Managing a complex multidisciplinary crisis of the likes of the COVID-19 pandemic calls for a whole-of-government and whole-of-society response, maintaining trust in public action and preserving democratic continuity. This chapter assesses the extent to which crisis governance structures and mechanisms enabled Belgium to develop a co-ordinated and agile response to the pandemic. It also looks at the effectiveness of crisis communication. Finally, the chapter examines the extent to which the government was able to foster a whole-of-society response to the crisis and maintain democratic accountability channels.

Evaluation of Belgium’s COVID-19 Responses

3. The management of the COVID-19 crisis in Belgium

Abstract

Key findings

The OECD’s work on government evaluations of COVID-19 responses has identified crisis management related measures as being one of the three types of measures countries should assess to best learn from the crisis (OECD, 2022[1]). For the purposes of this evaluation, crisis management refers to the policies and actions taken to co-ordinate government action across and within levels of government, to communicate to the public, as well as to involve the whole-of-society in responding to the crisis. The crisis management measures detailed in this chapter relate to the ones taken during the federal phase of the crisis, from 12 March 2020 to 14 March 2022.

In Belgium, the governance of crisis management suffered from a multiplicity of actors involved in the early stages of the pandemic but evolved over time to adapt to the changing needs of the crisis and to better involve federated entities in decision making at the centre. Co-ordination within levels of government mostly worked well, even though the multiplicity of ad hoc bodies at the federal level created challenges relating to blurred lines of responsibility and overlapping mandates. While important efforts were made to ensure the multidisciplinary of advisory bodies, increased transparency on internal decision-making processes and conflicts of interest would have been needed to strengthen the transparency and legitimacy of scientific advice.

Crisis communication remained overall coherent throughout the crisis. The country’s political leadership appeared frequently in the media to share information about the evolution of the virus and the measures taken by the government in response to it. Efforts taken to monitor trust levels and the impact of communication helped better tailor communication messages, which were communicated widely through different channels and tools. However, these messages suffered at times from the fact that each level of government had their own communication campaigns and used different channels or tools. Moreover, vulnerable and minority groups were not sufficiently targeted, as was the case in many OECD countries.

Finally, Belgium made efforts to develop a whole-of-society response to the pandemic and to preserve democratic accountability during the crisis. The recent adoption of a pandemic law and the numerous evaluations already conducted in Belgium on this topic are contributing to reinforcing democratic accountability. Still, this whole-of-society approach could have been strengthened by further involving civil society organisations both in scientific advice and in some crisis management bodies.

3.1. Introduction

This chapter focuses on the federal crisis management phase, which covers the policies and actions implemented by the government in response to the pandemic, i.e., once it had become a reality. “Crisis management” hereafter thus refers to the capacity of government to react appropriately and at the right time, while ensuring co-ordination across government and the whole-of-society. In Belgium, this phase officially began for the whole of the country with the declaration of the so-called “federal phase of the crisis”, on 12 March 2020 (Belgian Official Journal, 2003[2]). Given that this phase is by definition one in which the federal government co-ordinates the crisis response, this chapter mainly looks at how the crisis was managed by the federal government, as well as the extent to which federal-level policies impacted, and required co-ordination with, the federated entities.

The management of modern and complex crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, involves a wide variety of actors beyond traditional emergency services and risk management units. As a result, increased co-ordination across all levels of government and sections of society is essential to managing the crisis and its many impacts. This type of crisis also requires the government to maintain public trust, for instance through public communication, both to ensure the effectiveness of the measures adopted to mitigate the effects of the crisis, as well as to maintain margin for manoeuvre for action in the future. Finally, the impact that large-scale crises can have on the public's trust in public institutions requires that governments increase their efforts to ensure the continuity of democratic life and to demonstrate the integrity, legitimacy and robustness of their decisions.

These issues, while undeniably heightened during the COVID-19 crisis, are not new. As early as 2014, the OECD Recommendation required governments to make appropriate arrangements to manage risks and crises while co-ordinating across government, including with sub-national entities; to ensure transparent and meaningful crisis communication; and to enable a society-wide response to hazards and threats (see Box 3.2).

Box 3.1. The OECD Recommendation on the Governance of Critical Risks

The OECD Council adopted the Recommendation on the Governance of Critical Risks (hereinafter the “OECD Recommendation”) in 2014. An OECD Council Recommendation is one of the several legal instruments the OECD can develop and represents a political commitment to be reached by all OECD Member countries. The High-Level Risk Forum (HLRF) was instrumental in the development of this Recommendation. Since its adoption, 41 countries have signed up to the Recommendation, including Belgium as a Member country of the OECD.

The Recommendation focuses on critical risks, i.e., “threats and hazards that pose the most strategically significant risk, as a result of (i) their probability or likelihood and of (ii) the national significance of their disruptive consequences, including sudden onset events (e.g. earthquakes, industrial accidents or terrorist attacks), gradual onset events (e.g. pandemics) or steady-state risks (those related to illicit trade or organised crime).” The Recommendation is based on the principles of good risk governance that have enabled many Member countries to achieve better risk management outcomes.

The Recommendation proposes that governments:

identify and assess all risks of national significance and use this analysis to inform decision making on risk management priorities (see Chapter 2 of this report).

put in place governance mechanisms to co-ordinate on risk and manage crises across government, including with sub-national entities.

ensure transparency around and the communication of information on risks to the public before a risk occurs and during the crisis response.

work with the private sector and civil society, and across borders through international co-operation, to better assess, mitigate, prepare for, respond to and recover from critical risks.

Source: OECD (2014[3]), “Recommendation of the Council on the Governance of Critical Risks”, OECD Legal Instruments, OECD/LEGAL/0405, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0405.

In line with this Recommendation, as well as the OECD framework on ‘Evaluating COVID-19 responses’ (OECD, 2022[1]) (see also Chapter 1), this chapter examines the extent to which the governance arrangements put in place in Belgium to manage the crisis enabled the government to adopt a co-ordinated and agile response to the pandemic. It also offers a look at the use of scientific expertise for crisis management in Belgium. The chapter then examines the strategies used by the government to communicate to citizens, in terms of both the relevance and the coherence of the messaging. Finally, the chapter looks at the measures adopted by the Belgian governmental entities at federal and federated levels to maintain the continuity of democratic life and involve society as a whole in the crisis response. The ways in which risks are identified and anticipated in Belgium are discussed in Chapter 2 of this report.

3.2. The governance of crisis management of the COVID-19 crisis in Belgium

According to the terminology adopted by the OECD, the crisis phase officially begins when a significant threat is clearly announced and anticipated, or when an undetected event causes a sudden crisis (OECD, 2015[4]). In Belgium, public health emergencies capabilities monitored the situation and took early actions to address the first cases of COVID-19, as detailed in Chapter 2. However, a broader response to disaster risk occurred with the whole-of-government federal phase of the crisis. The whole-of-government framework for crisis management is regimented by the Royal Decree of 31 January 2003, later on amended in 2006 and 2019, which identifies three levels of crisis, by increasing degrees of threat (Belgian Official Journal, 2003[2]):

A municipal phase, corresponding to an emergency or threat that can be co-ordinated at the local level and remain within the purview of the municipalities.

A provincial phase, corresponding to an emergency or threat that can be co-ordinated at the provincial level and requires escalating the management of the crisis to the governors of the provinces.

A federal phase, corresponding to threats and emergencies that require crisis co-ordination at the national level, with the responsibility for co-ordinating crisis management being given to federal authorities. The federal phase is officially launched by the Minister of Interior, when at least one of the conditions detailed below is met (Box 3.2). Unlike in other OECD countries, such as France or Luxembourg, the identification of a (federal) “crisis phase” under the Royal Decree of 2003 in Belgium is not associated with the attribution of exceptional powers to the executive.

Box 3.2. Activation of a federal phase of crisis management in Belgium

Following the Royal Decree of 31 January 2003 on Establishing the emergency plan for events and crisis situations requiring national co-ordination or management and the Royal Decree of 22 May 2019 on Emergency planning and management of emergency situations at municipal and provincial level and the role of mayors and provincial governors in the event of events and crisis situations requiring co-ordination or management at the national level, the activation of a federal phase of a crisis belongs to the Minister of Interior, in consultation with other Ministers affected and governors.

