The information people are exposed to can affect their perceptions of, and trust in, public institutions. This chapter examines the relation between people's trust in news media, their news consumption habits, their criteria for judging the credibility of a news story and their trust in the government. It then examines how people view public communication, both with regard to administrative services and major policy reforms. Finally, it explores people’s expectations of government use of evidence in public decision making, and how these views contribute to trust.

OECD Survey on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions – 2024 Results

5. Trust and information integrity

Abstract

The information people are exposed to can participate in shaping their perceptions of, and trust in, public institutions. This is done through conversations with other people, traditional and social media, information available through research and academic institutions, as well as direct communication from public institutions themselves. This mediated information makes up a significant part of people’s understanding of how institutions operate and what they do (Marcinkowski and Starke, 2018[1]). This holds particularly true for government actions related to policy design and implementation which few people directly observe or experience, but that nevertheless influence people’s perceptions of public institutions.

A solid information ecosystem providing quality information is vital for people to make informed judgements about government actions and hold public institutions accountable. Along with an education system that equips people with the cognitive and critical skills and knowledge to process the information, this ecosystem helps individuals form “sceptical trust” in public institutions. Such sceptical trust is crucial in protecting democracy from the threats of disinformation (Norris, 2022[2]). However, disruptive trends such as the proliferation of mis and dis information, polarising speech on mass communication channels, informational echo chambers and decline in media pluralism and diversity can weaken the information environment. In this context, OECD work defines a framework to reinforce and protect information integrity, defined as “information environments that are conducive to the availability of accurate, evidence-based, and plural information sources and that enable individuals to be exposed to a variety of ideas, make informed choices, and better exercise their rights” (OECD, 2024[3]).

In a first for the Trust Survey, this new chapter explores how people consume news about current affairs and government action, perceive media and governmental communication, and how these consumption habits and perceptions relate to people’s trust in public institutions. It relies on additional questions in the 2023 Trust Survey that concern people’s media usage patterns on the one hand and their perceptions of public communication on the other. These questions were added to provide additional evidence on how information from public and media sources impact perceptions of public institutions’ actions and how this affects trust in these institutions.

5.1. The media environment and media consumption patterns affect trust in public institutions

In recent years, concerns over the reliability and integrity of information have grown, with significant implications for democracy (OECD, 2024[3]). The undermining of a common reality based on factual evidence deepens societal divisions and makes it more difficult to build the consensus necessary to address policy challenges. It can also be exploited by malign actors in disinformation campaigns, whether domestically or internationally orchestrated, impacting various policy areas, from public health to national security, and even the climate crisis (OECD, 2022[4]).

Worries about telling apart accurate and false content are more widespread. In the Trust Survey, an average of 11% identified mis- and dis-information as one of the main three issues facing their country (Figure 5.1); and in Czechia, Korea and the Slovak Republic, the share exceeded 20%.

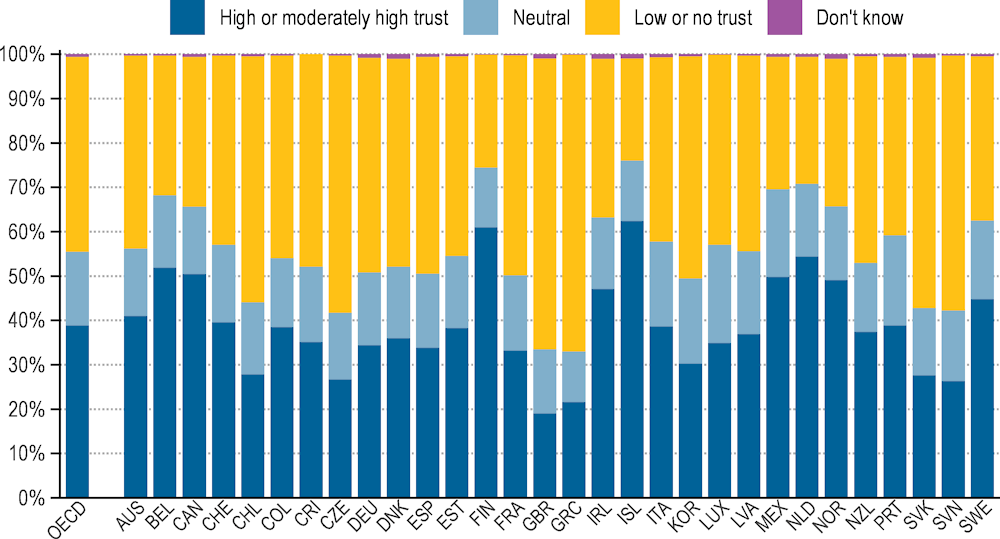

Moreover, many people have concerns over the trustworthiness of media. As part of the growing difficulties with the evolution of the information environment, trust in traditional media is also suffering. On average, 39% of individuals in OECD countries have high or moderately high trust in news media, mirroring levels of trust in the national government, while 44% report low to no trust in the media (Figure 5.1). Only in Belgium, Canada, Finland, Iceland and the Netherlands does the majority of the adult population have high or moderately high trust in the news media. The average level of trust in news media across OECD countries has nevertheless remained steady between the 2021 and 2023 waves of the OECD Trust Survey, although with large variation in some countries (Figure 5.2).

Figure 5.1. More people distrust rather than trust the news media

Share of population who indicate different levels of trust in news media, 2023

Note: The figure shows the within-country distributions of responses to the question “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust the news media?”. A 0-4 response corresponds to ‘low or no trust’, a 5 to ‘neutral’ and a 6-10 to ‘high or moderately high trust’.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

An independent and pluralistic media environment is a fundamental principle of democracy as it facilitates the public’s ability to scrutinise the actions of high-level political officials and policy-makers and to make informed choices. For instance, Guriev and Treisman (2019) raise the spectre of "informational autocrats" coercing citizens into compliance through information manipulation (Guriev and Treisman, 2019[5]). While trust in the national government and trust in the media system are not necessarily related – and may at times even be at odds – in the long run, persistent distrust in the media ecosystem and the information it provides leaves individuals with only the choice of trusting government institutions blindly or to distrust both the media and government. As such, information integrity in society is pivotal for trust in public institutions, and more broadly, democracy.

Trust in the media and trust in the national government are moderately correlated at the cross-country level. Moreover, at the individual level, people who trust the media are more than twice as likely to trust the government compared to those who do not. Considering the relatively low levels of trust in the media and its recent decline in many countries, this is concerning for democracies worldwide. This situation highlights the importance of promoting and preserving information integrity to enhance trust in institutions and prevent unscrupulous actors from exploiting the lack of trust for the wrong purposes. Nonetheless, there are a fair number of OECD countries where people are far more trusting of the national government than of media (Denmark, Greece, Luxembourg, New Zealand, Switzerland, United Kingdom). The opposite is also true in some countries (Czechia, Finland, Latvia, Iceland, Netherlands).

