Evaluations allow countries to draw lessons from the COVID-19 crisis in order to strengthen their future resilience. This chapter presents the analytical and methodological framework for the evaluation that forms the basis of this report. It also sets the context by presenting the structural strengths and weaknesses of Belgium that may have impacted the country’s capacity to tackle the crisis. It ends with a brief overview of the crisis timeline and a synthesis of the evaluation’s main findings.

Evaluation of Belgium’s COVID-19 Responses

1. Evaluating the responses to the COVID-19 crisis in Belgium

Abstract

1.1. Introduction

On 11 March 2020, the World Health Organisation declared the COVID-19 outbreak a global pandemic. Throughout the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)’s membership, governments and societies had to react quickly to mitigate the crisis and its consequences. Almost four years later, governments are still seeking to draw lessons from what worked, what did not, for whom and why to better prepare themselves for upcoming crises.

To contribute to these efforts, Belgium has conducted several evaluations of its COVID-19 responses, whether by looking at the role of the National Crisis Centre (NCCN) in co-ordinating the overall crisis response, or by having an in depth look at the work of the federal and federated entities in managing the crisis and communicating to citizens (Belgian Chamber of Representatives, 2021[1]; Parlement Wallon, 2020[2]; Parlament der Deutschsprachigen Gemeinschaft Belgiens, 2022[3]; Brussels' Parliament, 2021[4]; Vlaams Parlement, n.d.[5]). Yet, no evaluation to date in the country has taken a cross government look at the entire risk cycle and how it was addressed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In this context, the evaluation presented in this report provides a comprehensive and multidisciplinary approach to assessing Belgium’s crisis responses. As such, the evaluation covers the full range of measures that OECD countries should examine in order to better understand what worked and what did not in their responses to the pandemic, from risk preparedness and crisis management to policy responses in the fields of health, education, economic and fiscal affairs, and labour market and social policies. In addition, the novelty of this evaluation is its cross-government nature, in a country where federated entities have a high level of autonomy in decision making. Indeed, this evaluation has come about as a result of an agreement between the federal and federated entities of Belgium. Finally, in order to address the complexity of the crisis response and provide an understanding of potential trade-offs and synergies between policies, the evaluation includes an element of transdisciplinarity. In that regard, the evaluation provides an assessment of the proportionality of measures adopted by the Belgian government, the extent to which these measures were able to preserve the quality of life of citizens, as well as their impact on youth and the elderly.

The opening chapter of this evaluation provides an overview of the methodological framework used, before looking at some of the structural strengths and challenges that may have had an impact on Belgium’s policy responses during the crisis. It ends by providing an overview of the main measures adopted during the period under review for the evaluation: from March 2020 to March 2022.

1.2. How was Belgium’s response to the COVID-19 crisis evaluated?

1.2.1. The OECD work on ‘evaluations of COVID-19 responses’

The OECD's work on government evaluations of COVID-19 responses identifies three types of measures that countries should assess to better understand what worked and what did not work in their response to the pandemic (OECD, 2022[6]) (see Figure 1.1):

1. Pandemic preparedness: measures taken by governments to anticipate a pandemic before it occurs and to prepare for a global health emergency with the necessary knowledge and capacity (OECD, 2015[7]).

2. Crisis management: policies and actions implemented by the public authorities in response to the pandemic once it has materialised, to co-ordinate government action across government, to communicate with citizens and the public, and to involve the whole-of-society in the response to the crisis (OECD, 2015[7]).

3. Response and recovery: policies and measures implemented to mitigate the impact of the pandemic and the resulting economic crisis on citizens and businesses, support economic recovery and reduce well-being losses. These measures include lockdowns and other restrictions to contain the spread of the virus, as well as financial support for households, workers and businesses and markets to mitigate the impact of the downturn, health measures to protect and care for the population, and social policies to protect the most vulnerable.

Figure 1.1. Framework for evaluating measures taken in response to COVID-19

Note: These phases are presented as a circle because they are not necessarily chronological

Source: OECD (2022[6]), “First lessons from government evaluations of COVID-19 responses: A synthesis”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/483507d6-en.

These three types of measures correspond to the main phases of the risk management cycle, as defined in the Recommendation of the Council on the Governance of Critical Risks (OECD, 2014[8]). The empirical relevance of this evaluation framework, presented in Figure 1.1, has been proven by a qualitative analysis of government evaluations (OECD, 2022[6]). Indeed, results from the OECD publication “First lessons from government evaluations of COVID-19 responses”, which summarises the key lessons learned from evaluations produced by OECD Member country authorities during the first 15 months of the pandemic response, show that the vast majority of these evaluations do address one or more of the three types of measures identified above: pandemic preparedness, crisis management, and response and recovery. This evaluation framework was recently tested in Luxembourg (see Box 1.1 for more information on the OECD work on COVID-19 evaluations and the Luxembourg case study). This present evaluation is built on a similar structure to best provide guidance to public authorities on how to learn from the crisis to increase resilience.

Box 1.1. OECD work on government evaluations of COVID-19 responses

The OECD work on government evaluations started in the midst of the pandemic, as countries sought to better understand what worked, what did not, for whom, and why. In this context, the OECD work on “First lessons from government evaluations of COVID-19 responses”, which was published in 2022, synthesised 67 evaluations carried out in 18 OECD Member countries during the first 15 months of the pandemic. The work consisted in a qualitative and systematic content analysis, identifying common themes through coding and a quantified approach. The analysis concludes that a significant proportion of the evaluations in the sample focuses on one or more of the three primary phases of risk management defined by the OECD Recommendation on the Governance of Critical Risks: pandemic preparedness, crisis management, and response and recovery (OECD, 2014[8]). As a result, these three types of measures, are the ones that countries should assess to better understand what worked and what did not work in their response to the pandemic (OECD, 2022[6]).

The resulting ‘OECD framework for evaluating measures taken in response to COVID-19’ was applied for the first time in Luxembourg (OECD, 2022[9]). The Evaluation of Luxembourg’s COVID-19 responses found that:

Luxembourg had a mature risk management system, enabling the country to quickly answer to the emergency.

The management of the crisis was agile, even though its scientific advice and monitoring systems could have been strengthened.

The health system remained resilient with excess mortality lower by more than 60% compared to the OECD average, but faced challenges related to the preparedness of the health sector.

The education system allowed for good educational continuity, even though greater differentiation and broader consultations would have strengthened Luxembourg’s response.

On economic and fiscal affairs, support measures safeguarded the financial situation of the hardest-hit businesses and maintained employment. Efforts regarding the self-employed and the digitalisation of administrative procedures should be made to increase resilience.

In terms of its labour market and social policies, Luxembourg was relatively well prepared for the pandemic, even though there remains room for some fine-tuning.

The Luxembourg evaluation was the first one of this series of evaluation of governments’ response to the COVID-19 pandemic, which aims to provide evidence and concrete recommendations to help countries build resilience to large-scale crises such as pandemics.

Source: in text.

1.2.2. An evaluation based on a mixed-methods approach

The study of Belgium’s COVID-19 responses relies on a mixed-methods approach, which combines the use of qualitative and quantitative data for evaluation. In addition, the study makes use of data that has been collected specifically for the purposes of the evaluation, through the use of ad hoc surveys mainly, as well as administrative and firm-level data. Combining these different data sources and analysis methods allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the research questions explored in this evaluation, as well as to increase the validity and reliability of its findings. As a result, the evaluation looks at not only what has worked in Belgium and what did not, but also for whom and under what circumstances – thus acknowledging that policies may work differently for different people and groups depending on local circumstances.

First, the evaluation builds on qualitative data collected in the context of the OECD’s work of COVID-19 responses (see Box 1.1). Indeed, it builds upon the evidence collected from evaluations of COVID-19 responses in 18 OECD Member countries, as well as the Evaluation of Luxembourg’s COVID-19 Response (OECD, 2022[6]; OECD, 2022[9]).