This decision is based on several indicative criteria:

two or more provinces or the entire national territory are concerned

the means to be implemented exceed those available to a provincial governor as part of his co-ordination mission

threat or presence of numerous victims (wounded, killed)

occurrence or threat of major effects on the environment or food chain

damage or threat of damage to the vital interests of the nation or the basic needs of the population

the need to implement and co-ordinate the various federal government departments or agencies

need for general information to the entire population.

The COVID-19 crisis therefore combined several criteria justifying the activation of a federal phase of crisis management. The activation of a federal phase leads to the activation of three bodies within the National Crisis Centre: an evaluation cell (CELEVAL), presided by the head of the most relevant department, a management cell (COFECO), presided by the Minister of Interior or its replacement, and an information cell structured by the National Crisis Centre (INFOCEL).

Source: Belgian Official Journal (2003[2]), Royal Decree of 31 January 2003 establishing the emergency plan for events and crisis situations requiring national co-ordination or management; Royal Decree of 22 May 2019 on emergency planning and management of emergency situations at municipal and provincial level and the role of mayors and provincial governors in the event of events and crisis situations requiring co-ordination or management at the national level.

The federal phase of the crisis was officially declared in Belgium on 12 March 2020, as a result of several weeks of preparatory work and discussions, as well as interministerial meetings, which had taken place since 24 January 2020. The federal phase ended to 14 March 2022. As this chapter focuses on the federal phase of the crisis, this section examines mostly the federal level governance mechanisms. Crisis response at subnational level is analysed to the extent it required interaction or co-ordination with federal entities.

In the face of a crisis, the OECD Recommendation stresses the importance of putting in place governance mechanisms to co-ordinate on risk and manage crises across government. In particular, the Recommendation advises that Members:

Assign leadership at the national level to drive policy implementation and designate an authority in charge of drawing on and co-ordinating sufficient resources to manage civil contingencies.

Establish specific structures to ensure interministerial co-operation and to facilitate agile implementation, including by engaging sub-national levels of government.

Activate or create mechanisms to gather expert advice on the pandemic.

This section of the chapter looks at how the Belgian authorities used these three types of mechanisms, as well as the extent to which they were able to cope with the complex and changing nature of the crisis.

3.2.1. The institutional and personal leadership of the crisis in Belgium

Leadership is at the centre of effective crisis management. Such leadership is essential to facilitate co-operation and decision making across government and with external stakeholders, but it also plays a key role in crisis communication by helping to build trust in those managing the crisis. Therefore, crisis leadership is twofold: it can be institutional, that is having an institution or authority with an explicit mandate enabling it to drive the crisis response, and personal, that is having one or several clearly identified decision maker(s) in charge of leading the crisis response. The need for both of these aspects is clearly underlined by the OECD Recommendation, which advises adherents to (OECD, 2014[3]):

"Assign leadership at the national level to drive policy implementation, connect policy agendas and align competing priorities across ministries and between central and local government through the establishment of multidisciplinary, interagency-approaches (e.g., national co-ordination platforms) that foster the integration of public safety across ministries and levels of government.”

“[Designate] an authority in charge of drawing on and coordinating sufficient resources to manage civil contingencies, whether from departments and agencies, the private sector, academia, the voluntary sector or non-governmental organisations.”

In Belgium, personal leadership was ensured at the highest level of government by the heads of the executives throughout the crisis. However, in the initial months of the pandemic, the National Crisis Centre (hereafter, the NCCN) and the Federal Public Service Health did not play a strong institutional role in leading the crisis response, despite having the legal mandate to do so, which may have led to important inefficiencies in the co-ordination of the crisis response.

The creation of the COVID Commissariat in October 2020, a unit headed by a Commissioner and backed by the Prime Minister’s Office and the Health Minister’s Office, more clearly articulated the national response to the pandemic. In this context, the following paragraphs examine the extent to which the leadership of the crisis in Belgium, both from an institutional and personal standpoint, facilitated decision making across government and promoted trust in the crisis response.

Personal leadership was embodied at the highest level of government

Personal leadership has a key role in ensuring that crisis management is personified in the eyes of the public and in driving a whole-of-society response. Indeed, personal leadership is essential to the meaning-making functions of crisis management, as it provides the public with a coherent narrative for the crisis response, as well as personifies the response. In many OECD countries, personal leadership for the crisis was provided for by a political figure and/or a scientist or senior level public servant (such as the head of the crisis management agency in Luxembourg, for example) (OECD, 2022[5]). For example, in New Zealand, the daily briefings of the Prime Minister and the Director-General of Health greatly demonstrating clear personal leadership. The communication type it enabled has been described as (1) open, honest and straightforward, (2) using motivational language, and (3) using expressions of care (Beattie and Priestley, 2021[6]). Such leadership can be even more important in federal states where competencies are shared between levels of government that do not have constitutional authority over one other, as it can create a common figure or narrative to rally forces around.

In Belgium, personal leadership was embodied at the highest level of government throughout the duration of the crisis. First, the National Security Council (NSC) provided leadership during the initial few months of the federal phase and served as a forum for co-ordination between the different entities composing the federal government. Personal leadership was embodied in the fact that the Minister Presidents and the Prime Minister of Belgium systematically participated in the NSC meetings. Following October 2020, the Concertation Committee (CC) played the central role in representing the political face of the crisis and the interfederal nature of the crisis response. In addition to the CC, the federal Minister of Health also took on a more public facing role starting in October 2020, which was well received by the public (Motivation Barometer, 2020[7]). Joint press interventions by the Minister Presidents and the Prime Minister throughout the pandemic served to reinforce an image of joint leadership by the heads of the executives of the various entities in this federal state.

This political leadership from the Centre of government is essential to maintaining citizens' trust in government in the context of infringements (albeit temporary) to fundamental freedoms for the purpose of mitigating the effects of a crisis. This is why, in the future, Belgium could consider continuing to communicate at the level of the CC in times of crises that require the involvement of both federal and federated entities to highlight clear leadership from all levels of government.

Institutional leadership was overall lacking in the early phases

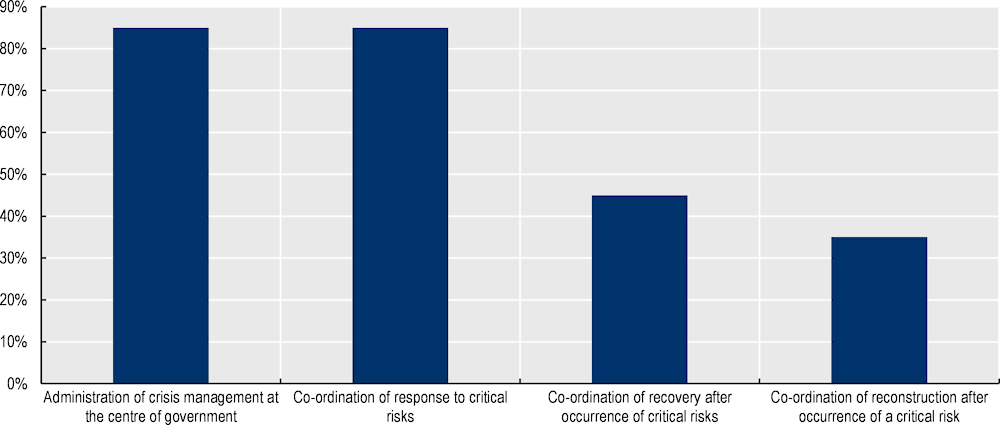

Institutional leadership at the national level is also needed to facilitate co-operation across stakeholders, mobilise resources for the crisis response and ensure that stakeholders have the capacity to fulfil their risk management responsibilities. In practice, such leadership translates into the designation of a national institution with the responsibility to spearhead critical risk governance throughout the entire disaster risk management cycle. Indeed, the OECD Recommendation calls countries to identify bodies able to drive policy implementation, connect policy agendas and align competing priorities across ministries and between central and local government (OECD, 2014[3]). Most OECD countries rely on a central government institution or body to co-ordinate government stakeholders in the management of risks (OECD, 2022[8]). This is the case of Belgium with the NCCN, Luxembourg with the High Commission for National Protection or the United States with the Federal Emergency Management Agency. Overall, the results of the 2022 OECD survey on critical risk governance show that a majority of OECD Member countries (20 out of 25 respondents, including Belgium) designate such a lead institution from within their central government, although the roles assigned to them vary considerably from country to country (see Figure 3.1) (OECD, 2022[8]).

