As stewards of the public administration, centres of government (CoGs) are often responsible for setting the tone and culture in the public sector, including through steering public administration reform (PAR) efforts. This is becoming increasingly important as governments worldwide seek to modernise their methods to better reflect the changing environment and citizens’ needs. PARs are long-term and challenging and, as such, require good co-ordination and top-level buy-in. This chapter discusses the role that the CoG must play in PARs, including effective mechanisms, such as resource allocation, political prioritisation, monitoring, stakeholder consultation and communication, for doing so. PARs are context-specific and effective ones must be fit for purpose. Given this, this chapter provides specific practical examples of co-ordination efforts from the CoG in driving PARs, focusing on new or binding mechanisms, central management and steering, initiation and oversight, utilising existing guiding and co-ordination mechanisms and a focus on monitoring or management tools.

Steering from the Centre of Government in Times of Complexity

6. Guiding high-performing public administrations from the centre

Abstract

Key messages

Governments are increasingly recognising the need to move away from traditional modes of governing as these are not fit for the complexity of the future. They are also increasingly interested in how to achieve successful public administration reform and modernisation.

Centres of government (CoGs) act as stewards of the public administration, setting the tone and guiding good practices. Many CoGs are responsible for steering public administration reform (PAR) efforts. PARs require sound co‑ordination and top-level buy-in given they are long-term and challenging.

The research suggests that CoGs play a co‑ordination role; however, the specifics of this vary greatly across countries and depend largely on their planning approaches for managing reforms. Thus, approaches to implementing PARs need to be fit for context.

CoGs usually do not have full control or influence when it comes to delivering or implementing PARs. It is therefore important to consider clear directions on PAR, roles and responsibilities for the CoG and other agencies.

Additional considerations for CoGs in steering PARs include political support that extends beyond election cycles (given PARs often require long-term efforts), communication of PARs to citizens and ensuring PARs are incorporated into planning and resource allocations.

1. Introduction

Governments face increasing pressure to work in new ways due to changing expectations from citizens, the need to address horizontal and cross-cutting issues and in response to multiple crises (OECD, 2023[1]). The current context calls for public administration modernisation to ensure that governments have the capacity and instruments required for the future. Nearly all OECD member countries are currently engaged in PAR, ranging from whole-of-government reforms to more focused initiatives such as the digital transformation of the public service. CoGs are instrumental in stewarding, operationalising and co‑ordinating government agendas and in shaping the values and practices of public administration. No matter the focus, CoGs need to ensure cohesive and sustainable PAR efforts that result in sustained change (OECD, 2023[2]).

CoGs have recently recognised that this topic has become more challenging. This is because steering long-term reforms is difficult in an era of crises, geopolitical shifts and increasing expectations from citizens. While governments recognise that traditional modes of governing are no longer fit for purpose, there is no one clear path forward for governments to choose. Thus, CoGs’ role in supporting direction setting and decisions on PARs can be difficult.

This chapter will explore the CoG’s role in PARs through the following structure:

The role of the CoG in PARs.

Co‑ordinating whole-of-government reforms from the centre.

Guiding public sector innovation reform from the centre.

Common challenges and enablers.

2. The role of the CoG in PARs

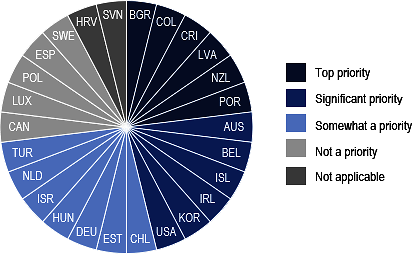

In almost half of countries (46%), PARs are a top or significant priority for the CoG (see Figure 6.1). As a steward of vision, strategy and cross-cutting and complex priorities, the CoG’s task in the management of reform is to drive collective and cohesive action to achieve reform outcomes.

Figure 6.1. The importance of steering PAR for the centre

Note: n=26. Respondents to the OECD survey were asked: “How much of a priority are the following functions in the CoG?”.

Source: OECD (2023[3]), “Survey on strategic decision making at the centre of government”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

The role of the CoG is reinforced in the OECD 2020 Policy Framework on Sound Public Governance, which highlights the capacity for whole-of-government co-ordination led from the centre as a key enabler of sound public governance (OECD, 2020[4]). A central authority (for example, the CoG) is also recognised as being critical to ensuring the coherent, integrated and multidimensional approach required for administration-wide change (OECD, 2023[5]).

