The COVID-19 pandemic put enormous stress on health systems, forcing them to cope with an unknown pathogen while also continuing to deliver routine care and respond to acute care needs unrelated to the pandemic. This chapter assesses the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on health and on the health system in Belgium. It looks at the direct and indirect health impacts of the pandemic and the effectiveness of the health system’s response, with a particular focus on the impact of the pandemic on vulnerable groups.

Evaluation of Belgium’s COVID-19 Responses

4. The health systems response to COVID-19 in Belgium

Abstract

Key findings

A number of weaknesses in pandemic preparedness complicated Belgium’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic and led it to fare poorly during 2020, the first year of the pandemic. The adjusted increase in deaths in 2020 was more than twice the OECD average, indicating how hard the initial waves of the pandemic hit Belgium. The decision to dispose of and not replenish the strategic stockpiles of personal protective equipment prior to the pandemic, and differing rules around allocation to different parts of the health system, meant that some operators of critical infrastructure and essential health and social care services faced major shortages. Nursing homes were ill-equipped in terms of infection control expertise and often faced major problems sourcing key protective equipment. Moreover, the political situation at the outset of the pandemic, the multitude of often overlapping crisis structures set up to address the pandemic, and the lack of clearly assigned responsibilities meant that in practice crisis response channels were sometimes side-lined in favour of decisions made directly by a fairly small group of actors.

Older populations, especially those in nursing homes, and other vulnerable groups were particularly hard hit, particularly in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Nearly half (45%) of all COVID-19 deaths in Belgium were among residents of nursing homes between early 2020 and September 2022. Nursing home residents, of which Belgium has a higher share than nearly all other OECD countries, comprised nearly three in five deaths (57%) in 2020. Belgium made several attempts to integrate the unique circumstances of vulnerable groups, such as homeless people and undocumented migrants, in its decision making, for example through representation of advocates in key crisis management bodies. However, their needs were not always prioritised particularly in the initial months of the crisis response. The severe impacts on these population groups and the major challenges encountered around certain basic pandemic preparedness measures, such as the procurement of personal protective equipment, underscore that Belgium could do much more to prepare proactively for future health crises, particularly for vulnerable populations.

Despite these shortcomings, the Belgian health system was able to respond fairly robustly to the challenges it faced from the COVID-19 pandemic and to adapt over the course of it, leading to an improved response in 2021 and 2022. Through March 2022, the direct health impact of COVID-19 in Belgium was lower than the OECD average and comparable to that of many neighbouring countries, with the average adjusted increase in deaths between 2020 and 2022 some 2.5% higher than the 2015-2019 period, compared with 5.3% higher across the OECD on average for the same period. Many of the measures taken by Belgium in responding to the crisis, such as the management of hospital capacity and the roll-out of the vaccination campaign, were broadly successful when compared with other OECD countries. Belgium incorporated lessons learned from the first two waves into its pandemic response, which resulted in a much better performance in 2021 and 2022 compared to 2020.

The pandemic holds several lessons learned to ensure that Belgium continues this path to prepare proactively for future health crises, particularly for vulnerable populations:

The indirect health impacts of the pandemic were serious, with delays in routine care and significant impacts on mental health, particularly for young and vulnerable populations, as well as certain professions.

Long COVID remains a concern for an important subset of people who contract COVID-19, with concerning implications not only for health but also employability and broader well-being.

The impact of the pandemic on the mental health of healthcare workers who were on the front lines of the crisis has been significant.

Despite the complexity of Belgium’s crisis response management, several of the health initiatives adopted to fight the virus were largely successful:

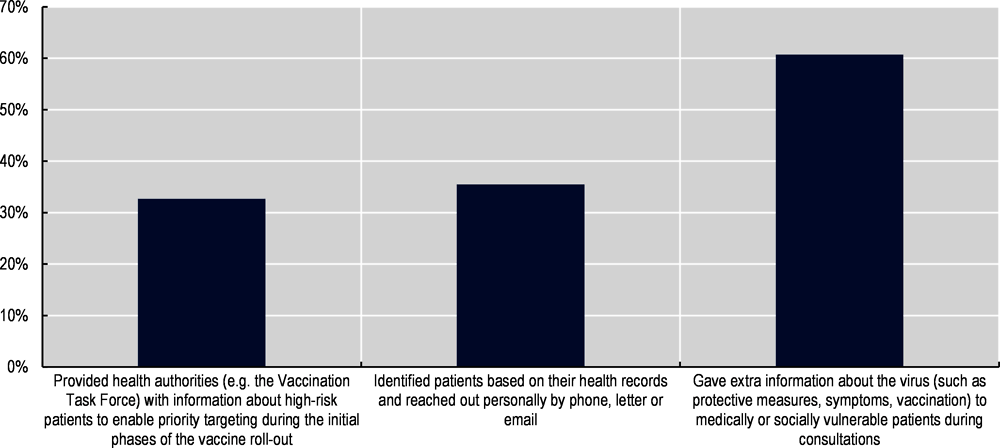

Belgium’s vaccination campaign was rolled out quickly and strategically, with identification and prioritisation of key vulnerable groups and good co-ordination between the federal government and federated entities. As of March 2022, nearly four-fifths (78%) of the total population had completed their vaccination protocol, a share higher than the OECD average and above the neighbouring countries of France, Germany, Luxembourg and the Netherlands.

A relatively high number of hospital beds, as well as a tightly organised hospital response, and the development of a multi-stage hospital contingency plan, helped prevent hospitals from becoming overwhelmed during the crisis.

Data was quickly collected to monitor the spread of COVID-19 and facilitate informed decision making, with a new data infrastructure for information from hospitals and nursing homes scaled up at the start of the crisis.

Belgium was able to address some workforce shortages exacerbated by the pandemic through a range of strategies, including support from medical and non-medical volunteers, the deployment of military personnel to some nursing homes and hospitals, and task shifting.

Care delivery approaches were adapted during and following the pandemic to help ensure access to, and continuity of, care:

Reimbursement for teleconsultations was quickly approved. While widely used, the take-up of teleconsultation services remains lower than many neighbouring countries.

New models of primary care delivery were harnessed to improve the co-ordination of care for both COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 patients and to identify patients particularly vulnerable to the impacts of COVID-19 and its mitigation measures.

Support for mental health services was expanded, with a scale-up in funding for mental health services and strengthening of primary-level mental health support.

Clinical pathways supporting care for long COVID have been introduced to improve the co-ordination of care around specific patient needs.

4.1. How hard hit was Belgium by COVID-19? The direct health impact of COVID-19

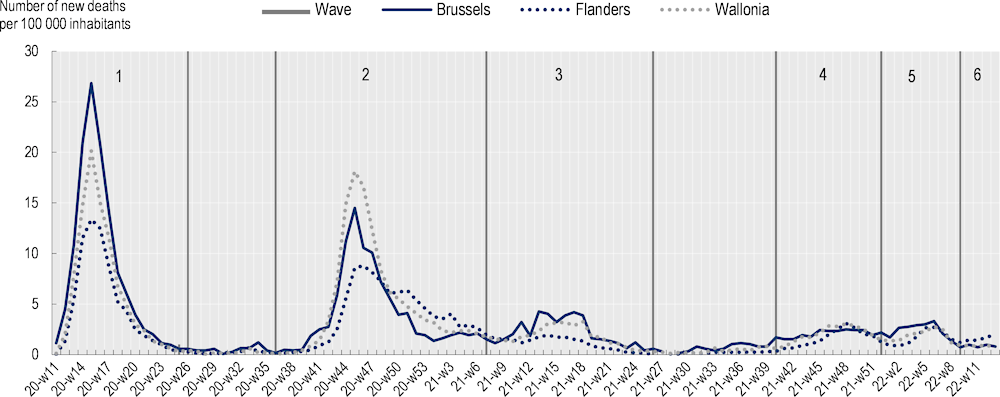

4.1.1. Belgium recorded its highest number of deaths in waves one and two

While Belgium’s first COVID-19 patient was detected on 4 February 2020 in an asymptomatic person returning from Wuhan (Renard et al., 2021[1]), a second case detected on 1 March 2020 marked the start of the pandemic in the country (Renard et al., 2021[1]). Over the period covered in this report, Belgium experienced six COVID-19 waves (Figure 4.1) and incurred a total of 30 811 COVID-19-related deaths between its first COVID-19-related death on 7 March 2020 and the end of March 2022: 4 073 deaths in Brussels, 11 122 deaths in Wallonia and 15 616 deaths in Flanders.

Waves one and two were by far the most severe in terms of mortality, accounting for 70% of total COVID-related deaths over the period from March 2020 to March 2022. The country recorded the highest number of daily deaths in wave one, with a total of 322 deaths on 8 April 2020, and the highest number of deaths per wave in the second wave, with a total of 11 949 COVID-19-related deaths (Peeters et al., 2021[2]; Bustos Sierra et al., 2021[3]).

Figure 4.1. Weekly new deaths per region per 100 000 inhabitants

From March 2020 to March 2022

In terms of absolute mortality, Belgium appeared as an outlier, with absolute cumulative mortality ranging far above that of many other countries in the initial months of the pandemic (Luyten and Schokkaert, 2021[6]). This can in part be attributed to a broader inclusion of deaths. In contrast to many other countries that initially only counted confirmed, in-hospital COVID-19 deaths, Belgium included both suspected COVID-19 deaths and deaths that occurred outside of hospitals in its mortality data from the start of the pandemic, as a way to limit underreporting of cases (Bustos Sierra et al., 2020[7]; Renard et al., 2021[1]).