Figure 3.1. Lead institutions and their mandates

Percentage of OECD countries where a central government institution or body has some responsibilities to co-ordinate management of critical risks

In Belgium, it is the NCCN that had a mandate to co-ordinate a multidisciplinary crisis response. The Royal Decree of 18 April 1988, states that the role of the NCCN is “to provide the competent authorities with the infrastructure and resources necessary for the management of such a crisis, and in particular to ensure co-ordination, the preparation of decisions, their possible execution and their follow-up". As a result, the NCCN would have been well positioned to play a leadership role in the crisis response, from an institutional point of view. The NCCN is aided in its role as the main crisis management agency at the federal level by governors. The Royal Decree of May 22, 2019, highlights the role of governors during municipal, provincial and federal phases (Belgian Official Journal, 2019[9]). During the federal phase of a crisis, governors are supporting the federal co-ordination by implementing decisions on their territory when necessary, and they can take temporary measures to limit the consequences of the crisis as long as the Minister of Interior is informed. The regional crisis cells of Flanders and Wallonia also provide regional contact points to the NCCN, although the role of Flanders’ has historically been more focused on crisis co-ordination and communication, and Wallonia’s on crisis anticipation, preparedness and support (Vlaamse overheid, n.d.[10]) (Géoportail de la Wallonie, n.d.[11]).

In addition, given the nature of the crisis, the federal Minister of Health and their cabinet, as well as the Federal Public Service Public Health (FPS Public Health, the Belgian Health Ministry), also had a key role to play in leading the pandemic response. A co-ordinated approach to health is made even more important by the multiplicity of Ministers of Health at different levels of government – eight in Belgium. First, the Royal Decree of 31 January 2003, highlights the role of the relevant policy Minister, with the Ministry of Interior, in activating the federal phase of emergency planning (Belgian Official Journal, 2003[2]). In the case of a pandemic, it is naturally the federal Minister of Health that plays this role. Second, the FPS Public Health managed the secretariat of the two bodies created to apply the World Health Organisation’s International Health Regulations (IHR) (2005), which stipulate that countries should designate a National Focal Point for IHR-related communications with the World Health Organization (WHO) and key national sectors, and the European Union’s Decision No. 1082/2013/EU on serious cross-border threats to health, which requires Member countries to support the implementation of the IHR (WHO, 2005[12]) (Official Journal of the European Union, 2013[13]). These two bodies, discussed at greater length in Chapters 1 and 2, are the Risk Management Group (RMG) and the Risk Assessment Group (RAG).

Despite the NCCN and the FPS Public Health having a clear mandate to lead the crisis response, both institutions were not able to play a strong leadership role during the COVID-19 pandemic. First, there was a discrepancy between the mandate of the NCCN and the role it played during the crisis. Indeed, the NCCN and its crisis structures were essentially bypassed when it comes to most crisis management responsibilities as of 12 March 2020. For instance, the Federal Co-ordination Committee (COFECO), a crisis body in charge of co-ordinating the overall response and presided by the NCCN, was not able to conduct preparatory work and co-ordinate the implementation of measures. This could in part be explained by the ambiguity included in the NCCN’s founding Royal Decree of 18 April 1988, on whose role exactly it is to ensure co-ordination (Belgian Official Journal, 1988[14]). Indeed, the sentence “to provide the competent authorities with the infrastructure and resources necessary for the management of such a crisis, and in particular to ensure co-ordination” in the original text does not make it clear whether the NCCN is meant merely to support the “competent authorities” in their crisis management role, or to take on the co-ordination itself.

Another reason for the NCCN not being able to act out its full mandate is that the institution was not sufficiently known by stakeholders in the field of public health, and vice versa. This can be partly explained by the lack of institutional memory, as illustrated by the fact that several key stakeholders of the COVID era were civil servants who had to be called back from retirement to lend a hand during the crisis. Perhaps most importantly, the NCCN did not have strong political backing giving it leadership over crisis management. Indeed, to be effective, this institution should have co-ordination and incentive powers to effectively oversee the process, which requires political backing (OECD, 2018[15]). Overall, these different factors limited the impact of the NCCN’s work and structures.

Similarly, as mentioned in Chapter 2, the FPS Public Health did not play its full leadership role during the crisis, for several reasons. First of all, the RMG, chaired by the FPS Public Health, was increasingly attended by a large number of stakeholders, going from a usual participation of 4 or 5 stakeholders to almost 30 stakeholders at the peak of the crisis. Those numbers differed greatly from the status of the RMG, limiting participation to two people per entity. This made discussions both complex and politicised. De facto, the RMG became a debate body rather than a decision-making one. Moreover, the FPS Public Health did have a small crisis management unit. This unit, however, mostly focused on emergency management, for instance through the 112 hotline, and did not have sufficient resources to co-ordinate a crisis of the scale of COVID-19. Both these factors diminished the role that the FPS Public Health could have played, especially in the first health-focused stage of the crisis. However, current efforts to revive a dedicated crisis cell dealing with risk anticipation and preparedness in the FPS Public Health are now taking place and should be followed closely.

The creation of the COVID Commissariat improved the articulation of the national response to the crisis

October 2020 saw the creation of a COVID Commissariat, led by a Commissioner serving as single co-ordinator for the crisis response. In doing so, Belgium took after the example of other OECD countries, such as Italy, Latvia or New Zealand that appointed a single co-ordinator or point of contact within the Prime Minister’s Office to more clearly articulate the national response to COVID-19 (OECD, 2020[16]). The choice to clearly attach the crisis response to the Centre of government, as well as the fact that the Commissariat’s mandate was explicitly included in the new government’s coalition agreement, gave the institution strong legitimacy and political backing to play a leadership role during the subsequent phases of the crisis (Belgian Federal Government, 2020[17]).

Moreover, while the Commissariat was a federal institution, it received the buy-in of the various federated entities through the CC, thus enabling it to play its leadership role and ensure stronger unity in command. The Commissariat is widely recognised by stakeholders present during the crisis as having managed to establish a clear single point of contact at the centre of government, backed by political will. Nevertheless, as will be discussed in the following sections of this chapter, challenges related to the sheer multiplicity of crisis management bodies and stakeholders, as well as timeliness of advice, did not completely disappear with the creation of the Commissariat. Moreover, while the creation of the Commissariat alleviated the challenges faced by the standing crisis institutions and structures, leadership, networks, and ultimately trust, are built over time. For this reason, Belgium should consider reinforcing its standing structures and institutions to better prepare for future crises, as opposed to resorting to ad hoc mechanisms such as that of the Commissariat.

Belgium should consider reinforcing the mandate and structures of its federal crisis management agency

In this context, looking ahead, Belgium should consider reinforcing the mandate and structures of the NCCN. First, Belgium should consider updating the Royal Decree of 18 April 1988, to lift the ambiguity on whose role exactly it is to ensure co-ordination during times of federal level crises (see previous sections). Given that such a co-ordination role would not preclude the fact that each federated entity would retain its mandate in making the policy decisions relating to the crisis management (within the context of the CC), it would be useful in the future to attribute this competency directly and explicitly to the NCCN.

In addition, beyond having a legal mandate, the effectiveness of the NCCN is directly dependent on it having political backing. For this reason, considering the current division of powers, Belgium could consider, with further careful analysis, ensuring that the head of the NCCN is appointed using a mechanism involving both federal and federated entities, such as a collaboration agreement.

Finally, the NCCN will need to strengthen its network and to build institutional knowledge in line ministries for crisis management (see also the following sections for more information on this network building). To do so, the NCCN will need to strengthen its efforts in training senior level public servants on crisis anticipation and management (see also Chapter 2 for more on this topic).

3.2.2. Mechanisms to ensure co-operation across and within levels of government, as well as the implementation of the crisis response

Co-ordination across government, including vertically with sub-national authorities, and the operationalisation of decisions into implementable actions, are crucial elements of the governance of a fit-for-purpose crisis management system. Indeed, the Recommendation calls on Adherents to complement the core capacities in crisis agencies with flexible resources that bolster resilience, enabling reaction to new, unforeseen and complex events (OECD, 2014[3]). In order to ensure such agility across government in the face of a crisis, many OECD countries have set up standing platforms or committees that bring together a wide array of government stakeholders across disciplines. This is the case with the Group of Experts on the COVID-19 Management Strategy (GEMS) in Belgium, for example, which started in December 2020. Yet, the scale of the COVID crisis meant that some countries had to complement these traditional crisis management mechanisms with new structures. In Luxembourg, for instance, the composition of the crisis unit in charge of COVID-19 had to evolve slightly twice to adapt to the scale of the pandemic (OECD, 2022[5]).