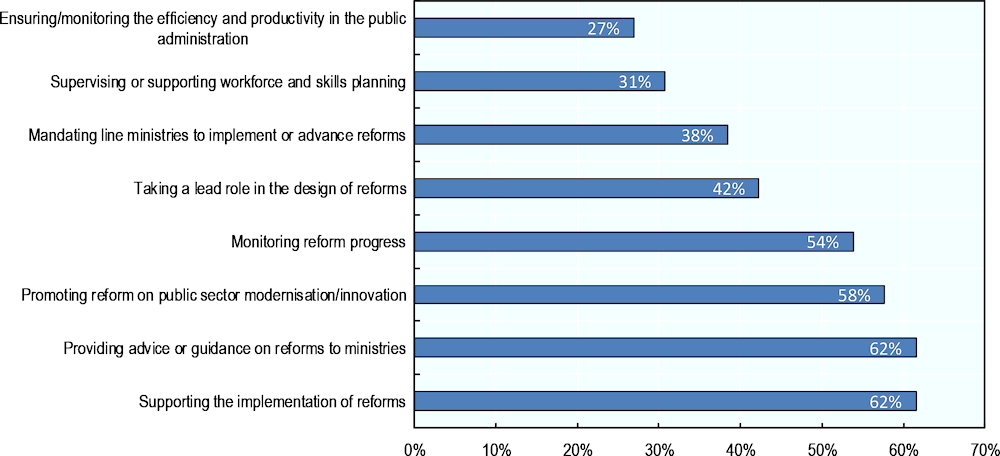

The activities that CoGs carry out vary. Most CoGs support the implementation of reforms and provide advice or guidance to line ministries. Likewise, 58% of CoGs use their position to communicate across all government entities to promote reforms for public sector modernisation or innovation. CoGs, at times, have significant responsibilities in stewarding PARs, while in others, line ministries might have responsibilities related to designing and implementing reforms (see Figure 6.2).

Figure 6.2. Activities undertaken by CoGs in relation to PARs

Note: n=26. Respondents to the OECD survey were asked: “What activities does the CoG do in PARs in your country?”.

Source: OECD (2023[3]), “Survey on strategic decision making at the centre of government”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

Mechanisms for CoGs to effectively steward and guide PARs

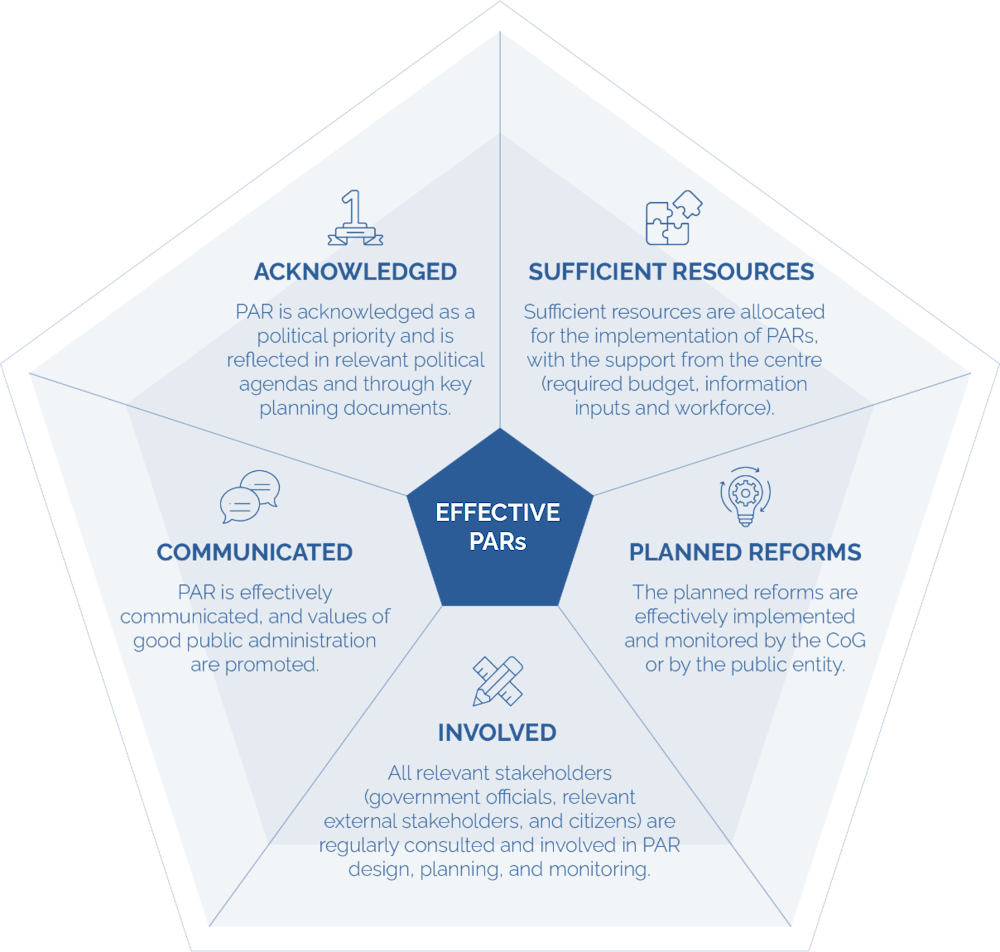

For CoGs to effectively guide and support PARs, they need to consider appropriate institutional settings, co‑ordination mechanisms and capacities. CoG feedback and the EU-OECD SIGMA initiative (OECD, 2023[5]) suggest that PARs are effectively implemented through the following five mechanisms, also detailed in Figure 6.3:

PAR is acknowledged as a political priority and reflected in relevant political agendas and key planning documents. The objectives and measures of PAR also need to be linked and contribute to the overall government vision and priorities.

