Belgium was able to build on pre-existing institutional structures to protect lives and livelihoods during the COVID-19 crisis. Like many other OECD countries, Belgium made heavy use of its job retention scheme, rapidly expanding access to temporary unemployment benefits. The labour market shock was consequently absorbed mostly by working-time reductions, while unemployment increased only slightly. A second pillar of Belgium’s policy response was the extension of the bridging right scheme, a unique income support programme for self-employed workers. Lower-tier income support programmes, including unemployment and social assistance benefits, in contrast, were only slightly extended. Income inequality and poverty declined in the initial phase of the crisis due to government support, and the labour market swiftly recovered. Coverage gaps likely existed for workers on short contracts, including many young people, who qualified for neither job retention support nor unemployment benefits, and in many cases do not appear to have received minimum-income support.

Evaluation of Belgium’s COVID-19 Responses

7. Belgium’s labour market and social policy response to the COVID-19 crisis

Abstract

Key findings

The outbreak of COVID-19 caused profound disruption to the lives and livelihoods of people in Belgium and across OECD countries, and unprecedented restrictions of social and economic activity were needed to contain the pandemic. Belgium, like many other OECD countries notably in Europe, heavily relied on job retention support (the temporary unemployment scheme) as the central pillar of its strategy to protect jobs and incomes. The labour market shock was consequently absorbed mostly by working‑time reductions. In the initial phase of the crisis, hours worked declined by 18%, close to the EU-27 average. Three-in-four unworked hours were accounted for by workers who reduced their working time to zero while staying employed. Meanwhile, a greater share of workers worked from home than in most EU countries. The unemployment rate increased only slightly, by 1.5 percentage points in 2020, with job losses borne disproportionately by vulnerable groups, particularly workers on temporary contracts. Young people experienced larger hours reductions and greater job losses than prime-aged workers; women reduced their hours somewhat less than men, but a greater share of these reductions came from job losses.

The labour market recovery was swift. As the public health situation improved and economic activity resumed, hours worked quickly expanded again. By the first quarter of 2022, Belgium’s employment rate surpassed its pre-crisis level, by about 1.4 percentage points, while inactivity had dropped by 1.6 percentage points relative to the fourth quarter of 2019. Again, these trends are much in line with many of Belgium’s OECD peers, including France, Germany, and the Netherlands.

A strength of Belgium’s policy response to the COVID-19 crisis was that Belgium – more than many other OECD countries – was able to build on pre-existing institutional structures. Substantial extensions to the temporary unemployment scheme made job retention support the first line of defence against pandemic-related income losses. The scheme achieved broad coverage, with about 30% of dependent workers receiving Job Retention Scheme (JRS) support in spring 2020. Benefit generosity was slightly lower than the OECD average, but many workers additionally received collectively agreed sectoral bonuses. One shortcoming was that workers on very short contracts remained excluded, even though they account for a comparatively large share of total employment in Belgium, and this group was particularly affected by job losses during the crisis. Belgium was slower than other countries to phase out job retention support which may have harmed labour utilisation during the recovery, particularly in the context of emerging labour shortages.

Belgium also extended its bridging right scheme, a unique income support programme for self‑employed workers experiencing external shocks, by broadening eligibility, increasing maximum durations, and permitting simultaneous receipt of other social benefits. In April 2020, more than half of primarily self‑employed workers received bridging right payments. Replacement rates of these flat-rate payments were relatively high for those on low incomes, particularly after payments were doubled for those affected by mandated closures during the second lockdown. While higher replacement rates for low‑income workers are justifiable in a crisis, particularly when benefits are funded out of the general budget, flat-rate payments do lead to loss in precision of targeting and further moral hazard in the long term.

Out-of-work income support played a lesser role in protecting the livelihoods of workers and households affected by the crisis. Unemployment Benefits (UB) offer comparatively high replacement rates, and Belgium temporarily froze payment amounts, which in non-crisis times decline over the benefit spell, to account for the difficulty of looking for work during the pandemic. Unlike many other OECD countries, however, Belgium did not cut its relatively long minimum‑contribution periods. Rates of unemployment benefit receipt remained flat over the crisis.

Since Unemployment Benefits can be received for an (in principle) unlimited duration in Belgium, Social Assistance plays a more minor role than in peer OECD countries. During the COVID‑19 crisis, receipt of the Social Assistance benefit only increased slightly. This reflects the effectiveness of pandemic extensions to the temporary unemployment and bridging right schemes. However, given the increase in the unemployment rate by 1.5 percentage points, and the fact that UB receipt also remained flat, this only modest rise in Social Assistance receipt implies that many of those who lost their jobs may not have received income support. Belgium did top-up Social Assistance benefit amounts during the crisis, but the impact on household incomes was limited, whereas other countries significantly increased the generosity of means-tested benefits.

The crisis, and the extraordinary measures taken by Belgium to protect jobs and incomes, led to a major rise in public social expenditures, 8% in 2020, comparable to what is observed in peer OECD countries. As a result, Belgium, as several other EU countries, managed to prevent major income losses in the initial phase of the crisis. Low-income households even recorded real income gains in 2020 thanks to government support, and income inequality and poverty declined. Given the lack of more recent income data, the verdict is still out on the medium-term impact of the crisis on incomes.

7.1. Introduction

In the early months of 2020, the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic caused profound disruption to the lives and livelihoods of people across the OECD, and unprecedented restrictions on social and economic activity were required to contain the pandemic. Following a meeting by the National Security Council on 12 March 2020, Belgium took far-reaching measures to limit the spread of the virus, announcing the closure of schools, restaurants and cafés, and the cancellation of all public gatherings for recreational or sportive events. A few days later, Belgium also ordered the closure of non-essential shops and the prohibition of non‑essential commuting and travel. As employees fell ill, reduced their working hours or lost their earnings, job retention support, unemployment benefits and replacement income for the self‑employed kicked in to protect jobs and incomes. Existing schemes were extended and reinforced to broaden coverage and raise generosity.

This chapter examines the main labour market and social impacts of the COVID-19 crisis in Belgium and presents an assessment of the measures taken by Belgian authorities to support the jobs and livelihoods of those affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. It begins with an analysis of the consequences of the pandemic on Belgian’s labour market, examining the effects on hours worked and employment. The chapter then turns to the main policies adopted to cushion the impact of the crisis: protecting jobs through temporary unemployment, Belgium’s job retention scheme; replacing the incomes of self-employed workers through the bridging right scheme; and increasing the payments of unemployment benefits and minimum‑income support. The chapter ends by providing an initial assessment of the impact of the crisis and the policy measures taken on household incomes, particularly for lower-income households.

The chapter shows that in responding to the labour market crisis, Belgium – more than many other OECD countries – was able to build on pre-existing institutional structures, notably the temporary unemployment and bridging right schemes. By quickly adapting and expanding those schemes, Belgium managed to keep unemployment at bay, prevented major income losses for many of the most affected households, and paved the way for a rapid recovery. However, some groups of workers – notably temporary workers on short on very contracts – likely faced difficulties in accessing these schemes. Downstream layers of the welfare state architecture, most importantly unemployment and social assistance benefits, were not extended to the same extent, which may have resulted in inadequate income support for some groups. Challenges arose also in ensuring an adequate provision of social support for the most vulnerable across all parts of the country, particularly during the initial phase of the crisis.

7.2. The labour market impact of the COVID-19 crisis

The labour market adjustment to the unprecedented shock of the COVID-19 pandemic was shaped by policy (OECD, 2021[1]). Belgium, like other European countries, limited job losses with the use of Job Retention Schemes (JRS), meaning that the adjustment was, especially in the beginning of the pandemic, mainly through hours worked and not joblessness. Other countries, such as the United States or Canada, reinforced their unemployment insurance programmes in response to mandated business closures, which was effective in protecting incomes, but led to job losses early on in the crisis. In Belgium, as in many OECD countries, the reliance on a JRS that preserved the employer-employee match and enabled firms to shore up production quickly as health-measures allowed, the unexpectedly quick adaptation of workplaces to the virus (including through the widespread use of teleworking), as well as strong government support to households and businesses, have led to a strong and relatively quick recovery of labour markets.

