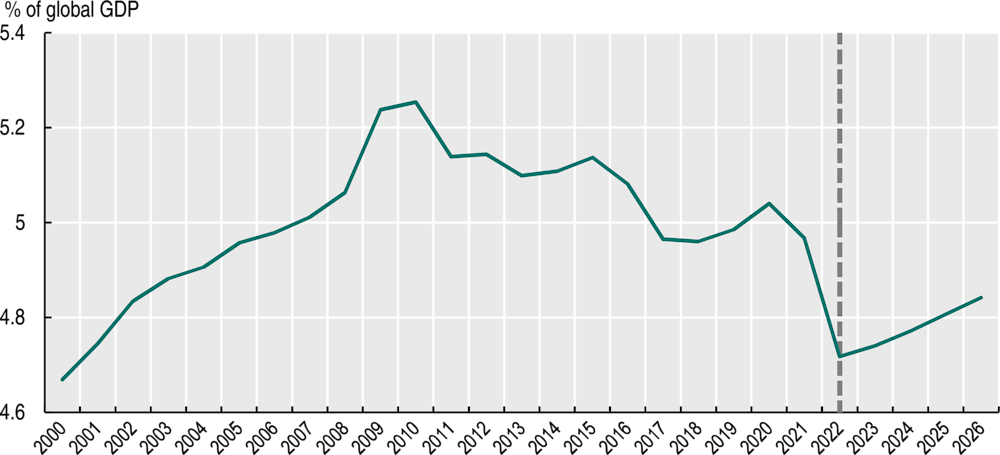

The COVID-19 pandemic is setting back Africa’s economic convergence with the world economy. African economic growth will reach 3.9% in 2022, one percentage point lower than the growth rate for the rest of the world, which stands at 4.9%. In 2022, Africa’s gross domestic product (GDP) as a share of the world GDP is expected to fall to 4.7%, the lowest level since 2002. This reverses the catching-up process that had been underway: between 2000 and 2010, Africa’s global economic weight steadily increased from 4.7% to 5.3% of the world’s output (Figure 1). Africa will not regain its pre-COVID share of the world GDP in a foreseeable future. COVID-19 has also reversed progress in reducing poverty in Africa, pushing at least an additional 29 million people into extreme poverty (Mahler et al., 2021).

Africa's Development Dynamics 2022

Overview

Developing regional value chains will support a sustainable recovery from COVID-19

Strengthening African countries’ productive systems is vital to their economic recovery

Figure 1. Africa’s output as a share of world gross domestic product (in purchasing power parity), 2000-26

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from IMF (2021a), World Economic Outlook Database, October 2021 projections, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2021/October.

The health and economic crises mutually reinforce each other. Vaccination programmes must accelerate: on 11 January 2022, only 9.5% of Africa’s population had been fully vaccinated, compared to 70.7% in high-income countries. The World Health Organization forecasts that the continent may not reach 70% vaccine coverage until August 2024 (WHO, 2021). In addition, weaker global demand, supply disruptions and necessary sanitary measures constrained economic activities. Our analysis of 127 African industrial clusters suggests that night light intensity within these clusters, a proxy for economic activities, decreased by up to 7.2% between March and August 2020.

The limited fiscal space available to African governments hinders the scope for fiscal stimulus. Our calculations suggest that total government expenditure in Africa reached 25.2% of GDP in 2020-21. For comparison, public expenditure reached 26.9% of GDP in 2009-10, when many African governments invested heavily in public infrastructure to combat the global financial crisis. The lower level of spending reflects the limited resources available to African governments during the pandemic. The latest data show that the average tax-to-GDP ratio in Africa increased 1.8 percentage points between 2010 and 2019. However, the rising costs of servicing debts offset two-thirds of this increase in revenues (OECD/AUC/ATAF, 2021).