Second, the evaluation relies on the use of specific surveys designed by the OECD for the purpose of this evaluation. Those qualitative and perception-based surveys were sent to stakeholders to gather data on the effectiveness of policies from their point of view. Surveys that are not statistically representative are explicitly stated as such when discussing survey results. These surveys have sought to gather data from the following institutions and actors across the country:

Municipalities: This survey was aimed at better understanding the extent to which the federal government and federated entities co-operated well with municipalities during the crisis, from the point of view of the latter group. The survey was sent out to all 581 municipalities in the country with the help of the three regions and the German-speaking Community. Of these municipalities, a total of 259 answered the survey (the response rate was 129/300 in Flanders, 114/262 in Wallonia (excluding municipalities from the German-speaking Community), 9/19 in Brussels-Capital, and 7/9 in the German-speaking Community). As a result, the survey results can be considered representative of Belgium as a country. The survey responses have been used to analyse the effectiveness of the country’s pandemic preparedness and anticipation (see Chapter 2), its management of the crisis, in particular in regards to how information was communicated to citizens and the extent to which the country adopted a whole-of-society response to the pandemic (see Chapter 3), as well as how municipalities were prepared to implement the test & trace and vaccination strategies (see Chapter 4) (OECD, 2023[10]).

General Practitioners: This survey was aimed at better understanding the response of general practitioners to the crisis. The survey was sent out to about 15 000 general practitioners in the country, with the help of the Federal Public Service Public Health. 420 out of those practitioners completed the survey, making it representative of general practitioners in Belgium. 261 respondents practiced medicine in Flanders, 110 in Wallonia and 46 in Brussels (3 declined to report where they practiced). More information on the questions distributed to the general practitioners as part of this survey can be found in Box 1.2. The survey responses have been used to understand the preparedness of general practitioners to the COVID-19 pandemic and their responses to the pandemic, as well as to evaluate what potential impact the pandemic may have had on their own well-being and views on practicing medicine (see Chapter 4) (OECD, 2023[11]).

Hospitals: This survey was aimed at better understanding the response of hospitals to the crisis. The survey was sent out to all 103 acute care hospitals in the country, with the help of the Federal Public Service Public Health. Of these hospitals, 32 completed the survey. As a result, the survey is not representative of all acute care hospitals, but nevertheless provides interesting insights on how hospitals dealt with the crisis. The survey responses have been analysed to better understand how hospitals anticipated pandemics and to understand their level of preparation going into the crisis (see Chapter 4) (OECD, 2023[12]).

Primary and secondary schools: This survey was aimed at better understanding the satisfaction of primary and secondary school leaders with measures taken by the community governments to tackle the pandemic. The survey was distributed to all 6 608 primary and secondary school in Belgium, with the help of the three language communities. Of the schools, a total of 951 answered the survey (the response rate was 477/3 815 in the Flemish Community, 460/2726 in the French Community, and 14/67 in the German-speaking Community). The survey is therefore not representative of schools in Belgium but nevertheless provides insights on how policy responses were received by school leaders. The survey responses have been used to analyse the educational policy response to the crisis, the overall satisfaction of school leaders with support provided by and communication from communities (see Chapter 5) (OECD, 2023[13]).

Box 1.2. The OECD survey to Belgian general practitioners

As in many other OECD countries, primary care played a significant role in the pandemic response in Belgium (see Chapter 4). Most general practitioners in Belgium are self-employed, and while many are members of medical associations and networks of general practitioners (GPs), no central authority representing the voice of all general practitioners exists in Belgium.

The high number of general practitioners in Belgium and the likelihood of differing views and experiences of the pandemic amongst them, led to the development of the OECD Survey of Belgian general practitioners in the context of the Evaluation of Belgium's COVID-19 responses, which was circulated to all 15 000 GPs in Belgium with the help of the Federal Public Service Public Health. 420 general practitioners completed the survey.

This subset can be considered to reflect a representative sample of general practitioners across the country with a 95% confidence level and a 5% margin of error. Moreover, the proportion of responses coming from each of the three regions of Belgium (Brussels, Flanders and Wallonia) roughly reflect the relative population sizes of these regions.

Survey questions focused on:

General practitioners’ experiences during the pandemic, including its impact on their workload, their access to personal protective equipment, and whether they felt sufficiently informed during the pandemic and had access to the information and training they needed.

The evolution of care provided by GP practices during the pandemic, including their uptake of telemedicine and outreach to vulnerable populations.

The impact of the pandemic on their mental health and well-being, including on whether the pandemic impacted their intentions to leave the medical profession.

This evaluation also benefited from access to previously collected survey data. Additional analyses have been conducted based on the PRICOV-19 survey data for Belgium. An analysis of the perceptions of the impact of the support measures across the regions relying on surveys of businesses, conducted by the Economic Risk Management Group (ERMG) during the crisis, was also used to assess business owners’ perception of support measures and the impact of the crisis on their investment and employment plans. The analysis of labour market and social benefits relies on survey micro data, notably from the European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS) and the European Union Statistics on Incomes and Living Conditions (EU-SILC), as well as (largely survey-based) OECD data sources, such as the Income Distribution Database (IDD). Other OECD multi-country surveys have been used throughout the evaluation, notably the 2022 OECD Survey on the Governance of Critical Risks.

Finally, firm-level and administrative data on selected business support measures were used to assess the impacts of Belgium’s policies on firms’ activity during the crisis (see Box 1.3 for more information), as well as administrative data from the OECD Social Expenditure (SOCX) and Social Benefit Recipients (SOCR) databases. Hospital data collected by the Hospital & Transport Surge Capacity Committee (HTSC) was used in order to investigate hospital transfers during the pandemic, especially transfers from nursing homes to hospitals.

Box 1.3. Data used to evaluate the economic response to the crisis

The OECD used micro data from several Belgian administrations to evaluate the impact on firms of the differences across regions in the design, timing and implementation of support measures. The different datasets were gathered, merged and pseudo-anonymised by STATBEL, to allow the OECD to conduct a difference in difference analysis (DID) with a continuous treatment.

Administrative data from the Banque Carrefour des Entreprises, Social Security Database and Central Balance Database (STATBEL)

The combination of these three datasets gathers information on firms’ sector of activity (2-digit NACE codes), their region of establishment, potential bankruptcy, revenues, capital and other non-financial characteristics (e.g. number of years since creation, workforce size, etc.). Additional information from the Social Security Database provides insights on labour costs and workers’ temporary unemployment: how many employees were affected, how many hours were covered, the type of unemployment, etc.

Information on tax cancellations from FPS Finance

The VAT database provided by FPS Finance provides information on firms’ applications to tax cancellation and deductions – including rejected applications. This data covers the nature of the debt covered, the remaining balance, the reason for financial hardship and the payment plan.

Information on regional grants and loan schemes from the federated governments

Information on regional emergency grants were made available by the Service public régional de Bruxelles (SPRB) for Brussels-Capital, Flanders Innovation and Entrepreneurship (Agentschap Innoveren & Ondernemen, VLAIO), and Service public de Wallonie Economie,Emploi, Recherche (SPW EER) for Wallonia. The data contains information on the timing of the applications and the total amounts of direct support granted.

Quantitative data collected were further cross-referenced with qualitative interviews with key stakeholders of the COVID response. The institutions met by the OECD teams were identified jointly by the OECD and two consultative bodies: a Task Force, made up of representatives from each of the federated entities and the federal government, and an Advisory Group, composed of 6 French-speaking and 6 Dutch-speaking experts coming from a variety of research fields (see Annex 1.B for more information on the list of stakeholders). As part of these interviews, the OECD teams were able to meet with over 150 stakeholders, including ministerial cabinets and public administrations at federal and federated levels, representatives from schools, the health sector (hospitals and medical centres), representatives of academia, civil society and trade unions. Roundtables and further interviews were also organised with several governors, long-term care facilities, and health professionals directly involved in the management of COVID-19.

1.2.3. The evaluation analyses the measures adopted by Belgium, their implementation processes and the results obtained

Finally, to better understand what worked, what did not, and for whom, this report builds upon the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) evaluation criteria, assessing and drawing lessons from the relevance, coherence, effectiveness, efficiency, impact and sustainability of measures taken.

Box 1.4. Evaluation criteria of the Development Assistance Committee

The OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) has become the main benchmark body for evaluating projects, programmes and policies in all areas of public action. Each criterion represents a different filter or perspective through which the intervention can be analysed.

Taken collectively, these criteria play a normative role. Together, they describe the characteristics expected of all interventions: that they are appropriate for the context, that they are consistent with other interventions, that they achieve their objectives, that they produce results economically, and that they have lasting benefits.

Relevance: the extent to which the interventions’ objectives and design respond to beneficiaries’ needs and priorities, align with national, global and partner/institutional policies and priorities, and remain relevant even as the context changes.

Coherence: the extent to which the interventions are consistent with other interventions being carried out within a country, sector or institution.

Effectiveness: the extent to which the interventions achieved, or are expected to achieve, their objectives and their results, including differential results across groups.

Efficiency: the extent to which the interventions deliver, or are likely to deliver, results in an economic and timely way.