Similarly, in Belgium, the standing crisis management structures managed by the NCCN and the FPS Public Health were quickly bypassed to the benefit of new ad hoc bodies, such as the Group of Experts tasked with the Exit Strategy (GEES). The resulting multiplication of bodies with unclear mandates created challenges around attributions of lines of responsibility and the efficiency of the crisis management system. In addition, the politicisation of existing and newly created crisis management bodies led to difficulties in the operationalisation of some decisions. Nevertheless, overall, close interpersonal relationships supported the good functioning of these governance mechanisms, particularly at the sub-national level. In this context, this section examines the impact of the multiplication of ad hoc bodies, as well as co-ordination between and within levels of government.

At the federal level, the multiplication of ad hoc bodies blurred lines of responsibilities and created challenges in the implementation of policy decisions

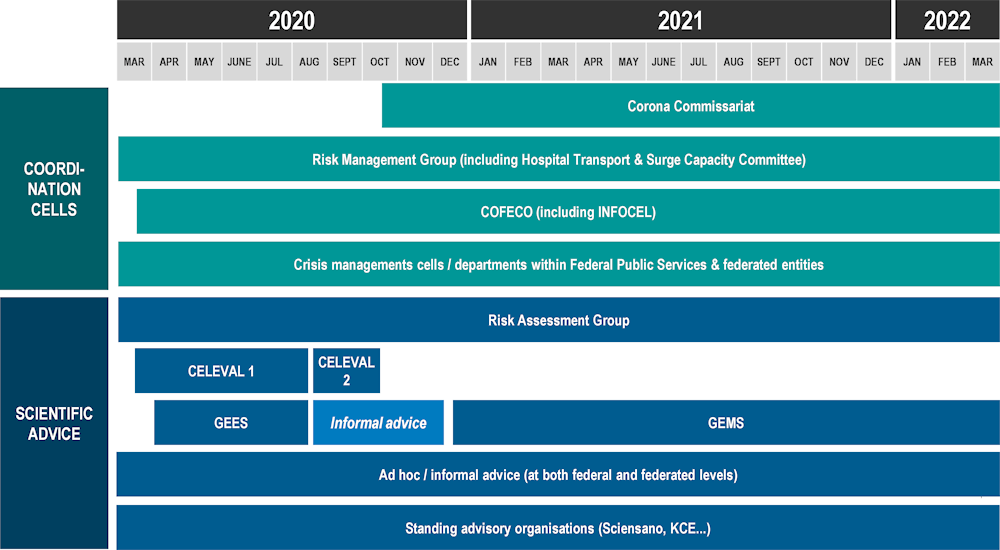

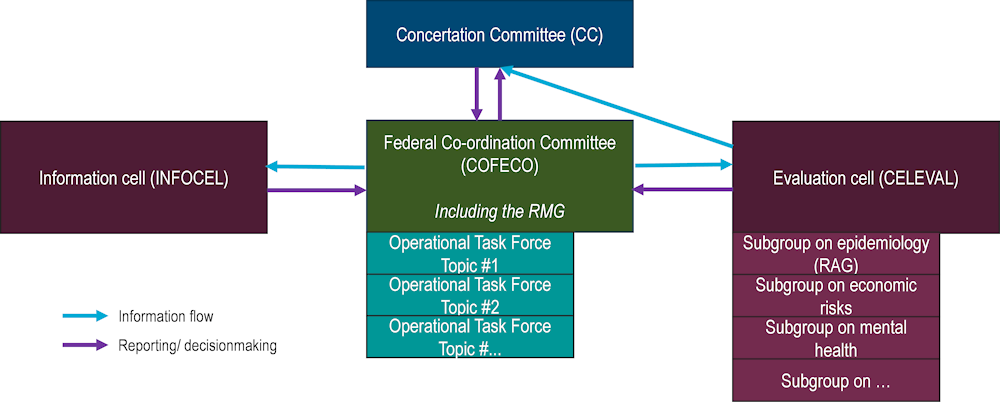

Traditional crisis management at the federal level in Belgium is structured around the COFECO, for interdisciplinary cross government co-ordination, and around the RMG, for the specific co-ordination of the sanitary crisis response (Belgian Official Journal, 2003[2]) (Belgian Official Journal, 2018[18]). However, new structures were put in place to provide scientific advice to government and help with co-ordinating the crisis response. Whilst, as mentioned previously, the creation of ad hoc bodies is not specific to the Belgian experience, the sheer number created specific challenges in this country (Figure 3.2). To this list should be added the different task forces set up to address specific challenges (vaccination, hospital & transport surge capacity, primary & outpatient care surge capacity, etc.), all reporting to different stakeholders.

Figure 3.2. Co-ordination cells and scientific advice bodies during the federal phase of the COVID-19 crisis

Note: This chart is a simplified representation of the different cells and bodies involved during the federal phase of the COVID-19 crisis.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on information gathered and shared by Belgian authorities.

First, the creation of new crisis management cells and advisory bodies led to overlapping mandates between structures. For instance, the second iteration of CELEVAL (the Evaluation Cell of the Federal Co-ordination Committee), was first tasked with developing a barometer of the level of circulation of the virus, together with general principles regarding the measures to be taken based on the progression of the virus. It was later asked to translate these principles into detailed specific implementable measures for each sector of the economy – a task which proved outside of the initial scope of their mission.

The creation of new structures also blurred the lines of responsibility between the different bodies. For instance, while CELEVAL was created to advise the Federal Co-ordination Committee (COFECO), it de facto also advised the National Security Council (NSC), a political decision-making body which took a prominent place during the acute phase of the crisis. In addition, the Group of Experts tasked with the Exit Strategy (GEES) gave its advice directly to decision makers, thus bypassing the operational crisis managements cells that were in charge of preparing policy decisions.

Overall, this confusion of lines of responsibility generated a lack of clear division of roles between policy, operational, and scientific advice – often to the detriment of operational decision making. This can be illustrated by the fact that the online Frequently Asked Questions pages prepared by the INFOCEL (the Information Cell bringing together local, regional, community and federal authorities to co-ordinate crisis communication, and co-chaired by FPS Health and the NCCN), crystallised tensions and discussions between stakeholders. Indeed, in the absence of clear implementation routes for many of the decisions taken at a political level, stakeholders in the INFOCEL were often left having to interpret new rules and decisions by themselves within short timelines. As a result, INFOCEL, a body that had in theory been created to focus solely on communication efforts, became an important player in the operationalisation of crisis management measures.

Co-ordination between levels of government was mostly enabled by personal relations

In federal countries particularly, effective crisis management requires close co-ordination between national and sub-national entities – which are often at the front line of the crisis response and are responsible for crucial aspects of pandemic management. As a result, in many OECD countries, co‑operation with sub-national entities was thus both essential and complex, given that national authorities had to contend with the varying local realities of sub-national authorities (OECD, 2022[1]; OECD, 2020[19]). Therefore, the quality of co-ordination among levels of government has been a key determinant in the effectiveness of the response to the health, social, and economic crisis across OECD countries (OECD, 2022[1]; OECD, 2020[19]).

In Belgium, co-ordination between levels of government is well institutionalised, as it is made necessary by the federal nature of Belgium and the division of competencies between levels of government ensuring the federal level and federated entities are on the same equal footing (Belgian Official Journal, 1980[20]). From a health perspective, the Interministerial Conference (IMC) on Public Health embodied co-ordination between levels of government. As a consultative and decision-making body, existing before the pandemic, the IMC gathered all eight ministers – from federal and federated entities – with public health responsibilities. The Conference met frequently and regularly throughout the crisis and discussed technical health-related matters – such as testing and monitoring strategies or procurement procedures for vaccines – ahead of the high decision-making level meetings.

Indeed, as of the beginning of the crisis, federal and federated entities convened regularly at the highest decision-making level – first through the National Security Council (NSC) and, as of 10 October 2020, through the Concertation Committee (CC). The use of the Concertation Committee, a body that had been established to resolve conflicts regarding the division of competences between the different public entities of Belgium’s federal state, formalised the fact that both federal and federated authorities were given an equal voice at the decision-making table (Belgian Official Journal, 1980[20]). All stakeholders involved have underlined the importance of the CC for enabling meaningful co-ordination across levels of government, including on topics where sub-national levels of government may not have a mandate de jure. In addition, the policy decisions made by the NSC and the CC were regularly communicated to the public through joint conferences bringing together the heads of the executives of all of the entities involved: the Prime Minister of Belgium and the Minister Presidents of the federated entities.