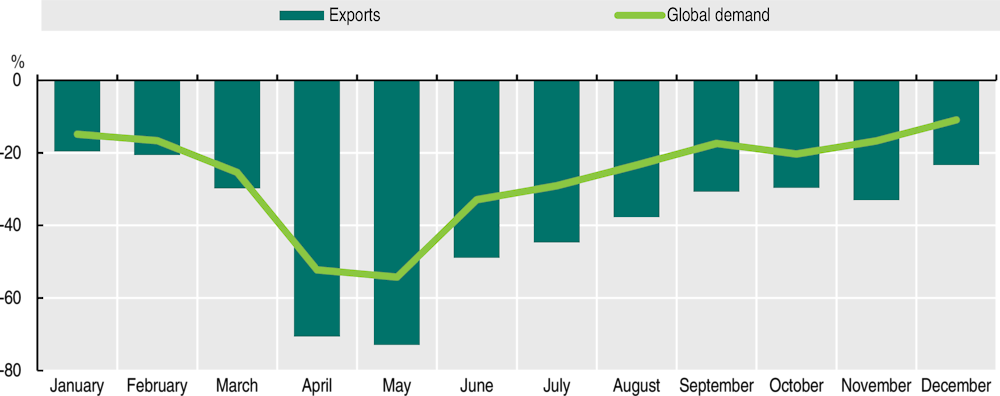

Production constraints limit African producers’ ability to benefit from the rebound in global demand. Strong global growth in 2022 will likely boost GDP by an additional 3.9 percentage points on average in ten African countries according to available data, compared to the trough in the second quarter of 2020.1 However, this is conditional on African producers’ ability to resume production and restore their competitiveness. Monthly bilateral trade data show that exports of African products lagged behind the recovery in global imports for those products between 2019 and 2020, suggesting important supply-side constraints (Figure 2). The continent’s share of imports to the European Union and United States markets decreased from 2.4% in 2019 to 2.0% in 2020, whereas Latin America and the Caribbean’s share slightly increased.

Figure 2. Africa’s export growth versus global demand growth, 2019-20

Note: Data on Africa’s exports include all goods exported by African countries to Europe and the United States, where reliable monthly data are available. Global demand for African products is proxied by total imports by Europe and the United States for goods that they also import from Africa. The figure shows a comparison of each month’s exports in 2020 with the same month’s exports in 2019.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on monthly trade data from UN (2021), UN COMTRADE (database), https://comtrade.un.org/.

Accelerating productive transformation is critical for creating quality jobs that reduce poverty and for strengthening Africa’s economic resilience (AUC/OECD, 2019). First, creating productive employment can help decrease poverty levels, as the limited fiscal space and the prevalent informal economy lessen the scope and efficiency of social protection systems. Second, building the capacity to manufacture pharmaceutical products and produce food locally can help African countries lower their vulnerability to future crises. African countries import 90% of their pharmaceutical products, which makes them vulnerable to disruptions in international supply chains. In 2020, nearly two-thirds of African countries were net importers of basic food whereas the number of hungry people has risen to 250.3 million, roughly one-fifth of the population in Africa (FAO/ECA/AUC, 2021).

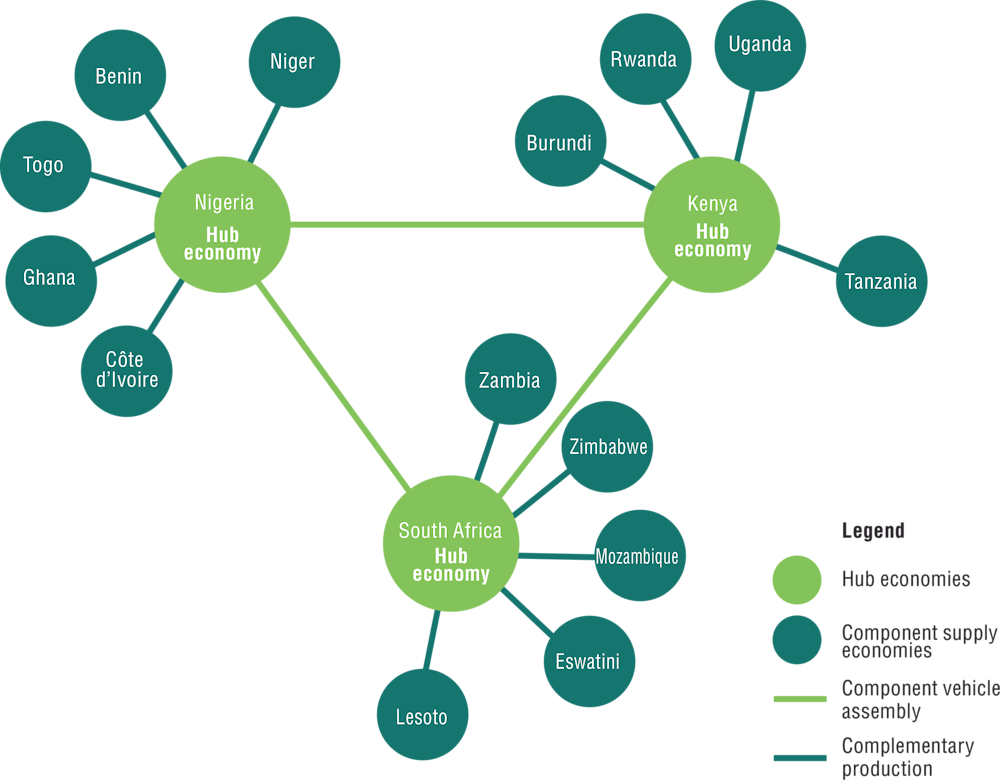

Rolling out the African Continental Free Trade Area can develop regional value chains and accelerate productive transformation