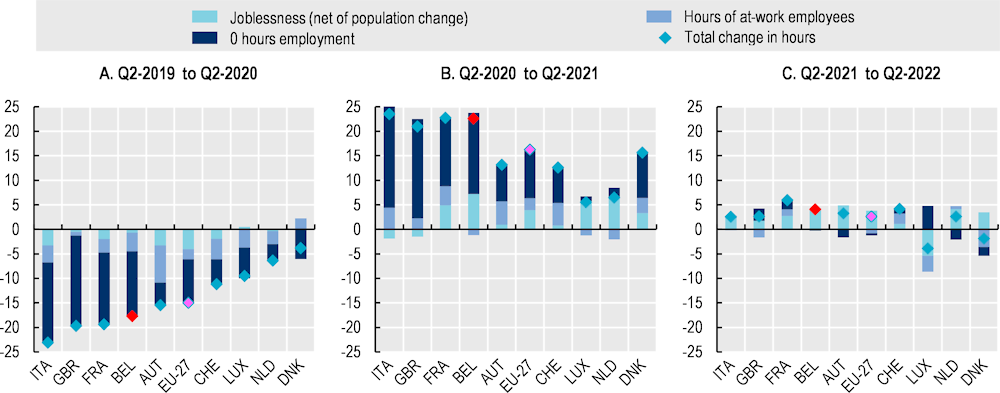

7.2.1. The initial labour market shock was mostly absorbed by reduced hours

Belgium’s labour market absorbed the heavy blow dealt by the COVID-19 pandemic not primarily via job losses but through major reductions in hours worked of those who remained in employment. At the beginning of the crisis, during the initial COVID-19 lockdown, hours worked in Belgium fell by 18%, close to the EU-27 average (Figure 7.1, Panel A). About three in four unworked hours were accounted for by workers who, though employed, reduced their working time to zero; only about 4% of unworked hours were due to job losses, with the remainder made up of working time reductions. Other European countries that operated JRS in this early phase of the pandemic – including Italy, the United Kingdom, France, Austria, Switzerland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Denmark – show similar patterns; total hours reductions were significantly less pronounced in Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Denmark than in Belgium. In contrast, in countries that did not operate a JRS, including the United States and Canada, the adjustment happened mainly via job losses (i.e. at the extensive, not just the intensive margin), leading to large drops in the employment rate.

Figure 7.1. Fall in hours worked in Belgium was largely attributable to working time reductions

Decomposition of the change in working hours, Q2-2019 to Q2-2022

A distinctive feature of the COVID-19 crisis was its highly sectoral nature. About six in ten hospitality workers in Belgium either had their hours cut or lost their jobs in the second quarter of 2020. Construction, retail and transport, as well as storage were also strongly affected; workers in other sectors, such as information and communication, health, financial services, and public administration were much less affected (Lens, Marx and Mussche, 2020[2]). Across the EU-27 on average, hours worked in the hospitality sector dropped by more than half compared to the previous year, and by 42% in the arts and entertainment sector. While also in these sectors, JRS meant that unworked hours were mostly absorbed by working time reductions, the hospitality industry as well as arts and entertainment saw job destruction increase in the second half of 2020 (OECD, 2021[1]).

In Belgium, the sectoral gradient especially affected workers with non-Belgian nationality, who were up to twice as likely to receive JRS payments than their Belgian counterparts, largely because they are overrepresented in non-teleworkable sectors such as hospitality, retail, and construction. These sectors also experienced the longest restrictions, leading to prolonged receipt durations (Federal Public Service Employment, Labour and Social Dialogue and UNIA, 2022[3]).

The swift move towards teleworking in occupations where this was possible was another important margin for adjustment. According to Eurostat data, the share of employed persons working “sometimes” or “usually” from home in Belgium was already above the EU average before the crisis, at around 25% in 2019; over the course of the crisis, it jumped by another 15 percentage points to nearly 40% in 2021. This ranks Belgium among the top seven countries in the EU-27, though the share of those working at home is higher still in the Netherlands, Luxembourg and some of the Nordic countries (Eurostat, 2023[4]). This is consistent with the finding that prior to the crisis Belgium had one of the highest shares of jobs judged “teleworkable” across the European Union (Sostero et al., 2020[5]).

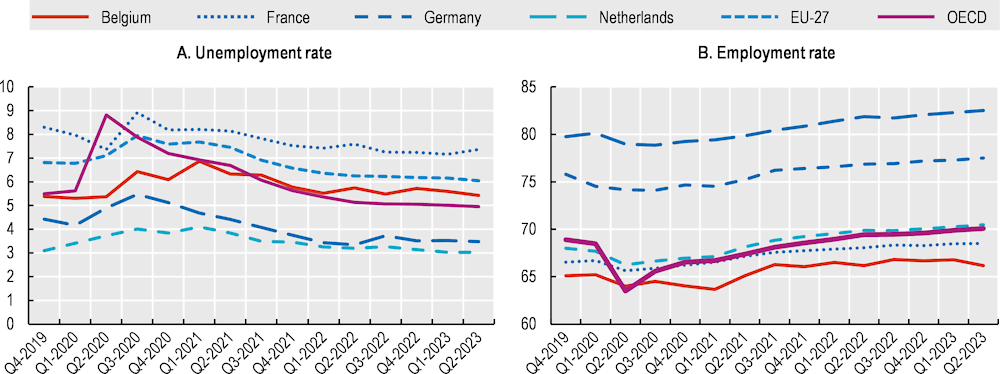

7.2.2. … but joblessness did increase, particularly among vulnerable groups

Despite large adjustments in hours worked, Belgium – like other countries that operated comprehensive JRS – experienced an increase in joblessness, i.e. unemployment or inactivity. In Belgium, the unemployment rate increased by about 1.5 percentage points in 2020 (Figure 7.2, Panel A); across the European Union, where most countries also operated strong JRS, the increase was a little more subdued, at 1 percentage point until the highest point in mid-2020. Meanwhile, unemployment rose by almost 3 percentage points across the OECD on average in the beginning of the crisis, driven partly by countries where temporary layoffs inflated unemployment figures (including the United States and Canada). Those increases likely understate the true extent of underemployment, as many unemployed workers gave up actively looking for a job during the halted or subdued economic activity of the lockdowns, and thus became labour market inactive instead of unemployed in labour force surveys (OECD, 2021[1]). The employment rate in Belgium dropped by just over 1 percentage point in the initial phase of the crisis, plus another around 0.5 percentage points up to the first quarter of 2021 (Figure 7.2, Panel B).

While job losses were low considering the extent of economic contraction, the job losses that did occur were concentrated among vulnerable groups, particularly those in non-standard forms of work. Throughout 2020, temporary employment in Belgium decreased by over 10%, while dependent employment dropped by only 2% (Figure 7.3). However, this pattern was less pronounced than across European OECD countries on average, where temporary workers were about ten times more likely to lose their jobs than their colleagues on permanent contracts (OECD, 2021[1]). While temporary workers often bear the brunt of adjustment in economic downturns, the strong reliance on JRS in Belgium and other European countries during the COVID-19 pandemic has intensified this effect: JRS are often less accessible for temporary workers, either statutorily or practically, as contracts cannot or may not be extended while on layoff (see Section 7.3.1).

Figure 7.2. Both the unemployment and the employment rate in Belgium have returned relatively quickly to their pre-crisis levels

Seasonally adjusted quarterly unemployment and employment rates (ages 15-64)

Note: OECD and EU-27 are weighted averages.

Source: OECD Short-term Labour Market Statistics (2023).

Figure 7.3. Job losses have been concentrated among temporary workers

Change in employment compared to the previous year

As a result, job losses particularly affected young people and other labour market entrants such as migrant workers who are more likely to work on temporary contracts. In Belgium, hours losses among under‑25‑year-olds were 10 percentage points higher than for prime-aged workers, at -27% vs. -17% in the initial phase of the crisis. Around one in five lost hours worked by young people resulted from job loss, compared to one in fifty for prime-aged and older workers. A similar pattern applies across the EU-27 on average: hours worked by under-25-year-olds dropped by more than a quarter at the beginning of the pandemic, compared to one-sixth for prime-aged and older workers. About one in three hours worked by young people were due to job loss across the OECD on average, compared to one in five for prime-aged and older workers. Besides contract type, these trends also reflect the sectoral concentration of young workers in hospitality and other in-person services that were most affected during initial lockdowns. While sectoral and occupational concentration of young people (and migrants) also played a role in job losses in the pandemic in Belgium, the most important factors making these groups more vulnerable have been temporary work and low seniority with the company (Lens, Marx and Mussche, 2020[2]).

At the onset of the COVID-19 crisis, its strong sectoral gradient caused concern that women would be more heavily affected, but this concern has largely not been borne out. Women are overrepresented in in-person service roles, particularly in hospitality and retail, which have been very heavily affected, but also among “essential” or “key” workers in health and social services, as well as among “teleworkable” jobs, e.g. in education (OECD, 2021[1]). As a consequence, total hour losses in the initial phase of the crisis were lower for women than for men in Belgium, at -19% vs. -16%. The opposite holds true across EU-27 countries on average, though only by a small margin. However, women were more likely to be laid off than to reduce their hours: in Belgium, in the second quarter of 2020 job loss accounted for only around 0.5% of the hours decline among men, but about 9% of the decline among women. This is a much more pronounced pattern than across the EU-27 on average, where job loss accounts for about one in three unworked hours by women, compared to one in four by men. Compared to men, women’s employment, however, also recovered more quickly, and strongly. Compared to the second quarter of 2019, hours worked by men increased by about 3%, while hours worked by women increased by about 7%. Much of this increase was due to job creation, especially out of inactivity (Salvatori, 2022[6]).