4.1.2. The increase in mortality in Belgium was higher than in neighbouring countries in 2020 but lower than in most OECD countries in 2021 and 2022

During the pandemic – and particularly early in 2020 – many countries measured the relative and absolute impact of the pandemic in terms of the number of positive cases, hospitalisations due to COVID-19, and COVID-19-related deaths. While these measures were relatively straightforward to include in health information systems and are helpful for within-country analyses, international comparisons based on these measures are difficult to interpret, due to differences in identifying all COVID-19 related cases and deaths, different approaches and capacities to testing for COVID-19, and different practices in recording probable but not test-confirmed cases. A comparison of the overall number of deaths recorded in a period against a ‘baseline’ – the average number of deaths during the same period in recent years – can help to address many of these comparability challenges. This simple measure of ‘excess mortality’ provides a proxy for the overall impact of COVID-19. In looking at overall deaths, the impacts of the pandemic are captured not only through deaths directly linked to COVID-19, but those who may have been missed (for example, due to place of death or lack of testing) as well as deaths that could be linked to missed or delayed treatment due to the pandemic. This measure is particularly appropriate when undertaking international comparisons, where the measurement challenges highlighted above complicate direct comparisons of official COVID-19 cases and deaths.

There are a variety of approaches on how to measure excess mortality, using different underlying data, and calculating ‘expected’ deaths using different baseline periods, standardisations, and trends (Schöley et al., 2023[8]). Such methodological differences mean that there are differences in the magnitudes reported across different studies, as well as some challenges in interpreting their results. In common with other international studies, OECD estimates use an age-standardised mortality rate (ASMR) approach to take into account variations in population structure and size – that themselves impact mortality in a given country and over time – while still comparing against a historical baseline average. As such, they capture changes in overall mortality over time and between countries, rather than focusing explicitly on COVID-19-related mortality as some other models (such as that of WHO) have attempted to do. While there are differences in the estimates of excess mortality, other approaches to calculate the impact on mortality tend to arrive at similar results in term of relative levels and trends over time and between countries (Office for National Statistics, 2022[9]; Eurostat, 2023[10]). Using a more sophisticated modelled (extrapolated) mortality baseline would have led to a higher estimated excess mortality for countries where life expectancy was improving and all-cause mortality was declining prior to the pandemic, and can lead to slightly different relative country rankings.

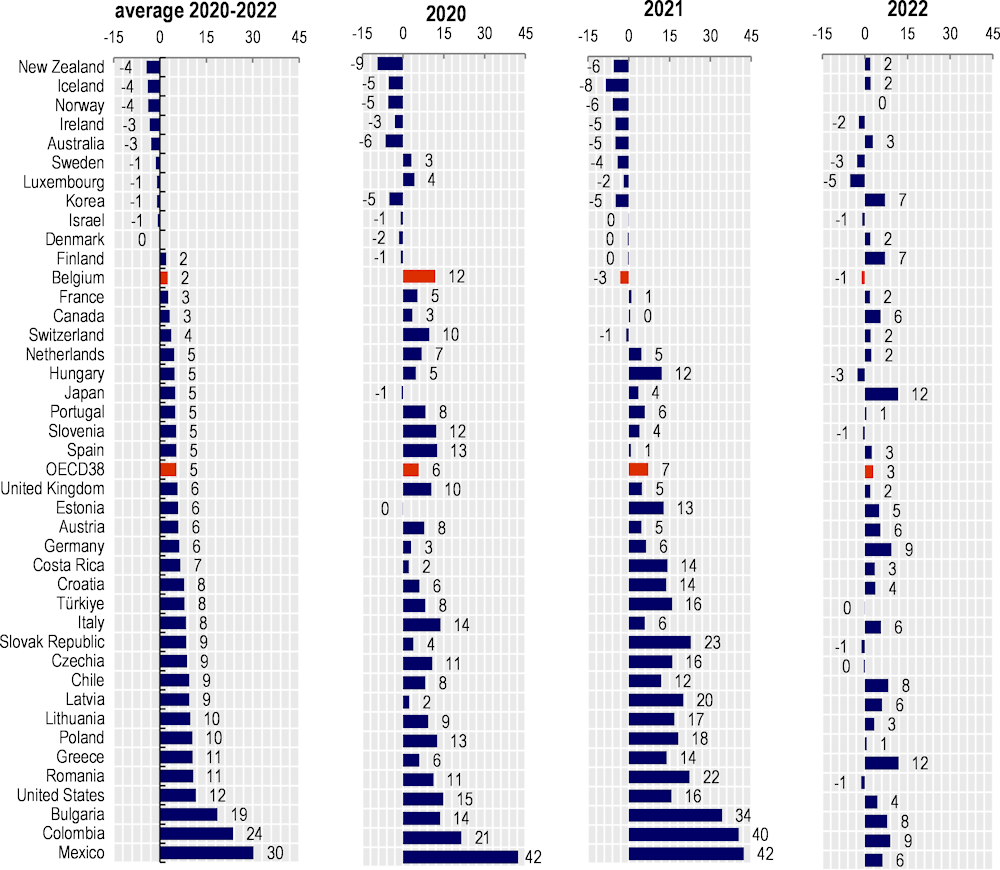

Based on OECD estimates, the overall increase in mortality in Belgium for the period from 2020 to 2022 was below the OECD average, and lower than in its neighbouring countries of France, Germany, Netherlands, but higher than in Luxembourg (Figure 4.2) (OECD, 2022[11]; Morgan et al., 2023[12]). However, a closer examination throughout the different stages of the pandemic reveals great variation across the years, with a particularly high increase in mortality in Belgium in 2020, but lower than historical rates in both 2021 and 2022. The intensity of the first two COVID-19 waves in 2020 in Belgium led to a sharp increase in the number of deaths in 2020, with the mortality rate in 2020 (adjusted for population change1) being 11.8% higher compared to the pre-pandemic years (2015-2019), and more than twice that of the OECD average of 5.8%. In 2020, Belgium had the 9th highest excess mortality in the OECD, performing more poorly than all of its neighboring countries. However, following the sharp increase in 2020, mortality was 3.2% lower in 2021 and 1.2% lower in 2022 compared to the pre-pandemic years.

In Belgium’s neighbouring countries, the pattern over the pandemic years was mixed. Luxembourg experienced a pattern that was similar to that of Belgium, with higher mortality in 2020 but a lower mortality rate in both 2021 and 2022, compared to its 2015-2019 average. France and the Netherlands experienced their highest increases in mortality in 2020, but the rate remained higher than pre-pandemic years throughout the three years, and remained higher than pre-pandemic levels in 2021 and 2022. In Germany, the mortality rate was also above pre-pandemic levels throughout the three-year period, increasing in each year of the pandemic. Similar findings can be found for the impact of COVID-19 on life expectancy. Belgium and France recorded a reduction in life expectancy in the first year of the pandemic, and fully recovered in the following year, whereas Germany continued to see deteriorating life expectancy in 2021 compared to 2020 (Schöley et al., 2022[13]).

Within Belgium, all three regions experienced their highest increases in mortality in 2020. The mortality rate was 9.9% higher in Flanders, 13.8% higher in Wallonia, and 20.8% higher in Brussels in 2020, compared to their 2015-2019 averages. In contrast, mortality was lower across all three regions in 2021 (‑4.5% in Brussels, -3.4% in Wallonia, -2.8% in Flanders) and negative or effectively unchanged in 2022 (‑3.5% in Brussels, -2.2% in Wallonia, 0.3% in Flanders) compared to the 2015-2019 average.

It is important to reiterate that these estimates measure mortality patterns over annual and three-year periods. The continual tracking and dissemination of weekly data on deaths throughout the pandemic has shown that the variance is naturally of a much higher magnitude and that countries or regions may have experienced significant peaks in mortality that resulted in acute pressures on health systems and emergency services. The examination of average annual mortality rates does not reveal the variation in mortality on a weekly basis and the impact on health systems and society at specific times.

Figure 4.2. Change in the mortality rate for 2020-22 (compared to the period 2015-19), %

Age-standardised mortality rates (ASMR)

Note: Data refer to the age-standardised mortality rate (ASMR) method using 2015 OECD population structure. The bars represent the annual excess mortality for the average of 2020-2022 and for each of the years indicated compared to 2015-2019. Data are sorted based on increasing excess mortality for the average 2020-2022.

Source: Morgan, D., et al. (2023[12]), “Examining recent mortality trends: The impact of demographic change”, OECD Health Working Papers, No. 163, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/78f69783-en.

4.1.3. Like in other countries, older populations in Belgium made up the vast majority of COVID-19-related mortality

COVID-19 incidence rates and mortality were unevenly distributed. Older populations and people in nursing homes were disproportionally affected. Of the nearly 31 000 COVID-19-related deaths recorded in Belgium between the start of the pandemic and March 2022, 92% occurred among people aged 65 and above, with nearly half of all deaths affecting the population aged 85 and older (Sciensano, 2023[5]). While the uptake of COVID-19 vaccines dramatically reduced the death rate from the virus, including among older populations (who have recorded some of the highest levels of COVID-19 vaccination), the proportion of all COVID-19-related deaths impacting older populations has not changed substantially over the course of the pandemic. Indeed, 90% of deaths that occurred in the first quarter of 2022 took place among people 65 and older, including 46% among those 85 and above, compared to 92% and 48%, respectively, over the course of 2020 and 2021 (Sciensano, 2023[5]).

The proportion of deaths occurring in nursing homes and among nursing home residents was particularly severe during the first two waves of the pandemic. Between March 2020 and September 2022, nearly one-third (32%) of all COVID-19-related deaths in Belgium occurred in nursing homes, with nearly one in two (45%) deaths occurring among residents of nursing homes, irrespective of their place of death (Jurcevic et al., 2023[4]). In 2020, more than two in five (43%) deaths from COVID-19 occurred in nursing homes, and nursing home residents made up nearly three-fifths (57%) of all COVID-19 deaths. While nursing home residents continue to make up a significant proportion of COVID-19 deaths, the proportion of all COVID-19 deaths occurring among nursing home residents fell to 24% and 31% in 2021 and 2022, respectively (Jurcevic et al., 2023[4]). This distribution of COVID-19-related deaths, particularly during the first two waves of the pandemic, indicates a challenging and in some cases suboptimal response in long-term care facilities.