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) provides new opportunities for regional value chain integration. The AfCFTA is the most comprehensive continental agreement in Africa to date. It addresses important issues such as sanitary and phytosanitary standards, technical barriers to trade, intellectual property rights, and investment (World Bank, 2020a). It aims to increase intra-African trade by better connecting the continent’s 1.2 billion people and economies with a combined GDP of over USD 3 trillion. Rising domestic markets, fuelled by demographic growth, urbanisation and a new class of workers and consumers, offer new opportunities in many sectors, including the food, pharmaceutical and digital economy sectors. For scale-intensive industries such as the automotive industry, the continental market can facilitate a hub-and-spoke model of multiple vehicle assembly centres and component supplier economies (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Hub-and-spoke model for developing an automotive pact in sub-Saharan Africa

Source: Barnes, Erwin and Ismail (2019), “Realising the potential of the sub-Saharan African automotive market: The importance of establishing a sub-continental automotive pact”.

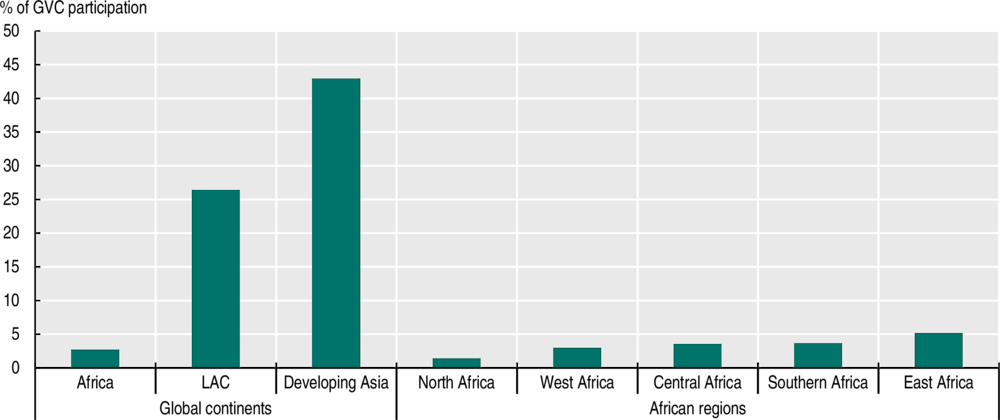

Regional value chains can complement Africa’s integration into global value chains and facilitate productive transformation. African producers remain largely marginal actors in international production, accounting for 1.7% of participation in global value chains in 2019 compared to 1.5% in 2000. Our calculations suggest that regional value chains account for only 2.7% of Africa’s global value chain participation, compared to 26.4% in Latin America and the Caribbean and 42.9% in developing Asia (Figure 4). Strengthening regional production networks can help African countries diversify their economic base and build their productive capacities. Processed and semi-processed goods accounted for 79% of intra-African exports in 2019, compared to 41% of Africa’s exports to other destinations. Furthermore, greater physical, social, cultural and institutional proximity can help African firms diversify and develop their productive capabilities when tapping the regional and continental markets. These new capabilities and inputs would enable firms to enter and thrive in more demanding markets.

Figure 4. The share of participation in regional value chains as a percentage of participation in global value chains, by world and African regions, 2019

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from Casella et al. (2019), UNCTAD-Eora Global Value Chain Database, https://worldmrio.com/unctadgvc/.

Currently, African countries largely participate in global value chains by exporting raw natural resources and agricultural commodities for further processing and production by other countries. Such forward participation in value chains makes up 5.9% of Africa’s GDP, a level similar to other developing regions. In contrast, backward participation – the use of foreign input for domestic processing – represents only 2.1% of Africa’s GDP, lower than in Latin America and the Caribbean (4.5%) and developing Asia (3.3%)

Strengthening regional production for local markets can improve backward participation in value chains and create productive jobs. Domestic processing at regional level to serve local demand can help producers specialise in downstream segments, such as food processing, marketing, transport and retail, by exploiting their proximity to final consumers. For example, in the agri-food value chains, downstream segments help create non-farm jobs in both rural and urban areas. These jobs can generate up to eight times more output per worker than farming (Tschirley et al., 2015).