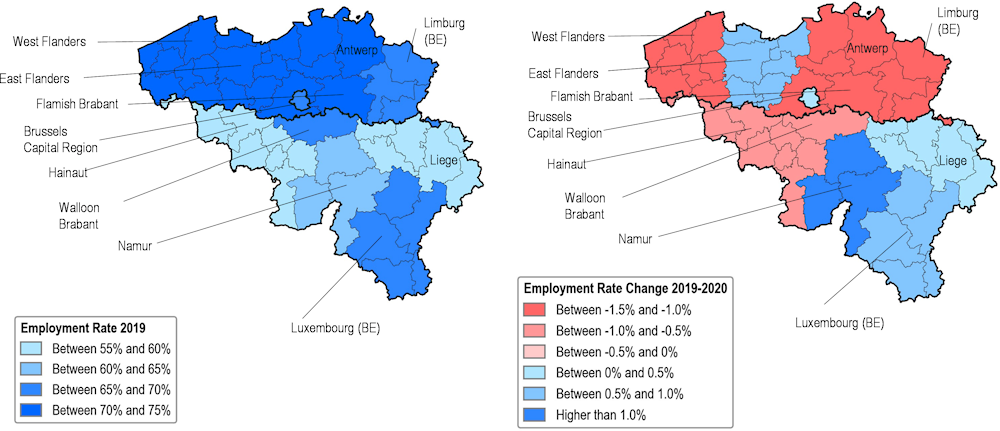

7.2.3. Despite significant regional disparities, labour market trends during the pandemic were relatively similar across regions

The Belgian labour market is characterised by pronounced regional differences: the Flanders region significantly outperforms the Walloon as well as the Brussels Capital region in labour force participation, employment and unemployment rates. Before the pandemic, the employment rate in Flanders was above the EU-28 average at 70%, compared to 58% in Wallonia and 57% in the Brussels Capital region. The unemployment rate in Flanders was 3.4%, compared to 8.5% in Wallonia and 13% in the Brussels Capital region (twice the EU-28 average). Labour mobility between regions is limited because of sometimes inadequate transport links and language barriers as well as low job mobility in Belgium more generally. An above-average vacancy rate, even in the worst-performing regions of Brussels Capital and Wallonia, together with low to middling labour force participation, could indicate some skills shortages (Adalet McGowan et al., 2020[7]).

By contrast, the effects of the COVID‑19 crisis on employment and unemployment were relatively similar, and limited, in all parts of the country, reflecting the effectiveness of the temporary unemployment scheme – as a federal programme – in preventing major job losses. If anything, however, the COVID-19 crisis was associated with a slight narrowing of regional disparities in employment. Over the year 2020, employment rates dropped the most in Flanders (from a high level) while remaining somewhat more stable in Wallonia. In particular, the previously best-performing Flemish provinces West Flanders, Antwerp and Limburg (BE) saw large drops in employment, while employment rates even increased in the Walloon provinces of Namur, Luxembourg (BE) and Liège, as well as in Brussels Capital (Figure 7.4). Stronger employment declines in Flanders may reflect a higher share of temporary agency workers who were more likely to lose their jobs (see Section 7.2.2). JRS receipt was also higher in Wallonia and the Brussels Capital region during the first year of the pandemic, in Brussels in particular because of the importance of urban hospitality services that were among the last to reopen (Vandekerkhove, Goesaert and Struyven, 2022[8]). This might have contributed to a lower pandemic employment dip in these regions.

Figure 7.4. The best-performing regions in Flanders were most affected during the initial phase of the pandemic

Provincial employment and unemployment rates, 2019 levels in percent (left panel) and changes from 2019 to 2020, in percentage points (right panel)

Note: Ages 15-64.

Source: Eurostat.

By 2022, all regions, except Flemish Brabant had reached higher employment rates than before the crisis (not shown). While Flanders still performed more strongly than the Brussels Capital region and Wallonia, the gap certainly shrank, with particularly strong increases in the Brussels Capital region (+5.6 percentage points between 2019 and 2022), Walloon Brabant (+3.8 percentage points) and Luxembourg (BE, +3.7 percentage points). Job mobility in 2021 was significantly higher in Wallonia than in Flanders, which, in the context of record vacancies, might indicate some labour hoarding by employers in Flanders (Vandekerkhove, Goesaert and Struyven, 2022[8]).

7.2.4. The labour market recovery has been swift given the depth of the crisis

The heavy labour market shock experienced during the first pandemic wave in 2020 was followed by a rapid recovery as the public-health situation improved and economic activity quickly resumed. A number of European countries that operated comprehensive JRS, including Belgium, saw a massive expansion in hours worked in the second half of 2020 and early 2021, particularly through a drop of zero‑hours employment (Figure 7.1, Panel B). During this period, many workers resumed their activity as the first pandemic wave subsided, employers adapted workplaces to physical-distancing requirements, and ultimately the first vaccine became available. Hours worked further rose in the second half of 2021 and early 2022, with the change coming mainly from new employment, both in Belgium and across the EU-27 on average. By the second quarter of 2022, hours worked had fully rebounded across the EU-27 on average (Figure 7.1, Panel C).

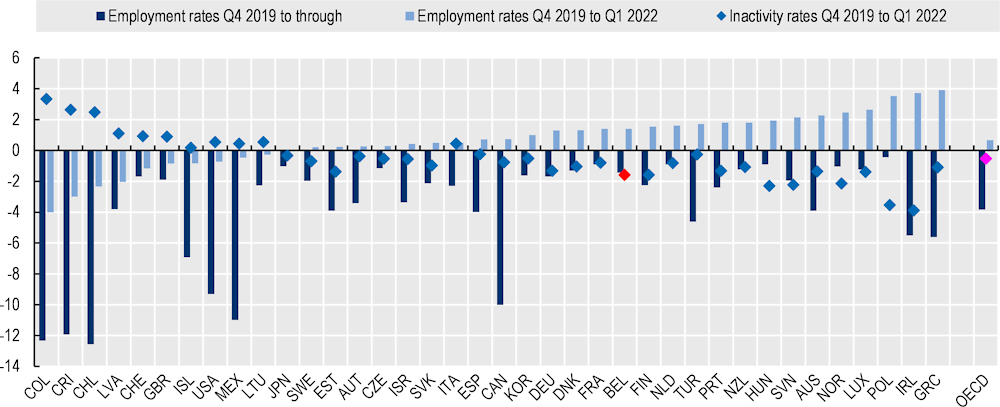

Two years after the start of the COVID-19 crisis, many OECD countries, including Belgium, had largely recovered from the labour market shock caused by the pandemic. In the first quarter of 2022, the employment rate in Belgium surpassed its pre-crisis level, by about 1.4 percentage points (Figure 7.5). Similarly, the inactivity rate had dropped by 1.6 percentage points relative to the fourth quarter of 2019. The unemployment rate had also nearly returned to its pre-crisis level (see also Chapter 6). These trends are much in line with those in many of Belgium’s peer OECD countries, including France, Germany, and the Netherlands, though the employment rate in Belgium remains quite low compared to other European countries (Figure 7.2). Luxembourg experienced an even more impressive labour market recovery, while labour market outcomes were still more subdued in early 2022 in Austria and Switzerland.

Also the labour market situation of young people, as one of the groups most heavily affected by the crisis, has substantially improved: the share of 15-29 year-olds who were not in employment, education or training (NEET) stood at 9.6% in Belgium in 2022, down 3 percentage points from its 2019 level (OECD average of 12.6% in 2022; (OECD, 2023[9])).

Figure 7.5. By early 2022, the employment rate was higher, and the inactivity rate lower, than before the crisis

Percentage point change in employment and inactivity rates among the working age population, Q4 2019 to crisis trough, and Q4 2019 to Q1 2022, seasonally adjusted

Note: Ages 15 to 64. The OECD average is unweighted. “Crisis trough” refers to the country-specific lowest employment rate during the crisis.

Source: OECD short-term Labour Market Statistics.

Overall, countries that operated JRS seem to have had a faster, and more sustainable, recovery than those that relied on temporary layoffs supported by reinforced unemployment insurance programmes. Indeed, employment rates in the first quarter of 2022 where still below crisis levels in Colombia, Chile or the United States, they had increased somewhat in many European countries that featured JRS (Germany, Denmark, France and Finland, for example). Similarly, the increase in inactivity that took place in all countries in 2020, as the pandemic discouraged active job search, had largely been reabsorbed by early 2022. Long-term unemployment (12 months or more), that had fallen in many countries as jobseekers stopped actively looking for work during 2020 and became inactive, also returned to pre-pandemic levels by early 2022 (Salvatori, 2022[6]).