Sufficient resources are allocated for the implementation of PARs, with support from the centre (this should include the required budget, information input and workforce).

The planned reforms are effectively implemented and monitored by the CoG or by the public entity in charge of reporting lines and mechanisms to the CoG.

All relevant stakeholders are regularly consulted and involved in PAR design, planning and monitoring (this includes government officials, relevant external stakeholders and citizens).

PAR is effectively communicated and values of good public administration are promoted.

Figure 6.3. Five mechanisms for CoGs to effectively guide and support PARs

Source: (OECD, 2023[5]), The Principles of Public Administration, https://www.sigmaweb.org/publications/Principles-of-Public-Administration-2023.pdf.

While governance arrangements on PARs vary across countries, the CoG can draw on these mechanisms to support directional setting, decision-making and co‑ordination for PARs. These elements are discussed in the case studies below.

3. Co‑ordinating whole-of-government reforms from the centre

Boxes 6.1-w6.9 outline a range of practices from countries around the CoG in driving PAR. The following practices highlight CoGs’ use of mechanisms in different ways, including:

The overall role and organisation of the CoG in different contexts, from utilising new or binding mechanisms (New Zealand, United Kingdom) to central management and steering role (Australia, Czech Republic, Ireland, United Kingdom) to more of an initiation and oversight role working with, or supporting, other public entities in charge of implementation (Canada, Latvia).

Utilising existing guiding and co‑ordination mechanisms (Korea).

A strong focus on monitoring and management tools (Czech Republic, France).

In addition, many other countries’ CoGs lead PAR activities, including Slovenia, which starting to consider its own PAR and has established an expert group for sustainable public administration development.

Box 6.1. Declaration on Government Reform in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom has acknowledged that the changing environment and landscape in recent years as well as the strong ambitions that the government has across a diverse range of domains, including housing and community, the environment, the health and education systems, unlocking the power of science and around jobs and employment, have required a renewal of government.

The Cabinet Office and Modernisation and Reform Unit has published A Modern Civil Service (UK Goverment, 2021[6]), providing a vision of a skilled, innovative and ambitious civil service equipped for the future, skilled, innovative and ambitious. A consultation effort was undertaken to work with civil servants to shape the civil service and create plans.

Considering this, Cabinet and Permanent Secretaries met and committed themselves to a collective vision for reform, agreeing to immediate action on three fronts:

People: ensuring that the right people are working in the right places with the right incentives.

Performance: modernising the operation of government, being clear-eyed about priorities and objectives in the evaluation of what is and is not working.

Partnership: strengthening the bond between ministers and officials, always operating as one team from policy to delivery, and between the central government and external institutions.

Commitment to these areas was made through a declaration (UK Goverment, 2021[6]) available on the Government Office website, which includes specific priorities and commitments under each of the three areas and specific actions for the year 2021.

Formality and political advocacy are demonstrated through the process and 2021 declaration made by the Cabinet, signed by the prime minister and the head of cabinet: a strong mechanism for clear mandate and political leadership. The declaration also included a clear set of initiatives for each agency to follow, demonstrating good planning.

Source: UK Government (2021[6]), A Modern Civil Service, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1173173/A_Modern_Civil_Service_slide.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2023).

Box 6.2. A more adaptive, agile and collaborative public service in New Zealand

In recognition of the fact that the context and environment have changed over the last 30 years in New Zealand and to acknowledge lessons learnt through the COVID-19 crisis, the country recently implemented a major PAR known as the new Public Service Act 2020.

The act acknowledges the strong foundations of New Zealand and outlines five key areas to help join up public services and secure public trust and confidence in the government. The five areas include:

Unified public service.

Strengthening the Crown’s relationships with Māori.

Employment and workforce.

Leadership.

Organisational flexibility.

The act provides a modern legislative framework and impetus for reform that enables a more adaptive, agile and collaborative public service and includes stronger recognition of the role of the public service in supporting the partnership between Māori and the Crown, including a more practical description of what it means to engage with Māori and support the Māori-Crown relationship.

This reform approach established strong central management and stewardship for the systemic reforms, as enshrined in legislation and rules of the public administration. Each of the five areas includes a clear purpose and goal, a practical identification of what this means for all public servants as well as key systemwide reforms and priorities. Depending on the priorities, specific heads of agencies or senior officials are responsible for enacting the reforms, although it is unclear whether a centralised monitoring approach may be taken.

New Zealand also undertook consultation through surveys and other mechanisms in undertaking this reform, which showed strong support for the overall direction of the reforms.

Flexibility and innovative or contemporary approaches are core to this reform, with one of the five areas allowing provisions for flexible departmental models, joint ventures and joined up budgeting and policy development to specifically deal with complex and cross-cutting issues.