Regional policies are essential for expanding regional production networks

Surpassing structural constraints and risks in regional production requires supportive regional policies

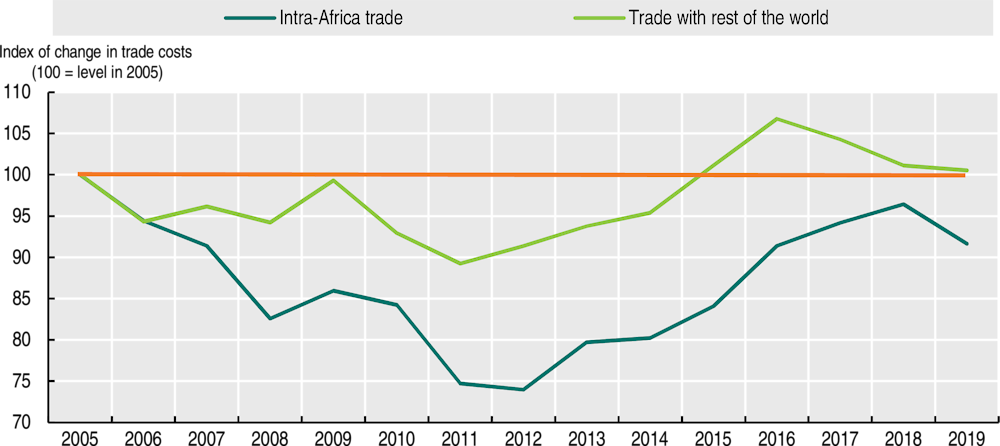

Rising intra-African trade costs impede regional production networks. As shown in Figure 5, the costs of trade within Africa have increased to 2007 levels, despite a considerable decline in intra-African tariffs. High trade costs are detrimental to production networks because they compound each time products cross international borders. High costs are due to poor transport infrastructure, non-tariff barriers and weak trade-related services such as logistics, trade finance and payments. By some estimates, logistics costs in Africa are up to four times higher than the world average (Plane, 2021). The COVID-19 crisis further increased trade costs due to disruptions to transport, restrictive trade policies and global economic uncertainty.

Figure 5. Evolution of Africa’s trade costs within Africa and with the rest of the world, 2005-19

Source: Authors’ calculations based on UN ESCAP/World Bank (2021), ESCAP-World Bank Trade Cost Database, www.unescap.org/resources/escap-world-bank-trade-cost-database.

Policy support is necessary for African firms to increase their competitiveness, create links with local economies and overcome barriers to investment. Most African firms lack the productivity, skills and organisational capabilities required for competitive exports. The few firms actively engaged in global value chains are often older and larger establishments, with little connection to the local economy. In addition, attracting investments in strategic value chains and retaining them requires strong formal institutions (e.g. political stability, macroeconomic stability, property rights and intellectual property rights) and accommodative informal institutions (e.g. business networks, partnerships and trusts).

International production networks also entail risks that require careful policy attention. Local workers and firms, especially vulnerable groups such as women and informal workers, risk being excluded from participating in international production and sharing the gains. Other concerns include precarious and dangerous employment conditions and child and forced labour (ILO/OECD/IOM/UNICEF, 2019).

African countries need to address environmental challenges alongside their development. This contrasts with developed world regions that were able to respond to environmental and developmental pressures sequentially. Despite limited industrial development, the death toll from outdoor air pollution in Africa outpaced that of the world by 30% and that of China by 50% over the 2010-19 period, according to a background paper drafted for this report (Roy, forthcoming).

Policy responses must be adapted to different value chains and local contexts. The governance structure of a value chain and the distribution of power between lead firms and local suppliers depend on the ability of actors to codify and share information, and on lead firms’ openness to linkages. African regions and countries differ significantly in terms of resource endowment, human capital, and the availability and competence of local suppliers. Policies must take into account these idiosyncratic factors that shape how firms develop, participate and upgrade in international production systems. The regional chapters of this report highlight the related opportunities and challenges, as well as the policies needed to develop five selected regional value chains (see Table 1 and Chapters 3-7).

Table 1. Policy recommendations to develop selected value chains in African regions

|

Region |

Value chain |

Policy recommendations |

|---|---|---|

|

Southern Africa |

Automotive |

• Improve the business environment and encourage investment from global lead firms • Actively support firms to maintain production and financial liquidity during the pandemic • Adopt accommodative trade policies by removing tariffs and other trade barriers |

|

Central Africa |

Wood |

• Improve the business environment through stable macroeconomics, harmonise business laws and liberalise import markets • Invest in transport and logistical infrastructure • Work with local communities and the private sector to develop processing capacity |

|

East Africa |

Agri-food |

• Review the Common External Tariff of the East African Community (EAC) and remove non-tariff barriers • Co-ordinate national industrial strategies and promote interactions between industrial clusters across countries in the region • Expand the One Network Area roaming initiative to other countries beyond the East African Economic Community (EAC) |