7.3. Policies to protect jobs and incomes in Belgium during the COVID-19 crisis

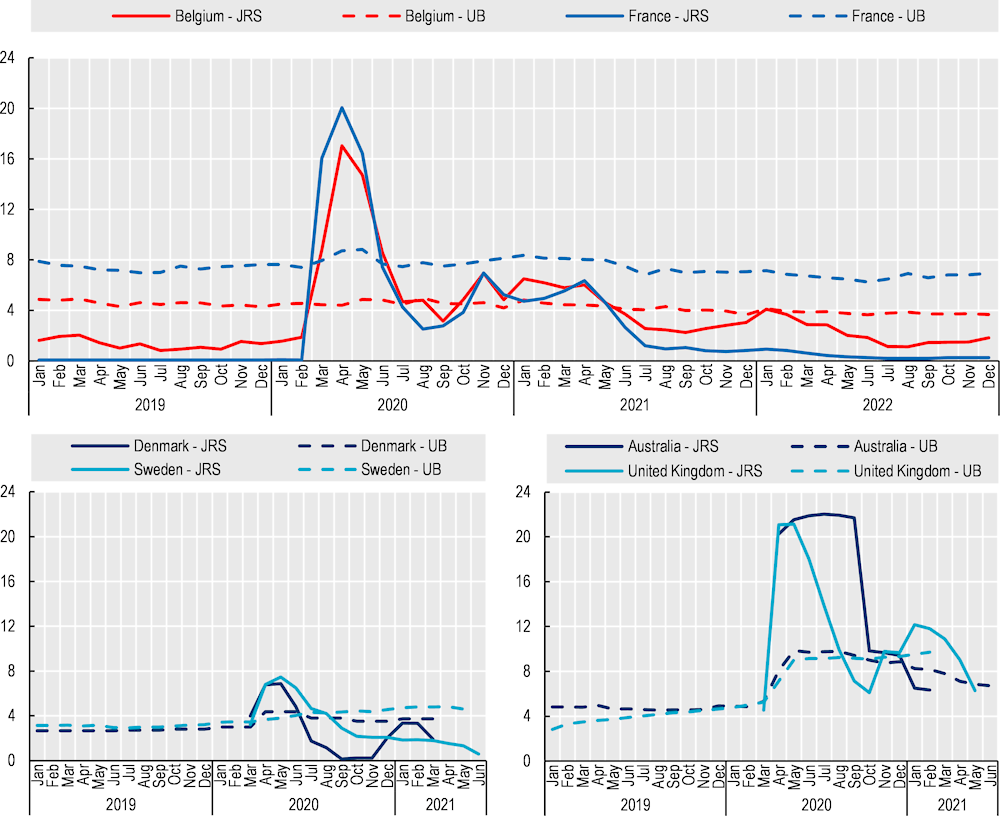

As most OECD countries, Belgium shored up income support following the initial shock of the COVID-19 extensions. The substantial extensions to the pre-existing JRS, the temporary unemployment scheme, made the programme the first line of defence against the pandemic-related income losses. In the spring of 2020, 17% of working-age Belgians were in receipt of JRS payments (Figure 7.6), or the equivalent of about 30% of dependent employment (OECD, 2021[10]). The second main reinforcement of the income support was the substantial extension of the main benefit for self-employed workers, the bridging right scheme, that covered more than half of all self-employed workers in April 2020. In contrast, changes to out-of-work income support were more limited. Moreover, flat receipt rates of both unemployment benefits and means-tested income support for low‑income households indicate that only few workers who lost their job during the crisis relied on those benefits for income support. A Working Group “Social Impact of the COVID-19 crisis”, which pragmatically brought together a range of federal institutions, monitored the socio‑economic impact of the pandemic, evaluated the short-term impact of measures taken, and identified at-risk groups.1

7.3.1. Pandemic extensions to the temporary unemployment scheme achieved broad coverage and generous income support

JRS help preserve jobs at firms experiencing a temporary decline in business activities by subsidising labour costs, and thus encouraging firms to temporarily cut hours instead of laying workers off. This preserves the quality of the worker-firm match and enables firms to quickly shore-up production when conditions improve. While JRS have been used in previous crises, notably the Global Financial Crisis, their use reached unprecedented levels during the COVID-19 crisis, with about 20% of all workers across the OECD in receipt of JRS support. Virtually all OECD countries introduced new or extended existing JRS at the beginning of the pandemic to maximise access. Usual concerns about deadweight loss (supporting jobs that would continue to exist in the absence of JRS) and lock-in effects (supporting jobs with firms that are not economically viable, instead of allowing workers to transition to more productive firms) were of limited or no concern as the policy goal was economic shutdown (OECD, 2021[10]; 2022[11]).

JRS support was overall accessible in Belgium

Already prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Belgium had a JRS in place designed to bridge sudden business closures due to external events such as extreme weather – the force majeure temporary unemployment scheme (chômage temporaire / tijdelijke werkloosheid). In contrast to the JRS that is designed to cushion temporary demand shocks for firms (economic reasons), the force majeure scheme did not require firms to prove economic difficulties or to obtain agreements from worker councils. Belgium further simplified the application procedure during the initial lockdown: firms did not have to prove that they were shut down, employees did not have to submit monthly “control cards” detailing days of work with their usual or a different employer, and the maximum receipt period was abolished. It re-introduced the simplified scheme in October 2020 when the pandemic situation worsened. The simplified procedure was successful in speeding up payments, albeit from a low level: data from the National Employment Office show that in 2020, 76% of all claims resulted in payments within a month, up from 38% in 2019.2

Crucially, and already prior to the pandemic, the force majeure scheme did not require recipients to be permanent employees or to have a contribution history sufficient to qualify for unemployment benefits.3 The scheme does, however, stipulate that an employment contract may not be covered entirely by temporary unemployment benefit payments, which did exclude workers on very short contracts that end or were supposed to start during a shutdown period. The share of very short employment contracts (below three months) is relatively high in Belgium – at about 4% of dependent employment it is above the EU average (about 2.5%), and significantly higher than in peer countries such as the Netherlands, Denmark or Luxembourg (below 2%) (Adalet McGowan et al., 2020[7]). Full-time students still entitled to child benefits who work part-time and do not pay full social security contributions did not qualify either, which was justified by most of them living with their parents (ACV-CSC, 2020[12]).

Figure 7.6. The interplay of job retention support and unemployment benefits across countries

Recipients of job retention scheme support (JRS) and unemployment benefits (UB) as a percentage of the working‑age population

Note: JRS receipt is shown as a percentage of the working-age population, and not dependent employment, as some schemes may be accessed by self-employed workers. For each country, the figures may represent an aggregation across different schemes of the same benefit type. For Belgium, recipient numbers for 2021 and 2022 have been updated using ONEM administrative data. For France, recipient numbers have been updated using Pôle emploi and Dares data. Spikes in recipient numbers in January might be due to reporting reasons. For Denmark, France and Sweden, complete JRS figures are missing before March 2020. For Denmark, JRS numbers refer to two schemes, the pre-existing work sharing scheme and the wage compensation scheme introduced in March 2020; monthly figures for both UB and JRS were interpolated from quarterly time series. For details on the programmes included for each country and methodological notes, please consult the SOCR-HF database.

Source: OECD Social Benefit Recipients Database (SOCR), www.oecd.org/social/social-benefit-recipients-database.htm. Belgium 2021 and 2022: www.onem.be [last accessed 13 July 2023]; France 2021 and 2020: Pôle emploi, https://statistiques.pole-emploi.org/indem/teleindemalloc and Dares https://dares.travail-emploi.gouv.fr/donnees/le-chomage-partiel.

A pre-existing legislative framework, underpinned by a delivery infrastructure, enabled Belgium to achieve this broad coverage with minimum “leakage” to other, lower-tier, support programmes, such as unemployment benefits. Unemployment benefit receipt remained virtually flat throughout the pandemic, even more so than in France where JRS receipt peaked higher and increased slightly at the beginning of the pandemic (Figure 7.6, top panel). Hours contractions were lower in Sweden and Denmark (see Section 7.2.1), as were the peak receipt rates of JRS programmes (Figure 7.6, bottom left panel), while unemployment benefit receipt increased by 1 percentage point in both countries. Australia and the United Kingdom experienced slightly higher inflows into their newly established JRS than Belgium and France, while Unemployment Benefit receipt also rose by 4-5 percentage points, indicating incomplete coverage (Figure 7.6, bottom right panel). In the United States, in contrast, the Paycheck Protection Program remained marginal during the crisis, and unemployment benefits cushioned the bulk of pandemic-related job losses (Denk and Königs, 2022[13]; OECD, 2023[14]).

Belgium, as many other OECD countries, also increased the generosity of the JRS – replacement rates for workers rose from 65 to 70% of net income (with lower and upper thresholds) and an additional flat‑rate top-up of EUR 5.63 per day was also introduced. Additionally, the social partners agreed to top up bonuses for some industries, and around 16% of all JRS recipients received such top-ups (Thuy, Van Camp and Vandelannoote, 2020[15]). Not counting these collectively agreed sectoral bonuses, the overall financial generosity of the programme was slightly below the OECD average – for workers at the average wage, the government bore about 40% of the overall cost, with another 40% borne by workers through lower take-home pay, and the final 20% accounted for by lower employer social security contributions. At the OECD average, governments bore about 61% of the overall costs, and this share was even higher in some peer countries such as Austria, Switzerland, Norway and France (about 80%). Generosity was higher for lower-paid workers because of minimum and maximum payment thresholds. Taking into account the progressivity of the tax system and employer top-ups, Thuy, Van Camp and Vandelannoote (2020[15]) estimate that the monthly net replacement rate (NRR) was over 90% for minimum wage workers, decreasing to 43-47% for high‑earning workers4, depending on employer top-ups. Replacement rates were even higher for workers with dependents.