Mortality rates among residents of nursing homes in Belgium have previously been reported to be the highest among OECD countries (Rocard, Sillitti and Llena-Nozal, 2021[14]). The difference in recording COVID-19 mortality between Belgium and other OECD countries makes it difficult to evaluate the extent to which long-term care facilities in Belgium were disproportionately hit compared to other OECD countries.

At more than 67 beds per 1 000 people aged 65 and above, Belgium has one of the highest numbers of long-term care beds in facilities and hospitals across the OECD. The number of long-term care beds per capita is well above the OECD average of 45.6 beds per 1 000 people aged 65 and above, and higher than all but Luxembourg and the Netherlands (OECD, 2023[15]). The fact that a comparatively higher proportion of Belgium’s older residents live in nursing homes compared to many other OECD countries has meant that the impact of poor infection control and preparedness in nursing homes – a very serious situation in Belgium during the pandemic, but not unique to the country – has had a disproportionate impact compared to many other countries.

4.1.4. Other vulnerable groups, including people of low socio-economic status and certain ethnic and professional groups, were particularly hard-hit

Across OECD countries, the COVID-19 pandemic has affected certain socio-economic, ethnic, and professional groups particularly hard (McGowan and Bambra, 2022[16]; Aburto et al., 2022[17]; Berchet, Bijlholt and Ando, 2023[18]). These findings were no different in Belgium. A study using linked data from the Belgian National Register found that during the first months of the pandemic, excess mortality was particularly high among immigrant men of Sub-Saharan African descent, with higher mortality among older men of migrant backgrounds, compared with native-born Belgians (Vanthomme et al., 2021[19]).

Higher incidence and mortality rates were also recorded among people from a lower socio-economic background. Between March 2020 and June 2021, the incidence rate of confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Belgium between March 2020 and June 2021 was 24% higher in the most deprived areas than in the least deprived ones (Meurisse et al., 2022[20]). In line with that, a study using linked Belgian administrative data demonstrated that in the first wave of the pandemic, excess mortality among people in the lowest income decile was more than twice that of people in the highest income decile (Decoster, Minten and Spinnewijn, 2021[21]).

Similar patterns of high incidence and mortality rates among people with lower incomes, those living in more deprived areas, and ethnic minorities have been found in other OECD countries. An OECD review of evidence related to COVID-19 outcomes among disadvantaged and vulnerable groups found that the risk of dying from COVID-19 was 40-60% higher among those in the lowest income groups in Canada, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Sweden compared to those in the highest income groups (Berchet, Bijlholt and Ando, 2023[18]). However, differences in study methodologies, designs, and the time periods covered across analyses complicate direct comparisons of the differential impacts of COVID-19 by different categories of vulnerability (Berchet, Bijlholt and Ando, 2023[18]).

Certain professions have also been found to have experienced higher incidence of COVID-19 compared with other professions (Verbeeck et al., 2021[22]). This reflects the reduced abilities of certain professional groups to comply with certain non-pharmacological interventions that can help to reduce infection rates, particularly of those requiring close personal interaction, such as health professionals and employees in the transportation and hospitality sectors (Verbeeck et al., 2021[22]).

4.1.5. Long COVID continues to impact an important number of Belgians

More than three years into the pandemic, long COVID continues to impact the daily lives of a non-negligible proportion of people who are infected with COVID-19. In Belgium, health authorities have launched many initiatives intended to better understand the prevalence and impact of long COVID. Overall, these studies find that long COVID has serious impacts on well-being and quality of life for a significant proportion of people experiencing long COVID symptoms.

Sciensano, the national public health institute of Belgium, launched the COVIMPACT project in April 2021. The project ran for two years and followed a cohort of patients in Belgium who had been infected with COVID-19 to evaluate the long-term impacts – in terms of mental health, social well-being, and physical health – of COVID-19 and explore what determinants may impact better or worse long-term outcomes (Sciensano, 2023[23]). Results from the study found that nearly half (47%) of all participants continued to have at least one symptom related to their initial COVID-19 infection after three months, with close to one-third (32%) of participants reporting they had at least one symptom six months after their initial infection (Smith et al., 2022[24]). About one-fifth of respondents reported having received a formal diagnosis of long COVID from a healthcare professional (21% after 3 months, 22% after 6 months) (Smith et al., 2022[24]).

While a high proportion of respondents reported having at least one symptom at least three months following their initial COVID-19 infection, many also reported that they felt they had broadly recovered from COVID-19. At both three and six months post infection, fewer than 10% of respondents reported that they had either not at all recovered from COVID-19 or had not recovered very much, with just 3% of respondents reported that they felt they had not recovered at all (Smith et al., 2022[24]).

Surveys of patients in Belgium have further underscored the potential financial and employment impact of long COVID. In a Federal Health Care Knowledge Centre (Federaal Kenniscentrum voor de Gezondheidszorg / Centre Fédéral d’Expertise des Soins de Santé (KCE)) survey of long COVID patients, three-fifths of patients reported that they had an incapacity to work following their COVID-19 infection, with just one-third of respondents reporting that they had returned to work as usual at the time of the survey (Castanares-Zapatero et al., 2021[25]). More than one quarter (26%) of respondents had returned to work, but at fewer hours than they had worked prior to their infection, while nearly two-fifths (38%) reported not having returned to work at all due to their health problems (Castanares-Zapatero et al., 2021[25]). Some 37% of respondents experienced negative financial consequences due to their condition, with the impact due to reductions in employment, medical expenses, or a combination of these factors representing the major drivers of financial loss associated with long COVID (Castanares-Zapatero et al., 2021[25]).

Patients with long COVID experience a wide range of symptoms, meaning the care they need to help treat the condition is not always straightforward and can require services from a range of healthcare settings and professionals. In the KCE survey, co-ordination of care around long COVID was found to be poor, with an insufficiently integrated and multidisciplinary approach hampering patient-centred care (Castanares-Zapatero et al., 2021[25]). Moreover, reimbursement limits set by the national social security system – such as a maximum of 18 physiotherapy services reimbursed per year – were found to be insufficient to address the ongoing long COVID care needs of some patients (Institut national d'assurance maladie-invalidité, 2022[26]).

Through March 2022, patients with long COVID had access to care services through established reimbursement schemes, but no specialised services or care pathways were reimbursed for long COVID (Castanares-Zapatero et al., 2021[25]). While these previous agreements likely covered a certain proportion of the care needed for long COVID and the majority of long COVID patients surveyed in the KCE survey responded being satisfied in their interactions with the health system, a comprehensive, holistic diagnostic work-up for long COVID was found to be lacking, with patients sometimes experiencing delays in proper referrals as a result (Castanares-Zapatero et al., 2021[25]).

To improve the health system’s response to caring for people with long COVID, notably around the co-ordination of care, the National Institute for Health and Disability Insurance (Institut national d’assurance maladie-invalidité / Rijksinstituut voor ziekte- en invaliditeitsverzekering (INAMI-RIZIV)) began reimbursing services for personalised long COVID care pathways in July 2022. Reimbursements cover services that would not have been covered by existing reimbursement agreements. To be eligible, patients must have a formal diagnosis of long COVID from a general practitioner, a minimum of 12 weeks after an initial COVID-19 infection (Institut national d'assurance maladie-invalidité, 2022[26]). Policy changes to support the continuity of long COVID care were introduced earlier in some countries. In the United Kingdom, for example, NHS England launched an enhanced service specification to improve long COVID assessment and care in primary care beginning in June 2021 (NHS England, 2021[27]).

Going forward, it will be important to monitor the potential impacts of long COVID and other long-term health impacts of the pandemic to better understand their impact on the daily and working lives of people as well as the response needed from the health system. Few countries have monitored the potential prevalence of long COVID systematically on a population level. Regular household surveys in the United States (the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey) and the United Kingdom (through the Office of National Statistics UK Coronavirus Infection Survey) stand out as examples of regular measurement of self-reported long COVID and its impacts on daily life. Belgium should consider how it can make use of its extensive data infrastructure, including data from the Crossroads Bank for Social Security, to monitor any changes to the health status of its population and to the impacts it may have on socioeconomic outcomes and the labour market.

