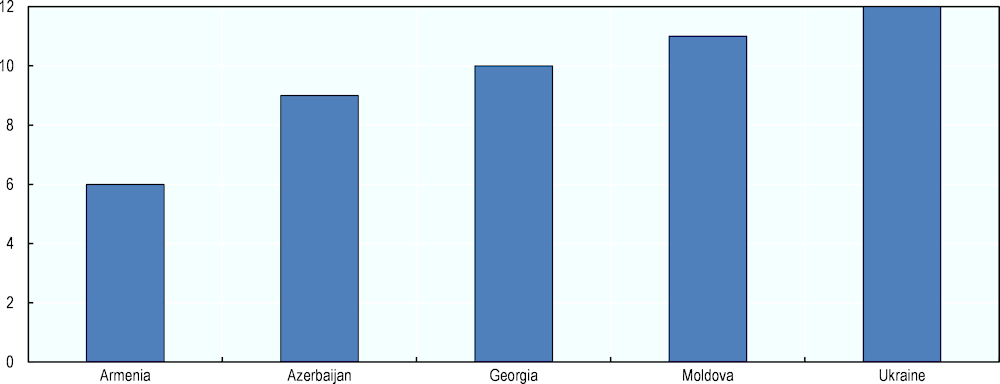

Access to finance can be regarded as the prime accelerator for an SME’s economic growth. However, it remains, in the EaP region as elsewhere, a challenge for SMEs. In EaP countries, the financing gap is estimated to be about USD 44 billion (18% of the countries’ GDP), meaning that, for SMEs’ needs to be fully met, current lending amounts would need to increase by 200%.

This pillar covers six dimensions linked to access to finance: (i) the legal and regulatory framework for bank financing, (ii) the provision of bank financing, (iii) the conditions for non-bank financing, (iv) the ecosystem for venture capital, (v) financial literacy and (vi) digital financial services. The last dimension constitutes an innovation with respect to previous assessments.

Access to finance

Since 2020, many governments have put in place new or larger support mechanisms for access to finance, enacted legal reforms to simplify SMEs’ use of non-bank financing solutions, and conducted more regular assessments on financial literacy. All economies in the region have a reasonably developed legal framework for secured transactions in place, but effective enforcement remains a challenge. Cadastres exist in all countries and are available online and to all stakeholders, and there has been no major change in that regard since the last assessment. Registers for movable assets are also in place across the region and all financial institutions can access them. In Ukraine, online access was restricted after Russia’s invasion and access must be specifically requested. All central banks in the region have a credit register, and private credit bureaus have been further developing. In terms of coverage, most credit bureaus go beyond collecting information from financial institutions, but sources of credit information could be expanded further in some countries, e.g. Moldova and Ukraine. Countries have made progress with the implementation of Basel III requirements – Moldova has now followed Georgia’s lead in fully implementing all requirements, while Armenia, Azerbaijan and Ukraine have made progress on implementation, although Ukraine relaxed some prudential requirements after Russia’s invasion. Loan dollarisation levels remain high in all EaP economies. All central banks, except Ukraine’s, have enacted certain conditionalities to encourage local currency lending, e.g. higher risk weights and mandatory disclosure of foreign exchange risk to borrowers.

The inclusion of ESG indicators in banks’ reporting obligations is not yet widespread. The National Bank of Georgia is the only financial authority in the region that has already developed a green taxonomy to simplify green financing instruments’ charting, and banks need to systematically report on these aspects. With regard to capital markets, none of them in the region are sufficiently developed to be seen as a realistic funding option as local stock exchanges suffer from all-too-limited investor bases.

All economies in the EaP region have implemented credit guarantee schemes. These programmes are increasingly supplemented by consultancy and advisory services for business development. Strengthening private participation in the schemes could bring benefits, especially in Armenia and Azerbaijan. Except for Georgia, none of the schemes are subject to proper impact evaluations.

While microfinance is widely available across the EaP region, leasing and factoring are still underused compared to countries of similar size, notably due to inadequate legal frameworks and lack of entrepreneurs’ awareness and available data. Ukraine still does not have a dedicated legal framework for microfinance. Venture capital is at an early stage and the lack of funding beyond the seed stage constitutes a serious drawback for start-ups.