|

North Africa |

Energy |

• Improve the business environment and target industrial clusters to attract global lead firms • Establish training and research centres to build the relevant skills in the workforce • Facilitate intra-regional trade in raw materials and intermediate goods for the sector • Invest in transport links, and develop plans for intra-regional energy connections |

|

West Africa |

Agri-food |

• Improve access to finance, and provide technical and financial assistance to co-operatives • Facilitate digitalisation and climate-smart practices by smallholders and informal producers • Enhance implementation of Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) agreements on trade facilitation and quality standards • Target cross-border special economic zones to attract investment and increase competitiveness |

Previous efforts to integrate into value chains provide valuable lessons for policy making

Since the 1980s, African institutions have deployed multiple initiatives to foster regional and global value chains. Various continental strategies have sought to develop regional value chains as part of the broader strategy for industrialisation and structural transformation. Regional Economic Communities such as the Southern African Development Community (SADC), ECOWAS and EAC have adopted regional strategies for key value chains. However, most initiatives have fallen short of expected results so far, leading to concerns over a “crisis of implementation” (AU, 2017).

Past experiences highlight the importance of private-sector participation in developing regional value chains. Adopting a bottom-up process driven by the private sector helps sustain political momentum. It enables governments to identify policy priorities such as removing non-tariff barriers, providing infrastructure, developing skills and enhancing access to finance. Regional Economic Communities will continue to play an important role in this engagement. To ensure inclusiveness, governments need to help improve the institutional representation of small and medium-sized enterprises in trade associations, alongside large domestic firms, state-owned enterprises, or multinationals.

Better mobilising domestic resources is important to ensure policy implementation. A number of previous initiatives have lacked adequate resources. For instance, many countries have not respected their commitment to the Maputo Declaration that calls for reserving at least 10% of national budgets for agricultural development (AU, 2016). They often relied on external assistance, which hindered co-ordination and predictability. At the national level, tax administration reforms are necessary to mobilise domestic resources and combat illicit financial flows. Innovative financial instruments – including blended finance, public-private partnerships and climate bonds – can tap the global interests in sustainability-driven finance and unlock private-sector investment. Furthermore, the methodology for assessing regional infrastructure projects needs to account for their supranational benefits and use appropriate discount rates in calculating the projects’ present value (see Chapter 2).

Looking forward, policies need to address the regional, global and sectoral shifts in the investment landscape. The AfCFTA could increase the continent’s attractiveness for investors and generate new opportunities for intra-African investments. In parallel, Africa’s attractiveness to global investors may change with the introduction of a global minimum corporate tax, agreed in July 2021 and expected to take effect in 2023. Across many sectors, the COVID-19 shocks have had strong and heterogeneous ramifications. For example, annual greenfield foreign direct investment to Africa decreased from USD 78.4 billion in 2015-19 to USD 32.3 billion in 2020-21. All sectors attracted less investment with the exception of the information and communications technology and Internet industries, where greenfield foreign direct investment increased from USD 2.6 billion annually in 2015-19 to USD 6.2 billion in 2020-21.

COVID-19 has also accelerated digitalisation and increased the focus of firms and governments on sustainability. Across 13 African countries, more than 1 in 5 firms started using or expanded their use of digital technology in response to the COVID-19 shock (Davies et al., 2021). Similarly, since the onset of the pandemic, 48% of surveyed multinational enterprises operating in developing countries have increased their focus on the sustainability and decarbonisation of supply chains. Several African governments are setting up funds in their COVID-19 recovery plans for investment in the ICT sector, renewable energy and green value chains. These trends create new opportunities and challenges for policy makers in developing regional value chains (Table 2).

Table 2. Global trends: Opportunities and challenges for regional value chains

|

Trends |

Opportunities |

Challenges |

|---|---|---|

|

Changing investment landscape |

• Attract investment to tap local markets (e.g. agri-food processing and pharmaceutical) • Attract investment from near-shoring (especially in North Africa) • Encourage intra-African investment |

• Slower financial flows to emerging markets due to uncertain economic outlooks and higher interest rates in high-income economies • Higher risks of automation and reshoring |

|

Digital transformation |

• Adapt digital innovations to reduce the costs of international production and trade • Increase production efficiencies through digital adoption • Tap new niches in service segments • Integrate informal actors into value chains |