4.2. What indirect impacts did COVID-19 have on health in Belgium?

4.2.1. The pandemic took a significant toll on mental health in Belgium

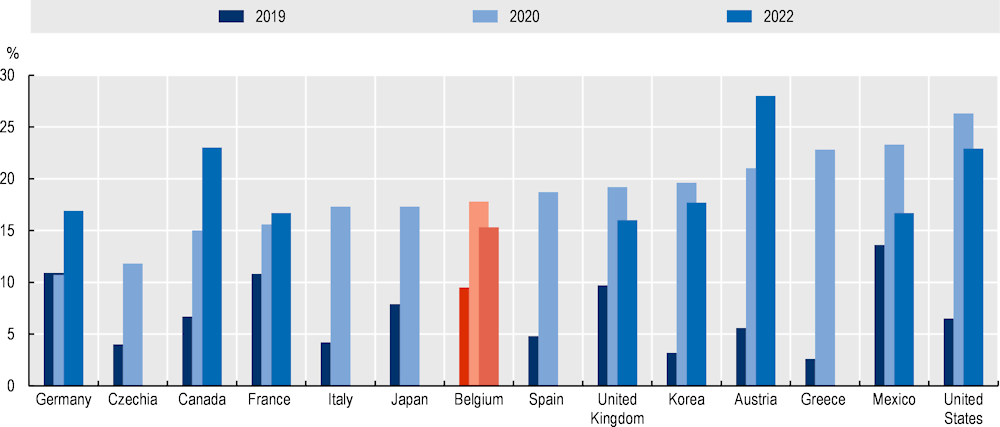

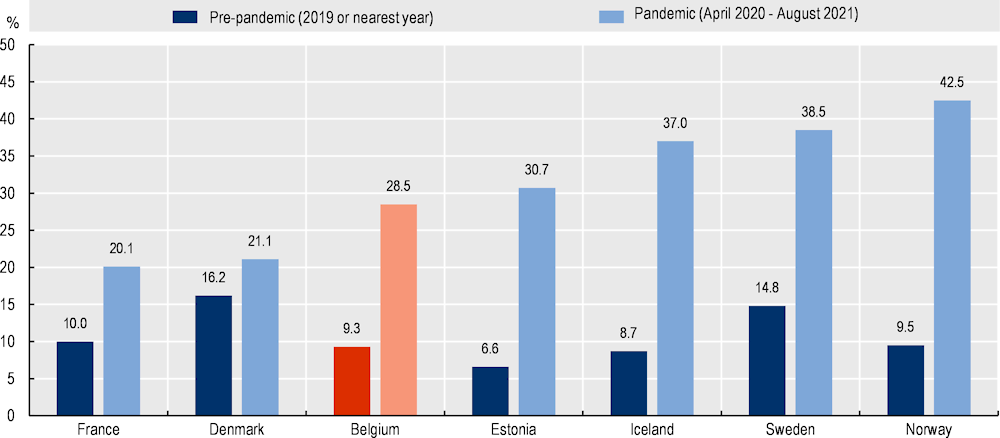

Across the 14 OECD countries with available data, the COVID-19 pandemic led to substantial increases in the prevalence of self-reported poor mental health, with the proportion of the population reporting symptoms of anxiety and depression doubling in a number of countries (Figure 4.3) (OECD, 2023[15]). In Belgium, the prevalence of both self-reported depression and anxiety almost doubled between 2019 and 2020, with 18% of survey respondents reporting symptoms of depression and 20% reporting symptoms of anxiety, in 2020, up from about 1 in 10 in 2019. While self-reported anxiety and depression fell in 2022 compared to 2020, they remain above pre-pandemic levels, with 15% of respondents reporting symptoms of depression and 17% symptoms of anxiety in 2022 (OECD, 2023[15]). Prevalence estimates may be affected by data reporting factors such as more and more sympathetic discussion of mental health in the media contributing to a greater willingness to disclose mental health concerns, or a higher likelihood of disclosing mental health concerns in online self-reporting compared to in-person (Moron, Irimata and Parker, 2023[28]). Nonetheless, a worsening of mental health status especially during the most acute phases of the pandemic, particularly for already-vulnerable groups such as those with low incomes, unemployed persons, or young people, was a pattern seen across OECD countries (Daly, Sutin and Robinson, 2020[29]; Bruggeman et al., 2022[30]; Moulin et al., 2023[31]; OECD, 2021[32]).

Figure 4.3. National estimates of prevalence of depression or symptoms of depression, 2019-22 (or nearest year)

Notes: Survey instruments and population samples differ between countries and in some cases across years within countries, which limits direct comparability. Pre-pandemic data for Czechia is from 2017; Canada from 2015-19; Japan from 2013; Belgium from 2018; United Kingdom from 2019-March 2020; and Korea from 2016-19.

Source: OECD (2023[33]), OECD Health Statistics 2023.

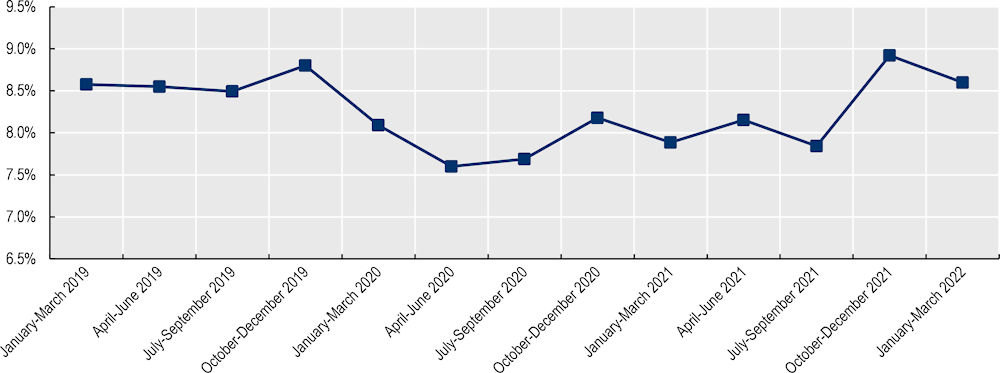

The utilisation of medicines related to mental health treatment appears to have fallen during the pandemic. Compared to the previous year, antidepressant prescriptions fell at the start of 2020 and remained lower than prior to the pandemic into 2021 (Figure 4.4).

Figure 4.4. Average monthly percentage of adults who purchased a prescribed antidepressant over the last 3 months

Note: Unweighted three-month averages calculated based on monthly data.

Source: L’Agence InterMutualiste (2023[34]), ATLAS IMA website.

Data from primary care in Flanders suggests that the distribution of care for mental health conditions also changed over the pandemic period. Overall, general practitioners provided more mental healthcare over the course of 2000 and 2021 than prior to the pandemic, with the volume of registrations for mental healthcare rising by nearly 9% in 2020 and 40% in 2021, compared with the 2018-2019 period (Vandamme et al., 2023[35]). While care increased for depression and anxiety, care for other important mental health conditions – such as eating disorders and care for substance abuse problems – fell in primary care over the course of the pandemic and had not recovered by the end of 2021 (Vandamme et al., 2023[35]).

Relatively early on in the pandemic, regional authorities adopted measures to strengthen the provision and continuity of mental healthcare. Walloon health authorities increased the mental health workforce during the pandemic by funding an additional 189 full-time positions to strengthen outpatient mental health services, as well as services related to suicide prevention, palliative care and mental health support for care workers and those living in long-term care facilities (OECD, 2023[36]). Brussels scaled up mental health services targeted at specific populations, creating a temporary telephone hotline to provide psychological support to caregivers, increasing the number of child and youth front-line mental health teams, and increasing outreach in outpatient mental healthcare, including outreach for vulnerable groups (OECD, 2023[36]). The region also scaled up the number of lieux de liens – places of connection – community centres that are accessible to people with psychiatric and psychological conditions, but which operate outside of the formal mental health system (Lasserre and Misson, 2021[37]; OECD, 2023[36]).

Ongoing health reforms undertaken by authorities, including at the federal level through the Interministerial Conference on Public Health, aim to ensure the continuity of mental healthcare and expand access to psychosocial services for those who newly needed them. These reforms built on efforts already underway prior to the pandemic to strengthen the access and affordability of primary mental healthcare services, and include EUR 112.5 million in additional funding earmarked to strengthen primary mental healthcare (Healthy Belgium, 2023[38]). Reforms to the mental health system intended to strengthen first-line mental health services were based on the existing 32 mental healthcare networks, each covering specific regions and targeting both adult and child and adolescent mental health services. In particular, the reforms were aimed at helping to improve prevention and early detection, as well as to identify vulnerable groups and consider broader socioeconomic factors that could contribute to poor mental health (Office of Frank Vandenbroucke, 2022[39]). Beginning in September 2021, access to mental health services were expanded to include up to 20 visits with a psychologist for the out-of-pocket cost of EUR 11 per session (EUR 4 per session for those entitled to supplemented refunds), or EUR 2.50 per session for group therapy.

Funding was also earmarked to support specific populations and mental health outreach efforts related to the pandemic, including EUR 1.5 million to support mental health support for students, EUR 4.7 million to strengthen mobile crisis teams targeting children and adolescents, and EUR 55.5 million to support self-employed adults, including free psychological care (Healthy Belgium, 2023[38]).

4.2.2. Certain vulnerable and professional groups were at higher risk of poor mental health and reduced access to mental health services during the pandemic

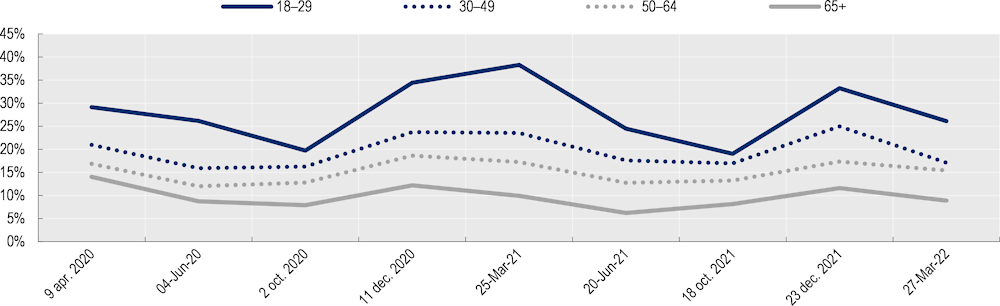

In addition to youth and young adults, people with disabilities, residents of nursing homes, people with low social support, and those with a lower prevalence of meaningful activities, including employment, were found to be at higher risk of poor mental health such as anxiety and depression during the pandemic (Bruggeman et al., 2022[30]; Godderis, 2021[40]). The disproportionate impact of the pandemic on poor mental health among young people has been identified as a major health outcome of the pandemic across countries, and Belgium is no exception. Across all waves of the BELHEALTH Cohort Surveys conducted during the pandemic, the youngest adults (age 18-29) reported the highest prevalence of depressive symptoms, with the oldest adults (age 65+) consistently reporting the lowest prevalence of symptoms of depression (Figure 4.5).

Figure 4.5. Percentage of adults with a depressive disorder (according to PHQ-9), by age group

Note: The PHQ-9 is a self‐administered questionnaire which scores each of the 9 DSM‐IV criteria for depression as “0” (not at all) to “3” (nearly every day). This scale includes a Major depressive syndrome (total sum of all items > 4 and the item “Little interest or pleasure in doing things” or “Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless” >1) and Other depressive syndrome as well (total sum of all items between 1 and 5 and the item “Little interest or pleasure in doing things” or “Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless” >1). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0163834313001278

Source: Sciensano (2023[41]), Sciensano Belgium COVID-19 Epidemiological Situation Mental Health Studies (database).

The mental health impact of the pandemic on young people in Belgium reflects the experience of young adults in a number of OECD countries. Across seven OECD countries with available data, the share of young people with symptoms of depression increased everywhere in 2020-2021 compared with 2019, more than doubling in all but one country, including in Belgium.