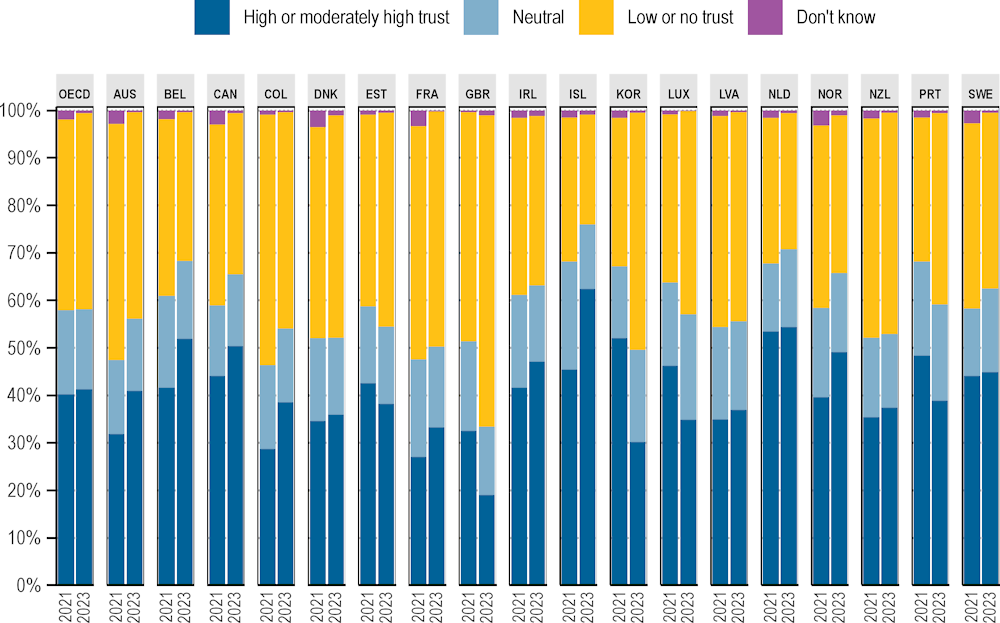

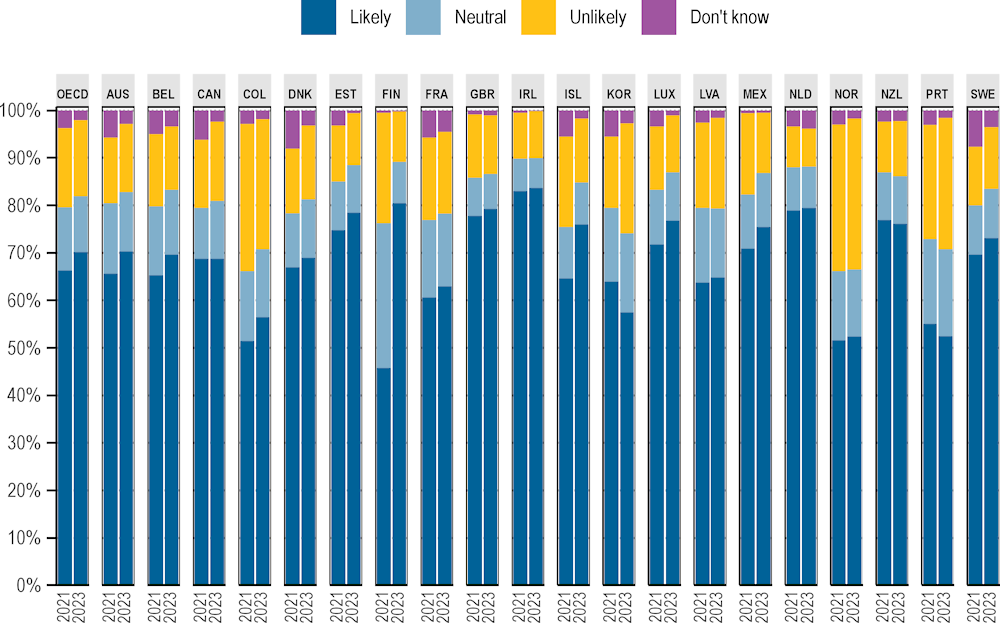

Box 5.1. Spotlight on change: Trust in news media

On average levels of trust in news media has not changed between 2021 and 2023 (Figure 5.2). However, large improvements in trust are observed in Belgium, Colombia and Iceland, while trust in news media decreased significantly in Korea, Luxembourg and the United Kingdom.

Figure 5.2. Average trust in news media did not change between 2021 and 2023

Share of population who indicate different levels of trust in the news media, 2021 and 2023

Note: The figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the question “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust the news media?”. A 0-4 response corresponds to ‘low or no trust’, a 5 to ‘neutral’ and a 6-10 to ‘high or moderately high trust’. “OECD” presents the unweighted average of responses across countries, for the listed countries with available data for 2021 and 2023.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2021 and 2023.

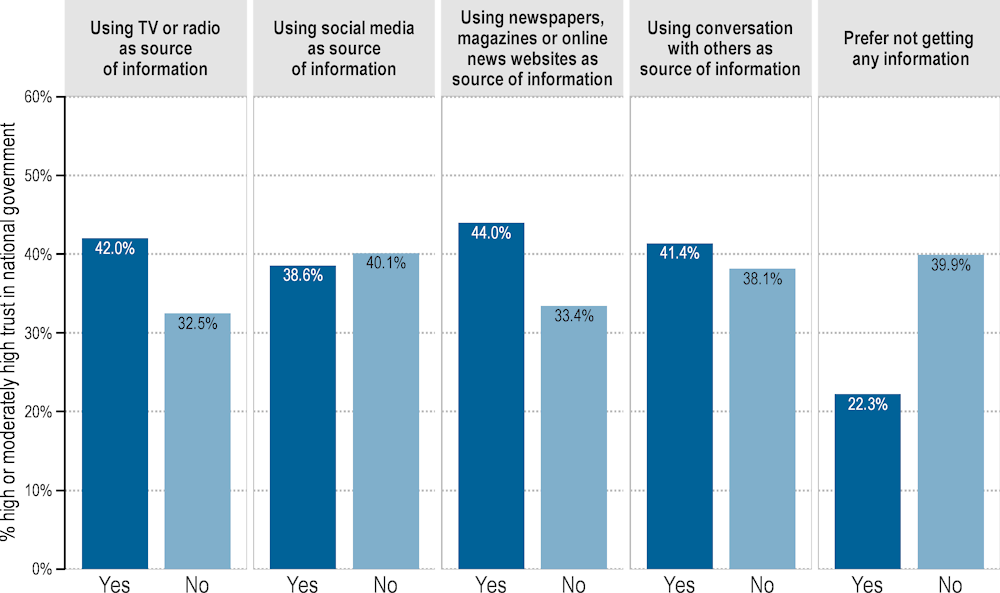

People’s trust in government is found to be closely related to their news consumption habits. Only 22% of those who prefer not to follow political news report high or moderately trust in the government, while the share is 40% among those who follow the news in some way (Figure 5.3). Additionally, individuals who keep up with politics or current affairs through TV, Radio, or written press tend to trust the national government more than those who do not use these media. However, trust levels are virtually the same among those who use social media for news (39%) and those who do not (40%). This may be because news consumption via social media, in turn, is not conducive to high political knowledge (Castro et al., 2022[6]). Similarly, there is little difference in trust between those who discuss news with friends or family (41%) and those who don’t engage in such conversations (38%). Of course, these associations may also owe to socio-economic factors that influence people’s choices of media or interest in news (Strömbäck, Djerf-Pierre and Shehata, 2016[7]; Norris, 2000[8]).