The Belgian JRS did not foresee any employer co-payments, as it was the case in most OECD countries in the initial phase of the crisis (OECD, 2021[10]). Recent OECD analysis (Unsal et al., forthcoming[16]) compares de jure accessibility and generosity of JRS from the vantage point of firms. Accessibility is measured by required drops in revenues, restrictions of the scheme to specific sectors, length of payments etc, whereas generosity is measured by gross replacement wages, required co‑payments by firm etc. By these metrics, the temporary unemployment scheme was more accessible and generous for firms than programmes in the United Kingdom, Italy, Denmark or the Netherlands.

But phase-out was slow compared to other countries

JRS receipt across OECD countries declined sharply from its peak of about 20% of dependent employment in April/May 2020 to 0.9% in March/April 2022 (Denk and Königs, 2022[13]), reflecting the reduced physical‑distancing requirements as well as policy restrictions. Countries that had introduced new schemes had mostly abolished them by late 2021 (e.g. Australia, Canada, Denmark, New Zealand, the United Kingdom). Other countries restricted access, e.g. by limiting support to sectors that continued to be affected by the crisis (e.g. Luxembourg), or by conditioning support on firms experiencing a decline in turnover (to limit deadweight loss, e.g. France, Austria).

Several countries also made the scheme less generous, either by lowering subsidised net replacement rates for workers, or by introducing or increasing co-financing by firms, especially once labour shortages started to emerge towards the end of 2021 (e.g. Austria, France, Norway or Switzerland). Co‑financing incentivises firms to concentrate support to jobs they deem viable in the medium term, and thus counteracts displacement effects, i.e. the risk that support is going to jobs that have become permanently unviable. Keeping workers in unviable jobs not only adds to the fiscal costs of JRS, but can slow labour reallocation from less productive to more productive firms and reinforce labour shortages (OECD, 2022[11]).

Also in Belgium, JRS receipt rates started dropping in mid-2021, but accessibility to the scheme was again eased in early 2022 to support companies cope with the economic consequences arising from Russia’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine.5 JRS receipt rates in Belgium therefore remained higher than they had been before the crisis (Figure 7.6, top panel), and in the spring of 2022, Belgium and Ireland were the only OECD countries where over 1% of all workers still received JRS support (Denk and Königs, 2022[13]). The lack of co-financing in Belgium likely contributed to persistent JRS use – by late 2021, only a third of OECD countries still operating a JRS did so without any form of co-financing (OECD, 2022[11]).

In a prolonged crisis, the risks of preserving jobs with JRS – deadweight loss and lock-in effects – grow in importance. Especially in a tight labour market, policy should promote labour utilisation, and there would have been scope for Belgium to adapt crisis-related extensions to changing labour market conditions. While JRS recipients were allowed to work in a number of key sectors, and there were some regional efforts to promote training for recipients, few workers combined JRS receipt with work, and training requirements were never introduced (see Box 7.1).

Prolonged use of JRS also increases the potential budgetary cost of fraud. While the simplified payment procedure introduced for the COVID-19 crisis did speed up delivery, it also resulted in overpayments. Especially the suspension of the “employee control card” meant that periods of non‑entitlement (e.g. days worked with another employer) were not always correctly transmitted. While the National Employment Office did perform ex post checks using linked admin data, and has so far recovered over EUR 70 million in overpayments, ex post investigations are more cumbersome, and less likely to lead to successful chargebacks. The OECD is currently working on a separate in-depth review of the Belgian JRS during the COVID-19 crisis.6

Policy recommendations: Ensuring a timely phase-out and effective targeting

Belgium was slower than most other OECD countries to phase out its job retention support. In the event of a future crisis, the accessibility of temporary unemployment could be tied more closely to labour market conditions to reduce the risk that the scheme becomes a hurdle to labour market reallocation in the recovery. This could include:

Ensuring that crisis-related extensions to temporary unemployment support evolve with changing labour market conditions. This could include limiting and softening statutory access requirements (e.g. to specific sectors / conditioning on falls in turnover etc.) as well as rebalancing the requirements of payment speed and monitoring compliance with access requirements with the evolving labour market situation.

Considering requiring employers to make co-payments in a protracted crisis. JRS can produce lock-in effects if they support jobs with firms that are not economically viable and discourage workers from transitioning to more productive firms. Several OECD countries therefore introduced co-payments by firms towards the end of 2021 to incentivise firms to move their workers off JRS support.

Investing in sufficient administrative capacity for a rapid pay-out of temporary unemployment support to those eligible. A large majority of workers on JRS received their payments quickly, but those who had to wait for longer faced often painful temporary income shortfalls. While the higher processing times in these cases often reflected the special circumstances of the pandemic‑related lockdowns, further investments to secure a rapid digital processing of JRS claims would be beneficial.

Box 7.1. Combining JRS receipts with other employment and training

Combining JRS with employment in other firms

In April 2020, Belgium introduced the possibility for JRS recipients to work in agriculture while retaining 75% of their benefits. In October 2020, this option was extended to the healthcare and education sector; it was abolished in October 2021, only to be re-introduced in January 2022. The number of workers taking advantage of this measure remained low, however – not counting temporary agency workers,1 fewer than 1 000 JRS recipients worked in key industries at any point during the crisis. Low take-up of this measure was likely linked to the skill intensity of key sectors, in particular education and healthcare.

Training

Training requirements for JRS recipients can improve the cost-effectiveness of these programmes by improving the employability of workers, and counter-acting human capital depreciation if JRS receipt is prolonged. However, training in firm-specific skills carries the risk of deadweight loss (as firms carry out training that would have taken place in the absence of any subsidy), while training in transferable skills can run counter to the objective of preserving worker-firm matches. During the COVID-19 pandemic, several countries introduced training incentives, e.g. by re-imbursing costs (e.g. France) or increasing subsidies for hours not worked (e.g. Spain, (OECD, 2022[11])). In Belgium, the complex governance structure of labour market administration – the National Employment Office is responsible for disbursing JRS payments, while regional Public Employment Service (PES) are in charge of active labour market policy – complicated discussions about introducing training offers or requirements. Amid emerging labour shortages, the Flemish region wanted to introduce training requirements for the minority of JRS recipients who were on temporary unemployment over three months, but the national PES did not share recipient information. Employer organisations were worried that workers would take training offers as a signal that their jobs were unviable in the long-term, causing quits and delays upon re-opening. According to a survey by the Flemish PES (VDAB), around one in three long-term JRS recipients engaged in some kind of training activity.

1. Sector information is not available for agency workers.

Source: Information by the National Public Employment Service (ONEM/ RVA) and the Flemish Regional authority.

7.3.2. The bridging right scheme enabled timely support to self-employed workers

Self-employed workers in Belgium have been particularly vulnerable to income losses during the crisis as, like in most OECD countries, they were not entitled to JRS or UB support. This is not a marginal issue: At 15% of total employment, the incidence of self-employment in Belgium was higher in 2022 than in many peer OECD countries, including France (13%), Luxembourg (11%), and Germany (9%), though roughly equal to the Netherlands (16%) and lower than in some southern European countries such as Italy (22%) as well as in the OECD on average (17%; OECD (2023[17])).

The bridging right is unique in the OECD as a dedicated programme for self-employed workers experiencing external shocks

In Belgium, self-employed workers have their own out-of-work benefit, the bridging right (droit passerelle / overbruggingsrecht). It is unique in that it is a social insurance benefit (e.g. claimants have to have been subject to social contributions for the past four quarters) with the purpose to smooth consumption in the case of a sudden income loss; however, it is not an unemployment benefit in the sense that it is not administered by the PES and therefore does not have any job search or activation requirements. Established in 1997, the bridging right initially only preserved social insurance rights (healthcare, sickness and invalidity benefits) and provided a flat-rate benefit in the event of bankruptcy. It was subsequently extended to other situations of forced interruption or cessation of activities (the force majeure pillar), and cessations due to economic hardship (for self-employed workers whose businesses are no longer viable and whose incomes are below a threshold) and a flat-rate cash-benefit was added (Comité général de gestion, 2022[18]). The bridging right is a benefit of last resort in that claimants must prove that they have exhausted all other social insurance benefits, but, with the exception of the economic hardship pillar that may require social assistance receipt, it is not means-tested.7 It is limited to those who are self-employed as their primary activity, and before 2023, it could not be combined with any labour income. Before a reform in 2023, the maximum receipt duration was twelve months over an individual’s entire self-employment career.8 There is no separate contribution payable by workers – it is funded by the social insurance fund for the self-employed (NISSE), supplemented by contributions from the general budget, consistent with the very low claims volumes prior to the pandemic (see below).