Figure 4.6. Share of young people with symptoms of depression

Note: Given the prevalence of symptoms of depression has fluctuated within countries over the course of the pandemic, prevalence estimates are pooled from longitudinal or repeated cross-sectional surveys within countries up to 12 August 2021. However, not all surveys are representative and the number and timing of surveys has varied across countries which hampers cross-country comparability. Symptoms of depression have been measured using PHQ-8 and PHQ-9 in all countries except France and Estonia. Some pre-pandemic and pandemic data are not strictly comparable due to differences in scoring methods, which could understate the increase in symptoms to some extent. Symptoms of depression in France during the pandemic have been measured using HADS-D which could lead to lower estimates of the share of young people with symptoms of depression compared to other countries using PHQ-8 and PHQ-9.

Source: OECD/European Union (2022[42]). Health at a Glance: Europe 2022: State of Health in the EU Cycle, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/507433b0-en.

Data on hospital admissions and waiting times for child psychiatric services further suggests that the relatively higher mental health toll of the pandemic on young adults also applies to children and adolescents. In Flanders, waiting times for residential care for eating disorders were reported to be four times as high in October 2021 as they had been prior to the pandemic (Godderis, 2021[40]). Both outpatient and residential child psychiatry services were also reported to have been heavily oversubscribed, with two to three month waiting times for child psychiatric appointments and hospitalisations, and a shortage of child psychiatric beds (Godderis, 2021[40]).

The well-being and mental health of the healthcare workforce was also strongly impacted during the pandemic. Results from the OECD Survey of General Practitioners indicated that of the 17% of survey respondents who reported seeking mental health support during the pandemic, four-fifths (81%) had not previously sought mental health support prior to the pandemic, or had not received mental health support for a long time prior to the pandemic (OECD, 2023[43]). Across Belgium, more than three-fifths of general practitioners (hereafter, GP) respondents to the PRICOV-19 study, conducted during the pandemic, reported that they had felt burned out from their work during the past month, with the proportion of general practitioners at risk of distress (based on the Mayo Clinic scale) rising by 15% in comparison to before the pandemic, from 60% to 69% (Fomenko, 2023[44]). Another large-scale study of nurses during the first COVID-19 peak in Belgium found that 70% were at risk of burnout (Khan, Bruyneel and Smith, 2022[45]).

4.2.3. The COVID-19 pandemic led to disruptions in routine care

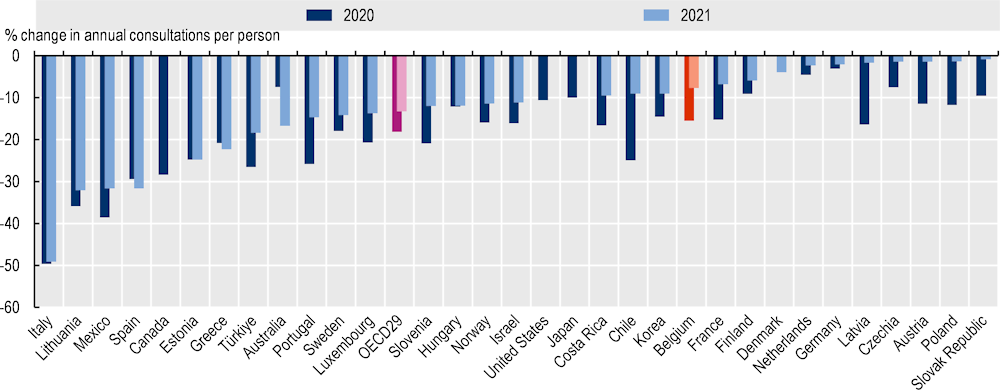

Making space for the needs of COVID-19 patients led to delays and postponements in care across the health system. As the scale of the pandemic became clearer, health authorities moved to free up space in hospitals and the health sector in part by postponing and delaying routine and elective care to the greatest extent possible, beginning in March 2020. This approach – which was broadly adopted across OECD countries – led to a decline in the number of physician consultations, particularly during the initial waves of the pandemic, with the number of consultations for many specialties remaining below pre-pandemic (2019) levels at the end of 2021.

Compared with other OECD countries for which data was available, the drop in consultations in Belgium following the onset of the pandemic was relatively modest (Figure 4.7). Consultations fell by 15.5% in 2020 compared to 2019 and by 7.7% in 2021 compared with 2019. In comparison, the average number of in-person consultations dropped by 18.1% across 28 OECD countries on average in 2020, and by 13.2% in 2021 compared to 2019. The reduction was smaller in Germany (-3.1% in 2020, -2.0% in 2021) and the Netherlands (-4.5% in 2020, -2.3% in 2021), roughly similar in France (-15.3% in 2020, -6.8% in 2021), and slightly more severe in Luxembourg, especially in 2020 (-20.7% in 2020, -13.7% in 2021).

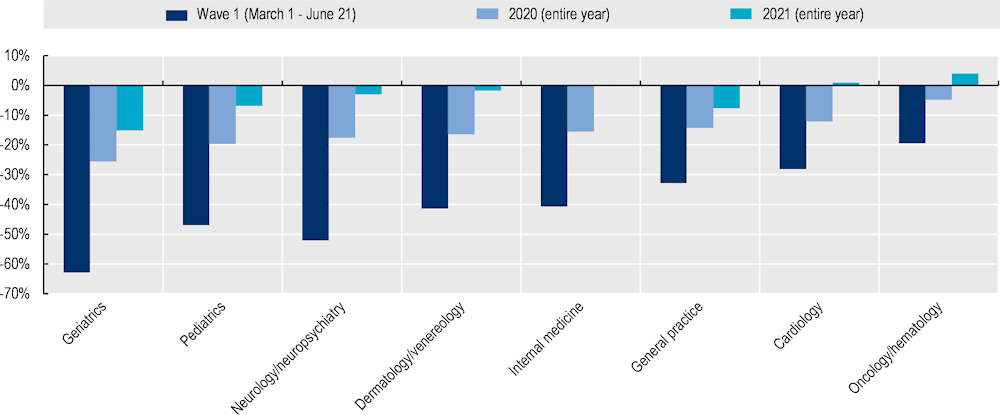

Figure 4.7. Percentage change in number of in-person doctor consultations compared to 2019

Looking at more disaggregated data available for Belgium, between 2019 and 2020, the number of consultations fell across a range of specialties, with a particularly large decline recorded during the first wave of the pandemic. Geriatric consultations, which experienced the biggest fall during the first wave (a 63%-decrease compared to the same period in 2019), also recorded the biggest fall over the course of the entire year in 2020 and remained 15% lower than pre-pandemic levels through 2021. In contrast, both cardiology and oncology fell in 2020 – by 12% and 5%, respectively – but recorded increases in the number of consultations in 2021 compared to 2019 (1% and 4%).

Figure 4.8. Percentage change in number of doctor consultations compared to 2019

Note: Year refers to December of the previous year – November of the referenced year. For wave 1, estimates based on assumption that consultations are evenly distributed across the month.

Source: INAMI (2022[46]), Monitoring COVID-19: L'impact de la COVID-19 sur le remboursement des soins de santé, https://www.inami.fgov.be/SiteCollectionDocuments/monitoring_COVID19_update_fevrier_2022.pdf.

The activation of emergency plans and measures taken to make space for COVID-19 patients in hospitals by the Hospital Transport and Surge Capacity Committee (HTSC), the advisory body set up to manage hospital and transport control measures during the pandemic, led to reductions in hospitalisations for routine and elective services. During the first and second waves of the pandemic in Belgium, the total number of hospital stays fell to 52% and 75% of the median of the four years prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, respectively (FPS Public Health, 2023[47]). Surgical day hospitalisations fell the most: during the first wave, the number of hospitalisations for ambulatory surgeries fell to 11% of the previous four-year median (FPS Public Health, 2023[47]). Some routine surgeries, including hip replacements and total knee replacements, fell in the first year of the pandemic compared to pre-pandemic levels. Total knee replacements, for example, fell by 55% in Belgium between 2019 and 2020 – more than twice the OECD average reduction of 23%, and higher than neighbouring France (-28%), Germany (-12%), and Luxembourg (-31%) – and remained 23% below their 2019 levels in 2021. Hip replacements similarly fell during the pandemic, by 19% in 2020 compared to 2019, and remained below pre-pandemic levels into 2021 (OECD, 2023[33]). Despite these drops, however, hip and total knee replacements in Belgium remain well above the OECD average, with 271 hip replacements performed per 100 000 population in 2021 (compared to 172 on average across 33 OECD countries), and 164 total knee replacements per 100 000 population in 2021 (compared to 119 across 32 OECD countries) (OECD, 2023[15]).

4.2.4. Some declines in cancer screening and diagnosis were reported in Belgium

As in other OECD countries, Belgium experienced declines in the number of new cancer diagnoses made during the pandemic. Diagnoses for breast and colorectal cancers plummeted during the first wave of the pandemic, with breast cancer diagnoses among women in the age group for screening (aged 50-69) falling by 56% in April 2020 compared with April 2019, and colorectal cancer diagnoses for men and women in the screening age group (aged 50-74) falling by 54% over the same period (Belgian Cancer Registry, 2022[48]). While still slightly below 2019 levels, diagnosis rates have largely recovered over the course of the pandemic, with breast cancer diagnosis among women of screening age being 2% lower between January 2020-December 2021 compared with the previous period, and colorectal cancer diagnosis among people of screening age being 8% lower (-10% among men and -5% among women) (Belgian Cancer Registry, 2022[48]). Overall, the Belgian Cancer Registry has estimated that about 2 700 diagnoses of cancer were missing over the first two years of the pandemic (Belgian Cancer Registry, 2022[48]).