All countries in the region conduct financial literacy assessments, usually led by national oversight bodies, and in some cases supported by international donors (e.g. Ukraine). There has also been notable progress on digital financial services among a few outsiders (Armenia, Georgia and Ukraine). All EaP countries monitor data protection and sharing, and all authorities, except for Armenia’s, require institutions to share data amidst certain circumstances. An operational resilience framework for financial service providers is also in place everywhere, but only Armenia, Georgia and Moldova regulate outsourcing in the financial services sector. Nevertheless, none of the countries in the region have implemented a multi-stakeholder approach to digital finance supervision so far.

Table 2.7. Progress in the Access to finance dimension

|

Access to finance |

Armenia |

Azerbaijan |

Georgia |

Moldova |

Ukraine |

EaP average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2024 scores |

3.54 |

3.31 |

4.07 |

3.48 |

3.40 |

3.56 |

|

2024 scores (CM) |

3.87 |

3.74 |

4.30 |

3.94 |

3.63 |

3.90 |

|

2020 scores (CM) |

3.86 |

3.32 |

3.85 |

3.78 |

3.54 |

3.67 |

Note: CM stands for Comparable Methodology. See the “Policy framework, structure of the report and assessment process” chapter and Annex A for information on the assessment methodology.

Moving forward, EaP countries could:

Improve enforcement frameworks for secured transactions.

Ensure adequate monitoring and evaluation mechanisms for financial support programmes, by going beyond the collection of basic usage data.

Improve availability and collection of statistics in the financial sector, by displaying an inclusive approach towards non-bank financing sources.

Establish support mechanisms for developing growth-stage funding for start-ups, e.g. via government participation in specific venture capital (VC) funds, or the establishment of a fund of funds.

Develop strategic directions for digital financial service regulation and regularly consult both public and private stakeholders.

Pillar D: Access to Markets

SMEs in the EaP region have substantial opportunities in international markets and public procurement. Involvement in public procurement not only drives business growth but also promotes competition, enhances value for money and fosters innovative solutions. Similarly, global trade offers chances to join value chains and enhance innovation and productivity. However, SMEs face challenges accessing these markets due to information gaps, incompatible quality standards, complex procedures and limited resources. Targeted policies are essential to overcome these barriers and expand market opportunities. This pillar assesses EaP reforms in public procurement, standards and technical regulations, and SME internationalisation.

Public procurement

SME involvement in public procurement offers mutual benefits to both businesses and the public. Such participation is crucial for economic recovery, acting as a shield during crises. However, challenges such as complex procedures, resource constraints, and stringent qualification requirements hinder SMEs’ entry into the markets. This dimension evaluates EaP countries’ efforts to foster a more inclusive public procurement market for SMEs.

The results of the SBA assessment in public procurement indicate a noticeable change in the trajectory of EaP countries’ performance. While some countries show progress in policy implementation and monitoring of public procurement (Azerbaijan, Moldova and Ukraine), all countries exhibit a deterioration of the regulatory framework.

Standard public procurement procedures have been put aside in favour of less competitive alternatives to face urgent needs resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine, which have also brought delays in approval and implementation of strategic initiatives. Since 2020, public procurement laws have only been slightly amended and medium-term strategic frameworks have seen limited progress, while harmonisation between public procurement strategies and strategies in related fields is lacking. Institutions in charge of public procurement are affected by capacity and skills gaps and conflicts in decision-making roles. E-procurement systems exist but are underutilised, although some progress has been made in the provision of public access to data on procurement activities.

Table 2.8. Progress in the public procurement dimension

|

Public procurement |

Armenia |

Azerbaijan |

Georgia |

Moldova |

Ukraine |

EaP average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2024 scores |

2.80 |

2.55 |

3.61 |

3.16 |

3.61 |

3.15 |

|

2024 scores (CM) |

2.92 |

2.70 |

3.44 |

3.35 |

3.25 |

3.13 |

|

2020 scores (CM) |

3.83 |

2.66 |

4.26 |

3.98 |

3.22 |

3.59 |

Note: CM stands for Comparable Methodology. See the “Policy framework, structure of the report and assessment process” chapter and Annex A for information on the assessment methodology.

Going further, policymakers should:

Expand and improve regulations facilitating SME participation in public procurement.

Strengthen the capacity of central institutions by providing training, reviewing complaints, and implementing a monitoring system.

Ameliorate the sequencing of e-procurement and exploit it for generating and using data.