Source: Te Kawa Mataaho Public Service Commission (2023[7]), “An overview of the changes”, New Zealand Government, https://www.publicservice.govt.nz/guidance/public-service-act-2020-reforms/an-overview-of-the-changes/ (accessed on 6 September 2023).

Box 6.3. PAR in the Czech Republic

The Czech Republic has a well-established tradition and methods for designing whole-of-government public administration reform plans. The Czech PAR – Client-oriented Public Administration 2030 – follows the Strategic Framework for the Development of Public Administration 2014-20.

The PAR defines clear priorities for reforming and modernising the public administration The overarching vision of the PAR is to support a citizen-oriented public administration to increase the quality of life of its citizens (Ministry of the Interior, 2020[8]). Achieving the vision is conditional on the fulfilment of five objectives, focusing on public service quality, citizen engagement and efficiency.

The PAR is managed by the Ministry of the Interior and discussed in a specific working group of the Council for Public Administration. The working group is the forum for discussions on the PAR and for monitoring the strategy. It prepares and steers public administration reform, and is responsible for most of the PAR strategy as well as for co-ordination with other line ministries and other concerned bodies, for example through a joint steering committee or other forms of consultation or monitoring. This potential, particularly in decision-making, is only partly used and calls for more political steering and instruments.

While such a plan provides a clear and long-term strategy, it can be challenging to sustain decision-makers’ interest in carrying out such a significant reform, potentially as – apart from streamlining the administration – reforming the public administration is not considered a politically attractive topic. Further challenges can be met when PARs extend over multiple election cycles.

Source: OECD (2023[2]), OECD Public Governance Reviews: Czech Republic: Towards a More Modern and Effective Public Administration, https://doi.org/10.1787/41fd9e5c-en.

Box 6.4. Public administration reforms to address agility and resilience in Ireland, supporting the government now and in the future

Drafted in 2021, the ten-year Civil Service Renewal 2030 Strategy aims to develop a direction for the future of the civil service to respond to the changing environment, including climate and sustainability, geopolitical and demographic changes, housing and healthcare through greater agility and resilience.

Among other things, the 2030 strategy draws on consultation across the civil service, employee surveys and lessons learnt from the COVID-19 pandemic and organisational capability reviews.

The strategy articulates guiding principles, high-level outcomes and strategic priorities and themes. The “How will we deliver” sections establish lower-level outcomes, within three core themes:

1. Delivering evidence-informed policy and services.

2. Harnessing digital technology and innovation.

3. Building the civil service workforce, workplace and organisation of the future.

A set of guiding principles frame the reform approach.

Ireland’s reform approach exhibits a strong centralised approach to civil service renewal, with the central agency – the Civil Service Renewal Programme Management Office – co‑ordinating and driving a lot of the reform. The office works with project managers and secretary general sponsors to implement the plan. It also supports the Civil Service Management Board (CSMB), which is responsible for delivering the actions in the Civil Service Renewal Plan. The Programme Management Office also leads and manages communication and engagement activities. Project managers are assigned to each goal and detailed project plans, with associated outcomes and indicators, are developed to support the delivery of the action plan. Project team members have representation from all levels within the civil service.

The cycle of reform is managed through a ten-year programme of renewal, which provides the means to address complex, long-term issues while focusing on shorter-term outcomes through a cycle of three‑year action plans. Reports are published on an annual basis. Managers report to the CSMB on the progression of their assigned projects.

Flexibility and innovation are supported through the annual Civil Service Excellence and Innovation Awards and the Civil Service Employee Engagement Surveys. In addition, outcomes measurement is used to monitor the impacts of the plan on societal well-being. A key focus of the evaluation is lessons learnt that can be applied to future work and progress.

Sources: Government of Ireland (2021[9]), Civil Service Renewal 2030 Strategy: ’Building on our Strengths’, Department of Public Expenditure and Reform, https://www.gov.ie/pdf/?file=https://assets.gov.ie/135476/ab29dc92-f33f-47eb-bae8-2dec60454a1f.pdf#page=null (accessed on 19 July 2023); Government of Ireland (2021[10]), Civil Service Renewal 2024: Action Plan, https://www.gov.ie/pdf/?file=https://assets.gov.ie/211842/8d223347-9114-43dd-84c5-78f685c63f1b.pdf#page=null (accessed on 6 September 2023).

Box 6.5. Embedding public sector reforms to address trust, future capability, responsiveness and agility from the centre, Australia

The Australian Public Service (APS) has centralised administration but with many decentralised functions such as budget and workforce management and business planning. PAR approaches facilitate a whole-of-government approach through the leadership of a central unit as well as agency heads who are responsible for promoting co‑operation with other agencies and management across structures under the Public Service Act 1999 (Australian Government, 1999[11]).

In 2018, the Australian Government commissioned an independent review of the APS to ensure it is better trusted, future-fit, responsive and agile in meeting the changing needs of the government and the community with professionalism and integrity for years to come.