This effective co-ordination at the political level was also supported by collaboration at a technical level between federal and federated entities. First, the NCCN had single contact points in both Flanders and Wallonia for matters related to crisis management that predated the crisis. For instance, the Flemish Crisis Centre (CCVO) had been created in 2017 to serve as a contact point for the NCCN for external co-ordination. As a result, communication between levels of government on matters that were within the purview of the NCCN was facilitated. A reflection on the role of regional crisis cells and their interaction with the NCCN could be relevant to better articulate federal and federated crisis management on a standing basis. This could also require the development of crisis cells in other federated entities and public services, to establish clear communication lines leading to the NCCN. Doing so would enable better collaboration, as well as clearly recognise the NCCN’s expertise and tools in multidisciplinary crisis management.

Co-ordination between federal and federated entities was also enabled by the fact that the many crisis management and science advice bodies mentioned previously did not have clear mandates, which resulted in many cases the same group of people attending meetings for most of these bodies. While this situation meant that efforts were often duplicated and that lines of responsibilities were blurred (see previous sections for more on this topic), the upside was to facilitate information flows between stakeholders and levels of government. Going forward, the pandemic law explicitly provides a legal basis to this co-operation during epidemic emergency situations: “Whenever the measures have a direct impact on political areas falling within the competence of the federated entities, the federal government offers the federated governments concerned the possibility of consulting in advance about the consequences of these measures for their political areas, except in cases of emergency” (Belgian Official Journal, 2021[21]).

Nevertheless, co-ordination of the federal or federated executives with local entities (municipalities and provinces, mostly) proved more challenging. The co-ordination between the federal level and provinces was hindered due to the fact that the NCCN, which has an explicit mandate to serve as a contact point for governors on risk management issues, was not in the driving seat of the crisis response. For example, the NCCN has been on some occasions unable to provide explanations to governors about policy decisions made at the federal level. Similarly, co-ordination between the federal and/or federated entities with municipalities was somewhat challenging. Indeed, a large share of municipalities (46%, out of 259 municipalities) report having faced challenges in communicating COVID restrictions for various reasons, such as inconsistent (as well as sometimes contradictory) messages coming from the different government entities (OECD, 2023[22]). Some of these challenges also arose between federated entities and municipalities and/or provinces.

One notable exception is in Brussels, where, due to the police functions devoted to its Minister President, the co-ordination with all 19 municipalities took place through the Regional Security Council. The provincial crisis cell was regularly extended to mayors when local measures could have had an impact on them (article 23, paragraph 2, of the ministerial decree of 30 June 2020). This made co-ordination with mayors shorter and more efficient as it reduced the number of stakeholders involved and built upon the first-hand information of the Minister President.

At the federated level, cross agency co-ordination mechanisms mostly functioned well

Multidisciplinary crises of the likes of the COVID pandemic call for increased horizontal co-ordination within each level of government, including at the sub-national level. Co-ordination mechanisms, whether informal or formal, need to be tailored to the context, the mission and the objectives of the crisis response.

In Belgium, horizontal co-ordination of the crisis response within each federated entities was mainly structured around the Minister Presidents and their respective cabinets. This ensured strong leadership and coherence, both in the interactions with federal stakeholders and other federated entities, and within each federated entity. Indeed, the Wallonia region set up an internal administrative co-ordination cell before the beginning of the federal phase. Its administrative co-ordination mechanism was structured around the regional crisis centre supporting AviQ (Agence wallonne pour une Vie de Qualité). The political co-ordination was done with the cabinet of the Walloon Minister President, the Minister of Health, and AviQ.

In Flanders, from March to October 2020, both internal and external co-ordination was done by the CCVO, that had a central crisis management team and crisis communication and information team for the entire Flemish administration. On 22 October 2020, Flanders set up an extra co-ordination platform, presided by the cabinet of the Minister President, facilitated by CCVO, which brought together both ministerial cabinets and the respective administration. This platform helped co-ordinate input from Flanders to the CC.

In Brussels, administrative co-ordination was ensured by a regional task force representing the Services du Collège Réuni (SCR) and Iriscare, the Brussels administration, and led by a COVID-19 co-ordinator. Political co-ordination was ensured by the Minister President, regularly sharing information to the government and parliament. Institutional specificities giving the Minister President of Brussels-Capital police functions usually devoted to governors, also allowed Brussels-Capital’s Minister President to be present at the governors meeting, facilitating information flow.

The German-speaking Community established in February 2020 an overarching committee to co-ordinate the community crisis response. Finally, the French-speaking Community saw close co-ordination between the cabinet of the Minister President and ONE (Office de la naissance et de l’enfance). Crisis management of this scale was challenging for a language community that is not traditionally at the centre of crises. Overall, those different structures greatly helped overcoming siloed structures at each level of government, even though the pace of the crisis put administrations and their staff under pressure.

Going forward, standing federal crisis management structures and reporting lines should be clarified and vertical co-ordination further institutionalised

In the future, it will be crucial to ensure that federal crisis structures are used according to their intended purposes. This involves allowing the COFECO to function as the central body for policy preparation and implementation, with the support of a network of specialised operational task forces. The specific composition and area of specialisation of the task forces will depend on the type of crisis that the COFECO and NCCN need to manage. Giving the COFECO the opportunity to play its full role as a management body that sits between the policy level of decision making (in the case of a national and multidisciplinary crisis where competencies from different levels are involved, the CC) and the technical level of decision making (task forces) or the science advice (CELEVAL), could resolve some of the issues with the implementation of policies that stakeholders faced during the COVID-19 crisis. To this end, the composition of COFECO could be adapted to ensure that federated entities are represented, in addition to the provinces (at governor level).

In addition, it would be useful to establish clear reporting lines between the standing federal health management structures and the multidisciplinary management structures in the advent of future health related federal level crises (Annex Figure 3.A.1). Concretely, during the federal phase of a health-related crisis, the RMG would report to the COFECO – with one body focusing on the preparation of health-related decisions and the other focusing on the impact of these decisions on other policy fields. Similarly, the RAG could be one of the expert groups feeding into CELEVAL (see the next section for more information on this point). Implementing this approach would involve, among other things, enhancing information sharing and establishing collaboration agreements between these bodies.

Finally, while the Interministerial Conferences did play an important role in the field of health during the pandemic, evidence shows that in other areas (see Chapter 5, for example), there may have been insufficient co-ordination across federated and federal entities. In policy areas where different levels of government have shared competencies, the use of Interministerial Conferences can ensure greater alignment and co-ordination throughout entities and levels of government. This tool is even more so important in Belgium where, more so than in other federal countries, federal and federated entities are on an equal footing. During epidemic emergency situations, the pandemic law will provide a legal basis to anchor vertical co-operation between entities, as mentioned previously (Belgian Official Journal, 2021[21]). In addition, in times of multidisciplinary crises involving different levels of government, the Concertation Committee should be considered as the best forum for making decisions at the political level.

3.2.3. The role of evidence and scientific advice in crisis decision making

The last important aspect related to crisis management governance concerns the advisory role that experts and scientific bodies play to help governments make decisions. This role is also known in risk management as “sense-making”. The COVID-19 crisis required governments to make clear and legitimate decisions based on reliable data in a context where there were many unknowns and very little time for dialogue and information gathering (OECD, 2020[16]). Governments were also faced with the need to synthesise information from multiple sources and stakeholders and use it to inform plans and responses to the COVID-19 crisis (OECD, 2020[16]). As a result, many OECD countries, such as Luxembourg, Spain and Switzerland, have activated or created scientific and expert bodies to provide advice to decision makers. While necessary in the face of so many unknowns, uncertainties around the exact mandates or compositions of these bodies risked threatening the public’s trust in government and in expert advice, as well as calling into question the boundary between expertise and political decision making.

The federal government of Belgium also faced many of these same challenges. Firstly, the different scientific advisory bodies that existed throughout the crisis did not always have a clear mandate. In addition, while efforts were made to ensure that the advice decision makers were receiving was multidisciplinary, there were challenges with the legitimacy of this advice due to a lack of clarity around internal decision-making processes. In this context, this section provides an analysis of the extent to which the Belgian federal scientific advisory system meets the main principles for robust and credible scientific advisory systems set out by the OECD (see Box 3.3).