Encourage SME participation by leveraging centralised purchasing and framework agreements and providing training to improve SMEs’ trust and participation.

Raise the status of procurement officers and improve their knowledge and skills, in order to avoid corruption.

Standards and technical regulations

Technical regulations establish essential criteria for products before their market introduction, while standards promote interoperability and fair competition, thereby fostering innovation and trade. SMEs, often challenged by foreign standards and costly procedures, need accessible information and support for compliance. This dimension examines quality infrastructure alignment.

All EaP countries have made progress regarding standards and technical regulations, with the EaP average score increasing from 3.67 in 2020 to 3.98 in 2024 using comparable methodology. Georgia remains the leader of this dimension, having reached a score of 4.37. Each country has a designated government body responsible for the overall co-ordination of technical regulations and quality infrastructure (QI). Georgia has established an independent Market Surveillance Agency (MSA), while Ukraine has progressed in its negotiations with the EU on Agreements on Conformity Assessment and Acceptance of Industrial Products (ACAA), and Moldova has aligned its legislation to bring technical regulation in line with the provisions of the World Trade Organization (WTO) Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT).

All the EaP countries have adopted measures to ensure their technical regulations and standardisation laws harmonise with the EU acquis. Armenia, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine have an action plan or a similar document on transposing EU sectoral legislation in priority sectors. Georgia’s, Moldova’s and Ukraine’s standards bodies were granted a CEN and CENELEC Affiliate status, which was approved in 2022 and entered into force in January 2023. Except for Azerbaijan, the adoption rate of EU standards is at least 50% in priority sectors. All countries have accreditation bodies, although only those of Georgia and Moldova have been completely positively assessed by the European Co-operation for Accreditation (EA) or by peer organisations. Azerbaijan does not have legislation on conformity assessment in line with the acquis. Likewise, Armenia’s legislation is not totally in line with the acquis, which also influences its specific conformity assessment activities. Conformity assessment bodies in line with EU requirements exist in Ukraine’s priority sectors. Georgia and Moldova have such bodies in most priority sectors. All five countries have an operational metrology body, although only Armenia, Georgia and Ukraine also have a strategy for metrology. Most of the five countries have legislation on metrology in line with the acquis, while Azerbaijan is preparing a proposal for such legislation. Market surveillance is more advanced in Georgia and Ukraine, while Armenia, Azerbaijan and Moldova lag behind.

All countries have implemented measures for SME awareness and developed mentoring programmes. Concerning digitalisation, on average, countries demonstrate relatively low scores. Most of them offer support to SMEs for their integration into the EU Digital Single Market. Additionally, most have a strategy for the digitalisation of processes within the authorities responsible for technical regulation. However, there is room for improvement.

Moving forward, EaP countries could implement the following recommendations:

Enhance market surveillance quality infrastructure and intensify its understanding.

Seek international recognition for quality infrastructure.

Develop standards education strategies with SME-specific considerations.

Establish financial measures to further support SME participation in standardisation.

Improve the digital maturity of the technical regulation system and quality infrastructure, particularly in conformity assessment.

Create export platforms tailored for SMEs trading with the EU where absent.

Improve the regular evaluation of the technical regulation system and quality infrastructure, considering areas with and without regular assessment.

Continue with good practice from Twinning projects after their completion.

Table 2.9. Progress in the standards and regulations dimension

|

Standards and regulations |

Armenia |

Azerbaijan |

Georgia |

Moldova |

Ukraine |

EaP average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2024 scores |

3.60 |

3.20 |

4.37 |

4.13 |

3.86 |

3.83 |

|

2024 scores (CM) |

3.96 |

3.34 |

4.47 |

4.21 |

3.91 |

3.98 |

|

2020 scores (CM) |

2.80 |

3.23 |

4.63 |

3.95 |

3.75 |

3.67 |

Note: CM stands for Comparable Methodology. See the “Policy framework, structure of the report and assessment process” chapter and Annex A for information on the assessment methodology.

SME Internationalisation

Given the relatively small size of most EaP countries’ domestic markets, SMEs’ success relies heavily on their ability to reach foreign markets. Unfortunately, obstacles including unequal access to information, financial constraints, and insufficient expertise can hinder SMEs’ participation in international trade. This dimension assesses governments’ support for SMEs with export-oriented endeavours.