The resulting reform agenda is built on four pillars, creating an APS that:

Embodies integrity in all that it does.

Puts people and business at the centre of policy and services.

Is a model employer.

Has the capability to do its job well.

The review was spearheaded within the Department of the Prime Minister & Cabinet (PM&C) in Australia, with communications disseminated directly from the prime minister and heads of relevant agencies. Following the independent review and the development of the response and actions, a new APS Reform Office was created to monitor and co‑ordinate the reform efforts from the centre, incorporating views of both the PM&C and the Australian Public Service Commission, with some duties distributed to other agencies. Mechanisms established to spearhead the reform include a strong central management approach with dedicated and centrally appointed staff and resources as well as responding to the challenge to strong central management created by the decentralisation of many functions. This was achieved by combining the legislation around central authority with the legislation of agency head responsibility for collaborative work approaches and achieving shared goals.

The approach focused on a shared vision, including creating an overarching reform narrative through consultation with the government, public administration and community in order to empower staff. A robust and agreed-upon plan for managing the PAR includes a well-defined set of initiatives that has been prioritised and sequenced, each with accountable leads, names and agreed-upon roles. Functions for such staff are stipulated, including communication plans, reporting frameworks and review processes.

Management conditions to support innovation are embedded via an articulated plan principle that implementation of the reform must be fit for purpose, supported by sector capability building to strengthen expertise and using two methods of outcomes-based assessment of whether objectives are being met.

In this case, Australia emphasised the importance of a clearly articulated and shared vision, well-defined initiatives and systems to support accountabilities as the primary enablers. Australia also utilises specific capability reviews of departments, led through the CoG, to help advance and embed the APS reform agenda and to specifically embed a culture of continuous improvement across the APS.

Source: Information provided by an official in the Australian Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet; Australian Government (1999[11]), Public Service Act 1999, https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2019C00057 (accessed on 6 September 2023).

Box 6.6. Public sector reform in Latvia

Political and economic change created the need for a Latvian public administration that could manage public resources in an effective and efficient manner, provide high-quality and accessible public services and serve the public interest in good faith, having the ability to respond swiftly and compete with the private sector for limited human resources in the labour market.

The Latvian government adopted the Public Administration Modernisation Plan 2027 in spring of 2023 and is a medium-term policy planning document that sets out the main lines for development and change in public administration. The plan aims to develop a more co‑ordinated public administration that constantly evolves and adapts to changing social and economic conditions. It continues the path of change launched by the National Administration Reform Plan 2020.

More specifically, the Public Administration Modernisation Plan 2027 aims to implement smart, efficient and open management in all public administration processes, in line with the National Development Plan 2027, by focusing on human needs and proactive national action and implementing evidence-based solutions and cross-sectoral co‑operation, using new methods and digital capabilities, providing understandable and accessible information, providing opportunities for people to participate in policymaking and achieving a balanced representation of public groups.

In the context of the public sector competing with the private sector for limited human resources in the labour market and reform leadership and co‑ordination shared between the State Chancellery and the Ministry of Regional Development and Environmental Protection, Latvia addressed the need to drive change in an accountable way and provide space for innovation and participation by sharing management between the centrally located State Chancellery and ministries for this reform episode.

A management plan was established through the combination of communication plans, metrics for progress measurement, the monitoring of measurements and scope for changes to be made to the plan as it progressed. The last feature also establishes space for innovation, as does the stated focus on co‑operation and flexibility over bureaucratic processes and normative approaches.

Source: Information provided by officials in the Latvian government.

Box 6.7. Public sector reforms on digital technologies and the use of data, changing and less hierarchical workplace designs and multi-generational work in Canada

In 2020, the Canadian government embarked on a reform agenda to respond to the changing environment including a greater focus on digital technologies and the use of data, changing and less hierarchical workplace designs and multi-generational work. After consultation with public servants across the country, a Beyond2020 agenda was implemented, which was articulated as focusing on mindsets and behaviours to achieve a more agile, inclusive and equipped public service. This strategy was published by the central Privy Council Office, yet Canada is also pursuing the implementation of such reforms throughout all public administration departments and agencies.

Beyond2020 aimed to implement a flexible reform framework to achieve agility, inclusiveness and a well-equipped service that was sensitive to unique organisational, individual and regional contexts and practicalities.

Pursuing a decentralised and highly customised approach to reform can be a challenge for countries with typically centralised management structures. The topic of reform is also challenging in that it is, for example, hard to measure reform to mindsets and behaviours of staff in view of building agility, inclusiveness and support for performance. In this round of reform, Canada employed network strategies to meet these objectives, replacing a strong centre-driven plan with a strategy to drive control of the reform through place-based champions.

Source: Government of Canada (2019[12]), From Blueprint to Beyond2020, https://www.canada.ca/en/privy-council/services/blueprint-2020/blog/blueprint-beyond-2020.html (accessed on 19 July 2023).