Before the COVID-19 crisis, only around 500 people received bridging right payments per year, out of a potentially eligible population of around 35 000 primarily self-employed workers who ceased their self‑employment (Comité général de gestion, 2022[18]). Less than 10% of all cessations are due to bankruptcy, and self-employed workers with unviable businesses may abandon their business for another job or may still have entitlements to unemployment benefits from prior dependent employment. However, the very strict entitlement criteria, in particular if claimed for economic hardship, the cumulation of previous receipt periods over the entire career, and the cumbersome claims procedure (e.g. claimants are required to produce proof from the PES that they are not entitled to UB) likely also contribute to low receipt rates.

Belgium was able to build on an existing infrastructure to achieve broad coverage…

During the COVID-19 crisis, Belgium extended the bridging right force majeure along several dimensions: (i) eligibility: in addition to those who are self-employed in their main occupation, also those who combine self-employment with retirement / dependent work / education could receive the benefit as long as they had paid social security contributions;9,10 (ii) receipt durations: months of receipt do not count towards the maximum entitlement (so those who have exhausted their previous entitlement may still receive the bridging right); (iii) the temporary bridging right can be combined with some other social benefits (up until a maximum threshold).

The temporary crisis measure bridging right could be received by self-employed workers subject to mandatory closures, as well as workers who were indirectly affected by lockdown measures, e.g. due to delivery problems or a drop in demand. Claimants did not have to prove that their activities were affected during the first months of the crisis, a sworn statement was sufficient (De Maesschalk and Geeraert, 2020[19]). In April 2020, more than half of all primarily self-employed workers received the bridging right, a significantly higher share than JRS recipients among dependent employees (Figure 7.7).

Starting in July 2020, claimants had to prove that their activity was affected by COVID-19, and that they had to suspend their activities for at least seven consecutive days. This led to a drop in receipt, but rates were still higher than for dependent employees (Figure 7.7). From June to December 2020, self-employed workers restarting their business could also claim the benefit under certain conditions.11 Self-employed workers not subject to forced closures, but who suffered a significant drop in turnover, were also eligible. There was also a separate benefit for parents who had to interrupt their activities due to school or nursery closures, or because they or their family members were quarantined. These crisis measures were only phased out in March 2022 (see Figure 7.7, (Van Lancker and Cantillon, 2021[20]; Conseil supérieur de l’emploi, 2022[21])).

As with the JRS scheme, quick disbursement of payments was the priority at the beginning of the crisis, and the detection of fraud was hampered by high caseloads and the frequent revision of databases, that complicated an accurate linking-up of data across institutions, as well as the impossibility of on-site checks due to health measures (De Maesschalk and Geeraert, 2020[19]).

Figure 7.7. Over half of all primarily self-employed workers received bridging right support at the peak of the pandemic

Share of self-employed workers (main occupation) receiving bridging rights support, and share of dependent employees receiving JRS support

Note: JRS receipt as a share of dependent employees is necessarily higher than as a share of the working-age population, as shown in Figure 7.6, where JRS receipt is expressed as a share of the working-age population to ensure comparability with countries that grant (some) self-employed workers access to JRS. Bridging right recipient numbers not available before March 2020. *Bridging rights recipients from April to December 2022 are projections.

Source: Number of bridging rights recipients: Working Group Social Impact Crises (2023[22]), (annual) number of insured, main-occupation self‑employed workers: INASTI, JRS recipients: OECD Social Benefit Recipients Database (SOCR), www.oecd.org/social/social-benefit-recipients-database.htm. Belgium 2021 and 2022: www.onem.be [last accessed 13 July 2023], quarterly number of dependent employees: OECD short-term labour market statistics, stats.oecd.org.

… but flat-rate payments impeded precision in targeting

The extended bridging right was comparatively generous: it provided a flat-rate monthly benefit of about EUR 1 300 for self-employed workers without, and EUR 1 600 for those with dependents. Starting in the second lockdown in October 2020, and until September 2021, benefits for self-employed workers whose activities were subject to forced closures were doubled. These amounts contrast with a high baseline share of low-income workers among the self-employed: the average annual income of self-employed workers is only about half that of employees12 (Thuy, Van Camp and Vandelannoote, 2020[15]), and incomes of self‑employed workers are in general more dispersed than those of dependent employees, with a significantly higher incidence of in-work poverty (OECD, 2018[23]; Horemans and Marx, 2017[24]; Wizan, Neelen and Marchal, 2023[25]).

Thuy, Van Camp and Vandelannoote (2020[15]) estimate that the net replacement rates for self-employed workers, not counting the doubled benefit amounts introduced in October 2020,13 ranged from 74% for low-income self-employed workers (at 67% of the average income) to 37% for high-income workers (167% of the average income), taking into account the progressivity of the tax system. This implies replacement rates of over 100% for low- to average self-employed workers from October 2020 onwards. Similarly, Marchal et al. (2021[26]) estimate the initial impact of the COVID-19 crisis in April 2020 on household incomes. They find that the poorest 20% of self-employed households experienced an increase in disposable household income of more than 50%, mostly because of very low pre-transfer income before the crisis, and flat-rate bridging rights payments. Only households in the second income quintile were perfectly compensated for their losses, whereas the 20% of self-employed households with the highest incomes experience a loss in disposable income of over 60%.

Overpayments at the low, and incomplete consumption smoothing at the high end of the income distribution are a drawback of flat-rate payments. In a crisis situation, flat-rate payments are easier to administer as they do not require administrative structures to assess previous incomes, which is more complex for self‑employed workers than for dependent employees as their earnings fluctuate, and recent tax returns are often subject to revision. Some countries that newly introduced benefits tied to previous earnings during the COVID-19 pandemic therefore relied on self-certification of losses (e.g. Austria), while others, including France and Italy, also provided flat-rate payments. Given that emergency income support payments, including the bridging right, are funded by the general budget, overpayments for low-income households are easily justifiable. In light of (welcome) current policy efforts to increase the coverage of the bridging right (e.g. Algemeen Beheerscomité / Comité général de gestion (2022[18])), Belgium should consider tying benefit amounts to previous contributions to increase the benefit’s insurance value and attenuate moral hazard.

Policy recommendations: extending the bridging right into an effective income replacement benefit for self‑employed workers

The bridging right achieved high coverage among self-employed workers during the COVID-19 crisis in Belgium and was essential in maintaining the livelihoods of self-employed workers who would otherwise not have had access to income support. However, flat-rate payments mean a loss in targeting precision, which may have led to overpayments. Before the COVID-19 crisis, the bridging right was characterised by very low receipt rates, possibly reflecting and overly stringent eligibility conditions. This established benefit could be extended to further improve income security for the self-employed while promoting an efficient labour allocation in a changing labour market. This could include:

De-coupling maximum receipt durations across pillars. In line with the recommendation of the Algemeen Beheerscomité / Comité general de gestion (2022[18]), previous bridging right receipt, especially because of forced interruptions, should not impinge upon later receipt if other eligibility conditions are met. Maximum receipt durations can still be applied for each event.

Tying benefit amounts to previous social-security contributions. During the COVID-19 crisis, net replacement rates for the large share of low-income self-employed workers were frequently over 100%, which makes the programme expensive and can induce moral hazard. Replacing the current flat-rate benefits with earnings-dependent payments would improve the insurance value of the bridging right, increase cost-effectiveness, and limit moral hazard.

Improving the accessibility of the benefit, in particular for the economic-difficulties pillar. Receipt of the bridging right because of economic difficulties is low, likely because of strict eligibility requirements: some administrative hurdles seem difficult to overcome for claimants (e.g. the requirement to produce a certificate of non-entitlement to unemployment benefits from the public employment service (Comité général de gestion, 2022[18])) while the means-test of the benefit – e.g. the requirement to receive Social Assistance – will exclude those living with other income‑earners. But coupled with adequate employment support (see below) the benefit could help self-employed workers with unviable businesses to find other work, supporting the efficient allocation of labour, in particular in times of labour shortages.

Coupling the receipt of bridging right payments due to economic difficulties to similar behavioural requirements as they exist for dependent employees that lose their job. Unlike in the case of force majeure, self‑employed workers who receive the bridging right because of economic difficulties need support to transition into better work. Requiring them to register with the public employment service and participate in job search support and training may help them move into dependent employment. Almost all countries that offer income support to self-employed workers require them to actively seek and accept dependent employment (OECD, 2023[27]).

Considering making the bridging right a proper unemployment insurance benefit by introducing separate contributions to balance payments and contributions. Bridging right receipt in “normal” times is very low, which makes its funding out of existing social insurance contributions by the self-employed, complimented with general-revenue funds, viable. If the benefit were reformed with the aim of improving coverage, these extensions should be counterbalanced by contributions on equity grounds, but also to prevent too high labour cost differentials between dependent employees and independent contractors.