Box 3.3. General principles for a robust and credible system to provide science advice to the government

To ensure the availability of credible expertise, governments should create scientific advisory systems that:

1. Have a clear mandate, with defined roles and responsibilities for its various actors. This includes:

clear definition and demarcation of advisory and decision-making roles and functions

definition of the roles and responsibilities of each actor in the system

ex ante definition of the legal role and potential liability of all persons and institutions involved

availability of the institutional, logistics and personnel support necessary to accomplish the advisory mission.

2. Involve relevant stakeholders, including scientists and policymakers, as appropriate. This involves:

using a transparent participation process and following strict procedures for declaring, verifying and dealing with conflicts of interest

drawing on the scientific expertise needed in all disciplines to address the issue at hand

explicitly considering whether and how to engage non-scientific experts and civil society stakeholders in advice development

implementing effective procedures for timely information exchange and co-ordination with various national and international counterparts.

3. Produce sound, unbiased and legitimate advice. This advice should:

be based on the best scientific data available

explicitly assess and communicate scientific uncertainties

be free from political interference (and other special interest groups)

be generated and used in a transparent and responsible manner.

Source: OECD (2022[23]), Scientific advice in crisis: Lessons learned from COVID-19 (unpublished); OECD (2015[4]), The Changing Face of Strategic Crisis Management, OECD Reviews of Risk Management Policies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264249127-en.

The respective responsibilities of ad hoc scientific advisory bodies were not always clear or explicit and should be clarified

First, to fulfil their mission, scientific bodies should have a clear mandate, giving them the legitimacy to interact with governmental and non-governmental stakeholders. In this sense, the OECD General principles for a robust and credible system to provide science advice to the government recommend having a clear mandate with defined roles and responsibilities for its various actors (OECD, 2015[4]) (see Box 3.3).

From the beginning of the crisis, the federal government in Belgium developed several ad hoc advisory bodies to council decision makers on health, economic and societal matters. Federal scientific institutions, such as Sciensano, the Superior Health Council, the Federal Agency for Medicines and Health Products, or the Health Care Knowledge Centre (KCE), collectively played an important role in feeding epidemiologic evidence to those bodies. Few of these ad hoc bodies, however, had an explicit or clear mandate. This resulted in overlapping responsibilities between groups and questions around the exact scope of the advice to be provided. For instance, the GEES co-existed with CELEVAL, when scientific advice on the exit strategy could theoretically have been covered by the latter. Another example relates to CELEVAL 2, a body originally tasked with providing the federal government with advice on how society could ‘learn how to live with the virus’ and with developing a barometer to assess the state of the epidemic and generic measures associated to it. This body was later on tasked with translating those generic measures into sectorial and specific ones, a mission that the experts in the group deemed outside of the role of an advisory committee and best fit for an operational cell. On the other hand, the GEMS, which was established later in the crisis, did have an explicit mandate.

In addition, even where mandates were clear, scientific advice bodies had limited resources to support the accomplishment of their advisory mission. Experts working in these groups did so on several instances on a voluntary basis and were not relieved of their other functions, creating challenges with continuity in experts’ attendance. There were also challenges in ensuring sufficient resources to provide a secretariat for these bodies. While some bodies turned to private sector consultancies to fill those gaps, thus creating other issues linked to the transparency and the exact role of these individuals in the advisory body, not all bodies were able to do so.

It will be essential in the future for advisory bodies, whether they are standing, dormant crisis cells or ad hoc bodies, to benefit from clear and explicit mandates. This mandate should not only be limited to a legal text promulgating the creation of body but should also include clear terms of reference and a budget.

Efforts were made to ensure the multi-disciplinarity of the advice, but broader scientific expertise could have been included

The COVID-19 pandemic quickly emerged as being not only a sanitary crisis, but also a social and economic one. The multidisciplinary nature of the crisis meant that governments had to rely on different types of expertise. However, in many OECD countries, science advice bodies were too heavily focused on the health impacts of the crisis (and mainly physical health, and to a much lesser extent mental and social health), especially in the first wave of the pandemic (OECD, 2022[1]). Indeed, including expertise from a variety of backgrounds ensures that decisions are informed by credible and neutral advice. In Belgium, the idea of multidisciplinary advice came in quite early in the crisis, with the GEES, CELEVAL 2 and the GEMS seeking to include experts from different fields of expertise, such as economics, civil society and psychology.

In practice, striking a balance between different disciplines was a complex task. The GEES, for instance, was composed of 5 experts on biomedical science, 5 experts focusing on social and human sciences, and 2 experts in economics, and had also different task forces (for instance one on mental health, one on how to deal with other medical conditions than COVID19). However, in practice, stakeholders felt that voices from non-virological and epidemiological disciplines were not given the same weight in the discussions. This challenge is, in part, a result of the fact that decision-making processes within the groups had not been formalised ex ante. For instance CELEVAL2 involved a wider range of expertise, but was still dominated in the facts by experts in infectiology. The GEMS, however, did manage to involve a wider range of expertise (it was composed of 24 experts in infectiology, epidemiology, psychology, public health, economy, civil society, as well as public services and sanitary authorities) and stakeholders report that more balanced discussions took place. The Economic Risk Management Group (ERMG) is also a good example of an advisory body that represented different forms of expertise, as it was a group dedicated to analysing the economic impacts of the crisis, where social partner organisations were represented (see Chapter 6).

Still, this multidisciplinary approach could have benefited from including an even wider range of expertise. Civil society and practitioners are also important stakeholders, as they can provide valuable information on the operational impacts of measures and their feasibility. They can increase the credibility of scientific advice (OECD, 2022[1]). These groups were not always fully involved in the Belgian advisory bodies. In fact, across the OECD, only few countries involved those types of stakeholders in their scientific advice bodies. Similarly, experts from other disciplines, such as behavioural insights or mental health specialists, were rarely included in the above-mentioned advisory bodies. This type of expertise did play an important role in helping shape an effective yet proportionate response to the crisis in other countries. For instance, in Austria, the COVID Crisis Co-ordination Committee (GECKO), provided multi-disciplinary evidence throughout the crisis. The GECKO brought together scientists from various disciplines, experts from interest groups, and other organisations (OECD, forthcoming[24]). In Belgium, building multidisciplinary advice in times of crisis will prove essential to best address potential upcoming crises. Practitioners, leaders of civil society organisations and legal and mental health experts could enrich the type of expertise developed in scientific advice bodies and improve the nature of the advice delivered.

The credibility and legitimacy of scientific advice was challenged, and should be the focus of future efforts to strengthen science advice

The COVID-19 crisis put scientific advice under the spotlight. Across OECD countries, efforts have been made to support this advice through an enabling and supportive institutional environment. Sound evidence governance ensures that the evidence provided answers to the highest standards of advice, limiting undue bias in decision making, reducing potential impact of lobbying, and ensuring governments can act in the interest of the public. This means ensuring the appropriate levels of integrity, accountability, contestability, public representativeness and transparency possible (OECD, 2020[25]). The sense of urgency deriving from the crisis sometimes shook scientific advice governance.

In Belgium, efforts have been made to make the advice shared with decision makers transparent, as all reports from the GEES, CELEVAL2, the GEMS and the RAG were made public. This aligns with the OECD Recommendation, which highlights the need to “ensure transparency regarding the information used to ensure risk management decisions are better accepted by stakeholders to facilitate policy implementation and limit reputational damage” (OECD, 2014[3]). Those reports were usually published after corresponding decisions were made. Even though they were not available in all official languages, they represented an important step towards greater understanding of the advice made and its scientific underpinnings. Similarly, the Austrian GECKO, mentioned previously, saw its expert meetings summarised in an executive report and published on the website of the federal Chancellery (OECD, forthcoming[24]). In Ireland, the National Public Health Emergency Team was in charge of co-ordinating the response of the health sector and facilitating information flow between the Department of Health and its agencies. The Team published its meeting agendas and meeting minutes, including dissenting opinions, actions and policies discussed (OECD, 2020[16]). Going forward, making Belgian scientific advice public by default and including dissenting expert opinion when applicable could help make scientific advice more credible and robust.