The decline in screening rates and cancer diagnoses across many countries over the course of the pandemic has led to concerns about the implications of delayed diagnosis and treatment for the stage at diagnosis and ultimately mortality. There is some evidence to suggest that the delays in cancer diagnoses have more negative impacts on cancers that progress more quickly, such as head and neck cancer. The incidence of head and neck cancers in Belgium was nearly 10% (9.5%) lower in 2020 than what would have been predicted based on the trend from 2017-2019, but with an increased stage at diagnosis among both men and women for oropharynx and larynx tumours, though not all head and neck tumours overall (Peacock et al., 2023[49]).

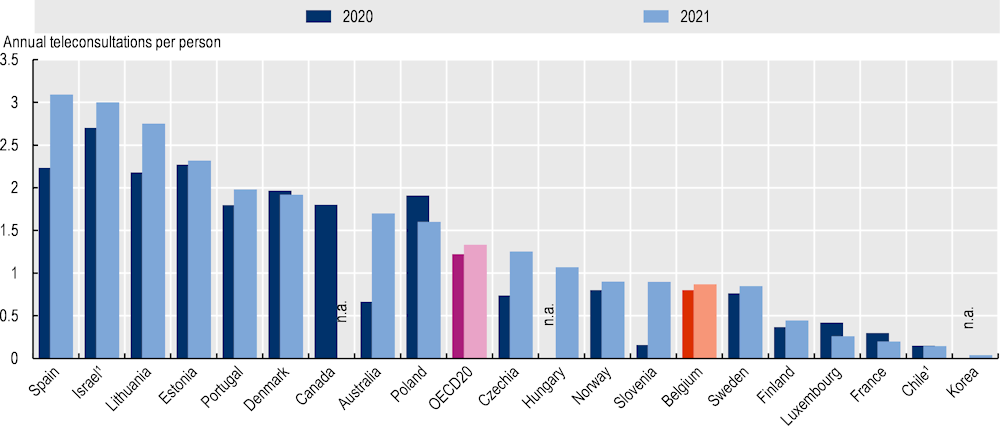

4.2.5. Belgium introduced teleconsultations to help ensure access to care, but uptake remains below that of other OECD countries

As in many countries, the scale-up of telemedicine served as a crucial tool to maintain a measure of access to, and continuity of, care during the pandemic. In Belgium, reimbursement for teleconsultation services was adopted at the beginning of March 2020. Prior to the pandemic, no reimbursements were possible for remote consultations. Starting from 14 March, the INAMI-RIZIV approved three new billing codes for physicians providing remote medical services – by telephone and with or without video – to support both COVID-19-related triage (code 101990), COVID-19 care and triage organised by general practitioners (code 101835), as well as continuity of care (code 101135). For all three types of care, physicians billed health insurers EUR 20, with no additional charges or fees for the patient (Institut national d'assurance maladie-invalidité, 2022[50]).

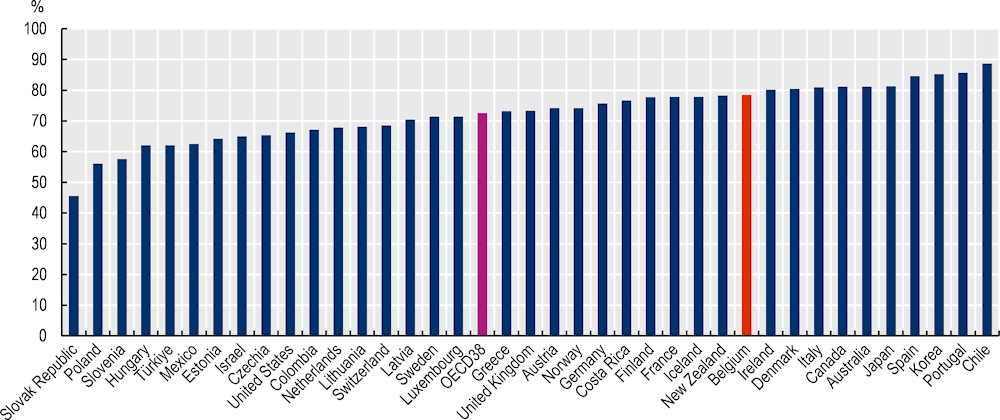

In addition to making teleconsultations available for non-COVID-19 related continuity of care, many COVID-19 patients also received telemedical services to monitor the progression of their illness. Nonetheless, while access to teleconsultation services increased compared to prior to the pandemic (when such care was not reimbursed), the take-up of telemedicine in Belgium remained comparatively low, averaging just 0.8 consultations per capita in 2020 and 0.9 per capita in 2021, lower than the OECD average of 1.2 consultations per person in 2020 and 1.3 consultations in 2021 (Figure 4.9). The share of teleconsultations as a proportion of overall doctor consultations is also lower than in other OECD countries. In 2021, teleconsultations made up 11% of overall consultations, compared with 19% on average across 20 OECD countries (OECD, 2023[15]).

Figure 4.9. Doctor teleconsultations per person, 2020 and 2021 (or nearest year)

The results of a survey conducted by the INAMI-RIZIV following the first six months of their COVID-19 telemedicine reimbursement policy found that the majority of teleconsultations were conducted with a general practitioner (78%), with specialists representing 11% of remote consultations and mental health specialists (psychiatrists and psychologists) representing a further 7% of remote consultations (CIN-NIC, 2020[51]). Notably, patients were far more likely to report that specialists and mental health professionals (psychiatrists and psychologists) had taken the initiative to organise the teleconsultation than the patients themselves, with the majority of patients reporting that teleconsultations replaced a specialist or mental health appointment planned in advance. In contrast, nearly three-quarters of appointments with general practitioners were not organised as a replacement for a previously organised consultation (CIN-NIC, 2020[51]).

An analysis of the use of teleconsultations during the first year of the pandemic suggests that access to telemedicine and teleconsultations was fairly evenly distributed across the population. Throughout the year, the proportion of the population accessing telemedical services was largely similar between people living in regions considered to be among the poorest quartile, compared with those living in the wealthiest quartile regions (Vrancken et al., 2022[52]). For the majority of the year, access to telemedicine services was slightly higher among people living in the poorest quartile regions (Vrancken et al., 2022[52]). While this may in part be related to a comparatively higher risk of poor health and COVID-19, the lack of a significant difference in access to telemedicine services suggests that overall, full reimbursement from the INAMI-RIZIV and the ability to engage in teleconsultations with and without video may have helped to address some challenges of the digital divide.

4.3. How effective was the health response to the pandemic in Belgium?

4.3.1. The complex governance and crisis response structures of Belgium complicated the initial pandemic response

Belgium activated the “federal phase” of its crisis management system on 12 March 2020 (see Chapter 3). While the emergency nature of the pandemic was understood, the response to the pandemic in the initial months was complicated by some lack of institutional and personal leadership, as well as the complexity and number of structures set up to co-ordinate the response. Two major bodies responsible for managing the crisis – the National Crisis Center (NCCN) and the Federal Public Service Public Health (hereafter, FPS Public Health) – did not have a strong leadership role from the onset of pandemic. In many cases, the crisis structures set up by NCCN were bypassed in favour of ad hoc bodies formed to address the pandemic, while a lack of familiarity between NCCN and the public health community further complicated its ability to lead. In the FPS Public Health, its main advisory body, the Risk Management Group (RMG), grew to a size that made it difficult to issue advice, and became instead largely a forum for discussion and debate. Moreover, the crisis management capacity within the FPS Public Health was limited, with the existing unit focused primarily on emergency response, rather than risk anticipation and preparedness. Some of these co-ordination challenges were alleviated by the creation of the COVID Commissariat in October 2020. Ensuring crisis management capacities in the FPS Public Health are strengthened will be essential for addressing future health emergencies.

4.3.2. Belgium encountered a severe shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE) in the first weeks of the pandemic.

The destruction of the federal strategic stockpile (see Chapter 2) and fragmented competencies for emergency stocks meant that many key sectors faced acute PPE shortages at the start of the pandemic. In the initial weeks, similar to most OECD countries, Belgium encountered a severe shortage of PPE, such as masks, gowns, and other protective gear across all sectors. Indeed, Belgium’s strategic stock of PPE had expired prior to the pandemic, was subsequently destroyed, and had not been replaced at the onset of the pandemic.

Healthcare providers received PPE from different sources, which reflects the governance structure of the country. Hospitals are largely a federal competency. Subsequently, the federal level was in charge of providing PPE to hospitals. It set up a joint Task Force in mid-March 2020 to take an inventory of PPE and to alleviate the shortage, for example by confiscating existing mask stocks, by procuring masks on the national and international market, and by restricting the sale of masks and other PPE to individuals with a prescription from a healthcare professional. The federal government also procured masks from Doctors Without Borders (Médecins sans frontières). Long-term care facilities, on the other hand, are a competency of federated entities, and thus received PPE from the subnational governments. They reported encountering substantial difficulties sourcing PPE at the start of the pandemic. While creating a task force charged with co-ordinating the pandemic response in long-term care facilities was briefly considered, concerns related to overstepping competencies meant that the idea was quickly abandoned. In general, efforts to procure and equip providers with PPE were hampered by debates on how competencies are divided among different government levels in the first weeks.

The situation across regions was very heterogeneous and depended on the success of each regional authority to procure PPE, as well as long-term facilities’ own connections with local hospitals. When the sub-national entities learned in March that the strategic stock had been destroyed, they tried to procure masks on the international market themselves. For example, the German-speaking Community successfully procured masks from German manufacturers in the early phase of the pandemic, and also built its own storage facility and network. Providers in that part of the country could post an order on a weekly basis. The Brussels-Capital region organised and received PPE from NGOs, such as Doctors of the World (Médecins du Monde). In the Flanders region, nursing homes with ties to hospitals or first-line structures sometimes received masks through these networks. Efforts to engage with national manufacturers such as the clothing industry to produce masks were of limited success, for example due to shortages in supply material. Health providers also reused masks, for example by alternating masks in weekly turns, and improvised using alternative devices, such as diving gear (OECD, 2023[53]).