7.3.3. The (extended) Unemployment Benefit provided income security to entitled jobseekers, but likely was not accessible to all in need

Income support for workers affected by job losses was a second pillar of countries’ efforts to cushion the effects of the COVID-19 crisis on workers and households. While the extension of the JRS achieved broad coverage in Belgium, the unemployment rate did increase by 1.5 percentage points in 2020 (see Section 7.2). Finding new employment was difficult or impossible during lockdown periods, including for jobseekers that were already without work prior to the pandemic. Unemployment benefits and other out‑of‑work income support played a vital role in protecting workers and families’ livelihoods during these periods.

Belgium’s Unemployment Benefit (UB) offers comparatively high replacement rates in the OECD comparison. At the beginning of the unemployment spell, the share of the previous net income replaced through UB, the net replacement rate (NRR), for an average-wage worker is 67%. This is higher than the OECD average (55%), and similar to peer countries such as France and the Netherlands, albeit lower than Luxembourg (Figure 7.8, Panel A). An exceptional feature is the (in principle) unlimited duration of UB, whereas in most OECD countries, payments lapse after six months to two years (OECD, 2023[14]). Payment amounts in Belgium progressively decrease over time towards a flat-rate amount, with the speed of adjustment dependent on contribution history.

Belgium froze payment amounts from April 2020 to October 2021 acknowledging the difficulty of searching for a job during lockdown. This measure is likely to have had a significant impact on household incomes, especially for average to higher earners: for workers with previous earnings at the average wage who lost their job in April 2020, payments would have declined by 17% of the average wage at by the end of 2021 (Figure 7.7, Panel B). Over 100 000 jobseekers benefitted from this measure in 2020 (Conseil supérieur de l’emploi, 2022[21]). Belgium also extended the duration of the integration allowance, an unemployment benefit for young people leaving education that is normally capped at 36 months: the 18 months between April 2020 and September 2021 did not count towards this maximum duration. Around 50 000 young people benefitted from this measure in 2020 (Conseil supérieur de l’emploi, 2022[21]).

While UB payments and maximum receipt durations are generous, benefits are not very accessible: the minimum contribution period was 16 months in January 2020, compared to seven months across the OECD on average, twelve months in peer countries including Switzerland, Denmark and the Netherlands, and only one to four months in Germany, Luxembourg or France. Only Hungary had a significantly higher minimum contribution period (Figure 7.8, Panel B). Nonetheless, Belgium generally achieves very good benefit coverage among jobseekers: prior to the crisis, it was one of the few OECD countries in which the number of UB recipients exceeded the number of unemployed according to ILO definition, i.e. Belgium had a UB “pseudo‑coverage rate” of over 100% (OECD, 2018[28]; 2018[29]).

Figure 7.8. Belgium improved the generosity, but not the accessibility, of Unemployment Benefits

Net replacement rates and minimum contribution periods of Unemployment Benefits

Note: In Panel A, the net replacement rate (NRR) gives the share of a worker’s previous net income that is replaced through unemployment benefits. The jobseeker is assumed to have a “long” contribution record. No social assistance or housing top-ups.

*Data refer to 2019 and 2020 for the United Kingdom and New Zealand: TaxBEN implements COVID-19 emergency measures already in 2020 for these countries as their reference date is at the beginning of their fiscal year in April, in contrast to 1 January 2020 for the remaining countries. Both panels include unemployment insurance and assistance benefits. 40-year-old living alone with previous earnings at the national average wage.

Source: OECD TaxBEN model (version 2.6.0) http://oe.cd/TaxBEN.

Some workers with short contribution histories therefore likely only had access to means-tested Social Assistance benefits (7.3.4). Belgium’s relatively high incidence of temporary workers, in particular with very short contracts, exacerbates the barrier high minimum contribution periods pose. Temporary workers were more likely to lose their jobs during the crisis (Section 7.2.2) and were not covered by the JRS (Section 7.3.1). UB receipt rates did remain flat during the crisis despite the rise in unemployment (Figure 7.6), indicating incomplete accessibility. Given the special nature of the COVID-19 crisis, Belgium could have considered reducing UB minimum contribution periods or offering payments for a limited duration to jobseekers with short contribution histories. This would improve benefit coverage particularly for workers on temporary contracts, including young people and migrants, who often could not access temporary unemployment benefits. Indeed, a number of countries, including Canada, Spain and the United States decreased minimum contribution periods to one month of work or less at the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis to prevent coverage gaps (see Figure 7.8, Panel B, and Denk and Königs (2022[13])).

7.3.4. Minimum-income benefits play a minor role in the Belgian welfare state and its COVID-19 crisis response

In contrast to unemployment benefits, Minimum Income Benefits (MIB) do not require previous contributions – they are awarded on the basis of need. During economic crises, and in the context of volatile or insecure labour markets, these benefits of last resort provide a crucial final layer of social protection, available for those who are not entitled to other support or who, with other support, do not reach the minimum income.

Social Assistance plays a minor role in Belgium, and coverage is comparatively low

MIBs play a comparatively small role in Belgium’s benefit architecture. While public benefits account for over 10% of the total incomes of working-age households in Belgium, over 80% of these payments are contribution-based, with means-tested payments accounting for less than 10% of working‑age household incomes, compared to over 20% in Germany or 35% in France (OECD, 2023[14]). Since UB are not time‑limited, the “space” for MIB to operate is restricted to those with insufficient contributions to qualify for UB. The group of potential beneficiaries is thus smaller than in other countries, and likely more vulnerable: they are more likely to live in complex socio-economic circumstances, and may find it harder to navigate sometimes complex and lengthy application procedures and to comply with behavioural requirements of benefit receipt (such as active job search, or regular contact with the relevant administering agencies).

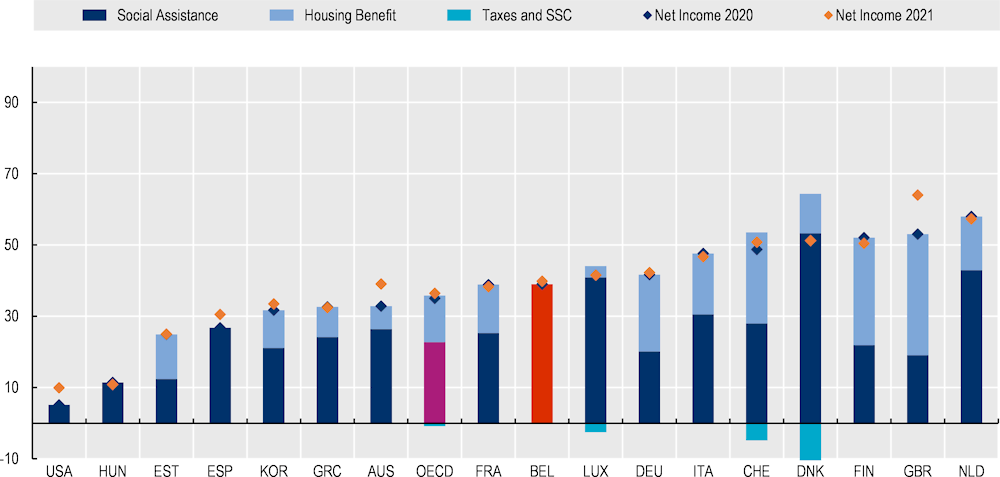

The generosity of MIBs in Belgium can be described as middling – a jobless adult living alone with no other source of income receives Social Assistance (SA) benefits amounting to 40% of the median household income. This is higher than the OECD average at 36%, but below the standard poverty lines of 50% or 60% of median disposable equivalised household income used by the OECD and Eurostat. It is significantly lower also than in peer countries, including the Netherlands (58%), or Switzerland, Denmark and Finland (around 50%, Figure 7.9). Housing is a regional competency in Belgium, and there is no separate Housing Benefit.

Figure 7.9. The generosity of minimum income benefits in Belgium is somewhat below peer countries

Minimum income benefits for a jobless adult living alone, in percent of the median household income, January 2020 and 2021

Note: Data refer to 2019 and 2020 for the United Kingdom and New Zealand (TaxBEN implements COVID-19 emergency measures already in 2020 for these countries as their reference date is at the beginning of their fiscal year in April, in contrast to 1 January 2020 for the remaining countries). The OECD average includes all countries with available data (see http://oe.cd/TaxBEN). Minimum Income Benefits include Social Assistance, Housing Benefits, and non-work-related tax and social security contribution credits. Able-bodied 40-year-old living alone, with no labour income and no entitlement to unemployment benefits, who passes the asset test of each programme. For Belgium: Revenu d’intégration sociale / Leefloon.

Source: OECD TaxBEN model (version 2.6.0), http://oe.cd/TaxBEN.

At least in terms of asset tests, however, the working-age SA benefit (Revenu d’intégration sociale / Leefloon) is comparatively accessible: in most EU countries, financial assets below certain (low) thresholds, as well as significant movable property, must be realised before claiming MIB, although owner‑occupied housing is often exempt. In Belgium, in contrast, fictional rates of return (imputed rents in the case of owner-occupied housing) are counted as income – they can diminish MIB benefit amounts, but do not lead to outright disqualification (Marchal et al., 2020[30]).