• Risk of exclusion among workers and producers due to barriers to digital adoption • Stronger demand for accommodative hard and soft digital infrastructure • Uneven competition on winner-take-all digital platforms • Risk of low-quality gig employment |

|

Global drive towards sustainability |

• Increase demand for high value-added activities • Increase pressure on multinational enterprises to meet environmental, social and governance (ESG) standards • Attract ESG finance • Invest in climate adaptation and the green sector as part of COVID-19 fiscal stimulus packages |

• Pressure for local producers to meet higher standards, especially among smallholders and informal actors • Higher testing and certification requirements |

Policy makers must work with the private sector to develop regional production networks

Public-private alliances in the digital economy can help reduce the costs of regional production and trade

Digital innovations, accelerated by the COVID-19 crisis, can increase the efficiency of trade-related logistics, customs and finance. For example, distributed ledger technology (blockchains) can make cross-border payments and trade finance more efficient by creating smart contracts. Other innovations can make it easier to implement rules of origin by generating, storing and sharing information. Digital innovations can allow for real-time and low-cost verification of a product’s provenance. Paperless processes and smart clearance technology can streamline customs procedures.

Innovative solutions can boost participation and upgrading in international production networks, especially by small and informal actors. They can allow large firms such as multinational enterprises and their smaller suppliers to build trust, communicate, co-ordinate and monitor across all stages of value chains. Smart contracts and reputation systems in digital platforms are new ways to integrate informal firms into the supply chains.

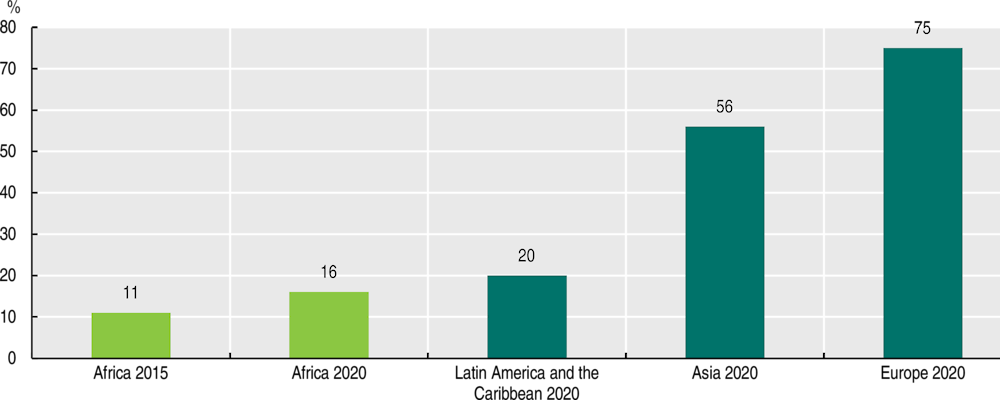

Public-private alliances are also key to developing regional Internet infrastructure and providing accommodative regulations for cross-border data flows. The flow of information between buyers and sellers underpins all decision making, production processes and value-addition in the context of Industry 4.0. Building the infrastructure to connect national digital markets can facilitate economies of scale, attract investment and increase competitiveness. For hard infrastructure, policy makers need to continue attracting private investment in intra-Africa Internet bandwidth. In 2020, only 16% of total bandwidth in Africa was intra-regional, compared to 20% in Latin America and the Caribbean, 56% in Asia and 75% in Europe (Figure 6). For soft infrastructure, countries can strengthen regulatory co-operation through the AfCFTA Protocol on E-commerce and other plurilateral agreements. Governments should also consider establishing data protection authorities and sharing best practices among them to better enforce data protection laws in conjunction with the private sector.

Figure 6. Intra-regional Internet bandwidth, by continent

Note: Data reflect traffic and bandwidth utilisation over Internet bandwidth connected across international borders. Data as of mid-year.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on data from Telegeography (2021), Telegeography Database, www2.telegeography.com/telegeography-report-and-database.

National industrial policies need to adapt to the new environment provided by the AfCFTA

Tailoring skills policies to technical needs and emerging trends is crucial for attracting investment and increasing linkages with lead firms. Talent and skills rank among the top four determinants driving foreign direct investment to developing economies (World Bank, 2020b). Upskilling and re-skilling will be crucial to meet sector-specific needs and new requirements for Africa’s digital and green transformation. Policy makers in the AfCFTA may consider the following courses of action:

-

First, enhancing policy dialogue between policy makers, the private sector and training institutions will help to identify skills needs and design appropriate training programmes at the sectoral level. National governments and the private sector can also pool resources into regional centres of excellence, such as the African Masters in Machine Intelligence, to train African researchers and engineers.

-

Second, supporting intra-regional skills mobility can help alleviate skill shortages in some sectors. Regional initiatives from the EAC or SADC, for example, provide lessons for removing restrictions on intra-Africa mobility of skilled labour.