Figure 5.3. Readers of the written press are more likely to trust the government

Share with high or moderately high trust in the national government by whether they obtain information about politics or current affairs from the named source, OECD, 2023

Note: The figure shows the share with high or moderately high trust in the national government, depending on whether they use the media or information source about politics and current affairs on a typical day. The share with high or moderately high trust corresponds to respondents who select an answer from 6 to 10 to the question “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust the national government?”. Whether or not the respondent uses the selected source of information is derived from their answer(s) to the question “On a typical day, from which of the following sources, if any, do you get information about politics and current affairs?”, for which they can select all options that apply. The figure shows the unweighted OECD averages.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

5.2. The current information ecosystem has made it harder for individuals to understand and assess the trustworthiness of information

The pluralism of media markets and supply of quality journalism have declined in recent years. This is simultaneously a result of shifting news consumption trends triggered by technological changes and resulting market disruptions, and a potential contributor to and effect of low trust in media. According to Reporters without Borders’ World Press Freedom Index, the proportion of OECD countries in which the quality of journalism was ranked as ‘good’ was 49% in 2015, falling to 26% by 2021 (OECD (2022[9]) based on(Reporters without Borders (2022[10])).

In most OECD countries, economic rather than legislative or political constraints exert the most negative influence on quality of the news media. In the written press, competition from digital platforms that reap the bulk of advertising revenues has led to reductions in newsroom staff, consolidation in the industry, and the shutdowns of newspapers particularly at the local level (OECD, 2021[11]; Matasick, Alfonsi and Bellantoni, 2020[12]). Few big news brands are growing their subscriptions base on a “winner-takes-most” dynamic while others struggle for revenues (Newman et al., 2023[13]). Commercial incentives contribute to a trend for sensationalist content that performs well with algorithms and time-poor audiences (Matasick, Alfonsi and Bellantoni, 2020[12]). In parallel to these shifts in the written press, the last three decades have seen significant liberalisation in media and television sectors globally, leading to the rise of satellite and cable television. Consequently, the number of private channels has increased dramatically, changing the relationship between private and public broadcasting sectors. For instance, the number of channels in Europe grew from less than 100 in 1989 to more than 11 000 by 2019 (Papathanassopoulos et al., 2023[14]). The television environment has therefore changed from low choice to high choice, leading to fragmentation of audience attention (Kleis Nielsen, 2012[15]). These changes have in part facilitated the creation of larger and fewer dominant groups in the media sector, resulting in an industry that’s more concentrated and populated by multimedia conglomerates (Papathanassopoulos et al., 2023[14]).

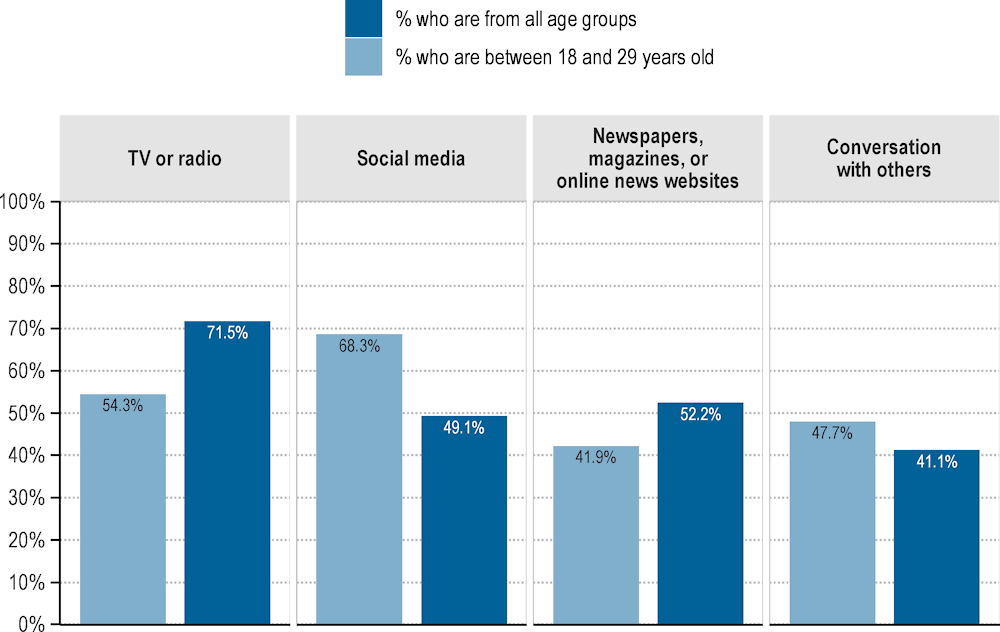

In this context, most people across the OECD still obtain their news about politics and current affairs from “traditional” sources (TV, radio, written press), although this is changing among younger generations. On a typical day, seven out of ten (72%) respondents receive their news from television or the radio, while half (52%) use newspapers, magazines, or online news websites (Figure 5.4). Social media is a news source for almost half (49%) of people; and individuals estimate that about a third of their information comes from social media. However, for younger people, social media has become the primary news source, with 68% obtaining news this way, surpassing the 54% who watch television or listen to the radio for news; and the 42% who read newspapers or magazines. However, a small share obtains their news exclusively from social media: 14% of under-30-year-olds estimate that they obtain 80% or more of their news on social media.

Figure 5.4. Younger people rely more on social than traditional media

Share of population who indicate that they get information about politics and current affairs from respective source, unweighted OECD average, 2023

Note: The percentages show the unweighted OECD average. The shares are derived from the response to the question “On a typical day, from which of the following sources, if any, do you get information about politics and current affairs?”. Respondents were able to select all responses that applied.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

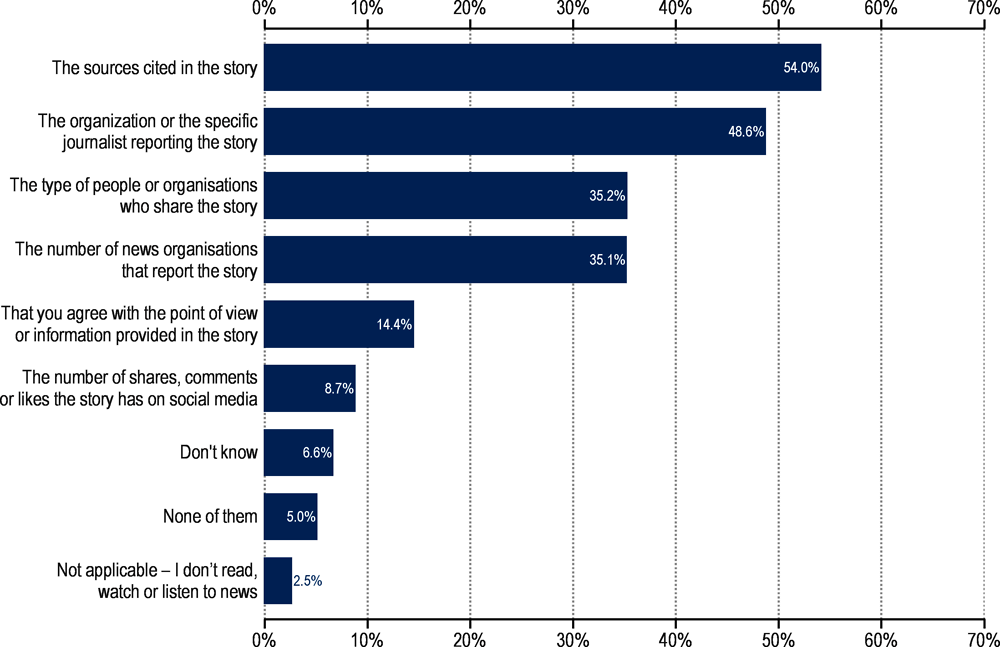

The fragmentation of the media landscape can make it more difficult for individuals to judge whether a given news story is trustworthy. People tend to use a variety of criteria to assess whether they deem a story credible. Across the OECD, the most commonly cited criterion are the sources cited (54%), followed by the organisation or journalist reporting the story (49%). The number of organisations reporting on the story is likewise an important criterion, cited by 35% of respondents (Figure 5.5). In addition to these criteria that can equally well apply to traditional and new types of media, two social-media related criteria likewise play a role: 35% consider the type of people or organisations who share the story on social media as among the three most important factors when assessing news trustworthiness, while 9% rely on the number of shares, comments or likes the story has on social media. 14% also take into consideration whether they agree with the point of view or information provided in the story; and 5% do not rely on any of the suggested criteria.