Box 6.8. Promoting PAR for proactive administration in Korea

Korea has a strong central administration, with the central government of South Korea (CoG) long devoting substantial efforts to reorganising central agencies, improving the efficiency and performance of the government under the framework of new public management, reforming regulations and implementing digital government utilising information and communication technology and artificial intelligence.

Korea has emphasised the importance of a behavioural approach in its PAR. The president emphasised in 2019 that public officials should undertake proactive administrative actions. Consequently, a joint taskforce was established with personnel from the relevant agencies, including from CoG institutions.

Korea also considered how to institutionalise this concept of proactive administration to ensure it was a sustainable reform, including reconsidering scrutiny measures and incentivising this approach through promotions, awards and other rewards.

CoG functions within the Ministry of Personnel Management, along with the Office for the Prime Minister and others, became leading agents for change, supporting the institutionalisation of this reform.

This type of reform demonstrates strong centralised leadership and co‑ordination. It also emphasises the need to embed such reforms sustainably into the broader public administration system, including through legal levers and incentives.

The reform approach also includes engagement with citizens and other stakeholders, who can provide input into processes for awards.

This PAR includes consideration of the full reform cycle, not least requirements for central and line agencies to complete action plans, and is monitored through annual agency performance cycles, with full results reported to the cabinet meeting presided by the president.

Source: Kim, P. (2022[13]), “A behavioral approach to administrative reform: A case study of promoting proactive administration in South Korea”, https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/PAP-08-2022-0093/full/pdf?title=a-behavioral-approach-to-administrative-reform-a-case-study-of-promoting-proactive-administration-in-south-korea (accessed on 6 September 2023).

Box 6.9. CoG institutional support and monitoring for PAR Services Public+ in France

The Services Publics + programme aims to mobilise reforms to continuously improve the user experience within public services. It is led by a CoG department of the Ministry of Public Transformation and co‑ordinated by two strategic committees and an operational monitoring committee, demonstrating a level of overall co‑ordination, formed for monitoring:

The Direction interministérielle de la transformation publique (DITP) is in charge of deploying the transformation programme. The DITP also monitors the implementation of the French government’s priority reforms in liaison with local ministries and prefectures.

An Inter-ministerial Committee for Public Transformation, led by the Ministry of Public Transformation, has been set up to ensure the operational implementation, monitoring, inter‑ministerial co‑ordination and political steering of the Action Publique 2022 reform plan. It brings together members of the government two or three times a year and is chaired by the prime minister; the DITP provides the secretariat.

A high-level strategic committee brings together central administration directors and the Minister for Public Transformation.

An operational monitoring committee brings together directors of administration (at the local level) to discuss the monitoring of commitments and indicators.

Each administrative network implements this PAR, making commitments by clarifying them and translating them into its own context. Participating public agencies are then required to self-assess their compliance with the nine Services Publics + commitments, identifying priority areas for improvement.

The indicators measured and displayed are designed to meet the priority expectations of users (speed, reachability, personalisation, etc.) in their relations with public services, as well as with the Services Publics + commitments. Data are measured as close as possible to the user, at the local level, and are updated as regularly as possible (a minimum of year y-1). All main public services of the French state are represented (over 2.5 million employees), i.e. some 40 networks that are transparent about the quality of their service. The data published are those produced by each of the public services involved in the Services Publics + programme.

Sources: Government of France (2019[14]), Services Publics +, https://www.modernisation.gouv.fr/ameliorer-lexperience-usagers/services-publics (accessed on 6 September 2023); Government of France (2022[15]), Action Publique 2022 : pour une transformation du service public, Inter-ministerial Directorate of Public Transformation.

Guiding public sector innovation reform from the centre

Recent challenges have shown that governments need to integrate more innovative approaches into policymaking and decision-making (OECD, 2023[1]). As of 2018, more than half (56%) of OECD member countries claimed a role in promoting modernisation or innovation (OECD, 2018[16]). A more innovative government is a core focus of many PARs CoGs are co‑ordinating or leading. CoGs are using different mechanisms to do so. For example, in France, the Inter-ministerial Committee of Public Transformation in the Prime Minister’s Office has set up and manages a fund to support the transformation of government activities. Spain’s National Office of Foresight and Strategy works to foster strategic foresight and innovation. The innovation lab within the Romanian CoG supports innovation.

Many CoG are responsible for fostering a more innovative public administration. The OECD Declaration on Public Sector Innovation (OECD, 2023[17]) recognises governments need to act as stewards of innovation in the public sector and CoGs are these stewards. Boxes 6.10-6.13 describe additional experiences from CoGs in Bulgaria, Costa Rica, France and Latvia guiding public sector innovation reforms.

Box 6.10. The Fund for Transformation of Public Action in France

Based on the logic of return on investment, this fund enables inter-ministerial initiatives to strengthen innovation in the French public sector. Priorities include the improvement of services to citizens and companies, and of public officials’ working environment, as well as increase in the efficiency of public administration. Public organisations present their applications to the call for innovative projects to benefit from funding and stewardship, which are awarded dependent on the benefits in efficiency and productivity that are envisaged and the impacts on their users.