Impact: the extent to which the interventions have generated or are expected to generate significant positive or negative, intended or unintended, higher-level effects.

Sustainability: the extent to which the net benefits of the interventions continue or are likely to continue.

Source: OECD (2021[14]), Applying Evaluation Criteria Thoughtfully, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/543e84ed-en.

These different criteria are covered extensively throughout this report and its respective chapters. Chapter 2 looks at the relevance and effectiveness of risk anticipation and preparedness measures, taken before the beginning of the federal phase. Chapter 3 analyses the relevance, coherence, effectiveness and efficiency of the overall crisis management of the crisis. Finally, Chapters 4, 5, 6, and 7 assess the effectiveness, efficiency, impact and sustainability of the response and recovery, at both federal and federated levels where relevant.

Table 1.1. Evaluation questions addressed in this report

|

Evaluation criterion |

Evaluation question |

Pandemic preparedness |

Crisis management |

Response and recovery |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Public health policy |

Education policy |

Economic and fiscal policy |

Social and labour policy |

||||

|

Relevance |

Is the intervention addressing the problem? |

X |

X |

||||

|

Coherence |

Is the intervention aligned with the other interventions? |

X |

|||||

|

Effectiveness |

Is the intervention achieving its objectives? |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Efficiency |

Are resources being used optimally? |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Impact |

What differences is the intervention making? |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

Sustainability |

Will the benefits last? |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||

Source: OECD authors’ own elaboration based on (OECD, 2022[9]), Evaluation of Luxembourg's COVID-19 Response: Learning from the Crisis to Increase Resilience, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/2c78c89f-en.

Addressing those questions and assessing Belgium’s capacity to respond to the COVID-19 crisis requires better understanding of the structural strengths and challenges inherent to Belgium. These factors have been significant in defining the initial government’s room for manoeuvre in its response to the crisis and the overall performance of the policies adopted. Therefore, this chapter presents the main demographic, geographic, public governance, economic and social issues in Belgium that might have impacted its capacity to prepare for, manage and respond to the COVID-19 crisis.

1.3. Understanding the context: What were Belgium’s structural strengths and challenges in responding to the crisis?

Several factors can affect a government's ability to deal with a crisis. Firstly, each country has its own particular characteristics, which can pose challenges for policy development and implementation, even in times when democratic life is functioning normally. In the case of a crisis of the magnitude of that of COVID-19, there are even more of these factors as combating the threats posed by the pandemic required a massive response from governments in all areas of public life. As such, to assess a government's response to the crisis, one must first understand the extent to which that government was able to take these factors into account in order to deploy measures appropriate for their national context (these fall under the relevance and coherence criteria).

Moreover, assessing the effectiveness of a given government's response to the crisis requires, among other things, its results to be compared with those of other countries. This comparative analysis cannot be completed without a detailed understanding of the direct and indirect impacts that these political, economic and social factors may have had on measures to mitigate the effects of the pandemic. A mid-sized country like Belgium, which is very decentralised and multi-cultural, therefore does not face the same challenges or have the same assets when controlling a pandemic as much smaller, insular country, for example. In this context, this section presents the particular geographical, demographic, political, economic and social features of Belgium that may have represented a challenge or an asset in the face of the crisis.

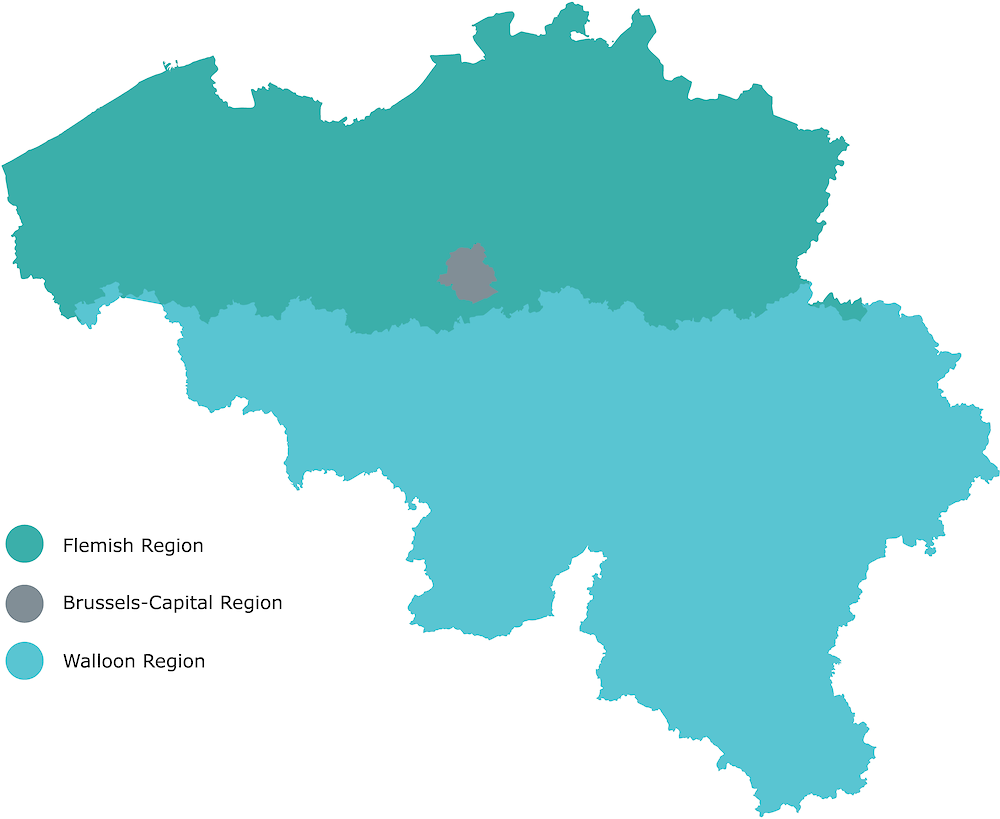

1.3.1. The public governance system in Belgium is highly decentralised

Belgium is a federal and highly decentralised country with three tiers of government: the federal State, the regions (Brussels-Capital, Flanders, Wallonia), and the language-based communities (Dutch, French, and German-speaking) (Figure 1.2). Those three tiers have equal decision-making power, making the division of competencies a key aspect of Belgian public governance. Co-ordination across levels of government, and in particular collaboration on topics where responsibilities are shared between levels of government, is ensured either through thematic interministerial conferences, or through the Concertation Committee – which is the central point for concertation, co-operation and co-ordination between the federal level, regions and communities, to achieve individual or joint objectives respecting everyone’s competencies (Belgian Official Journal, 1980[15]).

Figure 1.2. Geography of Belgium’s federated entities, at regional and community levels

Note: Top panel: Map of Belgian regions. Bottom panel: Map of language communities in Belgium.

Source: Federal Public Service Chancellery of the Prime Minister.

Federal competencies relate to the common interest of all Belgians and include public finances, the army, the judiciary, social security, or foreign affairs. It also includes competencies over everything that is not covered by regions or communities. Regions have core competencies related to the economy, public health, employment, agriculture, water policy, housing and energy, amongst others. Finally, language communities have competencies over, amongst others, culture and education (Belgium.be, n.d.[16]).

In practice, however, many competencies are shared between several, if not all, levels of government, especially since the sixth constitutional reform (Di Rupo, 2011[17]). In particular, health competencies are shared between those three tiers of government. The federal level oversees regulating social health insurance, health products and health professionals, and the establishment of ambulatory and hospital budgets. Regions are responsible for older citizens’ health, mental health, hospital infrastructure, and primary care services. Communities oversee preventative measures to preserve the health of minors, including vaccination and teaching hospitals (Belgium.be, n.d.[16]). The situation is different for the French Community, which devolved some of its competencies to Wallonia and specific regional institutions from Brussels.

As a result of this division of labour between levels of government, the different federal and federated entities have learned to work closely together on matters related to health in the past decades. For instance, interministerial conferences on health are held regularly in the country, so as to ensure that the eight health ministers can meet and ensure proper co-ordination across the entities they represent. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the interministerial conference on public health convened very frequently ahead of meetings of the National Security Council or the Concertation Committee.

Belgium also has two levels of local administrative units: the provinces and municipalities. Both of these units play an official role in the crisis management system and, as a result, have been actors in the response to COVID-19. The 10 provinces of Belgium exercise different roles depending on whether they are acting under the authority of federal authorities, that of the regions, or that of the communities. Governors are responsible for emergency planning for crisis situations requiring national co-ordination or management (Belgian Official Journal, 2003[18]). During the crisis, some heads of provinces acted on this basis to take additional measures against COVID-19. Municipalities are responsible for maintaining public order and the local police, amongst other competencies. The 589 municipalities are also involved in emergency planning, when co-ordination can be done at the local level (Belgian Official Journal, 2003[18]).