A higher share of people aged 50 and above rely on the journalist or organisation reporting on the story, and the number of organisations reporting as a determining factor in assessing trustworthiness. They rely less on the number of shares and likes. However, different age groups otherwise tend to use similar criteria. These broad categories may however be hiding differences within each media category: For example, findings from the Reuters survey suggest that on video- and image-based platforms such as TikTok, users pay more attention to influencers than journalists, while the opposite is true for more text-based platforms such as Facebook and X (Newman et al., 2023[13]).

Figure 5.5. A majority state that they rely on a news item’s cited sources as a determining factor in its trustworthiness

Share that selected the named factor as mattering the most in deciding whether the news is trustworthy, OECD, 2023

Note: Each share corresponds to the unweighted OECD average of the response to the question “When you read, watch or hear news, which of the following factors matter the most to you in deciding whether the news is trustworthy?”. Respondents were able to choose up to three response options.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

In addition to assessing the trustworthiness of information, individuals also need to comprehend the information provided to them to form accurate judgments. However, news media does not always communicate in a way that benefits people with different levels of background knowledge. A cross-country study based on focus groups in Brazil, India, the United Kingdom and the United States and a review of BBC economics coverage in the UK highlighted that many find news content unrelatable and unrepresentative of their realities (Arguedas et al., 2023[16]; Blastland and Dilnot, 2022[17]). In a 46-country population survey by the Reuters Institute, 30% of respondents, concentrated among those with lower educational attainment, found it difficult to understand economic and financial news (Newman et al., 2023[13]). People who find it difficult to understand or relate to the information are at a disadvantage when trying to form an opinion on government actions and policies. This can result in weaker democratic accountability, increased susceptibility to disinformation and simplistic content, and it may also influence political agency.

5.3. Effective and inclusive government communication can enhance trust in public institutions

In addition to journalists, social media influencers and peers, public institutions can also serve as sources of information. These entities can disseminate information directly via public websites, informational campaigns, and press conferences, or indirectly, through the information passed on to journalists by high-level political officials and civil servants. This provision of information is one aspect of public communication, which encompasses the “exchange of information between government and citizens, and the dialogue that ensues from it” (OECD, 2021[18]).

Similar to the connection between media and trust, public communication—defined separately from political communication and with a solid governance ensuring it is used as a public good—can both build and damage trust in institutions. On the one hand, public communication can raise awareness of government actions or positions on policy issues, which can increase perceptions that the government is delivering for citizens. It can also be understood as a service and, via the exchange of information, can substantially improve outcomes for users and in turn increase their satisfaction with institutions. Public communication can also help institutions demonstrate and reinforce their commitment to values associated with higher levels of trust (openness, integrity, fairness), but also show responsiveness by listening and responding to the population’s concerns and preferences. On the other hand, communication that is perceived as inaccurate, inaccessible, politically biased or irrelevant can lead the public to perceive institutions as unreliable or untrustworthy.

The current media landscape has significantly enhanced the need for solid public communication with a robust governance framework. Digital channels allow anyone to potentially reach and influence a broad audience (Matasick, Alfonsi and Bellantoni, 2020[12]), enabling a larger number of actors to participate in the information space but creating large challenges for the information ecosystem and trust in institutions (OECD, 2024[3]). Concurrently, digital channels offer public institutions new methods to engage with the public and gather insights to better tailor communication strategies to various audiences, and help the population be better informed about government actions.

In the Trust Survey results, we find similar patterns of satisfaction with public communication as those found between day-to-day interactions and complex policy challenges. Indeed, when it comes to information about administrative services, a large majority of people in most countries – and 67% on average across countries- think that clear information would be easily available (Figure 5.6). The share of people confident that government information would be easily accessible has also increased between 2021 and 2023 (Figure 5.7), but it appears to have only a small positive association with trust in the national civil service and no significant relationship with trust in the national government (Chapter 1 and Annex A).

Figure 5.6. Two thirds of people judge information about administrative services to be easily available

Share of population who find it likely or unlikely that information on an administrative service would be easily available if needed, 2023

Note: The figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the question “If you needed information about an administrative service (for example obtaining a passport, registering a birth, applying for benefits, etc.), how likely do you think it is that clear information would be easily available?” The “likely” proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale; “neutral” is equal to a response of 5; “unlikely” is the aggregation of responses from 1-4; and “don’t know” was a separate answer choice. “OECD” presents the unweighted average of responses across countries.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

Box 5.2. Spotlight on changes: Perception of the ease of finding administrative information

On average, the share of people who find likely that information would be easily available about administrative services increased by 4 percentage points between 2021 and 2023 (Figure 5.7). The largest increase was observed in Finland and Iceland.

Figure 5.7. On average across countries, the share of people who think they can easily find information about an administrative service has risen by four percentage points compared to 2021

Share of population who find it likely or unlikely that clear information would be easily available about administrative services, 2021 and 2023

Note: The figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the question “If you needed information about an administrative service (for example obtaining a passport, registering a birth, applying for benefits, etc.), how likely do you think it is that clear information would be easily available?” in 2021 and 2023 waves. The “likely” proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale; “neutral” is equal to a response of 5; “unlikely” is the aggregation of responses from 0-4; and “don't know” was a separate answer choice. “OECD” presents the unweighted average of responses across countries, for the listed countries with available information for 2021 and 2023.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2021 and 2023.

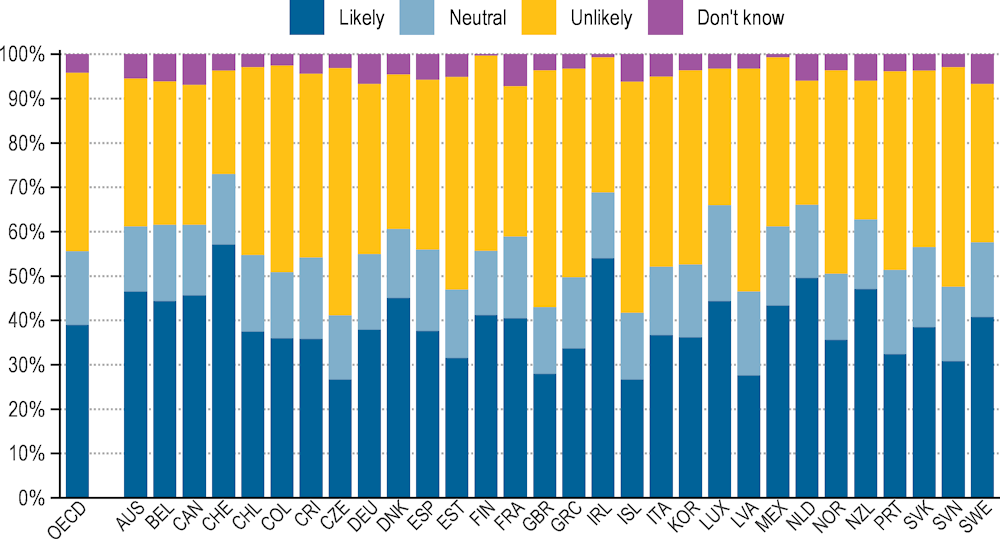

When communicating about policy reforms, the results are different and show interesting results for action to enhance trust. Indeed, there is an even split between people who say the government would likely explain the impact of reforms (39%) and those who are sceptical (40%) (Figure 5.8). Despite its challenges, effective communication about policy reforms can yield significant gains for trust in the national government. This type of communication may also be perceived as being closer to political communication, and therefore appears important for people in assessing whether government is trustworthy.