The programme has been piloted and managed by the Inter-Ministerial Committee of Public Transformation, which is part of the Ministry of Public Transformation and Civil Service, but whose range of action enables cross-sectoral co‑ordination and supports the collaborative initiatives for public sector transformation.

With lessons learnt, France will continue to consider how to fund and integrate innovation into its support of innovative capacity through funding models.

Source: Information provided by representatives of the Government of France.

Box 6.11. PAR and the National Open Government Strategy, Costa Rica

In response to factors such as lower levels of trust in the government, rising unemployment and increasing demands from citizens for greater participation in and oversight of government decision-making, the Costa Rican government has pursued PARs through a National Open Government Strategy. The objectives include strengthening democracy, preventing and combating corruption, improving the quality and efficiency of public services, and achieving more inclusive societies.

The National Open Government Strategy uses an improved central management relationship between three key agencies, including the Ministries of the Presidency, Planning and Economic Policy, and Finance.

The centrally driven mandate is further strengthened by establishing the strategy as one of the pillars of the existing and broader National Development and Public Investment Plan 2023-2026, through a national policy on open government. They declared that open government was in the public interest by decree and established a National Open Government Commission. The commission is in the stage of public consultation on the six commitments of the Open State Action Plan: employment, economic recovery, security, open justice, open parliament, and integrity and anti-corruption.

The reform is managed through two-year action plans with an independent reporting mechanism. To establish some flexibility and space for innovation, open government contact points were utilised at the local level to design the second action plan to enhance inter-institutional co‑operation.

Source: OECD (2016[18]), Open Government in Costa Rica, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264265424-en.

Box 6.12. Driving innovation from the centre in Latvia

In response to the recognition of the need to raise the overall efficiency and effectiveness of public administration by promoting good governance and improving the level of staff competency in Latvia, the State Chancellery of Latvia launched an innovation lab and is continuing to enhance the role and impact of the lab with support from the European Commission and in partnership with the OECD.

The key priorities of the lab are to drive PARs, including the reduction of unnecessary bureaucracy and, therefore, the introduction of a zero-bureaucracy approach. In this project, part of the overall goal was to utilise an innovation lab to also introduce and embed innovation into the public administration, to make it faster and more efficient to address topical or old problems, come up with the necessary solutions, and develop and test prototypes.

The lab is driven from the Chancellery, demonstrating top-down central commitment and management. It was also included in the government’s action plan demonstrating clear political support.

Key enablers for this approach to PAR have included developing a clear vision and iterating on this vision depending on user needs, promoting learning from other countries' good practices, relying on dedicated and knowledgeable staff to lead the reforms and processes through the lab and building broader capability through the processes the lab undertakes.

Some challenges around this PAR included a gap between design and implementation, a lack of expertise and a lack of funding to drive sustainable change.

Source: Government of Latvia (2019[19]), Creation of 3 Innovation Labs in Latvia, https://www.mk.gov.lv/lv/media/538/download (accessed on 6 September 2023).

Box 6.13. Stewarding communities of practice in Bulgaria’s public administration

Building innovative networks of expertise

The CoG in Bulgaria has sought to create an innovative networking approach and communities of practice within the public administration. These networks have proven useful in supporting innovative capacity building and administrative reforms. This has included the administration of the latest procedural and legal amendments, conducting stakeholder consultations and garnering support for important initiatives based at the CoG. The CoG shares administrative responsibility for such networks with the Institute of Public Administration, the leading institution for most in-person events.

To enhance peer learning, promote the exchange of expertise and encourage day-to-day communication between the participants, some of these networks have employed the use of instant messaging software application Viber groups and communities. Larger networks have been observed to include several hundred participants via the Viber group, limited not only to representatives of the public administration but members of academia and think tanks as well. The use of Viber has also aided in deconstructing existing silos within the public administration. Additionally, all participants have direct access to their counterparts in neighbouring ministries and public agencies.

Source: Information provided by representatives from the Council of Ministers of the Republic of Bulgaria.

4. Common challenges and enablers

Through a synthesis of information collected through country practices, desk research, interviews and the experiences shared by participants of the OECD informal Expert Group on Strategic Decision Making at the Centre of Government, the following key considerations can be identified.

Common challenges

The composition of CoGs and their roles and mandates varies greatly (OECD, 2020[4]) including utilising more centralised management approaches or devolved approaches. The latter can be useful in diffusing reforms yet lose the strong political leadership and direction central management can offer. Conversely, a strong centralised system can also result in a reduction of grassroots innovation.

CoGs do not have ultimate control or influence on the implementation and impact of PARs. In this context they need to consider how they steward sustainable reform without control. CoGs need to foster an enabling environment where all actors can drive systemic change.

Alignment and/or integration of PAR objectives and priorities into a government’s broader strategic planning documents is important. Yet this can result in challenges in prioritising policy reforms versus internal reforms for agencies with a common view of PAR goals.