1.3.2. Belgium’s political system reflects its cultural diversity

At the federal level, coalition governments with an important number of parties have been recurring in recent years

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a federal constitutional monarchy with a bicameral parliamentary system. The King is therefore the head of state, while the Prime Minister is head of government. Belgian political institutions seek to balance representation of different cultural and language communities. The important number of parties represented in the national Chamber of Representatives (12 parties in 2023) fragments the political landscape, which leads to government coalitions with a large number of partners. Since 2010, Belgium has experienced 7 federal governments – whether of full exercise or care-taking (Table 1.2). The latest government is the result of a coalition between 7 different parties.

Table 1.2. Belgian Federal governments since 2010

|

Government |

Status |

Term start date |

Term end date |

Length |

Parties in the coalition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Leterme II |

Full exercise |

25 November 2009 |

26 April 2010 |

5 months, 1 day |

CD&V, MR, PS, Open VLD, CDH |

|

Care-taking |

26 April 2010 |

6 December 2011 |

1 year, 7 months, 10 days |

||

|

Di Rupo |

Full exercise |

6 December 2011 |

26 May 2014 |

2 years, 5 months, 20 days |

PS, CD&V, MR, Open VLD, SP.A, CDH |

|

Care-taking |

26 May 2014 |

11 October 2014 |

4 months, 15 days |

||

|

Michel |

Full exercise |

11 October 2014 |

9 December 2018 |

4 years, 1 month, 28 days |

N-VA, MR, CD&V, Open VLD |

|

Full exercise |

9 December 2018 |

21 December 2018 |

12 days |

MR, CD&V, Open VLD |

|

|

Care-taking |

21 December 2018 |

27 October 2019 |

10 months, 6 days |

||

|

Wilmès I |

Care-taking |

27 October 2019 |

17 March 2020 |

4 months, 19 days |

MR, CD&V, Open VLD |

|

Wilmès II |

Full exercise |

17 March 2020 |

1 October 2020 |

6 months, 14 days |

MR, CD&V, Open VLD |

|

De Croo |

Full exercise |

1 October 2020 |

PS, MR, Ecolo, CD&V, Open VLD, SP.A, Groen |

Note: CD&V is the Christian Democratic and Flemish party (EPP), Ecolo (Greens/EFA), Groen (Greens/EFA), MR is the Reformist Movement (Renew), N-VA is the New Flemish Alliance (ECR), Open VLD is the Open Flemish Liberals and Democrats (Renew), the PS is the Socialist Party (S&D), SP.A is Vooruit (S&D). Between brackets are each party’s affiliation in the ninth legislature of the European Parliament.

Legislative power in Belgium is divided between federal and federated Parliaments

The legislative power in Belgium is exercised at the federal level by the Chamber of Representatives (La Chambre des représentants/ Kamer van Volksvertegenwoordigers/ Abgeordnetenkammer) and the Senate, and by the unicameral Parliaments of the federated entities. The federal Chamber of Representatives is composed of 150 members of parliament divided in two linguistic groups of 61 French-speakers and 89 Dutch-speakers. Members of parliaments in the lower chamber are elected for a five-year term by direct universal suffrage. The Senate is composed of 60 senators, 50 of which are designated by the Parliaments of each federated entity.

The Parliaments of federated entities are unicameral. Members of Parliament of the federated legislative bodies are also elected for a five-year term. During the pandemic, the federal level and most federated entities decided to use special powers, modifying temporarily the legislative process (see Chapter 3 of this report for more information). All Belgian Parliaments also adapted their working methods to comply with restrictions taken to tackle COVID-19 (Jousten and Behrendt, 2022[19]).

1.3.3. Belgium faces challenges with trust in public institutions despite high satisfaction in public services

Trust in public institutions and satisfaction with public services are critical indicators of a fit-for-purpose governance, particularly during a crisis. While high trust in public institutions is not a prerequisite for sound democratic governance, trust and satisfaction in public services are associated with greater policy compliance, increased participation in public life, and enhanced social cohesion.

In Belgium, trust in public institutions is lower on average than in OECD Member countries. Less than one third of Belgians report high or moderately high trust in their national government (32%), almost 10 percentage point lower than the OECD average (41%). Similarly, the share of citizens having high or moderately high trust in the civil service (41%), parliament (33%), or courts and the legal system (51%) is significantly lower than the OECD average (respectively 50%, 39%, and 57%).

Those numbers contrast with the high satisfaction of Belgians in their public services. Satisfaction with the health care system (90%), education system (75%), and administrative services (71%) are all significantly higher than the OECD average (respectively 68%, 67%, and 63%). Those numbers underscore how reliable the government has been perceived, even during COVID-19. This reliability however faces limits, as 44% of Belgians believed in 2021 it was unlikely their government would be prepared to protect people’s lives in the event of a new serious contagious illness, a much higher share than the OECD average (33%) (OECD, 2022[20]).

Trust is important to ensure the effectiveness of the pandemic containment measures insofar as a lack of trust can lead citizens to not comply with the rules of social distancing and mask-wearing, or to not participate in vaccination campaigns. Yet, recent research on the satisfaction of Belgians with the government’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic shows that the average satisfaction with the government’s handling of the crisis in Belgium was 5.5/10, making Belgium the 8th highest ranking country out of 28 (Gugushvili et al., 2023[21]). Satisfaction was the highest with policies related to the national health service (6.9/10), and lowest for policies to support elderly people in long-term care facilities (4.7/10). The study also identified that general worldviews had a higher impact on satisfaction than socio-economic background or exposure to the effects of the crisis. In this sense, trust in government is the strongest predictor of satisfaction with the crisis response, with a 3-point gap in overall satisfaction between individuals who fully trust public institutions and those who fully distrust them. This further strengthens the need to build trust to best prepare to future crises and reinforce democracy.

1.3.4. Belgium’s population is ageing and faces public health challenges

Belgium’s ageing population was in good health despite some important behavioural risk factors

Prior to the pandemic, the Belgian population’s overall health profile was relatively high compared to the EU average, with 74% of Belgians stating in 2019 being in good or very good health (higher than the EU average of 68.5%) (OECD, 2021[22]). There were however socio-economic disparities, with only 60% of Belgian adults in the lowest income quintile reporting good health, compared to 90% in the highest quintile (OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2019[23]). However, more than a third of deaths in 2019 were linked to behavioural risk factors such as tobacco smoking (18%), dietary risks (11%), alcohol consumption (6%), or low physical activity (2%).

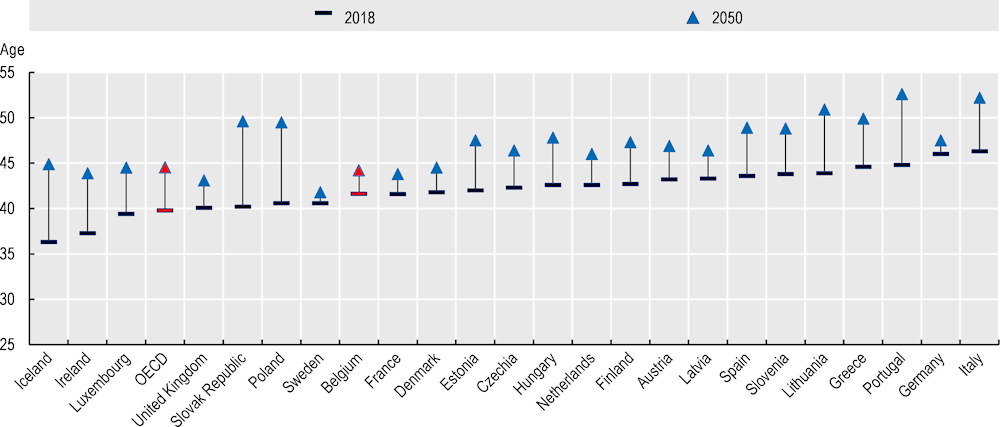

In addition, Belgium’s population has been rapidly ageing, whilst still being relatively younger than the EU average. The fertility rate in the country is of 1.6 in 2019 and a two-year increase in life expectancy at birth gained between 2010 and 2019 (Eurostat). The Belgian population is therefore ageing, and the median age was expected, pre-COVID, to grow from 41.6 years old in 2018 to 44.2 in 2050 (Figure 1.3) (OECD, 2019[24]). Its population of 11.5 million inhabitants (2019) remains younger than the European Union average, with 18.9% of the population being over 65 years old, against 20% in the European Union (Eurostat). The population is unevenly spread out across regions, with Flanders accounting for almost 60% of the Belgian population (Eurostat).