Figure 5.8. Four in ten believe that government clearly communicates about reforms

Share of population who find it likely or unlikely that the national government would clearly explain how the respondent would be affected by a reform, 2023

Note: The figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the question “If the national government was carrying out a reform, how likely do you think it is that it would clearly explain how you will be affected by the reform?” The “likely” proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale; “neutral” is equal to a response of 5; “unlikely” is the aggregation of responses from 1-4; and “don't know” was a separate answer choice. “OECD” presents the unweighted average of responses across countries.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

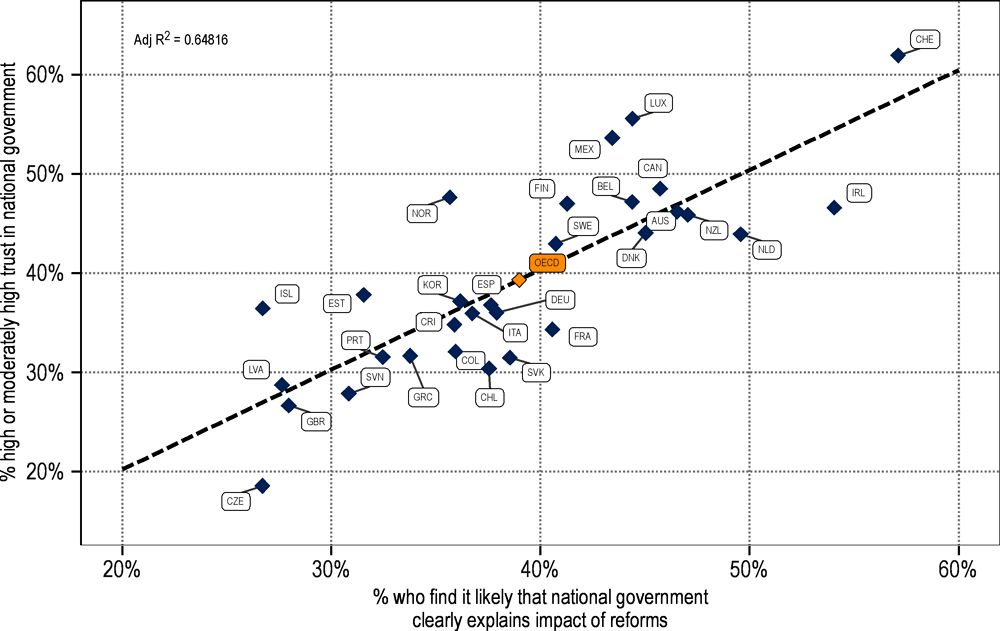

Perceptions of the government's communication regarding the impact of reforms are strongly associated with trust in the national government (Figure 5.9). When examining a variety of public governance drivers of trust in national government at the same time, people's confidence in the government's ability to explain how they would be impacted by a certain reform is among the variables that have a positive association with trust in the national government (Chapter 1 and Annex A).

Figure 5.9. Countries in which people think government communicates well about reforms tend to have higher trust in the national government

Share of population with high or moderately high trust in the national government (y-axis) by share of people that think it is likely government will clearly explain how they will be affected by a reform (x-axis), 2023

Note: The figure presents the relationship between the proportion of people that have high or moderately high trust in the national government, based on the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale to the questions: 1) “On a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, in general how much do you trust the national government?,” and 2) “If the national government was carrying out a reform, how likely do you think it is that it would clearly explain how you will be affected by the reform?”, on the proportion who think it is likely, based on the aggregation of the responses from 6-10, that the national government clearly communicated how the respondent would be affected by a reform. Both high or moderately high trust and ‘likely’ correspond to the 6-10 responses on the 0-10 scale.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

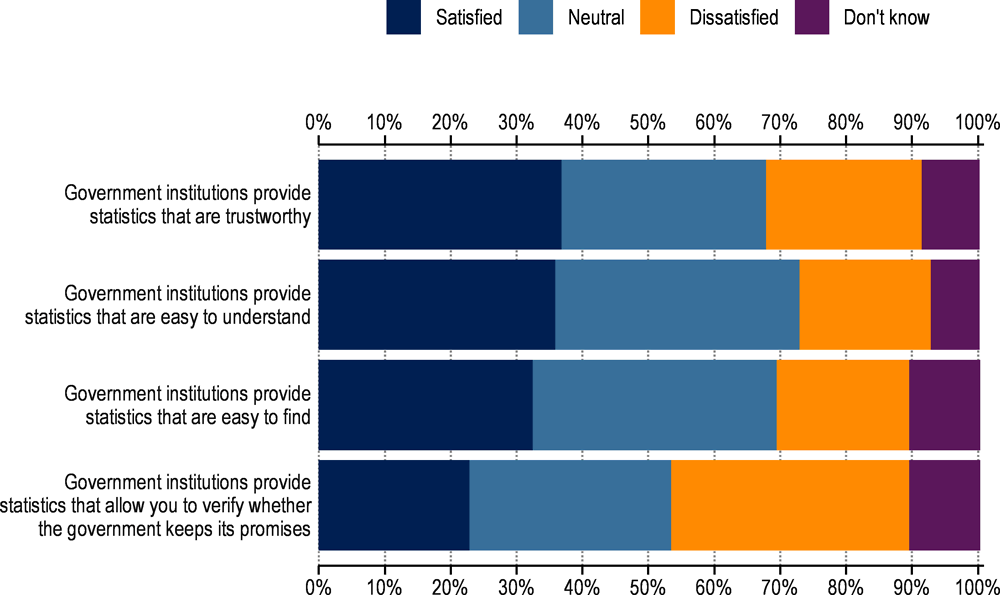

Statistics presented by government institutions are part of transparency efforts that can help citizens, businesses and organisations develop a common knowledge base and assess developments of the economic, social and government environment to make informed choices. Official statistics should provide relevant, impartial, and accessible data to help inform people, and allow them to assess government performance (UNSTATS, 2014[19]; UNSTATS, 2023[20]). However, the Trust Survey finds that only about a third believe statistics are often or always trustworthy, easy to find and understand (Figure 5.10). About one in five report these statistics are rarely or never easy to understand or find, and one in four find them rarely or never trustworthy. More than a third do not think these statistics help them verify government promises.