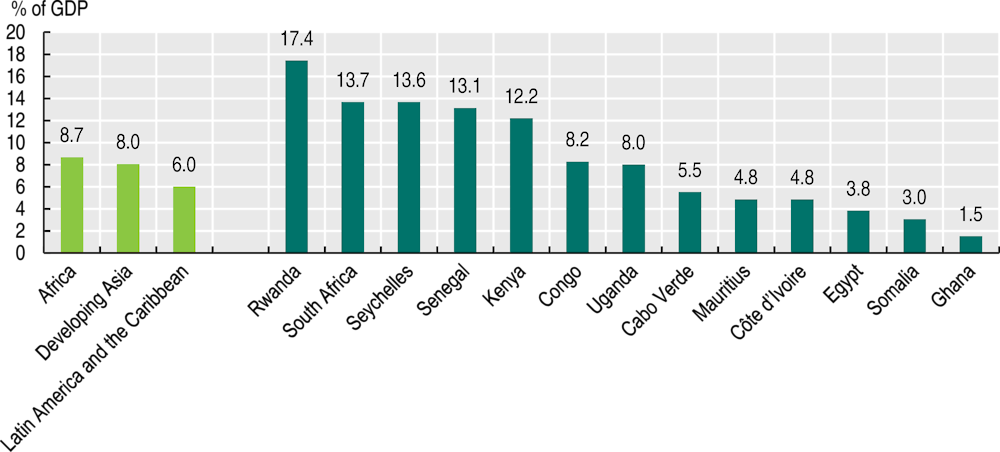

Modernising and broadening the eligibility criteria of public procurement programmes can create demand for linkages among producers in the AfCFTA. African governments can use their relatively sizable public procurement efforts – purchasing goods and services – to attract local producers to strategic value chains. Public procurement accounted on average for 8.7% of GDP in Africa compared to 8% in developing Asia and 6% in Latin America and the Caribbean over the 2015-19 period (Figure 7). By investing in e-procurement systems, governments can improve bidding transparency and ensure timely payments. They can also expand eligibility criteria for preferential treatment beyond narrowly defined domestic producers to cover regional actors in the AfCFTA. Harmonising product standards and mutual recognition agreements can reduce the costs for African suppliers to participate in regional markets.

Figure 7. Government procurement spending as a percentage of gross domestic product, 2015-19 average

Note: This figure draws on the OECD methodology to derive general government procurement spending. Africa, developing Asia and Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) averages are weighted. Asia includes 11 countries: Afghanistan, Indonesia, Jordan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Myanmar, Nepal, Philippines, Thailand, Timor-Leste and Uzbekistan. LAC includes 9 countries: Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Honduras, Mexico, Paraguay and Peru.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the OECD methodology and data from IMF (2021b), Government Finance Statistics (database), https://data.imf.org/?sk=a0867067-d23c-4ebc-ad23-d3b015045405.

Harmonising domestic environments through the Pan-Africa Investment Framework requires a strong monitoring structure. So far, African governments have agreed to 854 bilateral investment treaties (512 are in force) of which 169 are intra-African (44 in force). Harmonising domestic investment legislation could help reconcile the continent’s fragmented investment environment and boost intra-African investments by 14% compared to the 2018 level. Accelerating the national adoption of regionally agreed protocol such as the Pan-African Investment Code should be a priority. Experiences in Africa, such as the SADC Investment Policy Framework, suggest that strong monitoring and evaluation structures, based on a commonly agreed set of indicators, help effective implementation.

Africa’s existing networks of industrial clusters provide a critical entry point for developing infrastructure and promoting investment. Investment in connective infrastructure may target regional corridors that connect clusters across countries, such as the LAPSSET Corridor (Kenya-Ethiopia), the Central Corridor (Dar es Salaam-DR Congo), the Maputo Development Corridor (Mozambique-South Africa) and the Walvis Bay Corridor (five SADC countries). In addition, investment promotion agencies (IPAs) can help facilitate investment from lead firms into key segments of a value chain. Important considerations for establishing IPAs include: (i) ensure high-level government support; (ii) establish clear targets for investment promotion; (iii) consult local public and private stakeholders to ensure strategic alignment; (iv) facilitate collaboration with other investment institutions and funds; and (v) provide sufficient and sustained financial resources (OECD, 2021).

References

AU (2017), Report on the Proposed Recommendations for the Institutional Reform of the African Union (Kagame report), African Union, Addis Ababa, https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/33273-doc-report-_institutional_reform_of_the_au.pdf (accessed 1 November 2021).