Since the 2020 assessment, all EaP countries except for Armenia have improved their performance in this area. These efforts are reflected by the adoption of export promotion programmes, mainly facilitated by SME agencies, investment promotion agencies, and dedicated departments within Ministries of Economy. While currently there are no active export strategies in any of the EaP countries, most of them have adopted other relevant strategic policy documents. Common forms of support include the facilitation of trade missions, participation in trade fairs, and consultancy and advisory services. Moreover, all governments provide some form of financial support to exporting companies, although these measures differ in each country.

Overall, EaP governments need to establish more comprehensive monitoring and evaluation systems to enhance the effectiveness of export promotion programmes. Georgia is a leader in this regard, as it has a well-designed framework to monitor and evaluate the impacts of its services. Policy frameworks for SME integration into global value chains (GVCs) are in the early stages in most EaP countries. In Armenia, Moldova and Ukraine, although no systematic support is provided, proposals in this direction have been presented. In Azerbaijan, to support cluster development, eligible SMEs can apply to obtain substantial exemptions from different types of taxes for seven years. Again, Georgia at the forefront in this area, with established cluster policies and proactive assessments of changing GVCs.

The OECD Trade Facilitation Indicators indicate that the implementation of measures to facilitate EaP countries’ business access to foreign markets has improved over time. However, while all EaP countries have enhanced their performance across the assessed areas, there are still performance gaps with OECD countries, specifically in areas related to documents, border agency co-operation, and procedures' automation.

All EaP countries have implemented a basic regulatory framework focused on policies to encourage e-commerce use by SMEs. However, alignment with EU frameworks could be improved, especially in regard to regulations on terms and conditions for accessing e-commerce platforms, on parcel delivery, and on consumer protection. Moreover, while all governments have designed measures to promote SMEs’ use of e-commerce, the degree of their implementation varies. All countries, except Georgia, lack any form of a monitoring mechanism to assess the effectiveness of these measures.

Thus, moving forward, EaP countries should:

Strengthen support for SME integration into GVCs by regularly assessing evolving GVCs, facilitating SME-MNC linkages, and incentivising foreign direct investment (FDI) to foster technology and financial transfers.

Expand the regulatory framework by introducing provisions on consumer protection and regulations for paid advertisement in e-commerce.

Automate and streamline trade-related procedures, including harmonising documents in line with international standards and improving internal and external border agency co-operation.

Establish or enhance effective and transparent monitoring and evaluation mechanisms across all sub-dimensions to ensure continued efficiency and effectiveness.

Table 2.10. Progress in the internationalisation dimension

|

Internationalisation |

Armenia |

Azerbaijan |

Georgia |

Moldova |

Ukraine |

EaP average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2024 scores |

2.91 |

3.25 |

4.52 |

3.45 |

3.77 |

3.58 |

|

2024 scores (CM) |

2.82 |

3.33 |

4.66 |

3.70 |

3.60 |

3.62 |

|

2020 scores (CM) |

2.98 |

3.20 |

3.76 |

2.87 |

2.75 |

3.11 |

Note: CM stands for Comparable Methodology. See the “Policy framework, structure of the report and assessment process” chapter and Annex A for information on the assessment methodology.

Pillar E: Innovation and Business Support

SMEs often fall behind larger companies in terms of productivity, with relatively more pronounced gaps in the manufacturing sector. At the firm level, drivers of productivity performance relate to managerial and workforce skills and the adoption rate of innovations. SMEs can struggle in this regard, considering that they often face difficulties in obtaining information, offering training to their employees, accessing advanced consulting services and introducing new technologies. Innovation is also at the heart of the transition to a cleaner global environment, as improved processes and new technologies can make manufacturing more sustainable, reduce pollution and increase resource efficiency. Pillar E assesses policies promoting productivity, innovation and green practices in SMEs.

Business development services

Business development services (BDS) cater to various topics, including information provision, training, consultancies and mentoring. They enhance competitiveness, efficiency and profitability by allowing entrepreneurs to start and operate businesses and by helping SMEs enter and explore new markets. However, these services need to adapt to evolving market conditions, technological advancements, and digitalisation trends. This dimension evaluates government initiatives designed to ensure that SMEs can access quality BDS and to address related market failures, with a sub-dimension focused on digital transformation support for SMEs.