Figure 5.10. More than a third of people do not believe that government-provided statistics allow them to assess whether government keeps its promises

Share of population reporting different assessments of the characteristics of statistics provided by government institutions, OECD, 2023

Note: The figure presents the unweighted OECD averages for the distribution of responses to the four sub-questions of the question “In general, would you say that government institutions (such as ministries and the national statistical office) provide statistics that…trustworthy/easy to understand/easy to find/allow you to verify whether the government keeps its promises.” The ‘satisfied’ category includes respondents who stated that this was always or often the case, the ‘neutral’ those who stated this was sometimes the case and the ‘dissatisfied’ category those who said that it was rarely or never the case.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

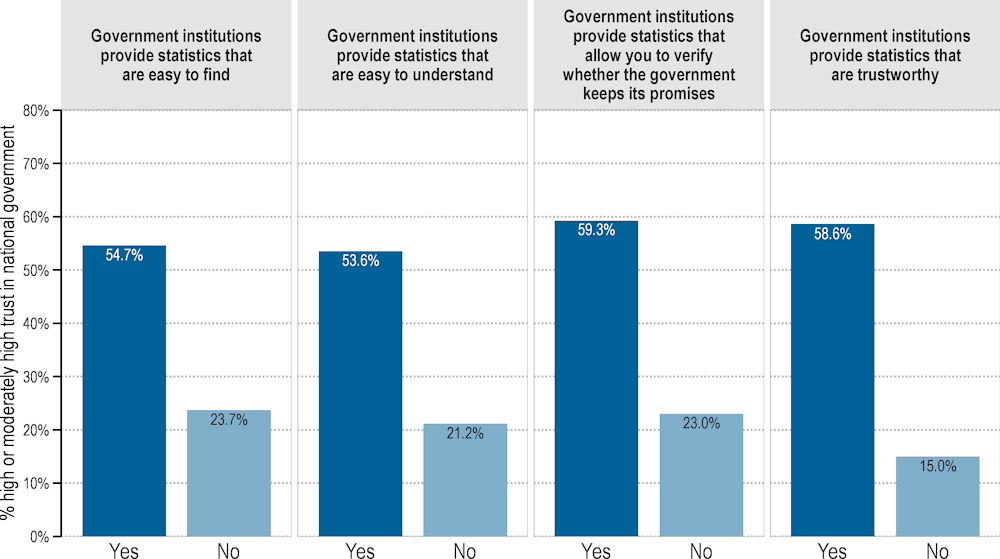

People's trust in government statistics is closely tied to their overall trust in the national government. Predictably, those who find government statistics to be often or always trustworthy are nearly four times more likely to have high or moderately high trust in the national government (59%) compared to those who rarely or never find them trustworthy (15%) (Figure 5.11). Similarly, people who believe that government statistics always or often allow them to verify government promises are more than twice as likely to trust the government compared to those who rarely or never believe they do.

Figure 5.11. Trust in government statistics is closely tied to trust in government

Share of population with different levels of trust in national government according to their perceptions of government statistics, OECD, 2023

Note: The figure illustrates the average percentage of the population expressing high or moderately high trust in the national government, based on their response to given questions displayed at the top of the chart. The share with high or moderately high trust corresponds to respondents who select an answer from 6 to 10 to the question: “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust the national government?”. Whether or not the respondent answered Yes or No to the selected questions is derived from the answers in 0-10 scale. The “Yes” option is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale, and “No” is the aggregation of responses from 1-4. The figure shows the unweighted OECD averages.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.Finally, in the current context, some individuals find neither the government nor the media to be credible. About one in six people (16%) have no or low trust in the media and think that government statistics are rarely or never trustworthy. This can result in them having overly cynical views. It may also make them more prone to conspiratorial beliefs (Jackob et al., 2019[21]).

5.4. Transparency about the evidence that underlies government decision making can build trust

Results from the 2023 OECD Trust Survey provide some guidance on public communication aspects which could be improved to better inform the population and increase the perceived trustworthiness of public institutions.

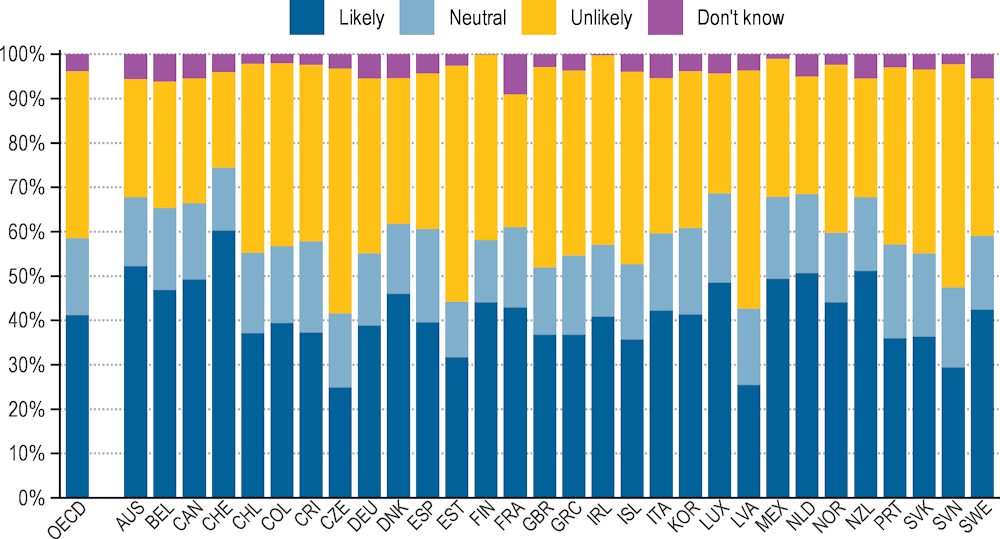

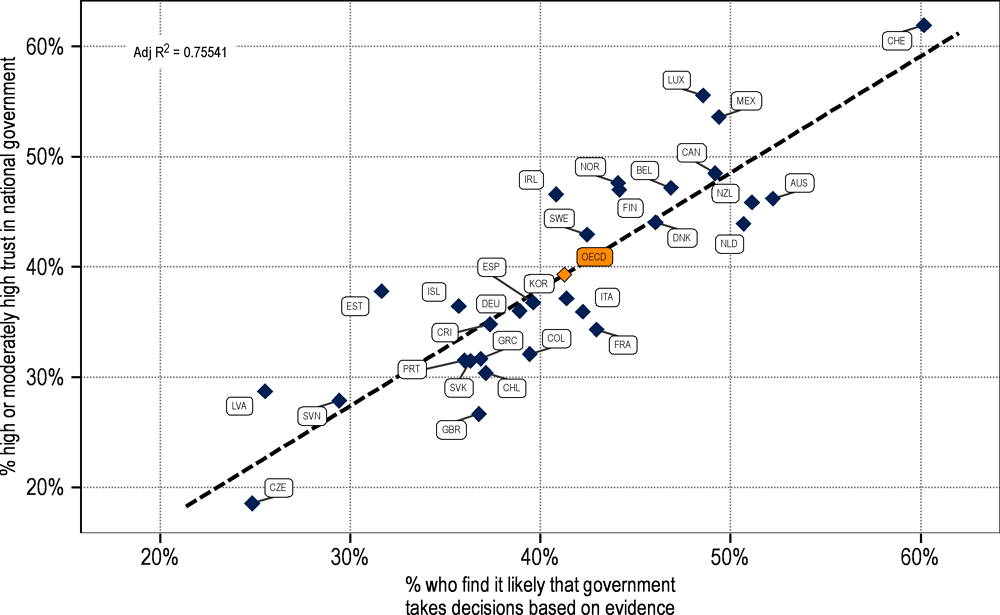

First, government decision-making is largely perceived as opaque, with limited information on the decision-making process. On average, only four out of ten people across OECD countries believe that the government utilises the best available evidence, research, and statistics when making decisions (Figure 5.12). Governments need to improve this perception, for example through establishing transparency standards in the process of assembling, analysing and applying evidence in the policy making process (Argyrous, 2012[22]). There is a high positive correlation between the share with high or moderately high trust in the national government and the share who find it likely that government decision making is evidence-informed (Figure 5.13). And while examining a diverse set of drivers of trust in national government, people’s confidence that the government uses evidence and facts in taking decisions has the highest positive association with trust in the national government (Chapter 1 and Annex A). Increased communication on the evidence used to reach a decision could therefore improve perceptions and trustworthiness of the government.