Assessments of providers on the availability of PPE suggest that shortages were most acute in the initial two waves of the pandemic. In August 2020, an observational study of Belgian GPs found that a quarter of GPs still faced major shortages of FFP2 masks (Vaes et al., 2022[54]). Survey responses from the OECD Survey of General Practitioners in Belgium indicated that of the 64% (264) of GPs who reported experiencing PPE shortages in their practice, 96% (254) experienced shortages during the first wave and 19% (49) during the second wave (OECD, 2023[43]). In contrast, just 3% reported shortages in the third wave, while a further 3% reported that shortages lasted throughout the pandemic (OECD, 2023[43]). All responding hospitals in the OECD Survey of Hospitals reported experiencing shortages of PPE (n=27), with three facilities reporting that these shortages continued to be problematic throughout the pandemic (OECD, 2023[55]).

Belgium’s experience with severe shortages of PPE have underscored the importance of improving transparency on PPE procurement and stocks to facilitate the response, and to building strategic stockpiles for future crises. In the public procurement of PPE, well-functioning structures were largely absent at the beginning of the pandemic, leading to an insufficient preparedness in the first year. Belgium could learn from other OECD countries in developing more responsive systems for PPE allocation and distribution. Norway, for example, introduced a centralised system to report, allocate and distribute PPE (OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2021[56]). National authorities could trace PPE orders of municipalities via a web calculator (OECD, 2021[57]). This allowed Norway to monitor the demand and supply of PPE and helped to improve access for health providers. Similarly, Luxembourg set up a daily stock management to track the delivery and use of PPE of hospitals and care facilities on a daily basis (OECD, 2022[11]).

Belgium would have also benefitted from greater co-ordination capacity between the federal government and federated entities. Some countries have mandated the stockpile quantity by type of service. In Lithuania, for example, the national government has to uphold a stockpile for 60 days, and long-term care facilities for 30 days (OECD, 2021[57]). New regulations by federated entities requiring nursing homes to have a stock of PPE are a welcome development. Stockpiles should be assured for essential health and social care services, as well as relevant operators of critical infrastructure, regardless of whether they are the responsibility of the federal government or federated entities.

4.3.3. Many nursing homes lacked the appropriate information, supplies, and expertise to respond effectively to the COVID-19 pandemic

Residents of nursing homes were among the hardest hit during the pandemic, particularly during its initial waves, with a significant proportion of all COVID-19 mortality occurring in and among residents of nursing homes (see Section 4.1.3). With much of the initial pandemic response driven by images of the overwhelmed hospitals in Wuhan and in Northern Italy, planning for the pandemic was initially focused on preparing hospitals to respond – an understandable and necessary step, but one that may have contributed to comparatively less attention being given to other key sectors, including nursing homes.

While hospital capacity in Belgium remained relatively solid throughout the pandemic and age was not considered the leading factor in directives issued related to hospital transfers during the pandemic, data from the HTSC indicates that transfers from nursing homes were notably lower during the first wave of the pandemic than in the second wave during the fall and winter of 2020-2021 (Figure 4.10).

Figure 4.10. Sum of total transfers from nursing homes by week

As the pandemic spread quickly through nursing homes, the limited ability of many nursing homes to control the virus became clear. In many cases, while nursing homes had healthcare professionals – including nurses and doctors – on staff, facilities were designed as a living environment, rather than for infection control and management. Features such as communal living spaces and ventilation systems connected across multiple rooms severely complicated efforts to contain the spread of the virus once it had entered a facility. In response to the pandemic, a range of measures were implemented to strengthen infection control and limit outbreaks in long-term care facilities. These included:

The use of outbreak support teams: All federated entities employed mobile outbreak support teams to help support nursing homes experiencing clusters of cases or bigger outbreaks with infection control. In Brussels, for example, outbreak support teams comprised one doctor and three nurses, with teams created to support outbreaks among collective institutions (including nursing homes), schools, and homeless populations.

The development of other mobile teams for infection control and mental health support: In addition to teams that could support nursing homes in-person and at a distance in the context of outbreaks, mobile teams were deployed to reinforce knowledge on infection control, hygiene and isolation measures among health and care workers in long-term care facilities. Mobile teams also provided psychological support. In Wallonia, for example, the mobile psychological care support teams (SPAD) also provided support for first-line healthcare workers, including those working in care facilities, while in Flanders, mobile teams could actively help identify nursing homes’ employees who could benefit from psychological support. In Flanders, mobile teams visited three-quarters of the region’s nursing homes to provide information and training on PPE, hand hygiene, and provide general support.

The deployment of the military to provide additional personnel support: In cases where nursing homes were overwhelmed, support from the military and the Belgian Civil Protection was called in to provide additional personnel support. In Wallonia, for example, the Civil Protection was brought into nursing homes when clusters grew too large and exceeded 10 people.

During the crisis, all long-term care facilities were asked to report daily on the number of COVID-19 patients (suspected and confirmed) and COVID-19-related deaths that had occurred in their facilities. Prior to the pandemic, nursing homes had been included in epidemiological surveillance systems set up by Sciensano in only a limited (convenience sample) way, alongside a small but representative sample of hospitals and general practitioners. The general lack of previous data infrastructure and experience with data reporting meant that these requests in some cases added substantial pressures on nursing home staff, particularly when combined with the burdens placed on nursing homes in dealing with the pandemic itself. Moreover, unlike the data collected by Sciensano and the Incident Crisis Management System and used by the HTSC, data collected from nursing homes was primarily not collected to help manage the response in nursing homes, but focused on informing health authorities of the progression of the pandemic.

Good working relationships with nearby hospitals were considered critical at the beginning of the pandemic with regard to access, testing and receiving test results quickly, as well as to procure PPE (OECD, 2023[53]). Some nursing homes were able to leverage their good working relationships with virologists in local hospitals for further clinical advice on treating patients with COVID-19 in nursing homes. Proactively strengthening co-ordination and relationships between nursing homes and local health facilities, including hospitals, is necessary to help the long-term care sector better respond to future crises. During the pandemic, Belgium was already able to benefit from the co-operation of hospitals and long-term care facilities that exchanged knowledge, equipment, and staff and made use of their local hospital networks (loco-hospital networks) to organise patient transports (Rocard, Sillitti and Llena-Nozal, 2021[14]; Van de Voorde et al., 2020[58]). Other countries operated with similar measures, such as guidelines for better integration of long-term care facilities with hospitals, as in Canada, Estonia, Finland, Portugal, and Slovenia (Rocard, Sillitti and Llena-Nozal, 2021[14]). France profited from a central government strategy that was translated into regional measures, such as a hospital COVID-19 support platform for long-term care facilities (Rocard, Sillitti and Llena-Nozal, 2021[14]; Rolland et al., 2020[59]).

Belgium can build on preexisting structures and move towards a more integrated and co-ordinated approach to long-term care than was possible during the pandemic. For example, Belgium should integrate long-term care facilities into locally co-ordinated structures to give them as much weight as other healthcare facilities, and to strengthen timely infection prevention and control to outbreaks. Belgium could look to other OECD countries to strengthen the integration of nursing homes with the clinical system: Czechia, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Japan, Luxembourg, Portugal, Slovenia and the United States all reported having had legislation or guidelines on integrating primary and long-term care prior to the pandemic, while in Ireland, the National Integrated Care Progamme for Older Persons is developing a co-ordinated care pathway for older people, particularly those with complex needs, across primary, secondary and tertiary care (Rocard, Sillitti and Llena-Nozal, 2021[14]). Hospitals could strengthen their relationships with local long-term care facilities to improve co-ordination and infection control expertise and make use of their loco-hospital hospital networks to organise patient transports. Belgium should also consider how the inter-federal response to long-term care can be strengthened, including whether interministerial conferences could be used to improve the long-term care response in future events.

Following the gradual easing from the peak of the pandemic, the data infrastructure that was developed to collect information from long-term care facilities has been largely wound down. Data collection and monitoring challenges related to long-term care and nursing homes are well established in Belgium. While the monitoring set up during the pandemic was built quickly and intended to serve a specific pandemic-related purpose, authorities should consider how its legacy could be used to improve data collection efforts and surveillance in nursing homes, both during acute crises and as part of a broader agenda of care quality improvement.

4.3.4. Pandemic-specific data and information systems needed to be set up at the start of the pandemic to channel information and quickly proved crucial to informing decisions

The Belgian government managed to quickly set up the necessary infrastructure to monitor data on the spread of the pandemic to inform decision making. To some extent, it built on already existing structures that had been set up in past crises, although these were often less systematic than necessary to meet the COVID-19 challenge, had longer reporting horizons, and mostly relied on voluntary participation. This data infrastructure was built in the first few weeks and months of the pandemic. The time required to scale up a new data infrastructure, combined with challenges related to testing capacity at the start of the pandemic, meant that Belgium was only able to properly monitor the spread of the virus several weeks after the start of the COVID-19 outbreak.

The COVID-19 pandemic marks the first time all hospitals and long-term care facilities reported daily data to health authorities. Hospitals and long-term care facilities were initially surveilled on death rates only as large-scale testing was not available yet. An established reporting pathway of mortality data from hospitals was fully operational from 15 March 2020 onwards and was rolled out in the two subsequent weeks for long-term care facilities (Renard et al., 2021[1]). Information from hospitals was directly collected by the federal government, whereas information from medical doctors and long-term care facilities was collected by the regional authorities, and subsequently forwarded to federal authorities. Mass testing in long-term care facilities was only launched on 15 April, which finally allowed long-term care facilities to move towards more tailored strategies, for example by isolating individual cases. In other OECD countries, a limited availability of tests in long-term care facilities at the start of the pandemic also hampered a good response (OECD, 2021[57]). The United Kingdom launched a mass testing strategy in early April 2020 and introduced additional measures to increase testing rates over the course of that month (Rough, 2020[60]). South Korea, which was one of the first countries affected, moved earlier than many other OECD countries by introducing local testing in mid-February and drive-through testing in early March (Dighe et al., 2020[61])

In one case, the authorities responsible for infection control during the pandemic were initially unable to receive data for the population they were responsible for. Prior to the pandemic, the German-speaking Community had delegated the responsibility for infection control to Wallonia. Shortly after the start of the pandemic, in March 2020, this responsibility was transferred back from Wallonia to the German-speaking Community. While policies made within the German-speaking Community sometimes differed from the rest of Wallonia as a result, most data (with the notable exception of vaccination data and surveillance in long-term care facilities) were not available in public reports for this sub-population before November 2020, which complicated monitoring the effectiveness of measures taken to combat the virus.