Figure 1.3. The Belgian population is ageing at a slower pace than most OECD countries

Median age of selected European OECD countries

Source: Adapted from (OECD, 2019[24]). Eurostat estimates and projections for European countries; and national estimates and projections for the other countries.

Belgium’s health system benefited from important expenditures and mixed workforce capacity

Belgium’s health expenditure reached 10.7% in 2019, a higher share than the EU average of 9.9%. Government and compulsory social health insurance represented 77% of all health expenditure. Moreover, inpatient care represented 36% of total health expenditure, higher than the EU average of 29%. On the other hand, outpatient care accounted for almost one quarter of health expenditure. Finally, spending on prevention remained significantly lower in Belgium (1.6%) than in the European Union (2.9%) (OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2021[25]).

Belgium saw a continuous decrease in the number of hospital beds from 2007 until the COVID-19 pandemic (OECD Health Statistics 2023). On the other hand, the number of practising doctors was 3.1 per 1 000 population, below the EU average of 3.6. This number had increased in recent years. Similarly, the number of nurses had increased over the past decade, reaching 11 nurses per 1 000 in 2016, above the EU average of 8.5 (OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2019[23]).

The Belgian health system’s performance was higher than in most EU countries

Pre-pandemic, the effectiveness of the Belgian health system was higher than the European Union (EU) average. Indeed, Belgium’s healthcare system was more effective at treating acute conditions than the EU average, with a treatable mortality rate in 2018 of 71 per 100 000 population in Belgium vs. one of 92 in the European Union. It was also slightly more effective at limiting preventable mortality than the EU average (146 per 100 000 population, vs 160), but less effective than most western European countries (OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2021[25]).

The Belgian health system also remained more widely accessible than in other EU countries. In 2019, 2% of the population reported unmet medical care due to cost, waiting time or travel. However, there were socio-economic discrepancies in unmet health needs, with 4% of Belgians in the lowest income quintile reporting such cases in 2019, compared to 0.2% in the highest quintile. This difference was above the EU average but the largest amongst western European countries (OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2021[25]).

Finally, Belgium’s health system was relatively resilient pre-pandemic, with important progress having been made in several areas. First of all, health spending had increased in line with GDP growth in recent years. Moreover, initiatives were under way to improve access to new medicines at affordable costs. Finally, primary care was becoming more integrated, with the adoption in 2015 of a national plan on “integrated care for better health” (OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2019[23]).

1.3.5. Belgium’s education systems are highly autonomous

The education sector is highly decentralised in Belgium

Belgium’s education system is historically characterised by a high-level of decentralisation. The federal level only exercises competencies related to the number of years spent in compulsory education, minimum requirements for the recognition of diplomas, and retirement regulations of education staff. The language communities establish their own policies on vision, improvement, and operation of their respective education systems (see Chapter 5).

Moreover, the principle of freedom of education allows every natural or legal person the right to open a school. This leads to significant autonomy for school boards to define, amongst others, teaching methods and curriculum, as long as it remains compatible with the language community-based learning outcomes.

Additionally, multiple school networks co-exist together in each community: among which education under the direct responsibility of the community, grant-aided schools public managed, and grant-aided schools privately managed. This highly decentralised landscape is nuanced by the existence of umbrella organisations, representing school interests in discussion with language communities and offering support related to curriculum and pedagogy.

Despite significant investments in the field, disparities in education outcomes have persisted

Before the start of the pandemic, Belgium was one of the OECD Member countries investing the most per student. In 2019, Belgium allocated USD 15 024 per full-time equivalent student in primary to tertiary educational institutions, surpassing the OECD average of USD 11 990 and EU22 average of USD 12 195 (adjusted for purchasing power). Moreover, from 2012 to 2019, Belgium saw a yearly increased total expenditure per student of 0.5%, lower than the 1.8% of the OECD average (OECD, 2022[26]).

In 2018, PISA data highlighted Belgian students, on the whole, outperformed the OECD average in reading, mathematics and science. However, substantial variations exist based on the education system and students' socio-economic backgrounds. Performance diverges significantly among language communities, with students in French and German-speaking Communities achieving reading and science scores below the OECD average. Moreover, Belgium also grapples with issues of equity in education, with socio-economic status of students being one of the largest factors impacting reading performance, explaining 17.2% of the performance variance (compared to the OECD average of 12%).

1.3.6. Belgium’s economic growth faced several macroeconomic and financial challenges limiting the fiscal space available to act during the crisis

Prior to the crisis, Belgium’s public finances left limited fiscal space to tackle the pandemic and subsequent fiscal challenges (OECD, 2022[27]) (OECD, 2023[28]). In 2019, prior to the pandemic, general government gross debt reached 119.6% in Belgium, higher than the OECD-EU average of 97.7% and all of its neighbours but France. Back then, the high level of public debt and public spending, labour-oriented taxation, and population ageing were identified as three of the main macroeconomic and financial challenges of Belgium’s economy (OECD, 2020[29]).

From 2016 to 2018, Belgium experienced moderate economic growth, lower than the EU average. Its growth rate however surpassed that of the European Union in 2019. The growth rate in Belgium was 2.3% compared to an EU average of 1.8%. Moreover, Belgium’s economy is highly integrated with the EU and reliant on trade, further impacting Belgium’s economic resilience during the pandemic. Net exports had brought negative contributions to economic growth from 2014 to 2018, apart from 2017. In 2018, countries from the Euro area represented its first trading partner, representing respectively 57% and 52% of goods and services exported. With the United Kingdom representing 8% and 9% of goods and services exported, the impact of Brexit was forecasted to be higher than for the rest of the European Union in the medium and long term (OECD, 2020[29]).

1.3.7. Socio-economic disparities remain important throughout the country

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Belgium’s labour market experienced robust job creation and low rates of unemployment, alongside significant challenges. Indeed, until the COVID-19 pandemic Belgium experienced low labour market activity rates, labour market transitions, weak productivity growth, growing skill shortages and regional disparities (OECD, 2022[27]).

Table 1.3. Regional disparities in labour market and related outcomes are sizeable, 2018

1. Aged 15-74.

2. As a % of active population.

3. Aged 15-24.

4. Aged 15-64.

Source: From (OECD, 2020[29]) and Eurostat.

However, labour shortages in certain sectors and occupations coincide with low employment rates for specific socio-economic groups: Employment gaps are particularly high for people with disabilities (52%), low educated people (44.3%), older workers (36.7%), and non-native (30.7%), and they are more widespread than across the OECD on average. Those gaps can be explained by a combination of barriers related to work readiness (low education, low skills, etc.), work availability (health limitations, care responsibilities), and work incentives (high non-labour income, high earnings replacement benefits). Those employment gaps can translate into poverty risks, which vary by region and across socio-economic groups. In Belgium, regional poverty risks range from 12% to 38% and affect predominantly the unemployed and people with low-level education (OECD, 2022[27]).

Socio-economic disparities between regions and provinces remain important (Königs, Vindics and Diaz Ramirez, forthcoming[30]). In 2019, the regional income per equivalised household in current prices was of EUR 35 668 in Flanders, EUR 30 372 in Wallonia, and EUR 29 786 in Brussels Capital (OECD Stat).

1.4. How did Belgium respond to the crisis?

1.4.1. A brief timeline of the crisis

It is in this geographic, demographic, economic and social context that, from the start of 2020, Belgium has put in place policies to prepare for the arrival of the pandemic. From January 2020, the federal government - through the Federal Public Service Public Health and the Risk Management and Risk Assessment Groups (hereafter RMG and RAG) - monitored developments related to the COVID-19 situation.

On 19 January 2020, public health authorities included the novel coronavirus as a disease with mandatory notification under “unusual threat”. In the following days, the National Crisis Centre (NCCN) and the Federal Public Service Public Health (FPS Public Health) started exchanging on the potential upcoming crisis. The RAG met several times to best define how to deal with potential repatriation cases coming from the People’s Republic of China.

In February, discussions in the RMG and the RAG focused on procedures to determine when repatriated patients could go home, increased repatriation of Belgian nationals and increasing testing capacity. In parallel, the NCCN continued its collaboration with the FPS Public Health. On 7 March, the RAG was tasked by the RMG to develop a set of actions to enhance social distancing.