Figure 5.12. Four in ten find it likely that the government takes decisions based on the best available evidence, research and data

Share of population who find it likely or unlikely that government takes decisions based on evidence, 2023

Note: The figure shows the within-country distributions of responses to the question: “If the national government takes a decision, how likely do you think it is that it will draw on the best available evidence, research, and statistical data?” The “likely” proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale; “neutral” is equal to a response of 5; “unlikely” is the aggregation of responses from 1-4; and “don't know” was a separate answer choice. “OECD” presents the unweighted average of responses across countries.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

Figure 5.13. Confidence in the ability of government to make policies based on the best available evidence is closely related to trust in the national government

Share of population with high or moderately high trust in the national government (y-axis) by share of people that think it is likely government takes decisions based on best available evidence (x-axis), 2023

Note: The scatterplot presents the share of “high to moderately high trust” responses to the question “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust the national government?” on the y-axis. The y-axis presents the share of “likely” responses to the question “If the national government takes a decision, how likely do you think it is that it will draw on the best available evidence, research, and statistical data?”. Both high or moderately high trust and ‘likely’ correspond to the 6-10 responses on the 0-10 scale.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

Moreover, as noted in this chapter, many feel underserved by public communication. Most notably, 40% think it is unlikely the government would clearly explain how a policy reform would affect them, suggesting room for improvement in this area. Individuals who are financially vulnerable or have a lower education level tend to have significantly less confidence in the availability of public service information and the government's ability to clearly communicate the impacts of reform. Those concerned about their household's financial well-being are 11 to 12 percentage points more likely to not anticipate receiving clear information on both fronts.1 Similarly, even when all other factors are equal, those who have not completed upper secondary education are somewhat more likely (by four percentage points) to feel “underserved' with regard to information about services. More accessible and inclusive public communication would therefore be important to help ensure the population as a whole is well informed and therefore equipped to assess government performance and engage in political life. The 2021 OECD Report on Public Communication provides some guidance on how countries may achieve this (see Box 5.3).

Box 5.3. Five Key principles for Public Communication

The first OECD Report on Public Communication: The Global Context and the Way Forward examines the public communication structures, mandates and practices of centres of governments and ministries of health from 46 countries. The report outlines five key principles for public communication:

Empower the public communication function by setting appropriate mandates and developing strategies to guide the delivery of communication in the service of policy objectives and of the open government principles of transparency, integrity, accountability and stakeholder participation; and separating it, to the extent possible, from political communication.

Institutionalise and professionalise communications units to have sufficient capacity, including by embedding the necessary skills and specialisations that are leading the transformation of the field, and ensuring adequate human and financial resources.

Transition towards a more informed communication, built around measurable policy objectives and grounded in evidence, through the acquisition of insights in the behaviours, perceptions, and preferences of diverse publics, and the evaluation of its activities against impact metrics.

Seize the potential of digital tech but responsibly: Digital tools, data, and AI can facilitate greater engagement and inclusion if used ethically and with respect for privacy.

Fight mis and disinformation. Government must be equipped to pre-empt and debunk mis and disinformation through clear practice and guidelines.

Source: (OECD, 2021[23]).

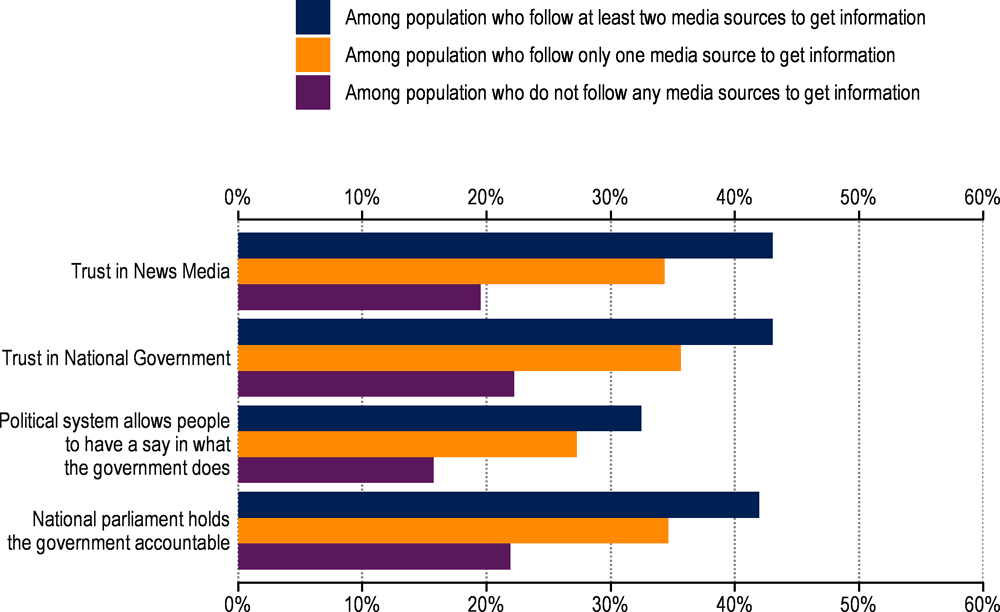

Moving beyond public communication to the wider information ecosystem, governments supporting media ecosystem that allows independent and plurality of information is essential. Indeed, evidence for the Trust Survey shows that people who obtain their information from multiple sources are substantially more trusting of the media, the national government, and have a better perception of how well the system lets people like them have a say (Figure 5.14). Of course, this data point does not enable us to ascertain the extent to which these media sources are politically aligned, or reflect similar world views, and as such are not a measure of media pluralism per se. However, these results do suggest that governments have an interest in ensuring the public is able and encouraged to access news in a plural and diverse media landscape.

Figure 5.14. People who gather their information from multiple sources tend to be more trusting

Share of population reporting high or moderately high level of trust in selected questions, OECD, 2023

Note: For the first two trust questions on the y-axis, respondents were asked: “On a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, in general how much do you trust: [OPTION]?”. The remaining two questions reflect respondents' preferences as expressed in their answers to the questions: “How much would you say the political system in [COUNTRY] allows people like you to have a say in what the government does?” and “How likely do you think it is that the national parliament would effectively hold the national government accountable for their policies and behaviour, for instance by questioning a minister or reviewing the budget?”. The x-axis shows the unweighted OECD averages for the population share who reported 'high or moderately high trust' or 'likely,' which is an aggregation of responses ranging from 6 to 10 on the scale. The coloured bars are categorized according to the number of media sources participants reported following to get information, using the following question: “On a typical day, from which of the following sources, if any, do you get information about politics and current affairs? [OPTION]”. They could select 'TV or radio,' 'Social media,' 'Newspapers, magazines, or online media,' or 'Don’t know'."

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

Additionally, media and information literacy education could help individuals recognise biased or misleading information. In 2018, 54% of 15-year-old students across the OECD reported that their school taught them how to identify subjective or biased information (OECD, n.d.[24]). However, existing evidence on the effectiveness of media literacy programs is not yet robust (OECD, 2024[3]).