The assessment for the BDS dimension results in a score of 3.57. On a comparable basis with the previous SBA assessment, this reflects an overall positive trend to enhance SME development services across the EaP region. Apart from Armenia, all countries bolstered their SME support agencies and expanded their services. Smaller countries, such as Moldova and Georgia, tend to manage support programmes directly through their SME agencies, whereas larger ones like Ukraine are opting for a more decentralised model leveraging external actors in the ecosystem for business support. The trend of countries strengthening SME support agencies is evident except in Armenia, where the government’s overall capacity to assist SMEs has been reduced. Performance concerning the increasing role of private BDS providers has improved slightly across the EaP region, with Azerbaijan and Moldova demonstrating significant developments. Governments employ different strategies to engage private BDS providers, including outsourcing the provision of certain services to selected expert advisors (as in the case of Azerbaijan) or co-financing specialised consultancy costs (e.g. Georgia and Moldova). The EBRD’s “Advice for Small Business” programme co-finances SME advisory projects and empowers local consultants through training. According to the EBRD’s data, most participating SMEs in EaP countries saw significant gains, including job creation and higher turnover rates.

Finally, regarding digital transformation, training in digital skills is the most common form of support provided by national SME agencies, although tailored analyses by specialised consultants of SMEs’ digital needs are still missing. Some countries have started introducing full-fledged programmes for SME digitalisation (e.g. Moldova and Georgia), and potential partnerships with non-governmental actors should be explored to further SME digitalisation.

As EaP countries update their policy approaches to design and implement BDS for SMEs, the following recommendations could be taken into consideration:

Include dedicated measures to deliver BDS for SMEs in governments’ strategic documents.

Ensure the sustainability of regional offices of SME agencies through strong quality-control mechanisms and cost/benefit analysis.

Embed single information portals with information on all actors in the BDS ecosystem on SME agencies’ websites, including donor-led initiatives and private quality-assured consultants.

Develop a more market-based provision of BDS to SMEs by outsourcing support services to private BDS providers and increasing the offer of co-financing mechanisms to SMEs.

Develop dedicated support programmes for SME digitalisation, including elements to enhance digital skills, company-specific digitalisation roadmaps, and financial tools to facilitate technology adoption.

Improve the evaluation of business support programmes to assess the impact of BDS on various measures of SME performance.

Monitor SME digitalisation by expanding the collection of statistical indicators on the adoption of digital technologies in the business sector.

Table 2.11. Progress in the business development services dimension

|

Business development services |

Armenia |

Azerbaijan |

Georgia |

Moldova |

Ukraine |

EaP average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2024 scores |

3.06 |

3.33 |

4.22 |

3.69 |

3.57 |

3.57 |

|

2024 scores (CM) |

3.27 |

3.81 |

4.35 |

4.01 |

3.27 |

3.74 |

|

2020 scores (CM) |

4.10 |

3.12 |

4.30 |

3.70 |

2.80 |

3.61 |

Note: CM stands for Comparable Methodology. See the “Policy framework, structure of the report and assessment process” chapter and Annex A for information on the assessment methodology.

Innovation policy

Although SMEs are crucial actors for generating and spreading innovations, their size may limit their capacity for sustained innovation. This dimension evaluates EaP governments’ efforts to encourage SME innovation.

EaP countries show a slight improvement in this dimension compared to the previous assessment, achieving an average score of 3.09. The focus has shifted towards diversified financial support for innovative SMEs, notably in Ukraine. However, overarching policy frameworks for innovation, especially those tailored for SMEs, remain underdeveloped. While Moldova and Ukraine have dedicated national strategies, most countries incorporate innovation elements in broader documents. This deficiency is compensated by efforts to boost innovation in other ways, as observed in Armenia and Georgia's socio-economic strategies. Despite positive institutional shifts towards supporting business innovation, there is large variation in the effectiveness of innovation agencies, with a notable scarcity of SME-specific initiatives and impact evaluations. Regarding institutional support, the expansion of in-kind services is apparent, often favouring the digital and IT sectors. Incubators and accelerators are widely present across the region, driven by both public and private entities. Science-industry linkages and technology transfer have gained some traction, as exemplified by Georgia and Ukraine, but their potential remains overall underutilised across the region. Government financial support for innovative SMEs has improved, mainly due to advancements in Armenia and Ukraine. However, the focus remains skewed towards the IT sector and start-ups. Grants are the primary direct financial support mechanism, varying in objectives and risk-sharing features. Despite EU funding programs being available, their engagement, particularly by SMEs, remains limited, and indirect financial incentives are scarce.