AU (2016), CAADP Country Implementation under the Malabo Declaration, African Union, Addis Ababa, https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/31251-doc-the_country_caadp_implementation_guide_-_version_d_05_apr.pdf (accessed 1 November 2021).

AUC/OECD (2019), Africa’s Development Dynamics 2019: Achieving Productive Transformation, OECD Publishing, Paris/African Union Commission, Addis Ababa, https://doi.org/10.1787/c1cd7de0-en.

Barnes, J., A. Erwin, and F. Ismail (2019), “Realising the potential of the sub-Saharan African automotive market: The importance of establishing a sub-continental automotive pact”, in A Report for Trade & Industrial Policy Strategies (TIPS) and the African Association of Automotive Manufacturers (AAAM).

Casella, B. et al. (2019), UNCTAD-Eora Global Value Chain Database, https://worldmrio.com/unctadgvc/ (accessed 1 December 2021).

Davies, E. et al. (2021), “Firms through the Covid-19 pandemic: Evidence from sub-Saharan Africa” in Shaping Africa’s Post-Covid Recovery, VoxEU, CEPR Press, London, pp. 19-30, https://voxeu.org/content/shaping-africa-s-post-covid-recovery.

FAO/ECA/AUC (2021), Africa Regional Overview of Food Security and Nutrition 2020: Transforming Food Systems for Affordable Healthy Diets, United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, Accra, https://doi.org/10.4060/cb4831en.

ILO/OECD/IOM/UNICEF (2019), Ending Child Labour, Forced Labour and Human Trafficking in Global Supply Chains, International Labour Organization, OECD, International Organization for Migration and United Nations Children’s Fund, Geneva, www.oecd.org/corruption/ending-child-labour-forced-labour-and-human-trafficking-in-global-supply-chains.htm.

IMF (2021a), World Economic Outlook Database, October 2021 projections, www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2021/October (accessed 1 November 2011).

IMF (2021b), Government Finance Statistics Database, April 2021, https://data.imf.org/?sk=a0867067-d23c-4ebc-ad23-d3b015045405 (accessed 1 November 2021).

Mahler, D. G. et al. (2021), “Updated estimates of the impact of COVID-19 on global poverty: Turning the corner on the pandemic in 2021?”, World Bank blog, https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/updated-estimates-impact-covid-19-global-poverty-turning-corner-pandemic-2021.

OECD (2021), “Improving public finance, boosting infrastructure: Three priority actions for Africa’s sustainable development after COVID-19”, OECD, Paris, www.oecd.org/dev/africa/Financing-Summit-for-Africa_Background-paper.pdf.

OECD/AUC/ATAF (2021), Revenue Statistics in Africa 2021, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c511aa1e-en-fr.

Plane, P. (2021), “What factors drive transport and logistics costs in Africa?”, Journal of African Economies, Vol. 30/4, pp. 370-388, Oxford University Press, https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jae/ejaa019.

Roy, R. (forthcoming), “The case for intra-continental trade: The re-orientation of Africa’s trade and the twin challenges of development and environment”, background paper for Africa’s Development Dynamics 2022.

Telegeography (2021), Telegeography Database, www2.telegeography.com/telegeography-report-and-database (accessed 21 September 2021).

Tschirley, D. et al. (2015), “Africa’s unfolding diet transformation: Implications for agrifood system employment”, Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies, Vol. 5/2, pp. 102-136, https://doi.org/10.1108/JADEE-01-2015-0003.

UN (2021), “Monthly trade data” in UN Comtrade (database), United Nations, New York https://comtrade.un.org/ (accessed 1 November 2021).

UN ESCAP/World Bank (2021), ESCAP-World Bank Trade Cost Database, United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, Bangkok, www.unescap.org/resources/escap-world-bank-trade-cost-database (accessed 4 October 2021).

WHO (2021), “Africa clocks fastest surge in COVID-19 cases this year, but deaths remain low”, World Health Organization, www.afro.who.int/news/africa-clocks-fastest-surge-covid-19-cases-year-deaths-remain-low.

World Bank (2020a), The African Continental Free Trade Area: Economic and Distributional Effects, World Bank, Washington, DC, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/34139/9781464815591.pdf.

World Bank (2020b), Global Investment Competitiveness Report 2019/2020: Rebuilding Investor Confidence in Times of Uncertainty, World Bank, Washington, DC, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/33808.

Note

← 1. We conducted a global vector autoregressive modelling exercise using data from 10 Africa countries where quarterly data are available for at least 20 years: Botswana, Cameroon, Egypt, Ghana, Kenya, Mauritius, Morocco, Namibia, South Africa and Tunisia. See Chapter 1 and Annex 1.A1 for more information.