In its report Facts not Fakes, the OECD has elaborated a framework that addresses this matter in depth, aiming at strengthening information integrity while protecting fundamental freedoms and addressing the global challenge of disinformation (Box 5.4).

Box 5.4. Facts not fakes: Tackling disinformation, strengthening information Integrity

The OECD report Facts not Fakes: Tackling Disinformation, Strengthening Information Integrity outlines a policy framework encompassing a range of policy options to counter disinformation and strengthen information integrity. The report emphasises that efforts to build information integrity should not only address sector or technology-specific concerns, but also respond to the challenges facing the media and information ecosystems at all.

Based on early learnings based on OECD Member Countries emerging initiative in this space, the suggested policy framework to help guide government actions focuses on:

Implementing policies to enhance the transparency, accountability, and plurality of information sources:

This includes promoting policies that support a diverse, plural, and independent media sector, with a needed emphasis on local journalism. It also comprises policies that may be utilised to increase the degree of accountability and transparency of online platforms, so that their market power and commercial interests do not contribute to disproportionately vehicle disinformation.

Fostering societal resilience to disinformation:

This involves empowering individuals to develop critical thinking skills, recognise and combat disinformation, as well as mobilising all sectors of society to develop comprehensive and evidence- based policies in support of information integrity.

Upgrading governance measures and public institutions to uphold the integrity of the information space:

This involves the development and implementation of, as appropriate, regulatory capacities, co-ordination mechanisms, strategic frameworks, and capacity building programmes that support a coherent vision and approach to strengthening information integrity within the public administration, while ensuring clear mandates and respect for fundamental freedoms. It also involves promoting peer-learning and international co-operation between democracies facing similar disinformation threats.

Source: (OECD, 2024[3]).

5.5. Conclusion for policy action to enhance trust

The information landscape significantly influences public perceptions and trust in public institutions. A trusted information ecosystem is essential for verifying government action and performance. However, disruptive trends like media market concentration, audience fragmentation, misinformation, and polarising speech can degrade journalism quality and information availability, impacting trust in media and public institutions.

In this context, decision-makers can take several steps to enhance trust.

A high positive correlation exists between those who trust the national government and those who perceive government decision-making as evidence informed. Governments would benefit from more actively communicating about the evidence, research, and statistics that inform their decisions to improve public perception of the decision-making process.

Confidence in the government's ability to explain the potential impact of reforms positively correlates with trust in the national government. However, 40% believe it's unlikely the government would clearly explain how a policy reform would affect them, indicating room for improvement. Public institutions need to enhance public communication strategies, ensuring they clearly explain how policy reforms affect the public to build confidence and trust.

Inclusive public communication should be a priority, specifically targeting financially vulnerable individuals or those with lower education levels, to ensure everyone has access to public service information and understands the impact reforms will have on them.

Governments have a responsibility and interest in promoting a healthy, diverse, and independent media environment. This allows public scrutiny and informed decision-making, fostering sceptical trust, which is a key element of a democracy.

The current information ecosystem has made it challenging for individuals to understand and assess the trustworthiness of news. Therefore, investing in evidence-informed approaches to media literacy is essential to foster societal resilience.

References

[16] Arguedas, A. et al. (2023), News for the powerful and privileged: how misrepresentation and underrepresentation of disadvantaged communities undermine their trust in news, University of Oxford, https://doi.org/10.60625/risj-jqny-t942.

[22] Argyrous, G. (2012), “Evidence Based Policy: Principles of Transparency and Accountability”, Australian Journal of Public Administration, Vol. 71/4, pp. 457-468, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8500.2012.00786.x.

[17] Blastland, M. and A. Dilnot (2022), Review of the impartiality of BBC coverage of taxation, public spending, government borrowing and debt, https://www.bbc.co.uk/aboutthebbc/documents/thematic-review-taxation-public-spending-govt-borrowing-debt.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2023).

[6] Castro, L. et al. (2022), “Navigating High-Choice European Political Information Environments: a Comparative Analysis of News User Profiles and Political Knowledge”, The International Journal of Press/Politics, Vol. 27/4, pp. 827-859, https://doi.org/10.1177/19401612211012572.

[5] Guriev, S. and D. Treisman (2019), “Informational Autocrats”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 33/4, pp. 100-127, https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.33.4.100.

[21] Jackob, N. et al. (2019), “Medienskepsis und Medienzynismus Funktionale und dysfunktionale Formen von Medienkritik. MEDIEN(SELBST)KRITIK”, https://doi.org/10.5771/0010-3497-2019-1-19.

[15] Kleis Nielsen, R. (2012), “Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Report: Ten Years that Shook the Media World Big Questions and Big Trends in International Media Developments”.

[1] Marcinkowski, F. and C. Starke (2018), “Trust in government: What’s news media got to do with it?”, Studies in Communication Sciences, Vol. 18/1, pp. 87-102, https://doi.org/10.24434/J.SCOMS.2018.01.006.

[12] Matasick, C., C. Alfonsi and A. Bellantoni (2020), “Governance responses to disinformation: How open government principles can inform policy options”, OECD Working Papers on Public Governance, No. 39, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d6237c85-en.

[13] Newman, N. et al. (2023), Digital News Report 2023, Reuters Institute & University of Oxford, https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/digital-news-report/2023.

[2] Norris, P. (2022), In Praise of Skepticism, Oxford University PressNew York, https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197530108.001.0001.

[8] Norris, P. (2000), A Virtuous Circle: Political Communications in Postindustrial Societies, Cambridge University Press, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511609343.

[3] OECD (2024), Facts not Fakes: Tackling Disinformation, Strengthening Information Integrity, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d909ff7a-en.

[4] OECD (2022), Building Trust and Reinforcing Democracy: Preparing the Ground for Government Action, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/76972a4a-en.

[9] OECD (2022), The Protection and Promotion of Civic Space: Strengthening Alignment with International Standards and Guidance, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d234e975-en.

[11] OECD (2021), Competition issues concerning news media and digital platforms, OECD Competition Committee Discussion Paper.

[18] OECD (2021), “OECD Report on Public Communication: The Global Context and the Way Forward - Report Highlights”.

[23] OECD (2021), OECD Report on Public Communication: The Global Context and the Way Forward, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/22f8031c-en.

[24] OECD (n.d.), PISA in Focus, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/22260919.

[14] Papathanassopoulos, S. et al. (2023), “The Media in Europe 1990–2020”, pp. 35-67, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-32216-7_3.

[10] Reporters without Borders (2022), World Press Freedom Index, https://rsf.org/en/index.

[7] Strömbäck, J., M. Djerf-Pierre and A. Shehata (2016), “A Question of Time? A Longitudinal Analysis of the Relationship between News Media Consumption and Political Trust”, The International Journal of Press/Politics, Vol. 21/1, pp. 88-110, https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161215613059.

[20] UNSTATS (2023), Classification of Statistical Activities, Version 2.0, https://unstats.un.org/unsd/classifications/CSA2 (accessed on 24 January 2024).

[19] UNSTATS (2014), Fundamental Principles of Official Statistics, https://unstats.un.org/unsd/dnss/hb/E-fundamental%20principles_A4-WEB.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2024).

Note

← 1. The results discussed in this paragraph are from an econometric analyses. They are obtained from logit regressions of whether the person thinks it is likely that information on administrative services are easily obtainable/that government will clearly explain how they will be affected by a reform on the person’s gender, age group, educational attainment and financial concerns and country fixed effects. The discussed effects of financial concerns and educational levels correspond to their average marginal effects.