While renewing their policies to build a more innovative SME sector, EaP countries should focus on the following reform priorities:

Highlight the role of SME innovation in strategic documents.

Strengthen co-ordination and implementation capacity by identifying bodies tasked with supporting SME innovation and building staff capacity for dedicated programmes.

Build the skills of agencies tasked with technology transfer and intensify co-operation between academia and the private sector to foster science-business linkages.

Extend support beyond start-ups to mature SMEs and consider services to support technology absorption in more mature SMEs.

Ensure that a matching component is required when awarding grants/soft loans, to share risks with beneficiaries of financial instruments for innovation.

Introduce more flexible and market-based indirect financial incentives for innovation that are less prone to distortions and broaden the set of potential beneficiaries of support programmes.

Strengthen the capacity of national statistical offices to collect information about SME innovation performance.

Table 2.12. Progress in the innovation policy dimension

|

Innovation |

Armenia |

Azerbaijan |

Georgia |

Moldova |

Ukraine |

EaP average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2024 scores |

3.00 |

2.85 |

3.44 |

3.11 |

3.03 |

3.09 |

|

2024 scores (CM) |

2.39 |

2.22 |

2.73 |

2.59 |

2.42 |

2.47 |

|

2020 scores (CM) |

2.48 |

2.25 |

2.38 |

2.41 |

2.01 |

2.31 |

Note: CM stands for Comparable Methodology. See the “Policy framework, structure of the report and assessment process” chapter and Annex A for information on the assessment methodology.

Green economy

Facilitating green SME practices can not only help in this regard, but can also boost competitiveness by reducing costs, enhancing market access and promoting technology adoption. This dimension evaluates government backing for greener SME practices using regulatory, financial and informational tools.

EaP countries have seen a slight increase in this dimension, achieving an average score of 2.81, with more pronounced improvements since the previous SBA assessment when comparing scores computed with comparable methodologies. However, environmental policies in most EaP countries policies rarely consider the specific needs of SMEs and financial incentives for green practices are not widespread. Moldova stands out as the leading performer in this dimension, due to its SME-focused environmental policies and its dedicated financial support programmes for greening SMEs. While all EaP countries acknowledge the importance of green initiatives for SMEs, concrete provisions in high-level planning documents are limited. Moldova, Georgia, and to a lesser extent, Armenia, have provisions for SMEs in their strategic policies. Other countries lack specific targets, potentially overlooking SME-specific barriers to improved environmental performance. Implementation-wise, SME agencies rarely promote green initiatives. Moldova is an exception, with its local SME agency (ODA) playing a prominent role in promoting greening practices directly to entrepreneurs. Financial support for SME greening is often reliant on donor funding. Progress has been observed across all EaP countries regarding the availability of tools and instruments supporting SMEs in adopting green practices. Environmental regulations are evolving, such as Armenia's risk-based environmental impact assessments. Moldova employs deterrents like tax measures and environmental pollution charges. While environmental management systems are being promoted, there is only limited financial support for SMEs (except in Moldova). Green public procurement exists, but its impact on SMEs is uncertain.

To advance their policy frameworks for supporting greener SMEs, EaP governments could consider the following reform priorities:

Adapting national green economy policies and targets to SMEs.

Enhancing institutional capacity to provide guidance and support to SMEs – which, in turn, will raise awareness and assist SMEs in their transition toward environmentally friendly practices.

Emphasising the business case for improving environmental performance. Government agencies could leverage a diversity of intermediaries to enhance outreach to SMEs.

Facilitating partnerships and best-practice sharing among businesses to support SME greening activities.

Creating a demand for greener products, services, and production processes, ensuring that public procurement policies adopt green/sustainable assessment criteria in their tenders.

Increasing the availability of financing instruments for investing in greener equipment and processes.

Improving the statistical production of environmental indicators to strengthen tools to evaluate the impact of SME greening policies, certification and support programmes on actual SME environmental performance.

Table 2.13. Progress in the green economy dimension

|

Green economy |

Armenia |

Azerbaijan |

Georgia |

Moldova |

Ukraine |

EaP average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2024 scores |

2.51 |

2.54 |

3.08 |

3.38 |

2.56 |

2.81 |

|

2024 scores (CM) |

2.80 |

2.52 |

3.27 |

3.74 |

2.61 |

2.99 |

|

2020 scores (CM) |

2.43 |

2.15 |

2.74 |

3.16 |

2.49 |

2.59 |

Note: CM stands for Comparable Methodology. See the “Policy framework, structure of the report and assessment process” chapter and Annex A for information on the assessment methodology.