Empirical coverage among households who do not have income from work or contributory benefits is incomplete, however, especially compared to peer countries: only about 60% of jobless adults whose income from work or earnings-replacement benefits puts them in the bottom 10% of the income distribution received any MIBs before the COVID-19 crisis, compared to 80% or over in Austria, Germany, Australia, France or the United Kingdom (Hyee et al., 2020[31]). This may be related to relatively low take-up: about 50 to 60% of all households who would be entitled to the social integration income are estimated to actually receive the benefit (Goedemé et al., 2022[32]). While take-up rates of social benefits very widely across countries and benefits, this is at the low end of the spectrum (OECD, 2023[33]). Belgium is currently undertaking a variety of measures to improve the take-up of a range of social benefits (OECD, forthcoming[34]).

Crisis support for vulnerable households was comparatively limited

During the COVID-19 crisis, receipt of the SA benefit only increased slightly, rising from around 158 000 to 168 000 claimants between January and December 2020 (Working Group Social Impact Crises, 2023[22]). This clearly reflects the effectiveness of the Belgian JRS at absorbing most of the pandemic‑related shock to the labour market. However, given that joblessness did increase (see Section 7.2.2) and that UB receipt remained flat (see Section 7.3.1), the only-modest rise in Social Assistance receipt implies that many of those who lost their jobs may not have received income support. This may be because they lived in households with other earners, and therefore did not reach the level of need that would have entitled them to SA, or because they did not take up these benefits even though they were entitled. Any firmer conclusions on the income effects of job loss during the crisis, and potential coverage gaps, would require microdata analysis. Unfortunately, the survey-based micro data used in the analysis presented in Section Figure 7.4 do not provide sufficiently detailed information on labour market trajectories to permit such analysis. Administrative data on the income of spouses and cohabiting partners of those who lost their jobs in the crisis would thus be necessary, but such data are currently not available for research.

While there was no strong increase in the number of SA recipients, local welfare offices did record an increase in demand for help, most notably in advances for JRS payments and food aid. The simplified claims procedure did speed up JRS payments (see Section 7.3.1), but about 5% of all claims took three months or longer to administer,14 leading to significant liquidity problems for recipients who were concentrated in the lower wage deciles (Federal Public Service Employment, Labour and Social Dialogue and UNIA, 2022[3]; De Wilde, Hermans and Cantillon, 2020[35]). Food banks experienced a strong increase in demand, notably from young people who lost student jobs that were not included in the JRS (Section 7.3.1) and lone parents – demand for food aid at municipal welfare offices increased by over 50% in the first quarter of 2020, and also other foodbanks experienced an increase in demand, while struggling to continue to provide service amidst a decline in often older volunteers (SPP Intégration sociale, 2020[36]; De Wilde, Hermans and Cantillon, 2020[35]).

To reinforce income support for SA recipients, Belgium topped-up benefit amounts of the working‑age Social Assistant benefit and other related benefits for disabled people and the elderly by EUR 50 per month until September 2021, and EUR 25 per month until March 2022 (Van Lancker and Cantillon, 2021[20]). This came in addition to the regular adjustments of Social Assistance benefit amounts in March 2021 and January 2022. The impact of this measure of household incomes was limited, whereas other countries, such as the United Kingdom, Australia and Spain significantly increased payments to MIB recipients (Figure 7.9).

Belgium also provided direct support to municipal welfare offices amounting to EUR 135 million until June 2021.15 Local welfare offices were not provided with guidance on how to best allocate these funds, which makes it difficult to evaluate the effectiveness of this measure (Cour des comptes, 2021[37]). Local municipal welfare offices may also have lacked the capacity to conceive and administer effective ways to use these funds. Given the relatively low generosity of MIBs in Belgium, it might have been preferable to top-up other benefits for low-income households, or to make MIBs more accessible and generous. E.g. Australia and Germany waived asset tests for their MIBs (OECD, 2020[38]).

An over-reliance on the digital provision of social services may diminish accessibility for the most vulnerable

Like many countries, Belgium migrated most of its benefit administration and social service delivery online to comply with public health requirements. This guaranteed the continuity of essential services while safeguarding employee and beneficiary health. Digital administration of social benefits and services – e.g. digital claims procedures – can make them more accessible for those with access to the appropriate equipment and sufficient digital skills. However, an over-reliance on digitalised services risks diminishing accessibility for some of the most vulnerable groups, who are less likely to have the necessary skills or equipment (OECD, forthcoming[39]). Low-income households for instance are much less likely to have access to the internet, and some groups almost exclusively rely on in-person access to benefits and services, such as the homeless (Service de lutte contre la pauvreté, 2021[40]).

While limitations to in-person service provision were a necessity during times of contact restrictions, there are indications that in-person accessibility has not yet everywhere been rolled back to pre-pandemic levels (Vaes, 2023[41]). Complex claims procedures and administrative hurdles in accessing benefits are among the main reasons for low take-up of social benefits (OECD, 2023[14]). Restricting opening hours and introducing obligations to make an appointment online or by phone, maybe with waiting times, creates barriers to access, especially for those who do not have digital access or skills, as well as those who have complex needs and who might require personal assistance to identify the right benefit or service for them and help with the claims process. Countries trying to improve take-up of benefits and services therefore try to combine digital with in-person, low-threshold offers (OECD, forthcoming[34]).

Policy recommendations: ensuring adequate and accessible social benefits and services for the most vulnerable

While emergency extensions to temporary unemployment and bridging right benefits were generous and achieved broad coverage during the COVID-19 crisis, the working-age benefit of last resort was only increased by a comparatively small amount, and access was not eased at all, meaning that those not entitled to higher-tier benefits did not receive a lot of additional support during the crisis. In future crises, Belgium could do more to support the incomes of the most vulnerable households. This could include:

Considering more substantial increases in minimum-income benefits. Payment rates of Social Assistance are somewhat less generous in Belgium than in peer OECD countries, and recipients only received small top-ups during the crisis. Part of the substantial, additional financial support provided to municipal welfare offices may have been better employed for more significant increases in income support for the most vulnerable. This could have also contributed to raising the relatively low benefit coverage.

Improving the in-person accessibility of social welfare offices to increase the take-up of minimum-income benefits and social services. The digitalisation of services can save costs and simplify access for some users, but maintaining low-barrier in-person support is essential for the most disadvantaged who may lack the means to access services digitally (OECD, forthcoming[39]).

7.4. Low incomes were well protected during the initial phase of the pandemic

The severe economic crisis and the extraordinary measures taken by Belgium to protect jobs and incomes led to a major rise in social expenditures. Relative to 2019, real public social expenditures in Belgium increased by 8% in 2020 (Figure 7.10). This is broadly in line with increases observed in peer countries, such as Austria (+6%), France and Germany (both +7%), but lower than in Luxembourg and the Netherlands (12-14%). Across the OECD on average, real public social expenditure expanded by around 12%, reflecting very high year‑on‑year spending increases in countries such as Canada (32%), Ireland (28%) and the United States (29%), but only minor increases in some Nordic and southern European countries. These large cross-country disparities in pandemic social spending reflect differences in (i) countries’ policy responses, notably the level and type of income support provided and the extent of targeting; (ii) the labour market impact of the pandemic; and (iii) pre-crisis social spending levels. For example, in 2019, public social spending as a share of GDP accounted for over 25% in Belgium, Austria, France, Germany, compared to only about 12% in Ireland, and about 18% in the United States.

The bounce in social spending observed during the COVID-19 pandemic was substantially more pronounced than during the 2007/8 Global Financial Crisis, in Belgium and across the OECD on average, but it was also more short-lived. Real public social spending in Belgium plateaued in 2021 at its elevated level, before declining again in 2022 (Figure 7.10). Very similar trends can be observed in Austria, France, Germany, and the Netherlands. In all of these countries, spending levels in 2022 remained a few percent above their pre-crisis levels in real terms.

Figure 7.10. Public social expenditures in Belgium expanded in line with those in peer OECD countries and have declined again since

Real public social expenditure index (2019 = 100), OECD average and selected countries, 2006-22

Note: The OECD average is unweighted and likely gives an underestimate of true spendings levels for 2021 and 2022 because data are still partly missing for many non-European countries, where spending increases during the pandemic were particularly high.

* projected values, for details see (OECD, 2023[42]) and notes therein

Source: OECD Social Expenditure database (www.oecd.org/social/expenditure.htm), adapted from (OECD, 2023[42]).

Thanks to the comprehensive measures taken to protect job and incomes, Belgium managed to prevent major income losses for large parts of the population. The median disposable household income in Belgium – i.e. the income after taxes and transfers for the person in the middle of the income distribution after adjusting for household size – increased in nominal terms from 2019 to 2020, by 1.7%, to about EUR 28 900 (OECD, 2023[43]). After accounting for inflation, this still translates into a marginal rise by 0.6%, a figure in line with those recorded in Austria, Finland and Sweden. Some other countries experienced even more notable median income growth during the first pandemic year, including the Netherlands, the United States, and particularly Luxembourg. Standardised income distribution data for France and Germany are still lacking at the time of writing of this chapter, as are income data for the years 2021 and 2022.