Moreover, the decision-making processes of the various ad hoc scientific advice bodies could have benefited from being made explicit and public, as was done for the RAG accordingly to its house rules. The OECD Principles for a robust and credible system to provide science advice to the government highlight the need to produce sound, unbiased and legitimate advice that should be based on the best scientific data available, explicitly assess and communicate scientific uncertainties, be free from political interference (and other special interest groups), and be generated and used in a transparent and responsible manner (OECD, 2015[4]). This, amongst others, requires declaring potential conflicts of interest, which is particularly crucial for trust in a context where scientists are speaking to the public, to protect these scientists from external pressures. Such declarations of conflict of interest did take place in the RAG and the GEMS. However, these were not always shared with the public. Yet, sharing with the public how advice is formulated and how disagreements are taken into account amongst expert groups can help citizens understand why the advice was made. It also allows for disagreements to be structured and balanced, instead of taking place through the media. The pandemic law adopted in 2021 does mention that experts involved in providing advice during a future pandemic will need to respect a code of ethics determined by the King, as well as the fill out an of a “declaration of interest” (Belgian Official Journal, 2021[21]). However, going forward, experts for which potential conflicts of interest have been identified should clearly be excluded from participating in government advisory bodies at large, regardless of whether these bodies serve to advise government on pandemic response or not. Doing so would better protect experts participating in those groups from external pressures, as well as strengthen the legitimacy of the advice. To this end, establishing procedures for identifying, managing and resolving conflict of interest situations in all government advisory bodies could be a first step for the Belgian government.

3.3. Crisis communication

The OECD Recommendation advises governments to communicate risks to the public using targeted messaging, methods tailored to different audiences, while ensuring that the information provided is accurate and reliable (OECD, 2014[3]). In this sense, the Recommendation stresses the importance of crisis communication, understood as communication from the government to the public and stakeholders on the evolution of the crisis and the actions to be taken in response to a risk that has materialised. Such communication should be targeted, adapted, accessible, precise and coherent (OECD, 2016[26]).

In Belgium, as in many other OECD Member countries, it has sometimes been difficult to strike this balance, given the fast-changing nature of the health measures to be communicated. Indeed, while crisis communication was mostly coherent throughout the pandemic, the initial role some scientific experts played with limited involvement from senior decision makers impacted its overall coherence. In addition, several experts from the ad hoc scientific advice bodies communicated to the media on a regular basis, which sometimes blurred the lines between official communication channels and those done by individuals in their own name. Moreover, Belgium diversified its communication strategies and channels, but ultimately could have gone further in making efforts to reach marginalised groups and different language communities. Finally, the impact of the federal government’s communication efforts, particularly on trust, have been evaluated throughout the crisis. These efforts have proved helpful in providing insights to the government on how and when to adapt communication measures.

3.3.1. Crisis messaging was mostly coherent but suffered from dilution across levels of government

As was the case in most OECD countries, producing coherent messages to the public, resting on government-wide communication strategies, was a challenge in Belgium. This problem had already been identified by OECD Member countries prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Indeed, OECD data shows that in 2019, Centres of Government and Ministries of Health had already identified communicating in times of crises and producing government-wide communication strategies as some of the top challenges governments face when it comes to public communication (OECD, 2021[27]). This is because meaning-making in times of crisis requires coherent, clear, and continuous communication, which is often difficult to achieve when decisions have to be made quickly and adapted continuously. This is why leadership is also critical to crisis communications in order to provide an overall narrative for the crisis response and to gain trust from citizens (OECD, 2015[4]) (see also previous sections of this chapter for more information on this topic).

Meaning-making quickly evolved throughout the crisis in Belgium. As was the case in some other European countries, public communication in Belgium, during the early months of 2020, conveyed a conservative view of the risk present by the COVID-19 virus, informed by the national experts’ understanding of the evidence available at the time (see Chapter 2 for more details on this). It is only once it became clear that the nature of the threat would amount to a pandemic that public communication was scaled up and the nature of the risk communicated fully. This shift in narrative is not specific to Belgium but may have exacerbated issues with trust in government (see Figure 3.4) and potentially minimised the impact of communication efforts (Figure 3.3).

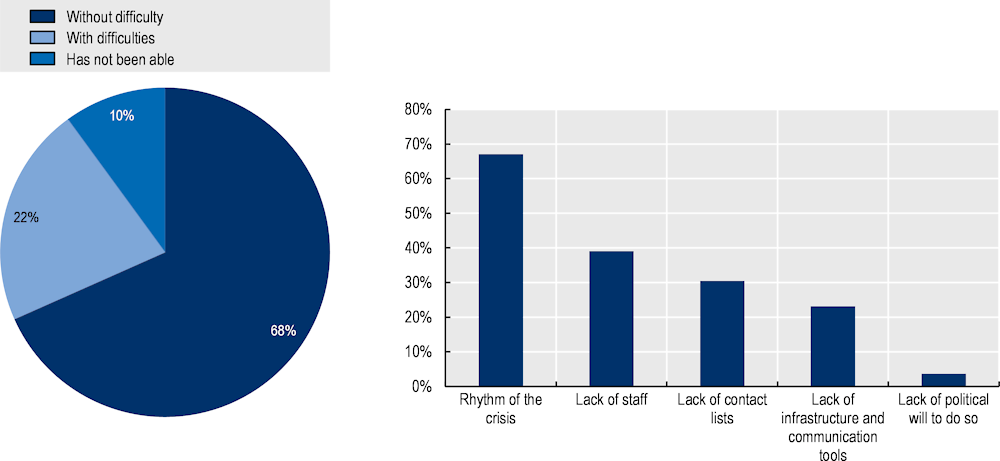

The work of INFOCEL, whose initial role was to bring together the spokespersons from the different government entities to align the overall crisis messaging, contributed to ensuring the coherence of messages from 12 March 2020. Still, the coherence of messages to the public in further stages of the crisis suffered from the multiplicity of messaging coming from the different federated entities. Indeed, data from the OECD shows that a large share of respondent municipalities encountered challenges throughout the pandemic with the inconsistency of responses between levels of government (37% of total respondent municipalities, 81% of municipalities having faced communication challenges) and contradictory information shared from the different government actors (34% of total respondents, 73% of municipalities having faced communication challenges) (Figure 3.3) (OECD, 2023[22]).

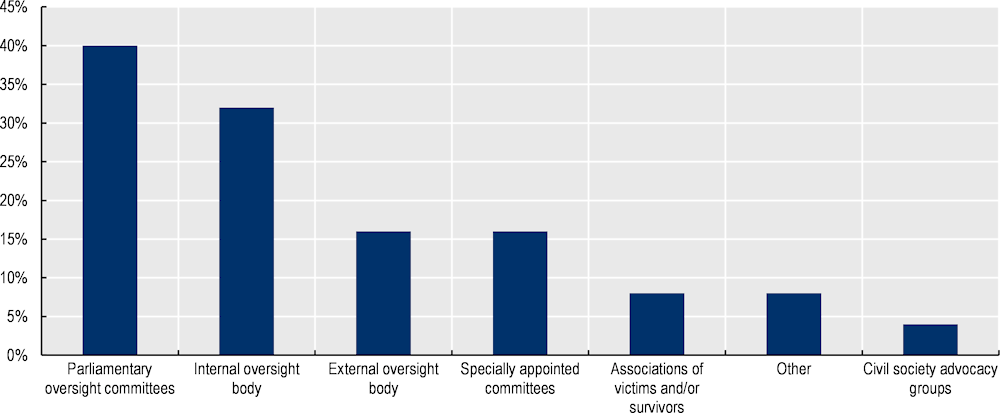

Figure 3.3. Main challenges faced by municipalities in communicating COVID-19 measures to the general public

Main challenges highlighted by respondents that encountered communication challenges

Note: Original survey question: Have you encountered any challenges in communicating COVID-19 measures to the general public? Yes/ No, If so, why?: N=118. VLA =55, WAL=53, BXL=6, German-Speaking Community=4.

Source: OECD (2023), Survey of Belgian municipalities in the context of the OECD Evaluation of Belgium’s COVID-19 responses.

Another challenge in communication about the crisis in Belgium was linked to the use of experts as spokespersons during the crisis. Indeed, aside from the two interfederal spokespersons, scientific experts from advisory bodies were in charge of communicating the epidemiological situation and any restrictions to the public during the first six months of 2020. Whilst experts are valuable figures in a pandemic to help with meaning-making and to foster trust amongst the public that governments’ decisions are backed by science, the choice to have them be the ones to communicate almost exclusively to the public created several challenges. First, few of these experts had prior experience in communicating to the public or had received any media training. Several of them also felt that their mandates were unclear and were uncertain as to what media engagements they could or could not accept.