On 12 March, the federal phase of the crisis was declared, meaning that the federal government became officially in charge of co-ordinating the crisis response. That same evening, the government announced the closure of schools, clubs, cafés and restaurants, as well as the cancelling of public gatherings, taking effect the next day at midnight. On 17 March, a lock-down is announced for the whole country.

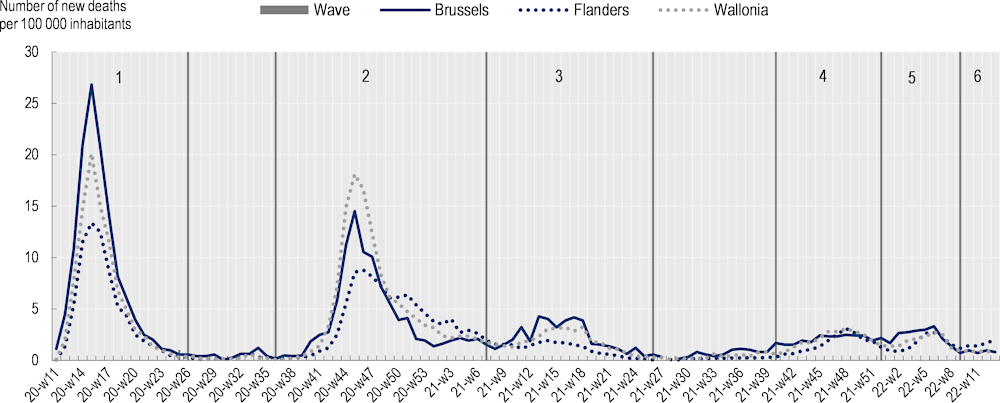

This evaluation spans the entire duration of the crisis, from the detection and identification of the first COVID cases in Europe in January 2020 until the end of the so-called federal phase of the crisis in Belgium on 14 March 2022. Throughout this period, Belgium experienced 6 distinct epidemiological waves (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4. Epidemiological waves of COVID-19 in Belgium

Weekly new deaths per Belgian region per 100 000 inhabitants

Note: Periods 1-6, demarcated by blue lines, indicate the number of the wave. Waves are based on (Jurcevic et al., 2023[31]).

Source: Sciensano (2023[32]), Sciensano COVID-19 Datasets. Data was extracted on 30 October 2023.

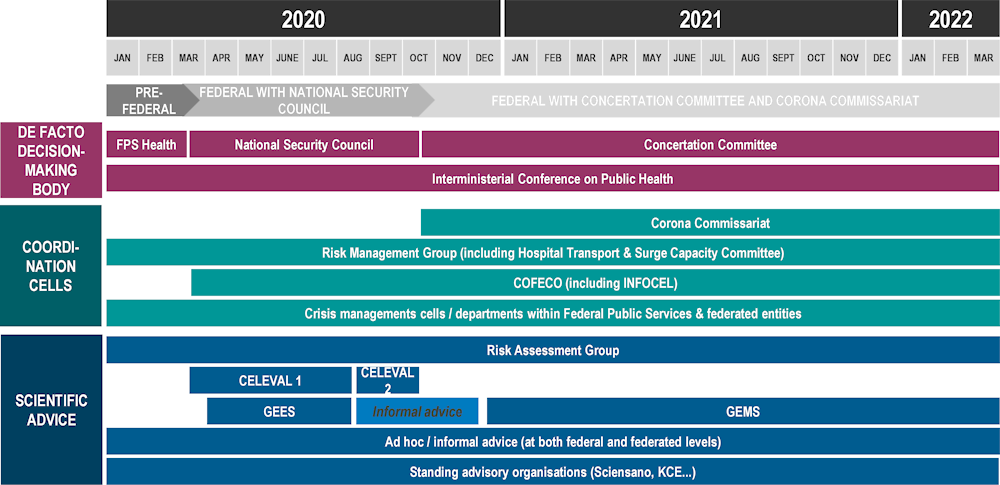

1.4.2. Overview of the governance structure of the crisis response

Following the activation of the federal phase of the crisis, Belgium’s authorities also put in place a governance structure aimed at co-ordinating the crisis response across levels of government. At the federal level, other than existing fora for high-level decision making, several ad hoc or standing co-ordination bodies and advisory groups were activated. The exact landscape of the governance of the crisis has evolved over time (see Figure 1.5 for a simplified overview of the stakeholders involved in the crisis response).

Figure 1.5. Federal structure of the crisis management

Source: OECD authors’ own elaboration based on information gathered and shared by Belgian authorities.

Overall, however, from a governance point of view, the crisis can be divided in three main phases: a pre-federal phase, a first part of the federal phase with the National Security Council (NSC) leading the crisis response, and another part of the federal phase with the Concertation Committee leading the crisis response.

The pre-federal phase was characterised by the leadership of Federal Public Service Public Health, the emergence of the virus being first and foremost seen as a public health crisis. During this phase, the FPS Health was in charge of co-ordinating the crisis response. It was helped in this mission by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which was in charge of repatriating Belgian citizens located in areas where the virus spread, as well as by the National Crisis Centre (NCCN). The pre-federal phase ended on 12 March 2020, when the federal phase was officially activated by the Ministry of Interior, as is his mandate according to the 2003 Royal Decree Establishing the emergency plan for events and crisis situations requiring national co-ordination or management (Belgian Official Journal, 2003[18]).

During first part of the federal phase, the crisis response was co-ordinated by the National Security Council, which was led by the Prime Minister and to which the Minister Presidents of the federated entities were invited. This phase saw the creation of ad hoc structures seeking to assist the executive in tackling this new virus. This phase ended on 1 October 2020, when a new government was formed.

The second part of the federal phase of the crisis was mainly led by the Concertation Committee, a body in which the Prime Minister and the Minister Presidents hold equal decision-making power. This phase also saw the creation of a Corona Commissariat, which sought to clarify the overall governance structure and centralise the crisis response in a single delivery unit. In the context of this evaluation, this phase ended on 14 March 2022, although the Commissariat was only disbanded on 8 April 2022.

The main bodies involved during the period of January 2020 to March 2022, their composition and mandates are further described in Annex 1.A.

1.5. What key lessons from the evaluation of Belgium’s COVID-19 responses?

These anticipation and co-ordination efforts, which are detailed in Chapters 2 and 3 respectively, were complemented by measures aimed at mitigating the impacts of the COVID-19 crisis across various policy domains, including:

public health (e.g. through the development of rapid and efficient tracing and vaccination campaigns, surge capacity, etc.)

education (e.g. ensuring learning continuity through digital tools and keeping schools open)

economic and fiscal measures (e.g. through tax and social security deferrals and cancellations, employment support, temporary suspension of insolvency procedures, grants, loans and guarantees on loans to businesses)

and labour market and social policies (e.g. by expanding existing schemes for job retention support and income replacement for the self-employed, raising the payment levels of unemployment and minimum‑income benefits, and providing financial support to welfare offices for the delivery of social services for the most vulnerable).

The main findings pertaining to each of these thematic policy responses are detailed in chapters 4 to 7 of this report and are summarised in the box below. In addition, because the COVID-19 pandemic was a complex crisis characterised by strong interactions and trade-offs between policy fields, this evaluation also draws transversal lessons on three key issues of importance to the crisis:

The proportionality of the measures adopted during the crisis.

The extent to which the measures adopted in Belgium managed to preserve citizen’s quality of life, including their mental health.

The impact of the crisis on vulnerable groups such as youth and the elderly.

These three key issues are thus examined across several chapters of this evaluation. For instance, the issue of citizen’s quality of life is assessed from a health (which is the focus of Chapter 4) and social (which is the focus of Chapter 7) perspective, but also in terms of the extent to which school closures and remote learning had an impact on parents, teachers and students (this issue is discussed in Chapter 5). This multidisciplinary approach aims to enrich the available evidence base in under explored areas of the COVID response.

1.5.1. The proportionality of measures adopted during the crisis

As early as 2007, the World Health Organisation (WHO) highlighted proportionality as one of the ethical principles that governments should pay attention to when applying isolation, quarantine, border control and social-distance measures to tackle influenza (World Health Organisation, 2007[33]). The WHO defined proportionality as:

“a requirement for a reasonable balance between the public good to be achieved and the degree of personal invasion. If the intervention is gratuitously onerous or unfair it will overstep ethical boundaries”.