The financial sustainability of PARs is important. Ensuring that PARs are well planned and costed is a significant challenge and not all countries have processes to understand the financial cost or impact of reforms.

The public administration needs to correspond to its needs and meet the principles of contemporary democracy and public administrations, including political neutrality (Žurga, 2016[20]). Thus, PARs still need to ensure that administrations are in line with these requirements.

Common enablers

Strong overarching strategies for systemic and holistic PARs must be utilised. CoGs need to consider how to make use of good practices around strategic planning for driving PARs, aligning PAR priorities with broader government priorities and international commitments.

CoGs and the structures and mechanisms supporting PAR must be fit for context. Approaches to reform must be realistic and cognisant of the context.

CoGs’ experiences demonstrate the importance of clarifying roles and mandates when working on issues over which they do not have a direct sphere of influence, including PARs.

There is a general agreement that sustained political commitment and support at the top level are key success factors for the implementation of PARs from the centre.

Management or co‑ordination of the full PAR reform cycle should be taken into account, including monitoring of reforms and communication of results, even if not all roles are performed by the CoG.

Countries also highlight the role of communicating and engaging with civil servants and citizens as an important part of gaining advocacy and building trust.

References

[11] Australian Government (1999), Public Service Act 1999, https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2019C00057 (accessed on 6 September 2023).

[12] Government of Canada (2019), From Blueprint to Beyond2020, Privy Council Office, https://www.canada.ca/en/privy-council/services/blueprint-2020/blog/blueprint-beyond-2020.html (accessed on 19 July 2023).

[15] Government of France (2022), Action Publique 2022 : pour une transformation du service public, Inter-ministerial Directorate of Public Transformation.

[14] Government of France (2019), Services Publics +, Inter-ministerial Directorate of Public Transformation, https://www.modernisation.gouv.fr/ameliorer-lexperience-usagers/services-publics (accessed on 6 September 2023).

[10] Government of Ireland (2021), Civil Service Renewal 2024: Action Plan, Department of Public Expenditure and Reform, https://www.gov.ie/pdf/?file=https://assets.gov.ie/211842/8d223347-9114-43dd-84c5-78f685c63f1b.pdf#page=null (accessed on 6 September 2023).

[9] Government of Ireland (2021), Civil Service Renewal 2030 Strategy: ’Building on our Strengths’, Department of Public Expenditure and Reform, https://www.gov.ie/pdf/?file=https://assets.gov.ie/135476/ab29dc92-f33f-47eb-bae8-2dec60454a1f.pdf#page=null (accessed on 19 July 2023).

[19] Government of Latvia (2019), Creation of 3 Innovation Labs in Latvia, https://www.mk.gov.lv/lv/media/538/download (accessed on 6 September 2023).

[13] Kim, P. (2022), “A behavioral approach to administrative reform: A case study of promoting proactive administration in South Korea”, Public Administration and Policy, Vol. 25/3, pp. 310-322, https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/PAP-08-2022-0093/full/pdf?title=a-behavioral-approach-to-administrative-reform-a-case-study-of-promoting-proactive-administration-in-south-korea (accessed on 6 September 2023).

[8] Ministry of the Interior (2020), Client-oriented Public Administration 2030.

[17] OECD (2023), Declaration on Public Sector Innovation, OECD, Paris, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/oecd-legal-0450 (accessed on 6 September 2023).

[1] OECD (2023), Global Trends in Government Innovation 2023, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/0655b570-en.

[2] OECD (2023), OECD Public Governance Reviews: Czech Republic: Towards a More Modern and Effective Public Administration, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/41fd9e5c-en.

[3] OECD (2023), “Survey on strategic decision making at the centre of government”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

[5] OECD (2023), The Principles of Public Administration, OECD, Paris, https://www.sigmaweb.org/publications/principles-public-administration.htm#languages.

[4] OECD (2020), Policy Framework on Sound Public Governance: Baseline Features of Governments that Work Well, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c03e01b3-en.

[16] OECD (2018), Centre Stage 2: The Organisation and Functions of the Centre of Government in OECD Countries, OECD, Paris, https://web-archive.oecd.org/2021-05-18/588642-report-centre-stage-2.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2023).

[18] OECD (2016), Open Government in Costa Rica, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264265424-en.

[7] Te Kawa Mataaho Public Service Commission (2023), “An overview of the changes”, New Zealand Government, https://www.publicservice.govt.nz/guidance/public-service-act-2020-reforms/an-overview-of-the-changes/ (accessed on 6 September 2023).

[6] UK Goverment (2021), A Modern Civil Service, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1173173/A_Modern_Civil_Service_slide.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2023).

[20] Žurga, G. (2016), “In search of sustainable public administration: What should, could, or must be done”, Romanian Journal of Political Science, https://www.midwest.edu/upload/07library_05-04-02thesis/Public%20Administration%20English%20Thesis(PA)/7_In%20search%20of%20sustainable%20public%20administration(2017).pdf (accessed on 6 September 2023).