More importantly, scientific experts were asked by media to provide explanations for decisions that they had not taken part in. This became particularly true after the first wave of the pandemic when decisions became more nuanced (for example finding compromises between societal, economic and health interests). Whilst the Prime Minister and Minister Presidents were holding regular press conferences to present the decisions made by the Concertation Committee, there was usually little time to discuss the application of measures or their rationale. The strong presence of experts in the media therefore raised important issues with the public’s perception of the boundaries between science and decision making in democracy. In later stages of the crisis, these tensions were somewhat alleviated as the political sphere – as was the case with the Minister of Health in particular – began communicating more regularly and directly to the public.

3.3.2. Despite a multiplicity of communication channels and tools, there were challenges targeting vulnerable and minority groups

Crisis communication took different shapes and forms during the crisis across OECD countries. Media briefings, press releases and conferences, information campaigns, posts on social media and Frequently Asked Questions were tools used to communicate the epidemiological context and measures to the population. During the COVID-19 crisis, communication channels opened by the NCCN and Centres of Government and Ministries of Health were crucial to communicate to the public (OECD, 2021[27]).

The Belgian government also used a wide array of communication channels, such as a one-stop-shop website for all information related to the pandemic response, info-coronavirus.be, the nomination of two spokespersons, one each for the French and Dutch-speaking Communities. Later on, periodic press conferences of the NCCN were also partially translated into German. The Chancellery also organised four communication campaigns in over 10 languages, both on print, on the radio, and on TV. Those campaigns were thoroughly monitored and evaluated to follow their impact and their resonance with the population. Throughout communication campaigns, TV, posters, social media and radio remained the channels reaching the biggest share of the public. This multiplicity of channels through which the same message was shared was useful to target as large a share of the population as possible. Federated entities also organised parallel communication campaigns, in some cases to strengthen the federal message, as in Flanders, or to target more precisely communities, as Brussels-Capital did around religious feast days.

Tailoring communication materials has been shown to be an efficient way to disseminate information to diverse population segments (OECD, 2022[1]). Despite the fact that the Chancellery and NCCN translated their communication campaigns in many different languages and that the Chancellery contacted influencers from various backgrounds to reach certain communities, certain language minorities and people with immigrant backgrounds may have not been sufficiently targeted. Yet, such targeting could have increased compliance with measures. Indeed, studies from INFOCEL showed that some communities were getting their information from non-governmental and non-Belgian sources. In Brussels, data shows that most marginalised groups did not trust public authorities, which led to communication challenges (Fortunier and Rea, 2021[28]). Attempts at developing targeted communication channels through associations of young people with migrant background took place as part of the vaccination strategy, but were ultimately not evaluated. Those efforts were, however, going in the right direction, and the development of a network of relevant associations to quickly and efficiently reach all parts of the population should be developed. Moreover, communications between general practitioners and patients were unsystematic, with some reporting extensive outreach to vulnerable patients about COVID-19 prevention, risks and care, while others were less proactive. General practitioners and their networks could be used in future health crises to better communicate about both the health emergency itself and the importance of care continuity, particularly for vulnerable populations (see Chapter 4). In addition, not all of the information shared to the public was translated in German, one of the three national languages of Belgium. As a result, the population of the German speaking part of the country would rely on foreign (German) news for information, sometimes creating confusions around what rules to follow. To that extent, ensuring timely translation of key information to all three national languages should be a goal of the national communication strategy.

3.3.3. Important efforts were made to monitor trust levels and the impact of communication efforts

Adherence to measures is closely linked to trust in government and the perception that measures are necessary. Across OECD Member countries, trust in national government is associated with perceptions of preparedness for a future pandemic, and vice-versa, making trust in government a crucial component of potential adherence to future measures (OECD, 2022[29]). This is why it is important for governments to monitor levels of trust and any impacts communication efforts might have on them.

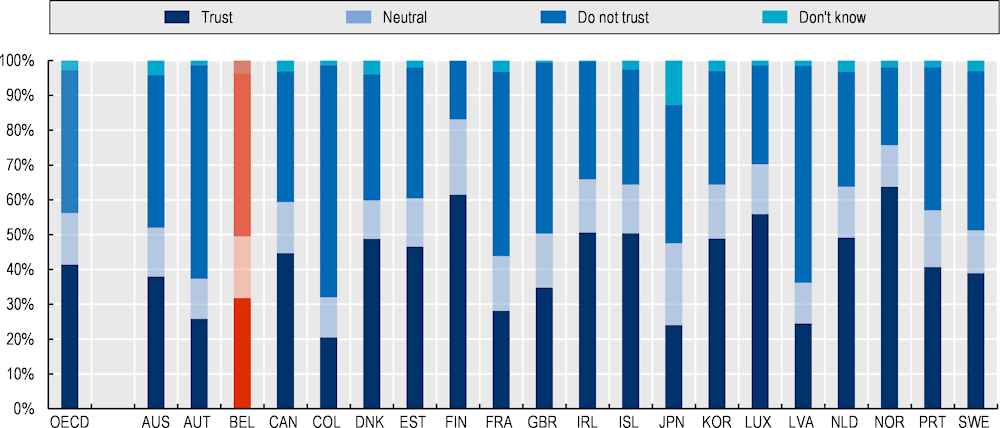

Data shows that Belgium historically has a relatively lower share of its population that trusts the national government than most OECD countries (Figure 3.4) (OECD, 2022[29]). In addition, evidence from the work of the Motivation Barometer, a consortium of Belgian academics focused on measuring trust during the pandemic and financed by the National Institute for Health and Disability Insurance (RIZIV-INAMI), shows that citizens’ trust in government and public institutions generally declined throughout the pandemic in Belgium, even though trust in some political figures may have increased during that time. For instance, vaccinated inhabitants’ trust in government went from 49% to 33% between November 2021 and January 2022. For unvaccinated residents, those numbers decreased drastically, from 37% to 3% (Movation Barometer, 2022[30]).

Figure 3.4. Belgium sees lower trust in its national government than other OECD countries

Share of respondents who indicate different levels of trust in their national government (on a 0-10 scale), 2021

Note: Figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the question “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust the national government?” Mexico and New Zealand are excluded from the figure as the question on trust in national government is not asked. “OECD” presents the unweighted average across countries. For more detailed information, please find the survey method document at http://oe.cd/trust.

Source: OECD (2022[29]), Building Trust to Reinforce Democracy: Main Findings from the 2021 OECD Survey on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions, Building Trust in Public Institutions, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b407f99c-en.

Levels of trust also differed between stakeholders. 78% of vaccinated groups, and 25% of unvaccinated groups respectively, on the contrary, trusted the competence of the GEMS (Movation Barometer, 2022[30]). Even though further work should be carried on this specific aspect, lower vaccination rates in Wallonia than in other parts of the country also correlate with a more active antivax discourse in the French-speaking and German-speaking Communities. This is further confirmed by evidence that 20% of people in Wallonia and Brussels-Capital believe in COVID-19 conspiracy theories, versus 18% on average in Belgium (Gugushvili et al., 2023[31]). Overall, results show that these challenges with trust in government in Belgium may have minimised the impact of communication efforts (Figure 3.3). Acknowledging this challenge, the NCCN monitored media and social media to also identify mis and dis information efforts. Although fighting against mis and dis information represents a complex task, the NCCN developed guidelines to support municipalities with dealing with misinformation. Data from the OECD shows that municipalities did not perceive false and misleading information from non-governmental actors as a major communication challenge (see Figure 3.3), suggesting that the NCCN’s efforts to support local actors in this regard may have been fruitful.

Reinforcing the effectiveness of crisis communication in the future will require increasing its coherence across levels of government and setting clearer boundaries between science and decision making

In the future, ensuring that measures are clearly communicated, in a uniform manner, by all levels of government and through a single, dedicated, channel could assist municipalities in understanding and applying them as envisioned. In this sense, the role of the NCCN’s INFOCEL is crucial to ensure alignment between federal and federated entities. Allowing the INFOCEL to play its full role as an operational body dedicated to aligning communication efforts will be crucial to the effectiveness of future crisis communication campaigns.

Moreover, support to provinces and municipalities will also be important to promote coherence across all governmental actors. This support can be provided through communication toolkits or guidelines that should be developed jointly with different levels of government to help municipalities and provinces adapt to fast-evolving situations.