In a fast-changing context such as the COVID-19 pandemic, where little evidence is available ex ante on the benefit/risk analysis of measures, proportionality is naturally difficult to achieve. Yet, on the other hand, broader and more stringent restrictions on individual liberties for the public good, albeit temporary, call for greater attention to this principle.

In Belgium, data shows that overall, measures in the country were similar or less stringent on individual freedoms that in other countries (Hale et al., 2021[34]). For instance, Belgium is one of the OECD countries where schools were closed the least throughout the duration of the pandemic (see Chapter 5).

On the other hand, following an initial period of exceptional powers between 30 March 2020, and 29 June 2020, the government did continue to restrict freedom of movement through simple ministerial decrees. The fact that such restrictions to fundamental freedoms were taken on the basis of regulation (mostly by the Ministry of Interior), that is, without the involvement of Parliament (either ex ante through Parliamentary voting procedures or ex post through Parliamentary control), raised questions in public debate. Indeed, democratic accountability is an essential safeguard of the proportionality principle.

In Belgium, the Council of State, the highest administrative court in the country, confirmed these ministerial decrees under emergency procedure, as did the Constitutional Court and the Court of Cassation (Belgian Council of State, 2020[35]; Belgian Council of State, 2021[36]). These courts render their opinion also in light of the proportionality principle, meaning that they have deemed these ministerial decrees to be proportionate to the situation and the goal at end – thus that they preserved the public good. Still, to provide a more robust legal underpinning to these restrictions of freedom, the Belgian government developed a “pandemic law” (Law relating to administrative police measures during an epidemic emergency situation), adopted by Parliament on 15 July 2021 (Belgian Official Journal, 2021[37]). This law gives a greater role to Parliament in holding the executive to account during future pandemics and is a step in the right direction in regard to the preservation of the proportionality principle during times of crises. Belgium may wish to consider the opportunity of adopting another law, which explicitly envisages other forms of crises that could require such restrictions to individual freedoms.

1.5.2. The impact of the crisis on citizens’ quality of life

From lockdowns to school closures and other restrictions, quality of life was strongly impacted throughout the crisis. The pandemic took a significant toll on mental health of the Belgian population, and in 2022, 15% of Belgians reported symptoms of depression and 17% symptoms of anxiety, well above pre-pandemic levels. While numbers are not comparable across countries, all surveyed OECD Member States saw numbers above pre-pandemic levels (OECD, 2023[38]). This toll has been proven to be even more important for the most vulnerable populations, as well as certain categories of professionals who were at the front line of the crisis response. Indeed, the crisis particularly impacted the mental health of health-care professionals. For example, the OECD Survey of General Practitioners found that, of the 17% of respondents reporting having sought mental health support during the pandemic, 81% had not previously sought it recently prior to the pandemic. Mental health was also an important challenge for teachers, students and parents. During the pandemic, young adults (age 18-29) are the age group that reported the highest prevalence of depressive symptoms in Belgium (Sciensano, 2023[39]).

To address the situation, authorities across the country in Belgium worked to maintain continuity of mental health care and expand access to psychosocial services. For instance, health authorities at the Interministerial Health Conference agreed to include 20 visits with a psychologist for an out-of-pocket cost of EUR 11 per session. Similarly, to respond to the stresses of school closures, all three Belgian Communities put in place hotlines, adapting curriculums, or additional funding to student guidance centres for the detection of students with special needs or extra care.

On the other hand, the pandemic also had an overall balanced impact on household income, another factor of quality of life. This impact on income was fairly balanced. Unemployment increased at the onset of the pandemic and has remained above its 2019 Q4 level as well as the OECD average by the end of 2022, yet Belgian households also accumulated excess savings during that period due to decreased consumption.

1.5.3. The impact of the crisis on vulnerable groups

Throughout OECD countries, the most vulnerable groups were hit the hardest by the pandemic, whether due to confinement measures or to greater risks related to COVID-19.

While Belgium managed to prevent major job and income losses during the crisis for most people, unemployment did rise. In particular, job losses were concentrated among workers on temporary contracts including young people and migrants, who often did not qualify for job retention support. Flat receipt rates of unemployment benefits, and an only modest rise in the receipt of social assistance benefits, indicate that these workers often did not receive any income support. In addition, prior to the crisis, Belgian authorities had a limited ecosystem to identify and help vulnerable groups. This led for example to difficulties to identify homeless people or undocumented immigrants and provide them with support throughout the crisis, especially during lockdowns. As a result, Belgian authorities relied on civil society organisations to best relay measures and campaigns to isolated groups during the pandemic, although these efforts were overall limited. Belgium provided direct support to municipal welfare offices, amounting to EUR 135 million until June 2021, to support the provision of social services. However, in the absence of clear guidance and support on how to use these funds, welfare offices particularly in smaller communities may have lacked the capacity to use them effectively.

Older populations, especially those in long-term care facilities, were also particularly hard hit by the COVID-19 pandemic: nearly half (45%) of all COVID-19 deaths in Belgium were among residents of nursing homes between March 2020 and September 2022. Nursing home residents also comprised nearly three in five deaths (57%) in 2020. Despite being the age category with the highest levels of COVID-19 vaccination, the proportion of all COVID-19-related deaths impacting older populations has not changed substantially over the course of the pandemic. Older populations also suffered from challenges related to isolation and mental health.

Finally, young people in Belgium, as is the case across OECD Member countries, have suffered from a disproportionate impact of the pandemic on their mental health. Specifically, school closures and restrictions in gatherings impacted youths. Learning discontinuity happened despite schools having been closed for less time than in most other European countries. To combat this impact, federated entities sought to prioritise students’ well-being, for instance by opening several hotlines to offer mental and well-being support to students and their parents.

Key findings of the report and areas of focus for the future

Four years after the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the time is still right to learn lessons from this major crisis to better understand what worked, what did not, for whom, and why, in order to increase countries’ resilience to future complex crises. Evaluations such as this one can also promote transparency towards citizens on the choices made by decision-makers during the crisis, and as such, contribute to wider efforts to promote trust in government. In a multi-cultural and highly decentralised federated country such as Belgium, where levels of trust in public institutions are low, evaluations of COVID-19 responses are crucial to reflect on the past with the aim of strengthening the foundations of society.

In this context, this evaluation looks at the full range of measures adopted in Belgium throughout the risk management cycle, from crisis preparedness and management measures to response and recovery efforts related to health, education, economic and fiscal affairs, and social and labour market policies. Within this framework, this report draws the following main conclusions:

A number of weaknesses in risk anticipation and pandemic preparedness complicated Belgium’s early response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Belgium was able to adopt a whole-of-government response to the pandemic despite the multiplicity of its institutional structures.

While Belgium fared poorly on direct and indirect health indicators during the first year of the pandemic, its health system was able to respond fairly robustly and to adapt over the course of the pandemic, leading to an improved response in 2021 and 2022. The quick roll out of the vaccination campaign and a tightly organised hospital response helped prevent hospitals from becoming overwhelmed during the crisis.

The Belgian education systems withstood significant challenges and were able to ensure pedagogical continuity, although the crisis response could have better supported students and education actors involved in their learning.

Support to households and businesses was sufficient to avoid a wave of bankruptcies and job losses but had a large direct impact on spending and could have been better targeted.

Belgium was able to quickly roll out social protection schemes and provide a first line of defense against pandemic-related income losses. However, these schemes did not reach everyone to the same extent and workers with shorter employment records and those with insufficient contributions to qualify for unemployment benefits, were left uncovered.

Looking to the future, Belgian authorities may wish to:

Improve anticipation and preparedness to complex crises. In particular, strengthening the overall national risk management system across all levels of government will be key to increasing Belgium’s future preparedness.

Strengthen the use of data and evidence for decision-making, in part by structuring a robust and credible system to provide multidisciplinary science advice in times of crisis, and by facilitating data exchanges between levels of government.

Clarify national co-ordination mechanisms in times of crisis, for instance by improving co-operation on matters where different levels of government have competencies and strengthening the whole-of-government nature of the crisis management system.

Preserve the fiscal balance by making greater use of liquidity measures and better targeting direct support.

Continue addressing educational and socioeconomic inequalities, for instance by easing access to unemployment benefits for workers with short contribution histories, and fostering teachers’ and students’ digital literacy.

Promote trust in public institutions to build societal resilience, such as by clarifying the role of science in decision-making and better engaging citizens in the design and implementation of policies.

References

[1] Belgian Chamber of Representatives (2021), Commission Spéciale chargée d’examiner la gestion de l’épidémie de COVID-19 par la Belgique, https://www.lachambre.be/FLWB/PDF/55/1394/55K1394002.pdf.