Key findings for each country

Armenia, despite challenges, experienced remarkable economic growth. In 2022, the country’s GDP surged by 12.6%, primarily fuelled by investment, domestic consumption and the tertiary sector. The large influx of businesses and individuals from Russia contributed substantially to the economic growth. Exports of goods grew by 75% in 2022, driven by shifts in regional supply chains. The importance of industry and agriculture in Armenia’s economy has been steadily decreasing, while the ICT sector has recently been expanding, including because of an influx of skilled labour from Russia. As of 2021, SMEs accounted for nearly 99.9% of all businesses in the economy, with micro-enterprises making up 94.7% (Armstat, 2022[4]). In 2021, SMEs contributed 69.6% to overall business employment and generated up to 63% of the value added in the business sector.

Table 2.14. Overview of Armenia’s key reforms since 2020 and recommendations

|

Key reforms |

Key recommendations |

|---|---|

|

Adopted an SME Development Strategy for 2020-2024 and a National Digitalisation Strategy for 2021-2025 Provided training from 2021-2022 for teachers in general education on technology and entrepreneurship Launched an Economic Modernisation Program for interest rate subsidies on loans and leases to purchase modern (new) equipment Improved services on standardisation, metrology and conformity assessment Made the use of e-procurement mandatory Introduced a pilot project to collect data on SME adoption of digital technologies and created a programme to help start-ups |

Ensure and monitor implementation of the National Digitalisation Strategy Improve tax compliance, accelerate regulatory reforms and enhance RIA application Streamline bankruptcy procedures, introduce out-of-court debt restructuring options, and promote a second chance policy Collect data on SME skills and women’s entrepreneurship, and improve co-ordination among support providers Encourage bank lending to SMEs by streamlining enforcement processes and enhancing their efficiency Identify a co-ordinating agency for SME services, focus on policy coherence, and consolidate innovation support Develop a comprehensive strategy to promote green practices among SMEs |

Azerbaijan, a major hydrocarbon exporter, saw its GDP grow by 4.7% in 2022, benefiting from rising oil and gas prices driven by Russia's invasion of Ukraine. This bolstered the country’s post-COVID-19 recovery, despite inflation reaching nearly 14% in 2022. The mining and quarrying sector continues to dominate, with the extraction of crude petroleum and natural gas accounting for 45% of value added in 2022, while agriculture employed over a third of the workforce but contributed only 4.8% of value added in 2022. The economic potential of SMEs remains largely untapped: in 2021, they generated 16.4% of value added and accounted for 41.8% of total employment (SSCRA, 2022[5]). Azerbaijan has the potential to harness digital transformation to diversify its economy.

Table 2.15. Overview of Azerbaijan’s key reforms since 2020 and recommendations

|

Key reforms |

Key recommendations |

|---|---|

|

Included SME measures in the Socio-economic Development Strategy 2022-2026 and amended the Insolvency Law Established women resource centres in regions Developed a framework to collect and analyse data on SME skills and a network of operators to step up training provisions Implemented Basel III principles Established an online sales platform to support SME exports Outreach and financial support to SMEs ensured through KOBIA’s network of sub-structures |

Ensure that the upcoming NDS adopts a comprehensive approach for digital transformation in non-IT sectors Complement the National Socio-economic Development Strategy with a comprehensive SME strategy Incorporate entrepreneurship as a key competence across education levels Improve the legal framework for secure transactions and promote non-bank financing options for SMEs Introduce financial support mechanisms to support exporting SMEs and provide trade insurance services Improve monitoring practices by assessing the impact of selected support programmes on beneficiaries’ performance |

Georgia’s economy remained resilient despite short-term disruptions caused by Russia's invasion of Ukraine. The country’s GDP grew by 10.1% in 2022, supported by an influx of skilled migrant workers, business relocations from Russia, and increased transportation flows. Inflation, which had been high since 2021, decreased to 0.6% in June 2023 due to effective policy measures. Georgia’s foreign trade turnover increased by 33.4% in 2022, with a focus on exports like copper ores, cars and wine. The ICT sector contributed 4.7% to GDP and grew by 49.9% in 2022. In 2021, small businesses represented 98.2% of the business population, whereas medium-sized enterprises accounted for 1.5%. Although SMEs’ employment levels are still lower than pre-pandemic levels, they represent 61.8% of the business sector workforce. SMEs’ value added has increased over 2015-2021, but their share of total business sector value added has remained between 53% and 61% over that period, falling to 53% in 2021.