Belgium operated three additional surveys to monitor the situation in hospitals (Van Goethem et al., 2020[62]). From early March 2020 onwards, hospitals were surveyed daily on their surge capacity via the Incident Crisis Management System, the hospital surge capacity survey, and the Clinical Survey. These surveys recorded structural hospital information, such as the available beds in intensive care units (ICUs), the number of available ventilators and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation devices (ECMOs), and patient information (such as on risk parameters and patient outcomes), and informed the daily meetings of the HTSC. They were adapted several times over the course of the pandemic to respond to the need for additional information. Following a data migration of the Clinical Survey in mid-September and extensions of the data collection, such as the social security number, data linkages became possible and these allowed for a more comprehensive analysis (Van de Voorde et al., 2020[58]). Data was also collected directly from electronic medical records used by GPs to monitor both the pandemic and the needs of general practitioners, including their access to PPE, workload, and support needs, and helped to inform decision making of the Risk Assessment Group (RAG) (Vaes et al., 2022[54]).

These additional surveys and an extensive data collection in general have allowed Belgium to better monitor the outbreak and to introduce corresponding adjustments to its health system. Belgium is encouraged to save this knowledge for future pandemics, to maintain an infrastructure that could be quickly reactivated in future health emergencies, to work torwards a structure that records data from different health sectors, and to ensure that actors which are in charge of organising the health system response are equipped with the necessary information to successfully fulfil their role. Building on its experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic, Belgium could proactively anticipate how its formidable electronic data infrastructure could be even more quickly employed to monitor the pandemic and its impacts on the population and mount a rapid response that takes into account the needs of vulnerable populations. In Costa Rica, for example, the digital integration of its multi-disciplinary teams allowed health authorities to use the data in electronic medical records to help in risk assessments and prioritisation, the identification of vulnerable patients, delivery of medicines to people’s homes, and arranging virtual visits for hospitalised patients (OECD, 2023[63]).

Overall, Belgium managed to quickly set up a data infrastructure and to successfully integrate it into the organisation of the pandemic response. For example, the collection of hospital data allowed the HTSC to co-ordinate capacities, to monitor the effect of their decisions on patient outcomes, and to adjust its decisions accordingly. Similarly, the Task Force Vaccination and regional entities used vaccination data to monitor the progress of the vaccination campaign and to identify where additional, tailored approaches were needed. Belgium is strongly encouraged to maintain its data infrastructure, and to systematically include means to monitor infection outbreaks.

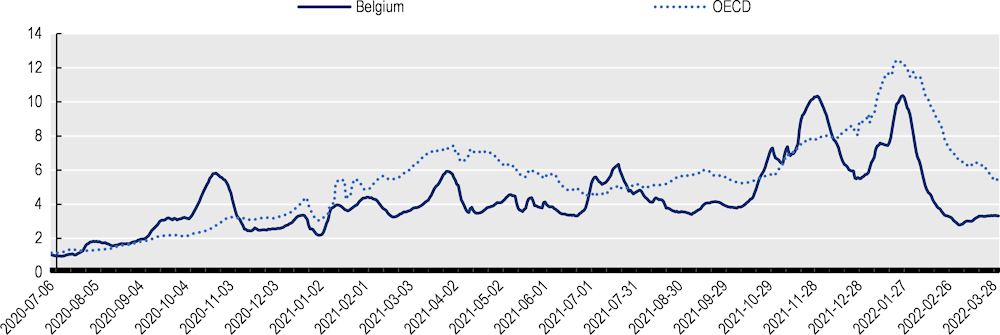

4.3.5. Belgium rapidly increased testing capacities in the first months of the pandemic

Following a slow start, Belgium managed to increase testing capacities and to reduce turnaround times, and testing and tracing played an important part in the mitigation of the virus and the deconfinement of the country (Willem et al., 2021[64]). Within the first weeks of the pandemic, the number of tests performed per 1 000 inhabitants in Belgium increased from below to considerably above OECD average. Over the period from 1 March 2020 to 31 March 2022, nearly 33 million tests were recorded on the national testing platform (Sciensano, 2023[65]). Daily reporting to a national database (healthdata.be) was mandatory. Overall, Belgium’s testing rates were close to the OECD average (Figure 4.11) (ECDC, 2022[66]).

Figure 4.11. Tests performed per 1 000 inhabitants in Belgium and the OECD

At the beginning of the pandemic, Belgium had very low testing capacities with only one laboratory, the National Reference Centre of the University Hospital of Leuven, performing tests against COVID-19. The country also faced a shortage in testing material and long turnaround times of several days. In addition, the testing protocol was initially very restrictive, with only symptomatic people returning from high-risk destinations eligible for COVID-19 tests, though this was broadened over the period from mid-March to June (Meurisse et al., 2021[67]). This limited Belgium’s initial capacity to understand and monitor the evolution of the pandemic in its country.

Belgium managed to increase the number of tests and turnaround times by increasing the number of laboratories, scaling up the workforce, and setting up effective financial incentives. In March and April 2020 alone, Belgium issued licenses to test against COVID-19 to 73 clinical microbiology laboratories. This was complemented by the federal testing platform, which was introduced in April 2020 to add additional test capacities. Pharmacists were allowed to perform rapid antigen tests from 12 July onwards, and beginning on 21 September 2021, Belgium granted the right to carry out laboratory tests to individuals without medical degrees. Different financing schemes helped to incentivise laboratories to increase capacities and reduce the turnaround time. Laboratories first received a financial guarantee to quickly set up and increase their capacities. Later, the payment was made conditional on reporting test results within 12 hours after performing the test, which managed to reduce the time between the sampling and reporting of the test result. As a result, average waiting times reduced from close to a week to less than one day within several weeks of the pandemic (INAMI, 2023[68]; Meurisse et al., 2021[67]).

The availability of self-tests greatly increased the total test coverage. It allowed individuals to quickly obtain a test result, to self-isolate, and to alert others in case of a positive test. From April 2021 onwards, self-tests were available in pharmacies at EUR 8 (later around EUR 5) per test, with a reduced price of EUR 1 for vulnerable groups. From July onwards, they were available in supermarkets for around EUR 2-6. Sales particularly increased around certain events such as the start of the Delta wave in October 2021 and the Christmas period (Lafort et al., 2023[69]).

Tracking and tracing efforts were further supported by the introduction of an app for contract tracing, and the availability of self-tests. The app Coronalert was launched on 30 September 2020 and alerted users of a potential high-risk contact after more than 15 minutes of exposure to a positive COVID-19 case within 2 meters or less using Bluetooth. From January 2021 onwards, the app was linked to COVID-19 apps of 10 other European countries, including France, Germany, and the Netherlands. The app was later retired in November 2022. Studies from Belgium about its effectiveness are lacking and it is not clear yet whether the benefits of the app justified its high costs. Evaluations from other OECD countries are mixed, with an evaluation from England and Wales showing that their app played a significant role in reducing the spread of the virus and helped prevent hospitalisations and deaths, whereas evaluations from Australia indicate limited effectiveness (Vogt et al., 2022[70]; Wymant et al., 2021[71]; Kendall et al., 2023[72]). Evaluations from Belgium identified limitations due to losses of information in the communication and time lags between the test results and the digital alert (Raymenants et al., 2022[73]; Geenen et al., 2023[74]). As in many other countries, concerns about privacy and data security in using the app were raised, with privacy concerns identified as a key driving factor among people who chose not to use or to discontinue use of the app (Jacob and Lawarée, 2020[75]; Walrave, Waeterloos and Ponnet, 2022[76]).

Box 4.1. Regional responses to testing and tracing

The testing and tracing itself was organised on the regional level, with the Interfederal Committee on Testing and Tracing serving as an advisory body to co-ordinate and harmonise the regions’ different testing and tracing strategies. Regions set up COVID-19 test centres and contracted with different providers to organise and perform these tests, such as hospitals and the Red Cross. Financing was shared by the federal and regional level. Costs for setting up test centres were borne by the regions, whereas the federal level covered costs for personnel and laboratories. “Testing villages” were set up to test a particularly high volume of people. For example, Wallonia converted the airport of Liège, the city of Antwerp in Flanders used a festival area, and Brussels set up a centre next to the Atomium. Following a positive test, call centres traced positive cases and their contacts by phone or home visits. These were set up by the regions and became operational in mid-May 2020 with the loosening of the first lockdown. They used outreach teams to visit people at their homes, particularly in vulnerable and hard-to-reach communities.

Across Belgium, some communities faced barriers of access to information and testing and turned to information from their home countries or social networks, which sometimes deviated from what was reported by Belgium (Nöstlinger et al., 2022[77]). Regions and municipalities introduced additional means to respond to these needs and to reach out communities with low testing rates and higher risks of transmission. In Brussels, for example, the contact centre operated in 15 languages during the peak of their activity. Antwerp set up a local contact tracing system where general practitioners reported index cases with complex need, such as limited language skills) to a network of Arabic and Berber-speaking volunteers following alerts by family physicians of outbreaks in certain communities (Verdonck et al., 2023[78]). In September 2020, this volunteer system was integrated in the Flemish structure of primary care (first line) zones. Antwerp also recorded outbreaks in the orthodox Jewish Community and sent out individual invitations for them to get tested. The co-operation with leading figures of the Jewish Community, such as rabbis and physicians, was essential in reaching out to the Jewish Community (Vanhamel et al., 2021[79]).