[36] Belgian Council of State (2021), Arrêt no 249 723 du 4 février 2021.

[35] Belgian Council of State (2020), Arrêt no 248 918 du 13 novembre 2020.

[37] Belgian Official Journal (2021), 14 août 2021 - Loi relative aux mesures de police administrative lors d’une situation d’urgence épidémique.

[40] Belgian Official Journal (2015), 28 janvier 2015 - Arrêté royal portant création du Conseil national de sécurité.

[18] Belgian Official Journal (2003), 31 janvier 2003 - Arrêté royal portant fixation du plan d’urgence pour les événements et situations de crise nécessitant une coordination ou une gestion à l’echelon national.

[41] Belgian Official Journal (1988), 18 avril 1988 - Arrêté royal portant création du Centre gouvernemental de Coordination et de Crise.

[15] Belgian Official Journal (1980), 8 août 1980 - Loi spéciale de réformes institutionnelles.

[16] Belgium.be (n.d.), About Belgium/Government, https://www.belgium.be/en/about_belgium/government (accessed on 12 November 2023).

[4] Brussels’ Parliament (2021), Propositions de recommandations de la commission spéciale COVID-19.

[17] Di Rupo, E. (2011), Un État fédéral plus efficace et des entités plus autonomes.

[21] Gugushvili, D. et al. (2023), How satisfied are Belgians with the government’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic? Evidence from the European Social Survey.

[34] Hale, T. et al. (2021), “A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker)”, Nature Human Behaviour, Vol. 5/4, pp. 529-538, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01079-8.

[19] Jousten, A. and C. Behrendt (2022), “Fonctionnement des Parlements belges en période de confinement et de distanciation sociale”, Le droit public belge face à la crise du COVID-19, pp. 225-256.

[31] Jurcevic, J. et al. (2023), Epidemiology of COVID-19 mortality in Belgium from wave 1 to wave 7 (March 2020 – 11 September 2022), Sciensano, https://www.sciensano.be/en/biblio/epidemiology-covid-19-mortality-belgium-wave-1-wave-7-march-2020-11-september-2022.

[30] Königs, S., A. Vindics and M. Diaz Ramirez (forthcoming), “The geography of income inequalities in OECD countries - Evidence from national register data.”, OECD Social Employment and Migration Working Papers.

[28] OECD (2023), Government at a Glance 2023, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/3d5c5d31-en.

[38] OECD (2023), Health at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/7a7afb35-en.

[11] OECD (2023), OECD Survey of Belgian general practitioners in the context of the Evaluation of Belgium’s COVID-19 responses.

[12] OECD (2023), OECD survey of Belgian hospitals in the context ofthe Evaluation of Belgium’s COVID-19 responses.

[10] OECD (2023), OECD Survey of Belgian municipalities in the context of the Evaluation of Belgium’s COVID-19 responses.

[13] OECD (2023), OECD Survey of primary and secondary schools in the context of the Evaluation of Belgium’s COVID-19 responses.

[20] OECD (2022), Building Trust to Reinforce Democracy: Main Findings from the 2021 OECD Survey on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions, Building Trust in Public Institutions, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b407f99c-en.

[26] OECD (2022), Education at a Glance 2022: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/3197152b-en.

[9] OECD (2022), Evaluation of Luxembourg’s COVID-19 Response: Learning from the Crisis to Increase Resilience, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/2c78c89f-en.

[6] OECD (2022), “First lessons from government evaluations of COVID-19 responses: A synthesis”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/483507d6-en.

[27] OECD (2022), OECD Economic Surveys: Belgium 2022, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/01c0a8f0-en.

[14] OECD (2021), Applying Evaluation Criteria Thoughtfully, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/543e84ed-en.

[22] OECD (2021), Health at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ae3016b9-en.

[29] OECD (2020), OECD Economic Surveys: Belgium 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1327040c-en.

[24] OECD (2019), Working Better with Age, Ageing and Employment Policies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c4d4f66a-en.

[7] OECD (2015), The Changing Face of Strategic Crisis Management, OECD Reviews of Risk Management Policies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264249127-en.

[8] OECD (2014), “Recommendation of the Council on the Governance of Critical Risks”, OECD legal Instruments, OECD/LEGAL/0405, OECD High Level Forum on Risk, Adopted by Ministers on 6 May 2014, https://www.oecd.org/gov/risk/Critical-Risks-Recommendation.pdf.

[25] OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2021), Belgium: Country Health Profile 2021, State of Health in the EU, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/57e3abb5-en.

[23] OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2019), Belgium: Country Health Profile 2019, State of Health in the EU, OECD Publishing, Paris/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Brussels, https://doi.org/10.1787/3bcb6b04-en.

[3] Parlament der Deutschsprachigen Gemeinschaft Belgiens (2022), Beschluss zur einsetzung eines sonderausschusses zur aufarbeitung der Covid-19-pandemie und der folgen der diesbezüglich getroffenen massnahmen in der Deutschsprachigen Gemeinschaft.

[2] Parlement Wallon (2020), Rapport de la Commission spéciale chargée d’évaluer la gestion de la crise sanitaire de la Covid-19 par la Wallonie.

[39] Sciensano (2023), Belgium COVID-19 Epidemiological Situation: Mental Health Studies (database), https://lookerstudio.google.com/embed/u/0/reporting/7e11980c-3350-4ee3-8291-3065cc4e90c2/page/ykUGC (accessed on 14 August 2023).

[32] Sciensano (2023), COVID-19 epidemiological situation, https://epistat.sciensano.be/covid/ (accessed on 19 May 2023).

[5] Vlaams Parlement (n.d.), Dossier Corona, https://www.vlaamsparlement.be/nl/parlementair-werk/dossiers/dossiers/corona (accessed on 31 October 2023).

[33] World Health Organisation (2007), Ethical Considerations in Developing a Public Health Response to Pandemic Influenza, https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/70006/WHO_CDS_EPR_GIP_2007.2_eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 31 October 2023).

Annex 1.A. Main stakeholders involved in the crisis

The crisis saw a wide array of bodies and groups having some level of responsibility in the anticipation of, preparedness to, and management of the crisis. Key bodies that are referred to throughout the chapters of the present evaluation are defined in the following section.

FPS Health

The Federal Public Service Health, Food Chain Safety and Environment (hereafter FPS Health) is a public service of Belgium, representing the administrative side of the Ministry of Health. It focuses on healthcare, animal and plant health, and environmental health. FPS Health went through a reorganisation before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, which saw the extinction of the Directorate in charge of emergencies, which also focused on crisis management. This reorganisation reduced FPS Health’s capacity to tackle crises. Before the federal phase was activated, FPS Health was in charge of alerting on and managing the crisis.

Risk Management Group and Risk Assessment Group

Articles 5 and 7 of the Protocol of 5 November 2018, on Establishing the generic structures for the health sector management of public health crises and their mode of operation for the application of the International Health Regulations (2005), and decision no. 1082/2013/EC relating to serious cross-border threats to health, establish formally the Risk Management Group (RMG) and the Risk Assessment Group (RAG). As standing bodies, the RMG and RAG have been associated to the management of the crisis since its very first days.

The RMG is described, amongst others, as the “decision-making and notification forum for public health emergencies”, as well as a “starting point for (inter)nationally co-ordinated risk management if necessary”. The RMG is chaired by a national focal point, who works at the FPS Health. It is composed of one or two delegates from cabinet and the administration for each federated entity, the federal level, and the COCOM.

The RAG is described as the Belgian forum in charge of analysing and scrutinising potential signals, risks or events having, amongst others, an impact on public health. It is also in charge of proposing measures and give recommendations based on epidemiological and scientifical data to the RMG. The RAG is chaired by Sciensano, the national public health institute, and is composed of several experts from each federated entity, the COCOM, the national focal point and chair of the RMG, and a representative of the Health Superior Council.

Task Forces and the Hospital Transport & Surge Capacity Committee

Several task forces have been created to answer to different aspects of the pandemic response. Their goal was mainly to develop recommendations on specific topics. The Task Forces on Testing, Hospital & Transport surge Capacity, Vaccination, Ventilation, Testing, Primary & Outpatient Care Surge Capacity, amongst others, were not always hosted by or answered to the same entity.

The Hospital Transport & Surge Capacity Committee played a key role in the health response to the crisis, by both monitoring the number of patients in hospitals, and manage the flow of patients throughout the crisis. This task force was co-ordinated by the FPS Public Health but was giving advice to the RMG.

National Security Council