Table 2.16. Overview of Georgia’s key reforms since 2020 and recommendations

|

Key reforms |

Key recommendations |

|---|---|

|

Adopted an SME Development Strategy for 2021-2025, with new priorities for women’s entrepreneurship and the green economy Created a Skills Agency, notably launching teacher networks to stimulate VET partnerships Expanded the national credit guarantee scheme following the pandemic Export assistance programme and growth hubs launched by Enterprise Georgia to support SMEs with training, services and financing, along with significant improvements in monitoring and evaluation Established an independent Market Surveillance Agency |

Adopt a National Digital Strategy Explore initiatives to promote a second chance for bankrupt entrepreneurs, including incentives and dedicated programmes Integrate entrepreneurship into education at all education levels, enhance teacher training, and improve monitoring and evaluation. Implement collateral/factoring reforms and larger-scale start-up funding Revise the e-procurement system to align with EU directives and improve data quality Consider indirect financial incentives for innovation and research and development (R&D) Develop reporting requirements on firm size within ESG reporting frameworks to monitor impact of green finance policies on SMEs |

Moldova has faced several crises in recent years, including the COVID-19 pandemic and severe droughts in 2020, which resulted in recession. Although the country rebounded with 13.9% growth in 2021, Russia's war of aggression against Ukraine in 2022 brought new challenges – including trade disruptions, a significant influx of refugees, and high inflation – which resulted in a contraction of the economy of 5.6%. Moldova, seeking to reduce its dependence on Russian gas, witnessed soaring energy prices, contributing to inflation levels of up to 34% in 2022. SMEs accounted for 59% of business sector employment and 38% of turnover in 2021. Their share in low-value-added sectors, albeit predominant, has been decreasing, while the country has the second-highest share of SMEs in the ICT sector among EaP countries (5% of total SMEs in 2021). Fostering SME growth and promoting a competitive market will help address the challenges posed by rising costs and labour shortages.

Table 2.17. Overview of Moldova’s key reforms since 2020 and recommendations

|

Key reforms |

Key recommendations |

|---|---|

|

Developed the National Programme for Promoting Entrepreneurship and Increasing Competitiveness 2022-26 (PACC) Efforts to align Education Code with European key competences and progress in non-formal learning Launch of the Investment incentive programme “373” Adopted a State Programme for SME growth and internationalisation Successful launch and implementation of new comprehensive programmes to support the digital transformation of SMEs as well as digital Innovations and technological start-ups |

Ensure implementation and effective monitoring and evaluation (M&E) of the new National Digital Strategy Introduce SME-focused RIA test Enhance skills assessment and anticipation by collecting data on SME skills, needs, and in-house training, sharing results on an online database Promote alternative financing, explore VC sector options, and improve financial literacy of entrepreneurs Update MTender and raise user skills to better align with regulatory requirements and options Enhance SME access to external advisors, introduce incentives for R&D and innovation investment, encourage green practices among SMEs and enhance data collection on their environmental and greening performance |

Ukraine has faced severe challenges in recent years, including a 3.8% GDP decline in 2020 due to COVID-19 and a 29.1% GDP contraction caused by Russia’s war of aggression in 2022. Despite this, the country’s economy has shown resilience, with 2023 growth estimated at 2-3% in mid-2023. Exports have dropped by around 43%, with transport issues posing major challenges to businesses. While Ukraine's banking system has remained resilient, non-performing loans have grown to 38%. International aid has played a crucial role, with financial assistance needs estimated at USD 36-48 billion in 2023. SMEs, which constituted 99.98% of all enterprises in the business sector in 2021, accounted for 81.6% of the total business employment in Ukraine and generated 70.2% of value added at factor cost in the business sector that year (State Statistics Service of Ukraine, 2023[6]). The digitalisation process, already a policy priority before the war, has advanced, and the IT sector has been showing impressive resilience in wartime.

Table 2.18. Overview of Ukraine’s key reforms since 2020 and recommendations

|

Key reforms |

Key recommendations |

|---|---|

|